Filaa Learning Resourses

Your one stop destination to find notes, worksheets, assignments and more...

TELIKILAAS_GRADE 11_DHIVEHI_Olhunfiluvaidhey Liyun

- National Institute of Education

Telikilaas Grade 11 Dhivehi Radio Drama

Telikilaas - grade 9 - dhivehi - dhekolhah vaahakadhakka liyun.

- Ministry of Education

Telikilaas - Grade 12 - Dhivehi - funding proposal

Hurun, inun , othun, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_ habaru liyun, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_ biography, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_ mauloomaath report liun, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_ report liun, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_ vaahaka liun, telikilaas_grade 5 _ dhivehi_sity liun, telikilaas _ grade 1_ ރީކައުންޓު ލިޔުން2_ދިވެހި mp4, telikilaas - grade 12 - dhekolhah liyaa onigandu thayyaarukurun final, telikilaas_grade 8_dhivehi_ekkolhah vaahaka dhakkaa liyun, telikilaas_grade 8_dhivehi_lhemuge ethere fushuge sifathah, grade 8: dhekey goiy haaamakuraa liyun, telikilaas - grade 12 - dhivehi - dhekolhah liyaa onigandu thayyaarukurun, telikilaas _ grade 1_ ރީކައުންޓު ލިޔުން_ދިވެހި mp4, telikilaas - grade 8 - dhivehi - ޅެމުގެ ބޭރުފުށާއި ސިފަތައް.

އެތަން މިތަނުން ކިޔާލުމަށް

އާދޭސް ކުރާ ހިތްވޭ ރޮމުން (17)

އަނދިރިފަރާތް 25

ލޯ މެރޭ ހިނދު ހީވޭ ގާތުގާ ވާހެން (15)

ހާދަ ދޭ ހިތްވެޔޭ ލޯބިން -1

ހިތާ ފުރާނައިން… (62)

އަންނަންދެން ހުންނާނަން ލޯބިން 49

ޤުރުބާން ވުމީ މިހިތުގެ އުފާ 2 ވަނަ ބައި

ވީމޭ އިންތިޒާރުގައި 7 ވަނަ ބައި.

އެންމެ ފަހުގެ

ވައުދޭ ވެވޭ މީ … 37

އިންސާނެކީމޭ……(ޓެއިލަރ)

ނަން ކަލާގެ މިހިތުގެގައި ފެވިއްޖޭ…49

ނުލިބޭނެހޭ އަލުން އެހީ 8

ފިނި ހިތް 12

ލޯބިން ބަލާލީމާ 2

ތިޔަ ލޯތްބަށް އެދެވޭތީ… 9

ލޯބިން ބުނެލަން……(5)

ޙަޤީޤަތް ހޯދުމޭ 7

ފިނި ހިތް 11

އިންސާފް (ފަނަރަވަނަ ބައި)

Please enable javascript in your browser to visit this site..

މުވައްޒަފުންގެ ސިފަ

ފަހުގެ ޚަބަރު, ލިޔުންތެރީންގެ ދުވަހާ ގުޅުވައިގެން ބާއްވާ “ފެންޑާ މައުރަޒު 2024” ފަށައިފި.

އަދަބީ ބައެއް މުބާރާތްތަކުގައި ބައިވެރިވުމުގެ މުއްދަތު ޖުލައި 09ވާ އަންގާރަދުވަހު ހަމަވާނެ.

“ބަސް އުފެދުމާއި ނެތި ދިއުން : ބަހަވީ ނަޒަރަކުން” ޑރ. އަޝްރަފް ޢަބްދުއްރަޙީމް.

މިއަދު ފާހަގަކުރާ ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޝަހީދުންގެ ދުވަހުގެ ހެޔޮއެދުމާއި ތަހުނިޔާ ހުރިހާ ބޭފުޅުންނަށް އަރިސްކުރަމެވެ.

ބަސްތޫރައަކީ ދިވެހިބަހުގެ އެކެޑަމީން ބޭރު ބަސްބަހުގެ ލަފުޒުތަކަށް ކަނޑައަޅާ ދިވެހި ލަފުޒުތައް ހިމެނޭ ގޮތުން ތައްޔާރުކޮށް ނެރޭ ތޫރައަށްކިޔާ ނަމެވެ.

ސުމޭކު ހިދުމަތް

3014800 ,3028000

English Made Simple

[email protected]

- 25 February 2024

The Dhivehi Language

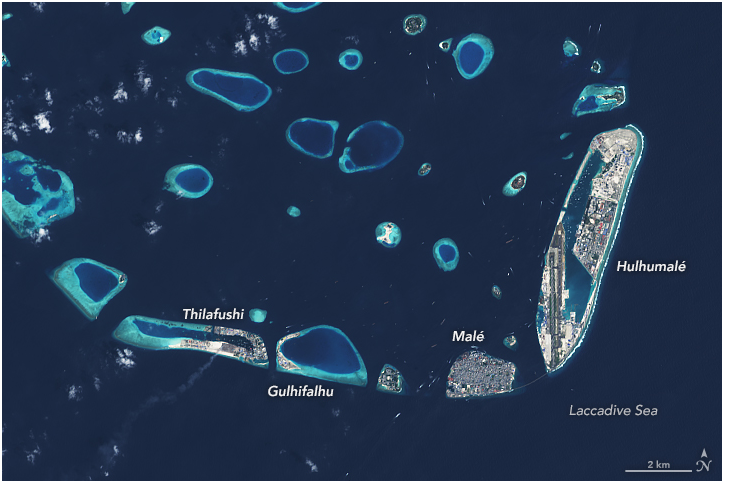

Dhivehi , also known as Maldivian, is the official language of the Maldives, an archipelago nation located in the Indian Ocean. It holds a unique position as the only language spoken in the Maldives and is an integral part of the nation’s cultural and historical identity.

Origins and History:

The Dhivehi language has a long and rich history that traces its roots to the Indo-Aryan languages. Linguists suggest that Dhivehi shares its ancestry with Sinhala, the language spoken in Sri Lanka. The influence of Sanskrit, Pali, and Arabic is evident in the language, reflecting the historical interactions and trade connections of the Maldives with neighbouring regions.

Historical records suggest that Dhivehi was written in a script known as Eveyla Akuru , a script derived from the ancient Brahmi script. However, over time, the script underwent transformations, and today, Dhivehi is written in a script called Thaana , which was introduced in the 16th century.

Development and Influences:

The development of the Dhivehi language has been shaped by its unique geographical and cultural context. Being isolated on a series of coral atolls, the Maldives maintained its distinct linguistic identity, although it absorbed influences from trade partners, such as Arabic and Persian.

During the medieval period, Islamic influences played a significant role in shaping the vocabulary of Dhivehi, as well as its literary and cultural expressions. The language adapted and evolved while maintaining its core structure.

Similarities and Differences with Related Languages:

Dhivehi shares linguistic and historical connections with Sinhala, and the two languages exhibit similarities in grammar and vocabulary. However, Dhivehi has also been influenced by Arabic due to the spread of Islam, setting it apart from Sinhala. The language has maintained its uniqueness over the centuries, despite its geographical proximity to other linguistic influences.

Dhivehi does not have significant regional dialectal variations. The language is spoken uniformly across the various atolls of the Maldives, maintaining a high degree of mutual intelligibility.

Number of Speakers and Geographic Distribution:

Dhivehi is spoken by approximately 500,000 people, predominantly in the Maldives. Due to the nature of the Maldives as an archipelagic nation, Dhivehi is the linguistic glue that binds the communities spread across the atolls.

Literary Works:

Dhivehi literature has a rich tradition, with influences from classical Islamic literature and local folklore. The earliest literary works in Dhivehi date back to the medieval period and are often associated with the spread of Islam in the region. Traditional storytelling, poetry, and oral narratives have been integral to the preservation of Dhivehi culture and language.

Syntax: Dhivehi follows a subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, which means that the subject comes first, followed by the object and then the verb. For example:

- Raajje gothun libey miadhu kihiney. (Translation: The boy ate the apple.)

Verbs and Verb Conjugations: Dhivehi verbs undergo conjugation based on tense, aspect, and mood. The verb stem remains constant, and affixes are added for conjugation. There are three verb conjugations: present, past, and imperative. For instance:

- Aisa kurun. (Translation: I eat.)

- Aisa kurin. (Translation: I ate.)

- Kuri! (Translation: Eat!)

Verb Tenses: Dhivehi recognizes three primary tenses: present, past, and future. Tense markers are added to the verb stem to indicate the timing of the action. Examples include:

- Aisa kurun. (Present – I eat.)

- Aisa kurin. (Past – I ate.)

- Aisa kuran. (Future – I will eat.)

