Korean War: 4 SEQ Samples

The topic of the Korean War revolves around the reasons why it happened and whether it was a proxy war or just a civil war. These are just samples for students to refer to so that they have a model to use when answering a similar question.

For ease of download, I have included the pdf download in the box below.

Download Here!

1. Explain how post-war developments in Asia and Europe impacted Korea.

( P ) Post-WWII development in Asia impacted Korea as it led to the necessity to contain the spread of communism in the Asia-Pacific.

( E ) In October 1949, China turned communist, and China signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance in February 1950 with the Soviet Union. The communists viewed Korea as a potential platform to expand their global influence into the Asia-Pacific. Hence, Mao, the leader of communist China, focused his attention on the assistance of North Korea, which served as a counter-balance to the American influence in Japan. As a result, the National Security Council prepared a top-secret report called the NSC-68, stressing the importance of the Americans to contain the spread of communism on a global basis.

( E ) Thus, the communist take-over in China meant that Korea had become an essential platform over which both ideologies wanted to gain control to prevent the spread of communism.

( L ) Thus, post-war development made Korea a battleground in the Cold War.

( P ) Post-war development in Europe also significantly impacted Korea as the Soviets had gained greater leverage against Western powers.

( E ) In August 1949, the Soviet Union had successfully exploded its first atomic bomb. This event created atomic parity with the USA, meaning that the USA could not use atomic diplomacy as an effective threat against the Soviet Union.

( E ) Therefore, by early 1950, the Soviet Union was more inclined to support a possible North Korean invasion of the South. Kim Il-Sung approached Stalin for help in April 1950. Kim persuaded Stalin that he could easily and swiftly conquer the South. Stalin was concerned about the alliance of America and Japan and saw this as an opportunity to counter American influence in the region.

( L ) Thus, encouraged by their attainment of atomic parity, Stalin granted Kim permission to attack the South.

2. “The Americans were responsible for the escalation of the Korean War.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) The escalation of the Korean War was a result of American involvement.

( E ) The American intervention triggered China’s entry into the Korean War. By Oct 1950, UN troops had captured Pyongyang, occupied two-thirds of North Korea and reached the Yalu River. The presence of the UN troops was alarming to the Chinese, who felt threatened. Hence, when they ignored the repeated Chinese warnings, China joined the North Korean troops fighting the war.

( E ) Instead of being a civil war between North and South Koreas, it escalated into a more significant regional conflict – involving the USA and its allies on one side and North Korea and China and the USSR.

( L ) Therefore, US involvement had worsened the conflict.

( P ) However, the Americans were not to be blamed for the escalation of the Korean War.

( E ) This escalation was caused by both the Soviet Union and China. The Soviet Union and China supported Kim Il Sung’s government in North Korea. They sought to extend the communist sphere of influence. The Soviet Union also supplied the North with the weaponry that would help it to invade the South. Even though Stalin did not actively encourage Kim to invade the South, he eventually approved and asked China to help Kim. Kim Il Sung also did not take any direct action against South Korea until he had attained Stalin’s approval and support.

( E ) Therefore, the indirect involvement of the Soviet Union gave Kim the confidence to carry out the invasion, which led to the Korean War and escalated into a proxy war that saw Chinese troops and Soviet-trained troops in the war.

( L ) Thus, the Soviet Union and China were responsible for the Korean War.

( J ) In conclusion, the USA had its motivations for becoming involved in Korea as part of the Cold War against the Soviet Union. Hence, the USA is responsible for escalating the Korean War. The USA saw the North Korean invasion of South Korea as part of a Soviet plan to gain hegemony in Asia and eventually control the world. As a result, they led to a significant force to counter the North Korean advance, which also led to the involvement of Chinese troops and thus escalating the Korean War.

3. “South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) I agree that South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( E ) Border clashes between North Korea and South Korea were standard in 1949 and 1950. South Korea started these clashes to try to capture territory in North Korea. However, Syngman Rhee’s aggressive actions in planning border clashes backfired as they failed to achieve their goals. These failed invasions set the stage for North Korea’s invasion of the South in June 1950, which started the Korean War as they convinced North Korea of the ineffectiveness of the South Korean forces.

( E ) For example, South Korean warships on North Korean military installations provoked the North Korean army and resulted in fierce fighting by both sides. It also affected the USA’s goodwill towards South Korea and made the USA even more reluctant to send heavy weapons to South Korea. As a result, these border clashes revealed the weaknesses of the South Korean forces and their inability to launch successful offensive attacks. Desertions by South Korean soldiers were common and showed the unpopularity of Rhee’s regime.

( L ) Hence, South Korea was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( P ) However, I’m afraid I disagree with the statement because the Soviet Union was also blamed for the Korean War.

( E ) The Soviet Union supported North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. In early 1950, Stalin changed his mind and became more willing to help Kim’s invasion after developments like the communist victory in China, the Soviet explosion of the atomic bomb and the US Defensive Perimeter. Hence, the Soviet Union trained the North Korean army and provided military equipment such as tanks, guns and fighter planes. As a result, Soviet support for Kim’s invasion of South Korea led to the outbreak of the Korean War.

( E ) It helped make the North Korean army strong and gave them the military capability to launch an offensive attack on South Korea. It also gave Kim the confidence to invade South Korea because he could count on Stalin and Mao to help him should the invasion go wrong. Indeed, the North Korean forces launched a surprise attack on South Korea on 25 June 1950 and started the Korean War.

( L ) Hence, USSR was to be blamed for the Korean War.

( J ) In conclusion, I partly disagree that South Korea was responsible for the Korean War. South Korea incited frequent border clashes, which increased tensions between the two sides and made the conflict inevitable. Within this setting of increasing provocation by the South, the Soviet Union could offer its support to North Korea to mount the offensive and invade South Korea, which then triggered the outbreak of the Korean War.

At the same time, Soviet Union’s financial, military, technical and logistical support for North Korea did help to make the North Korean army strong. It gave them the military capability and the confidence to launch a successful offensive attack and invasion of South Korea. Hence, both sides are responsible for the Korean War

4. “The Korean War was mainly about the reunification of the two Koreas.” How far do you agree with this statement? Explain your answer.

( P ) The Korean War was mainly because of the desire by both sides for unification.

( E ) The Korean peninsula was halved at the 38th parallel after Japan had surrendered and Japanese soldiers left Korea. The USSR occupied the northern part temporarily and the USA the southern region. The United Nations called for an election in 1947 to establish a single government to reunite Korea, but the USSR refused to hold it. As a result, Korea splintered into two halves in 1949. Both Syngman Rhee (President of South Korea) and Kim Il Sung (President of North Korea) claimed the right to rule over Korea. As a result, there were border raids and conflicts between small groups of soldiers from the North and South.

( E ) Syngman kept provoking the North Koreans by launching raids into North Kore but failed. On the other hand, Kim was also determined to unite the Korean peninsula under communism. With the blessings of the USSR, the North Korean army invaded South Korea.

( L ) Thus, a civil war broke out with Koreans fighting against each other because both sides desired unification.

( P ) However, the Korean War was primarily due to interference by external powers.

( E ) The USSR was to be blamed for the Korean War. From the start, Stalin had backed Kim Il-Sung to run a communist government in Korea due to Stalin’s attempt to keep North Korea communist and spread communism across Asia. The USSR supplied North Korea with military equipment and training. As the leader of the communist bloc, it also encouraged China to back North Korea directly, which led to Kim daring to invade South Korea in 1950.

( E ) The USSR was thus to blame because it used Korea as the ground for a proxy war to demonstrate its superiority over its superpower rival – the United States.

( L ) Thus, the Korean War was because of external powers.

( P ) The US was also responsible for the outbreak of the Korean War.

( E ) During the Cold War, the US was determined not to let Korea fall into the hands of communism. When World War II ended, the US set up a democratic government in Korea. They even supported Syngman Rhee – a leader who abused his authority in South Korea.

( E ) As a result, when North Korean soldiers invaded South Korea, the US was determined to protect South Korea, activated a UN coalition force under its leadership, and intervened in the conflict, turning a civil war into an international problem.

( L ) Thus, the Korean War was a result of American intervention.

( J ) In conclusion, the Korean war was fundamentally a conflict between the two Koreas, as armed contact between the two Koreas had already occurred before the intervention of the US and the Soviet Union. The presence of the support of the superpowers merely sought to escalate the conflict to a new level given the increase in terms of military aid, resulting in North Korea’s crossing of the 38th Parallel in June 1950.

This is part of the History Structured Essay Question series. For more information on the Korean War, you can click here . For more information about the O level History Syllabus, you can click here . You can download the pdf version below.

Other chapters are found here:

- Treaty of Versailles

- League of Nations

- Rise of Stalin

- Stalin’s Rule

- Rise of Hitler

- Hitler’s Rule

- Reasons for World War II in Europe

- Reasons for the Defeat of Germany

- Reasons for World War II in Asia-Pacific

- Reasons for the Defeat of Japan

- Reasons for the Cold War

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Reasons for the End of the Cold War

Critical Thought English & Humanities is your best resource for English, English Literature, Social Studies, Geography and History.

My experience, proven methodology and unique blend of technology will help your child ace their exams.

If you have any questions, please contact us!

Similar Posts

Stalin’s Rule: 5 SEQ Samples

Another common Structure Essay Question for O Level history is Stalin’s Rule. How can we answer this topic well? Read more to find out how to score for this topic.

End of Cold War: 4 SEQ Samples

The End of the Cold War signalled the end of hostility between the Western world and the Soviet Union. Read on to find out how to answer SEQs on this topic.

League of Nations: 3 SEQ Samples

Do you have difficulty understanding the why the League of Nations failed? Here are three sample SEQ that can help you understand and ace your examinations!

Social Studies Comparison Format

Is your child confused about the Social Studies Comparison question? If they are, read this blog to understand how to answer these sort of questions!

Social Studies SBQ (Source Based Questions)

Mastering Social Studies Source Based Questions is one of the most difficult tasks. Read on to find out more.

Rise of Stalin: 5 SEQ Samples

A common question for O Level history is the rise of Stalin. In this blog post, I have included some sample essay questions to help students score well.

Summer 2020

Korean War: Open Questions

– Gregg Brazinsky, Chen Jian, Sheila Miyoshi Jager, Jiyul Kim, and Michael Devine

Historians examine what we still need to know about the so-called “Forgotten War.”

Scholarship is driven by open questions. What don’t we know? The Korean War is no exception.

Researchers have never stopped exploring the conflict, and the opening of new archives in the U.S., Europe, and Asia are helping them do it.

For our Summer 2020 issue, “Korea: 70 Years On,” we asked four distinguished historians to address what they see as the most important open questions about the war and its legacy.

Open Question: The Lived Experience of North Koreans in the War

The Korean War was experienced in different ways by different people. Much of the literature about the war in the United States focuses on the experiences of a relatively predictable set of actors: political and military leaders and U.S. combat forces. When bookstores and public libraries have any books on the Korean war at all, they tend to be military histories that are written from the American perspective. They focus primarily on U.S. strategic thinking or the combat experience of American forces.

While the new international history of the war that developed in the 1990s expanded on this perspective by incorporating the communist world, much of it was still focused on political elites – Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin and the like. Missing from these elite-driven histories is a sense of the war’s traumatizing impact on those who felt it most viscerally: the Korean people.

For three years, the Korean War turned the entire Korean peninsula into a ghastly war zone. Millions perished and violence was endemic. The waves of retaliation and counter retaliation carried out by leftist and rightist partisans in many areas rent the fabric of Korean society so badly that it took decades to recover. Even those who survived had their lives shattered, their property destroyed, and their opportunities narrowed. Historians have been far slower to turn their attention to these more human dimensions of the war.

Even those who survived had their lives shattered, their property destroyed, and their opportunities narrowed. Historians have been far slower to turn their attention to these more human dimensions of the war

Scholars have done a little better when it comes to the war’s impact on South Korea. We now have a limited understanding of how the presence of massive numbers of UN forces, the transition to a wartime economy, and the political chaos caused by the fall and recapture of cities and villages permanently changed life in South Korea. Our understanding of these phenomenon is still insufficient, but it is growing nonetheless as the most recent generation of historians finds new sources and tests different theoretical approaches.

The lived experience of war in the North has been almost completely neglected. When Americans pay attention to wartime North Korea at all, they mostly see a place where their armies slaughtered – and were slaughtered by – a ferocious and evil adversary, and a landscape in which major cities were transformed into ashes and rubble by relentless aerial bombing.

Americans don’t see it as a place where real human beings struggled for survival, mourned the loss of family members, and suffered permanent trauma because of the three years that they spent living under constant fear of death. And they care little about the social or cultural history of the war there. As a result, we know about the massive bombing campaigns carried out by American fighter planes and wartime atrocities committed by South Korean forces in North Korea. Yet we don’t understand much about their real human impact.

When it comes to everyday life in North Korea during the Korean War, there are many basic questions that are still unanswered: How did North Koreans learn to cope with the violence and loss that surrounded them? How did they see their own leaders, their obligations to their country, and the demands of military service? What were social relations between North Koreans and the hundreds of thousands of Chinese Volunteers who crossed the Yalu to fight alongside them like? There is scarcely a single book in the English language that takes any of these questions as its main point of departure.

Historians urgently need to start asking these questions. Contemporary North Korea cannot be understood without first understanding the complete suspension of everything that was considered normal there during the war. One of the reasons that, seventy years later, the Korean War has still not officially ended is Americans don’t realize how these experiences hardened North Korean hatred and mistrust of the United States.

For Americans who take media representations of North Korea as a bizarre rogue state at face value, Pyongyang’s unyielding commitment to its nuclear program seems hostile and irrational. But in North Korea, where the war is critical to the state’s raison d’être, the suffering that it caused remains a critical part of the society’s collective historical memory – and colors how North Koreans and their leaders see almost every issue. A powerful military is seen first and foremost not as a way of threatening neighbors, but as a way of preventing the horrors that were visited on North Korea seventy years ago from happening again.

None of this is to say that North Koreans were innocent victims during the Korean War, or that they did not commit an ample number of their own atrocities in South Korea. The evidence that it was Kim Il Sung who turned a smoldering civil war into a full-scale international conflict is undisputable, as is the evidence of the terror inflicted on South Korea by DPRK forces during the summer of 1950.

But this does not mean we should not recognize the basic humanity of our former adversary. If we do not do so, the Korean War might never end, and could even be reignited.

Gregg A. Brazinsky is professor of history and international affairs at the George Washington University. He is the author of Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War and Nation Building in South Korea: Korean, Americans, and the Making of a Democracy . Follow him on Twitter @GBrazinsky.

Open Question: The “Long Peace” Between America and China

One of the great open questions about the Korean War regards what did not happen after the armistice was signed in July 1953.

In retrospect, it is almost miraculous that another Korea-style direct military confrontation between China and the United States did not happen for almost two decades following the end of the conflict. The possibility of such a confrontation was virtually eliminated only by the Chinese-American rapprochement in the early 1970s.

This Chinese-American “long peace” has been largely ignored by scholars of Chinese-American relations. Yet the absence of a war between China and America in the wake of the Korean War should in no circumstances be taken for granted.

