Module 11: Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

Case studies: schizophrenia spectrum disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify schizophrenia and psychotic disorders in case studies

Case Study: Bryant

Thirty-five-year-old Bryant was admitted to the hospital because of ritualistic behaviors, depression, and distrust. At the time of admission, prominent ritualistic behaviors and depression misled clinicians to diagnose Bryant with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Shortly after, psychotic symptoms such as disorganized thoughts and delusion of control were noticeable. He told the doctors he has not been receiving any treatment, was not on any substance or medication, and has been experiencing these symptoms for about two weeks. Throughout the course of his treatment, the doctors noticed that he developed a catatonic stupor and a respiratory infection, which was identified by respiratory symptoms, blood tests, and a chest X-ray. To treat the psychotic symptoms, catatonic stupor, and respiratory infection, risperidone, MECT, and ceftriaxone (antibiotic) were administered, and these therapies proved to be dramatically effective. [1]

Case Study: Shanta

Shanta, a 28-year-old female with no prior psychiatric hospitalizations, was sent to the local emergency room after her parents called 911; they were concerned that their daughter had become uncharacteristically irritable and paranoid. The family observed that she had stopped interacting with them and had been spending long periods of time alone in her bedroom. For over a month, she had not attended school at the local community college. Her parents finally made the decision to call the police when she started to threaten them with a knife, and the police took her to the local emergency room for a crisis evaluation.

Following the administration of the medication, she tried to escape from the emergency room, contending that the hospital staff was planning to kill her. She eventually slept and when she awoke, she told the crisis worker that she had been diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) a month ago. At the time of this ADHD diagnosis, she was started on 30 mg of a stimulant to be taken every morning in order to help her focus and become less stressed over the possibility of poor school performance.

After two weeks, the provider increased her dosage to 60 mg every morning and also started her on dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets (10 mg) that she took daily in the afternoon in order to improve her concentration and ability to study. Shanta claimed that she might have taken up to three dextroamphetamine sulfate tablets over the past three days because she was worried about falling asleep and being unable to adequately prepare for an examination.

Prior to the ADHD diagnosis, the patient had no known psychiatric or substance abuse history. The urine toxicology screen taken upon admission to the emergency department was positive only for amphetamines. There was no family history of psychotic or mood disorders, and she didn’t exhibit any depressive, manic, or hypomanic symptoms.

The stimulant medications were discontinued by the hospital upon admission to the emergency department and the patient was treated with an atypical antipsychotic. She tolerated the medications well, started psychotherapy sessions, and was released five days later. On the day of discharge, there were no delusions or hallucinations reported. She was referred to the local mental health center for aftercare follow-up with a psychiatrist. [2]

Another powerful case study example is that of Elyn R. Saks, the associate dean and Orrin B. Evans professor of law, psychology, and psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the University of Southern California Gould Law School.

Saks began experiencing symptoms of mental illness at eight years old, but she had her first full-blown episode when studying as a Marshall scholar at Oxford University. Another breakdown happened while Saks was a student at Yale Law School, after which she “ended up forcibly restrained and forced to take anti-psychotic medication.” Her scholarly efforts thus include taking a careful look at the destructive impact force and coercion can have on the lives of people with psychiatric illnesses, whether during treatment or perhaps in interactions with police; the Saks Institute, for example, co-hosted a conference examining the urgent problem of how to address excessive use of force in encounters between law enforcement and individuals with mental health challenges.

Saks lives with schizophrenia and has written and spoken about her experiences. She says, “There’s a tremendous need to implode the myths of mental illness, to put a face on it, to show people that a diagnosis does not have to lead to a painful and oblique life.”

In recent years, researchers have begun talking about mental health care in the same way addiction specialists speak of recovery—the lifelong journey of self-treatment and discipline that guides substance abuse programs. The idea remains controversial: managing a severe mental illness is more complicated than simply avoiding certain behaviors. Approaches include “medication (usually), therapy (often), a measure of good luck (always)—and, most of all, the inner strength to manage one’s demons, if not banish them. That strength can come from any number of places…love, forgiveness, faith in God, a lifelong friendship.” Saks says, “We who struggle with these disorders can lead full, happy, productive lives, if we have the right resources.”

You can view the transcript for “A tale of mental illness | Elyn Saks” here (opens in new window) .

- Bai, Y., Yang, X., Zeng, Z., & Yang, H. (2018). A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. BMC psychiatry , 18(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1655-5 ↵

- Henning A, Kurtom M, Espiridion E D (February 23, 2019) A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Cureus 11(2): e4126. doi:10.7759/cureus.4126 ↵

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- A tale of mental illness . Authored by : Elyn Saks. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6CILJA110Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- A Case Study of Acute Stimulant-induced Psychosis. Authored by : Ashley Henning, Muhannad Kurtom, Eduardo D. Espiridion. Provided by : Cureus. Located at : https://www.cureus.com/articles/17024-a-case-study-of-acute-stimulant-induced-psychosis#article-disclosures-acknowledgements . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Elyn Saks. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elyn_Saks . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- A case report of schizoaffective disorder with ritualistic behaviors and catatonic stupor: successful treatment by risperidone and modified electroconvulsive therapy. Authored by : Yuanhan Bai, Xi Yang, Zhiqiang Zeng, and Haichen Yangcorresponding. Located at : https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5851085/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

Case study: treatment-resistant schizophrenia

WELLCOME CENTRE HUMAN NEUROIMAGING/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Learning objectives

After reading this article, individuals should be able to:

- Describe the management of schizophrenia;

- Understand pharmaceutical issues that occur during treatment with antipsychotics, especially clozapine ;

- Explain how the Mental Health Act 1983 impacts on care;

- Understand the importance of multidisciplinary and patient-centred care in managing psychosis.

Around 0.5–0.7% of the UK population is living with schizophrenia. Of these individuals, up to one-third are classified as treatment-resistant. This is defined as schizophrenia that has not responded to two different antipsychotics [1,2] .

Clozapine is the most effective treatment for such patients [3] . It is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)[4], and is the only licensed medicine for this patient group [4,5] . For treatment-responsive patients, there should be a collaborative approach when choosing a treatment [4] . More information on the recognition and management of schizophrenia can be found in a previous article here , and in accompanying case studies here .

This case study aims to explore a patient’s journey in mental health services during a relapse of schizophrenia. It also aims to highlight good practice for communicating with patients with severe mental illness in all settings, and in explaining the role of clozapine.

Case presentation

Mr AT is a male, aged 26 years, who has been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. He moved to the UK with his family from overseas five years ago. He lives with his parents in a small flat in London. His mother calls the police after he goes missing, finding his past two months’ medication untouched.

He is found at an airport, attempting to go through security without a ticket. He is confused and paranoid about the police asking him to come with them.

He is taken to A&E and is medically cleared (see Box 1) [6] .

Box 1: Common differentials for psychotic symptoms

Medical conditions can present as psychosis. These include:

- Intoxication/effects of drugs (cannabis, stimulants, opioids, corticosteroids);

- Cerebrovascular disease;

- Temporal lobe epilepsy.

Mr AT’s history is taken by a psychiatrist, and his crisis plan sought (as per NICE recommendations) but he does not have one [7] .

He has been under the care of mental health services for two years and disputes his diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. He was admitted to a psychiatric hospital 18 months ago where he was prescribed the antipsychotic amisulpride at 600mg daily.

