Food Research Paper

This sample food research paper features: 7300 words (approx. 24 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 79 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Food as Medicine

Domestication of plants and animals, how domestication occurred, domestication of plants, domestication of animals, the present, future directions.

- Bibliography

More Food Research Papers:

- Food Ethics Research Paper

- Food Security Research Paper

- History of Food Research Paper

- Sociology of Food Research Paper

Introduction

By 2009 the world population has reached 6.7 billion people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau (2009). In 1900, there were “only” 1.65 billion people on earth, 2.5 billion by 1950, with a projected 9 billion by 2050. While a number of factors have affected this exponential increase, not the least of which is reallocation of resources and labor (Boone, 2002), the abundance and distribution of food has played a major role, spurring technology to increase production and distribution. The result is the food crisis emerging in this early part of the 21st century.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

Leading to this crisis, there are four major “events” in the history of food use. The first is cooking—the act of using heat to transform a substance from one state to another. This is an emergent behavior, as no other primate does anything like it. The second event, equally as dramatic, is the domestication of plants and animals; the outcome has been increasing control of resources (plants, animals) to the point of manufacture. This manufacture has included husbandry procedures, breeding, sterilization, and the like—and most recently, genetic engineering. The third event, directly related to manufacture, is the dispersion of foods throughout the world, which is a continuous process beginning at the time of domestication and continuing today, albeit now in the form of globalization. The “typical” diets of China, Italy, France, or anywhere are the result of diffusion and dispersion of these domesticated plants or animals, known as domesticates (Sokolov, 1991). The fourth event is the industrialization of food. This is an ongoing event beginning in the latter part of the 18th century with the invention of canning (Graham, 1981) and continuing today in the form of frozen meals, new packaging materials, ways of reconstituting foods, and, in the near future, creating animal “meat” by tissue engineering (Edelman, McFarland, Mironov, & Matheny, 2005). The purpose of this research paper is to describe the events concerning the human use of food in the past (prehistory to the 1700s) and present, and speculate on the trends for the future.

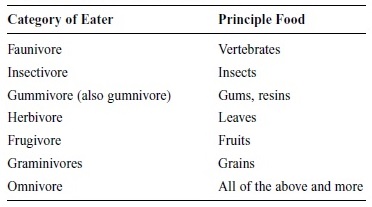

We are primates, descended from a long line that began around 80 million years ago (Ackermann & Cheverud, 2004). As a group, primates are omnivores and consume nuts, seeds, leaves, stalks, pith, underground roots and storage organs, flowers, insects, lizards, birds, eggs, and mammals. The source of nutrients, or its emphasis, varies from group to group so that it is possible to classify primates by food intake. Table 1 illustrates these groups.

Prosimians, or lower primates, tend to be insect eaters while certain types of these primates prefer lizards or small invertebrates; monkeys—both Old and New World—rely on fruits with a significant input from insects or small vertebrates. Apes eat from a variety of larders (food supplies) depending on type: orangutans eat fruit, gorillas eat stalks and pith, and chimps eat fruit and hunt for mammals—but none eat one type to the exclusion of all else. Physical specializations to extract nutrients from the source vary greatly. Some primates ferment their food; others reingest it.

The shape of teeth and jaws, and the length of gut and digestive tract, also affect different emphases of diet. Fruit eaters, for example, are equipped with molars that are not shaped for crushing or grinding, but are small in relation to their body size (Kay, 2005). Some leaf eaters, like colobines or howler monkeys, have sacculated stomachs containing bacteria that aid in digestion. One type of lemur is probably coprophagous; that is, like rabbits, it ingests its own waste pellets to extract semidigested nutrients. The length of the gut in primates that eat any kind of animal is 4 to 6 times its body length, while that of a leaf eater is 10 to 30 times its body length (Milton, 1993).

Primates, unlike some other mammals, require certain vitamins. The most important substances, vitamins B 12 and C, must be obtained from outside sources. In the case of B 12 , it must be extracted from animals including insects (Wakayama, Dillwith, Howard, & Blomquist, 1984), and for vitamin C, from fruits and a little from muscle meat. Genes controlling the manufacture of these substances were reassigned ( exapted ), as it were, to other functions when the anthropoid group of monkeys, apes, and humans split from prosimians. The genetic information is affirmed by the fact that some prosimian relatives of the earliest primates are still able to synthesize these substances (Milton, 1993).

The model for human evolution derives from the behavior and physiology of African apes, particularly the two kinds of chimpanzees: the bonobo and the common chimpanzee. These primates are more active than either gorillas or orangutans and a good deal more sociable than the orangutan, also known as the red giant of Asia. Their choice of diet is considered an important factor in their activity, as larger primates tend to rely on leaves and foliage, as do gorillas, who have a range of only around 300 meters per day. Fruit eaters are not only more active than foliage eaters, they are more eclectic in their diet, including nuts, seeds, berries, and especially insects of some sort because fruits are an inadequate source of protein (Rothman, Van Soest, & Pell, 2006). They are also considered to be more “intelligent,” as witnessed by recent studies of New World capuchin monkeys, and Old World macaques and chimpanzees. Chimps can take in as much as 500 grams of animal protein a week (Goodall, 1986; Milton, 1993).

Animal protein is considered high-quality food, and the importance of high-quality protein to the evolution of the human brain cannot be underestimated (Leonard, 2002). From only 85 grams (3.5 ounces) of animal protein, 200 kilocalories are obtained. In comparison, this amount of fruit would provide about 100 kilocalories, and leaves would provide considerably less—about 20 kilocalories. The daily range of chimpanzees can extend to about 4 kilometers per day, and their societies are highly complex social groups. It is this complexity that enables them to conduct their hunts, coordinating members as they approach their prey using glances, piloerection, and pointing. Since primates evolved from insectivores at a time when fruits and flowers were also evolving, their ability to exploit this new resource demonstrates the most important characteristic of primates: flexibility.

Primates can readily adapt to extreme conditions like drought. Under harsh conditions, primates will seek (as indeed, humans do) what are called fallback foods. These are foods like bark, or even figs, that are less desirable because they lack ingredients such as fats or sweet carbohydrates (Knott, 2005). Primates have a remarkable repertoire of methods to deal with changes in food availability: They can change their diets; they can change their location; they change their behavior according to the energy they take in (Brockman, 2005).

This flexibility in adapting behavior to changing circumstances was a decisive advantage for the primates, as they implemented the underlying knowledge about resources with the ability to remember locations of specific foods. Equally as important is the ability to evaluate the probability of encountering predators in these locations. The ability to adapt to environmental and social changes depends not only on genetic evolution but, as Hans Kummer (1971) noted, on cultural processes arrived at through group living. The behavioral mode responds more quickly to dynamic situations than does physical evolution.

Gathering, Hunting, and the Beginnings of Food Control

The ancestors of humans continued the food-gathering techniques of their primate predecessors, gathering invertebrates and small vertebrates, as well as plant materials, in the trees, on the ground, and below ground. As prey gets larger, the techniques shift from one individual working to a concerted, group effort. The former is seen in the behavior of capuchin monkeys and baboons, and the more sophisticated planning and coordination is well documented among chimpanzees. With greater reliance on meat, there are more changes in the primate body—the more reliance on protein, the more prevalence of the hormone ghrelin. Ghrelin is active in promoting the organism to eat, and therefore causes an increase in body mass and the conservation of body fat (Cummings, Foster-Schubert, & Overduin, 2005).

The secretion of ghrelin stimulates the growth hormone as it increases body mass. Human brains require huge amounts of energy—as much as 25% of our total energy needs. Most mammals, in contrast, require up to about 5%, and our close relatives, the other nonhuman primates, need about 10% at the most (Leonard, 2002; Leonard & Robertson, 1992, 1994; Paabo, 2003). The brains of our other close relatives, the australopiths, were apelike, measuring about 400 cubic centimeters (cc) at 4 mya. Our ancestor, Homo, experienced rapid brain expansion from 600 cc in Homo habilis at 2.5 mya, to 900 cc in Homo erectus in only a half-million years. This value is just below the lowest human value of 950 cc.

