REVIEW article

A literature review of the potential diagnostic biomarkers of head and neck neoplasms.

- 1 Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 2 Laboratorium of Experimental Medicine and Pediatrics and Member of the Infla-Med Centre of Excellence, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 3 Department of Pneumology, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium

- 4 Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 5 Department of Oncology, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium

- 6 Center for Oncological Research (CORE), University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 7 Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium

- 8 Department of Translational Neurosciences, Antwerp University, Antwerp, Belgium

Head and neck neoplasms have a poor prognosis because of their late diagnosis. Finding a biomarker to detect these tumors in an early phase could improve the prognosis and survival rate. This literature review provides an overview of biomarkers, covering the different -omics fields to diagnose head and neck neoplasms in the early phase. To date, not a single biomarker, nor a panel of biomarkers for the detection of head and neck tumors has been detected with clinical applicability. Limitations for the clinical implementation of the investigated biomarkers are mainly the heterogeneity of the study groups (e.g., small population in which the biomarker was tested, and/or only including high-risk populations) and a low sensitivity and/or specificity of the biomarkers under study. Further research on biomarkers to diagnose head and neck neoplasms in an early stage, is therefore needed.

Introduction

Head and neck cancers account for 5% of all malignant tumors and are responsible for about 600,000 new cases and 300,000 deaths in the world annually. About 50% of the patients fail to achieve cure and cancer relapse occurs despite intensive combined treatment ( 1 , 2 ). To date, there is no adequate biomarker available for the diagnosis of head and neck cancer. However, it is expected that an earlier detection could improve the patient's outcome stage ( 3 – 7 ). In this review, we provide a general overview of biomarkers that were investigated to diagnose head and neck neoplasms in an early phase. Besides, we go into detail on the restrictions of these candidate biomarkers in the clinical practice.

Head and neck neoplasms are defined as benign, premalignant and malignant tumors above the clavicles, with exception of tumors of the brain, and spinal cord and esophagus ( 2 ). This includes tumors of the paranasal sinus, the nasal cavity, the salivary glands, the thyroid, and the upper aerodigestive tract (oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx) ( 8 , 9 ). Carcinomas of the head and neck preferably metastasize lymphogenic to the regional lymph nodes and it is only in an advanced stage that they metastasize hematogenic to the lungs, liver, and bones ( 1 ). The histopathology of the cancers differs from site to site, but the most common ones are squamous cell carcinomas, accounting for more than 85% of the head and neck neoplasms ( 8 , 9 ).

There are several known risk factors for the development of head and neck carcinomas. Prolonged exposure to the sun has been shown to be partly responsible for the genesis of skin and lip cancer ( 2 ). Epstein-Barr virus infection, living in a smoky environment and eating raw salted fish are important risk factors in the development of a nasopharyngeal carcinoma ( 1 , 8 ). Infection with human papilloma virus plays a significant role in the genesis of oropharyngeal cancer ( 8 ). Carcinomas of the paranasal sinuses are more frequently seen in woodworkers; particularly tropical hardwood forms an important trigger ( 1 ). Chewing betel nut, especially in Asia, plays a major role in the etiology of cancer of the oral cavity ( 1 ). Excessive use of tobacco and alcohol induces mucosal changes of the aerodigestive tract. These alterations play an important role in the genesis of malignant tumors ( 1 , 8 ). Besides tobacco and alcohol, other factors influence mucosal changes like nutritional deficiencies (in particular vitamin A and vitamin C in the context of insufficient intake of fresh fruits and vegetables) and genetic predisposition ( 1 , 8 ). In the development of tumors of the skin, mucosa, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands and the salivary glands, former exposure to ionizing radiation might also be of influence ( 2 ).

In comparison with other malignant tumors, head, and neck neoplasms are not common in the Western world. However, a rapid increase of the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers related to HPV in developed countries, has been shown ( 8 ). Although this incidence (and therefore the mortality rate) is lower compared to other cancers, patients with head and neck cancer have a poor prognosis, mainly due to the fact that these types of cancers are usually diagnosed at an advanced stage ( 3 – 7 ). One-third of the patients gets medical care in an early stage, while two-third are only diagnosed when they already entered an advanced stage ( 1 ). According to the WHO, the most common sites of head and neck neoplasms are the oral cavity, the larynx and the pharynx ( 8 ). The highest incidence of head and neck cancer is seen in South East Asia ( 8 ). Head and neck neoplasms are more prevalent in men than women and they most likely appear in the age range of 60–80 years. The average age of diagnosis is 62 years for men and 63 years for women ( 1 ).

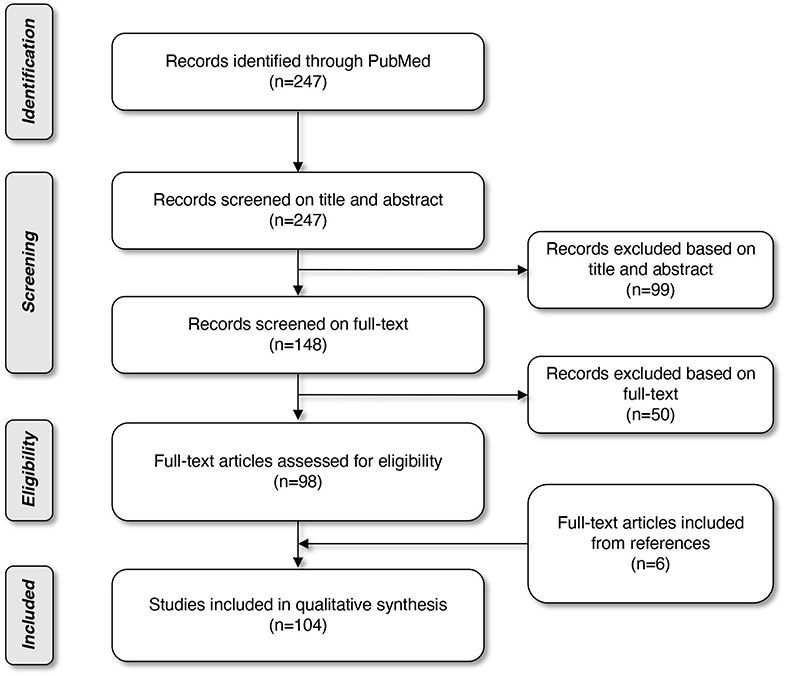

Literature was searched through MEDLINE (PubMed Database). The search started in October 2017 and was limited to papers published in the last decade. The last database search was performed on March 31st, 2019. A combination of the following Mesh terms was used: “biomarkers, tumor”; “head and neck neoplasms”; “early diagnosis”; “volatile organic compounds”; “microbiota”; “papillomaviridae”; “radiomics,” leading to 247 articles. Based on the title and abstract, we selected 148 articles and after reading the full texts and assessing the quality of the texts, we eventually ended up with 102 articles on this topic. The quality of the studies was assessed by three researchers (SS, HK, and MG). To broaden our search and complete our electronic query, reference lists of articles already withheld, were also verified. Six more articles were included through this snowball method. In total, 108 articles were included in this review. The selection procedure is displayed in a flow diagram ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Flow diagram of article selection.

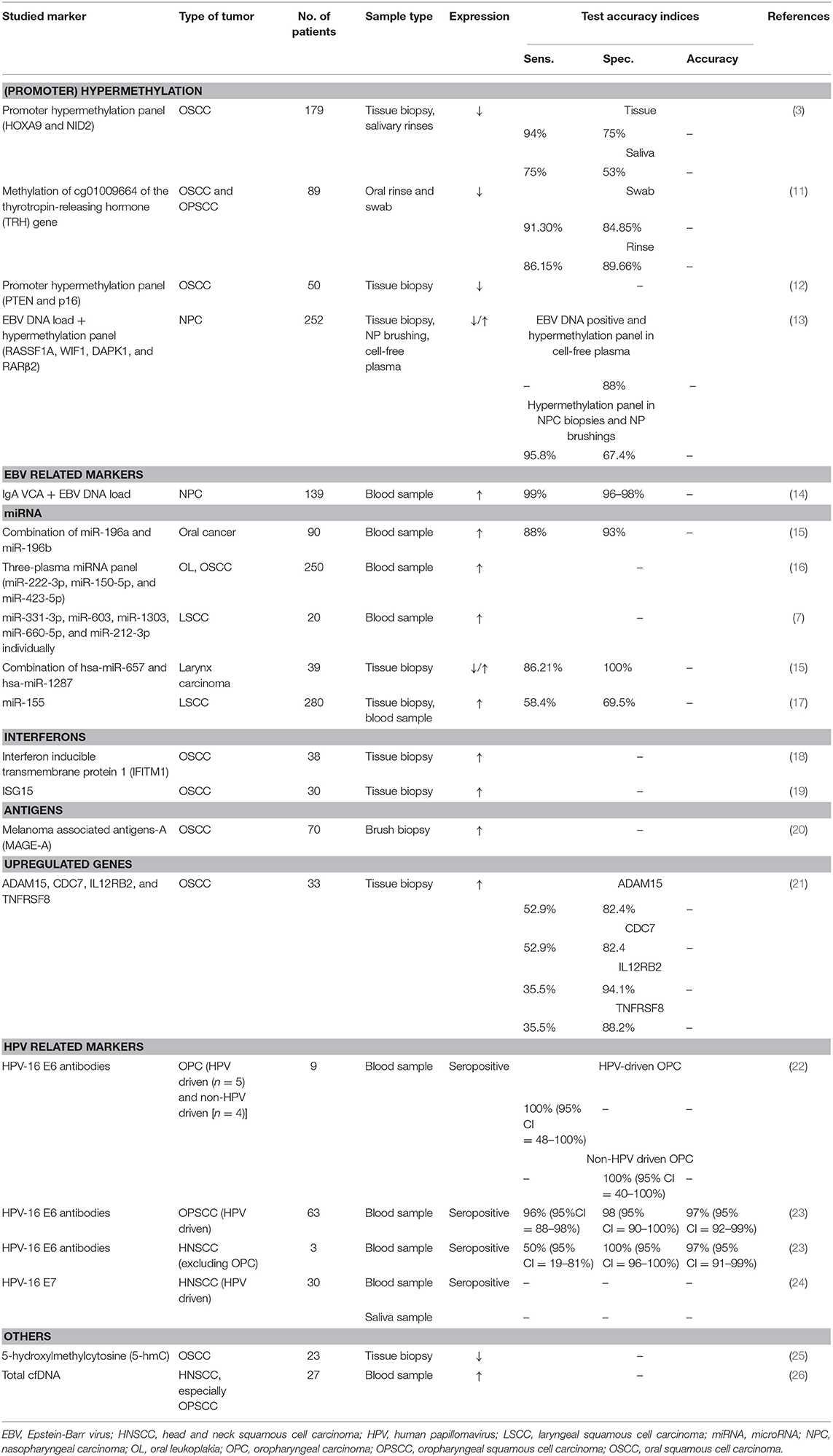

Since head and neck cancers have a poor prognosis and are most frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, finding a biomarker for early diagnosis of these tumors, is of tremendous importance to reduce morbidity and mortality ( 3 , 10 ). Therefore, several biomarkers have been investigated so far. We provide a general overview of known biomarkers for diagnosis of head and neck neoplasms, including a discussion of the most promising markers. Strictly speaking, cancers of the upper part of the esophagus are also part of the head and neck tumors. In this literature review, however, they were not included. In Tables 1 – 8 , all the investigated diagnostic markers with brief additional information are presented. More details about the biomarkers with their restrictions and advantages are provided in the Supplementary Tables 1 – 5 . In the following paragraphs, we will discuss and present the biomarkers based on the applied -omics approach (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, glycomics, volatomics, microbiomics, and radiomics).

