For Teachers

Home » Teachers

Career Research Projects for High School Students

Immersive projects are a great teaching tool to get students excited about a potential career path.

As a teacher or homeschooler of high school students, you know the importance of in-depth, hands-on instruction. The more your students see how to apply their career planning and exploration skills, the better. Check out these career research projects for high school students that you can use in your classroom immediately! You can head to our careers curriculum center for lesson plans and more materials you can use as well.

Career Research Projects – Essays and Written Products

Sometimes, the best approach is the simplest. These projects require students to research and type up essays or written reports.

- Career Research and Readiness Project: In this project , students take a personality assessment to see what kinds of careers they may enjoy. They research the job application and interview process, narrow their search to a few career choices, and then set SMART goals to help them achieve their dreams.

- Career Research Project Paper: Students will like this project’s simple, straightforward instructions and layout. The components are broken into manageable chunks, letting your high schoolers tackle the project in parts. By the end, they will produce a well-researched essay highlighting their career.

- 3-Career Research Report: In this project , students choose three careers to focus on and create a written report. They learn MLA documentation, write business letters to organizations, take notes, and go through the formal writing process. This project has everything your students need to develop their career research reports with a rubric, parent letter, works cited page instructions, and more.

- STEM Careers Research Poster and Brochure: Students conduct comprehensive research in this project , using what they learn to create several items showing their knowledge. They research and learn about a specific career and make a posterboard presentation. Then they can create a brochure, present their findings to the class, and answer any questions that classmates and others may ask.

- Job Research Project: In this project , students first do research on any career they want. They must look up the various requirements, necessary skills, salary, and other details about the profession. They end with a thorough essay about their career, hopefully armed with the knowledge to help them in the future. The project is customizable to adapt to multiple grades, so your high school students will all benefit from the project.

Career Research Projects – Digital Presentations

Fusing technology and research, these projects allow kids to show their knowledge through technology. Students create digital presentations and share them with the class using PowerPoint, Google Slides, and other formats.

- Career Research Project: This project works with many grades, and teachers can customize it to fit their students’ levels. They use PowerPoint to make a comprehensive slide show to demonstrate their knowledge. It breaks down career research into ten slides (you can add more as needed), and students will have a solid understanding of their future career path by the end of the assignment.

- Career Presentation Project: In this project , high schoolers need to research career clusters, narrow their choices down to only one profession, and find many details about it. They look up median salary, entry-level pay, education requirements, required skills, and any additional benefits or perks that would attract potential applicants. They put all this information into a PowerPoint or Google Slides presentation.

- Career and College Exploration Project: This project is broken down into clear and detailed descriptions for each slide of the presentation. It differs from other projects on the list because it weaves college research into the assignment, showing students the connection between education and careers. With 22 slides to complete, students will have an in-depth understanding of their chosen careers and how to navigate school and plan for future success.

- Career Exploration Project: This project is unique as it takes a realistic approach to career exploration, requiring students to find the pros and cons of three potential careers. They see that every job has perks and drawbacks, and part of pursuing a specific one comes down to their personal preference. The project includes a detailed outline, so students know precisely what to research and have on each slide of their digital presentation. Presenting their findings is a significant part of their grade, which helps strengthen their accountability, quality of work, and public speaking skills.

- Life Skills Career Research Project: This project is an excellent blend of hands-on production and digital skill-building, letting students show their findings in multiple formats. They research a career, finding things like education/training requirements, job responsibilities, drawbacks, benefits, opportunities for advancement, specific places of employment, and salaries. Students need to create a functional resume and attach it to the project. They use Google Drive to design poster components and can submit the project digitally or on a poster board.

Subscribe For Weekly Resources

.png)

Career Exploration Activities High Schoolers Will Actually Want To Do

Great college counselors and career advisors always strive to ensure that each student is able to develop a personalized roadmap for their future. Beyond creating a bridge between secondary school and postsecondary success, career exploration plays a critical role for students while in school and provides thoughtful reflection and self-examination as students choose their life path. High-quality career exploration helps give meaning to the learning students are doing while in school, provides focus for their decision-making and time, and inspires hope for where their learning and hard work can take them.

Many schools and districts offer students annual or semi-annual career days and fairs as a primary channel for career exploration. Often times these events highlight individuals in the most common career roles or representatives from local businesses and business community organizations with brand recognition. Though these assemblies are important, they do not, on their own, impactfuly engage students in an ongoing process of deeper exploration necessary to drive meaningful questioning, engagement, and speculative research throughout secondary school.

Because of the important role it plays, career exploration must be ongoing and interesting to students in order to effectively engage them and promote motivation and enthusiasm. Counselors and educators can play a key role in finding ways to embed innovative practices to help students explore possible careers, learn about a much broader set of potential career options, and receive sufficient time and guidance--all allowing students to deeply consider their postsecondary career paths.

Innovative, Engaging Activities And Practices

In order for career exploration activities to be meaningful and exciting to today’s high school students, they need to be interactive and relevant. They must involve opportunities for student voice and choice, allowing students to explore and discern what appeals to them and what does not. And, in order to work within a college and career readiness program, the activities need to be scalable and accessible for all students.

Use Technology to Connect Students with Career Role Models

Today’s students are all 21st Century natives. They learned to read with books and apps. Video calls are just as common as telephone calls. They are used to using digital devices to connect with people near and far. Technology has made it much easier to connect students to information and resources beyond the school walls and get them excited about future career possibilities. Encourage students to explore websites that connect them with first-hand insights of professionals from around the world.

- Career Village : This online community provides a forum for students to ask questions about career exploration and planning directly to current professionals. From “How much does a music producer earn?” to “How to find your dream job,” students are able to have their specific questions answered from real-life professionals working in the fields they are exploring.

- Job Shadow : At Job Shadow, students can read interviews from professionals working in a vast number of fields, including some more unique professions that might be of interest to students such as jobs in the arts, roles that involve work with animals, and “jobs you may not have heard of.” Students can also search for interviews based on compensation structure or work environment.

Use Virtual Reality to Explore Career Options

Hands-on, interactive, and dynamic experiences are important to engage students and give them a realistic window into what a career will entail. Some of the most innovative work in career exploration is utilizing virtual reality (VR) to provide immersive experiences for students to do jobs. Though internships, apprenticeships, and other immersive, real-world experiences are only possible for a small number of students, VR can provide access to the environments, tools, and opportunities in a wide variety of industries without leaving the classroom.

- Oculus VR Career Experience : This free resource designed for the Oculus Go platform, the most popular consumer VR headset, provides students with the opportunity to learn the complex world of pipe fitting, HVAC, and welding. The application was designed by the International Training Fund of the United Association, an international union of plumbers, fitters, and technicians, to provide students with an immersive and realistic window into these jobs.

- ByteSpeed : ByteSpeed, available for a fee, provides students ranging from elementary school to higher education a wide variety of career VR experiences including agriculture, fashion design, health care, and engineering.

Partner with Local Chambers of Commerce and Beyond

A core piece of career planning needs to include job opportunities within one’s community. A local chamber of commerce is the perfect resource. Encourage the local chamber of commerce to have member businesses create YouTube videos spotlighting their work and different types of potential jobs for students. Some local business organizations have partnered with school districts to create sites geared specifically toward secondary students to share the types of jobs available and the skills needed to do those roles. You might also invite local businesses to provide teachers with recruitment, application, and training materials for students.