Somewhere near this period of time, Homo erectus began using fire to cook. While the association with fire may have been long-standing (Burton, 2009), its use in transforming plants and animals from one form to a more digestible one appears to have begun after 2 mya, and according to some, the date of reckoning is 1.9 mya (Platek, Gallup, & Fryer, 2002).

Tubers are underground storage organs (USOs) of plants. They became more abundant after about 8.2 mya, when the impact of an asteroid cooled the earth creating an environment favoring the evolution of C4 plants over C3 ones (trees and some grasses). The USOs are often so hard or so large that they cannot easily be eaten, and contain toxic substances. Heat from a fire softens the USO, making cell contents accessible, and it also renders the toxic compounds harmless.

For some years, Richard Wrangham and coworkers (Wrangham & Conklin-Brittain, 2003; Wrangham, 2001; Wrangham, McGrew, de Waal, & Heltne, 1994) have been proposing that cooking was the major influence in human evolution. As explained, the application of heat made USOs more nutritively accessible. Recently, in an experiment to test this hypothesis, captive chimpanzees, gorillas, bonobos, and orangutans were offered cooked and uncooked carrots, and sweet and white potatoes. Apparently there was a strong tendency for the great apes to prefer softer items (Wobber, Hare, & Wrangham, 2008). While monkeys dig for corms and the like (Burton, 1972), the finding that chimpanzees use tools to dig up USOs (Hernandez-Aguilar, Moore, & Pickering, 2007) underscores the appeal of this hypothesis. In addition, there is evidence that Homo had already been using tools for over a half-million years when cooking probably began. The inclusion of “meat” in cooking had to have begun by 1.8 mya because there is substantial evidence of big-game hunting by this date. Equally important to Wrangham and colleagues is the consideration that the jaws and teeth of these members of Homo could not have dealt with the fibrousness and toughness of mammalian meat (Wrangham & Conklin-Brittain, 2003). This is despite the fact that apes and monkeys regularly partake of raw flesh; all primates eat insects, and many eat small vertebrates like lizards.

Insects are not termed meat, although their nutritive value is comparable. Certainly the early Homo was eating mammals. Recent evidence from Homo ergaster shows that this hominin was infested with tapeworms by 1.7 mya and that these parasites came from mammals (Hoberg, Alkire, de Queiroz, & Jones, 2001). The remains suggest that either the cooking time at this site was too short, or the temperature was not high enough to kill the parasitic larvae, but also that these hominins were utilizing fire as an instrument of control in their environment. The knowledge base of our ancestors was extensive: It had to be for them to prosper, and it included knowledge of medicinal qualities of plants in their habitat.

It is now well attested that animals self-medicate (Engel, 2002; Huffman, 1997). Plants are used externally as, for example, insect repellent or poultices on wounds, and internally against parasites and gastrointestinal upsets. They may also regulate fertility, as recent evidence suggests that the higher the fats versus protein or carbohydrate, the more males are born (Rosenfeld et al., 2003), and the higher the omega-6 versus omega-3, the more females are born (Fountain et al., 2007; Green et al., 2008). The fact that the animals seem to know the toxic limits of the substances they use and consume is also significant (Engel, 2002).

As knowledge is passed from generation to generation, it crosses lines of species. Homo erectus became Homo sapiens, and their knowledge base was a compendium of all that had gone before that could be remembered. Hence, the knowledge base included the breeding habits of plants and animals, their annual cycles, and where and when to find them, as well as what dangers were associated with them.

Somewhere between the advent of Homo sapiens, at the earliest around 250,000 years ago, and first evidence around 15 kya, this knowledge became translated into domestication. The process of domestication was first delineated by Zeuner (1963). Foreshortening of the muzzle, lightening of the fur, and crowding of the teeth are characteristic of this condition. There are even changes in the part of the brain relating to fear, as there is a relaxation toward the fearful stimulus—in this case with humans— under domestication (Hare & Tomasello, 2005). Because human care is extended to the domesticate, a relaxation of natural selection occurs as nonadaptive traits are supported. This process is seen in sheep, and laboratory and pet mice, as well as dogs, and whatever other animal has been domesticated.

Evidence of diets having components of domestication is attested to by microwear patterns, detected with an electron microscope. These can be found on teeth; isotope analysis of the ratio of C3 to C4 plants, since the latter include more domesticated plants; biomechanics; and anatomical characteristics, such as tooth size or length of shearing crests on molars. Researchers also experiment with various kinds of abrasion and compare these to the “unknown”—the fossil. Biomechanics, an engineering type of study, analyzes forces and examines tooth and bone under the conditions of different diets.

While earlier in our history, only about 30% of the dietary intake would have come from eating organisms that ate C4 plants, under domestication, the number of animals as well as C4 plants increased. This is known from isotope analysis, which evaluates how CO 2 is taken up by plants, and which can estimate the proportion of C3 to C4 plants in the diet. What’s more, the nature of the diet itself can be understood.

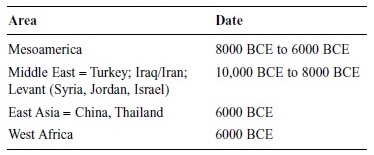

Descriptions of domestication follow different theoretical models. Terms like center, zone, or even homeland relate to a view of process and dispersion. How many separate areas of independent domestication there were relative to subareas that received the domesticate or knowledge on how to domesticate also depends on the scholar. A general consensus is that there were seven separate areas where domestication took place: the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Mesoamerica, South America, eastern North America, and from the Near East to Europe, with firm evidence dating from between 12,000 and 10,000 BCE in the Fertile Crescent of west Asia. The time of transition between hunting and gathering and cultivation of plants and animals is well documented at a number of sites. One, in the Levant, at Ohalo II near Haifa, has evidence for the earliest brush dwellings (Nadel, 2003) and is fairly typical of this transition period. It is dated radiometrically to 19,500 BP (or radiocarbon years before present, RCYBP), which gives a calibrated date of between 22,500 and 23,500 BP (Nadel, 2003). In this Upper Paleolithic, or Epipaleolithic site, evidence from dentition suggests an abrasive diet emphasizing food based on cereals, fish, and a variety of local animals, especially gazelle. In addition to wild barley, wheat, and fruits, small-grained grasses were well represented in the remains (Weiss, Wetterstrom, Nadel, & Bar-Yosef, 2004). The Ohalo II people occupied the site for at least two seasons, likely spring and autumn (Kislev, Nadel, & Carmic, 1992) and perhaps throughout the year (Bar-Yosef, 1998) in brush huts along the lakeshore. These sites at the end of the Upper Paleolithic along the Mediterranean, and in Europe during the Mesolithic, indicate that plants were relied on as dietary objects and may well have been cared for around campsites to ensure their growth.

The specifics of how domestication occurred in each region differ (Bar-Yosef, 1998). Classical theories seeking to analyze the how and why of domestication focus on the environment, population growth, the organization and management of small-scale societies, trade, and changes in the daily schedule (Sutton & Anderson, 2004) . Extending in time from the 18th century, the discussion of these is too complex and lengthy to be included here. More recently, Boone (2002) invoked an energy-budget model, consonant with contemporary notions of evolutionary demography and ecology. A scenario then emerged based on archaeological evidence that the climate was becoming increasingly unpredictable. These dramatic changes in climate, some of them a result of asteroids (Firestone et al., 2007), caused big game to decrease. The subsistence base changed to accommodate the lessened availability, requiring the diet to become more diverse. Fishing became important as groups moved to rich coastal areas, especially along the Mediterranean (e.g., the Levant and Turkey). Activities changed as a consequence, since traditional jobs were now replaced and the need to “follow the herds” was replaced with sedentism, itself a complex phenomenon defined by activities at a given locale as well as infrastructure developed there (Bar-Yosef, 1998).

While populations over most of prehistory had overall zero growth, the cultural processes that emerged with hominines affected mortality and population increase (Boone, 2002), culturally “buffering” local climatic and environmental changes. Brush huts and other shelters are emblematic of this. Larger groups encouraged specializations to emerge. A concomitant to climate change was the decrease in big game. These had provided substantial amounts of protein, and some, because of their size, had little or no predator response, making them particularly easy for small people with limited technology to overcome (Surovell, Waguespack, & Brantingham, 2005). So proficient had the hominines become that these efforts apparently caused massive extinctions of megafauna worldwide, in particular, proboscideans (Alroy, 2001; Surovell et al., 2005).

The actual effect humans have had on megafauna elsewhere, however, remains controversial (Brook & Bowman, 2002), and the demise of big game may indeed owe more to an extraterrestrial impact around 12 kya and its concomitant effect on climate (Firestone et al., 2007). At the same time, humans were obliged to include in their larder a wide variety of foods that either were not as palatable or required a great deal more effort for the caloric return— rather like the choices of fallback foods that nonhuman primates make under poor environmental conditions. The heads of cereals (wheat or barley, for example) need to be gathered, dried, ground, and boiled to make satisfactory “bread.” They can be, and are, eaten whole, with the consequence of heavy dental abrasion (Mahoney, 2007). The circular process of exploiting new or different resources required techniques and technology to extract nutrients, and in turn, the new methods provided access to new food sources (Boone, 2002): Between the 7th and the 5th millennia, for example, milk was being consumed by farmers in southeastern Europe, Anatolia, and the Levant. The evidence comes from comparing the residue left on pottery sherds—that of fat from fatty acid from milk to carcass fats (Evershed et al., 2008).

In his discussions of the San, Richard Lee (1979) noted that the cultural practice of reciprocal food sharing, as complex as it was, functioned as storage in a climate where there was no other means: As perishable meat was given away, it ensured the giver a return portion some days later. Had the giver kept the entire kill, undoubtedly most of it would have spoiled. Stiner (2001) references Binford’s suggestion that the development of storage systems was one of the technological “inventions” that must have accompanied the broadening of the diet so that the new variety of seeds and grain could be kept for some days. While hunter-gatherers, even until the end of the old ways (until 1965), would gather grain heads as they walked from one camping site to another— an observation documented in the Australian government’s films on the Arunta—the development of implements to break open the grain heads, removing the chaff and pulverizing the germ, perhaps preceded domestication. As grains and grasses became more important in the diet, the gathering of those that failed to explode and release their seed grain became the staple domesticates. The advent of domestication has been dated at the various areas illustrated in Table 2.

Early domestication developed in different ways in different areas, as local people responded to local exigencies in different conditions and with different cultural standards (Evershed et al., 2008). Gathering and colonization were how plants and animals came to be domesticated, with some evidence that people practiced cultivation in naturally growing areas of desirable plants. By removing competitors, distributing water, or protecting from predators, the people were able to enhance the growth of the desired plant. Because plants were gathered and brought back to home base, some seeds took root nearby. Awareness of the relationship of these seeds to the burgeoning plant spurred the next stage. Those plants that were gathered often had less efficient dispersal mechanisms. Their seed heads did not break off, and their seeds did not blow away. This was the case for flax, peas, beans, and many others, facilitating their cultivation. It seems a natural progression to the next step, outright sowing.

Gathering of seeds, and keeping them for the next season, was the final and significant step in the process of domestication, but it requires surplus as well as foresight and storage facilities. The seeds that would become the next season’s crop were selected for some attribute they possessed: The plant had produced more, the seeds were less volatile, less able to disperse, or predators had been kept from taking them. Forms of plants that were more suitable were selected, probably initially unconsciously, and later intentionally—skewing the genetic mix in favor of domestication.

The supposition about animal domestication includes various ideas: Perhaps the cubs of hunted mothers were brought home and raised; some kinds of animals “followed” people home where making a living was easier; animals were kept in corrals or tethered to allow captive ones to mate with the wild until the population grew substantially so that taking them was easier; or animals showing traits such as aggression not favorable to people were eliminated from the gene pool. The “big five” of domesticated animals—pigs, cows, sheep, chickens, and goats—were domesticated in different regions, independently from one another (Diamond, 2002), whereas domestication of plants seems to have diffused through areas. The animals that became domesticated were those that had behavioral traits that permitted it: They were gregarious and lived in herds where following the leader was part of the repertoire. Diamond (2002) suggests that it is the geographic range in which domesticates were found that influenced whether there were single or multiple areas of origin. The range of the big five is so great in each case that they were independently domesticated throughout, whereas the plants had a more limited range and so both domesticates and process diffused.

A population boom is clearly recorded at the centers of domestication (e.g., the city of Jericho in the Near East had up to 3,000 people living in it by 8500 BCE, according to the original researcher, Kathleen Kenyon, although that number has been revised downward [as cited in Bar-Yosef, 1986]). In these centers, there were an impressive number of people supporting themselves on a variety of domesticated plants such as einkorn, emmer wheat, and barley. The city of Teotihuacan in what is now Mexico had a population of 200,000 just before the Spaniards arrived (Hendon & Joyce, 2003). The abundance of food has its repercussions in population size with a concomitant development of trade specializations.

Over time, however, the benefits of agriculture become somewhat overshadowed. Zoonoses from association with farm animals increased. Tapeworms were known from 1.7 mya along with hookworm and forms of dysentery. Because settlements were often near bodies of still water such as marshes or streams, malaria became endemic. The development of agriculture and its concomitant population increase encouraged a variety of contagious diseases in the human population. In addition, noninfectious diseases became increasingly apparent: arthritis; repetitive strain injury; caries; osteoporosis; rickets; bacterial infections; birthing problems; and crowded teeth, anemia, and other forms of nutritional stress, especially in weanlings who were weaned from mother’s milk to grain mush. Caries and periodontal disease accompanied softer food and increased dependence on carbohydrates (Swedlund & Armelagos, 1990). Lung diseases caused by association with campfires, often maintained within a dwelling without proper ventilation, plagued humanity as well (Huttner, Beyer, & Bargon, 2007). Warfare also makes its appearance as state societies fight over irrigation, territory, and resources, and have and have-not groups vie for their privileges (Gat, 2006). Hunter-gatherers were generally not only healthier, but taller. The decrease in height is probably a result of less calcium or vitamin D, and insufficient essential amino acids, because meat became more prized and was only distributed to the wealthy. Women suffered differentially, as males typically received the best cuts and more, especially when meat was not abundant (Cohen & Armelagos, 1984).

The more mouths to feed, the greater the incentive to develop farming techniques to increase supporting output. Implements changed, human labor gave way to animal labor, metal replaced wood, carts and their wheels became more sophisticated, but above all, selection of seed and breed animals became more trait specific as knowledge grew. The associated decrement in variety began early and has continued to the present.

The changes that have taken place in the use of plants and animals are momentous. The idea of change promoted the advances that mark the 18th century. As has too often been the case, warfare encouraged new technology. Napoleon’s dictum that armies run on their stomachs inspired competition to find a way to preserve food for his campaigns. Metal, rather than glass, was soon introduced to preserve food in a vacuum (Graham, 1981). It did not always work: Botulism and lead poisoning from solder used to seal the tin played havoc with health. (Currently, the bisphenol in the solder is also a concern.) Nevertheless, the technique was not abandoned, especially as it meant that food could be eaten out of season. “Exotic” foods from elsewhere could now be introduced from one country to another. The ingredients of Italian spaghetti are an obvious case in point: noodles from China, tomatoes from Mesoamerica, and beef originally from the Fertile Crescent combined in one place at different dates. For very different historical reasons, the Conquistadors brought much of it back to Europe after Columbus’s momentous voyage. Diffusion of crops and techniques had occurred since they were first developed, evident in the “Muslim agricultural revolution” at the height of Islam from 700 CE to the 12th century (DeYoung, 1984; Kaba, 1984; Watson, 1983). During this period, China received soybeans, which arrived in c. 1000 CE, and peanut oil—both staples in the modern Chinese diet. Millet had been more important in China than rice (just as in contemporary west Africa, corn is replacing the more proteinaceous millet), and tea was a novelty until the Tang dynasty.

