Virginia Woolf on Being Ill as a Portal to Self-Understanding

By maria popova.

“The body provides something for the spirit to look after and use,” computing pioneer Alan Turing wrote as he contemplated the binary code of body and spirit in the spring of his twenty-first year, having just lost the love of his life to tuberculosis. Nothing garbles that code more violently than illness — from the temporary terrors of food poisoning to the existential tumult of a terminal diagnosis — our entire mental and emotional being is hijacked by the demands of a malcontented body as dis-ease, in the most literal sense, fills sinew and spirit alike. These rude reminders of our atomic fragility are perhaps the most discomfiting yet most common human experience — it is difficult, if at all possible, to find a person unaffected by illness, for we have all been or will be ill, and have all loved or will love someone afflicted by illness.

No one has articulated the peculiar vexations of illness, nor addressed the psychic transcendence accessible amid the terrors of the body, more thoughtfully than Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) in her 1926 essay “On Being Ill,” later included in the indispensable posthumous collection of her Selected Essays ( public library ).

Half a century before Susan Sontag’s landmark book Illness as Metaphor , Woolf writes:

Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness, how we go down into the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers when we have a tooth out and come to the surface in the dentist’s arm-chair and confuse his “Rinse the mouth — rinse the mouth” with the greeting of the Deity stooping from the floor of Heaven to welcome us — when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. Novels, one would have thought, would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia; lyrics to toothache. But no; with a few exceptions — De Quincey attempted something of the sort in The Opium Eater ; there must be a volume or two about disease scattered through the pages of Proust — literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear, and, save for one or two passions such as desire and greed, is null, and negligible and non-existent.

Five years earlier, the ailing Rilke had written in a letter to a young woman : “I am not one of those who neglect the body in order to make of it a sacrificial offering for the soul, since my soul would thoroughly dislike being served in such a fashion.” Woolf, writing in the year of Rilke’s death and well ahead of the modern scientific inquiry into how the life of the body shapes the life of the mind , rebels against the residual Cartesianism of the mind-body divide with her characteristic fusion of wisdom and wry humor, channeled in exquisite prose:

All day, all night the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February. The creature within can only gaze through the pane — smudged or rosy; it cannot separate off from the body like the sheath of a knife or the pod of a pea for a single instant; it must go through the whole unending procession of changes, heat and cold, comfort and discomfort, hunger and satisfaction, health and illness, until there comes the inevitable catastrophe; the body smashes itself to smithereens, and the soul (it is said) escapes. But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record. People write always of the doings of the mind; the thoughts that come to it; its noble plans; how the mind has civilised the universe. They show it ignoring the body in the philosopher’s turret; or kicking the body, like an old leather football, across leagues of snow and desert in the pursuit of conquest or discovery. Those great wars which the body wages with the mind a slave to it, in the solitude of the bedroom against the assault of fever or the oncome of melancholia, are neglected. Nor is the reason far to seek. To look these things squarely in the face would need the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth. Short of these, this monster, the body, this miracle, its pain, will soon make us taper into mysticism, or rise, with rapid beats of the wings, into the raptures of transcendentalism.

“Is language the adequate expression of all realities?” Nietzsche had asked when Woolf was just genetic potential in her parents’ DNA. Language, the fully formed human argues as she considers the unreality of illness, has been utterly inadequate in conferring upon this commonest experience the dignity of representation it confers upon just about every other universal human experience:

To hinder the description of illness in literature, there is the poverty of the language. English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache. It has all grown one way.

In a passage Oliver Sacks could have written, Woolf pivots to the humorous, somehow without losing the profundity of the larger point:

Yet it is not only a new language that we need, more primitive, more sensual, more obscene, but a new hierarchy of the passions; love must be deposed in favour of a temperature of 104; jealousy give place to the pangs of sciatica; sleeplessness play the part of villain, and the hero become a white liquid with a sweet taste — that mighty Prince with the moths’ eyes and the feathered feet, one of whose names is Chloral.

And then, just like that, in classic Woolfian fashion, she fangs into the meat of the matter — the way we plunge into the universality of illness, so universal as to border on the banal, until we reach the rock bottom of utter existential aloneness:

That illusion of a world so shaped that it echoes every groan, of human beings so tied together by common needs and fears that a twitch at one wrist jerks another, where however strange your experience other people have had it too, where however far you travel in your own mind someone has been there before you — is all an illusion. We do not know our own souls, let alone the souls of others. Human beings do not go hand in hand the whole stretch of the way. There is a virgin forest in each; a snowfield where even the print of birds’ feet is unknown. Here we go alone, and like it better so. Always to have sympathy, always to be accompanied, always to be understood would be intolerable.

In health, Woolf argues, we maintain the illusion, both psychological and outwardly performative, of being cradled in the arms of civilization and society. Illness jolts us out of it, orphans us from belonging. But it also does something else, something beautiful and transcendent: In piercing the trance of busyness and obligation, it awakens us to the world about us, whose smallest details, neglected by our regular societal conscience, suddenly throb with aliveness and magnetic curiosity. It renders us “able, perhaps for the first time for years, to look round, to look up — to look, for example, at the sky”:

The first impression of that extraordinary spectacle is strangely overcoming. Ordinarily to look at the sky for any length of time is impossible. Pedestrians would be impeded and disconcerted by a public sky-gazer. What snatches we get of it are mutilated by chimneys and churches, serve as a background for man, signify wet weather or fine, daub windows gold, and, filling in the branches, complete the pathos of dishevelled autumnal plane trees in autumnal squares. Now, lying recumbent, staring straight up, the sky is discovered to be something so different from this that really it is a little shocking. This then has been going on all the time without our knowing it! — this incessant making up of shapes and casting them down, this buffeting of clouds together, and drawing vast trains of ships and waggons from North to South, this incessant ringing up and down of curtains of light and shade, this interminable experiment with gold shafts and blue shadows, with veiling the sun and unveiling it, with making rock ramparts and wafting them away…

But in the consolations of this transcendent communion with nature resides the most disquieting fact of existence — the awareness of an unfeeling universe, operating by impartial laws unconcerned with our individual fates:

Divinely beautiful it is also divinely heartless. Immeasurable resources are used for some purpose which has nothing to do with human pleasure or human profit.

It would take Woolf more than a decade to fully formulate, in a most stunning reflection , the paradoxical way in which these heartless laws are the very reason we are called to make beauty and meaning within their unfeeling parameters: “There is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself,” she would write in 1939. Now, in her meditation on illness, she hones the anchor of these ideas:

Poets have found religion in nature; people live in the country to learn virtue from plants. It is in their indifference that they are comforting. That snowfield of the mind, where man has not trodden, is visited by the cloud, kissed by the falling petal, as, in another sphere, it is the great artists, the Miltons and the Popes, who console not by their thought of us but by their forgetfulness. […] It is only the recumbent who know what, after all, Nature is at no pains to conceal — that she in the end will conquer; heat will leave the world; stiff with frost we shall cease to drag ourselves about the fields; ice will lie thick upon factory and engine; the sun will go out.

This sudden awareness of elemental truth renders the ill person a sort of seer, imbued with an almost mystical understanding of existence, beyond any intellectual interpretation. Nearly a century before Patti Smith came to contemplate how illness expands the field of poetic awareness , Woolf writes:

In illness words seem to possess a mystic quality. We grasp what is beyond their surface meaning, gather instinctively this, that, and the other — a sound, a colour, here a stress, there a pause — which the poet, knowing words to be meagre in comparison with ideas, has strewn about his page to evoke, when collected, a state of mind which neither words can express nor the reason explain. Incomprehensibility has an enormous power over us in illness, more legitimately perhaps than the upright will allow. In health meaning has encroached upon sound. Our intelligence domineers over our senses. But in illness, with the police off duty, we creep beneath some obscure poem by Mallarmé or Donne, some phrase in Latin or Greek, and the words give out their scent and distil their flavour, and then, if at last we grasp the meaning, it is all the richer for having come to us sensually first, by way of the palate and the nostrils, like some queer odour.

