Causal Arguments

Sample causal argument.

Now that you have had the chance to learn about writing a causal argument, it’s time to see what one might look like. Linked, you’ll see a sample causal argument essay written following MLA formatting guidelines.

- Sample Causal Argument. Authored by : OWL Excelsior Writing Lab. Provided by : Excelsior College. Located at : http://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/argumentative-purposes/argumentative-purposes-sample-causal-argument/ . Project : ENG 101. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

14.2: Organizing the Causal Analysis Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4998

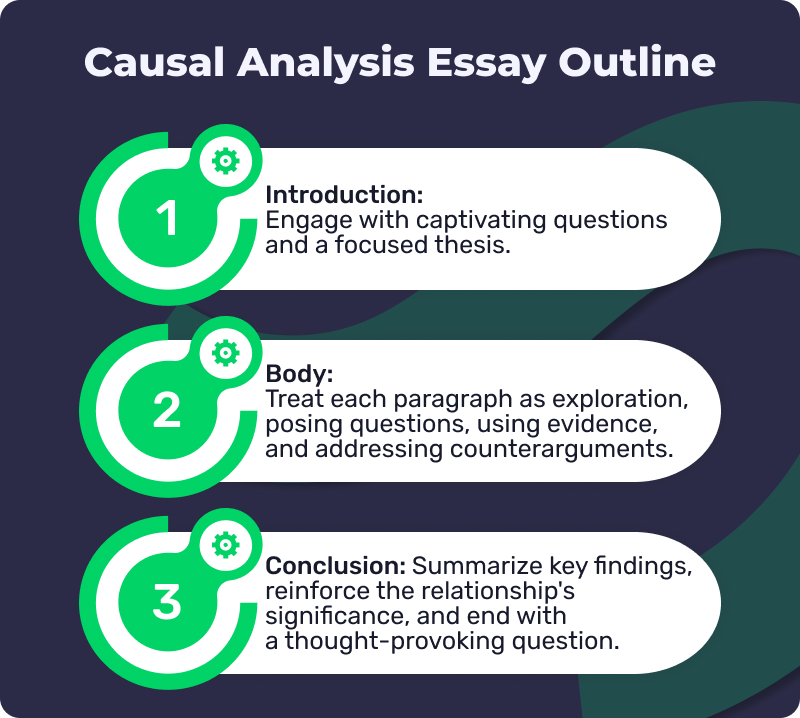

The causal analysis essay can be split into four basic sections: introduction, body, conclusion, and Works Cited page. There are three basic formats for writing a cause/effect:

- Single effect with multiple causes–air pollution is the effect, and students would identify several causes;

- Single cause with multiple effects–bullying is the cause, and students would establish several effects it has on children;

- Causal Chain–This is a more complex format. Causal chains show a series of causes and effects. For example, dust storms between Tucson and Phoenix can be deadly causing a chain reaction of accidents. The dust is the initial catalyst. It causes car A to stop. Car B crashes into Car A. Car C crashes into Car B., etc. Climate change is a good example of a causal chain topic. Population increase is causing an increase in traffic and greenhouse gases. It is also causing an increase in deforestation for housing, roads and farming. Deforestation means less plants to take up the CO2 and release O2 into the environment. Each item causes an effect. That effect causes another effect. All of this contributes to climate change.

Introduction

The introduction introduces the reader to the topic. We’ve all heard that first impressions are important. This is very true in writing as well. The goal is to engage the readers, hook them so they want to read on. One way is to write a narrative. Topics like bullying or divorce hit home. Beginning with a real case study highlights the issue for readers. This becomes an example that you can refer to throughout the paper. The final sentence in the introduction is usually the thesis statement.

Another way to introduce the topic is to ask a question or set of questions then provide background and context for the topic or issue. For example, if you are writing an essay about schizophrenia, opening questions might be “What are the main causes of schizophrenia? Who is susceptible?” The student would then begin a brief discussion defining schizophrenia and explaining its significance. Once again, the final sentence of the introduction would be a thesis statement introducing the main points that will be covered in the paper.

Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay is separated into paragraphs. Each paragraph covers a single cause or effect. For example, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, the two main causes of schizophrenia are genetic and environmental. Thus, if you were writing about the causes of schizophrenia, then you would have a body paragraph on genetic causes of schizophrenia and a body paragraph on the environmental causes. A second example is climate change where separate paragraphs explain each cause/effect relationship: population increases, increases in air pollution due to traffic exhaust and manufacturing, increases in food production and agriculture, deforestation. All are causes for climate change, and all are intricately linked.

A body paragraph should include the following:

- Topic sentence that identifies the topic for the paragraph,

- Several sentences that describes the causal relationship,

- Evidence from outside sources that corroborates your claim that the causal relationship exists,

- MLA formatted in-text citations indicating which source listed on the Works Cited page has provided the evidence,

- Quotation marks placed around any information taken verbatim (word for word) from the source,

- Summary sentence(s) that draws conclusions from the evidence,

- Remember: information from outside sources should be placed in the middle of the paragraph and not at the beginning or the end of the paragraph;

- Be sure and use transitions or bridge sentences between paragraphs.

- Draw final conclusions from the key points and evidence provided in the paper;

- Tie in the introduction. If you began with a story, draw final conclusions from that story;

- If you began with a question(s), refer back to the question(s) and be sure to provide the answer(s).

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Argument Essay Guidelines

Note to instructors: These guidelines provide possible choices for instructors assigning argument essays. They include options for proposal arguments, definition arguments, and causal arguments. You are encouraged to adopt, adapt, or remix these guidelines to suit your goals for your class.

