Exploring the Mind–Body Connection Through Research

From ancient philosophers and religions to modern science, there have been different views on whether the mind and the body are related, if they can affect each other, and how that interaction can be possible.

Although mainstream contemporary science and healthcare practices tend to study and treat the mind and the body as separate entities, increasing research and evidence-based practices support the notion of a bidirectional relationship between the two.

This suggests that we might benefit more from acknowledging these interactions and adopting a more holistic approach to our health and wellbeing.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Mind–body connection: a philosophical take, psychology theories on mind–body interaction, 2 examples of the mind–body connection, can the mind heal the body 3 research areas, 10 empirical ways to heal your mind through your body, a look at the mechanisms of mind–body therapy, a take-home message.

Throughout centuries, philosophers and scientists have hypothesized about the mind–body connection. However, far from reaching a definite solution, we have been left with what many refer to as the mind–body problem .

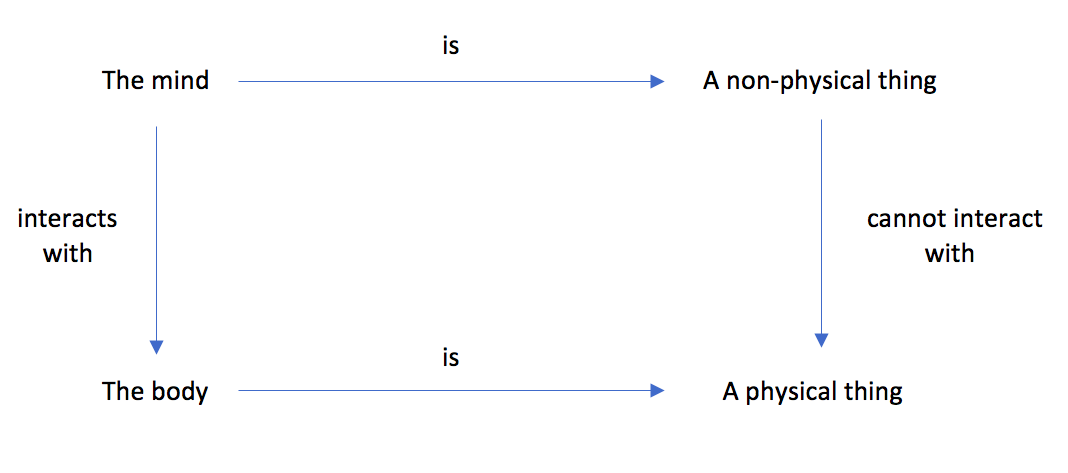

According to Westphal (2016), this is a logical problem with four statements about the nature and interaction of mind and body.

While considered to be true in isolation, they contradict each other when brought together, as illustrated below:

Figure 1. Illustration of the Mind–Body Problem. Adapted from “The Mind–Body Problem” by Westphal (2016). Copyright 2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Two main approaches within the philosophy of mind theorize about the mind–body connection by placing their attention in some of the statements above.

This approach posits that there is only one reality, composed only of either physical or non-physical substances (Kind, 2020).

Physicalism

This view assumes that everything existing is physical, including the mind. Here, the mind–body interaction is acknowledged only in the physical plane.

This is often related to traditional science, which tends to explain mental phenomena in terms of brain activities.

Using a metaphysical perspective, this standpoint sustains that reality is non-physical, and everything is either a mind or depends on the mind to exist.

In other words, this view proposes that reality depends on how our minds perceive and make sense of the world.

This philosophical standpoint theorizes that reality is composed of both physical and non-physical substances. Dualism posits that the body is physical, while the mind is not, treating mind and body as separate entities.

This worldview was developed by Rene Descartes during the 16th century, widely influencing modern science and compartmentalizing the study of body and mind (Descartes, 1960).

Dualism has evolved from views proposing that mind and body exist independently from one another without interaction, to ones that acknowledge a causal relationship between both.

According to Kind (2020), current views tend to be either interactionist property dualists or physicalists .

While physicalists would assert that the mind can be completely understood in terms of brain and neural networks, interactionist dualists would state that mental activities are rooted in the physical brain, yet are not reducible to these material properties (Westphal, 2016).

Non-dualism: Beyond the mind–body problem

This philosophical approach is often linked to several Eastern traditions and might provide further insight into the mind–body problem from a different angle.

Non-dualism proposes that the dualistic nature of things, such as mind/body, is an illusion.

Thus, there is no real separation between mind and body, as they are interdependent and need each other to exist (Loy, 1997).

Watch this short animated video by Embodied Philosophy to learn more about these approaches:

Interesting debate, but why and how is all this philosophical discussion relevant to mind–body research?

Although philosophy and empirical science may seem like independent silos, philosophy of mind is highly relevant to science and psychology in particular, as it informs the underlying assumptions and methods by which scientists conduct research and contribute to our understanding of mind–body interactions.

Behaviorists may hold a physicalist view, conceiving of the mind in terms of observable behavior expressed in or with the body.

While cognitivism acknowledges the body’s role, it tends to focus more on mental phenomena, reflecting a tendency towards dualism.

Finally, embodied approaches in psychology place equal value on the role of each, acknowledging their mutual interaction and adopting a more holistic view (Leitan & Murray, 2014).

Theories on emotions

These theories have evolved from considering emotions purely as physiological reactions to subjective interpretations to which we assign a valence depending on how they feel.

Cognitive appraisal theories

Pioneered by Magda Arnold and Richard Lazarus in the 1940s and 1950s respectively, the cognitive appraisal approach proposes that emotions result from the cognitive evaluation of an event in terms of their consequence as being pleasant or unpleasant (Shields & Kappas, 2006).

This is the background behind the use of the terms positive and negative emotions . Until the late 1990s, research on negative emotions broadly outnumbered studies on positive emotions, in part due to the perceived impact and relevance of negative emotions.

Broaden-and-build theory

Barbara Fredrickson (2000) posits that positive and negative affect complement each other and have the purpose of promoting the survival of the human species.

While negative emotions narrow our thought–action repertoire to respond more effectively to a threat, positive emotions expand this repertoire to build personal resources and pro-social behavior.

Remarkably, the broaden-and-build theory also states that “ positive emotions have an undoing effect on negative emotions ” (Fredrickson, 2000, p. 1).

Recent research in neuroscience has further supported this theory, suggesting that mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation can foster positive emotions and buffer against negative affect in a clinical population (Garland et al., 2010).

Cognitive theories

Although cognitive theories acknowledge the relationship between the mind (thoughts and subjective experiences of emotions) and the body (physical responses and behavior), they tend to place greater emphasis on the mental realm (Leitan & Murray, 2014).

This can be reflected in the lack of integration of the body within psychological interventions and psychotherapy (Hefferon, 2013).

Cognitive theory of psychopathology

Aaron Beck developed this model in the 1960s, contending that negative cognitions elicit unpleasant emotions, physical symptoms, and dysfunctional behavior.

He argues that these types of thoughts are the leading cause of depression, and therefore, psychotherapy should be aimed at addressing these mental processes to create positive change (Leitan & Murray, 2014).

Growth mindset theory

People with a growth mindset see challenges as opportunities to learn and grow, using their effort as a pathway to achieve mastery (Nussbaum & Dweck, 2008).

This involves mental processes grounded in the brain, such as increased awareness, attention, and the ability to adapt behavior to attain goals related to intrinsic motivation.

This framework is consistent with neuroplasticity, arguing that brain structures can reorganize, develop, and change according to our learning experiences (Ng, 2018).

Embodiment theories

This group of theories puts forward that bodily states and processes affect our psychological sphere and vice versa, contrasting with the disembodied view of the mind proposed by Descartes and early cognitivists.

Embodiment posits that our bodies mediate our interaction with the world and that mental symbols must be grounded in forms, such as words (Glenberg, 2010).

Embodied emotions

Considering previous theories on emotions, Prinz (2004) argues that although emotions are physical, they are essentially semantic too.

In other words, emotions can be conscious or unconscious perceptions of the body’s variations, but they are always grounded in language to an equal extent.