Throughout the 1950s and the 1960s, China and the United States regarded each other as a mortal enemy. For Beijing, “imperialist America” was China’s number one foe, serving as a principal justification of its support to revolutionary insurgences in East Asia. This animus was also the main source of Mao Zedong’s excessive domestic mobilization, which culminated in such disastrous Maoist programs as the Great Leap Forward and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

For Washington, Communist China, compared with the Soviet Union, was a “more daring, therefore, more dangerous enemy.” Although the emphasis of America’s global Cold War strategy lay in Europe, and the Soviet Union was America’s presumed primary enemy, a large portion of America’s resources also were deployed in East Asia to cope with the “Chinese communist threats” there.

It is no surprise, then, that at several critical moments of tension in the wake of the Korean War, China and the United States could have easily slid into another Korea-style war – or an even more destructive conflict. Yet it was also the memory of Korea, as well as the lessons that Beijing and Washington had learned from it, that effectively prevented China and the United States from engaging in another direct military confrontation.

Vietnam is a case in point. In the spring and summer of 1954, it seemed the Vietnamese Communists, backed by China, would soon grasp victory in the First Indochina War. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower adopted the “domino theory” to describe Washington’s perception of the grave impact of allowing communist revolutions following the Chinese model to spread unchecked in East Asia.

Chinese policymakers noted Washington’s warnings. The Chinese repeatedly called their Vietnamese comrades’ attention to the danger of a “direct American intervention.” At a crucial meeting with Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nyugen Giap in early July 1954, Zhou Enlai spent many long hours beseeching the Vietnamese to abandon their pursuit of “total victory” in the war.

“We must remember the lessons of Korea,” Zhou emphasized, “the most important is to avoid an American intervention.” Ho and Giap accepted Zhou’s advice, opening the door to the Geneva Peace Accord on Indochina.

In retrospect, it is almost miraculous that another Korea-style direct military confrontation between China and the United States did not happen for almost two decades following the end of the conflict.

In the Taiwan Straits crises of 1958, China and the United States once again faced the grim prospect of a direct military showdown. Both sides showed restraint. When the Chinese artillery units shelled the Nationalist-controlled Jinmen islands, Mao emphatically ordered his frontal commander to ensure that “American ships would not be hit.” On the American side, U.S. warships tasked with protecting Nationalist convoys stayed beyond the range of the Chinese artillery, so as to avoid undesirable incidents.

In spring 1965, as the Vietnam War was rapidly escalating, both Chinese and American policymakers kept the lessons of Korea in their minds. Zhou and Chen Yi, China’s foreign minister, asked Pakistan and Britain to help deliver the following messages to President Lyndon B. Johnson: (I) China will not provoke war with the United States; (II) What China says counts; (III) China is prepared; and (IV) If the United States bombs China that would mean war and there would be no limits to it.

Zhou specifically mentioned that the Americans had failed to heed the warning message that he sent to Washington, via India, before China intervened in Korea. This time, China also changed the delivery channel, swapping a dubious intermediary for two staunch American geopolitical allies.

_underway_at_sea_on_16_August_1958.jpg)

Washington treated the Chinese warning signals seriously this time. From 1965 to 1969, China dispatched a total of 320,000 engineering and anti-aircraft troops to North Vietnam. Yet no Chinese combat troops were sent to Vietnam. U.S. ground forces did not invade North Vietnam, and aerial bombing of the North was confined to areas north of the 20th parallel, keeping a “safe distance” from Chinese borders. Another Chinese-American war indeed was avoided.

There was a sophisticated yet crucial reason for this which should be highlighted. Beijing and Washington regarded each other as enemies. But it seems that each side was willing to count on the consistent, “limited rationality” of the other to avoid another Korea-type war. There appeared to exist a critical “mutual confidence” of a certain kind in Beijing’s and Washington’s strategic thinking in the wake of Korea. Without acknowledging the legitimacy of the other side’s policy goals and ideological commitments, leaders of both countries nevertheless held a degree of faith in the other side’s willingness and capacity to persist in a limited and pragmatic course of action in accordance with its own rationale, logic and perceived interests.

Beijing’s international strategies and policies, upon examination, reflect a specific truth: In spite of its aggressive rhetoric and behavior, Mao's China was not an expansionist power as the term is typically defined in Western strategic discourse. Though it did use force, Beijing’s aim was not direct control of foreign territory or resources. Rather, China sought the spread of its revolution's influence to "hearts and minds" around the world. It was this aspiration for "centrality," rather than the pursuit of "dominance," that characterized the foreign policy of Mao's China.

The factors I describe above not only led to a “long peace.” They also present important implications for understanding China's external behavior then, now, and in the future. They merit closer examination and further study.

Chen Jian is Distinguished Global Network Professor of History at NYU-Shanghai and NYU. He is also Hu Shih Professor of History Emeritus at Cornell University. He is nearing completion of a major biography of Zhou Enlai.

Open Question: The Lasting Legacies of Korean War Special Operations

The failure rate of the missions was shocking , the full scope of which we still do not know because the records are incomplete, lost or remain inaccessible. In a literal sense, the history of Special Operations in Korea is truly the forgotten part of the Forgotten War. Thousands of Koreans – we do not know the actual number – never returned from their suicidal missions behind enemy lines in North Korea during the Korean War. Their courage and lives were expendable. But their sacrifices, and those of the Americans who led them, helped to restore U.S. unconventional and covert warfare capabilities that were almost completely eliminated after the Second World War.

The Korean War caught the United States with its proverbial pants down. The post-World War II demobilization precipitously reduced the Armed Forces by nearly 90 percent – from over 12 million to 1.5 million by June 1947. For many service personnel, the pace was too slow and demands for faster demobilization were backed with protests and demonstrations. The process, by necessity both political and social, was “willy-nilly,” and the consequences for military capability and readiness were devastating. In September 1946, the War Department estimated that the combat effectiveness was down to just 25 percent for all units in the Pacific. A 1952 Army study concluded, “When future scholars evaluate the history of the United States during the first-half of the twentieth century they will list World War II demobilization as one of the cardinal mistakes.”

A little noticed loss in the demobilization was the almost complete elimination of special operations units. World War II had spawned a plethora of these organizations – famed units such as Army Rangers, Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), Marine Raiders, and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) – that accumulated an expertise paid for in blood. They conducted the kind of irregular, covert and clandestine activities known as special operations. These military activities were usually conducted behind enemy lines and ranged from intelligence collection and direct actions such as raids, sabotage, assassination, and kidnapping to guerilla warfare and psychological operations.

The landmark National Security Act of 1947, which reorganized how the U.S. would handle the foreign policy and military challenges of the Cold War, created the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to provide national-level strategic intelligence. The scope of its concerns was quickly expanded to include covert paramilitary operations of the kind conducted by wartime organizations.

A year later, the National Security Council decided that the CIA would be responsible for, among other things, covert propaganda, sabotage, and subversion operations to include guerilla warfare. The military initially endorsed the decision, but the outbreak of the Korean War changed all this. For one thing, General Douglas MacArthur’s Far East Command (FEC) quickly recognized the need for developing these capabilities itself. The war had served as an abrupt reminder that their elimination had been premature and unwise.

Thousands of Koreans – we do not know the actual number – never returned from their suicidal missions behind enemy lines in North Korea during the Korean War.

