Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How to realize immense promise of gene editing

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

When will patients see personalized cancer vaccines?

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds.

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

MGH Communications

New research indicates that physical activity lowers cardiovascular disease risk in part by reducing stress-related signaling in the brain.

In the study, which was led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital and published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology , people with stress-related conditions such as depression experienced the most cardiovascular benefits from physical activity.

To assess the mechanisms underlying the psychological and cardiovascular disease benefits of physical activity, Ahmed Tawakol , an investigator and cardiologist in the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, and his colleagues analyzed medical records and other information of 50,359 participants from the Mass General Brigham Biobank who completed a physical activity survey.

A subset of 774 participants also underwent brain imaging tests and measurements of stress-related brain activity.

Over a median follow-up of 10 years, 12.9 percent of participants developed cardiovascular disease. Participants who met physical activity recommendations had a 23 percent lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease compared with those not meeting these recommendations.

Individuals with higher levels of physical activity also tended to have lower stress-related brain activity. Notably, reductions in stress-associated brain activity were driven by gains in function in the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain involved in executive function (i.e., decision-making, impulse control) and is known to restrain stress centers of the brain. Analyses accounted for other lifestyle variables and risk factors for coronary disease.

Moreover, reductions in stress-related brain signaling partially accounted for physical activity’s cardiovascular benefit.

As an extension of this finding, the researchers found in a cohort of 50,359 participants that the cardiovascular benefit of exercise was substantially greater among participants who would be expected to have higher stress-related brain activity, such as those with pre-existing depression.

“Physical activity was roughly twice as effective in lowering cardiovascular disease risk among those with depression. Effects on the brain’s stress-related activity may explain this novel observation,” says Tawakol, senior author of the study.

“Prospective studies are needed to identify potential mediators and to prove causality. In the meantime, clinicians could convey to patients that physical activity may have important brain effects, which may impart greater cardiovascular benefits among individuals with stress-related syndromes such as depression.”

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Share this article

You might like.

Nobel-winning CRISPR pioneer says approval of revolutionary sickle-cell therapy shows need for more efficient, less expensive process

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

Sooner than you may think, says researcher who recently won Sjöberg Prize for pioneering work in field

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

The Future of Mental Health

Dispatches on the latest efforts in psychological and psychiatric treatment

How Exercise Boosts the Brain and Improves Mental Health

New research is revealing how physical activity can reduce and even ward off depression, anxiety and other psychological ailments

Bob Holmes, Knowable

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1f/9a/1f9acb47-7f4e-499a-854c-1a93e355130f/gettyimages-861458264_web.jpg)

It’s hardly news that exercise is good for your physical health , and has long been extolled for mental health as well. But researchers are now making progress in understanding how, exactly, exercise may work its mental magic.

Exercise, they are learning, has profound effects on brain structure itself, and especially in regions most affected by depression and schizophrenia. It also provides other, more subtle benefits such as focus, a sense of accomplishment and sometimes social stimulation, all of which are therapeutic in their own right. And while more is generally better, even modest levels of physical activity, such as a daily walk, can pay big dividends for mental health.

“It’s a very potent intervention to be physically active,” says Anders Hovland, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bergen in Norway.

But that knowledge has barely begun to percolate into practice, says Joseph Firth, a mental health researcher at the University of Manchester in the UK. Just ask a hundred people receiving mental health care how many are getting exercise prescriptions as part of that care. “You wouldn’t find many,” Firth says.

Exercise — a tool against depression

Some of the strongest evidence for the mental benefits of exercise centers on depression. In 2016, Hovland and his colleagues searched the published literature and identified 23 clinical trials that tested the effectiveness of exercise in treating depression. Exercise was clearly effective and, in few studies, on par with antidepressant drugs, the researchers concluded.

And exercise offers several advantages. For one thing, antidepressant medications generally take several weeks or months to show their full effect. Exercise can improve mood almost immediately, making it a valuable supplement to frontline treatments such as drugs or therapy, notes Brett Gordon, an exercise psychology researcher at the Penn State College of Medicine. Plus, he says, exercise can counteract some of the unpleasant side effects of antidepressants, such as weight gain.

In addition, exercise has few of the negative side effects that are so common in drug therapies for depression and other disorders. “Many people who have mental health concerns are not enthusiastic about starting a medication for the rest of their lives, and are interested in pursuing other options. Exercise might be one of those options,” says Jacob Meyer, an exercise psychologist at Iowa State University.

There’s now emerging evidence that exercise also seems to help in treating or avoiding anxiety disorders , including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and possibly other serious psychotic conditions as well. “The more we do these studies, the more we see that exercise can be valuable,” says Firth.

There’s a flip side to this coin that’s especially relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic: If exercise stabilizes mental health, then anything that prevents people from working out is likely to destabilize it. To test this, Meyer and his colleagues surveyed more than 3,000 Americans about their activity before and during the pandemic. Those who became less active because of Covid reported more depression and poorer mental health , they found. (Ironically, those who had not exercised regularly pre-Covid didn’t report much change. “When you’re already at zero, where do you go?” says Meyer.)

But researchers are still figuring out exactly how muscular exertion acts on the brain to improve mental health. For most biomedical questions like this, the first stop is animal experiments, but they aren’t as useful in studies of mental health issues. “Psychological health is so uniquely human that it can be hard to make a good jump from animal models,” says Meyer.

Exercise and a healthy brain

Scientists have come up with a few ideas about how exercise enhances mental health , says Patrick J. Smith , a psychologist and biostatistician at Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina, who wrote about the subject in the 2021 Annual Review of Medicine with his Duke colleague Rhonda M. Merwin. It doesn’t seem to have much to do with cardiovascular fitness or muscular strength — the most obvious benefits of exercise — since how hard a person can work out is only weakly associated with their psychological health. Something else must be going on that’s more important than mere fitness, says Smith.

One likely possibility is that exercise buffs up the brain as well as the body. Physical exercise triggers the release of a protein known as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is one of the key molecules that encourage the growth of new brain cells — including, possibly, in the hippocampus, a brain region important in memory and learning. Since the hippocampus tends to be smaller or distorted in people with depression, anxiety and schizophrenia, boosting BDNF through exercise may be one way physical activity might help manage these conditions.

Sure enough, studies show that people with depression have lower levels of BDNF — and, notably, one effect of antidepressant drugs is to increase production of that molecule. Researchers have not yet shown directly that the exercise-associated increase in BDNF is what reduces depressive symptoms, but it remains one of the most promising possibilities, says Hovland.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/92/ed/92edabe0-a7a0-4a2a-9acb-e0ecb60dc078/g-exercise-mental-magic-alt_web.jpg)

Exercise may also help anxiety disorders. The brain changes prompted by BDNF appears to enhance learning, which is an important part of some anti-anxiety therapies. This suggests that exercise may be a useful way of improving the effectiveness of such therapies. One of the standard therapies for PTSD, for example, involves exposing patients to the fear-causing stimulus in a safe environment, so that the patients learn to recalibrate their reactions to trauma-linked cues — and the better they learn, the more durable this response might be.