- Career Explore NW : A school district in Spokane, Washington has partnered with local businesses and the public broadcasting station to create an impressive web platform that enables career exploration, promotes local agriculture and industry opportunities, and connects local businesses with students.

- UpSkill Houston : In Houston, Texas, the Greater Houston Partnership has brought the school district into the workforce development process. Realizing that economic development requires a skill-ready workforce at hand, rather than importing it from other communities, the organization formed this partnership and site aimed at connecting high school students with relevant careers.

- SchooLinks : SchooLinks provides an Industry Partnership Portal which assists schools and districts in nurturing partnerships. Providing student access, calendaring events, and empowering local businesses to connect to students helps create real-world opportunities for students to explore local career options.

Include A Diversity of Voices

Students are more likely to deeply engage with career exploration activities when they can personally relate to or see themselves in career role models. It is vital that schools offer students exposure to a wide diversity of individuals representing possible career pathways. Expanding conceptions of role models for students both opens the minds of current students and works to upend historical stereotypes and barriers long-term.

- Invite Recent Alumni: Consider offering students opportunities to talk with and learn from individuals still early in their career trajectory, rather than just focusing on those who have achieved long-term career success. You might invite recent alumni to talk with students about their experiences both in college or career training, applying for positions, and during their first weeks and months in a new role. This gives students much more relatable information and advice that likely feels more relevant to their current decision-making and thinking.

- Ensure Gender, Racial, and Ethnic Diversity in Role Models : Across fields, take special care to include representatives that fall outside often held gender stereotypes for particular careers. For instance, spotlight women working in positions from predominantly male STEM careers. And, have male representation from nursing or teaching positions, which are often female-dominated careers. The Career Girls website is a great resource geared at female students to provide them with empowering role models and tools to explore future career options. Ensure racial and ethnic diversity in connecting students with professionals as it is fundamental that all students have role models that they can personally identify with.

Honor And Value A Wide Array Of Career Pathways

Engaging career exploration also includes guidance and activities to help students expand their thinking beyond what they conceive of as likely career paths. Many times student career planning and exploration is constrained by what they know--either what their own family members do for a living, professionals they interact with in their own lives such as teachers, doctors, and coaches, or those they see on television and the internet. This leaves major gaps in student understanding of all the potential opportunities and fields that exist. Educators can have major impacts on postsecondary success by showing students the wide array of options that are possible and connecting those options with student strengths and preferences.

Additionally, many career exploration curricula often default to college planning as a core component. However, in today’s economy, there are a myriad of good job options that do not require a four-year college degree. It does a disservice to students to only focus on career paths that extend from college completion. Career counselors can play an important role in helping students to see these different pathways--from straight to career, to technical education, to the military, to community college, to four-year degrees and beyond--as all potentially worthwhile to consider. This makes career planning and exploration accessible to students who do not think that college is right for them and helps all students understand their options as they make important life decisions.

Relevant And Productive Career Exploration For All Students

As you develop and plan your career exploration activities, take time to regularly survey students for fields they would like to explore, the kinds of activities that resonate with them, and for feedback on past activities and events. By aligning career exploration activities with student interest and choice, it is much more likely that students will engage more deeply and reflectively.

When students do this, they are able to see connections between future career goals and their current learning; they are able to figure out the kinds of work they enjoy and those they do not; and, they are able to understand how their strengths and preferences map onto future possibilities. By deeply exploring career possibilities during secondary school and critically thinking about the associated realities, students are able to enter postsecondary life knowing they are making active and well-informed choices. Ultimately, if students are excited about these activities and thoughtfully engage with them, they are better prepared for the entire pathway to a career.

Centralizing career exploration activities in the same place as goal setting, college exploration and graduation plans can help students see the little, and big pictures. Check out how SchooLinks can consolidate it all for your district.

Request a demo

Download your free ebook.

Fill out the form below to access your free download following submission.

Join the free webinar.

Fill out the form below to gain access to the free webinar.

Get In Touch

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy . You may receive marketing emails and can opt out any time.

Related Content

Career Exploration Activities: A Comprehensive Guide for High School Students

By Tom Gurin

Fulbright Scholar; music composer, historian, and educator

By Surya Ramanathan

Johns Hopkins University, B.S. in Applied Mathematics and Statistics, B.S. in Economics, and M.S. in Applied Economics

6 minute read

The journey of self-discovery and career exploration can be both exciting and daunting. Luckily, there are numerous ways you can uncover your passions and interests

Career exploration is a helpful way for students to consider their interests and goals, and to focus their energies in the right direction. Here, we’ll delve into nine effective career exploration activities you could do to help figure out a potential career path to pursue.

Why Are Career Exploration Activities Important For Students?

Although some people might be lucky enough to find their ideal careers by accident, for most, identifying the right fit means taking time to plan and reflect. Even if you change your mind or go in a different direction later on, exploring careers now might help you uncover something important about your goals for your professional life.

Maybe you already have an idea (or several) about what you want your career to look like. That’s great! The exploration you do as a student could help you narrow in on your strongest interests or open your eyes to career paths you never knew existed . For students who want to be productive and efficient with their time and studies, exploring career options is an important step for building a direct link between their education and their futures.

How Do Career Exploration Activities Work?

Career exploration activities should be enjoyable! They can take many forms, including brainstorming sessions, games, and conversations with experts in a field.

Check out our Pathfinders career discovery program to match with experts and get personalized guidance and advice.

These activities require students to reflect on their goals, values, and skills. For some students, this might be the first time that you consider questions about your future career. To help get the conversation going, try out some fun career exploration activities that can help students find what they love .

A proven college admissions edge

Polygence alumni had a 92% admissions rate to R1 universities in 2023. Polygence provides high schoolers a personalized, flexible research experience proven to boost your admission odds. Get matched to a mentor now!"

9 Career Exploration Activities for Students

1. career mind mapping: visualizing your connections.

Building a career mind map is an excellent first activity for students to draw connections among key interests and goals. Once completed, a mind map is a tool for visualizing connections among concepts that are important to you and that could shape your career path. Here’s how it works:

Grab a large piece of paper (so that you aren’t limited in space) and a pen or pencil. (A diagramming software like Google Drawings will also work.)

In the center of the page, write a word or short phrase that is important to you when you think about your future career. Don’t think too hard about what to write; just jot down what comes to mind (e.g., “Helping people”, “Leadership”, “Exploring”, “Science”).

Next, draw one or two (or several) lines extending outward from what you wrote. At the end of each line, write another word or phrase that is connected to the first concept. Each word or phrase should connect to another, and your priorities.

Continue drawing lines and connections to new concepts, building outward from the center to create a tree of interrelated ideas that you want to prioritize when building your career.

Building a career mind map is a great first activity to help you structure your brainstorming and get started with career exploration . Remember: the goal of this activity is to start thinking about the connections among different concepts that you want to explore.