Embodied cognition (EC)

EC approaches generally agree that the type of body an organism has (e.g., human body) determines and shapes their perceptual and motor processes.

This means that the mind is grounded in the sensorimotor system, and that mind and body are equally relevant.

So rather than seeing the body as a server of the mind, EC posits that the body is actively and subjectively engaged in cognition (Leitan & Murray, 2014).

Embodiment theories allow bringing mind and body together into neuroscientific research, considering both participants’ subjective and physical experiences (Borghi & Caruana, 2015).

For example, a recent review of Beck’s Cognitive Theory considers neural and cognitive pathways to explain the effectiveness of Cognitive Therapy.

Research findings support the relationship between Cognitive Therapy and brain areas involved in initiating negative emotions and their cognitive control (Clark & Beck, 2010).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

To support the psychology theories of mind-body interaction, we look at two examples.

The mind–body connection of trauma

The polyvagal theory describes and explains different mechanisms of neural regulation and their related behaviors when perceiving a threat, involving the brain cortex, immune response, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal, and gut-brain axes (Porges, 2001).

The chain reaction activated under these circumstances is called the defense cascade , comprising four different responses (Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, & Carrive, 2015):

- Arousal . Cardiac regulation response promotes either engagement or disengagement with the environment after perceiving a threat.

- Fight-or-flight response . The inhibition of the vagus nerve and the sympathetic nervous system’s activation lead to an increase in metabolic activity to mobilize the body to either escape or confront the threat.

- Freeze response . When facing an unavoidable threat, the vagus nerve is stimulated, the metabolic activity drops, and the body freezes.

- Quiescent immobility . After the threat is gone, the parasympathetic system overrides, and metabolic activity drops dramatically so the body can rest and heal.

Understanding the pattern of these responses can help us understand and heal trauma (Kozlowska et al., 2015).

Porges (2001) argues that the traumatic experience leaves an imprint in the body, getting stuck in a trauma-response mode.

Mind–body interventions can help people to release these imprints.

The mind–body connection of emotions and immunity

Research supports a strong relationship between affective states and immune system response.

Sustained negative emotional states such as stress, depression, and anxiety can worsen immunity functions and affect other bodily functions.

Recent studies show that positive emotions are associated with a range of health outcomes, such as reducing ill-health symptoms, reducing pain, and increasing longevity.

In terms of immunity and illness, positive emotions have been related to enhanced immunity outcomes in immune-depressive conditions, such as cancer and HIV, and also in the nonclinical population after being exposed to the flu virus (Pressman & Black, 2012).

But how is this possible? One possible pathway is that positive emotions buffer the stress response in the body and its consequences. This aligns with the undoing effect posited by the broaden-and-build theory.

Other pathways suggest that positive emotions promote social bonds and changes in lifestyle habits, such as clean eating, sleeping, and regular exercise, thus improving immunity (Pressman & Cohen, 2005).

A study exploring the effects of meditation on the brain compared novices to experienced meditators.

Functional MRI showed that experienced meditators had more brain activity in areas related to attention and inhibition response and less activation in regions related to discursive emotions and cognitions, suggesting a correlation between hours of practice and brain plasticity (Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, Schaefer, Levinson, & Davidson, 2007).

Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) is a type of meditation derived from Buddhist traditions, aiming at cultivating unconditional love and kindness for yourself and others, as well as compassion, joy, and equanimity.

A systematic review suggests that LKM is an effective intervention for increasing positive emotions and reducing pain (Zeng, Chiu, Wang, Oei, and Leung, 2015).

Mindfulness-based psychotherapy

Mindfulness can be used as a therapeutic tool to develop awareness and acceptance of feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations, aligning to psychotherapy goals such as reducing ruminating thoughts or developing self-acceptance.

Applications linking the mind and the body can include mindful breathing and body scan exercises (Leitan & Murray, 2014).

A systematic review with meta-analysis found that mindfulness can help with depression, pain, weight management, schizophrenia, smoking, and anxiety (Goldberg et al., 2018).

Another study showed that a mindfulness program positively affects immunity and brain functions (Davidson et al., 2003).

Hypnotherapy

The American Psychological Association (2020) defines hypnosis as a therapeutic method used in clinical settings, where the client is induced into a state of relaxation by following suggestions from their psychotherapist.

It is hypothesized that in a relaxed state, the subconscious mind can more readily accept suggestions to change involuntary responses.

Clinical research evidence suggests that hypnosis can be useful for physical ailments such as managing pain and improving anxiety and depression.

One type of hypnosis is Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy , which has shown to effectively reduce irritable bowel syndrome symptoms and increase wellbeing (Peter et al., 2018).

Below are listed ten approaches believed to heal and improve the body and thereby heal and improve the mind.

1. Body psychotherapy

The body can be integrated as a central tool in psychotherapy by connecting bodily experiences to emotional and subjective experiences.

Body psychotherapy mainly uses body awareness of external and internal bodily sensations to accept and re-frame their meaning.

These mental health interventions can be beneficial not only for healing from trauma but also for wellbeing (Hefferon, 2013).

2. Exercise psychotherapy

Exercise can be used as a means to achieve psychotherapeutic goals, acknowledging that blending psychological and physical strategies can be more effective than using a standalone treatment.

This might include improving energy levels in clients with depression, reducing anxiety, or improving mastery and self-efficacy (Hefferon, 2013).

3. Somatic Experiencing (SE®)

SE® was developed by Dr. Peter Levine to regulate interrupted neuromuscular patterns due to trauma.

It consists of bringing awareness to physical sensations and reactions associated with a traumatic experience, helping clients describe physical patterns to integrate unconscious memories consciously.

Although there is limited empirical research, a systematic review including four studies on SE® suggests its effectiveness in improving post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Almeida, Gomez de Melo, & Cordeiro de Sousa, 2019).

4. Tension and trauma releasing exercises

Recently renamed as Self-induced Unclassified Therapeutic Tremor (SUTT), this method uses physical exercises to evoke natural tremor responses in the body to release tension associated with stress or trauma (Berceli, Salmon, Bonifas, & Ndefo, 2014).

Proposed by Dr. David Berceli, SUTT argues that although neuromuscular tremors are an innate response to events perceived as threatening, humans have learned to suppress them.

A pilot study (Berceli, et al. 2014) and a case study (Heath & Beattie, 2019) report that people experienced increased wellbeing and decreased stress at post-intervention measurements and follow-up.

Yoga is considered an ancient Eastern discipline integrating mind, body , and spirit through practices, typically including physical postures, breathing techniques, and meditation.

Yoga Chikitsa , or Yoga Therapy , refers to the use of yoga for improving ill-health conditions.

From a Western perspective, yoga has been used as an add-on therapy for improving symptoms of depression (Cramer, Lauche, Langhorst, & Dobos, 2013), anxiety (Cramer et al., 2018), PTSD (Nguyen-Feng, Clark, & Butler 2019), cancer (Cramer, Lange, Klose, Paul, & Dobos, 2012), and schizophrenia (Vancampfort et al., 2012).

Yoga benefits also relate to health and wellbeing outcomes in the general population (Hendriks, de Jong, & Cramer, 2017).

6. Dance therapy

Dance Movement Therapy (DMT) refers to “ the therapeutic use of movement aiming to further the emotional cognitive, physical, spiritual and social integration of the individual ” (European Association of Dance Movement Therapy, 2020, paragraph 1).

DMT seeks to understand and create new meanings from patterns of behavior by recognizing and exploring sensations, emotions, and stories emerging from the movement.

It is facilitated by a registered therapist, and it can be done individually or in a group setting (European Association of Dance Movement Therapy, 2020).

Studies suggest dance therapy ‘s effectiveness in improving ill health and trauma in clients with schizophrenia (Xia & Grant, 2009) and cancer (Bradt, Shim, & Goodill, 2015).

7. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR)

Initially developed by Edmund Jacobson in the 1920s, PMR seeks to decrease anxiety levels by gradually contracting and relaxing muscle groups to reduce physical tension and physiological activation (Hefferon, 2013).

