Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Uncategorized › Roland Barthes’ Concept of Mythologies

Roland Barthes’ Concept of Mythologies

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on March 21, 2016 • ( 1 )

Differing from the Saussurean view that the connection between the signifier and signified is arbitrary, Barthes argued that this connection, which is an act of signification, is the result of collective contract, and over a period of time, the connection becomes naturalised. In Mythologies (1957) Barthes undertook an ideological critique of various products of mass bourgeoise culture such as soap, advertisement, images of Rome, in an attempt to discover the “universal” nature behind this. Barthes considers myth as a mode of signification, a language that takes over reality. The structure of myth repeats the tridimensional pattern, in that myth is a second order signifying system with the sign of the first order signifying system as its signifier.

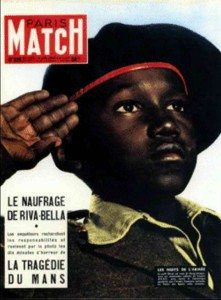

Barthes illustrates the working of myth with the image of a young negro soldier saluting the French flag, that appeared on the cover of a Parisian magazine — where the denotation is that the French are militaristic, and the second order signification being that France is a great empire, and all her sons, irrespective of colour discrimination faithfully serve under her flag, and that all allegations of colonialism are false. Thus denotations serve the purpose of ideology, in naturalising all forms of oppression into what people think of as “common sense”. The most significant aspect of Barthes’ account of myth is his equation of the process of myth making with the process of bourgeoise ideologies.

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Linguistics , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , mythologies , Roland Barthes , s/z

Related Articles

- Roland Barthes as a Cultural Theorist – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Myth

I. What is Myth?

A myth is a classic or legendary story that usually focuses on a particular hero or event, and explains mysteries of nature, existence, or the universe with no true basis in fact. Myths exist in every culture; but the most well known in Western culture and literature are part of Greek and Roman mythology. The characters in myths—usually gods, goddesses, warriors, and heroes—are often responsible for the creation and maintenance of elements of nature, as well as physical, emotional, and practical aspects of human existence—for example Zeus; the god of the sky and the earth and father of gods and men, and Aphrodite; the goddess of love and fertility. A culture’s collective myths make up its mythology , a term that predates the word “myth” by centuries. The term myth stems from the ancient Greek muthos , meaning a speech, account, rumor, story, fable, etc. The terms myth and mythology as we understand them today arose in the English language in the 18 th century.

II. Example of Myth

Many stories include an element of a popular myth in a new way. Read the following example:

The dog was strong and fearless, and you could tell by the way he sat that he was a proud pooch. His bravery was famous amongst dogs and other creatures far and wide; the stories of his deeds were known by young pups and old mutts alike. His owners had named him Hercules, after the great hero of legend, and he had lived up to his namesake.

This short passage employs the classic Herculean myth to the story of dog. The hero Hercules was known for his superhuman strength and abilities as a warrior, but also for his pride. Here, a dog named Hercules is described as having similar traits and abilities as the Hercules of Greek myth.

III. Types of Myths

Myths are generally classified by cultural origin, and together those myths comprise a culture’s mythology . The most important mythologies in western culture are those of Rome and Greece , as mentioned above, which are generally collectively known as Classical Mythology. It is believed that both were developed from the beliefs of popular life at the time they were created.

The Greek Myths

The Greek myths are a collection of myths developed by the ancient Greeks. They were developed long before the Roman, with evidence of their existence dating back as far as 2000BC. The myths concern topics such as the origins of human practices and rituals, the laws of nature, gods and heroes, and so on. Many myths explain the origin of the universe and the creation of man. The Greek myths also have a pantheon of gods and goddesses who rule and order the universe, the most notable being the Olympians, the gods and goddesses who reside under Zeus on Mount Olympus. The most widely used elements of myth in fiction are from Greek mythology, particularly its gods and goddesses.

The Roman Myths

The Roman myths are a collection of myths about the origins and development of ancient Rome; of which the stories primarily pertain to order of Roman society, rather than the order of the universe. It is believed the Romans thought of them as true historical accounts, despite the fact that they included supernatural and mystical elements. They are also religious in nature, and use divine law to explain issues of politics and morality. Like the Greek myths, they have pantheon of gods and goddesses, most of which are named from the stars and planets. However, the gods have a much smaller role in Roman mythology and religion than in the Greek. Unlike the Greek myths, the Roman myths do not have a creation story about the origin of the universe.

IV. Importance of Myth

The importance of myth is immeasurable—in literature, philosophy, history and many other parts of human life. They have been a huge part of oral, written, and visual story telling for literally thousands of years; in fact, they have been a part of mankind’s entire history. Humans have always used myths to explain natural phenomena and life’s mysteries; for instance, Greek and Roman mythology served as both science and religion in both cultures for centuries. To this day myths have a very large and relevant place in cultural studies and scholarship, and are represented across studies in literature, religion, philosophy, and many other disciplines. Part of the allure of myths is that the exact process and purpose of their development is unclear. For instance, some scholars believe that myths are inaccurate accounts of real historical events, while others argue that the gods and goddesses were personifications of objects and things in nature that ancient men worshiped.

V. Examples of Myth in Literature

Most myths have been passed through oral tradition, and were later written down by scholars and historians—there are no original written collections of Greek mythology, they were not recorded until centuries after they were first believed to be developed. One of the most well respected collections of retellings of Greek and Roman myths is The Greek Myths by Robert Graves. In the selection below, Graves dictates the myth about the creation of Mount Olympus, where the gods and goddesses reside and rule.