Cases: Dhivehi employs a system of grammatical cases to indicate the syntactic and semantic roles of nouns within a sentence. Common cases include nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative. For example:

- Miadhu libun. (Nominative – The apple is red.)

- Miadhu libey. (Accusative – I see the apple.)

- Miadhu libaage. (Genitive – The color of the apple.)

- Miadhu libah. (Dative – Give the apple to me.)

Nouns and Articles: Dhivehi nouns do not have gender, but they can be singular or plural. Articles are not used in Dhivehi in the same way as in English. Instead, definiteness is often implied through context. For instance:

- Mas. (Fish – singular)

- Masun. (Fish – plural)

Adjectives: Adjectives in Dhivehi generally follow the noun they modify. Adjective forms do not change based on the gender or number of the noun. Example:

- Farudhee fai. (Big house.)

Negative and Interrogative Sentences: Negation in Dhivehi is typically expressed by adding the word “noon” before the verb. Interrogative sentences often begin with question words or particles. Examples include:

- Miadhu noon libun. (I don’t like apples.)

- Kihiney? (Did he/she eat?)

Example Sentences:

- Dhivehi boli aadhey. (We speak Dhivehi.)

- Raajje gothun libey miadhu kihiney. (The boy ate the apple.)

- Fahun huri. (The sky is blue.)

- Kuriah noon. (It’s not raining.)

In conclusion, the grammatical features of Dhivehi similar with that of other Indic languages including its nearest known relative Sinhala.

Here is a video related to the Maldivian language or Dhivehi.

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Dhivehi Articles

Dhi-English: Influence of Dhivehi language features on the English narratives of Maldivian ESL learners

- Zahra Mohamed

This qualitative descriptive study explored the influence of Dhivehi, the first language (L1) of the Maldivian students on learning English, their second language (L2). The questions raised in this paper enabled to identify morphological, lexical and syntactic transfer errors present in the narratives written by thirty-three students at secondary level from three schools in Male’, the capital of the Maldives. Transfer Analysis was used to analyze errors present in the English narratives written by Maldivian ESL (English as a Second Language) learners. The analysis uncovered negative transfer of Dhivehi linguistic features in their written English at morphological, lexical, as well as syntactic levels. The findings provide invaluable pedagogical implications for second language learning in the Maldivian context. Thus, it is recommended that ESL teachers as well as curriculum developers in the Maldives take into consideration the possibility of the influence of students’ mother tongue or Dhivehi linguistic features on the process of learning English.

- View/Dowload Article

Copyright (c) 2020 International Journal of Social Research & Innovation

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Make a Submission

ހަތަރު ހާސް އަހަރުވީ މިނިވަން ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ފަޚްރުވެރި ދިވެހި ޙަޟާރަތާއި އަސްލުތައް ދަސްކޮށް، އެ ކަންކަމުން އިލްހާމު ލިބިގެން، ދިވެހި ޤައުމަށް ހެޔޮއެދި، މުރާލި ހިންމަތްތެރިއަކަށްވުމުގެ ފުރުޞަތު، ދިވެހި ކޮންމެ ކިޔަވާ ކުއްޖަކަށް ލިބެން ޖެހޭނެ ރައީސުލްޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ ޑރ. މުޙައްމަދު މުޢިއްޒު

ށ އަތޮޅު ކައުންސިލުން އަތޮޅު ފެންވަރުގައި ޤައުމީ ދުވަސް ފާހަގަކުރަނީ

ވަޒީރު އާދަމް ނަޞީރު އިބްރާހީމް ގދ ވާދޫ ކައުންސިލާ ބައްދަލުކުރައްވައިފި., ސްރީ ލަންކާގެ ޤާނޫނު ހަދާ މަޖިލީހުގެ ރައީސް، އޮނަރަބަލް މަހިންދަ ޔަޕަ އަބޭވަރްދަނާދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޤައުމީ ދާރުލްއާސާރަށް ޒިޔާރަތް ކުރައްވައިފި., ސަގާފަތާއި ތަރިކައިގެ ރޮނގުން މީހުން ތަމްރީން ކުރުމާއި ފަންނީ އެހީތެރިކަން ފޯރުކޮށްދިނުމުގެ ޝައުޤުވެރިކަން ޖަޕާން އެމްބަސީން ފާޅުކޮށްފި., ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ފަޚުރުވެރި މިނިވަންދުވަހާ ގުޅިގެން ބޭއްވި ޝަރަފުގެ ހިނގާލުން ރައީސްގެ ދެކަނބަލުން ބައްލަވާލައްވައިފި..

ދިވެހީންގެ ޤައުމިއްޔަތު

ދިވެހީންގެ ދީން

ދިވެހީންގެ ޤައުމު

ދިވެހީންގެ ރާއްޖެ

ދިވެހީންގެ މިނިވަންކަން

ދިވެހީންގެ ބަސް

ދިވެހީންގެ ސަގާފަތް

ދިވެހީންގެ ދައުލަތް

ތަރިކަ ދަތުރު.

ދިވެހި ސަގާފީ ތަރިކަތައް ދާދިވަރުކޮށް ބައްލަވައިލެއްވުމަށް

ފުރިހަމަ ނަން

އީމެއިލް އެޑްރެސް

ފޮނުއްވަން ބޭނުންފުޅުވާ މެސެޖު

ދިވެހިބަހާއި ސަގާފަތާއި ތަރިކައާ ބެހޭ ވުޒާރާ

ޤައުމީ ދާރުލް އާސާރު

މާލެ، ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ

ފޯނު: +(960) 303 6999

އީމެއިލް: [email protected]