2. Self-Assessment Surveys: Uncover Your Strengths and Interests

To embark on a journey of self-discovery, it’s important to understand your strengths and interests. There are various online self-assessment surveys and quizzes designed specifically for high school students. These assessments can be extremely helpful in assisting you with identifying your personality traits, strengths, and preferences. Websites like CareerExplorer , Princeton Review , and InternMart provide comprehensive assessments that match your qualities with suitable careers. By taking these surveys, you can get a better idea of the fields that might resonate most with you. Here are some career quiz questions to get you thinking about your choices right now:

Which subject(s) do you enjoy most in school?

What are your goals for your education?

Picture yourself in your ideal future workspace. Where do you find yourself? In an office? In a lab? In a forest?

What is your work style? For example, do you like to organize and plan well in advance? Do you like to multitask? Do you look for ways to be creative?

Assuming equal pay, would you rather be a journalist or a plant biologist? Would you rather build bridges or be a librarian?

Do you prefer to work on your own or to collaborate with other people?

3. Informational Interviews: Gain Insights from Professionals

Sometimes, the best way for students to learn about a career path is by talking to someone who’s already in the field. Reach out to professionals in careers that interest you through a platform like LinkedIn and request to speak with them for 15-30 minutes. This is an excellent opportunity to ask questions about their job, daily tasks, and what they enjoy most about their work. If there is an expert in your school or local community, try asking them some of these questions:

When did you discover that you wanted to specialize in this field?

Have you had any surprises in your career path?

How is the work/life balance in this field?

What is the most challenging aspect of your work?

These conversations can provide you with valuable insights that go beyond what you might find in a job description, helping you understand the nuances of different careers.

4. Job Shadowing: Experience a Day in the Life

If you’re curious about a particular profession, a job shadowing experience may be beneficial. Spend a day observing a professional in action and get a firsthand look at their tasks and responsibilities. This experience will not only give you a realistic sense of what a typical day looks like but will also very likely impress the person you are shadowing by showing incentive, creating a potential job opportunity. It can also help you assess whether the day-to-day activities align with your interests and aspirations.

5. Volunteering and Internships: Hands-On Experience

Volunteering and internships offer a hands-on approach to career exploration. Look for opportunities in fields that intrigue you, even if they’re unpaid or short-term. Whether it’s volunteering at a local hospital, interning at a marketing agency, or assisting at an animal shelter, these experiences provide valuable insights into the practical aspects of different professions. You’ll gain real-world skills, build your resume, and get an idea of what it’s like to work in that industry.

6. High School Clubs and Organizations: Try Something New

Your high school likely offers a variety of clubs that can introduce you to different fields of interest. Join clubs related to science, art, debating, coding, or any other subjects that intrigue you. The best part? You’re taking on minimal risk: you won’t be dedicating years, and if you’re uninterested in one area, you can easily switch to another club to try something new. Engaging in extracurricular activities not only helps you explore your passions but also allows you to meet like-minded peers and mentors who can guide you on your journey.

7. Online Courses and Workshops: Expand Your Knowledge

The internet is a goldmine of resources for learning about different careers. Enroll in online courses or workshops related to fields you’re curious about.

Polygence Pods, for example, are 6-week programs specifically designed for high school students to work with mentors and a small peer group on research about a specific interest. Pods cohorts are offered throughout the year in a variety of topics. The Polygence Pods program page is the best way to learn about specific dates and topics for upcoming Pods. Space is limited, so reserve your spot early if you’re interested in joining.

Other websites like Coursera , edX , and Khan Academy offer a wide range of courses on diverse topics. These courses can provide you with a foundational understanding of different industries and help you decide which one resonates with you the most.

8. Research Projects: Dive Deep into Topics of Interest

Undertaking research projects can be an exciting way to explore potential careers. If you’re passionate about a specific subject, consider delving deeper into it through independent research through a university, or even a company like Polygence.

Middle and high school students who enroll in Polygence’s Core research mentorship program work a research project of their choosing with a mentor who has expertise in the project’s subject matter. Each student’s Polygence experience is uniquely designed and student-led. Teens who have completed projects with Polygence have indicated their research helped them discover a deep passion for specific fields of study. Lily Nguyen’s Polygence experience led her to choose a college major at UC Berkeley. In Lily’s words, Polygence:

“definitely made me more interested in biology and science. Before my senior year, I didn't really take any biology classes yet. But when I was going through the project, I found that I really enjoyed learning about this kind of stuff. It really helped cement for me that yes, biology is a good major for me to pursue.”

Whether it’s writing a paper, creating a presentation, or conducting experiments, this hands-on experience can reveal new aspects of a field and ignite your curiosity even further.

Do your own research through polygence

Polygence pairs you with an expert mentor in your area of passion. Together, you work to create a high quality research project that is uniquely your own.

9. Attend Career Fairs and Workshops: Network and Learn

Many schools and communities organize career fairs and workshops that bring together professionals from various industries. These events offer students a chance to network, ask questions, and gain insights directly from experts. Make the most of these opportunities by attending talks, participating in workshops, and connecting with professionals who share your interests.

Choose Your Unique Career Exploration Journey

This is by no means an exhaustive list of ideas when it comes to the ways students can explore careers. There are many routes you could take to explore a career path that is of potential interest to you, but this list is a great way to get started.

Polygence is also here to help! Our Pathfinders program is a career discovery program specifically designed to help students find what they love . We’ll match you with three different expert research mentors in fields of your choice. In addition to learning about each field, you’ll get answers to your specific questions and direct, personalized advice from your mentors to help guide you through your career discovery journey.

For Businesses

For students & teachers, 4 relatable career exploration activities for high schoolers.

Jeannette Barreto

As educators, we have the unique opportunity to shape the future of our students and prepare them for the world beyond the classroom. A crucial aspect of this preparation is guiding students through career exploration. Career exploration helps students understand their interests and passions and equips them with the essential skills and knowledge to make informed decisions about their future paths. In this blog, we will delve into the significance of career exploration and how EVERFI, an innovative digital learning platform, can assist teachers in empowering their students throughout this transformative journey. November’s National Career Development Month is an especially relevant time in the school year to explore these concepts in the classroom.

What is Career Exploration?

Career exploration is the process by which individuals, particularly students, delve into the world of work to understand their interests, values, and aptitudes in relation to potential careers. It’s not just about finding a job; it’s about discovering where one’s passion, skills, and the demands of the labor market intersect. Through a myriad of activities, such as internships, career assessments, informational interviews, and research, individuals gain a clearer perspective of the professions available and the educational pathways leading to them.

By undergoing career exploration, students are better positioned to make informed choices about their academic pursuits and future professional endeavors, ensuring a more fulfilled and aligned career journey.

The Importance of Career Exploration

In today’s fast-paced world, understanding potential career paths early on can drastically affect a student’s future. This section emphasizes why it’s crucial to start this exploration early and how it benefits the students’ overall development.

Understanding the Impact: Why Career Exploration Matters

Career exploration is a fundamental part of personal and academic development. By encouraging students to explore various career paths, we enable them to envision their future possibilities and set meaningful goals. This early exposure to diverse professions broadens their horizons and instills a sense of purpose in their educational pursuits.

Career exploration also aids in the development of self-awareness. When students engage in activities that align with their interests and strengths, they become more confident in their abilities, leading to improved academic performance and a higher level of motivation.