In “the present,” the kind of foodstuffs that could be dispersed elaborated the inventory. The Industrial Revolution, with its harnessing of fossil fuel (coal) to produce energy (steam), further encouraged the process as travel time diminished. Food could be eaten—fresh—out of season and brought from thousands of miles away. The refrigerator truck could take food from its source, usually unripe, and deliver it thousands of miles away. With this new mechanism, the food value in the produce is diminished, but the extravagance of eating produce out of season remains.

Rivaling the distribution of foodstuffs in its impact on human history is the continued control of breeding. Indeed, Darwin’s great work proposed “natural” selection in contrast to husbandry, or “artificial” selection. Before the gene was known and named—properly a 20th-century achievement— “inheritance” in humans was sufficiently understood in the form of eugenics (with its dubious history) as put forth by Galton in the late 1880s. When Mendel’s findings were recovered in 1900, Bateson named the gene (1905–1906), and Morgan discovered the chromosome (1910), genetics got seriously under way, and culminated, in the context of this research paper, in the Green Revolution.

By the 1960s, famine had become a major world issue, with increasing frequency and severity: the Bengal famine of 1942 to 1945; the famine in China between 1958 and 1961, which killed 30 million people; and the famines in Africa, especially Ethiopia and the west African Sahel in the early 1970s (Sen, 1981) rivaled the famines recorded in ancient history and throughout modern history, especially in the late 19th century. Although the causes of famine are usually environmental, for example drought or pests, the underlying causes are often economic and political (Sen, 1981). In the United States, the President’s Science Advisory Committee (1967) issued a report noting that the problem of famine, worldwide, was severe, and could be predicted to continue unless and until an unprecedented effort to bring about new policies was inaugurated (Hazell, n.d.).

In an attempt to bypass the underlying issues by producing more food for starving millions, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations initiated what was named the Green Revolution. This was a dramatic change in farming techniques introduced to have-not countries of the time: India, China, and nations throughout Asia and Central America.

Mexico had initiated this decades earlier, in the early 1940s, when Norman Borlaug (1997) developed highyielding, dwarf varieties of plants. Production increased exponentially, and seed and technology from the “experiment” in Mexico was soon exported to India and Pakistan. At the occasion of his Nobel Prize being awarded in 1970, Borlaug noted that wheat production had risen substantially in India and Pakistan: From 1964 to 1965, a record harvest of 4.6 million tons of wheat was produced in Pakistan. The harvest increased to 6.7 million tons in 1968, by which time West Pakistan had become self-sufficient. Similarly, India became self-sufficient by the late 1960s, producing record harvests of 12.3 million tons, which increased to 20 million tons in the 1970s (Borlaug, 1997).

To sustain these harvests, however, petrochemicals had to be employed, and land had to be acquired. The new genetic seeds were bred for traits requiring fertilizers, pesticides, and water. Since the mid-1990s, the enthusiasm for the Green Revolution has waned as the numbers of the hungry have increased worldwide, and production has decreased. According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) (2008), the global rice yields have risen by less than 1% per year in the past several decades.

The explanations for the decrease vary, but among the most important is the fact that soil degradation results from intensity of farming, and petrochemicals that do not “feed” the soil itself. Depletion in soil nutrients requires stronger fertilizers; pesticides select for resistant pests and diseases, which in turn require stronger pesticides. Poorly trained farmers overuse the petrochemicals, exacerbating the situation. Irrigation itself causes a serious problem: The evaporation of water leaves a salt residue that accumulates in the soil. There is a concomitant loss of fertility estimated as 25 million acres per year, that is, nearly 40% of irrigated land worldwide (Rauch, 2003). In addition, new genetic breeds have not addressed social factors: Water supplies are regional, and irrigation requires financial resources; and farmers with greater income buy up smaller holdings and can afford to purchase industrial equipment. Access to food was not enhanced by the Green Revolution, especially in Africa (Dyson, 1999), where imports are approximately one third of the world’s rice (IRRI, 2008). It is access to food, more than abundance or pest resistance, that mitigates famine, dramatically demonstrated by Sen (1981). Determining access falls into the hands of government— implementing social security programs, maintaining political stability, and legislating property rights. The small farmers then move to cities, which become overcrowded, and lack employment.

While access has improved in some areas, the increase in population—often occurring exponentially—requires yet greater production. The response has been what, at the end of the 1990s, some have termed frankenfood (Thelwall & Price, 2006), or genetically engineered seed. This combines traits from very different species to enhance the plant. Thus, cold-water genes from fish are put into wheat to enable it to grow in regions not hospitable to the plant, or plants are engineered to resist a herbicide that would otherwise kill it as it destroys competitors. Transgenic genes might allow insemination for a variety of plants into soil that has become infertile due to salinization, and thereby extend productivity to regions where production has long ago ceased (Rauch, 2003).

Genetically modified (GM) plants are spreading throughout the world, even as some countries refuse them entry. The powerful corporations and governments that endorse their use see them as a panacea: New varieties for new climate issues, which themselves, like global warming, have arisen as a result of human activity, not the least of which is the industrialization of food. In addition, farmers are restricted from using seed from engineered plants, even if they blow into their fields, as the seeds are, in effect, copyrighted and the use of them has caused expensive legal challenges (“In Depth,” 2004). While GM crops are less damaging to the environment than typical introduced species, as the numbers and distribution of these increase, the probabilities of them spreading, evolving, and mixing with local varieties increases (Peterson et al., 2000). Early “evidence” at the beginning of the century that transgenes had entered the genomes of local plants in Oaxaca, Mexico, was based on two distinctive gene markers. The studies were corroborated by government agencies but further controlled, and a peer-reviewed study of a huge sample of farms and corn plants did not find transgenes in this region (Ortiz-García et al., 2005). The question therefore remains moot, at least in Mexico, but the issue gave rise to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (1999–2000), which regulates the movement of living modified organisms—plant and animal—whether for direct release or for food (Clapp, 2006). A number of countries in Europe and Africa have refused modified seed, although pressure on them to accept the seed continues. The Food and Agriculture Association’s (FAO) Swaminathan (2003) has urged India not to permit a “genetic divide” to exclude it from equality with other developing nations. Anxious that there not be a genetic divide between those countries that pursue transgenic organisms and those that do not, the United Nations World Health Organization (WHO) has echoed this concern (WHO/EURO, 2000).

Over time, selection for certain desired traits and hybridization of stock to develop specific traits (resistance to disease, etc.) has meant the loss of biodiversity in agriculture. Conservation of seed, by agencies like the Global Crop Diversity Trust, and seed banks, like IRRI in the Philippines, and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, have been established in order to retain plant biodiversity. Their purpose is to have available strains that can reinvigorate domesticated species with genes from the “wild type.” Because domestication reduces variation, these “banks” become increasingly important (AcostaGallegos, Kelly, & Gepts, 2007).

Certainly there will be more technological advances as the pressure for food continues and the area available for cultivation diminishes. The growth of genetic modification over the past decade has been exponential and is a harbinger of the future. The food crisis in the mid-1970s caused by oil prices, and the world summit on finding solutions, both had little permanent effect. The food crisis in the first decade of the 21st century has multiple causes, not the least of which is climate change. But that is not the cause: It is a concomitant, as Sen (1981) has argued. Newspapers and magazines detail the economic and political actions that seem paramount, and then a climate disaster hits and the crisis becomes full-blown. Australia, for example, has been suffering drought for over a decade, especially in its wheat-growing areas, but its economy can support basic food imports; Canada’s prairies were overwhelmed by a heat wave due to climate change, which reduced its 5-year production of wheat by over 3 million tons. Ironically, one of the major factors is that due to the Green Revolution, the health and diet of billions of people, in China and India in particular, has improved, but this has led to obesity (Popkin, 2008). Their demand for meat, which traditionally was an ingredient in a vegetable-based gravy over a staple, has escalated, and with it a shift from land producing for people to land producing for, especially, cattle. And, world over, the amount of arable land left has decreased from 0.42 hectares per person in 1961 to just about half this figure by the beginning of this century (as cited in Swaminathan, 2003).