Introduction References Guide to Transliteration of Dhivehi Abbreviations The Persian and Hindi Alphabet --> [page I] INTRODUCTION Dhivehin ( ދިވެހިން ), Dhivehi Bas ( ދިވެހިބަސް ) and Dhivehi Raajje ( ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ ) , all three are so intricately bound together that we do not know which came first. Was it Dhivehin , the people of the Maldives? Was it Dhivehi Bas , the language of the Maldivians? Or was it the country Dhivehi Raajje , the country organised into a state? We can only surmise. But what we do know with certainty is the well harmonised fusion that exists among all these with the terrain on which Dhivehin live, speaking Dhivehi Bas and organised into the homogeneous state of Dhivehi Raajje. It is the island world of Maldives, now called the Republic of Maldives. We do not know when or where Dhivehi Bas was first spoken or much of its early evolultionary [sic] history. But we do know that today this language is spoken in the Republic of Maldives and in Maliku (Minicoy) where, by a twist of fortunes, it is called Mahal. Taking the geography of the Indian Ocean and the pioneering travels in this earliest known great ocean of the world, we do not hesitate to assign a very early date for the peopling of the Maldives. Even to say that it was several millennia ago may not be far off the mark. The late H. C. P. Bell in his monumental monograph on the Maldives (1940), quoting Albert Gray says: "As to its origin, the race which now inhabits the Maldivian archipelago (as well as Maliku , or Minicoy islands), and which has occupied it from the earliest times of which we have any record, is unquestionably of the same (Aryan) stock as the Sinhalese. This conclusion is borne out by evidence of language, physical traits, tradition, folklore, manners and customs." Every great empire that rose in the Indian Ocean and around it had its share of influence on the Maldives. Some of these influences are visible in different degrees on the cultural polity of the Maldives of today. Dhivehi language is the most notable of these. It belongs to the Indo-Aryan family of languages. Its closest sister is, undoubtedly Sinhala. The geography and the mere course of human interaction of this region makes [sic] this inevitable. Reverting to the late H. C. P. Bell once more, we have the following statement: "At this day it is not open to doubt that the whole Archipelago -- including Maliku (Minicoy) now grouped with the Lakkadives, and no longer owing allegiance to the Sultan of the Maldive Islands -- was occupied, either directly from Ceylon, or, alternatively, about the same time as the B. C. immigration into that Island, by people of Aryan stock and language. This supposition is supported greatly by the close kinship between the Maldivian and Sinhalese languages." (Bell, 1940). The Jataka stories mentions "a thousand islands" which is very likely to be the Maldives. References to the Maldives occur in Ptolemy (c. 150 AD), Moses [page II] Chorenensis (fourth century), Pappas of Alexandria (about the end of the fourth century), Cosmas Indicopleustes (sixth century) and Ammianus Marcellinus (fourth [cen]tury). Hieronymus Palladius of Egypt who died about the year 430 AD speaks of a thousands [sic] islands around Taprobane. Sulaiman the Merchant of Siraf (851 AD) wrote "The third sea is the sea of Harkand (Bay of Bengal). Between this and the sea of Lar (Gujurat) [sic] lie numerous islands. They say their number goes upto [sic] 1,900." Al-Masudi who visited Ceylon in 916 AD states "There are countless number of them [i. e. islands], 2,000 or more exactly 1,900." Fa-Hsien, who visited Sri Lanka in 412-414 AD speaks of small islands on every side of Sri Lanka. The Chinese writer Ma Huan speaks of "some small and narrow liu (dhiv = islands)". From these references we know that even as early as the dates mentioned in them, the islands that we today call the Maldives were known and populated, and therefore must have been expressing and conducting their affairs in a language -- which, surely, would have been none other than Dhivehi. Dhivehi language has had three distinctive periods of writings. The first script was called Eveylaa Akuru (ancient letters). It is not known when this form of writing began. The closeness of its form to the Sinhala script of the period suggests that it was an importation by the pioneering settlers of the Maldives. These letters were used until the reign of Sultana Khadeeja (first accession 1347 AD). A definite move away from the original Buddhism is shown in the writings of Eveylaa Akuru. This is visually illustrated in the Isdhoo and Dhabidhoo Loamaafaanu. A tendency to incorporate Arabic into the writings began possibly from before conversion to Islam. This is seen in these documents. These were written immediately after the official acceptance of Islam, which took many years after its contacts with the population through the extensive trade the Arabs and Persians had throughout the Indian Ocean. The trend to the free use of Arabic, both in meaning and in script, continue[s] even today. This movement away from the original Brahmi based form of writing gradually gave way to the next phase in the evolution of Dhivehi writing, which was Dhives Akuru (island letters). Both a religiously puritan drive and a furiously nationalistic movement helped the process of the evolution of Dhives Akuru. This is suggested even by the name of this script, which has close etymological connections with Dhivehi Raajje , Dhivehi Bas and Dhivehin themselves. This trend continued with a fuelling by the constant harassment [sic] by the South Indians, unbroken in the history of the Maldives. This also paved the way to the development of Dhivehi on its own course, away from the Indian languages. It is obvious from all available historical evidence that this was a tumultuous period in Maldivian history. With the ever looming threat to national independence and ways of life itself, it was imperative that a strong and a [page III] homogenous society with all the elements of nationhood, fitting tight, should take to the stage. One of the identities that the Maldives had to maintain was her language, Dhivehi with a unique system of writing and a distinctive literature. Besides the language we also see this period as the time of the evolution of a distinctive set of customs and traditions that formed the basis of Maldivian life. These were some of the realities that we have to accept in the evolutionary process of Dhivehi Akuru and consequently Dhivehi Bas. Dhivehi is now written in Thaana script. It is not known exactly when this script came into being or who brought it into being. But there are some salient features that indicate that Thaana itself was part of a strong reform movement that had its begin[n]ing after the country was liberated from the Portuguese occupation in 1573. Legend makes us believe that Thaana was first written in the reign of Sultan Ghazi Muhammed Thakurufaanu the Great (1573-1585), and was largely the inventive work of Sheik Muhammed Jamaaludhdheen, the great scholar. It has a vowel system close to Arabic. The first nine letters of Thaana are direct adaptations of Arabic numerals. Like Arabic it is written from right to left instead of left to right as the two former writing systems were. The very consistant [sic] and logical system of pronouncing the consonants in relation to the vowels clearly shows that this was the output of a disciplined [sic] and learned mind, well-versed in the art of writing. The introduction of Thaana as the writing system in the reign of Sultan Muhammed Thakurufaanu the Great (1573-1585) was one of the progressive steps taken by him after the liberation of the country from the Portuguese. It simplified the writing of Dhivehi. It put the writing on a logical footing making it easier to learn and so paving the way for further spreading of knowledge. The earliest Thaana script that survived to the modern times were the letters inscribed on the door posts of the main mosque (Hukuru Miskiy) of Kaditheemu (Shaviayani Atoll). It states the date of the roofing of the mosque. On one side of the frame the date given is 1008 AH (1599 AD) and on the other side the date given as the date of renewal of the roof is 1020 AH (1611 AD). These dates fall within the reigns of Sultan Ibrahim III (1585-1609), the son of Sultan Muhammed Thakurufaanu and Sultan Hussain II (1609-1620). Both these kings were preoccupied with other affairs of state and did not devote much energy to arts and culture. On 16 March 1957, 11 new letters were added to the Thaana writing system. These were modified versions of some existing Thaana letters, which were to replace the Arabic letters then used in writing Thaana. Again a rather more drastic measure was announced on 23 May 1977 by which Dhivehi officially adopted the Latin script. On that day the government announced a system of writing Dhivehi using the Latin script with some adaptations. Along with this two new letters also came into being. [page IV] We know that Dhivehi is a language that had and still has a literary history and form. We know clearly that by 1194 AD Dhivehi had a developed form and a definite script of its very own and a capacity to express intricate legal and official commissions. This is clearly shown in Dhabidhoo Loamaafaanu and Isdhoo Loamaafaanu. Though based on the foundation of Sanskrit, Dhivehi developed with little contact with the languages of India and quite on its own lines. Even though under the suzerain rule of the Chola Empire just prior to the adoption of Islam in 1152 AD, the influence exerted on the language seems to have been minimal and inclined towards Sri Lanka rather than India. But it is a noticeable fact that the northern Maldives did absorb more foreign influence in culture and language than the southern and the central atolls, especially the three southern-most atolls. Maliku (Minicoy) has retained an older stratum of Dhivehi than that spoken in the other northern atolls. The dialect that is spoken in these southern parts and Maliku is found to be closer to the original Dhivehi and contains fewer borrowed or absorbed words from foreign sources. This also can be partly attributed to the isolation these atolls were in before the advent of modern forms of transport and the powerful unifying force of radio broadcasts. It is another noticeable fact that all the island-names, without exception have an old Dhivehi base at their roots, be it in the north, centre or south of the Maldives. No island name did ever take any other form. The etymology of the vast majority of Dhivehi words could be traced to Sinhala Sanskrit and Pali, and they form the oldest strata of Dhivehi going to the pre-Islamic times. This is vividly evident when the terminology of the astrologer and the astronomer are looked into. The names of all the asterisms (Dhivehi: ނަކަތް ) and all the signs of zodiac (Dhivehi: ރާހި ) are examples. Another interesting point noticed is the subtle way the terms of a pre-Islamic