Table 1 . Summary of genomics in head and neck neoplasms.

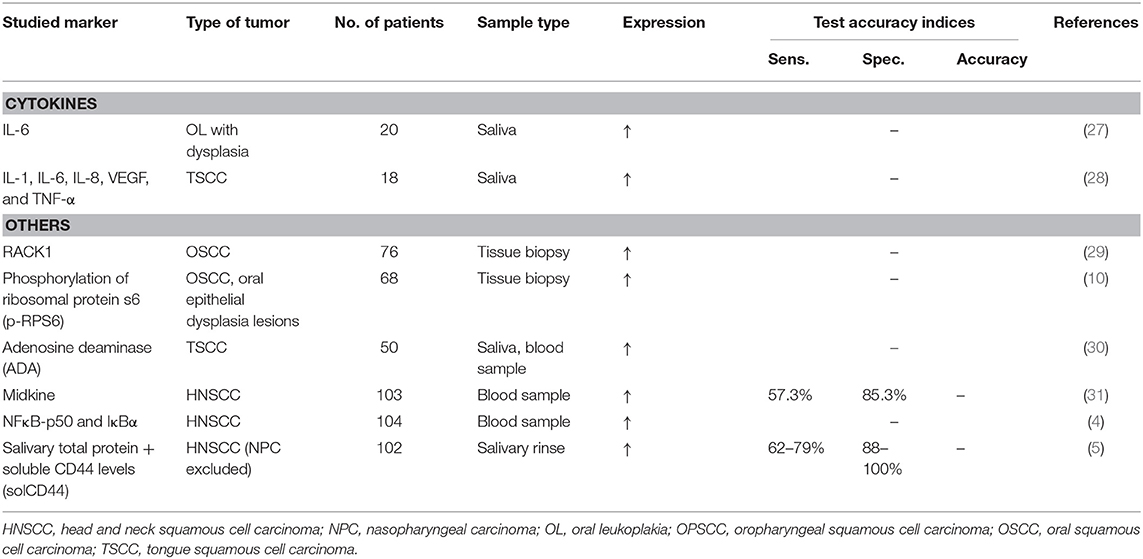

Table 2 . Summary of proteomics in head and neck neoplasms.

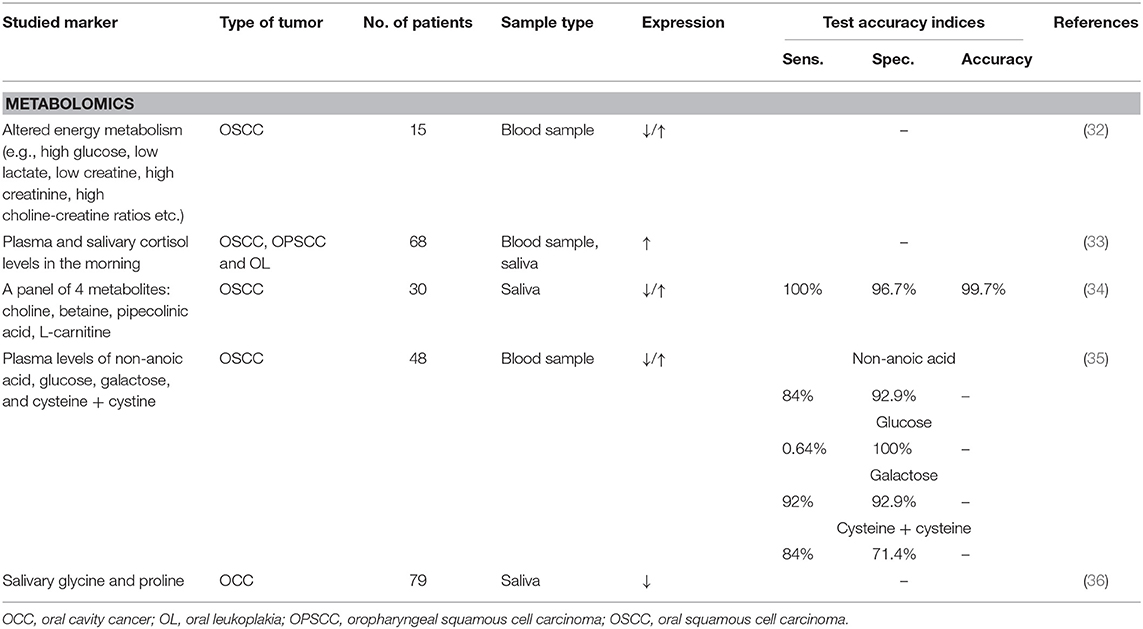

Table 3 . Summary of metabolomics in head and neck neoplasms.

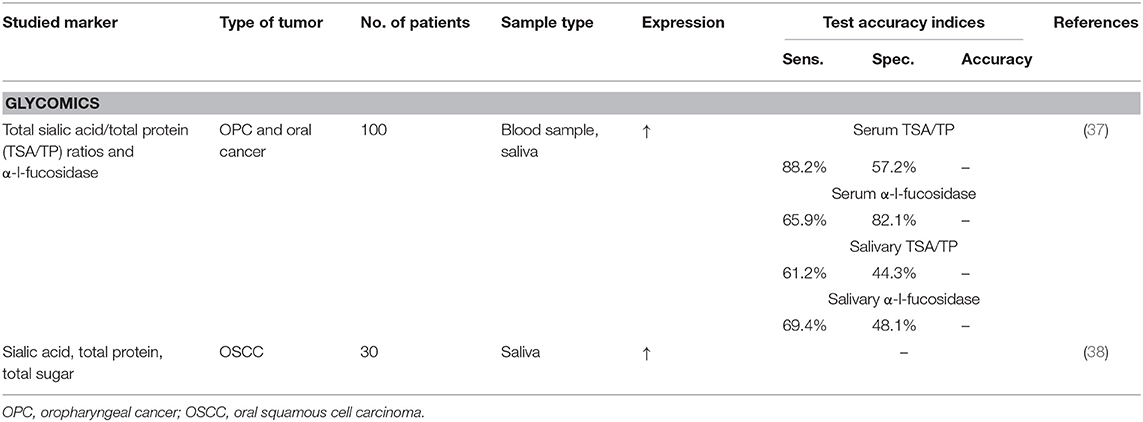

Table 4 . Summary of glycomics in head and neck neoplasms.

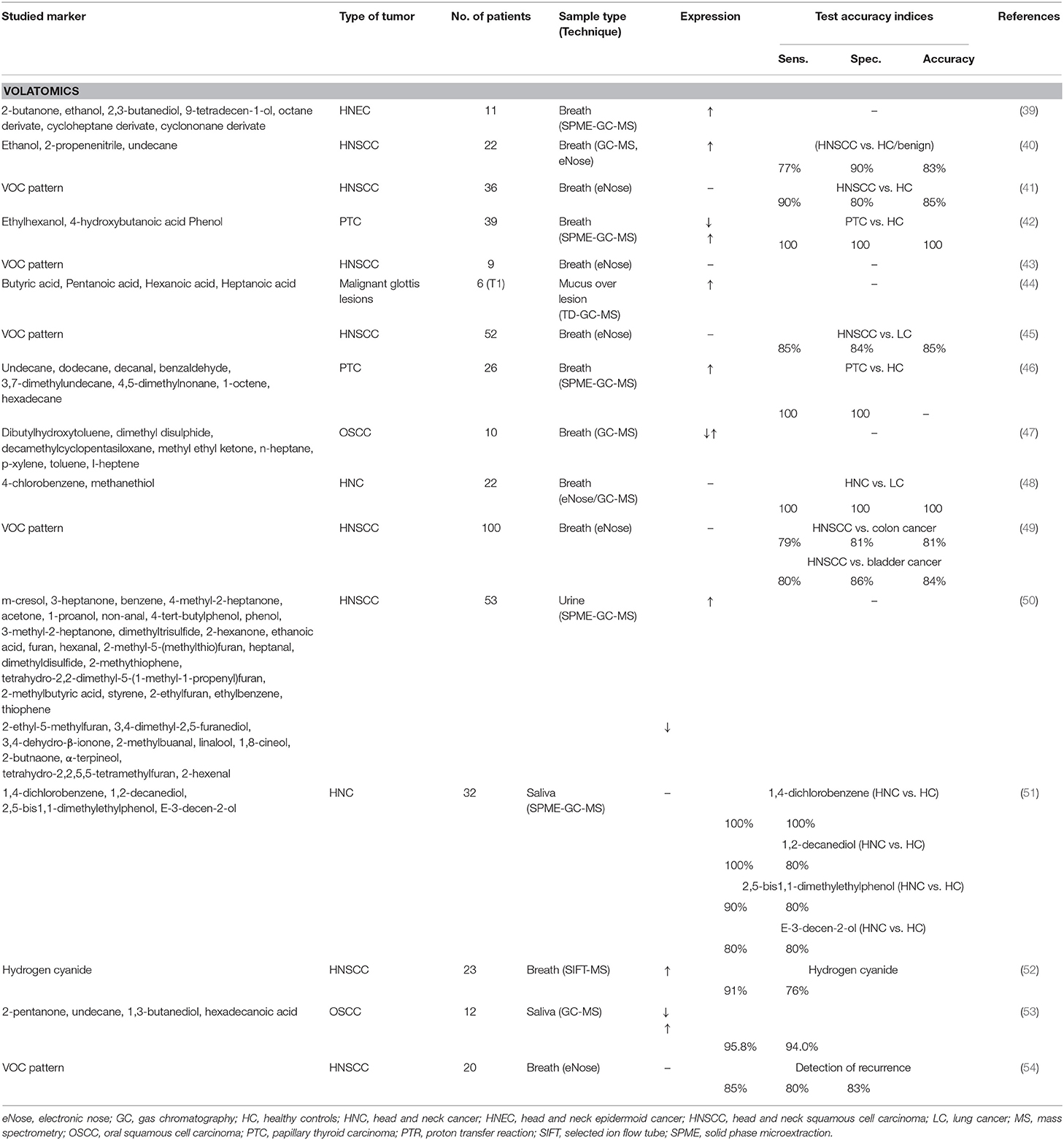

Table 5 . Summary of volatomics in head and neck neoplasms.