Due Dates

- Rough Draft:

- Peer Review:

- Final Draft:

This assignment will help you learn to create an effective argument (i.e., convey your meaning persuasively) using evidence, sound reasoning, and awareness of rhetorical principles.

Skills: This assignment will help you practice skills essential to success in and beyond this course:

- Support claims effectively using varied forms of evidence.

- Analyze how style, audience, social context, and purpose shape your writing in electronic and print spaces.

Knowledge: This assignment will help you become familiar with the following important knowledge:

- Demonstrate an understanding of the rhetorical situation.

- Apply elements of rhetoric and argumentation in writing.

You may choose to write a proposal argument , a definition argument , or a causal argument . Directions for each type of argument are provided below. No matter what type of argument you choose to write, the following apply:

- Topic : Seek approval from your instructor on your topic before beginning this assignment. Audience: Select a primary audience who you think should care about your argument. Use appropriate language, organization, and examples to suit your audience. Note that your secondary audience is your classmates and instructor.

- Purpose and significance : The culprits or consequences shouldn't be so obvious that no argument is necessary. Consider the following questions as you establish the purpose and significance of your argument: Why is the argument important? Why is it controversial? What is at stake?

- Counterarguments : Take alternative viewpoints seriously. Your goal should be to choose the strongest support for your argument, but remember that real-world problems are rarely simple, so avoid taking an all-or-nothing position. Take opposing viewpoints into consideration and make concessions and offer counterarguments as appropriate.

- Research : If directed to incorporate research by your instructor, include information from at least three credible sources. Integrate source information effectively by using lead-in phrases; summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting as appropriate; and citing correctly, both within the body of your essay and on the Works Cited page.

- Length and format : Your essay should be 4–5 pages long, double-spaced.

Formatting requirements: Follow MLA format. Use black Calibri or Times New Roman font in size 12. Double-space the entire document. Use 1-inch margins on all sides.

Option 1: Proposal Argument

Write a practical proposal that in which you recommend a solution to a problem that you perceive in the world. Choose an important topic that matters to you and that you believe will matter to others; craft a proposal in which you argue for positive change.

In general, a proposal argument essay should have three main sections:

- A description of the problem

- Your proposed solution

- Justification for the solution you are proposing

(You may [and should] include additional sections or subsections as needed.)

Example of a proposal argument thesis statement : Our school should require all incoming freshmen to take a philosophy class so they can learn to understand and analyze multiple perspectives.

Examples of questions you might consider:

- Should students be required to take philosophy classes?

- Should new and expecting parents be given the option of enrolling in parenting classes at no cost to them?

- Should the county install cameras on all traffic lights?

- Should the school cut down a forested acre of land to build a new parking lot?

- Should public schools teach both English and Spanish beginning in kindergarten?

Option 2: Definition Argument

Construct a definition argument based on your definition of a controversial term: argue that an object or concept qualifies as a certain term, which you define based on specific criteria. Choose an important term that matters to you and that you believe will matter to others; base your argument on your own definition of that term.

Example of a definition argument thesis statement: Caffeine is a drug because it has predictable, measurable effects on the user’s central nervous system. Potential words for definition: animal, animal cruelty, art, beautiful, cheating, disease, drug, evil, food, hate crime, healthy, natural, poison, role model, sport You may choose a word not on the list. However, be sure to 1) check with your instructor, and 2) choose something that can be reasonably debated.

- Is caffeine a drug?

- Is alcoholism a disease?

- Are human beings animals?

- Is refined sugar a poison?

- Is kayaking a sport?

Examples of definition argument thesis statements:

- Caffeine is a drug because it causes physiological changes and is addictive.

- Kayaking is a sport because it requires physical exertion and can be done competitively.

Option 3: Causal Argument

Construct a causal argument in which you argue that a specific cause or causes led to a specific outcome, or that a specific action will result in a specific consequence. (Do NOT argue that a person or group should or should not take an action; this would be a proposal rather than a causal argument.)

Example of a causal argument thesis statement: Regular journaling leads to improved academic outcomes for incoming freshmen by helping them cope with stress, improve their writing skills, and develop their ability to concentrate for sustained periods of time.

- Does journaling lead to benefits for students?

- Do stimulants cause psychosis?

- Does advertising cause men and women to have unrealistic ideals of physical attractiveness?

- What causes, has caused, or will cause unemployment rates to rise or lower? (For an issue like this, it would be a good idea to consider a specific place and time—for example, in the state of Georgia from 2018-2019.)

- Why or how do people become addicted to a specific substance (sugar, illicit drugs, alcohol, etc.)?

Criteria for success

The argument essay should adhere to the following guidelines: .

- The essay meets requirements for the type of argument it is intended to convey (definition argument, proposal argument, or causal argument).

- The essay is based on a clearly stated, arguable thesis statement.

- The thesis is appropriately developed and supported: the writer has provided evidence, examples, and analysis as appropriate.

- The essay is cohesive/stays on topic.

- The writing is clear and coherent/makes sense.

- The tone and language are appropriate for the audience and purpose.

- The essay has an interesting, relevant title.

- The writer has gone through the entire writing process, revising substantially and thoughtfully.

- The writing adheres to grammar and punctuation rules.

The argument essay should adhere to all formatting criteria:

- MLA format, in the essay and on the Works Cited page

- Essay length: 800-1200 words

- Font: Size 12, Times New Roman font throughout

- Double-spaced lines

- 1-inch margins on all sides

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

63 5.8 Causal and Proposal Arguments

Causal arguments attempt to make a case that one thing led to another. They answer the question “What caused it?” Causes are often complex and multiple. Before we choose a strategy for a causal argument it can help to identify our purpose. Why do we need to know the cause? How will it help us?