Complement this portion of Woolf’s thoroughly fantastic Selected Essays with Roald Dahl on how illness emboldens creativity and Alice James — Henry and William James’s brilliant sister, whom Woolf greatly admired — on how to live fully while dying , then revisit Woolf on the art of letters , the relationship between loneliness and creativity , the creative potency of the androgynous mind , and her transcendent account of a total solar eclipse .

— Published May 6, 2019 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2019/05/06/virginia-woolf-on-being-ill/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture philosophy psychology virginia woolf, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Interpreter of Maladies: On Virginia Woolf’s Writings About Illness and Disability

Gabrielle bellot explores the complexity of detailing sickness in the age of covid.

At the start of 1915, as the First World War raged around her, Virginia Woolf proudly declared in a letter to one of her friends that she had nothing to fear from the flu. “[I]nfluenza germs have no power over me,” she wrote to Janet Case, who had recently come down with the flu; if Janet permitted it, Woolf continued, she would be happy to visit her in person. It was a remarkably ill-timed statement, for Woolf would fall sick with influenza repeatedly over the next decade, at times being confined to her bed as long as eight days. Many of the infections also left Woolf in excruciating physical pain, which was only exacerbated by the extreme surgical measures, like tooth extractions, she occasionally took to alleviate the agony. And the discomfort was not temporary; her physician, Dr. Fergusson, worried that the many bouts of influenza—in 1916, 1918, 1919, 1922, 1923, and 1925—had done lasting damage to her nervous system and heart.

The latter was of particular relevance to Woolf, as her mother had died of heart failure due to complications from influenza in 1895, when Woolf was thirteen. In the early 1920s, a cardiac specialist went so far as to predict that Woolf would soon also die. “I was probably dying,” Woolf confessed to her sister about the severity of the 1919 infection. That that year’s sickness seemed so dire was unsurprising, given the likelihood that she’d contracted the Spanish Flu, the virus that would create the century’s most devastating pandemic, killing tens of millions across the globe.

Still, despite her macabre history with influenza, Woolf still managed to scoff at the pandemic in its early days. In a diary entry from 1918, she off-handedly recorded a neighbor’s succumbing to influenza along with the weather, as if both were equally mundane and unimportant: “Rain for the first time for weeks today, & a funeral next door; dead of influenza.” A few months later, she remarked sarcastically, upon noting that her writerly friend Lytton Strachey was avoiding London due to the pandemic, that “we are, by the way, in the midst of a plague unmatched since the Black Death, according to the Times, who seem to tremble lest it settle upon Lord Northcliffe, & thus precipitate us into peace.” The sardonic tone suggests that Woolf initially viewed the pandemic as a bit of an overblown joke, the comparisons to the plague histrionic.

While ridicule was a common tool of Woolf’s to sneer at things she disliked, she may have had a deeper reason for wanting to deny the lethality of influenza. In part, she likely wanted to avoid the destiny of her mother, whose death had pushed Woolf to the first of the mental breakdowns that would come to constellate her life’s skies. In Woolf’s words, her “infinitely noble” mother was always an “invisible presence” in her life. “[S]he has haunted me,” she said in a 1927 letter.

If her mother was invisibly with her, so, too, was Death, which she described as a similarly invisible, haunting presence in “The Death of the Moth,” a 1942 essay on mortality, in which Woolf watches a moth slowly expire, its legs flailing as if against an “enemy.” Death is the “enemy” here, “indifferent, impersonal,” a foe unseen who none of us, moths or matriarchs, could hope to win against. If the fatal effects of the First World War were obvious—heaps of the dead, bombed buildings, letters to family members indicating that someone was never returning—the pernicious presence of influenza was quieter, less overt, but no less lethal; it, too, was an unseen adversary, ubiquitous and unassuming all at once.

Woolf, it turned out, had no shortage of invisible companions—her mother, the virus that kept attacking her body—and both were linked, in turn, to Death. Death was always with her, the indigo-eyed companion by her bedside, and if the thought of it gave her pain when she thought she, too, was not long for the world, it also gave her solace, because it meant her mother, for all of the ways that she was unlike her daughter, was always near.

As Woolf knew, illness, like trauma, lingers, even after we think we’ve recovered.

In 1925, Woolf also suffered another nervous breakdown, and it, along with her many experiences of influenza, prompted her to write “On Being Ill” the following year, a startling essay about sickness in literature. The piece becomes memorable from its first sentence, a long, luxuriant meditation that is one of my favorite first sentences in nonfiction. “Considering how common illness is,” Woolf writes,

how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us by the act of sickness, how we go down into the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers when we have a tooth out and come to the surface in the dentist’s arm-chair and confuse his “Rinse the mouth—rinse the mouth” with the greeting of the Deity stooping from the floor of Heaven to welcome us—when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.

Here, Woolf achieves two things: she argues that illness has been unfairly dismissed as unworthy of representation in literature, and, before she has even made this argument, she has already proved it by showing the vast range of experiences that illness comprises, the way sickness makes even an otherwise mundane experience seem tinged with Bardic drama, or the rainy-night fire of noir; illness, in other words, contains the grand battles and unmapped tundras and emotions bright-dark as Picasso’s harlequins present in so many books labeled “important,” yet it rarely appears as a main theme.

Illness, Woolf says, is relegated to brief references rather than deep explorations, if it appears at all. “Those great wars which the body wages with the mind a slave to it,” she writes, “in the solitude of the bedroom against the assault of fever or the oncome of melancholia, are neglected. Nor,” she continues, “is the reason far to seek”: it takes bravery and vulnerability, “the courage of a lion tamer,” to defy social mores and write honestly about one’s illness, and, to Woolf, few writers possessed this courage to offend by putting their struggles on full display.

Moreover, Woolf noted that English writers seemed disinclined to write about the body at all, as if it were improper, immoral. Woolf sought a literature that allowed us to write candidly about our body’s experiences. And illness, she proposed, had a startling ability to renew our awareness of the worlds inside and outside of us. In “Art as Technique” (1918), the Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky famously defined the literary technique of defamiliarization, which was to make a familiar thing seem new and strange; sickness, for Woolf, was the great defamiliarizer, causing us to see mundane things, like the sky or a flower, with the awe of a first-timer, because in sickness simple things can suddenly seem incredible once more.

This, in turn, leads us to explore our own selves more deeply, drifting through our Escherian staircases, our orca-dotted seas. In this way, illness becomes a bridge to writing about both ourselves and the world around us more sharply. Illness is itself novelistic, epic, lyric, if we allow ourselves to express its contours.

As a child, I caught countless colds and flus, learning to dread the tickle in my throat preceding a sore throat; later, I was in bed with dengue fever for a week I remember as a haze. I developed a mild case of Covid-19 shortly after New York’s shutdown, losing my sense of smell for a few days. What looms largest in me, though, are the memories of anxiety and depression, the memories of a version of me I wish I could exorcise, but cannot, because they are, like my shadow, inextricable.

