- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Nature vs. Nurture Debate

Genetic and Environmental Influences and How They Interact

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Joshua Seong

- Definitions

- Interaction

- Contemporary Views

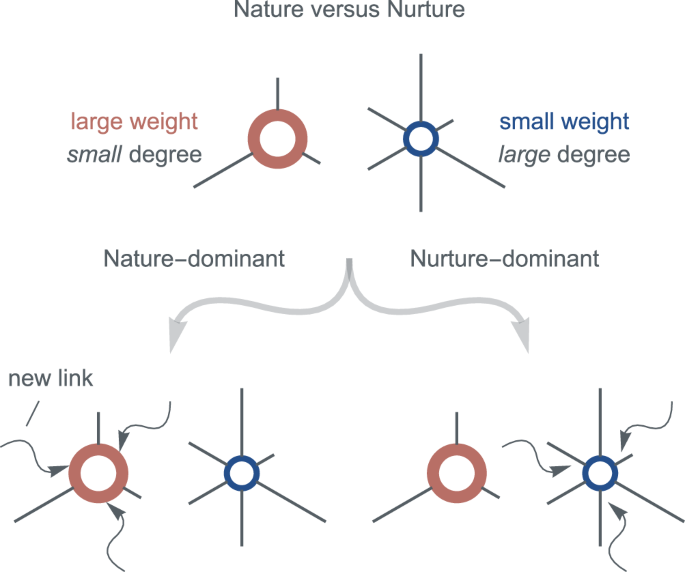

Nature refers to how genetics influence an individual's personality, whereas nurture refers to how their environment (including relationships and experiences) impacts their development. Whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in personality and development is one of the oldest philosophical debates within the field of psychology .

Learn how each is defined, along with why the issue of nature vs. nurture continues to arise. We also share a few examples of when arguments on this topic typically occur, how the two factors interact with each other, and contemporary views that exist in the debate of nature vs. nurture as it stands today.

Nature and Nurture Defined

To better understand the nature vs. nurture argument, it helps to know what each of these terms means.

- Nature refers largely to our genetics . It includes the genes we are born with and other hereditary factors that can impact how our personality is formed and influence the way that we develop from childhood through adulthood.

- Nurture encompasses the environmental factors that impact who we are. This includes our early childhood experiences, the way we were raised , our social relationships, and the surrounding culture.

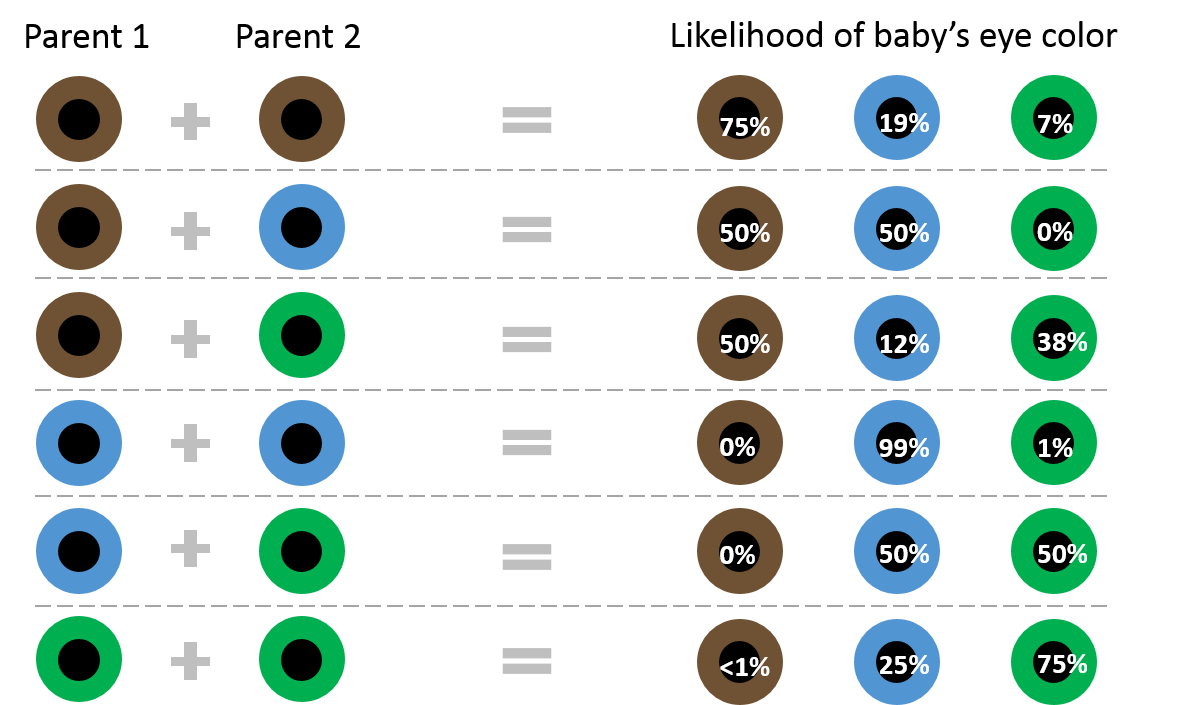

A few biologically determined characteristics include genetic diseases, eye color, hair color, and skin color. Other characteristics are tied to environmental influences, such as how a person behaves, which can be influenced by parenting styles and learned experiences.

For example, one child might learn through observation and reinforcement to say please and thank you. Another child might learn to behave aggressively by observing older children engage in violent behavior on the playground.

The Debate of Nature vs. Nurture

The nature vs. nurture debate centers on the contributions of genetics and environmental factors to human development. Some philosophers, such as Plato and Descartes, suggested that certain factors are inborn or occur naturally regardless of environmental influences.

Advocates of this point of view believe that all of our characteristics and behaviors are the result of evolution. They contend that genetic traits are handed down from parents to their children and influence the individual differences that make each person unique.

Other well-known thinkers, such as John Locke, believed in what is known as tabula rasa which suggests that the mind begins as a blank slate . According to this notion, everything that we are is determined by our experiences.

Behaviorism is a good example of a theory rooted in this belief as behaviorists feel that all actions and behaviors are the results of conditioning. Theorists such as John B. Watson believed that people could be trained to do and become anything, regardless of their genetic background.

People with extreme views are called nativists and empiricists. Nativists take the position that all or most behaviors and characteristics are the result of inheritance. Empiricists take the position that all or most behaviors and characteristics result from learning.

Examples of Nature vs. Nurture

One example of when the argument of nature vs. nurture arises is when a person achieves a high level of academic success . Did they do so because they are genetically predisposed to elevated levels of intelligence, or is their success a result of an enriched environment?

The argument of nature vs. nurture can also be made when it comes to why a person behaves in a certain way. If a man abuses his wife and kids, for instance, is it because he was born with violent tendencies, or is violence something he learned by observing others in his life when growing up?

Nature vs. Nurture in Psychology

Throughout the history of psychology , the debate of nature vs. nurture has continued to stir up controversy. Eugenics, for example, was a movement heavily influenced by the nativist approach.

Psychologist Francis Galton coined the terms 'nature versus nurture' and 'eugenics' and believed that intelligence resulted from genetics. Galton also felt that intelligent individuals should be encouraged to marry and have many children, while less intelligent individuals should be discouraged from reproducing.

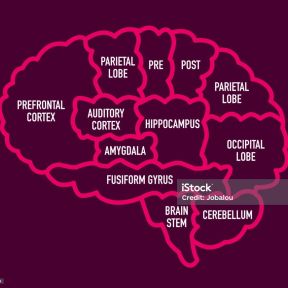

The value placed on nature vs. nurture can even vary between the different branches of psychology , with some branches taking a more one-sided approach. In biopsychology , for example, researchers conduct studies exploring how neurotransmitters influence behavior, emphasizing the role of nature.

In social psychology , on the other hand, researchers might conduct studies looking at how external factors such as peer pressure and social media influence behaviors, stressing the importance of nurture. Behaviorism is another branch that focuses on the impact of the environment on behavior.