Graves’s purpose is to record and retell the classic Greek myths in the most original and accurate form possible. Scholars of mythology see the dozens of myths that he covers in his collection as some of the most accurate and well-developed representations of these ancient tales.

The most important representations of mythology in literature are found in Homer’s The Iliad ; which follows the king and warrior Odysseus through the Trojan War, and The Odyssey , which follows his journey home and his many encounters with mythological gods and creatures. The passage below describes Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom:

This said, her golden sandals to her feet She bound, ambrosial, which o’er all the earth And o’er the moist flood waft her fleet as air, Then, seizing her strong spear pointed with brass, In length and bulk, and weight a matchless beam, With which the Jove-born Goddess levels ranks Of Heroes, against whom her anger burns, From the Olympian summit down she flew, And on the threshold of Ulysses’ hall In Ithaca, and within his vestibule Apparent stood; there, grasping her bright spear[.]

Here, the goddess Minerva flies down from mythological Mount Olympus to the hall where the hero Ulysses rules. As can be seen, Homer draws from both Greek and Roman mythology in the development of both epics.

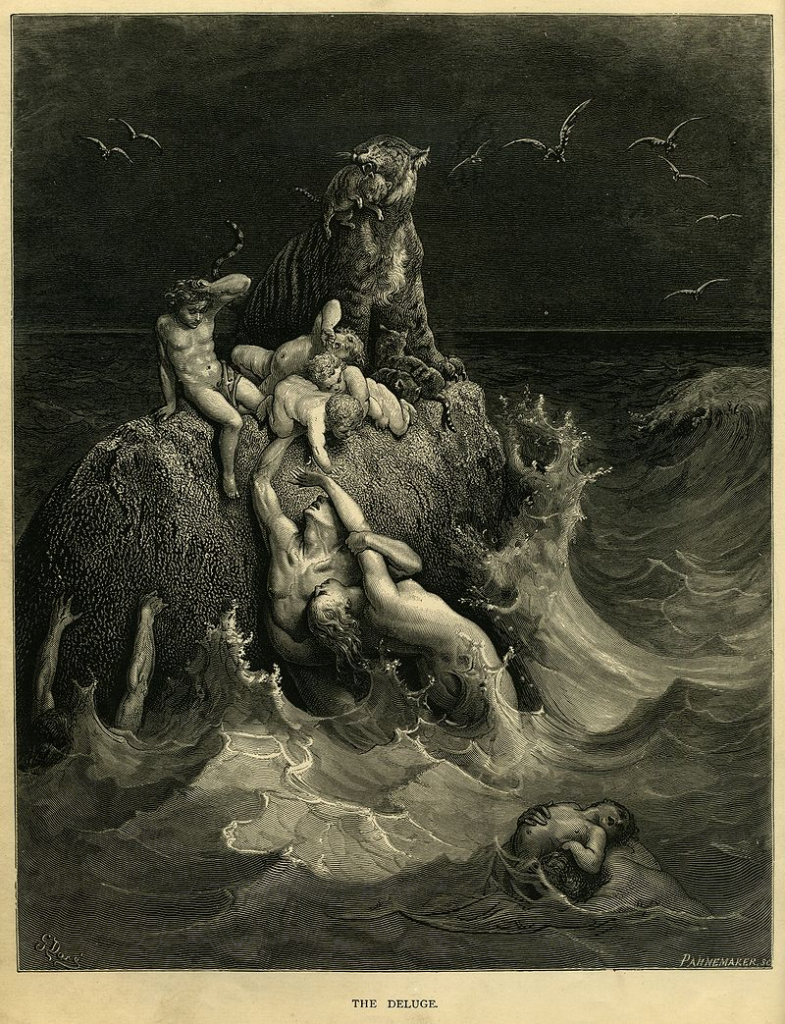

There are several noteworthy myths whose themes have been retold in varied ways across many cultures, predominantly the “creation myth” and the “flood myth,” which are popularly retold within the context of religion. A creation myth explains the creation of man, the universe, or some other element of life. A flood myth usually depicts a great flood sent by the gods to essentially destroy mankind, often as a form of punishment for forgetting the power and importance of divine rule. For example, the biblical story of Noah’s ark is a representation of the flood myth in Christianity, which is depicted below in a painting by Gustave Doré. Furthermore, most religions have a form of creation myth to explain the existence the universe and mankind.

VI. Examples Myth in Pop Culture

The blockbuster film Troy is about the mythological heroes of Trojan War. Actor Brad Pitt plays the great Greek warrior and hero Achilles, who sails with the Spartan army for their attack on the city of Troy. In the clip below, he contemplates his part in the war with his mother Thetis; the goddess of water:

![type of speech myth Troy - Achilles and His Mother Thetis [1080p Blu-Ray] ᴴᴰ](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/NPezYaC_viE/0.jpg)

In this scene, Achilles is ultimately deciding his fate. He knows that if he goes to war he will never return; he also knows he has a significant part to play in it because he is a legendary warrior. For Achilles to fulfill his destiny he must die, and while he may be a hero with some superhuman qualities and godlike fighting abilities, he is ultimately a mortal man.

The Walt Disney Corporation is famous for retelling and adapting well known myths, legends , and fairy tales into family movies. For instance, the animated Disney film Hercules retells the ancient Greek myth of the hero Hercules (mentioned above) in a way that families can enjoy:

Adaptations like these are valuable form for the retelling of myths. Films like Disney classics let children enjoy bright and appealing stories about age-old characters and themes. By presenting the stories in a way that is popular and relevant, children are encouraged to learn about classics. While an animated Disney film is certainly not a completely accurate depiction of the myth of Hercules, it still introduces children to a classic story that is an important part of literary culture.