Writing openly about sickness is almost always scary—all the more so if you have anxiety, which can make you feel anxious writing about anxiety. And if you’re a trans woman of color, like me, you begin to fear revealing too much about your struggles with mental illness, in particular, even comparatively light cases like my own, because you know that many people will simply take your revelations as proof that people like you are disturbed dangers to wholesome, “normal” white folks like themselves. It is common, after all, for critics of trans people to deny the reality of our experiences or the urgency of transitions by claiming we are “mentally ill,” suggesting that we are too deluded to understand anything about ourselves.

To write about your illness—bodily or mental, because each amplifies the other—is to risk having your experience weaponized against you.

But I do it anyway, because it is more freeing than not.

I have heard the crackle of anxiety for most of my life, dull, soft, then unexpectedly loud, like the crackle of a drag on a clove cigarette in a pink evening. I have heard its jazzy electricity, a soft discordant constant like the buzz of an old diner’s neon sign but with sudden spikes in volume, sudden whorls and whirls. Most of the time, I can live with it, even forget its noise, but it is always there, a constant undercurrent in the background of the self, threatening to rise like Hokusai’s wave and take me with it, and every so often it does, reducing me to a crying wreck, to a howl lonely and loathing as the bellows of the sea-beast in Bradbury’s “Fog Horn,” to shame at your weakness, and this is when it becomes so easy to step into the soft grey quicksand of depression, to sink into that emptying space where you stop feeling at all, and begin to want to end it all, because you fear you are worth as little as you feel when the grey has sapped you of your colors. I know it well, know how the grey once made me want to swallow poison, once got me to go to a train station to step in front of a C train to end my life, made me for years casually hear kill yourself while doing dishes or reading.

I control it all better now. I rarely sink into depression’s stone pools, and my anxiety is a softer hum. But the fear of them lingers. I still feel nervous sharing that I deal with either, because even if you exist just fine 98 percent of the time, all it takes is that other 2 percent to make someone look at you different, back away with an awkward smile, and begin to treat you like someone they cannot be themselves around anymore, if they want to be around you much at all.

Have an outburst when life is genuinely stressful, and you are pathologized; cry in front someone because you, too, are haunted by the ghost of your mother, who is still alive but has never loved you the same since you came out as trans, and you fear being pathologized. You become your struggles, become a mind-body problem that cannot be solved.

I am still learning, like Woolf, how to reveal.

One of the few books that did center illness, in Woolf’s estimation, was Thomas de Quincey’s famously hallucinatory classic, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821). De Quincey was also aware of how rarely the English, in particular, allowed themselves to talk about illness, and so he prefaced his book with a wry note to readers about the English dismissing narratives about the sick as nothing less than immoral. He begins by apologizing for

breaking through that delicate and honourable reserve which, for the most part, restrains us from the public exposure of our own errors and infirmities. Nothing, indeed, is more revolting to English feelings than the spectacle of a human being obtruding on our notice his moral ulcers or scars. . .

To write about one’s addictions and pains—one’s illness, in another word—was “revolting,” an obtrusive “spectacle”; de Quincey, like Woolf, sought to do away with that puritanical line of thinking. And, as he notes later in the preface, it was also hypocritical, given the large numbers of English people who took opium in secret, but would rail with the Manichaean fury of a preacher against anyone actually writing openly about drug use and addiction.

De Quincey’s sentences capture some of the surrealism of taking laudanum, and Woolf’s essay, similarly, has a beautiful, deliberate style. “On Being Ill” is a slow burn, its sentences long, languid, and curlicued like dreaming’s rivers, and it is difficult not to feel drawn in by its lushness. Woolf’s essay is not straightforward, and critics of medical literature have taken her to task for this in the few times her essay has received attention, arguing that her points are weakened by the circuitousness of her style.

But this criticism misses the larger point. Woolf didn’t want to create a simple, straightforward argument; her essay’s style itself is a part of the argument. It captures, in its richest moments, the feelings we may have when bedridden: the disorientations, the sudden fascinations with mundane things, the rock-peppered streams of consciousness. The essay’s imagery is constantly in flux, as if, in a bit of metatextual genius, to capture the hazy, Heraclitean impressions of being sick itself.

Rather than create a direct set of points, Woolf reveled in what Keats famously termed negative capability: uncertainty, the in-between spaces that, for some critics of nonfiction , partly define essays as a genre. An essay can be an essay, in the definition of “essay” that means “an attempt”; an essay functions perfectly well as an attempt to get at an idea, rather than needing to have a clear, linear polemical path. Essays can make clear arguments; they’re also quite free to suggest rather than say explicitly, free to wander the wilds.

Beyond this, Woolf linked style to gender, with different forms of description indicating something about how one sees the world. She defined these categories in characteristic Woolfian fashion in one of her most playful short stories, “The Mark on the Wall,” in which two characters—the narrator implied to be a woman and the other a man—respond to an unidentified mark on the wall quite differently. For the narrator, not knowing what the mark is inspires a series of surreal associations, and she revels in the uncertainty because it is enjoyable to speculate; the man, however, sees the dot and immediately labels it nothing but a snail, bringing the story, and the imaginativeness, to an abrupt end.

For Woolf, this difference mattered. Blunt, abrupt, direct sentences that declare, with certainty, what something is represented “the masculine point of view,” while longer, more imaginative, uncertainty-privileging sentences were “feminine.” The narrator dislikes the speculation-ending masculine point of view, “which soon, one may hope, will be laughed into the dustbin where the phantoms go.” Style, then, is substance, is spirit, is Weltanschauung. “On Being Ill” privileges this roving style, so that you don’t just say, “I have influenza” and leave it there, but show what it feels like.

Woolf’s concerns also animated the critic Elizabeth Outka, whose Viral Modernism (2019), a study of the 1918 pandemic in Modernist literature, came out, appositely, just before our own generation’s pandemic. In a moment of macabre insight, Outka notes that “certain types of mass death become less ‘grievable’… than others, with deaths in the pandemic consistently seen as less important or politically useful. The millions of flu deaths,” she continues, “didn’t (and don’t) count as history in the ways the war casualties did.” Outka’s study seeks to answer a curious question: why the pandemic, despite its staggering scope, so rarely seems to appear in Modernist literature of the period. In reality, the pandemic is there, in both passing references and even, arguably, in some of the disorienting, fragmentary stylistic choices of the era, which may reflect the hallucinatory experience of severe influenza. Yet it is all too easy to take a course on Modernism with only a passing nod to the pandemic, if you get that at all, while the First World War, which helped amplify the virus’ spread, will always be discussed.

This happens even in discussions of Woolf’s other overtures to illness, like her celebrated novel Mrs Dalloway , which mentions influenza but is rarely spoken of as a pandemic novel. Here, too, the war takes critical precedence: critics have overwhelmingly focused on Septimus, the shell-shocked soldier, as the book’s image of trauma, often ignoring that, in Outka’s words, Clarissa is a “pandemic survivor” who deals with “lingering physical and psychological damage” from influenza. (Septimus, however, may also have been lastingly affected by the virus, Outka speculates, given its prevalence amongst soldiers and his delirium-like symptoms.) Clarissa is described early on as having “her heart affected…by influenza,” like Woolf and her mother; her grand joy at going out to get the flowers herself, the desire that starts the novel, suggests that her sickness prevented her from leaving her home before then, a detail darkly reminiscent of the coronavirus pandemic’s psychological effects on the quarantined.

A part of the problem, Outka says darkly, is a tendency to sweep away illness as less noteworthy than, say, a war, and this desire is tied to gendered norms of what is casually considered “important,” whereby war, a stereotypically “masculine” activity, takes precedence over almost all else. While I dislike following norms of gender, it’s difficult not to see these tendencies at play in discussions of Woolf’s era. “When we fail to read for illness in general and the 1918 pandemic in particular,” Outka writes in a memorable passage,

we reify how military conflict has come to define history, we deemphasize illness and pandemics in ways that hide their threat, and we take part in in long traditions that align illness with seemingly less valiant, more feminine forms of death.