He is teetotal, smokes ten cigarettes a day and smokes cannabis every day. His BMI is 26 and he has hypercholesterolaemia (total cholesterol = 6.1mmol/L, reference range <5mmol/L) but all other tests are normal.

He has no allergies. His only medication is amisulpride 600mg each morning, which he does not take.

Medicines reconciliation

Mr AT is transferred to a psychiatric ward and placed under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act , allowing detention for up to 28 days for assessment and treatment (see Box 2).

Box 2: The Mental Health Act 1983

This legislation allows for the detention and treatment of patients with serious mental illness, where urgent care is required. This is often referred to as “sectioning”.

It includes regulations about treatment against a patient’s consent to safeguard patients’ liberty, which become more stringent with longer detentions.

Patients may only be given medication to treat their mental illness without their consent and may refuse physical health treatment.

He denies any mental illness and tells the team they are conspiring with MI6. He is visibly experiencing auditory hallucinations: seen by him talking to himself and looking to empty corners of the room. Amisulpride is re-prescribed at 300mg, which he declines to take.

A pharmacy technician completes a medicines reconciliation and contacts the care coordinator. The technician provides information about Mr AT’s treatment and feels he is still unwell as he has continued to express paranoid beliefs about his neighbours and MI6.

The ward pharmacist speaks to the patient. As per NICE guidance on medicines adherence , they adopt a non-judgemental attitude [8] . Mr AT is provided with information on the benefits and side effects of the medication and is asked open questions regarding his reluctance to take it. For more information on non-adherence to medicines and mental illness, see Box 3 [9] .

Box 3: Medicines adherence and mental health

Adherence to medication is similar for both physical and mental health medicines: only about 50% of patients are adherent.

Side effects and lack of involvement in decision making often lead to poor adherence.

In mental illness, other factors are:

- Denial of illness (poor ‘insight’);

- Lack of contact by services;

- Cultural factors, such as family, religious or personal beliefs around mental illness or medication.

Mr AT reports gynaecomastia and impotence, and says that he will not take any antipsychotics as they are “poison designed by MI6”, although is unable to concentrate on the discussion owing to hearing voices.

He is prescribed clonazepam 1mg twice daily owing to his distress, which is to be reduced as treatment controls his psychosis. He is offered nicotine replacement therapy but decides to use an e-cigarette on the ward.

He is unable to weigh up information to make decisions owing to his chaotic thinking and is felt to not have capacity to make decisions on his treatment. The team debates what treatment to offer.

Patient preference

Mr AT refuses all options presented to him. A decision is made to administer against his will and aripiprazole is chosen as it is less likely to cause hyperprolactinaemia and sexual dysfunction. He then agrees to take tablets “if it will get me out of hospital”.

![mental health schizophrenia case study Table 1: Common side effects of antipsychotics[9]](https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/clozapine-schizophrenia-Table-1-Common-side-effects-WM.jpg)

After eight weeks of treatment with orodispersible aripiprazole 15mg, Mr AT is able have a more coherent conversation, but is hallucinating and distressed. He is clearly under treated. The pharmacist attempts to complete a side-effect rating scale ( Glasgow Antipsychotic Side-effect Scale [GASS] ) but he declines. He is pacing around the ward in circles: it is felt he may be experiencing akathisia (restlessness) — a common side effect of antipsychotics (see Table 1 ).

Treatment review

The team feels clozapine is the best option owing to the treatment failure of two antipsychotics.

The team suggests this to Mr AT. He refuses, stating the ward is experimenting on him with new medication and he refuses to take another antipsychotics.

The pharmacist meets the patient with an occupational therapist to discuss what his goals are. Mr AT states he wants to go to college to become a carpenter. They discuss routes to achieve this, which all involve the first step of leaving hospital and the conclusion that clozapine is the best way to achieve this. The pharmacist clarifies the patient’s aripiprazole will not continue once clozapine is established. They leave information about clozapine with the patient and offer to return to discuss it further.

Mr AT agrees to take clozapine a week later (see Box 4) [10–14] . Aripiprazole is tapered and stopped.

Box 4: Clozapine characteristics

Clozapine significantly prolongs life and improves quality of life [10] . Delaying clozapine is associated with poorer outcomes for patients [11] .

Clozapine is under-prescribed owing to healthcare professionals’ anxiety and unfamiliarity around its use [12–14] .

It causes neutropenia in up to 3% of patients so regular monitoring is required . Twice-weekly monitoring is needed if neutrophils are <2 x10 9 /L. Most patients should stop clozapine if neutrophils are <1.5×10 9 /L. These ranges can differ from some laboratory definitions of neutropenia.

Other side effects include sedation, hypersalivation and weight gain. See Table 2 for red flags for serious side effects.

Clozapine is titrated up slowly to avoid cardiovascular complications. A treatment break of >48 hours warrants specialist advice for a retitration plan.

The pharmacist meets with Mr AT to discuss clozapine. He is told that this is likely to be a long-term treatment. The pharmacist acknowledges that the patient disagrees with his diagnosis, but this treatment is likely to prevent him from returning to hospital.

He is started on clozapine at 12.5mg at night, which is slowly increased. Pre- and post-dose monitoring of his vital signs is completed.

On day nine of the titration, his pulse is 115bpm. He otherwise feels well and blood tests show no signs of myocarditis (see Table 2), so the titration is continued but slowed.

After 3 weeks he is taking 150mg twice daily of clozapine and his symptoms have significantly improved: he is regularly bathing, not visibly hallucinating and engaging with staff.

The pharmacy technician completes a GASS form. Mr AT reports constipation, hypersalivation and sedation.

A pharmacist meets the patient to reiterate important counselling points, and discuss questions he may have about his treatment and how to manage side effects. Medication changes are made with the patients’ input:

- His constipation is monitored with a stool chart and he is started on senna 15mg at night;

- He is started on hyoscine hydrobromide 300 micrograms at night for salivation;

- He is switched to clozapine 300mg once daily at night to simplify his regime and reduce daytime sedation. His clonazepam is reduced and stopped.

Smoking is discussed owing to tobacco’s role as an enzyme inducer (more information on tobacco smoking and its potential drug interactions can be found in a previous article here ). Mr AT states he will continue to use an e-cigarette for now. He is informed that if he starts smoking again, his clozapine may become less effective and he should immediately inform his team.

He is discharged a few weeks later via a home treatment team and attends a clinic once weekly. On each attendance, he has a full blood count taken and analysed on site. He is assessed by a pharmacy technician and nurse for side effects and adherence to treatment, and his smoking status is clarified.

The technician asks what he thinks the clozapine has done for him. Mr AT states he is still unsure about having a mental illness, but recognises that clozapine has helped him out of hospital and intends to continue taking it.

![mental health schizophrenia case study Table 2: Red flags with clozapine[9]](https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/clozapine-schizophrenia-Table-2-Red-flags-with-clozapine-WM.jpg)

Good practice in the pharmaceutical care of psychosis involves:

- Active patient involvement in discussions on treatment decisions;

- Regular review of treatment: discussing efficacy, side effects and the patient’s view and understanding of treatment;

- Multidisciplinary approaches to helping patients choose treatment;

- For patients who dispute their diagnosis and the need for treatment, open dialogue is important. Such discussions should involve the patient’s goals, which are likely to be shared by the team (rapid discharge, preventing admissions, reducing distress);

- Information about treatment should be provided regularly in both written and verbal form;

- Where appropriate, involve carers/next of kin in decision making and information sharing.