system of belief have been turned to something maleficent and retained them in the language of the Muslim Dhivehin. This can be compared to the way the ancient Maldivians covered up and saved the places of worship they used for "another day." Good examples of this are seen in dhevi ( ދެވި ) which for Dhivehin of today is "mythical being capable of moving across the seas, land and other barriers, sometimes visible but more often invisible, helpful or harmful, requiring supplicaction [sic], sacrifice or even rebuke and censure." Another example is naamaroofa ( ނާމަރޫފަ ) "which is the name of a dhevi which comes to land from the sea once every year." Another very interesting word is han'gu ( ހަނގު ) which until very recent times applied to the militia of the Sultan. [The old Dhivehi word was san'gu ( ސަނގު ) ]. I am tempted to believe that this word evolved from the Sinhala saňga , Sanskrit saṃgha and Pali sangha which is a term implying "the community of bhikkhus" in all these languages. When the prevalent religion in the Maldives was Buddhism it was most likely a theocracy, like the many countries where this system still prevail, with the king at the apex of the state organisation and his [page V] helpers were the monks, who upon conversion took on the role of a militia but retained the name -- with a different purpose. In the course of my work I could not help taking note of the many points set down here. Dhivehi though with both the f ( ފ ) and p ( ޕ ) sounds now, has in many cases adopted the Sinhala, Sanskrit and Pali p sounds to an f ( ފ ) sound. This seems to have happened due to the influence of Arabic after the conversion, since in the oldest stratum of the language available to us in the form of the so far deciphered Loamaafaanu contain no f sound. Dhivehi fani ( ފަނި ) meaning worm; maggot, bacteria is paṇu, paṇuvā in Sinhala and prâṇaka in Sanskrit and pāṇaka in Pali. Dhivehi word fen ( ފެން ) meaning water is pän in Sinhala, pānīya in Sanskrit, Pali pānīya and Urdu and Hindi pānī . Another very frequent occurance [sic] is the change of Dhivehi sound s ( ސ ) to h ( ހ ) and vice versa. The word hihoo ( ހިހޫ ) meaning cool, mild, temperate is sisil in Sinhala, ṡītala in Sanskrit and sītala in Pali. Dhivehi word when inflected has the following formations: hihulun ( ހިހުލުން ), hihulaai ( ހިހުލާއި ) etc., which illustrates it more vividly. Again this is seen in the Dhivehi word han ( ހަން ) meaning distress signal given on a boat or an island indicating that urgent help was needed. The Sinhala equivalent is san, sana. In Sanskrit it is saṃ-jñā́ and in Pali it is saññā . Another occurance [sic] was the sound of Dhivehi sound of the letter Shaviyani ( ށ ) changing to a Sinhala ṭ sound. This is seen in the Dhivehi word bashi ( ބަށި ) meaning the egg-plant, aubergine, brinjal, melogene changes to Sinhala baṭu and Sanskrit bhaṇṭākī, bhaṇḍakī. Another example is the Dhivehi verb vashanee ( ވަށަނީ ) meaning to twist, to twine, to twirl; to ball, to make spherical. The Sinhala word is vaṭanavā . The Sanskrit word is vṛit, vártate, vártati and the Pali word is vaṭṭati. The change of sound that I have notices is the Dhivehi dh ( ދ ) to Sinhala y sound in words such as dhanthura ( ދަންޠުރަ ) meaning contraption, apparatus, artifice, mechanical contrivance, trap, ambush to Sinhala yantara, yantaraya, yantare; Sanskrit yantara and Pali yanta. Again, the same sound is seen changed in Dhivehi word dhathuru ( ދަތުރު ) meaning journey, excursion, expedition, odyssey, travel, trip, tour, voyage. In Sinhala it is yatura; in Sanskrit yātrā and in Pali yātrā. Dhivehi has four nasal sounds. They have always come before the following sounds: b ( ބ ), dh ( ދ ) , g ( ގ ) and d ( ޑ ) . All these sounds have their equivalents in Sinhala. In transliteration I have followed the official version that was announced on 23 May 1977. These come with b ( ބ ) sound in such words as an'bu ( އަނބު ) meaning mango. In Sinhala it is am̌ba; in Sanskrit āmra and in Pali amba. The nasal sound is also combined with dh ( ދ ) as in han'dhu ( ހަނދު ) meaning the moon. In Sinhala it is haňda, saňda; in Sanskrit it is candra and in Pali it is canda. The nasal sound is also combined with g ( ގ ) as in ban'gu ( ބަނގު ) meaning intoxicant, drug, narcotic. In Sinhala it is [page VI] baňga; in Sanskrit it is bhaṅgā; and in Pali it is bhanga. The other nasal sound in Dhivehi is that which comes with d ( ޑ ) as in gan'du ( ގަނޑު ) meaning an abscess, carbuncle. In Sinhala it is gaḍu, gaḍuva; in Sanskrit it is gaṇda and in Pali it is gaṇḍa. In some Dhivehi words when they are in the stem form the last letter is latent and when inflected this letter is seen and the etymology is found readily. One such case are words like han ( ހަން ) meaning skin, hide, leather; baloon [sic]. When inflected it is hamaai ( ހަމާއި ), hamun ( ހަމުން ) etc. In Sinhala it is ham, sam, han, hama; in Sanskrit it is cárman and in Pali camma; and gan ( ގަން ) meaning island, village, hamlet; domicile; which when inflected would b e gamaai ( ގަމާއި ), gamun ( ގަމުން ) etc. In Sinhala it is gam, gama ; in Sanskrit it is grā́ma and in Pali gāma . Other examples are words like maa ( މާ ) meaning flower, bloom [in Fua Mulaku this is pronounced as mal ( މަގް ) ] and baa ( ބާ ) gap, cavity, hollow, hole. When inflected these become malaai ( މަލާއި ), malun ( މަލުން ) etc., meaning flower. In Sinhala it is mal, mala; in Sanskrit it is mālā andin Pali mālā. Similarly, baa ( ބާ ) would be balaai ( ބަލާއި ) balun ( ބަލުން ) etc. In Sinhala it is bila; in Sanskrit bila, vila and in Pali bila. Another example is found in words like niboo ( ނިބޫ ) meaning twin and nagoo ( ނަގޫ ) [in Fua Mulaku this is pronounced as nagul ( ނަގުލް ) ] meaning tail. Niboo ( ނިބޫ ) when inflected would be nibulaai ( ނިބުލާއި ), nibuleh ( ނިބުލެއް ) etc. In Sinhala it is nim̌bul, nim̌bullu. Similarly, nagoo ( ނަގޫ ) when inflected would be nagulaai ( ނަގުލާއި ), nagulun ( ނަގުލުން ) etc. In Sinhala it is nagula, nagul; in Sanskrit is is [sic] lāṅgūla and in Pali naṅgula, laṅgula. Another instance of this type is the th ( ތ ) with a sukun ( ް ) at the end of words such as aiy ( އަތް ) and faiy ( ފަތް ) . The word aiy ( އަތް ) meaning hand, palm; side, direction, when inflected would be athun ( އަތުން ), athaai ( އަތާއި ) etc. In Sinhala it is at, ata, hata; in Sanskrit it is hásta and in Pali it is hattha. Similarly, faiy ( ފަތް ) meaning leaf, palm (of plants and trees); official proclamation, missive, epistle, deed (all these were written on leaves at one time); feather, would be fathaai ( ފަތާއި ), fathun ( ފަތުން ) etc. In Sinhala it is pat, pata; in Sanskrit it is pattra; in Pali patta and in Urdu pati. Arabic came into Dhivehi en masse for religious purposes after the adoption of Islam, mainly for the expressions used in religious phraseology. At the same time it may be noted that quite a number of Dhivehi words were given up and Arabic, Persian or Urdu words substituted by some who held the view that these Dhivehi words did not convey the meaning that they desired or who simply did not know Dhivehi proper. But the constant contact with Arab and Persian traders of the Indian Ocean allowed some words of a non-religious nature also to come into the language. This is seen in the adoption of many words in the field of navigation and shipping. The inclusion of adopted Arabic words such as kan'dhili ( ކަނދިލި ) in the Isdhoo Loamaafaanu gives us clues on when these words came into Dhivehi. It is evident from Isdhoo Loamaafaanu that Persian words were used in that early times in Islamic religious contexts frequently. For in that document the words roada ( ރޯދަ ) and namaadhu ( ނަމާދު ) appear [page VII] distinctly and in their Persian meanings. It is surprising to note that the equivalents of these in Arabic seems [sic] to have never been in use. Dhivehi being a language spoken by a small group of people, scattered over a wide geographical area, and all those who spoke Dhivehi following one religion, it did not have a 'reserve' of its linguistic treasures expressed or recorded in a different perspective in the past nine centuries or more. But we know from the Loamaafaanu and the remnants of some material in the language itself that in its long history Dhivehi has made an attempt to preserve these in a significant way. This goes a long way to show the adaptability and resilience of Dhivehi itself, if not to say the conservative nature of Dhivehi and Dhivehin themselves. This is more so when the all[-]pervading puritan nature of the new religion Dhivehin adopted is taken into account, and when it comes to light that the custodians of the linguistic heritage turnout to be the innovators themselves. Dhivehi has a few words that have a Portuguese etymological base. The great majority of these came through Sinhala, or a Sinhala equivalent could be found. Dhivehi words paan ( ޕާން ) (bread), feyru ( ފޭރު ) (guava), alavangu ( އަލަވަންގު ) (crowbar, handspike) and alamaari ( އަލަމާރި ) (almirah, cabinet, cupboard) are examples. These correspond to Sinhala pān., pāṇ (bread), pēra (guava) alavaṇguva (crowbar) and almāri, almāriya (almirah) Urdu & Hindi almārī (a chest of drawers, a book-case, a cabinet). These in turn could be traced to Portuguese pāo (bread), pêra (pear), alavanca (lever , crowbar) and armário (cupboard, cabinet, chest). The most striking and only instance of a direct adaptation from Portuguese that I came across is the word miskiy ( މިސްކތް ) which in Portuguese is mesquita. In its inflections ( މިސްކިތާއި‘ މިސްކިތުން‘ މިސްކިތުގެ ) the relationship is more vividly seen. This word seems to have appeared in documents after the short stint of Portuguese rule (1558-1573) in the Maldives. The word used by the Maldivians before in this context was dhanaaru ( ދަނާރު ) and in some older documents (Isdhoo Loamaafaanu - 1194) the Arabic word masjid in its Dhivehi variations such as masdhidu ( މަސްދިޑު ) were used. There are a few words with Dutch roots in Dhivehi. Almost all of these came through Sinhala. Dhivehi words boaku ( ބޯކު ) (arch, span), foanchu ( ފޯންޗު ) (teapot) and sulufu ( ސުލުފު ) (sloop) are examples. These correspond to Sinhala bōkku, bōkkuva (arch); pōchchi, pōchchiya (jug) and suluppu, suluppuva (sloop) respectively. These in turm [sic] could be traced to Dutch boog (arch), potje (pot) and sloep (sloop). Though in general Dhivehi developed isolated from the Indian languages, there are many Urdu words and derivatives in Dhivehi. Most of these are of an intellectual nature. This could be attributed to the fact that the language of the Muslims of much of the Indian sub-continent has been Urdu and the few Maldivians who studied religion [page VIII] there did so through the medium of Urdu. There are some Hindi words too. But these are generally from a trader's or a sailor's vocabulary, where ever they are not common with Urdu. So are many words from various other Indian languages of the co[a]stal regions of South India, such as Bengal. These were the regions with which Maldives had