Thankfully, this is beginning to change, thanks to books whose authors put their struggles with illness front and center, like Sick , Porochista Khakpour revealing memoir of Lyme Disease; The Collected Schizophrenias , Esme Wang’s intense, intimate essays on living with mental illness; My Year of Rest and Relaxation , the by-turns-humorous-and-harrowing novel by Ottessa Moshfegh about intersections between mental illness, privilege, and American society; or Kaveh Akbar’s astonishing poems of addiction, Portrait of the Alcoholic . These books, alongside so many others, place illness of one kind or another at the forefront, allowing readers not just to observe but to feel what it is like to be sick—and there’s something beautiful amidst the poignancy in this vulnerability.

Yet it is still difficult to be taken seriously once you admit—or confess, as de Quincey did—to having to struggle with something, and it is clear that some of that old desire to simply not have us dirty up a narrative with our illnesses. It’s worse, still, for those of us who are nonwhite and trans in America, when our revelations merely reinforce racist and transphobic stereotypes about our stability, our danger to others, or the very validity of our thoughts.

We have come far—but we’re far from where we need to be, all the same, when Woolf’s essay still has the power to seem subversive.

Our pandemic is both similar to and distinct from the one Woolf lived through. The Spanish Flu was horrifically devastating, its death toll amplified significantly by soldiers from the First World War bringing the virus with them as they traveled. The coronavirus is also destructive (though unquestionably less so), but we have better medical tools to deal with it now, and its death toll will almost certainly be lower, though no official toll can grasp how many have truly died, in Woolf’s day or ours, because the reach and ramifications of a pandemic are almost always wider than we can comprehend.

This pandemic will end—possibly even sooner than we may think—but it will not end all at once. Instead, as in Camus’ The Plague , the effects that this period has had on us will linger, even if we don’t fully realize how deeply we’ve been affected. Although we will be able to return to something like normalcy one day, due to a scientific miracle of speed in vaccine production that we must never take for granted, we won’t return to exactly what we were before; we will have changed, because this pandemic has changed all of us, even those who claim there is no pandemic at all. Some of the changes, to ourselves and societies, may be good, helping to show the work for equal access to healthcare and financial aid that urgently needs to be done.

Other changes, however, may even seed future pandemics, like the non-immunocompromised people who claim they will never stop wearing a mask or let their kids go anywhere unmasked even after vaccination, a practice that would obviously harm their immune systems in the long run. Egos on social media, stoked already by sanctimonious bragging tweets about, say, how many masks they own, may simply enlarge further as they brag about, say, not taking a coronavirus vaccine, a position that—if the vaccines are shown to work—will amount to anti-intellectualism for “likes” that lengthens the span and death toll of this pandemic, or the next.

Regardless of all this, whenever the pandemic is over, we must practice a deeper form of self-care—be it through celebration or separation for a little longer—than we’ve ever done before to begin to really heal. As Woolf knew all too well, illness is itself a kind of invisible presence in our lives even when we think we’ve recovered.

How we speak of pandemics matters, too. Woolf used militaristic imagery in “On Being Ill”; sickness was a grand “war.” This is how so many in power have described our relationship with the coronavirus: a battle to be won. But this is wrong. The coronavirus is simply another entity (almost an organism, though viruses aren’t quite alive) we live in relation to, and that our species has always lived in relation to since we happened to evolve, on our pale blue planetary dot. Viruses do not likewise “see” us as enemies; we are simply means of propagation, the coronavirus no different in this sense from any other. And viruses far outnumber humans—and all other organisms—on Earth.

But this isn’t cause for alarm; it’s always been this way. We do not win against viruses; we live with them always at the door of our worlds. If we kick one out into the obsidian of the past, lovely; others will always be there, prolific as the microbes we carry around inside us every day. Pandemics will likely never stop occurring—and this is scary, yes, but it doesn’t have to outright petrify us, because this is merely the social contract of life, the natural contract, we sign when we are born. It’s easy to forget how fragile we are, how extraordinary it is that humankind has survived as long as it has. But we have, through plagues and pandemics, and will continue to, somehow, because that’s what we do—and that’s kind of incredible, really.

When we stop thinking about defeating viruses like enemies, we can better appreciate our tenuous place on this planet and learn to cherish the brief time we have, in sickness and health alike. Woolf understood well the smallness and precariousness of humankind in the grand scheme of things, but she kept going, anyway, so that she could write—the thing she loved—even with the agony of mental and physical illnesses as her backdrop, for as long as she could muster the urge to keep living. As much as we can, we will survive by doing the same, focusing on what and who we love, no matter how near Death, our invisible companion, seems.

Gabrielle Bellot

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Black Voices

- Female Voices

- LGBTQ Voices

- Diverse Voices

- Author Interviews

- Bookstr Talks

- Second Chapter

- Featured Authors

7 Fictional Couples That Match These Elizabeth Browning Quotes

Unveiling Sapphic and Lesbian: Exploring Their Mythological Origins

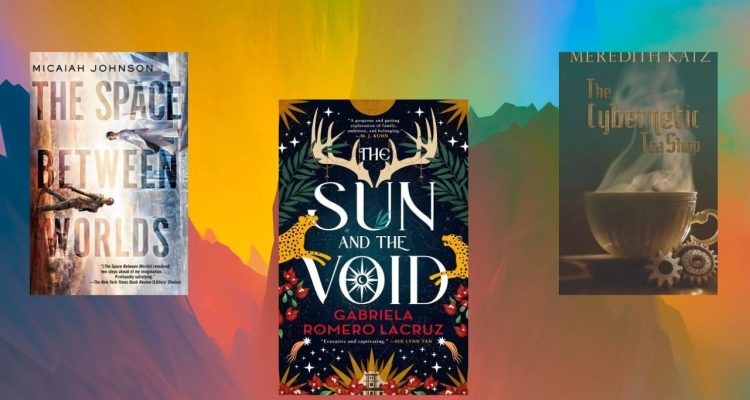

Exploring Queer Sci-Fi and Fantasy: Beautiful Worlds and Diverse Narratives

5 Excellent Psychologist Writers Discuss the Importance of Mental Health

- On This Day

- Bookspot / Libraries

- Bookstagram

- Bookish Memes

- Bookish Trends

- Favorite Quotes

The Bookstr Teams’ Favorite Cinnamon Roll MMC That We’d Love To Hug

Half Way Check In: Bookstr Team’s Greatest Reads So Far This Year

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Just For Fun

- Adaptations

9 Sure-Fire Sizzling Romances for Log Cabin Lovers

See Which Lovable Fictional Pet Is Your Real-Life Sidekick! Quiz

Chose the Best Albums, Get Paired With a Timeless Poetry Book! Quiz

- Food & Wine

- Art and Music

- Partner Articles

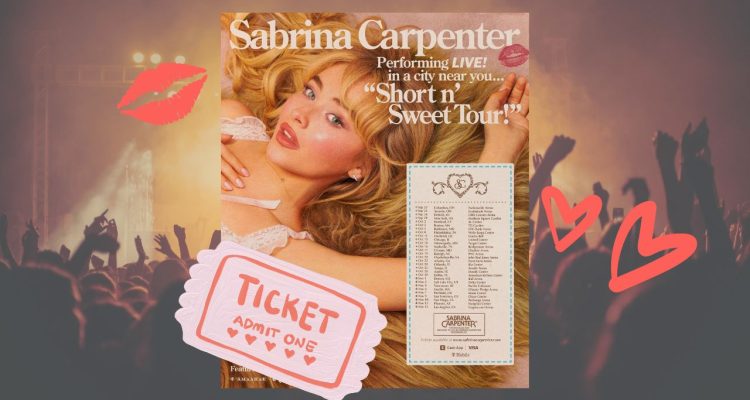

Sabrina Carpenter Is Working Late on Her New Tour

Breaking Toxic Masculinity: Powerful Prose That Overcomes Emotional Repression

Books With a Beat: New Releases on Famous Artists

- Young Readers

- Science Fiction

- Poetry & Drama

- Thriller & Mystery

- Young Adult

- Three To Read

- Female Authors

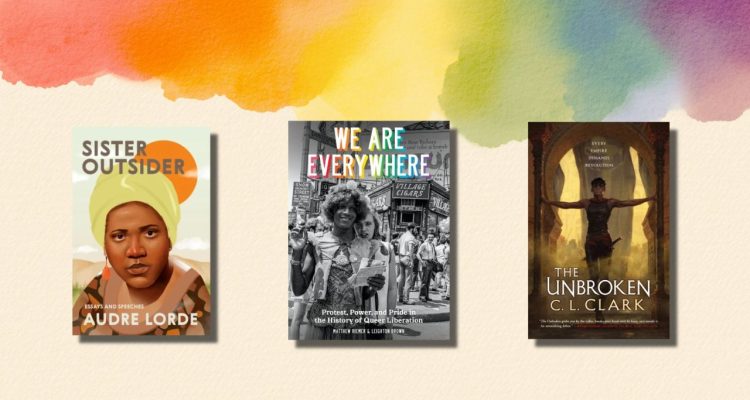

9 Must-Reads To Extend Your Pride Month TBR All Summer

9 Amazing Classic Short Stories To Stimulate the Mind This Summer

Summer Slashers: 13 Campy Horror Stories To Make You Scream

For the love of books

Beyond Words: A Look At Virginia Woolf’s ‘On Being Ill’

In continued observance of Chronic Disease Awareness Month, let’s discuss one of Virginia Woolf’s most thought-provoking, insightful essays: “On Being Ill.”

Virginia Woolf is particularly famed in the literary world for her pioneering of the stream-of-consciousness narrative. Indeed, she had an incomparable talent for translating the organic flow of thought onto the page. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that she tackled one distinct theme that frustratingly tends to go beyond words: illness.

Woolf was no stranger to life’s ups and downs of well-being. She struggled long-term with her mental health, recurrent migraines, and successive bouts of influenza. The latter was the impetus behind Woolf’s profound essay, “On Being Ill,” which she penned in 1925 at age 42.

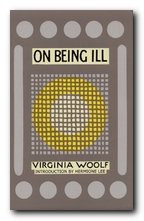

The essay was first published in early 1926 in T.S. Eliot’s The Criterion . Then, years later, it was published again in Woolf’s own Hogarth Press as a standalone piece. The first edition cover, designed by her sister, Vanessa, can be seen below.

Illness As A Literary Theme

The principal object of Woolf’s essay addresses the need for illness to stand as a core literary theme. Her opening sentence notes the very universal takeaway of “how common illness is,” thus inquiring into why the literary world explores it so little.

It becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love, battle, and jealousy among the prime themes of literature. Novels, one would have thought, would have been devoted to influenza; epic poems to typhoid; odes to pneumonia, lyrics to toothache Virginia Woolf, “On Being Ill”

Lucidly, when it comes to the human condition, illness is an inescapable reality for all individuals at some point. We’ve all had a particularly horrible flu season, stomachache, injury, etc. Not to mention the tumultuous, ongoing navigation of a global pandemic (Woolf, herself, lived through the 1918 pandemic).

From Woolf’s standpoint, the perpetual avoidance of addressing illness, despite its universality, is tied to the vulnerability it induces in us. In the essay, Woolf relays that there is this “childish outspokenness in illness.” It temporarily removes us from our accustomed state of agency in the world and over our own lives.

As someone who has been shakily traversing life with a chronic illness for three years, I must concur that illness condenses oneself to the moment in a very harsh but internally revealing way. According to Woolf, this vulnerability accompanying illness is not something to run and hide from but something to lean into. Why? Because it engenders a very unique state of mind, where our external circumstances slow down, where life gets quiet. In short, it’s a state that leaves us solely alone with ourselves.

This is the situation Woolf herself was in when she wrote “On Being Ill,” confined to her bed and tuned in to her mind in a visceral way. Clearly, it was a state in which she thought most profoundly and succeeded in bringing the resonant truths of human experience to light.

Mind and Body

With pen in hand, writers walk a line between tuning out the world and being hyperaware of everything around them. Virginia Woolf’s essay testifies to this balance in an extraordinary way.

All of Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness prose reveals an astute observance of the world around her. At the same time, she indulges this insular quality of the mind, this peaceable solitude. Most important to her commentary on illness is the recognition that mind and body are far from separate. The way our body feels (or, rather, suffers) affects our mind. We don’t perceive and process our maladies distantly and objectively. Therefore, per Woolf’s argument, literature should recognize that connection rather than try and emphasize this false sort of dualism.

Literature does its best to maintain that its concern is with the mind; that the body is a sheet of plain glass through which the soul looks straight and clear, and, save for one or two passions such as desire and greed, is null, negligible, and non-existent. On the contrary, the very opposite is true. All day, all night the body intervenes; blunts or sharpens, colours or discolours, turns to wax in the warmth of June, hardens to tallow in the murk of February. But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record. Virginia Woolf, “On Being Ill.”

The missing literary record of these swings between “health and illness,” which constitute life as we know it, was something Woolf wanted to draw attention to. In many ways, she was the perfect voice to do so, given her personal health experiences and her resounding talent for capturing the nature of thought in her stream-of-consciousness style.

Illness and Language

Undoubtedly, within Woolf’s essay, there is a challenge to be found. She recognizes that one part of the literary hindrance in earnestly writing about illness is that “there is the poverty of the language.” It is invariably difficult to describe our pain in a way that feels satisfactory. Complete. In many ways, it is something we can never fully communicate and share with another person. Therein lies the trouble, but also a call to revitalize how we think about illness and evolve “a new language” of the body and mind that best translates the complexity of “being ill.”

To conclude, if there’s one line from Woolf’s essay that particularly stuck out to me in navigating my own health struggles, it would be that “In illness, words seem to possess a mystic quality.” I have long felt, when my health was at its worst, that words were my lifeline. Language serves as my tether to the moment and the ultimate gateway to understanding and expressing myself.

Writers like Woolf emphasize the importance of undertaking the literary challenge of unabashedly addressing and exploring topics that, too often, go beyond words. In many ways, that is the main roadblock of the human experience – the inability to feel fully and completely understood. However, Woolf gives us the inspiration to tackle that roadblock by leaning into the interlocking dynamic of mind and body, which holds a magnitude of inner truths vital to the literary canon.

Finally, for more reading recommendations spotlighting chronic disease awareness, click here .

To read about my personal experience on the mind/body connection when managing a chronic illness, please click here .

FEATURED IMAGE VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Love Bookish Content?

Be the first to our giveaways, discover new authors, enjoy reviews, news, recommendations, and all things bookish..