Building a Solid Foundation: Early Career Awareness in Education

Introducing career awareness at an early age can profoundly impact students’ future choices. As teachers, we can incorporate age-appropriate career exploration activities into our lessons, exposing young minds to various professions and industries. By creating a positive and supportive learning environment, we can nurture their curiosity and aspirations from the beginning of their educational journey.

Nurturing Students’ Interests: How Career Exploration Encourages Motivation

Students are more likely to stay engaged in their studies when they see the relevance of their education to their future goals. Career exploration bridges the gap between classroom learning and real-world applications, allowing students to connect academic subjects to practical uses in the workforce. This connection fosters intrinsic motivation and a thirst for knowledge as students recognize how their studies directly contribute to their future success.

4 Relatable Career Exploration Activities for High Schoolers

Helping high school students explore potential career paths is vital to preparing them for their future. By engaging in interactive and relatable activities, students can gain valuable insights into various professions, develop essential skills, and make informed decisions about their career aspirations. In this blog, we present four relatable career exploration activities designed to spark curiosity and inspire high schoolers as they embark on their journey of self-discovery.

1. Career Shadowing Day

Organizing a career shadowing day allows students to gain firsthand experience of a typical day in a particular profession. Collaborate with local businesses, hospitals, law firms, tech companies, or workplaces that align with students’ interests. Prioritize disciplines that students have expressed curiosity about or might consider as future career options.

On the designated day, pair students with professionals in their chosen fields and allow them to shadow these experts for a few hours. Please encourage students to take notes and ask questions about their daily yaks, responsibilities, and the educational pathways that led to their careers. After the experience, hold a debriefing session where students can share their reflections and insights.

2. Career Interest Inventories

Career interest inventories are valuable tools that help high schoolers identify potential career paths based on their interests, values, and personality traits. Various online resources and assessments, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) or the Holland Code test, provide insights into career preferences.

Have students complete one or more of these inventories and then discuss the results together. Please encourage them to research careers that align with their interests and explore educational requirements, job outlook, and potential salary ranges for each profession.

3. Mock Interviews, and Resume Building

Preparing for job interviews and building a compelling resume are crucial skills for future careers. Organize mock interview sessions where students take turns being both interviewers and interviewees. Provide sample interview questions and offer constructive feedback to help them improve their communication skills and confidence.

Simultaneously, guide students in creating their resumes. Highlight the importance of tailoring the resume for specific job applications, emphasizing relevant skills, experiences, and achievements. Allow students to explore different resume formats and templates to find one that best represents their unique qualities.

4. Career Panels and Guest Speakers

Invite professionals from various fields to participate in career panels or deliver guest lectures at your school. Create a schedule of sessions throughout the school year, covering multiple careers, industries, and educational paths. These sessions can be held during lunch breaks, after-school hours, or incorporated into existing career-focused classes.

During these interactive sessions, please encourage students to ask questions about the speakers’ career journeys, the challenges they faced, and advice they have for aspiring professionals. Hearing real-life experiences and insights from many industry experts can be immensely impactful for students and provide them with realistic views of their dream careers.

Keys to Your Future: College and Career Readiness

The course aims to equip students with the necessary skills to navigate toward a fulfilling college experience and a successful career. Through interactive real-world scenarios, students explore lessons on college exploration, financial literacy, career readiness, and personal development.

College Exploration

College Exploration – assists students in researching and identifying colleges that align with their interests, career goals, and academic strengths. It also covers the application process, financial aid options, and scholarship opportunities, helping students develop well-informed strategies for pursuing higher education.

Financial Literacy- equips students with essential financial skills, including budgeting, managing student loans, and building credit responsibly. Students learn how to make informed financial decisions, avoid common pitfalls, and plan for their financial future, ensuring they are financially savvy as they embark on their college and career journeys.

Career Readiness

Career Readiness- designed to help students explore potential career paths and develop the skills needed to thrive in the workplace. They also learn about resume building, interview preparation, and networking strategies.

Personal Development

Personal Development – emphasizes self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and goal setting to empower students to overcome challenges and maximize their potential. Students are encouraged to explore their strengths, weaknesses, and growth mindset.

Benefits of Career Exploration

Career exploration offers a plethora of advantages that extend beyond simply identifying a suitable profession.

Boosting Confidence

By understanding potential career paths, students gain a sense of direction. This knowledge empowers them, bolstering their confidence. As they navigate the realm of potential professions, they start recognizing their worth and the value they could bring to various roles.

Academic and Career Alignment

One of the major pitfalls students often face is pursuing an educational pathway that doesn’t align with their career aspirations. Career exploration allows students to tailor their academic choices, ensuring they’re on the right track from the start. This alignment not only streamlines their journey but also maximizes the return on their educational investment.

Reducing Future Job Dissatisfaction

Making uninformed career choices can lead to job dissatisfaction in the future. By researching and understanding different professions early on, students are more likely to choose careers that resonate with their passions and strengths. This proactive approach can drastically reduce the likelihood of mid-career crises or frequent job switches later in life.

Empowering The Next Generation Through Career Exploration

Engaging high school students in relatable career exploration activities can significantly influence their future choices and aspirations. Two of EVERFI’s newer courses: Accounting Careers: Limitless Opportunities and Data Science Foundations expose high school students to the world of opportunities that exist within these career fields. By providing hands-on experiences, career inventories, mock interviews, and insights from industry professionals, we empower our students to make informed decisions about their future paths. These activities foster self-awareness and encourage curiosity, determination, and a sense of purpose as they embark on their exciting journey of self-discovery and career exploration as educators. Let’s continue to inspire and support our students as they explore the endless possibilities that lie ahead in their professional lives.

___________________________________________________________

Free for K-12 Educators

Thanks to partners, we provide our digital platform, training, and support at no cost.

See why 60k+ teachers were active on EVERFI digital resources last school year.

Sign Up Now

Be sure to subscribe to our K12 YouTube channel and check out these related videos to help with back to school lesson planning:

College and Career Readiness Skills for HS Students

Teaching Data Science in High School

Accounting Careers: Limitless Opportunities

Stay Informed

Thanks! Look out for our next newsletter, coming soon.

Explore More Resources

10 teacher mental health tips you can put into practice today.

There has been little focus on teachers balancing COVID-19 & remote teaching. That’s why we put together ten mental health tips for t ...

Elementary Schooled Podcast: What is the NFL Character Playbook Program for Students? with ...

Character Playbook course for middle and high school students, where students learn about character building and specific skills for ...

Beyond the Glass Ceiling - The Rise of NFL Trailblazers Jennifer King and Maia Chaka

Learn about two women who persevered against all odds to break barriers as the first females in their NFL coaching and officiating ro ...

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to help high school students with career research.

High school students often tire of being asked, “What are your career plans?” Some students have no idea how to answer the question. Others may give a rote answer just to stop the questions. There are actually so many career choices available that high school students can pursue that they need direction in order to discover their own interests and skills. They may discover that opportunities are available they never even thought of before. Here are just a few suggestions that may help in career research for high school students.

Brainstorming

This may seem like a simple suggestion, but it is a good first step. Students should make a list of things they like and do not like to do and classes they like and do not like. For example, do they like history class but hate math class or vice versa? Do they like to work in groups or do they prefer to work alone? Do they like to work indoors or outdoors?