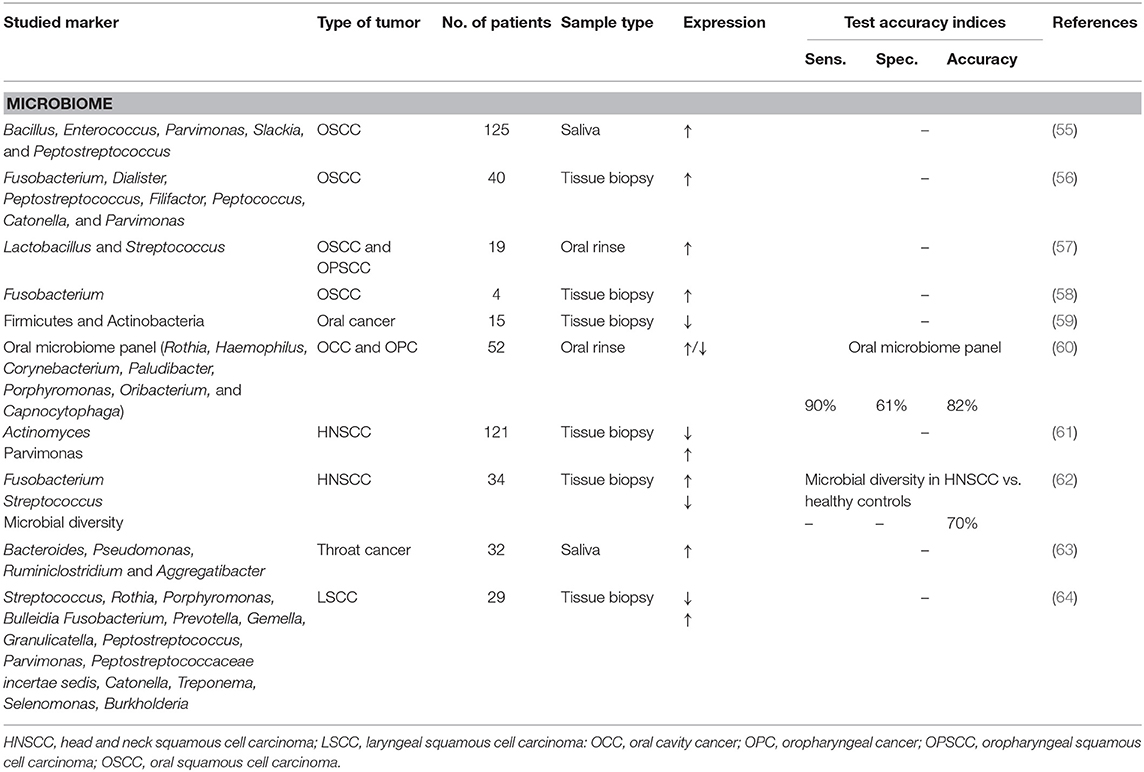

Table 6 . Summary of microbiomics in head and neck neoplasms.

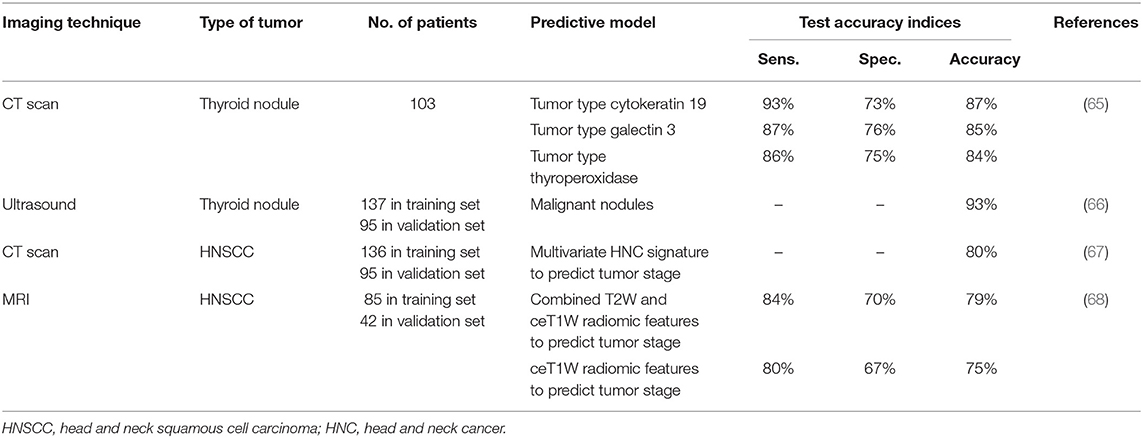

Table 7 . Summary of radiomics in head and neck neoplasms.

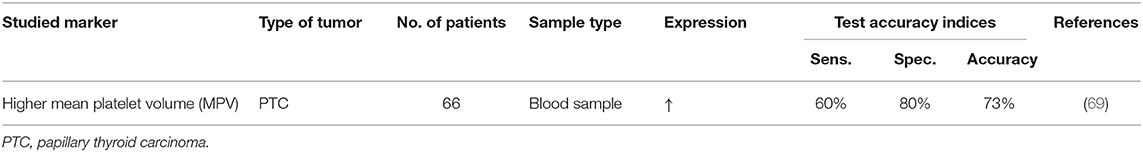

Table 8 . Summary of other biomarkers for head and neck neoplasms.

In the genomic approach, various methods were used to analyze genetic aberrations such as DNA sequencing, single nucleotide polymorphism analysis and hybridization techniques. Changes in gene expression are considered as a potential biomarker. A benefit of this approach is that it might also reveal the disease's underlying cause. On the other hand, there are also some demerits. Cancer is a condition in which many genes interact. Therefore, a single biomarker is probably insufficient to diagnose head and neck cancer and a biomarker panel of genes is recommended. It might also be unclear which post-transcriptional regulatory processes are involved ( 70 ). Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 summarize the biomarkers involving genomics.

Promoter Hypermethylation

Promoter hypermethylation refers to the epigenetic process of abnormal methylation of CpG-islands in the promoter region. The promoter regions of genes initiate gene transcription and are usually not methylated ( 12 ). These alterations are associated with gene silencing in cancer ( 14 ). Methylation is suggested to be an early event in carcinogenesis ( 3 , 14 ), which makes it an interesting candidate as a biomarker. In this manner, early diagnosis is potentially achieved and consequently leads to a better prognosis. Different papers focused on promoter hypermethylation and show that specific genes of patients with head and neck neoplasms have a higher prevalence of methylation in comparison to a healthy control group ( 3 , 6 , 11 , 12 ). Sushma et al. suggest a promoter hypermethylation panel for oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) consisting of the following genes: PTEN and p16 ( 12 ), which can be detected by a tissue biopsy. Guerrero et al. also suggest a promoter hypermethylation panel for detection of OSCC with the genes HOXA9 and NID2, identified via tissue biopsy or salivary rinses ( 3 ). However, despite a high specificity of promoter hypermethylation as a biomarker, its sensitivity was low. Using a panel of genes increased the sensitivity but came at the cost of a lowered specificity. Moreover, in these studies, the included population was small and/or consisted of high-risk patients. Further research would thus be necessary to explore this potential marker.

Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Load

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is closely associated with a latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection ( 13 , 71 ). The EBV DNA load has biomarker potential [sensitivity of 95% (95% CI, 91–98%), specificity of 98% (95% CI, 96–99%) ( 14 )]. The serum concentration correlates to the tumor burden, resulting in a low specificity in early tumor stages but pointing toward the potential of a good prognostic biomarker (high concentrations indicating a greater tumor mass and thus negative prognosis). A combination of the EBV DNA load with a marker for early detection would increase the sensitivity for an early stage detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Yang et al. therefore suggested to combine EBV DNA load with a panel of hypermethylation markers for detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma ( 13 ), since methylation is an early event in carcinogenesis ( 3 , 13 ).

Several antibodies to EBV were also investigated as a biomarker for the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, for example anti-EBV capsid antigen IgA (IgA-VCA) ( 71 ). This is further discussed under the paragraph “proteomics.” Epstein-Barr virus DNA load [95% (95% confidence interval, 91–98%)] and IgA-VCA [sensitivity of 81% (95% CI, 73–87%)] are two of the most sensitive biomarkers found in the peripheral blood of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. When combined, a sensitivity of 99% was obtained. The specificity of EBV DNA and IgA-VCA was 98% (96–99%) and 96% (91–98%), respectively. On top of this, because of their different production mechanism, the combination of both markers could minimize false positive cases ( 14 ). With its high sensitivity and specificity, this biomarker panel of EBV DNA and IgA-VCA seems very promising in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Further prospective validation studies in independent cohorts are needed for confirmation and determination of its position in the diagnostic landscape.

Human Papillomavirus DNA Load

As already mentioned, human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are identified viral risk factors for head and neck neoplasms ( 72 ). Since HPV-16 accounts for >90% of HPV-DNA positive head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC), it is regarded as the predominant HPV type in these specific malignancies ( 73 ). As a result, this is currently the only HPV type that has been studied in HNSCC.

