Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Effects of Social Media — Censorship In Social Media

Censorship in Social Media

- Categories: Censorship Effects of Social Media Social Media

About this sample

Words: 812 |

Published: Apr 29, 2022

Words: 812 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Works Cited

- Anat, Z. & Fernadez, W. (2016). Countering violent extremism on social media: An analysis of communication campaigns. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5406-5423. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5345/1718

- DeNardis, L., & Hackl, A. M. (2015). Internet fragmentation: An overview. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Flew, T. (2015). Communication and social media. Oxford University Press.

- Gibson, R. (2019). Freedom of speech and the limits of social media censorship. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/freedom-of-speech-and-the-limits-of-social-media-censorship-125726

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

- Hasen, R. L. (2016). Facebook and the new face of media regulation. The University of Chicago Law Review Online, 83, 37-43. https://lawreview.uchicago.edu/sites/lawreview.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/83_u_chi_l_rev_online_37.pdf

- Howard, P. N., Agarwal, S. D., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). When do states disconnect their digital networks? Regime responses to the political uses of social media. The Communication Review, 14(3), 216-232.

- Jørgensen, H. (2018). Facebook and democracy: In defence of an extended understanding of freedom of expression. Information, Communication & Society, 21(10), 1388-1403.

- Mossberger, K. (2008). Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Georgetown University Press.

- Stevenson, J. (2000). Freedom of speech: The history of an idea. Penguin.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1430 words

4 pages / 1828 words

3 pages / 1269 words

2 pages / 737 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Effects of Social Media

Subrahmanyam, K., & Smahel, D. (2011). Digital youth: The role of media in development. Springer Science & Business Media.Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.Kim, J., & Lee, J. [...]

In recent years, the social media platform TikTok has taken the world by storm, garnering millions of users and reshaping the landscape of online content creation. However, it has also faced its fair share of controversies and [...]

In today's digital age, children are growing up with unprecedented access to technology and social media platforms. Among these platforms, TikTok has gained immense popularity. This essay delves into the influence of TikTok on [...]

The media, in its various forms, plays a pivotal role in shaping our understanding of the world, including our perceptions of crime. Whether through news coverage, television shows, or social media, the media has the power to [...]

Social media creates a dopamine-driven feedback loop to condition young adults to stay online, stripping them of important social skills and further keeping them on social media, leading them to feel socially isolated. Annotated [...]

Some may argue that social media can affect someone’s mental health whereas others may oppose this view and claim there is no correlation between either. The two social media play massive parts in every aspect of our lives [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Democracy, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression: Hate, Lies, and the Search for the Possible Truth

- Share Chicago Journal of International Law | Democracy, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression: Hate, Lies, and the Search for the Possible Truth on Facebook

- Share Chicago Journal of International Law | Democracy, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression: Hate, Lies, and the Search for the Possible Truth on Twitter

- Share Chicago Journal of International Law | Democracy, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression: Hate, Lies, and the Search for the Possible Truth on Email

- Share Chicago Journal of International Law | Democracy, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression: Hate, Lies, and the Search for the Possible Truth on LinkedIn

Download PDF

This Essay is a critical reflection on the impact of the digital revolution and the internet on three topics that shape the contemporary world: democracy, social media, and freedom of expression. Part I establishes historical and conceptual assumptions about constitutional democracy and discusses the role of digital platforms in the current moment of democratic recession. Part II discusses how, while social media platforms have revolutionized interpersonal and social communication and democratized access to knowledge and information, they also have led to an exponential spread of mis- and disinformation, hate speech, and conspiracy theories. Part III proposes a framework that balances regulation of digital platforms with the countervailing fundamental right to freedom of expression, a right that is essential for human dignity, the search for the possible truth, and democracy. Part IV highlights the role of society and the importance of media education in the creation of a free, but positive and constructive, environment on the internet.

I. Introduction

Before the internet, few actors could afford to participate in public debate due to the barriers that limited access to its enabling infrastructure, such as television channels and radio frequencies. 1 Digital platforms tore down this gate by creating open online communities for user-generated content, published without editorial control and at no cost. This exponentially increased participation in public discourse and the amount of information available. 2 At the same time, it led to an increase in disinformation campaigns, hate speech, slander, lies, and conspiracy theories used to advance antidemocratic goals. Platforms’ attempts to moderate speech at scale while maximizing engagement and profits have led to an increasingly prominent role for content moderation algorithms that shape who can participate and be heard in online public discourse. These systems play an essential role in the exercise of freedom of expression and in democratic competence and participation in the 21st century.

In this context, this Essay is a critical reflection on the impacts of the digital revolution and of the internet on democracy and freedom of expression. Part I establishes historical and conceptual assumptions about constitutional democracy; it also discusses the role of digital platforms in the current moment of democratic recession. Part II discusses how social media platforms are revolutionizing interpersonal and social communication, and democratizing access to knowledge and information, but also lead to an exponential spread of mis- and disinformation, hate speech and conspiracy theories. Part III proposes a framework for the regulation of digital platforms that seeks to find the right balance with the countervailing fundamental right to freedom of expression. Part IV highlights the role of society and the importance of media education in the creation of a free, but positive and constructive, environment on the internet.

II. Democracy and Authoritarian Populism

Constitutional democracy emerged as the predominant ideology of the 20th century, rising above the alternative projects of communism, fascism, Nazism, military regimes, and religious fundamentalism . 3 Democratic constitutionalism centers around two major ideas that merged at the end of the 20th century: constitutionalism , heir of the liberal revolutions in England, America, and France, expressing the ideas of limited power, rule of law, and respect for fundamental rights; 4 and democracy , a regime of popular sovereignty, free and fair elections, and majority rule. 5 In most countries, democracy only truly consolidated throughout the 20th century through universal suffrage guaranteed with the end of restrictions on political participation based on wealth, education, sex, or race. 6

Contemporary democracies are made up of votes, rights, and reasons. They are not limited to fair procedural rules in the electoral process, but demand respect for substantive fundamental rights of all citizens and a permanent public debate that informs and legitimizes political decisions. 7 To ensure protection of these three aspects, most democratic regimes include in their constitutional framework a supreme court or constitutional court with jurisdiction to arbitrate the inevitable tensions that arise between democracy’s popular sovereignty and constitutionalism’s fundamental rights. 8 These courts are, ultimately, the institutions responsible for protecting fundamental rights and the rules of the democratic game against any abuse of power attempted by the majority. Recent experiences in Hungary, Poland, Turkey, Venezuela, and Nicaragua show that when courts fail to fulfill this role, democracy collapses or suffers major setbacks. 9

In recent years, several events have challenged the prevalence of democratic constitutionalism in many parts of the world, in a phenomenon characterized by many as democratic recession. 10 Even consolidated democracies have endured moments of turmoil and institutional discredit, 11 as the world witnessed the rise of an authoritarian, anti-pluralist, and anti-institutional populist wave posing serious threats to democracy.

Populism can be right-wing or left-wing, 12 but the recent wave has been characterized by the prevalence of right-wing extremism, often racist, xenophobic, misogynistic, and homophobic. 13 While in the past the far left was united through Communist International, today it is the far right that has a major global network. 14 The hallmark of right-wing populism is the division of society into “us” (the pure, decent, conservatives) and “them” (the corrupt, liberal, cosmopolitan elites). 15 Authoritarian populism flows from the unfulfilled promises of democracy for opportunities and prosperity for all. 16 Three aspects undergird this democratic frustration: political (people do not feel represented by the existing electoral systems, political leaders, and democratic institutions); social (stagnation, unemployment, and the rise of inequality); and cultural identity (a conservative reaction to the progressive identity agenda of human rights that prevailed in recent decades with the protection of the fundamental rights of women, African descendants, religious minorities, LGBTQ+ communities, indigenous populations, and the environment). 17

Extremist authoritarian populist regimes often adopt similar strategies to capitalize on the political, social, and cultural identity-based frustrations fueling democratic recessions. These tactics include by-pass or co-optation of the intermediary institutions that mediate the interface between the people and the government, such as the legislature, the press, and civil society. They also involve attacks on supreme courts and constitutional courts and attempts to capture them by appointing submissive judges. 18 The rise of social media potentializes these strategies by creating a free and instantaneous channel of direct communication between populists and their supporters. 19 This unmediated interaction facilitates the use of disinformation campaigns, hate speech, slander, lies, and conspiracy theories as political tools to advance antidemocratic goals. The instantaneous nature of these channels is ripe for impulsive reactions, which facilitate verbal attacks by supporters and polarization, feeding back into the populist discourse. These tactics threaten democracy and free and fair elections because they deceive voters and silence the opposition, distorting public debate. Ultimately, this form of communication undermines the values that justify the special protection of freedom of expression to begin with. The “truth decay” and “fact polarization” that result from these efforts discredit institutions and consequently foster distrust in democracy. 20

III. Internet, Social Media, and Freedom of Expression 21

The third industrial revolution, also known as the technological or digital revolution, has shaped our world today. 22 Some of its main features are the massification of personal computers, the universalization of smartphones and, most importantly, the internet. One of the main byproducts of the digital revolution and the internet was the emergence of social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok and messaging applications like WhatsApp and Telegram. We live in a world of apps, algorithms, artificial intelligence, and innovation occurring at breakneck speed where nothing seems truly new for very long. This is the background for the narrative that follows.

