Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

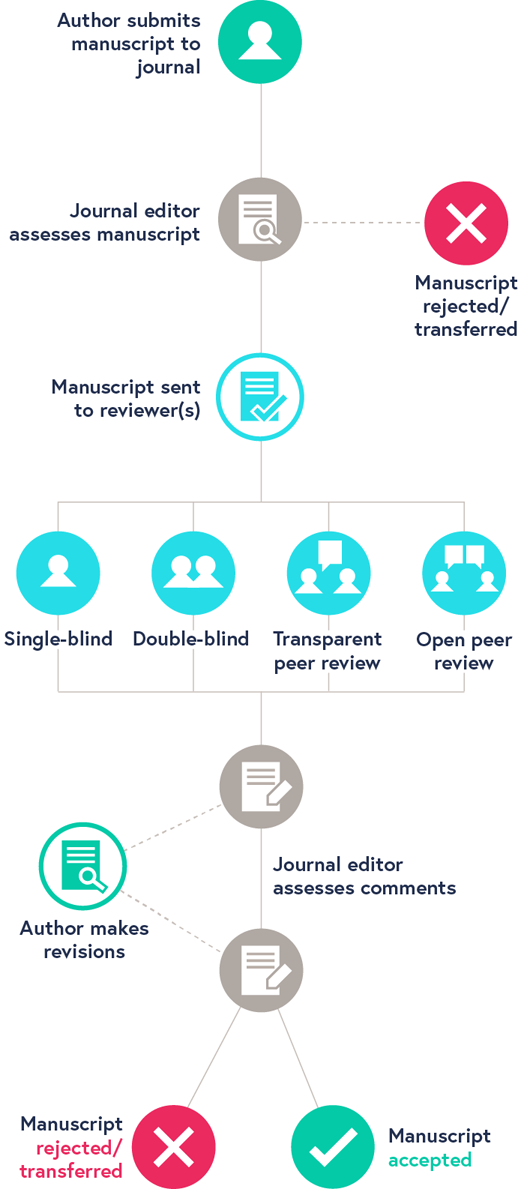

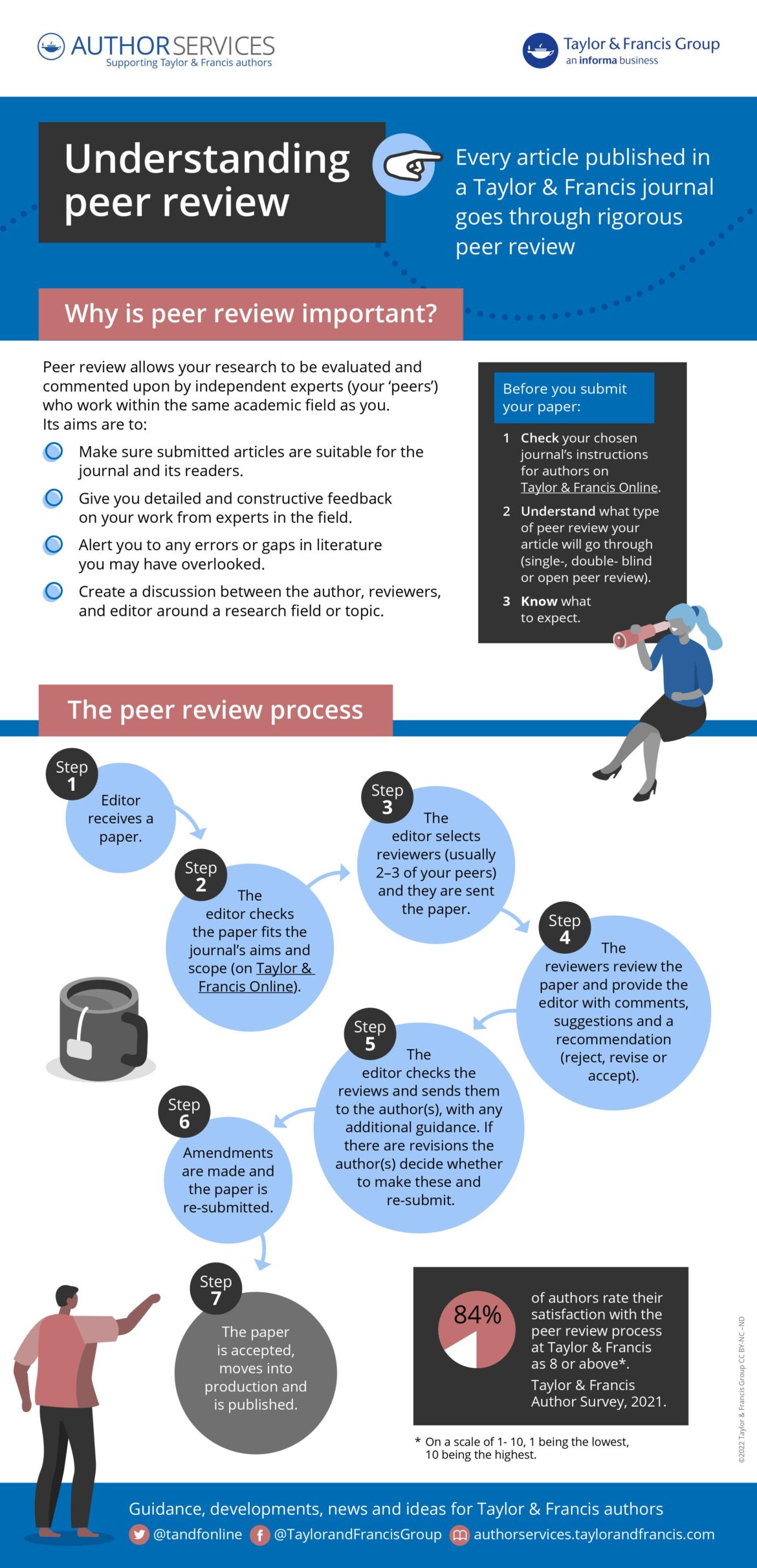

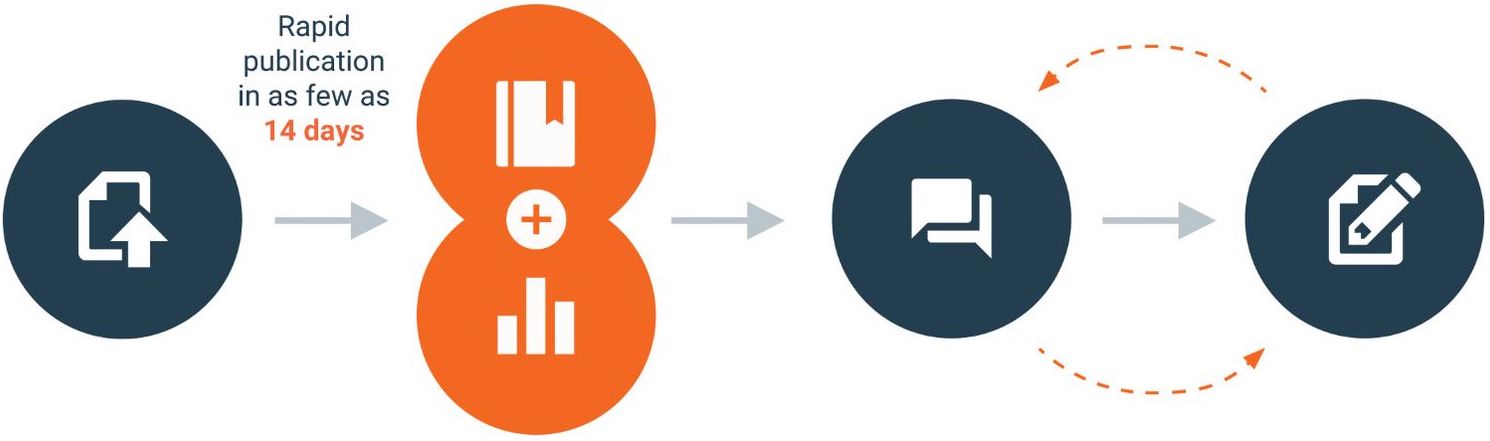

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Reumatologia

- v.59(1); 2021

Peer review guidance: a primer for researchers

Olena zimba.

1 Department of Internal Medicine No. 2, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

Armen Yuri Gasparyan

2 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK

The peer review process is essential for quality checks and validation of journal submissions. Although it has some limitations, including manipulations and biased and unfair evaluations, there is no other alternative to the system. Several peer review models are now practised, with public review being the most appropriate in view of the open science movement. Constructive reviewer comments are increasingly recognised as scholarly contributions which should meet certain ethics and reporting standards. The Publons platform, which is now part of the Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), credits validated reviewer accomplishments and serves as an instrument for selecting and promoting the best reviewers. All authors with relevant profiles may act as reviewers. Adherence to research reporting standards and access to bibliographic databases are recommended to help reviewers draft evidence-based and detailed comments.

Introduction

The peer review process is essential for evaluating the quality of scholarly works, suggesting corrections, and learning from other authors’ mistakes. The principles of peer review are largely based on professionalism, eloquence, and collegiate attitude. As such, reviewing journal submissions is a privilege and responsibility for ‘elite’ research fellows who contribute to their professional societies and add value by voluntarily sharing their knowledge and experience.