traditional trading links and the majority of these words have come into Dhivehi in the last two centuries. For the one and half centuries of frequent contact with the Borahs brought in many words from their tongues, especially after they were given permission to set up their shops in Male' in 1857. It is surprising to note that some English words in Dhivehi are not very modern adaptations. Words like thafureelu ( ތަފުރީލު ) meaning taffrail (of a vessel), iskaraabu ( އަސްކަރާބު ) meaning scraper, drawknife, drawshave, spokeshave; and manavaru ( މަނަވަރު ) meanin[g] man-of-war, warship, battle ship, are not very new. But there is one common thread running in all such adoptaions [sic], i. e. they all come in the fields of ships and shipping. We know that in the year 1836 Sultan Muhammed Imaadhudhdheen IV sent his officers and shipwrights to Bengal to learn this trade from the English who were there then. There are a few words in Dhivehi the etymology of which could be traced to Tamil, such as aveli ( އަވެލި ) meaning beaten rice, flaked rice and fataas ( ފަޓާސް ) cracker, firecracker, squib. There are also Tamil words that has come to Dhivehi through Sinhala or which are shared by both Dhivehi and Sinhala with a Tamil root. Examples are Dhivehi aadaththoda ( އާޑައްތޮޑަ ) meaning Malabar nut (Adhathoda vasica), Sinhala ādathoda , Tamil ādathodai and Dhivehi fan'gu ( ފަނގު ) meaning share or division of cultivated land, Sinhala paňgu Tamil pangu. The number being so few surprises me. For the vernacular of Sri Lankan Muslims being Tamil and the age-old common factors to them through the common religion of Islam and the close proximity and contacts did not make the Maldivians borrow more, especially in the phraseology of faith. There is a sprinkling of words of Malay origin in Dhivehi such as kanbalhi ( ކަންބަލި ) meaning sheep, ram, ewe, lamb and kiris ( ކިރިސް ) meaning dagger, dirk, kris. There are also some words that has come to Dhivehi thro[u]gh Sinhala or which are shared by both Dhivehi and Sinhala with a Malay roots. Examples are gnamgnam ( ޏަމްޏަމް ) meaning the tree and fruit of Cynometra cauliflora , Sinhala namnam Malay namnam and gudhan ( ގުދަން ) meaning store, godown, warehouse, Sinhala gudan , gudama Malay gudang. In the case of direct links with Malay it is easily understood when the strong trade links that existed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are taken into account. Though there always were links between Maldives and the East Indies and Malay peninsula the links were very strong in the period mentioned. This [page IX] was especially so with the Acheh (Dhivehi: އަސޭކަރަ ) According to one theory the people of East Indian origin who crossed the Indian Ocean to Madagascar made the Maldives their mid-way station on these long voyages. It may also be mentioned here that there are many words which Dhivehi share with Malay which both languages got through Arabic and Sanskrit. The long history of the Dhivehi language has seen many teachers who made contributions towards its development and the foundation of its grammar. But this long history is lost in the mists of time. We have only the comparatively recent works available to us. The earliest and foremost of them are the works of the great master Edhur Umar Maafaiy Thakurufaanu. The greatest of his extant works is Bodu Thaaheedu ( ބޮޑު ތާހީދު ). This is a poetical composition consisting of 398 verses and lays down the rules of poetical form and the grammar of the language. It was composed in 1150 AH (1737-38 AD). He was followed by another great poet, Badeyri Hassan Manikufaanu, among whose extant great works are the two poems Dhekunu Arumaadhu ( ދެކުނުއަ ރުމާދު ) and Dhioage Raivaru ( ދިޔޯގެ ރައިވަރު ). Besides revealing his poetical skill and linguistic mastery he also gives us in this the grammatical of the language. He was born in 1745 AD in Addu Atoll. For most of his life be lived in Male' and was among the courtiers of Sultan Muhammed Mu'eenudhdheen I (1799-1835 AD). He died on the island of his birth on 4 April 1807. The next great figure in this field was Sheik Muhammed Jamaludhdheen who was popularly known by the name Naibu Thuththu. He was the son of Easa Naibu Thakurufaanu of Fua Mulaku. Easa Naibu Thakurufaanu was a senior judge between 1787 and 1831. When Sheik Jamaaludhdheen was yet a young child his father died. His mother, Mariyam Fulhu married Naib Ahmed Manikufaanu who was a senior legal figure and a pundit of the Dhivehi language and functioned as acting Chief Justice in 1831. It was young Jamaaludhdheen's step-father who was his first teacher. Later the young scholar went to Sri Lanka and studied at Beruwela. He returned to Male' in 1883. In 1886 he travelled to Mecca on Hajj pilgrimage and spent some time studying under the famous scholars there. In 1886 he was appointed the acting Chief Justice but within a short period of time was banished to Fehendhoo (in Baa Atoll) in a political upheaval in Male'. It was here on the island of Fehendhoo that he wrote his book on the grammar of Dhivehi which was published 24 years after it was written and long after the author's death. He was re-instated as the Chief Justice in the reign of Sultan Imaadhudhdheen VI (1893-1903), but within about a year of his being appointed he gave up the high office and functioned as a senior assistant judge. In 1903 Sheik Jamaludhdheen was again banished in another change in the office of the Sultan. This time it was to the island of Maa-eboodhoo (in Dhaalu Atoll) and died there on 29 October 1907. Besides his grammar of Dhivehi there are many of his works in the fields of religious teachings and poetry among us today. Sheik Jamaaludhdheen's [page X] pupil and disciple was Sheik Hussain Salaahudhdheen. He was the son of Bodugaluge Moosa Didi and was born in Male' on 11 May 1881. At the young age of 18 years he was appointed a senior assistant to the Chief Justice in the reign of Sultan Muhammed Imaadhudhdheen VI (1893-1903). He was appointed Chief Justice on 17 December 1927 and held that post until the poroclamation [sic] of the first written constitution of the Maldives on 22 December 1932, when he was appointed the Minister of Justice. He was appointed the Chief Justice again on 11 April 1936 and held the high office until his death in Colombo on 20 September 1948. When Majeedhiyya School was opened on 20 April 1927, he was appointed the principal. Besides being an eminent Islamic scholar and the leading legal figure of his day, he gave much to Dhivehi language. His compilation of the Holy Prophet's biography in three volumes stands as a lasting memorial to his learning and scholarship. It is also testimony to his [in]fluence and forceful expression in the Dhivehi in its classic form. He has been the most prolific writer in the Dhivehi language. It was he who penned the following lines, which clearly shows the depth of his knowledge of the etymological basis of the language. ފުރައަމެންގޭ މާދަރީބަސް އެކުވެގެންވެއެ އުފެދިގެން " ކުރެވިދާ ހިނދު ފިކުރުގިނަބަސް އެކުވެގެން ޝަރްގަށް މިވާ ސެންސިކިރްތާ‘ ޕާލިޔާ‘ ސިންހަޅަ‘ ތަމަޅަ ފެނެޔޭ ނިކަން ފެންނަހެން ޢަރަބީގެ ބަސްތައް ފާރިސީއާ ޕޮސްތުވާ ހަމަ އެފަދައިން ހުރެދެޔޭ ޔޫރަޕްގެ ބަސްތައްވެސް ލިބޭން " ނަމަބަލައިހޯދައި އުޅެފި ކަތަކަށް ރަނގަޅު ހަމަ ބުއްދިވާ "Our mother tongue as it evolved and alloyed [Took to it] languages of the east as seen when studied Sanskrit, Pali, Sinhala, Tamil are seen evidently Words from Arabic, Persian and Pushtu are perceived plainly At hand are words from European languages too If searched by a person of rational thinking." The greatest Dhivehi poet of modern times was Sheik Hussain Afeefudhdheen. He was the son of Sayydh Muhammed and was born in Male' on 19 May 1888. A student of Sheik Hussain Salahudhdheen, he soon became his star-pupil, especially in the field of Dhivehi. He was appointed the Chief Justice on 2 August 1933 and later became the Minister of Education on 30 January 1937. He was a member of many panels that worked on Dhivehi language. He was the author of a book on the Dhives Akuru writing system. He transliterated many old Dhives Akuru writings to modern Thaana. He passed away in Male' on 2 June 1970. The late Muhammed Amin Didi, [page XI] the President of the First Republic of the Maldives ushered in a period of complete change in Dhivehi literature. It was he who began teaching of Dhivehi as a subject in Maldivian schools. It was also he who pioneered the modern forms of writing, both in prose and poetry. His charismatic efforts changed the language in its every aspect and set the course to its development on modern lines. He must also be remembered for the contributions he made to the grammar of the language in his book Dhivehi Bas - Dharivarunge Eheetheriyaa ( ދިވެހިބަސްދަރިވަރުންގެއެހީތެރިޔާ ) . It was he under whose leadership began the compilation of the first ever Dhivehi dictionary, which today we have as Dhivehi Basfoiy ( ދިވެހިބަސްފޮތް ) in its ma[n]y volumes, by appointing a committee for this purpose on 11 July 1946. It was also he who awakened the country into the modern world and re-kindled Maldivian nationalism. He died on the island of Vihamanaafushi (now the tourist resort Kurumba Village) on 19 January 1954. Sheik Ibrahim Rushdhi rendered great services to education in general and to Dhivehi language in particular. He was born on Kelaa island (Haa-Alif Atoll) on 15 October 1897 and had his education at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. His most valuable contribution was his grammar of Dhivehi, Sullamul Areeb ( ސުއްލަމުލް އަރީބް ). Though rarely seen now, this is one of the fundamental books on Dhivehi grammar. He died in Male' on 29 October 1961. Another great personality who rendered valuable service to Dhivehi was Sheik Malim Moosa Maafaiy Kaleygefaanu, who was born in Male' on 10 June 1883. A man of great learning and much hard work, his greatest contributions were the two lexicons Al Eagaaz’ Fee Tha'uleemu Alfaaz' ( ފީތައްލީމުލްއަލްފާޡް ) and Dhivehi Bahuge Ran Thari ( ހަލްފާޡްފީތައްލީމުލް ). two contained a[n] Arabic-Dhivehi and Dhivehi-Arabic vocabulary and some sentences. This compilation contains some of the old words of Dhivehi and their equivalents in Arabic. The latter was a dictionary of the Dhivehi language. In this book he gives a number of Dhivehi words in sentences and by this illustrates their meanings. He died in Male' on 18 November 1970. The last great teacher of Dhivehi in terms of chronology was Sheik Muhammed Jameel. He was born to a distinguished family of scholars in Male' on 14 May 1915 and was appointed the Chief Justice on 2 January 1958. He contributed to Dhivehi, its literature, poetry and to Islamic learning in the Maldives in abundant measure. His books on religious studies still remain the most popular and simple to understand texts by the common man. His poetry became legendary in his lifetime for the eloquence of expression and profundity of thought. His plays, short stories and many essays on various branches of Dhivehi are among the most erudite on the subject. He