Purposes of causal arguments

To get a complete picture of how and why something happened: In this case, we will want to look for multiple causes, each of which may play a different role. Some might be background conditions, others might spark the event, and others may be influences that sped up the event once it got started. In this case, we often speak of near causes that are close in time or space to the event itself, and remote causes , which are further away or further in the past. We can also describe a chain of causes , with one thing leading to the next, which leads to the next. It may even be the case that we have a feedback loop where a first event causes a second event and the second event triggers more of the first, creating an endless circle of causation. For example, as sea ice melts in the arctic, the dark water absorbs more heat, which warms it further, which melts more ice, which makes the water absorb more heat, etc. If the results are bad, this is called a vicious circle.

To decide who is responsible: Sometimes if an event has multiple causes, we may be most concerned with deciding who bears responsibility and how much. In a car accident, the driver might bear responsibility and the car manufacturer might bear some as well. We will have to argue that the responsible party caused the event but we will also have to show that there was a moral obligation not to do what the party did. That implies some degree of choice and knowledge of possible consequences. If the driver was following all good driving regulations and triggered an explosion by activating the turn signal, clearly the driver cannot be held responsible.

To figure out how to make something happen: In this case we need to zero in on a factor or factors that will push the event forward. Such a factor is sometimes called a precipitating cause . The success of this push will depend on circumstances being right for it, so we will likely also need to describe the conditions that have to be in place for the precipitating cause to actually precipitate the event. If there are likely factors that could block the event, we need to show that those can be eliminated. For example, if we propose a particular surgery to fix a heart problem, we will also need to show that the patient can get to a hospital that performs the surgery and get an appointment. We will certainly need to show that the patient is likely to tolerate the surgery.

To stop something from happening: In this case, we do not need to describe all possible causes. We want to find a factor that is so necessary to the bad result that if we get rid of that factor, the result cannot occur. Then if we eliminate that factor, we can block the bad result. If we cannot find a single such factor, we may at least be able to find one that will make the bad result less likely. For example, to reduce wildfire risk in California, we cannot get rid of all fire whatsoever, but we can repair power lines and aging gas and electric infrastructure to reduce the risk that defects in this system will spark a fire. Or we could try to reduce the damage fires cause by focusing on clearing underbrush.

To predict what might happen in future: As Jeanne Fahnestock and Marie Secor put it in A Rhetoric of Argument , “When you argue for a prediction, you try to convince your reader that all the causes needed to bring about an event are in place or will fall into place.” You also may need to show that nothing will intervene to block the event from happening. One common way to support a prediction is by comparing it to a past event that has already played out. For example, we might argue that humans have survived natural disasters in the past, so we will survive the effects of climate change as well. As Fahnestock and Secor point out, however, “the argument is only as good as the analogy, which sometimes must itself be supported.” How comparable are the disasters of the past to the likely effects of climate change? The argument would need to describe both past and possible future events and convince us that they are similar in severity.

Techniques and cautions for causal argument

So how does a writer make a case that one thing causes another? The briefest answer is that the writer needs to convince us that the factor and the event are correlated and also that there is some way in which the factor could plausibly lead to the event. Then the writer will need to convince us that they have done due diligence in considering and eliminating alternate possibilities for the cause and alternate explanations for any correlation between the factor and the event.

Identify possible causes

If other writers have already identified possible causes, an argument simply needs to refer back to those and add in any that have been missed. If not, the writer can put themselves in the role of detective and imagine what might have caused the event.

Determine which factor is most correlated with the event

If we think that a factor may commonly cause an event, the first question to ask is whether they go together. If we are looking for a sole cause, we can ask if the factor is always there when the event happens and always absent when the event doesn’t happen. Do the factor and the event follow the same trends? The following methods of arguing for causality were developed by philosopher John Stuart Mill, and are often referred to as “Mill’s methods.”

If the event is repeated and every time it happens, a common factor is present, that common factor may be the cause.

If there is a single difference between cases where the event takes place and cases where it doesn’t.

If an event and a possible cause are repeated over and over and they happen to varying degrees, we can check whether they always increase and decrease together. This is often best done with a graph so we can visually check whether the lines follow the same pattern.

Finally, ruling out other possible causes can support a case that the one remaining possible cause did in fact operate.

Explain how that factor could have caused the event

In order to believe that one thing caused another, we usually need to have some idea of how the first thing could cause the second. If we cannot imagine how one would cause another, why should we find it plausible? If we are talking about human behavior, then we are looking for motivation: love, hate, envy, greed, desire for power, etc. If we are talking about a physical event, then we need to look at physical forces. Scientists have dedicated much research to establishing how carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could effectively trap heat and warm the planet.

If there is enough other evidence to show that one thing caused another but the way it happened is still unknown, the argument can note that and perhaps point toward further studies that would establish the mechanism. The writer may want to qualify their argument with “may” or “might” or “seems to indicate,” if they cannot explain how the supposed cause led to the effect.

Eliminate alternative explanations

The catchphrase “correlation is not causation” can help us to remember the dangers of the methods above. It’s usually easy to show that two things happen at the same time or in the same pattern, but hard to show that one actually causes another. Correlation can be a good reason to investigate whether something is the cause, and it can provide some evidence of causality, but it is not proof. Sometimes two unrelated things may be correlated, like the number of women in Congress and the price of milk. We can imagine that both might follow an upward trend, one because of the increasing equality of women in society and the other because of inflation. Describing a plausible agency, or way in which one thing led to another, can help show that the correlation is not random. If we find a strong correlation, we can imagine various causal arguments that would explain it and argue that the one we support has the most plausible agency.