A. The Impact of the Internet

The internet revolutionized the world of interpersonal and social communication, exponentially expanded access to information and knowledge, and created a public sphere where anyone can express ideas, opinions, and disseminate facts. 23 Before the internet, one’s participation in public debate was dependent upon the professional press, 24 which investigated facts, abided by standards of journalistic ethics, 25 and was liable for damages if it knowingly or recklessly published untruthful information. 26 There was a baseline of editorial control and civil liability over the quality and veracity of what was published in this medium. This does not mean that it was a perfect world. The number of media outlets was, and continues to be, limited in quantity and perspectives; journalistic companies have their own interests, and not all of them distinguish fact from opinion with the necessary care. Still, there was some degree of control over what became public, and there were costs to the publication of overtly hateful or false speech.

The internet, with the emergence of websites, personal blogs, and social media, revolutionized this status quo. It created open, online communities for user-generated texts, images, videos, and links, published without editorial control and at no cost. This advanced participation in public discourse, diversified sources, and exponentially increased available information. 27 It gave a voice to minorities, civil society, politicians, public agents, and digital influencers, and it allowed demands for equality and democracy to acquire global dimensions. This represented a powerful contribution to political dynamism, resistance to authoritarianism, and stimulation of creativity, scientific knowledge, and commercial exchanges. 28 Increasingly, the most relevant political, social, and cultural communications take place on the internet’s unofficial channels.

However, the rise of social media also led to an increase in the dissemination of abusive and criminal speech. 29 While these platforms did not create mis- or disinformation, hate speech, or speech that attacks democracy, the ability to publish freely, with no editorial control and little to no accountability, increased the prevalence of these types of speech and facilitated its use as a political tool by populist leaders. 30 Additionally, and more fundamentally, platform business models compounded the problem through algorithms that moderate and distribute online content. 31

B. The Role of Algorithms

The ability to participate and be heard in online public discourse is currently defined by the content moderation algorithms of a couple major technology companies. Although digital platforms initially presented themselves as neutral media where users could publish freely, they in fact exercise legislative, executive, and judicial functions because they unilaterally define speech rules in their terms and conditions and their algorithms decide how content is distributed and how these rules are applied. 32

Specifically, digital platforms rely on algorithms for two different functions: recommending content and moderating content. 33 First, a fundamental aspect of the service they offer involves curating the content available to provide each user with a personalized experience and increase time spent online. They resort to deep learning algorithms that monitor every action on the platform, draw from user data, and predict what content will keep a specific user engaged and active based on their prior activity or that of similar users. 34 The transition from a world of information scarcity to a world of information abundance generated fierce competition for user attention—the most valuable resource in the Digital Age. 35 The power to modify a person’s information environment has a direct impact on their behavior and beliefs. Because AI systems can track an individual’s online history, they can tailor specific messages to maximize impact. More importantly, they monitor whether and how the user interacts with the tailored message, using this feedback to influence future content targeting and progressively becoming more effective in shaping behavior. 36 Given that humans engage more with content that is polarizing and provocative, these algorithms elicit powerful emotions, including anger. 37 The power to organize online content therefore directly impacts freedom of expression, pluralism, and democracy. 38

In addition to recommendation systems, platforms rely on algorithms for content moderation, the process of classifying content to determine whether it violates community standards. 39 As mentioned, the growth of social media and its use by people around the world allowed for the spread of lies and criminal acts with little cost and almost no accountability, threatening the stability of even long-standing democracies. Inevitably, digital platforms had to enforce terms and conditions defining the norms of their digital community and moderate speech accordingly. 40 But the potentially infinite amount of content published online means that this control cannot be exercised exclusively by humans.

Content moderation algorithms optimize the scanning of published content to identify violations of community standards or terms of service at scale and apply measures ranging from removal to reducing reach or including clarifications or references to alternative information. Platforms often rely on two algorithmic models for content moderation. The first is the reproduction detection model , which uses unique identifiers to catch reproductions of content previously labeled as undesired. 41 The second system, the predictive model , uses machine learning techniques to identify potential illegalities in new and unclassified content. 42 Machine learning is a subtype of artificial intelligence that extracts patterns in training datasets, capable of learning from data without explicit programming to do so. 43 Although helpful, both models have shortcomings.

The reproduction detection model is inefficient for content such as hate speech and disinformation, where the potential for new and different publications is virtually unlimited and users can deliberately make changes to avoid detection. 44 The predictive model is still limited in its ability to address situations to which it has not been exposed in training, primarily because it lacks the human ability to understand nuance and to factor in contextual considerations that influence the meaning of speech. 45 Additionally, machine learning algorithms rely on data collected from the real world and may embed prejudices or preconceptions, leading to asymmetrical applications of the filter. 46 And because the training data sets are so large, it can be hard to audit them for these biases. 47

Despite these limitations, algorithms will continue to be a crucial resource in content moderation given the scale of online activities. 48 In the last two months of 2020 alone, Facebook applied a content moderation measure to 105 million publications, and Instagram to 35 million. 49 YouTube has 500 hours of video uploaded per minute and removed more than 9.3 million videos. 50 In the first half of 2020, Twitter analyzed complaints related to 12.4 million accounts for potential violations of its rules and took action against 1.9 million. 51 This data supports the claim that human moderation is impossible, and that algorithms are a necessary tool to reduce the spread of illicit and harmful content. On the one hand, holding platforms accountable for occasional errors in these systems would create wrong incentives to abandon algorithms in content moderation with the negative consequence of significantly increasing the spread of undesired speech. 52 On the other hand, broad demands for platforms to implement algorithms to optimize content moderation, or laws that impose very short deadlines to respond to removal requests submitted by users, can create excessive pressure for the use of these imprecise systems on a larger scale. Acknowledging the limitations of this technology is fundamental for precise regulation.

C. Some Undesirable Consequences

One of the most striking impacts of this new informational environment is the exponential increase in the scale of social communications and the circulation of news. Around the world, few newspapers, print publications, and radio stations cross the threshold of having even one million subscribers and listeners. This suggests the majority of these publications have a much smaller audience, possibly in the thousands or tens of thousands of people. 53 Television reaches millions of viewers, although diluted among dozens or hundreds of channels. 54 Facebook, on the other hand, has about 3 billion active users. 55 YouTube has 2.5 billion accounts. 56 WhatsApp, more than 2 billion. 57 The numbers are bewildering. However, and as anticipated, just as the digital revolution democratized access to knowledge, information, and public space, it also introduced negative consequences for democracy that must be addressed. Three of them include:

a) the increased circulation of disinformation, deliberate lying, hate speech, conspiracy theories, attacks on democracy, and inauthentic behavior, made possible by recommendation algorithms that optimize for user engagement and content moderation algorithms that are still incapable of adequately identifying undesirable content;

b) the tribalization of life, with the formation of echo chambers where groups speak only to themselves, reinforcing confirmation bias, 58 making speech progressively more radical, and contributing to polarization and intolerance; and

c) a global crisis in the business model of the professional press. Although social media platforms have become one of the main sources of information, they do not produce their own content. They hire engineers, not reporters, and their interest is engagement, not news. 59 Because advertisers’ spending has migrated away from traditional news publications to technological platforms with broader reaches, the press has suffered from a lack of revenue which has forced hundreds of major publications, national and local, to close their doors or reduce their journalist workforce. 60 But a free and strong press is more than just a private business; it is a pillar for an open and free society. It serves a public interest in the dissemination of facts, news, opinions, and ideas, indispensable preconditions for the informed exercise of citizenship. Knowledge and truth—never absolute, but sincerely sought—are essential elements for the functioning of a constitutional democracy. Citizens need to share a minimum set of common objective facts from which to inform their own judgments. If they cannot accept the same facts, public debate becomes impossible. Intolerance and violence are byproducts of the inability to communicate—hence the importance of “knowledge institutions,” such as universities, research entities, and the institutional press. The value of free press for democracy is illustrated by the fact that in different parts of the world, the press is one of the only private businesses specifically referred to throughout constitutions. Despite its importance for society and democracy, surveys reveal a concerning decline in its prestige. 61

In the beginning of the digital revolution, there was a belief that the internet should be a free, open, and unregulated space in the interest of protecting access to the platform and promoting freedom of expression. Over time, concerns emerged, and a consensus gradually grew for the need for internet regulation. Multiple approaches for regulating the internet were proposed, including: (a) economic, through antitrust legislation, consumer protection, fair taxation, and copyright rules; (b) privacy, through laws restricting collection of user data without consent, especially for content targeting; and (c) targeting inauthentic behavior, content control, and platform liability rules. 62

Devising the proper balance between the indispensable preservation of freedom of expression on the one hand, and the repression of illegal content on social media on the other, is one of the most complex issues of our generation. Freedom of expression is a fundamental right incorporated into virtually all contemporary constitutions and, in many countries, is considered a preferential freedom. Several reasons have been advanced for granting freedom of expression special protection, including its roles: (a) in the search for the possible truth 63 in an open and plural society, 64 as explored above in discussing the importance of the institutional press; (b) as an essential element for democracy 65 because it allows the free circulation of ideas, information, and opinions that inform public opinion and voting; and (c) as an essential element of human dignity, 66 allowing the expression of an individual’s personality.

