Home » Education » Difference Between Conceptual and Empirical Research

Difference Between Conceptual and Empirical Research

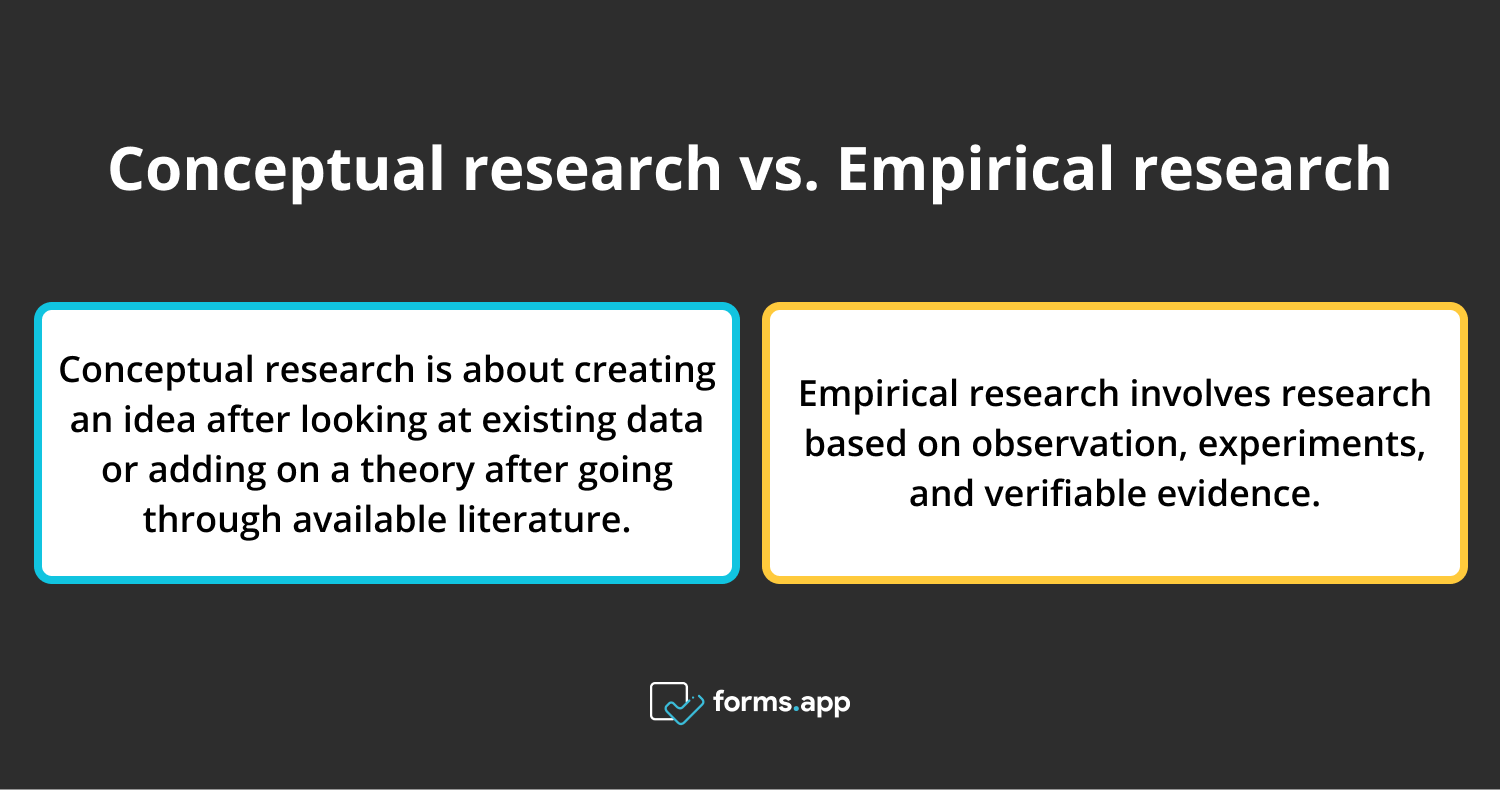

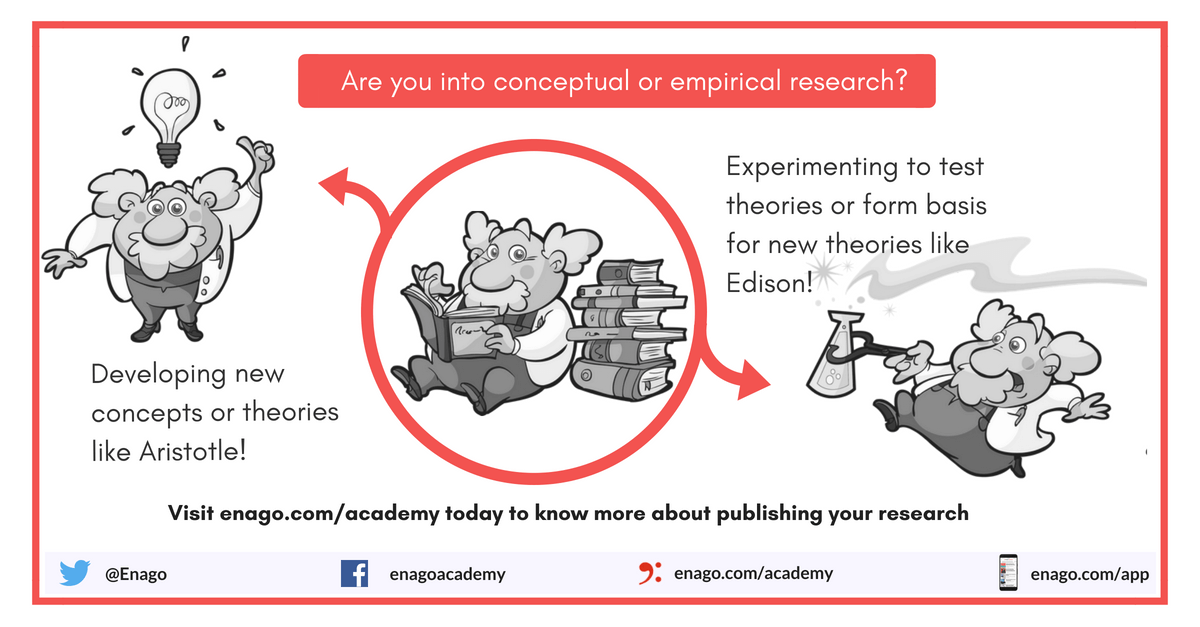

The main difference between conceptual and empirical research is that conceptual research involves abstract ideas and concepts, whereas empirical research involves research based on observation, experiments and verifiable evidence.

Conceptual research and empirical research are two ways of doing scientific research. These are two opposing types of research frameworks since conceptual research doesn’t involve any experiments and empirical research does.

Key Areas Covered

1. What is Empirical Research – Definition, Characteristics, Uses 2. What is Empirical Research – Definition, Characteristics, Uses 3. What is the Difference Between Conceptual and Empirical Research – Comparison of Key Differences

Conceptual Research, Empirical Research, Research

What is Conceptual Research?

Conceptual research is a type of research that is generally related to abstract ideas or concepts. It doesn’t particularly involve any practical experimentation. However, this type of research typically involves observing and analyzing information already present on a given topic. Philosophical research is a generally good example for conceptual research.

Conceptual research can be used to solve real-world problems. Conceptual frameworks, which are analytical tools researchers use in their studies, are based on conceptual research. Furthermore, these frameworks help to make conceptual distinctions and organize ideas researchers need for research purposes.