A systematic review with meta-analysis of relaxation intervention including 10 studies on PMR suggests this can be an efficacious treatment for anxiety in different clinical settings (Manzoni, Pagnini, Castelnuovo, & Molinari, 2008).

8. Deep breathing

Intentional breath regulation to increase pulmonary capacity while reducing the rate of breathing cycles has been acknowledged as an effective method to improve both physical and mental health .

By consciously engaging the diaphragm, the practice of slow-paced deep breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system and inhibits the sympathetic nervous system, invoking a relaxation response and decreasing stress (Saoji, Raghavendra, & Manjunath, 2019).

Studies show that deep- breathing exercises can lower depressive and anxiety symptoms (Jerath, Crawford, Barnes, & Harden, 2015) and foster emotional wellbeing (Zaccaro et al., 2018).

9. Qigong and tai chi

Sharing the same philosophical roots, tai chi and qigong focus on the cultivation and enhancement of qi or life energy.

Along with yoga, they are considered meditative movement practices, and they include slow-paced and flow-like physical movements, as well as sitting, standing, or movement meditation; body shaking; and breathing techniques.

Underpinned by traditional Chinese medicine, they suggest that combining self-awareness with movement, meditation, and breath can promote mind–body balance and self-healing (Jahnke, Larkey, Rogers, Etnier, & Lin, 2010).

Several reviews have explored the effects of tai chi and qigong on different ill-health conditions such as cancer (Lee, Chen, Sancier, & Ernst, 2007), hypertension (Lee, Pittler, Guo, & Ernst, 2007), and cardiovascular disease (Lee, Pittler, Taylor-Piliae, & Ernst, 2007).

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Mind–body Therapy (MBT) is an umbrella term for therapeutic approaches combining physical and mental elements, such as those mentioned above.

MBT has been gradually recognized as an effective add-on treatment to traditional approaches for improving physical and mental health outcomes.

Research in the field of genomics has shed light on the relationship between gene expression and emotional states.

Similarly, studies in neuroimaging and neurophysiology have examined the connections and pathways between emotions and thoughts (Muehsam et al., 2017).

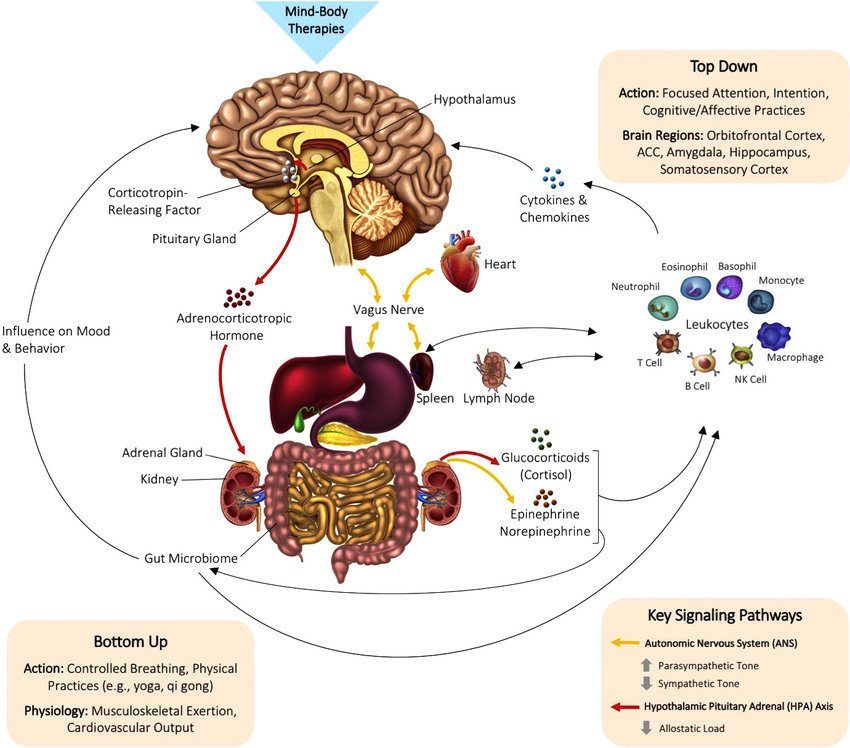

Figure 2. Biological Mechanisms of MBT. Extracted from “The embodied mind: a review on functional genomic and neurological correlates of mind-body therapies” by Muehsam, D., et al. (2017) Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 73, p. 167. Copyright 2016 by Elsevier Ltd.

The diagram above illustrates how MBT works, including top-down and bottom-up pathways.

Top-down interventions like meditation or mindfulness focus on thoughts and emotions. Their neurological correlates in turn influence the endocrine and nervous system, with ulterior changes in the body.

Bottom-up interventions centered on breathing and physical movements such as yoga, tai chi, and qigong stimulate the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems, resulting in changes in psychological states.

The mind–body connection is undeniable, yet our understanding of how they interact is still limited.

The dualistic view of modern science has provided many advances in the knowledge of each, though in an isolated way.

Contemporary research urges the need to take a holistic approach to explore the mind and body as an integrated entity and continue to explore the potential of MBT for alleviating disease and enhancing wellbeing.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Almeida, A. K., Gomez de Melo, S. C., & Cordeiro de Sousa, M. B. (2019). A systematic review of somatic intervention treatments in PTSD: Does Somatic Experiencing® (SE®) have the potential to be a suitable choice? Estudos de Psicologia , 24(3) , 237–246.

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Hypnosis. Retrieved on August 2020 from https://www.apa.org/topics/hypnosis.

- Berceli, D., Salmon, M., Bonifas, R., & Ndefo, N. (2014). Effects of self-induced unclassified therapeutic tremors on quality of life among non-professional caregivers: A pilot study. Global Advances in Health and Medicine , 3(5) , 45–48.

- Borghi, A.M., & Caruana, F. (2015). Embodiment theory. In: J.D. Wright (Ed.) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd edition, Vol 6. (pp. 420–426). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Bradt, J., Shim, M., & Goodill, S. W. (2015). Dance/movement therapy for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

- Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., Lutz, A., Schaefer, H. S., Levinson, D. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 104(27) , 11483–11488.

- Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2010). Cognitive theory and therapy for anxiety and depression: Convergence with neurobiological findings. International Journal of Psychophysiology , 14(9) , 418–424.

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Anheyer, D., Pilkington, K., de Manincor, M., Dobos, G., & Ward, L. (2018). Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety , 35(9) , 830–843.

- Cramer H., Lange, S., Klose, P., Paul, A., & Dobos, G. (2012). Yoga for breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer , 12 , 412–458.

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Langhorst, J., & Dobos, G. (2013). Yoga for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and Anxiety , 30 , 1068–1983.

- Davidson, R. J., Kabat-Zinn, J., Schumacher, J., Rosenkranz, M., Muller, D., Santorelli, S. F., … & Sheridan, J. F. (2003). Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine , 65(4) , 564–570.

- Descartes, R. (1960). Meditations on First Philosophy 1st Edition.

- European Association of Dance Movement Therapy. (2020). What is dance movement therapy? Retrieved on August 2020 from https://www.eadmt.com/?action=article&id=22.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and wellbeing. Prevention and Treatment , 3(0001a) , 1–25.

- Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review , 30(7) , 849–864.

- Glenberg, A. M. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science , 1(4) , 586–596.

- Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review , 59 , 52–60.

- Heath, R., & Beattie, J. (2019). Case report of a former soldier using TRE (tension/trauma releasing exercises) for post- traumatic stress disorder self-care. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health , 27(3) , 35–40.

- Hendriks, T., de Jong, J., & Cramer, H. (2017). The effects of yoga on positive mental health among healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine , 23(7) , 505–517.

- Hefferon, K. (2013). Positive psychology and the body: The somatopsychic side to flourishing . London: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Jahnke, R., Larkey, L., Rogers, C. Etnier, J., & Lin, F. (2010). A comprehensive review of health benefits of qigong and tai chi. American Journal of Health Promotion , 24(6) , 1–25.