Sometimes things vary together because there is a common cause that affects both of them. An argument can explore possible third factors that may have led to both events. For example, students who go to elite colleges tend to make more money than students who go to less elite colleges. Did the elite colleges make the difference? Or are both the college choice and the later earnings due to a third cause, such as family connections? In his book Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual , journalist Michael Pollan assesses studies on the effects of supplements like multivitamins and concludes that people who take supplements are also those who have better diet and exercise habits, and that the supplements themselves have no effect on health. He advises, “Be the kind of person who takes supplements — then skip the supplements.”

If we have two phenomena that are correlated and happen at the same time, it’s worth considering whether the second phenomenon could actually have caused the first rather than the other way around. For example, if we find that gun violence and violence within video games are both on the rise, we shouldn’t leap to blame video games for the increase in shootings. It may be that people who play video games are being influenced by violence in the games and becoming more likely to go out and shoot people in real life. But could it also be that as gun violence increases in society for other reasons, such violence is a bigger part of people’s consciousness, leading video game makers and gamers to incorporate more violence in their games? It might be that causality operates in both directions, creating a feedback loop as we discussed above.

Proving causality is tricky, and often even rigorous academic studies can do little more than suggest that causality is probable or possible. There are a host of laboratory and statistical methods for testing causality. The gold standard for an experiment to determine a cause is a double-blind, randomized control trial in which there are two groups of people randomly assigned. One group gets the drug being studied and one group gets the placebo, but neither the participants nor the researchers know which is which. This kind of study eliminates the effect of unconscious suggestion, but it is often not possible for ethical and logistical reasons.

The ins and outs of causal arguments are worth studying in a statistics course or a philosophy course, but even without such a course we can do a better job of assessing causes if we develop the habit of looking for alternate explanations.

Practice Exercise

Reflect on the following to construct a causal argument. What would be the best intervention to introduce in society to reduce the rate of violent crime? Below are some possible causes of violent crime. Choose one and describe how it could lead to violent crime. Then think of a way to intervene in that process to stop it. What method from among those described in this section would you use to convince someone that your intervention would work to lower rates of violent crime? Make up an argument using your chosen method and the kind of evidence, either anecdotal or statistical, you would find convincing.

Possible causes of violent crime:

Homophobia and transphobia

Testosterone

Child abuse

Violence in the media

Role models who exhibit toxic masculinity

Violent video games

Systemic racism

Lack of education on expressing emotions

Unemployment

Not enough law enforcement

Economic inequality

The availability of guns

Proposal arguments

Proposal arguments attempt to push for action of some kind. They answer the question “What should be done about it?”

In order to build up to a proposal, an argument needs to incorporate elements of definition argument, evaluation argument, and causal argument. First, we will need to define a problem or a situation that calls for action. Then we need to make an evaluation argument to convince readers that the problem is bad enough to be worth addressing. This will create a sense of urgency within the argument and inspire the audience to seek and adopt proposed action. In most cases, it will need to make causal arguments about the roots of the problem and the good effects of the proposed solution.

Common elements of proposal arguments

Background on the problem, opportunity, or situation.

Often just after the introduction, the background section discusses what has brought about the need for the proposal—what problem, what opportunity exists for improving things, what the basic situation is. For example, management of a chain of daycare centers may need to ensure that all employees know CPR because of new state mandates requiring it, or an owner of pine timberland in eastern Oregon may want to make sure the land can produce saleable timber without destroying the environment.

While the named audience of the proposal may know the problem very well, writing the background section is useful in demonstrating our particular view of the problem. If we cannot assume readers know the problem, we will need to spend more time convincing them that the problem or opportunity exists and that it should be addressed. For a larger audience not familiar with the problem, this section can give detailed context.

Description of the proposed solution

Here we define the nature of what we are proposing so readers can see what is involved in the proposed action. For example, if we write an essay proposing to donate food scraps from restaurants to pig farms, we will need to define what will be considered food scraps. In another example, if we argue that organic produce is inherently healthier for consumers than non-organic produce, and we propose governmental subsidies to reduce the cost of organic produce, we will need to define “organic” and describe how much the government subsidies will be and which products or consumers will be eligible. These examples illustrate the frequency with which different types of argument overlap within a single work.

If we have not already covered the proposal’s methods in the description, we may want to add this. How will we go about completing the proposed work? For example, in the above example about food scraps, we would want to describe how the leftover food will be stored and delivered to the pig farms. Describing the methods shows the audience we have a sound, thoughtful approach to the project. It serves to demonstrate that we have the knowledge of the field to complete the project.

Feasibility of the project

A proposal argument needs to convince readers that the project can actually be accomplished. How can enough time, money, and will be found to make it happen? Have similar proposals been carried out successfully in the past? For example, we might observe that according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Rutgers University runs a program that sends a ton of food scraps a day from its dining halls to a local farm. If we describe how other efforts overcame obstacles, we will persuade readers that if they can succeed, this proposal can as well.

Benefits of the proposal

Most proposals discuss the advantages or benefits that will come from the solution proposed. Describing the benefits helps you win the audience to your side, so readers become more invested in adopting your proposed solution. In the food scraps example, we might emphasize that the Rutgers program, rather than costing more, led to $100,000 a year in savings because the dining halls no longer needed to pay to have the food scraps hauled away. We could calculate the predicted savings for our new proposed program as well.

In order to predict the positive effects of the proposal and show how implementing it will lead to good results, we will want to use causal arguments.

Sample annotated proposal argument

The sample essay “Why We Should Open Our Borders” by student Laurent Wenjun Jiang can serve as an example. Annotations point out how Jiang uses several proposal argument strategies.