The oral HPV-16 prevalence in healthy individuals is ~1%, suggesting HPV sequences could be used as a biomarker to detect the associated neoplasms ( 73 ). An important association has been demonstrated between HPV and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) on the one hand and some non-oropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinomas on the other hand such as cancers of the oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx ( 73 ). In general, the survival rate was found to be higher for tumors that were HPV-positive compared to the neoplasms that were HPV-negative ( 24 ), stressing the prognostic property. Besides this classification, tumors can also be divided in HPV-driven and non-HPV-driven cancer. HPV-driven malignancies are, amongst other things, characterized by at least one HPV genome copy per tumor cell, as opposed to non-HPV-driven malignancies which express only low copy numbers of HPV DNA ( 23 ). Holzinger et al. state that HPV-driven OPSCC are classified as a distinct tumor entity and have specific characteristics, of which a better patient survival is of the biggest clinical importance ( 23 ). In contrast, patient survival in HPV-positive but non-HPV-driven OPSCC is similar to that of patients with HPV-negative cancer ( 23 ). Kreimer et al. showed, in a small subset of tumor specimens ( n = 9), that the sensitivity of antibodies to HPV-16 oncoprotein E6 (HPV-16 E6) for detection of HPV-driven OPC in blood, was exceptionally high (estimated at 100%, 95% CI = 47.8–100%) with a specificity that was also in this range (estimated at 100%, 95% CI = 39.8–100%) ( 22 ). Holzinger et al. supported this statement and showed that HPV-16 E6 seropositivity had a very high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (98%) to diagnose HPV-driven OPSCC. In contrast, the sensitivity for diagnosis of HNSCC excluding oropharyngeal carcinoma, was much lower (50%, 95% CI = 19–81%) despite the very high specificity (100%, 95% CI = 96–100%) ( 23 ).

Regarding sampling methods, HPV DNA load, and HPV antibodies can be detected in plasma as well as in saliva ( 23 , 24 , 26 , 72 ). Wang et al. demonstrated that HPV DNA could be detected in the plasma of 86% of the patients, compared to only 40% of the saliva of these same patients, indicating that plasma would be more informative to diagnose HPV-associated tumors despite the need for invasive sampling ( 24 ). Indeed, Kreimer et al. found that in OPSCC, the sensitivity for HPV-16 DNA detection in saliva was found to be between 45 and 82% compared to a sensitivity of ≥90% when HPV-16 antibodies were detected in serum ( 73 ).

These HPV-related markers do have their limitations as well. First of all, Kreimer et al. indicate that HPV-P16 E6 seronegative individuals have a low risk of developing HPV-driven OPC but that a screening test for these antibodies in the general population, would still lead to a significant amount of false-positive results. Thus, identifying the population at risk for OPSCC would improve the positive predictive value of this biomarker ( 73 ). Another remark, which is also noticed by Wang et al. and Kreimer et al., is that the published studies consisted of small study groups and studies with greater statistical power are required to determine the possibility of using these HPV related markers in detecting not only neoplasms of the oropharynx, but also the larynx and hypopharynx ( 24 , 73 ).

In the last two decades, altered microRNA expression were studied in different solid tumors and hematological malignancies. These microRNAs are single-stranded non-coding RNAs of 17–25 nucleotides that circulate in cell-free body fluids like blood plasma, serum, saliva, and urine. They can bind to a complementary site in 3′-untranslated regions of the messenger RNA (mRNA), thereby negatively regulating the gene expression via mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. Some microRNAs are upregulated in cancers and are regarded as oncogenes. Others are downregulated and are thus presumed to be tumor suppressor genes. Tumor-derived microRNAs are also released into the blood and might thus be potential early cancer detection markers. Furthermore, these microRNA profiles can be retrieved in a minimally invasive way and they are very stable, up to 28 days, in serum and plasma when stored at −20°C or below ( 7 , 15 ). There is a plethora of papers that studied microRNAs, resulting in a large number of microRNAs that have been identified. MicroRNAs have been studied as a marker for oral cancer ( 15 , 16 ) and larynx cancer ( 7 , 17 , 74 ). Promising results have been observed for a combination of miR-657 and miR-1287 as a marker for larynx carcinoma with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 100% ( 74 ). Nevertheless, the result of this study needs to be interpreted with caution, since it was not yet validated in independent cohorts. The same counts for all other microRNAs that were under investigation in the aforementioned studies.

Interferons-Related Genes

The interferons belong to the family of multifunctional cytokines. These cytokines are produced by host cells in response to microbial infections and tumor cells. When secreted, they initiate a cascade through JAK/STAT signaling (Janus Kinases/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) on their turn resulting in interferon-stimulated gene upregulation. To date, more than 400 interferon-stimulated genes have been reported ( 18 , 19 ). The first one to be recognized was ISG15 and has been described in many tumor biopsies from several cancers including oral squamous cell carcinoma ( 19 ). Due to this fact, it might not be a very specific marker for head and neck neoplasms. Another candidate gene is the interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 1 gene ( 18 ). The exact mechanism resulting in overexpression of interferon-stimulated genes in tumor cells is not yet clarified. Current ongoing studies aim to identify interferon-stimulated genes in diverse tumors including oral squamous cell carcinoma ( 18 ).

A promising approach to identify biomarkers is the study of cell proteins, called proteomics ( 29 , 70 ). Protein markers like carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), prostate specific antigen (PSA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) already earned their place in the diagnosis or progression of several cancer types ( 75 ). In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the following markers have been studied: NFκB-p50, IκB ( 4 ), and the growth factor midkine ( 31 ) by blood sampling, and total salivary protein combined with soluble CD44 levels (solCD44) in saliva ( 5 ). In oral squamous cell carcinoma, a link has been shown with the protein receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) ( 29 ). Furthermore, there is also a place for detection of cytokines in saliva, for example IL-6 in oral leukoplakia or IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, VEGF, and TNF-α in tongue squamous cell carcinoma ( 27 , 28 ). Although some proteins were put forth as a biomarker for oral squamous cell carcinoma, several problems limit their clinical utility. First, there is a substantial heterogeneity of biomarker expression. Second, some proteins are also expressed in other pathologic situations such as inflammatory conditions resulting in a low specificity. Third, different experimental protocols were used which might explain the discrepancy between the identified biomarkers ( 70 ). Because of the heterogeneity of tumor markers in different patients, a combination of proteins might again be a better approach to increase their utility. Although protein markers seem very promising, there has not yet been identified a single or a combination of biomarkers to be effective for clinical use.

Several studies have suggested that autoantibodies that target specific tumor-associated antigens, could possibly be detected years before the tumor can be discovered through incidence screening or radiography ( 76 ). During early carcinogenesis, our immune system tries to remove precancerous lesions by generating an immune response to specific tumor-associated antigens ( 76 , 77 ), which makes them suitable for early detection of cancer lesions. Besides, autoantibodies are found in serum, which is favorable for screening. These individual autoantibodies, however, lack the sensitivity and specificity required for cancer screening ( 14 , 76 ).

First of all, some specific tumor-associated antigens can arise in different types of cancer (e.g., p53) and some of them are also present in diseases other than cancer, especially autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1, systemic lupus erythematosus…). They can also be detected in non-cancer individuals, and because of the heterogenic nature of cancer, a single autoantibody can only be found in 10–30% of patients with the same type of cancer. A panel of specific tumor-associated antigens might hence be the key to raise sensitivity and specificity ( 76 ). As mentioned before, there were several antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) investigated as a biomarker for the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, anti-EBV capsid antigen IgA (IgA-VCA), and anti-EA IgG individually, appeared to have the greatest potential ( 71 ). A combination of IgA-VCA and Epstein-Barr virus DNA load could minimize false positive cases [( 14 ); Table 2 ].

Metabolomics

The term metabolome refers to the identification and quantification of all the small molecule metabolites (<1 kDa) in tissue or biofluids produced during cell metabolism ( 36 ). It is directly linked to cell physiology and thus the result of both physiological and pathological metabolic processes. This explains the current use of metabolomics for discovery of novel biomarkers for cancer diagnosis ( 36 ). However, there are some drawbacks to its use. Because of the high complexity of the metabolome, interpretation of data is difficult, urging the use of deep learning and data mining techniques. There is also a big difference in concentrations ranging for nanomolar to millimolar. Diet, sex, age, drugs, environment, and lifestyle might interfere with the metabolite concentration ( 70 ). There are some papers describing metabolome-related biomarkers in oral cancer. Bernabe et al. found that the plasma and salivary cortisol levels were significantly higher in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma in comparison with healthy controls and patients with oral leukoplakia ( 33 ). Large validation studies remain indispensable to confirm the value of metabolites in the diagnosis of head and neck neoplasms. To date, research on metabolites as a potential biomarker is still in the discovery phase.

Compared to genomics and proteomics, there is few research on glycomics. This approach focuses on the modifications of glycoconjugates related to cancer. Glycolipids and glycoproteins are glycoconjugates and are important constituents of the cell membrane. Glycosylation is important in the process of protein modification and its action relies on the function of glycosyltransferases and glycosidases in various tissues and cells. Glycoconjugates are released into the circulation because of continuously shedding and/or secretion by cancer cells or the increased cell turnover and could thus be detected in body fluids to be used as tumor markers. Especially glycoconjugates in oral cancer, which are in direct contact with saliva, seem to be promising. The major types of glycosylation are sialylation and fucosylation, which terminally modify proteins that are important in the vital biological functions. There have been reported significantly elevated levels of sialic acid, α-l-fucosidase, and total protein in oral cancer patients and there is also a link with oral cancer progression. However, there is need for further research to determine the role of these biomarkers in oral cancer development ( 37 , 38 ).

Volatomics recently emerged as new research field for early disease diagnosis. This encompasses volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in nano- to picomolar concentrations, which are the gaseous end products from endogenous metabolic changes, digestion, microbiome, inflammation, and oxidative stress. VOCs can be detected in breath, urine, feces, blood, saliva, skin, and sweat, and hence, serve as attractive biomarkers, as it is completely non-invasive, relatively cheap, and provides rapid results ( 78 ). VOCs have already shown clinical potential as biomarkers for lung ( 79 ), gastric ( 80 ), breast ( 81 ), prostate ( 82 ), and mesothelioma cancer ( 83 ), and since carcinogenesis is related to inflammation and metabolic changes, VOCs could also have added value as diagnostic biomarkers for head and neck cancer ( Table 5 ).