- Jerath, R., Crawford, M. W., Barnes, V. A., & Harden, K. (2015). Self-regulation of breathing as a primary treatment for anxiety. Applications of Psychophysiological Feedback , 40 , 107–115.

- Kind, A. (2020). Philosophy of mind: The basics . New York: Routledge.

- Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade: Clinical implications and management. Harvard Review of Psychiatry , 23(4) , 263–287.

- Lee, M. S., Chen, K. W., Sancier, K. M., & Ernst, E. (2007) Qigong for cancer treatment: A systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Acta Oncologica , 46 , 717–722.

- Lee, M. S., Pittler, M. H., Guo, R., & Ernst, E. (2007). Qigong for hypertension: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Hypertension , 25 , 1525–32.

- Lee, M. S., Pittler, M. H., Taylor-Piliae, R. E., & Ernst, E. (2007). Tai chi for cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: A systematic review. Journal of Hypertension , 25 , 1974–1975.

- Leitan, N.D., & Murray, G. (2014). The mind-body relationship in psychotherapy: Grounded cognition as an explanatory framework. Frontiers In Psychology , 5(472) , 69–76.

- Loy, D. (1997). Nonduality: A study in comparative philosophy . New Jersey: Humanities Press.

- Manzoni, G. M., Pagnini, F., Castelnuovo, G., & Molinari, E. (2008). Relaxation training for anxiety: A ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BioMed Central Psychiatry , 8(41) , 1–12.

- Muehsam, D., Lutgendorf, S., Mills, P. J., Rickhi, B., Chevalier, G., Bat, N., … & Gurfein, B. (2017). The embodied mind: A review on functional genomic and neurological correlates of mind-body therapies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews , 73 , 165–181.

- Nguyen-Feng, V. N., Clark, C. J., & Butler, M. E. (2019). Yoga as an intervention for psychological symptoms following trauma: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Services , 16(3) , 513–524.

- Ng, B. (2018). The neuroscience of growth mindset and intrinsic motivation. Brain Sciences , 8(2) , 20.

- Nussbaum, A. D., & Dweck, C. S. (2008). Defensiveness versus remediation: Self-theories and modes of self-esteem maintenance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 34(5) , 599–612.

- Peter, J., Fournier, C., Keip, B., Rittershaus, N., Stephanou-Rieser, N., Durdevic, M., … & Moser, G. (2018). Intestinal microbiome in irritable bowel syndrome: Before and after gut-directed hypnotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences , 19 , 3619.

- Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology , 42(2) , 123–146.

- Pressman, S. D., & Black, L. L. (2012). Positive emotions and immunity. In S. C. Segerstrom (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of psychoneuroimmunology (pp. 92–104). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin , 131(6) , 925–971.

- Prinz, J. (2004). Embodied emotions . In R. C. Solomon (Ed.), Thinking about feeling: Contemporary philosophers on emotions. Series in affective science. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Saoji, A. A., Raghavendra, B. R., & Manjunath, N. K. (2019). Effects of yogic breath regulation: A narrative review. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine , 10(1) , 50–58.

- Shields, S. A., & Kappas, A. (2006). Magda B. Arnold’s contributions to emotions research. Cognition and Emotion , 20(7), 898–901.

- Vancampfort, D., Vansteelandt, K., Scheewe, T., Probst, M., Knapen, J., De Herdt, A., & De Hert, M. (2012). Yoga in schizophrenia: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica , 126(1) , 12–20.

- Westphal, J. (2016). The mind-body problem. Massachusetts Institute of Technology . Massachussets: MIT Press Books.

- Xia, J., & Grant, T. J. (2009). Dance therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 1 , 1–9.

- Zaccaro, A., Piarulli, A., Laurino, M., Garbella, E., Menicucci, D., Neri, B., & Gemignani, A. (2018). How breath control can change your life: A systematic review of psycho-physiological correlates of slow breathing. Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, 12 , 353 , 1–16.

- Zeng, X., Chiu, C. P., Wang, R., Oei, T. P., & Leung, F. Y. (2015). The effect of loving-kindness meditation on positive emotions: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 , 1693, 1–14.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Broad and concise amongs all the other sources. Thank you

Thanks for this very valuable research and proven work on the mind-body connection.

Thankyou for this wonderful article and your indepth research on recent studies. I’ll use this for my further research

Is an excellent article, the content is easy to read and very informative. It can be used as teaching resourcr

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

What Is the Health Belief Model? An Updated Look

Early detection through regular screening is key to preventing and treating many diseases. Despite this fact, participation in screening tends to be low. In Australia, [...]

Positive Pain Management: How to Better Manage Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is a condition that causes widespread, constant pain and distress and fills both sufferers and the healthcare professionals who treat them with dread. [...]

Mental Health in Teens: 10 Risk & Protective Factors

31.9% of adolescents have anxiety-related disorders (ADAA, n.d.). According to Solmi et al. (2022), the age at which mental health disorders most commonly begin to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP)

Mind-body health research interest group.

The Mind-Body Health Research Interest Group (MBH RIG) is an interdisciplinary research collective that was established in 2015 and became part of InCHIP in 2019. Its mission is to further education, research, clinical/practical application, and community outreach with a focus on the emerging potential connections between the Mind and Body. The MBH RIG Directors are Drs. Melissa Bray, Mary Guerrera, Ana Verissimo, and Sandra Bushmich, and its members include students, faculty, and staff from UConn Health Center; UConn Hartford; College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources; Neag School of Education; Operations and Information Management (OPIM) Department; and Student Health and Wellness. Non-UConn partners include Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Copper Beech Institute, and Root Success Solutions™ LLC.

Leadership Team

Upcoming events:, the yes institute topic: supporting lgbtq+ youth health in today’s climate.

Towards a Fairer Future

When: March 6, 2024 | 6:30 to 7:30 PM EST University of Connecticut InCHIP Virtual – WebEx

Join us in learning from the YES Institute, a non-profit organization focused on the health of LGBTQ+ youth. They will be using both relevant research and vital personal experiences to help professionals, researchers, and allies improve health outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Our Speakers The YES Institute’s mission is toprevent suicide and ensure the healthydevelopment of all youth throughpowerful communication and education on gender and orientation.

Past Events:

“Hygge and Happiness,” Claus Elholm Andersen, Ph.D. “Introduction to Ayurveda,” Vanas hree Belgamwar, BAMS

Watch the recordings on InCHIP’s YouTube channel here .

“Go Outside, Go Within: Mindful Nature Connection for Surviving Zoom and Nature Deficit Disorder”

Watch the recording on InCHIP’s YouTube channel here .

“Connection: Exploring the Science of Mindfulness and Relationships”

Watch a recording on InCHIP’s YouTube channel here .

Mindfulness

How mindfulness affects the brain and body, interview with neuroscientist david vago..

Posted March 16, 2023 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- What Is Mindfulness?

- Find a mindfulness-based therapist

- Despite its growing popularity, research on mindfulness presents methodological challenges.

- Mindfulness meditation can lower blood pressure, increase heart rate variability, improve inflammation, and help with pain management.

- Meditation can prevent age-related atrophy in the brain.

Neuroscientist David Vago begins each day with meditation. Like millions worldwide, Vago sees his mindfulness practice as good medicine holistically promoting health. Inspired by the staggering power of the human mind, Vago has studied the neurobiological mechanisms of mind-body practices for almost 15 years.

Mindfulness – a moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness of one’s internal states and surroundings – boasts benefits ranging from stress reduction to enlightenment. However, scientific investigations of mindfulness paint a complex picture. Yes, it can boost physical and psychological well-being. But it is not a panacea and can even be counter-indicated for certain individuals. Despite significant progress over the past two decades, research on mindfulness is still riddled with various conceptual and methodological challenges. This is why, according to Vago, the question What does mindfulness really do? has no simple answer.

Mindfulness Is Far More Than Following Your Breath

Scientists like Vago study the effects of mindfulness by enrolling participants in eight-week interventions. There are four core practices in a mindfulness-based intervention:

- Focused attention . Mindfulness of breath or a body scan.