VII. Related Terms

Folktales are classic stories that have been passed down throughout a cultures oral and written tradition. They usually involve some elements of fantasy and explore popular questions of morality and right and wrong, oftentimes with a lesson to be learned at the end. The difference between folktales and myths is that myths once served as a culture’s belief system, while folktales are fundamentally a form of storytelling.

An epic is a legendary tale about a great hero on quest, usually with some form of divine intervention. Most epic tales employ some form of mythology in their storylines, but epics are not myths in themselves .

VIII. Conclusion

In conclusion, myths are legendary stories that have been a fundamental part of man’s culture, history, and even religion for thousands of years. They have been utilized, adapted, and retold by authors since the beginning of storytelling—in other words, for the majority of human existence.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Definition of Myth

Myth is a legendary or a traditional story that usually concerns an event or a hero , with or without using factual or real explanations. These particularly concern demigods or deities, and describes some rites, practices, and natural phenomenon. Typically, a myth involves historical events and supernatural beings. There are many types of myths, such as classic myths, religious myths, and modern myths.

Characteristics of Myth

Myth usually features ruling gods, goddesses, deities, and heroes having god-like-qualities, but status lower than gods. Often, the daughter or son of a god (such as Percy Jackson) is fully mortal, and these characters have supernatural abilities and powers that raise them above average human beings.

Myths are mostly very old, and happen to have ruled the world when science, philosophy, and technology were not very precise, as they are today. Therefore, people were unaware of certain questions, like why the sky is blue, or why night is dark, or what are the causes of earthquakes. Thus, it was myths that explained natural phenomena, and described rituals and ceremonies to the people.

Examples of Myth in Literature

Example #1: romeo and juliet (by william shakespeare).

Roman and Greek myths, though originally not available in English, have deeply influenced English works. During the times of the ancient Greeks, they had a belief that some invisible gods, such as Zeus, had created this world. We read in such Greek stories that passions for humans controlled the gods, and hence gods fought for them. Likewise, Romans had beliefs in such deities.

Due to mythological influences, many literary authors refer to the Greek and Roman myths in order to add meanings to their works. For instance, Shakespeare, in his play Romeo and Juliet , uses Greek mythology when Juliet cries out saying that,

“ Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds , Towards Phoebus’ lodging.”

In Greek mythology, Phoebus was god of the sun, and here Juliet urges that god to bring him home quickly, so that night could come, and she may meet her lover Romeo.

Example #2: No Second Troy (By William Butler Yeats)

In another Greek myth, Greeks devastated the city of Troy in an outburst of the Trojan War, when Helen – the wife of king Menelaus – ran away with the prince of Troy. Apparently, Helen was a very beautiful woman from Greece, and was ultimately held responsible for the devastation of Troy.

Yeats also tried to use this Greek mythology in his poem , No Second Troy , by creating a similarity between Helen and Maud Gonne. He also brought a similarity between the Trojan War and revolutionary and anti-British activities of the Irish. Just like Helen, Yeats blamed and held Maud responsible for creating hatred in the hearts of Irishmen, and consequently they caused destruction and bloodshed.

Example #3: Paradise Lost (By John Milton)

Biblical stories and myths have also played an important role in shaping English literary works. John Milton , in his poem Paradise Lost , plays out the Genesis story about the Fall of Man, and subsequent eviction, from the Garden of Eden.

Both John Steinbeck and William Golding , in their respective novels , East of Eden , and Lord of the Flies , played on the same idea in which they have presented Eve as a seducer responsible for bringing sin into this world. We can clearly see this allusion in medieval literature. We also have seen that many feminist literary critics of the twentieth century have made use of this myth in their research.

Example #4: The Waste Land (By T. S. Eliot)

T. S. Eliot uses two underlying myths to develop the structure of his long poem The Waste Land . These myths are of the Grail Quest and the Fisher King, both of which originate from Gaelic traditions, and come to the Christian civilization. Though Eliot has not taken these myths from the Bible, both were significant for Europeans, as they incorporated them into European mythology, and these stories focused on the account of the death and resurrection of Christ.

Function of Myth

Myths exist in every society, as they are basic elements of human culture. The main function of myths is to teach moral lessons and explain historical events. Authors of great literary works have often taken their stories and themes from myths. Myths and their mythical symbols lead to creativity in literary works. We can understand a culture more deeply, and in a much better way, by knowing and appreciating its stories, dreams , and myths. Myths came before religions, and all religious stories are, in fact, retellings of global mythical themes. Besides literature, myths also play a great role in science, psychology, and philosophy.

Post navigation

Roland Barthes: Mythologies

by Jeanne Willette | Nov 29, 2013 | Theory

ROLAND BARTHES (1915-1980)

Mythologies (1957)

In the fifties, Roland Barthes was a semiologist, following Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) and Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009), in using the sign, the signifier and the signified to study the social condition. The timing of this volume is an interesting one, coming after the deprivations of a long war and occupation and during the decade in which France tried to recapture its pre-war prestige before surrender and humiliation. The nation was entering into the delirium of consumerism and mass media that was the common property of a European culture, rapidly becoming Americanized. The period was also one of nationalism with the country being still mired in the throes of late-Empire, struggling with what would be a long and depressing decade of colonialist chaos. Mythologies, like its content is also part the longer turn towards Structuralism, still in development, and owes much to Lévi-Strauss whose groundbreaking works taught Barthes how to look at cultural forms and analyze them. It is no accident that the foundational article, or the afterword of the book, is entitled “Myth Today,” which discusses contemporary mythology.