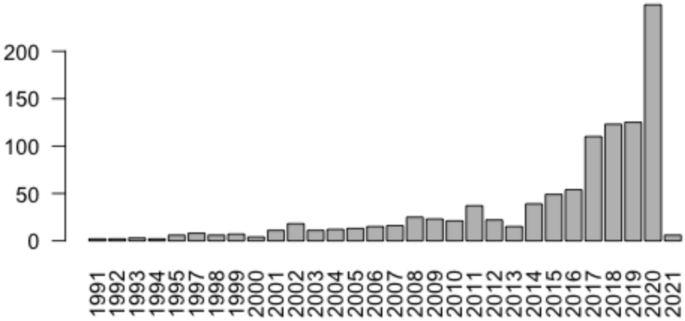

Since the launch of the first academic periodicals back in 1665, the peer review has been mandatory for validating scientific facts, selecting influential works, and minimizing chances of publishing erroneous research reports [ 1 ]. Over the past centuries, peer review models have evolved from single-handed editorial evaluations to collegial discussions, with numerous strengths and inevitable limitations of each practised model [ 2 , 3 ]. With multiplication of periodicals and editorial management platforms, the reviewer pool has expanded and internationalized. Various sets of rules have been proposed to select skilled reviewers and employ globally acceptable tools and language styles [ 4 , 5 ].

In the era of digitization, the ethical dimension of the peer review has emerged, necessitating involvement of peers with full understanding of research and publication ethics to exclude unethical articles from the pool of evidence-based research and reviews [ 6 ]. In the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, some, if not most, journals face the unavailability of skilled reviewers, resulting in an unprecedented increase of articles without a history of peer review or those with surprisingly short evaluation timelines [ 7 ].

Editorial recommendations and the best reviewers

Guidance on peer review and selection of reviewers is currently available in the recommendations of global editorial associations which can be consulted by journal editors for updating their ethics statements and by research managers for crediting the evaluators. The International Committee on Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) qualifies peer review as a continuation of the scientific process that should involve experts who are able to timely respond to reviewer invitations, submitting unbiased and constructive comments, and keeping confidentiality [ 8 ].

The reviewer roles and responsibilities are listed in the updated recommendations of the Council of Science Editors (CSE) [ 9 ] where ethical conduct is viewed as a premise of the quality evaluations. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) further emphasizes editorial strategies that ensure transparent and unbiased reviewer evaluations by trained professionals [ 10 ]. Finally, the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) prioritizes selecting the best reviewers with validated profiles to avoid substandard or fraudulent reviewer comments [ 11 ]. Accordingly, the Sarajevo Declaration on Integrity and Visibility of Scholarly Publications encourages reviewers to register with the Open Researcher and Contributor ID (ORCID) platform to validate and publicize their scholarly activities [ 12 ].

Although the best reviewer criteria are not listed in the editorial recommendations, it is apparent that the manuscript evaluators should be active researchers with extensive experience in the subject matter and an impressive list of relevant and recent publications [ 13 ]. All authors embarking on an academic career and publishing articles with active contact details can be involved in the evaluation of others’ scholarly works [ 14 ]. Ideally, the reviewers should be peers of the manuscript authors with equal scholarly ranks and credentials.

However, journal editors may employ schemes that engage junior research fellows as co-reviewers along with their mentors and senior fellows [ 15 ]. Such a scheme is successfully practised within the framework of the Emerging EULAR (European League Against Rheumatism) Network (EMEUNET) where seasoned authors (mentors) train ongoing researchers (mentees) how to evaluate submissions to the top rheumatology journals and select the best evaluators for regular contributors to these journals [ 16 ].

The awareness of the EQUATOR Network reporting standards may help the reviewers to evaluate methodology and suggest related revisions. Statistical skills help the reviewers to detect basic mistakes and suggest additional analyses. For example, scanning data presentation and revealing mistakes in the presentation of means and standard deviations often prompt re-analyses of distributions and replacement of parametric tests with non-parametric ones [ 17 , 18 ].

Constructive reviewer comments

The main goal of the peer review is to support authors in their attempt to publish ethically sound and professionally validated works that may attract readers’ attention and positively influence healthcare research and practice. As such, an optimal reviewer comment has to comprehensively examine all parts of the research and review work ( Table I ). The best reviewers are viewed as contributors who guide authors on how to correct mistakes, discuss study limitations, and highlight its strengths [ 19 ].