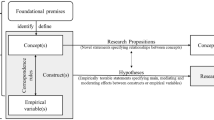

Figure 2: Conceptual Framework

In simple words, a conceptual framework is the researcher’s synthesis of the literature (previous research studies) on how to explain a particular phenomenon. It explains the actions required in the course of the study based on the researcher’s observations on the subject of research as well as the knowledge gathered from previous studies.

What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is basically a research that uses empirical evidence. Empirical evidence refers to evidence verifiable by observation or experience rather than theory or pure logic. Thus, empirical research is research studies with conclusions based on empirical evidence. Moreover, empirical research studies are observable and measurable.

Empirical evidence can be gathered through qualitative research studies or quantitative research studies . Qualitative research methods gather non-numerical or non-statistical data. Thus, this type of studies helps to understand the underlying reasons, opinions, and motivations behind something as well as to uncover trends in thought and opinions. Quantitative research studies, on the other hand, gather statistical data. These have the ability to quantify behaviours, opinions, or other defined variables. Moreover, a researcher can even use a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to find answers to his research questions .

Figure 2: Empirical Research Cycle

A.D. de Groot, a famous psychologist, came up with a cycle (figure 2) to explain the process of the empirical research process. Moreover, this cycle has five steps, each as important as the other. These steps include observation, induction, deduction, testing and evaluation.

Conceptual research is a type of research that is generally related to abstract ideas or concepts whereas empirical research is any research study where conclusions of the study are drawn from evidence verifiable by observation or experience rather than theory or pure logic.

Conceptual research involves abstract idea and concepts; however, it doesn’t involve any practical experiments. Empirical research, on the other hand, involves phenomena that are observable and measurable.

Type of Studies

Philosophical research studies are examples of conceptual research studies, whereas empirical research includes both quantitative and qualitative studies.

The main difference between conceptual and empirical research is that conceptual research involves abstract ideas and concepts whereas empirical research involves research based on observation, experiments and verifiable evidence.

1.“Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples.” QuestionPro, 14 Dec. 2018, Available here . 2. “Empirical Research.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 15 Sept. 2019, Available here . 3.“Conceptual Research: Definition, Framework, Example and Advantages.” QuestionPro, 18 Sept. 2018, Available here. 4. Patrick. “Conceptual Framework: A Step-by-Step Guide on How to Make One.” SimplyEducate.Me, 4 Dec. 2018, Available here .

Image Courtesy:

1. “APM Conceptual Framework” By LarryDragich – Created for a Technical Management Counsel meeting Previously published: First published in APM Digest in March (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Commons Wikimedia 2. “Empirical Cycle” By Empirical_Cycle.png: TesseUndDaanderivative work: Beao (talk) – Empirical_Cycle.png (CC BY 3.0) via Commons Wikimedia

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Conceptual Research vs. Empirical Research

What's the difference.

Conceptual research and empirical research are two distinct approaches to conducting research. Conceptual research focuses on exploring and developing theories, concepts, and ideas. It involves analyzing existing literature, theories, and concepts to gain a deeper understanding of a particular topic. Conceptual research is often used in the early stages of research to generate hypotheses and develop a theoretical framework. On the other hand, empirical research involves collecting and analyzing data to test hypotheses and answer research questions. It relies on observation, measurement, and experimentation to gather evidence and draw conclusions. Empirical research is more focused on obtaining concrete and measurable results, often through surveys, experiments, or observations. Both approaches are valuable in research, with conceptual research providing a foundation for empirical research and empirical research validating or refuting conceptual theories.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research is a fundamental aspect of any field of study, providing a systematic approach to acquiring knowledge and understanding. In the realm of research, two primary methodologies are commonly employed: conceptual research and empirical research. While both approaches aim to contribute to the body of knowledge, they differ significantly in their attributes, methodologies, and outcomes. This article aims to explore and compare the attributes of conceptual research and empirical research, shedding light on their unique characteristics and applications.

Conceptual Research

Conceptual research, also known as theoretical research, focuses on the exploration and development of theories, concepts, and ideas. It is primarily concerned with abstract and hypothetical constructs, aiming to enhance understanding and generate new insights. Conceptual research often involves a comprehensive review of existing literature, analyzing and synthesizing various theories and concepts to propose new frameworks or models.

One of the key attributes of conceptual research is its reliance on deductive reasoning. Researchers start with a set of existing theories or concepts and use logical reasoning to derive new hypotheses or frameworks. This deductive approach allows researchers to build upon existing knowledge and propose innovative ideas. Conceptual research is often exploratory in nature, seeking to expand the boundaries of knowledge and provide a foundation for further empirical investigations.

Conceptual research is particularly valuable in fields where empirical data may be limited or difficult to obtain. It allows researchers to explore complex phenomena, develop theoretical frameworks, and generate hypotheses that can later be tested through empirical research. By focusing on abstract concepts and theories, conceptual research provides a theoretical foundation for empirical investigations, guiding researchers in their quest for empirical evidence.

Furthermore, conceptual research plays a crucial role in the development of new disciplines or interdisciplinary fields. It helps establish a common language and theoretical framework, facilitating communication and collaboration among researchers from different backgrounds. By synthesizing existing knowledge and proposing new concepts, conceptual research lays the groundwork for empirical studies and contributes to the overall advancement of knowledge.

Empirical Research

Empirical research, in contrast to conceptual research, is concerned with the collection and analysis of observable data. It aims to test hypotheses, validate theories, and provide evidence-based conclusions. Empirical research relies on the systematic collection of data through various methods, such as surveys, experiments, observations, or interviews. The data collected is then analyzed using statistical or qualitative techniques to draw meaningful conclusions.

One of the primary attributes of empirical research is its inductive reasoning approach. Researchers start with specific observations or data and use them to develop general theories or conclusions. This inductive approach allows researchers to derive broader implications from specific instances, providing a basis for generalization. Empirical research is often hypothesis-driven, seeking to test and validate theories or hypotheses through the collection and analysis of data.

Empirical research is highly valued for its ability to provide concrete evidence and support or refute existing theories. It allows researchers to investigate real-world phenomena, understand cause-and-effect relationships, and make informed decisions based on empirical evidence. By relying on observable data, empirical research enhances the credibility and reliability of research findings, contributing to the overall body of knowledge in a field.

Moreover, empirical research is particularly useful in applied fields, where practical implications and real-world applications are of utmost importance. It allows researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, assess the impact of policies, or measure the outcomes of specific actions. Empirical research provides valuable insights that can inform decision-making processes, guide policy development, and drive evidence-based practices.

Comparing Conceptual Research and Empirical Research

While conceptual research and empirical research differ in their methodologies and approaches, they are both essential components of the research process. Conceptual research focuses on the development of theories and concepts, providing a theoretical foundation for empirical investigations. Empirical research, on the other hand, relies on the collection and analysis of observable data to test and validate theories.

Conceptual research is often exploratory and aims to expand the boundaries of knowledge. It is valuable in fields where empirical data may be limited or difficult to obtain. By synthesizing existing theories and proposing new frameworks, conceptual research provides a theoretical basis for empirical studies. It helps researchers develop hypotheses and guides their quest for empirical evidence.

Empirical research, on the other hand, is hypothesis-driven and seeks to provide concrete evidence and support or refute existing theories. It allows researchers to investigate real-world phenomena, understand cause-and-effect relationships, and make informed decisions based on empirical evidence. Empirical research is particularly useful in applied fields, where practical implications and real-world applications are of utmost importance.

Despite their differences, conceptual research and empirical research are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they often complement each other in the research process. Conceptual research provides the theoretical foundation and guidance for empirical investigations, while empirical research validates and refines existing theories or concepts. The iterative nature of research often involves a continuous cycle of conceptual and empirical research, with each informing and influencing the other.

