The Most Frequently Asked Questions About Liberal Arts Education

Created by Liberal Arts Contributing Writer

A liberal arts education is all about asking questions. In fact, many of the critical-thinking skills and problem-solving methods that these degrees teach involve learning precisely how to ask the right questions in the first place.

A liberal arts education gives you the skills you need to answer the big questions in life… and the small ones.

So, if you’re here looking for some answers to the most frequently asked questions about getting a liberal arts education, you are already on the right track.

We’ve put together some comprehensive answers to some of the most common questions students bring up when considering a liberal arts and sciences education. If you’ve come to a place in life where you are serious about earning a degree in liberal studies, chances are good you have a lot of these same questions.

You’ve come to the right place to start your journey in search of answers.

Questions are critical to the entire liberal studies approach to learning. You’ve come to the right place to start your journey in search of answers:

Can You Be a Teacher with a Liberal Arts Degree?

How Can I Make Money With a Liberal Arts Degree?

Is a Liberal Arts Degree Worth It?

Is History a Liberal Arts Degree?

Is Political Science Liberal Arts?

Is Psychology Liberal Arts?

What Are Liberal Arts Classes?

What Are the 7 Liberal Arts?

What Can You Do With a Liberal Arts Degree?

What is Liberal Arts and Humanities ?

What is Liberal Arts and Sciences ?

What Is a Liberal Arts College?

What Is a Liberal Arts Major?

What is Liberal Arts Math?

What is the Goal of a Classical Liberal Arts Education?

Why Is Liberal Arts Important?

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Education Resources

- Associate in Liberal Arts

- Bachelor of Liberal Arts

- Master of Liberal Arts

- Doctor of Liberal Studies

- Certificate in Liberal Studies

Recent Articles

Interdisciplinary, Innovative, Inclusive: Johns Hopkins University’s Master of Liberal Arts Turns 60

Why a Liberal Arts Degree Can Be More Valuable Than a Specialized Degree in Today’s Job Market

What Is a Liberal Arts Degree, and How Can It Prepare You for Success In Any Industry?

Your Biggest Liberal Arts Questions, Answered

You’ve probably had at least one relative ask you what having a liberal arts degree even means—or maybe you’ve even asked them . And that’s fair! The term “liberal arts” leaves a lot to be desired, especially since you don’t actually need to vote blue or be an artist to pursue a degree in it.

Liberal arts has been a cultural flashpoint of criticism in recent years; it’s easy to believe that an art history degree, for example, is nothing but a passion pursuit. But the liberal arts are fundamentally misunderstood, both in terms of the areas of study and the crucial societal importance that this degree confers.

So, what exactly does a liberal arts education encompass? Let’s break it down.

Q: What exactly does liberal arts mean? A: A liberal arts degree is grounded in the ideas of humanities and the arts and encompasses literature, philosophy, social and physical sciences and math. The “arts” in “liberal arts” aren’t limited to fine or performing arts, but denote a method of broad-based learning in many disciplines. The word “liberal” also gets lost in translation here—it doesn’t mean you’re ready to register as a Democrat. Rather, it’s rooted in the Latin word liberalis , or “free”. Mini lesson: Back in the Middle Ages , free citizens studied things like logic, rhetoric, geometry and arithmetic that would help them function successfully in society.

Q: What kind of majors would fall under a liberal arts degree? A: So. Many. Majors. Siena’s School of Liberal Arts is the largest of our three schools and encompasses more than 40 major, minor and certificate programs, including:

- American Studies

- Creative Arts

- Modern Languages and Classics

- Political Science

- Religious Studies

- Social Work

Q: What are you going to do with that degree? A: Did we just channel your parents? Here’s the deal (and here’s what you can tell them): A liberal arts degree effectively prepares you for thousands of potential careers. Most importantly, your future employers will know that you’re able to apply critical and creative thinking to your scope of work. A liberal arts education will help you to be adaptable in a rapidly evolving workforce, it will help you to synthesize a ton of different perspectives, and it will help you to communicate effectively with others. Trust us when we say this particular skill set is what sets candidates apart in the job market. (Further reading, if you’re interested: Yes, Employers Do Value Liberal Arts Degrees .)

Q: How else does a liberal arts degree set me up for future success? A: A major appeal of a liberal arts degree is that it allows students to both dive deep on subjects they’re drawn to while also broadening the scope of their experiences. At Siena especially, our liberal arts students are encouraged to challenge themselves by pursuing other possibilities outside of their main areas of interest—an inclination that will serve them well in the working world, where employees are often asked to take on responsibilities outside of their understanding or specialty.

Q. What if I don’t want to major in a liberal arts program, but still want to graduate with those skills? A. This is our favorite question, because the truth is: Business majors need a liberal arts education too . And science majors. And any major! No matter what you study, your college should have opportunities to help you hone all those liberal arts skills in other ways. So how does Siena tackle that? Through our core curriculum and first-year seminar offerings—which are not only informative and enlightening, and so relatable too. Check out our latest roster.

Got more q’s about the liberal arts? We got answers.

Related News

CREATIVE WAYS TO ANNOUNCE YOUR COLLEGE DECISION

What Professors Wish Students Knew Before Starting College

7 INSTAGRAM ACCOUNTS TO FOLLOW THAT ARE SO UPSTATE NEW YORK

What a Liberal Arts College Is and What Students Should Know

Liberal arts colleges traditionally emphasize broad academics and personal growth over specific professional training.

Liberal Arts Colleges Explained

iStockphoto

Students have freedom to explore at a liberal arts college, where there's an emphasis on broad academic inquiry.

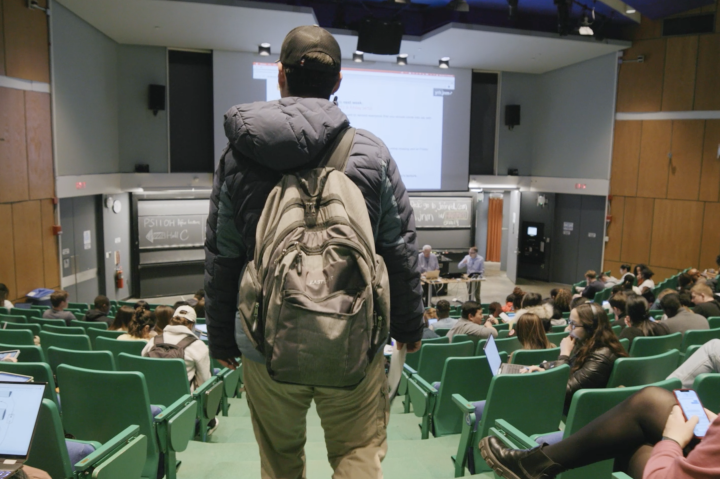

Through smaller class sizes, wide-ranging curricula and tight-knit communities, liberal arts colleges are designed to develop intellectually curious students into free thinkers who are versatile in the professional workforce, experts say.

"The goal is to become broadly educated, well-rounded members of society that can understand lots of different domains of knowledge, learn how to learn and have a specialization of sorts," says Mark Montgomery, founder and CEO of Great College Advice, a college admissions consultancy with offices across the U.S.

Some common notions about liberal arts colleges are misconceptions, experts say. For example, the phrase "liberal arts" does not reflect a political alliance.

"Kids get mixed up," Montgomery says. "'Liberal' means freedom – freedom of the mind."

Marcheta Evans, president of Bloomfield College , a predominantly Black liberal arts institution in New Jersey, warns prospective students against making generalizations about student bodies at liberal arts colleges. Since the tuition for these schools is often higher than other universities, some assume only affluent students attend, which isn't true.

"Some liberal arts institutions have very privileged kids," she says. "But you also have institutions like mine, where a lot of kids are first-generation college students."

What Is a Liberal Arts College?

Liberal arts colleges are four-year undergraduate institutions that emphasize degrees in the liberal arts fields of study, including humanities, sciences and social sciences.

Maud S. Mandel, president of Williams College in Massachusetts, describes a liberal arts education as "an introduction to general knowledge." The Association of American Colleges and Universities notes its emphasis on integrating "academic and experiential learning" and developing skills "that are essential to work, citizenship, and life."

Most liberal arts colleges do not offer separate professional education programs, such as business and engineering schools, which are designed to give students specialized training for specific professional practice.

Students at liberal arts schools are typically required to take a number of general education courses, regardless of their major. At Pomona College in California, for example, students must fulfill a Social Institutions and Human Behavior requirement, and can do so by taking courses in areas such as anthropology, public policy analysis or sociology.

What Is the Difference Between Liberal Arts Colleges and Universities?

Though every liberal arts college is unique, most tend to differ from large universities in three ways:

- Educational approach.

Liberal arts colleges tend to be smaller than large universities.

Every top 50 National Liberal Arts College in U.S. News rankings had an undergraduate enrollment of fewer than 5,000 students in fall 2020. The same was true at only eight of the top 50 National Universities ranked the same year by U.S. News.

Most liberal arts colleges do not offer graduate school programs, unlike other universities. They also tend to have small campuses and class sizes; in fact, many classes have fewer than 20 students.

Evans says some students find comfort in the sense of community that these more intimate settings can create. "Some students thrive in larger settings," she says. "Others need that smaller, family-like environment."

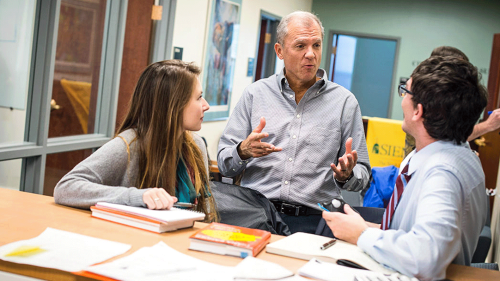

Compared to typical universities, students at liberal arts colleges can interact with their professors more easily and regularly because of lower student-teacher ratios, experts say.

"You have a relationship with your professors," Montgomery says. "It's a luxurious kind of education."

Peggy Baker, an independent educational consultant based in Asheville, North Carolina, says there's "real mentoring involved" in liberal arts college classrooms.

"I have students all the time who go to a liberal arts school and establish a relationship with a professor, and it makes all the difference," Baker says.

Students at liberal arts colleges typically have easier access to extracurricular activities than their counterparts at large universities, Montgomery says.

"The opportunities for leadership and participation, broadly, are greater," he says. "If you are trying to be the president of a club , you have much better odds of being it at a smaller college."

And most liberal arts colleges focus exclusively on undergraduate students. "You have that accessibility to research, or that lab assistant job, which would otherwise go to a graduate student," Baker explains.

Educational Approach

Most large universities offer Bachelor of Arts degrees, which use a liberal arts curriculum. This kind of degree emphasizes a broad education and so-called soft skills like communication and writing proficiency, analytical thinking and leadership ability.

At liberal arts colleges, Montgomery explains, all students follow this liberal arts curriculum design, regardless of major.

And he notes that students who have specific professional interests shouldn't exclude liberal arts colleges from their school search – these schools can also prepare students for careers in fields like engineering and business.

"You can still do engineering," he says. "There are places where you can do engineering and liberal arts together."

Many liberal arts colleges have Phi Beta Kappa Society chapters. Often referred to as PBK, this prestigious national academic honor society recognizes students who excelled academically in the arts and sciences at their college or university.

Many liberal arts colleges are private institutions, meaning they are not directly government-funded. As a result, liberal arts colleges are typically more reliant than public schools on tuition.

Prospective college students and their families sometimes turn away from liberal arts schools because of intimidating sticker prices – the total yearly cost of an education before any financial aid is applied. However, these numbers can be deceptive, experts point out.

Montgomery finds that liberal arts colleges are often generous in providing merit scholarships to students who demonstrate interest in their school.

"They want the students who want them," he says. "At some liberal arts colleges, 100% of the student body gets merit-based aid. In other words, no one pays the sticker price."

Evans encourages all students to consider the impact that financial aid could have on their education costs before ruling out small colleges. The Free Application for Federal Student Aid, commonly known as the FAFSA , helps determine a student's qualification for federal need-based aid such as the Pell Grant , loans and work-study . Most colleges require students to submit the form annually to be considered for institutional aid.

"Completing the FAFSA is one of the first steps you need to take before you even think about different institutions," Evans says.

When students factor merit and other aid considerations into their college pricing calculations, they may be pleasantly surprised by the final cost of attending a liberal arts college.

"There are dozens – if not hundreds – of high-quality liberal arts colleges in America that, in the end, will not be much more expensive, or maybe even the same price, as going to the flagship university in your home state," Montgomery says.

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

See the 2022 Best Liberal Arts Colleges

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , education

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

Photos: pro-palestinian student protests.

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton and Avi Gupta April 26, 2024

How to Win a Fulbright Scholarship

Cole Claybourn and Ilana Kowarski April 26, 2024

Honors Colleges and Programs

Sarah Wood April 26, 2024

Find a Job in the Age of AI

Angie Kamath April 25, 2024

Protests Boil Over on College Campuses

Lauren Camera April 22, 2024

Supporting Low-Income College Applicants

Shavar Jeffries April 16, 2024

Supporting Black Women in Higher Ed

Zainab Okolo April 15, 2024

Law Schools With the Highest LSATs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 11, 2024

Today NAIA, Tomorrow Title IX?

Lauren Camera April 9, 2024

Grad School Housing Options

Anayat Durrani April 9, 2024

The Value of a Liberal Arts Education is More Than Most Know

Columns appearing on the service and this webpage represent the views of the authors, not of The University of Texas at Austin.

“What are you going to do with that?” Many new graduates will hear this question in the coming weeks.

For a business or computer science graduate, the answers seem obvious. What about someone studying a liberal arts field, like English or history or philosophy? A common misconception sees these as useless subjects or a waste of valuable resources. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Given the skills employers want, the traits we need in the next generation of leaders, and the qualities we value in our neighbors and friends, we might well ask the liberal arts grad, “What can’t you do with that?”

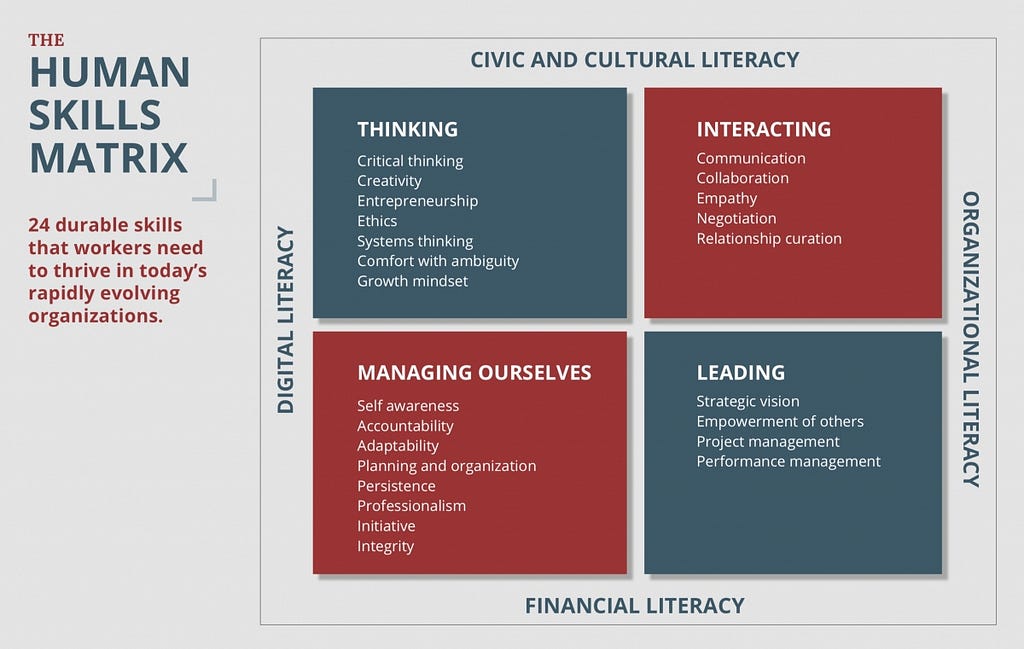

The main concern people have about liberal arts is marketability. Where are the jobs for people studying ancient Greek or African history? Everywhere. Because what those students are learning, alongside verb forms and dates, are the skills that appear time and again on top of employers’ wish lists. Skills such as persuasion, collaboration and creativity.

Does this mean that a liberal arts degree is as financially lucrative as computer science or petroleum engineering? No. But liberal arts majors do just fine in the workplace. Liberal arts students go on to earn good livings in a wide variety of fields, including technology.

In fact, the median annual income of a liberal arts major is just 8% lower than the median for all majors and more than one-third higher than the median income of people without a college degree.

Liberal arts offer not just financial value, but also personal, social and cultural values. The liberal arts take their name from the Latin word “liber,” which means “free.” Originally this referred to the education of free persons as distinct from slaves, but freedom is still at the root of the liberal arts. Liberal arts are a privilege of a free society, and the study of the liberal arts helps to keep us free.

Why is this? Contrary to what some would have us believe, our financial and social well-being depends on how we respond to the kinds of open-ended questions that liberal arts fields are asking. A computer scientist wants to invent a cool new app or technology. Whether he does a good job is measured by how much money his product earns.

As we see all too often, little thought is given to the social effects of these new technologies. They cause serious harm that people trained in writing computer code and making money may be unable or unwilling to address. Earnings can’t measure the things that most of us really care about when we think about new technologies.

This is where the liberal arts come in. The bedrock of a liberal arts education is the ability to understand a complex situation from many different viewpoints. To understand that the same information may look different to different people, or even to the same person at different times. We need the liberal arts to address questions that have no one right answer. And most of the important questions facing society are questions like this.

For instance, with all the technologies revolutionizing our society, how should we balance the need for accurate news and information with individual free speech? Where is the line between a legitimate business use of personal data and exploitation? Who gets to decide? So far, technology companies have done a lousy job of grappling with these questions. Some history majors, with their rich understanding of how complex forces shape society over time, would be a great idea.

Such skills have value in lots of places besides the workplace. The philosophy major on the church executive board is thinking about how the bedrock values of his community should inform decisions about replacing the roof or hiring a new Sunday school teacher. The English major participating in an environmental advocacy group can use her rhetorical and analytical skills to narrow the gap between the near-unanimous scientific consensus on climate change and political inaction on the issue.

The mistaken view that liberal arts are not financially valuable creates the more damaging idea that some fields of study have financial value, while others have social values. With liberal arts, we get both. Our society depends on it.

Deborah Beck is an associate professor of classics at The University of Texas at Austin.

A version of this op-ed appeared in The Hill .

Explore Latest Articles

Apr 23, 2024

Karen Willcox Winner of the 2024 Theodore von Kármán Prize

Apr 22, 2024

How Potatoes, Corn and Beans Led to Smart Windows Breakthrough

McCombs School of Business Honors Harkey Institute Donors

- 2023-24 Steering Committee

- Bibliography

- Advisory Board

- Publications

- Race, Racism, and the Liberal Arts

- Faculty Research Seminars

- Scholarly Promotion

- Podalot – The Aydelotte Podcast

- Interdisciplinary Initiatives Development Grant

- Curricular Grants

- Public Writing

- Student Research Fellows

- AF Faculty & Staff Dinner Discussions

- Higher Ed Reading Group

- AF Tuesday Cafe

- Cross-Institutional Teaching Collaborations

- Past Projects

- Get Involved

A Guide to the Discourse About Liberal Education

Some of our observations on the discursive categories we've identified..

Arguments about liberal arts accumulate slowly, almost imperceptibly, on the forest floor of higher education. The detritus of more than a century of episodes in the rhetorical life of liberal arts education, they are built up by cycles of the fierce argument, exuberant expansion, portents of doom, and beneficient forgetting that characterize modern higher education’s relation to the idea of the liberal arts.

Three years into our work as directors of the Aydelotte Foundation at Swarthmore College, we’re newly conscious of the provenance of these claims about liberal arts that circulate within the contemporary American public sphere, across the global span of higher education, and backwards in time. Some of these claims are newer; others have long histories.

Everyone seems to have a take on the liberal arts. College admissions officers, authors of , earnestly-written books that about the future of academia, former college presidents, higher ed policy-makers, interested journalists, college professors, high-school guidance counselors, Twitter randos, conservative pundits, ed tech executives , business leaders. All of them try to offer a definition of “liberal arts” as they speak to their audiences. The googleable history of the idea is recited dutifully: we are reminded of the trivium and quadrivium; the fateful meeting between the American college and German research university is rehearsed. But far more history is forgotten, ignored, or side-stepped. In place of history, we list the virtues of liberal arts in a vague and comforting way. They vacillate between a melancholic yearning for a lost form of liberal arts education and a blustery confidence in liberal arts as a weapon with which to meet an uncertain and slightly menacing future. But few offer a tangible definition of the concept of liberal arts, and therefore few offer much confidence.

Part of the problem with defining liberal arts is that the concept seems so open that almost everyone can claim to be profoundly identified with it. The term is so plastic that “liberal arts” frequently serves in public discourse as an all-purpose scornful stand-in for any number of tenuously related things: for higher education, for educated elites, for the opposite of useful or instrumental education, even for any political disposition even slightly to the left of the far right.

And yet we can see some some persistent lineages emerge from out of the sea of formless talk that invokes “liberal arts”. Each of those strains has ties to a specific history of practice and ideology within higher education or public culture. Some align closely and intentionally with a particular agenda; others seem like accidental creations. Some trace a consistent line across more than a century; others have seen their fortunes rise dramatically and fall precipitously over time. But each of the twelve propositions we’ve identified intrigue us; they offer the seeds of research projects of various scales and types that we hope to undertake and support.

By uncovering the conditions in which they came into being, expanding the institutional landscape, repopulating the narratives with a wider array of individual figures, and turning towards the intractable problems they often both mark and gloss over, we hope to uncover both some more concrete definitions, particular practices, and a wider world of what liberal arts education has been, is now, and might be in the future.

——————————————————–

A Deeper Look

Uncertainty. The view that liberal arts is the best possible response to uncertain futures of work and life is particularly common in 2018. But it has a long history, arguably reaching all the way back into the medieval university or classical era and their assumptions about what a “free man” required from education in order to rule himself and the world around him. In the nineteenth century when Harvard President Charles Eliot introduced the elective course into higher education, he argued in part that individuals needed to make their own choices about what to learn in the process of their own unpredictable personal journey through life. Since then, the definition of liberal arts as unpredictability has been tied both to this romantic vision of individual flourishing and to the sense that white-collar or professional employment requires some measure of adaptability and flexibility to unforeseen circumstances. Unpredictability in this sense is both a justification of a liberal arts approach and an explanation of the variability of the courses and majors available within a liberal arts curriculum. Rarely, however, do liberal arts faculty and administrators think deeply about whether unpredictable conditions of study produce (or even resemble) the capacity to navigate uncertain future contingencies in work and life .

Recombination. The idea that the liberal arts is about the freedom of individual learners to make their own choices about subjects and methods they wish to learn and then to combine what they know in original or distinctive ways is possibly the most comforting of all to students, parents, professors, college presidents and most of the public. The physicist who is also a virtuoso pianist, the philosopher who designs solar-powered cars, the Shakespeare expert who writes white papers on the epidemology of ebola, are guaranteed a place in their alumni magazines, in the hearts of the faculty that taught them, and in the MacArthur genius grants of tomorrow. As with unpredictability, Charles Eliot’s revisionary insistence on the elective as the heart of American higher education is an important part of this story. But it’s also difficult to really pinpoint the structures or approaches in contemporary liberal arts institutions that consciously engender these kinds of recombinant outcomes–and hard to shake the suspicion that other double majors, other students with uniquely conceived courses of study, never really reconcile or connect the divergent threads of their education; liberal arts institutions like the claim a share of the credit for the achievements of its graduates, yet rarely assume responsibility for their failures or disappointments. Nor is it easy to separate out the legacies of a four-year undergraduate education from later experiences that might more richly inform or shape a distinctive fusion of divergent forms of knowledge and skill in a given graduate.

Autodidactism. Almost as comforting is the proposition that liberal arts students “learn how to learn”, that they are acquiring meta-knowledge of disciplines, methods, and skills that sets them apart from people who have not had this kind of education. While many institutions design disciplinary and interdisciplinary structures to emphasize method and meta-knowledge, this claim appears as often in contexts where students encounter disciplines with fiercely specific and highly bounded methods; in this latter case, “learning how to learn” must arise from the proximity of different learning experiences or from the particular pedagogy of Like many assertions about liberal education, it’s difficult to separate from the abilities and social capital that many students carry into higher education from the benefits they reap from it four years later. It also can be difficult to clearly trace how separate disciplines that may hold themselves to have specific and highly bounded methods and epistemologies nevertheless produce this metaknowledge in liberal learners.

Critical Thinking. “Learning how to learn” is miles more specific and tangible than another very common claim, that liberal arts education is “critical thinking”. In a sense, “critical thinking” and “liberal arts” are a match made in heaven–that is, of two often-invoked ideas that can mean almost nothing and almost anything all at once, and that can in fact each mean something deeply important and brimming with potential. Thinking, slightly modified; the value-added imagined here is “critical,” which holds the bag for everything that education may be said to have done while also preserving an alibi. Critical thinking attempts to strip ideology and even any particular content away from the idea of liberal education; it invokes the autonomy of individuals, their ability to think independently of and about the conditions of their education.

Humanities. Critical thinking is therefore very different for those uses of liberal arts to mean humanities disciplines pure and simple – as often seen in far-right trolling (snowflake liberal arts majors) as well as in a more subtle, background assumption within the culture of academia itself. The association of the two is not unfounded: as Laurence Veysey points out, the defenders of “liberal learning” who armed themselves against the rise of the practical or utility-driven research university expressly identified themselves as humanists opposed to new disciplinary forms of scientific inquiry. In the swirl of current anxieties about science majors, those older views are sometimes pulled up as sediments that color ongoing conversations and deliberations with an irritable turbidity. At the same time, almost no one in the contemporary environment seriously advocates framing a liberal arts curriculum as an exclusively humanistic one.

Core Curriculum, Western Tradition. Though perhaps there is some element of that framing in various academic projects that define themselves as upholding “traditional” visions of the liberal arts: Columbia University’s Core Curriculum and St. John’s College’s “Great Books” approach, for example, as well as a number of religious colleges. With varying degrees of comfort, most of these institutional frameworks not only see themselves as defining liberal arts in terms of adherence to past approaches but even more specifically as connected to the “Western tradition”. Even for institutions that have no interest in defining liberal education in these terms, there is a seemingly unavoidable degree to which the concept references a specific history of teaching and institution-building in Western Europe. The rise of movements to decolonize or more thoroughly universalize university curricula are at least partially a result of this lingering connection. It’s hard to ignore the degree to which the defense of liberal arts is often undertaken by white male authors (both inside and outside of academia), but many of the virtues claimed for liberal learning as an approach have potential analogues in other historical traditions of formal education in East and South Asia and perhaps elsewhere. To us, at least, it feels as if the persistent, sometimes unspoken, connection between ideas about liberal learning and “the Western tradition” creates some unfortunate constraints on its future–but this is also a conversation so thoroughly implicated in long-standing culture wars that it is hard to engage it in a useful or interesting way.

Anti-Vocational. Far more interesting to us is the intricate, contradictory domain of claims about the relationship between liberal learning and the work that its graduates undertake subsequently in life. To a great extent, we think this is the single most interesting thread that we would like to unravel and trace. The proposition that a liberally educated person must not be intentionally prepared for a single specific career reverberates all up and down the timeline of liberal arts as an idea, though in radically different contexts in classical and medieval institutions, and even in the 19th Century American academy. No other idea produces so many invocations–and misrepresentations–of the classical and medieval conceptualization of the educated person. The history of higher education in the United States is a series of confrontations between practicality and philosophy, utility and character-building, specificity of professional training and generality of liberal learning. The contemporary American debate about higher education, whether staged on Twitter, in family living rooms, in diners, in legislatures, or in faculty meetings, is drawn compulsively to the question of whether and how higher education should prepare students for future careers, and whether or not it already does so in some fashion. These conversations criss-cross a riotous range of informed descriptions of the actual curricula and pedagogy of higher education, mythological visions of college in the past and present, unexamined assumptions about the process of learning, and anxious marginally-informed pronouncements about the present and future of work and social transformation. We’ve decided that this theme is our greatest area of current engagement for the Aydelotte: there is so much to interpret and study within this domain, and the answers are so urgent for the present moment. Status Quo. At least some working understandings of liberal arts, on the other hand, amount to a quiet and simple blank-check benediction for the status quo, either at particular colleges or universities or across academia. Meaning, when asked “what do you mean by ‘liberal arts’”, at least some institutions effectively answer by saying, “Whatever we’re doing this second? That’s liberal arts”. This is less shallow than it might seem: what this approach really means to say is that existing structures of faculty governance and administrative management are trustworthy custodians of the meanings and implementation of liberal arts, and that liberal education arises as an emergent form out of the interaction of their various decisions. Considering that contemporary anxieties about higher education are far less novel or unprecedented than they are frequently described as being, it makes a certain kind of sense to serenely assert a kind of custodial duty to liberal learning and to carry on with that duty without being overly distracted by any given moment of supposed controversy or threat. Small Colleges. In a similar vein, there are more than a few definitions of liberal arts that simply assert that the term is defined not by concepts or histories but that it is a proxy for a specific kind of institution, namely small American colleges that are focused substantially or entirely on undergraduate education. The common acronym SLAC expresses this neatly: “small liberal-arts college”. This seems to us to be both true enough (that the term tends to invoke small colleges) and completely uninteresting. If liberal arts is simply a synonym for selective small colleges that collectively educate only a teeny fraction of the students graduating with bachelor’s degrees in the United States, it certainly cannot carry the weight of all the other expectations and anxieties that surround it.

Citizenship. Finally, we’re interested in but also puzzled by a powerful, long-standing idea about liberal education that often haunts almost every other invocation of the concept. Namely, that liberal learning is peculiarly suited to the formation of character, the shaping of morality, or the creation of civic virtue. This is a proposition of long-standing, beloved by college presidents in 1875, 1925, and 2018, even if some of the descriptive vocabulary of virtues attributed to liberal learning shifts over time. “Ethical intelligence”, “global citizenship”, “social justice”, are in some sense the descendants of other virtuous attributes that colleges and universities claimed to hone or awaken in young people a century earlier. These claims puzzle us because in some sense they propose an empirical standard that perhaps unsurprisingly educational institutions have been in no hurry to test or examine further. Are graduates of liberal arts institutions better citizens by some measure? (And what would be “better”?) Are they ethically intelligent? (Are scholars who study ethics, for example, in any sense more likely to be ethical?) Any of these questions, if they could be answered in the affirmative through any kind of evidence of any kind, would pose a second set of questions: what is it about liberal education that is producing such an outcome? How do we know this isn’t better described as “class formation”? (Which, if it were, would not be self-evidently bad to everyone who expresses it–it’s just that that would be different than what educational institutions commonly imagine as their intentional practices.) We recognize that there are many interesting sentiments and histories bubbling under the surface of these kinds of claims, but for the moment, we are inclined to push them aside until we can think of a way to tackle them usefully.

Character. This theme could also just as easily be titled “social or class reproduction”. Higher education outside the United States has been more explicit regarding this as a function of the university. The major public university systems of many European countries and their former colonies have long used qualifying examinations and other mechanisms to sort young adults into overtly class-linked hierarchies closely connected to particular kinds of employment. A small fragment of institutions that have conventionally described themselves as training for elite government and corporate leaders and a handful of esteemed professions, such as Oxford, Cambridge or the Sorbonne, have claimed to be involved in building “character”, a sort of mannerly public morality that once upon a time stretched from how to behave on the polo field or while eating ortolans to how to act in public when your spouse has an affair or when feeling in middle age that life has ceased to have joy and meaning. Some tie to older ideas of liberal education–the training of a ‘free’ citizen–has been visible within this commitment to cultivating character.

“Character” in the American academy has a more complicated and tortured history. As Veysey observes, the ascendant research university in the latter half of the 19th Century set itself against the “liberal education” of many private and religious institutions by promising that the research university was open to all citizens, and could offer to all students a kind of socioeconomic mobility untainted by “character”. A student could learn the arts and skills needed by a fast-paced industrial society, skills whose value could be stripped of the need for embedded or inherited cultural capital. With those skills, a graduate’s horizon was said to be unlimited. Veysey notes that for a good while, the response of the defenders of liberal education to this critique was not to deny the accusation but to embrace it, to agree that liberal education did in fact refine and extend the social virtues of the scions of elite or haut-bourgeois families. Nevertheless, in the early 20th Century, many small college and private universities adopted some of the features of the research university and with them began to scuff over or obscure the degree to which character and social standing were synonymous or connected, either by extending the benefits of character to anyone who might matriculate or preaching the importance of character to the proper use of professional or technical skills.

The link between liberal learning and the shaping of character–or many related ways to describe some combination of manners, ethics, behavior and affect–has remained strong up to the present in American higher education even as that connection also produces discomfort, embarrassment and anger. A prominent strain of criticism of the contemporary academy by writers like Mark Edmundson and William Deresiewicz complains of the extent to which higher education has abandoned the forging of character. Many make the opposite charge: that liberal learning is still tied too closely to the reproduction of the specific cultural identity of an older white, male establishment elite and hostile to everyone else. Faculty and administrators often look desperately for ways to renarrate or redescribe ‘character’ either as a technical-philosophical skill (“emotional intelligence”, “self-presentation”, “ethical intelligence”, “cultivating humanity”) or to re-situate it within larger and more open social formations (“global citizenship”, “cosmopolitanism”, “pluralism”).

At the same moment, the undeniably intensified role of higher education in producing social class in the United States has become a profoundly unsettling subject within academia and an explicit premise of public conversation about academia, not to mention an important underpinning of recent American politics. Here the theme of anti-vocationalism gets a particularly intense inflection from its relationship to both character-producing and class-producing visions of liberal education. So this is an area of both strength and weakness within the body politic of academia that we intend to persistently explore and prod at even as we are also aware of the jangled nerves and knotted musculature that flinch as a result of such prodding.

This taxonomy of “liberal arts” and its meanings is both a product of research and a guide to research. We can see meanings of the term that are banally or historically shallow, and others that have a tendency to be anodyne or superficial. We see others that are zones of heavy, if often unreflective, contention both within academia and between academia and its myriad publics. It is enough to keep us occupied for a long time; we hope with some useful results.

Timothy Burke's main field of specialty is modern African history, specifically southern Africa, but he has also worked on U.S. popular culture and on computer games.

- Timothy Burke

- Higher Education

- Liberal Arts

- Uncertainty

- Share via Facebook

- Share via Twitter

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via Email

What Does Liberal Arts Mean?

A liberal arts education offers an expansive intellectual grounding in all kinds of humanistic inquiry.

By exploring issues, ideas and methods across the humanities and the arts, and the natural and social sciences, you will learn to read critically, write cogently and think broadly. These skills will elevate your conversations in the classroom and strengthen your social and cultural analysis; they will cultivate the tools necessary to allow you to navigate the world’s most complex issues.

A liberal arts education challenges you to consider not only how to solve problems but also trains you to ask which problems to solve and why, preparing you for positions of leadership and a life of service to the nation and all of humanity. We provide a liberal arts education to all of our undergraduates, including those who major in engineering.

As President Christopher Eisgruber, Class of 1983, stated in his 2013 installation address: “[A] liberal arts education is a vital foundation for both individual flourishing and the well-being of our society.”

A commitment to the liberal arts is at the core of Princeton University's mission.

This means:

Princeton is a major research university with a profound and distinctive commitment to undergraduate education.

Our curriculum encourages exploration across disciplines, while providing a central academic experience for all undergraduates.

You will have extraordinary opportunities at Princeton to study what you are passionate about and to discover new fields of interest.

Students who elect to major in the natural sciences or engineering, for example, also take classes in history, languages, philosophy, the arts and a variety of other subjects.

You could major in computer science and earn a certificate in theater. Or major in African American studies and earn a certificate in entrepreneurship. Many other options are possible through the range of Princeton's concentrations and interdisciplinary certificate programs.

You will be exposed to novel ideas inside and outside the classroom that may change your perspective and broaden your horizons.

We value learning and research as a source of personal discovery and fulfillment — as a pleasurable and enlightening experience in its own right. But it is also a means to an end, in preparing you to live a meaningful life in service to the common good.

Your Princeton education will facilitate your progress along whatever path you choose to pursue, and you will continually rely on what you learned here in your career and in your life.

Our graduates are prepared to address future innovations and challenges that we may not be able to even imagine today.

We hope you will take time to explore how a commitment to the liberal arts is part of what makes Princeton special. Consider our 30+ m ajors and 50+ minors ; discover the research conducted by our distinguished faculty; engage with the range of superlative visiting scholars and artists we invite to campus each year; and imagine the quality of conversations you’ll be able to have with your professors and your peers.

Humanities Sequence

In Princeton's yearlong humanities sequence—team-taught by professors from a variety of academic disciplines—undergraduates are immerse in texts that span 2,500 years of civilization.

Integrated Science Curriculum

Integrated Science is a revolutionary introductory science curriculum intended for students considering a career in science. This year-long course prepares first-year students for a major in any of the core sciences while bridging meaningfully across other disciplines.

Engineering Studies

The School of Engineering and Applied Science challenges students to both solve problems and understand which problems are important by emphasizing fundamental principles of engineering with their connections to society.

I came to Princeton because I wanted a liberal arts education that would enable me to pursue multiple interests rigorously and deeply. I concentrated in physics, but the courses that most shaped my intellectual life were in constitutional law, political theory and comparative literature.

- Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83, Princeton University president

- Skip to main content

Life & Letters Magazine

The Value of the Liberal Arts

By Hina Azam September 20, 2022 facebook twitter email

Those of us who teach in liberal arts colleges are passionate about the value of a liberal arts education. But for those outside of academia – even for those who might have received a degree in UT’s College of Liberal Arts – the precise meaning of “liberal arts” can be murky. What, exactly, is meant by the “liberal arts”? What is the history of the idea, and how does it translate into the educational concept we know as a “liberal-arts curriculum,” or, more broadly, a “liberal education”? What is the value of a liberal arts education to both individual and collective life? This essay presents a brief overview of the idea, history, purposes, and values of liberal arts education, so that you, our readers, may understand the passion that inspires our faculty’s teaching and scholarship, and be similarly inspired.

What are the Liberal Arts?

The idea of the liberal arts originates in ancient Greece and was further developed in medieval Europe. Classically understood, it combined the four studies of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music – known as the quadrivium – with the three additional studies of grammar, rhetoric, and logic – known as the trivium . These artes liberales were meant to teach both general knowledge and intellectual skills, and thus train the mind. This training of the mind as well as this foundational body of content knowledge and intellectual skills was regarded by scholars and educators as necessary for all human beings – and especially a society’s leaders – in order to live well, both individually and collectively.

These liberal arts were distinguished from vocational or clinical arts, such as law, medicine, engineering, and business. These latter were conceived as servile arts – i.e. arts that served concrete production or construction. These productive/constructive arts were also known as artes mechanicae , “mechanical arts,” which included crafts such as weaving, agriculture, masonry, warfare, trade, cooking, and metallurgy. In contrast to the vocational or mechanical arts, the liberal arts put greater weight on intellectual skills – the ability to think and communicate clearly, and to analyze and solve problems. But more distinctively, the liberal arts emphasized learning and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, independent of immediate application. The liberal arts taught not only bodies of knowledge, but – more dynamically – how to go about finding and creating knowledge – that is, how to learn. Finally, the liberal arts taught not only how to think and do, but also how to be – with others and with oneself, in the natural world and the social world. They were thus centrally concerned with ethics.

Notably, the term “liberal arts” has nothing to do with liberalism in the contemporary political or partisan sense; the opposite of “liberal” here is not “conservative.” Rather, the term goes back to the Latin root signifying “freedom,” as opposed to imprisonment or subjugation. Think here of the English word “liberty.” The liberal arts were historically connected to freedom in that they encompassed the types of knowledge and skills appropriate to free people, living in a free society. The term “art” in this phrase also must be understood correctly, for it does not refer to “art” as we use it today in its creative sense, to denote the fine and performing arts. Rather, from the Latin root ars , “art” is here used to refer to skill or craft. The “liberal arts,” then, may be thought of as liberating knowledges, or alternatively, the skills of being free.

What is a Liberal Arts Education ?

A liberal (arts) education is a curriculum designed around imparting core knowledge and skills through engagement with a wide range of subjects and disciplines. This core knowledge is taught through general education courses typically drawn from the humanities, (creative) arts, natural sciences, and social sciences. The humanities include disciplines such as language, literature, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy, religion, history, law, geography, archaeology, anthropology, politics, and classics. Natural sciences include subjects such as geology, chemistry, physics, and life sciences such as biology. Social sciences comprise disciplines such as sociology, economics, linguistics, psychology, and education. Through a core curriculum or general education courses, students gain a basic knowledge of the physical and natural world as well as of human ideas, histories, and practices.

A liberal arts education comprises more than learning only content, but also honing skills and cultivating values. Intellectual and practical skills at the heart of the liberal arts are reading comprehension, inquiry and analysis, critical and creative thinking, written and oral communication, information and quantitative literacy, teamwork and problem-solving. Values that are central to liberal education are personal and social responsibility, civic knowledge and engagement, intercultural knowledge and competence, ethical reasoning and action, and lifelong learning.

Why a Liberal Education? Purposes and Values

Four overarching purposes anchor the idea of an education in the liberal arts. One of those is liberty . As mentioned above, the traditional idea of the liberal arts was an education that befitted a free person, one who was fit to participate freely in the life of society. The modern casting of this idea is that a broad education does not limit one to a particular profession or occupation, but rather, is meant for any life path – it prepares the mind for a variety of possible futures and for constructive participation in a civil democratic society. The interconnection between liberal education and human freedom cannot be over-emphasized, and it was at the forefront of the minds of the great political theorists and educators of the western tradition. Those with insufficient knowledge and skills would easily fall prey to demagogues and agents of chaos, and pervasive ignorance and lack of intellectual skill would eat away at a polity’s foundations. Only an informed citizenry – who had familiarity with and foundational understanding in the major areas of knowledge, and who had the requisite skills to both process existing information and seek out reliable new information – would be able to uphold and maintain a democratic society and stave off a decline into tyranny and despotism. As Thomas Jefferson, a major architect of the American public university, held, “Wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government.” [1]

Another central purpose of a liberal arts education is the inculcation of the principle of human worth. This purpose is built on values collectively known as humanism : the idea that human life, individual and collective, has intrinsic value; the idea that human beings are endowed with rights to life, liberty, property, and a number of other rights that we know as “human rights”; that human beings are fundamentally equal, even if they are not the same, and that that equality should translate into both political and legal equality. This ideal of humanism is not in opposition to religious beliefs and practices; however, it regards the public sphere as one in which all should be able to participate regardless of religious beliefs and practices. Humanism mirrors the principle of a common or shared humanity, even while recognizing differences of experience, perspective, and resources. This vision is at the heart of that facet of liberal arts known as the humanities . Writes Robert Thornett, “Humanities is, in fact, education in how to be a human being.” [2] A liberal arts education exposes learners to diverse types of knowledge – which allow for understanding and empathy with others – within a humanistic framework that aims for deeper unity and synthesis. This approach to knowledge serves as a bulwark against social, political and ideological forces that seek to drive wedges between human beings, and that all too often culminate in violence and oppression.

A third purpose of liberal education is to provide a space for contemplation of truth and virtue , based on the conviction that such contemplation is necessary for the free mind, and that informed explorations of these notions lead to the formation of better human beings. The liberal arts are where students have opportunity to consider the “big questions”: What is true? What is good? What is just? What is beautiful? This contemplation is what fires the imaginations of our students, and what makes the liberal arts curriculum unlike any other curriculum. Vartan Gregorian explains the unique character of liberal arts education, writing that “the deep-seated yearning for knowledge and understanding endemic to human beings is an ideal that a liberal arts education is singularly suited to fulfill.” [3]

A fourth value of liberal arts education is its emphasis on the skills of learning , and of constructing knowledge out of information. We live in an increasingly complex information environment, where the sheer quantity of information – and its intentional manipulation into disinformation – overwhelms people’s abilities to make sense of it all. Without sufficient training, people are less equipped to find reliable information, to understand what they encounter, and to process that information, mentally and emotionally, into rational knowledge that can form the basis of ethical evaluation and action . This is a matter of grave importance for all human beings – in their capacity as students, citizens, consumers, workers, and people in relationships. Gregorian long ago identified the problem of information overload, and the function of education, in an interview with Bill Moyers: “Unfortunately, the information explosion … does not equal knowledge. … So, we’re facing a major problem: how to structure information into knowledge. Because … there are great possibilities of manipulating our society by inundating us with undigested information… paralyzing our choices by giving so much that we cannot possibly digest it.” [4]

Given this paralyzing deluge of information, he continues, “The teaching profession, the universities, have to provide connections … connections between subjects, connections between disciplines … to provide some kind of intellectual coherence.” In the final analysis, suggests Gregorian, “Education’s sole function is now, possibly, [to] provide an introduction to learning.”

The purposes and values outlined above cannot easily be fulfilled outside of an intentional liberal arts curriculum. One does meet people who are driven to read widely and to pursue lifelong learning; to develop skills of information critique and lucid oral and written communication; to hold steadily to the vision of a shared humanity and humane ethical conduct; to undertake the ethical burden of preserving political liberties and civil rights; to engage in sustained contemplation of truth and practice of virtue; to perceive the interconnectedness of different spheres of knowledge and therefore of our world; and to develop the facility to synthesize chaotic data and irrational information into rational and cogent knowledge. But these goals are far more difficult to achieve outside of the structured, collective, and compulsory activities of the college classroom and away from teachers whose minds are perpetually set to these concerns. For too many, such integrated learning is out of reach or undervalued. Meanwhile, the insufficient attainment and integration of broad knowledge, intellectual skills, and ethical reflection is wreaking havoc on our society and national culture; on our quality of life morally, intellectually, psychologically, and physically; and finally, on our planet, which is increasingly unable to withstand humanity’s relentless onslaught and is fast losing the capacity to sustain its assailant.

Liberal-arts education is not found in any one course, classroom, or teacher. It is a composite formation, attained over time through series of courses and learning opportunities that together coalesce in the minds of students. Each instructor, and each course, contributes elements that are oriented toward the purposes identified above. It is through the process of seeing the interconnections between different areas of knowledge, using diverse intellectual skills, that the human mind gains the capacity for liberation.

[1] https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/genesis-university-virginia

[2] Robert Thornett, “What Are College Students Paying For?” at The Quillette , June 2, 2022 [ https://quillette.com/2022/06/02/what-are-college-students-paying-for-the-stephen-curry-effect-and-getting-back-to-basics/

[3] Historian and former Brown University President Vartan Gregorian, in his essay “American Higher Education: An Obligation to the Future” at https://higheredreporter.carnegie.org/introduction/ .

[4] “Vartan Gregorian: Living in the Information Age,” interview with Bill Moyers, at https://billmoyers.com/content/vartan-gregorian/ .

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: harvard yard closed to the public.

Please note, Harvard Yard gates are currently closed. Entry will only be permitted to those with a Harvard ID via Johnston, Thayer, Widener, Sever and Solomon (Lamont) Gates. Guests are not allowed.

Last Updated: April 25, 2:24pm

Open Alert: Harvard Yard Closed to the Public

back of male student shown wearing a backpack and walking into class, up close of students in class, female professor teaching, students in lab coats, side view of the classroom with a female professor

Liberal Arts & Sciences

Plan Your Academic Journey

The undergraduate degree is designed with flexibility in mind: you set your own academic goals, and we'll help you plan coursework to meet them—while also ensuring you receive a broad liberal arts and sciences education.

Liberal Arts & Sciences Education

Academic exploration across disciplines.

As former President Lawrence Bacow stated in his 2018 installation address, “Given the necessity today of thinking critically… a broad liberal arts education has never been more important.”

What is a "liberal arts & sciences" education?

Commitment to liberal arts & sciences is at the core of Harvard College’s mission: before students can help change the world, they need to understand it. The liberal arts & sciences offer a broad intellectual foundation for the tools to think critically, reason analytically and write clearly. These proficiencies will prepare students to navigate the world’s most complex issues, and address future innovations with unforeseen challenges. Shaped by ideas encountered and created, these new modes of thinking will prepare students for leading meaningful lives, with conscientious global citizenship, to enhance the greater good.

Harvard offers General Education courses that show the liberal arts and sciences in action. They pose enduring questions, they frame urgent problems, and they help students see that no one discipline can answer those questions or grapple with those problems on its own. Students are challenged to ask difficult questions, explore unfamiliar concepts, and indulge in their passion for inquiry and discovery across disciplines.

Concentrations

You have many options when pursuing your Harvard degree. We offer more than 3,700 courses in 50 undergraduate fields of study, which we call concentrations. A number of our concentrations are interdisciplinary.

Double Concentrations

For students interested in deeply pursuing two areas of study, the option to declare a double concentration was added in the 2022-2023 academic year. Double concentrations allow students to pursue two distinct, in-depth paths of study that do not substantially overlap. Students who pursue a double concentration do not need to write a senior thesis unless one of the fields of study is an honors-only field.

Joint Concentrations

A joint concentration allows students to combine two fields that are each an undergraduate concentration and integrate them into a coherent field of study. Joint concentrations culminate with an interdisciplinary senior thesis written in one of the concentrations only. In essence, joint concentrations allow an undergraduate to blend two concentrations into one cohesive unit of classes.

Special Concentrations

Special concentrations allow you to craft a degree plan that meets a uniquely challenging academic goal. This could be an unprecedented area of research or a combination of disciplines not covered by our current offerings.

To create your own special concentration, you must submit a petition to the Standing Committee on Special Concentrations, which reviews each plan of study on an individual basis.

Harvard College Curriculum

Approximately a third of courses towards your degree fulfill Harvard College requirements. This includes classes in the areas of General Education, Distribution, Quantitative Reasoning with Data, Expository Writing, and Language.

“We want Gen Ed to be the kind of courses faculty have always dreamed of teaching — and the kind students never forget.”*

For detailed explanations of academic requirements, consult the Harvard College Curriculum .

Components of your degree

General education.

Harvard's Program in General Education connects students to the world beyond the classroom by focusing on urgent problems and enduring questions. Students take one course in each of four categories: Aesthetics & Culture; Ethics & Civics; Histories, Societies, Individuals; as well as Science & Technology in Society.

Distribution

The distribution requirement exposes students to the range of scholarly disciplines offered at Harvard. Students take one course in each of the three main divisions of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences: Arts and Humanities; Social Sciences; as well as Science, Engineering, and Applied Sciences.

Quantitative Reasoning with Data

Quantitative Reasoning with Data courses teach students how to think critically about data. Students learn the computational, mathematical, and statistical techniques needed to understand data. They’ll also learn how to use those techniques in the real world, where data sets are imperfect and incomplete, sometimes compromised, always contingent. Finally, they’ll reflect on all the questions raised by our current uses of data — questions that are social and ethical and epistemological.

Expository Writing

The writing requirement is a one-semester course offered by the Harvard College Writing Program that focuses on analytic composition and revision. Expos courses are taken as first-year students and are taught in small seminars focusing on writing proficiency in scholarly writing. Students meet one-on-one with instructors (called preceptors) regularly to refine writing skills. Depending on the result of the summer writing placement exam, some students take a full year of Expos.

Students may take a year-long (eight credit) or two semester-long (four credits each) courses in a single language at Harvard. Courses taken abroad may also be considered with prior approval. Students who study language at Harvard will have their record updated upon successful completion of the coursework. A list of the foreign languages offered at Harvard can be found on the Arts and Humanities website .

*Quote by: Amanda Claybaugh, Dean of Undergraduate Education

Study Spaces

Looking for comfortable furniture to study on? A room where you can meet with a group? A private desk in an open space? Or maybe just a printer near your next class?

Other Academic Opportunities

Harvard College offers several opportunities for you to pursue your academic goals.

Secondary Fields

In addition to your concentration, you can pursue a secondary field (sometimes called a minor at other institutions). There are currently 50 secondary fields. A secondary field is an excellent way to expand your education into multiple intellectual interests. Work with your adviser to develop a plan of study that matches your goals.

Language Citation

Undertaking advanced study in an ancient or modern language gives you a unique perspective the literature, history, and viewpoints of another culture. Each language citation program consists of four courses of language instruction beyond the first-year level, including at least two courses at the third-year level or beyond.

Independent Study

Independent Study allows for academic inquiry not available through regular coursework—such as an interdisciplinary investigation, an arts practice or performance study, or a field research project. Speak with your adviser to find out if this option is a good fit for you.

Fourth Year Master's Degree

Students can apply to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for a master's degree in select fields of study during their fourth year at Harvard through the Concurrent Master's Program.

Enroll at Affiliated Institutions

Harvard undergraduates can take classes at one of Harvard's ten graduate schools or cross-enroll at other Boston-area institutions.

About half of all Harvard students choose an honors track within their concentration, and most of these write senior theses or complete research projects under the supervision of professors and departmental tutors.

Dual Degree Music Programs

If you are a talented musician and dedicated scholar choosing between in-depth music training and a liberal arts education, you can apply to Harvard College’s dual degree programs with the New England Conservatory (NEC) and Berklee College of Music.

Study Abroad

Escape the bubble and expand your horizons by enrolling at a foreign university for up to a full year. The Office of International Education can help you discover how study abroad can fit into your plan of study.

Learn More About Harvard

Join our email list to download our brochure and stay in touch.

Related Topics

Reading and examination period.

Harvard is committed to supporting students and providing them with information, tips, and resources as they enter Reading and Examination Period.

Residential Life

Residential Life at Harvard provides the opportunity to develop your own community through shared experiences.

As a Harvard student, you have access to several different advising resources - all here to support your intellectual, personal, and social growth.

Toggle Academics Submenu

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

The enduring relevance of a liberal-arts education

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

The relevance, cost and value of a college education have been hot topics lately on various media platforms. The discussion often seems to be just an exchange of point-counterpoint broadsides among proponents and opponents of a liberal-arts education.

As president of a liberal-arts college, I won’t pretend to be neutral. I have benefited from, and believe in, studying the distinctive blend of the humanities, science and the arts that is the essence of a liberal-arts education. In fact, I recently wrote a letter to the editor of The New York Times defending the humanities as part of a well-rounded education.

I believe a liberal-arts education is the best preparation a young person can have for success in life. The mission of most liberal-arts colleges is to educate the whole person rather than training graduates to succeed at specific jobs that employers may be seeking to fill at a certain point in time.

As I said in my letter, we prepare students to lead meaningful, considered lives, to flourish in multiple careers, and to be informed, engaged citizens of their communities and the world. By studying languages and literature, for example, students gain insight into other cultures, and learn to see the world from multiple perspectives. In a global economy, those are powerful assets.

Critics occasionally concede that these are merits of a liberal-arts education. But they argue that it costs too much, is inherently impractical, and does not prepare students to get jobs immediately after graduation. Some experts and government officials advocate for students to pursue a much narrower college curriculum targeted at a clearly defined career opportunity.

This dichotomy was explored in a thought-provoking article in The Wall Street Journal by Peter Cappelli of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. After outlining the ways many colleges are responding to concerns about cost and career benefits by creating new, specialized courses that teach skills students will need in the workplace, Professor Cappelli wrote:

It all makes sense. Except for one thing: It probably won’t work. The trouble is that nobody can predict where the jobs will be—not the employers, not the schools, not the government officials who are making such loud calls for vocational training. The economy is simply too fickle to guess way ahead of time, and any number of other changes could roil things as well. Choosing the wrong path could make things worse, not better.

He went on to make some sensible recommendations about how parents and students can get the most out of a college education.

One point that comes up frequently in articles both for and against the liberal arts is that some surveys show a large majority of employers rating the college graduates they hire as unprepared or under-prepared for their jobs.

That is no surprise. The more telling point is that employers remain far more likely to hire college graduates. The unemployment rate for college graduates remains much lower than for high-school graduates, while college grads’ earnings are significantly higher. That has been the case for years.

As for preparedness, every new job—from dishwasher to CEO—comes with a learning curve. In my experience, employers value employees who work hard, learn quickly, know how to teach themselves, and bring knowledge, insight and creativity to their jobs.

Those are the qualities that liberal-arts colleges foster. We teach our students to become lifelong learners who are their own best teachers. We teach them to take intellectual risks and to think laterally—to understand how the humanities, the arts and the sciences inform, enrich and affect one another. By connecting diverse ideas and themes across academic disciplines, liberal-arts students learn to better reason and analyze, and to express their creativity and their ideas. They are capable of thinking and acting globally and locally.

Those attributes are worth attaining to lead a more fulfilling life. But they are also critically important for our graduates’ future success in this globalized, technologically driven economy. A survey last April of 318 executives at private-sector companies and nonprofit organizations underscored the importance of the liberal arts. It showed that the attributes of liberal-arts graduates are exactly what those leaders value in their employees and seek in the people they hire. Four out of five employers said each college graduate should have broad knowledge in the liberal arts and sciences.

Why? Because possessing broad, deep knowledge and skills and the ability to think flexibly and creatively is more important than ever before. Studies show that current college graduates will likely change careers 15 times in their lives, and are likely to make 11 career changes before turning 40.

That is why Oberlin and many other liberal-arts colleges have strengthened their career-services offices in recent years to help students put the knowledge and critical-thinking skills they acquire to good use. Colleges also encourage students from their first days on campus to pursue internships and other career opportunities.

But preparing students for one specific job is risky because of how quickly the economy and the job market can change. To use a Wall Street-related analogy, preparing for one specific job is similar to investing heavily in a single stock based on its past performance—widely considered a bad investment strategy. Diversification, spreading the risk across a variety of sectors and investments, is a more judicious approach.

It’s true that providing students a top-quality liberal-arts education in a residential setting is costly. At most liberal-arts colleges, we not only educate our students—we house and feed them, and provide for their health and well-being. And demand from students and their families for support services keeps growing. Providing those things is expensive.

At the same time, most liberal-arts schools are striving to reduce expenses, to be affordable, and to minimize students’ exposure to debt by providing financial aid. For colleges, this is a difficult financial balancing act.

But the breadth and depth of the education provided by good liberal-arts colleges offers unique advantages to undergraduates. Classes are smaller than at large research universities. Students usually study with full professors, not graduate students or adjuncts. Opportunities for independent research are more readily available. Students are better able to shape their own courses of study across traditional academic disciplines.

Residential liberal-arts colleges also offer their students educational opportunities outside of the classroom. At every liberal-arts college, the curriculum is enriched and enhanced by extra-curricular and co-curricular offerings, including myriad student organizations, lectures, films, concerts, recitals, exhibitions, symposia, and health and wellness and athletic events that occur every semester.

Is the expense worth it? And what about the possibility that a student and his or her family might incur debt to help pay for college?

Those are tough questions. I believe the expense is worth it. Study after study shows college graduates will earn significantly more over their lifetimes than their peers who do not get college degrees. And, yes, I’m aware that Bill Gates did not graduate from college and has done quite well financially. But it’s fair to say he is exceptional.