Assessment tests

There a variety of assessment tests that may be administered at high schools. If not, they can be found online. Some examples are:

- Myer-Briggs Test: This analyzes personality characteristics and how a person interacts with people or if they prefer not to interact with people at all.

- Strong Interest Inventory: This helps students who are having trouble identifying their interests and helps focus on what a student truly enjoys doing.

- Self-Directed Search: This test focuses on identifying skills and interests.

- Skill Scan Test: This focuses on seven specific skills and assists a student in determining which skills they have or want to develop.

Assessment tests are just stepping stones to identifying potential careers. Results should not be used to direct a person to or away from a specific career but should be used only as tools to help identify career choices.

Research potential careers

A few specific careers can be identified in order to pursue career research for high school students. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes an Occupational Outlook Handbook which provides detailed information for every possible job including:

- Job description

- Specific employers or types of employers

- Salary ranges

- Expected job growth over the next few years

- Educational requirements

- Where the jobs are located

Informational interviews

Students may know or can be introduced to someone who works in a job the student is interested in pursuing as a career. Guiding the student to develop interview questions of the professional person can be helpful. Students can get real answers to their career questions from people who actually work every day in the career of interest. Students can be guided to ask questions such as:

- How did the person train for the job?

- What does the person like best about the job?

- What does the person dislike about the job?

- What has the person learned that they wish they had known before pursuing the career?

- What advice does the professional have concerning what the student should and should not do in pursuit of the career?

Job shadowing

Some schools have job shadowing programs that give students the opportunity of actually working with a professional in the career of the student’s choice. The student arranges to spend several hours with the professional to “shadow” them and see exactly what they do on a daily basis.

If the school does not have a shadowing program established students can contact the local Chamber of Commerce for business directories and suggestions of professionals who may be contacted. Students can then set up individual job shadowing experiences.

You may also like to read

- How Teachers Can Help Prevent High School Dropouts

- Why Anxiety in Teens is So Prevalent and What Can Be Done

- Why Kids and Teens Need Diverse Books and Our Recommended Reads

- Websites that Help Students with High School Math

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Career and Technical Education , High School (Grades: 9-12)

- Teacher Toolkits and Curated Teaching Resourc...

- Online & Campus Master's in TESOL and ESL

- Online & Campus Master's in Higher Education ...

Our Services

College Admissions Counseling

UK University Admissions Counseling

EU University Admissions Counseling

College Athletic Recruitment

Crimson Rise: College Prep for Middle Schoolers

Indigo Research: Online Research Opportunities for High Schoolers

Delta Institute: Work Experience Programs For High Schoolers

Graduate School Admissions Counseling

Private Boarding & Day School Admissions

Online Tutoring

Essay Review

Financial Aid & Merit Scholarships

Our Leaders and Counselors

Our Student Success

Crimson Student Alumni

Our Reviews

Our Scholarships

Careers at Crimson

University Profiles

US College Admissions Calculator

GPA Calculator

Practice Standardized Tests

SAT Practice Test

ACT Practice Tests

Personal Essay Topic Generator

eBooks and Infographics

Crimson YouTube Channel

Summer Apply - Best Summer Programs

Top of the Class Podcast

ACCEPTED! Book by Jamie Beaton

Crimson Global Academy

+1 (646) 419-3178

Go back to all articles

Best Senior Project Ideas for High School Students + 42 Real Student Examples

/f/64062/1920x800/5aeb0da0d9/senior-project-ideas.jpg)

A senior project is one of the best ways you can make your application stand out to top schools like Harvard and Stanford. It can tell your story beyond academics. It can demonstrate leadership, ambition, initiative and impact. And it can make an impact on the world.

Choosing the right senior project can be tough. As a Former Johns Hopkins Admissions Officer and a Senior Strategist at Crimson, I’ve helped hundreds of students do it. In this post, I’ll show you my process for choosing a topic for your senior project. I’ll also show you real examples of senior projects that helped students get accepted to the Ivy League, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and more.

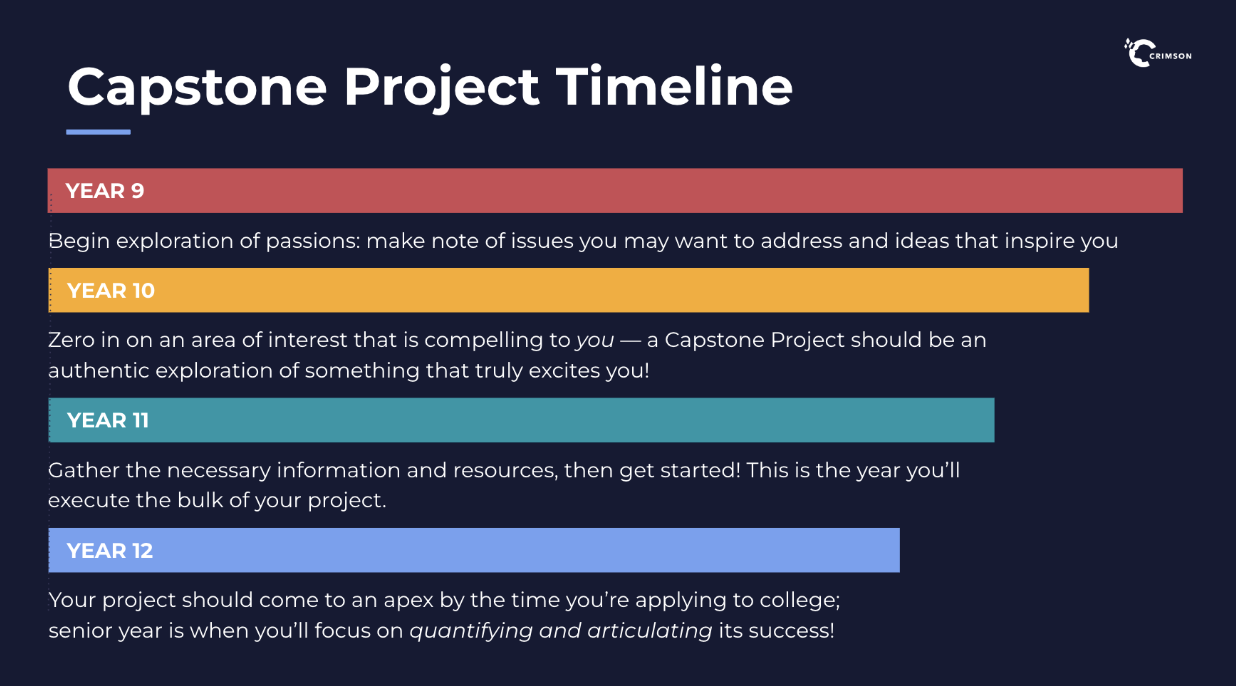

What is a Senior Project?

A senior project is also known as a “capstone project.” It’s a long-term project in which you can explore a topic that interests you outside the classroom. It can take many different forms, including:

- A detailed research paper

- An art exhibition

- A tech invention

- A business or startup

- A community service project

- A social media channel or podcast

It's all about picking something that resonates with you and showcases your abilities.

The impact of a well-done senior project extends beyond the classroom. It can enhance your college applications by showing your commitment and skills. It can set you apart in an application pool with thousands of academically qualified students.