Both conceptual research and empirical research contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields. Conceptual research expands theoretical frameworks, proposes new concepts, and lays the groundwork for empirical investigations. Empirical research, on the other hand, provides concrete evidence, validates theories, and informs practical applications. Together, they form a symbiotic relationship, driving progress and innovation in various disciplines.

Conceptual research and empirical research are two distinct methodologies employed in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding. While conceptual research focuses on the development of theories and concepts, empirical research relies on the collection and analysis of observable data. Both approaches have their unique attributes, methodologies, and applications.

Conceptual research plays a crucial role in expanding theoretical frameworks, proposing new concepts, and providing a foundation for empirical investigations. It is particularly valuable in fields where empirical data may be limited or difficult to obtain. On the other hand, empirical research provides concrete evidence, validates theories, and informs practical applications. It is highly valued in applied fields, where evidence-based decision-making is essential.

Despite their differences, conceptual research and empirical research are not mutually exclusive. They often work in tandem, with conceptual research guiding the development of hypotheses and theoretical frameworks, and empirical research validating and refining these theories through the collection and analysis of data. Together, they contribute to the overall advancement of knowledge and understanding in various disciplines.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Yearly paid plans are up to 65% off for the spring sale. Limited time only! 🌸

- Form Builder

- Survey Maker

- AI Form Generator

- AI Survey Tool

- AI Quiz Maker

- Store Builder

- WordPress Plugin

HubSpot CRM

Google Sheets

Google Analytics

Microsoft Excel

- Popular Forms

- Job Application Form Template

- Rental Application Form Template

- Hotel Accommodation Form Template

- Online Registration Form Template

- Employment Application Form Template

- Application Forms

- Booking Forms

- Consent Forms

- Contact Forms

- Donation Forms

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Satisfaction Surveys

- Evaluation Surveys

- Feedback Surveys

- Market Research Surveys

- Personality Quiz Template

- Geography Quiz Template

- Math Quiz Template

- Science Quiz Template

- Vocabulary Quiz Template

Try without registration Quick Start

Read engaging stories, how-to guides, learn about forms.app features.

Inspirational ready-to-use templates for getting started fast and powerful.

Spot-on guides on how to use forms.app and make the most out of it.

See the technical measures we take and learn how we keep your data safe and secure.

- Integrations

- Help Center

- Sign In Sign Up Free

- What is conceptual research: Definition & examples

Defne Çobanoğlu

How did Newton figure out the gravity after seeing an apple fall from a tree? What kind of research did Nicolaus Copernicus conduct to figure out that the planets revolve around the sun and not vice versa? It is certain that they did not conduct practical experiments to figure this stuff out.

The type of research these two scientists do is called conceptual research. They basically observed their surroundings to conceptualize and develop theories about gravitation, motion, and astronomy. That is what some scientists and philosophers do to wrap their heads around existing concepts and new ideas. Now, let us see what exactly conceptual research is and other details.

- What is conceptual research?

Conceptual research is a type of research that does not involve conducting any practical experiments . It is based on observing and analyzing already existing concepts and theories. The researcher can observe their surroundings and develop brand-new theories, or they can build on existing ones.

Conceptual research is widely used in the study of philosophy to develop new ideas. And this type of research is also used to answer business questions and organize ideas, or interpret existing theories differently.