- Open monitoring . Being aware of thoughts arising and passing without attaching to them.

- Movement-based practices . Hatha yoga or walking meditation.

- Informal practices . Showing up with mindfulness in day-to-day life. Sometimes, the interventions can include constructive practices (loving-kindness meditation) that help individuals construct positive psychological states.

What about these practices that, moment by moment, begin to shift things for people? According to Vago, the possibilities are profound and consequential: people can get more insight into the workings of their minds; hone their ability to respond rather than to react to circumstances; gain glimpses of non-dual states; renew their understanding of the self and its place in the world; feel a deeper connection to others. “This is the Buddhist prescription for a flourishing life,” says Vago. “Everything else – the improved health and the calm – are merely side effects.”

The Gift of Paying Attention

One of the core faculties that mindfulness hinges on is attention. Attention might not have the buzzwordy flair of mindfulness . Yet, it’s one of our most precious resources. Attention, according to the father of modern psychology, William James, is somewhat of a curator of our lives (“My experience is what I agree to attend to.”) Poet Mary Oliver called paying attention “our endless and proper work.”

“Instructions for living a life: Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.”

Philosopher Simone Weil considered attention “the rarest and purest form of generosity .” “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same as prayer. It presupposes faith and love , ” wrote Weil. Attention can even alter the perception of another limited human resource – time. As haste and demands leave many of us with the depleting feeling of weeks slipping by, attention can act as a salve to slow down the perceived passage of time (“ The best way to capture moments is to pay attention,” wrote Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founder of mindfulness-based stress reduction.)

Perhaps, then, one of the gifts of mindfulness can be found in nurturing our faculty of attention – to move it more nimbly, with more ease, between the micro and macro of our circumstances. To direct its precise lens on a single cherry blossom's pale, velvety petals and cast its vast reach beyond all boundaries . To discern content (thoughts, emotions) and context (relation to thoughts and emotions). To revel in the wonder that we are alive at this very moment, together with billions of other sentient beings near and far the blooming trees. This reminder will likely kindle a profound appreciation: for our impermanent existence and our affinity with others.

Here’s David Vago, on how mindfulness meditation affects the mind-brain-body.

MP: How does mindfulness benefit health?

DV: The most well-established health benefits of mindfulness meditation include a decrease in blood pressure and perceived stress , an increase in heart rate variability, and an improvement of inflammatory markers.

Mindfulness has also been shown to help with pain management . The experience of pain has physical and emotional components. While we can’t escape the physical effects of pain on the body, the emotional side (for example, catastrophizing pain) can be reduced through meditation. Namely, by impacting attentional biases, meditation can shift the way we attend to pain. For example, people with chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia can begin to approach pain-related, fearful stimuli, which can help them become less hypervigilant, less avoidant, and less reactive to environmental pain-related signals.

In our lab, we are exploring the glymphatic system – a brain system associated with clearing metabolic waste. One of the ways that sleep benefits us is by eliminating toxins from our brains. Our findings show that by impacting the glymphatic system, mindfulness meditation – a low metabolic state – can act similarly to sleep and have restorative effects on brain functioning.

MP: How do mindfulness intervention outcomes compare to other treatments like therapy ?

DV: Overall, mindfulness improves various outcomes related to emotion , cognition , and the self (for example, rumination and empathy) – if we compare it to doing nothing else. Compared to treatments like SSRIs , anxiety drugs, or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness interventions work as well as these gold-standard treatment modalities but don’t often outperform them.

MP: Does mindfulness change the brain?

DV: Meditation instigates morphological changes in the brain. The challenge is quantifying them. Because the brain responds to every learning experience, it’s always changing. You’re always learning – no matter what you’re doing – thus, your brain is always changing. While there are different neuroscience methods to investigate how the brain changes shape and size, it’s difficult to show these changes in healthy individuals. In fact, it’s controversial what actually changes. However, for brains that have significant atrophy (for example, adults over 65 or brain trauma patients), morphological changes are detected more readily. This is in part because many atrophy processes are based on inflammation and meditation improves inflammation markers.

Functionally , brain imaging shows that mindfulness can activate the brain’s insula, the dorsal anterior cingulate, and the frontal-parietal network. The frontal parietal network is a group of brain structures that are critical for flexibly switching between processing the external world and the internal world. This helps us not get stuck in our thoughts. Often, our thoughts can have the quality of “stickiness.” For many of us, our most common thought is some version of “I’m not good enough.” We spend half of our lives in our heads, repeating to ourselves the various ways how we are not enough. These thoughts have us convinced that we are failing at some unachievable standard set by ourselves and society. As we elaborate on them, they start sticking. Hence our habit of rumination.

Mindfulness meditation helps develop the capacity to toggle between our thoughts and what’s happening in the world. The frontoparietal network also helps support meta-awareness – knowing where our mind is at any point. Moreover, research shows that individuals who develop high trait mindfulness can better regulate their emotions by increasing prefrontal activity and decreasing amygdala activity.

Whether or not meditation increases brain size has to do with preventing age-related atrophy in the brain. Most of meditation’s effects on cognition – executive functioning , attention, memory – don’t necessarily improve those skills in healthy individuals. It’s not like if you practice a lot of meditation. You’ll get super memory or outstanding decision-making abilities. Instead, brain areas that show increases in size with meditation are simply not atrophying in normal age-related ways.

After age 22, everyone’s cognitive capacities begin to decrease. We can see this as atrophy in specific regions in the brains of older adults. Thus, those older than 65 show the most increased brain size from an eight-week mindfulness course since meditation helps stabilize their cognition and prevents decline. The brains of older meditators don’t atrophy like most healthy, aging individuals because they are strengthening their abilities to keep those crucial brain areas active.

Many thanks to David Vago for his time and insights. Vago is an Associate Professor and visiting faculty at the University of Virginia’s Contemplative Sciences Center, Research Lead for the well-being app RoundGlass, and Director of Neurosciences for the International Society for Contemplative Research.

Ponte Márquez, P. H., Feliu-Soler, A., Solé-Villa, M. J., Matas-Pericas, L., Filella-Agullo, D., Ruiz-Herrerias, M., ... & Arroyo-Díaz, J. A. (2019). Benefits of mindfulness meditation in reducing blood pressure and stress in patients with arterial hypertension. Journal of Human Hypertension , 33 (3), 237-247.

Van Dam, N. T., Van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., ... & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science , 13 (1), 36-61.

Wittmann, M., & Schmidt, S. (2014). Mindfulness meditation and the experience of time. Meditation–neuroscientific approaches and philosophical implications , 199-209.

Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., ... & Maglione, M. A. (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 51 (2), 199-213.

Nardi, W. R., Harrison, A., Saadeh, F. B., Webb, J., Wentz, A. E., & Loucks, E. B. (2020). Mindfulness and cardiovascular health: Qualitative findings on mechanisms from the mindfulness-based blood pressure reduction (MB-BP) study. PLoS One , 15 (9), e0239533.

Zollars, I., Poirier, T. I., & Pailden, J. (2019). Effects of mindfulness meditation on mindfulness, mental well-being, and perceived stress. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning , 11 (10), 1022-1028.

Christodoulou, G., Salami, N., & Black, D. S. (2020). The utility of heart rate variability in mindfulness research. Mindfulness , 11 , 554-570.

Bower, J. E., & Irwin, M. R. (2016). Mind–body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: A descriptive review. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity , 51 , 1-11.

Klimecki, O., Marchant, N. L., Lutz, A., Poisnel, G., Chetelat, G., & Collette, F. (2019). The impact of meditation on healthy ageing—the current state of knowledge and a roadmap to future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology , 28 , 223-228.