Over the past two decades, the rise in the price of oil has caused an escalation of food prices, since transportation by ship, plane, or truck requires energy and global food markets require foodstuffs that once were kept local. Clearly another form of energy needed to be found, and the answer lay in the conversion of biomass to energy. The demand for biofuel, initially created from corn, kept acres out of food production and relegated them to energy manufacture. Currently the move is to find other sources of biomass— like algae, for example—to relieve the pressure on foodstuffs, and ultimately to use waste to create fuel. Then too, agglomeration of land into huge holdings has helped to make farming a business enterprise, subsidized by government and reflected in the market fluctuations in the prices of commodities, where 60% of the wheat trade, for example, is controlled by large investment corporations. The consequence has been that small farmers cannot compete with imports that are cheaper than what they can produce; production cannot compete with demand (IRRI, 2008). An even further result is scarcity in precisely those countries where the crops are grown, resulting in hoarding not only by individuals, but also by governments, for example, the ban on rice in India and Vietnam (IRRI, 2008).

Global organizations such as the G8 and the World Trade Organization (WTO), together with nongovernmental agencies, individual governments, think tanks, and institutes, are “closing the barn door after the horse has escaped” with a variety of stop-gap measures. At the same time, there are clear and significant countertrends occurring. Not the least of these, and perhaps the best established, is the organic movement, whose origins followed the introduction of vast petrochemical use in the 1940s. Since then, the movement has grown out of the “fringe” to become “established.” In the mid-1980s, supermarkets’ recognition of a substantial market for certified-organic produce and meat broadcast the knowledge of the health implications of additives (from MSG to nitrites).

Of course, advances in technology and science focus on ensuring that there will be sufficient food for future populations. Livestock require vast amounts of land to produce the food they eat. By the early 1970s, the calculation was that conversion of cow feed to meat produced amounts to only 15% (Whittaker, 1972), and cows eat prodigious amounts of food. The agriculture department of Colorado State University, for example, reckons a cow eats up to 25 pounds of grain, 30 pounds of hay, and 40 to 60 pounds of silage— per day. One way around this is the virtual “creation” of meat. The future will see the industrial manufacture of meat through tissue engineering (Edelman et al., 2005). Using principles currently devised for medical purposes, cultured meat may actually reduce environmental degradation (less livestock, less soil pollution) and ensure human health through control of kinds and amounts of fat, as well as bacteria. Given the growth of the world’s population, in order to maintain health levels, the current trend of creating, nurturing, and breeding neutraceuticals will be expanded. The Consultative Group on Agriculture Research’s (CGIAR) Harvest Plus Challenge Program is breeding vitamin and mineral dense staples: wheat, rice, maize, and cassava for the developing world (HarvestPlus, 2009). Similarly, the inclusion of zinc, iron, and vitamin A into plant foods is under way in breeding and GM projects. The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) terms its efforts Agrosalud as it seeks to increase the food value of beans, especially with regard to iron and calcium content (AcostaGallegos et al., 2007).

There is a distinct interest in returning to victory gardens —those small, even tiny plots of land in urban environments that produced huge quantities of food in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada during World War II. By 1943, there were 20 million gardens using every available space: roofs of apartment buildings, vacant lots, and of course backyards. Together they produced 8 million tons of food (Levenstein, 2003). The beginnings of this movement are seen in the community gardens hosted in many cities, and in blogs and Web sites all over the Internet. Cities will also see the development of vertical farms —towering buildings growing all sorts of produce and even livestock. This idea, first promulgated by Dickson Despommier, a professor of microbiology at Columbia University, has quickly found adherents (Venkataraman, 2008). One project, proposed for completion by 2010, is a 30-story building in Las Vegas that will use hydroponic technology to grow a variety of produce. The idea of small plots, some buildings, and some arable land—in effect, a distribution of spaces to grow in—is consonant with the return to “small” and local: the hallmarks of the slow movement.

The future may see a return to local produce grown by small farmers, independent of the industrialized superfarms, utilizing nonhybridized crops from which seed can be stored. The small and local is part of the slow movement, which originated in Italy in the mid-1980s as a protest against fast food and what is associated with it. Its credo is to preserve a local ecoregion: its seeds, animals, and food plants, and thereby its cuisine (Petrini, 2003). It has grown into hundreds of chapters worldwide with a membership approaching 100,000 and has achieved this in only two decades. In concert with this movement is a new respect for, and cultivation of, traditional knowledge. The World Bank, for example, hosts a Web site on indigenous knowledge (Indigenous Knowledge Program, 2009) providing information ranging from traditional medicine, to farming techniques (e.g., composting, terracing, irrigating), to information technology and rural development.

The best example of small, local, and slow, along with exemplary restoration of indigenous knowledge, comes from Cuba. When the United States closed its doors to Cuba in the late 1950s, the Soviet Union became the chief supporter of Cuba, providing trade, material, and financial support. With the fall of communism, and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, Cuba could no longer rely on the imports of petrochemicals that had been traded for citrus and sugar and upon which agribusiness depended. Large-scale state farms therefore were broken into local cooperatives; industrial employees were encouraged to work on farms, or to produce gardens in the cities much like victory gardens. A change in the economic system, permitting small-scale farmers to sell their surplus, encouraged market gardening and financial independence. Oxen replaced tractors, and new “old” techniques of interplanting, crop rotation, and composting replaced petrochemicals. Universities found practitioners and taught traditional medicine and farming techniques. It may not be feasible for small and local to exist everywhere, yet the future will see some of each as expedience requires.

Bibliography:

- Ackermann, R. R., & Cheverud, J. M. (2004). Detecting genetic drift versus selection in human evolution. PNAS, 101 (52), 17946–17951.

- Acosta-Gallegos, J.A., Kelly, J. D., & Gepts, P. (2007). Prebreeding in common bean and use of genetic diversity from wild germplasm. Crop Science, 47 (Suppl. 3), S44–S59.

- Alroy, J. (2001). A multispecies overkill simulation of the endPleistocene megafaunal mass extinction. Science, 292 (5523), 1893–1896.

- Bar-Yosef, O. (1986). The walls of Jericho: An alternative interpretation. Current Anthropology, 27 (2), 157–162.

- Bar-Yosef, O. (1998). The Natufian culture in the Levant: Threshold to the origins of agriculture. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6 (5), 59–177.

- Boone, J. L. (2002). Subsistence strategies and early human population history: An evolutionary ecological perspective. World Archaeology, 34 (1), 6–25.

- Borlaug, N. (1997). The Green Revolution: Peace and humanity [A speech on the occasion of the awarding of the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway, on December 11, 1970]. The Atlantic Online, Available at http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/97jan/borlaug/speech.htm

- Brockman, D. K. (2005). What do studies of seasonality in primates tell us about human evolution? In D. K. Brockman & C. van Schaik (Eds.), Seasonality in primates: Studies of living and extinct human and non-human primates (pp. 544–570). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Brook, B. W., & Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2002). Explaining the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions: Models, chronologies, and assumption. PNAS, 99 (23), 14624–14627.

- Burton, F. D. (1972). The integration of biology and behavior in the socialization of Macaca sylvana of Gibraltar. In F. Poirier (Ed.), Primate behavior (pp. 29–62). New York: Random House.

- Burton, F. D. (2009). Fire: The spark that ignited human evolution . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Clapp, J. (2006). Unplanned exposure to genetically modified organisms: Divergent responses in the global south. The Journal of Environment Development, 15 (1), 3–21.

- Cohen, M. N., & Armelagos, G. J. (1984). Paleopathology at the origins of agriculture. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Cummings, D. E., Foster-Schubert, K. E., & Overduin, J. (2005). Ghrelin and energy balance: Focus on current controversies. Current Drug Targets, 6 (2), 153–169.