No thanks, I'm good for now.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- On Being Ill: with Notes from Sick Rooms by Julia Stephen

In this Book

- Virginia; Stephen Woolf

- Published by: Wesleyan University Press

- View Citation

Table of Contents

- Half-Title Page, Title Page, Copyright

- Publisher's Note

- Jan Freeman

- On Being Ill

- Introduction

- Hermione Lee

- pp. xi-xxxvi

- Virginia Woolf

- Notes from Sick Rooms

- Mark Hussey

- Julia Stephen

- Rita Charon

- pp. 109-116

- About this Edition

- pp. 117-118

- Biographies

- pp. 119-124

Additional Information

Project muse mission.

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

On Being Ill

- Related content

- Peer review

- Barry Newport , part time sessional GP (former GP principal), Wokingham, Berkshire

- barry.newport{at}yahoo.co.uk

In this essay Virginia Woolf examines the spiritual change that a minor feverish illness such as flu can bring, enhancing our perception of the world while normal society goes on without us. “Directly the bed is called for we cease to be soldiers in the army of the upright; we become deserters. Mrs Jones catches her train. Mr Smith mends his motor. Men thatch the roof, the dogs bark.” Meanwhile the recumbent can study nature, indifferent but comforting, finding new beauty in “the …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

2017 Essays

Revaluing Illness: Virginia Woolf’s “On Being Ill”

Lau, Travis

"Synapsis: A Health Humanities Journal" was founded in 2017 by Arden Hegele, a literary scholar, and Rishi Goyal, a physician. Its mission is to develop conversations among diverse people thinking about medical and humanistic ways of knowing ... as a “Department Without Walls” that connects scholars and thinkers from different spheres.

- Social sciences

- Interdisciplinary research

- Medical care

Also Published In

More about this work, related items.

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

Writing on mental illness: why Virginia Woolf inspires me

T his article deals with themes of suicide, suicidal ideation, bipolar, anorexia and family death

I n Mrs Dalloway , published just under a century ago, Virginia Woolf famously wrote how “the world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames”. Today, 98 years later, anyone who has struggled with mental illness (particularly anxiety or PTSD) can recognise their perception of the world in this metaphor. Woolf, plagued by a “nervous disorder” throughout her life until she committed suicide at age 59, understood what it meant to live in the throes of “madness” and her struggle was a central theme of her written works — both factual and fictional. To mark the end of Mental Health Awareness Week, I’ll be reflecting on this monumental author and the uphill battle (against illness, tragedy, and society) she fought throughout her life.

Academics and biographers have speculated on what mental illnesses Woolf might have been diagnosed with if she was still alive today. It’s widely agreed she had bipolar disorder, her life being divided into periods of paralysing depression and extreme mania, often accompanied by psychotic episodes. Insomnia, grief, and suicide ideation had all become mundane by the time Woolf reached adulthood. Her biographical essay On Being Ill reflects on how these symptoms have caused her to perceive the world differently, (demonstrated in the surreal nature of her novels), and tenderly reveals the terrible loneliness of lifelong sickness.

Writing wasn’t just an escape from the mental pain Woolf experienced, it also made it possible to process her difficulties. By transforming what she had witnessed into words, Woolf wrote she was able to strip them of the power they had to hurt her .

While Woolf is constantly drawn to death — making several suicide attempts during her lifetime — she is also terrified by her knowledge of it, having lost her most beloved family members as a young girl.

The release of death she idolised (her protagonist is comfortably “curled up at the bottom of the sea” following her death in The Voyage Out ) and the devastating grief with which she lived (we remain with her raw, aching husband) are in constant conflict throughout her books. While Woolf is constantly drawn to death — making several suicide attempts during her lifetime — she is also terrified by her knowledge of it, having lost her most beloved family members as a young girl.

Mrs Dalloway translates the ebbs and flows of the human mind, moving between past, present, and future in a way that conflates them, and weaves together a narrative that follows a stream of consciousness. The structure of her novels was revolutionary for English literature, breaking traditional formulas, and drew on Woolf’s own perception of the world. Rhetorically, Woolf argues against the traditional style of novels written at the time: “Is life like this?”

Her writing style often reflects the hypomanic state she wrote in, a state which causes enhanced vocabulary, inventiveness, and the ability for sustained concentration. Author Marya Hornbacher reflects on the mania of bipolar in her biography, Madness : “I can’t say no, I can’t slow down, I have to keep going or they’ll find out I’m… a fraud”. This urgency to write, or risk falling apart again, is evident behind the writing of both authors.

Her repulsion towards eating, as well as her body’s desperate, biological urges to rebel against her, is obvious in this characterisation of hunger.

A descendant of Woolf has also highlighted her reoccurring bouts of anorexia, documented by her husband: he wrote during one of her breakdowns that “the most difficult and distressing problem was to get Virginia to eat”. Emma Woolf, who published a memoir about her own life with anorexia, said she experienced a “painful moment of recognition” when looking at photographs and writing from her great aunt. Food and consumption crop up repeatedly in Virginia Woolf’s writing, seen with the disgusting beast inside of every man who “gobbles and belches… jibs if I keep him waiting” in The Waves . Her repulsion towards eating, as well as her body’s desperate, biological urges to rebel against her, is obvious in this characterisation of hunger.

In addition to being institutionalised, Woolf was repeatedly prescribed a “rest cure” by her doctor, consisting of a strictly enforced regime of six to eight weeks of bed rest and isolation, without any creative stimulation. As woman whose two greatest loves were to walk and to write, the treatment drove her to frustration every time she underwent it. Her writing strains against the metaphorical corset, criticising how women were restricted by patriarchal society and how Woolf was restricted personally by the men who cared for her. Popularity in her novels was revived during second-wave feminism in the 1960s, examining and analysing Woolf’s writing from a feminist perspective.

Although Woolf was hounded by illness throughout her life, she was able to produce some of the greatest novels and most insightful personal essays ever written. Her legacy has resulted in her becoming a figurehead of both feminist literature and those musing on mental health, in addition to facilitating more interest in her personal life than any other writer. While I don’t agree with the idea that mental anguish is a necessary tool for creatives, it can’t be denied that Woolf’s struggles formed the core of her work and they would be very different if she had lived a happy, carefree life. Woolf reminds us that we are worthy rivals, able to combat our mental illnesses and create in spite of them, as long as we favour the pen over the sword.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Geopolitics

- Computer Science

- Health Science

- Exercise Science

- Behavioral Science

- Engineering

- Mathematics

Virginia Woolf’s Mental Illness And Literary Contributions: Unraveling The Connection Between Depression And Artistic Expression

Virginia Woolf was a groundbreaking writer and a prominent figure in the modernist movement. Her novels, essays, and short stories were characterized by their unique style and their exploration of complex themes such as gender, class, and identity. However, Woolf was also known for her struggles with mental illness, particularly depression. In this article, we will explore the connection between Virginia Woolf’s mental illness and her literary contributions, as well as the legacy of her work in relation to mental health.

How did Virginia Woolf’s mental illness affect her writing?

Virginia Woolf began experiencing symptoms of mental illness as early as her teenage years, and her struggles with depression and anxiety continued throughout her life. In her writing, Woolf often conveyed feelings of isolation, despair, and a sense of disconnect from reality. For example, in her novel “Mrs. Dalloway,” the protagonist Clarissa experiences a sense of emptiness and a fear of madness, similar to Woolf’s own struggles.

However, Woolf’s mental illness also had a profound impact on her writing style. She experimented with stream-of-consciousness narration, which allowed her to convey the deeply personal and often chaotic thoughts and emotions of her characters. This technique is evident in her novel “To the Lighthouse,” which is considered one of her most innovative works.

Despite the challenges she faced, Woolf’s mental illness also served as a source of inspiration and creativity. As she once wrote, “I can only note that the past is beautiful because one never realizes an emotion at the time. It expands later, and thus we don’t have complete emotions about the present, only about the past…”

What is the link between depression and creativity?

The relationship between depression and creativity has been the subject of much debate and research. While there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that depression is a prerequisite for artistic expression, many artists and writers have spoken about the ways in which their mental health struggles have informed their work.

A study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that individuals with depression showed heightened creativity in tasks such as problem-solving and brainstorming. This may be due to the fact that depression can lead to a more introspective and reflective state of mind, which in turn can fuel creative thinking.

How did Woolf address mental illness in her work?

Throughout her writing, Virginia Woolf explored the complex and often stigmatized topic of mental illness. In her novel “Mrs. Dalloway,” for example, she portrays the character of Septimus Smith, a World War I veteran who is suffering from shell shock. Through Septimus’s experiences, Woolf portrays the devastating effects of mental illness and the societal pressures that prevent individuals from seeking help.

Woolf’s essay “On Being Ill” also addresses the topic of illness, both physical and mental. In the essay, she argues that illness should not be dismissed as a trivial or insignificant experience, but rather recognized as a powerful force that shapes our lives and our perceptions of the world.

What is the legacy of Virginia Woolf’s literary contributions in relation to mental illness?

Virginia Woolf’s literary contributions have had a lasting impact on the way we understand mental illness and its portrayal in literature. Her use of innovative narrative techniques and her candid exploration of mental health struggles paved the way for other writers to address this topic in their work.

In addition, Woolf’s legacy has inspired a new generation of scholars and activists to advocate for more nuanced and compassionate approaches to mental health. As she once wrote, “So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters; and whether it matters for ages or only for hours, nobody can say.”

- “Creativity and mood disorders: A systematic review”

Christophe Garon

June 19, 2023

Psyche , Psychology

Comments are closed.

Follow Me On Social

Stay in the loop, recent posts.

- The Enigma of Ultraluminous X-Ray Sources: Decoding the Mystery of Super-Eddington Accretion

- Kaaret Ultraluminous X-Ray Sources: A Closer Look at ULXs and Super-Eddington Accretion

- Harry Potter and the Goblin Bank of Gringotts: Financial Stability Study

- Examining the Impact of Gringotts Wizarding Bank on the Wizarding Economy

- Improving ASR Accuracy Through Neural Network Methods: Understanding Pronunciation Variations

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

© 2024 Christophe Garon — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Rash Reading: Rethinking Virginia Woolf's On Being Ill

- PMID: 31402342

- DOI: 10.1353/lm.2019.0001

Virginia Woolf's On Being Ill (1926) is the first published essay in English on illness in literature. Historically neglected, in recent years rising popular and academic interest in the intersection of illness and the arts has led to a rediscovery of sorts, exemplified by its republication by Paris Press in 2002 and 2012. And yet, in spite of this surge in attention, contemporary writers and scholars routinely undervalue the scope of Woolf's argument about illness and its literary representation. By placing On Being Ill within a wider context of writing and reading illness in the modern and contemporary period, my study opens up hitherto unexplored dimensions of the essay, arguing for a more expansive understanding of the critical and creative interventions it seeks to make, and a new appreciation of its relevance to present day debates around the meaning and value of illness in literature.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- ['Writer of the soul' - Virginia Woolf's bipolar disorder in light of her life story and traumatization]. Bélteczki Z, van der Wijk I, G Tóth A, Rihmer Z. Bélteczki Z, et al. Psychiatr Hung. 2023;38(4):385-396. Psychiatr Hung. 2023. PMID: 38306254 Review. Hungarian.

- Depressing time: Waiting, melancholia, and the psychoanalytic practice of care. Salisbury L, Baraitser L. Salisbury L, et al. In: Kirtsoglou E, Simpson B, editors. The Time of Anthropology: Studies of Contemporary Chronopolitics. Abingdon: Routledge; 2020. Chapter 5. In: Kirtsoglou E, Simpson B, editors. The Time of Anthropology: Studies of Contemporary Chronopolitics. Abingdon: Routledge; 2020. Chapter 5. PMID: 36137063 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- A Lexicon for the Sick Room: Virginia Woolf's Narrative Medicine. James E. James E. Lit Med. 2019;37(1):1-25. doi: 10.1353/lm.2019.0000. Lit Med. 2019. PMID: 31402341

- Potential use of text classification tools as signatures of suicidal behavior: A proof-of-concept study using Virginia Woolf's personal writings. de Ávila Berni G, Rabelo-da-Ponte FD, Librenza-Garcia D, Boeira MV, Kauer-Sant'Anna M, Passos IC, Kapczinski F. de Ávila Berni G, et al. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 24;13(10):e0204820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204820. eCollection 2018. PLoS One. 2018. PMID: 30356303 Free PMC article.

- "Unborn selves"--literature as self-therapy in Virginia Woolf's work. Iszáj F, Demetrovics Z. Iszáj F, et al. Psychiatr Hung. 2011;26(1):26-35. Psychiatr Hung. 2011. PMID: 21502669

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Tutorials, Study Guides & More

On Being Ill

January 26, 2013 by Roy Johnson

poetic meditations on illness and consciousness

On Being Ill (recently re-issued) is a timely reminder that not only was Virginia Woolf a great novelist and writer of short stories, she was also an essayist of amazing stylishness and wit. Her models were the classical essayists of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century – Addison, Steele, Hazlitt, and Lamb – all of whom she had read during her literary apprenticeship, which took place in the library of her father, Sir Leslie Stephen .

On Being Ill starts from the simple but interesting observation that although illness is a common, almost universal experience, it is surprisingly absent from literature as a topic of interest. This is rather like her similar observation about the absence of women in the annals of literature which led to her epoch-making study A Room of One’s Own . From this starting point she then spins out an extraordinary display of reflections on a series of related topics including solitude, reading, and language. And, as Hermione Lee observes in her excellent introduction to this edition, she also throws in ‘dentists, American literature, electricity, an organ grinder and a giant tortoise’ plus lots, lots more.

Much of her reflections are conveyed in long, rococo sentences in which disparate elements are yoked together by her associative thought processes and her majestic command of English. Musing on the fact that illness renders people horizontal, giving them the unusual opportunity to look up into the sky, she observes:

Now, lying recumbent, staring straight up, the sky is discovered to be something so different from this that really it is a little shocking. This then has been going on all the time without our knowing it!—this incessant making up of shapes and casting them down, this buffeting of clouds together, and drawing vast trains of ships and wagons from North to South, this incessant ringing up and down of curtains of light and shade, this interminable experiment with gold shafts and blue shadows, with veiling the sun and unveiling it, with making rock ramparts and wafting them away—this endless activity, with the waste of Heaven knows how many million horse power of energy, has been left to work its will year in year out. The fact seems to call for comment and indeed for censure. Ought not some one to write to The Times ? Use should be made of it. One should not let this gigantic cinema play perpetually to an empty house.

The style is deliberately playful, the attitude arch, and yet those two references, to ‘horse power’ and ‘cinema’ show how acutely aware she was of the technology and media which were shaping the twentieth century.

The essay is accompanied in this very attractive new edition by Notes from Sick Rooms , written by her mother Julia Stephen in 1883. The juxtaposition of the two texts is very telling. It is usually assumed that the major literary influence on Virginia was her father, the biographer (and explorer and editor). But you can certainly see where the daughter inherited the fancifulness and lightness of touch in her mother’s essay on the annoying effect of crumbs in the bed of a sick person.

Among the number of small evils which haunt illness, the greatest, in the misery it can cause, though the smallest in size, is crumbs. The origin of most things has been decided on, but the origin of crumbs in bed has never excited sufficient attention among the scientific world, though it is a problem which has tormented many a weary sufferer.