passed away at the age of 74 years on 15 March 1989 in Male'. There are many non-Maldivians who rendered great services to Dhivehi language. Pioneering work in this field was done by François Pyrard de Laval. He was shipwrecked in the Maldives in July 1602 and lived there till he set sail to Bengal in [page XII] 1607. In his account of the Maldives of his day a very full description of what he saw is given. He also mentions many Dhivehi words and their meanings, though it is difficult to recognise them now as he was pronouncing these in his native Fre[n]ch , accent. A vocabulary is also given. A valuable study of Dhivehi language and the script then used is given in "Vocabulary of the Maldivian language" [Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1st series) Vol. 6 (1840-41)] by Lieut. W. Christopher who was one of the two [the other being Lieut. I. A. Young] British (Indian) Navy officers who were in the Maldives on a surveying expedition in 1835. According to Dhivehi Thaareekh ( ދިވެހިތާރީޚް ) "after that [i. e. their arrival] the two persons who stayed in Male' and the others who were with them endeavoured to learn the language spoken now and spoken earlier by the people of this country. The way they tried [to do this was] to go to the cemet[e]ries within the mosque [compounds] and copying on paper the inscriptions on tomb-stones. They showed these to people. Some people read these for them, others did not." Modern research of Dhivehi may very well be attributed to Prof. Wilhem Geiger. In his monumental work on Dhivehi language "Maldivian Linguistic Studies" [Journal of the Ceylon Branch of The Royal Asiatic Society, 1919, Vol. XXVII - Extra Number] stands out as the first scientific study of the language. Three learned papers, titled Máldivsche Studien I, II, III (in Sitzungsberichte der Kgl. Bayer, Akademie der Wissenchaften of Munich pp 107-132, 371-387 and 641-684 with one plate headed Màldivsche Alphabete) were translated by Mrs. J. C. Willis and edited by Mr. H. C. P. Bell was published, as mentioned above in 1919. Albert Gray’s works on the Maldives, though not of a linguistic nature altogether, contain some useful information of the periods on which he wrote and some expl[a]nations of older writings. His major work was "The voyage of François Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies , the Maldives , the Moluccas and Brazil." This was published by The Hakluyt Society in 1887-89 in London. The other important work by the same author was "The Maldive Islands: with a vocabulary taken from François Pyrard de Laval, 1602-1607” in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (new series) Vol. 10 (1878). The late Mr. H. C. P. Bell rendered much service to Dhivehi. But his services in this field are vastly overshadowed by what he did in the fields of Maldivian history and archaeology. Besides his valuable three monographs (1883, 1921 & 1940), the many articles that appeared in the Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch are testimony to this. Special mention must be made of the series "Excerpta Maldiviana" which appeared in the abovesaid journal from 1922 to 1935. These are mines of information for any student of the Dhivehi language and taken for their linguistic and historical value they are rarely surpassed. The three papers of M. W. Sugathapala de Silva enlighten us in more than one aspect of Dhivehi. His first paper "The phonological efficiency of the Maldivian writing system" appeared in Anthropological Linguistics Vol. 11, No. 7 (Bombay, October 1969). The second [page XIII] paper was " Some observations on the history of Maldivian" which appeared in Transactions of the Philological Society of Great Britain (1970) and the third paper was " Some affinities between Sinhalese and Maldivian " which appeared in Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Roayal [sic] Asiatic Society, (New Series) Vol. XIV (Colombo, 1870). Prof. C. H. B. Reynolds contributed much to Dhivehi studies. His connections with the Maldives from 1967 and his study of the language made him one of the few western scholars of the language. Among his writings are "Buddhism and the Maldivian language" (In: Buddhist studies in honour of I. B. Horner, edited by L. Cousins, A. Kunst, K. R. Norman. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Reidel, 1974) and "Linguistic strands in the Maldives." (Contributions to Asian Studies, Vo. II; 'Language and civilization change in South Asia', edited by C. Maloney, Leyden 1978). The most substantial and the latest work on Dhivehi is the "Historical and Linguistic Survey of Divehi. " This is a work carried out by a team of scholars under the auspices of the University of Colombo. It dealt with among other aspects (1) a study of the origin and development of Dhivehi and determined the genetic affinity with Sinhala; (2) the evolution of Dhivehi and the impact of other languages on it; and (3) record and analyse the dialectological variations in Dhivehi. The team who worked on this project was lead [sic] by Prof. Stanley Wijesundara, the Vice-Chanceller [sic] of the University of Colombo. Other members of the team were, Prof. G. D. Wijayawardhana, Prof. J. B. Disanayaka, Mr. Hassan Ahmed Maniku and Mr. Mohammed Luthfie. The final report of this project was submitted in 1988 and it is yet to be published. The two Loamaafaanu so far read and partly evaluated throw some light on the oldest strata of Dhivehi language. The first to be published was the Dhabidhoo Loamaafaanu published by the National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Studies, Male' in 1982. Work on this was done by Prof. G. D. Wijayawardhana, Prof. J. B. Disanayaka and H. A. Maniku. The other Loamaafaanu which has been read so far is the Isdhoo Loamaafaanu which was published in Colombo by the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka in 1986. This work which was done by Prof. G. D. Wijayawardhana and H. A. Maniku. Bell speaks about a number of Loamaafaanu (Bell 1940) and goes to transliterate and tra[n]slate on of them, the Bodugalu Miskit Loamaafaanu , which he dates to 1356-57. [This same work appeared in the Journal of The Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch Vol: XXXI, No: 83, Parts I., II., Ill & IV in 1930]. Of late very useful work on Dhivehi has been done by Bruce D. Cain. One of his works, "Maldivian Prototypical Passives and Related Constructions" appeared in Anthropological Linguistics, (Vol. 37, No. 4, 1995) and his other work which is his dissertation for a doctorate titled "Dhivehi (Maldivian): A Synchronic and Diachronic Study " has not been published yet. While doing field work in connection with the abovementioned "Historical and Linguistic Survey of Divehi", it was thought that work should be started on a [page XIV] vocabulary of Dhivehi etymology. If I remember correctly, it was in Fua Mulaku and the date was the third of January 1987. Prof. Wijayawardhana, Prof. Dissanaya and I were discussing the meaning and place of han ( ހަން ) [meaning: distress signal given on a boat or an island indicating that urgent help was needed] in the life of Maldivians. From this discussion sprang the idea of a project of this nature. Upon returning to Colombo work began -- at a very slow pace. Whenever I happened to be in Colombo work went on. I had a card index system and notes on these were made by the three of us, intermittently. Several hundred cards were filled and filed. But in 1995, it so happened that Destiny decreed a longer sojourn for me in Colombo and work was started in earnest. With the help of a personal computer and relevant programmes, work was made easier, faster and more accurate. Even with all these modern technology it took me over five years to complete this. It was hard work and accuracy was of utmost importance. References were many and copying them faithfully with all the diacritical marks were not the easiest tasks on earth. After every entry I had to check and re-check. Dhivehi entries had to be done -- in the opposite direction. After all these I now have the completed version on hand. Complete as much as I could do it. Deep as much as I could fathom. As it is now I do not claim an entry for every Dhivehi word. This work is as incomplete as one may think it is, at the same time it is as complete as one thought it fit to be. As far as I am aware it is the first and only attempt by a Maldivian in this field so far. It is a Maldivian's portrayal of his mother tongue. It is the insight a Maldivian has into his language as spoken and understood by Maldivians. In this work I have used the established transliteration rules prevailing in the Maldives. Along with every major entry I have also inserted the Dhivehi word in Thaana script so that the precise word is available for those who read Thaana. Before concluding I must thank the two distinguished scholars who helped me and encouraged me to carry on with this work. Their guidance, pushing and prodding kept me going. It was Prof. G. D. Wijayawardhana and Prof. J. B. Disanayaka of University of Colombo who must be thanked at every step on the way to completion of this work. It is a great pleasure for me to thank The Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka for the offer of publishing this work under its esteemed auspices. The Royal Asiatic Society has been the pioneer in the field of Maldivian studies for the last one and quarter centuries. As far as I am aware this society has published the largest volume of work on the Maldives, some of which today we see in reprints. This alone goes to show the scholarly value of these works and the demand that there exists for the valuable publications of the Society. It is to the Society that we have thank for the monumental [page XV] works of the late H. C. P. Bell, Sir Albert Gray, Prof. Wilhelm Geiger and many more on the Maldives. އަސަރަކާ އަދި ފޮނިކަމެއް‘ އެކި ބަސްބަހުން ހަމަ ފެނުނަކަސް‘ " " އަސަރުގަދަ އަދި އެންމެ ފޮނިބަހަކީ‘ މަށަށް މި ދިވެހިބަހޭ‘ - މުޙައްމަދު އަމީން - "Though impressiveness and sweetness are seen in various languages Forceful in impression and sweetest language for me is this Dhivehi language. " -Muhammed Amin- I dedicate this work to my family, especially to the three loving grand children, Hassan, Muhammed and Ibrahim. To them all for their understanding and for affording me a great life full of happiness and fulfilment. To the three younger ones for their love shown in abundant measure and for the grand opportunity of giving all the rest of us a zest for life and confidence in a future. Hassan Ahmed Maniku, 9 September 2000. Colombo, Sri Lanka. [page XVI] REFERENCES In the course of working on this introduction and the main body of this book I had recourse to the following books. Many computer software material available in the open market including dictionaries, encyclopaedias and language programmes were consulted. They were too many and varied to be named here. AMIN DIDI, Muhammed Dhivehi Bas Dharivarunge Eheetheriyaa, ‘ ދިވެހިބަސްދަރިވަރުންގެއެހީތެރިޔާ Male’.