- DeYoung, G. (1984). Review: Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world:The diffusion of crops and farming techniques, 700–1100, by Andrew M. Watson. Isis, 75 (4), 758–759.

- Diamond, J. (2002). Evolution, consequences and future of plant and animal domestication. Nature, 418 , 700–707.

- Dyson, T. (1999). World food trends and prospects to 2025. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 96 (11), 5929–5936.

- Edelman, P. D., McFarland, D. C., Mironov,V.A., & Matheny, J. G. (2005). In-vitro cultured meat production. Tissue Engineering, 11 (5–6), 659–662.

- Engel, C. (2002). Wild health. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Evershed, R. P., Payne, S., Sherratt,A. G., Copley, M. S., Coolidge, J., Urem-Kotsu, D., et al. (2008). Earliest date for milk use in the Near East and southeastern Europe linked to cattle herding. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07180

- Firestone, R. B. F., West,A., Kennett, J. P., Becker, L., Bunch,T. E., Revay, Z. S., et al. (2007). Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. PNAS, 104 (41), 16016–16021.

- Fountain, E. D., Mao, J., Whyte, J. J., Mueller, K. E., Ellersieck, M. R., Will, M. J., et al. (2007). Effects of diets enriched in omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids on offspring sex-ratio and maternal behavior in mice. Biology of Reproduction, 78 (2), 211–217.

- Gat, A. (2006). War in human civilization. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Goodall, J. (1986). The chimpanzee of Gombe: Patterns of behaviour. Boston: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Graham, J. C. (1981). The French connection in the early history of canning. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 74, 374–381.

- Green, M. P., Spate, L. D., Parks,T. E., Kimura, K., Murphy, C. N., Williams, J. E., et al. (2008). Nutritional skewing of conceptus sex in sheep: Effects of a maternal diet enriched in rumen-protected polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 6 (21).

- Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2005). Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends in cognitive sciences, 9 (9), 439–444.

- (2009). Breeding crops for better nutrition. Available at http://www.harvestplus.org/

- Hazell, P. B. R. (n.d.). Green revolution: Sustainable options for ending hunger and poverty. Curse or blessing? Available at http://www.ifpri.org/pubs/ib/ib11.pdf

- Hendon, J. A., & Joyce, R. A. (Eds.). (2003). Mesoamerican archaeology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Hernandez-Aguilar, R. A., Moore, J., & Pickering, T. R. (2007). Savanna chimpanzees use tools to harvest the underground storage organs of plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (49), 19210–19213

- Hoberg, E. P., Alkire, N. L., de Queiroz, A., & Jones, A. (2001). Out of Africa: Origins of the Taenia tapeworms in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Biological Sciences, 268, 781–787.

- Huffman, M. A. (1997). Current evidence for self-medication in primates: A multidisciplinary perspective. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 40, 171–200.

- Huttner, H., Beyer, M., & Bargon, J. (2007). Charcoal smoke causes bronchial anthracosis and COPD. Med Klin (Munich), 102 (1), 59–63.

- In depth: Genetic modification. (2004). Genetically modified foods: A primer . CBC News Online. May 11, 2004. Available at http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/genetics_modification/

- Indigenous Knowledge Program. (2009). Indigenous knowledge for development results. Available at http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/AFRICAEXT/EXTINDKNOWLEDGE/0,,menuPK:825562~pagePK: 64168427~piPK:64168435~theSitePK:825547,00.html

- International Rice Research Institute. (2008). The rice crisis: What needs to be done? Available at www.irri.org

- Kaba, L. (1984). Review: Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world: The diffusion of crops and farming techniques, 700–1100, byAndrew M. Watson. African Economic History, 13, 227–230.

- Kay, R. F. (2005). The functional adaptations of primate molar teeth. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 43 (2), 195–215.

- Kislev, M. E., Nadel, D., & Carmic, I. (1992). Epipalaeolithic (19,000 BP) cereal and fruit diet at Ohalo II, Sea of Galilee, Israel. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 73 (1–4), 161–166.

- Knott, C. D. (2005). Energetic responses to food availability in the great apes: Implications for hominin evolution. In D. K. Brockman & C. Van Schaik (Eds.), Seasonality in primates: Studies of living and extinct human and non-human primates (pp. 351–378). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kummer, H. (1971). Primate societies: Group techniques of ecological adaptation . Chicago: Aldine-Atheron.

- Lee, R. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, women, and work, in a foraging society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Leonard, W. R. (2002). Food for thought: Dietary change was a driving force in human evolution. Scientific American, 28 (6), 106–116.

- Leonard, W. R., & Robertson, M. L. (1992). Nutritional requirements and human evolution: A bioenergetics model. American Journal of Human Biology, 4 (2), 179–195.

- Leonard, W. R., & Robertson, M. L. (1994). Evolutionary perspectives on human nutrition: The influence of brain and body size on diet and metabolism. American Journal of Human Biology, 6 (1), 77–88.

- Levenstein, H. A. (2003). Paradox of plenty: A social history of eating in modern America (Rev. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mahoney, P. (2007). Human dental microwear from Ohalo II (22,500–23,500 cal BP), southern Levant. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 132 (4), 489–500.

- Milton, K. (1993). Diet and primate evolution. Scientific American, 269 (2), 86–93.

- Nadel, D. (2003). The Ohalo II brush huts and the dwelling structures of the Natufian and PPNA sites in the Jordan valley. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, 1 (13), 34–48.

- Ortiz-García, S., Excurra, E., Shoel, B., Acevedo, F., Soberón, J., & Snow, A. A. (2005). Absence of detectable transgenes in local landraces of maize in Oaxaca, Mexico (2003–2004). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102 (35), 12338–12343.

- Paabo, S. (2003). The mosaic that is our genome. Nature, 421, 409–412.

- Peterson, G., Cunningham, S., Deutsch, L., Erickson, J., Quinlan, A., Raez-Luna, E., et al. (2000). The risks and benefits of genetically modified crops: A multidisciplinary perspective. Conservation Ecology, 4 (1).

- Petrini, B. C. (2003). Slow food: The case for taste. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Platek, S. M., Gallup, G. G., Jr., & Fryer, B. D. (2002). The fireside hypothesis: Was there differential selection to tolerate air pollution during human evolution? Medical Hypotheses, 58 (1), 1–5.

- Popkin, B. M. (2008). Will China’s nutrition transition overwhelm its health care system and slow economic growth? Health Affairs, 27 (4), 1064–1076.

- Rauch, J. (2003). Will frankenfood save the planet? Over the next half century genetic engineering could feed humanity and solve a raft of environmental ills—if only environmentalists would let it. The Atlantic Monthly, 292 (3), 103–109.

- Rosenfeld, C. S., Grimm, K. M., Livingston, K.A., Brokman,A. M., Lamberson, W. E., & Roberts, R. M. (2003). Striking variation in the sex ratio of pups born to mice according to whether maternal diet is high in fat or carbohydrate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100 (8), 4628–4632.

- Rothman, J. M., Van Soest, P. J., & Pell, A. N. (2006). Decaying wood is a sodium source for mountain gorillas. Biology Letters, 2 (3), 321–324.

- Sen, A. K. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. NewYork: Oxford University Press.

- Sokolov, R. (1991). Why we eat what we eat: How Columbus changed the way the world eats . New York: Touchstone.

- Stiner, M. C. (2001). Thirty years on the “Broad Spectrum Revolution” and Paleolithic demography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98 (13), 6993–6996.

- Surovell, T., Waguespack, N., & Brantingham, P. J. (2005). Global archaeological evidence for proboscidean overkill. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102 (17), 6231–6236.

- Sutton, M. Q., & Anderson, E. M. (2004). Introduction to cultural ecology. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Swaminathan, M. S. (2003). The Chennai declaration: Bridging the genetic divide. Current Science, 84 (4), 494–495.