Marianna Pogosyan, Ph.D. , is a lecturer in Cultural Psychology and a consultant specialising in cross-cultural transitions.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- About UniSA

Professor Lorimer Moseley AO

- Bradley Distinguished Professor UniSA Allied Health & Human Performance

- City East Campus (C7-35)

- tel +61 8 830 21416

- email [email protected]

Alternative contact

- Available for media comment

- Research Degree Supervisor

Alternative contact details

Administrative Officer (Research) Tracy Jones: +61 8 8302 2454 Works - Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday

- External engagement & recognition

- Teaching & student supervision

I am fascinated by humans. That fascination has led me to become a physiotherapist, then a neuroscientist, a pain scientist and a science educator. After working as a physiotherapist for seven years, I combined my clinical work with research - a PhD at the University of Sydney Pain Management Research Institute and research positions at the University of Queensland, University of Sydney and Oxford University, UK. My official qualifications are: DSc, PhD, FAAHMS, FACP, HonFFPMANZCA, HonMAPA, BAppSc(Phty)(Hons). In 2020, I was made an Officer of the Order of Australia, for "distinguished service to medical research and science communication, to education, to the study of pain and its management, and to physiotherapy, ... Read more

UniSA Allied Health & Human Performance

Focused on shaping community wellbeing, UniSA Allied Health & Human Performance educates future health professionals and delivers solutions-based research that addresses global health needs.

- Google Scholar

- ResearcherID

I am fascinated by humans. That fascination has led me to become a physiotherapist, then a neuroscientist, a pain scientist and a science educator. After working as a physiotherapist for seven years, I combined my clinical work with research - a PhD at the University of Sydney Pain Management Research Institute and research positions at the University of Queensland, University of Sydney and Oxford University, UK. My official qualifications are: DSc, PhD, FAAHMS, FACP, HonFFPMANZCA, HonMAPA, BAppSc(Phty)(Hons). In 2020, I was made an Officer of the Order of Australia, for "distinguished service to medical research and science communication, to education, to the study of pain and its management, and to physiotherapy, to humanity at large."

I was appointed University of South Australia's Inaugural Chair in Physiotherapy, and Professor of Clinical Neurosciences, in 2011 and was honoured to be appointed a Bradley Distinguished Professor in 2021.

I have been supported by NHMRC Fellowship/Investigator funding since my return to Australia in 2009.

I am the Chair of PainAdelaide Stakeholders' Consortium , which brings together Adelaide's pain researchers, clinicians and consumers to 'put our heads together' for persistent pain. I established and lead the non-profit grassroots movement called Pain Revolution , which is committed to a bold but realistic vision that all Australians will have access to the knowledge, skills and local support to prevent and overcome persistent pain. Our annual Flagship Event is the Pain Revolution Rural Outreach Tour. Our awareness and fund-raising challenge 'Go the Distance!' encourages pepole to walk, run or ride to meet their own personal challenge, raising awareness of the problem of persistent pain and the possibilities that are emerging with each new scientific discovery. Our ongoing capacity-building programs - Local Pain Educator Program and Local Pain Collectives Project , aim to (i) embed in rural and regional communities the capacity to prevent and overcome persistent pain, and (ii) develop local pain networks to provide sustainable capacity. Learn about Pain Revolution here: painrevolution.org.

I led the establishment of UniSA's Innovation, Implementation & Clinical Translation in Health ('IIMPACT in Health') and was Director from inception until 2023. IIMPACT has grown to about 100 researchers, publishing over 500 scientific articles a year, with a research income of about $2m a year. The research in IIMPACT centres around taking a truly 'biopsychosocial' to a range of significant health conditions, and the primary role that allied health professionals play in discovery and treatment. Central to IIMPACT has been an 'innovation to implementation' approach, led by clinical and consumer needs, with both playing important roles in every phase of the research journey.

I lead the Body in Mind Research Group within IIMPACT. This research group investigates the role of the brain and mind in chronic pain. Pain is a huge problem - it affects 20% of the population and costs western societies about as much as diabetes and cancer combined. We have a major public engagement and education focus, with our articles and videos attracting over 13 million reads/views, including being on repeat in hospitals and community health centres in several countries. Body in Mind, or 'BIM', research is supported by MRFF and NHMRC Grants and industry funding, and many BIMsters have NHMRC scholarship or fellowship support. We have eight nationalities and several disciplines represented.

For those of you keen on 'metrics' , my main metrics are: Total number of papers - about 400; Google scholar H-index - 95; Average Field-weighted citation index - 1.9 - 2.6 in the fields in which I am most active; competitive grant funding - about $22 million over 20 years.

I supervise PhD students and host post-doctoral fellows for between 1 - 3 years. Expressions of interest in joining our group should be directed in the first instance to [email protected]. We have many such expressions of interest each year so it is best to make contact at least 12 months in advance.

I co-developed, with David Moen and Sam Chisolm, a consumer facing resource called Tame the Beast - go to tamethebeast.org.

I established bodyinmind.org in 2009 and was Chief Editor until we handed it to the IASP. This library of over 900 blog posts is now hosted on their consumer/clinician facing website called RELIEF. You can visit that library here: https://relief.news/relief-to-provide-body-in-mind-content-as-a-free-resource/

Pain revolution is revamping our website , but until then you can find some factsheets you can download and print in a range of languages here: https://www.painrevolution.org/factsheets

I have authored or co-authored several books. You can find them here: https://www.noigroup.com/shop/

Please note that I receive royalties for these books. I have no financial interest in the publisher noigroup.com. I do however, have relevant disclosures - in the last five years, I have received support from the following entities: Reality Health, Kaiser Permanente, ConnectHealth UK, workers compensation agencies in Australia and abroad, AIA Australia, Arsenal Football Club, the International Olympic Committee. Professional and scientific bodies have reimbursed me for travel costs related to presentation of research on pain at scientific conferences/symposia.

I am on the Board of Pain Australia.

I live and work on Kaurna Country.

Professional Associations

Australian Academy of Health & Medical Science

Australian Physiotherapy Association

Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australia New Zealand College of Anaesthetists

International Association for the Study of Pain

Australian Pain Society

Qualifications

Doctor of Philosophy University of Sydney

Bachelor of Applied Sciences University of Sydney

- Professional associations

Research focus

- Clinical Sciences

- Neurosciences

- Human Movement and Sports Science

- Medical and Health Sciences

Excludes commercial-in-confidence projects.

Targeting unhelpful pain beliefs to promote physical activity in people with knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis, NHMRC - Project Grant, 01/10/2019 - 31/10/2024

Gippsland Local Pain Educator Program, Gippsland Lakes Community Health, 01/11/2019 - 31/12/2021

Does targeting pain-related beliefs in people with knee osteoarthritis increase physical activity?, Arthritis Australia - Project Grants, 01/01/2018 - 30/06/2020

The role of the brain and mind in chronic pain, NHMRC - Research Fellowship, 01/01/2014 - 31/12/2019

Resolve: A new treatment - sensorimotor retaining with Explaining pain - for chronic low back pain, NHMRC - Project Grant, 01/01/2015 - 31/12/2019

Central Adelaide Local Health Network Incorporated Scholarship, Central Adelaide Local Health Network Incorporated, 01/03/2016 - 31/12/2017

Testing the imprecision hypothesis of chronic pain, NHMRC - Project Grant, 01/01/2013 - 31/12/2016

Joint pain without a joint? An investigation into the nature of postsurgical pain following joint replacement, Arthritis Australia, 01/01/2014 - 30/07/2016

Research outputs for the last seven years are shown below. Some long-standing staff members may have older outputs included. To see earlier years visit ORCID , ResearcherID or Scopus

Open access indicates that an output is open access.

Journal Articles

Conferences, non traditional outputs.

- Collaborations

Teaching & student supervision

Pain Sciences:

Lorimer gives lectures on pain sciences to undergraduate and post-graduate courses

- Courses and programs

Courses I teach

- SCALH 90001 Pain Education SC (2023)

- Research degree supervision

Supervisions from 2010 shown

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- March 1, 2024 | VOL. 19, NO. 3 CURRENT ISSUE pp.2-13

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Neurological Evidence of a Mind-Body Connection: Mindfulness and Pain Control

- Raymond St. Marie , M.D. ,

- Kellie S. Talebkhah , M.S.