Kevin Crombie, an exercise neuroscientist now at the University of Texas at Austin, and his colleagues tested this idea in the lab with 35 women with PTSD. Researchers first taught the volunteers to associate a particular geometric shape with a mild electric shock. The next day, the volunteers repeatedly saw the same shape without the shock, so that they would learn that the stimulus was now safe. A few minutes later, half the volunteers did 30 minutes of moderate exercise — jogging or uphill walking on a treadmill — while the other half did only light movement, not enough to breathe heavily.

The following day, those who had exercised were less likely to anticipate a shock when they saw the “trigger” shape, Crombie found — a sign that they had learned to no longer associate the trigger with danger . Moreover, those volunteers who showed the greatest exercise-induced increases in BDNF also did best at this relearning.

Although the evidence is not yet definitive, a few studies have suggested that regular exercise may lead to better outcomes in patients with schizophrenia too. Vijay Mittal, a psychologist at Northwestern University, wondered whether working out also might prevent people from developing the disorder in the first place.

Mittal works with teenagers who are at high risk of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, but who have not yet progressed to the full-on disorder. In the past two decades, researchers have gotten much better at recognizing such individuals just as they begin to display the earliest signs of illness, such as seeing shadows out of the corner of their eye or hearing indistinct voices when no one is home.

For about 10 percent to 33 percent of these teens, these early signs turn into something more serious. “A shadow might turn into a person,” says Mittal. “A whisper might turn into words. A suspicion that someone is following them might turn into the belief that the government is after them.”

Previously, Mittal had found that the hippocampus is different in at-risk teens who later slid down this slippery slope than in those who didn’t. He wondered whether exercise might help bolster the hippocampus and avert the slide. So his team tested this notion in a sample of 30 high-risk teens, half of whom followed a regimen of aerobic exercise twice a week for three months. (The other half, the control group, were told they were on the wait list for the exercise program.) The researchers used brain scans to look at participants’ hippocampus before and after the program.

The experiment has just concluded, and Mittal is still analyzing the results, which he calls promising. He cautions, however, that exercise is not a panacea. Schizophrenia is a diverse disease, and even if physical activity proves to be protective for some at-risk people, not all are likely to respond to it in the same way. “It’s really important to remember that these disorders are complicated. I’ve worked with people who exercise a lot and still have schizophrenia,” he says.

If Mittal’s work pans out, exercise may allow mental health workers to help a group that isn’t easily treated with drugs. “Someone who’s just at risk of a psychotic disorder, you can’t just give them medication, because that has risks too,” says Firth. “It would be fantastic to have something else in our arsenal.”

Exercise almost certainly has other effects on the brain, too, experts agree. For example, exercise stimulates the release of endocannabinoids, molecules that are important in modifying the connections between brain cells, the mechanism that underlies learning. This may provide another way of enhancing the learning that underlies successful treatment for depression, PTSD and other mental disorders. Indeed, Crombie’s study of exercise in a simplified model of PTSD therapy measured endocannabinoids as well as BDNF, and increases in both were associated with stronger learning responses.

And physical activity also moderates the body’s response to stress and reduces inflammation, both of which could plausibly help improve brain health in people with mental illness. “We have just scratched the surface,” says Hovland.

Moving the body, engaging the mind

But changing the structure of the brain isn’t the only way physical activity can be beneficial for those suffering from mental health conditions. The habit of exercise can itself be beneficial, by altering people’s thought patterns, says Smith.

For people with mental health issues, simply doing something — anything — can be helpful in its own right because it occupies their attention and keeps them from ruminating on their condition. Indeed, one survey of the published literature found that placebo exercise — that is, gentle stretching, too mild to cause any physiological effect — had almost half the beneficial effect on mental health as strenuous exercise did.

Besides just occupying the mind, regular workouts also give exercisers a clear sense of progress as their strength and fitness improves. This sense of accomplishment — which may be especially notable for weight training, where people make quick, easily measurable gains — can help offset some of the burden of anxiety and depression, says Gordon.

If so, playing a musical instrument, studying a language and many other activities could also help people cope with mental health conditions in a similar way. But exercise does more than that, making it one of the best choices for managing mental health. “You can see benefits from doing anything, but the exercise may confer greater benefits,” says Firth.

For one thing, relatively strenuous exercise teaches people to put up with short-term discomfort for long-term gain. People who suffer from anxiety disorders such as PTSD or panic attacks often show a reduced ability to tolerate mental discomfort, so that experiences most people would cope with result in uncontrolled anxiety instead. There’s now emerging evidence that regular exercise builds tolerance for internal discomfort, and this may explain part of its benefit in managing these conditions, Smith says.

Using exercise as a mental health treatment brings some challenges, however. “People with mental illness are also at higher risk of struggling with low motivation,” Firth says. This can make it difficult to organize and stick with an exercise program, and many patients need additional support.

This is often difficult, because psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health workers are often already overburdened. Plus, prescribing and supervising exercise hasn’t traditionally been within these practitioners’ purview. “We’re telling people, ‘Hey, exercise is helpful,’ but we’re telling it to people who can’t really incorporate it because they often don’t get any training,” Firth says. Exercise referral schemes, which link patients with fitness specialists and structured programs at community leisure centers, have been used in the UK and other places to encourage exercise in people with physical conditions such as obesity and diabetes. A similar approach could be valuable for mental health conditions, Firth says.

Therapists can also help patients persist for the long term by tailoring their exercise prescriptions to each individual’s capabilities. “I always tell patients that doing anything is better than doing nothing, and the best exercise for you is the one you’ll actually do,” Smith says.

The secret, he suggests, is to make sure people stop exercising before they’ve done so much it makes them feel exhausted afterward. “When you feel like crap after exercise, you’re not going to want to do it,” he says, because the brain tags the activity as something unpleasant. It’s far better to have the patient quit while they still have a positive feeling from the workout. “Without even realizing it, their brain tends to tag that activity as something more pleasurable. They don’t dread it.”

Even light activity — basically just moving around now and then during the day instead of sitting for hours at a time — may help. In one study of more than 4,000 adolescents in the UK, Aaron Kandola, a psychiatric epidemiologist at University College London, and his colleagues found that youths who undertook more light activity during the day had a lower risk of depressive symptoms than those who spent more time sitting.

“What we really need are big exercise trials where we compare different amounts against each other,” says Kandola. “Instead, what we have are different studies that used different amounts of activity.” That makes precise recommendations difficult, because each study varies in terms of its patient populations and methods, and follows results for a different length of time. As researchers learn more about the mechanisms linking exercise to mental health, they should be able to refine their exercise prescriptions so that patients are best able to manage their illnesses.

And exercise has powerful benefits for people with mental illness that go beyond its effects on the illnesses themselves. Many struggle with related issues such as social withdrawal and a reduced capacity for pleasure, says Firth. Standard medications reduce some symptoms but do nothing to address these other problems. Exercise — especially as part of a group — can help boost their mood and enrich their lives.

Even more important, people with serious mental illnesses such as severe depression and schizophrenia also are more likely to have significant physical health issues such as obesity, heart disease and other chronic diseases, and as a result their life expectancy is 10 to 25 years lower than that of unaffected people.

“Reducing those health risks is really paramount at the moment,” says Kandola. “That’s the big appeal of exercise: We already know it can improve physical health. If it does have mental health benefits as well, it can be quite an important addition to treatment.”

Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Subscriber-only Newsletter

Four Fitness Facts to Fuel Your Workout

Things to keep in mind for when you’re low on motivation.

By Melinda Wenner Moyer

There’s rarely enough time in the day to accomplish everything we set out to do, and exercise is often sacrificed when we’re short on time. Federal guidelines recommend fitting two and a half hours of moderate physical activity into our lives each week — and making time for muscle-strengthening exercises.

I sometimes find this guidance daunting, and I’m not alone. Only 25 percent of adults in the United States met those recommendations in 2020. So I grew curious about the research: How much physical activity does a person need to live longer and reduce their risk of chronic disease? How frequently do they actually need to work out?

Exploring the science and talking to researchers generated surprising information, like you don’t need to work out every day, and stretching doesn’t automatically prevent injuries.

Here are four research-based insights about exercise that might make you more excited to put on your workout clothes.

You can keep your workouts short.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise each week from activities like biking or swimming. That corresponds to just over 20 minutes a day. Still, you can benefit from doing less, said Dr. I-Min Lee, an epidemiologist who studies exercise at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The first 20 minutes of physical activity per session confer the most health perks, at least in terms of longevity, Dr. Lee said. As you continue working out, “the bang for your buck starts to decrease” in terms of tangible health rewards, she added.

A study published in March estimated that 111,000 lives could be saved each year if Americans over 40 added just 10 minutes per day to their current exercise regimen.

But what if you only have five or ten minutes to work out? Do it. “A lot of things happen in your body from the second you start to exercise,” said Carol Ewing Garber, a movement scientist at Columbia University Teachers College. And it’s possible to experience mental health benefits , including reduced anxiety and better sleep, immediately after a moderate-to-intense physical activity.

Your workouts don’t have to be intense.

If high-intensity interval training and hard core spin classes make you want to hide, don’t worry. You don’t have to sweat profusely or feel wrecked after a workout to reap some rewards.

Any physical activity that gets your heart beating a little faster is useful. If you’ve never tracked your heartbeat while exercising, it might be worth trying. For moderate exercise, the recommended target is roughly 50 to 70 percent of your body’s maximum heart rate. (To calculate your maximum heart rate, subtract your age from 220.) Many people will hit this target during a brisk walk, said Beth Lewis, a sport and exercise physiologist at the University of Minnesota.

Estimating your maximum heart rate can help you gauge how hard you should be walking, running or cycling. But it’s not perfect, since your natural heart rate during exercise may be higher or lower. Plus, the fitness levels and heart rates among people the same age can vary, and not all exercises raise your heart rate the same amount. Consider talking to your doctor before establishing your goals.

“Just moving your body in some way is going to be helpful,” Dr. Garber said. “That’s a really important message.”

Focus on overall health, not weight loss.

Many people exercise with weight loss in mind, but merely increasing physical activity usually isn’t effective. In a 2011 review of 14 published papers, scientists found that people with bigger bodies who did aerobic exercise for at least two hours a week lost an average of only 3.5 pounds over six months. And in a small 2018 clinical trial , women who did high-intensity circuit training three times a week didn’t see significant weight loss after eight weeks. (They did, however, gain muscle.)

Exercise improves your overall health, and studies suggest that it has a larger effect on life expectancy than body type. Regardless of your size, exercise reduces your risk of heart disease , some kinds of cancer , depression , type 2 diabetes , anxiety and insomnia , said Dr. Lewis.

It’s OK if you can only work out on weekends.

I’ve always assumed that the healthiest exercisers work out almost every day, but research suggests otherwise. In a study published in July, researchers followed more than 350,000 healthy American adults for an average of over 10 years. They found that people who exercised at least 150 minutes a week, over one or two days, were no more likely to die for any reason than those who reached 150 minutes in shorter, more frequent bouts. Other studies by Dr. Lee and her colleagues have drawn similar conclusions .

When it comes to potentially living longer, “it’s actually the total amount of activity per week that’s important,” Dr. Lee said. But, she added, if you work out more frequently, you’re less likely to get an exercise injury.

Stretching is optional.

Recommendations to stretch before and after workouts annoy me, especially if I’m pressed for time. But research suggests that stretching doesn’t actually reduce your risk of injury. “It used to be a required part of what you do — ‘If you don’t stretch, you’re going to get hurt,’” Dr. Lewis said. “That mentality is wrong.”

Instead of static stretching — doing things like touching your toes — Dr. Lewis recommends doing dynamic stretches before you exercise, such as gently swinging each leg forward and back while standing. Static stretching can, however, help increase muscle flexibility and joint mobility, she explained. But now I know not to worry if I don’t have time to do it.

After learning all of this, I’m less stressed by exercise guidelines — and more willing to move my body when I have a moment. Case in point: I’m traveling with extended family this week and have found it hard to schedule time for workouts. But yesterday I did some push-ups; today I walked a few blocks — and that, I now realize, is a lot better than nothing.

How to navigate the BA.5 surge when you’re sick of Covid

The latest Covid surge is a distressing reminder that the virus isn’t done with us. Knvul Sheikh and Hannah Seo offered clear guidance for lowering your risk of getting sick, including maxing out on vaccines and boosters, relying on your mask even during some outdoor events and keeping rapid tests on hand.

Read more: How to Live With Covid When You Are Tired of Living With Covid

Taste the rainbow? Not so fast.

A recent class-action lawsuit claimed that Skittles were “unfit for human consumption” because of the presence of a “known toxin” called titanium dioxide. The chemical compound is processed and used as a color additive, anti-caking agent and whitener, among other things, in thousands of food products across a range of categories. Rachel Rabkin Peachman explained what that means for our colorful candies.

Read more: A Lawsuit Claims Skittles Are Unfit for Consumption. Experts Weigh In.

The Week in Well

Here are some stories you don’t want to miss:

Christina Caron spoke to experts about the emotional toll of financial stress.

Colleen Stinchcombe offers a beginner’s guide to stand-up paddling.

Alice Callahan answers the question: Why do I sweat in my sleep?

Danielle Friedman looks into what Pilates can — and can’t — do for our workouts.

Let’s keep the conversation going. Follow me on Facebook or Twitter for daily check-ins, or write to me at [email protected] .

Let Us Help You Pick Your Next Workout

Looking for a new way to get moving we have plenty of options..

VO2 max has become ubiquitous in fitness circles. But what does it measure and how important is it to know yours?

Rising pollen counts make outdoor workouts uncomfortable and can affect performance. Here are five strategies for breathing easier.

Physical activity improves cognitive and mental health in all sorts of ways. Here’s why, and how to reap the benefits .

To develop a sustainable exercise habit, experts say it helps to tie your workout to something or someone .

Does it really matter how many steps you take each day? The quality of the steps you take might be just as important as the amount .

Is your workout really working for you? Take our quiz to find out .

Pick the Right Equipment With Wirecutter’s Recommendations

Want to build a home gym? These five things can help you transform your space into a fitness center.

Transform your upper-body workouts with a simple pull-up bar and an adjustable dumbbell set .

Choosing the best running shoes and running gear can be tricky. These tips make the process easier.

A comfortable sports bra can improve your overall workout experience. These are the best on the market .

Few things are more annoying than ill-fitting, hard-to-use headphones. Here are the best ones for the gym and for runners .