Conceptual research definition

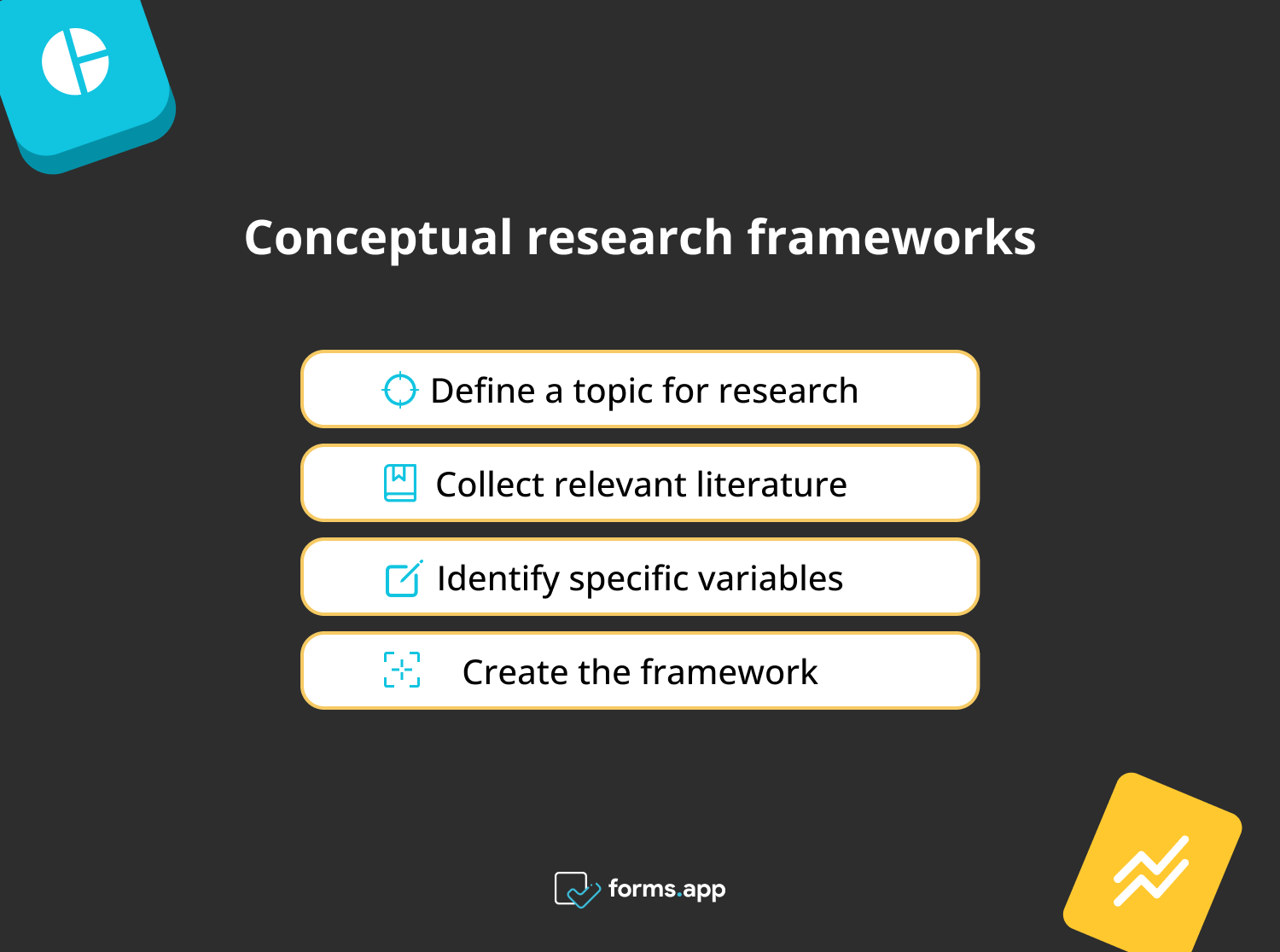

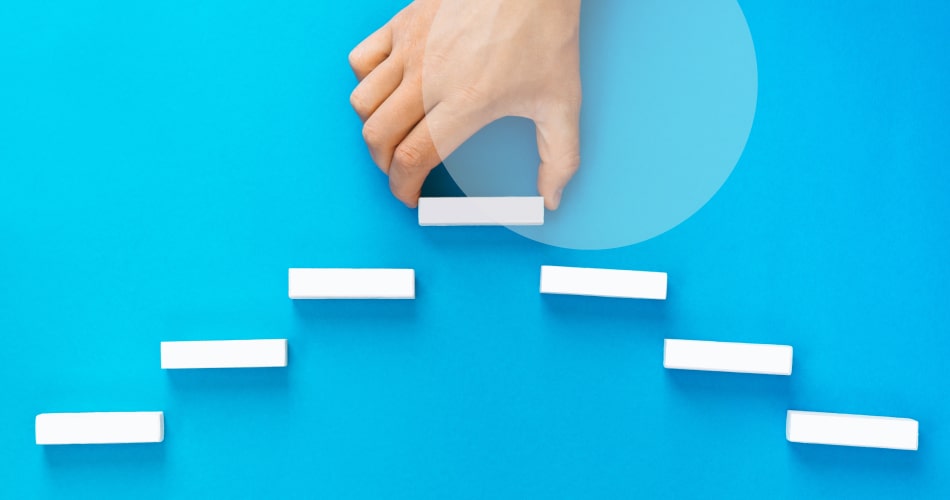

- Conceptual research frameworks

Even if the researcher is not conducting any experiments of their own, they should still work in a systematic manner, to be precise. And a conceptual research framework is built around existing literature and appropriate research studies that can explain the phenomenon. Here is a step-by-step guide to creating a conceptual research framework:

The steps for a conceptual research framework

1 - Define a topic for research:

The first step in creating your research framework is to choose the topic you will be working on. Most researchers define a topic in their area of expertise and go along with it.

2 - Collect relevant literature:

After deciding on the subject, the next and most important step is collecting relevant literature. As this type of research heavily relies on existing literature, it is important to find reliable sources. Successfully collecting relevant information is key to successfully completing this step. The reliable sources one can use are:

- scientific journals

- research papers (published by well-known scientists)

- Public libraries

- Online databases

- Relevant books

3 - Identify specific variables:

In this step, identify specific variables that may affect your research. These variables may give your study a new scope and a new area to cover during your research. For example, let us say you want to conduct research about the occurrence of depression in teenage boys aged 14 to 19. Here, the two variables are teenage boys and depression.

During your research, you figure that substance abuse among teenage boys has a big effect on their mental wellbeings. Therefore, you add substance abuse as a relevant variable and be mindful of that when you are continuing your research.

4 - Create the framework:

The final step is creating the framework after going through all the relevant data available. The research question in hand becomes the research framework

- Conceptual research examples

When a researcher decides on the subject they want to explore, the next thing they should decide is what kind of methods they want to do. They can choose the experiments and surveys, but sometimes these methods are not possible for different reasons. And when they can not do practical experimenting, they can use existing literature and observation. Here are two examples where conceptual research can be used:

- Example 1 of conceptual research:

A researcher wants to explore the key factors that influence consumer behavior in the online shopping environment. That is their research question. Once the researcher decides on the subject, they can begin by reviewing the existing literature on consumer behavior and examining different theories and models of consumer behavior.

Then, they can identify common themes or factors that have emerged. By understanding this phenomenon, the researcher can develop a conceptual framework.

- Example 2 of conceptual research:

A group of researchers wants to see if there is any correlation between chemically dyeing your hair and the risk of cancer in women. They can start collecting data on women that had cancer and usage of hair dye. They can collect research papers on this particular subject. And they can create a conceptual framework with the information they collected and analyzed.

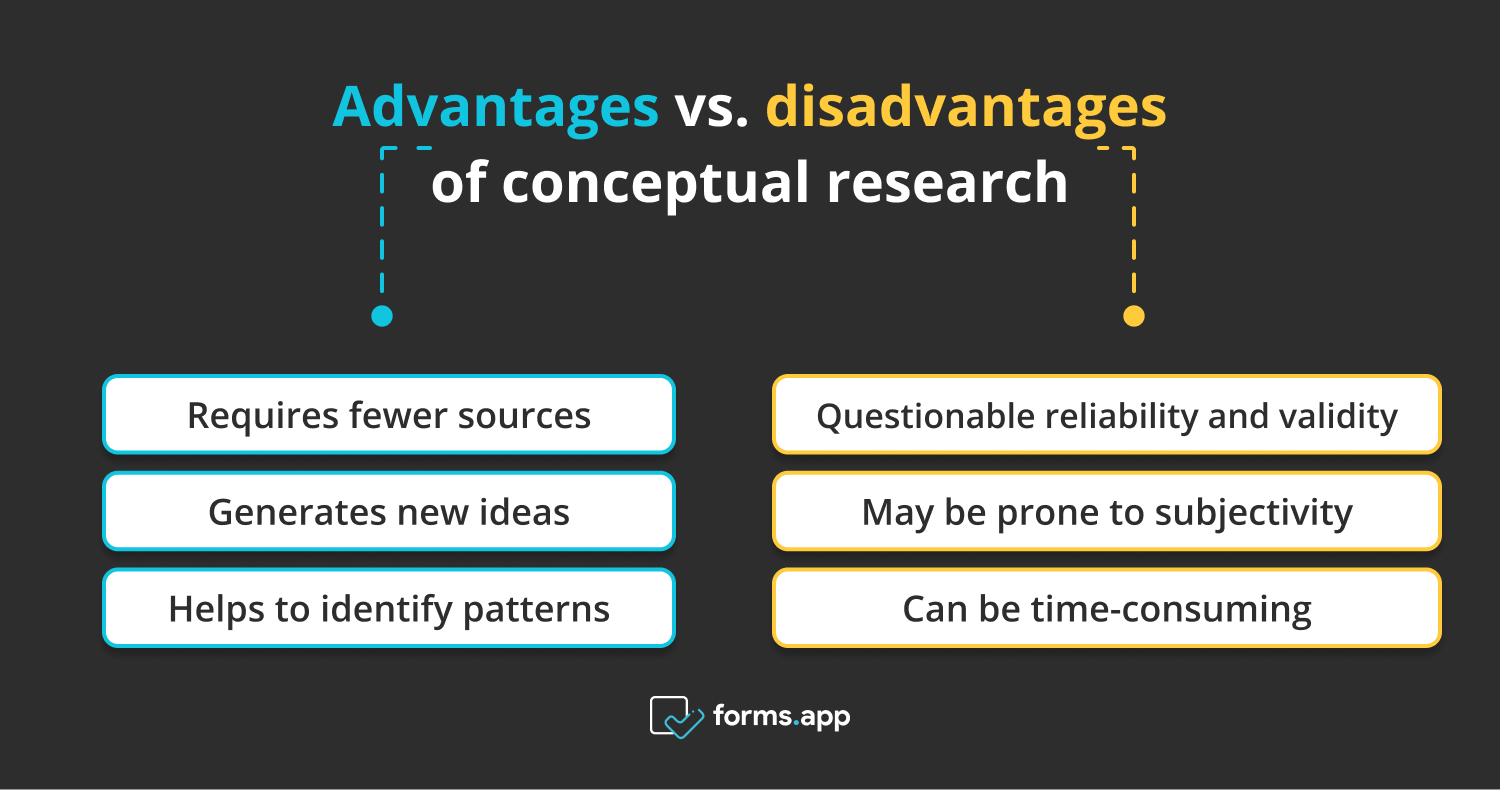

- Advantages and disadvantages of conceptual research

There are multiple research types for researchers to get to the goal they want, and they all offer different advantages. It is up to the researchers to decide on the most suitable one for their study and go along with that. The conceptual study also has its positive and negative aspects one should have in mind. Now, let us go through the list of conceptual research advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages vs. disadvantages of conceptual research

Advantages of conceptual research:

- Requires fewer sources: This type of research does not involve any type of experiment. Therefore it saves money, energy, and manpower. It only involves theorizing and searching through existing literature.

- Generates new ideas: Conceptual research can help generate new ideas and hypotheses. Researchers can use data collection to add on top of abstract ideas or concepts

- Helps to identify patterns: Conceptual research can help identify patterns in complex concepts and help develop a conceptual analysis. This can lead to a better understanding of how different factors are related to each other.

Disadvantages of conceptual research:

- Questionable reliability and validity: Conclusions drawn from literature reviews on conceptual research topics are less fact-based and may not essentially be considered dependable. Because they are not backed up by practical experimentation, they may have less credibility.

- May be prone to subjectivity: Because it relies on abstract concepts, conceptual research may be influenced by personal biases and perspectives. Researchers should be mindful of this effect and act on it accordingly.

- Can be time-consuming: As conceptual research involves extensive research and analyses of relevant literature, it may take a longer time to finalize the study on hand. This can be challenging for researchers who are working within time constraints.

- Conceptual research vs. empirical research

Conceptual research is about creating an idea after looking at existing data or adding on a theory after going through available literature. And the empirical research includes something different than the prior one. Empirical research involves research based on observation, experiments, and verifiable evidence .

The main difference between the two is the fact that empirical research involves doing experiments to develop a conceptual framework. Empirical research studies are observable and measurable as they are verifiable by observations or experience. In order to see if a study is empirical, you can ask yourself this question: Can I create this study and test these results myself?

The difference between conceptual research and empirical research

- Wrapping it up

Once you encounter a problem you want to solve but you are unable to do experiments, you can go with conceptual research. Instead of conducting experiments, you should find appropriate existing literature and analyze them thoroughly. Just then, you can create a conceptual framework.

And you can always use the help of a good online tool for your needs when doing research. The best tool for all your needs, from forms to surveys to questionnaires, is forms.app. forms.app is an online survey maker that offers more than 1000 ready-to-use templates and can be the help you need!

Defne is a content writer at forms.app. She is also a translator specializing in literary translation. Defne loves reading, writing, and translating professionally and as a hobby. Her expertise lies in survey research, research methodologies, content writing, and translation.

- Form Features

- Data Collection

Table of Contents

Related posts.

Paperform vs. Jotform: which one is better?

8 awesome tips: How to get more form submissions

7 great form types you can use for your business

forms.app Team

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Conceptual Research: Definition, Framework, Example and Advantages

Conceptual Research: Definition

Conceptual research is defined as a methodology wherein research is conducted by observing and analyzing already present information on a given topic. Conceptual research doesn’t involve conducting any practical experiments. It is related to abstract concepts or ideas. Philosophers have long used conceptual research to develop new theories or interpret existing theories in a different light.

For example, Copernicus used conceptual research to come up with the concepts of stellar constellations based on his observations of the universe. Down the line, Galileo simplified Copernicus’s research by making his own conceptual observations which gave rise to more experimental research and confirmed the predictions made at that time.

The most famous example of conceptual research is Sir Issac Newton. He observed his surroundings to conceptualize and develop theories about gravitation and motion.

Einstein is widely known and appreciated for his work on conceptual research. Although his theories were based on conceptual observations, Einstein also proposed experiments to come up with theories to test the conceptual research.

Nowadays, conceptual research is used to answer business questions and solve real-world problems. Researchers use analytical research tools called conceptual frameworks to make conceptual distinctions and organize ideas required for research purposes.

Conceptual Research Framework

Conceptual research framework constitutes of a researcher’s combination of previous research and associated work and explains the occurring phenomenon. It systematically explains the actions needed in the course of the research study based on the knowledge obtained from other ongoing research and other researchers’ points of view on the subject matter.

Here is a stepwise guide on how to create the conceptual research framework:

01. Choose the topic for research

Before you start working on collecting any research material, you should have decided on your topic for research. It is important that the topic is selected beforehand and should be within your field of specialization.

02. Collect relevant literature

Once you have narrowed down a topic, it is time to collect relevant information about it. This is an important step, and much of your research is dependent on this particular step, as conceptual research is mostly based on information obtained from previous research. Here collecting relevant literature and information is the key to successfully completing research.

The material that you should preferably use is scientific journals , research papers published by well-known scientists , and similar material. There is a lot of information available on the internet and in public libraries as well. All the information that you find on the internet may not be relevant or true. So before you use the information, make sure you verify it.

03. Identify specific variables

Identify the specific variables that are related to the research study you want to conduct. These variables can give your research a new scope and can also help you identify how these can be related to your research design . For example, consider hypothetically you want to conduct research about the occurrence of cancer in married women. Here the two variables that you will be concentrating on are married women and cancer.

While collecting relevant literature, you understand that the spread of cancer is more aggressive in married women who are beyond 40 years of age. Here there is a third variable which is age, and this is a relevant variable that can affect the end result of your research.

04. Generate the framework

In this step, you start building the required framework using the mix of variables from the scientific articles and other relevant materials. The research problem statement in your research becomes the research framework. Your attempt to start answering the question becomes the basis of your research study. The study is carried out to reduce the knowledge gap and make available more relevant and correct information.

Example of Conceptual Research Framework

Thesis statement/ Purpose of research: Chronic exposure to sunlight can lead to precancerous (actinic keratosis), cancerous (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma), and even skin lesions (caused by loss of skin’s immune function) in women over 40 years of age.

The study claims that constant exposure to sunlight can cause the precancerous condition and can eventually lead to cancer and other skin abnormalities. Those affected by these experience symptoms like fatigue, fine or coarse wrinkles, discoloration of the skin, freckles, and a burning sensation in the more exposed areas.

Note that in this study, there are two variables associated- cancer and women over 40 years in the African subcontinent. But one is a dependent variable (women over 40 years, in the African subcontinent), and the other is an independent variable (cancer). Cumulative exposure to the sun till the age of 18 years can lead to symptoms similar to skin cancer. If this is not taken care of, there are chances that cancer can spread entirely.

Assuming that the other factors are constant during the research period, it will be possible to correlate the two variables and thus confirm that, indeed, chronic exposure to sunlight causes cancer in women over the age of 40 in the African subcontinent. Further, correlational research can verify this association further.

Advantages of Conceptual Research

1. Conceptual research mainly focuses on the concept of the research or the theory that explains a phenomenon. What causes the phenomenon, what are its building blocks, and so on? It’s research based on pen and paper.

2. This type of research heavily relies on previously conducted studies; no form of experiment is conducted, which saves time, effort, and resources. More relevant information can be generated by conducting conceptual research.

3. Conceptual research is considered the most convenient form of research. In this type of research, if the conceptual framework is ready, only relevant information and literature need to be sorted.

QuestionPro for Conceptual Research

QuestionPro offers readily available conceptual frameworks. These frameworks can be used to research consumer trust, customer satisfaction (CSAT) , product evaluations, etc. You can select from a wide range of templates question types, and examples curated by expert researchers.

We also help you decide which conceptual framework might be best suited for your specific situation.

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 17 UX Research Software for UX Design in 2024

Apr 5, 2024

Healthcare Staff Burnout: What it Is + How To Manage It

Apr 4, 2024

Top 15 Employee Retention Software in 2024

Top 10 Employee Development Software for Talent Growth

Apr 3, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Empirical Vs. Conceptual Research

According to ORI, research is defined as the process of discovering new knowledge. Using observations and scientific methods, researchers arrive at a hypothesis, test that hypothesis, and make a conclusion based on the key findings. Scientific research can be divided into empirical and conceptual research. However, modern science combines techniques from both types of research.