Structure of a reviewer comment to be forwarded to authors

| Section | Notes |

|---|---|

| Introductory line | Summarizes the overall impression about the manuscript validity and implications |

| Evaluation of the title, abstract and keywords | Evaluates the title correctness and completeness, inclusion of all relevant keywords, study design terms, information load, and relevance of the abstract |

| Major comments | Specifically analyses each manuscript part in line with available research reporting standards, supports all suggestions with solid evidence, weighs novelty of hypotheses and methodological rigour, highlights the choice of study design, points to missing/incomplete ethics approval statements, rights to re-use graphics, accuracy and completeness of statistical analyses, professionalism of bibliographic searches and inclusion of updated and relevant references |

| Minor comments | Identifies language mistakes, typos, inappropriate format of graphics and references, length of texts and tables, use of supplementary material, unusual sections and order, completeness of scholarly contribution, conflict of interest, and funding statements |

| Concluding remarks | Reflects on take-home messages and implications |

Some of the currently practised review models are well positioned to help authors reveal and correct their mistakes at pre- or post-publication stages ( Table II ). The global move toward open science is particularly instrumental for increasing the quality and transparency of reviewer contributions.

Advantages and disadvantages of common manuscript evaluation models

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| In-house (internal) editorial review | Allows detection of major flaws and errors that justify outright rejections; rarely, outstanding manuscripts are accepted without delays | Journal staff evaluations may be biased; manuscript acceptance without external review may raise concerns of soft quality checks |

| Single-blind peer review | Masking reviewer identity prevents personal conflicts in small (closed) professional communities | Reviewer access to author profiles may result in biased and subjective evaluations |

| Double-blind peer review | Concealing author and reviewer identities prevents biased evaluations, particularly in small communities | Masking all identifying information is technically burdensome and not always possible |

| Open (public) peer review | May increase quality, objectivity, and accountability of reviewer evaluations; it is now part of open science culture | Peers who do not wish to disclose their identity may decline reviewer invitations |

| Post-publication open peer review | May accelerate dissemination of influential reports in line with the concept “publish first, judge later”; this concept is practised by some open-access journals (e.g., F1000 Research) | Not all manuscripts benefit from open dissemination without peers’ input; post-publication review may delay detection of minor or major mistakes |

| Post-publication social media commenting | May reveal some mistakes and misconduct and improve public perception of article implications | Not all communities use social media for commenting and other academic purposes |

Since there are no universally acceptable criteria for selecting reviewers and structuring their comments, instructions of all peer-reviewed journal should specify priorities, models, and expected review outcomes [ 20 ]. Monitoring and reporting average peer review timelines is also required to encourage timely evaluations and avoid delays. Depending on journal policies and article types, the first round of peer review may last from a few days to a few weeks. The fast-track review (up to 3 days) is practised by some top journals which process clinical trial reports and other priority items.

In exceptional cases, reviewer contributions may result in substantive changes, appreciated by authors in the official acknowledgments. In most cases, however, reviewers should avoid engaging in the authors’ research and writing. They should refrain from instructing the authors on additional tests and data collection as these may delay publication of original submissions with conclusive results.

Established publishers often employ advanced editorial management systems that support reviewers by providing instantaneous access to the review instructions, online structured forms, and some bibliographic databases. Such support enables drafting of evidence-based comments that examine the novelty, ethical soundness, and implications of the reviewed manuscripts [ 21 ].

Encouraging reviewers to submit their recommendations on manuscript acceptance/rejection and related editorial tasks is now a common practice. Skilled reviewers may prompt the editors to reject or transfer manuscripts which fall outside the journal scope, perform additional ethics checks, and minimize chances of publishing erroneous and unethical articles. They may also raise concerns over the editorial strategies in their comments to the editors.

Since reviewer and editor roles are distinct, reviewer recommendations are aimed at helping editors, but not at replacing their decision-making functions. The final decisions rest with handling editors. Handling editors weigh not only reviewer comments, but also priorities related to article types and geographic origins, space limitations in certain periods, and envisaged influence in terms of social media attention and citations. This is why rejections of even flawless manuscripts are likely at early rounds of internal and external evaluations across most peer-reviewed journals.

Reviewers are often requested to comment on language correctness and overall readability of the evaluated manuscripts. Given the wide availability of in-house and external editing services, reviewer comments on language mistakes and typos are categorized as minor. At the same time, non-Anglophone experts’ poor language skills often exclude them from contributing to the peer review in most influential journals [ 22 ]. Comments should be properly edited to convey messages in positive or neutral tones, express ideas of varying degrees of certainty, and present logical order of words, sentences, and paragraphs [ 23 , 24 ]. Consulting linguists on communication culture, passing advanced language courses, and honing commenting skills may increase the overall quality and appeal of the reviewer accomplishments [ 5 , 25 ].

Peer reviewer credits

Various crediting mechanisms have been proposed to motivate reviewers and maintain the integrity of science communication [ 26 ]. Annual reviewer acknowledgments are widely practised for naming manuscript evaluators and appreciating their scholarly contributions. Given the need to weigh reviewer contributions, some journal editors distinguish ‘elite’ reviewers with numerous evaluations and award those with timely and outstanding accomplishments [ 27 ]. Such targeted recognition ensures ethical soundness of the peer review and facilitates promotion of the best candidates for grant funding and academic job appointments [ 28 ].