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Depression and anxiety: exercise eases symptoms.

Depression and anxiety symptoms often improve with exercise. Here are some realistic tips to help you get started and stay motivated.

When you have depression or anxiety, exercise often seems like the last thing you want to do. But once you get started and keep going, exercise can make a big difference.

Exercise helps prevent and improve many health problems, including high blood pressure, diabetes and arthritis. Research on depression, anxiety and exercise shows that the mental health and physical benefits of exercise also can help mood get better and lessen anxiety.

The links between depression, anxiety and exercise aren't entirely clear. But working out and other forms of physical activity can ease symptoms of depression or anxiety and make you feel better. Exercise also may help keep depression and anxiety from coming back once you're feeling better.

How does exercise help depression and anxiety?

Regular exercise may help ease depression and anxiety by:

- Releasing feel-good endorphins. Endorphins are natural brain chemicals that can improve your sense of well-being.

- Taking your mind off worries. Thinking about something else instead of worrying can get you away from the cycle of negative thoughts that feed depression and anxiety.

Regular exercise has many mental health and emotional benefits too. It can help you:

- Gain confidence. Meeting exercise goals or challenges, even small ones, can boost your self-confidence. Getting in shape also can make you feel better about how you look.

- Get more social interaction. Exercise and physical activity may give you the chance to meet or socialize with others. Just sharing a friendly smile or greeting as you walk around your neighborhood can help your mood.

- Cope in a healthy way. Doing something positive to manage depression or anxiety is a healthy coping strategy. Trying to feel better by drinking alcohol, dwelling on how you feel, or hoping depression or anxiety will go away on its own can lead to worsening symptoms.

Is a structured exercise program the only option?

Some research shows that physical activity such as regular walking — not just formal exercise programs — may help mood improve. Physical activity and exercise are not the same thing, but both are good for your health.

- Physical activity is any activity that works your muscles and requires energy. Physical activity can include work or household or leisure activities.

- Exercise is a planned, structured and repetitive body movement. Exercise can help people get physically fit or to stay fit.

The word "exercise" may make you think of running laps around the gym. But exercise includes a wide range of activities that boost your activity level to help you feel better.

Certainly running, lifting weights, playing basketball and other fitness activities that get your heart pumping can help. But so can physical activity such as gardening, washing your car, walking around the block or doing other less intense activities. Any physical activity that gets you off the couch and moving can boost your mood.

You don't have to do all your exercise or other physical activity at one time. Broaden how you think of exercise. Find ways to add small amounts of physical activity throughout your day. For example, take the stairs instead of the elevator. Park a little farther away from work to fit in a short walk. Or if you live close to your job, consider biking to work.

How much is enough?

For most healthy adults, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services exercise guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity a week. Or get at least 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity a week. You also can get an equal mix of the two types.

Aim to exercise most days of the week. But even small amounts of physical activity can be helpful. Being active for short periods of time, such as 10 to 15 minutes at a time, throughout the day can add up and have health benefits.

Regular exercise may improve depression or anxiety symptoms enough to make a big difference. That big difference can help kick-start further improvements. The mental health benefits of exercise and physical activity may last only if you stick with them over the long term. That's another good reason to find activities that you enjoy.

How do I get started — and stay with it?

Starting and sticking with an exercise routine or regular physical activity can be a challenge. These steps can help:

- Find what you enjoy doing. Figure out what type of physical activities you're most likely to do. Then think about when and how you'd be most likely to follow through. For example, would you be more likely to do some gardening in the evening, start your day with a jog, or go for a bike ride or play basketball with your children after school? Doing what you enjoy can help you stick with it.

- Get your healthcare professional's support. Talk to your healthcare professional or mental health professional for suggestions and support. Talk about an exercise program or physical activity routine and how it fits into your overall treatment plan.

- Set reasonable goals. Your mission doesn't have to be walking for an hour five days a week. Think realistically about what you may be able to do. Then begin slowly and build up over time. Make your plan fit your own needs and abilities rather than setting goals that you're not likely to meet.

- Don't think of exercise or physical activity as a chore. If exercise is just another "should" in your life that you don't think you're living up to, you'll think of it as a failure. Instead, look at your exercise or physical activity schedule the same way you look at your therapy sessions or medicine — as one of the tools to help you get better.

- Think about what keeps you from being successful. Figure out what's stopping you from being physically active or exercising. If you think about what's stopping you, you can probably find a solution. For example, if you feel self-conscious, you may want to exercise at home. If you stick to goals better with a partner, find a friend to work out with or who enjoys the same physical activities that you do. If you don't have money to spend on exercise gear, do something that's cost-free, such as regular walking.

- Prepare for setbacks and obstacles. Give yourself credit for every step in the right direction, no matter how small. If you skip exercise one day, that doesn't mean you can't keep up an exercise routine and might as well quit. Just try again the next day. Stick with it.

Do I need to see my healthcare professional?

Check with your doctor or other healthcare professional before starting a new exercise program to make sure it's safe for you. Talk about which activities, how much exercise and what intensity level is OK for you. Your healthcare professional can consider any medicines you take and your health conditions. You also can get helpful advice about getting started and staying on track.

If you exercise regularly but depression or anxiety symptoms still affect your daily living, see your healthcare professional or mental health professional. Exercise and physical activity are great ways to ease symptoms of depression or anxiety, but they don't replace talk therapy, sometimes called psychotherapy, or medicines.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Benefits of physical activity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm. Accessed Nov. 6, 2023.

- Bystritsky A. Complementary and alternative treatments for anxiety symptoms and disorders: Physical, cognitive, and spiritual interventions. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Nov. 6, 2023.

- Smith PJ, et al. The role of exercise in management of mental health disorders: An integrative review. Annual Review of Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060619-022943.

- Izquierdo M, et al. International exercise recommendations in older adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. Journal of Nutrition, Health, and Aging. 2021; doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1665-8.

- Getting started — Tips for long-term exercise success. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/getting-active/getting-started---tips-for-long-term-exercise-success. Accessed Nov. 6, 2023.

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/our-work/physical-activity/current-guidelines. Accessed Nov. 6, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Physical activity (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2021.

- Tips for starting physical activity. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/tips-get-active/tips-starting-physical-activity. Accessed Nov. 5, 2023.

- Roake J, et al. Sitting time, type, and context among long-term weight-loss maintainers. Obesity. 2021; doi:10.1002/oby.23148.

- Laskowski ER (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. June 16, 2021.

- Correia EM, et al. Analysis of the effect of different physical exercise protocols on depression in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Health. 2023; doi:10.1177/19417381231210286.

- Kung S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Dec. 9, 2023.

Products and Services

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- Addison's disease

- Adjustment disorders

- Adrenal fatigue: What causes it?

- Alzheimer's: New treatments

- Alzheimer's 101

- Understanding the difference between dementia types

- Alzheimer's disease

- Alzheimer's genes

- Alzheimer's drugs

- Alzheimer's prevention: Does it exist?

- Alzheimer's stages

- Ambien: Is dependence a concern?