- Swedlund, A., & Armelagos, G. J. (1990). Disease in populations in transition. New York: Bergin & Garvey.

- Thelwall, M., & Price, L. (2006). Language evolution and the spread of ideas on the Web: A procedure for identifying emergent hybrid word family members. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57 (10), 1326–1337.

- S. Census Bureau. (2009). International data base. Available at http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/

- Venkataraman, B. (2008, July 15). Country, the city version: Farms in the sky gain. New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/15/science/15farm.html

- Wakayama, E. J., Dillwith, J. W., Howard, R. W., & Blomquist, G. J. (1984). Vitamin B 12 levels in selected insects. Insect Biochemistry, 14 (2), 175–179.

- Watson,A. M. (1983). Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world: The diffusion of crops and farming techniques, 700– 1100 . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Weiss, E., Wetterstrom, W., Nadel, D., & Bar-Yosef, O. (2004). The broad spectrum revisited: Evidence from plant remains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101 (26), 9551–9555

- Whittaker, J. (1972). The next 50 years in meat science research. Journal of Animal Science, 34, 957–959.

- Wobber, V., Hare, B., & Wrangham, R. (2008). Great apes prefer cooked food. Journal of Human Evolution, 55, 340–348.

- World Health Organization/European Centre for Environment and Health. (2000, September 7–9). Report of a Joint WHO/EURO-ANPA Seminar World Health Organization: Release of genetically modified organisms in the environment: Is it a health hazard? Available at http://www.euro .who.int/document/fos/fin_rep.pdf

- Wrangham, R., & Conklin-Brittain, N. L. (2003). Review: Cooking as a biological trait. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, 136, 35–46.

- Wrangham, R. W. (2001). Out of the pan, into the fire: How our ancestors’ evolution depended on what they ate. In F. B. M. de Waal (Ed.), Tree of origin: What primate behavior can tell us about human social evolution (pp. 119–143). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wrangham, R. W., McGrew, C. W., de Waal, F. B. M., & Heltne, P. (Eds.). (1994). Chimpanzee cultures. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Zeuner, F. (1963). A history of domesticated animals. London: Hutchinson.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

120 Food Research Paper Topics

How to choose a topic for food research paper:, fast food research paper topics:.

- The impact of fast food consumption on obesity rates in children

- The influence of fast food advertising on consumer behavior

- The correlation between fast food consumption and cardiovascular diseases

- The role of fast food in the development of type 2 diabetes

- The effects of fast food on mental health and well-being

- The environmental impact of fast food packaging and waste

- Fast food and its contribution to food deserts in urban areas

- The economic implications of the fast food industry on local communities

- Fast food and its association with food addiction and cravings

- The nutritional value and quality of ingredients used in fast food

- The influence of fast food on dietary patterns and nutritional deficiencies

- The role of fast food in the globalization of food culture

- The ethical concerns surrounding fast food production and animal welfare

- The impact of fast food consumption on academic performance in students

- Fast food and its relationship to food insecurity and poverty

Food Insecurity Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of food insecurity on child development

- Food insecurity and its relationship to mental health

- Exploring the causes of food insecurity in urban areas

- The role of food banks in addressing food insecurity

- Food insecurity among college students: prevalence and consequences

- The effects of food insecurity on maternal and infant health

- Food insecurity and its implications for rural communities

- The relationship between food insecurity and obesity

- Food insecurity and its impact on academic performance in children

- The role of government policies in addressing food insecurity

- Food insecurity and its connection to chronic diseases

- The effects of food insecurity on older adults’ health and well-being

- Food insecurity and its influence on food choices and dietary quality

- The role of community gardens in reducing food insecurity

- Food insecurity and its impact on social inequalities and disparities

Organic Food Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of organic farming on soil health and fertility

- The nutritional differences between organic and conventionally grown fruits and vegetables

- The effects of organic farming practices on water quality and conservation

- The potential health benefits of consuming organic dairy products

- The role of organic agriculture in reducing pesticide exposure and its associated health risks

- The economic viability and market trends of organic food production

- The impact of organic farming on biodiversity and ecosystem services

- Consumer perceptions and attitudes towards organic food: A global perspective

- The effectiveness of organic farming in mitigating climate change

- The role of organic farming in promoting sustainable food systems

- Organic versus conventional meat production: A comparison of animal welfare standards

- The impact of organic food consumption on human health and disease prevention

- The challenges and opportunities of organic food certification and labeling

- The role of organic farming in reducing food waste and promoting food security

- The potential environmental and health risks associated with genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in organic food production

Food Technology Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of food processing techniques on nutritional value

- The role of food technology in reducing food waste

- The development of sustainable packaging materials for food products

- The use of nanotechnology in food processing and preservation

- The application of artificial intelligence in food quality control

- The potential of 3D printing in personalized nutrition

- The impact of food technology on the sensory properties of food products

- The role of food technology in improving food safety and reducing foodborne illnesses

- The development of novel food ingredients using biotechnology

- The use of blockchain technology in ensuring traceability and transparency in the food supply chain

- The impact of food technology on the shelf life and stability of food products

- The role of food technology in addressing food allergies and intolerances

- The application of robotics in food processing and manufacturing

- The development of functional foods for specific health conditions

- The use of genetic engineering in enhancing crop productivity and nutritional content

Food Safety Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of foodborne illnesses on public health

- The role of government regulations in ensuring food safety

- Food safety practices in the restaurant industry

- The effectiveness of food safety training programs for food handlers

- Food safety risks associated with genetically modified organisms (GMOs)

- The role of food packaging in maintaining food safety

- Food safety concerns in the global food supply chain

- The impact of climate change on food safety and security

- Food safety risks associated with food delivery services

- The role of consumer behavior in ensuring food safety

- Food safety practices in home kitchens

- The impact of food additives and preservatives on food safety

- Food safety risks associated with food allergies and intolerances

- The role of technology in enhancing food safety measures

- Food safety challenges in developing countries

Food History Research Paper Topics:

- The Evolution of Food Preservation Techniques

- The Impact of the Columbian Exchange on Global Cuisine

- The Role of Food in Ancient Egyptian Society

- The Origins and Development of Chocolate as a Culinary Delight

- The Influence of French Cuisine on Modern Gastronomy

- The Cultural Significance of Spices in Medieval Europe

- The History of Food and Nutrition in World War II

- The Impact of Industrialization on Food Production and Consumption

- The Role of Food in Ancient Greek and Roman Rituals and Festivals

- The History of Street Food and its Socioeconomic Impact

- The Origins and Evolution of Sushi in Japanese Cuisine

- The Influence of Immigration on American Food Culture

- The History of Food and Medicine: From Ancient Remedies to Modern Nutraceuticals

- The Role of Food in Colonialism and Cultural Assimilation

- The Evolution of Fast Food and its Impact on Global Health

Food Marketing Research Paper Topics:

- The impact of social media on consumer behavior in the food industry

- The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements in food marketing campaigns

- The influence of packaging design on consumer perception and purchasing decisions

- The role of sensory marketing in food product development and promotion

- The effects of nutritional labeling on consumer choices and health outcomes

- The use of virtual reality and augmented reality in food marketing strategies

- The impact of food advertising on children’s food preferences and consumption patterns

- The role of cultural factors in shaping food marketing strategies and consumer behavior

- The effectiveness of personalized marketing approaches in the food industry

- The influence of food branding and brand loyalty on consumer purchasing behavior

- The role of sustainability and ethical considerations in food marketing practices

- The effects of food pricing strategies on consumer choices and market competition

- The impact of online food delivery platforms on consumer behavior and market dynamics

- The role of food labeling claims and certifications in consumer trust and decision-making

- The effects of food marketing on public health and policy implications

Food Chemistry Research Paper Topics:

- Analysis of food additives and their effects on human health

- Investigating the role of antioxidants in preventing food spoilage

- The chemistry behind flavor development in fermented foods

- Analyzing the chemical composition of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in food

- Understanding the chemical reactions involved in food browning and Maillard reaction