Also, large publishers and learned societies issue certificates of excellence in reviewing which may include Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points [ 29 ]. Finally, an entirely new crediting mechanism is proposed to award bonus points to active reviewers who may collect, transfer, and use these points to discount gold open-access charges within the publisher consortia [ 30 ].

With the launch of Publons ( http://publons.com/ ) and its integration with Web of Science Group (Clarivate Analytics), reviewer recognition has become a matter of scientific prestige. Reviewers can now freely open their Publons accounts and record their contributions to online journals with Digital Object Identifiers (DOI). Journal editors, in turn, may generate official reviewer acknowledgments and encourage reviewers to forward them to Publons for building up individual reviewer and journal profiles. All published articles maintain e-links to their review records and post-publication promotion on social media, allowing the reviewers to continuously track expert evaluations and comments. A paid-up partnership is also available to journals and publishers for automatically transferring peer-review records to Publons upon mutually acceptable arrangements.

Listing reviewer accomplishments on an individual Publons profile showcases scholarly contributions of the account holder. The reviewer accomplishments placed next to the account holders’ own articles and editorial accomplishments point to the diversity of scholarly contributions. Researchers may establish links between their Publons and ORCID accounts to further benefit from complementary services of both platforms. Publons Academy ( https://publons.com/community/academy/ ) additionally offers an online training course to novice researchers who may improve their reviewing skills under the guidance of experienced mentors and journal editors. Finally, journal editors may conduct searches through the Publons platform to select the best reviewers across academic disciplines.

Peer review ethics

Prior to accepting reviewer invitations, scholars need to weigh a number of factors which may compromise their evaluations. First of all, they are required to accept the reviewer invitations if they are capable of timely submitting their comments. Peer review timelines depend on article type and vary widely across journals. The rules of transparent publishing necessitate recording manuscript submission and acceptance dates in article footnotes to inform readers of the evaluation speed and to help investigators in the event of multiple unethical submissions. Timely reviewer accomplishments often enable fast publication of valuable works with positive implications for healthcare. Unjustifiably long peer review, on the contrary, delays dissemination of influential reports and results in ethical misconduct, such as plagiarism of a manuscript under evaluation [ 31 ].

In the times of proliferation of open-access journals relying on article processing charges, unjustifiably short review may point to the absence of quality evaluation and apparently ‘predatory’ publishing practice [ 32 , 33 ]. Authors when choosing their target journals should take into account the peer review strategy and associated timelines to avoid substandard periodicals.

Reviewer primary interests (unbiased evaluation of manuscripts) may come into conflict with secondary interests (promotion of their own scholarly works), necessitating disclosures by filling in related parts in the online reviewer window or uploading the ICMJE conflict of interest forms. Biomedical reviewers, who are directly or indirectly supported by the pharmaceutical industry, may encounter conflicts while evaluating drug research. Such instances require explicit disclosures of conflicts and/or rejections of reviewer invitations.

Journal editors are obliged to employ mechanisms for disclosing reviewer financial and non-financial conflicts of interest to avoid processing of biased comments [ 34 ]. They should also cautiously process negative comments that oppose dissenting, but still valid, scientific ideas [ 35 ]. Reviewer conflicts that stem from academic activities in a competitive environment may introduce biases, resulting in unfair rejections of manuscripts with opposing concepts, results, and interpretations. The same academic conflicts may lead to coercive reviewer self-citations, forcing authors to incorporate suggested reviewer references or face negative feedback and an unjustified rejection [ 36 ]. Notably, several publisher investigations have demonstrated a global scale of such misconduct, involving some highly cited researchers and top scientific journals [ 37 ].

Fake peer review, an extreme example of conflict of interest, is another form of misconduct that has surfaced in the time of mass proliferation of gold open-access journals and publication of articles without quality checks [ 38 ]. Fake reviews are generated by manipulating authors and commercial editing agencies with full access to their own manuscripts and peer review evaluations in the journal editorial management systems. The sole aim of these reviews is to break the manuscript evaluation process and to pave the way for publication of pseudoscientific articles. Authors of these articles are often supported by funds intended for the growth of science in non-Anglophone countries [ 39 ]. Iranian and Chinese authors are often caught submitting fake reviews, resulting in mass retractions by large publishers [ 38 ]. Several suggestions have been made to overcome this issue, with assigning independent reviewers and requesting their ORCID IDs viewed as the most practical options [ 40 ].

Conclusions

The peer review process is regulated by publishers and editors, enforcing updated global editorial recommendations. Selecting the best reviewers and providing authors with constructive comments may improve the quality of published articles. Reviewers are selected in view of their professional backgrounds and skills in research reporting, statistics, ethics, and language. Quality reviewer comments attract superior submissions and add to the journal’s scientific prestige [ 41 ].