To know the difference between empirical and conceptual research, click here .

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Top 4 Tools for Keyword Selection

Keywords play an important role in making research discoverable. It helps researchers discover articles relevant…

Top 4 Tools to Create Scientific Images and Figures

A good image or figure can go a long way in effectively communicating your results…

Tips to Effectively Present Your Work

Presenting your work is an important part of scientific communication and is very important for…

Tips to Tackle Procrastination

You can end up wasting a lot of time procrastinating. Procrastination leads you to a…

Rules of Capitalization

Using too much capitalization or using it incorrectly can undermine, clutter, and confuse your writing…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Theoretical vs Conceptual Framework

What they are & how they’re different (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, sooner or later you’re bound to run into the terms theoretical framework and conceptual framework . These are closely related but distinctly different things (despite some people using them interchangeably) and it’s important to understand what each means. In this post, we’ll unpack both theoretical and conceptual frameworks in plain language along with practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Theoretical vs Conceptual

What is a theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, what is a conceptual framework, example of a conceptual framework.

- Theoretical vs conceptual: which one should I use?

A theoretical framework (also sometimes referred to as a foundation of theory) is essentially a set of concepts, definitions, and propositions that together form a structured, comprehensive view of a specific phenomenon.

In other words, a theoretical framework is a collection of existing theories, models and frameworks that provides a foundation of core knowledge – a “lay of the land”, so to speak, from which you can build a research study. For this reason, it’s usually presented fairly early within the literature review section of a dissertation, thesis or research paper .

Let’s look at an example to make the theoretical framework a little more tangible.

If your research aims involve understanding what factors contributed toward people trusting investment brokers, you’d need to first lay down some theory so that it’s crystal clear what exactly you mean by this. For example, you would need to define what you mean by “trust”, as there are many potential definitions of this concept. The same would be true for any other constructs or variables of interest.

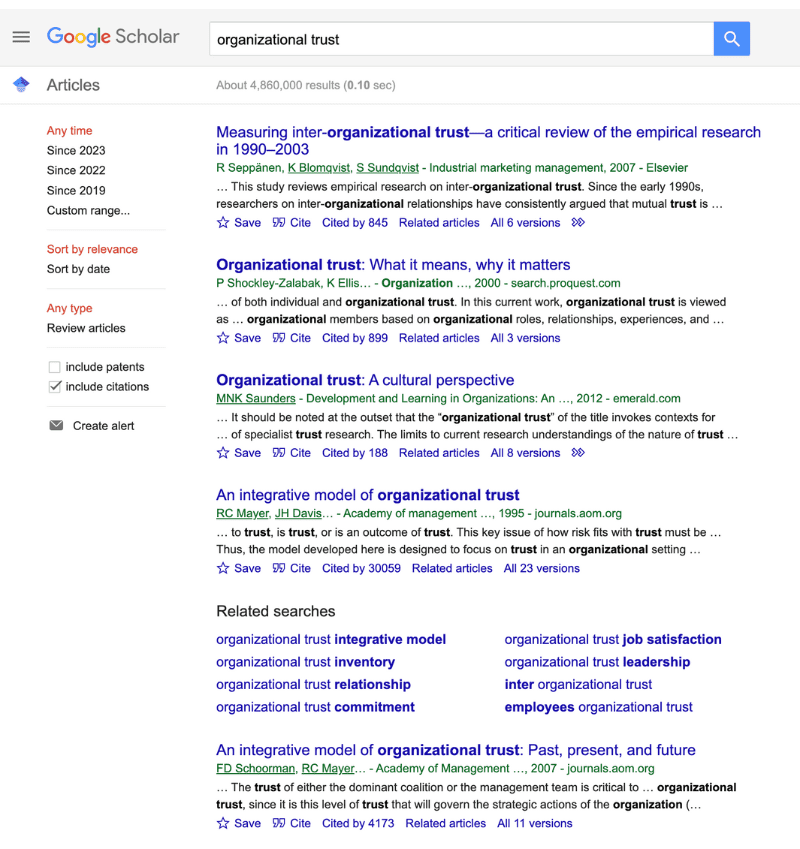

You’d also need to identify what existing theories have to say in relation to your research aim. In this case, you could discuss some of the key literature in relation to organisational trust. A quick search on Google Scholar using some well-considered keywords generally provides a good starting point.

Typically, you’ll present your theoretical framework in written form , although sometimes it will make sense to utilise some visuals to show how different theories relate to each other. Your theoretical framework may revolve around just one major theory , or it could comprise a collection of different interrelated theories and models. In some cases, there will be a lot to cover and in some cases, not. Regardless of size, the theoretical framework is a critical ingredient in any study.

Simply put, the theoretical framework is the core foundation of theory that you’ll build your research upon. As we’ve mentioned many times on the blog, good research is developed by standing on the shoulders of giants . It’s extremely unlikely that your research topic will be completely novel and that there’ll be absolutely no existing theory that relates to it. If that’s the case, the most likely explanation is that you just haven’t reviewed enough literature yet! So, make sure that you take the time to review and digest the seminal sources.

Need a helping hand?