The study of VOCs in exhaled breath (breathomics) is potentially the most important since the sample is unlimitedly present and sampling causes no side effects for the patient. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), García et al. found an increase of 2-butanone, ethanol, 2,3-butanediol, 9-tetradecen-1-ol, and octane, cycloheptane, and cyclononane derivates in the breath of head and neck cancer patients compared to healthy controls [( 39 ); Table 5 ]. The increase in ethanol was also found in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients by Gruber et al., next to 2-propenenitrile and undecane ( 40 ), which discriminated patients from healthy controls and even patients with benign conditions with 77% sensitivity and 90% specificity. Hydrogen cyanide was found to be increased in the breath of HNSCC patients compared to controls using SIFT-MS and allowed discrimination with 91% sensitivity and 76% specificity ( 52 ).

The VOCs 4-chlorobenzene and methanethiol discriminated HNSCC patients from lung cancer patients with 100% accuracy ( 48 ), showing potential to use breath analysis for differential diagnosis, albeit with low study participants and a risk of overfitting the differentiating models.

Next to spectrometric analysis, VOCs can be detected by sensor technology [electronic noses (eNoses)] that recognizes the bulk of VOCs as a breath print, but without identifying individual VOCs. Using eNoses, HNSCC patients could be differentiated from controls with sensitivities and specificities ranging between 77–90% and 80–90%, respectively, underlining the difference in breath print and their use as diagnostic tool ( 40 , 41 , 43 ). Also, eNoses have shown to be promising for differential diagnosis, in which the breathprint of HNSCC patients was different from those with lung cancer, colon cancer and bladder cancer with, respectively, 85, 79, and 80% sensitivity and 84, 81, and 86% specificity ( 45 , 49 , 54 ).

Two studies discriminated patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) from healthy controls with both 100% sensitivity and specificity ( 42 ). Although one based this discrimination on an increase of ethyl hexanol, 4-hydroxybutanoic acid, and a decrease in phenol ( 42 ), the other did not report changes in these compounds ( 46 ).

Differences in dibutylhydroxytoluene, dimethyl disulphide, decamethylcyclopentasiloxane, methyl ethyl ketone, n-heptane, p-xylene, toluene, I-heptene were found in breath between patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma and controls ( 47 ). However, based upon VOCs from saliva in these patients, an increase in 1,3-butanediol and hexadecenoic acid and a decrease in 2-pentanone and undecane allowed their discrimination from healthy controls with 96% sensitivity and 95% specificity ( 53 ). This decrease of undecane is in contrast to an increase found in breath in HNSCC ( 40 ) and patients with PTC ( 46 ). Furthermore, saliva analysis of the single VOCs 1,4-dichlorobenzene, 1,2-decanediol, 2,5-bis1,1-dimethylethylphenol, and E-3-decen-2-ol allowed to discriminate HNSCC patients from controls with a sensitivity and specificity between 80–100% and 80–100%, respectively ( 51 ), again being different to VOCs found in exhaled breath and urine ( 50 ).

Lastly, analysis of VOCs from the mucus of 6 patients with malignant glottic lesions found butyric acid, pentanoic acid, hexanoic acid, and heptanoic acid to be different compared to controls ( 44 ).

Carcinogenesis is related to an altered metabolism, upregulated aerobic glycolysis (known as the Warburg effect) and induces oxidative stress ( 84 , 85 ). This liberates highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) which induce lipid peroxidation of (poly)unsaturated omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids (PUFA) in the cellular membranes, mainly generating alkanes and aldehydes as end products ( 86 ). Considering the high number of hydrocarbons detected in several matrices, this plays a major role in HNC and therefore, are biomarkers of interest. Aldehydes are furthermore generated in vivo in signal transduction, genetic regulation and cellular proliferation. In cancer, an increase in aldehyde dehydrogenase is seen as malignant cells proliferate. This causes aldehyde oxidation, resulting in an increased aldehyde concentration in blood and breath, which is reflected by the large number of aldehydes found in these matrices. However, longer chain aldehydes are potentially by-products of digestion and their origin needs to be explored. Also, several organic (carboxylic) acids have been found, which are the main products of proteolysis. Alcohols have 2 major pathways to be induced in vivo : by ingestion or as product from the hydrocarbon metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzymes and the alcohol dehydrogenase activity ( 86 ). Alcohols, next to carboxylic acids, are products of hydrolysis of esters. The cytochrome P450 enzymes hydroxylate lipid peroxidation biomarkers to produce alcohols, which are found by several studies. Special attention can be given to phenol: although phenol may be derived from benzene metabolism, it is most likely to be from exogenous origin, since it is a by-product of the sampling materials used.

Taken together, it seems that not one VOC is able to accurately discriminate between several types of head and neck cancer types and controls. Hence, the combination of several biomarkers into panels will therefore be key in future research as stressed by the success of eNoses that react to the bulk of VOCs in the breath and the success of biomarker panels. However, the discordance in VOCs can be explained due to a difference in technology, sampling and by the difference in concentration range. Furthermore, as with metabolites, the volatilome delivers high throughput data, complicating the interpretation of the data, and urging the use of deep learning and data mining techniques. Next to this, also diet, sex, age, drugs, environment, and lifestyle, and the microbiome can interfere with the VOC concentration and induce changes. Hence, the external influence may not be underestimated. In several trials, ethanol, and 2-propenenitrile have been identified as possible biomarkers. However, these can be linked to alcohol abuse and smoking, which are both risk factors for HNSCC, and could therefore have biased the results if not corrected for this. Furthermore, the finding that hydrogen cyanide can serve as biomarker raises concerns about the origin of this VOC and its correlation with HNSCC since hydrogen cyanide is known to be released by the microbiome and could result from exogenous exposure to exhausted fumes and cigarette smoke. Despite this, it can also be a by-product of cellular respiration. Hence, for multiple VOCs, their origin and its role as diagnostic marker remains to be determined.

Microbiomics

The human body is colonized by numerous microbes that include viruses, bacteria and microbial eukaryotes. Studying these microbial communities is referred to as “microbiomics” ( 64 ). The microbiome maintains homeostasis and has a dynamic association with the human host ( 61 , 62 ). When dysbiosis or ecological imbalance arises, processes leading to a diseased state develop ( 62 ). Some studies that have already been published, showed an association between microbiome variations and cancer. These studies have demonstrated that the mucosal layers of the mouth, throat, stomach, and intestines are colonized by commensal bacteria, which play an important part in normal human health and can therefore also play a role in the development of malignancies. For example, Helicobacter pylori infection can induce gastric cancer through gastric dysbiosis ( 63 ).

To date, few has been published about microbiomics as a (diagnostic) biomarker in head and neck cancer. Most studies focus on the oral microbiome, which can be used in the detection of oral cancer, especially oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) ( 55 ). There are many bacterial species in the oral cavity involved in the genesis of oral cancer which can be explained through inflammation-induced DNA damage of epithelial cells caused by endotoxins secreted by these micro-organisms ( 55 ). The link between microorganisms and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is not yet adequately studied ( 57 ). There are some studies that have detected oral microbial alternations in consumers of alcohol, tobacco and betel nut. The association between these known oral cancer risk factors and microbial alterations should be taken into account ( 55 , 61 ). It could be possible that the microbiome helps change an environmental exposure into a carcinogenic effect ( 61 ). Lee et al. studied microbial differences between oral cancer patients, patients with epithelial precursor lesions and healthy controls ( 55 ). They found a significant abundance of 5 genera in the salivary microbiome ( Bacillus, Enterococcus, Parvimonas, Slackia , and Peptostreptococcus ) of cancer patients when compared to patients with epithelial precursor lesions. These changes in the composition of the microbiome could thus be a potential biomarker for monitoring the transformation of oral precursor lesions into oral cancer ( 55 ). The use of a microbiome panel ( Rothia, Haemophilus, Corynebacterium, Paludibacter, Porphyromonas, Oribacterium , and Capnocytophaga ) could detect oral cavity cancer and oropharyngeal cancer by oral rinse with an accuracy of 82% ( 60 ).

The association between variations in the human microbiome and throat cancer has also been studied. Wang et al. studied microbial markers in the saliva of patients with throat cancer (hypopharyngeal carcinoma and laryngeal carcinoma) and in the saliva of patients with vocal cord polyps and healthy controls ( 63 ). They revealed a significant difference in the microbiome of throat cancer patients vs. patients with vocal cord polyps and healthy controls. The following genera were found to be associated with throat cancer: Bacteroides, Pseudomonas, Ruminiclostridium , and Aggregatibacter . Additionally, they observed a significant reduction in microbial diversity in throat cancer patients ( 63 ). This reduction in diversity of the microbiome is also found in other studies concerning oral cancer ( 57 , 60 ) and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) ( 62 ). Zhao et al. on the other hand, observed a greater bacterial diversity in OSCC tissue when compared to healthy tissue ( 56 ).

Table 7 shows potential microbial biomarkers for head and neck cancer. Few studies have shown that the expression of Fusobacterium is elevated in the tumor tissue of patients with OSCC ( 56 , 58 ) and HNSCC ( 62 ).

Although studies of bacteria and their role in carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer are increasing rapidly, the association between microbiome and head and neck cancer has not been substantially studied. The published studies do not specifically focus on early diagnosis of head and neck neoplasms and have only identified some potential biomarkers based on difference in expression between head and neck cancer populations and (healthy) control populations. These studies also use different sequencing technologies to measure the abundance of microbiota. There is need for further, more standardized research before microbial variations can be considered a diagnostic biomarker for head and neck neoplasms.

Radiomics comprises the high-throughput mining of advanced quantitative features to objectively and quantitatively describe tumor phenotypes. It makes use of standard of care radiologic images which are subject to advanced mathematical algorithms to detect tumor characteristics that might be missed by the radiologist's eye. This method relies on big data and supports the clinical decision to diagnose, prognose, and predict -amongst others- cancer ( 87 ). Yip and Aerts extensively reviewed the applications and limitations of this new -omics approach ( 88 ). We kindly refer to their paper for detailed information.

In head and neck cancer, radiomics has also entered the scene. Here, we focus on papers that aimed to diagnose HNC based on radiomics features. In patients with a thyroid nodule, a radiomics score (calculated from ultrasound images) was evaluated against the standard method used for the diagnosis of thyroid nodules as set by the American College of radiology, the TI-RADS score. The radiomics score was able to discriminate malignant from benign nodules with an accuracy of 93% [95% CI 88.4–97.7%]. The radiomics score performed better compared to the TI-RADS if scored by junior radiologists ( 66 ). In a similar population, a radiomics predictive model was constructed based on computer tomography (CT) images which was able to predict the immunohistochemical characteristics of suspected thyroid nodules [cytokeratin 19 (AUC 0.87, sensitivity 93%, and specificity 73%), galectin 3 (AUC 0.85, sensitivity 87%, and specificity 76%), and thyroperoxidase (AUC 0.84, sensitivity 86%, and specificity 75%)] ( 65 ). It seems clear that radiomics will become a meritorious player in the diagnostic landscape of thyroid cancer. Given the high prevalence of -largely benign- thyroid nodules, a good biomarker to discriminate benign from malignant nodules is indispensable. From the papers published to date, radiomics seems promising as a biomarker in this field.