- Investigating the chemistry of food preservation methods, such as canning and freezing

- Analyzing the chemical changes in food during cooking and their impact on nutritional value

- The role of enzymes in food processing and their effects on food quality

- Investigating the chemistry of food allergies and intolerances

- Analyzing the chemical composition and health benefits of functional foods

- Understanding the chemistry of food packaging materials and their impact on food safety

- Investigating the chemical changes in food during storage and their effects on shelf life

- Analyzing the chemical composition and nutritional value of organic versus conventionally grown foods

- Investigating the chemistry of food contaminants, such as heavy metals and pesticides

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Forget about ChatGPT and get quality content right away.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2017

Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments

- Deborah R. Wahl 1 na1 ,

- Karoline Villinger 1 na1 ,

- Laura M. König ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3655-8842 1 ,

- Katrin Ziesemer 1 ,

- Harald T. Schupp 1 &

- Britta Renner 1

Scientific Reports volume 7 , Article number: 17069 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

131k Accesses

54 Citations

261 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health sciences

- Human behaviour

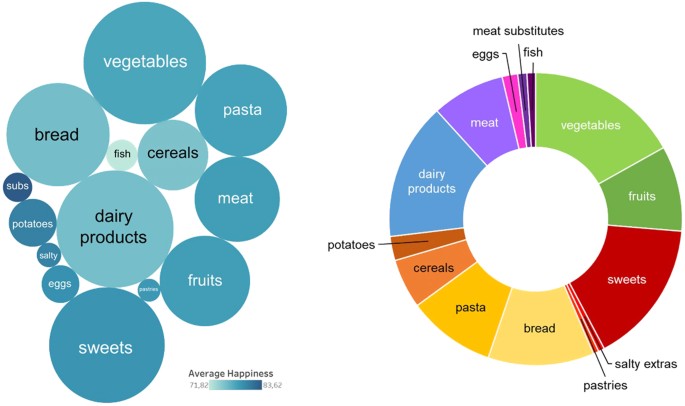

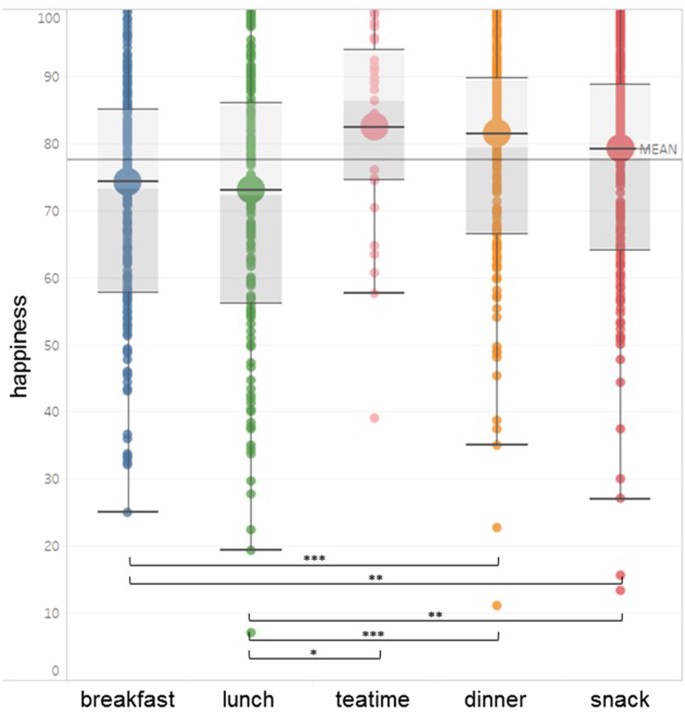

Research suggests that “healthy” food choices such as eating fruits and vegetables have not only physical but also mental health benefits and might be a long-term investment in future well-being. This view contrasts with the belief that high-caloric foods taste better, make us happy, and alleviate a negative mood. To provide a more comprehensive assessment of food choice and well-being, we investigated in-the-moment eating happiness by assessing complete, real life dietary behaviour across eight days using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment. Three main findings emerged: First, of 14 different main food categories, vegetables consumption contributed the largest share to eating happiness measured across eight days. Second, sweets on average provided comparable induced eating happiness to “healthy” food choices such as fruits or vegetables. Third, dinner elicited comparable eating happiness to snacking. These findings are discussed within the “food as health” and “food as well-being” perspectives on eating behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Federico Cavanna, Stephanie Muller, … Enzo Tagliazucchi

A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions

Julian Packheiser, Helena Hartmann, … Frédéric Michon

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

Introduction

When it comes to eating, researchers, the media, and policy makers mainly focus on negative aspects of eating behaviour, like restricting certain foods, counting calories, and dieting. Likewise, health intervention efforts, including primary prevention campaigns, typically encourage consumers to trade off the expected enjoyment of hedonic and comfort foods against health benefits 1 . However, research has shown that diets and restrained eating are often counterproductive and may even enhance the risk of long-term weight gain and eating disorders 2 , 3 . A promising new perspective entails a shift from food as pure nourishment towards a more positive and well-being centred perspective of human eating behaviour 1 , 4 , 5 . In this context, Block et al . 4 have advocated a paradigm shift from “food as health” to “food as well-being” (p. 848).

Supporting this perspective of “food as well-being”, recent research suggests that “healthy” food choices, such as eating more fruits and vegetables, have not only physical but also mental health benefits 6 , 7 and might be a long-term investment in future well-being 8 . For example, in a nationally representative panel survey of over 12,000 adults from Australia, Mujcic and Oswald 8 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted increases in happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being over two years. Similarly, using lagged analyses, White and colleagues 9 showed that fruit and vegetable consumption predicted improvements in positive affect on the subsequent day but not vice versa. Also, cross-sectional evidence reported by Blanchflower et al . 10 shows that eating fruits and vegetables is positively associated with well-being after adjusting for demographic variables including age, sex, or race 11 . Of note, previous research includes a wide range of time lags between actual eating occasion and well-being assessment, ranging from 24 hours 9 , 12 to 14 days 6 , to 24 months 8 . Thus, the findings support the notion that fruit and vegetable consumption has beneficial effects on different indicators of well-being, such as happiness or general life satisfaction, across a broad range of time spans.

The contention that healthy food choices such as a higher fruit and vegetable consumption is associated with greater happiness and well-being clearly contrasts with the common belief that in particular high-fat, high-sugar, or high-caloric foods taste better and make us happy while we are eating them. When it comes to eating, people usually have a spontaneous “unhealthy = tasty” association 13 and assume that chocolate is a better mood booster than an apple. According to this in-the-moment well-being perspective, consumers have to trade off the expected enjoyment of eating against the health costs of eating unhealthy foods 1 , 4 .

A wealth of research shows that the experience of negative emotions and stress leads to increased consumption in a substantial number of individuals (“emotional eating”) of unhealthy food (“comfort food”) 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . However, this research stream focuses on emotional eating to “smooth” unpleasant experiences in response to stress or negative mood states, and the mood-boosting effect of eating is typically not assessed 18 . One of the few studies testing the effectiveness of comfort food in improving mood showed that the consumption of “unhealthy” comfort food had a mood boosting effect after a negative mood induction but not to a greater extent than non-comfort or neutral food 19 . Hence, even though people may believe that snacking on “unhealthy” foods like ice cream or chocolate provides greater pleasure and psychological benefits, the consumption of “unhealthy” foods might not actually be more psychologically beneficial than other foods.

However, both streams of research have either focused on a single food category (fruit and vegetable consumption), a single type of meal (snacking), or a single eating occasion (after negative/neutral mood induction). Accordingly, it is unknown whether the boosting effect of eating is specific to certain types of food choices and categories or whether eating has a more general boosting effect that is observable after the consumption of both “healthy” and “unhealthy” foods and across eating occasions. Accordingly, in the present study, we investigated the psychological benefits of eating that varied by food categories and meal types by assessing complete dietary behaviour across eight days in real life.