- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

The Close Relationship Between Art and Architecture in Modernism

- Written by Camilla Ghisleni | Translated by Tarsila Duduch

- Published on July 21, 2023

The idea of integration between art and architecture dates back to the very origin of the discipline, however, it took on a new meaning and social purpose during the Avant-Garde movement of the early twentieth century, becoming one of the most defining characteristics of Modernism . This close relationship is evident in the works of some of the greatest modern architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Oscar Niemeyer, to name a few.

Needless to say, modernism emerged from an expectation of moral and material reconstruction of a world devastated by war, serving as a tool to strengthen a collective identity and, consequently, the bond between the city and its inhabitants. In this context, artistic expression is used as a tool to shape the emotional life of the user, to which art and architecture combined can give a new meaning, offering a place that represents a sense of community, in addition to function and technique.

The professional development at Bauhaus was marked by what Argan (1992) calls "methodological-didactic rationalism," encouraging the unification of all the arts through a Gesamtkunstwerk , which roughly translates as a "total work of art," incorporating architecture, painting, sculpture, industrial design, and crafts. This collaboration was expected to happen even on the building site, thus bringing together intellectual and manual work in a shared experience. As their leading exponent Walter Gropius used to say, an architect should be as familiar with painting as a painter should be with architecture. One should not design a building and commission a sculptor afterward; this would be wrong and detrimental to the architectural unity.

Apart from the Bauhaus program, this integration between disciplines was also, and most notably, brought up by Le Corbusier through the combination of elements from painting and sculpture with the formal concepts of architecture. In this sense, Le Corbusier - despite being a "one-man show" who preached the synthesis of the arts in his designs, but always worked as a solo artist - argued that the roles of architects, painters, and sculptors were of equal importance contributing to productive collaborations in the real world, that is, on the building site, by creating and designing in complete harmony.

To some extent, this inseparable relationship sounded so utopian that Lucio Costa stated that this greater art would require a level of cultural and aesthetical evolution that was almost impossible to achieve, in which architecture, sculpture, and painting would form one cohesive body, a living organism that could not be disintegrated. Nevertheless, the Capanema Palace in Rio de Janeiro is arguably the closest one could get to this utopia in Brazil by relying on painter Candido Portinari, sculptor Bruno Giorgi and landscape architect Burle Marx from the very beginning of the project development. As French historian Yves Bruand states, the result is an ensemble of great artistic value, brilliantly enhancing and complementing architecture, but subordinated to it at the same time.

While his works turned out to be prime examples of the fusion of architecture and art, Oscar Niemeyer also shared Costa's opinion that only in extraordinary circumstances could a true synthesis of the arts be achieved. He also stressed the crucial need to establish a team that would work together from the very beginning of the architectural sketches to amicably discuss the problems and smallest details of the project, without dividing them into specialized fields but considering them as a single balanced entity.

The ideal goal is to integrate all disciplines from the beginning of the project, but inviting artists to participate later in the design process does not necessarily compromise the final result. A good example is the Salão Negro (Black Room) at the National Congress in Brasília, where artist Athos Bulcão, invited by Niemeyer after the project was finished, created an abstract and simple language using black granite on the floor and white marble on the walls, which resulted in a mural fully integrated with the architecture and building materials. This mural with abstract patterns is often cited by academics, including Paul Damaz when he states that non-figurative language is the best match for modern architecture. In this regard, the author also mentions Maria Martins' semi-figurative bronze sculpture in the gardens of the Palácio da Alvorada , highlighting the "formal affinity between the curves" of the sculpture and the "graceful pillars of the building," as a perfect example of integration.

However, while Damaz praises the integration between architecture and art in Oscar Niemeyer's projects, he rejects one of the most important examples of integration between disciplines in the history of modernism, which is Mexico City's UNAM Campus . This complex is one of the most emblematic architectural achievements in Mexico, a country considered to be a pioneer in the incorporation of art into architecture, as seen in their tradition of mural painting since the 1920s. Inaugurated in 1952, parallel to the CIAM VIII, the University Campus was designed by more than 100 architects, as well as engineers, artists, and landscape designers. Some of the most remarkable artworks featured in the project are the murals by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Juan O'Gorman, and Francisco Eppens, which were criticized by the author for being figurative, creating a disparity in style between social realism and functionalist architecture, to the detriment of the latter. Nevertheless, despite the critiques, one cannot ignore the fact that UNAM is an open-air art museum and an example of cooperation and collectivity.

On a different scale but equally important, is integration between art and architecture through the inclusion of occasional individual elements such as the iconic Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe. Indeed, the sculpture Der Morgen , also known as Alba, by German sculptor Georg Kolbe (1877-1947) is not essential to the pavilion. But what else is essential in this new architectural concept, if not only the arrangement of planes and vertical supports? The pavilion is completely independent of the sculpture, as well as of the materials however, one cannot picture it today without this human figure with arms outstretched precisely positioned and framed for the user's experience. As Claudia Cabral beautifully explains, "in Mies' delicate balance, guided by partial asymmetries, and by a system of compensations, the sculpture is the only element that has no counterpart [...] Mies decided to place only one sculpture, a single figurative element in his abstract plane. Within the pavillions play with reflections, transparency, and parallels, we are the only possible partners for the bronze figure, we humans of flesh and blood, the visitors."

.jpg?1620863172)

Every form of integration of different disciplines consists of a coherent dialogue between architects, painters, and sculptors, whether from the very beginning of the project development or later on, during construction, whether on a large scale or with individual elements. Having this in mind, it is very alarming to witness events such as the relocation of the panels by artist Athos Bulcão in the Planalto Palace in Brasilia in 2009 due to a renovation. Even the Athos Bulcão Foundation - Fundathos opposed it since the original location was defined by Athos himself, along with Niemeyer while he was designing the palace in 1950.

As Rino Levi once said, architecture is not secondary, but neither is it the mother of all arts. There is only one art and its value is measured by the emotions it triggers in us. Painting and sculpture can be independent, however, when applied to architecture, they become part of a whole. This lesson on collectivity and shared experiences starts during project development and touches every single person who has the opportunity to visit the architectural work.

Reference List ARGAN, Giulio Carlo. Arte Moderna [Modern art]. São Paulo: Cia das Letras, 1992. BRUAND, Yves. Arquitetura contemporânea no Brasil. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2010. CABRAL, Cláudia Costa. Arte e arquitetura moderna em três projetos de Oscar Niemeyer [Art and modern architecture in three projects by Oscar Niemeyer]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Salvador, 2019. CABRAL, Cláudia Costa. Arquitetura moderna e escultura figurativa: a representação naturalista no espaço moderno [Modern architecture and figurative sculpture: naturalist representation in modern spaces]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 2009. DAMAZ, Paul. Art in Latin American Architecture. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963. DIÓGENES, Beatriz Helena Nogueira ; PAIVA, Ricardo Alexandre. Diálogo entre arte e arquitetura no modernismo em Fortaleza [Dialogue between art and architecture of modernism in Fortaleza]. DOCOMOMO Brasil, Recife, 2016. TAVARES, Camila Christiana de Aragão. A integração da arte e da arquitetura em Brasília: Lucio Costa e Athos Bulcão [The integration of art and architecture in Brasília: Lucio Costa and Athos Bulcão]. Dissertação de mestrado [Master's Thesis] UNB, Brasília.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Collective Design . Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our monthly topics . As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us .

Editor's Note: This article was originally published on June 01, 2021.

Image gallery

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Free Site Analysis Checklist

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!

Architecture Essays 101: How to be an effective writer

- Updated: October 25, 2023

The world of architecture stands at a fascinating crossroads of creativity and academia. As architects cultivate ideas to shape the physical world around us, we are also tasked with articulating these concepts through words.

Architecture essays, thus, serves as a bridge between the visual and the textual, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of architectural ideas and their implications.

The ability to articulate thoughts, analyses, and observations on design and theory is as crucial as creating the designs themselves. An architectural essay is not just about presenting information but about conveying an understanding of spaces, structures, and the stories they tell.

Whether you’re delving into the nuances of a specific architectural movement , analyzing the design of a historic monument, or predicting the future of sustainable design, the written word becomes a powerful tool to express intricate ideas.

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for crafting insightful architectural essays, ensuring that your perspectives on this multifaceted discipline are communicated effectively and engagingly.

Understanding the Unique Nature of Architecture Essay s

Architecture sits on a unique line between the aesthetic and the analytical, where designs are appreciated not only for their aesthetic appeal but also for their functionality and historical relevance.