In Mythologies, written in 1957 from a compilation of fifty-three short articles published between 1954-56, Barthes became concerned with mass culture and the messages it sends to the hapless watchers of television and readers of magazines. By examining popular culture, Barthes, an admirer of Bertold Brecht, was following in the footsteps of Brecht’s friend, Walter Benjamin. Like Benjamin before the Second World War, his colleague Theodor Adorno examined the ideology of the “culture industry” and revealed how the interests of the dominant classes were furthered through Hollywood films. At this time, however, the pioneering and preceding work of Benjamin and Adorno was not well known and the analyses of Barthes were some of the earliest and most accessible de-codings of contemporary myths. Make no mistake, “Myth Today” was an extremely political tract, a scathing indictment of French colonialism and racism that still resonates in the 21st century. As Marco Roth pointed out in his 2012 article in The New Yorker on the new edition of Mythologies, the essays lay out

..his frustrations with social and political landscape of France from 1954 to 1956: a time of increasing middle-class prosperity, coinciding with France’s struggle to hold onto its colonies in North Africa and Southeast Asia, and DeGaulle’s attempts to restore some kind of national pride in the aftermath of the Second World War. Most worryingly for Barthes, these were years that also saw the rise of an explicitly anti-intellectual, racist, and populist political party..

American readers would have not been familiar with the political background of the quarrel Barthes, a Marxist, had with nationalism and right wing politics and French imperialism but “Myth Today” entered into very controversial territory. Keeping in mind the association between Barthes and Jean-Paul Sartre, Sartre was associated with and connected to Francis Jeanson, a post-war “resistance” figure who started a network of opponents to colonialism in France. According to a 1991 article by Martin Evans, “French Resistance and the Algerian War,” the Jeanson networks were sympathetic to the National Liberation Front (FLN), the Algerian insurrectionists. Jeanson had published a book condemning French behavior in Algeria in 1955, spreading the resistance from Africa to France. As Evans wrote,

In 1954 there were 200,000 Algerians living in France. Of those 150,000 were working, the majority in the building or steel industries. Slowly but surely the FLN began to organise Algerians in France. It was Algerians in France that were to finance the war.In 1954, French Algeria was a society rigidly polarised along racial lines, economically, politically and culturally. On the one side there were one million French settlers; on the other nine million Algerians..During the Algerian war the resisters’ activity was seen as ‘abnormal’ behaviour, it marked them out as traitors, rebels, outsiders in the eyes of French society. And, despite the time that has elapsed, even now a large number of French people would be reluctant to endorse what they did. For the right they were traitors; for the established left they were irresponsible, adventurists. The Communist Party might have taken a clear position against the war but it never condoned illegal action..in siding with the FLN in such a way they crossed too many taboos. This means that their action has never been accepted within the dominant culture in the way that Second World War resistance was..

In uncovering this hidden corner of French history, the article by Evans highlights the extent to which Barthes was taking a transgressive position. In fact “Myth Today” goes on for a number of pages before Barthes introduces his major character, found on the cover of Paris Match :

..a young Negro officer is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolor..I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any color discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this Negro in serving his so-called oppressors.

This sudden tough political confrontation is all the more striking, given that the reader of the volume of essays had been browsing through short little narratives on bourgeois habits: the spectacle of wrestling, soap-powdrs, margarine, steak and chips and striptease. Barthes is the sarcastic observer of the absurdities of consumer culture but Mythologies is also a very serious attempt to use semiology as a science and the first half dozen pages of “Myth Today” carefully lay out the semiological structure of myths. Heavily influenced by the 1955 essay by Claude Lévi-Strauss “The Structural Study of Myth,” Barthes organized the structure of myth into a framework that brought its constituent parts together into an assemblage. It is the arrangement of the elements that give the meaning to the myth. Lévi-Strauss pointed out the myth was a third term between the implied times of langue and parole, because “myth is language.” Myth has a double structure, both historical and ahistorical. Of course from a political point of view, this very frozen state of a myth is exactly what gives it power: because it has always existed, it must be true or “natural.”

In an attempt to “denaturalize” received wisdom, which is the role of the critic, Barthes de-coded familiar myths and made them un-familiar by pointing out that “Mythical speech is made of a material which has already been worked on..because all materials of a myth..presuppose a signifying consciousness..” Given that the myth must be familiar, it is constructed, as Barthes instructed, “from a semiological chain which existed before it: sign, signifier, signified. As a “second-order semiological system,” myth is divided into the “language-object” or the raw semiotic materials used by the myth and the myth itself or the “metalanguage.” Therefore, the signifier has two points of view: meaning and form, while the signified is the concept or the correlation of meaning and form. In terms of signification, according to Barthes, signification had a “double function: it points and it notifies, it makes us understand something and it imposes it on us.”

“Myth is a type of speech” and Barthes gave a great deal of attention to the structure of the linguistics of the myth, which is a system of communication, a message. The mode of signification is the form of the myth which is not defined by the object of the message but only by the way or mode in which it utters the message. The mode of writing the myth is representation, that is, the use of material that has already been worked and is suitable for communication. Each myth has two levels of meaning: a primary message is conveyed, but when the main message is bracketed, a secondary message can be discerned. This secondary message reveals the workings of socio-economic structures that function to continue the oppression of the people who receive the messages and continue an ideological world view that keeps the ruling classes in power. As Barthes stated,

..When it becomes form, the meaning leaves it contingency behind; it empties itself, it becomes improvised, history evaporates, only the letter remains..the essential point in all this is that the form does not suppress the meaning, it only improvises it, it puts it at a distance, it holds it at one’s disposal..the meaning loses its value, but keeps its life, from which the form of the myth will draw its nourishment..

The myth works with raw materials, reduced to pure signifying functions so that the myth becomes a sum of signs. In fact the myth prefers to work with poor and incomplete images. The myth will naturalize the concept and will transform history into nature. The reader then consumes the myth innocently as a factual system. The myth is already a form of language that can reach out and corrupt everything as depoliticized speech, organizing the world without contradictions and establishing clarity. Barthes pointed out that the myth was emptied out and became pure form into which new and ideological contents could be poured. The significance of the dozens of essays Barthes wrote for Les Lettres nouvelles is that most of his topics are based on commercial images in mass advertising, making him a semiologist of images the same way Lévi-Strauss was the structuralist of human behavior. In crossing the techniques Lévi-Strauss used for his analysis of the myth of Oedipus with a Sassurean examination of ordinary photographs, Barthes uncovered the inner workings of the myths that shaped the mindset of fifties France.

To decode a myth is to expose a delusion, making a revolutionary of a literary critic who can point to the “science” of semiology. The myths that Barthes found floating throughout popular culture were not, at that time, taken seriously, but the role of wine in French society was as important as the role of Charles de Gaulle, for as Barthes wrote, wine was political: ..its production is deeply involved in French capitalism, whether it is that of he privae distillers or that of the big settlers in Algeria who impose on the Muslims, on the very land of which they have been dispossessed, a crop of which they have no need, while they lack even bread.. Indeed, the seemingly benign exhibition The Family of Man which had originated at the Museum of Modern Art, was curated by Edward Steichen, and renamed “The Great Family of Man” in France, flattens differences into a universal cycle of birth, life and death, mythologizing the “human condition.” Barthes pointed out that the exhibition, which was also much criticized in America, obliterated the historical facts of the “condition,” which for some was positive while for others was grindlingly negative. As Barthes explained in “Myth Today,”

..In passing from history to nature, myth acts economically: it abolishes the complexity of human acts, it gives them the simplicity of essences, it does away with all dialectics, with any going back beyond what is immediately visible, it organizes a world without contradictions because it is without depth, a world wide open and wallowing in the evident, it establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves..

For example, America is characterized by and characterizes itself on the myth of the “Wild West.” The history of the “wild west” with its plural cast of characters, cowboys, social misfits, sociopaths, whores, settlers, opportunists, victims, lawyers and schoolteachers and sheriffs and so on. What is conveniently forgotten or emptied out is the exploitation of Chinese laborers, the genocide of Native Americans, the savage struggles between the settler and the rancher, and the wholesale rape of the land. Thus, through forgetting or suppression of the facts, the truth or history is emptied out, leaving a hollow form. What is left is the myth of the Frontier. To the consumer of the myth, this image of America is linked to nature to make “America” seem inevitable and natural. We do not question this myth of America and when those who question the myth are called “unpatriotic,” we are hearing ideology at work.

Because as Barthes stated, “Myth is depoliticized speech” that is “political in its deeper meaning,” precisely because it talks about, for example, French colonialism or American imperialism, in to “purify” these events , “it gives them clarity.” This clarity which Barthes called “blissful” is what makes it so difficult to challenge myths: to call a depoliticized myth political is to risk being refuted, in turn, charged with being “political.” Barthes understood the dilemma and suggested that the best strategy was to “produce an artificial myth”..”why not rob a myth?” he asked. To read and receive a social myth is to be complicit in the making of the myth. The myth is always form, never content, and operates as a sign of the real or as a meta-language. Myths, he pointed out, exist on the left and right as political tools that tell cultural stories. Rather than study signs from an “objective” standpoint or from the position of “scientific” analysis, Barthes understood that signs are embedded, not just in a cultural context or a network of purely linguistic relationships, but belong to politics, economics, and ideology. Although he hinted at the notion of political critique in Writing Degree Zero , it is at this point with this essay that Barthes became a critic of culture or a critic of the workings of power and a revealer of the trappings of ideology.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]

Recent Posts

- Art Deco and Women

- Le Corbusier: Purism as the Ideal City

- Le Corbusier: The Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau

- The Soviet Pavilion 1925

- Constructivism and the Avant-Garde

The Three Types of Myths: Aetiological, Historical, and Psychological

There are actually many different types of myth, not just three. In fact, there are several entire theories of myth. The theoretical study of myth is very complex; many books have been written about theories of myth, and we could have an entire class just on theories of myth (without studying any of the myths themselves). The problem with theories of myth, however, is that they are not very good; they don’t do a great job of explaining the myths or helping us understand them. Furthermore, the myths themselves are much more interesting than the theories. For these reasons, this textbook will not say very much about the theories of myth. But we don’t want to ignore the theoretical study of myth entirely, so we will limit ourselves to discussing only three types of myth.

1. Aetiological Myths

Aetiological (sometimes spelled etiological) myths explain the reason why something is the way it is today. The word aetiological is from the Greek word aetion (αἴτιον), meaning “reason” or “explanation”. Please note that the reasons given in an aetiological myth are NOT the real (or scientific) reasons. They are explanations that have meaning for us as human beings. There are three subtypes of aetiological myths: natural, etymological, and religious.

A natural aetiological myth explains an aspect of nature. For example, you could explain lightning and thunder by saying that Zeus is angry.

An etymological aetiological myth explains the origin of a word. (Etymology is the study of word origins.) For example, you could explain the name of the goddess Aphrodite by saying that she was born in sea foam, since aphros is the Greek word for sea foam.

A religious aetiological myth explains the origin of a religious ritual. For example, you could explain the Greek religious ritual of the Eleusinian Mysteries by saying that they originated when the Greek goddess Demeter came down to the city of Eleusis and taught the people how to worship her.

All three of these explanations are not true: Zeus’ anger is not the correct explanation for lightning and thunder, Aphrodite’s name was not actually derived from the Greek word aphros , and Demeter did not establish her own religious rituals in the town of Eleusis. Rather, all of these explanations had meaning for the ancient Greeks, who told them in order to help themselves understand their world.

2. Historical Myths

Historical myths are told about a historical event, and they help keep the memory of that event alive. Ironically, in historical myths, the accuracy is lost but meaning is gained. The myths about the Trojan War, including the Iliad and the Odyssey , could be classified as historical myths. The Trojan War did occur, but the famous characters that we know from the Iliad and the Odyssey (Agamemnon, Achilles, Hector, etc.) probably did not exist.

3. Psychological Myths

Psychological myths try to explain why we feel and act the way we do. A psychological myth is different from an aetiological myth because a psychological myth does not try to explain one thing by way of something else (like explaining lightning and thunder with Zeus’ anger does). In a psychological myth, the emotion itself is seen as a divine force, coming from the outside, that can directly influence a person’s emotions. For example, the goddess Aphrodite is sometimes seen as the power of erotic love. When someone said or did something that they did not want to do, the ancient Greeks might have said that Aphrodite “made them” do it.

Mythology Unbound: An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology Copyright © by Jessica Mellenthin and Susan O. Shapiro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Barthes Mythologies MythToday

Related Papers

Journal of emerging technologies and innovative research

Rouble Brar

John Peradotto

Juan José Prat Ferrer

Myths in Crisis. The Crisis of Myth

Marcin Klik

The concept of literary myth, introduced into French literary studies by Pierre Albouy in 1969, has been in crisis ever since its birth. The attempts to define literary myth with reference to ethno-religious myth proved to be a failure. Extreme divergences in the understanding of literary myth make many contemporary literary scholars treat it as a kind of buzzword which can be applied in any case to refer to any research subject. Myth is often identified with archetype, theme or motif, which may result in misunderstandings. The author of this study tries to define the literary myth anew, as a “recurrent story”. The new definition, not involving the features and functions typically attributed to myth, may be the starting point for various studies and – in accordance with the author’s intention – may facilitate the dialogue between scholars studying literary myths who represent various critical trends.

In Folklore and Old Norse Mythology. Ed. Frog & Joonas Ahola. FF Communications 323. Helsinki: Kalevala Society. Pp. 161–212.

Jeffrey Goodman

Artifactualists hold that some abstracta are contingent entities, products of the intentional activities of people. A great many artifactualists are fictional creationists, asserting that fictonal characters are abstracta of this sort, but some, notably Kripke (1973), Salmon (1998, 2002), and Braun (2005), further embrace mythical creationism. They hold that certain entities that figure in false theories are likewise abstracta that are produced by our intentional activities. A paradigm example would be Vulcan, the planet proposed by Le Verrier to be the cause of perturbations in the orbit of Mercury. I here argue that one may not reasonably take the metaphysical route travelled by Kripke, Salmon, and Braun; even if one holds that fictional characters are artifacts, one ought not further hold that mythical objects are, too. Realism about mythical objects is best accommodated by a traditional, Platonic conception of abstracta.

Journal for The Theory of Social Behaviour

Myth has a convoluted etymological history in terms of its origins, meanings, and functions. Throughout this essay I explore the signification, structure, and essence of myth in terms of its source, force, form, object, and teleology derived from archaic ontology. Here I offer a theoretic typology of myth by engaging the work of contemporary scholar, Robert A. Segal, who places fine distinctions on criteria of explanation versus interpretation when theorizing about myth historically derived from methodologies employed in analytic philosophy and the philosophy of science. Through my analysis of an explanandum and an explanans, I argue that both interpretation and explanation are acts of explication that signify the ontological significance, truth, and psychic reality of myth in both individuals and social collectives. I conclude that, in essence, myth is a form of inner sense.

Angela Locatelli (ed.). La Conoscenza della Letteratura / The Knowledge of Literature.

Sibylle Baumbach

RELATED PAPERS

tugas kuliah

Devi Santi Fatmawati

Ralf Reiche

PARALELLUS Revista de Estudos de Religião - UNICAP

Emerson da Silva

Ecological Indicators

Christian Kerbiriou

SAINS AKUNTANSI DAN KEUANGAN

Agus Seswandi

Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem

João Gentil

Nagoya Mathematical Journal

Joseph Wehlen

Gilberto Yokomizo

Turkish Journal of Educational Studies

hatice kızılkaya

Jimena Alarcón

NTM International Journal of History and Ethics of Natural Sciences, Technology and Medicine

Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura

CAMILA MARIA OLIVEIRA

Lukáš Richterek

Alternatives to Laboratory Animals

Lars Wärngård

Ankulegi Gizarte Antropologia Aldizkaria Revista De Antropologia Social

Valentina Villarreal Valencia

Bangladesh Journal of Otorhinolaryngology

S.M Ahsanul Habib

Ejves Extra

Andre Van Rij

rtytrewer htytrer

The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

Carlos Del Fresno

Family Practice

Scientific Reports

Claude Ahouangninou

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology

Yousef El-Alawi

Environment Protection Engineering

Włodzimierz Tylus

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Common myths about speech problems in children

Speech Language Pathologist and Lecturer, Discipline of Speech Pathology, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Elise Baker works for The University of Sydney. She has received grant funding from the Australian Research Council, and the New South Wales Department of Education. She is affiliated with Speech Pathology Australia.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Speech problems in early childhood are common. One in four parents of Australian children are concerned about their 4- to 5-year-old child’s speech but two-thirds of these parents don’t act on their concern. Why? What might stop them from seeking expert advice from a speech pathologist?

Myth 1: Children grow out of speech problems (just look at Einstein!)

It is true that children’s speech development takes time. A young child does not pronounce words like “spaghetti” or “hospital” accurately the first time they say them. However, parents should not hold onto the idea that their child will grow out of speech problems just because Einstein turned out to be a genius.

Although there are anecdotes that Einstein’s parents were worried about his speech and language development, it has not been proven that Einstein had a learning disability or that he was late to talk. It is unhelpful for children struggling to develop clear communication skills to have parents reassure themselves to the point of inaction based on a false belief.

There is cause for concern when a 4-year-old child’s speech is difficult for other people to understand. If parents take the wait-and-see approach, they put their child at risk of experiencing persistent speech difficulties during the school years, an increased risk of slower progression with reading, writing and overall school achievement, bullying, poorer peer relationship, and less enjoyment of school compared with their same-age peers. The risks are greater when speech difficulties are accompanied by language learning difficulties.

Myth 2: Speech problems are caused by tongue-tie

Tongue-tie ( ankyloglossia ) exists when a person has a short lingual frenulum — the fold of mucous membrane that anchors or ties the mid-portion of the tongue to the base of the mouth. Prevalence ranges from 4% to 10%, with boys affected more than girls .

When severe, tongue-tie can decrease tongue mobility and impact breastfeeding. In a review of research on the effect of tongue-tie on breastfeeding and speech, there was no evidence to suggest a causative link between tongue-tie and speech problems.

Case reports suggest that tongue-tie may be a contributing factor for a small number of children who cannot produce the “l” or “th” speech sounds; however, for the vast majority of children with speech difficulties (including children who struggle with “l” and “th”), tongue-tie is not the cause of the problem.

It seems that the tongue-tie myth was started long ago by Aristotle when he suggested tongues that are slightly tied are linked to indistinct speech and lisping. This myth has perpetuated for millennia, leading to often unnecessary, unusual and bizarre practices for releasing the tongue.

Myth 3: Children who don’t speak clearly are lazy

This myth reflects a lack of understanding about the nature of speech problems in children and a lack of appreciation for the consequences of the problem. Consider the following example: 4-year-old Henry (pseudonym) says bus as “bus” but sun as “tun” and spoon as “poon”.

You might think that because Henry can produce the “s” sound in bus, he is being lazy when he doesn’t use “s” in sun and spoon. He’s not. Henry has the most common type of childhood speech difficulty — phonological disorder .

This difficulty exists when a child struggles to learn the grammar or rules about which speech sounds belong in the language they are learning and how those sounds combine to form words. When children begin to talk they make systematic rule-based changes to simplify their speech, so that complicated words are easier for them to process in their heads and say.

As adults we intuitively know many of these rules. For instance, “spaghetti” becomes “getti” because toddlers delete syllables in long words, and “look” becomes “wook” because toddlers replace difficult sounds with easier sounds. Phonological disorder exists when most of these simplifying rules do not disappear by around 4-years.

Given the repeated misunderstandings and frustration that children with speech difficulties face, it makes no sense to suggest that these children are lazy. The truth is, children like Henry have a phonological disorder that responds well to intervention by a speech pathologist.

Myth 4: Therapy for speech problems doesn’t work

With the right help from a speech pathologist at the right time, 3- and 4-year-old children with speech difficulties can develop clear speech and go on to have successful early reading and spelling experiences.

The myth that intervention does not work was sparked by the publication of a community-based study of speech therapy conducted in the United Kingdom, published in 2000. This study found little evidence for the effectiveness of speech and language therapy compared with watchful waiting, over a 12-month period. What is important to know about this study is that the children in the intervention group received on average just 6 hours of therapy over the 12 months. This was not enough.

It was akin to prescribing antibiotics and only offering a limited dose, rather than the prescribed dose. Research suggests that children, like Henry, can need 20 hours or more of therapy to improve their speech.

Findings from the recent Australian Senate inquiry into the prevalence of different types of speech, language and communication disorders and speech pathology services suggest that not all Australian children with speech difficulty are getting the right amount of help they need, at the right time.

The problem isn’t that interventions for speech problems don’t work. They do. The problem is that service and resource constraints can limit the amount of intervention that children receive.

If you are concerned about your child’s speech, don’t make decisions about your child’s future based on myths. Find out the facts and seek professional advice from a speech pathologist.

- Speech impairments

- Speech therapy

- Speech problems

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

COMMENTS

Barthes considers myth as a mode of signification, a language that takes over reality. The structure of myth repeats the tridimensional pattern, in that myth is a second order signifying system with the sign of the first order signifying system as its signifier. Myth is a type of speech defined more by its intention than its literal sense.

The term myth stems from the ancient Greek muthos, meaning a speech, account, rumor, story, fable, etc. The terms myth and mythology as we understand them today arose in the English language in the 18 th century. II. Example of Myth ... Types of Myths. Myths are generally classified by cultural origin, ...

Barthes' principal assertion that "myth is a type of speech," going back to the original meaning of the Greek "mythos" (word, speech, story). Myth is a "system of communication" or a "message," a "mode of signification." This means that everything can be myth, provided that it conveys some meaning or

Definition, Usage and a list of Myth Examples in common speech and literature. Myth is a legendary or a traditional story that usually concerns an event, or a hero, with or without using factual or real explanations ... Typically, a myth involves historical events and supernatural beings. There are many types of myths, such as classic myths ...

"Myth is a type of speech" and Barthes gave a great deal of attention to the structure of the linguistics of the myth, which is a system of communication, a message. The mode of signification is the form of the myth which is not defined by the object of the message but only by the way or mode in which it utters the message.

foundation, for myth is a type of speech chosen by history: it cannot possibly evolve from the 'nature' of things. and the intended contrast between mythical speech of the past and of the present is wholly demarked. The "mythical speech" of Barthes's essay is of a continuum with the "mythical speech" of PAGE - 2

"Myth is a language," he says, or a "type of speech" or "system of communication." It's a "message" and "a mode of signification, a form." Starting with some image or language that already has a meaning for us, we can use "mythical speech" to discuss it and convert it into myth.

"Myth Is a Type of Speech" Roland Barthes clarifies his definition of myth. Barthes's central claim is that history makes myths. Myths are meaningful only when they are examined from within their particular historical context. The overarching aim of Mythologies is to expose the myths that inform popular culture in France. Barthes elaborates on ...

Roland Barthes : Myth is a type of speech (109). Carl Gustav Jung: Myths are original revelations of the preconscious psyche, involuntary statements about unconscious psychic happen-ings, and anything but allegories of physical processes (154). Jane Ellen Harrison: The primary meaning of myth in religion is just the same as

India. Vāc is the Hindu goddess of speech, or "speech personified". As brahman "sacred utterance", she has a cosmological role as the "Mother of the Vedas ". She is presented as the consort of Prajapati, who is likewise presented as the origin of the Veda. [1] She became conflated with Sarasvati in later Hindu mythology.

It postulates myth as a type of speech, not just of any type but as communication or message. Speech is not restricted to an oral form; it can consist of modes of writing or of representations ...

These two words, mythos and logos, point to two different kinds of speech, corresponding to two different ways of thinking. One was not considered more important than the other; they were just different. If you put the two words together: mythos + logos = mythology. And "mythology" is the explanation or the analytical study of myths.

These two words, mythos and logos, point to two different kinds of speech, corresponding to two different ways of thinking. One was not considered more important than the other; they were just different. If you put the two words together: mythos + logos = mythology. And "mythology" is the explanation or the analytical study of myths.

Myth is a type of speech 109 Myth as a semiological system 111 The form and the concept 117 The signification 121. 5 Reading and deciphering myth 127 Myth as stolen language 131 The bourgeoisie as a joint-stock company 137 Myth is depoliticized speech 142 Myth on the Left 145 Myth on the Right 148 Necessity and limits of mythology 156 6

myth, a symbolic narrative, usually of unknown origin and at least partly traditional, that ostensibly relates actual events and that is especially associated with religious belief.It is distinguished from symbolic behaviour (cult, ritual) and symbolic places or objects (temples, icons). Myths are specific accounts of gods or superhuman beings involved in extraordinary events or circumstances ...

Mythologies (French: Mythologies, lit. 'Mythologies') is a 1957 book by Roland Barthes.It is a collection of essays first published from 1954 to 1956 in the French literary review Les Lettres nouvelles, examining the tendency of contemporary social value systems to create modern myths.Barthes also looks at the semiology of the process of myth creation, updating Ferdinand de Saussure's system ...

Mythology (from the Greek mythos for story-of-the-people, and logos for word or speech, so the spoken story of a people) is the study and interpretation of often sacred tales or fables of a culture known as myths or the collection of such stories which deal with various aspects of the human condition: good and evil; the meaning of suffering ...

For these reasons, this textbook will not say very much about the theories of myth. But we don't want to ignore the theoretical study of myth entirely, so we will limit ourselves to discussing only three types of myth. 1. Aetiological Myths. Aetiological (sometimes spelled etiological) myths explain the reason why something is the way it is ...

Myth as a semiological system For mythology, since it is the study of a type of speech, is but one fragment of this vast science of signs which Saussure postulated some forty years ago under the name of semiology. Semiology has not yet come into being.

There are three subtypes of aetiological myths: natural, etymological, and religious. A natural aetiological myth explains an aspect of nature. For example, you could explain lightning and thunder by saying that Zeus is angry. An etymological aetiological myth explains the origin of a word. (Etymology is the study of word origins.)

In Barthes' context myth does not refer to ancient myths. As Roland Barthes explains it, myth is a type of speech, a system of communication evoked to carry a message. Though it is not confined to written discourse, myth can take many forms including images, film, and sport. But that is not to say that these materials define myth, it is the way ...

Myth 3: Children who don't speak clearly are lazy. This myth reflects a lack of understanding about the nature of speech problems in children and a lack of appreciation for the consequences of ...

Myth Today, page 2 of 26 accepted as speech. This does not mean that one must treat mythical speech like language; myth in fact belongs to the province of a general science, coextensive with linguistics, which is semiology. Myth as a semiological system For mythology, since it is the study of a type of speech, is but one fragment of this vast ...