In the era of digitization and open science, various online tools and platforms are available to upgrade the peer review and credit experts for their scholarly contributions. With its links to the ORCID platform and social media channels, Publons now offers the optimal model for crediting and keeping track of the best and most active reviewers. Publons Academy additionally offers online training for novice researchers who may benefit from the experience of their mentoring editors. Overall, reviewer training in how to evaluate journal submissions and avoid related misconduct is an important process, which some indexed journals are experimenting with [ 42 ].

The timelines and rigour of the peer review may change during the current pandemic. However, journal editors should mobilize their resources to avoid publication of unchecked and misleading reports. Additional efforts are required to monitor published contents and encourage readers to post their comments on publishers’ online platforms (blogs) and other social media channels [ 43 , 44 ].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

What is peer review.

Peer review is ‘a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already know.’ You can learn more in this explainer from the Social Science Space.

Peer review brings academic research to publication in the following ways:

- Evaluation – Peer review is an effective form of research evaluation to help select the highest quality articles for publication.

- Integrity – Peer review ensures the integrity of the publishing process and the scholarly record. Reviewers are independent of journal publications and the research being conducted.

- Quality – The filtering process and revision advice improve the quality of the final research article as well as offering the author new insights into their research methods and the results that they have compiled. Peer review gives authors access to the opinions of experts in the field who can provide support and insight.

Types of peer review

- Single-anonymized – the name of the reviewer is hidden from the author.

- Double-anonymized – names are hidden from both reviewers and the authors.

- Triple-anonymized – names are hidden from authors, reviewers, and the editor.

- Open peer review comes in many forms . At Sage we offer a form of open peer review on some journals via our Transparent Peer Review program , whereby the reviews are published alongside the article. The names of the reviewers may also be published, depending on the reviewers’ preference.

- Post publication peer review can offer useful interaction and a discussion forum for the research community. This form of peer review is not usual or appropriate in all fields.

To learn more about the different types of peer review, see page 14 of ‘ The Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review ’ from Sense about Science.

Please double check the manuscript submission guidelines of the journal you are reviewing in order to ensure that you understand the method of peer review being used.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- Transparent Peer Review

- How to Review Articles

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage editorial policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

What is peer review?

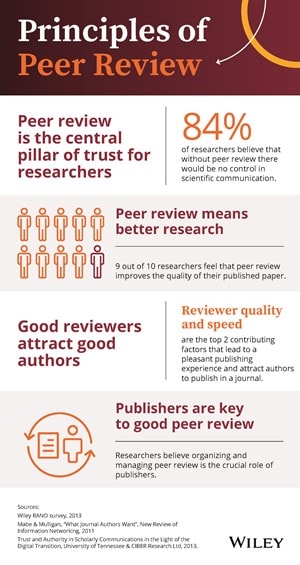

Reviewers play a pivotal role in scholarly publishing. The peer review system exists to validate academic work, helps to improve the quality of published research, and increases networking possibilities within research communities. Despite criticisms, peer review is still the only widely accepted method for research validation and has continued successfully with relatively minor changes for some 350 years.

Elsevier relies on the peer review process to uphold the quality and validity of individual articles and the journals that publish them.

Peer review has been a formal part of scientific communication since the first scientific journals appeared more than 300 years ago. The Philosophical Transactions opens in new tab/window of the Royal Society is thought to be the first journal to formalize the peer review process opens in new tab/window under the editorship of Henry Oldenburg (1618- 1677).

Despite many criticisms about the integrity of peer review, the majority of the research community still believes peer review is the best form of scientific evaluation. This opinion was endorsed by the outcome of a survey Elsevier and Sense About Science conducted in 2009 opens in new tab/window and has since been further confirmed by other publisher and scholarly organization surveys. Furthermore, a 2015 survey by the Publishing Research Consortium opens in new tab/window , saw 82% of researchers agreeing that “without peer review there is no control in scientific communication.”

To learn more about peer review, visit Elsevier’s free e-learning platform Researcher Academy opens in new tab/window and see our resources below.

The peer review process

Types of peer review.

Peer review comes in different flavours. Each model has its own advantages and disadvantages, and often one type of review will be preferred by a subject community. Before submitting or reviewing a paper, you must therefore check which type is employed by the journal so you are aware of the respective rules. In case of questions regarding the peer review model employed by the journal for which you have been invited to review, consult the journal’s homepage or contact the editorial office directly.

Single anonymized review

In this type of review, the names of the reviewers are hidden from the author. This is the traditional method of reviewing and is the most common type by far. Points to consider regarding single anonymized review include:

Reviewer anonymity allows for impartial decisions , as the reviewers will not be influenced by potential criticism from the authors.