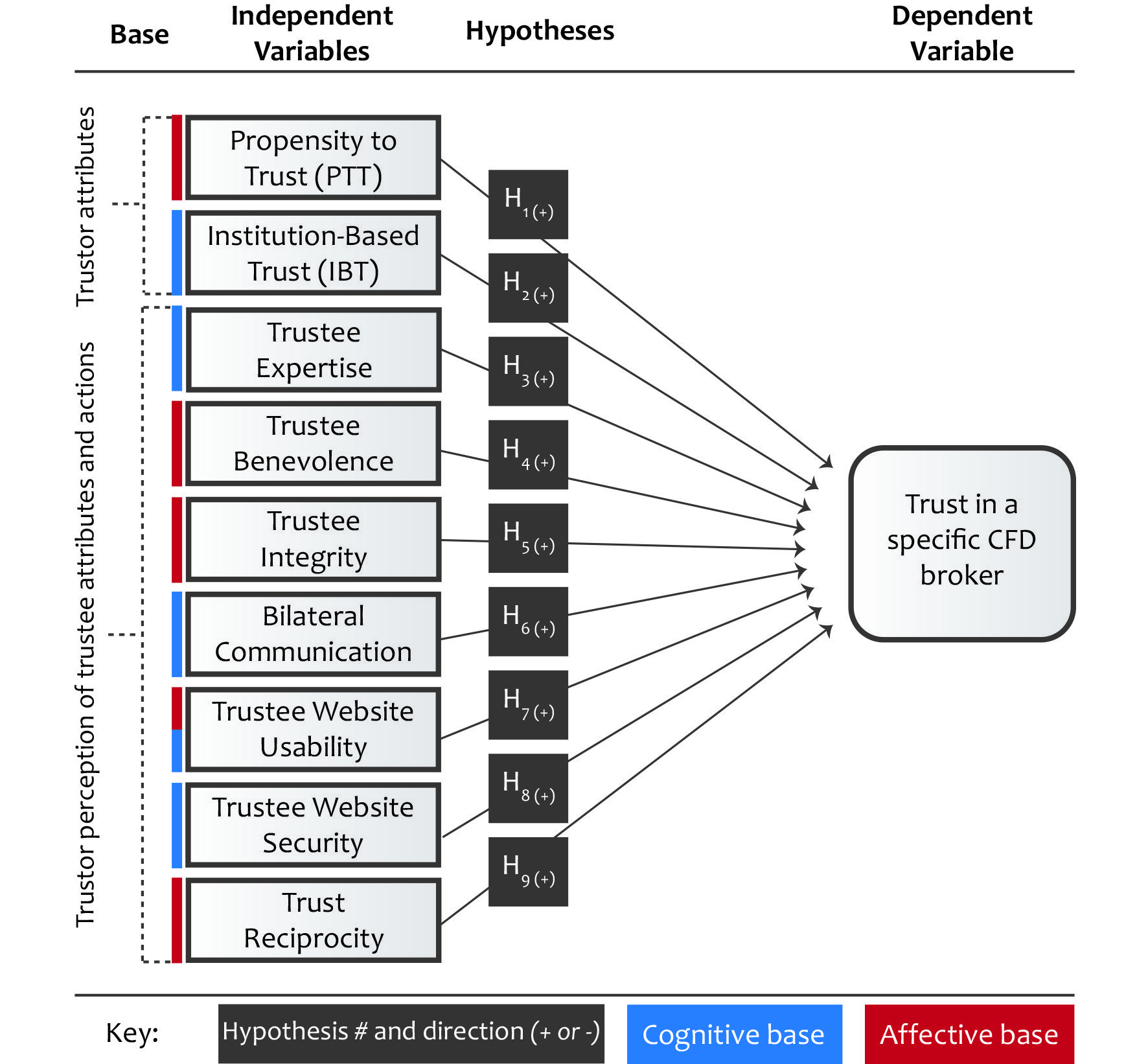

A conceptual framework is typically a visual representation (although it can also be written out) of the expected relationships and connections between various concepts, constructs or variables. In other words, a conceptual framework visualises how the researcher views and organises the various concepts and variables within their study. This is typically based on aspects drawn from the theoretical framework, so there is a relationship between the two.

Quite commonly, conceptual frameworks are used to visualise the potential causal relationships and pathways that the researcher expects to find, based on their understanding of both the theoretical literature and the existing empirical research . Therefore, the conceptual framework is often used to develop research questions and hypotheses .

Let’s look at an example of a conceptual framework to make it a little more tangible. You’ll notice that in this specific conceptual framework, the hypotheses are integrated into the visual, helping to connect the rest of the document to the framework.

As you can see, conceptual frameworks often make use of different shapes , lines and arrows to visualise the connections and relationships between different components and/or variables. Ultimately, the conceptual framework provides an opportunity for you to make explicit your understanding of how everything is connected . So, be sure to make use of all the visual aids you can – clean design, well-considered colours and concise text are your friends.

Theoretical framework vs conceptual framework

As you can see, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are closely related concepts, but they differ in terms of focus and purpose. The theoretical framework is used to lay down a foundation of theory on which your study will be built, whereas the conceptual framework visualises what you anticipate the relationships between concepts, constructs and variables may be, based on your understanding of the existing literature and the specific context and focus of your research. In other words, they’re different tools for different jobs , but they’re neighbours in the toolbox.

Naturally, the theoretical framework and the conceptual framework are not mutually exclusive . In fact, it’s quite likely that you’ll include both in your dissertation or thesis, especially if your research aims involve investigating relationships between variables. Of course, every research project is different and universities differ in terms of their expectations for dissertations and theses, so it’s always a good idea to have a look at past projects to get a feel for what the norms and expectations are at your specific institution.

Want to learn more about research terminology, methods and techniques? Be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help, have a look at our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research process, step by step.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

17 Comments

Thank you for giving a valuable lesson

good thanks!

VERY INSIGHTFUL

thanks for given very interested understand about both theoritical and conceptual framework

I am researching teacher beliefs about inclusive education but not using a theoretical framework just conceptual frame using teacher beliefs, inclusive education and inclusive practices as my concepts

good, fantastic

great! thanks for the clarification. I am planning to use both for my implementation evaluation of EmONC service at primary health care facility level. its theoretical foundation rooted from the principles of implementation science.

This is a good one…now have a better understanding of Theoretical and Conceptual frameworks. Highly grateful

Very educating and fantastic,good to be part of you guys,I appreciate your enlightened concern.

Thanks for shedding light on these two t opics. Much clearer in my head now.

Simple and clear!

The differences between the two topics was well explained, thank you very much!

Thank you great insight

Superb. Thank you so much.

Hello Gradcoach! I’m excited with your fantastic educational videos which mainly focused on all over research process. I’m a student, I kindly ask and need your support. So, if it’s possible please send me the PDF format of all topic provided here, I put my email below, thank you!

I am really grateful I found this website. This is very helpful for an MPA student like myself.

I’m clear with these two terminologies now. Useful information. I appreciate it. Thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Howe Writing Center

Distinguishing between the conceptual versus the empirical.

Philosophical questions tend to be conceptual in nature. This means that they cannot be answered simply by giving facts or information. A concept is the object of a thought, not something that is present to the senses.

The word “empirical” means “gained through experience.” Scientific experiments and observation give rise to empirical data. Scientific theories that organize the data are conceptual. Historical records or results of sociological or psychological surveys are empirical. Making sense of those records or results requires the use of concepts.

Concepts are not mysterious, and although they are "abstract," we use them all the time to organize our thinking. We literally could not think or communicate without concepts. Some common examples of concepts are "justice," "beauty," and "truth," but also "seven," "blue," or "big."

Empirical questions can be answered by giving facts or information. Examples of empirical questions are: "What is the chemical composition of water?" or: "When did the French Revolution happen?" or: "Which educational system results in the highest literacy rate?”

When we ask a philosophical conceptual question, we are usually inquiring into the nature of something, or asking a question about how something is the way it is. Ancient philosophers such as Plato asked conceptual questions such as "What is justice?" as the basis of philosophy. The statements, "That action is wrong," or, "Knowledge is justified true belief," are conceptual claims.

In papers, you will often be asked to consider concepts, to analyze and unpack the way in which philosophers use them, and perhaps to compare them across texts. For example, you might be asked, “Do animals have rights?” This question asks you to consider what a right is, and whether it is the sort of thing an animal ought to or even could have. It does not ask whether or not there are laws on the books that actually give these rights. It also does not ask for your opinion on this question, but for a reasoned position that draws on philosophical concepts and texts for support.

- Conduct , Resources

Conceptual Research Vs Empirical Research?

Melissa martinez.

Need equipment for your lab?

Conceptual Research

Conceptual research is a technique wherein investigation is conducted by watching and analyzing already present data on a given point. Conceptual research does not include any viable tests. It is related to unique concepts or thoughts. Philosophers have long utilized conceptual research to create modern speculations or decipher existing hypotheses in a diverse light.

It doesn’t include viable experimentation, but the instep depends on analyzing accessible data on a given theme. Conceptual research has been broadly utilized within logic to create modern hypotheses, counter existing speculations, or distinctively decipher existing hypotheses.

Today, conceptual research is utilized to answer business questions and fathom real-world problems. Researchers utilize explanatory apparatuses called conceptual systems to form conceptual refinements and organize thoughts required for investigation purposes.

Conceptual Research Framework

A conceptual research framework is built utilizing existing writing and studies from which inferences can be drawn. A conceptual research system constitutes a researcher’s combination of past research and related work and clarifies the phenomenon. The study is conducted to diminish the existing information gap on a specific theme and make important and dependable data available.

The following steps can be taken to make a conceptual research framework:

Explain a topic for research

The primary step is to characterize the subject of your research. Most analysts will choose a topic relating to their field of expertise.

Collect and Organize relevant research

As conceptual research depends on pre-existing studies and writing, analysts must collect all important data relating to their point. It’s imperative to utilize dependable sources and information from scientific journals or investigate well-presumed papers. As conceptual research does not utilize experimentation and tests, the significance of analyzing dependable, fact-based information is reinforced.