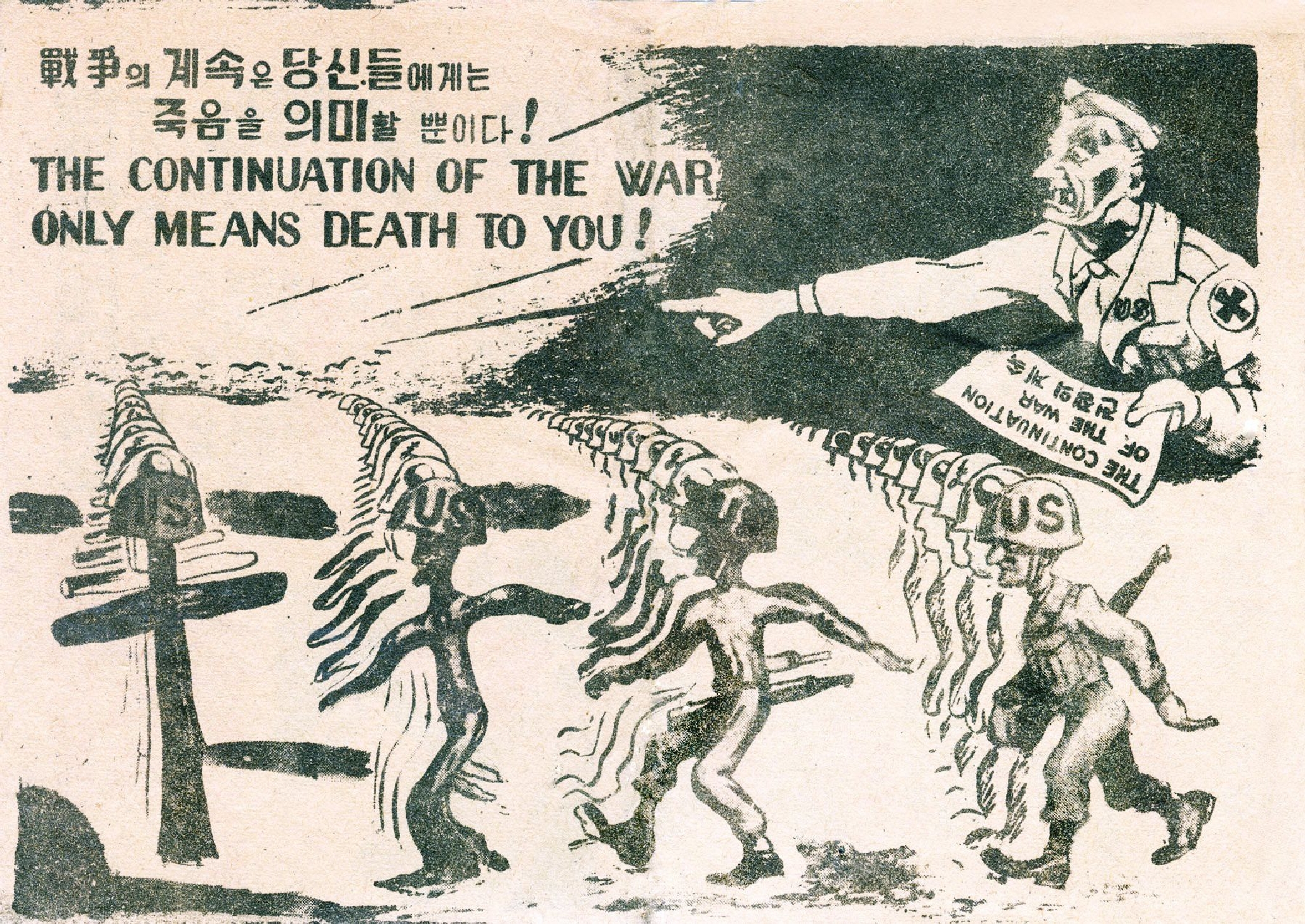

In June 1950, the military had minimal special operations capability, and the CIA, due to MacArthur’s personal animosity, only had a 3-person cell in Tokyo to cover all of East Asia. By January 1951, however, a multitude of ad-hoc organizations had sprung up under FEC, the Navy and Air Force components of FEC, Eighth U.S. Army in Korea (EUSAK), and the CIA, conducting covert intelligence collection, raids, sabotage, kidnapping, and guerilla operations as well as dropping millions of leaflets weekly and broadcasting around the clock over radio and loudspeakers.

Thousands of Korean agents and guerillas, recruited from anti-Communist North Korean refugees and led by Americans, were inserted into North Korea by land, air and sea. The operations continued and expanded as the war dragged on, exacting increasingly heavy casualties. This toll grew especially heavy after the frontlines had stabilized in the summer of 1951, and Communist forces tightened rear area security. Chinese and North Korean security was so effective that in the last two years of the war, nearly every parachute-inserted agent was killed or captured. By the time of the armistice in July 1953, thousands of Korean agents and guerillas had been sent into North Korea – and were never heard from again.

Aside from the danger, these operations suffered from deep systemic and structural dysfunction arising from competing interests and culture of the sponsoring organizations, as well as a lack of experience and expertise. The diffused organizations conducting operations could not get along and cooperate for the greater good. One attempt in late 1951 to bring a semblance of order to covert actions was badly botched and only worsened the strained relationships between competing interests. The result was duplication of effort and increased risk. It was not unusual to find an aircraft departing for North Korea with agents and guerillas from two or more units on uncoordinated missions.

Did special operations affect the course and outcome of the conflict? Tragically, most historians agree that the effort had only a marginal impact on the war. But something of long-term consequence did emerge from the adversity and dysfunction: a reconstitution of these capabilities.

A decade after the Korean War Armistice, covert operations and unconventional warfare became widely and deliberately utilized in the war in Vietnam. Special operations not only played a large role in that conflict but represented the initial U.S. response before conventional forces were even committed. Among these new post-Korean War capabilities included the creation of the Army Special Forces, the evolution of the Navy UDTs to become SEALs, and the refinement of CIA paramilitary capabilities. The continued evolution and expansion of special operations reached its pinnacle with the formation of the U.S. Special Operations Command in 1987 and its dominant role in the post-9/11 War on Terrorism.

The Korean War triggered a revival of U.S. special operations that has had a continuing and expanding legacy. The full story of the conflict’s special operations awaits the declassification and release of records, especially from the CIA and China. It is a story that will clarify the sacrifices of thousands of Koreans who vanished behind enemy lines and whose service to their country have only been recently recognized. It will also help us to appreciate the significance of the Korean War for understanding the unique history of Special Operations and its place within the broader field of U.S. military history.

Sheila Miyoshi Jager is Professor of East Asian Studies at Oberlin College. Her most recent book is Brothers at War: The Unending Conflict in Korea . She is finishing a new book project, The Other Great Game: The Opening of Korea and the Birth of Modern East Asia, 1876-1905 , which is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

Jiyul Kim is a retired U.S. Army officer with over 28 years of service. He is a Visiting Instructor of History at Oberlin College.

Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Jiyul Kim are collaborating on The Korean War: A New History, which is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

Open Question: Memorials – Remembering an Unfinished War?

Historians have not yet written the final chapter of the Korean War, even as memorials to the never-ended conflict rise across the American landscape.

Often referred to as the “Forgotten War,” the Korean conflict of 1950 through 1953 was sandwiched between World War II of the “Greatest Generation” and the long tragic nightmare of Vietnam. However, the Korean War has never been forgotten by historians.

In recent decades, an avalanche of significant new studies has provided a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the war’s origins, conduct, and consequences. As the war continues, halted only by an uneasy armistice that has lasted for nearly seventy years, studies of the Korean War proliferate. Their profusion has been made possible, in part, by access to greater international materials made available to scholars by the newly-opened archives and the declassification of government documents.

Meanwhile, manuscripts, memoirs and oral histories of participants in the conflict continue to surface. These new primary sources present historians with a further appreciation of the complex and continuing struggle for dominance on the Korean peninsula.

Public memory provides an additional area of exploration for the study of the Korean War, and examining how wars are remembered in popular culture, museums, memorials, and historic sites, has increasingly attracted the attention of the scholarly community. Both remembrance, as well as the need to acknowledge the costs and ravages of war, have become an essential element of a national psyche. And in recent years, our nation has experienced a memory boom, whether dealing with international warfare of the early 20th century or the fragmentation of warfare since 1945. In the United States, memorials now tend to be more inclusive of ethnic and racial minorities who fought in these wars, and the service of women in conflict. They also tend to focus on the soldiers who saw combat, instead of great generals, or leading political figures. Furthermore, it is the veterans of these wars and their families who have taken the lead in advocating for these memorials, as well as in funding and creating them.

War memorials can provide a means to examine the long and complex process of establishing a collective memory. The Korean War is a remarkable example of how a nation's public memory of an event can be formed and reshaped over several decades in the midst of ever-changing international dynamics. The American public memory of the Korean War has been influenced by the nation’s subsequent experience of the Vietnam War experience, and the establishment of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The dramatic improvement in the image of the Republic of Korea – as well as its rising world status following the success of the 1988 Seoul Olympics – has also played a role. The sudden end of the Cold War, and South Korea’s emergence as a democracy and prosperous “Asian Tiger,” have led to a feeling that the “police action” in Korea had been worthwhile.

Both remembrance, as well as the need to acknowledge the costs and ravages of war, have become an essential element of a national psyche.

Initially, the creation of the Korean War Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. presented a set of unusual challenges to those involved in its long and contentious planning process. When the project began in the late 1980s, the Korean conflict remained highly unpopular, and also had been largely forgotten by an American public still recovering from the traumas of the Vietnam conflict. Furthermore, the U.S.-led intervention in Korea had never even been declared formally as a war – and the conflict has never officially ended.

A fractious process finally led to the dedication of a striking and popular monument in July 1995. Yet many critics, including the influential Korean War Veterans Association, remain unsatisfied by it. They have demanded a wall of remembrance that lists the names of those killed or missing in the conflict, similar to that which comprises the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. And just like the war in Korea, the Korean War Veterans Memorial remains unfinished and, ironically, depends on funding from South Korean sources.

Even before the Korean War Veterans Memorial was dedicated in Washington D.C., communities across the nation were establishing memorials to commemorate the experiences and the sacrifices of those who fought in the conflict. And like the monument on the National Mall, these numerous and diverse endeavors tell us much about those who are compelled to memorialize the war.

One learns from these efforts that the Korean War is now clearly understood by the American public as victory for the United States, the United Nations, and the Republic of Korea. It is also clear that the American public now sees the Republic of Korea as worth the sacrifice made to save it from a communist takeover, and the Korean-American community in the United States is viewed with respect and appreciation. This feeling appears to be largely reciprocated by the Republic of Korea and the Korean-American community, both of which have significantly participated in the funding planning and dedicating of local memorials.

The Korean War may not yet have reached its end. But the writing of its history, as well as the process of its memorialization, has sought to establish the conflict’s place in the pantheon of American wars.

Michael J. Devine is an Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Wyoming. From 2001 until his retirement in 2014, he served as director of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library. He has twice been named a Senior Fulbright Lecturer to Korea (1995 and 2017-2018), and was the Houghton Freeman Professor of American History at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Graduate Center in 1998 and 1999. He is the author of John W. Foster: Politics and Diplomacy in the Imperial Era, 1877-1917 (1981), and the editor of Korea in War, Revolution and Peace: The Recollections of Horace G. Underwood (2001).

( Cover photograph: The UN flag waves over a crowd waiting to hear Syngman Rhee speak to the United Nations Council in Taegu, Korea on July 30, 1950. National Archives and Records Administration)

Up next in this issue

“May We Unfold the Radiant Fatherland!”

– Yee Rem Kim

How lost writings of North Korean soldiers challenge long-held notions of the war.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The korean war 101: causes, course, and conclusion of the conflict.

North Korea attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, igniting the Korean War. Cold War assumptions governed the immediate reaction of US leaders, who instantly concluded that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had ordered the invasion as the first step in his plan for world conquest. “Communism,” President Harry S. Truman argued later in his memoirs, “was acting in Korea just as [Adolf] Hitler, [Benito] Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.” If North Korea’s aggression went “unchallenged, the world was certain to be plunged into another world war.” This 1930s history lesson prevented Truman from recognizing that the origins of this conflict dated to at least the start of World War II, when Korea was a colony of Japan. Liberation in August 1945 led to division and a predictable war because the US and the Soviet Union would not allow the Korean people to decide their own future.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely indifferent to its fate.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely in- different to its fate. But after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors acknowledged at once the importance of this strategic peninsula for peace in Asia, advocating a postwar trusteeship to achieve Korea’s independence. Late in 1943, Roosevelt joined British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek in signing the Cairo Declaration, stating that the Allies “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” At the Yalta Conference in early 1945, Stalin endorsed a four-power trusteeship in Korea. When Harry S. Truman became president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, however, Soviet expansion in Eastern Europe had begun to alarm US leaders. An atomic attack on Japan, Truman thought, would preempt Soviet entry into the Pacific War and allow unilateral American occupation of Korea. His gamble failed. On August 8, Stalin declared war on Japan and sent the Red Army into Korea. Only Stalin’s acceptance of Truman’s eleventh-hour proposal to divide the peninsula into So- viet and American zones of military occupation at the thirty-eighth parallel saved Korea from unification under Communist rule.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary.

US military occupation of southern Korea began on September 8, 1945. With very little preparation, Washing- ton redeployed the XXIV Corps under the command of Lieutenant General John R. Hodge from Okinawa to Korea. US occupation officials, ignorant of Korea’s history and culture, quickly had trouble maintaining order because al- most all Koreans wanted immediate in- dependence. It did not help that they followed the Japanese model in establishing an authoritarian US military government. Also, American occupation officials relied on wealthy land- lords and businessmen who could speak English for advice. Many of these citizens were former Japanese collaborators and had little interest in ordinary Koreans’ reform demands. Meanwhile, Soviet military forces in northern Korea, after initial acts of rape, looting, and petty crime, implemented policies to win popular support. Working with local people’s committees and indigenous Communists, Soviet officials enacted sweeping political, social, and economic changes. They also expropriated and punished landlords and collaborators, who fled southward and added to rising distress in the US zone. Simultaneously, the Soviets ignored US requests to coordinate occupation policies and allow free traffic across the parallel.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary. This became clear when the US and the Soviet Union tried to implement a revived trusteeship plan after the Moscow Conference in December 1945. Eighteen months of intermittent bilateral negotiations in Korea failed to reach agreement on a representative group of Koreans to form a provisional government, primarily because Moscow refused to consult with anti-Communist politicians opposed to trustee- ship. Meanwhile, political instability and economic deterioration in southern Korea persisted, causing Hodge to urge withdrawal. Postwar US demobilization that brought steady reductions in defense spending fueled pressure for disengagement. In September 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) added weight to the withdrawal argument when they advised that Korea held no strategic significance. With Communist power growing in China, however, the Truman administration was unwilling to abandon southern Korea precipitously, fearing domestic criticism from Republicans and damage to US credibility abroad.

Seeking an answer to its dilemma, the US referred the Korean dispute to the United Nations, which passed a resolution late in 1947 calling for internationally supervised elections for a government to rule a united Korea. Truman and his advisors knew the Soviets would refuse to cooper- ate. Discarding all hope for early reunification, US policy by then had shifted to creating a separate South Korea, able to defend itself. Bowing to US pressure, the United Nations supervised and certified as valid obviously undemocratic elections in the south alone in May 1948, which resulted in formation of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in August. The Soviet Union responded in kind, sponsoring the creation of the Democratic People’s Re- public of Korea (DPRK) in September. There now were two Koreas, with President Syngman Rhee installing a repressive, dictatorial, and anti-Communist regime in the south, while wartime guerrilla leader Kim Il Sung imposed the totalitarian Stalinist model for political, economic, and social development on the north. A UN resolution then called for Soviet-American withdrawal. In December 1948, the Soviet Union, in response to the DPRK’s request, removed its forces from North Korea.

South Korea’s new government immediately faced violent opposition, climaxing in October 1948 with the Yosu-Sunchon Rebellion. Despite plans to leave the south by the end of 1948, Truman delayed military withdrawal until June 29, 1949. By then, he had approved National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, undertaking a commitment to train, equip, and supply an ROK security force capable of maintaining internal order and deterring a DPRK attack. In spring 1949, US military advisors supervised a dramatic improvement in ROK army fighting abilities. They were so successful that militant South Korean officers began to initiate assaults northward across the thirty-eighth parallel that summer. These attacks ignited major border clashes with North Korean forces. A kind of war was already underway on the peninsula when the conventional phase of Korea’s conflict began on June 25, 1950. Fears that Rhee might initiate an offensive to achieve reunification explain why the Truman administration limited ROK military capabilities, withholding tanks, heavy artillery, and warplanes.

Pursuing qualified containment in Korea, Truman asked Congress for three-year funding of economic aid to the ROK in June 1949. To build sup- port for its approval, on January 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean G. Ache- son’s speech to the National Press Club depicted an optimistic future for South Korea. Six months later, critics charged that his exclusion of the ROK from the US “defensive perimeter” gave the Communists a “green light” to launch an invasion. However, Soviet documents have established that Acheson’s words had almost no impact on Communist invasion planning. Moreover, by June 1950, the US policy of containment in Korea through economic means appeared to be experiencing marked success. The ROK had acted vigorously to control spiraling inflation, and Rhee’s opponents won legislative control in May elections. As important, the ROK army virtually eliminated guerrilla activities, threatening internal order in South Korea, causing the Truman administration to propose a sizeable military aid increase. Now optimistic about the ROK’s prospects for survival, Washington wanted to deter a conventional attack from the north.

Stalin worried about South Korea’s threat to North Korea’s survival. Throughout 1949, he consistently refused to approve Kim Il Sung’s persistent requests to authorize an attack on the ROK. Communist victory in China in fall 1949 pressured Stalin to show his support for a similar Korean outcome. In January 1950, he and Kim discussed plans for an invasion in Moscow, but the Soviet dictator was not ready to give final consent. How- ever, he did authorize a major expansion of the DPRK’s military capabilities. At an April meeting, Kim Il Sung persuaded Stalin that a military victory would be quick and easy because of southern guerilla support and an anticipated popular uprising against Rhee’s regime. Still fearing US military intervention, Stalin informed Kim that he could invade only if Mao Zedong approved. During May, Kim Il Sung went to Beijing to gain the consent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Significantly, Mao also voiced concern that the Americans would defend the ROK but gave his reluctant approval as well. Kim Il Sung’s patrons had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On the morning of June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched its military offensive to conquer South Korea. Rather than immediately committing ground troops, Truman’s first action was to approve referral of the matter to the UN Security Council because he hoped the ROK military could defend itself with primarily indirect US assistance. The UN Security Council’s first resolution called on North Korea to accept a cease- fire and withdraw, but the KPA continued its advance. On June 27, a second resolution requested that member nations provide support for the ROK’s defense. Two days later, Truman, still optimistic that a total commitment was avoidable, agreed in a press conference with a newsman’s description of the conflict as a “police action.” His actions reflected an existing policy that sought to block Communist expansion in Asia without using US military power, thereby avoiding increases in defense spending. But early on June 30, he reluctantly sent US ground troops to Korea after General Douglas MacArthur, US Occupation commander in Japan, advised that failure to do so meant certain Communist destruction of the ROK.

Kim Il Sung’s patrons [Stalin and Mao] had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On July 7, 1950, the UN Security Council created the United Nations Command (UNC) and called on Truman to appoint a UNC commander. The president immediately named MacArthur, who was required to submit periodic reports to the United Nations on war developments. The ad- ministration blocked formation of a UN committee that would have direct access to the UNC commander, instead adopting a procedure whereby MacArthur received instructions from and reported to the JCS. Fifteen members joined the US in defending the ROK, but 90 percent of forces were South Korean and American with the US providing weapons, equipment, and logistical support. Despite these American commitments, UNC forces initially suffered a string of defeats. By July 20, the KPA shattered five US battalions as it advanced one hundred miles south of Seoul, the ROK capital. Soon, UNC forces finally stopped the KPA at the Pusan Perimeter, a rectangular area in the southeast corner of the peninsula.

On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea

Despite the UNC’s desperate situation during July, MacArthur developed plans for a counteroffensive in coordination with an amphibious landing behind enemy lines allowing him to “compose and unite” Korea. State Department officials began to lobby for forcible reunification once the UNC assumed the offensive, arguing that the US should destroy the KPA and hold free elections for a government to rule a united Korea. The JCS had grave doubts about the wisdom of landing at the port of Inchon, twenty miles west of Seoul, because of narrow access, high tides, and sea- walls, but the September 15 operation was a spectacular success. It allowed the US Eighth Army to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and advance north to unite with the X Corps, liberating Seoul two weeks later and sending the KPA scurrying back into North Korea. A month earlier, the administration had abandoned its initial war aim of merely restoring the status quo. On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea.

Invading the DPRK was an incredible blunder that transformed a three-month war into one lasting three years. US leaders had realized that extension of hostilities risked Soviet or Chinese entry, and therefore, NSC- 81 included the precaution that only Korean units would move into the most northern provinces. On October 2, PRC Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai warned the Indian ambassador that China would intervene in Korea if US forces crossed the parallel, but US officials thought he was bluffing. The UNC offensive began on October 7, after UN passage of a resolution authorizing MacArthur to “ensure conditions of stability throughout Korea.” At a meeting at Wake Island on October 15, MacArthur assured Truman that China would not enter the war, but Mao already had decided to intervene after concluding that Beijing could not tolerate US challenges to its regional credibility. He also wanted to repay the DPRK for sending thou- sands of soldiers to fight in the Chinese civil war. On August 5, Mao instructed his northeastern military district commander to prepare for operations in Korea in the first ten days of September. China’s dictator then muted those associates opposing intervention.

On October 19, units of the Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) under the command of General Peng Dehuai crossed the Yalu River. Five days later, MacArthur ordered an offensive to China’s border with US forces in the vanguard. When the JCS questioned this violation of NSC-81, MacArthur replied that he had discussed this action with Truman on Wake Island. Having been wrong in doubting Inchon, the JCS remained silent this time. Nor did MacArthur’s superiors object when he chose to retain a divided command. Even after the first clash between UNC and CPV troops on October 26, the general remained supremely confident. One week later, the Chinese sharply attacked advancing UNC and ROK forces. In response, MacArthur ordered air strikes on Yalu bridges without seeking Washing- ton’s approval. Upon learning this, the JCS prohibited the assaults, pending Truman’s approval. MacArthur then asked that US pilots receive permission for “hot pursuit” of enemy aircraft fleeing into Manchuria. He was infuriated upon learning that the British were advancing a UN proposal to halt the UNC offensive well short of the Yalu to avert war with China, viewing the measure as appeasement.

On November 24, MacArthur launched his “Home-by-Christmas Offensive.” The next day, the CPV counterattacked en masse, sending UNC forces into a chaotic retreat southward and causing the Truman administration immediately to consider pursuing a Korean cease-fire. In several public pronouncements, MacArthur blamed setbacks not on himself but on unwise command limitations. In response, Truman approved a directive to US officials that State Department approval was required for any comments about the war. Later that month, MacArthur submitted a four- step “Plan for Victory” to defeat the Communists—a naval blockade of China’s coast, authorization to bombard military installations in Manchuria, deployment of Chiang Kai-shek Nationalist forces in Korea, and launching of an attack on mainland China from Taiwan. The JCS, despite later denials, considered implementing these actions before receiving favorable battlefield reports.