Sample proposal essay “Why We Should Open Our Borders” in PDF with margin notes

Browse news and opinion websites to find a proposal argument that you strongly support. Once you have chosen a proposal, read it closely and look for the elements discussed in this section. Do you find enough discussion of the background, methods, feasibility, and benefits of the proposal? Discuss at least one way in which you think the proposal could be revised to be even more convincing.

Attributions

Parts of this section on proposal arguments are original content by Anna Mills and Darya Myers. Parts were adapted from Technical Writing, which was derived in turn by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC BY 4.0 .

5.9 Argumentative Reasoning

By Adam Falik

Once you have clearly articulated a thesis, you need to support that claim with reasons. Reasons answer the question: Why should the claim be? Reasons justify the claim, and in an argument, support the claim’s validity.

The reasons for an argument should follow a “because.” That “because” can either be present or implied. Consider this example:

College athletes should be paid [Claim] because they generate income for their school [Reason] while being unable to obtain employment of their own due to the demands of academic and athletic schedules. [Reason]

Reasons are the backbone of your argument. Your argumentative paper will be mostly comprised of the articulation of your claim, an explanation of reasons, and evidence that back up your reasons.

Not All Reasons Are The Same

Not all reasons are of equal validity. The truth is that some of your reasons may be more urgent or stronger than others. Let’s say you make the rather simple claim that a cigarette smoker should quit smoking. Your claim: A cigarette smoker should break the habit and quit smoking , can be supported by (at a minimum) three reasons:

1) Smoking is damaging for one’s health

2) Second-hand smoking is damaging to other people’s health

3) Cigarette butts have a negative environmental impact on the planet

It can be argued that compared to the risk of heart disease, emphysema, and lung cancer threatening habitual cigarette smokers, as well as the health dangers to those who are impacted by second-hand smoke, that the environmental impact of cigarette butts is of lesser value. And that might be true. Though the majority of this paper might be focused on health risks, the environmental impact is still significant and warrants inclusion in the paper. The point is that not all reasons are equal in value, and not all reasons will be supported with equal amounts of evidence.

There is no exact number of reasons that should be included in support of a claim, just as there is no precise number of cited evidence that should support a reason. Generally, quality will reign over quantity. A few strong reasons that are supported by credible evidence are better than lots of reasons that are either unsupported by evidence, or supported by weaker evidence.

CLAIMS/REASONS/EVIDENCE GRAPHIC (coming)

5.10 SUPPORTING EVIDENCE

Amanda Lloyd, Adam Falik and Doreen Piano

Adding Supporting Evidence to Body Paragraphs

Supporting your ideas effectively is essential to establishing your credibility as a writer, so you should choose your supporting evidence wisely and clearly explain it to your audience.

Present your supporting evidence in the form of paraphrases and direct quotations. Quotations should be used sparingly; that said, direct quotations are often handy when you would like to illustrate a particularly well- written passage or draw attention to an author’s use of tone, diction, or syntax that would likely become lost in a paraphrase.

Types of support might include the following:

• Statistics and data

• Research studies and scholarship

• Hypothetical and real-life examples

• Historical facts

• Analogies

• Precedents

• Case histories

• Expert testimonies or opinions

• Eye-witness accounts

• Applicable personal experiences or anecdotes

Varying your means of support will lend further credibility to your essay and help to maintain your reader’s interest. Keep in mind, though, that some types of support are more appropriate for certain academic disciplines than for others.

Remember that in an argumentative paper, your evidence supports your reason. In the paragraph referred to above with the topic sentence “Colleges athletes often bring in a great deal of income to their college and university through sponsorships,” your evidence might be data that and statistics of athletes who have brought in sponsorship deals from which their colleges and universities have profited.

Direct quotations and paraphrases must be integrated effortlessly and documented appropriately.

Providing Context for Supporting Evidence

Before introducing your supporting evidence, it may occasionally be necessary to provide some context for that information. You should assume that your audience has not read your source texts in their entirety, if at all, so including some background or connecting material between your topic sentence and supporting evidence is frequently essential.

The information contained in your evidence selection might need to be introduced, explained, or defined so that your supporting evidence is perfectly clear to an audience unfamiliar with the source material. For example, your supporting evidence might contain a reference to a concept or term that is not explained or defined in the excerpt or elsewhere in your essay. In this instance, you would need to provide some clarification for your audience. Anticipating your audience is particularly important when incorporating supporting evidence into your essay.

Now that we have a good idea what it means to develop support for the main ideas of your paragraphs, let’s talk about how to make sure that those supporting details are solid and convincing.

Good vs. Weak Support

When you’re developing paragraphs, you should already have a plan for your essay, at least at the most basic level. You know what your topic is, you have a working claim, and you have at least a couple of supporting ideas/reasons in mind that will further develop and support your claim. You need to make sure that the support that you develop for these ideas is solid. Understanding and appealing to your audience can also be helpful in determining what your readers will consider good support and what they’ll consider to be weak. Here are some tips on what to strive for and what to avoid when it comes to supporting evidence.

Good Support

• is relevant and focused (sticks to the point)

• is well developed

• provides sufficient detail

• is vivid and descriptive

• is well organized

• is coherent and consistent

• highlights key terms and ideas

Weak Support

• lacks a clear connection to the point that it’s meant to support

• lacks development

• lacks detail or gives too much detail

• is vague and imprecise

• lacks organization

• seems disjointed (ideas don’t clearly relate to each other)

• lacks emphasis of key terms and ideas

How Much Evidence Do I Need?[DP1]

(NOTE: This should be one paragraph but the formatting is off)

Students often ask: How much evidence do I need? The answer is:

You need exactly the amount of evidence that makes your reason supportable.