Finally, the experience and skills you gain from your senior project can be valuable in future careers.

What are the Benefits of a Senior Project?

Most students applying to Top 20 universities have strong grades and test scores. Academics are important, but they only get your foot in the door. To make your application stand out, you need impactful extracurriculars. This is where a senior project comes in.

If you’re like most students applying, you won't already have a clear area of excellence in your application, like a national or international accolade. You’ll have to show your excellence in terms of the time and commitment you’ve given to their community. Senior projects are a great way to do this.

With a successful senior project, you can:

- Showcase personal qualities. Since a senior project is entirely yours, it showcases your ability to own and execute a unique project from start to finish. This shows leadership, initiative, and intellectual curiosity — qualities that admissions officers are looking for. A senior project can also show that you’re service-oriented, a creative thinker, looking for a challenge, and can overcome barriers.

- Demonstrate passion and dedication. A senior project shows that you’re passionate about a specific field and can commit to a long-term vision.

- Develop transferable skills. You’ll inevitably learn skills like time management, research, collaboration, or technical skills.

- Become an expert in the subject matter. By going deep into a topic, you’ll develop expertise that you might not get through passive learning.

Remember: Your senior project speaks volumes about who you are and why you deserve a place on campus!

Interested in learning more? Attend one of our free events

Learn how to get into ivy league universities from a former harvard admissions officer.

Wednesday, May 1, 2024 12:00 AM CUT

Join us to learn what Ivy League admissions officers look for, and how you can strategically approach each section of your Ivy League application to stand out from the fierce competition!

REGISTER NOW

Best Senior Project Ideas

The best senior project ideas are long-term, unique to you, and measurably impactful. I’ll show you some specific examples of senior projects by students who were admitted to top schools. But first, here are some general ideas to get you thinking.

- Design and implement a community garden, teaching sustainable agriculture practices and providing fresh produce to local food banks.

- Start a state-wide traveling library that reaches underserved communities.

- Develop a series of workshops for senior citizens or underprivileged youth to teach them basic computer skills, internet safety, and how to use essential software.

- Create a campaign to promote environmental awareness and conservation efforts in your community, focusing on recycling, reducing plastic use, or conserving local wildlife habitats.

- Establish a mentorship program pairing high school students with elementary or middle school students to provide academic support, life advice, and positive role models.

- Organize a cultural awareness event that celebrates diversity through music, dance, food, and educational workshops, fostering a more inclusive community.

- Launch a mental health awareness campaign that includes workshops, guest speakers, and resources to destigmatize mental health issues among teenagers.

- Research and implement a small-scale renewable energy project, such as installing solar panels for a community center or designing a wind turbine model for school use.

- Conduct and record interviews with community elders or veterans to preserve local history, culminating in a public presentation or digital archive.

- Develop an art therapy program for children in hospitals or shelters, providing an outlet for expression and emotional healing through creative activities.

- Create a series of workshops for your community focusing on fitness, nutrition, and healthy lifestyle choices, including sessions on exercise and cooking.

- Design and lead a financial literacy course for high school students, covering budgeting, saving, investing, and understanding credit.

- Research and write a book or guide on the history of your town or a specific aspect of it, such as architectural landmarks, founding families, or significant events.

- Start a coding club for elementary or middle school students, teaching them the basics of programming through fun and interactive projects.

- Organize public speaking workshops for students, helping them build confidence and communication skills through practice and feedback.

- Coordinate a STEM fair to encourage girls in elementary and middle school to explore science, technology, engineering, and math through hands-on activities and demonstrations.

- Produce a documentary film that explores a social issue relevant to your community, such as homelessness, addiction, or education inequality.

- Lead a project to refurbish a local playground. Fundraise, design, and collaborate with city officials to provide a safe and enjoyable space for children.

- Set up an ESL (English as a Second Language) tutoring program for immigrants and refugees in your community to help them improve their English skills and better integrate into society.

- Design and implement an anti-bullying campaign for your school or community, including awareness activities, support resources, and strategies for prevention.

- Organize a sustainable fashion show that promotes eco-friendly fashion choices, upcycling, and local designers, raising awareness about the environmental impact of the fashion industry.

- Start a podcast, blog, Youtube channel, or social media channel about a topic that interests you. Aim to reach a national or international audience.

- Start a club at your school and build its impact beyond your own school ecosystem.

- Start a campaign around an issue you care about and create change at your school, like “Meatless Mondays.”

- Create a competition for innovative startups

- Develop a product or service and sell it online. Create a business plan, marketing materials, and a way to track your progress.

- Fundraise for an existing charity or nonprofit.

- Found a new charity or nonprofit.

- Create or raise money for a scholarship fund.

Successful Real Senior Project Examples

To help you get a clear picture of what your senior project could look like, I’m going to share some actual senior projects that Crimson students have done. Below are 13 real examples of senior projects by students who were accepted to top universities like MIT, Stanford the Ivy League, Johns Hopkins, and UC Berkeley.

Business & Finance

Student accepted to mit.

Impact: Local

This student trained 24 unique groups (120+ people) to create innovative startups for 3 competitions. They also created a 15-lesson curriculum and online team-matching algorithm for the competitions.

Student accepted to Stanford

Impact: International

This student founded an organization to educate K–8 students on social entrepreneurship. It grew to 32 chapters with 12,453 members in 4 continents. It was endorsed by the UN, LinkedIn, and InnovateX.

Student accepted to UC Berkeley and USC

Inspired by a college business case competition, this student focused his senior project on creating a business competition for high school students. He invited students from 8 local high schools and had 500 participants. He also arranged judges from a widely-known bank and a university. To leave a lasting impact, he created an executive board within his high school so this event will continue after he graduates.

Social & Political Sciences

Student accepted to harvard.

This student created a 501(c)(3) nonprofit for equitable public speaking resources. They also held a public speaking-themed summer camp for 70+ students and raised $2,000 for a local speech center.

Student accepted to Yale

Impact: Statewide

This student coalesced over 15 assault prevention organizations to develop two bills for the 2023 Oregon legislative session. Their effort instituted a $20 million education grant program and youth network.

Medicine & Healthcare

Student accepted to brown.

Impact: National

This student produced and edited 140+ mental health articles to uplift youth. The articles got over 12,000 reads. The student also hosted a podcast interviewing women leaders with over 40 episodes.

Student accepted to Carnegie Mellon

Impact: Local and National

This student built a COVID outbreak detection platform with ML. It got over 10,000 views. They also prototyped a compact translation tool with Michigan hospitals for non-native English speakers.

This student designed a chemotherapy symptom-tracking app to improve treatment. They then pitched it to industry experts and won Best Elevator Pitch of over 70 teams.

Student accepted to Cornell and Johns Hopkins

This student knew she wanted to major in biomedical engineering. She created a children’s medical book series called “My Little Doctor” to teach young kids how to address emergencies, wounds, and household medications. The books included personal illustrations, which also showcased her artistic talent. The books were sold by 150 doctor’s offices throughout NYC.

Math & Computer Science

Student accepted to columbia.

This student programmed AI to patrol an endangered turtle nesting site using drones. They partnered with a resort, launched an open source platform, and expanded the project internationally.