The regulation of digital platforms cannot undermine these values but must instead aim at its protection and strengthening. However, in the digital age, these same values that historically justified the reinforced protection of freedom of expression can now justify its regulation. As U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres thoughtfully stated, “the ability to cause large-scale disinformation and undermine scientifically established facts is an existential risk to humanity.” 67

Two aspects of the internet business model are particularly problematic for the protection of democracy and free expression. The first is that, although access to most technological platforms and applications is free, users pay for access with their privacy. 68 As Lawrence Lessig observed, we watch television, but the internet watches us. 69 Everything each individual does online is monitored and monetized. Data is the modern gold. 70 Thus, those who pay for the data can more efficiently disseminate their message through targeted ads. As previously mentioned, the power to modify a person’s information environment has a direct impact on behavior and beliefs, especially when messages are tailored to maximize impact on a specific individual. 71

The second aspect is that algorithms are programmed to maximize time spent online. This often leads to the amplification of provocative, radical, and aggressive content. This in turn compromises freedom of expression because, by targeting engagement, algorithms sacrifice the search for truth (with the wide circulation of fake news), democracy (with attacks on institutions and defense of coups and authoritarianism), and human dignity (with offenses, threats, racism, and others). The pursuit of attention and engagement for revenue is not always compatible with the values that underlie the protection of freedom of expression.

IV. A Framework for the Regulation of Social Media

Platform regulation models can be broadly classified into three categories: (a) state or government regulation, through legislation and rules drawing a compulsory, encompassing framework; (b) self-regulation, through rules drafted by platforms themselves and materialized in their terms of use; and (c) regulated self-regulation or coregulation, through standards fixed by the state but which grant platform flexibility in materializing and implementing them. This Essay argues for the third model, with a combination of governmental and private responsibilities. Compliance should be overseen by an independent committee, with the minority of its representatives coming from the government, and the majority coming from the business sector, academia, technology entities, users, and civil society.

The regulatory framework should aim to reduce the asymmetry of information between platforms and users, safeguard the fundamental right to freedom of expression from undue private or state interventions, and protect and strengthen democracy. The current technical limitations of content moderation algorithms explored above and normal substantive disagreement about what content should be considered illegal or harmful suggest that an ideal regulatory model should optimize the balance between the fundamental rights of users and platforms, recognizing that there will always be cases where consensus is unachievable. The focus of regulation should be the development of adequate procedures for content moderation, capable of minimizing errors and legitimizing decisions even when one disagrees with the substantive result. 72 With these premises as background, the proposal for regulation formulated here is divided into three levels: (a) the appropriate intermediary liability model for user-generated content; (b) procedural duties for content moderation; and (c) minimum duties to moderate content that represents concrete threats to democracy and/or freedom of expression itself.

A. Intermediary Liability for User-Generated Content

There are three main regimes for platform liability for third-party content. In strict liability models, platforms are held responsible for all user-generated posts. 73 Since platforms have limited editorial control over what is posted and limited human oversight over the millions of posts made daily, this would be a potentially destructive regime. In knowledge-based liability models, platform liability arises if they do not act to remove content after an extrajudicial request from users—this is also known as a “notice-and-takedown” system. 74 Finally, a third model would make platforms liable for user-generated content only in cases of noncompliance with a court order mandating content removal. This latter model was adopted in Brazil with the Civil Framework for the Internet (Marco Civil da Internet). 75 The only exception in Brazilian legislation to this general rule is revenge porn: if there is a violation of intimacy resulting from the nonconsensual disclosure of images, videos, or other materials containing private nudity or private sexual acts, extrajudicial notification is sufficient to create an obligation for content removal under penalty of liability. 76

In our view, the Brazilian model is the one that most adequately balances the fundamental rights involved. As mentioned, in the most complex cases concerning freedom of expression, people will disagree on the legality of speech. Rules holding platforms accountable for not removing content after mere user notification create incentives for over-removal of any potentially controversial content, excessively restricting users’ freedom of expression. If the state threatens to hold digital platforms accountable if it disagrees with their assessment, companies will have the incentive to remove all content that could potentially be considered illicit by courts to avoid liability. 77

Nonetheless, this liability regime should coexist with a broader regulatory structure imposing principles, limits, and duties on content moderation by digital platforms, both to increase the legitimacy of platforms’ application of their own terms and conditions and to minimize the potentially devastating impacts of illicit or harmful speech.

B. Standards for Proactive Content Moderation

Platforms have free enterprise and freedom of expression rights to set their own rules and decide the kind of environment they want to create, as well as to moderate harmful content that could drive users away. However, because these content moderation algorithms are the new governors of the public sphere, 78 and because they define the ability to participate and be heard in online public discourse, platforms should abide by minimum procedural duties of transparency and auditing, due process, and fairness.

1. Transparency and Auditing

Transparency and auditing measures serve mainly to ensure that platforms are accountable for content moderation decisions and for the impacts of their algorithms. They provide users with greater understanding and knowledge about the extent to which platforms regulate speech, and they provide oversight bodies and researchers with information to understand the threats of digital services and the role of platforms in amplifying or minimizing them.

Driven by demands from civil society, several digital platforms already publish transparency reports. 79 However, the lack of binding standards means that these reports have significant gaps, no independent verification of the information provided, 80 and no standardization across platforms, preventing comparative analysis. 81 In this context, regulatory initiatives that impose minimum requirements and standards are crucial to make oversight more effective. On the other hand, overly broad transparency mandates may force platforms to adopt simpler content moderation rules to reduce costs, which could negatively impact the accuracy of content moderation or the quality of the user experience. 82 A tiered approach to transparency, where certain information is public and certain information is limited to oversight bodies or previously qualified researchers, ensures adequate protection of countervailing interests, such as user privacy and business confidentiality. 83 The Digital Services Act, 84 recently passed in the European Union, contains robust transparency provisions that generally align with these considerations. 85

The information that should be publicly provided includes clear and unambiguous terms of use, the options available to address violations (such as removal, amplification reduction, clarifications, and account suspension) and the division of labor between algorithms and humans. More importantly, public transparency reports should include information on the accuracy of automated moderation measures and the number of content moderation actions broken down by type (such as removal, blocking, and account deletion). 86 There must also be transparency obligations to researchers, giving them access to crucial information and statistics, including to the content analyzed for the content moderation decisions. 87

Although valuable, transparency requirements are insufficient in promoting accountability because they rely on users and researchers to actively monitor platform conduct and presuppose that they have the power to draw attention to flaws and promote changes. 88 Legally mandated third-party algorithmic auditing is therefore an important complement to ensure that these models satisfy legal, ethical, and safety standards and to elucidate the embedded value tradeoffs, such as between user safety and freedom of expression. 89 As a starting point, algorithm audits should consider matters such as how accurately they perform, any potential bias or discrimination incorporated in the data, and to what extent the internal mechanics are explainable to humans. 90 The Digital Services Act contains a similar proposal. 91

The market for algorithmic auditing is still emergent and replete with uncertainty. In attempting to navigate this scenario, regulators should: (a) define how often the audits should happen; (b) develop standards and best practices for auditing procedures; (c) mandate specific disclosure obligations so auditors have access to the required data; and (d) define how identified harms should be addressed. 92

2. Due Process and Fairness

To ensure due process, platforms must inform users affected by content moderation decisions of the allegedly violated provision of the terms of use, as well as offer an internal system of appeals against these decisions. Platforms must also create systems that allow for the substantiated denunciation of content or accounts by other users, and notify reporting users of the decision taken.

As for fairness, platforms should ensure that the rules are applied equally to all users. Although it is reasonable to suppose that platforms may adopt different criteria for public persons or information of public interest, these exceptions must be clear in the terms of use. This issue has recently been the subject of controversy between the Facebook Oversight Board and the company. 93

Due to the enormous amount of content published on the platforms and the inevitability of using automated mechanisms for content moderation, platforms should not be held accountable for a violation of these duties in specific cases, but only when the analysis reveals a systemic failure to comply. 94

C. Minimum Duties to Moderate Illicit Content

The regulatory framework should also contain specific obligations to address certain types of especially harmful speech. The following categories are considered by the authors to fall within this group: disinformation, hate speech, anti-democratic attacks, cyberbullying, terrorism, and child pornography. Admittedly, defining and consensually identifying the speech included in these categories—except in the case of child pornography 95 —is a complex and largely subjective task. Precisely for this reason, platforms should be free to define how the concepts will be operationalized, as long as they guide definitions by international human rights parameters and in a transparent manner. This does not mean that all platforms will reach the same definitions nor the same substantive results in concrete cases, but this should not be considered a flaw in the system, since the plurality of rules promotes freedom of expression. The obligation to observe international human rights parameters reduces the discretion of companies, while allowing for the diversity of policies among them. After defining these categories, platforms must establish mechanisms that allow users to report violations.

In addition, platforms should develop mechanisms to address coordinated inauthentic behaviors, which involve the use of automated systems or deceitful means to artificially amplify false or dangerous messages by using bots, fake profiles, trolls, and provocateurs. 96 For example, if a person publishes a post for his twenty followers saying that kerosene oil is good for curing COVID-19, the negative impact of this misinformation is limited. However, if that message is amplified to thousands of users, a greater public health issue arises. Or, in another example, if the false message that an election was rigged reaches millions of people, there is a democratic risk due to the loss of institutional credibility.

The role of oversight bodies should be to verify that platforms have adopted terms of use that prohibit the sharing of these categories of speech and ensure that, systemically, the recommendation and content moderation systems are trained to moderate this content.

V. Conclusion

The World Wide Web has provided billions of people with access to knowledge, information, and the public space, changing the course of history. However, the misuse of the internet and social media poses serious threats to democracy and fundamental rights. Some degree of regulation has become necessary to confront inauthentic behavior and illegitimate content. It is essential, however, to act with transparency, proportionality, and adequate procedures, so that pluralism, diversity, and freedom of expression are preserved.