An architecture essay isn’t just a manifestation of this intricate blend; it’s a testament to it. Aspiring architects or students of architecture must grasp the singular characteristics of this type of essay to truly succeed.

Embracing Creativity

When one imagines essays, the mind typically conjures up dense blocks of text. However, an architecture essay allows, and even demands, a flair of creativity.

Visual representations, be it in the form of diagrams , sketches , or photographs , aren’t just supplementary; they can form the core of your argument.

For instance, if you’re discussing the evolution of skyscraper designs , a chronological array of sketches can provide an insightful, immediate overview that words might struggle to convey.

Recognizing and capitalizing on this visual component can elevate the impact of your essay.

Theoretical Foundations

Yet, relying solely on creative illustrations won’t suffice. The foundation of every solid architecture essay is a strong understanding of architectural theories, principles , and historical contexts. Whether you’re analyzing the gothic cathedrals of Europe or the minimalist homes of Japan, delving deep into the why and how of their designs is crucial.

How did the social, economic, and technological conditions of the time influence these structures?

…How do they compare with contemporary designs?

Theoretical exploration provides depth to your essay, grounding your observations and opinions in recognized knowledge and pre-existing debates.

Furthermore, case studies play an essential role in these essays.

Instead of making sweeping statements, anchor your points in specific examples. Discussing the sustainability features of a particular building or the ergonomic design of another offers tangible evidence to support your arguments.

Blending the Two

The magic of an architecture essay lies in seamlessly weaving the creative with the theoretical.

While you showcase a building’s design through visuals, delve into its history, purpose, and societal implications with your words. This blend not only offers a holistic understanding of architectural marvels but also caters to a broad audience, ensuring your essay is both engaging and enlightening.

In conclusion, understanding the unique blend of design elements and theoretical discussion in an architecture essay sets the foundation for an impactful piece.

It’s about striking a balance between showing and telling, between the artist’s sketches and the academic’s observations. With this understanding, you’re better equipped to venture into the exciting world of architectural essay writing.

Choosing the Right Topic

Architectural essays stand apart in their blend of technical knowledge, aesthetic sense, and historical context. The topic you choose not only sets the tone for your essay but can also significantly affect the enthusiasm and rigor with which you approach the writing.

Here’s a comprehensive guide to selecting the right topic for your architecture essay:

Find your Golden Nugget:

- Personal Resonance: Your topic should excite you. Think about the architectural designs, movements, or theories that have made an impact on you. Perhaps it’s a specific building you’ve always admired or an architectural trend you’ve noticed emerging in your city.

- Uncharted Territory: Exploring less-known or under-discussed areas can give you a unique perspective and make your essay stand out. Instead of writing another essay on Roman architecture, consider focusing on the influence of Roman architecture on contemporary design or even on a specific region.

Researching Broadly:

- Diversify Your Sources: From books and academic journals to documentaries and interviews, use varied materials to spark ideas. Often, an unrelated article can lead to a unique essay topic.

- Current Trends and Issues: Look at contemporary architecture magazines , websites , and blogs to gauge what’s relevant and debated in today’s architectural world. It might inspire you to contribute to the discussion or even challenge some prevailing ideas.

Connecting with Design Projects:

- Personal Projects: If you’ve been involved in a design project, whether at school or professionally, consider exploring themes or challenges you encountered. This adds personal anecdotes and insights which enrich the essay.

- Case Studies: Instead of going broad, consider going deep. Dive into a single building or architect’s work. Analyzing one subject in-depth can offer nuanced perspectives and help demonstrate your analytical skills.

Feasibility of Research:

- Availability of Resources: While choosing an obscure topic can make your essay unique, ensure you have enough resources or primary research opportunities to support your arguments.

- Scope: The topic should be neither too broad nor too narrow. It should allow for in-depth exploration within the word limit of the essay. For instance, “Modern Architecture” is too broad, but “The Influence of Bauhaus on Modern Apartment Design in Berlin between 1950-1970” is more focused.

Finding the right topic is a journey, and sometimes it requires a few wrong turns before you hit the right path. Stay curious, be patient, and remember that the best topics are those that marry your personal passion with academic rigor. Your enthusiasm will shine through in your writing, making the essay engaging and impactful.

Organizational Tools and Systems for an Effective Architecture Essay

Writing an essay on architecture is a blend of creative expression and meticulous research. As you delve deep into topics, theories, and case studies, it becomes imperative to keep your resources organized and accessible.

This section introduces you to a set of tools and systems tailored for architectural essay writing.

Using Digital Aids

- Notion: This versatile tool provides a workspace that integrates note-taking, database creation, and task management. For an architecture essay, you can create separate pages for your outline, research, and drafts. The use of templates can streamline the writing process and help in maintaining a structured approach.

- MyBib: Citing resources is a crucial part of essay writing. MyBib acts as a lifesaver by generating citations in various styles (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) and organizing them for easy access. Make sure to cross-check and ensure accuracy.

- Evernote: This tool allows you to clip web pages, articles, or images that inspire or contribute to your essay. You can annotate, highlight, and categorize your findings in different notebooks.

Systematic Research

- Organizing Findings: Develop a system where each finding, whether it’s a quote, image, or data point, has its source attached. Use color-coding or tags to denote different topics or relevance levels.

- Note Galleries: Convert your key points into visual cards. This technique can be especially helpful in architectural essays, where visual concepts may be central to your argument.

- Sorting by Source Type: Separate your research into categories like academic journals, books, articles, and interviews. This will make it easier when referencing or looking for a particular kind of information.

Strategies for Effective Literature Review

- Skimming vs. In-depth Reading: Not every source needs a detailed read. Learn to differentiate between foundational texts that require in-depth understanding and those where skimming for key ideas is sufficient.

- Note-making Techniques: Adopt methods like the Cornell Note-taking System, mind mapping, or bullet journaling, depending on what suits your thought process best. These methods help in breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks.

- Staying Updated: The world of architecture is evolving. Ensure you’re not missing any recent papers, articles, or developments related to your topic. Setting up Google Scholar alerts or RSS feeds can be beneficial.

Organizing your research and using tools efficiently will not only streamline your writing process but will also enhance the quality of your essay. As you progress, you’ll discover what techniques and tools work best for you.

The key is to maintain consistency and always be open to trying out new methods to improve your workflow and efficiency.

Writing Techniques and Tips for an Architecture Essay

An architecture essay, while deeply rooted in academic rigor, is also a canvas for innovative ideas, design critiques, and a reflection of the architectural zeitgeist. Here’s a deep dive into techniques and tips that can elevate your essay from merely informative to truly compelling.

Learning from Others

- Read Before You Write: Before diving into your own writing, spend some time exploring essays written by others. Understand the flow, the structure, the narrative techniques, and how they tie their thoughts cohesively.

- Inspirational Sources: Journals, academic papers, architecture magazines, and opinion pieces offer a wealth of writing styles. Notice how varied perspectives bring life to similar topics.

Using Jargon Judiciously

- Maintain Clarity: While it’s tempting to use specialized terminology extensively, remember your essay should be accessible to a broader audience. Use technical terms when necessary, but ensure they’re explained or inferred.

- Balancing Act: Maintain a balance between academic writing and creative expression. Let the jargon complement your narrative rather than overshadowing your message.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

- Plagiarism – The Silent Offender: Always give credit where credit is due. Even if you feel you’ve paraphrased sufficiently, ensure your sources are adequately referenced. Utilize plagiarism check tools to ensure originality.

- Stay Focused: It’s easy to get lost in the vast world of architecture. Ensure your writing stays on topic, refraining from veering too far from your central theme.

- Conciseness: While detailed elaboration can be insightful, verbosity can drown your main points. Be succinct where necessary.

Craft a Compelling Introduction and Conclusion

- First Impressions: Your introduction should provide context, state the purpose of your essay, and capture the reader’s interest. Think of it as the blueprint of a building – it should give an idea of what to expect.

- Tying it All Together: Your conclusion should summarize your main points, reflect on the implications of your findings, and perhaps even propose further areas of study or exploration.

Use Active Voice

- Direct and Dynamic: Active voice makes your writing sound more direct and lively. Instead of writing, “The design was critiqued by several architects,” try “Several architects critiqued the design.”

Personalize your Narrative

- Your Unique Voice: Architecture, at its core, is about human experiences and spaces. Infuse your writing with personal observations, experiences, or reflections where relevant. This personal touch can make your essay stand out.