Student accepted to Dartmouth

This student worked on the solidity development of crypto currencies, NFTs, DAOs, DApps. They were responsible for project, client, and social media management. They also supervised 3 employees.

This student created a virtual musical theater camp for kids ages 6-12 during the COVID-19 pandemic. They managed the camp’s Instagram, website, and Facebook. They taught 25 kids and produced 5 shows.

Student accepted to Harvard and Brown

This student founded an organization to make music education accessible. It included a lead team of 35 members. It grew to 9 branches in 7 countries, impacted 15,000 students online, taught 1.6k lessons, and saved parents $40K. It raises $10k annually. This student was a TD Scholarship Finalist, YODA, and SHAD Fellow.

What are the criteria for a successful senior project?

If you only take away one thing from this article, let it be this: The best senior projects are personal to you and have a measurable impact. When you are contemplating a senior project idea, ask yourself:

- “Am I interested in this topic?” As in, interested enough to spend the next year thinking a LOT about it.

- “Can I show a measurable impact with this project, preferably at the local, national, or international level?”

Let’s use tutoring as an example. Tons of students include tutoring on their applications as one of their extracurriculars. Does tutoring pass the test if we ask our two questions?

- Am I interested in the topic? If you’re tutoring in a subject you love, the answer could be a yes.

- “Can I show a measurable impact with this project?” This one is tricky. Of course, tutoring one or even a few students makes an impact on the lives of those students. But is the impact local, national, or international? Not exactly.

So instead of tutoring a few students on your own, maybe you can create a tutoring club with 30 tutors supporting 100 students at your school. If you want to expand your impact, you can bring your tutoring services into an elementary school or into other schools in your community. You can even create a charter and get your tutoring club into high schools throughout the country, world, or online.

By thinking bigger, you can turn most conventional extracurricular ideas into an impactful, standout senior project idea.

How to Choose a Topic for Your Senior Project

I’ve helped hundreds of students develop successful senior projects. This is the process we use:

- Make a list of your major interests. These could be academics, hobbies, anything!

- Now write down problems or areas of exploration that relate to those interests.

- Narrow down your choices to one or two that are academically relevant, relevant to your interests and goals, interesting enough for you to explore, and have enough published data.

- Identify a problem that you can address in this area with a solution that you identify. This will be the subject of your senior project!

Let’s walk through these steps using a hypothetical student as an example.

Senior Project Topic Brainstorm Example

- List interests.

Maya is a junior with dreams of attending an Ivy League school. She's always been fascinated by environmental science, particularly renewable energy sources. She also enjoys coding and app development. Outside of academics, Maya volunteers at a local animal shelter and is an avid runner.

- List problems or areas of exploration related to those interests.

For environmental science, Maya is concerned about the inefficiency of current solar panels in low-light conditions.

In coding, she notes the lack of user-friendly apps that promote environmental awareness among teens.

Her volunteering experiences make her wonder how technology can assist animal shelters in improving animal adoption rates.

- Narrow down the choices.

After considering her list, Maya decides to focus on environmental science and coding, as these are her academic interests and she sees herself pursuing them in the future. She finds the intersection of these fields particularly interesting and ripe for exploration. Plus, she discovers ample published data on renewable energy technologies and app development, confirming the feasibility of her project idea.

4. Identify a Problem and Solution

Maya identifies a specific problem: the gap in environmental awareness among her peers and the lack of engaging tools to educate and encourage sustainable practices. She decides to address this by developing a mobile app that gamifies environmental education and sustainability practices, targeting high school students.

Senior Project: EcoChallenge App Development

Maya's senior project, the "EcoChallenge" app, aims to make learning about environmental science fun and actionable. The app includes quizzes on environmental topics, challenges to reduce carbon footprints, and a feature to track and share progress on social media, encouraging collective action among users.

Project Execution

Over the course of her junior year, Maya dedicates herself to researching environmental science principles, studying app development, and designing an engaging user interface. She reaches out to her environmental science teacher and a local app developer for mentorship, receiving valuable feedback to refine her project.

Outcome and Impact

Maya presents her completed app at her school's science fair, receiving accolades for its innovation, educational value, and potential to make a real-world impact. She submits the EcoChallenge app as a central piece of her college applications, including a detailed report on her research, development process, and user feedback.

The Bottom Line

Your senior project can be one of the most important pieces of your college application. It can also make a difference in the world.

As you shape your senior project, see how many of these elements you can apply to it:

- Makes measurable impact. What does success look like, and how will you measure it?

- Presents an innovative solution to an existing issue. Is this solving a problem?

- Is oriented to the community. Is this making my community/country/the world a better place?

- Is interdisciplinary. Can I blend more than one of my interests? Can I get professionals from other fields to collaborate on this project?

- Is related to your field of study. Will this make my academic interests clear?

Basically, think about something you care about. Take it beyond something standard and ask, “What can I do that would allow me to help my community and leave a greater impact?”

Even after reading all these examples, I know that choosing an idea for your own senior project can be tough. If you need help choosing and executing a standout senior project, book a free consultation with one of our academic advisers. Crimson’s extracurricular mentors can help you combine your interests into an impactful senior project that makes you stand out to top college admissions officers.

Building The Perfect Application

Passion projects and extracurriculars are just one piece of the puzzle. It could be difficult to navigate the ins and outs of the college admission process, but you don’t have to go through it alone.

Working with an expert strategist is a surefire way to perfect your application. Students working with our strategists are 7x more likely to gain admission into their dream university.

What Makes Crimson Different

More Articles

Diving into robotics: an epic extracurricular for stem success.

/f/64062/800x450/5233567014/robotics-team-extracurriculars.jpg)

How to Show Intellectual Curiosity on Your Top College Application

/f/64062/800x450/e67c57a473/library.jpg)

Research, Publish, Apply! Charting a Path from Publication to College with Indigo Mentorships

/f/64062/400x267/ce0a8ba1ef/get-your-paper-written-by-a-professional-essay_802.jpg)

Let your passion project be your ticket to a top university!

Crimson students are up to 4x more likely to gain admission into top universities book a free consultation to learn more about how we can help you get there.

- Success Stories

- AI Scholar Program

- Startup Internship Program

- Research Scholar Program

- GOALS Academic Support Program

- Test Prep Program

- Passion Project Program

- For Families

- For Schools

- For Employers

- Partnerships

- Content Guides

- News And Awards

- College Admissions

- Events and Webinars

- Grade Levels

- High School

Best Senior Project Ideas

Gelyna Price

Head of programs and lead admissions expert, table of contents, what is a senior project, exactly, the benefits of completing senior projects, types of senior projects, the best senior project ideas, how to choose your senior project, senior projects can be important.

Stay up-to-date on the latest research and college admissions trends with our blog team.

The senior project has almost become a rite of passage many students have anticipated for several years. The long-awaited experience can make many seniors nervous because they may suddenly realize that they aren’t sure what to do for their project!

It’s easy to get so caught up in finding the best senior project ideas that time flies, and seniors get into a time crunch. However, many incredible ideas for the best senior projects are just waiting to be chosen.

Senior projects are meant to be long-term projects that allow high school students to step outside of what their high school classes teach. They can express themselves by exploring something that ignites their passion. These projects can help students develop several types of skills, including:

- Research

- Writing

- Presentation and speaking

- Problem-solving

- Time management

While these projects can take endless versions and forms, they generally involve some combination of research and presentations.