Parmar et al. were able to identify 10 radiomic clusters in a dataset of CT images from 136 patients with HNSCC that were significantly associated with tumor stage ( 67 ). In addition, they created an HNC signature based on multivariate analysis that was highly predictive for tumor stage (AUC = 0.80). In a similar population consisting of 127 HNSCC patients, Ren et al. used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) axial fact-suppressed T2-weighted (T2W) and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (ceT1W) images to identify a radiomics signature for preoperative staging (I-II vs. III-IV). The radiomics signature based on ceT1W images (AUC 0.853) performed best in discriminating stage I-II from stage III-IV followed by combined T2W and ceT1W images (AUC 0.849) ( 68 ). In the training cohort, radiomics performed better than visual assessment by an experienced radiologist, however, this was no longer the case in the testing cohort. In a recent paper of Huang et al., the radiomics' potential to identify treatment-relevant subtypes of HNSCC was tested on pretreatment CT scans in a cohort of 113 patients. Moderate AUC's varying from 0.71 to 0.79 were observed in the prediction of HPV positivity, three DNA methylation subtypes and a mutation of NSD1 in these patients ( 89 ). Radiomics might thus be of additional value to define subtypes in a non-invasive manner. However, several tumors will be misclassified based on radiomics alone, making the diagnostic capacity underperforming.

Besides tumor diagnosis, radiomics is also subject of investigation in predictive ( 90 – 92 ) and prognostic models ( 67 , 93 – 96 ), to evaluate local tumor control ( 97 – 99 ), and HPV status ( 100 , 101 ).

A challenge in radiomics remains the fact that the extracted feature quality is affected by tumor segmentation methods used to define regions over which to calculate features. Consistent radiomics analysis across multiple institutions that use different segmentation algorithms are not obvious. This is particularly the case for Positron Emission Tomography (PET), where a limited resolution, a high noise component related to the limited stochastic nature of the raw data, and the wide variety of reconstruction options might confound quantitative feature metrics ( 102 ). Standardized scanner protocols and image reconstruction harmonization are thus of tremendous importance to make the transfer of radiomics features possible between institutions. Several papers already tried to identify the pitfalls of radiomics and the relevant features that delay interchangeability to make sure that radiomics becomes a full-fledged biomarker in future cancer diagnosis ( 103 ).

Mean platelet volume (MPV) was found to be significantly higher in PTC patients when compared to benign goiter patients and health controls (8.05, 7.57, and 7.36 fl, respectively; p = 000.1; see Table 8 ). Moreover, MPV significantly decreased when these patients were surgically treated [8.05 vs. 7.60 fl; p = 0.005; ( 69 )]. The quality of this study however was suboptimal. The study was retrospective and had a relatively small sample size [ n = 66; ( 69 )].

In this review, we assessed a large number of potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of head and neck neoplasms and included tables providing a detailed overview of the state-of-the-art investigated biomarkers. All proposed biomarkers have their advantages and restrictions. Many biomarkers lack the sensitivity and/or specificity that is required for utilization in the clinical practice. Therefore, individual biomarkers are frequently combined into biomarker panels to increase these diagnostic values.

Furthermore, many studies had a relatively small sample size and therefore lacked statistical power. Additionally, a great amount of these studies was retrospective. Larger, prospective studies should thus be performed in the future. Also, other elements should be kept in mind when planning future biomarker research. For example, a considerable part of the studies that were reviewed included healthy controls as control population. However, one should recognize that biomarkers in the clinical practice would be used in patients at risk for certain types of head and neck neoplasms. Future studies should thus consider including appropriate patients at risk and/or patients known with a premalignant lesion when composing their control population. Most of the described markers have been studied for one specific type of head and neck neoplasm and can therefore not be extrapolated to head and neck neoplasms in general. The diagnostic biomarkers that were reviewed, were frequently studied in patients from one specific geographical location. As a consequence, the biomarker might be influenced by race, genetics, lifestyle, and carcinogenic exposure ( 104 ). India is a high-risk region for the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma ( 12 , 18 , 19 , 38 ). Hence, a biomarker that has been evaluated in an Indian community might be applicable only to high-risk regions. The study groups should thus also investigate this marker in another population that is less at risk for the occurrence of oral squamous cell carcinoma and study its applicability worldwide. Also, other variables such as race, eating habits and environmental exposure should be taken into account. In this manner, when reviewing the literature, we noticed a large amount of variability when studying biomarkers for head and neck cancer. Standardized research would therefore be a necessity when considering future studies concerning these tumors.

The sampling method of the biomarkers and the analysis of the specimen also play a determining role in the utilization of the marker in the clinical practice. For example, saliva and exhaled breath present an attractive non-invasive alternative to tissue or serum testing. Serum is easily accessible, relatively cheap, and can be used in a minimally invasive way, but saliva and breath offer some other advantages. A non-health practitioner can easily collect these samples in a non-invasive way, they are easy to store, the sample cost is relatively low and repeated (unlimited) samples can easily be acquired because it is a comfortable sampling method for patients ( 34 , 37 ).

To our opinion, microRNA, gene hypermethylation, HPV-related markers, and a panel of proteins seem to be the biomarkers with the most promising potential of becoming a diagnostic biomarker for head and neck neoplasms based on the reported sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values that can be obtained. In certain tumor types, such as thyroid cancer, also radiomics might become of importance in the diagnostic landscape and replace invasive needle biopsies. Hereto, radiomic signatures need to be identified that are able to discriminate benign from malignant lesions. A challenge here is to make the radiomic signatures interchangeable between institutes. Biomarkers studying the metabolome, glycome, volatilome, and microbiome still need to be thoroughly investigated before they can be considered as biomarkers.

Most of the head and neck tumors are diagnosed in an advanced stage. Hence, besides advancement in treatment of head and neck neoplasms, early detection of these tumors could play a significant role in improving the prognosis of these patients. With this in mind, a lot of research has already been done on clinically applicable single biomarkers or a panel of biomarkers, for early detection of head and neck tumors. We reviewed over 50 markers, all with their advantages and limitations. To date, a biomarker to diagnose head and neck neoplasms useful for clinical practice, has not yet been identified nor validated. Therefore, further research of biomarkers to diagnose head and neck neoplasms in an early stage is still needed.

Author Contributions

HK, SS, and MG collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data after which they drafted the article. This excludes the part concerning volatomics, which should be accredited to KL and the part concerning radiomics, which should be accredited to KJL. KJL, KL, JM, OV, BD, and PS did a critical revision of the article and gave their final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Antwerp, Belgium, for their guidance and support regarding this literature review.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.01020/full#supplementary-material

1. De Vries N, van De Heyning PH, Leemans CR. Leerboek Keel-Neus-Oorheelkunde en hoofd-halschirurgie. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum (2013). doi: 10.1007/978-90-313-9807-2

CrossRef Full Text

2. van De Velde CJH, van Der Graaf WTA, van Krieken JHJM, Marijnen CAM, Vermorken JB. Oncologie. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. (2011). doi: 10.1007/978-90-313-8476-1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Guerrero-Preston R, Soudry E, Acero J, Orera M, Moreno-Lopez L, Macia-Colon G, et al. NID2 and HOXA9 promoter hypermethylation as biomarkers for prevention and early detection in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma tissues and saliva. Cancer Prev Res . (2011) 4:1061–72. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Gupta A, Kumar R, Sahu V, Agnihotri V, Singh AP, Bhasker S, et al. NFkappaB-p50 as a blood based protein marker for early diagnosis and prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2015) 467:248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.09.181

5. Franzmann EJ, Reategui EP, Pereira LH, Pedroso F, Joseph D, Allen GO, et al. Salivary protein and solCD44 levels as a potential screening tool for early detection of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. (2012) 34:687–95. doi: 10.1002/hed.21810

6. Lingen MW. Screening for oral premalignancy and cancer: what platform and which biomarkers? Cancer Prev Res . (2010) 3:1056–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0173

7. Ayaz L, Gorur A, Yaroglu HY, Ozcan C, Tamer L. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: potential early-detection markers for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2013) 139:1499–506. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1469-2

8. Mehanna H, Paleri V, West CML, Nutting C. Head and neck cancer—part 1: Epidemiology, presentation, and prevention. BMJ. (2010) 341:c4684. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4684

9. Harrison LB, Sessions RB, Hong WK. Head and Neck Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 3rd Edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (2009).

Google Scholar

10. Chaisuparat R, Rojanawatsirivej S, Yodsanga S. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation is associated with epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Pathol Oncol Res. (2013) 19:189–93. doi: 10.1007/s12253-012-9568-y

11. Puttipanyalears C, Arayataweegool A, Chalertpet K, Rattanachayoto P, Mahattanasakul P, Tangjaturonsasme N, et al. TRH site-specific methylation in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. (2018) 18:786. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4706-x

12. Sushma PS, Jamil K, Kumar PU, Satyanarayana U, Ramakrishna M, Triveni B. PTEN and p16 genes as epigenetic biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC): a study on south Indian population. Tumour Biol. (2016) 37:7625–32. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4648-8

13. Yang X, Dai W, Kwong DL, Szeto CY, Wong EH, Ng WT, et al. Epigenetic markers for noninvasive early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by methylation-sensitive high resolution melting. Int J Cancer. (2015) 136:E127–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29192

14. Leung SF, Tam JS, Chan AT, Zee B, Chan LY, Huang DP, et al. Improved accuracy of detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by combined application of circulating Epstein-Barr virus DNA and anti-Epstein-Barr viral capsid antigen IgA antibody. Clin Chem. (2004) 50:339–45. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022426

15. Lu YC, Chang JT, Huang YC, Huang CC, Chen WH, Lee LY, et al. Combined determination of circulating miR-196a and miR-196b levels produces high sensitivity and specificity for early detection of oral cancer. Clin Biochem. (2015) 48:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.11.020

16. Chang YA, Weng SL, Yang SF, Chou CH, Huang WC, Tu SJ, et al. A three-microRNA signature as a potential biomarker for the early detection of oral cancer. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:758. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030758

17. Wang JL, Wang X, Yang D, Shi WJ. The expression of microRNA-155 in plasma and tissue is matched in human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Yonsei Med J. (2016) 57:298–305. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.298

18. Ramanathan A, Ramanathan A. Interferon induced transmembrane protein-1 gene expression as a biomarker for early detection of invasive potential of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2016) 17:2297–9. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.4.2297

19. Laljee RP, Muddaiah S, Salagundi B, Cariappa PM, Indra AS, Sanjay V, et al. Interferon stimulated gene-ISG15 is a potential diagnostic biomarker in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2013) 14:1147–50. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.2.1147

20. Ries J, Mollaoglu N, Toyoshima T, Vairaktaris E, Neukam FW, Ponader S, et al. A novel multiple-marker method for the early diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Markers. (2009) 27:75–84. doi: 10.1155/2009/510124

21. Yong-Deok K, Eun-Hyoung J, Yeon-Sun K, Kang-Mi P, Jin-Yong L, Sung-Hwan C, et al. Molecular genetic study of novel biomarkers for early diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2015) 20:e167–79. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20229

22. Kreimer AR, Johansson M, Yanik EL, Katki HA, Check DP, Lang Kuhs KA, et al. Kinetics of the human papillomavirus type 16 E6 antibody response prior to oropharyngeal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2017) 109:djx005. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx005

23. Holzinger D, Wichmann G, Baboci L, Michel A, Hofler D, Wiesenfarth M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of antibodies against HPV16 E6 and other early proteins for the detection of HPV16-driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. (2017) 140:2748–57. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30697

24. Wang Y, Springer S, Mulvey CL, Silliman N, Schaefer J, Sausen M, et al. Detection of somatic mutations and HPV in the saliva and plasma of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Sci Transl Med. (2015) 7:293ra104. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa8507

25. Cuevas-Nunez MC, Gomes CBF, Woo SB, Ramsey MR, Chen XL, Xu S, et al. Biological significance of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in oral epithelial dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2018) 125:59–73.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.06.006

26. Mazurek AM, Rutkowski T, Fiszer-Kierzkowska A, Malusecka E, Skladowski K. Assessment of the total cfDNA and HPV16/18 detection in plasma samples of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Oral Oncol. (2016) 54:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.12.002

27. Sharma M, Bairy I, Pai K, Satyamoorthy K, Prasad S, Berkovitz B, et al. Salivary IL-6 levels in oral leukoplakia with dysplasia and its clinical relevance to tobacco habits and periodontitis. Clin Oral Investig. (2011) 15:705–14. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0435-5

28. Korostoff A, Reder L, Masood R, Sinha UK. The role of salivary cytokine biomarkers in tongue cancer invasion and mortality. Oral Oncol. (2011) 47:282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.02.006

29. Wang Z, Jiang L, Huang C, Li Z, Chen L, Gou L, et al. Comparative proteomics approach to screening of potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Proteomics. (2008) 7:1639–50. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700520-MCP200

30. Rai B, Kaur J, Jacobs R, Anand SC. Adenosine deaminase in saliva as a diagnostic marker of squamous cell carcinoma of tongue. Clin Oral Investig. (2011) 15:347–9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0404-z

31. Yamashita T, Shimada H, Tanaka S, Araki K, Tomifuji M, Mizokami D, et al. Serum midkine as a biomarker for malignancy, prognosis, and chemosensitivity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. (2016) 5:415–25. doi: 10.1002/cam4.600

32. Tiziani S, Lopes V, Gunther UL. Early stage diagnosis of oral cancer using 1H NMR-based metabolomics. Neoplasia. (2009) 11, 269–76. doi: 10.1593/neo.81396

33. Bernabe DG, Tamae AC, Miyahara GI, Sundefeld ML, Oliveira SP, Biasoli ER. Increased plasma and salivary cortisol levels in patients with oral cancer and their association with clinical stage. J Clin Pathol. (2012) 65:934–9. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200695

34. Wang Q, Gao P, Wang X, Duan Y. Investigation and identification of potential biomarkers in human saliva for the early diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta. (2014) 427:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.10.004

35. Enomoto Y, Kimoto A, Suzuki H, Nishiumi S, Yoshida M, Komori T. Exploring a novel screening method for patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a plasma metabolomics analysis. Kobe J Med Sci. (2018) 64:E26–35.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

36. Lohavanichbutr P, Zhang Y, Wang P, Gu H, Nagana Gowda GA, Djukovic D, et al. Salivary metabolite profiling distinguishes patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma from normal controls. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0204249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204249

37. Vajaria BN, Patel KR, Begum R, Shah FD, Patel JB, Shukla SN, et al. Evaluation of serum and salivary total sialic acid and alpha-l-fucosidase in patients with oral precancerous conditions and oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2013) 115:764–71. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.01.004

38. Sanjay PR, Hallikeri K, Shivashankara AR. Evaluation of salivary sialic acid, total protein, and total sugar in oral cancer: a preliminary report. Indian J Dent Res. (2008) 19:288–91. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.44529

39. García R, Morales V, Martín S, Vilches E, Toledano A. Volatile organic compounds analysis in breath air in healthy volunteers and patients suffering epidermoid laryngeal carcinomas. Chromatographia. (2014) 77:501–9. doi: 10.1007/s10337-013-2611-7

40. Gruber M, Tisch U, Jeries R, Amal H, Hakim M, Ronen O, et al. Analysis of exhaled breath for diagnosing head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a feasibility study. Br J Cancer. (2014) 111:790–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.361

41. Leunis N, Boumans ML, Kremer B, Din S, Stobberingh E, Kessels AG, et al. Application of an electronic nose in the diagnosis of head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. (2014) 124:1377–81. doi: 10.1002/lary.24463

42. Guo L, Wang C, Chi C, Wang X, Liu S, Zhao W, et al. Exhaled breath volatile biomarker analysis for thyroid cancer. Transl Res. (2015) 166:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.01.005

43. Lang HP, Loizeau F, Hiou-Feige A, Rivals JP, Romero P, Akiyama T, et al. Piezoresistive membrane surface stress sensors for characterization of breath samples of head and neck cancer patients. Sensors . (2016) 16:1149. doi: 10.3390/s16071149

44. Shoffel-Havakuk H, Frumin I, Lahav Y, Haviv L, Sobel N, Halperin D. Increased number of volatile organic compounds over malignant glottic lesions. Laryngoscope. (2016) 126:1606–11. doi: 10.1002/lary.25733

45. van Hooren MR, Leunis N, Brandsma DS, Dingemans AC, Kremer B, Kross KW. Differentiating head and neck carcinoma from lung carcinoma with an electronic nose: a proof of concept study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2016) 273:3897–903. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4038-x

46. Bouza M, Gonzalez-Soto J, Pereiro R, De Vicente JC, Sanz-Medel A. Exhaled breath and oral cavity VOCs as potential biomarkers in oral cancer patients. J Breath Res. (2017) 11:016015. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa5e76

47. Hartwig S, Raguse JD, Pfitzner D, Preissner R, Paris S, Preissner S. Volatile organic compounds in the breath of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2017) 157:981–7. doi: 10.1177/0194599817711411

48. Nakhleh MK, Amal H, Jeries R, Broza YY, Aboud M, Gharra A, et al. Diagnosis and classification of 17 diseases from 1404 subjects via pattern analysis of exhaled molecules. ACS Nano. (2017) 11:112–25. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b04930

49. van De Goor RM, Leunis N, van Hooren MR, Francisca E, Masclee A, Kremer B, et al. Feasibility of electronic nose technology for discriminating between head and neck, bladder, and colon carcinomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2017) 274:1053–60. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4320-y

50. Opitz P, Herbarth O. The volatilome - investigation of volatile organic metabolites (VOM) as potential tumor markers in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2018) 47:42. doi: 10.1186/s40463-018-0288-5

51. Taware R, Taunk K, Pereira JAM, Shirolkar A, Soneji D, Camara JS, et al. Volatilomic insight of head and neck cancer via the effects observed on saliva metabolites. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:17725. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35854-x

52. Chandran D, Ooi EH, Watson DI, Kholmurodova F, Jaenisch S, Yazbeck R. The use of selected ion flow tube-mass spectrometry technology to identify breath volatile organic compounds for the detection of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Medicina . (2019) 55:306. doi: 10.3390/medicina55060306

53. Shigeyama H, Wang T, Ichinose M, Ansai T, Lee SW. Identification of volatile metabolites in human saliva from patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma via zeolite-based thin-film microextraction coupled with GC-MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. (2019) 1104:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2018.11.002

54. van de Goor RMGE, Hardy JCA, van Hooren MRA, Kremer B, Kross KW. Detecting recurrent head and neck cancer using electronic nose technology: a feasibility study. Head Neck. (2019) 41:2983–90. doi: 10.1002/hed.25787

55. Lee WH, Chen HM, Yang SF, Liang C, Peng CY, Lin FM, et al. Bacterial alterations in salivary microbiota and their association in oral cancer. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:16540. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16418-x

56. Zhao H, Chu M, Huang Z, Yang X, Ran S, Hu B, et al. Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:11773. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11779-9

57. Guerrero-Preston R, Godoy-Vitorino F, Jedlicka A, Rodriguez-Hilario A, Gonzalez H, Bondy J, et al. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:51320–34. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9710

58. Yost S, Stashenko P, Choi Y, Kukuruzinska M, Genco CA, Salama A, et al. Increased virulence of the oral microbiome in oral squamous cell carcinoma revealed by metatranscriptome analyses. Int J Oral Sci. (2018) 10:32. doi: 10.1038/s41368-018-0037-7

59. Schmidt B, Kuczynski J, Bhattacharya A, Huey B, Corby P, Queiroz E, et al. Changes in abundance of oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e98741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098741

60. Lim Y, Fukuma N, Totsika M, Kenny L, Morrison M, Punyadeera C. The performance of an oral microbiome biomarker panel in predicting oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2018) 8:267. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00267

61. Wang H, Funchain P, Bebek G, Altemus J, Zhang H, Niazi F, et al. Microbiomic differences in tumor and paired-normal tissue in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Genome Med. (2017) 9:14. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0405-5

62. Shin JM, Luo T, Kamarajan P, Fenno JC, Rickard AH, Kapila YL. Microbial communities associated with primary and metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma - a high fusobacterial and low Streptococcal signature. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:9934. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09786-x

63. Wang L, Yin G, Guo Y, Zhao Y, Zhao M, Lai Y, et al. Variations in oral microbiota composition are associated with a risk of throat cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2019) 9:205. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00205

64. Gong H, Shi Y, Zhou L, Wu C, Cao P, Tao L, et al. The composition of microbiome in larynx and the throat biodiversity between laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients and control population. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e66476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066476

65. Gu J, Zhu J, Qiu Q, Wang Y, Bai T, Yin Y. Prediction of immunohistochemistry of suspected thyroid nodules by use of machine learning-based radiomics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2019) 213:1348–57. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21626

66. Liang J, Huang X, Hu H, Liu Y, Zhou Q, Cao Q, et al. Predicting malignancy in thyroid nodules: radiomics score versus 2017 American college of radiology thyroid imaging, reporting and data system. Thyroid. (2018) 28:1024–33. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0525

67. Parmar C, Leijenaar RT, Grossmann P, Rios Velazquez E, Bussink J, Rietveld D, et al. Radiomic feature clusters and prognostic signatures specific for Lung and Head and Neck cancer. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:11044. doi: 10.1038/srep11044

68. Ren J, Tian J, Yuan Y, Dong D, Li X, Shi Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging based radiomics signature for the preoperative discrimination of stage I-II and III-IV head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. (2018) 106:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.07.002

69. Baldane S, Ipekci SH, Sozen M, Kebapcilar L. Mean platelet volume could be a possible biomarker for papillary thyroid carcinomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2015) 16:2671–4. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.7.2671

70. Seema S, Krishnan M, Harith AK, Sahai K, Iyer SR, Arora V, et al. Laser ionization mass spectrometry in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. (2014) 43:471–83. doi: 10.1111/jop.12117

71. Baizig NM, Morand P, Seigneurin JM, Boussen H, Fourati A, Gritli S, et al. Complementary determination of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load and serum markers for nasopharyngeal carcinoma screening and early detection in individuals at risk in Tunisia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2012) 269:1005–11. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1717-5

72. Heawchaiyaphum C, Pientong C, Phusingha P, Vatanasapt P, Promthet S, Daduang J, et al. Peroxiredoxin-2 and zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein as potentially combined novel salivary biomarkers for early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma using proteomic approaches. J Proteomics. (2018) 173:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.11.022

73. Kreimer AR, Shiels MS, Fakhry C, Johansson M, Pawlita M, Brennan P, et al. Screening for human papillomavirus-driven oropharyngeal cancer: considerations for feasibility and strategies for research. Cancer. (2018) 124:1859–66. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31256

74. Wang Y, Chen M, Tao Z, Hua Q, Chen S, Xiao B. Identification of predictive biomarkers for early diagnosis of larynx carcinoma based on microRNA expression data. Cancer Genet. (2013) 206:340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2013.09.005

75. Zaidi AH, Gopalakrishnan V, Kasi PM, Zeng X, Malhotra U, Balasubramanian J, et al. Evaluation of a 4-protein serum biomarker panel-biglycan, annexin-A6, myeloperoxidase, and protein S100-A9 (B-AMP)-for the detection of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. (2014) 120:3902–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28963

76. Tan HT, Low J, Lim SG, Chung MC. Serum autoantibodies as biomarkers for early cancer detection. FEBS J. (2009) 276:6880–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07396.x

77. Kiyamova R, Garifulin O, Gryshkova V, Kostianets O, Shyian M, Gout I, et al. Preliminary study of thyroid and colon cancers-associated antigens and their cognate autoantibodies as potential cancer biomarkers. Biomarkers. (2012) 17:362–71. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.677476

78. Brusselmans L, Arnouts L, Millevert C, vandersnickt J, van Meerbeeck JP, Lamote K. Breath analysis as a diagnostic and screening tool for malignant pleural mesothelioma: a systematic review. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2018) 7:520–36. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.04.09

79. Marzorati D, Mainardi L, Sedda G, Gasparri R, Spaggiari L, Cerveri P. A review of exhaled breath key role in lung cancer diagnosis. J Breath Res . (2019) 13:034001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/ab0684

80. Bax C, Lotesoriere BJ, Sironi S, Capelli L. Review and comparison of cancer biomarker trends in urine as a basis for new diagnostic pathways. Cancers. (2019) 11:1244. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091244

81. Phillips M, Cataneo RN, Cruz-Ramos JA, Huston J, Ornelas O, Pappas N, et al. Prediction of breast cancer risk with volatile biomarkers in breath. Breast Cancer Res Treat . (2018) 170:343–50. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4764-4

82. Lima AR, Pinto J, Azevedo AI, Barros-Silva D, Jeronimo C, Henrique R, et al. Identification of a biomarker panel for improvement of prostate cancer diagnosis by volatile metabolic profiling of urine. Br J Cancer. (2019) 121:857–68. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0585-4

83. Lamote K, Vynck M, Thas O, van Cleemput J, Nackaerts K, van Meerbeeck JP. Exhaled breath to screen for malignant pleural mesothelioma: a validation study. Eur Respir J. (2017) 50:1700919. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00919-2017

84. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. (2011) 144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

85. Feinberg T, Herbig J, Kohl I, Las G, Cancilla JC, Torrecilla JS, et al. Cancer metabolism: the volatile signature of glycolysis- in vitro model in lung cancer cells. J Breath Res. (2017) 11:016008. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa51d6

86. Haick H, Broza YY, Mochalski P, Ruzsanyi V, Amann A. Assessment, origin, and implementation of breath volatile cancer markers. Chem Soc Rev. (2014) 43:1423–49. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60329F

87. Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, De Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:749–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141

88. Yip SS, Aerts HJ. Applications and limitations of radiomics. Phys Med Biol. (2016) 61:R150–66. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/13/R150

89. Huang C, Cintra M, Brennan K, Zhou M, Colevas AD, Fischbein N, et al. Development and validation of radiomic signatures of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma molecular features and subtypes. EBioMedicine. (2019) 45:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.06.034

90. Chen L, Zhou Z, Sher D, Zhang Q, Shah J, Pham NL, et al. Combining many-objective radiomics and 3D convolutional neural network through evidential reasoning to predict lymph node metastasis in head and neck cancer. Phys Med Biol. (2019) 64:075011. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab083a

91. Ulrich EJ, Menda Y, Boles Ponto LL, Anderson CM, Smith BJ, Sunderland JJ, et al. FLT PET radiomics for response prediction to chemoradiation therapy in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Tomography. (2019) 5:161–9. doi: 10.18383/j.tom.2018.00038

92. Liu T, Zhou S, Yu J, Guo Y, Wang Y, Zhou J, et al. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a radiomics method based on preoperative ultrasound images. Technol Cancer Res Treat. (2019) 18:1533033819831713. doi: 10.1177/1533033819831713

93. Ou D, Blanchard P, Rosellini S, Levy A, Nguyen F, Leijenaar RTH, et al. Predictive and prognostic value of CT based radiomics signature in locally advanced head and neck cancers patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy or bioradiotherapy and its added value to Human Papillomavirus status. Oral Oncol. (2017) 71:150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.06.015

94. Cozzi L, Franzese C, Fogliata A, Franceschini D, Navarria P, Tomatis S, et al. Predicting survival and local control after radiochemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer by means of computed tomography based radiomics. Strahlenther Onkol. (2019) 195:805–18. doi: 10.1007/s00066-019-01483-0

95. Yuan Y, Ren J, Shi Y, Tao X. MRI-based radiomic signature as predictive marker for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. (2019) 117:193–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.06.019

96. Ger RB, Zhou S, Elgohari B, Elhalawani H, Mackin DM, Meier JG, et al. Radiomics features of the primary tumor fail to improve prediction of overall survival in large cohorts of CT- and PET-imaged head and neck cancer patients. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0222509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222509

97. Bogowicz M, Leijenaar RTH, Tanadini-Lang S, Riesterer O, Pruschy M, Studer G, et al. Post-radiochemotherapy PET radiomics in head and neck cancer - the influence of radiomics implementation on the reproducibility of local control tumor models. Radiother Oncol. (2017) 125:385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.10.023

98. M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Head and Neck Quantitative Imaging Working Group. Investigation of radiomic signatures for local recurrence using primary tumor texture analysis in oropharyngeal head and neck cancer patients. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:1524. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14687-0

99. Bahig H, Lapointe A, Bedwani S, De Guise J, Lambert L, Filion E, et al. Dual-energy computed tomography for prediction of loco-regional recurrence after radiotherapy in larynx and hypopharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Radiol. (2019) 110:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.11.005

100. Leijenaar RT, Bogowicz M, Jochems A, Hoebers FJ, Wesseling FW, Huang SH, et al. Development and validation of a radiomic signature to predict HPV (p16) status from standard CT imaging: a multicenter study. Br J Radiol. (2018) 91:20170498. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170498

101. Bogowicz M, Riesterer O, Ikenberg K, Stieb S, Moch H, Studer G, et al. Computed tomography radiomics predicts HPV status and local tumor control after definitive radiochemotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2017) 99:921–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.002

102. Beichel RR, Smith BJ, Bauer C, Ulrich EJ, Ahmadvand P, Budzevich MM, et al. Multi-site quality and variability analysis of 3D FDG PET segmentations based on phantom and clinical image data. Med Phys. (2017) 44:479–96. doi: 10.1002/mp.12041

103. Bagher-Ebadian H, Siddiqui F, Liu C, Movsas B, Chetty IJ. On the impact of smoothing and noise on robustness of CT and CBCT radiomics features for patients with head and neck cancers. Med Phys. (2017) 44:1755–70. doi: 10.1002/mp.12188

104. Mishra R. Biomarkers of oral premalignant epithelial lesions for clinical application. Oral Oncol. (2012) 48:578–84. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.01.017

Keywords: head and neck neoplasms, biomarker, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, volatomics, microbiomics, radiomics

Citation: Konings H, Stappers S, Geens M, De Winter BY, Lamote K, van Meerbeeck JP, Specenier P, Vanderveken OM and Ledeganck KJ (2020) A Literature Review of the Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers of Head and Neck Neoplasms. Front. Oncol. 10:1020. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01020

Received: 02 February 2020; Accepted: 22 May 2020; Published: 26 June 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Konings, Stappers, Geens, De Winter, Lamote, van Meerbeeck, Specenier, Vanderveken and Ledeganck. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kristien J. Ledeganck, kristien.ledeganck@uantwerp.be

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole