Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Thinking Historically

Historians are about a lot more than impressing readers with cool facts about the past. To know the import of those facts, and to put them into a coherent story, they must develop essential skills in critical thinking and organization. In simple terms, they sift through a great deal of raw data, evaluate it, and create lucid reports for others to read. In history terms, our data are primary sources, our evaluation method rests on assessing the influence of various elements of the specific context, and our “reports” can be anything from research papers to books on a single topic, called monographs, to digital and media artifacts.

While it is the point of this chapter to expand on the above sentence, you should read it resting in the knowledge that learning to succeed as a history student will provide you with many of the same skills needed for professional success. As do those in any number of professions including law, business, and teaching, historians frequently begin with data that can be both extensive in quantity and contradictory in quality, and so must determine what is most important; they have to resolve contradictions and ultimately tell a coherent story, one that their audiences find compelling and meaningful. In essence, history requires essential critical thinking skills, including judgment, synthesis, and creativity.

As is often the case, the best way to begin to develop higher-order thinking skills is break them down into manageable chunks and practice putting them into action. This chapter starts by defining the term history and explaining a bit about how the discipline of history is structured. As scholars, historians must build on the knowledge of others, rather than pursuing stories and information for its own sake. They participate in the academic project—a phrase often used to capture what scholars do when they consider how new knowledge relates to current understandings. The nature of historical thinking—evaluating and ranking types of evidence, figuring out how to weave together fragments of meaning, knowing when to recognize historical fallacies and other sloppy thinking patterns—forms the core of the chapter. Once you’ve oriented yourself toward some of the main ideas behind historical thinking, you’ll be ready to move onto the next section—Reading Historically—which focuses on perhaps the most essential skill historians (and history students) possess, that is, how to read all sorts of documents critically.

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline Copyright © 2022 by Stephanie Cole; Kimberly Breuer; Scott W. Palmer; and Brandon Blakeslee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

You are using an outdated browser. This website is best viewed in IE 9 and above. You may continue using the site in this browser. However, the site may not display properly and some features may not be supported. For a better experience using this site, we recommend upgrading your version of Internet Explorer or using another browser to view this website.

- Download the latest Internet Explorer - No thanks (close this window)

- Penn GSE Environmental Justice Statement

- Philadelphia Impact

- Global Initiatives

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Catalyst @ Penn GSE

- Penn GSE Leadership

- Program Finder

- Academic Divisions & Programs

- Professional Development & Continuing Education

- Teacher Programs & Certifications

- Undergraduates

- Dual and Joint Degrees

- Faculty Directory

- Research Centers, Projects & Initiatives

- Lectures & Colloquia

- Books & Publications

- Academic Journals

- Application Requirements & Deadlines

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Campus Visits & Events

- International Students

- Options for Undergraduates

- Non-Degree Studies

- Contact Admissions / Request Information

- Life at Penn GSE

- Penn GSE Career Paths

- Living in Philadelphia

- DE&I Resources for Students

- Student Organizations

- Career & Professional Development

- News Archive

- Events Calendar

- The Educator's Playbook

- Find an Expert

- Race, Equity & Inclusion

- Counseling & Psychology

- Education Innovation & Entrepreneurship

- Education Policy & Analysis

- Higher Education

- Language, Literacy & Culture

- Teaching & Learning

- Support Penn GSE

- Contact Development & Alumni Relations

- Find a Program

- Request Info

- Make a Gift

- Current Students

- Staff & Faculty

Search form

You are here, teaching students to think like historians.

History class should not simply be a space where students learn through rote memorization. Abby Reisman offers tips on how educators should frame class sessions to develop students' critical thinking skills instead.

History class should be a space where students learn to think and reason, not just memorize. We want students to be able to answer not only “What happened?” but “How do you know?” and “Why do you believe your interpretation is valid?” Such questions align with the Common Core State Standards, which specify that college-ready students be able identify an author’s perspective, develop claims, and cite evidence to support their analyses. Penn GSE Professor Abby Reisman helped develop the award-winning Reading Like a Historian curriculum, which develops students’ critical thinking skills. Here are her tips for history class: [1] Use texts as evidence. Shifting through multiple interpretations of an event is neither natural nor automatic. Few students recognize that every historical narrative is also an argument or an interpretation from its author. Students can learn to weigh and evaluate competing truth claims, consider the author’s motive and purpose, and draw inferences about the broader social and political context. These are especially important skills in a world where information, both useful and bogus, is a mouse click away. [2] Develop historical reading skills . Train students in the four key strategies historians use to analyze documents: sourcing, corroboration, close reading, and contextualization. With these skills, students can read, evaluate, and interpret historical documents in order to determine what happened in the past. [3] Demonstrate through modeling. Students greatly benefit from seeing their teacher think aloud while reading a historical document first. A teacher should work through the text, evaluating the author’s reliability, and raising broader questions about the event in question. Eventually, students will be ready to try it on their own and in small groups. [4] Build a document-based lesson. Reading Like a Historian lesson plans generally include four elements:

- Introduce students to background information so they are familiar with the period, events, and issues under investigation.

- Provide a central historical question that focuses students’ attention. This transforms the act of reading into a process of creative inquiry. The best questions are open to multiple interpretations, and direct students to the historical record rather than their philosophical or moral beliefs. Most importantly, students must be able to answer this question from evidence in the document.

- Have students read multiple documents that offer different perspectives or interpretations of the central historical question. These documents should represent different genres. For example, a diary entry from a participant of an event might be examined alongside a contemporary news account.

- Have the students respond to the central historical question in writing, a classroom discussion, or both. Make sure they formulate a historical claim or argument and support it with evidence from the text.

[5] Engage in whole-class discussion. Text-based discussions allow students to develop a deeper understanding of the subject and internalize higher-level thinking and reasoning. In effective text-based discussions, students articulate their shifting claims, reexamine the available evidence, and interrogate their classmates’ reasoning.

You May Be Interested In

Related topics.

Faculty Expert

Associate Professor

Related News

Media inquiries.

Penn GSE Communications is here to help reporters connect with the education experts they need.

Kat Stein Executive Director of Penn GSE Communications (215) 898-9642 [email protected]

Get tips for today's teaching challenges from Penn GSE experts.

Critical Thinking Questions

Could the differences between the North and South have been worked out in late 1860 and 1861? Could war have been avoided? Provide evidence to support your answer.

Why did the North prevail in the Civil War? What might have turned the tide of the war against the North?

If you were in charge of the Confederate war effort, what strategy or strategies would you have pursued? Conversely, if you had to devise the Union strategy, what would you propose? How does your answer depend on your knowledge of how the war actually played out?

What do you believe to be the enduring qualities of the Gettysburg Address? Why has this two-minute speech so endured?

What role did women and African Americans play in the war?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Sylvie Waskiewicz, Paul Vickery

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: U.S. History

- Publication date: Dec 30, 2014

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/15-critical-thinking-questions

© Jan 11, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

The Historical Thinking Project was designed to foster a new approach to history education — with the potential to shift how teachers teach and how students learn, in line with recent international research on history learning. It revolves around the proposition that historical thinking — like scientific thinking in science instruction and mathematical thinking in math instruction — is central to history instruction and that students should become more competent as historical thinkers as they progress through their schooling.

The project developed a framework of six historical thinking concepts to provide a way of communicating complex ideas to a broad and varied audience of potential users.

Active from 2006 to 2014, the Historical Thinking Project provided social studies departments, local boards, provincial ministries of education, publishers and public history agencies with models of more meaningful history teaching, assessment, and learning for their students and audiences. As the 2014 Annual Report demonstrates, they met a very receptive audience.

From April 2014 onward, it will operate on "pilot light" mode, in the event that new teams of educators are ready to start cooking .

Summer Institute 2016

The Summer Institute is designed for teachers, graduate students, curriculum developers, professional development leaders and museum educators who want to enhance their expertise at designing and teaching history courses and programs with explicit attention to historical thinking.

Vancouver, BC 11-16 July 2016 More information here.

© Centre for the Study of Historical Consciousness

- Student LMS

- “The Beacon” Student Newspaper

- Merchandise

Current Coupon Codes

Using History to Teach Critical Thinking Skills

Feb 26, 2019

One of the most important tools we can give our students is the ability to think critically. In this age of unlimited social media sharing, fake news, and hidden agendas, it has never been more important to be able to look at information and its source and determine if the information is accurate and true. Dictionary.com defines critical thinking as clear, rational, open-minded, and informed by evidence. In a good history class, one that moves beyond the textbook, thinking critically is part of the package.

Students of history look at an event from many different perspectives. The use of both primary (first-hand accounts) and secondary (recounting with interpretation and analysis) sources helps students see an event from many different angles. Imagine an event like the Boston Massacre. The account of the British soldier involved would be very different from the patriot on the street. Likewise, Paul Revere, Thomas Jefferson, and King George III would all see the Boston Massacre from a different place. A twenty-first century historian would add another view of the event. A British historian and an American historian would likely see the event in two different lights. A student of history learns to read all the accounts and make judgments about the event. Were the patriots justified in their actions? Were the soldiers? Why did Paul Revere refer to the event as a massacre? How did the event contribute to the tensions between the colonies and the crown leading up to the American Revolution?

Looking at different sources, the perspective of the author, and the bias brought to the event help students learn to discern and think critically. This important skill can be extrapolated to their non-academic life to determine if a news article, tweet, or report is valid or bait.

Becky Frank has been steeped in American History from her early days growing up on the family farm in Northeastern North Carolina. Although Barrow Creek Farm has been in her family since the 1680s, her parents were the first to live on it in three generations. On the farm she learned to milk cows, sheer sheep, and drive a tractor.

After an internship at Historic Edenton, she received a B.S. in Public History from Appalachian State University in 1992. Answering God’s call to teach in a classroom setting, she added teacher certification from East Carolina University to her degree in 1998. Becky then taught social studies in Gates County, North Carolina where her classes included U.S. History, World History, Economics, Government, and Humanities. In 2003 she married her husband John and left the classroom to start a family.

Becky has been teaching online for more than 10 years. She also homeschools her three children and is an active leader in the Children’s and Youth’s ministry at her church. She also enjoys gardening, cooking, scrapbooking and long walks with her kids and the family dog. Sharing the heritage of our great country is one of her passions as well. Her lifelong dream is to return to the family farm and make a portion of the acreage a living history site.

Parents must first create a family membership account in order to purchase classes.

Parents should purchase classes for one student at a time in the shopping cart. This will allow the registrar to appropriately place your students in the correct classes.

See How to Register for more details.

Exploring History: Engaging Lesson Plans and Resources for Teachers

Welcome to our website, where we dive into the captivating world of history education. Whether you’re a seasoned educator or a passionate homeschooling parent, we’ve curated a collection of engaging lesson plans and resources to make your history teaching journey both exciting and informative. Join us as we explore a variety of historical topics, from ancient civilizations to modern events, while incorporating interactive activities and primary source documents that bring history to life.

- History Lesson Plans: Unveiling the Past: Our history lesson plans cater to different age groups and cover a wide range of topics, ensuring that you can find the perfect resources for your classroom. From exploring ancient civilizations like Egypt, Rome, and Greece to understanding the causes and consequences of World War I and II, our comprehensive lesson plans provide a solid foundation for historical learning.

- Social Studies Resources: Cultivating Global Citizens: Social studies is an integral part of history education, fostering an understanding of cultures, geography, and citizenship. Our social studies resources complement history lessons by integrating geography into historical narratives, helping students grasp the significance of locations and how they shaped historical events. Additionally, we offer activities that promote global citizenship and encourage students to explore the diverse perspectives that have shaped our world.

- Primary Source Documents: Hearing Voices from the Past: One of the most effective ways to connect students with history is through primary source documents. We believe in bringing historical figures and events to life by allowing students to engage directly with the voices of the past. Our curated collection of primary source documents, including letters, speeches, photographs, and diary entries, provides valuable insights into different historical periods, fostering critical thinking and historical analysis skills.

- Interactive History Lessons: Learning Through Engagement: Gone are the days of dry and passive history lessons. Our interactive history lessons encourage active participation and engagement, making learning a fun and immersive experience. Whether it’s organizing mock debates on historical controversies or creating hands-on projects that recreate historical artifacts, our resources ensure that students become active participants in their own learning journey.

- Black History Month Activities: Celebrating Diversity and Contributions: Black history is an essential part of our collective narrative, and we provide a range of activities to celebrate and honor the contributions of Black individuals throughout history. From biographies of influential figures to lessons on the Civil Rights Movement, our resources offer opportunities for students to explore the rich tapestry of Black history and its significance in shaping society.

As educators, it’s our responsibility to ignite a passion for history in our students. Our blog is dedicated to providing you with the tools and resources necessary to create engaging and meaningful history lessons. By incorporating our carefully curated lesson plans, social studies resources, primary source documents, and interactive activities, you’ll inspire your students to become critical thinkers, empathetic global citizens, and lifelong lovers of history. Join us on this exciting journey of exploration and discovery as we unlock the doors to the past and bring history alive in your classroom.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Why use the VH?

- Log in / Register

- What's New

- Publications

The Virtual Historian

Promoting historical thinking and critical literacy through historical challenges.

What is historical literacy? Why is it important? Read this short article (from S. Lévesque, Canadian issues , winter 2010).

Learning history is far more engaging than memorizing dates!...

The VH 2.0 was designed to engage students in their own learning of history, to assist them in developing historical thinking competencies. It proposes an innovative approach for the transfer of learning and the application of knowledge through inquiry-based activities known as "historical challenges".

To know more about "historical thinking and why it matters" watch this short video from expert Sam Wineburg.

The VH 2.0 situates learning in an active and practical context. All historical challenges are designed to promote inquiry skills, h istorical knowledge acquisition and the development of critical thinking and literacy skills. To assist students in their strategic and analytical practices, the VH 2.0 offers various learning tools and scaffolds including worksheets, lexicons, and interactive learning guides.

For each lesson activity, practical activities engage students in high cognitive challenges. These challenges build on a series of intellectual processes and key concepts well recognized in history education.

Among these processes used in the VH 2.0 are**:

- - Adopting an inquisitive and open-minded attitude toward the past and different ways of life

- - Establishing the historical significance of the past

- - Using primary and secondary source evidence to infer knowledge

- - Identifying continuity and change in history

- - Analyzing the causes and consequences of actions and events in history

- - Taking historical perspectives and developing historical empathy

- - Understanding the ethical dimension of history

- - Developing critical literacy skills

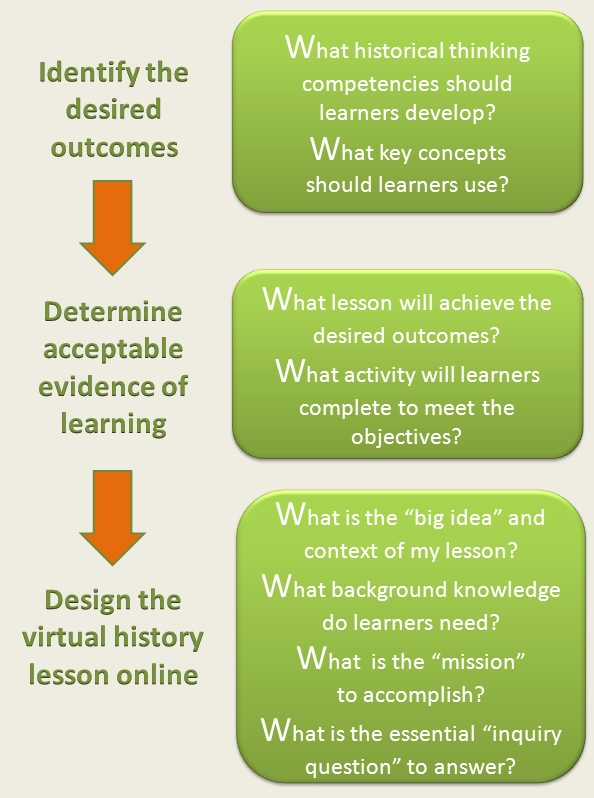

Research indicates that learners will not develop indepth understanding and disciplinary competencies when lessons and activities do not provide them with explicit performance goals and tasks . The VH 2.0 follows a conceptual structure of backward design derived from the work of Wiggins and McTighes (2005).

It operates on the following model:

*Adaptation of Wiggins, G., and McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design, 2nd Edition . Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Privacy Policy

- What teachers said

- Our Mission

Building Critical Thinkers by Combining STEM With History

By asking students to explore the history of scientific discoveries, we get them to view their world with more wonder—and more skepticism—and condition their minds to think about causes and effects.

For many science teachers, the night before a lesson is often filled with anxiety as they look for ways to make the next day’s class more engaging. But the tools that teachers have access to are not all the same.

Some teachers have maker spaces fitted with 3D printers; some do not. Some teachers have a strong science background, while others do not. Some schools have supply rooms stocked with Erlenmeyer flasks and high-powered microscopes, but many more do not. All students need to become critical thinkers, which great STEM instruction can foster. But the development of critical thinking does not hinge solely on a fancy maker space, a prestigious science degree, or an abundance of resources.

One innovative way to foster critical thinking in STEM is to add a bit of history. STEM was born from the desire to emulate how life actually operates by merging four core disciplines: science, technology, engineering, and math. In the real world, these disciplines often work together seamlessly, and with little fanfare.

But if we want to prepare children to be future scientists, we need to inform them about the past. By doing so, we demystify scientific advancements by revealing their messy historical reality; we show students how science is actually conducted; and we have the opportunity to spotlight scientists who have been written out of history—and thus invite more students into the world of science.

The Power of Science Stories

One of the best ways to share science from a historical point of view is to tell great science stories. Stories are sticky: The research shows that humans are hardwired for them, and that scaffolding information—by bundling scientific discoveries with a compelling narrative, for example—helps the brain incorporate new concepts. In this way, stories act like conveyor belts, making lessons more exciting and carrying crucial information along with them.

But good stories can serve another purpose, too. By seeing how an invention of the past impacts life in the present, students learn to think holistically. For example, if they are shown how clocks accelerated life, or how computers changed how humans think, then they can see how technology shapes culture or even changes our sense of time. In this way, STEM expands beyond its typical limits and becomes interconnected in students’ minds—not just to other technologies, but to all disciplines and fields of inquiry.

Uncovering the Unintended Consequences of Inventions

For over a decade, I looked for a book to provide both the historical and societal context of inventions—to tell the stories of science—but didn’t have much luck. I felt so strongly about this missing approach to nurture critical thinkers that I decided to write The Alchemy of Us , which is a book about inventions and how they changed life and society. In it, the lives of a diverse cast of little-known inventors—from pastor Hannibal Goodwin to housewife Bessie Littleton—are unfolded, and the many ways in which those everyday inventions changed life are highlighted.

Sometimes the outcomes of these inventions were intended, and in many more cases they were not. For example, students will see that the telegraph used electricity to shuttle messages over long distances quickly. But they will also come to realize that the telegraph had a shortcoming: It could not handle many messages at a time. Customers at the telegraph office were encouraged to keep their messages brief. Soon, newspapers used telegraphs in their newsrooms, and editors told reporters to write succinctly. The use of short declarative sentences was a newspaper style that was embraced by one reporter who went on to write many famous books—his name was Ernest Hemingway.

Here, then, is a case of how a technology, the telegraph, altered language and led to one of the world’s most celebrated literary styles—and this lesson of cascading and unpredictable outcomes can be extended to how Twitter and text messages are altering language now. When history is included in STEM, students learn science, but they also learn about the much broader impact of science.

Shaping the Future by Using the Past: An Exercise

One way that we can build critical thinking skills is to put technology under the microscope. Have students think about inventions, like their cell phones or Instagram or the internet, and consider how they make an impact on life more broadly. Students can create lists of all the changes—ask them to think about not only changes to the material world, but changes to less tangible ideas and concepts, like human psychology and belief systems—and break students into small groups to discuss and share out their findings. Alternatively, you can pose a counterfactual: Ask students to create a timeline of the invention’s history, along with a second timeline as if that invention never happened. What happens if the cell phone was never invented?

Obviously, there are no right or wrong answers, but the tasks require your students to observe the world with more wonder—and more skepticism—and condition their minds to think about causes and effects.

To take a deeper look: Let’s say you asked your students to examine the effect of the internet on modern life. The internet has certainly changed life significantly. For starters, we can listen to music, watch videos, access information, and contact each other easily. Have your students discuss life before and after the internet in groups and then create a drawing or write a short essay. They could answer questions like these: How did people get their news? How did they hear from each other? How did people listen to music? Where was information about different topics stored before the internet? The next step might be to look at the pros and cons of the internet, specifically social media. Does being more connected help or hurt us? Does the internet bring us together or divide us? Does the internet make it easier or harder to find the truth?

Once students are warmed up to thinking about technology in this way, you might have them try on the role of futurists. Ask them to consider thought-provoking questions like: If social media is based on “likes” and “follows,” what kind of society will we be in the future? Will we listen to popular celebrities with millions of followers, or will we listen to experts with fewer followers? Will it be easier to spread false information? Students can then draw a picture, write an essay, or create a video reflecting on the societal impact of the internet and what life could be like in the future with or without their proposed solutions.

Engaging Future Citizens

While STEM skills are themselves increasingly important in our technologically rich world, STEM is also a pathway to engage students as critical thinkers, and even as future citizens. By placing science in the broader context of history and culture, we can remind students of how scientific inventions play a role in our evolving cultural and even moral belief systems. And by giving students the space to critique inventions, we give them the skills to shape the future.