Authors may be concerned that reviewers in their field could delay publication, giving the reviewers a chance to publish first.

Reviewers may use their anonymity as justification for being unnecessarily critical or harsh when commenting on the authors’ work.

Double anonymized review

Both the reviewer and the author are anonymous in this model. Some advantages of this model are listed below.

Author anonymity limits reviewer bias, such as on author's gender, country of origin, academic status, or previous publication history.

Articles written by prestigious or renowned authors are considered based on the content of their papers, rather than their reputation.

But bear in mind that despite the above, reviewers can often identify the author through their writing style, subject matter, or self-citation – it is exceedingly difficult to guarantee total author anonymity. More information for authors can be found in our double-anonymized peer review guidelines .

Triple anonymized review

With triple anonymized review, reviewers are anonymous to the author, and the author's identity is unknown to both the reviewers and the editor. Articles are anonymized at the submission stage and are handled in a way to minimize any potential bias towards the authors. However, it should be noted that:

The complexities involved with anonymizing articles/authors to this level are considerable.

As with double anonymized review, there is still a possibility for the editor and/or reviewers to correctly identify the author(s) from their writing style, subject matter, citation patterns, or other methodologies.

Open review

Open peer review is an umbrella term for many different models aiming at greater transparency during and after the peer review process. The most common definition of open review is when both the reviewer and author are known to each other during the peer review process. Other types of open peer review consist of:

Publication of reviewers’ names on the article page

Publication of peer review reports alongside the article, either signed or anonymous

Publication of peer review reports (signed or anonymous) with authors’ and editors’ responses alongside the article

Publication of the paper after pre-checks and opening a discussion forum to the community who can then comment (named or anonymous) on the article

Many believe this is the best way to prevent malicious comments, stop plagiarism, prevent reviewers from following their own agenda, and encourage open, honest reviewing. Others see open review as a less honest process, in which politeness or fear of retribution may cause a reviewer to withhold or tone down criticism. For three years, five Elsevier journals experimented with publication of peer review reports (signed or anonymous) as articles alongside the accepted paper on ScienceDirect ( example opens in new tab/window ).

Read more about the experiment

More transparent peer review

Transparency is the key to trust in peer review and as such there is an increasing call towards more transparency around the peer review process . In an effort to promote transparency in the peer review process, many Elsevier journals therefore publish the name of the handling editor of the published paper on ScienceDirect. Some journals also provide details about the number of reviewers who reviewed the article before acceptance. Furthermore, in order to provide updates and feedback to reviewers, most Elsevier journals inform reviewers about the editor’s decision and their peers’ recommendations.

Article transfer service: sharing reviewer comments

Elsevier authors may be invited to transfer their article submission from one journal to another for free if their initial submission was not successful.

As a referee, your review report (including all comments to the author and editor) will be transferred to the destination journal, along with the manuscript. The main benefit is that reviewers are not asked to review the same manuscript several times for different journals.

Tools and resources

Interesting reads.

Chapter 2 of Academic and Professional Publishing, 2012, by Irene Hames in 2012 opens in new tab/window

"Is Peer Review in Crisis?" Perspectives in Publishing No 2, August 2004, by Adrian Mulligan opens in new tab/window

“The history of the peer-review process” Trends in Biotechnology, 2002, by Ray Spier opens in new tab/window

Reviewers’ Update articles

Peer review using today’s technology

Lifting the lid on publishing peer review reports: an interview with Bahar Mehmani and Flaminio Squazzoni

How face-to-face peer review can benefit authors and journals alike

Innovation in peer review: introducing “volunpeers”

Results masked review: peer review without publication bias

Elsevier Researcher Academy modules

The certified peer reviewer course opens in new tab/window

Transparency in peer review opens in new tab/window

- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- Science Experiments for Kids

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 2 September 2022.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, frequently asked questions about peer review.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymised) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymised comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymised) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymised) review – where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymised – does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimises potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymise everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimise back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarise the argument in your own words

Summarising the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organised. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticised, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the ‘compliment sandwich’, where you ‘sandwich’ your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarised or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 02). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/peer-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a double-blind study | introduction & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data cleaning | a guide with examples & steps.

Explainer: what is peer review?

Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London

Novak Druce Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

Thomas Roulet does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

Andre Spicer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

City, University of London provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

We’ve all heard the phrase “peer review” as giving credence to research and scholarly papers, but what does it actually mean? How does it work?

Peer review is one of the gold standards of science. It’s a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already knew.

Most scientific journals, conferences and grant applications have some sort of peer review system. In most cases it is “double blind” peer review. This means evaluators do not know the author(s), and the author(s) do not know the identity of the evaluators. The intention behind this system is to ensure evaluation is not biased.