Hundreds of different types of projects can qualify as senior projects. They can include months of research, the students’ special talents, passionate service to their home communities, or hands-on activities.

They could be hefty science projects or light-hearted illustration collections. They can be novels written by the senior over a long period of time or in-depth presentations after months of research on something near and dear to the senior.

The best senior projects are culminating experiences for students. They are opportunities for seniors to take the knowledge and skills they have honed throughout their academic careers and apply them to real-world issues, interests, problems, or passions. Completing senior projects offers several benefits.

They can help students explore their interests as they prepare to enter college or begin their careers after high school.

How Are Senior Projects Good for College Application Resumes?

Are senior projects good for college application resumes? Yes! When you work on your senior project, you can use the project to practice skills you’ll use in college or your career.

Some of those skills are meeting deadlines, managing your time, working independently, and practicing diligence and self-discipline. Your senior project can also be an excellent way to pad your college applications .

You Can Learn New Skills

In addition to allowing you to hone your current skills, your senior project can encourage you to learn new skills. Senior projects are awesome opportunities for learning skills that will be valuable in college and beyond, especially with researching, writing, presenting your project, or learning to use new software.

You Can Explore Interests

You may have known for years what your senior project will entail, or maybe it’s now down to the wire, and you still have no clue where to begin narrowing down your options.

Either way, now is the time to explore your interests and learn more about what you’re curious about, what’s relative to your future career, or what you have never heard of before!

It’s a Chance to Learn from Experts

Whether you research at the library or conduct interviews with historical figures (or anything in between), you’ll have the opportunity to learn from experts in your project’s subject.

Give Back and Get Involved

The best senior projects are often excellent vehicles for students to engage with their communities. Many seniors choose projects that address an issue that is important to them and that are local, directly impacting their hometowns. For that reason, a senior project can allow you to make a difference in your community.

There are four basic types of senior projects, including:

- Presentation projects

- Creative writing projects

- Professional career projects

- Service-related projects

While each category has some unique features, they all offer the same general benefits to seniors.

Presentation Projects

These projects are very popular with seniors because the category is quite broad. Presentation projects include creating something visual to teach the audience the subject of the project. This can include science project results on a poster board, a musical performance, showcasing artwork, singing, or acting in a play.

Creative Writing Projects

Creative writing senior projects involve material and information communicated through the written word. They can incorporate play scripts, essays, short tales, poems, or something similar.

Students can study, research, and write either fiction or non-fiction pieces, making creative writing senior projects almost limitless in scope. You might consider a creative writing project if you are passionate about language.

Professional Career Projects

Some students choose to do a senior project that incorporates job shadowing or working as an assistant in a field they enjoy as part of experiential learning. Whether they choose a medical career, law enforcement, or anything else, they craft a report or presentation on what they learned.

Service-Related Projects

Students who are involved or want to get involved in their communities might choose service-related senior projects. These involve planning or participating in anything from setting up a clothing drive for the homeless or a toy drive at Christmas to volunteering at the local rehabilitation center or nursing home.

Some of the best senior projects are unique, personal, and in-depth. Yours should be worked on over several weeks or months.

Consider the list below if you’re looking for a unique senior project idea that hasn’t been done every year for the last 30 years. Some excellent unique senior project ideas include:

- Developing a new software application

- Working with a reporter or photographer to learn about journalism

- Writing a paper on a technological topic

- Tutoring students

- Volunteering at a veterinarian’s office or animal shelter

- Organizing a fundraising event for a cause you’re passionate about

- Starting a social enterprise or business

- Writing a biography or autobiography

- Designing and building a machine or robot

- Creating a painting, piece of music, or other work of art

- Creating a blog or website about a passion of yours

- Leading a workshop

- Teaching a class

- Participating in an internship

- Conducting market research on a service or project

- Organizing a community cleanup

- Researching a historical event or person

- Organizing a debate

- Organizing a party for autistic children who find other parties too overwhelming

- Working with a paramedic and learning about lifesaving procedures

- Volunteering for a social service organization

- Organizing a STEM event, such as a science fair

- Volunteering at a local museum

- Writing op-eds for your local newspaper

- Starting a painting class for kids

- Making a documentary about local history

- Putting on a play you wrote

- Building a go-kart

- Working with a real estate agent

- Doing a mock courtroom project

- Simulating the experience of the U.S. House or Senate

- Teaching a foreign language to residents in a senior home

- Developing a solution for a community-wide health problem

- Teaching English as a second language

- Building a little free library box in your neighborhood

- Working to change a school policy that needs changing

- Organizing volunteers to tutor students

- Helping a local business with their record-keeping or accounting

- Creating a community garden

- Working in a professor’s lab

- Working as a chef and improving your culinary skills

- Working with the cafeteria to reduce food waste and make other changes

- Devising a plan to build community bike trails

- Working to create a space as a dog park

- Volunteering to coach a kid’s athletic team

- Organizing a group to pick up groceries and medications for those who can’t

- Setting up a community ride service

- Volunteering at a homeless shelter, soup kitchen, or non-profit organization

- Volunteering to take an older adult to church

- Gathering a group to make or collect toys for children at Christmas time

Any of the above ideas should be documented and then shaped into a presentation. While the first part of a senior project is doing the activity, the second part is sharing your experience with others via a presentation.

Your senior project should take considerable time and effort to complete, so above all else, you want to ensure that it relates to something you’re passionate about. This will make the entire experience more enjoyable and meaningful.

Remember to ask how are senior projects good for college application resumes and choose a project that will enhance your application.

Choose a feasible topic; it should be something you can complete with the skills, time, and resources available. The topic should be challenging but attainable. The goal is to push you out of the “same old same old,” but you don’t want something so complex that you can’t finish it.

Get started early in the year by brainstorming senior project ideas , researching, and planning. Ensure you understand what you’re required to do as part of your project, and don’t hesitate to reach out for help if you need it.

It can be helpful to break your project into smaller sections and tasks throughout the year, and setting deadlines for yourself can help you stay on track and avoid having too much to do later in the year.

Deciding on a senior project should be an exciting task! It’s a time to hone your skills, learn new ones, and explore your interests. By following the above tips and considering your interests and passions, you will surely find a rewarding senior project.

Here are a few ideas for your high school senior project.

- Research a Global Issue: Select a global issue that you are passionate about, such as climate change, poverty, or gender equality, and conduct in-depth research on the topic. Create a comprehensive report or multimedia presentation that highlights the causes, impacts, and potential solutions to the issue. Consider organizing a community event or awareness campaign to engage others in the cause.

- Entrepreneurship Project: Put your entrepreneurial spirit to the test by starting your own small business or social enterprise. Identify a product or service that fills a gap in the market or addresses a specific need in your community. Develop a business plan, create marketing materials, and track your progress throughout the project. This hands-on experience will allow you to develop valuable skills in entrepreneurship and problem-solving.

- Artistic Showcase: If you have a talent in the arts, consider creating an artistic showcase as your senior project. This can involve curating an art exhibition, organizing a concert, or directing a theater production. Use your creative skills to bring together a collection of works or performances that reflect your artistic vision and captivate your audience.