Revise, Revise, Revise

- The First Draft is Rarely the Final: Writing is a process. Once you’ve penned down your initial thoughts, revisit them. Refine the flow, enhance clarity, and ensure your argument is both cogent and captivating.

Remember, an architecture essay is both a testament to your academic understanding and a reflection of your perspective on architectural phenomena. Treat it as a synthesis of research, observation, creativity, and structured argumentation, and you’ll craft an essay that resonates.

Incorporating Sources Seamlessly

In architectural essays, as with most academic endeavors, sources form the backbone of your assertions and claims. They lend credibility to your arguments and showcase your understanding of the topic at hand. But it’s not just about listing references.

It’s about weaving them into your essay so seamlessly that your reader not only comprehends your point but also recognizes the strong foundation on which your arguments stand. Here’s how you can incorporate sources effectively:

Effective Quotation:

- Blend with the Narrative: Direct quotations should feel like a natural extension of your writing. For instance, instead of abruptly inserting a quote, use lead-ins like, “As architect Jane Smith argues, ‘…'”

- Use Sparingly: While direct quotes can validate a point, over-relying on them can overshadow your voice. Use them to emphasize pivotal points and always ensure you contextualize their significance.

- Adapting Quotes: Occasionally, for the sake of flow, you might need to change a word or phrase in a quote. If you do, denote changes with square brackets, e.g., “[The building] stands as a testament to modern design.”

Referencing Techniques:

- Parenthetical Citations: Most academic essays utilize parenthetical (or in-text) citations, where a brief reference (usually the author’s surname and the publication year) is provided within the text itself.

- Footnotes and Endnotes: Some referencing styles prefer notes, which can provide additional context or information without interrupting the flow of the essay.

- Consistency is Key: Stick to one referencing style throughout your essay, whether it’s APA, MLA, Chicago, or any other format.

Using Notes Effectively:

- Annotate as You Go: When reading, jot down insights or connections you make in the margins or in your note-taking app. This will help you incorporate sources in a way that feels relevant and organic.

- Maintain a Bibliography: Keeping a running list of all the sources you encounter will make the final citation process smoother. With tools like Zotero or MyBib, you can auto-generate and manage bibliographies with ease.

- Critical Analysis over Summary: While it’s vital to understand and convey the main points of a source, it’s equally crucial to critique, interpret, or discuss its relevance in the context of your essay.

Remember, the objective of referencing isn’t just to show that you’ve done the reading or to avoid accusations of plagiarism. It’s about building on the work of others to create your unique narrative and perspective.

Always strive for a balance, where your voice remains at the forefront, but is consistently and credibly supported by your sources.

Designing Your Essay

Architecture is an intricate tapestry of creativity, precision, and innovation. Just as a building’s design can make or break its appeal, the visual presentation of your essay plays a pivotal role in how it’s received.

Below are steps and strategies to ensure your architecture essay isn’t just a treatise of words but also a feast for the eyes.

Visual Aesthetics: More Than Just Words

- Whitespace and Balance: Much like in architecture, the empty spaces in your essay—the margins, line spacing, and breaks between paragraphs—matter. Whitespace can make your essay appear more organized and readable.

- Fonts and Typography: Choose a font that is both legible and evocative of your essay’s tone. A serif font like Times New Roman may offer a traditional, academic feel, while sans-serif fonts like Arial or Calibri lend a modern touch. However, always adhere to submission guidelines if provided.

- Use of Imagery: If allowed, incorporating relevant images, charts, or diagrams can enhance understanding and add a visual flair to your essay. Make sure to caption them properly and ensure they’re of high resolution.

Relevance to Topic: Visuals That Complement Content

- Thematic Design: Ensure any design elements—be they color schemes, borders, or footers—tie back to your essay’s topic or the architectural theme you’re discussing.

- Visual Examples: If you’re discussing a specific architectural movement or an iconic building, consider incorporating relevant images, sketches, or blueprints to give readers a visual point of reference.

Examples of Unique Design Ideas

- Sidebars and Callouts: Much like how modern buildings might feature a unique design element that stands out, sidebars or callouts can be used to highlight crucial points, quotes, or tangential information.

- Integrated Infographics: For essays discussing data, trends, or historical timelines, infographics can be an innovative way to present information. They synthesize complex data into digestible visual formats.

- Annotations: If you’re critiquing or discussing a specific image, annotations can be helpful. They allow you to pinpoint and elaborate on specific elements within the image directly.

Consistency is Key

- Maintain a Theme: Just as in architectural design, maintaining a consistent visual theme throughout your essay creates harmony and cohesion. This could be in the form of consistent font usage, header designs, or color schemes.

- Captions and References: Any visual aid, be it a photograph, illustration, or chart, should be captioned consistently and sourced correctly to avoid plagiarism.

In the realm of architectural essays, the saying “ form follows function ” is equally valid. Your design choices should not just be aesthetic adornments but should serve to enhance understanding, readability, and engagement.

By taking the time to thoughtfully design your essay, you are not only showcasing your architectural insights but also your keen eye for design, thereby leaving a lasting impression on your readers.

Finalizing Your Essay

Finalizing an architecture essay is a task that demands a meticulous approach. The difference between an average essay and an outstanding one often lies in the refinement process. Here, we explore the steps to ensure that your essay is in its best possible form before submission.

Proofreading:

- Grammar and Syntax Checks: Always use tools like Grammarly or Microsoft Word’s spellchecker, but remember, they aren’t infallible. After an initial electronic check, read the essay aloud. This can help in catching awkward phrasing and any overlooked errors.

- Consistency in Language and Style: Ensure that you maintain a uniform style and tone throughout. If you begin with UK English, for instance, stick with it till the end.

- Flow and Coherence: The essay should have a logical progression. Each paragraph should lead seamlessly into the next, with clear transitions.

Feedback Loop:

- Peer Reviews: Having classmates or colleagues read your essay can provide fresh perspectives. They might catch unclear sections or points of potential expansion that you might have missed.

- Expert Feedback: If possible, seek feedback from instructors or professionals in the field. Their insights can greatly enhance the quality of your content.

- Acting on Feedback: Merely receiving feedback isn’t enough. Be prepared to make revisions, even if it means letting go of sections you’re fond of, for the overall improvement of the essay.

Aligning with University Requirements:

- Formatting: Adhere strictly to the specified format. Whether it’s APA, Chicago, or MLA, make sure your citations, font, spacing, and margins are in line with the guidelines.

- Word Count: Most institutions will have a stipulated word count. Ensure you’re within the limit. If you’re over, refine your content; if you’re under, see if there are essential points you might have missed.

- Supplementary Materials: For architecture essays, you might need to attach diagrams, sketches, or photographs. Ensure these are clear, relevant, and properly labeled.

- Referencing: Properly cite all your sources. Any claim or statement that isn’t common knowledge needs to be attributed to its source. Also, ensure that your bibliography or reference list is comprehensive and formatted correctly.

Final Read-through:

- After making all the changes, set your essay aside for a day or two, if time permits. Come back with fresh eyes and do one last read-through. This distance can often help you catch any remaining issues.

Finalizing your architecture essay is as vital as the initial stages of research and drafting. The care you take in refining and polishing your work reflects your commitment to excellence. When you’ve gone through these finalization steps, you can submit your essay confidently, knowing you’ve given it your best shot.

To Sum Up…

Writing an architecture essay is a unique challenge that requires a balance of creativity, critical thinking, and academic rigor. The process demands not just a deep understanding of architectural theories and case studies but also an ability to express these complex ideas clearly and compellingly.

Throughout this article, we have explored various facets of crafting an excellent architecture essay, from choosing a resonant topic and conducting thorough research to employing effective writing techniques and incorporating sources seamlessly.

The visual aspect of an architecture essay cannot be overlooked. As architects blend functionality with aesthetics in their designs, so too must students intertwine informative content with visual appeal in their essays. This is an opportunity to showcase not only your understanding of the subject matter but also your creativity and attention to detail.

Remember, a well-designed essay speaks volumes about your passion for architecture and your dedication to the discipline.

As we wrap up this guide, it is crucial to emphasize the importance of meticulous proofreading and seeking feedback. These final steps are vital in ensuring that your essay is free from errors and that your arguments are coherent and compelling.

Engaging in a feedback loop with peers, mentors, or advisors can provide valuable insights and help to refine your work further.

Additionally, always ensure that your essay aligns with the specific requirements set forth by your university or institution. Pay attention to details like font styles, referencing methods, and formatting guidelines.

These elements, while seemingly minor, play a significant role in creating a polished and professional final product.

Keep practicing, keep learning, and remember that each essay is a stepping stone toward mastering the art of architectural writing.

FAQs about Architecture Essays

Do architecture students have to write essays.

Yes, architecture students often have to write essays as part of their academic curriculum. While architecture is a field that heavily involves visual and practical skills, essays and written assignments play a crucial role in helping students develop their critical thinking, research, and analytical skills.

While hands-on design work and practical projects are integral parts of an architectural education, essays play a crucial role in developing the theoretical, analytical, and communication skills necessary for success in the field.

By writing essays, architecture students learn to think critically, research effectively, and communicate their ideas clearly, laying a strong foundation for their future careers.

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!.

As seen on:

Unlock access to all our new and current products for life .

Providing a general introduction and overview into the subject, and life as a student and professional.

Study aid for both students and young architects, offering tutorials, tips, guides and resources.

Information and resources addressing the professional architectural environment and industry.

- Concept Design Skills

- Portfolio Creation

- Meet The Team

Where can we send the Checklist?

By entering your email address, you agree to receive emails from archisoup. We’ll respect your privacy, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

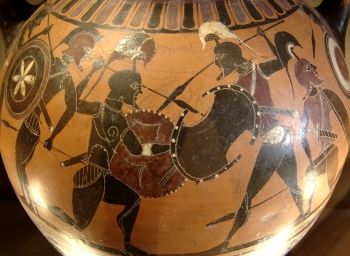

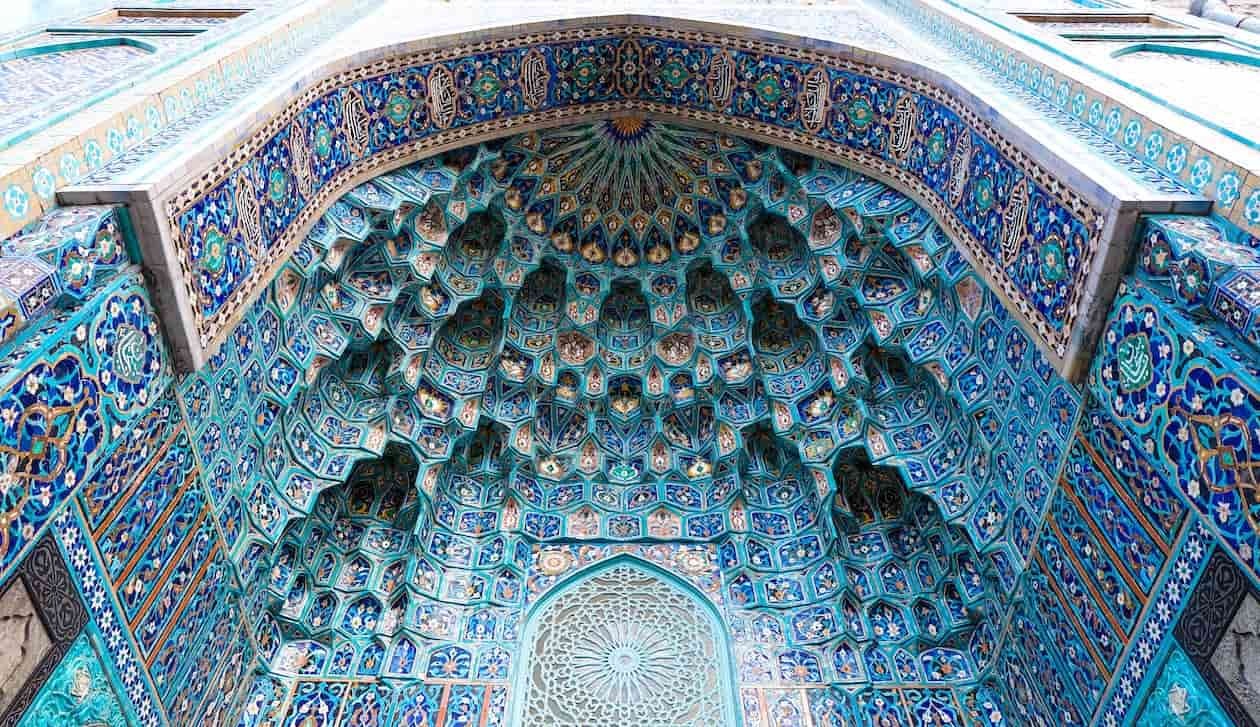

The Intersection of Art and Architecture: Unveiling the Prime Influence

Art in Architecture combines art and science that revolves around space, events, movement, and time. Architecture has been described as ‘ art ‘ due to its creative nature and visual appeal. The fusion of art and architecture has resulted in inspiring and spiritually uplifting designs. Throughout history, different art movements have influenced architecture. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jugendstil, an art nouveau style, emerged, inspired by organic forms and the relationship between humans and nature. This movement translated into architecture with organic lines, nature-inspired motifs, and engineered and natural materials. Another influential art movement was Dadaism , which emerged as a rebellious and revolutionary response to war and capitalist culture. Dada art featured irrational concepts and aimed to ridicule societal norms. These art movements have significantly impacted modern architecture, breaking traditional structures and focusing on simplicity, functionality, and multiple perspectives. These movements have shaped architectural styles globally, from vibrant colours in Art Nouveau to minimalism in the 1960s. Art in Architecture highlights the importance of creativity, emotion, and community beyond mere functionality in the built environment.

The impact of architectural design on art movements

While art has undoubtedly influenced architecture throughout history, it is essential to recognise the reciprocal relationship between the two disciplines. Architectural design has often catalyzed new art movements, pushing artists to explore new techniques and concepts. The Industrial Revolution , for instance, brought about significant changes in architectural design with the rise of steel and glass structures. This newfound architectural landscape inspired artists like Claude Monet and the Impressionists to capture the changing urban environment, resulting in a shift towards more experimental and vibrant artistic styles.

Similarly, the advent of modernist architecture in the early 20th century, characterised by minimalist forms and functional design, influenced art movements like Cubism and Constructivism . Artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, inspired by modernist architecture’s geometric shapes and clean lines, translated these principles into their paintings, revolutionising the art world. The interplay between art and architecture in this period challenged traditional boundaries and sparked innovation in both disciplines.

Case studies: Examining famous architectural works influenced by art

In order to improve the built environment, whether in cities, workplaces, healthcare facilities, or public green spaces, art and architecture must be interwoven. Eye-catching buildings like The Esplanade and Changi Jewel in Singapore showcase how art can be combined with architecture. Some people hold the opinion that architecture is an art form in and of itself and does not need the presence of artists in the design process. However, the fusion of art and architecture can create something greater than the sum of its parts. For millennia, artists and designers have been attracted to the union of art and architecture. Architects should consider art as a vital aspect of their work, as it can enhance the character of a space and create a more environmentally conscious society. Architecture must not only serve functional needs but also inspire and have an emotional impact. By incorporating art into the design of a structure, it can transform the space and evoke emotions in its occupants. Hanging art on the walls is a simple yet transformative design strategy that can be used to incorporate art into the overall design.

Contemporary examples: How art and architecture continue to intersect

Art and architecture continue to intersect in fascinating ways in contemporary times, with architects and artists collaborating to create immersive spaces that engage and inspire. One such example is the Tokyo Skytree in Japan , designed by architect Tadao Ando. This towering structure, one of the tallest towers in the world, combines architectural prowess with artistic sensibility. Ando’s design incorporates elements of Zen philosophy and traditional Japanese aesthetics, creating a serene and harmonious environment for visitors. The observation decks, with their panoramic views of Tokyo, offer a unique artistic experience, merging the beauty of the cityscape with the architectural marvel.

Another noteworthy example is the Louvre Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, designed by architect Jean Nouvel. This cultural institution combines art, architecture, and nature, creating a mesmerising experience for visitors. Nouvel’s design features a series of interconnected buildings covered by a stunning geometric dome that filters sunlight, creating a captivating play of light and shadows. The architectural design not only complements the art within the museum but also becomes a work of art in itself, blurring the boundaries between the interior and exterior spaces.

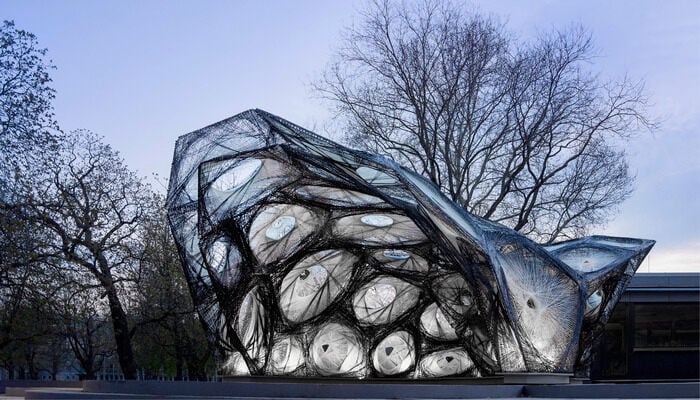

The Role of Technology in the Fusion of art and Architecture

Technology has played a significant role in the fusion of art and architecture, offering new possibilities for collaboration and immersive experiences. The Serpentine Pavilion in London is an annual showcase for this fusion, with renowned architects incorporating interactive installations and digital art. Advancements in parametric design and 3D printing have also revolutionised architectural possibilities, allowing for intricate and innovative structures that blur the lines between art and architecture.

Criticisms and controversies surrounding the integration of art and architecture

Criticisms and controversies exist within this integration. Some argue that architectural designs can overshadow the art within a space, detracting from the intended experience. The allocation of public funds to integrate art into architectural projects is also a point of contention, with some questioning the practicality of such investments .

The future of art and architecture: Emerging trends and possibilities

In the future, sustainability and eco-conscious design will be increasingly important in the fusion of art and architecture. Architects and artists are incorporating sustainable materials and energy solutions into their creations. Additionally, the rise of interactive and immersive experiences through virtual, augmented, and mixed-reality technologies will reshape engagement with art and architecture. These technologies will democratise access to creativity and collaboration, transcending physical limitations.

Admin (2021) How can art enhance an architecture , Minimalism.sg . Available at: http://minimalism.sg/how-can-art-enhance-an-architecture/ (Accessed: 02 July 2023).

Saha, S. and Chinurkar, K. (2023) Art in architecture: A strong influence , The Design Gesture . Available at: https://thedesigngesture.com/art-in-architecture-a-prime-influence/ (Accessed: 02 July 2023).

Art Nouveau Architecture: Features & Famous Examples (no date) Gira . Available at: https://www.gira.com/en/en/g-pulse-magazine/architecture/art-nouveau#origins (Accessed: 02 July 2023).

An overview of European Award for Architectural Heritage Intervention AADIPA

An architectural review of location: Antigua, Guatemala

Related posts.

LEED for Show: Exploring the Pitfalls of Building Green for Certification Alone

The Housing Crisis in Asia

From Bytes to Building

Why going to events important as a budding professional

Embroidering our Heritage through Textiles

Sustainability: The Ethical Principle of Architecture

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Looking for Job/ Internship?

Rtf will connect you with right design studios.

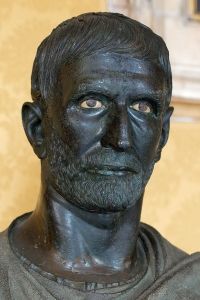

Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

Summary of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

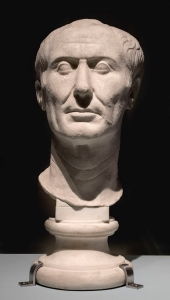

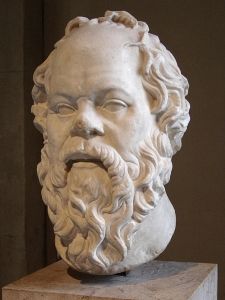

Classical Art encompasses the cultures of Greece and Rome and endures as the cornerstone of Western civilization. Including innovations in painting, sculpture, decorative arts, and architecture, Classical Art pursued ideals of beauty, harmony, and proportion, even as those ideals shifted and changed over the centuries. While often employed in propagandistic ways, the human figure and the human experience of space and their relationship with the gods were central to Classical Art. Over the span of almost 1200 years, ideals of human beauty and proportion occupied art's subject. Variations of those ideals were later adopted during the Renaissance in Italy and again during the 18 th and 19 th century Neoclassical trend throughout Europe. Connotations of moral virtue and stability clung to Classical Art, making it attractive to new nations and republics trying to find an aesthetic vocabulary to convey their power, while, later, in the 20 th century it came under attack by modern artists who sought to disrupt and overturn power and traditional ideals.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

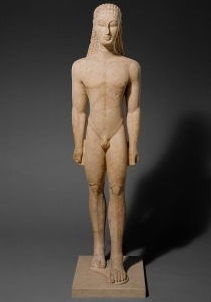

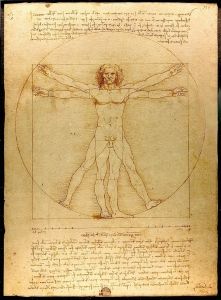

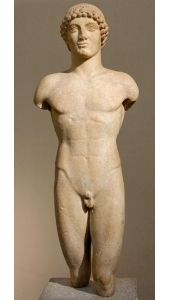

- The idealized human form soon became the noblest subject of art in Greece and was the foundation for a standard of beauty that dominated many centuries of Western art. The Greek ideal of beauty was grounded in a canon of proportions, based on the golden ratio and the ratio of lengths of body parts to each other, which governed the depictions of male and female figures.

- While ideal proportions were paramount, Classical Art strove for ever greater realism in anatomical depictions. This realism also came to encompass emotional and psychological realism that created dramatic tensions and drew in the viewer.

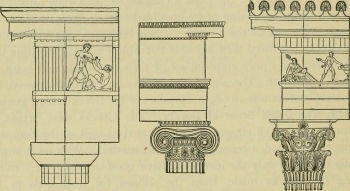

- Greek temple designs started simply and evolved into more complex and ornate structures, but later architects translated the symmetrical design and columned exterior into a host of governmental, educational, and religious buildings over the centuries to convey a sense of order and stability.

- Perhaps a coincidence, but just as increased archaeological digs turned up numerous examples of Greek and Roman art, the field of art history was being developed as a scientific course of study by the likes of Johann Winkelmann. Winkelmann, often considered the father of art history, based his theories of the progression of art on the development of Greek art, which he largely knew only from Roman copies. Since the middle of the 18 th century, art historical and classical tradition have been intimately entwined.

- While Greek and Roman sculpture and ruins are linked with the purity of white marble in the Western mind, most of the works were originally polychrome, painted in multiple, lifelike colors. 18 th century excavations unearthed a number of sculptures with traces of color, but noted art historians dismissed the findings as anomalies. It was only in the late 20 th century that scholars accepted that life-size statues and entire temple friezes were, in fact, brightly painted with numerous colors and decorations, raising many new questions about the assumptions of Western art history and revealing that centuries of classical imitations were not in fact imitations but rather based on nostalgic ideals of the past.

Artworks and Artists of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

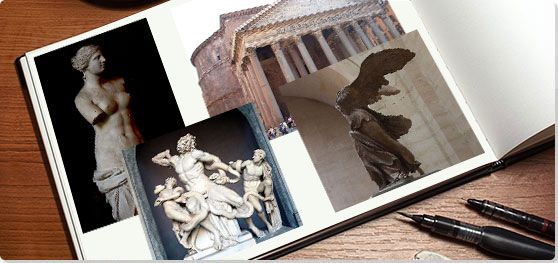

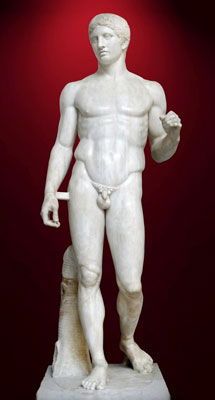

Roman copy 120-50 BCE of original by Polycleitus, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) c. 440 BCE

This work depicts a nude muscular warrior, as he steps forward, his head turns slightly to his right, and his left hand would have readied a spear that originally rested upon his left shoulder. The figure's anatomical realism conveys potential movement through a complex interaction of tensed and relaxed muscles. Almost seven feet tall, the monumental work conveys an imposing sense of male heroic beauty that could face whatever may come with dispassionate calm, as shown in the serious but expressionless face. Because marble copies needed additional support, the tree stump was an addition to the bronze original. What is known of the original is based upon the exceptional quality of later copies, including this one. Polycleitus thought this work was synonymous with his Canon, a treatise of sculptural principles, based upon mathematical proportions. Though his treatise has been lost, references to it survived in later accounts, including Galen's, a 2 nd century Greek writer, who wrote that its "Beauty consists in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other." At the time it was made, the work was widely acclaimed, as Warren G. Moon and Barbara Hughes Fowler write, the Doryphorus ushered in "a new definition of true human greatness...an artistic moral exemplar...tied to no particular place or action, he represents the universal male ideal." This marble copy, found in a gymnasium at Pompeii, became the most admired work of the Roman Republic, as Roman aristocrats commissioned copies.

Marble copy of bronze original - Naples National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy

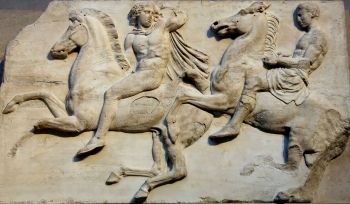

The Parthenon

Artist: Ictinus and Callicrates

This iconic temple, dedicated to Athena, goddess of wisdom and patron of Athens, stands majestically on top of the Acropolis, a sacred complex overlooking the city. The 17 Doric columns on either side and the eight at each end create both a sense of harmonious proportion and a dynamic visual and horizontal movement. The building exemplifies the Doric order and the rectangular plan of Greek temples, which emphasized a flow of movement and light between the temple's interior and the surrounding space, while the movement of the columns, rising out of the earth, to the entablature that rings the building, draws the eye heavenward to the carved reliefs and statues that, originally, brightly painted, crowned the temple. Ictinus and Callicrates were identified as the architects of the building in ancient sources, while the sculptor Phidias and the statesman Pericles supervised the project. Dedicated in 438 BCE, the Parthenon replaced the earlier temple on the city's holy site that also included a shrine to Erechtheus, the city's mythical founder, a smaller temple of the goddess Athena, and the olive tree that she gave to Athens, all of which were destroyed by the invading Persian Army in 480 BCE. The Persians also killed the priests, priestesses, and citizens who had taken refuge at the site, and, when the new Parthenon was dedicated, following that experience of trauma and desecration, it was a monument to the restoration and continuation of Athenian values and became, as art critic Daniel Mendelsohn wrote, a "dramatization of the political and moral differences between the victims and the perpetrators." As Mendelsohn noted, the Parthenon while taken "as the epitome of Greek architecture...was typical of nothing at all, an anomaly in terms of material, size, and design." It was both the largest temple in Greece and the first built of only marble. While Doric temples commonly had thirteen columns on each side and six in the front, the Parthenon pioneered the octastyle, with eight columns, thus extending the space for sculptural reliefs. Originally the Parthenon Marbles decorated the entablature, as 92 metopes , or rectangular stone panels, depicted mythological battle scenes - of gods fighting giants, Greek warriors fighting Trojans or Amazons, and men battling centaurs - while the pediments contained statues depicting the stories of Athena's life, so that as Mendelsohn wrote, "Merely to walk around the temple was to get a lesson in Greek and Athenian civic history." The temple's interior was equally meant to inspire, as Phidias's colossal statue of Athena Parthenos , or the virgin Athena, dominated the space. Forty feet tall, the statue held a six foot tall gold statue of Victory in her hand. A frieze, carved in relief, lined the surrounding walls, innovatively introducing a decorative feature of Ionic architecture into the Doric order. The 525 foot long frieze has been described by art historian Joan Breton Connelly as "showing 378 human and 245 animal figures... the largest and most detailed revelation of Athenian consciousness we have ... this moving portrayal of noble faces from the distant past, ... the largest, most elaborate narrative tableau the Athenians have left us." The Parthenon's design employed precise mathematical proportions, based upon the golden ratio, but as Mendelsohn noted, "There are almost no straight lines in the building." The columns employ entasis , a swelling at the center of each column, and tilt inward, while the foundation also rises toward the façade, correcting for the optical illusion of sagging and tilting that would have resulted in perfectly straight lines. Aesthetically, though, as Mendelsohn explains, "[T]he slight swelling also conveys the subliminal impression of muscular effort...Arching, leaning, straining, swelling, breathing: the over-all effect...is to give the building a special and slightly unsettling quality of being somehow alive." The building has been highly praised since ancient times as the 1 st century Roman historian Plutarch called it "no less stately in size than exquisite in form," and in the modern era, Le Corbusier called it "the basis for all measurement in art."

Marble - Athens, Greece

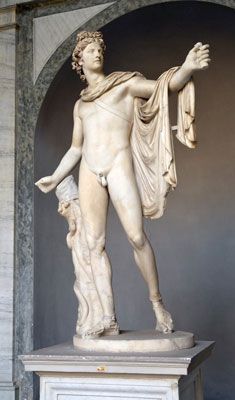

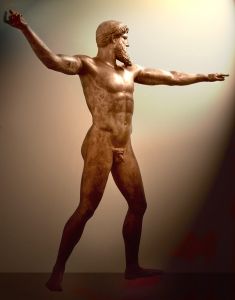

Apollo Belvedere, Roman copy, c. 120 - 140 CE of Leochares bronze original c. 350-325 BCE

This nude statue, a little over seven feet tall, depicts Apollo, the Greek god of art and music, as he strides forward, having just shot an arrow from a bow which his extended left hand originally held. Realistic in its anatomical modeling, the work conveys a sense of gravity, both in his form as seen in the musculature of his weight-bearing right leg and in the folds of his chlamys , or robe, falling across his left arm. Contrapposto is employed innovatively to create a sense of complex movement, presenting the statue both frontally and in profile as the god strides forward majestically. While the statue is identified as the god by the headband he wears, reserved for gods or rulers, and his bow and the quiver across his left shoulder, he is also equally a symbol of youthful masculine beauty. The work has also been called the Pythian Apollo, as it was believed to depict Apollo's slaying of the Python, a mythical serpent at Delphi, marking the moment when the site became sacred to the god and home of the famous Delphic Oracle. The marble statue is believed to be a Roman copy of an original bronze from the 4 th century by the Greek sculptor Leochares. The work was discovered in 1489 and became part of the collection of Cardinal Giulano della Rovere who, subsequently, became Pope Julius II, the leading patron of the Italian High Renaissance. He put the work on public display in 1511, and Michelangelo's student, the sculptor Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, restored the missing parts of the left hand and right arm. Much acclaimed, the work was sketched by Michelangelo, Bandinelli, Goltzius, and Albrecht Dürer who modeled Adam upon Apollo in his engraving Adam and Eve (1504). Marcantonio Raimondi made a copy of the Apollo, and his engraving in the 1530s was widely disseminated throughout Europe; however, the work became most influential in the 1700s as Winckelmann, the pioneering German art historian, wrote, "Of all the works of antiquity that have escaped destruction, the statue of Apollo represents the highest ideal of art." The work became fundamental to the development of Neoclassicism as seen in Antonio Canova's Perseus (1804-1806) modeled after the work. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted, "The work was admired two hundred years ago as an image of the absolute rational clarity of Greek civilisation and the perfect harmony of divine beauty," but in the Romantic era it fell into disfavor as the leading critics, John Ruskin, William Hazlitt, and Walter Pater critiqued it. Still, it has remained popular and frequently reproduced, lending it a cultural currency, as seen in the official seal of the 1972 Apollo XVII moon landing mission.

Marble - Vatican City

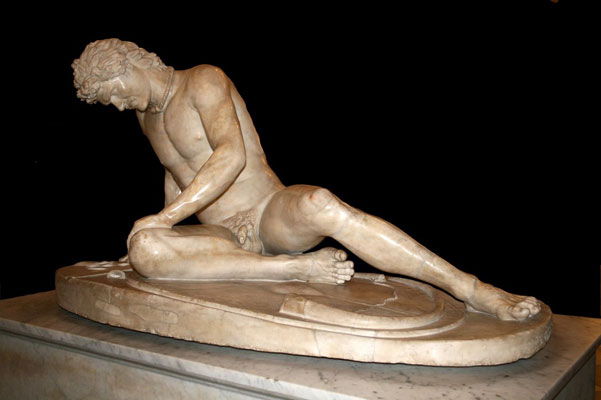

The Dying Gaul, Roman marble copy of Greek bronze by Epigonus

This Roman copy of a Greek Hellenistic work depicts a nude and dying man, identified as a Gaul or more specifically a Galatian, a member of a Celtic tribe in Pergamon, a Greek city in Turkey. Sitting on the ground, his left hand grasping his left knee, and his right hand resting upon a broken sword as he holds himself up, he looks down as if contemplating his end. His extended legs and the twist of his torso suggest pain and immanent collapse. The work is realistic and emotionally expressive, as the tension between tensed and relaxed muscles conveys his struggle to fight off death. A pensive and somber feeling dominates the work, making it an intense reflection on defeat and mortality, while the idealization of his physical beauty suggests a heroic death. The statue was discovered sometime in the early 1600s at the Villa Ludovisi, the country residence of a wealthy and powerful Italian family, and was originally believed to depict a Roman gladiator. The work was popular and viewing it became a necessary part of the Grand Tour undertaken by young aristocrats in the 18 th and 19 th centuries. The British Romantic poet, Lord Byron whose famous poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812) was written following his Grand Tour, wrote, "I see before me the gladiator lie/ He leans upon his hand - his manly brow/ Consents to death, but conquers agony." Its popularity led to a proliferation of marble and plaster copies across Europe. In the 19 th century, scholars identified the subject as a Gaul, due to his hairstyle and the torque he wears on his neck, and Epigonus, a court appointed sculptor of Pergamon, as the original artist. The original was part of a complex sculpture group to celebrate Pergamon's victory over the Gauls and exemplifies what was called the "Pergamene Style," which as contemporary art critic Jerry Saltz noted, "emphasized emotional appeal and almost Baroque volatility. Nothing defines that style quite as clearly as the Dying Gaul , who is both tragic and sensual, firing both our desire and our sense of compassion."