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Antidepressants and pregnancy

- Atypical antidepressants

- Binge-eating disorder

- Blood Basics

- Borderline personality disorder

- Breastfeeding and medications

- Dr. Wallace Video

- Dr. Mark Truty (surgery, MN) better outcomes with chemo

- Can zinc supplements help treat hidradenitis suppurativa?

- Hidradenitis suppurativa wound care

- Celiac disease

- Child abuse

- Chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- CJD - Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Clinical trials for hidradenitis suppurativa

- Coconut oil: Can it cure hypothyroidism?

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Complicated grief

- Compulsive sexual behavior

- Concussion in children

- Concussion Recovery

- Concussion Telemedicine

- Coping with the emotional ups and downs of psoriatic arthritis

- Coping with the stress of hidradenitis suppurativa

- COVID-19 and your mental health

- Creating a hidradenitis suppurativa care team

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- Cushing syndrome

- Cyclothymia (cyclothymic disorder)

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Depression during pregnancy

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- Diabetes and depression: Coping with the two conditions

- Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Did the definition of Alzheimer's disease change?

- Dissociative disorders

- Vitamin C and mood

- Drug addiction (substance use disorder)

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Fibromyalgia

- HABIT program orientation

- Hashimoto's disease

- Hidradenitis suppurativa

- Hidradenitis suppurativa and biologics: Get the facts

- Hidradenitis suppurativa and diet: What's recommended?

- Hidradenitis suppurativa and sleep: How to get more zzz's

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: Tips for weight-loss success

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: What is it?

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: When does it appear?

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: Where can I find support?

- How opioid use disorder occurs

- How to tell if a loved one is abusing opioids

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Hypothyroidism: Can calcium supplements interfere with treatment?

- Hypothyroidism diet

- Hypothyroidism and joint pain?

- Hypothyroidism: Should I take iodine supplements?

- Hypothyroidism symptoms: Can hypothyroidism cause eye problems?

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid)

- Insomnia: How do I stay asleep?

- Insomnia treatment: Cognitive behavioral therapy instead of sleeping pills

- Intervention: Help a loved one overcome addiction

- Is depression a factor in rheumatoid arthritis?

- Kratom for opioid withdrawal

- Lack of sleep: Can it make you sick?

- Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease

- Living better with hidradenitis suppurativa

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- Managing Headaches

- Managing hidradenitis suppurativa: Early treatment is crucial

- Hidradenitis suppurativa-related health risks

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Marijuana and depression

- Mayo Clinic Minute: 3 tips to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Alzheimer's disease risk and lifestyle

- Mayo Clinic Minute: New definition of Alzheimer's changes

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Prevent migraines with magnetic stimulation

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Restless legs syndrome in kids

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Weathering migraines

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Women and Alzheimer's Disease

- Medication overuse headaches

- Memory loss: When to seek help

- Mental health: Overcoming the stigma of mental illness

- Mental health providers: Tips on finding one

- Mental health

- Mental illness

- What is a migraine? A Mayo Clinic expert explains

- Migraine medicines and antidepressants

- Migraine FAQs

- Migraine treatment: Can antidepressants help?

- Migraines and gastrointestinal problems: Is there a link?

- Migraines and Vertigo

- Migraines: Are they triggered by weather changes?

- Alleviating migraine pain

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

- Mindfulness exercises

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- New Alzheimers Research

- Nicotine dependence

- Occipital nerve stimulation: Effective migraine treatment?

- Ocular migraine: When to seek help

- Opioid stewardship: What is it?

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

- Pancreatic cancer

- Pancreatic Cancer

- What is pancreatic cancer? A Mayo Clinic expert explains

- Infographic: Pancreatic Cancer: Minimally Invasive Surgery

- Pancreatic Cancer Survivor

- Infographic: Pancreatic Cancers-Whipple

- Perimenopause

- Pituitary tumors

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Poppy seed tea: Beneficial or dangerous?

- Post COVID syndrome

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

- Prescription drug abuse

- Prescription sleeping pills: What's right for you?

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Psychotherapy

- Reducing the discomfort of hidradenitis suppurativa: Self-care tips

- Restless legs syndrome

- Salt craving: A symptom of Addison's disease?

- Schizoaffective disorder

- Seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

- Seasonal affective disorder treatment: Choosing a light box

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Sleep disorders

- Soy: Does it worsen hypothyroidism?

- Staying active with hidradenitis suppurativa

- Stress symptoms

- Sundowning: Late-day confusion

- Support groups

- Surgery for hidradenitis suppurativa

- Symptom Checker

- Tapering off opioids: When and how

- Tianeptine: Is safe use possible?

- Tinnitus and antidepressants

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- Traumatic brain injury

- Treating hidradenitis suppurativa: Explore your options

- Treating hidradenitis suppurativa with antibiotics and hormones

- Treatment of parathyroid disease at Mayo Clinic

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

- Unexplained weight loss

- Vagus nerve stimulation

- Valerian: A safe and effective herbal sleep aid?

- Vascular dementia

- Video: Alzheimer's drug shows early promise

- Video: Vagus nerve stimulation

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

- What are opioids and why are they dangerous?

- What are the signs and symptoms of hidradenitis suppurativa?

- Wilson's disease

- Young-onset Alzheimer's

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Do not share pain medication

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Avoid opioids for chronic pain

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Be careful not to pop pain pills

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Depression and anxiety Exercise eases symptoms

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- Terms of Use

- Privacy policy

- Why Trust Us?

41 Exercise Statistics: The Latest Fitness Trends (In 2024)

Only one in five US adults exercise every day, with walking being the most popular way to stay fit. In this article you can learn more about who exercises most, plus you’ll discover the fittest state and the global challenge to get more people moving.

Fitness Statistics (Top Picks)

How many americans exercise each day, what is the most popular type of exercise, what is the most popular group exercise, what percentage of the us is obese, what percentage of americans use fitness apps, what is the size of the fitness industry in the us, why do people not exercise, who exercises more, males or females, who is most likely to go to the gym, how many children exercise in the us, which ethnic group exercises the most, which state works out the most, which state has the least amount of exercise, how big is the at home fitness industry, how many people work out at home vs the gym, what percentage of the world does not exercise, what is the fittest country, which country exercises the least, time to get physical.

- Just one in five US adults exercise each day.

- The US gym, health and fitness club market is estimated to be worth $32 billion.

- More men meet the national standards for exercise , 26.3% vs 18.8%.

- People aged between 18 and 34 years old are the most likely to be gym goers.

- More than three quarters of children in the US are active for less than the recommended 60 minutes each day.

- Colorado is the US state that exercises the most , with the population of Mississippi working out the least .

- The home fitness market in the US is valued at $11.3 billion , and growing year on year.

- 1 in 4 adults around the world don’t meet the globally recommended physical activity levels .

2023 Fitness and Exercise Statistics

Data from Statista reveals that just one in five US adults exercise each day.

In fact, only 23% of US adults get the recommended amount of aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity each week.

Focusing on aerobic exercise only , the results are a little more encouraging, with 53.3% meeting the recommendation.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adults should do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity each week, as well muscle-strengthening activities.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, walking is the most popular type of exercise .

30% of active adults choose walking , with weightlifting and using cardiovascular equipment, such as a treadmill or rowing machine , not far behind.

Yoga is the most popular form of group exercise in the US.