Search for more papers by this author

Chronic pain is commonly defined as an unpleasant experience felt in any part of the body that persists longer than 3 months and that may or may not be associated with a well-defined illness process ( 1 ). Chronic pain affects up to 28%–65% of the U.S. population and often leads to reduced occupational activity and subsequent economic loss ( 2 ). In 2008, the costs of chronic pain in the United States ranged from $560 to $635 billion ( 3 ). In addition to health care costs, chronic pain results in lost economic productivity, as well as exorbitant financial compensation for persons unable to work ( 3 ). Providing pain relief that is clinically significant and sustained and that has few adverse effects is the goal of chronic pain management ( 4 ). Here, we assess the role of the mind-body connection (i.e., social, emotional, and behavioral factors influencing physical health) and how it relates to mindfulness techniques that can alleviate chronic pain ( 5 ).

Currently, the most commonly used and most widely available treatment modality for chronic pain is medication, with the goal of maximizing efficacy with the fewest toxic side effects ( 6 , 7 ). The most commonly prescribed agents are opioid-based medications, nonopioid agents (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen), and adjuvant medications (anticonvulsants, muscle relaxants, corticosteroids, topical-numbing agents, and antidepressants) ( 8 ). However, there are nonpharmacologic treatment modalities, including mindfulness techniques, exercise programs, brain and spinal cord stimulation, and virtual-reality hypnosis ( 9 ). The most effective results are typically seen in multidisciplinary pain clinics, but these clinic services are not widely available to all patients ( 10 ).

Numerous studies have demonstrated the inadequacy of current pain management modalities and the need for newer, more widely available interventions ( 6 , 11 ). Physicians should consider supplementing or replacing medications with nonpharmacologic modalities such as mindfulness ( 12 , 13 ). Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, defines mindfulness as "paying attention to something, in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally" ( 14 ). The goal of mindfulness in the treatment of chronic pain is to cultivate a quality of openness and experiential acceptance of pain, rather than rejecting or avoiding the pain ( 14 ). In this way, mindfulness can be beneficial in treating chronic pain through a noninvasive approach via the mind-body connection ( 11 ).

The Role of Mindfulness

Mindfulness has been used as a supplement to medication for various conditions, including cancer, diabetes, and eating disorders ( 15 – 17 ). Dr. Kabat-Zinn describes mindfulness as being "more in touch with the fullness of [one's] being through a systematic process of self-observation, self-inquiry, and mindful action" ( 18 ). For many patients who experience chronic pain, these concepts of inward reflection may not appear to be possible, helpful, or preferable to medication. Furthermore, such patients may not associate the pervasive, intense nature of their condition with a psychological or spiritual idea ( 18 ). However, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that mindfulness can be effective in the treatment of chronic pain ( 19 ).

Many studies have independently examined the effectiveness of mindfulness in pain reduction, the neurological effects of mindfulness, and the neurophysiology of pain ( 20 – 22 ). However, few studies have examined these aspects simultaneously while also investigating the relevant neurophysiological processes in relation to pain reduction ( 23 ).

Brain Regions Involved in Pain Processing

The various brain regions involved in central pain processing have specific, understood roles in the anticipation, evaluation, and response to pain. The lateral thalamus and primary somatosensory cortex are associated with the sensory processing and discriminative aspects of painful stimuli ( 24 ). The anterior cingulate and insular cortices have been shown to play a role in the emotional and arousal responses to pain, as well as in attentional processing, which is the way a person's brain filters relevant information from distractions in order to appropriately respond to a stimulus ( 24 – 26 ). The hippocampus and amygdala, alternatively, are involved in the anticipation of pain, while the thalamus modifies afferent input to these limbic structures ( 25 , 27 ) ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1. Brain Regions Involved in Pain Processing a

a The open circles represent the specific role of a brain region in pain processing, and the small black squares represent neurological changes associated with mindfulness in conjunction with decreasing pain.

Structural Brain Changes

Neuroplasticity can occur within the nociceptive pathways involving the aforementioned brain regions in people who practice mindfulness-based stress reduction ( 24 ). Mindfulness-based stress reduction is a structured, weekly meditation program that has standardized guidelines and involves a combination of mindfulness meditation, body awareness, and yoga ( 19 ). Su et al. ( 28 ) examined functional MRI (fMRI) scans of the brains of persons who completed a 6-week mindfulness-based-stress-reduction course. fMRI was conducted at baseline and 6 weeks after completion of the course. Participants who completed the course experienced significantly less subjective pain elicited by a thermal stimulus compared with control subjects who did not complete the course. Attenuation of pain was associated with increased neuronal connectivity from the anterior insular cortex and dorsal anterior mid-cingulate cortex. These results suggest that mindfulness plays a role in the modulation of brain connections and networks that underlie the subjective experience of pain ( 28 ).

Grant et al. ( 20 ) used structural MRI scans to examine a group of individuals who were experts (defined as >10,000 hours of practice) in meditation techniques. Compared with control subjects, the expert meditators had a decreased sensitivity to pain, which was associated with significantly thicker dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and significantly thicker secondary somatosensory cortex. These results suggest that long-term mindfulness practice may affect cortical thickness in pain-related brain areas, thus causing changes in pain sensitivity ( 20 ).

Signal-Processing Changes

Changes in the processing of pain signals, specifically in areas involved in pain anticipation and attentional processing, have been reported ( 25 ). Lutz et al. ( 25 ) used fMRI in a study demonstrating that mindfulness techniques can modulate neural brain processes before (anticipation) and during (attentional) painful stimuli. In this study, expert meditators (compared with control subjects) reported significantly less unpleasantness from a painful stimulus elicited during meditation, which was associated with enhanced activity in the dorsal anterior insula and the anterior mid-cingulate, two areas of the brain associated with attentional processing. Meditators also had significantly less activity in the amygdala, an area associated with pain anticipation. These findings support the mindfulness principle, which suggests that openness of oneself to an experience of pain (attentional processing) rather than avoidance (anticipation) may reduce the mind's tendency toward anxiety, which can further exacerbate pain ( 25 ).

In another fMRI study, Zeidan et al. ( 29 ) reported that subjective decreases in pain sensation were associated with increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula, two areas involved in the emotional regulation of pain processing as well as attentional processing. Increased activation in the orbitofrontal cortex, an area known to reframe contextual evaluation of sensory events similar to attentional processing, was also observed. Additionally, reductions in pain unpleasantness were associated with thalamic deactivation ( 29 ).

The aforementioned studies demonstrated that there are neurological changes involved in differentiating between the sensory experience of pain (subjective intolerance to pain) and the emotional response to pain (hopelessness and fear) ( 20 , 24 , 25 , 29 ). Identifying these experiences as separate, or "uncoupling" them from the emotional response via mindfulness techniques, allows one to distinguish between unpleasant sensations and secondary emotions in the context of pain, thus reducing the body's sensitivity to the unpleasant experience ( 18 ).

Autonomic Nervous System Process Changes

The autonomic nervous system plays a role in the anticipation of and response to pain ( 30 ). Through its integration with structures in the upper brainstem, hypothalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and amygdala, the autonomic nervous system integrates bodily sensation with emotion and generates homeostatic autonomic responses ( 30 ). Lush et al. ( 31 ) reported that women with fibromyalgia who completed a mindfulness-based stress-reduction program had decreases in basal sympathetic tone. Sympathetic nervous system responses typically exacerbate the physical symptoms of illness ( 30 ). Therefore, mindfulness-based stress reduction appears to play a role in attenuating autonomic nervous system responses, which can reduce chronic pain ( 31 ).

Braden et al. ( 32 ) reported that mindfulness-based stress-reduction practices were linked to alterations in the autonomic nervous system, specifically an increase in regional frontal-lobe blood flow, which was associated with the attenuation of chronic back pain and affective depression symptoms ( 32 ). The frontal lobe plays a role in reframing the contextual evaluation of an event ( 25 ). Therefore, this increase in hemodynamic activity is presumably associated with the reevaluation and awareness of changes in emotional state, a key concept of mindfulness ( 32 ). Being consciously aware of pain and uncoupling it from negative emotion are keys to decreasing the subjective experience of pain ( 18 , 32 ).