Marble - Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy

Winged Victory of Samothrace

This monumental work, depicting Nike, the goddess of victory, and created in honor of a naval victory, emphasizes dynamic movement, as the goddess surges forward, swept by the wind, her wings unfurled behind her. As art historian H.W. Jansen wrote, "This invisible force of on-rushing air here becomes a tangible reality; it not only balances the forward movement of the figure but also shapes every fold of the wonderfully animated drapery. As a result, there is an active relationship - indeed, and interdependence - between the statue and the space that envelops it, such as we have never seen before." Over 18 feet tall, the Hellenistic statue stands on a pedestal, placed upon a base that resembles the prow of a ship. Most scholars believe the work was originally placed at the Sanctuary of the Greek Gods, a temple complex overlooking the harbor on the island of Samothrace. Charles Champoiseau, a French envoy, discovered the fragmented statue in 1863 and sent it to Paris where it was reassembled and placed in the Louvre, famously dominating the view up the grand staircase. The work influenced a number of modern artists and movements, as Umberto Boccioni's Futuristic work Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) references the statue, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti also referenced it in his Futurist Manifesto (1903). The American sculptors Samuel Murray and Augustus Saint-Gaudens created Nike-like figures, as seen in Saint Gauden's Sherman Memorial (1903) and the statue was a favorite work of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who included reproductions of it in a number of his residential designs. Yves Klein painted a number of plaster copies, painted in his International Klein Blue and using a resin he named Victoire de Samatrace , and more recently, Banksy's CCTV Angel (2006) repurposed the figure.

Parian Marble - Louvre Museum, Paris

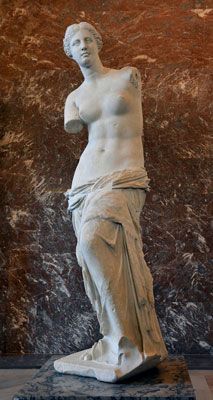

Venus de Milo

Artist: Alexandros of Antioch

Believed to portray Venus, the goddess of love, this six-and-a-half-foot statue creates dynamic visual movement with its accentuated s-curve, emphasizing the curve of the torso and hip, as the lower part of her body is draped in the realistic folds of her falling robe. The dramatic contrapposto , her left knee raised as if lifting her foot off the ground, further emphasizes her movement, as she turns toward the viewer. The work was originally attributed to Praxiteles but is now generally credited to Alexandros of Antioch. Scholarly dispute continues about the identity of its subject; traditionally identified as Venus, some scholars believe the work actually portrays Amphitrite, a sea goddess, worshipped on the island of Milo where the sculpture was found in 1820, and some contemporary scholars have suggested the figure may in fact portray a prostitute. The statue was made from several pieces of marble, two blocks used for the body, while other parts, including the legs and left arm, were sculpted individually and then attached. When excavated in 1820, part of an arm and a fragmented hand holding a round orb were discovered with the statue, which stood upon a stone plinth. At the time, the fragments were discarded, due to their 'rougher' finish, and later so was the plinth. It's believed that, originally, the statue was brightly painted and adorned with expensive jewelry. During his Italian campaign Napoleon Bonaparte took the Medici Venus (1 st century BCE), then the most renowned classical female nude, to France and installed it in the Louvre. But in 1815 the French returned the Medici Venus and bought the Venus de Milo , which they promoted both as the finest classical work and a model of feminine grace and beauty. More than any other classical sculpture, this iconic nude has greatly influenced both modern art and culture, due to its compelling ideal of feminine beauty and its beguiling mystery. As art critic Jonathan Jones writes, "The Venus de Milo is an accidental surrealist masterpiece. Her lack of arms makes her strange and dreamlike. She is perfect but imperfect, beautiful but broken - the body as a ruin. That sense of enigmatic incompleteness has transformed an ancient work of art into a modern one." Salvador Dalí's Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936) copied the work but inserted pull drawers with pink pompom handles into the torso. As Jones noted, the Venus de Milo has retained its contemporary artistic relevance because it "entered European culture in the 19th century just as artists and writers were rejecting the perfect and timeless." As a result, the work haunts the modern imagination, referenced in literature, films, and television episodes and used in any number of advertisements, while its impact on cultural concepts of feminine beauty can be seen in the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' use of the figure on its seal in 1930.

Marble - Louvre Museum, Paris

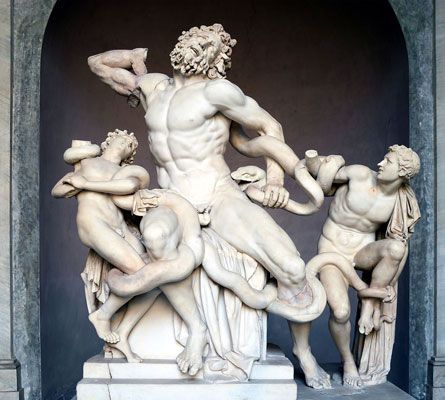

Laocoön and His Sons

Artist: Agesandro, Athendoros, and Polydoros

This famous work depicts the doomed struggle of Laocoön, and his two sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus caught in the coils of two giant poisonous sea serpents, one of them biting Laocoön's hip. His hand grasps the snake's neck as he tries to fend it off. On the left, the youngest boy, dying from the poison, has collapsed, his legs caught in the coils that lift him off the ground. The central figure is the father, whose powerful muscular form twists upward and backward, his despairing and contorted gaze turned heavenward, as his son on the right turns to look pleadingly at him. Drawing upon the story of the Trojan war, the work is thought to dramatically depict the moment when Laocoön, a priest of Troy who warned the Trojans against taking the Greek wooden horse into the city, was attacked, along with his two sons, by the serpents sent by the gods to silence him. As a result the frightened Trojans, fearing the gods' punishment, took in the wooden horse containing the Greek soldiers, who, hidden within it, came out at night to open the gates for the Greek army, leading to the fall of Troy. Art historian Nigel Spivey has called the work "the prototypical icon of human agony," and its dynamic sense of drama and its use of slightly unrealistic scale to emphasize paradoxically the father's power and helplessness made it innovative and a masterwork of the Hellenistic style. In 1506 the work was discovered during excavations of Rome and immediately drew the attention of Pope Julius II who sent Michelangelo to oversee the excavation. Its identification drew upon the ancient accounts of Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer, who described the work as located in the emperor Titus's palace and attributed it to the Rhodes sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus. The work greatly influenced Michelangelo, including some of his figures in the Sistine Chapel ceiling and his later sculpture. Raphael depicted Homer with Laocoon's face in his Parnassus , and Titian drew upon the work for his Averoldi Altarpiece (1520-24), as did Rubens for his Descent from the Cross . (1612-14). William Blake also referenced the sculpture, though within his own belief that imitations of Classical Art destroyed the creative imagination. The work informed a number of ongoing debates, as to whether sculpture or painting were more primary, and has played a role in modern discourses, as seen in Irving Babbit's (1910) The New Laokoon: An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts (1910) and Clement Greenberg's Towards a Newer Laocoön (1940), where he argued for abstract art as the new, equivalent, ideal. The Henry Moore Institute held a 2007 exhibition with this title while showing modern works influenced by the statue, and contemporary artist Sanford Biggers has referenced the work within his contemporary installation pieces.