The latest yoga statistics reveal that 10% of the US population practice yoga , with yoga growing in popularity by 63.8% between 2010 and 2021.

- 42.4% of adults across the United States are classed as obese.

Information gathered from the National Health and Nutrition Examination found that nearly 1 in 3 adults in the US are classed as overweight , with 9.2% of the population having severe obesity .

86.3 million adults in the US use a health or fitness app.

This has grown by 38% since 2018, when the number was just 62.7 million.

The gym, health and fitness club market in the US is estimated to be worth $32 billion .

It has declined 4% per year on average since 2017.

A lack of time and motivation were the top reasons given in a OnePoll study into why Americans don’t exercise more.

Being too tired and having too much work to do topped the poll of why adults in the US skip planned workouts .

2023 Fitness and Exercise Key Statistics:

- Just 19.3% of the US adult population exercise each day.

- Walking is the most popular type of exercise, with yoga being the most popular form of group exercise.

- 25% of adults in the US regularly use a health and fitness app.

- A lack of time most common reason given for not exercising.

Sources: Statista | CDC | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics | Club Industry | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | Statista | IBIS World | NY Post

Fitness Demographics Statistics

26.3% of men meet the national standards for exercise, compared to only 18.8% of women .

Researchers at Seattle Pacific University found that men exercise more for enjoyment , whereas women report exercising for weight loss and toning.

Women aged between 18 and 34 years old are the most likely to go to the gym.

Those in the 18-34 year old age group make up 60% of the gym community , with women very slightly bigger gym-goers than men at 50.5%.

Just 24% of children under the age of 17 meet the CDC’s Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans .

This concerning fact about exercise shows that more than three quarters of children participate in less than the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity each day.

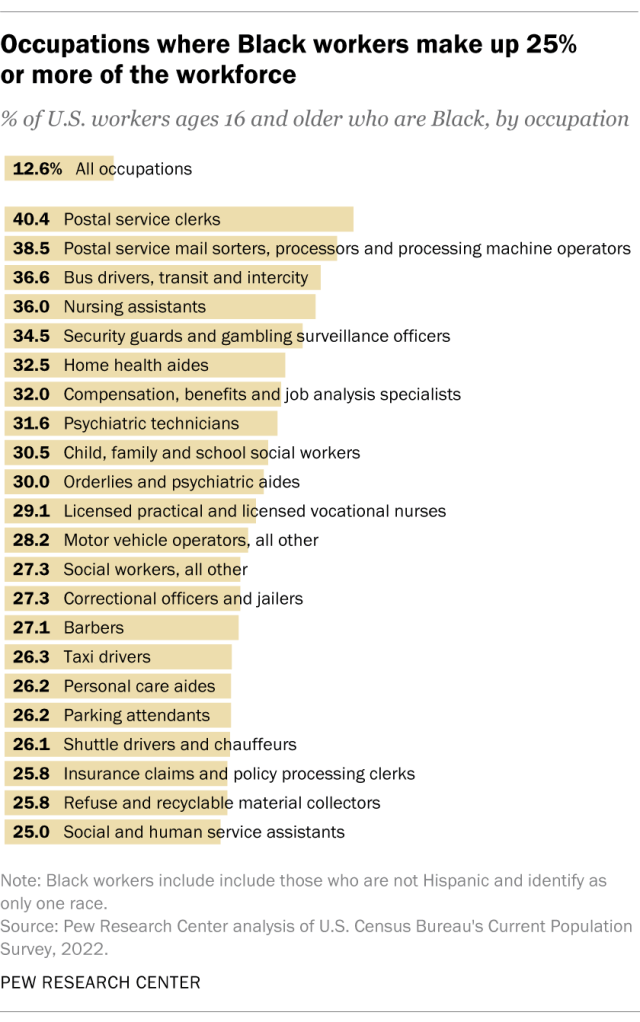

According to data compiled by Statista, Asian Americans and Non-Hispanic Whites are the most physically active ethnic groups in the United States.

The hispanic population record the highest rate of physical inactivity , with 30.6% of this ethnic group reporting a sedentary lifestyle .

Fitness Demographics Key Statistics:

- 26.3% of men meet the national standards for exercise , compared to 18.8% of women.

- People aged between 18 and 34 years old are the age group most likely to go to the gym.

- 76% of children in US don’t meet the recommended daily standard for exercise.

- 30.6% of the hispanic population in the United States report a sedentary lifestyle.

Sources: Finances Online | Medium | National Library of Medicine | CDC | Statista

Fitness Statistics by State

Colorado is the state that works out the most, with 32.5% of the population meeting the national exercise guidelines.

Idaho (31.4%), New Hampshire (30.7%) and Washington D.C. (30.7%) also record having an active population.

Mississippi is that state that has the least amount of exercise , with only 13.5% of the population meeting the national exercise guidelines.

Kentucky (14.6%), South Carolina (14.8%) and Indiana (15.1%) also record lower levels of exercise.

Key Statistics:

- Nearly one-third of the population of Colorado report higher levels of exercise, making it the most active state.

- Just 13.5% of people in Mississippi meet the national exercise guidelines, making it the least active state.

Sources: CBS News

Home Fitness Industry Statistics

The home fitness market in the US was valued at $11.3 billion in 2021 . It’s expected to grow to $17.80 billion by 2030 .

This estimate includes the profits of companies such as Lululemon, a trusted brand for workout clothing, equipment and fitness gifts .

Two in three active people in the US report working out at home , with the remaining third attending a gym.

The confidence to try new fitness activities and the ability to fit their routine around family life , were two of the top reasons given for preferring an at home workout.

72% of adults preferred the flexibility of online fitness classes in particular, allowing them to step away from the commitment of a gym membership.

In fact, the demand for virtual fitness classes is growing year on year , with experts predicting the market will grow by an amazing 35% each year until 2026 .

Changes in the way people exercise has been directly influenced by the pandemic, in fact during 2020 it is thought that nearly a quarter of all gyms in the US closed their doors.

Home Fitness Industry Key Statistics:

Sources: Study Finds | Globe Newswire | Run Repeat | Run Repeat

Global Fitness Statistics

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1 in 4 adults don’t meet the globally recommended physical activity levels.

They believe up to five million premature deaths could be avoided each year if the global population was more active.

The WHO guidelines recommend adults should do at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous aerobic activity each week.

According to a 2021 global study, the Netherlands has the fittest population.

They spend, on average, more than 12 hours each week exercising or playing sport.

- Brazil has the least physically active population.

They spend, on average, three hours per week on physical activity, compare this to The Netherlands who spend more than 12 hours.

Global Fitness Key Statistics:

- According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 4 adults around the world don’t exercise enough.

- Five million premature deaths could be avoided if the global population was more active.

- The Netherlands has the most physically active population.

Sources: United Nations | World Economic Forum | Ipsos

Want to learn more about the fitness industry in the US?

Here at The Good Body we’ve curated a round up of all the most fascinating Physical Therapy statistics , a few of which might surprise you…

Laura Smith

Associate Editorial Manager

Specialist health & wellbeing writer, passionate about discovering new technologies & sharing the latest research.

Related Articles

14 Fascinating Fitness Facts

July 28, 2023

10 of the Best Fitness Instagram Accounts and Influencers to Motivate You Today!