Early in 1951, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, new commander of the US Eighth Army, halted the Communist southern advance. Soon, UNC counterattacks restored battle lines north of the thirty-eighth parallel. In March, MacArthur, frustrated by Washington’s refusal to escalate the war, issued a demand for immediate surrender to the Communists that sabotaged a planned cease-fire initiative. Truman reprimanded but did not recall the general. On April 5, House Republican Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr. read MacArthur’s letter in Congress, once again criticizing the administration’s efforts to limit the war. Truman later argued that this was the “last straw.” On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the president fired MacArthur, justifying his action as a defense of the constitutional principle of civilian control over the military, but another consideration may have exerted even greater influence on Truman. The JCS had been monitoring a Communist military buildup in East Asia and thought a trusted UNC commander should have standing authority to retaliate against Soviet or Chinese escalation, including the use of nuclear weapons that they had deployed to forward Pacific bases. Truman and his advisors, as well as US allies, distrusted MacArthur, fearing that he might provoke an incident to widen the war.

MacArthur’s recall ignited a firestorm of public criticism against both Truman and the war. The general returned to tickertape parades and, on April 19, 1951, he delivered a televised address before a joint session of Congress, defending his actions and making this now-famous assertion: “In war there is no substitute for victory.” During Senate joint committee hearings on his firing in May, MacArthur denied that he was guilty of in- subordination. General Omar N. Bradley, the JCS chair, made the administration’s case, arguing that enacting MacArthur’s proposals would lead to “the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.” Meanwhile, in April, the Communists launched the first of two major offensives in a final effort to force the UNC off the peninsula. When May ended, the CPV and KPA had suffered huge losses, and a UNC counteroffensive then restored the front north of the parallel, persuading Beijing and Pyongyang, as was already the case in Washington, that pursuit of a cease-fire was necessary. The belligerents agreed to open truce negotiations on July 10 at Kaesong, a neutral site that the Communists deceitfully occupied on the eve of the first session.

North Korea and China created an acrimonious atmosphere with at- tempts at the outset to score propaganda points, but the UNC raised the first major roadblock with its proposal for a demilitarized zone extending deep into North Korea. More important, after the talks moved to Panmunjom in October, there was rapid progress in resolving almost all is- sues, including establishment of a demilitarized zone along the battle lines, truce enforcement inspection procedures, and a postwar political conference to discuss withdrawal of foreign troops and reunification. An armistice could have been concluded ten months after talks began had the negotiators not deadlocked over the disposition of prisoners of war (POWs). Rejecting the UNC proposal for non-forcible repatriation, the Communists demanded adherence to the Geneva Convention that required return of all POWs. Beijing and Pyongyang were guilty of hypocrisy regarding this matter because they were subjecting UNC prisoners to unspeakable mistreatment and indoctrination.

On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the presi- dent fired MacArthur.

Truman ordered that the UNC delegation assume an inflexible stand against returning Communist prisoners to China and North Korea against their will. “We will not buy an armistice,” he insisted, “by turning over human beings for slaughter or slavery.” Although Truman unquestionably believed in the moral rightness of his position, he was not unaware of the propaganda value derived from Communist prisoners defecting to the “free world.” His advisors, however, withheld evidence from him that contradicted this assessment. A vast majority of North Korean POWs were actually South Koreans who either joined voluntarily or were impressed into the KPA. Thousands of Chinese POWs were Nationalist soldiers trapped in China at the end of the civil war, who now had the chance to escape to Taiwan. Chinese Nationalist guards at UNC POW camps used terrorist “re-education” tactics to compel prisoners to refuse repatriation; resisters risked beatings or death, and repatriates were even tattooed with anti- Communist slogans.

In November 1952, angry Americans elected Dwight D. Eisenhower president, in large part because they expected him to end what had be- come the very unpopular “Mr. Truman’s War.” Fulfilling a campaign pledge, the former general visited Korea early in December, concluding that further ground attacks would be futile. Simultaneously, the UN General Assembly called for a neutral commission to resolve the dispute over POW repatriation. Instead of embracing the plan, Eisenhower, after taking office in January 1953, seriously considered threatening a nuclear attack on China to force a settlement. Signaling his new resolve, Eisenhower announced on February 2 that he was ordering removal of the US Seventh Fleet from the Taiwan Strait, implying endorsement for a Nationalist assault on the mainland. What influenced China more was the devastating impact of the war. By summer 1952, the PRC faced huge domestic economic problems and likely decided to make peace once Truman left office. Major food shortages and physical devastation persuaded Pyongyang to favor an armistice even earlier.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953.

Early in 1953, China and North Korea were prepared to resume the truce negotiations, but the Communists preferred that the Americans make the first move. That came on February 22 when the UNC, repeating a Red Cross proposal, suggested exchanging sick and wounded prisoners. At this key moment, Stalin died on March 5. Rather than dissuading the PRC and the DPRK as Stalin had done, his successors encouraged them to act on their desire for peace. On March 28, the Communist side accepted the UNC proposal. Two days later, Zhou Enlai publicly proposed transfer of prisoners rejecting repatriation to a neutral state. On April 20, Operation Little Switch, the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, began, and six days later, negotiations resumed at Panmunjom. Sharp disagreement followed over the final details of the truce agreement. Eisenhower insisted later that the PRC accepted US terms after Secretary of State John Foster Dulles informed India’s prime minister in May that without progress toward a truce, the US would terminate the existing limitations on its conduct of the war. No documentary evidence has of yet surfaced to support his assertion.

Also, by early 1953, both Washington and Beijing clearly wanted an armistice, having tired of the economic burdens, military losses, political and military constraints, worries about an expanded war, and pressure from allies and the world community to end the stalemated conflict. A steady stream of wartime issues threatened to inflict irrevocable damage on US relations with its allies in Western Europe and nonaligned members of the United Nations. Indeed, in May 1953, US bombing of North Korea’s dams and irrigation system ignited an outburst of world criticism. Later that month and early in June, the CPV staged powerful attacks against ROK defensive positions. Far from being intimidated, Beijing thus displayed its continuing resolve, using military means to persuade its adversary to make concessions on the final terms. Before the belligerents could sign the agreement, Rhee tried to torpedo the impending truce when he released 27,000 North Korean POWs. Eisenhower bought Rhee’s acceptance of a cease-fire with pledges of financial aid and a mutual security pact.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953. Since then, Koreans have seen the war as the second-greatest tragedy in their recent history after Japanese colonial rule. Not only did it cause devastation and three million deaths, it also confirmed the division of a homogeneous society after thirteen centuries of unity, while permanently separating millions of families. Meanwhile, US wartime spending jump-started Japan’s economy, which led to its emergence as a global power. Koreans instead had to endure the living tragedy of yearning for reunification, as diplomatic tension and military clashes along the demilitarized zone continued into the twenty-first century.

Korea’s war also dramatically reshaped world affairs. In response, US leaders vastly increased defense spending, strengthened the North Atlantic Treaty Organization militarily, and pressed for rearming West Germany. In Asia, the conflict saved Chiang’s regime on Taiwan, while making South Korea a long-term client of the US. US relations with China were poisoned for twenty years, especially after Washington persuaded the United Nations to condemn the PRC for aggression in Korea. Ironically, the war helped Mao’s regime consolidate its control in China, while elevating its regional prestige. In response, US leaders, acting on what they saw as Korea’s primary lesson, relied on military means to meet the challenge, with disastrous results in Việt Nam.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

SUGGESTED RESOURCES

Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict . Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999.

“Korea: Lessons of the Forgotten War.” YouTube video, 2:20, posted by KRT Productions Inc., 2000. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fi31OoQfD7U.

Lee, Steven Hugh. The Korean War. New York: Longman, 2001.

Matray, James I. “Korea’s War at Sixty: A Survey of the Literature.” Cold War History 11, no. 1 (February 2011): 99–129.

US Department of Defense. Korea 1950–1953, accessed July 9, 2012, http://koreanwar.defense.gov/index.html.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Throughout May, AAS is celebrating Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Read more

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Lesson Plan: The Korean War

The Beginning of the Korean War

Description

On June 25, 1950, North Korea surprised South Korea by invading and advancing towards the capital city of Seoul. Soon after, President Truman sent U.S. troops to aid the South Korean military, and a U.N. Security Council resolution was pushed through to send additional troops and aid to bolster existing South Korean and U.S. forces. An armistice was signed in July 1953, ending the active fighting of the war and creating a demilitarized zone separating the two countries, although a peace treaty has never been signed. In this lesson, students will learn about the causes, significance, and legacy of the Korean War.

INTRODUCTION

As a class, view the following video clip and then discuss the questions below.

Video Clip: The Beginning of the Korean War (6:14)

Explain the circumstances in Korea between 1945 and 1950 that led to the Korean War.

Why did North Korea want to invade South Korea, beginning in 1948? What dissuaded them from invading at that time? What emboldened them to invade in 1950?

How did the Truman administration view the invasion? What steps did the administration take?

- Explain the decision of the United Nations Security Council. According to Mr. Brazinsky, what was the view and reaction of the U.S. Congress in relation to President Truman and our involvement in Korea?

Break students into groups and have each group view the following video clips. Students should take notes using the handout provided, and then share their findings with the rest of the class.

HANDOUT: Korean War Handout (Google Doc)

Video Clip: North Korea Invades South Korea (1:39)

The U.S. Army "Big Picture" episode shows footage of the North Korea invasion and the United Nations response.

Video Clip: President Truman Korean War Address (0:51)

President Truman addressed the nation on why the U.S. must intervene in the Korean War.

Video Clip: The Countries Involved in the Korean War (2:19)

Christopher Kolakowski described the role of the United Nations and the countries involved in the Korean War.

Video Clip: Korean War Military Action (3:52)

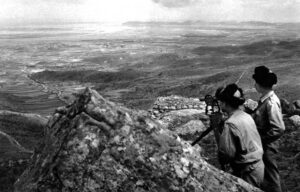

Professor Lisa Brady gives an overview of the military strategy and progress during the Korean War.

Video Clip: Gen. Douglas MacArthur's Role in the Korean War (2:32)

GWU History Professor Gregg Brazinsky discusses Gen. Douglas MacArthur's role in leading U.S. forces during the Korean War, and his interactions with President Truman and his administration.

Video Clip: China's Involvement in the Korean War (1:43)

GWU History Professor Gregg Brazinsky on China's involvement in the Korean War, including their concerns over America's involvement in the war.

Video Clip: The Armistice and Legacy of the Korean War (2:16)

Christopher Kolakowski described the armistice to end the fighting of the Korean War and its signficance today.

TAKE A STAND

After discussing the findings from the video clips with the entire class, have the students take part in a "Take a Stand" activity with the following question.

"The United States made the correct decision in entering the Korean War"

Have students line up on a continuum based on their opinion from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” Ask several students from different points on the line to share their reasoning and defend their position.

After completing the "Take a Stand" activity, have students write an essay (or similar culminating activity) that includes the following information. Students should cite specific examples from the videos and class discussion.

The causes of the Korean War and the involvement of the United States and United Nations

Major military actions and the role of General MacArthur

The significance of the armistice then and today

- The impact of the Korean War in the context of the greater Cold War

Additional Resources

- ON THIS DAY: Korean War

- BELL RINGER: Korean War

- 38th Parallel

- Demilitarized Zone

- General Douglas Macarthur

- North Korea

- South Korea

- United Nations

The Korean War

- The Korean War /

- Discussion & Essay Questions

Cite This Source

Available to teachers only as part of the teaching the korean warteacher pass, teaching the korean war teacher pass includes:.

- Assignments & Activities

- Reading Quizzes

- Current Events & Pop Culture articles

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Related Readings in Literature & History

Sample of Discussion & Essay Questions

big picture.

- Why did China send troops into Korea?

- Ideological

- Would China have reason to feel threatened by MacArthur's advance?

Tired of ads?

Logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

Home — Essay Samples — War — Korean War

Essays on Korean War

Korean war essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: the korean war (1950-1953): uncovering the origins, cold war context, and global implications.

Thesis Statement: This essay delves into the complex origins of the Korean War, the Cold War context that fueled the conflict, and the far-reaching global implications of the war, including its impact on international alliances and the division of Korea.

- Introduction

- Background and Historical Context: Pre-war Korea and Its Division

- The Cold War Setting: U.S.-Soviet Rivalry and Proxy Wars

- The Outbreak of War: North Korea's Invasion and International Response

- The Course of the Conflict: Battles, Truce Talks, and Stalemate

- Global Implications: The Korean War's Impact on East Asia and International Relations

- Legacy and Repercussions: The Division of Korea and Ongoing Tensions

Essay Title 2: The Korean War's Forgotten Heroes: Examining the Role of United Nations Forces and the Armistice Agreement

Thesis Statement: This essay focuses on the often-overlooked contributions of United Nations forces in the Korean War, the complexities of the Armistice Agreement, and the enduring impact of the war on Korean society and international peacekeeping efforts.

- The United Nations Coalition: Multinational Forces in Korea

- The Armistice Negotiations: Challenges, Agreements, and Ongoing Tensions

- Forgotten Heroes: Stories of Courage and Sacrifice

- Korean War Veterans: Their Post-War Experiences and Commemoration

- Peacekeeping and Reconciliation Efforts: The Role of the United Nations

- Implications for Modern International Conflict Resolution

Essay Title 3: The Korean War and the Origins of the Cold War: Analyzing the Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations and Global Alliances

Thesis Statement: This essay explores how the Korean War influenced U.S.-Soviet relations, the formation of military alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the Cold War's evolution into a global struggle for influence.

- The Korean War as a Catalyst: Escalation of Cold War Tensions

- Military Alliances: NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and the Globalization of the Cold War

- The U.S.-Soviet Confrontation: Proxy Warfare and Diplomatic Efforts

- International Response and Support for North and South Korea

- The Aftermath of the Korean War: Paving the Way for Future Cold War Conflicts

- Assessing the Korean War's Long-Term Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations

The Korean War – a Conflict Between The Soviet Union and The United States

The local and global effects of the korean war, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Role of The Korean War in History

The origin of the korean conflict, the role of the battle of chipyong-ni in the korean war, the korean war and its impact on lawrence werner, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Historical Accuracy of The Book Korean War by Maurice Isserman

Solutions for disputes and disloyalty, depiction of the end of the korean war in the film the front line, the impact of war on korea.

25 June, 1950 - 27 July, 1953

Korean Peninsula, Yellow Sea, Sea of Japan, Korea Strait, China–North Korea border.

China, North Korea, South Korea, United Nations, United States

Korean War was a conflict between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) in which at least 2.5 million persons lost their lives. The war reached international proportions in June 1950 when North Korea, supplied and advised by the Soviet Union, invaded the South.

North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; US-led United Nations invasion of North Korea repelled; Chinese and North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953; Korean conflict ongoing.

Relevant topics

- Vietnam War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- Syrian Civil War

- Nuclear Weapon

- The Spanish American War

- Atomic Bomb

- Treaty of Versailles

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IB History: ActiveHistory

An activehistory subscription provides everything you need to construct and deliver a two-year ibdp history course from start to finish using the activehistory ib history hub ..

These consist not just of lesson plans, worksheets and teacher notes, but also multimedia lectures and interactive games and historical simulations ideal for remote learning and self-study.

Use the ActiveHistory curriculum maps and the ActiveHistory syllabus topics to design your own course effectively.

We also have you covered for the Internal Assessment , Extended Essay and Theory of Knowledge in History , not to mention Essay and Sourcework Skills , IBDP History Model Essays and IBDP History Sample Sourcework Exercises / Model answers !

SUBSCRIBE NOW REQUEST A FREE TRIAL