The more prestigious the journal, conference, or grant, the more demanding will be the review process, and the more likely the rejection. This prestige is why these papers tend to be more read and more cited.

The process in details

The peer review process for journals involves at least three stages.

1. The desk evaluation stage

When a paper is submitted to a journal, it receives an initial evaluation by the chief editor, or an associate editor with relevant expertise.

At this stage, either can “desk reject” the paper: that is, reject the paper without sending it to blind referees. Generally, papers are desk rejected if the paper doesn’t fit the scope of the journal or there is a fundamental flaw which makes it unfit for publication.

In this case, the rejecting editors might write a letter summarising his or her concerns. Some journals, such as the British Medical Journal , desk reject up to two-thirds or more of the papers.

2. The blind review

If the editorial team judges there are no fundamental flaws, they send it for review to blind referees. The number of reviewers depends on the field: in finance there might be only one reviewer, while journals in other fields of social sciences might ask up to four reviewers. Those reviewers are selected by the editor on the basis of their expert knowledge and their absence of a link with the authors.

Reviewers will decide whether to reject the paper, to accept it as it is (which rarely happens) or to ask for the paper to be revised. This means the author needs to change the paper in line with the reviewers’ concerns.

Usually the reviews deal with the validity and rigour of the empirical method, and the importance and originality of the findings (what is called the “contribution” to the existing literature). The editor collects those comments, weights them, takes a decision, and writes a letter summarising the reviewers’ and his or her own concerns.

It can therefore happen that despite hostility on the part of the reviewers, the editor could offer the paper a subsequent round of revision. In the best journals in the social sciences, 10% to 20% of the papers are offered a “revise-and-resubmit” after the first round.

3. The revisions – if you are lucky enough

If the paper has not been rejected after this first round of review, it is sent back to the author(s) for a revision. The process is repeated as many times as necessary for the editor to reach a consensus point on whether to accept or reject the paper. In some cases this can last for several years.

Ultimately, less than 10% of the submitted papers are accepted in the best journals in the social sciences. The renowned journal Nature publishes around 7% of the submitted papers.

Strengths and weaknesses of the peer review process

The peer review process is seen as the gold standard in science because it ensures the rigour, novelty, and consistency of academic outputs. Typically, through rounds of review, flawed ideas are eliminated and good ideas are strengthened and improved. Peer reviewing also ensures that science is relatively independent.

Because scientific ideas are judged by other scientists, the crucial yardstick is scientific standards. If other people from outside of the field were involved in judging ideas, other criteria such as political or economic gain might be used to select ideas. Peer reviewing is also seen as a crucial way of removing personalities and bias from the process of judging knowledge.

Despite the undoubted strengths, the peer review process as we know it has been criticised . It involves a number of social interactions that might create biases – for example, authors might be identified by reviewers if they are in the same field, and desk rejections are not blind.

It might also favour incremental (adding to past research) rather than innovative (new) research. Finally, reviewers are human after all and can make mistakes, misunderstand elements, or miss errors.

Are there any alternatives?

Defenders of the peer review system say although there are flaws, we’re yet to find a better system to evaluate research. However, a number of innovations have been introduced in the academic review system to improve its objectivity and efficiency.

Some new open-access journals (such as PLOS ONE ) publish papers with very little evaluation (they check the work is not deeply flawed methodologically). The focus there is on the post-publication peer review system: all readers can comment and criticise the paper.

Some journals such as Nature, have made part of the review process public (“open” review), offering a hybrid system in which peer review plays a role of primary gate keepers, but the public community of scholars judge in parallel (or afterwards in some other journals) the value of the research.

Another idea is to have a set of reviewers rating the paper each time it is revised. In this case, authors will be able to choose whether they want to invest more time in a revision to obtain a better rating, and get their work publicly recognised.

- Peer review

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Health Safety and Wellbeing Advisor

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Peer review process

Introduction to peer review, what is peer review.

Peer review is the system used to assess the quality of a manuscript before it is published. Independent researchers in the relevant research area assess submitted manuscripts for originality, validity and significance to help editors determine whether a manuscript should be published in their journal.

How does it work?

When a manuscript is submitted to a journal, it is assessed to see if it meets the criteria for submission. If it does, the editorial team will select potential peer reviewers within the field of research to peer-review the manuscript and make recommendations.

There are four main types of peer review used by BMC:

Single-blind: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report.

Double-blind: the reviewers do not know the names of the authors, and the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript.

Open peer: authors know who the reviewers are, and the reviewers know who the authors are. If the manuscript is accepted, the named reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.

Transparent peer: the reviewers know the names of the authors, but the authors do not know who reviewed their manuscript unless the reviewer chooses to sign their report. If the manuscript is accepted, the anonymous reviewer reports are published alongside the article and the authors’ response to the reviewer.