Nature vs. Nurture in Child Development

Some psychological theories of child development place more emphasis on nature and others focus more on nurture. An example of a nativist theory involving child development is Chomsky's concept of a language acquisition device (LAD). According to this theory, all children are born with an instinctive mental capacity that allows them to both learn and produce language.

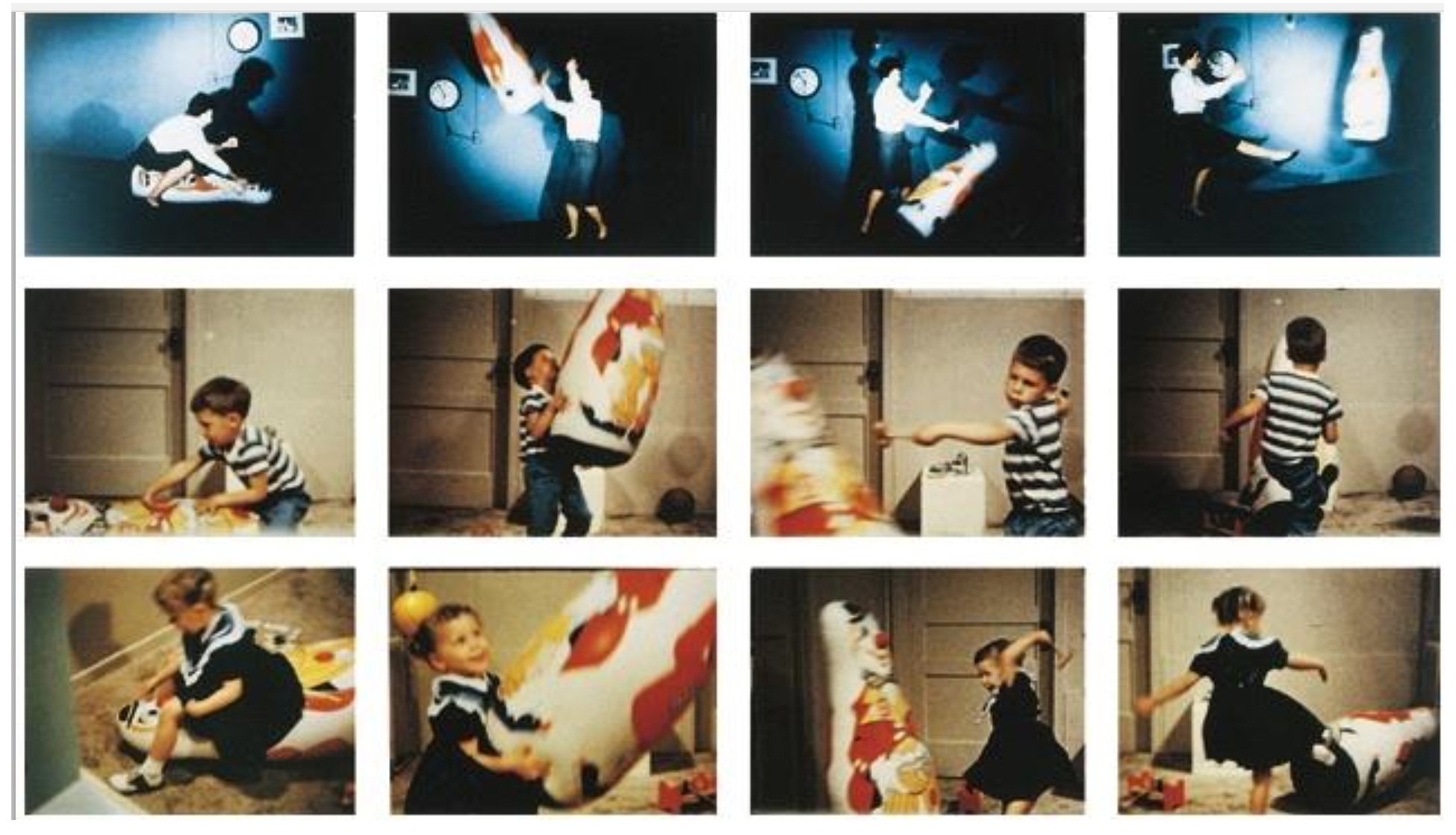

An example of an empiricist child development theory is Albert Bandura's social learning theory . This theory says that people learn by observing the behavior of others. In his famous Bobo doll experiment , Bandura demonstrated that children could learn aggressive behaviors simply by observing another person acting aggressively.

Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Development

There is also some argument as to whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in the development of one's personality. The answer to this question varies depending on which personality development theory you use.

According to behavioral theories, our personality is a result of the interactions we have with our environment, while biological theories suggest that personality is largely inherited. Then there are psychodynamic theories of personality that emphasize the impact of both.

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Illness Development

One could argue that either nature or nurture contributes to mental health development. Some causes of mental illness fall on the nature side of the debate, including changes to or imbalances with chemicals in the brain. Genetics can also contribute to mental illness development, increasing one's risk of a certain disorder or disease.

Mental disorders with some type of genetic component include autism , attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder , major depression , and schizophrenia .

Other explanations for mental illness are environmental. This includes being exposed to environmental toxins, such as drugs or alcohol, while still in utero. Certain life experiences can also influence mental illness development, such as witnessing a traumatic event, leading to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Health Therapy

Different types of mental health treatment can also rely more heavily on either nature or nurture in their treatment approach. One of the goals of many types of therapy is to uncover any life experiences that may have contributed to mental illness development (nurture).

However, genetics (nature) can play a role in treatment as well. For instance, research indicates that a person's genetic makeup can impact how their body responds to antidepressants. Taking this into consideration is important for getting that person the help they need.

Interaction Between Nature and Nurture

Which is stronger: nature or nurture? Many researchers consider the interaction between heredity and environment—nature with nurture as opposed to nature versus nurture—to be the most important influencing factor of all.

For example, perfect pitch is the ability to detect the pitch of a musical tone without any reference. Researchers have found that this ability tends to run in families and might be tied to a single gene. However, they've also discovered that possessing the gene is not enough as musical training during early childhood is needed for this inherited ability to manifest itself.

Height is another example of a trait influenced by an interaction between nature and nurture. A child might inherit the genes for height. However, if they grow up in a deprived environment where proper nourishment isn't received, they might never attain the height they could have had if they'd grown up in a healthier environment.

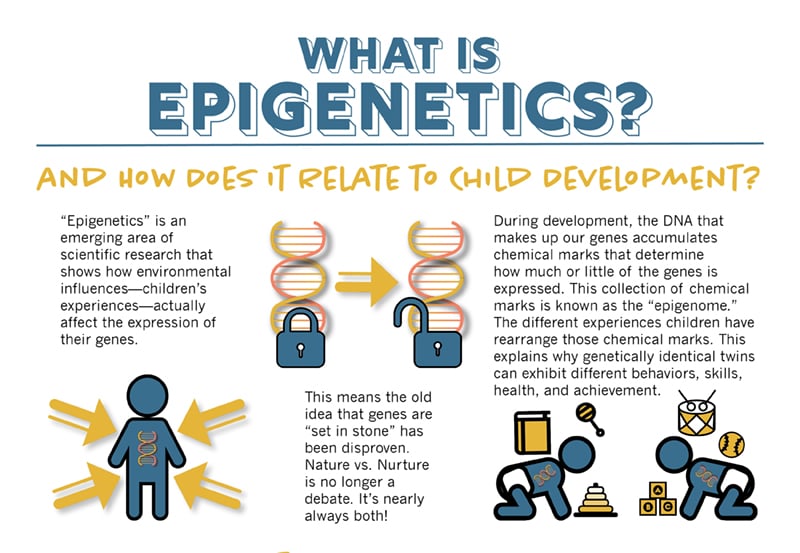

A newer field of study that aims to learn more about the interaction between genes and environment is epigenetics . Epigenetics seeks to explain how environment can impact the way in which genes are expressed.

Some characteristics are biologically determined, such as eye color, hair color, and skin color. Other things, like life expectancy and height, have a strong biological component but are also influenced by environmental factors and lifestyle.

Contemporary Views of Nature vs. Nurture

Most experts recognize that neither nature nor nurture is stronger than the other. Instead, both factors play a critical role in who we are and who we become. Not only that but nature and nurture interact with each other in important ways all throughout our lifespan.

As a result, many in this field are interested in seeing how genes modulate environmental influences and vice versa. At the same time, this debate of nature vs. nurture still rages on in some areas, such as in the origins of homosexuality and influences on intelligence .

While a few people take the extreme nativist or radical empiricist approach, the reality is that there is not a simple way to disentangle the multitude of forces that exist in personality and human development. Instead, these influences include genetic factors, environmental factors, and how each intermingles with the other.

Schoneberger T. Three myths from the language acquisition literature . Anal Verbal Behav . 2010;26(1):107-31. doi:10.1007/bf03393086

National Institutes of Health. Common genetic factors found in 5 mental disorders .

Pain O, Hodgson K, Trubetskoy V, et al. Identifying the common genetic basis of antidepressant response . Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci . 2022;2(2):115-126. doi:10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.07.008

Moulton C. Perfect pitch reconsidered . Clin Med J . 2014;14(5):517-9 doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.14-5-517

Levitt M. Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour . Life Sci Soc Policy . 2013;9:13. doi:10.1186/2195-7819-9-13

Bandura A, Ross D, Ross, SA. Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models . J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1961;63(3):575-582. doi:10.1037/h0045925

Chomsky N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax .

Galton F. Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development .

Watson JB. Behaviorism .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Nature vs. Nurture Debate In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The nature vs. nurture debate in psychology concerns the relative importance of an individual’s innate qualities (nature) versus personal experiences (nurture) in determining or causing individual differences in physical and behavioral traits. While early theories favored one factor over the other, contemporary views recognize a complex interplay between genes and environment in shaping behavior and development.

Key Takeaways

- Nature is what we think of as pre-wiring and is influenced by genetic inheritance and other biological factors.

- Nurture is generally taken as the influence of external factors after conception, e.g., the product of exposure, life experiences, and learning on an individual.

- Behavioral genetics has enabled psychology to quantify the relative contribution of nature and nurture concerning specific psychological traits.

- Instead of defending extreme nativist or nurturist views, most psychological researchers are now interested in investigating how nature and nurture interact in a host of qualitatively different ways.

- For example, epigenetics is an emerging area of research that shows how environmental influences affect the expression of genes.

The nature-nurture debate is concerned with the relative contribution that both influences make to human behavior, such as personality, cognitive traits, temperament and psychopathology.

Examples of Nature vs. Nurture

Nature vs. nurture in child development.

In child development, the nature vs. nurture debate is evident in the study of language acquisition . Researchers like Chomsky (1957) argue that humans are born with an innate capacity for language (nature), known as universal grammar, suggesting that genetics play a significant role in language development.

Conversely, the behaviorist perspective, exemplified by Skinner (1957), emphasizes the role of environmental reinforcement and learning (nurture) in language acquisition.

Twin studies have provided valuable insights into this debate, demonstrating that identical twins raised apart may share linguistic similarities despite different environments, suggesting a strong genetic influence (Bouchard, 1979)

However, environmental factors, such as exposure to language-rich environments, also play a crucial role in language development, highlighting the intricate interplay between nature and nurture in child development.

Nature vs. Nurture in Personality Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in personality psychology centers on the origins of personality traits. Twin studies have shown that identical twins reared apart tend to have more similar personalities than fraternal twins, indicating a genetic component to personality (Bouchard, 1994).

However, environmental factors, such as parenting styles, cultural influences, and life experiences, also shape personality.

For example, research by Caspi et al. (2003) demonstrated that a particular gene (MAOA) can interact with childhood maltreatment to increase the risk of aggressive behavior in adulthood.

This highlights that genetic predispositions and environmental factors contribute to personality development, and their interaction is complex and multifaceted.

Nature vs. Nurture in Mental Illness Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in mental health explores the etiology of depression. Genetic studies have identified specific genes associated with an increased vulnerability to depression, indicating a genetic component (Sullivan et al., 2000).

However, environmental factors, such as adverse life events and chronic stress during childhood, also play a significant role in the development of depressive disorders (Dube et al.., 2002; Keller et al., 2007)

The diathesis-stress model posits that individuals inherit a genetic predisposition (diathesis) to a disorder, which is then activated or exacerbated by environmental stressors (Monroe & Simons, 1991).

This model illustrates how nature and nurture interact to influence mental health outcomes.

Nature vs. Nurture of Intelligence

The nature vs. nurture debate in intelligence examines the relative contributions of genetic and environmental factors to cognitive abilities.

Intelligence is highly heritable, with about 50% of variance in IQ attributed to genetic factors, based on studies of twins, adoptees, and families (Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

Heritability of intelligence increases with age, from about 20% in infancy to as high as 80% in adulthood, suggesting amplifying effects of genes over time.

However, environmental influences, such as access to quality education and stimulating environments, also significantly impact intelligence.

Shared environmental influences like family background are more influential in childhood, whereas non-shared experiences are more important later in life.

Research by Flynn (1987) showed that average IQ scores have increased over generations, suggesting that environmental improvements, known as the Flynn effect , can lead to substantial gains in cognitive abilities.

Molecular genetics provides tools to identify specific genes and understand their pathways and interactions. However, progress has been slow for complex traits like intelligence. Identified genes have small effect sizes (Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

Overall, intelligence results from complex interplay between genes and environment over development. Molecular genetics offers promise to clarify these mechanisms. The nature vs nurture debate is outdated – both play key roles.

Nativism (Extreme Nature Position)

It has long been known that certain physical characteristics are biologically determined by genetic inheritance.

Color of eyes, straight or curly hair, pigmentation of the skin, and certain diseases (such as Huntingdon’s chorea) are all a function of the genes we inherit.

These facts have led many to speculate as to whether psychological characteristics such as behavioral tendencies, personality attributes, and mental abilities are also “wired in” before we are even born.

Those who adopt an extreme hereditary position are known as nativists. Their basic assumption is that the characteristics of the human species as a whole are a product of evolution and that individual differences are due to each person’s unique genetic code.

In general, the earlier a particular ability appears, the more likely it is to be under the influence of genetic factors. Estimates of genetic influence are called heritability.

Examples of extreme nature positions in psychology include Chomsky (1965), who proposed language is gained through the use of an innate language acquisition device. Another example of nature is Freud’s theory of aggression as being an innate drive (called Thanatos).

Characteristics and differences that are not observable at birth, but which emerge later in life, are regarded as the product of maturation. That is to say, we all have an inner “biological clock” which switches on (or off) types of behavior in a pre-programmed way.

The classic example of the way this affects our physical development are the bodily changes that occur in early adolescence at puberty.

However, nativists also argue that maturation governs the emergence of attachment in infancy , language acquisition , and even cognitive development .

Empiricism (Extreme Nurture Position)

At the other end of the spectrum are the environmentalists – also known as empiricists (not to be confused with the other empirical/scientific approach ).

Their basic assumption is that at birth, the human mind is a tabula rasa (a blank slate) and that this is gradually “filled” as a result of experience (e.g., behaviorism ).

From this point of view, psychological characteristics and behavioral differences that emerge through infancy and childhood are the results of learning. It is how you are brought up (nurture) that governs the psychologically significant aspects of child development and the concept of maturation applies only to the biological.

For example, Bandura’s (1977) social learning theory states that aggression is learned from the environment through observation and imitation. This is seen in his famous bobo doll experiment (Bandura, 1961).

Also, Skinner (1957) believed that language is learned from other people via behavior-shaping techniques.

Evidence for Nature

- Biological Approach

- Biology of Gender

- Medical Model

Freud (1905) stated that events in our childhood have a great influence on our adult lives, shaping our personality.

He thought that parenting is of primary importance to a child’s development , and the family as the most important feature of nurture was a common theme throughout twentieth-century psychology (which was dominated by environmentalists’ theories).

Behavioral Genetics

Researchers in the field of behavioral genetics study variation in behavior as it is affected by genes, which are the units of heredity passed down from parents to offspring.

“We now know that DNA differences are the major systematic source of psychological differences between us. Environmental effects are important but what we have learned in recent years is that they are mostly random – unsystematic and unstable – which means that we cannot do much about them.” Plomin (2018, xii)

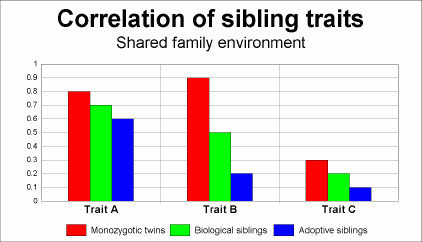

Behavioral genetics has enabled psychology to quantify the relative contribution of nature and nurture with regard to specific psychological traits. One way to do this is to study relatives who share the same genes (nature) but a different environment (nurture). Adoption acts as a natural experiment which allows researchers to do this.

Empirical studies have consistently shown that adoptive children show greater resemblance to their biological parents, rather than their adoptive, or environmental parents (Plomin & DeFries, 1983; 1985).

Another way of studying heredity is by comparing the behavior of twins, who can either be identical (sharing the same genes) or non-identical (sharing 50% of genes). Like adoption studies, twin studies support the first rule of behavior genetics; that psychological traits are extremely heritable, about 50% on average.

The Twins in Early Development Study (TEDS) revealed correlations between twins on a range of behavioral traits, such as personality (empathy and hyperactivity) and components of reading such as phonetics (Haworth, Davis, Plomin, 2013; Oliver & Plomin, 2007; Trouton, Spinath, & Plomin, 2002).

Implications

Jenson (1969) found that the average I.Q. scores of black Americans were significantly lower than whites he went on to argue that genetic factors were mainly responsible – even going so far as to suggest that intelligence is 80% inherited.

The storm of controversy that developed around Jenson’s claims was not mainly due to logical and empirical weaknesses in his argument. It was more to do with the social and political implications that are often drawn from research that claims to demonstrate natural inequalities between social groups.

For many environmentalists, there is a barely disguised right-wing agenda behind the work of the behavioral geneticists. In their view, part of the difference in the I.Q. scores of different ethnic groups are due to inbuilt biases in the methods of testing.

More fundamentally, they believe that differences in intellectual ability are a product of social inequalities in access to material resources and opportunities. To put it simply children brought up in the ghetto tend to score lower on tests because they are denied the same life chances as more privileged members of society.

Now we can see why the nature-nurture debate has become such a hotly contested issue. What begins as an attempt to understand the causes of behavioral differences often develops into a politically motivated dispute about distributive justice and power in society.

What’s more, this doesn’t only apply to the debate over I.Q. It is equally relevant to the psychology of sex and gender , where the question of how much of the (alleged) differences in male and female behavior is due to biology and how much to culture is just as controversial.

Polygenic Inheritance

Rather than the presence or absence of single genes being the determining factor that accounts for psychological traits, behavioral genetics has demonstrated that multiple genes – often thousands, collectively contribute to specific behaviors.

Thus, psychological traits follow a polygenic mode of inheritance (as opposed to being determined by a single gene). Depression is a good example of a polygenic trait, which is thought to be influenced by around 1000 genes (Plomin, 2018).

This means a person with a lower number of these genes (under 500) would have a lower risk of experiencing depression than someone with a higher number.

The Nature of Nurture

Nurture assumes that correlations between environmental factors and psychological outcomes are caused environmentally. For example, how much parents read with their children and how well children learn to read appear to be related. Other examples include environmental stress and its effect on depression.

However, behavioral genetics argues that what look like environmental effects are to a large extent really a reflection of genetic differences (Plomin & Bergeman, 1991).

People select, modify and create environments correlated with their genetic disposition. This means that what sometimes appears to be an environmental influence (nurture) is a genetic influence (nature).

So, children that are genetically predisposed to be competent readers, will be happy to listen to their parents read them stories, and be more likely to encourage this interaction.

Interaction Effects

However, in recent years there has been a growing realization that the question of “how much” behavior is due to heredity and “how much” to the environment may itself be the wrong question.

Take intelligence as an example. Like almost all types of human behavior, it is a complex, many-sided phenomenon which reveals itself (or not!) in a great variety of ways.

The “how much” question assumes that psychological traits can all be expressed numerically and that the issue can be resolved in a quantitative manner.

Heritability statistics revealed by behavioral genetic studies have been criticized as meaningless, mainly because biologists have established that genes cannot influence development independently of environmental factors; genetic and nongenetic factors always cooperate to build traits. The reality is that nature and culture interact in a host of qualitatively different ways (Gottlieb, 2007; Johnston & Edwards, 2002).

Instead of defending extreme nativist or nurturist views, most psychological researchers are now interested in investigating how nature and nurture interact.

For example, in psychopathology , this means that both a genetic predisposition and an appropriate environmental trigger are required for a mental disorder to develop. For example, epigenetics state that environmental influences affect the expression of genes.

What is Epigenetics?

Epigenetics is the term used to describe inheritance by mechanisms other than through the DNA sequence of genes. For example, features of a person’s physical and social environment can effect which genes are switched-on, or “expressed”, rather than the DNA sequence of the genes themselves.

Stressors and memories can be passed through small RNA molecules to multiple generations of offspring in ways that meaningfully affect their behavior.

One such example is what is known as the Dutch Hunger Winter, during last year of the Second World War. What they found was that children who were in the womb during the famine experienced a life-long increase in their chances of developing various health problems compared to children conceived after the famine.

Epigenetic effects can sometimes be passed from one generation to the next, although the effects only seem to last for a few generations. There is some evidence that the effects of the Dutch Hunger Winter affected grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the famine.

Therefore, it makes more sense to say that the difference between two people’s behavior is mostly due to hereditary factors or mostly due to environmental factors.

This realization is especially important given the recent advances in genetics, such as polygenic testing. The Human Genome Project, for example, has stimulated enormous interest in tracing types of behavior to particular strands of DNA located on specific chromosomes.

If these advances are not to be abused, then there will need to be a more general understanding of the fact that biology interacts with both the cultural context and the personal choices that people make about how they want to live their lives.

There is no neat and simple way of unraveling these qualitatively different and reciprocal influences on human behavior.

Epigenetics: Licking Rat Pups

Michael Meaney and his colleagues at McGill University in Montreal, Canada conducted the landmark epigenetic study on mother rats licking and grooming their pups.

This research found that the amount of licking and grooming received by rat pups during their early life could alter their epigenetic marks and influence their stress responses in adulthood.

Pups that received high levels of maternal care (i.e., more licking and grooming) had a reduced stress response compared to those that received low levels of maternal care.

Meaney’s work with rat maternal behavior and its epigenetic effects has provided significant insights into the understanding of early-life experiences, gene expression, and adult behavior.

It underscores the importance of the early-life environment and its long-term impacts on an individual’s mental health and stress resilience.

Epigenetics: The Agouti Mouse Study

Waterland and Jirtle’s 2003 study on the Agouti mouse is another foundational work in the field of epigenetics that demonstrated how nutritional factors during early development can result in epigenetic changes that have long-lasting effects on phenotype.

In this study, they focused on a specific gene in mice called the Agouti viable yellow (A^vy) gene. Mice with this gene can express a range of coat colors, from yellow to mottled to brown.

This variation in coat color is related to the methylation status of the A^vy gene: higher methylation is associated with the brown coat, and lower methylation with the yellow coat.

Importantly, the coat color is also associated with health outcomes, with yellow mice being more prone to obesity, diabetes, and tumorigenesis compared to brown mice.

Waterland and Jirtle set out to investigate whether maternal diet, specifically supplementation with methyl donors like folic acid, choline, betaine, and vitamin B12, during pregnancy could influence the methylation status of the A^vy gene in offspring.

Key findings from the study include:

Dietary Influence : When pregnant mice were fed a diet supplemented with methyl donors, their offspring had an increased likelihood of having the brown coat color. This indicated that the supplemented diet led to an increased methylation of the A^vy gene.

Health Outcomes : Along with the coat color change, these mice also had reduced risks of obesity and other health issues associated with the yellow phenotype.

Transgenerational Effects : The study showed that nutritional interventions could have effects that extend beyond the individual, affecting the phenotype of the offspring.

The implications of this research are profound. It highlights how maternal nutrition during critical developmental periods can have lasting effects on offspring through epigenetic modifications, potentially affecting health outcomes much later in life.

The study also offers insights into how dietary and environmental factors might contribute to disease susceptibility in humans.

Bandura, A. Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 63, 575-582

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bouchard, T. J. (1994). Genes, Environment, and Personality. Science, 264 (5166), 1700-1701.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss . New York: Basic Books.

Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H., … & Poulton, R. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science , 301 (5631), 386-389.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax . MIT Press.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Croft, J. B. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors , 27 (5), 713-725.

Flynn, J. R. (1987). Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure. Psychological Bulletin , 101 (2), 171.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality . Se, 7.

Galton, F. (1883). Inquiries into human faculty and its development . London: J.M. Dent & Co.

Gottlieb, G. (2007). Probabilistic epigenesis. Developmental Science, 10 , 1–11.

Haworth, C. M., Davis, O. S., & Plomin, R. (2013). Twins Early Development Study (TEDS): a genetically sensitive investigation of cognitive and behavioral development from childhood to young adulthood . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1) , 117-125.

Jensen, A. R. (1969). How much can we boost I.Q. and scholastic achievement? Harvard Educational Review, 33 , 1-123.

Johnston, T. D., & Edwards, L. (2002). Genes, interactions, and the development of behavior . Psychological Review , 109, 26–34.

Keller, M. C., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2007). Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry , 164 (10), 1521-1529.

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin , 110 (3), 406.

Oliver, B. R., & Plomin, R. (2007). Twins” Early Development Study (TEDS): A multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems from childhood through adolescence . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 10(1) , 96-105.

Petrill, S. A., Plomin, R., Berg, S., Johansson, B., Pedersen, N. L., Ahern, F., & McClearn, G. E. (1998). The genetic and environmental relationship between general and specific cognitive abilities in twins age 80 and older. Psychological Science , 9 (3), 183-189.

Plomin, R., & Petrill, S. A. (1997). Genetics and intelligence: What’s new?. Intelligence , 24 (1), 53-77.

Plomin, R. (2018). Blueprint: How DNA makes us who we are . MIT Press.

Plomin, R., & Bergeman, C. S. (1991). The nature of nurture: Genetic influence on “environmental” measures. behavioral and Brain Sciences, 14(3) , 373-386.

Plomin, R., & DeFries, J. C. (1983). The Colorado adoption project. Child Development , 276-289.

Plomin, R., & DeFries, J. C. (1985). The origins of individual differences in infancy; the Colorado adoption project. Science, 230 , 1369-1371.

Plomin, R., & Spinath, F. M. (2004). Intelligence: genetics, genes, and genomics. Journal of personality and social psychology , 86 (1), 112.

Plomin, R., & Von Stumm, S. (2018). The new genetics of intelligence. Nature Reviews Genetics , 19 (3), 148-159.

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior . Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry , 157 (10), 1552-1562.

Szyf, M., Weaver, I. C., Champagne, F. A., Diorio, J., & Meaney, M. J. (2005). Maternal programming of steroid receptor expression and phenotype through DNA methylation in the rat . Frontiers in neuroendocrinology , 26 (3-4), 139-162.

Trouton, A., Spinath, F. M., & Plomin, R. (2002). Twins early development study (TEDS): a multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems in childhood . Twin Research and Human Genetics, 5(5) , 444-448.

Waterland, R. A., & Jirtle, R. L. (2003). Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation . Molecular and cellular biology, 23 (15), 5293-5300.

Further Information

- Genetic & Environmental Influences on Human Psychological Differences

Evidence for Nurture

- Classical Conditioning

- Little Albert Experiment

- Operant Conditioning

- Behaviorism

- Social Learning Theory

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

- Social Roles

- Attachment Styles

- The Hidden Links Between Mental Disorders

- Visual Cliff Experiment

- Behavioral Genetics, Genetics, and Epigenetics

- Epigenetics

- Is Epigenetics Inherited?

- Physiological Psychology

- Bowlby’s Maternal Deprivation Hypothesis

- So is it nature not nurture after all?

Evidence for an Interaction

- Genes, Interactions, and the Development of Behavior

- Agouti Mouse Study

- Biological Psychology

What does nature refer to in the nature vs. nurture debate?

In the nature vs. nurture debate, “nature” refers to the influence of genetics, innate qualities, and biological factors on human development, behavior, and traits. It emphasizes the role of hereditary factors in shaping who we are.

What does nurture refer to in the nature vs. nurture debate?

In the nature vs. nurture debate, “nurture” refers to the influence of the environment, upbringing, experiences, and social factors on human development, behavior, and traits. It emphasizes the role of external factors in shaping who we are.

Why is it important to determine the contribution of heredity (nature) and environment (nurture) in human development?

Determining the contribution of heredity and environment in human development is crucial for understanding the complex interplay between genetic factors and environmental influences. It helps identify the relative significance of each factor, informing interventions, policies, and strategies to optimize human potential and address developmental challenges.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Are Nature vs. Nurture Examples?

How is nature defined, how is nurture defined, the nature vs. nurture debate, nature vs. nurture examples, what is empiricism (extreme nurture position), contemporary views of nature vs. nurture.

Nature vs. nurture is an age-old debate about whether genetics (nature) plays a bigger role in determining a person's characteristics than lived experience and environmental factors (nurture). The term "nature vs. nature" was coined by English naturalist Charles Darwin's younger half-cousin, anthropologist Francis Galton, around 1875.

In psychology, the extreme nature position (nativism) proposes that intelligence and personality traits are inherited and determined only by genetics.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the extreme nurture position (empiricism) asserts that the mind is a blank slate at birth; external factors like education and upbringing determine who someone becomes in adulthood and how their mind works. Both of these extreme positions have shortcomings and are antiquated.

This article explores the difference between nature and nurture. It gives nature vs. nurture examples and explains why outdated views of nativism and empiricism don't jibe with contemporary views.

Thanasis Zovoilis / Getty Images

In the context of nature vs. nurture, "nature" refers to genetics and heritable factors that are passed down to children from their biological parents.

Genes and hereditary factors determine many aspects of someone’s physical appearance and other individual characteristics, such as a genetically inherited predisposition for certain personality traits.

Scientists estimate that 20% to 60% percent of temperament is determined by genetics and that many (possibly thousands) of common gene variations combine to influence individual characteristics of temperament.

However, the impact of gene-environment (or nature-nurture) interactions on someone's traits is interwoven. Environmental factors also play a role in temperament by influencing gene activity. For example, in children raised in an adverse environment (such as child abuse or violence), genes that increase the risk of impulsive temperamental characteristics may be activated (turned on).

Trying to measure "nature vs. nurture" scientifically is challenging. It's impossible to know precisely where the influence of genes and environment begin or end.

How Are Inherited Traits Measured?

“Heritability” describes the influence that genes have on human characteristics and traits. It's measured on a scale of 0.0 to 1.0. Very strong heritable traits like someone's eye color are ranked a 1.0.

Traits that have nothing to do with genetics, like speaking with a regional accent ranks a zero. Most human characteristics score between a 0.30 and 0.60 on the heritability scale, which reflects a blend of genetics (nature) and environmental (nurture) factors.

Thousands of years ago, ancient Greek philosophers like Plato believed that "innate knowledge" is present in our minds at birth. Every parent knows that babies are born with innate characteristics. Anecdotally, it may seem like a kid's "Big 5" personality traits (agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness) were predetermined before birth.

What is the "Big 5" personality traits

The Big 5 personality traits is a theory that describes the five basic dimensions of personality. It was developed in 1949 by D. W. Fiske and later expanded upon by other researchers and is used as a framework to study people's behavior.

From a "nature" perspective, the fact that every child has innate traits at birth supports Plato's philosophical ideas about innatism. However, personality isn't set in stone. Environmental "nurture" factors can change someone's predominant personality traits over time. For example, exposure to the chemical lead during childhood may alter personality.

In 2014, a meta-analysis of genetic and environmental influences on personality development across the human lifespan found that people change with age. Personality traits are relatively stable during early childhood but often change dramatically during adolescence and young adulthood.

It's impossible to know exactly how much "nurture" changes personality as people get older. In 2019, a study of how stable personality traits are from age 16 to 66 found that people's Big 5 traits are both stable and malleable (able to be molded). During the 50-year span from high school to retirement, some traits like agreeableness and conscientiousness tend to increase, while others appear to be set in stone.

Nurture refers to all of the external or environmental factors that affect human development such as how someone is raised, socioeconomic status, early childhood experiences, education, and daily habits.

Although the word "nurture" may conjure up images of babies and young children being cared for by loving parents, environmental factors and life experiences have an impact on our psychological and physical well-being across the human life span. In adulthood, "nurturing" oneself by making healthy lifestyle choices can offset certain genetic predispositions.

For example, a May 2022 study found that people with a high genetic risk of developing the brain disorder Alzheimer's disease can lower their odds of developing dementia (a group of symptoms that affect memory, thinking, and social abilities enough to affect daily life) by adopting these seven healthy habits in midlife:

- Staying active

- Healthy eating

- Losing weight

- Not smoking

- Reducing blood sugar

- Controlling cholesterol

- Maintaining healthy blood pressure

The nature vs. nurture debate centers around whether individual differences in behavioral traits and personality are caused primarily by nature or nurture. Early philosophers believed the genetic traits passed from parents to their children influence individual differences and traits. Other well-known philosophers believed the mind begins as a blank slate and that everything we are is determined by our experiences.

While early theories favored one factor over the other, experts today recognize there is a complex interaction between genetics and the environment and that both nature and nurture play a critical role in shaping who we are.

Eye color and skin pigmentation are examples of "nature" because they are present at birth and determined by inherited genes. Developmental delays due to toxins (such as exposure to lead as a child or exposure to drugs in utero) are examples of "nurture" because the environment can negatively impact learning and intelligence.

In Child Development

The nature vs. nurture debate in child development is apparent when studying language development. Nature theorists believe genetics plays a significant role in language development and that children are born with an instinctive ability that allows them to both learn and produce language.

Nurture theorists would argue that language develops by listening and imitating adults and other children.

In addition, nurture theorists believe people learn by observing the behavior of others. For example, contemporary psychologist Albert Bandura's social learning theory suggests that aggression is learned through observation and imitation.

In Psychology

In psychology, the nature vs. nurture beliefs vary depending on the branch of psychology.

- Biopsychology: Researchers analyze how the brain, neurotransmitters, and other aspects of our biology influence our behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. emphasizing the role of nature.

- Social psychology: Researchers study how external factors such as peer pressure and social media influence behaviors, emphasizing the importance of nurture.

- Behaviorism: This theory of learning is based on the idea that our actions are shaped by our interactions with our environment.

In Personality Development

Whether nature or nurture plays a bigger role in personality development depends on different personality development theories.

- Behavioral theories: Our personality is a result of the interactions we have with our environment, such as parenting styles, cultural influences, and life experiences.

- Biological theories: Personality is mostly inherited which is demonstrated by a study in the 1990s that concluded identical twins reared apart tend to have more similar personalities than fraternal twins.

- Psychodynamic theories: Personality development involves both genetic predispositions and environmental factors and their interaction is complex.

In Mental Illness

Both nature and nurture can contribute to mental illness development.

For example, at least five mental health disorders are associated with some type of genetic component ( autism , attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) , bipolar disorder , major depression, and schizophrenia ).

Other explanations for mental illness are environmental, such as:

- Being exposed to drugs or alcohol in utero

- Witnessing a traumatic event, leading to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Adverse life events and chronic stress during childhood

In Mental Health Therapy

Mental health treatment can involve both nature and nurture. For example, a therapist may explore life experiences that may have contributed to mental illness development (nurture) as well as family history of mental illness (nature).

At the same time, research indicates that a person's genetic makeup may impact how their body responds to antidepressants. Taking this into consideration is important for finding the right treatment for each individual.

What Is Nativism (Extreme Nature Position)?

Innatism emphasizes nature's role in shaping our minds and personality traits before birth. Nativism takes this one step further and proposes that all of people's mental and physical characteristics are inherited and predetermined at birth.

In its extreme form, concepts of nativism gave way to the early 20th century's racially-biased eugenics movement. Thankfully, "selective breeding," which is the idea that only certain people should reproduce in order to create chosen characteristics in offspring, and eugenics, arranged breeding, lost momentum during World War II. At that time, the Nazis' ethnic cleansing (killing people based on their ethnic or religious associations) atrocities were exposed.

Philosopher John Locke's tabula rasa theory from 1689 directly opposes the idea that we are born with innate knowledge. "Tabula rasa" means "blank slate" and implies that our minds do not have innate knowledge at birth.

Locke was an empiricist who believed that all the knowledge we gain in life comes from sensory experiences (using their senses to understand the world), education, and day-to-day encounters after being born.

Today, looking at nature vs. nature in black-and-white terms is considered a misguided dichotomy (two-part system). There are so many shades of gray where nature and nurture overlap. It's impossible to tease out how inherited traits and learned behaviors shape someone's unique characteristics or influence how their mind works.

The influences of nature and nurture in psychology are impossible to unravel. For example, imagine someone growing up in a household with an alcoholic parent who has frequent rage attacks. If that child goes on to develop a substance use disorder and has trouble with emotion regulation in adulthood, it's impossible to know precisely how much genetics (nature) or adverse childhood experiences (nurture) affected that individual's personality traits or issues with alcoholism.

Epigenetics Blurs the Line Between Nature and Nurture

"Epigenetics " means "on top of" genetics. It refers to external factors and experiences that turn genes "on" or "off." Epigenetic mechanisms alter DNA's physical structure in utero (in the womb) and across the human lifespan.

Epigenetics blurs the line between nature and nurture because it says that even after birth, our genetic material isn't set in stone; environmental factors can modify genes during one's lifetime. For example, cannabis exposure during critical windows of development can increase someone's risk of neuropsychiatric disease via epigenetic mechanisms.

Nature vs. nurture is a framework used to examine how genetics (nature) and environmental factors (nurture) influence human development and personality traits.

However, nature vs. nurture isn't a black-and-white issue; there are many shades of gray where the influence of nature and nurture overlap. It's impossible to disentangle how nature and nurture overlap; they are inextricably intertwined. In most cases, nature and nurture combine to make us who we are.

Waller JC. Commentary: the birth of the twin study--a commentary on francis galton’s “the history of twins.” International Journal of Epidemiology . 2012;41(4):913-917. doi:10.1093/ije/dys100

The New York Times. " Major Personality Study Finds That Traits Are Mostly Inherited ."

Medline Plus. Is temperament determined by genetics?

Feldman MW, Ramachandran S. Missing compared to what? Revisiting heritability, genes and culture . Phil Trans R Soc B . 2018;373(1743):20170064. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0064

Winch C. Innatism, concept formation, concept mastery and formal education: innatism, concept formation and formal education . Journal of Philosophy of Education . 2015;49(4):539-556. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12121

Briley DA, Tucker-Drob EM. Genetic and environmental continuity in personality development: A meta-analysis . Psychological Bulletin . 2014;140(5):1303-1331. doi:10.1037/a0037091

Damian RI, Spengler M, Sutu A, Roberts BW. Sixteen going on sixty-six: A longitudinal study of personality stability and change across 50 years . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 2019;117(3):674-695. doi:10.1037/pspp0000210

Tin A, Bressler J, Simino J, et al. Genetic risk, midlife life’s simple 7, and incident dementia in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study . Neurology . Published online May 25, 2022. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200520

Levitt M. Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour . Life Sci Soc Policy . 2013;9(1):13. doi:10.1186/2195-7819-9-13

Ross EJ, Graham DL, Money KM, Stanwood GD. Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: what we know and what we still must learn . Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 Jan;40(1):61-87. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.14

World Health Organization. Lead poisoning .

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models . The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1961; 63 (3), 575–582 doi:10.1037/h0045925

Krapfl JE. Behaviorism and society . Behav Anal. 2016;39(1):123-9. doi:10.1007/s40614-016-0063-8

Bouchard TJ Jr, Lykken DT, McGue M, Segal NL, Tellegen A. Sources of human psychological differences: the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart . Science. 1990 Oct 12;250(4978):223-8. doi: 10.1126/science.2218526

National Institutes of Health. Common genetic factors found in 5 mental disorders .

Franke HA. Toxic Stress: Effects, Prevention and Treatment . Children (Basel). 2014 Nov 3;1(3):390-402. doi: 10.3390/children1030390

Pain O, Hodgson K, Trubetskoy V, et al. Identifying the common genetic basis of antidepressant response . Biol Psychiatry Global Open Sci . 2022;2(2):115-126. doi:10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.07.008

National Human Genome Research Institute. Eugenics and Scientific Racism .

OLL. The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes .

Toraño EG, García MG, Fernández-Morera JL, Niño-García P, Fernández AF. The impact of external factors on the epigenome: in utero and over lifetime . BioMed Research International . 2016;2016:1-17. doi:10.1155/2016/2568635

Smith A, Kaufman F, Sandy MS, Cardenas A. Cannabis exposure during critical windows of development: epigenetic and molecular pathways implicated in neuropsychiatric disease . Curr Envir Health Rpt . 2020;7(3):325-342. doi:10.1007/s40572-020-00275-4

By Christopher Bergland Christopher Bergland is a retired ultra-endurance athlete turned medical writer and science reporter.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: Nature vs. Nurture

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 73207

Developmental psychology seeks to understand the influence of genetics (nature) and environment (nurture) on human development.

Learning objective.

- Evaluate the reciprocal impacts between genes and the environment and the nature vs. nurture debate

- A significant issue in developmental psychology has been the relationship between the innateness of an attribute (whether it is part of our nature) and the environmental effects on that attribute (whether it is derived from or influenced by our environment, or nurture).

- Today, developmental psychologists rarely take polarized positions with regard to most aspects of development; instead, they investigate the relationship between innate and environmental influences.

- The biopsychosocial model states that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a significant role in human development.

- Environmental inputs can affect the expression of genes , a relationship called gene-environment interaction. An individual’s genes and their environment work together, communicating back and forth to create traits .

- The diathesis– stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (diatheses) interact with environmental influences (stressors) to produce disorders, such as depression, anxiety , or schizophrenia .

- genotype That part (DNA sequence) of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of an organism or individual, which determines a specific characteristic (phenotype) of that cell/organism/individual.

- heritability The ratio of the genetic variance of a population to its phenotypic variance; i.e., the proportion of variability that is genetic in origin.

- gene A unit of heredity; a segment of DNA or RNA that is transmitted from one generation to the next and carries genetic information such as the sequence of amino acids for a protein.

- trait An identifying characteristic, habit, or trend.

- innate Inborn; native; natural.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of changes that occur in human beings over the course of their lives. This field examines change and development across a broad range of topics, such as motor skills and other psycho-physiological processes; cognitive development involving areas like problem solving, moral and conceptual understanding; language acquisition; social, personality , and emotional development; and self- concept and identity formation. Developmental psychology explores the extent to which development is a result of gradual accumulation of knowledge or stage-like development, as well as the extent to which children are born with innate mental structures as opposed to learning through experience.

Nature Versus Nurture

A significant issue in developmental psychology is the relationship between the innateness of an attribute (whether it is part of our nature ) and the environmental effects on that attribute (whether it is influenced by our environment, or nurture ). This is often referred to as the nature vs. nurture debate, or nativism vs. empiricism.

- A nativist (“nature”) account of development would argue that the processes in question are innate and influenced by an organism’s genes. Natural human behavior is seen as the result of already-present biological factors, such as genetic code.

- An empiricist (“nurture”) perspective would argue that these processes are acquired through interaction with the environment. Nurtured human behavior is seen as the result of environmental interaction, which can provoke changes in brain structure and chemistry. For example, situations of extreme stress can cause problems like depression.

The nature vs. nurture debate seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are produced by our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture . For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents? Is it because of genetic similarity, or the result of the early childhood environment and what children learn from their parents?

Interaction of Genes and the Environment

Today, developmental psychologists rarely take such polarized positions (either/or) with regard to most aspects of development; instead, they investigate the relationship between innate and environmental influences (both/and). Developmental psychologists will often use the biopsychosocial model to frame their research: this model states that biological, psychological, and social (socio-economical, socio-environmental, and cultural) factors all play a significant role in human development.

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype , however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment: our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). There is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

Heritability refers to the origin of differences among people; it is a concept in biology that describes how much of the variation of a trait in a population is due to genetic differences in that population. Individual development, even of highly heritable traits such as eye color, depends not only on heritability but on a range of environmental factors, such as the other genes present in the organism and the temperature and oxygen levels during development. Environmental inputs can affect the expression of genes, a relationship called gene-environment interaction. Genes and the environment work together, communicating back and forth to create traits.

Some concrete behavioral traits are dependent upon one’s environment, home, or culture, such as the language one speaks, the religion one practices, and the political party one supports. However, some traits which reflect underlying talents and temperaments—such as how proficient at a language, how religious, or how liberal or conservative—can be partially heritable.

This chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the influence of genes and environment on individual traits. Each of these traits is measured and compared between monozygotic (identical) twins, biological siblings who are not twins, and adopted siblings who are not genetically related. Trait A shows a high sibling correlation but little heritability (illustrating the importance of environment). Trait B shows a high heritability, since the correlation of the trait rises sharply with the degree of genetic similarity. Trait C shows low heritability as well as low correlation generally, suggesting that the degree to which individuals display trait C has little to do with either genes or predictable environmental factors.

Heritability Estimates

This chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the influence of genes and environment on individual traits. Typically, monozygotic twins will have a high correlation of sibling traits, while biological siblings will have less in common, and adoptive siblings will have less than that. However, this can vary widely by trait.

Diathesis-Stress Model

The diathesis–stress model is a psychological theory that attempts to explain behavior as a predispositional vulnerability together with stress from life experiences. The term diathesis derives from the Greek term for disposition, or vulnerability, and it can take the form of genetic, psychological, biological, or situational factors. The diathesis, or predisposition , interacts with the subsequent stress response of an individual. Stress refers to a life event or series of events that disrupt a person’s psychological equilibrium and potentially serve as a catalyst to the development of a disorder. Thus, the diathesis–stress model serves to explore how biological or genetic traits (diatheses) interact with environmental influences (stressors) to produce disorders, such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.

- Nature vs. Nurture. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/human-development-14/introduction-to-human-development-69/nature-vs-nurture-265-12800/ . Project : Boundless Psychology. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Introduction to Nature and Nurture

What you’ll learn to do: explain how nature, nurture, and epigenetics influence personality and behavior.

H ow do we become who we are? Traditionally, people’s answers have placed them in one of two camps: nature or nurture. The one says genes determine an individual while the other claims the environment is the linchpin for development. Since the 16th century, when the terms “nature” and “nurture” first came into use, many people have spent ample time debating which is more important, but these discussions have more often led to ideological cul-de-sacs rather than pinnacles of insight.

New research into epigenetics—the science of how the environment influences genetic expression—is changing the conversation. As psychologist David S. Moore explains in his newest book, The Developing Genome , this burgeoning field reveals that what counts is not what genes you have so much as what your genes are doing . And what your genes are doing is influenced by the ever-changing environment they’re in. Factors like stress, nutrition, and exposure to toxins all play a role in how genes are expressed—essentially which genes are turned on or off. Unlike the static conception of nature or nurture, epigenetic research demonstrates how genes and environments continuously interact to produce characteristics throughout a lifetime.

Learning Objectives

- Investigate the historic nature vs. nurture debate and describe techniques psychologists use to learn about the origin of traits

- Explain the basic principles of the theory of evolution by natural selection, genetic variation, and mutation

- Describe epigenetics and examine how gene-environment interactions are critical for expression of physical and psychological characteristics

attributions

Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

DNA image . Provided by: Wikimedia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

The End of Nature Versus Nurture . Authored by: Evan Nesterak. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Introduction to Psychology Copyright © by Utah Tech University Psychology Department is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Nature vs. Nurture

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

The expression “nature vs. nurture” describes the question of how much a person's characteristics are formed by either “nature” or “nurture.” “Nature” means innate biological factors (namely genetics ), while “nurture” can refer to upbringing or life experience more generally.

Traditionally, “nature vs. nurture” has been framed as a debate between those who argue for the dominance of one source of influence or the other, but contemporary experts acknowledge that both “nature” and “nurture” play a role in psychological development and interact in complex ways.

- The Meaning of Nature vs. Nurture

- The Nature-vs.-Nurture Debate

- Identifying Genetic and Environmental Factors

The wording of the phrase “nature vs. nurture” makes it seem as though human individuality— personality traits, intelligence , preferences, and other characteristics—must be based on either the genes people are born with or the environment in which they grew up. The reality, as scientists have shown, is more complicated, and both these and other factors can help account for the many ways in which individuals differ from each other.

The words “nature” and “nurture” themselves can be misleading. Today, “ genetics ” and “environment” are frequently used in their place—with one’s environment including a broader range of experiences than just the nurturing received from parents or caregivers. Further, nature and nurture (or genetics and environment) do not simply compete to influence a person, but often interact with each other; “nature and nurture” work together. Finally, individual differences do not entirely come down to a person’s genetic code or developmental environment—to some extent, they emerge due to messiness in the process of development as well.

A person’s biological nature can affect a person’s experience of the environment. For example, a person with a genetic disposition toward a particular trait, such as aggressiveness, may be more likely to have particular life experiences (including, perhaps, receiving negative reactions from parents or others). Or, a person who grows up with an inclination toward warmth and sociability may seek out and elicit more positive social responses from peers. These life experiences could, in turn, reinforce an individual’s initial tendencies. Nurture or life experience more generally may also modify the effects of nature—for example, by expanding or limiting the extent to which a naturally bright child receives encouragement, access to quality education , and opportunities for achievement.

Epigenetics—the science of modifications in how genes are expressed— illustrates the complex interplay between “nature” and “nurture.” An individual’s environment, including factors such as early-life adversity, may result in changes in the way that parts of a person’s genetic code are “read.” While these epigenetic changes do not override the important influence of genes in general, they do constitute additional ways in which that influence is filtered through “nurture” or the environment.

Theorists and researchers have long battled over whether individual traits and abilities are inborn or are instead forged by experiences after birth. The debate has had broad implications: The real or perceived sources of a person’s strengths and vulnerabilities matter for fields such as education, philosophy , psychiatry , and clinical psychology. Today’s consensus—that individual differences result from a combination of inherited and non-genetic factors—strikes a more nuanced middle path between nature- or nurture-focused extremes.

The debate about nature and nurture has roots that stretch back at least thousands of years, to Ancient Greek theorizing about the causes of personality. During the modern era, theories emphasizing the role of either learning and experience or biological nature have risen and fallen in prominence—with genetics gaining increasing acknowledgment as an important (though not exclusive) influence on individual differences in the later 20th century and beyond.

“Nature versus nurture” was used by English scientist Francis Galton. In 1874, he published the book English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture , arguing that inherited factors were responsible for intelligence and other characteristics.

Genetic determinism emphasizes the importance of an individual’s nature in development. It is the view that genetics is largely or totally responsible for an individual’s psychological characteristics and behavior. The term “biological determinism” is often used synonymously.

The blank slate (or “tabula rasa”) view of the mind emphasizes the importance of nurture and the environment. Notably described by English philosopher John Locke in the 1600s, it proposed that individuals are born with a mind like an unmarked chalkboard and that its contents are based on experience and learning. In the 20th century, major branches of psychology proposed a primary role for nurture and experience , rather than nature, in development, including Freudian psychoanalysis and behaviorism.

Modern scientific methods have allowed researchers to advance further in understanding the complex relationships between genetics, life experience, and psychological characteristics, including mental health conditions and personality traits. Overall, the findings of contemporary studies underscore that with some exceptions—such as rare diseases caused by mutations in a single gene—no one factor, genetic or environmental, solely determines how a characteristic develops.

Scientists use multiple approaches to estimate how important genetics are for any given trait, but one of the most influential is the twin study. While identical (or monozygotic) twins share the same genetic code, fraternal (or dizygotic) twins share about 50 percent of the same genes, like typical siblings. Scientists are able to estimate the degree to which the variation in a particular trait, like extraversion , is explained by genetics in part by analyzing how similar identical twins are on that trait, compared to fraternal twins. ( These studies do have limitations, and estimates based on one population may not closely reflect all other populations.)

It’s hard to call either “nature” or “nurture,” genes or the environment, more important to human psychology. The impact of one set of factors or the other depends on the characteristic, with some being more strongly related to one’s genes —for instance, autism appears to be more heritable than depression . But in general, psychological traits are shaped by a balance of interacting genetic and non-genetic influences.

Both genes and environmental factors can contribute to a person developing mental illness. Research finds that a major part of the variation in the risk for psychiatric conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia can be attributed to genetic differences. But not all of that risk is genetic, and life experiences, such as early-life abuse or neglect, may also affect risk of mental illness (and some individuals, based on their genetics, are likely more susceptible to environmental effects than others).

Like other psychological characteristics, personality is partly heritable. Research suggests less than half of the difference between people on measures of personality traits can be attributed to genes (one recent overall estimate is 40 percent). Non-genetic factors appear to be responsible for an equal or greater portion of personality differences between individuals. Some theorize that the social roles people adopt and invest in as they mature are among the more important non-genetic factors in personality development.

How do we make sense of new experiences? Ultimately, it's about how we categorize them—which we often do by "lumping" or "splitting" them.

How are twin studies used to answer questions related to the nature-and-nurture debate?

All I ask of strangers in the store—don't judge me as being less competent because my hair is grey and my skin well-textured. I’m just out doing my best, as we all are.

The new Biophilia Reactivity Hypothesis argues our attraction to the natural world is not an instinct but a measurable temperament trait.

A Personal Perspective: How can Adam Grant's newest book help OCD sufferers? In more ways than you think.

Do selfish genes mean that humans are designed to be selfish?

Are classical musicians more "craft" and jazz musicians more "creative"? A question for debate.

Where all beliefs and behavior come from.

Many people will outlive their money because of not saving for the future. Sadly, many people are also going to run out of health before they run out of life. Here's how not to.

Our cultures shape us in profound ways. The latest research from cultural psychology offers fascinating insights into the nature-nurture interaction.

- Find Counselling

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United Kingdom

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Presentation on theme: "Nature and Nurture."— Presentation transcript:

Myers’ PSYCHOLOGY (7th Ed)

Introducing Psychology

Beginnings PART 2 Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display.

Nature vs. Nurture How Genes and Environment Influence Behavior.

CHAPTER 2 NATURE WITH NURTURE.

NATURE vs. NURTURE.

Chapter 3 Nature and Nurture of Behavior. Every nongenetic influence, from prenatal nutrition to the people and things around us. environment.

General Psychology. Scripture Matthew 5: 9 Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.. Those who strive to prevent contention,

Nature and Nurture in Psychology Module 03. Behavior Genetics The study of the relative effects of genes and environmental influences our behavior.

UNIT 3C. Behavior Genetics: Predicting Individual Differences Evolutionary Psychology: Understanding Human Nature Reflections on Nature and Nurture.