Important points

- Schizophrenia affects 1 in 200 people, meaning such patients will present regularly in all settings;

- Patients with acute psychosis, who are in recovery, may be managed by specialist teams, who are the best source of information for a patient’s care;

- Collaborating with the patient on a viable long-term treatment plan improves adherence;

- Clozapine is recommended where two antipsychotics have failed;

- Clozapine is a high-risk medicine, but the risks are manageable;

- Hydrocarbons produced by smoking (but not nicotine replacement therapy, e-cigarettes or chewing tobacco) induce the enzyme CYP1A2, which reduces clozapine levels markedly (up to 20–60%). Starting or stopping smoking could precipitate relapse or induce toxicity, respectively.

- 1 Conley RR, Kelly DL. Management of treatment resistance in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2001; 50 :898–911. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01271-9

- 2 Gillespie AL, Samanaite R, Mill J, et al. Is treatment-resistant schizophrenia categorically distinct from treatment-responsive schizophrenia? a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17 . doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1177-y

- 3 Taylor DM. Clozapine for Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Still the Gold Standard? CNS Drugs. 2017; 31 :177–80. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0411-6

- 4 Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. NICE. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 5 Clozaril 25 mg tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4411/smpc (accessed Jan 2022).

- 6 Psychosis and schizophrenia: what else might it be? NICE. 2020. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/psychosis-schizophrenia/diagnosis/differential-diagnosis/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 7 Service user experience in adult mental health: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS mental health services. NICE. 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg136/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 8 Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence . NICE. 2009. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76/ (accessed Jan 2022).

- 9 Taylor D, Barnes T, Young A. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry . 13th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: : Wiley 2018.

- 10 Meltzer HY, Burnett S, Bastani B, et al. Effects of Six Months of Clozapine Treatment on the Quality of Life of Chronic Schizophrenic Patients. PS. 1990; 41 :892–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.8.892

- 11 Üçok A, Çikrikçili U, Karabulut S, et al. Delayed initiation of clozapine may be related to poor response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015; 30 :290–5. doi: 10.1097/yic.0000000000000086

- 12 Whiskey E, Barnard A, Oloyede E, et al. An Evaluation of the Variation and Underuse of Clozapine in the United Kingdom. SSRN Journal. 2020. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3716864

- 13 Nielsen J, Dahm M, Lublin H, et al. Psychiatrists’ attitude towards and knowledge of clozapine treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2009; 24 :965–71. doi: 10.1177/0269881108100320

- 14 Verdoux H, Quiles C, Bachmann CJ, et al. Prescriber and institutional barriers and facilitators of clozapine use: A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research. 2018; 201 :10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.046

- This article was corrected on 31 January 2022 to clarify that tobacco is an enzyme inducer, not an enzyme inhibitor

Useful structured introduction to the subject for clinical purposes

Thank you Amrit for your feedback, we are pleased that you found this article useful.

Michael Dowdall, Executive Editor, Research & Learning

Please note that smoking causes enzyme INDUCTION not INHIBITION as stated. (Via aromatic polyhydrocarbons, not nicotine)

Hi James. Thank you for bringing this to our attention. This has now been corrected. Hannah Krol, Deputy Chief Subeditor

Only with Herbal formula I was able to cure my schizophrenia Illness with the product I purchase from Dr Sims Gomez Herbs A Clinic in South Africa

Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You might also be interested in…

Test your knowledge on mental health

Pharmacist Support launches workplace wellbeing course for pharmacy leaders

Burnout among pharmacy professionals needs to be addressed at ‘systemic level’, RPS report finds

- Previous Article

- Next Article

INTRODUCTION

Clinical pearl i – pharmacokinetics, clinical pearl ii – clozapine and agranulocytosis, clinical pearl iii – hyperprolactinemia and associated complications, case based clinical pearls: a schizophrenic case study.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

O. Greg Deardorff , Stephanie A. Burton; Case Based Clinical Pearls: A schizophrenic case study. Mental Health Clinician 1 February 2012; 1 (8): 191–195. doi: https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.n95632

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Clinical pearls based on the treatment of a patient with schizophrenia who had stabbed a taxi cab driver are discussed in this case study. Areas explored include the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine decanoate, strategies to manage clozapine-associated agranulocytosis, and approaches to addressing hyperprolactinemia.

Forensic psychiatry is a subspecialty in the field of psychiatry in which medicine and law collide. Practiced in many facilities such as hospitals, correctional institutions, private offices and courts, forensic psychiatry requires the cooperation of health care and legal professionals with the common goal of helping patients become competent of their legal charges and returning to a productive life in the community. In contrast to general psychiatric patients, the clients in this field have been referred through court systems instead of general practitioners and are evaluated not only for their symptoms but also their level of responsibility for their actions.

These patients can be some of the most challenging to treat because of factors such as non-compliance, an extensive history of failed medication trials, and the severity of their mental illness. Some of the most severe mentally ill patients reside in forensic psychiatric hospitals and have spent much of their lives institutionalized. Treatment refractory schizophrenia, defined as persistent psychotic symptoms after failing two adequate trials of antipsychotics, is a common occurrence in forensic psychiatric hospitals and often requires extensive manipulation of medication regimens to obtain a desired therapeutic response. Like other patients, these patients may present with barriers to using the most effective treatment such as agranulocytosis, inability to obtain and maintain therapeutic drug levels due to fast metabolism, or bothersome adverse effects such as hyperprolactinemia. In treatment resistant patients, it may still be necessary to use these medications even when barriers are present due to a lack of alternative therapeutic options not previously exhausted. In addition to complex regimens, treatment plans for these patients often require trials of multiple medication combinations or unique exploitation of interactions and biological phenomena.

We report a forensic case study that exemplifies multiple clinical pearls that may be useful in patients with treatment refractory schizophrenia. A 31-year-old African American female presented to the emergency room escorted by law enforcement after stabbing a cab driver with a pencil. The patient stated she was raped by the cab driver and while in the emergency room stated that “dirty cops brought me here.” She was admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit to determine competency to stand trial for the assault of the cab driver. She had been in many previous correctional institutions with a known history of schizophrenia and additional diagnoses of amenorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, and obesity.

The patient's history was significant for auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions beginning by age fourteen with a diagnosis of major depression with psychotic features. By age eighteen, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. She had multiple previous hospitalizations and a history of poor compliance as an outpatient. There was no known history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. Her family history was significant for schizophrenia, diabetes mellitus, and drug use. The patient reported abusive behavior by her grandmother, who was her primary caretaker as a child.

During hospitalization, the patient continued to report sexual assaults, accusing both patients and staff of rape, and declined to participate in groups. She denied any visual or auditory hallucinations but continued to exhibit paranoid delusions. The patient was later found to be permanently incompetent to stand trial and was committed to the state's department of mental health for long term treatment of her psychiatric illness.

The patient was previously treated with fluphenazine decanoate intermittently for two years with difficulty obtaining the desired therapeutic response. After approximately two months of therapy, the patient presumably at steady state (~14 day half-life) still failed to demonstrate any clinical response. There is no conclusive evidence that fluphenazine levels correlate with clinical outcomes, however the psychiatrist had worked with this patient in the past and felt the lack of response in this situation justified a fluphenazine level. 1 The fluphenazine level was shown to be 2.2ng/ml (therapeutic range 0.5–3 ng/ml) while taking fluphenazine decanoate 50mg intramuscularly (IM) every two weeks. Increasing the target drug level to the upper edge of the normal range was warranted in this patient due to the persistent positive symptoms and a desire to continue using a long-acting injectable agent, which can ensure the delivery of medication in uncooperative and noncompliant patients. Fluphenazine is a high potency first generation antipsychotic that can improve positive symptoms of schizophrenia; however it is not effective in treating the negative symptoms. It was decided that the addition of a CYP2D6 inhibitor such as fluoxetine would not only provide increased levels of fluphenazine, but would also improve the patient's negative symptoms such as flat affect, anhedonia, social isolation and amotivation. 2 Thus, fluoxetine was given as 20 mg orally (PO) daily resulting in an increase of the fluphenazine level by 0.9 ng/ml (40%) after twenty two days of therapy to 3.1 ng/ml. One month later the fluphenazine decanoate dose was increased to 125 mg IM every two weeks (max 100mg/dose), with continued fluoxetine treatment, resulting in a supratherapeutic level of 3.6 ng/ml. Positive and negative symptoms only showed minor improvement. A 6-week study by Goff, et al. demonstrated an increase of up to 65% in fluphenazine serum concentrations in patients administered concomitant fluoxetine 20 mg/day. 2 In this case, the addition of fluoxetine safely and effectively elevated fluphenazine blood levels. Addition of an inhibitor may be beneficial in patients who are CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers, as was suspected in this patient.

Many complications, including prolonged jail time, can arise from forensic clients being non-compliant with their medications, which is the reason long acting injectables are often warranted. Our patient had a history of non-compliance and continued to experience positive symptoms despite treatment with fluphenazine. Therefore, the decision was made to try another long-acting antipsychotic injection. After reviewing the patient's chart, it was noted that a previous trial of oral haloperidol 30mg/day showed moderate improvement. Thus, after tolerability and efficacy was determined with oral haloperidol the patient was converted to haloperidol decanoate 300 mg (10–15 x oral daily dose of haloperidol) administered every three weeks beginning two weeks after discontinuation of fluphenazine decanoate 125 mg IM every two weeks. Fluphenazine levels approximately six weeks after its discontinuation (and two weeks after the discontinuation of fluoxetine 20 mg PO daily) were still supratherapeutic. Given that this patient had a fluphenazine level of 3.6 ng/ml near the time of haloperidol decanoate administration, it would be questionable whether another high potency antipsychotic would be of any additional benefit in comparison to the increased risk of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS). Data provided in one study showed fluphenazine decanoate as being detectable for up to 48 weeks after discontinuation. 3 Because fluphenazine decanoate can be detected for such an extended period of time, it leaves the patient at a continued risk for extrapyramidal side effects, especially if another antipsychotic is added shortly thereafter. In the forensic population, many patients have treatment refractory schizophrenia and the use of antipsychotics will need to be life-long. It is often common for these patients to be on multiple concurrent agents, increasing the risk for developing long-term extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, it is important to minimize the risk of these symptoms whenever possible.

Despite supratherapeutic levels of fluphenazine, the psychiatrist felt it would be beneficial to continue haloperidol decanoate 300 mg every three weeks with increased monitoring for signs and symptoms of EPS.

During the current admission the patient continued to exhibit paranoid behavior and lack of insight, expressed anger, and disliked attending or participating in groups. Her medication history included haloperidol, fluphenazine, quetiapine, aripiprazole, asenapine, olanzapine, paliperidone, and sixteen days of clozapine therapy before leukopenia warranted discontinuation. Due to her extensive history of failed antipsychotics and the known superior effectiveness of clozapine, this patient was an ideal candidate for clozapine therapy. Additionally, because of the poor quality of life a declaration of incompetency would lead to, using the most effective possible agent is an important priority in forensic patients. Clozapine is the most effective antipsychotic based on the U.S. Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) and the UK Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS). 4 , 5 In regards to the significant blood draws and monitoring that is continuously required, clozapine can be a challenging medication to use in treatment refractory patients.

One strategy we are currently working on in our hospital to help increase the number of patients on clozapine is using a point of care (POC) lab device which will allow a complete blood count (CBC) plus 5-part differential to be completed by finger stick, instead of weekly blood draws that our nurses, physicians and, especially, patients dislike. The cost of the POC lab device is approximately $20,000, although upon completion of a cost analysis it was found that five CBCs per day would pay for the cost of the machine after one year. Many times, these patients can become irritated and violent when having their blood drawn, especially, if on a consistent basis. Repetitive blood draws was noted by our physicians to be the largest obstacle in using clozapine in our treatment refractory patients.

Our primary challenge in using clozapine for this patient was finding a way to maintain the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) within acceptable limits (≥1500mm 3 ), which is not uncommon for many patients. The Clozaril Patient Monitoring Services revealed 0.4% of patients had pre-treatment white blood cell counts (WBC) too low to allow initiation of clozapine. Of these patients, 75% were of African or African-Caribbean descent, likely due to the increased leukocyte marginalization that has been shown to be more prominent in these populations. 6 Of all neutrophils in the body, 90% reside in the bone marrow and the remainder circulates freely in the blood or deposit next to vessel walls (margination). The addition of lithium has been shown to increase neutrophil counts by 2000/mm 3 through demarginalization of leukocytes. 7 This increase is not dose –related but may require a minimum lithium level of 0.4 mmol/L. 8 , 9 Lithium therapy used to increase neutrophil counts may be especially effective in patients of African or African-Caribbean descent due to demarginalization of leukocytes. In this patient case, lithium 300 mg by mouth three times daily was initiated for fifteen days to increase the absolute neutrophil count from 1200/mm 3 to ≥ 1500/mm 3 for continuation of clozapine while the white blood cells continued to stay within appropriate limits of ≥3000/mm 3 . It was soon realized that lithium was being cheeked, so liquid form was given, but discontinued after the patient continued to spit the medication out. Unfortunately, clozapine was discontinued thereafter as a result of noncompliance with the lithium causing failure to maintain appropriate white blood cell counts.

Another possible strategy for obtaining appropriate WBC and ANC levels that would enable clozapine continuation is to obtain blood samples later in the day. A study recently published compared the same set of patients having early morning blood draws to blood draws taken later in the day (mean sampling time - pre/post was 5 hours 24 minutes). 10 They showed a difference in the pre/post time change in WBC values being marginally significant (mean increase=667/mm 3 , p=.07), with a significant difference (mean increase=1,130/mm 3 , p=.003) between the pre/post time change in ANC values. ANC values were impacted to a greater extent by the time change than WBC values in this sample. Changing the time at which blood draws are taken during the day may allow for clozapine continuation by limiting the risk of pseudoneutropenia, however it remains the clinician's responsibility to discern between benign or malignant neutropenia. 10 It is recommended, for patients with WBC values trending down or below the predefined criteria, to have labs redrawn several hours after the morning lab before clozapine therapy is discontinued. 10 In this case study, obtaining the sample later in the day may have allowed our patient to continue clozapine therapy.

The patient in this case had additional diagnoses of amenorrhea and hyperprolactinemia. The diagnosis of amenorrhea prompted clinicians to obtain labs showing a prolactin level of 168.8 ng/ml (normal ranges: 3–20ng/ml for men; 4–25ng/ml for non-pregnant women; 30–400ng/ml for pregnant women). Lab monitoring of prolactin levels is not necessary if the patient is not exhibiting symptoms such as disturbances in the menstrual cycle, galactorrhea, gynecomastia, retrograde ejaculation, impotence, oligospermia, short luteal phase syndrome, diminished libido or hirsutism. Monitoring guidelines published in 2004 by APA recommend screening for symptoms of hyperprolactinemia at each visit for the first year and then yearly thereafter. Mt. Sinai Conference Physical Health Monitoring Guidelines for Antipsychotics published in 2004 recommended monitoring at every visit for the first twelve weeks and then yearly.

Occasionally, practitioners are confronted with the dilemma of whether treatment of hyperprolactinemia is warranted in asymptomatic patients. In answering that question, a few things should be considered, such as the patient's risk for osteoporosis and/or cardiovascular disorders. If there are no physical issues of concern, then psychological issues should be addressed. Estrogen deficiency, which may occur with increased prolactin, mediates mood, cognition and psychopathology. 11 Results of several studies conducted in women with hyperprolactinemia have demonstrated increased depression, anxiety, decreased libido and increased hostility. Men shared similar problems but did not exhibit an increase in hostility. 12 The authors hypothesized that women demonstrated increased hostility as a protective mechanism for their offspring.

Antipsychotic medications have differing potencies in regards to hyperprolactinemia, which may help guide product selection. The most potent inducer is risperidone, followed by haloperidol, olanzapine, and ziprasidone. 13 Clozapine and quetiapine are truly sparing, and aripiprazole has even been shown to reduce prolactin levels. 14 Aripiprazole may be a viable treatment option in some patients with hyperprolactinemia. In one study, females with risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia taking therapeutic doses of risperidone 2 to 15 mg/day showed significantly lower prolactin levels from weeks 8 to 16 compared to baseline when administered aripiprazole (3, 6, 9, or 12 mg daily). 15 The mean percent reductions in prolactin concentration at 3, 6, 9, and 12 mg daily were approximately 35%, 54%, 57%, and 63%; however, there was little variability in prolactin levels above 6 mg daily of aripiprazole. Therefore, unless giving liquid form, aripiprazole 5mg daily should be an optimal dose in lowering prolactin levels. In this case, the patient exhibited the clinical symptom of amenorrhea, which correlated with an elevated prolactin level. The addition of aripiprazole 10 mg by mouth once daily decreased this patient's prolactin level by 51 ng/mL (30.3%) after twelve days of treatment.

If an elevated prolactin level is incidentally found, the patient should be monitored for symptoms and labs may be repeated. In patients exhibiting symptoms of hyperprolactinemia with a serum level <200 ng/mL, the antipsychotic dose should be reduced or the agent changed to a more prolactin-sparing drug. 13 If switching the agent is not reasonable, the addition of a dopamine agonist such as bromocriptine or cabergoline may be beneficial, as well as the antiviral agent amantadine. 16 In patients with levels >200 ng/mL, or with persistently elevated levels despite changing to a more prolactin-sparing agent, an MRI of the sella turcica should be obtained to rule out a pituitary adenoma or parasellar tumor. 13 Practitioners should be aware that prolactin levels may remain elevated for significant periods of time following discontinuation of a long acting causative agent due to continued D 2 receptor antagonism. 1 One study found elevated prolactin levels in patients who discontinued fluphenazine decanoate as much as six months after the last injection. 1 , 3

In summary, we have discussed a few clinical pearls to be considered when working with treatment refractory patients with schizophrenia and outlined some unique aspects of treatment in forensic clients. First, we reviewed potential complications and concerns with using fluphenazine decanoate. In addition, we discussed that ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers may need an increase in dose when appropriate and/or an addition of an inhibitor. Secondly, patients with agranulocytosis that may benefit from clozapine may find improvement in WBC and ANC values with the administration of lithium and/or changing the time of day in which labs are drawn.

Lastly, hyperprolactinemia may result in not only physical symptoms but psychological symptoms as well. Also, health care providers should not only be cognizant regarding how and when to monitor for hyperprolactinemia, but also the various treatment options available, such as changing to less offensive agents, dopamine agonists, or adding low dose aripiprazole. This patient case exemplified multiple strategies that can be considered when managing treatment refractory patients in which alternative options for therapy are not readily available.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'Case Based Clinical Pearls: A schizophrenic case study' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: Case Based Clinical Pearls: A schizophrenic case study

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Get email alerts.

- Advertising

- Permissions

Affiliations

- eISSN 2168-9709

- Privacy Policy

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves. People with schizophrenia may seem like they have lost touch with reality, which can be distressing for them and for their family and friends. The symptoms of schizophrenia can make it difficult to participate in usual, everyday activities, but effective treatments are available. Learn more about schizophrenia .

Join A Study

For opportunities to participate in NIMH research on the NIH campus, visit the clinical research website . Travel and lodging assistance may be available.

Featured Studies

Featured studies include only those currently recruiting participants . Studies with the most recent start date appear first.

Anti-Inflammatory Challenge in Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 31, 2024 Eligibility: 18 Years to 45 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia, United States; Emory University Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

This research project will explore negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as motivational deficits, by examining the relationship between inflammation and reward-related brain regions. To accomplish this, we will administer a single infusion of either the anti-inflammatory medication infliximab or placebo (n=10 per group) to patients with high inflammation.

This study is important because schizophrenia can be a chronic and debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder and negative symptoms are some of the most difficult aspects of schizophrenia associated with worst functional outcomes. These symptoms do not typically respond to antipsychotic therapies, and as such, there are no current medications to treat negative symptoms.

Young Adults With Violent Behavior During Early Psychosis

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: February 29, 2024 Eligibility: 16 Years to 30 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York, United States

This study aims to provide an evidence-based behavioral intervention to reduce violent behavior for individuals experiencing early psychosis.

Tau Biomarkers in Late-onset Psychosis (LOP)

Study Type: Observational Start Date: February 16, 2024 Eligibility: 65 Years to 85 Years Location(s): The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, United States

Hallucinations or delusions that occur for the first time in older people with no acute medical problems or mood symptoms may be related to impending dementia. This study aims to confirm this hypothesis using novel blood biomarkers and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging tracers, as well as non-invasive testing.

Enhanced Coordinated Specialty Care for Early Psychosis

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: February 1, 2024 Eligibility: Age N/A, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): McLean Hospital OnTrack Clinic, Belmont, Massachusetts, United States; Massachusetts General Hospital FEPP Clinic, Boston, Massachusetts, United States

The goal of this clinical trial is to compare engagement in treatment in coordinated specialty care (CSC) to five extra care elements (CSC 2.0) in first-episode psychosis. The main question it aims to answer is:

• Does the addition of certain elements of care increase the number of visits in treatment for first-episode psychosis?

Participants will either:

Receive care as usual (CSC) or

Receive care as usual (CSC) plus five additional care elements (CSC 2.0):

Individual peer support Digital outreach Care coordination Multi-family group therapy Cognitive remediation

Researchers will compare the standard of care (CSC) to CSC 2.0 to see if participants receiving CSC 2.0 have more visits to their clinic in their first year.

Accelerated Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for People With Schizophrenia Treated With Clozapine

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: December 1, 2023 Eligibility: 18 Years to 50 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

In this study, the investigators will examine whether a type of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation called accelerated intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS) can augment neurocognition in individuals who receive treatment with clozapine. Following a baseline evaluation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), participants will undergo a session of iTBS +MRI and session of sham delivery + MRI. The order for these sessions will be blinded and randomized. The investigators predict that accelerated iTBS will enhance neurocognition relative to sham delivery.

Auditory Control Enhancement (ACE) in Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: September 5, 2023 Eligibility: 18 Years to 40 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Western Psychiatric Hospital of UPMC, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

The purpose of this clinical trial is to investigate neural markers of target engagement to further develop auditory control enhancement (ACE) as a novel, inexpensive, and noninvasive intervention to address treatment-refractory auditory hallucinations. Here, we will address questions about the feasibility and acceptability of ACE, as well as the degree to which ACE results in measurable engagement of biophysical and neurophysiological targets.

Participants will complete:

Auditory Control Enhancement (ACE): Participants will be assigned by chance (such as a coin flip) into one of two groups to receive a different dosage or level of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) during three sessions of cognitive training. tDCS is used to stimulate the brain for a short period of time. For tDCS one or two thin wet sponges are placed on the head and/or upper arm. The sponges will be connected to electrodes which will deliver a very weak electrical current. The Neuroelectrics Starstim 32 will be used to deliver tDCS. Interviews: Before and after ACE, in two separate sessions, participants will be asked questions about a) background; b) functioning in daily life and across different phases of your life and past, present and future medical records. Cognitive Tests: During the interview sessions, participants will also perform cognitive tests. Participants will be asked to complete computerized and pen-and-paper tests of attention, concentration, reading, and problem-solving ability. EEG scan: Participants will be asked to complete EEG (electroencephalography) studies before and after ACE training. EEG will be measured using the same Neuroelectrics Starstim 32 system used for tDCS. EEG measures the natural activity of the brain using small sensors placed on the scalp. These sensors use conductive gel to provide a connection suitable for recording brain activity. During EEG, participants will watch a silent video while sounds are played over headphones, or sometimes count the sounds. In addition to these auditory tasks, participants will also be asked to perform visual attention tasks, such pressing a button for a letter or image. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Scan: Participants will also be asked to complete MRI studies before and after ACE training. An MRI is a type of brain scan that takes pictures of the brain that will later be used to create a 3D model of the brain. The MRI does not use radiation, but rather radio waves, a large magnet and a computer to create the images.

Researchers will compare individuals receiving ACE to those receiving sham tDCS during cognitive training to determine effects of ACE.

Restoring Spindle and Thalamocortical Efficiency in Early-Course Schizophrenia Patients Using Auditory Stimulation

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: July 20, 2023 Eligibility: 18 Years to 40 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

The purpose of this research is to identify differences in brain activity during sleep between health individuals and individuals with schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorder. This study will also investigate whether tones played during deep sleep can enhance specific features of sleep and whether enhancing such features is related to an improvement in cognitive performance.

EPI-MINN: Targeting Cognition and Motivation - National

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: May 30, 2023 Eligibility: 15 Years to 40 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Minnesota Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

The purpose of this study is to perform a practice-based research project designed to assess whether cognition and motivated behavior in early psychosis can be addressed as key treatment goals within real-world settings by using a 12-week mobile intervention program. Participants who are receiving care at coordinated specialty care (CSC) early psychosis clinics across the United States will be recruited to participate in this study. A qualifying CSC program will provide comprehensive clinical services such as psychotherapy, medication management, psychoeducation, and work or education support. This study will be conducted remotely, and participants can participate at home with their own electronic devices.

The aim of this study is to investigate a well-defined 12-week mobile intervention program specifically designed to target cognitive functioning and motivated behavior for individuals with early psychosis. Participants will complete a screening interview which will include diagnosis and symptom ratings, neurocognitive assessment, and self-reports of symptoms, behavior, and functioning. Then participants will be randomized to receive the 12-week mobile intervention, or an active control of treatment as usual. The investigators will test for differences in the clinical trajectories after training, and at two follow up appointments at 6 and 12 months post-training.

Improving Cognition Through Telehealth Aerobic Exercise and Cognitive Training After a First Schizophrenia Episode

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: May 23, 2023 Eligibility: 18 Years to 45 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): UCLA Aftercare Research Program, Los Angeles, California, United States

The participants in the study will receive psychiatric treatment at the UCLA Aftercare Research Program. All participants in this 12-month RCT will receive cognitive training. Half of the patients will also be randomly assigned to the aerobic exercise and strength training condition, and the other half will be randomly assigned to the Healthy Living Group condition. The primary outcome measures are improvement in cognition and level of engagement in the in-group and at-home exercise sessions. Increases in the level of the patient's serum brain-derived neurotropic factor (specifically Mature BDNF) which causes greater brain neuroplasticity and is indicator of engagement in aerobic exercise, will be measured early in the treatment phase in order to confirm engagement of this target. In order to demonstrate the feasibility and portability of this intervention outside of academic research programs, the interventions will be provided via videoconferencing. The proposed study will incorporate additional methods to maximize participation in the exercise condition, including the use of the Moderated Online Social Therapy (MOST) platform to enhance motivation for treatment based on Self-Determination Theory principles, and a "bridging" group to help the participants generalize gains to everyday functioning. In addition, the exercise group participants will receive personally tailored text reminders to exercise.

Deep Brain Stimulation in Treatment Resistant Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 1, 2023 Eligibility: 22 Years to 65 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, United States

The purpose of this pilot study is to investigate the use of deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) in subjects with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. There is a subset of patients with schizophrenia who continue to have persistent psychotic symptoms (auditory hallucinations and delusions) despite multiple adequate medication trials with antipsychotic medications including clozapine. There are currently no available treatments for such patients who generally have poor function and are chronically disabled, unable to work, live independently or have meaningful social relationships. Neuroimaging studies in patients with schizophrenia have revealed information about pathological neural circuits that could be suitable targets using deep brain stimulation. Although not yet tested in patients with schizophrenia, DBS is in early phase clinical trials in other psychiatric disorders.

This pilot study will investigate the use of DBS in treatment-resistant schizophrenia subjects who have exhausted all other therapeutic alternatives but continue to have persistent disabling psychotic symptoms. Of note, DBS is not FDA approved for use in patients with schizophrenia. The method will be similar to that used in subthalamic nucleus stimulation in patients with Parkinson's Disease. However, the electrode will be advanced slightly inferior into the SNr, a major outflow nucleus of the basal ganglia, with the intention of causing local inhibition of SNr outflow resulting in disinhibition of the mediodorsal nucleus (MDN) of the thalamus. Hypofunction of the MDN has been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia in post-mortem as well as multiple structural and functional imaging studies. Evidence suggests that dysfunction of the MD is implicated in both positive and cognitive symptoms (such as working memory impairment) in schizophrenia. Frequent monitoring and clinical assessment with psychiatric scales will be used to monitor treatment response.

Song-making In a Group (SING)

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: October 14, 2022 Eligibility: 18 Years to 65 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

The overarching aim of the proposed work is to align a promising treatment lead - Musical Intervention (MI) - with a promising mechanistic account of psychosis - Predictive Processing. This protocol focuses on the R33 phase, to optimize its administration (Is active participation more effective than passive listening? Does creation of new music help more than performing others' creations?). By tracking the interrelation between symptom mechanisms and MI, the investigators can use those metrics to prospectively assign patients to particular MI.

The R33 phase will examine the impact of SING on computational behavioral metrics of (Aim 1) Conditioned Hallucinations, (Aim 2) Social Reinforcement Learning, (Aim 3) Language Use, in 200 participants with voice hearing in the context of a psychotic illness (n=50per per group). Following a screening visit to determine eligibility, these computerized tasks will be administered behaviorally, and an interview will elicit speech, prior to and following the full SING intervention (in 10 groups of 5 participants, each facilitated by a trained musical interventionist, during the first two years of the project).

Participants will complete these tasks prior to and following randomization to four different conditions (facilitated by a SING team member) that will deconstruct the possible active ingredients of SING along two dimensions: Activity and Ownership: (a) SING (n=50, Activity + and Ownership +), participants produce and perform their own song; (b) Karaoke (n=50, Activity + and Ownership -), participants perform karaoke, singing along to others music; (c) Pop Music (n=50, Activity - and Ownership -), participants will listen to popular music chosen by the music interventionists; and (d) Curated Playlists (n=50, Activity -, Ownership +), participants will curate playlists of popular music and listen to them together.

This deconstruction will provide insights into the predictive processing framework, as applied to hallucinations and music, specifically, whether changes at higher, a-modal, hierarchical levels, particularly sense of self and active inference, influence precision weighted perceptual and social inferences more so than inactive experiences or experiences that do not engage sense of self.

This R33 portion of the study was originally included in NCT05537428, which now has results posted for the R61 phase of the study.

What the Nose Knows: Hedonic Capacity, Psychosocial Interventions and Outcomes in Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: September 2, 2022 Eligibility: 18 Years to 65 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, United States

This project proposes to conduct the first study of the predictive utility of olfactory hedonic measurement for targeted psychosocial rehabilitation in schizophrenia. The information gathered from the project is of considerable public health relevance, in that, through simple, reliable olfactory assessment, it will provide knowledge about which individuals are most likely to benefit from these psychosocial interventions. Such information is crucial for tailoring existing interventions and developing new approaches to optimize outcomes in schizophrenia.

State Representation in Early Psychosis - Project 4

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: July 31, 2022 Eligibility: 15 Years to 45 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

The purpose of this study is to examine state representation in individuals aged 15-45 who have been diagnosed with a psychotic illness, as well as young adults who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis. State Representation is our ability to process information about our surroundings. The investigators will complete a clinical trial examining two paradigms of cognitive training.

Remote State Representation in Early Psychosis

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: July 27, 2022 Eligibility: 18 Years to 30 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

The purpose of this study is to examine state representation in individuals aged 15-40 who have been diagnosed with a psychotic illness, as well as young adults who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis. State Representation is our ability to process information about our surroundings. The investigators will complete some observational tests as well as a cognitive training clinical trial.

Clozapine for the Prevention of Violence in Schizophrenia: a Randomized Clinical Trial

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 17, 2022 Eligibility: 18 Years to 65 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York, United States

Two-hundred and eighty individuals with schizophrenia who have a recent history of violent acts will be randomized in this 2-arm, parallel-group, 24-week, open-label, 7-site clinical trial to examine the effects of treatment with clozapine vs antipsychotic treatment as usual (TAU) for reducing the risk of violent acts in real-world settings

Academic-Community EPINET (AC-EPINET)

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 16, 2022 Eligibility: 16 Years to 35 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Strong Ties Young Adults Program- University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York, United States; Program for Risk Evaluation and Prevention (PREP) - University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States; Early Psychosis Intervention Clinic-New Orleans (EPIC-NOLA) - Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, United States; Prevention and Recovery Center for Early Psychosis, Indianapolis, Indiana, United States; Vanderbilt's Early Psychosis Program - Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, United States; The Early Psychosis Intervention Center (EPICENTER) at Ohio State, Columbus, Ohio, United States

The investigators propose to examine the effects of CSC services delivered via TH (CSC-TH) versus the standard clinic-based CSC model (CSC-SD) on engagement and outcomes in a 12-month, randomized trial.

Antipsychotic Response to Clozapine in B-SNIP Biotype-1 (Clozapine)

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 1, 2022 Eligibility: 18 Years to 60 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, United States

The CLOZAPINE study is designed as a multisite study across 5 sites and is a clinical trial, involving human participants who are prospectively assigned to an intervention. The study will utilize a stringent randomized, double-blinded, parallel group clinical trial design. B2 group will serve as psychosis control with risperidone as medication control. The study is designed to evaluate effect of clozapine on the B1 participants, and the effect that will be evaluated is a biomedical outcome. The study sample will be comprised of individuals with psychosis, including 1) schizophrenia, 2) schizoaffective disorder and 3) psychotic bipolar I disorder. The investigators plan to initially screen and recruit n=524 (from both the existing B-SNIP library and newly-identified psychosis cases, ~50% each) in order to enroll n=320 (B1 and B2) into the RCT.

State Representation in Early Psychosis

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: December 1, 2021 Eligibility: 15 Years to 45 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

The purpose of this study is to examine state representation in individuals aged 15-45 who have been diagnosed with a psychotic illness, as well as young adults who do not have a psychiatric diagnosis. State Representation is our ability to process information about our surroundings. The investigators will complete some observational tests as well as a cognitive training clinical trial.

Enhancing Prefrontal Oscillations and Working Memory in Early-course Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: November 5, 2021 Eligibility: 18 Years to 40 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

This study will investigate the effects of intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation (iTBS) on natural oscillatory frequency of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and working memory in early-course schizophrenia (EC-SCZ). Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) will be used to evoke oscillatory activity, and EEG will record the responses of EC-SCZ participants. A working memory task will also be incorporated in order to determine how DLPFC natural frequency (NF) is related to working memory performance. iTBS (active or sham) will be administered, then the oscillatory activity of DLPFC and working memory performance will be reassessed. The overarching goal is to determine whether iTBS can acutely enhance the oscillatory activity of the DLPFC and to evaluate the relationship between changes in the DLPFC and working memory performance.

Targeting Processing Speed Deficits to Improve Social Functioning and Lower Psychosis Risk

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: October 28, 2021 Eligibility: 14 Years to 20 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Northwell Health- The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, New York, United States

This 10 week intervention, Specific Cognitive Remediation with Surround (or SCORES), is designed to target processing speed, a cognitive domain related directly to social functioning, which in turn, represents a vulnerability factor for psychosis. This remotely-delivered intervention combining targeted cognitive training exercises and group support was developed to directly impact processing speed, and at the same time, boost motivation and engagement in adolescents at risk for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.

Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) to Understand Hallucinations in Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: October 13, 2021 Eligibility: 18 Years to 55 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, United States

This study uses a noninvasive technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to study how hallucinations work in schizophrenia.

TMS is a noninvasive way of stimulating the brain, using a magnetic field to change activity in the brain. The magnetic field is produced by a coil that is held next to the scalp. In this study the investigators will be stimulating the brain to learn more about how TMS might improve these symptoms of schizophrenia.

Neurocognition After Perturbed Sleep

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: September 21, 2021 Eligibility: 18 Years to 60 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, United States

Individuals with schizophrenia display a wide range of neurocognitive difficulties resulting in functional impairment and disability. Extensive evidence indicates insomnia and sleep disturbances play a substantial role in degrading cognitive functioning. However, the putative impact of insomnia and sleep disturbances on neurocognition and daily functioning has not been investigated in people with schizophrenia. The goal of this study is to characterize sleep in individuals with schizophrenia and quantify its impact on neurocognition and daily functioning.

A Translational and Neurocomputational Evaluation of a Dopamine Receptor 1 Partial Agonist for Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: March 2, 2021 Eligibility: 18 Years to 45 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Columbia University, New York, New York, United States; Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, United States; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

This study will test whether CVL-562 (PF-06412562), a dopamine 1 partial agonist novel compound, affects working memory neural circuits in patients with early episode schizophrenia. The overall aim is to establish neuroimaging biomarkers of the Dopamine Receptor 1/Dopamine Receptor 5 Family (D1R/D5R) target engagement to accelerate development of D1R/D5R agonists in humans to treat cognitive impairments that underlie functional disability in schizophrenia, a key unaddressed clinical and public health concern.

Family-Focused Therapy for Individuals at High Clinical Risk for Psychosis: A Confirmatory Efficacy Trial

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: January 15, 2021 Eligibility: 13 Years to 25 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States; University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, California, United States; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, United States; Harvard University/Beth Israel Deconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, United States; Zucker Hillside Hospital, New York, New York, United States; University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States

The present study is a confirmatory efficacy trial of Family Focused Therapy for youth at clinical high risk for psychosis (FFT-CHR). This trial is sponsored by seven mature CHR clinical research programs from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS). The young clinical high risk sample (N = 220 youth ages 13-25) is to be followed at 6-month intervals for 18 months.

Medial-prefrontal Enhancement During Schizophrenia Systems Imaging

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: November 12, 2020 Eligibility: 18 Years to 64 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): UCSF, San Francisco, California, United States

This randomized controlled trial in healthy controls (HC) and patients with schizophrenia (SZ) aims to examine 1) the underlying cognitive and neural cause of self-agency deficits in SZ; 2) the responsiveness to a novel navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (nrTMS) target in the medial/superior prefrontal cortex (mPFC); and 3) how modulation of mPFC activity impacts the larger self-agency network to mediate changes in self-agency judgments. Our overall hypothesis is that increased mPFC excitability by active high-frequency nrTMS in HC and SZ will induce behavioral improvements in self-agency and neural changes in the larger self-agency network that will generalize to improvements in overall cognition, symptoms and daily functioning, and will likely lead to the development of new effective neuromodulation therapies in patients with schizophrenia.

Early-Phase Schizophrenia: Practice-based Research to Improve Outcomes

Study Type: Observational Start Date: April 1, 2020 Eligibility: 15 Years to 40 Years Location(s): Henderson Behavioral Health, Lauderdale Lakes, Florida, United States

The goal if the project is to develop a learning health network devoted to the treatment of first episode psychosis.

Multi-modal Assessment of Gamma-aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Function in Psychosis

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: January 16, 2020 Eligibility: 16 Years to 60 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States

The purpose of this study is to better understand mental illness and will test the hypotheses that while viewing affective stimuli, patient groups will show increased blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal by fMRI after lorazepam.

This study will enroll participants between the ages of 16 and 60, who have a psychotic illness (such as psychosis which includes conditions like schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and mood disorders). The study will also enroll eligible participants without any psychiatric illness, to compare their brains.

The study will require participants to have 3-4 sessions over a few weeks. The initial assessments (may be over two visits) will include a diagnostic interview and several questionnaires (qols) to assess eligibility. Subsequently, there will will be two separate functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) sessions in which lorazepam or placebo will be given prior to the MRI. During the fMRI the participants will also be asked to answer questions. Additionally, the participants will have their blood drawn, women of child bearing potential will have a urine pregnancy test, vital signs taken, and asked to complete more qols.

Promoting Activity and Cognitive Enrichment in Schizophrenia (PACES)

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: October 1, 2019 Eligibility: 18 Years to 60 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

This project will conduct a confirmatory efficacy trial of two novel psychosocial interventions, Cognitive Enhancement Therapy and Enriched Supportive Therapy, for the treatment of persistent negative symptoms in schizophrenia.

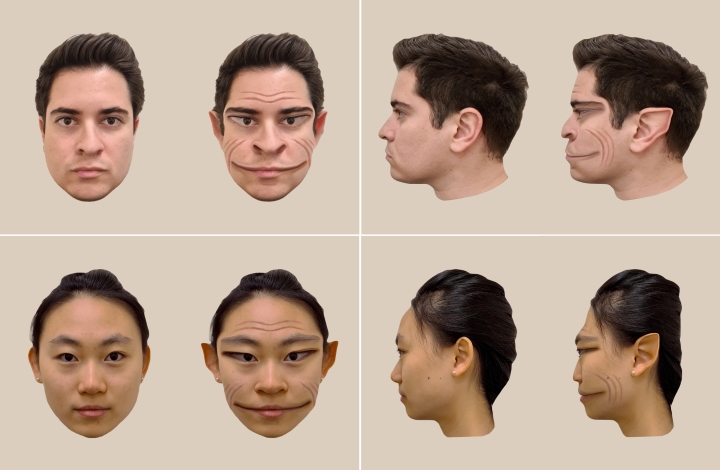

Remediation of Visual Perceptual Impairments in People With Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: June 1, 2018 Eligibility: 18 Years to 60 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): New York Presbyterian Hospital, White Plains, New York, United States

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a visual remediation intervention for people with schizophrenia. The intervention targets two visual functions that much research has shown are impaired in many people with the disorder, namely contrast sensitivity and perceptual organization. The first phase of the study will test the effects of interventions targeting each of these processes, as well as the effects of a combined package. A control condition of higher-level cognitive remediation is included as a fourth condition. The second phase of the study will evaluate the effectiveness of the most effective intervention from the first phase, but in a new and larger sample of individuals. Outcome measures include multiple aspects of visual functioning, as well as visual cognition and overall community functioning.

Neuronal Effects of Exercise in Schizophrenia

Study Type: Interventional Start Date: August 31, 2014 Eligibility: 21 Years to 70 Years, Does Not Accept Healthy Volunteers Location(s): University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, United States

This study plans to learn more about how common drugs prescribed to individuals with schizophrenia contribute to weight gain, as well as how exercise and diet impact appetite and the brain's response to food. In this study, the investigators will be evaluating how participants' brains respond to food images as well as asking questions about their food preferences and intake and clinical symptoms. The investigators may also ask participants to complete an exercise or diet intervention to see how this changes brain responses or food preferences.

Imaging Cannabinoid Receptors Using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scanning

Study Type: Observational Start Date: July 31, 2010 Eligibility: Males, 18 Years to 55 Years, Accepts Healthy Volunteers Location(s): Connecticut Mental Health Center, Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

The aim of the present study is to assess the availability of cannabinoid receptors (CB1R) in the human brain. CB1R are present in everyone's brain, regardless of whether or not someone has used cannabis. The investigators will image brain cannabinoid receptors using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging and the radioligand OMAR, in healthy individuals and several conditions including 1) cannabis use disorders, 2) psychotic disorders, 3) prodrome of psychotic illness and 4) individuals with a family history of alcoholism, 5) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 6) Opioid Use Disorder using the PET imaging agent or radiotracer, [11C]OMAR. This will allow us to characterize the number and distribution of CB1R in these conditions. It is likely that the list of conditions will be expanded after the collection of pilot data and as new data on cannabinoids receptor function and psychiatric disorders becomes available.