In addition to the importance of regulatory action, the responsibility for the preservation of the internet as a healthy public sphere also lies with citizens. Media education and user awareness are fundamental steps for the creation of a free but positive and constructive environment on the internet. Citizens should be conscious that social media can be unfair, perverse, and can violate fundamental rights and basic rules of democracy. They must be attentive not to uncritically pass on all information received. Alongside states, regulators, and tech companies, citizens are also an important force to address these threats. In Jonathan Haidt’s words, “[w]hen our public square is governed by mob dynamics unrestrained by due process, we don’t get justice and inclusion; we get a society that ignores context, proportionality, mercy, and truth.” 97

- 1 Tim Wu, Is the First Amendment Obsolete? , in The Perilous Public Square 15 (David E. Pozen ed., 2020).

- 2 Jack M. Balkin, Free Speech is a Triangle , 118 Colum. L. Rev. 2011, 2019 (2018).

- 3 Luís Roberto Barroso, O Constitucionalismo Democrático ou Neoconstitucionalismo como ideologia vitoriosa do século XX , 4 Revista Publicum 14, 14 (2018).

- 4 Id. at 16.

- 7 Ronald Dworkin, Is Democracy Possible Here?: Principles for a New Political Debate xii (2006); Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously 181 (1977).

- 8 Barroso, supra note 3, at 16.

- 9 Samuel Issacharoff, Fragile Democracies: Contested Power in the Era of Constitutional Courts i (2015).

- 10 Larry Diamond, Facing up to the Democratic Recession , 26 J. Democracy 141 (2015). Other scholars have referred to the same phenomenon using other terms, such as democratic retrogression, abusive constitutionalism, competitive authoritarianism, illiberal democracy, and autocratic legalism. See, e.g. , Aziz Huq & Tom Ginsburg, How to Lose a Constitutional Democracy , 65 UCLA L. Rev. 91 (2018); David Landau, Abusive Constitutionalism , 47 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 189 (2013); Kim Lane Scheppele, Autocratic Legalism , 85 U. Chi. L. Rev. 545 (2018).

- 11 Dan Balz, A Year After Jan. 6, Are the Guardrails that Protect Democracy Real or Illusory? , Wash. Post (Jan. 6, 2022), https://perma.cc/633Z-A9AJ; Brexit: Reaction from Around the UK , BBC News (June 24, 2016), https://perma.cc/JHM3-WD7A.

- 12 Cas Mudde, The Populist Zeitgeist , 39 Gov’t & Opposition 541, 549 (2004).

- 13 See generally Mohammed Sinan Siyech, An Introduction to Right-Wing Extremism in India , 33 New Eng. J. Pub. Pol’y 1 (2021) (discussing right-wing extremism in India). See also Eviane Leidig, Hindutva as a Variant of Right-Wing Extremism , 54 Patterns of Prejudice 215 (2020) (tracing the history of “Hindutva”—defined as “an ideology that encompasses a wide range of forms, from violent, paramilitary fringe groups, to organizations that advocate the restoration of Hindu ‘culture’, to mainstream political parties”—and finding that it has become mainstream since 2014 under Modi); Ariel Goldstein, Brazil Leads the Third Wave of the Latin American Far Right , Ctr. for Rsch. on Extremism (Mar. 1, 2021), https://perma.cc/4PCT-NLQJ (discussing right-wing extremism in Brazil under Bolsonaro); Seth G. Jones, The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States , Ctr. for Strategic & Int’l Stud. (Nov. 2018), https://perma.cc/983S-JUA7 (discussing right-wing extremism in the U.S. under Trump).

- 14 Sergio Fausto, O Desafio Democrático [The Democratic Challenge], Piauí (Aug. 2022), https://perma.cc/474A-3849.

- 15 Jan-Werner Muller, Populism and Constitutionalism , in The Oxford Handbook of Populism 590 (Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser et al. eds., 2017).

- 16 Ming-Sung Kuo, Against Instantaneous Democracy , 17 Int’l J. Const. L. 554, 558–59 (2019); see also Digital Populism , Eur. Ctr. for Populism Stud., https://perma.cc/D7EV-48MV.

- 17 Luís Roberto Barroso, Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: The Limits of Law in a Changing World , 18 Int’l J. Const. L. 334, 349 (2020).

- 18 For the use of social media, see Sven Engesser et al., Populism and Social Media: How Politicians Spread a Fragmented Ideology , 20 Info. Commc’n & Soc’y 1109 (2017). For attacks on the press, see WPFD 2021: Attacks on Press Freedom Growing Bolder Amid Rising Authoritarianism , Int’l Press Inst. (Apr. 30, 2021), https://perma.cc/SGN9-55A8. For attacks on the judiciary, see Michael Dichio & Igor Logvinenko, Authoritarian Populism, Courts and Democratic Erosion , Just Sec. (Feb. 11, 2021), https://perma.cc/WZ6J-YG49.

- 19 Kuo, supra note 16, at 558–59; see also Digital Populism , supra note 16.

- 20 Vicki C. Jackson, Knowledge Institutions in Constitutional Democracy: Reflections on “the Press” , 15 J. Media L. 275 (2022).

- 21 Many of the ideas and information on this topic were collected in Luna van Brussel Barroso, Liberdade de Expressão e Democracia na Era Digital: O impacto das mídias sociais no mundo contemporâneo [Freedom of Expression and Democracy in the Digital Era: The Impact of Social Media in the Contemporary World] (2022), which was recently published in Brazil.

- 22 The first industrial revolution is marked by the use of steam as a source of energy in the middle of the 18th century. The second started with the use of electricity and the invention of the internal combustion engine at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. There are already talks of the fourth industrial revolution as a product of the fusion of technologies that blurs the boundaries among the physical, digital, and biological spheres. See generally Klaus Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution (2017).

- 23 Gregory P. Magarian, The Internet and Social Media , in The Oxford Handbook of Freedom of Speech 350, 351–52 (Adrienne Stone & Frederick Schauer eds., 2021).

- 24 Wu, supra note 1, at 15.

- 25 Journalistic ethics include distinguishing fact from opinion, verifying the veracity of what is published, having no self-interest in the matter being reported, listening to the other side, and rectifying mistakes. For an example of an international journalistic ethics charter, see Global Charter of Ethics for Journalists , Int’l Fed’n of Journalists (June 12, 2019), https://perma.cc/7A2C-JD2S.

- 26 See, e.g. , New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

- 27 Balkin, supra note 2, at 2018.

- 28 Magarian, supra note 23, at 351–52.

- 29 Wu, supra note 1, at 15.

- 30 Magarian, supra note 23, at 357–60.

- 31 Niva Elkin-Koren & Maayan Perel, Speech Contestation by Design: Democratizing Speech Governance by AI , 50 Fla. State U. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2023).

- 32 Thomas E. Kadri & Kate Klonick, Facebook v. Sullivan: Public Figures and Newsworthiness in Online Speech , 93 S. Cal. L. Rev. 37, 94 (2019).

- 33 Elkin-Koren & Perel, supra note 31.

- 34 Chris Meserole, How Do Recommender Systems Work on Digital Platforms? , Brookings Inst.(Sept. 21, 2022), https://perma.cc/H53K-SENM.

- 35 Kris Shaffer, Data versus Democracy: How Big Data Algorithms Shape Opinions and Alter the Course of History xi–xv (2019).

- 36 See generally Stuart Russell, Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control (2019).

- 37 Shaffer, supra note 35, at xi–xv.

- 38 More recently, with the advance of neuroscience, platforms have sharpened their ability to manipulate and change our emotions, feelings and, consequently, our behavior in accordance not with our own interests, but with theirs (or of those who they sell this service to). Kaveh Waddell, Advertisers Want to Mine Your Brain , Axios (June 4, 2019), https://perma.cc/EU85-85WX. In this context, there is already talk of a new fundamental right to cognitive liberty, mental self-determination, or the right to free will. Id .

- 39 Content moderation refers to “systems that classify user generated content based on either matching or prediction, leading to a decision and governance outcome (e.g. removal, geoblocking, account takedown).” Robert Gorwa, Reuben Binns & Christian Katzenbach, Algorithmic Content Moderation: Technical and Political Challenges in the Automation of Platform Governance , 7 Big Data & Soc’y 1, 3 (2020).

- 40 Jack M. Balkin, Free Speech in the Algorithmic Society: Big Data, Private Governance, and New School Speech Regulation , 51 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1149, 1183 (2018).

- 41 See Carey Shenkman, Dhanaraj Thakur & Emma Llansó, Do You See What I See? Capabilities and Limits of Automated Multimedia Content Analysis 13–16 (May 2021),https://perma.cc/J9MP-7PQ8.

- 42 See id. at 17–21.

- 43 See Michael Wooldridge, A Brief History of Artificial Intelligence: What It Is, Where We Are, and Where We Are Going 63 (2021).

Perceptual hashing has been the primary technology utilized to mitigate the spread of CSAM, since the same materials are often repeatedly shared, and databases of offending content are maintained by institutions like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) and its international analogue, the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC).