In other words: There is no exact quantity of direct and indirect quotations you should be providing.

What matters is that you’ve supported your idea/reason with good enough support to convince your

reader of the integrity of your reason.

This chapter contains material from “The Word on College Reading and Writing” by Monique Babin, Carol Burnell, Susan Pesznecker, Nicole Rosevear, Jaime Wood, OpenOregon Educational Resources , Higher Education Coordination Commission: Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

5.11 EXPLAINING EVIDENCE

Remember not to conclude your body paragraph with supporting evidence. Rather than assuming that the evidence you have provided speaks for itself, it is important to explain why that evidence proves or supports the key idea you present in your topic sentence and (ultimately) the claim you make in your thesis statement.

This explanation can appear in one or more of the following forms:

• Evaluation

• Relevance or significance

• Comparison or contrast

• Cause and effect

• Refutation or concession

• Suggested action or conclusion

• Proposal of further study

• Personal reaction

Try to avoid simply repeating the source material in a different way or using phrases like “This quote means” to begin your explanation. Keep in mind that your voice should control your essay and guide your audience to a greater understanding of the source material’s relevance to your claim. Also, be mindful of the rhythm of your body paragraphs and the placement of your evidence. Try not to structure the same paragraphs over and over with a topic sentence, a quote, then the explanation of that quote. Seek variety. Paragraphs that repeat themselves in structures run the risk of boring readers.

Sandbox: Interactive OER for Dual Enrollment Copyright © by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Place order

How to write a causal Analysis Essay that scores an A

It is human nature to want to understand things and what causes them. When we see, hear, or experience something we do not understand, we often try to find out the cause or the explanation either from family and friends or from the internet.

In college, you will be required occasionally to find out the causes, effects, or reasons for various phenomena via causal analysis essay assignments.

This article details everything important about causal analysis essay assignments, including the structure and the steps for writing one.

What Is a Causal Analysis Essay?

Strictly put, a causal analysis essay assignment or an academic writing task requires you to explain the cause of a specific phenomenon analytically.

Causal analysis essays are sometimes referred to as cause-and-effect essays. Because they also reveal how one thing (cause) leads to another (effect). In this respect, when writing a causal analysis essay, you first begin by stating your claim and then backing it up using arguments and supporting facts. You need to show how a specific issue correlates to an underlying problem.

For example, you can be tasked with writing about how the global COVID-19 pandemic led to the rise of e-learning. You need to explore e-learning adoption before and post the pandemic to unravel the real issues that amount as cause and the effects of these issues on e-learning adoption.

Structure of a Causal Analysis Essay

The structure of a causal analysis essay is the typical short essay structure. It is a five-paragraph structure essay with an introduction paragraph, 3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion paragraph. If you follow this structure to write your essay, as your professor expects, you will end up with an academic paper with a strong logical flow.

Find out what to include in each paragraph of your causal analysis essay in the subsection below.

1. Introduction Paragraph

In the introduction paragraph of an essay , you introduce the topic you want to discuss in your essay. You should aim to make your introduction paragraph as interesting as possible. Failure to do so may make your paper uninteresting or boring for the reader. And you do not want this if you are aiming for an excellent grade.

In addition, make sure your introduction paragraph provides background information to make the reader understand what will be discussed. You should restrict the background information to 50 words to avoid overloading the reader with unnecessary information in your intro.

After providing background information, you should include your thesis statement or central argument. Your thesis statement is your most important statement. This is because it sets the tone or the theme for the essay. So, you should be very keen when writing it to ensure it is on point. Remember, a good thesis statement is detailed enough to leave room for argumentation.

2. Body Paragraphs

In your first body paragraph, your first sentence should be your strongest argument supporting your thesis statement. Since this is a causal analysis essay, the strongest argument will naturally be the most significant cause or effect of the phenomena described in your introduction paragraph. The first sentence should be followed by evidence or explanation, plus examples where possible. The evidence should be followed by a closing sentence that wraps everything up nicely. Ensure that you follow the basic rules of paragraphing in essay writing .

The second body paragraph should focus on the second strongest argument favoring your thesis statement. As with the first paragraph, the argument should be followed by the evidence/explanation and a closing sentence. The first sentence in the third body paragraph should state the third strongest argument in favor of your thesis statement. The rest of the paragraph should follow the structure of the other body paragraphs.

3. Conclusion

After writing a good introduction with your thesis statement and three body paragraphs, each focusing on a single cause or critical point, you must wrap up the essay with an excellent conclusion . Your conclusion should restate the thesis and the key causes in your causal analysis essay. It should also include a nice closing sentence that wraps the entire essay up.

Causal Analysis Essay Outline

Now that you know the causal analysis essay structure, it is time to discover the outline and how to create one. Knowing how to create one will help you create one and ensure your paper is well-structured and organized.

How to create a causal analysis essay outline

I. Introduction

- Hook statement (Write an interesting fact or statement about the topic)

- Background information (Highlight the background information about the topic that you will include)

- Thesis statement (State the central argument you will be discussing in your essay)

II. Body paragraph 1

- Topic sentence (State the strongest argument (the first cause) in support of your thesis)

- Evidence (Highlight the critical evidence you will use to support the argument above)

- Concluding sentence (Write the sentence you will use to close out this paragraph)

III. Body paragraph 2

- Topic sentence (State the second strongest argument (the second cause) in support of your thesis)

IV. Body paragraph 3

- Topic sentence (State the third strongest argument (the third cause) in support of your thesis)

V. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis

- Summarize your key arguments

- Closing statement (Write the sentence you will use to conclude your essay)

As you can see above, a causal analysis essay outline is similar to the standard outline for short academic papers. To create your own causal analysis essay, follow the instructions above. Just make sure your outline is as comprehensive as possible to make writing the actual easy a walk in the park.