To get kids asking hard questions, however, the key first step is to give them good science stories. Once students are more engaged with how STEM is part of a larger fabric, they will have the skills to see the world more clearly and the lens they need to start posing tough questions. This approach aligns with the wisdom of William Shakespeare, who said centuries ago, “What’s past is prologue.” He was absolutely right, because if we’re attentive observers, the old stories provide us with a good map to what lies ahead.

Ainissa Ramirez is a materials scientist and the author of “ The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another (MIT Press).

- US History Prediction Bellworks!

- 9 Presidential Decisions Activities BUNDLE! Washington to Lincoln!

- Full US History I Video Curriculum

- Colonial America

- Revolutionary America

- A More Perfect Union

- The Age of Jackson

- Westward Expansion 1800-1850

- Civil War Unit

- Civil War Spies

- Holiday Lessons

- US History II Bellworks

- Full Year Bundle

- Unit 1 Gilded Age

- Unit 2 Progressive Era

- Unit 3 American Imperialism

- Unit 4 World War I

- Unit 5 The Roaring 1920s

- Unit 6 Great Depression and New Deal

- Unit 7 America in World War II

- Unit 8 The Cold War

- Unit 9 The Civil Rights Movement

- AP US History WORKBOOKS

- AP US HISTORY DBQ SHEETS

- APUSH DBQ Review Bootcamp!

- APUSH LEQ Review Bootcamp!

- APUSH Exam MEGA Review Activities

- Online Courses

- Presidential Decisions Activities

- AP Human Geography Workbooks

- Start of the School Year Lessons

- Activity Templates & Graphic Organizers

- Random Engaging Lessons

- Shirts and Swag

Fun Ways to Teach Historical Thinking Skills

6 activities & strategies that engage & build skills .

History class must be more than just studying events and figures from the past and memorizing dates- and thank gosh for that! Really exploring history and engaging students in history classes means that they genuinely explore the past and investigate, wrestle, and face the lessons of history in meaningful ways. This demands that students develop historical thinking skills.

Luckily, it can be incredibly engaging to do so. However, it can also be daunting to develop those higher order thinking skills! This can be especially challenging if you teach in an inclusion class with mixed ability learners who really struggle with critical thinking skills. These are some fun activities I have used to teach historical thinking skills and build them during the year. I hope they help!

SKILL: Historical Interpretation & Synthesis

Historical Interpretation means that students can combine various sources and evidence to develop insight into the past and make original connections to it. It can be one of the most challenging to teach, but also the most fun!

ACTIVITY 1: Scavenger Hunt

This can be done at the end of pretty much any unit. I recently did it for a Progressive Era unit. Students did a “Progressive Era Legacy Scavenger Hunt” around campus and had to take 3 pictures of things that could be seen as having a clear connection to the progressive era. Students made a quick powerpoint presentation and had to explain the connection. Some connections were quite a stretch- like the school garden being a legacy of Roosevelt’s conservation, but it helped them look at the present with a critical eye towards the past and its impact and develop some synthesis skills!

SKILL: Comparison

Comparison is a skill that students develop in most of their classes but is essential for understanding history, recognizing trends, and analyzing figures, periods, and events. But to make it more meaningful to history- make sure to pull the story and personalities out of the comparison!

ACTIVITY 2: Dinner Party

This is a fun one that seems light and easy to pull students in but will get them to really think critically about differences between historical figures and their ideas. With a simple image of a table with four to six seats on each side of the table, have students create seating arrangements based on which people would work and get along best together and who would likely get into fierce arguments and should sit far apart. After studying any unit with multiple figures like the Renaissance, Antebellum Era, the Civil Rights Movement, or Ancient Civilizations, give students a list of people they have studied and have them make their arrangements and justify their choices. This goes so much beyond a venn-diagram while still being a relatively simple activity to create and complete that is still fun and rigorous!

SKILL: Chronological Reasoning & Change Over Time

History is fundamentally the story and study of change and continuity over time. While memorizing dates is not essential, understanding how events build and develop over time is a fundamental historical thinking skill.

ACTIVITY 3: Spicy Timelines

Timelines can be used all the imte in history class, but keep them interesting and spicey by mixing it up!

1) Bell Ringer Timelines:

Quick and easy- post a series of events from the unit or last class and have students make a ‘quick & dirty’ timeline.

2) Presidential Timelines:

This could also build some ‘periodization’ skills as students not only sort events in order but organize them in order but also by President. You can give students a bank of important events and have them organize and sort them or for more advanced learners, have them work from scratch.

3) Illustrated Timelines:

As easy and fun as it sounds- students draw images for the events of the timeline to foster some creativity and deeper connections.

4) POV Timelines:

This one builds another historical thinking skill- understanding point-of-view and some historical empathy as well. I did this last year for the “ Road to Pearl Harbor ” and for each event, they not only summarize it, but then there are two boxes to explain how the Japanese and Americans viewed this even differently. Two birds, one stone, and some engaging history!

BONUS : When kids really need a break and some fun- grab big chalk and do these outside on sidewalks or on the parking lot.

If you have any other awesome timeline ideas, I would love to hear them. I’m always looking to add more spicy to my timeline activities! 😉

SKILL: CAUSATION

Cause and effect are fundamental skills in the study of history and even in high school, its surprising how much students struggle with it. It took me years to realize that students actually need a lot of support in developing this skills! Here's an easy way to build this into your class any day of the year.

ACTIVITY 4 : Simple Sentence Starter

This can be used for any topic and its simple but can be powerful as well. Simply project or write this sentence frame and watch as students come up with many different effects and answers.

“If _______ never happened, than _______.” The simplicity is what makes this interesting. For the Columbian Exchange, World War II, Neolithic Revolution, or Revolutionary War, students first have to consider what did change and then have to brainstorm how things would be different without that event. I sometimes then have students share with their neighbors or in small or groups, or even more fun- have everyone stand up and they can only sit down after reading there’s. All students can share and be successful!

Activity 5: Scaffolded Cause and Effect Chart

For a given event, print out 3-4 causes and effects each one on a full size paper (its more fun that way!) and scramble them. Give them to students in groups and first have them sort them into cause and effects. (Starts simple!) Next, have students put them in order of greatest significance- what was the main cause and most important effect? (Building complexity). Lastly, have students justify their answers- “X was the most important cause because ____”. This helps diverse learners build skills one step at time without being overwhelmed and while being mostly hands on it also gets students writing and thinking critically.

SKILL: SOURCING DOCUMENTS

The shift to prioritizing primary sources has been vital in enriching our social studies classes. It really gets students wrestling with the past on its own terms! And learning how to source documents and think critically about the document itself- the elements behind the document is essential. One of the most popular ways to do this is using SOAPS- which is excellent but make sure to introduce SOAPS with a little spice!

ACTIVITY 6: Spicy SOAPS

To ensure students enjoy doing SOAPS and learn the skills involved, give students rich and accessible sources to start with.

This could be an advertisement for a Coke from the 1920s, cave paintings, a medieval knight’s armor, a receipt from a silk road merchant, or a Picasso painting, just don’t give them a long-winded convoluted text from another century! Analyzing the the Lascaux cave paintings, or a magazine ad for a coke, students will enjoy considering the S ubject, O ccasion (understanding context!), A udience and who would be influenced by it, P urpose, and identifying what we know about the S peaker (or artist). If student’s first experience with an analysis strategy like SOAPS is positive, they are much more likely to enjoy it when they are given a really challenging document next time. SOAPS could be used weekly as its a vital skill and essential to multiple historical thinking skills.

Grab my SOAPS or SCOAPS Sheets here for free!

______________________________________________________________

Hey! I created a course for history teachers like you!

Click to learn how to make history to come alive while bringing the joy back to teaching & learning!

How I use a timeline in class: In both history and math I start the school year having students create a timeline of their life (birthday through first day of this school year). 10 personal events on bottom and 10 world events on top. Showing an example of my timeline gives me an opportunity to share myself. I then get to know a bit about my students. In math I emphasize relative placement of events (9/11 is closer to 2002 than 2001) and in history it’s a good way to help students realize they are living in historical times now.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

A self-paced course to help you build a positive learning community & end power struggles for good!

A self-paced course to get even your most reluctant learners interested and engaged by making rigorous learning fun!

SHEG has a new name

The Stanford History Education Group has spun out of Stanford to become the Digital Inquiry Group. Now operating as an independent nonprofit, DIG still has the same team and resources available to you for free, as always.

Register today!

Historical thinking chart.

This chart elaborates on the historical reading skills of sourcing, corroboration, contextualization, and close reading. In addition to questions that relate to each skill, the chart includes descriptions of how students might demonstrate historical thinking and sentence frames to support the development of these skills.

[Spanish chart updated on 06/23/20.]

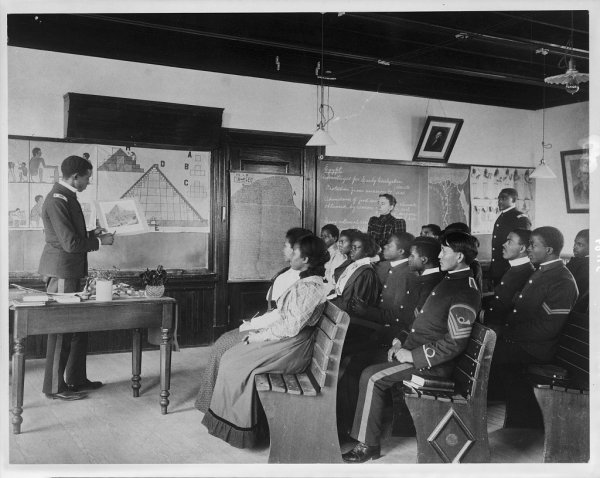

Image: Photo of African American and Native American students in Ancient History class by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1899. From the Library of Congress .

Download Materials

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

This supplement elaborates on the history of the articulation, promotion and adoption of critical thinking as an educational goal.

John Dewey (1910: 74, 82) introduced the term ‘critical thinking’ as the name of an educational goal, which he identified with a scientific attitude of mind. More commonly, he called the goal ‘reflective thought’, ‘reflective thinking’, ‘reflection’, or just ‘thought’ or ‘thinking’. He describes his book as written for two purposes. The first was to help people to appreciate the kinship of children’s native curiosity, fertile imagination and love of experimental inquiry to the scientific attitude. The second was to help people to consider how recognizing this kinship in educational practice “would make for individual happiness and the reduction of social waste” (iii). He notes that the ideas in the book obtained concreteness in the Laboratory School in Chicago.

Dewey’s ideas were put into practice by some of the schools that participated in the Eight-Year Study in the 1930s sponsored by the Progressive Education Association in the United States. For this study, 300 colleges agreed to consider for admission graduates of 30 selected secondary schools or school systems from around the country who experimented with the content and methods of teaching, even if the graduates had not completed the then-prescribed secondary school curriculum. One purpose of the study was to discover through exploration and experimentation how secondary schools in the United States could serve youth more effectively (Aikin 1942). Each experimental school was free to change the curriculum as it saw fit, but the schools agreed that teaching methods and the life of the school should conform to the idea (previously advocated by Dewey) that people develop through doing things that are meaningful to them, and that the main purpose of the secondary school was to lead young people to understand, appreciate and live the democratic way of life characteristic of the United States (Aikin 1942: 17–18). In particular, school officials believed that young people in a democracy should develop the habit of reflective thinking and skill in solving problems (Aikin 1942: 81). Students’ work in the classroom thus consisted more often of a problem to be solved than a lesson to be learned. Especially in mathematics and science, the schools made a point of giving students experience in clear, logical thinking as they solved problems. The report of one experimental school, the University School of Ohio State University, articulated this goal of improving students’ thinking:

Critical or reflective thinking originates with the sensing of a problem. It is a quality of thought operating in an effort to solve the problem and to reach a tentative conclusion which is supported by all available data. It is really a process of problem solving requiring the use of creative insight, intellectual honesty, and sound judgment. It is the basis of the method of scientific inquiry. The success of democracy depends to a large extent on the disposition and ability of citizens to think critically and reflectively about the problems which must of necessity confront them, and to improve the quality of their thinking is one of the major goals of education. (Commission on the Relation of School and College of the Progressive Education Association 1943: 745–746)

The Eight-Year Study had an evaluation staff, which developed, in consultation with the schools, tests to measure aspects of student progress that fell outside the focus of the traditional curriculum. The evaluation staff classified many of the schools’ stated objectives under the generic heading “clear thinking” or “critical thinking” (Smith, Tyler, & Evaluation Staff 1942: 35–36). To develop tests of achievement of this broad goal, they distinguished five overlapping aspects of it: ability to interpret data, abilities associated with an understanding of the nature of proof, and the abilities to apply principles of science, of social studies and of logical reasoning. The Eight-Year Study also had a college staff, directed by a committee of college administrators, whose task was to determine how well the experimental schools had prepared their graduates for college. The college staff compared the performance of 1,475 college students from the experimental schools with an equal number of graduates from conventional schools, matched in pairs by sex, age, race, scholastic aptitude scores, home and community background, interests, and probable future. They concluded that, on 18 measures of student success, the graduates of the experimental schools did a somewhat better job than the comparison group. The graduates from the six most traditional of the experimental schools showed no large or consistent differences. The graduates from the six most experimental schools, on the other hand, had much greater differences in their favour. The graduates of the two most experimental schools, the college staff reported:

… surpassed their comparison groups by wide margins in academic achievement, intellectual curiosity, scientific approach to problems, and interest in contemporary affairs. The differences in their favor were even greater in general resourcefulness, in enjoyment of reading, [in] participation in the arts, in winning non-academic honors, and in all aspects of college life except possibly participation in sports and social activities. (Aikin 1942: 114)

One of these schools was a private school with students from privileged families and the other the experimental section of a public school with students from non-privileged families. The college staff reported that the graduates of the two schools were indistinguishable from each other in terms of college success.