June 10, 2022

64 Fitness Quotes to Power Your Next Workout!

February 14, 2023

50 Fitness Affirmations to Get You Moving!

October 19, 2023

41 Yoga Statistics: How Many People Practice Yoga?

September 26, 2023

The Good Body is committed to delivering in-depth research, case studies and product reviews to help you live a healthier and happier life.

More From The Good Body

- About The Good Body

- Contact Page

Send us an email: [email protected] Or follow us on social media:

Copyright ©2024 The Good Body | All Rights Reserved. TheGoodBody.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com. Other affiliate programs may also be represented.

- Cookie policy

- Modern Slavery Statement

- Accessibility

- Editorial Policy

- Terms & conditions

Workout Supplements

A popular category of dietary supplements are workout supplements, which are typically taken before (‘pre-workout’) or after exercising (‘post-workout’), and are sold in a variety of forms from pills to powders and ready-to-drink shakes. The global pre-workout supplement market size alone was estimated to reach $13.98 billion in 2020 and almost double in size to $23.77 billion by 2027. [2]

Fitness gurus and blogs touting these products as crucial for peak performance, fat loss, and explosive muscle growth in combination with complicated scientific-sounding names and labels might have you believing you can’t effectively exercise without them. But do these supplements live up to the hype, and are they even necessary—or in some cases, safe? Like other dietary supplements in the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not review workout supplements for safety or effectiveness before they are sold to consumers. It’s a good idea to research their effects and ingredients and consult with your physician before adding them to your fitness routine.

What happens to the body during physical activity?

Here we review the scientific evidence behind some of the most popular ingredients in workout supplements.

Pre-Workout Supplements

Pre-workout supplements are designed to provide energy and aid endurance throughout a workout. They are typically taken 15-30 minutes before a workout, but can also be consumed during exercise. Below are common ingredients found in pre-workout supplements that the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine have highlighted as having evidence-based uses in sports nutrition. [3] These supplements have also been categorized as apparently safe and having strong evidence to support efficacy by the International Society of Sports Nutrition. [4] However, it is important to consult a physician or dietitian before using these supplements, as they are not reviewed by the FDA for safety or effectiveness.

Beta-Alanine

Beta-alanine is an amino acid that is produced in the liver and also found in fish, poultry, and meat. When dosed at 4–6g/day for 2–4 weeks, this supplement has been shown to improve exercise performance, particularly for high-intensity exercise lasting 1–4 minutes, such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or short sprints. It has also been shown to reduce neuromuscular fatigue, particularly in older adults. [5] How does it work? During exercise the body breaks down glucose into lactic acid, which is then converted into lactate. This produces hydrogen ions, which lower muscle pH levels. This acidity reduces muscles’ ability to contract, causing fatigue. [6] Beta-alanine increases muscle concentrations of carnosine, which is a proton buffer that reduces muscle acidity during high-intensity exercise, which in turn reduces overall fatigue. [5] This supplement is often combined with sodium bicarbonate, or baking soda, which also reduces muscle acidity. A common side effect of beta-alanine supplementation is paresthesia, or a skin tingling sensation, [3] but this effect can be attenuated by taking lower doses (1.6g) or using a sustained-release instead of a rapid-release formula. [5] In short, this supplement can help you exercise at high-intensity for a longer period of time, which could potentially lead to increased muscle mass. The International Society of Sports Nutrition has asserted that “beta-alanine supplementation currently appears to be safe in healthy populations at recommended doses,” but it is important to consult with your doctor before beginning supplementation.

Caffeine is a stimulant that is often included in pre-workout supplements, as it has been shown to benefit athletic performance for short-term high intensity exercise and endurance-based activities. [7] It is important to understand that these studies have been conducted with Olympic and competition athletes, and thus the average individual who exercises recreationally should consult with a doctor before using caffeine as a supplement. For high performance athletes, the International Olympic Committee recommends 3–6mg caffeine/kg of body weight consumed an hour before exercise. [7,8] Evidence also suggests that lower caffeine doses (up to 3mg/kg body weight, ~200 mg) taken before and during prolonged exercise can increase athletic performance. [9,10] Mechanistically, caffeine increases endorphin release, improves neuromuscular function, vigilance, and alertness, and reduces perception of exertion during exercise. [10,11] Despite some benefits from smaller doses, larger doses of caffeine (>=9mg/kg of body weight) have not been shown to increase performance, and may induce nausea, anxiety, and insomnia. [11] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers 400 milligrams of caffeine to be a safe amount for daily consumption, but some pre-workout supplements may exceed this amount in a single serving or fail to disclose the amount of caffeine they contain, so it is important to always review the label of any supplement before consumption. Caffeine powder is also marketed as a stand-alone pre-workout supplement, but the FDA has advised against using this product, as even very small amounts may cause accidental overdose. Powdered caffeine has been linked to numerous deaths—a single tablespoon (10 grams) is a lethal dose for an adult, but the product is often sold in 100-gram packages. [12]

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound found in skeletal muscle that is synthesized in the body from amino acids and can be obtained from red meat and seafood . In the body, it helps produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which provides energy for muscles. Creatine is a popular workout supplement marketed to increase athletic performance, especially for weight training. Research suggests that creatine supplementation increases muscle availability of creatine, which in turn can enhance exercise capacity and training adaptations in adolescents, younger adults, and older adults. [13] Specifically, these adaptations allow for individuals to increase training volume (e.g., the ability to perform more repetitions with the same weight), which in turn can lead to greater increases in lean mass and muscular strength and power. [14-16] Although the exact mechanisms through which creatine improves performance have not been identified with certainty, various theories have been investigated, including the potential for creatine to stimulate muscle glycogen levels. [17,14] Creatine supplementation is primarily recommended for athletes who engage in power/strength exercises (e.g., weight lifting), or for athletes who engage in sports involving intermittent sprints and other brief repeated high-intensity exercises (e.g., soccer, basketball). [13] The International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends an initial dosage of 5g of creatine monohydrate (~0.3g/kg body weight) four times daily for 5–7 days to increase muscle creatine stores; once muscle creatine stores are fully saturated, stores can be maintained by ingesting 3–5 g/day. [13] Many powdered creatine supplements recommend this regimen in the directions on their packages. The Society also notes that an alternative supplementation protocol is to ingest 3g/day of creatine monohydrate for 28 days. [13] While the scientific literature has generally found supplementation to be safe at these levels, [18] creatine may not be appropriate for people with kidney disease or those with bipolar disorder. It is important to consult a doctor before taking this supplement. Of note, creatine supplementation has been shown to increase total body water, which causes weight gain that could be detrimental to performance in which body mass is a factor, such as running. [14] The International Society of Sports Nutrition, the American Dietetic Association, and the American College of Sports Medicine have all published statements supporting creatine supplementation as an effective way of increasing high-intensity exercise capacity and lean body mass during training for high-performance athletes. [19-21;3]

Post-Workout Supplements

A variety of post-workout supplements are marketed to consumers to increase muscle mass through enhanced muscle repair, recovery, and growth. Below is a review of some of the most common ingredients in post-workout supplements.

Carbohydrates

Replenishing glycogen stores after a workout with sufficient carbohydrate intake is important for muscle recovery, and beginning the next workout with sufficient muscle glycogen stores has been shown to improve exercise performance. [22-24] However, normal dietary intake is typically sufficient to restore muscle glycogen stores after low-intensity exercises, such as walking , yoga, or tai chi (3–5 g carbohydrate/kg body weight per day), and even for moderate-intensity exercise, such as one hour or more of walking, jogging, swimming, or bicycling at modest effort (5–7 g carbohydrate/kg body weight per day). [24] Post-workout supplementation with carbohydrates and protein within 24–36 hours is only recommended following strenuous physical activity, which includes one hour or more of vigorous exercise such as interval training, running, swimming, bicycling, soccer, or basketball at a moderate to intense effort (where one can only carry on brief conversations or cannot speak); in this case, 6–12 g carbohydrates/kg body weight per day is recommended to be consumed after exercise to fully restore muscle glycogen stores. [24]

Recommended levels of daily protein intake for the general population (0.8 grams of protein for every kilogram of body weight, or about 7 grams of protein every day for every 20 pounds of body weight) are estimated to be sufficient to meet the needs of nearly all healthy adults. [25] Recommendations for protein supplementation during exercise vary based on the type of exercise being conducted: endurance training (e.g., long-distance bicycling) or resistance training (e.g., weight lifting). Very few studies have investigated the effects of prolonged protein supplementation on endurance exercise performance. A review conducted by the International Society of Sports Nutrition found that protein supplementation in the presence of adequate carbohydrate intake does not appear to improve endurance performance, but may reduce markers of muscle damage and feelings of soreness. [26] On the other hand, individuals who engage in high-intensity resistance training may benefit from increased protein consumption to optimize muscle protein synthesis required for muscle recovery and growth, but research is inconclusive, with the majority of studies investigating the effects of protein supplementation on maximal strength enhancement finding no benefit. [26] The extent to which protein supplementation may aid resistance athletes is highly contingent on a variety of factors, including intensity and duration of training, individual age, dietary energy intake, and quality of protein intake. For individuals engaging in strenuous exercise to build and maintain muscle mass, the International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends an overall daily protein intake of 1.4–2.0 g/kg of body weight/day. [26] This can be ingested in the form of protein foods or protein powder.

Spotlight on protein powder

Some sources of protein supplements:

- Casein and whey are proteins found in cow’s milk ; roughly 80% of milk proteins are casein, while the other ~20% are whey. [28] Both proteins should be avoided by people who have trouble digesting dairy. Casein and whey contain all essential amino acids and are easily absorbed by the body, but their speed of absorption differs. [29,30] Whey protein is water soluble and rapidly metabolized into amino acids. Casein, on the other hand, is not soluble in water and is digested more slowly than whey—when ingested, it forms a clotted gel in the stomach that provides a sustained slow release of amino acids into the bloodstream over several hours. [31] Studies examining protein supplementation for resistance training suggest that whey’s faster digestion could be beneficial for gains in skeletal muscle mass compared to casein in both young men and in trained bodybuilders. [32,33] Another study, however, found that both proteins resulted in increased amino acid concentrations in the body compared to a placebo, with no significant differences between casein and whey for amino acid uptake or muscle protein balance. [34] Due to casein’s slower rate of absorption, it is often touted on health blogs as being useful for weight loss because it could hypothetically promote fullness, especially if ingested before periods of fasting, such as before bed. However, multiple studies have found no clear evidence that casein is more effective than any other protein source for satiety or weight loss. [35,36]

- Soy protein powder is derived from soybeans , and unlike many plant-based proteins, it contains adequate levels of all essential amino acids. It is a common alternative to milk protein for vegans or people with dairy sensitivities or allergies. Soy protein is absorbed fairly rapidly by the body, although it is not as bioavailable as animal-based proteins. One study found that soy protein promoted muscle protein synthesis significantly more than casein protein when consumed by healthy young men at rest and after leg resistance exercise, but that soy protein was inferior to whey protein in increasing muscle protein synthesis. [32] A review of studies on milk- and soy-based protein supplementation also found that whey protein was better able to support muscle protein synthesis compared to soy protein in younger and older adults. [37]

- Pea protein powder is made from yellow split peas, and can be an option for vegans or people with allergies or sensitivities to soy or dairy. Pea protein is rich in eight of the nine essential amino acids; it is low in methionine, which can be obtained from other sources including rice and animal proteins. There is limited research on the effects of pea protein. One double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study found that men aged 18 to 35 years who ingested 50 grams of pea protein daily in combination with a resistance training program over 12 weeks experienced similar increases in muscle thickness compared to those who ingested the same amount of whey protein daily. [38] However, all participants experienced similar increases in muscle strength, with no significant difference between those who supplemented with pea protein, whey protein, or a placebo.

- Hemp protein powder is derived from the seeds of the hemp plant. Although there is little research on the use of hemp protein powder as a workout supplement, it contains omega-3 fatty acids and a number of essential amino acids. However, it is not a complete protein, as it has relatively low levels of lysine and leucine. [39,40]

Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs)

Three out of the nine essential amino acids have a chemical structure involving a side-chain with a “branch”, or a central carbon atom bound to three or more carbon atoms. These three amino acids, leucine, isoleucine, and valine, are called branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). They can be obtained from protein-rich foods such as chicken, red meat, fish , and eggs , and are also sold as dietary supplements in powdered form. BCAAs are key components of muscle protein synthesis, [41] and research has shown that leucine in particular drives protein synthesis and suppresses protein breakdown. [42-43] Although short-term mechanistic data suggests that leucine plays an important role in muscle protein synthesis, [44] longer-term trials do not support BCAAs as useful workout supplements. For example, a trial of leucine supplementation during an 8-week resistance training program did not result in increased muscle mass or strength among participants. [45] Studies have generally failed to find performance-enhancing effects of BCAAs such as accelerated repair of muscle damage after exercise. [46]

Another reason to be cautious of a high intake of BCAAs is its potentially negative effect on glucose metabolism and diabetes. BCAAs, particularly leucine, can disrupt the normal action of insulin, a hormone that regulates blood glucose. In an epidemiological study composed of three large cohorts of men and women followed for up to 32 years, a higher intake of BCAAs (obtained mainly from meats) was associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. [47]

Chocolate Milk

Although you may not think of it as a “supplement,” a number of pro athletes have begun to promote chocolate milk as an ideal post-workout beverage due to its combination of protein, carbohydrates, water, and electrolytes (in the form of sodium and calcium). A review of the effects of chocolate milk on post-exercise recovery found that chocolate milk provided similar or superior results compared to water or other sports drinks, [48] while another review found that low-fat chocolate milk was an effective supplement to spur protein synthesis and glycogen regeneration. [49] However, the authors noted that evidence is limited and high-quality clinical trials with larger sample sizes are warranted. Of note, many studies of chocolate milk as a post-workout supplement are sponsored by the dairy industry, which may introduce bias. Chocolate milk generally contains high amounts of added sugars and saturated fat, and is likely most useful for athletes conducting high-intensity exercise for multiple hours a day, such as professional swimmers competing in the Olympics. However, for most individuals conducting moderate-intensity physical activity, such as an hour of jogging or bicycling, water is a healthier alternative as a post-workout beverage.

Electrolytes