Steps For Writing a Causal Analysis Essay

In this section, you will discover how to write an actual causal analysis essay. Let’s begin.

1. Read the essay prompt carefully

The fact that you are reading this article means you already know you need to write a causal analysis essay. You probably got this information from the essay prompt. If you did, it means you are already on the right track. You now need to read the prompt carefully again.

Read it carefully to understand the essay question or prompt entirely. Also, read it carefully to understand the essay requirements. Failure to follow the requirements in your essay assignment could be costly for you; it could result in an inferior grade.

So, the first step to writing a causal analysis essay is to read the prompt carefully to understand the question and the requirements.

2. Research the essay topic and create a thesis

After reading and understanding the essay topic, the next thing you need to do is to research the essay topic. Research is important as it will help you understand the topic better and decide how you will answer it.

When conducting research, you should note the key points related to the essay topic. The typical causal analysis essay assignment will require you to discuss the causes of a specific phenomenon. Therefore, focus on noting the key causes of the phenomenon you have been asked to write an essay on in the prompt.

Once you have researched to the extent that you fully understand the topic, you should create a thesis statement. The statement should explain what your entire essay will be focusing on. A typical thesis statement for a causal analysis essay sounds like this, “The main causes of global poverty are conflict, climate change, and inequality.”

3. Create an outline

You should create an outline after researching your paper and creating a thesis statement. Simply follow the instructions we have provided in the section above this one to create your causal analysis essay outline. You should find it easy to create an outline for your essay since you have already created a thesis statement and you know the leading causes you will be discussing in your essay.

Make sure your outline is as comprehensive as it can be. When you create a comprehensive outline, you make your work easy. In other words, you make writing the actual essay very easy. When creating an outline, the most important things you should not forget to outline include the opening sentence, the thesis statement, the main supporting arguments, and the closing sentence.

4. Write the essay

When you are done creating an outline for your essay, you should take a short break and then embark on writing the essay following the outline as a guide. With a comprehensive outline, you shouldn’t find writing your causal analysis essay challenging. You should refer to the outline for guidance when you get stuck in any part of your essay.

The best way to write the essay is sequential. Begin with the introduction, then the body paragraphs, and lastly, the conclusion. Write your essay in a simple and easy-to-understand language. And keep in mind that your goal is to make it as smooth flowing as possible.

5. Add in-text citations

Once you are done writing your causal analysis essay, you need to add the in-text citations. Don’t just add them randomly. Add citations to the ideas or points that are not yours. Add in-text citations throughout your essay. This will make your work look credible. You will also get points for proper referencing if you follow the required format or style.

Of course, the only way you can have in-text citations to add to your essay in this step is if you note the source of each note you made during your research. So, indicate the source next to each note you make during research.

6. Take a break

You should take a break after writing your essay, adding in-text citations and a references page. This is very important at this juncture. Because it allows your brain to rest and forget about the essay, at least momentarily, ensure the break lasts for at least six hours. If you take such a break, you will have a fresh pair of eyes when you look at your essay in the next step.

7. Edit your essay

After taking a break, you should edit your essay. Since you took a break in the previous step, you will have a fresh pair of eyes that should make it easy to catch mistakes. Read your essay aloud to make sure you catch all the issues, errors, and mistakes. Read it slowly to make sure you do not miss anything.

After editing your essay , give it to someone to read it and identify any mistakes you might have missed. Then check the identified mistakes if they are actual mistakes and edit them out of your essay. When you complete this step, your causal analysis essay will be ready for submission.

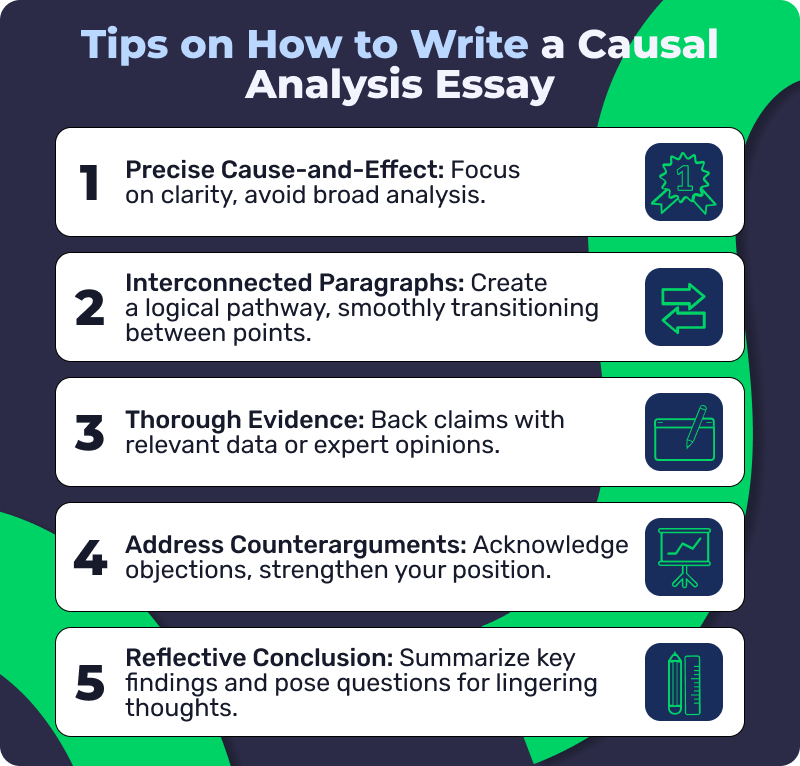

Tips For Writing an Excellent Causal Analysis Essay

If you want to write a good causal analysis essay, follow the above steps. If you want to write an excellent causal analysis essay, incorporate the tips below when following the steps above.

- Ensure your essay is straightforward to read and understand to give your professor an easy time grading it. This will increase your chances of getting an excellent grade.

- Ensure you include a strong thesis statement at the end of your introduction paragraph. Without a strong thesis statement, your essay will be challenging to follow.

- Ensure there is no vague phrase or statement in your essay. This will make your essay stronger and more credible. It will also ensure you don’t lose marks for clarity.

- Use examples generously in your essay. This will make it easier to understand. It will also make it more authentic and useful.

- Do not belabor points in your essay. Simply explain your key points clearly and concisely. Do not go round and round in circles saying the same thing in different words.

- Support any specific idea or point you include with evidence. You are just a high school or undergraduate student; nobody will take your word for all the key claims and arguments you make. So back everything important you say with evidence from credible sources.

- Do not forget to proofread your essay thoroughly. Doing this is the only way you will convert your ordinary causal analysis essay into something extraordinary.

Example Of a Causal Analysis Essay

A typical causal analysis essay will describe the causes of a problem or a phenomenon. It is a cause-and-effect essay. This section will provide an example of a causal analysis essay. We hope this short causal analysis essay example will make it easy for you to write your own causal analysis essay.

Why do teenagers use drugs, and the negative effects of using drugs? Drug use is prevalent nowadays among teenagers, especially in urban areas across the country. Most teenagers who use drugs use it because of peer pressure or as a reaction to bullying and other sorts of trauma. Drugs use among young people often results in various negative effects, including poor well-being, negative self-image, and addiction. Teenager drug use often leads to poor well-being. Various studies have shown that teenagers who use drugs often suffer from poor health and well-being. This is because the drugs they use without a prescription are dangerous and often produce unpleasant symptoms. The only way drug-using teenagers can reverse this trend is if they say no to drugs. Teenagers who use drugs often end up having a negative self-image. The negative self-image is often brought out by the secrecy surrounding drug use and the negativity associated with drug use. The negative self-image can sometimes lead to depression or even attempted suicide. The best thing about this effect of drug use is that it can be reversed through therapy or an intervention. Teenagers who use drugs usually end up getting addicted. Drug addiction is a terrible condition that forces those with it to repeatedly seek the “high” the drugs offer. This can lead to dependence and a terrible addiction. It can also lead to the addict stealing to get money for the drugs. Despite the negative effects of addiction, it can also be eliminated. In conclusion, Drugs use among youth can lead to negative effects such as addiction, poor self-image, and poor well-being. These negative effects show that drug use can be hazardous for young people and that efforts should be made to put an end to it. Without robust efforts to put an end to drug use among youth, likely, a section of the youth will forever be lost to drugs.

Causal Analysis Topics

Choosing a good causal analysis essay topic will help ensure your essay is exciting and fun to read. Check out our causal analysis topics below to get inspiration to create your fun causal analysis essay topic.

- What are the effects of too much internet on the personalities of children?

- Why is cyberbullying such a big issue in the current world?

- What has been the positive impact of technology in the healthcare industry?

- What is the impact of technology on teaching methods?

- What are the negative effects of misinformation on the internet?

- What causes the increasing number of mass shooting incidents in the country?

- What caused the emergence of the feminist movement?

- Why is there gender bias in American politics?

- What has led to the calls for stricter gun laws in the United States?

- What led to the most recent US government shutdown?

- Why did the coronavirus pandemic have a huge negative impact on the world economy?

- What are the causes of the age-old Palestinian conflict?

- What led to the separation of the KOREA peninsula?

- Why are cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin rapidly gaining popularity?

- What has led to the recent increase in cases of cyberbullying?

- What is the cause of global warming and its impact on the world?

- What are the negative effects of water pollution?

- The biggest causes of environmental pollution

- What caused the Iranian Revolution?

- What caused the French Revolution?

- What were the biggest causes of the First World War?

- Why was Mussolini very successful in spreading fascism in Italy?

- Explain why homeschooling is gaining popularity across the world.

- What made China halt its one-child policy?

- Why do so many people still oppose the Obamacare Act?

Parting Shot!

The information presented in this article is sufficient for any college student to write an excellent causal analysis essay. So, if you have time, all you need to do is to follow the structure, the steps, and the tips presented in this article to develop the perfect causal analysis essay.

Related Reading:

- How to write a good case study

- Tips and steps for writing an excellent analytical essay

- How to know that an article is peer-reviewed.

If you do not have the time to write the essay or are not confident enough in your writing skills, you should order one from us. Hire someone to write your essay from EssayManiacs, and rest assured, you will nail the paper. We are an assignment-help business with dozens of experienced tutors and writers who can handle almost any academic assignment.

If you order your causal analysis essay from us, you will get a well-researched, well-developed, and 100% original essay with zero grammar errors. Start working with us today for excellent essays, research papers, and other academic assignments.

Need a Discount to Order?

15% off first order, what you get from us.

Plagiarism-free papers

Our papers are 100% original and unique to pass online plagiarism checkers.

Well-researched academic papers

Even when we say essays for sale, they meet academic writing conventions.

24/7 online support

Hit us up on live chat or Messenger for continuous help with your essays.

Easy communication with writers

Order essays and begin communicating with your writer directly and anonymously.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics