- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making - Logical Fallacies

Critical thinking and decision-making -, logical fallacies, critical thinking and decision-making logical fallacies.

Critical Thinking and Decision-Making: Logical Fallacies

Lesson 7: logical fallacies.

/en/problem-solving-and-decision-making/how-critical-thinking-can-change-the-game/content/

Logical fallacies

If you think about it, vegetables are bad for you. I mean, after all, the dinosaurs ate plants, and look at what happened to them...

Let's pause for a moment: That argument was pretty ridiculous. And that's because it contained a logical fallacy .

A logical fallacy is any kind of error in reasoning that renders an argument invalid . They can involve distorting or manipulating facts, drawing false conclusions, or distracting you from the issue at hand. In theory, it seems like they'd be pretty easy to spot, but this isn't always the case.

Watch the video below to learn more about logical fallacies.

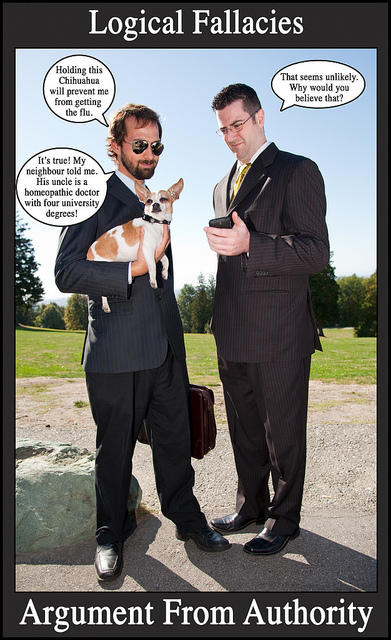

Sometimes logical fallacies are intentionally used to try and win a debate. In these cases, they're often presented by the speaker with a certain level of confidence . And in doing so, they're more persuasive : If they sound like they know what they're talking about, we're more likely to believe them, even if their stance doesn't make complete logical sense.

False cause

One common logical fallacy is the false cause . This is when someone incorrectly identifies the cause of something. In my argument above, I stated that dinosaurs became extinct because they ate vegetables. While these two things did happen, a diet of vegetables was not the cause of their extinction.

Maybe you've heard false cause more commonly represented by the phrase "correlation does not equal causation ", meaning that just because two things occurred around the same time, it doesn't necessarily mean that one caused the other.

A straw man is when someone takes an argument and misrepresents it so that it's easier to attack . For example, let's say Callie is advocating that sporks should be the new standard for silverware because they're more efficient. Madeline responds that she's shocked Callie would want to outlaw spoons and forks, and put millions out of work at the fork and spoon factories.

A straw man is frequently used in politics in an effort to discredit another politician's views on a particular issue.

Begging the question

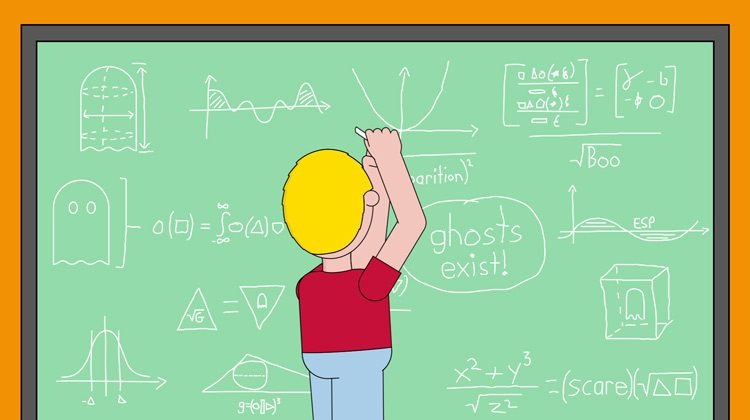

Begging the question is a type of circular argument where someone includes the conclusion as a part of their reasoning. For example, George says, “Ghosts exist because I saw a ghost in my closet!"

George concluded that “ghosts exist”. His premise also assumed that ghosts exist. Rather than assuming that ghosts exist from the outset, George should have used evidence and reasoning to try and prove that they exist.

Since George assumed that ghosts exist, he was less likely to see other explanations for what he saw. Maybe the ghost was nothing more than a mop!

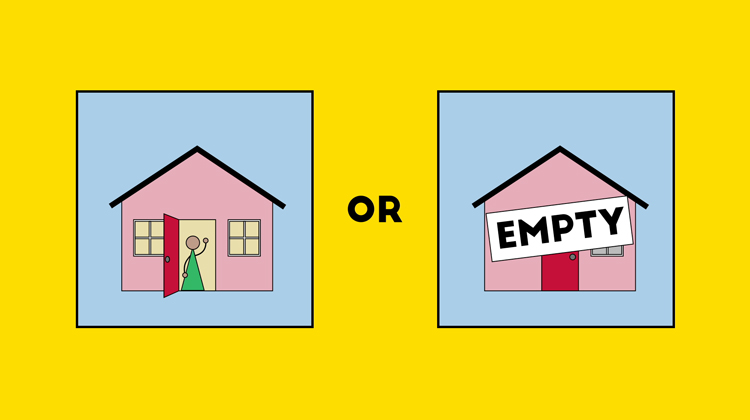

False dilemma

The false dilemma (or false dichotomy) is a logical fallacy where a situation is presented as being an either/or option when, in reality, there are more possible options available than just the chosen two. Here's an example: Rebecca rings the doorbell but Ethan doesn't answer. She then thinks, "Oh, Ethan must not be home."

Rebecca posits that either Ethan answers the door or he isn't home. In reality, he could be sleeping, doing some work in the backyard, or taking a shower.

Most logical fallacies can be spotted by thinking critically . Make sure to ask questions: Is logic at work here or is it simply rhetoric? Does their "proof" actually lead to the conclusion they're proposing? By applying critical thinking, you'll be able to detect logical fallacies in the world around you and prevent yourself from using them as well.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples

Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples

Published on April 20, 2023 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou . Revised on October 9, 2023.

A logical fallacy is an argument that may sound convincing or true but is actually flawed. Logical fallacies are leaps of logic that lead us to an unsupported conclusion. People may commit a logical fallacy unintentionally, due to poor reasoning, or intentionally, in order to manipulate others.

Because logical fallacies can be deceptive, it is important to be able to spot them in your own argumentation and that of others.

Table of contents

Logical fallacy list (free download), what is a logical fallacy, types of logical fallacies, what are common logical fallacies, logical fallacy examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about logical fallacies.

There are many logical fallacies. You can download an overview of the most common logical fallacies by clicking the blue button.

Logical fallacy list (Google Docs)

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning that occurs when invalid arguments or irrelevant points are introduced without any evidence to support them. People often resort to logical fallacies when their goal is to persuade others. Because fallacies appear to be correct even though they are not, people can be tricked into accepting them.

The majority of logical fallacies involve arguments—in other words, one or more statements (called the premise ) and a conclusion . The premise is offered in support of the claim being made, which is the conclusion.

There are two types of mistakes that can occur in arguments:

- A factual error in the premises . Here, the mistake is not one of logic. A premise can be proven or disproven with facts. For example, If you counted 13 people in the room when there were 14, then you made a factual mistake.

- The premises fail to logically support the conclusion . A logical fallacy is usually a mistake of this type. In the example above, the students never proved that English 101 was itself a useless course—they merely “begged the question” and moved on to the next part of their argument, skipping the most important part.

In other words, a logical fallacy violates the principles of critical thinking because the premises do not sufficiently support the conclusion, while a factual error involves being wrong about the facts.

There are several ways to label and classify fallacies, such as according to the psychological reasons that lead people to use them or according to similarity in their form. Broadly speaking, there are two main types of logical fallacy, depending on what kind of reasoning error the argument contains:

Informal logical fallacies

Formal logical fallacies.

An informal logical fallacy occurs when there is an error in the content of an argument (i.e., it is based on irrelevant or false premises).

Informal fallacies can be further subdivided into groups according to similarity, such as relevance (informal fallacies that raise an irrelevant point) or ambiguity (informal fallacies that use ambiguous words or phrases, the meanings of which change in the course of discussion).

“ Some philosophers argue that all acts are selfish . Even if you strive to serve others, you are still acting selfishly because your act is just to satisfy your desire to serve others.”

A formal logical fallacy occurs when there is an error in the logical structure of an argument.

Premise 2: The citizens of New York know that Spider-Man saved their city.

Conclusion: The citizens of New York know that Peter Parker saved their city.

This argument is invalid, because even though Spider-Man is in fact Peter Parker, the citizens of New York don’t necessarily know Spider-Man’s true identity and therefore don’t necessarily know that Peter Parker saved their city.

A logical fallacy may arise in any form of communication, ranging from debates to writing, but it may also crop up in our own internal reasoning. Here are some examples of common fallacies that you may encounter in the media, in essays, and in everyday discussions.

Red herring logical fallacy

The red herring fallacy is the deliberate attempt to mislead and distract an audience by bringing up an unrelated issue to falsely oppose the issue at hand. Essentially, it is an attempt to change the subject and divert attention elsewhere.

Bandwagon logical fallacy

The bandwagon logical fallacy (or ad populum fallacy ) occurs when we base the validity of our argument on how many people believe or do the same thing as we do. In other words, we claim that something must be true simply because it is popular.

This fallacy can easily go unnoticed in everyday conversations because the argument may sound reasonable at first. However, it doesn’t factor in whether or not “everyone” who claims x is in fact qualified to do so.

Straw man logical fallacy

The straw man logical fallacy is the distortion of an opponent’s argument to make it easier to refute. By exaggerating or simplifying someone’s position, one can easily attack a weak version of it and ignore their real argument.

Person 2: “So you are fine with children taking ecstasy and LSD?”

Slippery slope logical fallacy

The slippery slope logical fallacy occurs when someone asserts that a relatively small step or initial action will lead to a chain of events resulting in a drastic change or undesirable outcome. However, no evidence is offered to prove that this chain reaction will indeed happen.

Hasty generalization logical fallacy

The hasty generalization fallacy (or jumping to conclusions ) occurs when we use a small sample or exceptional cases to draw a conclusion or generalize a rule.

A false dilemma (or either/or fallacy ) is a common persuasion technique in advertising. It presents us with only two possible options without considering the broad range of possible alternatives.

In other words, the campaign suggests that animal testing and child mortality are the only two options available. One has to save either animal lives or children’s lives.

People often confuse correlation (i.e., the fact that two things happen one after the other or at the same time) with causation (the fact that one thing causes the other to happen).

It’s possible, for example, that people with MS have lower vitamin D levels because of their decreased mobility and sun exposure, rather than the other way around.

It’s important to carefully account for other factors that may be involved in any observed relationship. The fact that two events or variables are associated in some way does not necessarily imply that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between them and cannot tell us the direction of any cause-and-effect relationship that does exist.

If you want to know more about fallacies , research bias , or AI tools , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Straw man fallacy

- Slippery slope fallacy

- Either or fallacy

- Appeal to emotion fallacy

- Non sequitur fallacy

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Framing bias

- Cognitive bias

- Optimism bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Affect heuristic

An ad hominem (Latin for “to the person”) is a type of informal logical fallacy . Instead of arguing against a person’s position, an ad hominem argument attacks the person’s character or actions in an effort to discredit them.

This rhetorical strategy is fallacious because a person’s character, motive, education, or other personal trait is logically irrelevant to whether their argument is true or false.

Name-calling is common in ad hominem fallacy (e.g., “environmental activists are ineffective because they’re all lazy tree-huggers”).

An appeal to ignorance (ignorance here meaning lack of evidence) is a type of informal logical fallacy .

It asserts that something must be true because it hasn’t been proven false—or that something must be false because it has not yet been proven true.

For example, “unicorns exist because there is no evidence that they don’t.” The appeal to ignorance is also called the burden of proof fallacy .

People sometimes confuse cognitive bias and logical fallacies because they both relate to flawed thinking. However, they are not the same:

- Cognitive bias is the tendency to make decisions or take action in an illogical way because of our values, memory, socialization, and other personal attributes. In other words, it refers to a fixed pattern of thinking rooted in the way our brain works.

- Logical fallacies relate to how we make claims and construct our arguments in the moment. They are statements that sound convincing at first but can be disproven through logical reasoning.

In other words, cognitive bias refers to an ongoing predisposition, while logical fallacy refers to mistakes of reasoning that occur in the moment.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, October 09). Logical Fallacies | Definition, Types, List & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/fallacies/logical-fallacy/

Jin, Z., Lalwani, A., Vaidhya, T., Shen, X., Ding, Y., Lyu, Z., Sachan, M., Mihalcea, R., & Schölkopf, B. (2022). Logical Fallacy Detection. arXiv (Cornell University) . https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2202.13758

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, slippery slope fallacy | definition & examples, what is a red herring fallacy | definition & examples, what is straw man fallacy | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking

(10 reviews)

Matthew Van Cleave, Lansing Community College

Copyright Year: 2016

Publisher: Matthew J. Van Cleave

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by "yusef" Alexander Hayes, Professor, North Shore Community College on 6/9/21

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Formal and informal reasoning, argument structure, and fallacies are covered comprehensively, meeting the author's goal of both depth and succinctness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

While many modern examples are used, and they are helpful, they are not necessarily needed. The usefulness of logical principles and skills have proved themselves, and this text presents them clearly with many examples.

Clarity rating: 5

It is obvious that the author cares about their subject, audience, and students. The text is comprehensible and interesting.

Consistency rating: 5

The format is easy to understand and is consistent in framing.

Modularity rating: 5

This text would be easy to adapt.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The organization is excellent, my one suggestion would be a concluding chapter.

Interface rating: 5

I accessed the PDF version and it would be easy to work with.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The writing is excellent.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

This is not an offensive text.

Reviewed by Susan Rottmann, Part-time Lecturer, University of Southern Maine on 3/2/21

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

I reviewed this book for a course titled "Creative and Critical Inquiry into Modern Life." It won't meet all my needs for that course, but I haven't yet found a book that would. I wanted to review this one because it states in the preface that it fits better for a general critical thinking course than for a true logic course. I'm not sure that I'd agree. I have been using Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," and I think that book is a better introduction to critical thinking for non-philosophy majors. However, the latter is not open source so I will figure out how to get by without it in the future. Overall, the book seems comprehensive if the subject is logic. The index is on the short-side, but fine. However, one issue for me is that there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which is pretty annoying if you want to locate particular sections.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

I didn't find any errors. In general the book uses great examples. However, they are very much based in the American context, not for an international student audience. Some effort to broaden the chosen examples would make the book more widely applicable.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

I think the book will remain relevant because of the nature of the material that it addresses, however there will be a need to modify the examples in future editions and as the social and political context changes.

Clarity rating: 3

The text is lucid, but I think it would be difficult for introductory-level students who are not philosophy majors. For example, in Browne and Keeley's "Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking," the sub-headings are very accessible, such as "Experts cannot rescue us, despite what they say" or "wishful thinking: perhaps the biggest single speed bump on the road to critical thinking." By contrast, Van Cleave's "Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking" has more subheadings like this: "Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form" or "Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives." If students are prepared very well for the subject, it would work fine, but for students who are newly being introduced to critical thinking, it is rather technical.

It seems to be very consistent in terms of its terminology and framework.

Modularity rating: 4

The book is divided into 4 chapters, each having many sub-chapters. In that sense, it is readily divisible and modular. However, as noted above, there are no page numbers on the table of contents, which would make assigning certain parts rather frustrating. Also, I'm not sure why the book is only four chapter and has so many subheadings (for instance 17 in Chapter 2) and a length of 242 pages. Wouldn't it make more sense to break up the book into shorter chapters? I think this would make it easier to read and to assign in specific blocks to students.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The organization of the book is fine overall, although I think adding page numbers to the table of contents and breaking it up into more separate chapters would help it to be more easily navigable.

Interface rating: 4

The book is very simply presented. In my opinion it is actually too simple. There are few boxes or diagrams that highlight and explain important points.

The text seems fine grammatically. I didn't notice any errors.

The book is written with an American audience in mind, but I did not notice culturally insensitive or offensive parts.

Overall, this book is not for my course, but I think it could work well in a philosophy course.

Reviewed by Daniel Lee, Assistant Professor of Economics and Leadership, Sweet Briar College on 11/11/19

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

This textbook is not particularly comprehensive (4 chapters long), but I view that as a benefit. In fact, I recommend it for use outside of traditional logic classes, but rather interdisciplinary classes that evaluate argument

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as accurate, error-free, and unbiased

The book is broadly relevant and up-to-date, with a few stray temporal references (sydney olympics, particular presidencies). I don't view these time-dated examples as problematic as the logical underpinnings are still there and easily assessed

Clarity rating: 4

My only pushback on clarity is I didn't find the distinction between argument and explanation particularly helpful/useful/easy to follow. However, this experience may have been unique to my class.

To the best of my ability, I regard this content as internally consistent

I found this text quite modular, and was easily able to integrate other texts into my lessons and disregard certain chapters or sub-sections

The book had a logical and consistent structure, but to the extent that there are only 4 chapters, there isn't much scope for alternative approaches here

No problems with the book's interface

The text is grammatically sound

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Perhaps the text could have been more universal in its approach. While I didn't find the book insensitive per-se, logic can be tricky here because the point is to evaluate meaningful (non-trivial) arguments, but any argument with that sense of gravity can also be traumatic to students (abortion, death penalty, etc)

No additional comments

Reviewed by Lisa N. Thomas-Smith, Graduate Part-time Instructor, CU Boulder on 7/1/19

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text,... read more

The text covers all the relevant technical aspects of introductory logic and critical thinking, and covers them well. A separate glossary would be quite helpful to students. However, the terms are clearly and thoroughly explained within the text, and the index is very thorough.

The content is excellent. The text is thorough and accurate with no errors that I could discern. The terminology and exercises cover the material nicely and without bias.

The text should easily stand the test of time. The exercises are excellent and would be very helpful for students to internalize correct critical thinking practices. Because of the logical arrangement of the text and the many sub-sections, additional material should be very easy to add.

The text is extremely clearly and simply written. I anticipate that a diligent student could learn all of the material in the text with little additional instruction. The examples are relevant and easy to follow.

The text did not confuse terms or use inconsistent terminology, which is very important in a logic text. The discipline often uses multiple terms for the same concept, but this text avoids that trap nicely.

The text is fairly easily divisible. Since there are only four chapters, those chapters include large blocks of information. However, the chapters themselves are very well delineated and could be easily broken up so that parts could be left out or covered in a different order from the text.

The flow of the text is excellent. All of the information is handled solidly in an order that allows the student to build on the information previously covered.

The PDF Table of Contents does not include links or page numbers which would be very helpful for navigation. Other than that, the text was very easy to navigate. All the images, charts, and graphs were very clear

I found no grammatical errors in the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text including examples and exercises did not seem to be offensive or insensitive in any specific way. However, the examples included references to black and white people, but few others. Also, the text is very American specific with many examples from and for an American audience. More diversity, especially in the examples, would be appropriate and appreciated.

Reviewed by Leslie Aarons, Associate Professor of Philosophy, CUNY LaGuardia Community College on 5/16/19

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an... read more

This is an excellent introductory (first-year) Logic and Critical Thinking textbook. The book covers the important elementary information, clearly discussing such things as the purpose and basic structure of an argument; the difference between an argument and an explanation; validity; soundness; and the distinctions between an inductive and a deductive argument in accessible terms in the first chapter. It also does a good job introducing and discussing informal fallacies (Chapter 4). The incorporation of opportunities to evaluate real-world arguments is also very effective. Chapter 2 also covers a number of formal methods of evaluating arguments, such as Venn Diagrams and Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives, but to my mind, it is much more thorough in its treatment of Informal Logic and Critical Thinking skills, than it is of formal logic. I also appreciated that Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index, but there is no glossary; which I personally do not find detracts from the book's comprehensiveness.

Overall, Van Cleave's book is error-free and unbiased. The language used is accessible and engaging. There were no glaring inaccuracies that I was able to detect.

Van Cleave's Textbook uses relevant, contemporary content that will stand the test of time, at least for the next few years. Although some examples use certain subjects like former President Obama, it does so in a useful manner that inspires the use of critical thinking skills. There are an abundance of examples that inspire students to look at issues from many different political viewpoints, challenging students to practice evaluating arguments, and identifying fallacies. Many of these exercises encourage students to critique issues, and recognize their own inherent reader-biases and challenge their own beliefs--hallmarks of critical thinking.

As mentioned previously, the author has an accessible style that makes the content relatively easy to read and engaging. He also does a suitable job explaining jargon/technical language that is introduced in the textbook.

Van Cleave uses terminology consistently and the chapters flow well. The textbook orients the reader by offering effective introductions to new material, step-by-step explanations of the material, as well as offering clear summaries of each lesson.

This textbook's modularity is really quite good. Its language and structure are not overly convoluted or too-lengthy, making it convenient for individual instructors to adapt the materials to suit their methodological preferences.

The topics in the textbook are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The structure of the chapters are such that it is not necessary to have to follow the chapters in their sequential order, and coverage of material can be adapted to individual instructor's preferences.

The textbook is free of any problematic interface issues. Topics, sections and specific content are accessible and easy to navigate. Overall it is user-friendly.

I did not find any significant grammatical issues with the textbook.

The textbook is not culturally insensitive, making use of a diversity of inclusive examples. Materials are especially effective for first-year critical thinking/logic students.

I intend to adopt Van Cleave's textbook for a Critical Thinking class I am teaching at the Community College level. I believe that it will help me facilitate student-learning, and will be a good resource to build additional classroom activities from the materials it provides.

Reviewed by Jennie Harrop, Chair, Department of Professional Studies, George Fox University on 3/27/18

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters... read more

While the book is admirably comprehensive, its extensive details within a few short chapters may feel overwhelming to students. The author tackles an impressive breadth of concepts in Chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, which leads to 50-plus-page chapters that are dense with statistical analyses and critical vocabulary. These topics are likely better broached in manageable snippets rather than hefty single chapters.

The ideas addressed in Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking are accurate but at times notably political. While politics are effectively used to exemplify key concepts, some students may be distracted by distinct political leanings.

The terms and definitions included are relevant, but the examples are specific to the current political, cultural, and social climates, which could make the materials seem dated in a few years without intentional and consistent updates.

While the reasoning is accurate, the author tends to complicate rather than simplify -- perhaps in an effort to cover a spectrum of related concepts. Beginning readers are likely to be overwhelmed and under-encouraged by his approach.

Consistency rating: 3

The four chapters are somewhat consistent in their play of definition, explanation, and example, but the structure of each chapter varies according to the concepts covered. In the third chapter, for example, key ideas are divided into sub-topics numbering from 3.1 to 3.10. In the fourth chapter, the sub-divisions are further divided into sub-sections numbered 4.1.1-4.1.5, 4.2.1-4.2.2, and 4.3.1 to 4.3.6. Readers who are working quickly to master new concepts may find themselves mired in similarly numbered subheadings, longing for a grounded concepts on which to hinge other key principles.

Modularity rating: 3

The book's four chapters make it mostly self-referential. The author would do well to beak this text down into additional subsections, easing readers' accessibility.

The content of the book flows logically and well, but the information needs to be better sub-divided within each larger chapter, easing the student experience.

The book's interface is effective, allowing readers to move from one section to the next with a single click. Additional sub-sections would ease this interplay even further.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

Some minor errors throughout.

For the most part, the book is culturally neutral, avoiding direct cultural references in an effort to remain relevant.

Reviewed by Yoichi Ishida, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Ohio University on 2/1/18

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic,... read more

This textbook covers enough topics for a first-year course on logic and critical thinking. Chapter 1 covers the basics as in any standard textbook in this area. Chapter 2 covers propositional logic and categorical logic. In propositional logic, this textbook does not cover suppositional arguments, such as conditional proof and reductio ad absurdum. But other standard argument forms are covered. Chapter 3 covers inductive logic, and here this textbook introduces probability and its relationship with cognitive biases, which are rarely discussed in other textbooks. Chapter 4 introduces common informal fallacies. The answers to all the exercises are given at the end. However, the last set of exercises is in Chapter 3, Section 5. There are no exercises in the rest of the chapter. Chapter 4 has no exercises either. There is index, but no glossary.

The textbook is accurate.

The content of this textbook will not become obsolete soon.

The textbook is written clearly.

The textbook is internally consistent.

The textbook is fairly modular. For example, Chapter 3, together with a few sections from Chapter 1, can be used as a short introduction to inductive logic.

The textbook is well-organized.

There are no interface issues.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

This textbook is relevant to a first semester logic or critical thinking course.

Reviewed by Payal Doctor, Associate Professro, LaGuardia Community College on 2/1/18

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner... read more

This text is a beginner textbook for arguments and propositional logic. It covers the basics of identifying arguments, building arguments, and using basic logic to construct propositions and arguments. It is quite comprehensive for a beginner book, but seems to be a good text for a course that needs a foundation for arguments. There are exercises on creating truth tables and proofs, so it could work as a logic primer in short sessions or with the addition of other course content.

The books is accurate in the information it presents. It does not contain errors and is unbiased. It covers the essential vocabulary clearly and givens ample examples and exercises to ensure the student understands the concepts

The content of the book is up to date and can be easily updated. Some examples are very current for analyzing the argument structure in a speech, but for this sort of text understandable examples are important and the author uses good examples.

The book is clear and easy to read. In particular, this is a good text for community college students who often have difficulty with reading comprehension. The language is straightforward and concepts are well explained.

The book is consistent in terminology, formatting, and examples. It flows well from one topic to the next, but it is also possible to jump around the text without loosing the voice of the text.

The books is broken down into sub units that make it easy to assign short blocks of content at a time. Later in the text, it does refer to a few concepts that appear early in that text, but these are all basic concepts that must be used to create a clear and understandable text. No sections are too long and each section stays on topic and relates the topic to those that have come before when necessary.

The flow of the text is logical and clear. It begins with the basic building blocks of arguments, and practice identifying more and more complex arguments is offered. Each chapter builds up from the previous chapter in introducing propositional logic, truth tables, and logical arguments. A select number of fallacies are presented at the end of the text, but these are related to topics that were presented before, so it makes sense to have these last.

The text is free if interface issues. I used the PDF and it worked fine on various devices without loosing formatting.

1. The book contains no grammatical errors.

The text is culturally sensitive, but examples used are a bit odd and may be objectionable to some students. For instance, President Obama's speech on Syria is used to evaluate an extended argument. This is an excellent example and it is explained well, but some who disagree with Obama's policies may have trouble moving beyond their own politics. However, other examples look at issues from all political viewpoints and ask students to evaluate the argument, fallacy, etc. and work towards looking past their own beliefs. Overall this book does use a variety of examples that most students can understand and evaluate.

My favorite part of this book is that it seems to be written for community college students. My students have trouble understanding readings in the New York Times, so it is nice to see a logic and critical thinking text use real language that students can understand and follow without the constant need of a dictionary.

Reviewed by Rebecca Owen, Adjunct Professor, Writing, Chemeketa Community College on 6/20/17

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current... read more

This textbook is quite thorough--there are conversational explanations of argument structure and logic. I think students will be happy with the conversational style this author employs. Also, there are many examples and exercises using current events, funny scenarios, or other interesting ways to evaluate argument structure and validity. The third section, which deals with logical fallacies, is very clear and comprehensive. My only critique of the material included in the book is that the middle section may be a bit dense and math-oriented for learners who appreciate the more informal, informative style of the first and third section. Also, the book ends rather abruptly--it moves from a description of a logical fallacy to the answers for the exercises earlier in the text.

The content is very reader-friendly, and the author writes with authority and clarity throughout the text. There are a few surface-level typos (Starbuck's instead of Starbucks, etc.). None of these small errors detract from the quality of the content, though.

One thing I really liked about this text was the author's wide variety of examples. To demonstrate different facets of logic, he used examples from current media, movies, literature, and many other concepts that students would recognize from their daily lives. The exercises in this text also included these types of pop-culture references, and I think students will enjoy the familiarity--as well as being able to see the logical structures behind these types of references. I don't think the text will need to be updated to reflect new instances and occurrences; the author did a fine job at picking examples that are relatively timeless. As far as the subject matter itself, I don't think it will become obsolete any time soon.

The author writes in a very conversational, easy-to-read manner. The examples used are quite helpful. The third section on logical fallacies is quite easy to read, follow, and understand. A student in an argument writing class could benefit from this section of the book. The middle section is less clear, though. A student learning about the basics of logic might have a hard time digesting all of the information contained in chapter two. This material might be better in two separate chapters. I think the author loses the balance of a conversational, helpful tone and focuses too heavily on equations.

Consistency rating: 4

Terminology in this book is quite consistent--the key words are highlighted in bold. Chapters 1 and 3 follow a similar organizational pattern, but chapter 2 is where the material becomes more dense and equation-heavy. I also would have liked a closing passage--something to indicate to the reader that we've reached the end of the chapter as well as the book.

I liked the overall structure of this book. If I'm teaching an argumentative writing class, I could easily point the students to the chapters where they can identify and practice identifying fallacies, for instance. The opening chapter is clear in defining the necessary terms, and it gives the students an understanding of the toolbox available to them in assessing and evaluating arguments. Even though I found the middle section to be dense, smaller portions could be assigned.

The author does a fine job connecting each defined term to the next. He provides examples of how each defined term works in a sentence or in an argument, and then he provides practice activities for students to try. The answers for each question are listed in the final pages of the book. The middle section feels like the heaviest part of the whole book--it would take the longest time for a student to digest if assigned the whole chapter. Even though this middle section is a bit heavy, it does fit the overall structure and flow of the book. New material builds on previous chapters and sub-chapters. It ends abruptly--I didn't realize that it had ended, and all of a sudden I found myself in the answer section for those earlier exercises.

The simple layout is quite helpful! There is nothing distracting, image-wise, in this text. The table of contents is clearly arranged, and each topic is easy to find.

Tiny edits could be made (Starbuck's/Starbucks, for one). Otherwise, it is free of distracting grammatical errors.

This text is quite culturally relevant. For instance, there is one example that mentions the rumors of Barack Obama's birthplace as somewhere other than the United States. This example is used to explain how to analyze an argument for validity. The more "sensational" examples (like the Obama one above) are helpful in showing argument structure, and they can also help students see how rumors like this might gain traction--as well as help to show students how to debunk them with their newfound understanding of argument and logic.

The writing style is excellent for the subject matter, especially in the third section explaining logical fallacies. Thank you for the opportunity to read and review this text!

Reviewed by Laurel Panser, Instructor, Riverland Community College on 6/20/17

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as... read more

This is a review of Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking, an open source book version 1.4 by Matthew Van Cleave. The comparison book used was Patrick J. Hurley’s A Concise Introduction to Logic 12th Edition published by Cengage as well as the 13th edition with the same title. Lori Watson is the second author on the 13th edition.

Competing with Hurley is difficult with respect to comprehensiveness. For example, Van Cleave’s book is comprehensive to the extent that it probably covers at least two-thirds or more of what is dealt with in most introductory, one-semester logic courses. Van Cleave’s chapter 1 provides an overview of argumentation including discerning non-arguments from arguments, premises versus conclusions, deductive from inductive arguments, validity, soundness and more. Much of Van Cleave’s chapter 1 parallel’s Hurley’s chapter 1. Hurley’s chapter 3 regarding informal fallacies is comprehensive while Van Cleave’s chapter 4 on this topic is less extensive. Categorical propositions are a topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 4 and 5 provide more instruction on this, however. Propositional logic is another topic in Van Cleave’s chapter 2; Hurley’s chapters 6 and 7 provide more information on this, though. Van Cleave did discuss messy issues of language meaning briefly in his chapter 1; that is the topic of Hurley’s chapter 2.

Van Cleave’s book includes exercises with answers and an index. A glossary was not included.

Reviews of open source textbooks typically include criteria besides comprehensiveness. These include comments on accuracy of the information, whether the book will become obsolete soon, jargon-free clarity to the extent that is possible, organization, navigation ease, freedom from grammar errors and cultural relevance; Van Cleave’s book is fine in all of these areas. Further criteria for open source books includes modularity and consistency of terminology. Modularity is defined as including blocks of learning material that are easy to assign to students. Hurley’s book has a greater degree of modularity than Van Cleave’s textbook. The prose Van Cleave used is consistent.

Van Cleave’s book will not become obsolete soon.

Van Cleave’s book has accessible prose.

Van Cleave used terminology consistently.

Van Cleave’s book has a reasonable degree of modularity.

Van Cleave’s book is organized. The structure and flow of his book is fine.

Problems with navigation are not present.

Grammar problems were not present.

Van Cleave’s book is culturally relevant.

Van Cleave’s book is appropriate for some first semester logic courses.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Reconstructing and analyzing arguments

- 1.1 What is an argument?

- 1.2 Identifying arguments

- 1.3 Arguments vs. explanations

- 1.4 More complex argument structures

- 1.5 Using your own paraphrases of premises and conclusions to reconstruct arguments in standard form

- 1.6 Validity

- 1.7 Soundness

- 1.8 Deductive vs. inductive arguments

- 1.9 Arguments with missing premises

- 1.10 Assuring, guarding, and discounting

- 1.11 Evaluative language

- 1.12 Evaluating a real-life argument

Chapter 2: Formal methods of evaluating arguments

- 2.1 What is a formal method of evaluation and why do we need them?

- 2.2 Propositional logic and the four basic truth functional connectives

- 2.3 Negation and disjunction

- 2.4 Using parentheses to translate complex sentences

- 2.5 “Not both” and “neither nor”

- 2.6 The truth table test of validity

- 2.7 Conditionals

- 2.8 “Unless”

- 2.9 Material equivalence

- 2.10 Tautologies, contradictions, and contingent statements

- 2.11 Proofs and the 8 valid forms of inference

- 2.12 How to construct proofs

- 2.13 Short review of propositional logic

- 2.14 Categorical logic

- 2.15 The Venn test of validity for immediate categorical inferences

- 2.16 Universal statements and existential commitment

- 2.17 Venn validity for categorical syllogisms

Chapter 3: Evaluating inductive arguments and probabilistic and statistical fallacies

- 3.1 Inductive arguments and statistical generalizations

- 3.2 Inference to the best explanation and the seven explanatory virtues

- 3.3 Analogical arguments

- 3.4 Causal arguments

- 3.5 Probability

- 3.6 The conjunction fallacy

- 3.7 The base rate fallacy

- 3.8 The small numbers fallacy

- 3.9 Regression to the mean fallacy

- 3.10 Gambler's fallacy

Chapter 4: Informal fallacies

- 4.1 Formal vs. informal fallacies

- 4.1.1 Composition fallacy

- 4.1.2 Division fallacy

- 4.1.3 Begging the question fallacy

- 4.1.4 False dichotomy

- 4.1.5 Equivocation

- 4.2 Slippery slope fallacies

- 4.2.1 Conceptual slippery slope

- 4.2.2 Causal slippery slope

- 4.3 Fallacies of relevance

- 4.3.1 Ad hominem

- 4.3.2 Straw man

- 4.3.3 Tu quoque

- 4.3.4 Genetic

- 4.3.5 Appeal to consequences

- 4.3.6 Appeal to authority

Answers to exercises Glossary/Index

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This is an introductory textbook in logic and critical thinking. The goal of the textbook is to provide the reader with a set of tools and skills that will enable them to identify and evaluate arguments. The book is intended for an introductory course that covers both formal and informal logic. As such, it is not a formal logic textbook, but is closer to what one would find marketed as a “critical thinking textbook.”

About the Contributors

Matthew Van Cleave , PhD, Philosophy, University of Cincinnati, 2007. VAP at Concordia College (Moorhead), 2008-2012. Assistant Professor at Lansing Community College, 2012-2016. Professor at Lansing Community College, 2016-

Contribute to this Page

Effectiviology

Logical Fallacies: What They Are and How to Counter Them

- A logical fallacy is a pattern of reasoning that contains a flaw, either in its logical structure or in its premises.

An example of a logical fallacy is the false dilemma , which is a logical fallacy that occurs when a limited number of options are incorrectly presented as being mutually exclusive to one another or as being the only options that exist, in a situation where that isn’t the case. For instance, a false dilemma occurs in a situation where someone says that we must choose between options A or B, without mentioning that option C also exists.

Fallacies, in their various forms, play a significant role in how people think and in how they communicate with each other, so it’s important to understand them. As such, the following article serves as an introductory guide to logical fallacies, which will help you understand what logical fallacies are, what types of them exist, and what you can do in order to counter them successfully.

Examples of logical fallacies

One example of a logical fallacy is the ad hominem fallacy , which is a fallacy that occurs when someone attacks the source of an argument directly, without addressing the argument itself. For instance, if a person brings up a valid criticism of the company that they work in, someone using the ad hominem fallacy might reply by simply telling them that if they don’t like the way things are done, then that’s their problem and they should leave.

Another example of a logical fallacy is the loaded question fallacy , which occurs when someone asks a question in a way that presupposes an unverified assumption that the person being questioned is likely to disagree with. An example of a loaded question is the following:

“Can you get this task done for me, or are you too busy slacking off?”

This question is fallacious, because it has a flawed premise, and specifically because it suggests that if the person being questioned says that they can’t get the task done, then that must be because they’re too busy slacking off.

Finally, another example of a logical fallacy is the argument from incredulity , which occurs when someone concludes that since they can’t believe that a certain concept is true, then it must be false, and vice versa. For instance, this fallacy is demonstrated in the following saying:

“I just can’t believe that these statistics are true, so that means they must be false.”

In this case, the speaker’s reasoning is fallacious, because their premises are flawed, and specifically their assumption that if they can’t believe the statistics that they’re shown are true, then that must mean that the statistics are false.

Formal and informal logical fallacies

There are two main types of logical fallacies:

- Formal fallacies. A formal logical fallacy occurs when there is a flaw in the logical structure of an argument, which renders the argument invalid and consequently also unsound . For example, a formal fallacy can occur because the conclusion of the argument isn’t based on its premises.

- Informal fallacies. An informal logical fallacy occurs when there is a flaw in the premises of an argument, which renders the argument unsound , even though it may still be valid . For example, an informal fallacy can occur because the premises of an argument are false , or because they’re unrelated to the discussion at hand.

Therefore, there are two main differences between formal and informal logical fallacies. First, formal fallacies contain a flaw in their logical structure , while informal fallacies contain a flaw in their premises . Second, formal fallacies are invalid patterns of reasoning (and are consequently also unsound), while informal fallacies are unsound patterns of reasoning, but can still be valid.

For instance, the following is an example of a formal fallacy :

Premise 1: If it’s raining, then the sky will be cloudy. Premise 2: The sky is cloudy. Conclusion: It’s raining.

Though both the premises in this example are true, the argument is invalid , since there is a flaw in its logical structure.

Specifically, premise 1 tells us that if it’s raining, then the sky will be cloudy, but that doesn’t mean that if the sky is cloudy (which we know it is, based on premise 2), then it’s necessarily raining. That is, it’s possible for the sky to be cloudy, without it raining, which is why we can’t reach the conclusion that is specified in the argument, and which is why this argument is invalid, despite the fact that its premises are true.

On the other hand, the following is an example of an informal fallacy :

Premise 1: The weatherman said that it’s going to rain next week. Premise 2: The weatherman is always right. Conclusion: It’s going to rain next week.

Here, the logical structure of the argument is valid. Specifically, since premise 1 tells us that the weatherman said that it’s going to rain next week, and premise 2 tells us that the weatherman is always right, then based on what we know (i.e. on these premises), we can logically conclude that it’s going to rain next week.

However, there is a problem with this line of reasoning, since our assumption that the weatherman is always right (premise 2) is false . As such, even though the logical structure of the argument is valid, the use of a flawed premise means that the overall argument is unsound .

Overall, a sound argument is one that has a valid logical structure and true premises. A formal logical fallacy means that the argument is invalid, due to a flaw in its logical structure, which also means that it’s unsound. An informal logical fallacy means that the argument is unsound, due to a flaw in its premises, even though it has a valid logical structure.

Example of a formal logical fallacy

As we saw above, a formal fallacy occurs when there is an issue with the logical structure of an argument, which renders the argument invalid.

An example of a formal logical fallacy is the masked-man fallacy , which is committed when someone assumes that if two or more names or descriptions refer to the same thing, then they can be freely substituted with one another, in a situation where that’s not the case. For example:

Premise 1: The citizens of Metropolis know that Superman saved their city. Premise 2: Clark Kent is Superman. Conclusion: The citizens of Metropolis know that Clark Kent saved their city.

This argument is invalid, because even though Superman is in fact Clark Kent, the citizens of Metropolis don’t necessarily know Superman’s true identity, and therefore don’t necessarily know that Clark Kent saved their city. As such, even though both the premises of the argument are true, there is a flaw in the argument’s logical structure, which renders it invalid.

Example of an informal logical fallacy

As we saw above, an informal fallacy occurs when there is a flaw in the premises of an argument, which renders the argument unsound.

An example of an informal logical fallacy is the strawman fallacy , which occurs when a person distorts their opponent’s argument, in order to make it easier to attack. For example:

Alex: I think we should increase the education budget. Bob: I disagree, because if we spend the entire budget on education, there won’t be any money left for other essential things.

Here, Bob’s argument is valid from a formal, logical perspective: if we spend the entire budget on education, there won’t be anything left to spend on other things.

However, Bob’s reasoning is nevertheless fallacious, because his argument contains a false, implicit premise, and namely the assumption that when Alex suggests that we should increase the education budget, he means that the entire budget should be allocated to education. As such, Bob’s argument is unsound, because it relies on flawed premises, and counters an irrelevant point that his opponent wasn’t trying to make.

Fallacious techniques that aren’t logical fallacies

The term ‘fallacious’ has two primary meanings:

- Containing a logical fallacy.

- Tending to deceive or mislead.

Accordingly, some misleading rhetorical techniques and patterns of reasoning can be described as “fallacious”, even if they don’t contain a logical fallacy.

For example, the Gish gallop is a fallacious debate technique, which involves attempting to overwhelm your opponent by bringing up as many arguments as possible, with no regard for the relevance, validity, or accuracy of those arguments. Though a Gish gallop may have some arguments that contain logical fallacies, it isn’t a single argument by itself, and therefore isn’t considered a logical fallacy. However, because its overall argumentation pattern revolves around the intent to deceive, this technique is said to be fallacious.

In this regard, note that logical fallacies, in general, tend to include a form of reasoning that is not only logically invalid or unsound in some way, but that is also misleading.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that fallacies and other fallacious techniques aren’t always used with the intention of misleading others. Rather, people often use fallacious arguments unintentionally, both when they’re talking to other people, as well as when they conduct their own internal reasoning process, because the fact that such arguments are misleading can lead those who use them to not notice that they’re flawed in the first place.

Logical fallacies are different from factual errors

It’s important to note that logical fallacies are errors in reasoning, rather than simple factual errors.

For example, though the statement “humans are birds” is flawed, that’s because it contains a simple factual error, rather than a logical fallacy. Conversely, the argument “humans have eyes, and birds also have eyes, therefore humans are birds” contains a logical fallacy, since there is a flaw in its logical structure, which renders it invalid.

How to counter logical fallacies

To counter the use of a logical fallacy, you should first identify the flaw in reasoning that it contains, and then point it out and explain why it’s a problem, or provide a strong opposing argument that counters it implicitly.

For example, consider a situation where someone uses the appeal to nature , which is an informal logical fallacy that involving claiming that something is either good because it’s considered ‘natural’, or bad because it’s considered ‘unnatural’.

Once you’ve identified the use of the fallacy, you can counter it by explaining why its premises are flawed. To achieve this, you can provide examples that demonstrate that things that are “natural” can be bad and that things that are “unnatural” can be good, or you can provide examples that demonstrate the issues with trying to define what “natural” and “unnatural” mean in the first place.

The steps in this approach, where you first identify the use of the fallacy and then either explain why it’s a problem or provide strong counterarguments, are generally the main ones to follow regardless of which fallacy is being used. However, there is some variability in terms of how you implement these steps when it comes to different fallacies and different circumstances, and an approach that will work well in one situation may fail in another.

For example, while a certain approach might work well when it comes to resolving a formal fallacy that you’ve used unintentionally in your own reasoning process, the same approach might be ineffective when it comes to countering an informal fallacy that was used intentionally by someone else for rhetorical purposes.

Finally, it’s also important to keep in mind that sometimes, when responding to the use of fallacious reasoning, dismantling the logic behind your opponent’s reasoning and highlighting its flaws might not work. This is because, in practice, human interactions and debates are highly complex, and involve more than just exchanging logically sound arguments with one another.

Accordingly, you should accept the fact that in some cases, the best way to respond to a logical fallacy in practice isn’t necessarily to properly address it from a logical perspective. For example, your best option might be to modify your original argument in order to counter the fallacious reasoning without explicitly addressing the fact that it’s fallacious, or your best option might be to refuse to engage with the fallacious argument entirely.

Account for unintentional use of fallacies

When you counter fallacies that other people use, it’s important to remember that not every use of a logical fallacy is intentional, and to act accordingly, since accounting for this fact can help you formulate a more effective response.

A useful concept to keep in mind in this regard is Hanlon’s razor , which is a philosophical principle that suggests that when someone does something that leads to a negative outcome, you should avoid assuming that they acted out of an intentional desire to cause harm, as long as there is a different plausible explanation for their behavior. In this context, Hanlon’s razor means that, if you notice that someone is using a logical fallacy, you should avoid assuming that they’re doing so intentionally, as long as it’s reasonable to do so.

In addition, it’s important to remember that you too might be using logical fallacies unintentionally in your thinking and in your communication with others. To identify cases where you are doing this, try to examine your reasoning, and see if you can identify any flaws, either in the way that your arguments are structured, or in the premises that you rely on in order to make those arguments. Then, adjust your reasoning accordingly, in order to fix these flaws.

Make sure arguments are fallacious before countering

Before you counter an argument that you think is fallacious, you should make sure that it is indeed fallacious, to the best of your ability.

There are various ways to do this, including slowing down your own reasoning process so you can properly think through the argument, or asking the person who proposed the argument to clarify their position.

The approach of asking the other person to clarify their position is highly beneficial in general, because it helps demonstrate that you’re truly interested in what the other person has to say. Furthermore, in cases where the argument in question does turn out to be fallacious, this approach can often help expose the issues with it, and can also help the other person internalize these issues, in a way that you won’t always be able to achieve by pointing them out yourself.

Finally, note that a useful tool to remember in this regard is the principle of charity , which is a philosophical principle that denotes that, when interpreting someone’s statement, you should assume that the best possible interpretation of that statement is the one that the speaker meant to convey. In this context, the principle of charity means that you should not attribute falsehoods, logical fallacies, or irrationality to people’s argument, when there is a plausible, rational alternative available.

Remember fallacious arguments can have true conclusions

It’s important to keep in mind that even if an argument is fallacious, it can still have a true conclusion. Assuming that just because an argument is fallacious then its conclusion must necessarily be false is a logical fallacy in itself, which is known as the fallacy fallacy .

For instance, consider the following example of a formal logical fallacy (which we saw earlier, and which is known as affirming the consequent ):

Premise 1: If it’s raining, then the sky will be cloudy. Premise 2: The sky is cloudy. Conclusion: It’s raining.

This argument is logically invalid, since we can’t be sure that its conclusion is true based on the premises that we have (because it’s possible that the sky is cloudy but that it’s not raining at the same time). However, even though the argument itself is flawed, that doesn’t mean that its conclusion is necessarily false. Rather, it’s possible that the conclusion is true and that it is currently raining; we just can’t conclude this based on the premises

The same holds for informal fallacies. For example, consider the following argument:

Alex: It’s amazing how accurate this personality test I took is. Bob: No it isn’t, it’s pure nonsense.

Here, Bob is using an appeal to the stone , which is a logical fallacy that occurs when a person dismisses their opponent’s argument as absurd, without actually addressing it, or without providing sufficient evidence in order to prove its absurdity. However, even though Bob’s argument is fallacious, that doesn’t mean that its conclusion is wrong; it’s possible that the personality test in question is indeed nonsense, we just can’t tell whether that’s the case based on this argument alone.

Overall, the important thing to understand is that an argument can be fallacious and still have a conclusion that is factually correct. To assume otherwise is fallacious, which is why you shouldn’t discount people’s conclusions simply because the argument that they used to reach those conclusions contains a logical fallacy.

The difference between logical fallacies and cognitive biases

While logical fallacies and cognitive biases appear to be similar to each other, they are two different phenomena. Specifically, while logical fallacies are flawed patterns of argumentation , and are therefore a philosophical concept, cognitive biases are systematic errors in cognition , and are therefore a psychological concept.

Cognitive biases often occur at a more basic level of thinking, particularly when they’re rooted in people’s intuition, and they can lead to the use of various logical fallacies.

For example, the appeal to novelty is a logical fallacy that occurs when something is assumed to be either good or better than something else, simply because it’s perceived as being new and novel.

In some cases, people might use this fallacy due to a cognitive bias that causes them to instinctively prefer things that they perceive as newer. However, people can experience this instinctive preference for newer things without it leading to the use of the appeal to novelty, in cases where they recognize this preference and account for it properly. Furthermore, people can use arguments that rely on the appeal to novelty even if they don’t experience this instinctive preference, and even if they don’t truly believe in what they’re saying.

Overall, the main difference between logical fallacies and cognitive biases is that logical fallacies are a philosophical concept, that has to do with argumentation , while cognitive biases are a psychological concept, that has to do with cognition . In some cases, there is an association between cognitive biases and certain logical fallacies, but there are many situations where one appears entirely without the other.

Summary and conclusions

- To counter the use of a logical fallacy, you should first identify the flaw in reasoning that it involves, and then point it out and explain why it’s a problem, or provide a strong opposing argument that counters it implicitly.

- Note that there is some variability in terms of how you should counter different fallacies under different circumstances, and an approach that will work well in one situation may fail in another.

- When responding to the use of a logical fallacy, it’s important to make sure that it’s indeed a fallacy, to remember that the use of the fallacy might be intentional, and to keep in mind that just because an argument is fallacious doesn’t mean that its conclusion is necessarily wrong.

- Certain rhetorical techniques and patterns of reasoning can be described as “fallacious” even if they don’t contain a logical fallacy, because they’re used with the intent to deceive or mislead listeners.

Other articles you may find interesting:

- False Premise: When Arguments Are Built on Bad Foundations

- False Dilemmas and False Dichotomies: What They Are and How to Respond to Them

- The Fallacy Fallacy: Why Fallacious Arguments Can Have True Conclusions

Everyday Psychology. Critical Thinking and Skepticism.

What are Logical Fallacies? | Critical Thinking Basics

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning or flawed arguments that can mislead or deceive. They often appear plausible but lack sound evidence or valid reasoning, undermining the credibility of an argument. These errors can be categorized into various types, such as ad hominem attacks, strawman arguments, and false cause correlations.

Impact on Critical Thinking, Communication, and Social Interactions

The presence of logical fallacies hampers critical thinking by leading individuals away from rational and evidence-based conclusions. In communication, they can create confusion, weaken the persuasiveness of an argument, and hinder the exchange of ideas.

In social interactions, reliance on fallacious reasoning can strain relationships, impede collaboration, and contribute to misunderstandings.

Benefits of Identifying and Managing Logical Fallacies

Learning to identify logical fallacies enhances critical thinking skills, enabling individuals to analyze arguments more effectively and make informed decisions. In communication, recognizing fallacies empowers individuals to construct more compelling and convincing arguments, fostering clearer and more meaningful exchanges.

Moreover, the ability to manage logical fallacies promotes healthier social interactions by minimizing misunderstandings, encouraging constructive dialogue, and fostering a more intellectually robust and collaborative environment.

RETURN TO THE MAIN RESOURCE PAGE: CRITICAL THINKING BASICS

Share this:

9 Logical Fallacies That You Need to Know To Master Critical Thinking

When you learn about logic, language becomes a game you can win.

William James, who was known as the grandfather of psychology, once said: “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.” All of us think, every day. But there’s a difference between thinking for thinking’s sake, and thinking in a critical way. Deliberate, controlled, and reasonable thinking is rare.

There are multiple factors that are impairing people’s ability to think critically, from technology to changes in education. Some experts have speculated we’re approaching a crisis of critical thinking , with many students graduating “without the ability to construct a cohesive argument or identify a logical fallacy.”

RELATED: How to Tell if ‘Political Correctness’ Is Hurting Your Mental Health

That’s a worrying trend, as critical thinking isn’t only an academic skill, but essential to living a high-functioning life. It’s the process by which to arrive at logical conclusions. And in through that process, logical fallacies are a significant hazard.

This article will explore logical fallacies in order to equip you with the knowledge on how to think in skillful ways, for the biggest benefits. As a result, you’ll be able to detect deception of flawed logic, in others, and yourself. And you’ll be equipped to think proper thoughts, rather than simply rearrange prejudices.

What Is a Logical Fallacy?

The study of logic originates back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 b.c.e), who started to systematically identify and list logical fallacies. The origin of logic is linked to the Greek logos , which translates to language, reason, or discourse. Logical fallacies are errors of reason that invalidate an argument. The use of logical fallacies changes depending on a person’s intention. Although for many, they’re unintentional, others may deliberately use logical fallacies as a type of manipulative behavior .

Detecting logical fallacies is crucial to improve your level of critical thinking, to avoid deceit, and to spot poor reasoning; within yourself and others. The influential German philosopher Immanuel Kant once said; “All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.”

RELATED: Fundamental Attribution Error: Definition & Examples

Throughout history, the world’s greatest thinkers have promoted the value of reasoning. Away from academia, reason is the ability to logically process information, and arrive at an accurate conclusion, in the quest for truth. Striving to be more reasonable or calm under pressure is a virtuous act. It’s a noble pursuit, one which in its nature will inspire your personal development, and allow you to become the best version of yourself.

Why Critical Thinking Is Important

It seems like humanity has never been so polarized, separated into different camps and stances; Democrats vs. Liberals, vegans vs. meat eaters, vaccinated vs. unvaccinated, pro-life vs. pro-choice. There’s nothing inherently wrong with thinking critically, and taking a stand. However, what is unusual is the tendency for people to lean into one extreme or the other, neglecting to explore gray areas or complexity.

Many of the positions people take are chosen for them. It takes a lot of effort to research a point of view. And even then, we’re faced with the challenge of information overload, fake news, conspiracy, and even credible news which is dismissed as conspiracy. Far from academic debates or politicians facing off during leadership races, the ability to share respectful dialogue is an essential part of understanding our place in the world, and maintaining human relationships.

The hot topics facing humanity aren’t going to be resolved by reactivity or over-emotionality . There should be room for all sorts of emotions to surface; it’s understandable to feel anger, grief, anxiety, etc, faced with global events. But critical thinking asks for a more reasoned, calm consideration, not getting completely carried away with emotions, but appealing to higher judgment.

Examples of When to Use Critical Thinking

It’s not always clear why critical thinking is so valuable. Isn’t it only useful for education, philosophy, science, or politics? Not quite. When applied appropriately, logic has a universal appeal in life. Examples include:

- Problem-solving : “The problem is not that there are problems,” wrote psychiatrist Theodore Isaac Rubin, “the problem is expecting otherwise, and thinking that having problems is a problem.” Life is full of problems. Fortunately, that means life is full of opportunities to problem solve. Critical thinking is an essential problem-solving skill, from managing your time to organizing your finances.

- Making optimal decisions : the more logical you are, and the less you fall into logical fallacies, the better your decision-making becomes . Decisions are the steps towards your goals, each decision making you closer to, or away from, what you really desire.

- Understanding complex subjects : with attention spans reducing due to social media and technology, it’s becoming rare to take time to attempt to understand complex topics, away from repeating what others have said. Whether through self-study or to comprehend global events, critical thinking is essential to understand complexity.

- Improving relationships : adding a dose of logic to your interactions will allow you to make better choices in relationships. Many “messy” forms of communication, from guilt-tripping to passive aggression, are illogical. By tapping into a more balanced point of view, you’ll better overcome conflict, argue your point (when necessary), or explain the way you feel.

The Most Common Logical Fallacies

When you begin to explore logical fallacies, language becomes a game. There’s a sense of having a cheat sheet in communication, understanding the underlying dynamics at play. Of course, it’s not as straightforward as a mechanical understanding — emotional intelligence, and non-verbal body language has a role to play, too. We’re humans, not computers. But gaining mastery of logic puts you ahead of the majority of people, and helps you avoid cognitive bias.

What’s more, most people fall into logical fallacies without being aware. Once you can detect these mechanisms, within yourself and with others, you’ll have an upper hand in many key areas of life, not least in a professional setting, or in any place you need to persuade or argue a point. The list is ever-growing and vast, but below are the most common logical fallacies to get the ball rolling:

1. Ad Hominem

Originating from a Latin phrase meaning “to the person,” ad hominem is an attack on the person, not the argument. This has a twofold impact — it deflects attention away from the validity of the argument, and second, it can provoke the person to enter a defensive mindset. If you’re aware of this fallacy, it can keep you from taking the bait, and instead keeping the focus on the argument.