BELL, H. C. P.

Excerpta Máldiviana, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras 1998.

The Maldive Islands, Monograph on the History, A[r]chaeology and Epigraphy, Ceylon Government Press, Colombo 1940.

CHILDERS, R. C.

A Dictionary of the Pali Language, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras 1993.

CLOUGH, The Rev. B.

Sinhala English Dictionary, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras 1996.

COENDERS, H. (Managing Editor)

Kramers, Dictionary, Dutch-English, Thirty-eighth edition.

[page XVII]

COOPE, A. E.

Malay-English, English-Malay Dictionary, Student Edition, Macmillan Malasia [sic], Kua Lumpur & Penang.

DE SILVA, M. W. Sugathapala

The Phonological Efficiency of the Maldivian Writing System, In: Anthropological Linguistics , Vol. II, No. 7 (October 1969). Bombay 1967.

Some observations on the History of Maldivian, In: Transactions of the Philological Society of Great Britain, London/Oxford 1970.

Some Af[f]inities Between Sinhalese and Maldivian, In: Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, New Series, Vol. 14, Colombo 1970.

DHIVEHI THAAREEKHAH AU ALIKAMEH,

‘ ދިވެހިތާރީޚަށްއައުއަލިކަމެއް Ministry of Home Affairs, Male'.

DHIVEHI BAS FOIY,

‘ ދިވެހިބަސްފޮތް National Centre for Language and Historical Research, Male'.

DHIVEHI THAAREEKHAH,

‘ ދިވެހި ތާރީޚް National Council for Linguistic and Cultural Research, Office of the President, Male' 1981.

[page XVIII]

DISANAYAKA, J. B. & G. D. WIJAYAWARDHANA

Some Observations on the Maldivian Loamaafaanu Copper Plates of the Twelfth Century, In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society , Sri Lanka Branch . New Series, Vol. 31 (1986/87). Colombo.

ELIAS A. ELIAS & ED. E. ELIAS,

The School Dictionary, English to Arabic, Arabic to English, Islamic Book Service, New Delhi.

GEIGER, Wilhelm

An Etymological Glossary of the Sinhalese Language, The Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch, Colombo 1941.

Maldivian Linguistic Studies, In: Journal of the Ceylon Branch of The Royal Asiatic Society, Vol: XXVII - Extra Number 1919, Colombo 1919. (Reprint Asian Educational Services 1996).

GUNAWARDENA, D. C.

Genera et Species Plantarum Zeylaniae, Flowering Plants of Ceylon, An etymological and historical study. Lake House Investments Ltd., Colombo.

A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, (Edited by J. Milton Cowan), Librairie du Liban, Beirut, Macdonald & Evans Ltd., London.

HARRISON, John

A Field Guide to The Birds of Sri Lanka, Oxford University Press 1999.

KEMP, Peter (Ed.)

The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, Oxford University Press, 1988.

KING, Peter & Margaretha

Concise Dutch and English Dictionary, Dutch-English/English-Dutch, Teach Yourself Books.

LAMB, N. J.

Collins Gem Dictionary, English - Portuguese Portuguese - English, William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1984.

MALIM MOOSA MAAFAIY KALEYGEFAANU,

އަލްއީޤާޡް ފީތައްލީމުލްއަލްފާޡް Al Eagaaz' Fee Tha'uleemul Alfaaz', Male' 1937.

MONIER-WILLIAMS, Sir Monier

A Sanskrit-English Dictionary; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi 1984.

NEW EDITION POPULAR OXFORD DICTIONARY,

Part 1 English to English & Urdu, Part 2 Urdu to Urdu & English, Oriental Book Society, Lahore.

OXFORD PAPERBACK PORTUGUESE DICTIONARY,

Portuguese-English, English-Portuguese, Oxford University Press, 1996.

RHYS DAVIDS, T. W. & WILLIAM STEDE,

Pali-English Dictionary, Oriental Books Reprint Corporation, New Delhi 1975.

STEINGASS, F.

Arabic-English Dictionary, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras 1993.

A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary, Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore 1977.

GUIDE TO TRANSLITERATION OF DHIVEHI

AKURU (Consonants):

Haa: ( ހ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " h " and is written with the letter h . It is pronounced as in h ear and h it. This is the ordinary aspirate.

Shaviyani: ( ށ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " sh " but it is closer to " r " and is written sh . Prof. Wilhelm Geiger in his Maldivian Linguistic Studies says: "expresses a sound peculiar to the Maldidvians, to which the (cerebral) t in Sinhalese is most closely allied. The sound is very difficult to describe and to imitate. It varies between R, H, and S; is rather soft; and is, so fa r as I could observe uttered by putting the tip of the tongue in the highest part of the palate, and letting the breath escape sideways between the teeth."

Noonu: ( ނ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " n " and is written with the letter n . It is pronounced as in n one and ow n , but with a lighter tone.

Raa: ( ރ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " r " and is written with the letter r . It is pronounced as in r ed and r ude.