In 1933 Dewey issued an extensively rewritten edition of his How We Think (Dewey 1910), with the sub-title “A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process”. Although the restatement retains the basic structure and content of the original book, Dewey made a number of changes. He rewrote and simplified his logical analysis of the process of reflection, made his ideas clearer and more definite, replaced the terms ‘induction’ and ‘deduction’ by the phrases ‘control of data and evidence’ and ‘control of reasoning and concepts’, added more illustrations, rearranged chapters, and revised the parts on teaching to reflect changes in schools since 1910. In particular, he objected to one-sided practices of some “experimental” and “progressive” schools that allowed children freedom but gave them no guidance, citing as objectionable practices novelty and variety for their own sake, experiences and activities with real materials but of no educational significance, treating random and disconnected activity as if it were an experiment, failure to summarize net accomplishment at the end of an inquiry, non-educative projects, and treatment of the teacher as a negligible factor rather than as “the intellectual leader of a social group” (Dewey 1933: 273). Without explaining his reasons, Dewey eliminated the previous edition’s uses of the words ‘critical’ and ‘uncritical’, thus settling firmly on ‘reflection’ or ‘reflective thinking’ as the preferred term for his subject-matter. In the revised edition, the word ‘critical’ occurs only once, where Dewey writes that “a person may not be sufficiently critical about the ideas that occur to him” (1933: 16, italics in original); being critical is thus a component of reflection, not the whole of it. In contrast, the Eight-Year Study by the Progressive Education Association treated ‘critical thinking’ and ‘reflective thinking’ as synonyms.

In the same period, Dewey collaborated on a history of the Laboratory School in Chicago with two former teachers from the school (Mayhew & Edwards 1936). The history describes the school’s curriculum and organization, activities aimed at developing skills, parents’ involvement, and the habits of mind that the children acquired. A concluding chapter evaluates the school’s achievements, counting as a success its staging of the curriculum to correspond to the natural development of the growing child. In two appendices, the authors describe the evolution of Dewey’s principles of education and Dewey himself describes the theory of the Chicago experiment (Dewey 1936).

Glaser (1941) reports in his doctoral dissertation the method and results of an experiment in the development of critical thinking conducted in the fall of 1938. He defines critical thinking as Dewey defined reflective thinking:

Critical thinking calls for a persistent effort to examine any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the evidence that supports it and the further conclusions to which it tends. (Glaser 1941: 6; cf. Dewey 1910: 6; Dewey 1933: 9)

In the experiment, eight lesson units directed at improving critical thinking abilities were taught to four grade 12 high school classes, with pre-test and post-test of the students using the Otis Quick-Scoring Mental Ability Test and the Watson-Glaser Tests of Critical Thinking (developed in collaboration with Glaser’s dissertation sponsor, Goodwin Watson). The average gain in scores on these tests was greater to a statistically significant degree among the students who received the lessons in critical thinking than among the students in a control group of four grade 12 high school classes taking the usual curriculum in English. Glaser concludes:

The aspect of critical thinking which appears most susceptible to general improvement is the attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one’s experience. An attitude of wanting evidence for beliefs is more subject to general transfer. Development of skill in applying the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning, however, appears to be specifically related to, and in fact limited by, the acquisition of pertinent knowledge and facts concerning the problem or subject matter toward which the thinking is to be directed. (Glaser 1941: 175)

Retest scores and observable behaviour indicated that students in the intervention group retained their growth in ability to think critically for at least six months after the special instruction.

In 1948 a group of U.S. college examiners decided to develop taxonomies of educational objectives with a common vocabulary that they could use for communicating with each other about test items. The first of these taxonomies, for the cognitive domain, appeared in 1956 (Bloom et al. 1956), and included critical thinking objectives. It has become known as Bloom’s taxonomy. A second taxonomy, for the affective domain (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia 1964), and a third taxonomy, for the psychomotor domain (Simpson 1966–67), appeared later. Each of the taxonomies is hierarchical, with achievement of a higher educational objective alleged to require achievement of corresponding lower educational objectives.

Bloom’s taxonomy has six major categories. From lowest to highest, they are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Within each category, there are sub-categories, also arranged hierarchically from the educationally prior to the educationally posterior. The lowest category, though called ‘knowledge’, is confined to objectives of remembering information and being able to recall or recognize it, without much transformation beyond organizing it (Bloom et al. 1956: 28–29). The five higher categories are collectively termed “intellectual abilities and skills” (Bloom et al. 1956: 204). The term is simply another name for critical thinking abilities and skills:

Although information or knowledge is recognized as an important outcome of education, very few teachers would be satisfied to regard this as the primary or the sole outcome of instruction. What is needed is some evidence that the students can do something with their knowledge, that is, that they can apply the information to new situations and problems. It is also expected that students will acquire generalized techniques for dealing with new problems and new materials. Thus, it is expected that when the student encounters a new problem or situation, he will select an appropriate technique for attacking it and will bring to bear the necessary information, both facts and principles. This has been labeled “critical thinking” by some, “reflective thinking” by Dewey and others, and “problem solving” by still others. In the taxonomy, we have used the term “intellectual abilities and skills”. (Bloom et al. 1956: 38)

Comprehension and application objectives, as their names imply, involve understanding and applying information. Critical thinking abilities and skills show up in the three highest categories of analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The condensed version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom et al. 1956: 201–207) gives the following examples of objectives at these levels:

- analysis objectives : ability to recognize unstated assumptions, ability to check the consistency of hypotheses with given information and assumptions, ability to recognize the general techniques used in advertising, propaganda and other persuasive materials

- synthesis objectives : organizing ideas and statements in writing, ability to propose ways of testing a hypothesis, ability to formulate and modify hypotheses

- evaluation objectives : ability to indicate logical fallacies, comparison of major theories about particular cultures

The analysis, synthesis and evaluation objectives in Bloom’s taxonomy collectively came to be called the “higher-order thinking skills” (Tankersley 2005: chap. 5). Although the analysis-synthesis-evaluation sequence mimics phases in Dewey’s (1933) logical analysis of the reflective thinking process, it has not generally been adopted as a model of a critical thinking process. While commending the inspirational value of its ratio of five categories of thinking objectives to one category of recall objectives, Ennis (1981b) points out that the categories lack criteria applicable across topics and domains. For example, analysis in chemistry is so different from analysis in literature that there is not much point in teaching analysis as a general type of thinking. Further, the postulated hierarchy seems questionable at the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. For example, ability to indicate logical fallacies hardly seems more complex than the ability to organize statements and ideas in writing.

A revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson et al. 2001) distinguishes the intended cognitive process in an educational objective (such as being able to recall, to compare or to check) from the objective’s informational content (“knowledge”), which may be factual, conceptual, procedural, or metacognitive. The result is a so-called “Taxonomy Table” with four rows for the kinds of informational content and six columns for the six main types of cognitive process. The authors name the types of cognitive process by verbs, to indicate their status as mental activities. They change the name of the ‘comprehension’ category to ‘understand’ and of the ‘synthesis’ category to ’create’, and switch the order of synthesis and evaluation. The result is a list of six main types of cognitive process aimed at by teachers: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. The authors retain the idea of a hierarchy of increasing complexity, but acknowledge some overlap, for example between understanding and applying. And they retain the idea that critical thinking and problem solving cut across the more complex cognitive processes. The terms ‘critical thinking’ and ‘problem solving’, they write:

are widely used and tend to become touchstones of curriculum emphasis. Both generally include a variety of activities that might be classified in disparate cells of the Taxonomy Table. That is, in any given instance, objectives that involve problem solving and critical thinking most likely call for cognitive processes in several categories on the process dimension. For example, to think critically about an issue probably involves some Conceptual knowledge to Analyze the issue. Then, one can Evaluate different perspectives in terms of the criteria and, perhaps, Create a novel, yet defensible perspective on this issue. (Anderson et al. 2001: 269–270; italics in original)

In the revised taxonomy, only a few sub-categories, such as inferring, have enough commonality to be treated as a distinct critical thinking ability that could be taught and assessed as a general ability.