- 45 Natural language understanding is undermined by language ambiguity, contextual dependence of words of non-immediate proximity, references, metaphors, and general semantics rules. See Erik J. Larson, The Myth of Artificial Intelligence: Why Computers Can’t Think the Way We Do 52–55 (2021). Language comprehension in fact requires unlimited common-sense knowledge about the actual world, which humans possess and is impossible to code. Id . A case decided by Facebook’s Oversight Board illustrates the point: the company’s predictive filter for combatting pornography removed images from a breast cancer awareness campaign, a clearly legitimate content not meant to be targeted by the algorithm. See Breast Cancer Symptoms and Nudity , Oversight Bd. (2020), https://perma.cc/U9A5-TTTJ. However, based on prior training, the algorithm removed the publication because it detected pornography and was unable to factor the contextual consideration that this was a legitimate health campaign. Id .

- 46 See generally Adriano Koshiyama, Emre Kazim & Philip Treleaven, Algorithm Auditing: Managing the Legal, Ethical, and Technological Risks of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Associated Algorithms , 55 Computer 40 (2022).

- 47 Elkin-Koren & Perel, supra note 31.

- 48 Evelyn Douek, Governing Online Speech: From “Posts-as-Trumps” to Proportionality and Probability , 121 Colum. L. Rev. 759, 791 (2021).

- 53 See Martha Minow, Saving the Press: Why the Constitution Calls for Government Action to Preserve Freedom of Speech 20 (2021). For example, the best-selling newspaper in the world, The New York Times , ended the year 2022 with around 10 million subscribers across digital and print. Katie Robertson, The New York Times Company Adds 180,000 Digital Subscribers , N.Y. Times (Nov. 2, 2022), https://perma.cc/93PF-TKC5. The Economist magazine had approximately 1.2 million subscribers in 2022. The Economist Group, Annual Report 2022 24 (2022), https://perma.cc/9HQQ-F7W2. Around the world, publications that reach one million subscribers are rare. These Are the Most Popular Paid Subscription News Websites , World Econ. F. (Apr. 29, 2021), https://perma.cc/L2MK-VPNX.

- 54 Lawrence Lessig, They Don’t Represent Us: Reclaiming Our Democracy 105 (2019).

- 55 Essential Facebook Statistics and Trends for 2023 , Datareportal (Feb. 19, 2023), https://perma.cc/UH33-JHUQ.

- 56 YouTube User Statistics 2023 , Glob. Media Insight (Feb. 27, 2023), https://perma.cc/3H4Y-H83V.

- 57 Brian Dean, WhatsApp 2022 User Statistics: How Many People Use WhatsApp , Backlinko (Jan. 5, 2022), https://perma.cc/S8JX-S7HN.

- 58 Confirmation bias, the tendency to seek out and favor information that reinforces one’s existing beliefs, presents an obstacle to critical thinking. Sachin Modgil et al., A Confirmation Bias View on Social Media Induced Polarisation During COVID-19 , Info. Sys. Frontiers (Nov. 20, 2021).

- 59 Minow, supra note 53, at 2.

- 60 Id. at 3, 11.

- 61 On the importance of the role of the press as an institution of public interest and its “crucial relationship” with democracy, see id. at 35. On the press as a “knowledge institution,” the idea of “institutional press,” and data on the loss of prestige by newspapers and television stations, see Jackson, supra note 20, at 4–5.

- 62 See , e.g. , Jack M. Balkin, How to Regulate (and Not Regulate) Social Media , 1 J. Free Speech L. 71, 89–96 (2021).

- 63 By possible truth we mean that not all claims, opinions and beliefs can be ascertained as true or false. Objective truths are factual and can thus be proven even when controversial—for example, climate change and the effectiveness of vaccines. Subjective truths, on the other hand, derive from individual normative, religious, philosophical, and political views. In a pluralistic world, any conception of freedom of expression must protect individual subjective beliefs.

- 64 Eugene Volokh, In Defense of the Marketplace of Ideas/Search for Truth as a Theory of Free Speech Protection , 97 Va. L. Rev. 595, 595 (May 2011).

- 66 Steven J. Heyman, Free Speech and Human Dignity 2 (2008).

- 67 A Global Dialogue to Guide Regulation Worldwide , UNESCO (Feb. 23, 2023), https://perma.cc/ALK8-HTG3.

- 68 Can We Fix What’s Wrong with Social Media? , Yale L. Sch. News (Aug. 3, 2022), https://perma.cc/MN58-2EVK.

- 69 Lessig, supra note 54, at 105.

- 71 See supra Part III.B.

- 72 Doeuk, supra note 48, at 804–13; see also John Bowers & Jonathan Zittrain, Answering Impossible Questions: Content Governance in an Age of Disinformation , Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinformation Rev. (Jan. 14, 2020), https://perma.cc/R7WW-8MQX.

- 73 Daphne Keller, Systemic Duties of Care and Intermediary Liability , Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y Blog (May 28, 2020), https://perma.cc/25GU-URGT.

- 75 Decreto No. 12.965, de 23 de abril de 2014, Diário Oficial da União [D.O.U.] de 4.14.2014 (Braz.) art. 19. In order to ensure freedom of expression and prevent censorship, providers of internet applications can only be civilly liable for damages resulting from content generated by third parties if, after specific court order, they do not make arrangements to, in the scope and technical limits of their service and within the indicated time, make unavailable the content identified as infringing, otherwise subject to the applicable legal provisions. Id .

- 76 Id. art. 21. The internet application provider that provides content generated by third parties will be held liable for the violation of intimacy resulting from the disclosure, without authorization of its participants, of images, videos, or other materials containing nude scenes or private sexual acts when, upon receipt of notification by the participant or its legal representative, fail to diligently promote, within the scope and technical limits of its service, the unavailability of this content. Id .

- 77 Balkin, supra note 2, at 2017.

- 78 Kate Klonick, The New Governors: The People, Rules, and Processes Governing Online Speech , 131 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1603 (2018).

- 79 Transparency Reporting Index, Access Now (July 2021), https://perma.cc/2TSL-2KLD (cataloguing transparency reporting from companies around the world).

- 80 Hum. Rts. Comm., Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, ¶¶ 63–66, U.N. Doc A/HRC/32/35 (2016).

- 81 Paddy Leerssen, The Soap Box as a Black Box: Regulating Transparency in Social Media Recommender Systems , 11 Eur. J. L. & Tech. (2020).

- 82 Daphne Keller, Some Humility About Transparency , Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y Blog (Mar. 19, 2021), https://perma.cc/4Y85-BATA.

- 83 Mark MacCarthy, Transparency Requirements for Digital Social Media Platforms: Recommendations for Policy Makers and Industry , Transatlantic Working Grp. (Feb. 12, 2020).

- 84 2022 O.J. (L 277) 1 [hereinafter DSA].

- 85 The DSA was approved by the European Parliament on July 5, 2022, and on October 4, 2022, the European Council gave its final acquiescence to the regulation. Digital Services: Landmark Rules Adopted for a Safer, Open Online Environment , Eur. Parliament (July 5, 2022), https://perma.cc/BZP5-V2B2. The DSA increases transparency and accountability of platforms, by providing, for example, for the obligation of “clear information on content moderation or the use of algorithms for recommending content (so-called recommender systems); users will be able to challenge content moderation decisions.” Id .

- 86 MacCarthy, supra note 83, 19–24.

- 87 To this end, American legislators recently introduced a U.S. Congressional bill that proposes a model for conducting research on the impacts of digital communications in a way that protects user privacy. See Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, S. 5339, 117th Congress (2022). The project mandates that digital platforms share data with researchers previously authorized by the Federal Trade Commission and publicly disclose certain data about content, algorithms, and advertising. Id .

- 88 Yifat Nahmias & Maayan Perel, The Oversight of Content Moderation by AI: Impact Assessment and Their Limitations , 58 Harv. J. on Legis. 145, 154–57 (2021).

- 89 Auditing Algorithms: The Existing Landscape, Role of Regulator and Future Outlook , Digit. Regul. Coop. F. (Sept. 23, 2022), https://perma.cc/7N6W-JNCW.

- 90 See generally Koshiyama et al., supra note 46.

- 91 In Article 37, the DSA provides that digital platforms of a certain size should be accountable, through annual independent auditing, for compliance with the obligations set forth in the Regulation and with any commitment undertaken pursuant to codes of conduct and crisis protocols.

- 92 Digit. Regul. Coop. F., supra note 89.

- 93 In a transparency report published at the end of its first year of operation, the Oversight Board highlighted the inadequacy of the explanations presented by Meta on the operation of a system known as cross-check, which apparently gave some users greater freedom on the platform. In January 2022, Meta explained that the cross-check system grants an additional degree of review to certain content that internal systems mark as violating the platform’s terms of use. Meta submitted a query to the Board on how to improve the functioning of this system and the Board made relevant recommendations. See Oversight Board Published Policy Advisory Opinion on Meta’s Cross-Check Program , Oversight Bd. (Dec. 2022), https://perma.cc/87Z5-L759.

- 94 Evelyn Douek, Content Moderation as Systems Thinking , 136 Harv. L. Rev. 526, 602–03 (2022).

- 95 The illicit nature of child pornography is objectively apprehended and does not implicate the same subjective considerations that the other referenced categories entail. Not surprisingly, several databases have been created to facilitate the moderation of this content. See Ofcom, Overview of Perceptual Hashing Technology 14 (Nov. 22, 2022), https://perma.cc/EJ45-B76X (“Several hash databases to support the detection of known CSAM exist, e.g. the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) hash database, the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) hash list and the International Child Sexual Exploitation (ICSE) hash database.”).

- 97 Jonathan Haidt, Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid , Atlantic (Apr. 11, 2022), https://perma.cc/2NXD-32VM.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges and Departments

- Email and phone search

- Give to Cambridge

- Museums and collections

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Postgraduate events

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

Internet censorship: making the hidden visible

- Research home

- About research overview

- Animal research overview

- Overseeing animal research overview

- The Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body

- Animal welfare and ethics

- Report on the allegations and matters raised in the BUAV report

- What types of animal do we use? overview

- Guinea pigs

- Equine species

- Naked mole-rats

- Non-human primates (marmosets)

- Other birds

- Non-technical summaries

- Animal Welfare Policy

- Alternatives to animal use

- Further information

- Research integrity

- Horizons magazine

- Strategic Initiatives & Networks

- Nobel Prize

- Interdisciplinary Research Centres

- Open access

- Energy sector partnerships

- Podcasts overview

- S2 ep1: What is the future?

- S2 ep2: What did the future look like in the past?

- S2 ep3: What is the future of wellbeing?

- S2 ep4 What would a more just future look like?

Despite being founded on ideals of freedom and openness, censorship on the internet is rampant, with more than 60 countries engaging in some form of state-sponsored censorship. A research project at the University of Cambridge is aiming to uncover the scale of this censorship, and to understand how it affects users and publishers of information

Censorship over the internet can potentially achieve unprecedented scale Sheharbano Khattak

For all the controversy it caused, Fitna is not a great film. The 17-minute short, by the Dutch far-right politician Geert Wilders, was a way for him to express his opinion that Islam is an inherently violent religion. Understandably, the rest of the world did not see things the same way. In advance of its release in 2008, the film received widespread condemnation, especially within the Muslim community.

When a trailer for Fitna was released on YouTube, authorities in Pakistan demanded that it be removed from the site. YouTube offered to block the video in Pakistan, but would not agree to remove it entirely. When YouTube relayed this decision back to the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA), the decision was made to block YouTube.

Although Pakistan has been intermittently blocking content since 2006, a more persistent blocking policy was implemented in 2011, when porn content was censored in response to a media report that highlighted Pakistan as the top country in terms of searches for porn. Then, in 2012, YouTube was blocked for three years when a video, deemed blasphemous, appeared on the website. Only in January this year was the ban lifted, when Google, which owns YouTube, launched a Pakistan-specific version, and introduced a process by which governments can request the blocking of access to offending material.

All of this raises the thorny issue of censorship. Those censoring might raise objections to material on the basis of offensiveness or incitement to violence (more than a dozen people died in Pakistan following widespread protests over the video uploaded to YouTube in 2012). But when users aren’t able to access a particular site, they often don’t know whether it’s because the site is down, or if some force is preventing them from accessing it. How can users know what is being censored and why?

“The goal of a censor is to disrupt the flow of information,” says Sheharbano Khattak, a PhD student in Cambridge’s Computer Laboratory, who studies internet censorship and its effects. “internet censorship threatens free and open access to information. There’s no code of conduct when it comes to censorship: those doing the censoring – usually governments – aren’t in the habit of revealing what they’re blocking access to.” The goal of her research is to make the hidden visible.

She explains that we haven’t got a clear understanding of the consequences of censorship: how it affects different stakeholders, the steps those stakeholders take in response to censorship, how effective an act of censorship is, and what kind of collateral damage it causes.

Because censorship operates in an inherently adversarial environment, gathering relevant datasets is difficult. Much of the key information, such as what was censored and how, is missing. In her research, Khattak has developed methodologies that enable her to monitor censorship by characterising what normal data looks like and flagging anomalies within the data that are indicative of censorship.

She designs experiments to measure various aspects of censorship, to detect censorship in actively and passively collected data, and to measure how censorship affects various players.

The primary reasons for government-mandated censorship are political, religious or cultural. A censor might take a range of steps to stop the publication of information, to prevent access to that information by disrupting the link between the user and the publisher, or to directly prevent users from accessing that information. But the key point is to stop that information from being disseminated.

Internet censorship takes two main forms: user-side and publisher-side. In user-side censorship, the censor disrupts the link between the user and the publisher. The interruption can be made at various points in the process between a user typing an address into their browser and being served a site on their screen. Users may see a variety of different error messages, depending on what the censor wants them to know.

“The thing is, even in countries like Saudi Arabia, where the government tells people that certain content is censored, how can we be sure of everything they’re stopping their citizens from being able to access?” asks Khattak. “When a government has the power to block access to large parts of the internet, how can we be sure that they’re not blocking more than they’re letting on?”

What Khattak does is characterise the demand for blocked content and try to work out where it goes. In the case of the blocking of YouTube in 2012 in Pakistan, a lot of the demand went to rival video sites like Daily Motion. But in the case of pornographic material, which is also heavily censored in Pakistan, the government censors didn’t have a comprehensive list of sites that were blacklisted, so plenty of pornographic content slipped through the censors’ nets.

Despite any government’s best efforts, there will always be individuals and publishers who can get around censors, and access or publish blocked content through the use of censorship resistance systems. A desirable property, of any censorship resistance system is to ensure that users are not traceable, but usually users have to combine them with anonymity services such as Tor.

“It’s like an arms race, because the technology which is used to retrieve and disseminate information is constantly evolving,” says Khattak. “We now have social media sites which have loads of user-generated content, so it’s very difficult for a censor to retain control of this information because there’s so much of it. And because this content is hosted by sites like Google or Twitter that integrate a plethora of services, wholesale blocking of these websites is not an option most censors might be willing to consider.”

In addition to traditional censorship, Khattak also highlights a new kind of censorship – publisher-side censorship – where websites refuse to offer services to a certain class of users. Specifically, she looks at the differential treatments of Tor users by some parts of the web. The issue with services like Tor is that visitors to a website are anonymised, so the owner of the website doesn’t know where their visitors are coming from. There is increasing use of publisher-side censorship from site owners who want to block users of Tor or other anonymising systems.

“Censorship is not a new thing,” says Khattak. “Those in power have used censorship to suppress speech or writings deemed objectionable for as long as human discourse has existed. However, censorship over the internet can potentially achieve unprecedented scale, while possibly remaining discrete so that users are not even aware that they are being subjected to censored information.”

Professor Jon Crowcroft, who Khattak works with, agrees: “It’s often said that, online, we live in an echo chamber, where we hear only things we agree with. This is a side of the filter bubble that has its flaws, but is our own choosing. The darker side is when someone else gets to determine what we see, despite our interests. This is why internet censorship is so concerning.”

“While the cat and mouse game between the censors and their opponents will probably always exist,” says Khattak. “I hope that studies such as mine will illuminate and bring more transparency to this opaque and complex subject, and inform policy around the legality and ethics of such practices.”

Read this next

Call for safeguards to prevent unwanted ‘hauntings’ by AI chatbots of dead loved ones

Emissions and evasions

Lights could be the future of the internet and data transmission

The Misinformation Susceptibility Test

Barbed wire

Credit: Hernán Piñera

Search research

Sign up to receive our weekly research email.

Our selection of the week's biggest Cambridge research news sent directly to your inbox. Enter your email address, confirm you're happy to receive our emails and then select 'Subscribe'.

I wish to receive a weekly Cambridge research news summary by email.

The University of Cambridge will use your email address to send you our weekly research news email. We are committed to protecting your personal information and being transparent about what information we hold. Please read our email privacy notice for details.

- digital technology

- social media

- Digital society

- Sheharbano Khattak

- Jon Crowcroft

- Computer Laboratory

- School of Technology

Connect with us

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility statement

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Most Americans Think Social Media Sites Censor Political Viewpoints

Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to say major tech companies favor the views of liberals over conservatives. At the same time, partisans differ on whether social media companies should flag inaccurate information on their platforms.

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

Note: Some of the findings reported here have been updated. For the latest data on social media censorship, read our 2022 blog post .

How we did this

Pew Research Center has been studying the role of technology and technology companies in Americans’ lives for many years. This study was conducted to understand Americans’ views about the role of major technology companies in the political landscape. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,708 U.S. adults from June 16 to 22, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

Americans have complicated feelings about their relationship with big technology companies. While they have appreciated the impact of technology over recent decades and rely on these companies’ products to communicate, shop and get news , many have also grown critical of the industry and have expressed concerns about the executives who run them.