Baa: ( ބ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " b " and is written with the letter b . It is pronounced as in b ear and ri b .

Lhaviyani: ( ޅ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " lh " and it is pronounced a deep l with the tongue reverting to the palate.

Kaafu: ( ކ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " k " and is written with the letter k . It is pronounced as in k ill and see k .

Alifu: ( އ ) Phonological value given to this letter are " a , e , i , o and u ". These values are taken by the letter in accordance with the fili and the position it occupy in the word and it is closely influenced by the vowel the consonant is given. It is pronounced as a , e , i , o or u .

Vaavu: ( ވ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " v " and it is pronounced as v and w . It is pronounced as in v i v id and gi v e.

Meemu: ( މ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " m " and it is pronounced as m . It is pronounced as in m ap and ja m .

[page XXII]

Faafu: ( ފ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " f " and it is pronounced as f . It is pronounced as in f i f ty and cu ff .

Dhaalu: ( ދ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " dh " and it is written as dh . It is pronounced as the sound in th is, th at and th en.

Thaa: ( ތ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " th " and it is written as th . It is pronounced as the sound in th ick, th in and e th er.

Laamu: ( ލ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " l " and it is written as l . It is pronounced as in l u ll and l ead.

Gaaf: ( ގ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " g " and it is written as g . It is pronounced as in g un and do g .

Gnaviyani: ( ޏ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " gn " and is written as gn . It is pronounced as mi n ion.

Seenu: ( ސ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " s " and is written as s . It is pronounced as in s aint and hi ss .

Daviyani: ( ޑ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " d " and is written as d . It is pronounced as in d ice and a d ult.

Zaviyani: ( ޒ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " z " and is written as z . It is pronounced as in z one and z odiac.

Taviyani: ( ޓ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " t " and is written as t . It is pronounced as in t ie and t ree.

Yaviyani: ( ޔ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " y " and is written as y . It is pronounced as in y et and lo y al.

Paviyani: ( ޕ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " p " and is written as p . It is pronounced as in p e pp er and si p .

Javiyani: ( ޖ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " j " and is written as j . It is pronounced as in j am and j ump.

Chaviyani: ( ޗ ) Phonological value given to this letter is " ch " and written as ch . It is [page XXIII] pronounced as in ch in and ch ange.

FILI (Vowels):

In Dhivehi writing the fili, which occupy the value of a vowel is written either at the top or beneath a consonant and the consonant letter cannot be pronounced unless it is given a vowel accompaniment. Without this diacri[ti]cal mark a letter is only a neutral sound. The diacritical marks used for fili and their values are:

Aba fili: ( ަ ) Phonological value given to this is " a ", and it is pronounced as the sound in m u d, c u t and h u mdr u m. It is a short vowel. It is always written on top of a letter.

Aabaa fili: ( ާ ) Phonological value given to this is " aa ". It is the sound of Aba fili lengthened, and is pronounced as the sound in f a ther and c a rter. It is a long vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

Ibi fili: ( ި ) Phonological value given to this is " i ". It is pronounced as the sound in p i n, b i t, h i d and t i p. It is a short vowel and is always written beneath a letter.

Eebee fili: ( ީ ) Phonological value given to this is " ee ". It is the sound of Ibi fili lengthened, and is pronounced as the sound in s ee n, h ee d, m ea t and bl ee d. It is a long vowel and is always written beneath a letter.

Ubu fili: ( ު ) Phonological value given to this is " u ", and is pronounced as the sound in p u ll, p u t and b u ll. It is a short vowel and always written on top of a letter.

Ooboo fili: ( ޫ ) Phonological value given to this is " oo ". It is Ubu fili lengthened, and is pronounced as the sound in r u le, sh oe s and l o se. It is a long vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

Ebe fili: ( ެ ) Phonological value given to this is " e ", and is pronounced as the sound of b e d and b e t. In pronunciation of this vowel in Dhivehi the lips are more spread out than in English. It is a short vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

Eybey fili: ( ޭ ) Phonological value given to this is " ey ". It is Ebe fili lengthened. There is no equivalent in English for this. The closest is the diphthong " ei ". It is pronounced somewhat as the sound in s a y and f a n. It is a long vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

[page XXIV]

Obo fili: ( ޮ ) Phonological value given to this is " o ", and is pronounced as the sound-in s o ft, d o t and c o t. It is a short vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

Oaboa fili: ( ޯ ) Phonological value given to this is " oa ". It is the Obo fili lengthened. There is no equivalent in English for this. The closest is to pronounce it as in c au ght, b ou ght, g oa t and a ll. It is a long vowel and is always written on top of a letter.

Sukun: ( ް ) Phonological value of this varies according to the position in wh[i]ch it is used. When it comes at the final position of a word with either Alifu or Shaviyani the end is abrupt and the value used is " h ". In this case this value stands for a letter that has "disappeared" in that particular case, but comes back when the word is either joined with another word or used in full. When Sukun comes with the consonant Thaa it is pronounced almost same as "disappearing" sound. It is now standard to represent this phonological value with " iy ". Sukun when accompanied with other consonants are easy to read and there is no confusion. It is always written on top of the consonant, the phonological expression which it has to convey.

ABBREVIATIONS

| adj. | adjective |

| adv. | adverb |

| Ar. | Arabic |

| arch. | archaic |

| Cf. | compare |

| conj. | conjunction |

| excl. | exclamation |

| Ft. | future tense |

| Hind. | Hindi |

| i. e. | (that is to say) |

| int. | interjection |

| Mal. | Malay |

| n. | noun |

| P. | Pali |

| part. | particle |

| Pers. | Persian |

| Port. | Portuguese |

| Pr. | present tense |

| pron. | pronoun |

| Pt. | past tense |

| q.v. | (which see) |

| Sin. | Sinhala |

| Sk. | Sanskrit |

| syn. | synonym |

| Tam. | Tamil |

| Urd. | Urdu |

| v. | verb |

| Vr. | Verbal root |

- DH EN

- Home މައި ސަފްހާ

- About އަޅުގަނޑުމެން

- Service Charter ހިދުމަތުގެ ޗާޓަރ

- Certifying Statement ސަޓިފައިން ސްޓޭޓްމަންޓް

- Amendments އެމެންޑްމެންޓް

- Endorsement އެންޑޯޒްމަންޓް

- Translation ތަރުޖަމާކުރުން

- Recheck ރީޗެކްކުރުން

- IGCSE / GCE O’ Level Exam އައި.ޖީ.ސީ.އެސް.އީ / ޖީ.ސީ.އީ އޯލެވެލް އިމްތިޙާނު

- SSC Exams އެސް.އެސް.ސީ އިމްތިޙާނު

- Edexcel A ‘level Exams އެޑެކްސެލް އޭލެވެލް އިމްތިޙާނު

- HSC Exams އެޗް.އެސް.ސީ އިމްތިޙާނު

- Cambridge English Exam ކެމްބްރިޖް އިންގްލިޝް އިމްތިޙާނު

- On Demand Exams އޮންޑިމާންޑް އިމްތިޙާނު

- All Downloads ޑައުންލޯޑްސް

- Past Papers ޕާސްޕޭޕަރު

- Gallery ގެލެރީ

- Contacts ގުޅުއްވުމަށް

Department of Public Examinations

ޑިޕާޓްމަންޓް އޮފް ޕަބްލިކް އެގްޒޭމިނޭޝަންސް.

- Login ލޮގިން

- EN DH

Past Papers

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Arabic Paper އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ | |

| SSC Arabic Paper_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 (October) އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު) | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 (October) އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު) | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 (May) އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 (މެއި) | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 (May) އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 (މެއި) | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 (October) އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު) | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 (May) އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 (މެއި) | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 (May)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 (މެއި)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 (October)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 (October)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 (May)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 (މެއި)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 (May)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 (މެއި)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 (October)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 (May)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 (މެއި)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 (October)_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު)_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 (May) އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 (މެއި) | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 (October) އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 (އޮކްޓޫބަރު) | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Arabic Paper އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ | |

| SSC Arabic Paper_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Specimen Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ސްޕެސިމެން ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Specimen Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ސްޕެސިމެން ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Arabic Paper އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ | |

| SSC Arabic Paper_ Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ އަރަބި ޕޭޕަރ_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2 އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| HSC Islam Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެޗްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 1_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 1_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Dhivehi Paper 2_Marking Scheme އެސްއެސްސީ ދިވެހި ޕޭޕަރ 2_މާކިންގ ސްކީމް | |

| SSC Islam Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Specimen Paper 1 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ސްޕެސިމެން ޕޭޕަރ 1 | |

| SSC Islam Paper 2 އެސްއެސްސީ އިސްލާމް ޕޭޕަރ 2 | |