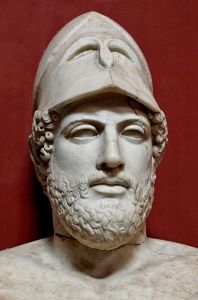

Augustus of Prima Porta

This statue depicts Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome, in military uniform, his right arm raised in a gesture of leadership, addressing the military and populace of Rome. His contrapposto pose, the muscular modeling of his breastplate, and his dispassionate expression are informed by Polycleitus's Doryphorus , as the emperor is presented as the new model of the universal male ideal. His breastplate is intricately carved with scenes and figures - including the sun, sky, and earth gods, a diplomatic victory over the Parthians, and female figures representing conquered countries - that establish him as a military leader, founder of the Pax Romana, and heir of Rome's mythological and historical traditions. Tugging at his right, a small cupid rides a dolphin that symbolizes Augustus's victory at the 31 BCE Battle of Actium over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, which made him sole ruler. At the same time, the cupid, representing Eros, a son of the goddess Venus, refers to Julius Caesar's claim that he was descended from the goddess. As Augustus was Caesar's grand-nephew and adopted heir, he establishes his divine patrimony and connects it to the legendary founding of Rome by Aeneas, the only mortal son of Venus and the only surviving Trojan prince. The statue is barefoot, a trope associated with portrayals of divinity, and as art critic Alastair Sooke noted, the work, "is not simply a portrait of Rome's first emperor...it is also a vision of a god." Emerging victorious from a civil war that followed the assassination of Julius Caesar, Augustus launched a notable building campaign, saying later, "I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble." His image became a powerful propaganda tool, as art critic Roderick Conway Morris wrote, "He projected his image through art and architecture and...this gave birth to a new classical Roman style, which would long outlive the first emperor and influence imperial and dynastic art over the next two millennia." As a result, more images of Augustus in statues, busts, coins, and cameos, all depicting him as this ever youthful and virile leader, survive than of any other Roman emperor. While Romans were known for their exacting portraiture, Augustus insisted on the idealized, youthful image throughout his reign to distance himself from any unrest in the empire. The work was rediscovered following its excavations in 1863 at Prima Porta, a villa which belonged to Augustus's wife, and as Sooke wrote, "Since its rediscovery, this charismatic work of art has become a symbol of ancient Rome's peculiar blend of refinement and ruthless military might." As a result, it has had a somewhat notorious afterlife, as when the Italian dictator Mussolini held an art exhibition in 1937 dedicated to Augustus and included this work in order to identify Fascist Italy with a new Roman Empire.

The circular temple faces the street with a monumental portico, employing eight Corinthian columns at the front with double rows of four columns behind, to create an imposing entrance. The façade, evoking the octastyle of the Athenian Parthenon, also emphasized that Rome was the heir of the classical tradition. The large granite columns rise to an entablature with an inscription reading "Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this] when consul for the third time." Though Agrippa's temple, built during the reign of the Emperor Augustus (27 BCE-14 CE), burned down, the Emperor Hadrian retained the inscription when he rebuilt the temple. The building's innovative and distinctive feature was its concrete dome; with a height and diameter of 142 feet, still, the world's largest dome made of unreinforced concrete. The interior was equally innovative, as the dome rose above a circular interior chamber, illuminated by an oculus opening to the sky in the center of the coffered dome, creating a sense of both an imperial and divine space. "Pantheon" means "relating to the gods," and scholars continue to debate whether this meant the temple was dedicated to all the gods or followed tradition in being dedicated to a specific god. Specific dedications to single gods were considered more provident since, if any mishap struck, the people would know which god had been offended and could offer sacrifices. When Agrippa first built the temple, it was part of the Agrippa complex (29-19 BCE) that also included the Baths of Agrippa and the Basilica of Neptune, and it is thought that the façade is what remains of his original structure. The building is one of the best preserved from the Imperial Roman era, as it was turned into a Christian church in the 7 th century, though it has also been altered, and many of the relief sculptures of gilded bronze were melted down. The work influenced Filippo Brunelleschi's dome of Florence Cathedral in 1436, a radical design that transformed architecture and informed the development of the Italian Renaissance. The Pantheon also informed the Baroque movement, as seen in Bernini's Santa Maria Assunta (1664), and the Neoclassical movement, as seen in Thomas Jefferson's Rotunda (1817-26) on the grounds of the University of Virginia.

Marble, concrete, bronze, stone - Rome, Italy

Beginnings of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

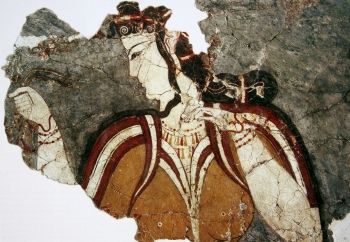

Mycenaean influences 1600-1100 bce.

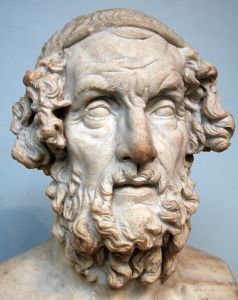

Considered the first Greeks, the Mycenaeans had a lasting influence on later Greek art, architecture, and literature. A bronze age civilization that extended through modern day southern Greece as well as coastal regions of modern day Turkey, Italy, and Syria, Mycenaea was an elite warrior society dominated by palace states. Divided into three classes - the king's attendants, the common people, and slaves - each palace state was ruled by a king with military, political, and religious authority. The society valorized heroic warriors and made offerings to a pantheon of gods. In later Greek literature, including Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey , the exploits of these warriors and gods engaged in the Trojan War had become legendary and, in fact, appropriated by later Greeks as their founding myths.

Agriculture and trade were the economic engines driving Mycenaean expansion, and both activities were enhanced by the engineering genius of the Mycenaeans, as they constructed harbors, dams, aqueducts, drainage systems, bridges, and an extended network of roads that remained unrivaled until the Roman era. Innovative architects, they developed Cyclopean masonry, using large boulders, fit together without mortar, to create massive fortifications. The name for Cyclopean stonework came from the later Greeks, who believed that only the Cyclops, fierce one-eyed giants of myth and legend, could have lifted the stones. To lighten the heavy load above gates and doorways, the Mycenaeans also invented the relieving triangle, a triangular space above the lintel that was left open or filled with lighter materials.

The Mycenaeans first developed the acropolis, a fortress or citadel, built on a hill that characterized later Greek cities. The king's palace, centered on a megaron , or circular throne room with four columns, was decorated with vividly colored frescoes of marine life, battle, processions, hunting, and gods and goddesses.

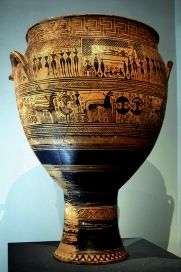

Scholars still debate how the Mycenaean civilization declined, and theories include invasions, internal conflict, and natural disasters. The era was followed by what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, though it is also known as the Homeric Age and the Geometric period. The term Homeric Age refers to Homer whose poems narrated the Trojan War and its aftermath. The term Geometric period refers to the era's style of vase painting, which primarily employed geometric motifs and patterns.

Greek Archaic Period 776-480 BCE

The Archaic Period began in 776 BCE with the establishment of the Olympic Games. Greeks believed that the athletic games, which emphasized human achievement, set them apart from "barbarian," non-Greek peoples. The Greeks' valorization of the Mycenaean era as a heroic golden age led them to idealize male athletes, and the male figure became dominant subjects of Greek art. The Greeks felt that the male nude showed not only the perfection and beauty of the body but also the nobility of character.

The Greeks developed a political and social structure based upon the polis, or city-state. While Argus was a leading center of trade in the early part of the era, Sparta, a city state that emphasized military prowess, grew to be the most powerful. Athens became the pioneering force in the art, culture, science, and philosophy that became the basis of Western civilization. Though the era was dominated by the rule of tyrants, Solon, a philosopher king, became the ruler of Athens around 594 BCE and established notable reforms. He created the Council of Four Hundred, a body that could question and challenge the king, ended the practice of putting people into slavery for their debts, and established a ruling class based on wealth rather than descent. Extensive sea-faring trade drove the Greek economy, and Athens, along with other city-states, began establishing trading posts and settlements throughout the Mediterranean. As a result of these forays, Greek cultural values spread to other cultures, including the Etruscans in southern Italy, influencing and co-mingling with them.

Figurative sculpture was the greatest artistic innovation of the Archaic period as it emphasized realistic, though idealized, figures. Influenced by Egyptian sculpture, the Greeks transformed the frontal poses of pharaohs and other notables into works known as kouros (young men) and kore (young women), life-sized sculptures that were first developed in the Cyclades islands in the 7 th century BCE. During the late Archaic period, individual sculptors, including Antenor, Kritios, and Nesiotes, were celebrated, and their names preserved for posterity.