Distinguish factors for the research

The other step is to choose important factors for their research. These factors will be the measuring sticks by which inductions will be drawn. They provide modern scope to inquire about and offer to help identify how distinctive factors may influence the subject of research.

Make the Framework

The last step is to make the research framework by utilizing significant writing, factors, and other significant material.

Advantages of Conceptual Research

It requires few resources compared to other types of market research where practical experimentation is required. This spares time and assets.

It is helpful as this form of investigation only requires the assessment of existing writing.

Disadvantages of Conceptual Research

Speculations based on existing writing instead of experimentation and perception draw conclusions that are less fact-based and may not essentially be considered dependable.

Often, we see philosophical hypotheses being countered or changed since their conclusions or inferences are drawn from existing writings instead of practical experimentation.

Empirical Research:

Empirical research is based on observed and established phenomena and determines information from real involvement instead of hypothesis or conviction. It derives knowledge from actual experiences. How do you know a study is empirical? Pay attention to the subheadings inside the article, book, or report and examine them to seek a depiction of the investigating “strategy.” Inquire yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to see for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or wonders being studied

- Description of the methods used to consider the population of the area of phenomena, including various aspects like choice criteria, controls, and testing instruments.

Empirical Research Framework:

Since empirical research is based on perception and capturing experiences, it is critical to arrange the steps to experiment and how to examine it. This will empower the analyst to resolve issues or obstacles amid the test.

- Define your purpose for this research:

This is often the step where the analyst must answer questions like what precisely I need to discover? What is the issue articulation? Are there any issues regarding the accessibility of knowledge, data, time, or assets? Will this research be more useful than what it’ll cost? Before going ahead, an analyst should characterize his reason for the investigation and plan to carry out assist tasks.

- Supporting theories and relevant literature:

The analyst should discover if some hypotheses can be connected to his research issue. He must figure out if any hypothesis can offer assistance in supporting his discoveries. All kinds of significant writing will offer assistance to the analyst to discover if others have researched this before. The analyst will also need to set up presumptions and also discover if there’s any history concerning his investigation issue

- Creation of Hypothesis and measurement:

Before starting the proper research related to his subject, he must give himself a working theory or figure out the probable result. The researcher has to set up factors, choose the environment for the research and find out how he can relate between the variables. The researcher will also need to characterize the units of estimations, tolerable degree for mistakes, and discover in the event that the estimation chosen will be approved by others.

- Methodology and data collection:

In this step, the analyst has to characterize a strategy for conducting his investigation. He must set up tests to gather the information that can empower him to propose the theory. The analyst will choose whether to require a test or non-test strategy for conducting the research. The research design will shift depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Finally, the analyst will discover parameters that will influence the legitimacy of the research plan. The information collected will need to be done by choosing appropriate tests depending on the inquire-about address. To carry out the inquiry, he can utilize one of the numerous testing strategies. Once information collection is complete, the analyst will have experimental information which must be examined.

- Data Analysis and result:

Data analysis can be tried in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. The analyst will need to discover what subjective strategy or quantitative strategy will be required or will require a combination of both. Depending on the examination of his information, he will know if his speculation is backed or rejected. Analyzing this information is the foremost vital portion to bolster his speculation.

A report will need to be made with the discoveries of the research. The analyst can deliver the hypotheses and writing that support his investigation. He can make recommendations or suggestions to assist research on his subject

Advantages of empirical research

- Empirical research points to discover the meaning behind a specific phenomenon. In other words, it looks for answers to how and why something works the way it is.

- By recognizing why something happens, it is conceivable to imitate or avoid comparative events.

- The adaptability of the research permits the analysts to alter certain perspectives of the research and alter them to new objectives.

- It is more dependable since it speaks to a real-life involvement and not fair theories.

- Data collected through experimental research may be less biased since the analyst is there amid the collection handle. In contrast, it is incomprehensible to confirm the precision of the information in non-empirical research.

Disadvantages of empirical research

- It can be time-consuming depending on the research subject that you have chosen.

- It isn’t a cost-effective way of information collection in most cases because of the viable costly strategies of information gathering. Additionally, it may require traveling between numerous locations.

- Lack of proof and research subjects may not surrender the required result. A little test estimate avoids generalization since it may not be enough to speak to the target audience.

- It isn’t easy to induce data on touchy points. Additionally, analysts may require participants’ consent to utilize the data

Difference Between Conceptual and Empirical Research

Conceptual research and empirical research are two ways of doing logical research. These are two restricting investigation systems since conceptual research doesn’t include any tests, and empirical investigation does.

Conceptual research includes unique thoughts and ideas; as it may, it doesn’t include any experiments and tests. Empirical research, on the other hand, includes phenomena that are observable and can be measured.

- Type of Studies:

Philosophical research studies are cases of conceptual research, while empirical research incorporates both quantitative and subjective studies.

The major difference between conceptual and empirical investigation is that conceptual research involves unique thoughts and ideas, though experimental investigation includes investigation based on perception, tests, and unquestionable evidence.

References:

- Empirical Research: Advantages, Drawbacks, and Differences with Non-Empirical Research. In Voicedocs . Retrieved from https://voicedocs.com/en/blog/empirical-research-advantages-drawbacks-and-differences-non-empirical-research

- Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples. In QuestionPro . Retrieved from https://www.questionpro.com/blog/empirical-research/

- Conceptual vs. empirical research: which is better? In Enago Academy . Retrieved from https://www.enago.com/academy/conceptual-vs-empirical-research-which-is-better/

Related Articles

Best Microchannel Pipettes: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction Pipetting, at first glance, would seem a fairly simple and easy task. Essentially described as glass or plastic tubes used to measure and transfer

Resource Identification Initiative

Resource Identification Initiative: A Key to Scientific Success and Analytics The key to success can be found in the essential principles of the Resource Identification

Best Microcentrifuges: A Comprehensive Guide

INTRODUCTION AND BRIEF HISTORY One of the most important pieces of equipment in the laboratory is the centrifuge, which facilitates the separation of samples of

Best Benchtop Centrifuges: A Comprehensive Guide

Top sales products.

Hess Tissue Forceps

Optogenetics Optical Fiber

Protective Virus Shield for Counter & Desk – Freestanding Clear Acrylic Shield 36″ x 24″

Digital Microscope

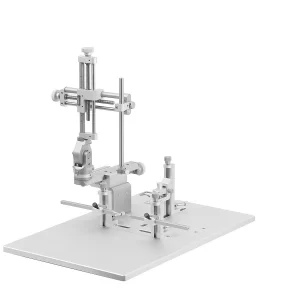

Stereotaxic Portable Digital System for Rat & Mouse

Castroviejo 1×2 teeth tissue forceps.

Our Location

Conduct science.

- Become a Partner

- Social Media

- Career /Academia

- Privacy Policy

- Shipping & Returns

- Request a quote

Customer service

- Account details

- Lost password

DISCLAIMER: ConductScience and affiliate products are NOT designed for human consumption, testing, or clinical utilization. They are designed for pre-clinical utilization only. Customers purchasing apparatus for the purposes of scientific research or veterinary care affirm adherence to applicable regulatory bodies for the country in which their research or care is conducted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

Julie a. luft.

† Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Sophia Jeong

‡ Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Robert Idsardi

§ Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Grant Gardner

∥ Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Associated Data

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

Comparison of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual reviews

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

It should be noted that there are different types of literature reviews, and many books and articles have been written about the different ways to embark on these types of reviews. Among these different resources, the following may be helpful in considering how to refine the review process for scholarly journals:

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.