Conclusions

Although mindfulness has been well studied as an effective supplement or augmentation for pain management, few studies have simultaneously examined the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological alterations that can occur as a result of mindfulness to actively reduce pain. There are some contradictory studies that have demonstrated the potential ineffectiveness of mindfulness; however, it is important to consider that mindfulness is a modality that has minimal risks and can be beneficial. Further studies are needed to expand our understanding of the neurophysiological and psychological mechanisms underlying the effects of mindfulness on pain processing and perception.

Key Points/Clinical Pearls

Chronic pain affects up to 65% of the U.S. population and often leads to reduced occupational activity and subsequent economic loss.

Current pain management modalities are inadequate, leaving opportunity for nonpharmacological modalities such as mindfulness.

Mindfulness involves nonjudgmental observation of and present-moment engagement with one's physical, emotional, and mental states.

There are proven neuroanatomical and neurophysiological changes associated with mindfulness in reducing the subjective experience of pain.

1. Anand K, Craig K: New perspectives on the definition of pain . Pain 1996 ; 67:3–6 Google Scholar

2. Gerdle B, Bjork J, Henriksson C, et al. : Prevalence of current and chronic pain and their influences upon work and healthcare- seeking: a population study . J Rheumatol 2004 ; 31(7):1399–1406 Google Scholar

3. Gaskin J, Richard P: The Economic Costs of Pain in the United States: Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transofming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research . Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2011 Google Scholar

4. Finnerup N, Sindrup S, Jensen T: The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain . Pain 2010 ; 150:573–581 Crossref , Google Scholar

5. Ray O: How the mind hurts and heals the body . Am Psychol 2004 ; 59(1):29–40 Crossref , Google Scholar

6. Falope E, Appel S: Substantive review of the literature of medication treatment of chronic low back pain among adults . J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2015 ; 27(5):270–279 Google Scholar

7. Gilron I, Jensen T, Dickenson A: Combination pharmacotherapy for management of chronic pain: from bench to bedside . Lancet Neurol 2013 ; 12:1084–1095 Crossref , Google Scholar

8. Fine P: Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older patients . Clin J Pain 2004 ; 20(4):220–226 Crossref , Google Scholar

9. Turk D, McCarberg B: Non-pharmacological treatments for chronic pain: a disease management context . Dis Manag Health Outcomes 2005 ; 13(1):19–30 Crossref , Google Scholar

10. Okifuji A, Turk A, Kalauokalani D, et al. : Clinical outcome and economic evaluation of multidisciplinary pain centers , in Handbook of Pain Syndromes: Biopsychosocial Perspectives . Edited by Block A,Kremer E,Fernandez E. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1999 , pp 77–97 Google Scholar

11. Lee C, Crawford C, Hickey A: Mind-body therapies for the self-management of chronic pain symptoms . Pain Med 2014 ; 15:S21–S39 Crossref , Google Scholar

12. Lynch M, Watson C: The pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a review . Pain Res Manag 2006 ; 11(1):11–38 Crossref , Google Scholar

13. Burdick D: Mindfulness Skills Workbook for Clinicians and Clients: 111 Tools, Techniques, Activities, and Worksheets . Eau Claire, Wisc, PESI Publishing and Media, 2013 , p9 Google Scholar

14. Kabat-Zinn J: The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain . J Behav Med 1985 ; 8(2):163–190 Crossref , Google Scholar

15. Zhang J, Zhou Y, Feng Z, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on posttraumatic growth of Chinese breast cancer survivors . Psychol Health Med 2017 ; 22(1):94–109 Crossref , Google Scholar

16. Caluyong M, Zambrana A, Romanow H, et al. : The relationship between mindfulness, depression, diabetes self-care, and health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes . Mindfulness 2015 ; 6(6):1313–1321 Crossref , Google Scholar

17. Cook-Cottone C: Incorporating positive body image into the treatment of eating disorders: a model for attunement and mindful self-care . Body Image 2015 ; 14:158–167 Crossref , Google Scholar

18. Kabat-Zinn J: Wherever you go, there you are . New York, MJF Books, 1994 , p 6 Google Scholar

19. Wong S, Chan F, Wong R, et al. : Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and multidisciplinary intervention programs for chronic pain: a randomized comparative trial . Clin J Pain 2011 ; 27:724–734 Crossref , Google Scholar

20. Grant J, Courtemanche J, Duerden E, et al. : Cortical thickness and pain sensitivity in Zen meditators . Emotion 2010 ; 10(1):43–53 Crossref , Google Scholar

21. Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, et al. : Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis . J Psychosom Res 2004 ; 57:35–43 Crossref , Google Scholar

22. Shapiro S, Carlson L, Astin J, et al. : Mechanisms of mindfulness . J Clin Psychol 2006 ; 62(3):373–386 Crossref , Google Scholar

23. Greeson J, Eisenlohr-Moul T: Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain , in Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches . Edited by Baer R . San Diego, Academic Press, 2014 , pp269–292 Google Scholar

24. Nakata H, Sakamoto K, Kakigi R: Meditation reduces pain-related neural activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, secondary somatosensory cortex, and thalamus . Front Psychol 2014 ; 5:1489. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01489 Crossref , Google Scholar

25. Lutz A, McFarlin D, Perlman D, et al. : Altered anterior insula activation during anticipation and experience of painful stimuli in expert meditators . Neuroimage 2013 ; 64:538–546 Crossref , Google Scholar

26. Apkarian A, Bushnell M, Treede R, et al. : Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease . Eur J Pain 2005 ; 9(4):463–484 Crossref , Google Scholar

27. Ploghaus A, Narain C, Tracey I, et al. : Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network . J Neurosci 2001 ; 21(24):9896–9903 Crossref , Google Scholar

28. Su I, Liang K, Cheng K, et al. : Pain perception can be modulated by mindfulness training: a resting-state fMRI study . Front Hum Neurosci 2016 ; 10:570 Crossref , Google Scholar

29. Zeidan F, Martucci K, Kraft R, et al. : Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation . J Neurosci 2011 ; 31(14):5540–5548 Crossref , Google Scholar

30. Cortelli P, Giannini G, Favoni V, et al. : Nociception and autonomic nervous system . Neurol Sci 2013 ; 34:S41–S46 Crossref , Google Scholar

31. Lush E, Salmon P, Floyd A, et al. : Mindfulness meditation for symptom reduction in fibromyalgia: psychophysiological correlates . J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2009 ; 16(2):200–207 Crossref , Google Scholar

32. Braden BB, Pipe TB, Smith R, et al. : Brain and behavior changes associated with an abbreviated 4-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course in back pain patients . Brain Behav 2016 ; 6(3):e00443 Google Scholar

- Biomarkers of stress as mind–body intervention outcomes for chronic pain: an evaluation of constructs and accepted measurement 2 April 2024 | Pain, Vol. 1

- Oxytocin Modulation in Mindfulness-Based Pain Management for Chronic Pain 15 February 2024 | Life, Vol. 14, No. 2

- Physical Pain as a Source of Spiritual and Artistic Inspiration in Jackson Hlungwani’s Work 1 November 2023 | Pharos Journal of Theology, No. 104(5)

- Sikhism and Its Contribution to Well-Being 1 August 2023

- Amy Gillespie , Ph.D. , and

- Catherine J. Harmer , D.Phil.

- Unlocking Performance Excellence: Review of Evidence-Based Mindful Meditation 8 August 2022 | Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Vol. 150, No. 4

- The intersection between integrative medicine and neuropathic pain: A case report EXPLORE, Vol. 18, No. 2

- Proprioceptive afferents differentially contribute to effortful perception of object heaviness and length 4 February 2021 | Experimental Brain Research, Vol. 239, No. 4

- Issue 1 Editorial

- Issue 1 Research 1

- Issue 1 Research 2

- Issue 1 Research 3

- Issue 1 The MBMRC

- Issue 2 Editorial I

- Issue 2 Editorial II