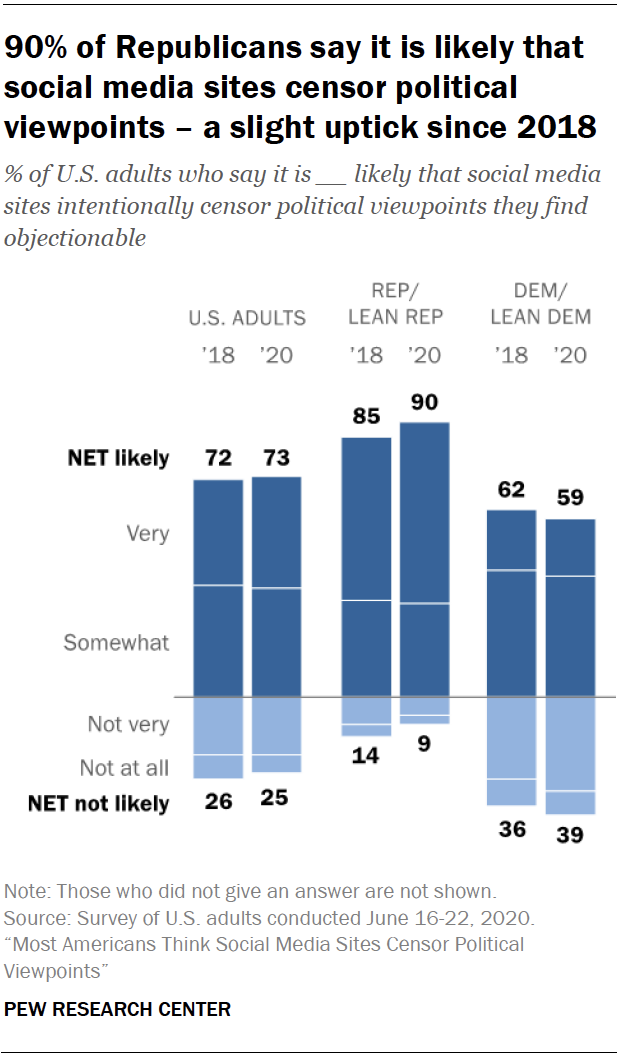

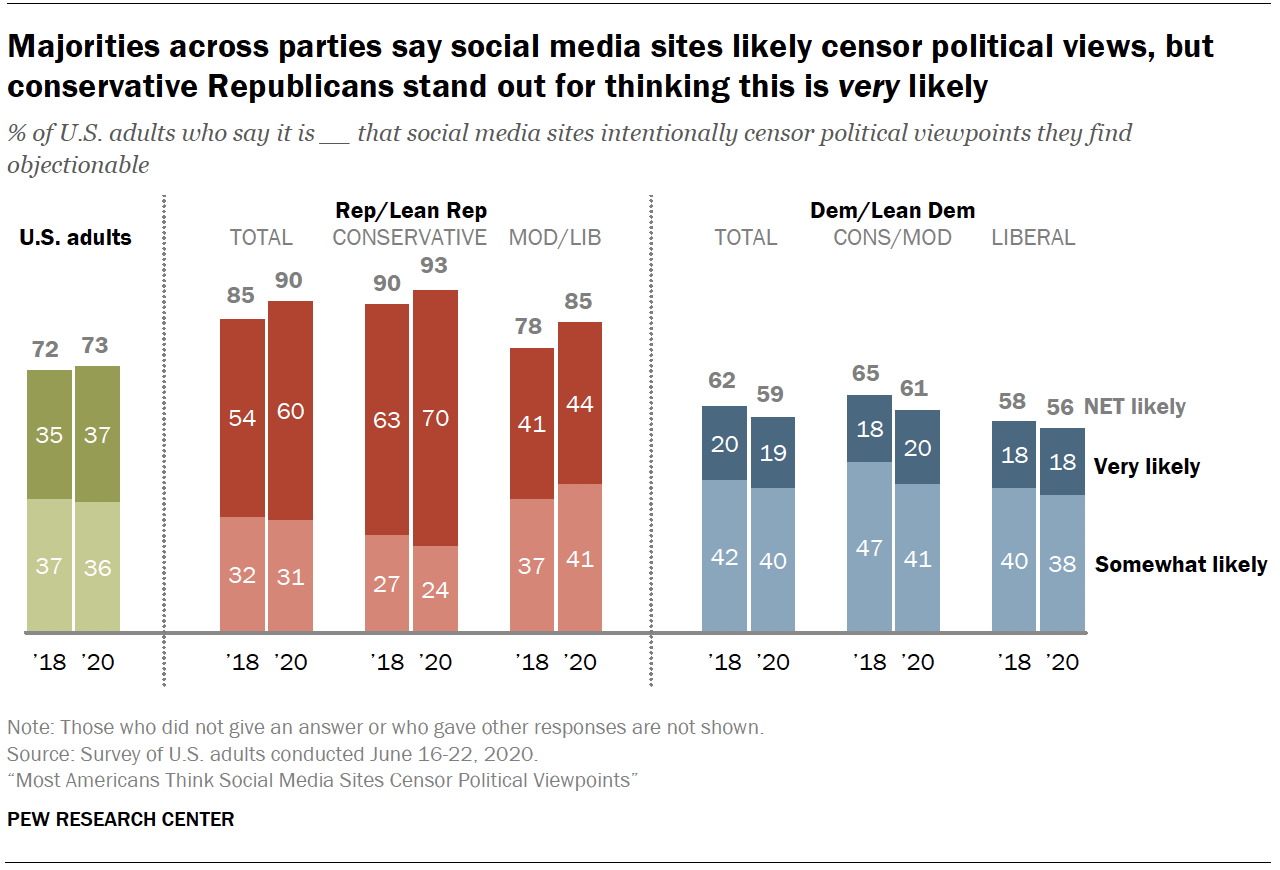

This has become a particularly pointed issue in politics – with critics accusing tech firms of political bias and stifling open discussion . Amid these concerns, a Pew Research Center survey conducted in June finds that roughly three-quarters of U.S. adults say it is very (37%) or somewhat (36%) likely that social media sites intentionally censor political viewpoints that they find objectionable. Just 25% believe this is not likely the case.

Majorities in both major parties believe censorship is likely occurring, but this belief is especially common – and growing – among Republicans. Nine-in-ten Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party say it’s at least somewhat likely that social media platforms censor political viewpoints they find objectionable, up slightly from 85% in 2018, when the Center last asked this question.

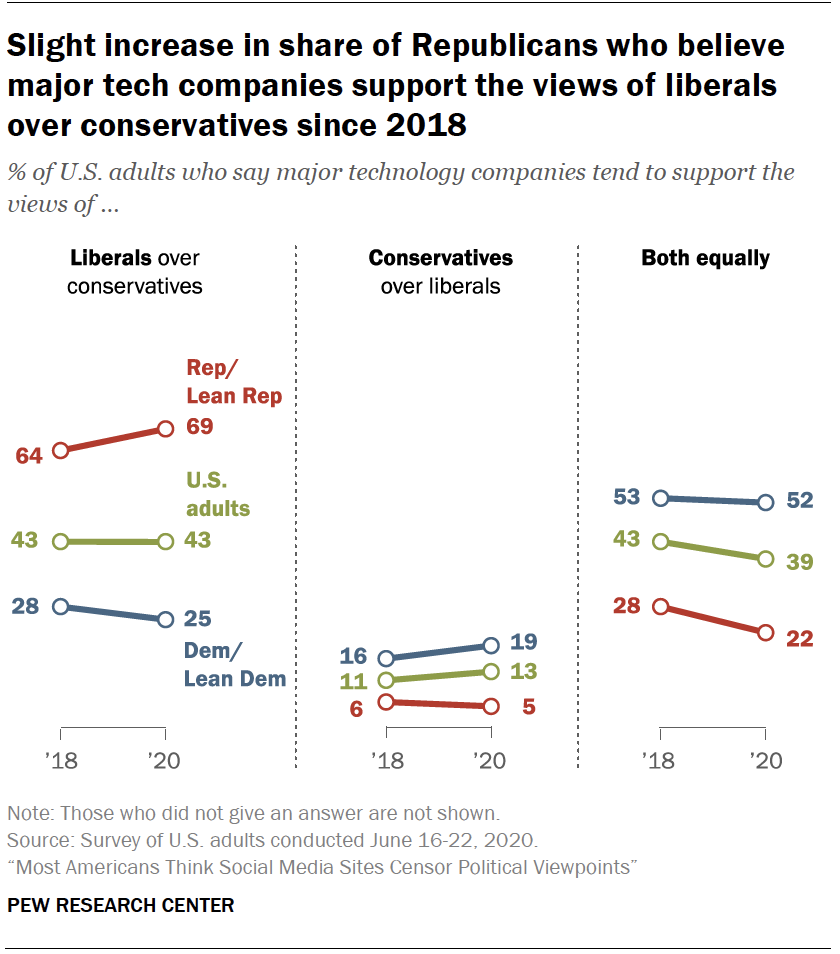

At the same time, the idea that major technology companies back liberal views over conservative ones is far more widespread among Republicans. Today, 69% of Republicans and Republican leaners say major technology companies generally support the views of liberals over conservatives, compared with 25% of Democrats and Democratic leaners. Again, these sentiments among Republicans have risen slightly over the past two years.

Debates about censorship grew earlier this summer following Twitter’s decision to label tweets from President Donald Trump as misleading. This prompted some of the president’s supporters to charge that these platforms are censoring conservative voices.

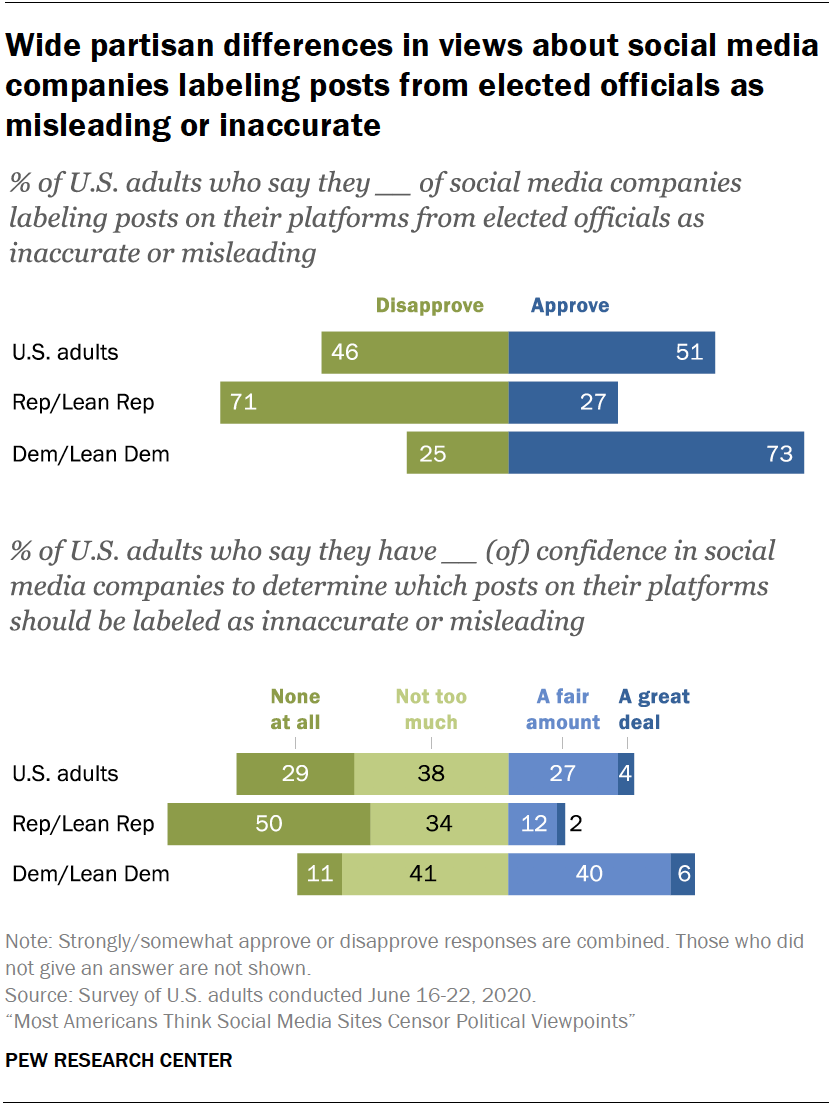

This survey finds that the public is fairly split on whether social media companies should engage in this kind of fact-checking, but there is little public confidence that these platforms could determine which content should be flagged.

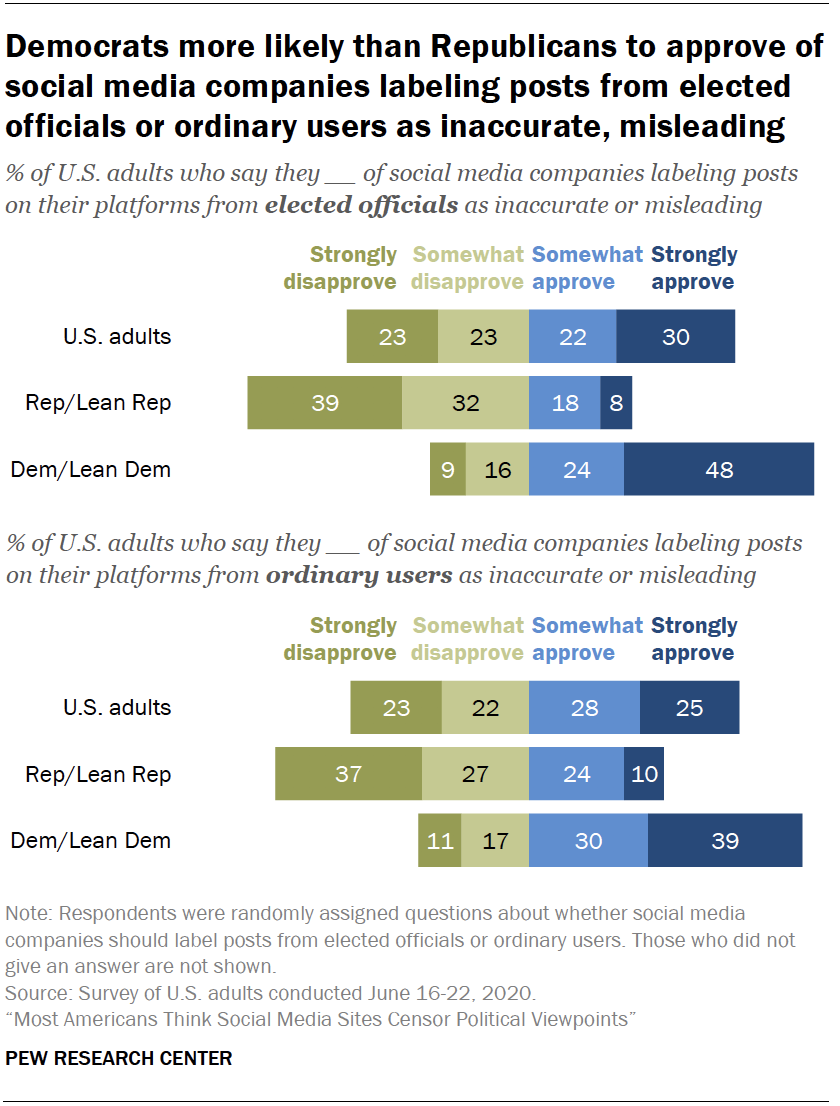

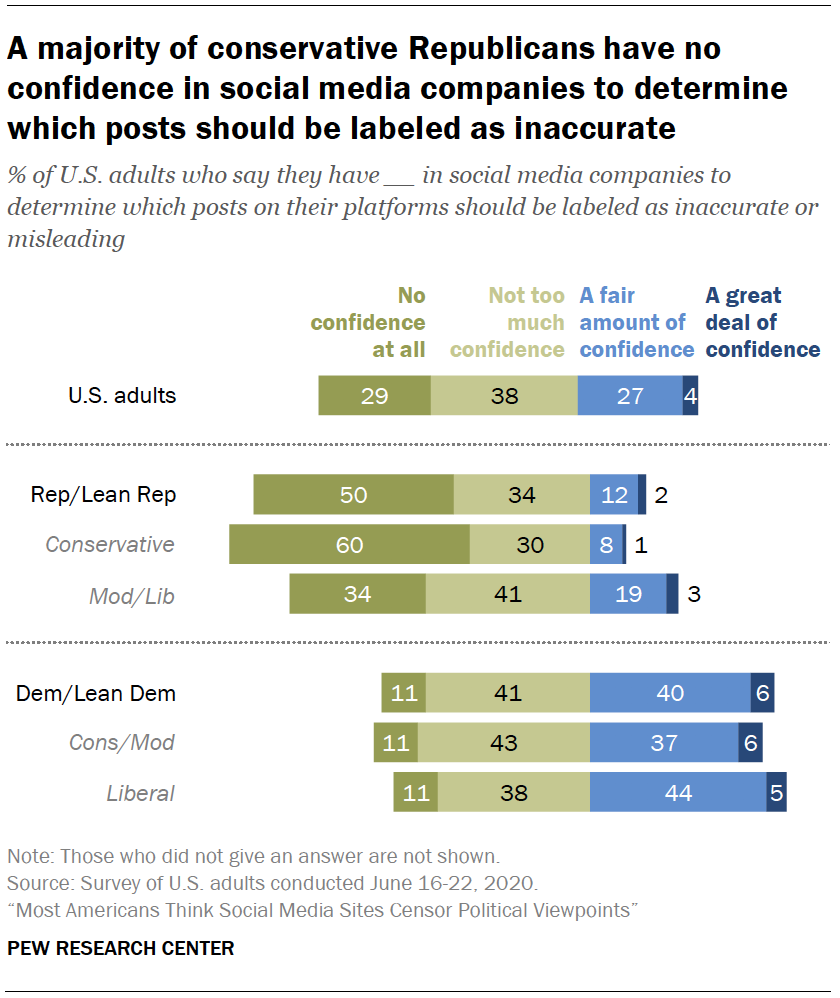

Partisanship is a key factor in views about the issue. Fully 73% of Democrats say they strongly or somewhat approve of social media companies labeling posts on their platforms from elected officials as inaccurate or misleading. On the other hand, 71% of Republicans say they at least somewhat disapprove of this practice. Republicans are also far more likely than Democrats to say they have no confidence at all that social media companies would be able to determine which posts on their platforms should be labeled as inaccurate or misleading (50% vs. 11%).

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey of 4,708 U.S. adults conducted June 16-22, 2020, using the Center’s American Trends Panel .

Views about whether social media companies should label posts on their platforms as inaccurate are sharply divided along political lines

Americans are divided over whether social media companies should label posts on their sites as inaccurate or misleading, with most being skeptical that these sites can accurately determine what content should be flagged.

Some 51% of Americans say they strongly or somewhat approve of social media companies labeling posts from elected officials on their platforms as inaccurate or misleading, while a similar share (46%) say they at least somewhat disapprove of this.

Democrats and Republicans hold contrasting views about the appropriateness of social media companies flagging inaccurate information on their platforms. Fully 73% of Democrats say they strongly or somewhat approve of social media companies labeling posts on their platforms from elected officials as inaccurate or misleading, versus 25% who disapprove.

These sentiments are nearly reversed for Republicans: 71% say they disapprove of social media companies engaging in this type of labeling, including about four-in-ten (39%) who say they strongly disapprove. Just 27% say they approve of this labeling.

Liberal Democrats stand out as being the most supportive of this practice: 85% of this group say they approve of social media companies labeling elected officials’ posts as inaccurate or misleading, compared with 64% of conservative or moderate Democrats and even smaller shares of moderate or liberal Republicans and conservative Republicans (38% and 21%, respectively).