The inflation (‘evil’) and comic hyperbole were alive and well in her daughter’s work, written forty-three years later.

The essay even has an interesting history. It was first published by T.S.Eliot in his magazine The Criterion in 1926, alongside contributions from Aldous Huxley, Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, and D.H.Lawrence’s The Woman Who Rode Away . Then it was republished as a single volume by the Hogarth Press in 1930. This new edition reproduces the original with its idiosyncratic capitalisation, and is nicely illustrated with chapter dividers and inside covers by Vanessa Bell. Both essays have scholarly introductions, and the book even has an afterword on the relationship between narrative and medicine.

© Roy Johnson 2013

Virginia Woolf, On Being Ill . Massachusetts: Paris Press, 2012, pp.122, ISBN: 1930464134

Get in touch

- Advertising

- T & C’s

- Testimonials

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

Virginia Woolf Was More Than Just a Women’s Writer

She was a great observer of everyday life..

Virginia Woolf, in one of the more lively and often-seen photos of her from the 1930s.

HIP / Art Resource, NY

Virginia Woolf, that great lover of language, would surely be amused to know that, some seven decades after her death, she endures most vividly in popular culture as a pun—within the title of Edward Albee’s celebrated drama, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? In Albee’s play, a troubled college professor and his equally pained wife taunt each other by singing “Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Wolf?,” substituting the iconic British writer’s name for that of the fairy-tale villain.

The Woolf reference seems to have no larger meaning, but, perhaps inadvertently, it gives a note of authenticity to the play’s campus setting. Woolf’s experimental novels are much discussed within academia, and her pioneering feminism has given her a special place in women’s studies programs across the country.

It’s a reputation that runs the risk of pigeonholing Woolf as a “women’s writer” and, as a frequent subject of literary theory, the author of books meant to be studied rather than enjoyed. But, in her prose, Woolf is one of the great pleasure-givers of modern literature, and her appeal transcends gender. Just ask Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours , the popular and critically acclaimed novel inspired by Woolf’s classic fictional work, Mrs. Dalloway .

“I read Mrs. Dalloway for the first time when I was a sophomore in high school,” Cunningham told readers of the Guardian newspaper in 2011. “I was a bit of a slacker, not at all the sort of kid who’d pick up a book like that on my own (it was not, I assure you, part of the curriculum at my slacker-ish school in Los Angeles). I read it in a desperate attempt to impress a girl who was reading it at the time. I hoped, for strictly amorous purposes, to appear more literate than I was.”

Cunningham didn’t really understand all of the themes of Dalloway when he first read it, and he didn’t, alas, get the girl who had inspired him to pick up Woolf’s novel. But he fell in love with Woolf’s style. “I could see, even as an untutored and rather lazy child, the density and symmetry and muscularity of Woolf’s sentences,” Cunningham recalled. “I thought, wow, she was doing with language something like what Jimi Hendrix does with a guitar. By which I meant she walked a line between chaos and order, she riffed, and just when it seemed that a sentence was veering off into randomness, she brought it back and united it with the melody.”

Woolf’s example helped drive Cunningham to become a writer himself. His novel The Hours essentially retells Dalloway as a story within a story, alternating between a variation of Woolf’s original narrative and a fictional speculation on Woolf herself. Cunningham’s 1998 novel won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, then was adapted into a 2002 film of the same name, starring Nicole Kidman as Woolf.

“I feel certain she’d have disliked the book—she was a ferocious critic,” Cunningham said of Woolf, who died in 1941. “She’d probably have had reservations about the film as well, though I like to think that it would have pleased her to see herself played by a beautiful Hollywood movie star.”

Kidman created a buzz for the movie by donning a false nose to mute her matinee-perfect face, evoking Woolf as a woman whom family friend Nigel Nicolson once described as “always beautiful but never pretty.”

Woolf, a seminal figure in feminist thought, would probably not have been surprised that a big-screen treatment of her life would spark so much talk about how she looked rather than what she did . But she was also keenly intent on grounding her literary themes within the world of sensation and physicality, so maybe there’s some value, while considering her ideas, in also remembering what it was like to see and hear her.

We know her best in profile. Many pictures of Woolf show her glancing off to the side, like the figure on a coin. The most notable exception is a 1939 photograph by Gisele Freund in which Woolf peers directly into the camera. Woolf hated the photograph—perhaps because, on some level, she knew how deftly Freund had captured her subject. “I loathe being hoisted about on top of a stick for anyone to stare at,” lamented Woolf, who complained that Freund had broken her promise not to circulate the picture.

The most striking aspect of the photo is the intensity of Woolf’s gaze. In both her conversation and her writing, Woolf had a genius for not only looking at a subject, but looking through it, teasing out inferences and implications at multiple levels. It’s perhaps why the sea figures so prominently in her fiction, as a metaphor for a world in which the bright currents we see at the surface of reality reveal, upon closer inspection, a depth that goes downward for miles.

Take, for example, Woolf’s widely anthologized essay, “The Death of the Moth,” in which she notices a moth’s last moments of life, then records the experience as a window into the fragility of all existence. “The insignificant little creature now knew death,” Woolf reports.

As I looked at the dead moth, this minute wayside triumph of so great a force over so mean an antagonist filled me with wonder. . . . The moth having righted himself now lay most decently and uncomplainingly composed. Oh yes, he seemed to say, death is stronger than I am.

Woolf takes an equally miniaturist tack in “The Mark on the Wall,” a sketch in which the narrator studies a mark on the wall ultimately revealed as a snail. Although the premise sounds militantly boring—the literary equivalent of watching paint dry—the mark on the wall works as a locus of concentration, like a hypnotist’s watch, allowing the narrator to consider everything from Shakespeare to World War I. In its subtle tracking of how the mind free-associates and its ample use of interior monolog, the sketch serves as a keynote of sorts for the modernist literary movement that Woolf worked so tirelessly to advance.

Woolf’s penetrating sensibility took some getting used to, since she expected those around her to look at the world just as unblinkingly. She didn’t seem to have much patience for small talk. Renowned scholar Hermione Lee wrote an exhaustive 1997 biography of Woolf, yet confesses some anxiety about the prospect, were it possible, of greeting Woolf in person. “I think I would have been afraid of meeting her,” Lee wrote. “I am afraid of not being intelligent enough for her.”

Nicolson, the son of Woolf’s close friend and onetime lover, Vita Sackville-West, had fond memories of hunting butterflies with Woolf when he was a boy—an outing that allowed Woolf to indulge a pastime she’d enjoyed in childhood. “Virginia could tolerate children for short periods, but fled from babies,” he recalled. Nicolson also remembered Woolf’s distaste for bland generalities, even when uttered by youngsters. She once asked the young Nicolson for a detailed report on his morning, including the quality of the sun that had awakened him, and whether he had first put on his right or left sock while dressing.

“It was a lesson in observation, but it was also a hint,” he wrote many years later. “‘Unless you catch ideas on the wing and nail them down, you will soon cease to have any.’ It was advice that I was to remember all my life.”

Thanks to a commentary Woolf did for the BBC, we don’t have to guess what she sounded like. In the 1937 recording, widely available online, Woolf reflects on how the English language pollinates and blooms into new forms. “Royal words mate with commoners,” she tells listeners in a subversive reference to the recent abdication of King Edward VIII, who had forfeited his throne to marry American Wallis Simpson. Woolf’s voice is plummy and patrician, like an English version of Eleanor Roosevelt. Not surprising, perhaps, given Woolf’s origin in one of England’s most prominent families.