A landmark contribution to philosophical scholarship on the concept of critical thinking was a 1962 article in the Harvard Educational Review by Robert H. Ennis, with the title “A concept of critical thinking: A proposed basis for research in the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability” (Ennis 1962). Ennis took as his starting-point a conception of critical thinking put forward by B. Othanel Smith:

We shall consider thinking in terms of the operations involved in the examination of statements which we, or others, may believe. A speaker declares, for example, that “Freedom means that the decisions in America’s productive effort are made not in the minds of a bureaucracy but in the free market”. Now if we set about to find out what this statement means and to determine whether to accept or reject it, we would be engaged in thinking which, for lack of a better term, we shall call critical thinking. If one wishes to say that this is only a form of problem-solving in which the purpose is to decide whether or not what is said is dependable, we shall not object. But for our purposes we choose to call it critical thinking. (Smith 1953: 130)

Adding a normative component to this conception, Ennis defined critical thinking as “the correct assessing of statements” (Ennis 1962: 83). On the basis of this definition, he distinguished 12 “aspects” of critical thinking corresponding to types or aspects of statements, such as judging whether an observation statement is reliable and grasping the meaning of a statement. He noted that he did not include judging value statements. Cutting across the 12 aspects, he distinguished three dimensions of critical thinking: logical (judging relationships between meanings of words and statements), criterial (knowledge of the criteria for judging statements), and pragmatic (the impression of the background purpose). For each aspect, Ennis described the applicable dimensions, including criteria. He proposed the resulting construct as a basis for developing specifications for critical thinking tests and for research on instructional methods and levels.

In the 1970s and 1980s there was an upsurge of attention to the development of thinking skills. The annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Educational Reform has attracted since its start in 1980 tens of thousands of educators from all levels. In 1983 the College Entrance Examination Board proclaimed reasoning as one of six basic academic competencies needed by college students (College Board 1983). Departments of education in the United States and around the world began to include thinking objectives in their curriculum guidelines for school subjects. For example, Ontario’s social sciences and humanities curriculum guideline for secondary schools requires “the use of critical and creative thinking skills and/or processes” as a goal of instruction and assessment in each subject and course (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 30). The document describes critical thinking as follows:

Critical thinking is the process of thinking about ideas or situations in order to understand them fully, identify their implications, make a judgement, and/or guide decision making. Critical thinking includes skills such as questioning, predicting, analysing, synthesizing, examining opinions, identifying values and issues, detecting bias, and distinguishing between alternatives. Students who are taught these skills become critical thinkers who can move beyond superficial conclusions to a deeper understanding of the issues they are examining. They are able to engage in an inquiry process in which they explore complex and multifaceted issues, and questions for which there may be no clear-cut answers (Ontario Ministry of Education 2013: 46).

Sweden makes schools responsible for ensuring that each pupil who completes compulsory school “can make use of critical thinking and independently formulate standpoints based on knowledge and ethical considerations” (Skolverket 2018: 12). Subject syllabi incorporate this requirement, and items testing critical thinking skills appear on national tests that are a required step toward university admission. For example, the core content of biology, physics and chemistry in years 7-9 includes critical examination of sources of information and arguments encountered by pupils in different sources and social discussions related to these sciences, in both digital and other media. (Skolverket 2018: 170, 181, 192). Correspondingly, in year 9 the national tests require using knowledge of biology, physics or chemistry “to investigate information, communicate and come to a decision on issues concerning health, energy, technology, the environment, use of natural resources and ecological sustainability” (see the message from the School Board ). Other jurisdictions similarly embed critical thinking objectives in curriculum guidelines.

At the college level, a new wave of introductory logic textbooks, pioneered by Kahane (1971), applied the tools of logic to contemporary social and political issues. Popular contemporary textbooks of this sort include those by Bailin and Battersby (2016b), Boardman, Cavender and Kahane (2018), Browne and Keeley (2018), Groarke and Tindale (2012), and Moore and Parker (2020). In their wake, colleges and universities in North America transformed their introductory logic course into a general education service course with a title like ‘critical thinking’ or ‘reasoning’. In 1980, the trustees of California’s state university and colleges approved as a general education requirement a course in critical thinking, described as follows:

Instruction in critical thinking is to be designed to achieve an understanding of the relationship of language to logic, which should lead to the ability to analyze, criticize, and advocate ideas, to reason inductively and deductively, and to reach factual or judgmental conclusions based on sound inferences drawn from unambiguous statements of knowledge or belief. The minimal competence to be expected at the successful conclusion of instruction in critical thinking should be the ability to distinguish fact from judgment, belief from knowledge, and skills in elementary inductive and deductive processes, including an understanding of the formal and informal fallacies of language and thought. (Dumke 1980)

Since December 1983, the Association for Informal Logic and Critical Thinking has sponsored sessions at the three annual divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association. In December 1987, the Committee on Pre-College Philosophy of the American Philosophical Association invited Peter Facione to make a systematic inquiry into the current state of critical thinking and critical thinking assessment. Facione assembled a group of 46 other academic philosophers and psychologists to participate in a multi-round Delphi process, whose product was entitled Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction (Facione 1990a). The statement listed abilities and dispositions that should be the goals of a lower-level undergraduate course in critical thinking. Researchers in nine European countries determined which of these skills and dispositions employers expect of university graduates (Dominguez 2018 a), compared those expectations to critical thinking educational practices in post-secondary educational institutions (Dominguez 2018b), developed a course on critical thinking education for university teachers (Dominguez 2018c) and proposed in response to identified gaps between expectations and practices an “educational protocol” that post-secondary educational institutions in Europe could use to develop critical thinking (Elen et al. 2019).

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

A Brief History of the Idea of Critical Thinking

[C10] History of critical thinking

Module: Critical thinking

- C01. What is critical thinking?

- C02. Improve our thinking skills

- C03. Defining critical thinking

- C04. Teaching critical thinking

- C05. Beyond critical thinking

- C06. The Cognitive Reflection Test

- C07. Critical thinking assessment

- C08. Videos and courses on critical thinking

- C09. Famous quotes

Quote of the page

Popular pages

- What is critical thinking?

- What is logic?

- Hardest logic puzzle ever

- Free miniguide

- What is an argument?

- Knights and knaves puzzles

- Logic puzzles

- What is a good argument?

- Improving critical thinking

- Analogical arguments

For more detailed discussion about the history of critical thinking, please refer to this article by Dr. Joe Lau:

homepage • top • contact • sitemap

© 2004-2024 Joe Lau & Jonathan Chan

US history, civics scores drop for nation's 8th graders. What experts say is to blame.

Another set of test results shows the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on American students: National history scores dropped yet again, and eighth graders lost significant ground in civics for the first time.

Nearly all of the nation's eighth graders fell behind in U.S. history and civics in 2022 compared with 2018 on the National Assessment for Education Progress , also called the Nation's Report Card, according to scores released Wednesday. Declines were expected because of the shift to remote teaching and the loss of instruction time when the pandemic hit. But for these subjects, experts also worry friction over what students are taught in American history classes, especially about race and slavery, are a factor.

The test results follow a national plunge in reading and math performance among fourth- and eighth-grade students from the same year. Reading and math are getting much of the attention this year as teachers across the country focused on helping students catch up in those subjects. Subjects like history and science may become an afterthought, experts said. Fewer students took courses solely focused on U.S. history last school year than in the past, said Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, or NCES, which may have contributed to the drops.

"Whether students know U.S. history and civics is a national concern," Carr said on a call with reporters Tuesday. "A well-rounded education includes a grounding in these democratic principles."

Despite political pressure: US teachers lead complex history lessons on race and slavery

What do the test results show?

Fewer eighth graders scored at a level considered proficient in both subjects, and more students performed at below basic levels than before.

In U.S. history, the results show a continued drop in student achievement: Scores first dropped in 2018 after steadily climbing since the test was first given in 1994. Overall, 13% of students performed at or above what the NCES considers proficient in 2022, compared with 15% who reached proficiency in 2018. Students who perform at the proficient level, as defined by NCES, "demonstrate solid academic achievement performance and competency over challenging subject matter." The measure does not directly correlate to grade-level proficiency.

In addition, 46% performed at the basic level and 40% performed below the basic level, compared with 34% of students who performed at below the basic level in 2018. Students who perform at the basic level, as defined by NCES, demonstrate "partial mastery of prerequisite knowledge and skills fundamental for proficient work at each grade."

Can we recover? Half of nation's students fell behind a year after COVID school closures.

In civics, scores dropped notably for the first time since the test was administered in 1998. That follows a small drop between 2014 and 2018. Of all test takers in 2022, 22% of students performed at or above the national assessment's level of proficiency compared with 24% who reached proficiency or above in 2018. Forty-eight percent of students performed at the basic level and 31% of students performed below the basic level, compared with 27% who performed below the basic level in 2018. The civics test measures students' knowledge of American government and their ability to participate in civic activities.

Carr said she was shocked to see that so few students reached the proficient level in both subjects, calling the results "concerning." The most notable drop occurred among already low-performing students, Carr said, and there was no significant change for any specific racial or ethnic student group compared with 2018.

How did your state fare? Reading and math test scores fell across US during the pandemic

Critical thinking skills key to test success

Despite the national reading score inching down, Carr attributed the U.S. history and civics declines in part to a lack of critical-thinking skills among America's students.

On the history test, a nationally representative group of 8,000 students were queried on their knowledge of topics including democracy, culture and technology. One question prompted students to think about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, for example, and how it incorporates two ideas from the U.S. Constitution or Declaration of Independence.

"Students have to be able to read and know literacy skills, but they need critical thinking to know how to extrapolate an answer to that question," Carr said.

Carr said educators must get history content in front of students, especially with students opting out of classes solely dedicated to U.S. history. NCES said 68% of eighth graders took classes focused on U.S. history in 2022, 4% less than in 2018.

"It's not just about reading, it's about context, facts, dates, information about our constitutional system. Students don't know this information. That is why they're scoring so low."

More: How critical race theory went from conservative battle cry to mainstream powder keg

What should be done to address the deficits?

Schools should improve the quantity and quality of history and social studies content moving forward, experts and policymakers say.

- Education Secretary Miguel Cardona criticized recent attacks on U.S. history books and curricula , especially aspects involving race and racism. "Banning history books and censoring educators from teaching these important subjects does our students a disservice and will move America in the wrong direction."

- Kerry Sautner of the nonprofit National Constitution Center, which works to teach Americans about the Constitution, said that from conversations with teachers, she has gleaned that students are losing interest in history taught at school. "Students are beginning to disengage from − and become more fearful of expressing their opinions on − history, government and other topics important to civic learning," she said.

- Current and former members of the National Assessment Governing Board urge schools to act soon. "The young people who took these tests represent the future of our country. We must maintain high expectations while closing learning gaps that pre-date but were exacerbated by the pandemic," said Haley Barbour, a former assessment governing board chair and former Mississippi governor.

US history is complex: Scholars say this is the right way to teach about slavery, racism.

Contact Kayla Jimenez at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter at @kaylajjimenez.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

critical thinking chapter 11 US history. ... Social Studies Unit 1 Lesson 1 Review. 22 terms. crazycat_424. Preview. Great Depression & New Deal Test. 11 terms. mbf15. Preview. HIS 201 Mid-Term (chapter 7 set) 20 terms. EmmaCuthbertson1. Preview. History 11.1 - 11.3 Quiz Study Guide. 16 terms. Amartin922.

II. The Elements of Critical Thinking 6 10 common errors of logic in argumentative writing 14 III. Nurturing Critical Thinking in the Classroom 23 30 classroom techniques that encourage critical thinking IV. Primary Sources on Wisconsin History Available Free Online 29

Terms in this set (14) Critical Thinking. the ability to evaluate and analyze the process of thinking aka thinking about thinking. critical thinkers use... VALUES with REASONING to develop ANALYZING SKILLS. you value. accuracy, points of view, & significance. you reason by asking. purpose, assumptions, & implications.

In essence, history requires essential critical thinking skills, including judgment, synthesis, and creativity. As is often the case, the best way to begin to develop higher-order thinking skills is break them down into manageable chunks and practice putting them into action.

Reading Like a Historian lesson plans generally include four elements: Introduce students to background information so they are familiar with the period, events, and issues under investigation. Provide a central historical question that focuses students' attention. This transforms the act of reading into a process of creative inquiry.

Our mission is to improve educational access and learning for everyone. OpenStax is part of Rice University, which is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit. Give today and help us reach more students. This free textbook is an OpenStax resource written to increase student access to high-quality, peer-reviewed learning materials.

The "History and Critical Thinking Handbook" is a structured guide for the study of history. It ties together best practices, sound research, and lesson plans linked to the Wisconsin Model Academic Standards (and compatible with the Common Core Standards). Use it to help your students gain deeper and more meaningful connections to the past we ...

The project developed a framework of six historical thinking concepts to provide a way of communicating complex ideas to a broad and varied audience of potential users. Active from 2006 to 2014, the Historical Thinking Project provided social studies departments, local boards, provincial ministries of education, publishers and public history ...

Using History to Teach Critical Thinking Skills. One of the most important tools we can give our students is the ability to think critically. In this age of unlimited social media sharing, fake news, and hidden agendas, it has never been more important to be able to look at information and its source and determine if the information is accurate ...

In the didactics of history, critical thinking can be worked on through historical thinking, ... The lesson started with a collective reading of the information given in the textbook. Then, the teacher explained the information and provided answers to any questions that the students had. Lastly, the students had to complete the tasks given in ...

Social Studies. Critical Thinking in United States History uses fascinating original source documents and discussion-based critical thinking methods to help students evaluate conflicting perspectives of historical events. This process stimulates students' interest in history, improves their historical knowledge, and develops their analytical ...

Discover engaging history lesson plans, social studies resources, and primary source documents for your classroom. ... and diary entries, provides valuable insights into different historical periods, fostering critical thinking and historical analysis skills. Interactive History Lessons: Learning Through Engagement: Gone are the days of dry and ...

In addition, there are section review activities and some bonus activities. U.S. History Detective® Book 1 focuses on American history from the time of the first European explorers interacting with Native Americans through the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War. The lessons and activities in this book are organized around these time ...