Effectiviology

Double Standards: What They Are and How to Respond to Them

A double standard is a principle or policy that is applied in a different manner to similar things, without proper justification. Essentially, this means that a double standard occurs when two or more things, such as individuals or groups, are treated differently, when they should be treated the same way.

- For example, a double standard can involve treating two similar employees differently after they do the same thing, by punishing one and rewarding the other, even though there is no valid reason to do so.

Because double standards can have serious consequences, it’s important to understand them. As such, in the following article you will learn more about double standards, and see what you can do in order to respond to their use, as well as what you can do to avoid using them yourself.

Examples of double standards

One example of a double standard is a teacher who treats two similar students differently for no good reason, by grading one of them much more harshly, simply because they personally dislike that student.

Another example of a double standard is a person who criticizes others for doing something, even though this person does the same thing regularly and doesn’t see an issue with what they do when they’re the ones doing it.

A famous literary example of double standards appears in George Orwell’s 1945 novel “ Animal Farm “, in which a group of animals decides to take over the farm where they live, so they can rule themselves instead of having humans rule over them. One of the core rules that the animals decide to follow is that “all animals are equal”. However, as time passes, the pigs gather power over the other animals, and give themselves preferential treatment in a variety of ways. Eventually, this culminates in the pigs revoking all the rules that the animals initially agreed on, in place of a single rule, which exemplifies the concept of double standards: “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”.

Another famous example of double standards appears in the Latin phrase “quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi” which can be translated as ‘‘what is permissible for Jove (who is also known as ‘Jupiter’, and who is the king of the gods in Roman mythology), is not permitted to cattle”. This concept has been described as being a double standard that is antithetical to the rule of law:

“[This phrase] has always seemed to me to symbolize the opposite of what I consider to be the rule of law. And the rule of law is what I perceive and consider judging to be about—at least it is why I went into judging rather than into some of the previous endeavors that Roger’s introduction of me laid out at some length. The rule of law means that, to the extent that fallible judges are capable of adhering to it, the expectation is that when you go before a court, the outcome depends on the merits of your case, not your political status, relation to the court, or other personal characteristics. It does not mean that the law is a mechanical enterprise—it cannot be. But it should mean that the judge will apply the same standards to the merits of your case, as to those of any other case, whatever the color of your skin or the content of your character.” — From “Challenges to the Rule of Law: Or, Quod Licet Jovi Non Licet Bovi”, by Danny J. Boggs, Chief Judge in the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (2006)

Finally, additional examples of double standards appear in various other domains of life, in the actions of individuals and groups that practice various forms of favoritism and discrimination, such as sexism or racism. This involves judging or treating people differently based on certain traits , such as gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, age, social class, or socioeconomic status.

Note: when double standards are applied with regard to a particular trait, this is sometimes reflected in the way the double standards are referred to. This includes, for example, racial double standards , where people from different races are judged or treated differently , as well as gender-based double standards , where people of different genders are judged or treated differently , particularly when it comes to sexual behavior and relationships, a phenomenon that is also referred to as sexual double standards .

Who applies double standards

Double standards can be applied by individuals or groups, generally toward other individuals or groups. Examples of what double standards can look like in any of these situations include the following:

- An individual applying double standards toward individuals can involve, for example, a parent applying double standards toward their children, by treating similar behavior in an entirely different manner, based on which kid did it.

- An individual applying double standards toward groups can involve, for example, a manager applying double standards toward employees, by discriminating during the hiring process based on factors such as gender or race.

- A group applying double standards toward individuals can involve, for example, a media company applying double standards toward an activist, by attacking them for behavior that they praised in a different activist earlier on.

- A group applying double standards toward groups can involve, for example, a government applying double standards towards politicians as a whole, by being overly lenient toward them when it comes to criminal prosecution, compared to the treatment of regular citizens.

Note that when double standards are applied against a group, this can often take the form of double standards being applied against specific members of that group. Furthermore, when a group applies double standards toward others, it can either be because the group as a whole applies those double standards, or because key members of that group apply double standards on behalf of the group.

In addition, note that double standards can also be applied toward things other than individuals or groups. For example, someone might apply double standards when it comes to hobbies, by mocking a hobby for involving behaviors that this person thinks are fine when they’re a part of other hobbies. Similarly, someone might praise the attributes of a product made by a company that they like, even though this person criticizes those attributes when they appear in products made by competing companies.

Why people use double standards

People use double standards both intentionally and unintentionally, for various reasons.

Intentional use of double standards involves a conscious and active decision to apply them, and occurs primarily when people feel that the double standards in question could help them achieve some goal. This goal can involve things such as helping someone that they favor, hurting someone that they dislike, or making their arguments sound more persuasive.

Unintentional use of double standards doesn’t involve an active and conscious decision to apply them, though this doesn’t necessarily affect the outcome that using the double standard leads to. This unintentional use involves a failure to notice the double standard, and is generally driven by some motivation, often emotional in nature.

Accordingly, cognitive biases , which are systematic patterns of deviations from rationality, that occur due to the way our cognitive system works, often play a role when it comes to the unintentional use of double standards. A notable example of this is the confirmation bias , which is a cognitive bias that causes people to search for, favor, interpret, and recall information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs. This bias can lead people to apply double standards in many situations, such as by causing a person to judge the identical behavior of two individuals in a different manner, in order to confirm some preexisting impression of them.

When it comes to emotional motivators, there are many reasons why people apply double standards unintentionally. For example, people often apply double standards when it comes to how they judge their own behavior compared to the behavior of others , because they want to feel better about their actions. This means, for instance, that when it comes to judging some highly negative action, people might judge the action less harshly if they themself performed it, compared to if someone else had performed it, partly because they don’t want to feel bad about what they did.

Finally, note that cognitive biases and emotional motivations can also play a role when it comes to the intentional use of double standards. For example, someone experiencing the confirmation bias might be driven by the desire to prove that they were right in their assessment of a person, which could lead them to actively apply double standards, in a way that helps them do so.

Overall, people use double standards both intentionally and unintentionally. Intentional use of double standards is generally driven by the desire to achieve a certain outcome, while unintentional use of double standards is generally driven by emotional motivators, and often involves a failure to notice the double standards or understand that they’re problematic. However, both intentional and unintentional use of double standards can be emotional in nature, and both can lead to similar outcomes in practice.

Dealing with double standards

How to identify double standards.

To determine whether something that you’ve encountered is a double standard or not, there are two main things that you should consider:

- Are two (or more) things being treated differently?

- If there is a different treatment, is there a valid reason for it?

A double standard occurs when there is unequal treatment that’s not properly justified. This is important, because it means that unequal treatment of two or more things isn’t always a double standard, and can sometimes be reasonable.

For example, expecting better behavior from an adult than from a child is generally not a double standard, because the two types of individuals are different in a way that justifies the different expectations. Similarly, it can be reasonable to hold the actions of an elected official to a higher standard than those of a member of the public, because of the responsibility and power that they have.

As such, to make sure that some unequal treatment represents a double standard, ask yourself whether there is proper justification for this treatment. If necessary, you can also ask this of the person who is applying the unequal treatment, or of someone else who is relevant to the situation.

When doing this, it’s important to watch out for false equivalences , which occur when someone incorrectly asserts that two or more things are equivalent, simply because they share some characteristics, despite the fact that there are also notable differences between them. This is because false equivalences can cause you to mistakenly believe that a double standard is being applied, in situations where the things receiving unequal treatment are different in a way that merits this treatment.

When in doubt, apply the principle of charity , and don’t assume that a double standard is being used if there is a plausible alternative explanation, as long as it’s reasonable to do so. Furthermore, as long as it’s reasonable to do so, you should apply Hanlon’s razor , and operate under the assumption that the person using the double standard is doing so unintentionally.

How to respond to double standards

When responding to the use of double standards, the first step is to make sure that what you’re seeing is indeed a double standard, using the approach outlined in the previous section.

Then, the second step is often to ask the person who you believe is applying a double standard to explain their reasoning, if you haven’t already, and if doing so is reasonable in your circumstances.

This not only helps you determine whether they’re truly applying a double standard, but also gives you a better idea as to why they’re doing what they’re doing. Furthermore, in cases where the use of double standards is unintentional, this can give you the added advantage of possibly helping the person using the double standards realize that they’re doing so, particularly if you ask them to explain the rationale behind treating similar things in a different manner. In addition, in cases where the use of double standards is intentional, this can help you highlight the issues with that person’s reasoning.

Once you do this, you can then actively point out the logical and moral issues with the double standard, by showing that there is no proper justification for the unequal treatment in question. When doing this, you generally also want to help the person applying the double standard internalize the issue with what they’re doing, and negate their motivation for applying the double standard in the first place.

To achieve this, you will often need relevant debiasing techniques , and particularly when the double standards in question are the result of an underlying cognitive bias. For example, one bias that often plays a role when it comes to double standards is the empathy gap , which is a cognitive bias that makes it difficult for people to account for the manner in which differences in mental states affect the way that they and other people make decisions. If you see someone applying double standards as a result of this bias, you can ask them to think of situations where they experienced a similar double standard being applied toward them. Similarly, you can ask them to consider how they would feel someone applied a similar double standard toward them, or toward someone that they care about.

Finally, note that in some cases, you might be unable to get someone to stop applying a double standard, no matter what you do. If this happens, your response should depend on the circumstance at hand. For example, if the person in question is someone that you barely know or care about, you might choose to simply stop interacting with them, and let them know why. Conversely, if the person in question is your superior at work, you might choose to go to your company’s Human Resources department, in order to get them to resolve the issue.

Overall, when responding to the use of double standards, you should first ensure that you’re indeed dealing with a double standard, preferably by asking the person applying the standard to explain their reasoning. Then, you should point out the logical and moral issues with the double standard in question, help the person applying the standard internalize those issues, and negate their motivation for applying the standard in the first place. If none of these solutions work, you should pick an alternative one based on the circumstance, such as escalating the issue to someone who can resolve it, or cutting ties with the person who’s applying the double standard.

How to avoid applying double standards yourself

To avoid applying double standards yourself, you should make sure that whenever you treat two or more similar things differently, you have proper justification for doing so.

Though this might sound simple, it can often be difficult to do, especially in situations where you’re applying the double standards toward only one thing at a time. For example, this can involve treating someone harshly for making a mistake simply because you dislike them, in a situation where you haven’t seen anyone else make a similar mistake recently, which can make it difficult for you to notice that your response is too harsh.

As such, to avoid using double standards, whenever you find yourself thinking, speaking, or acting in an especially favorable or harsh manner toward someone or something, you should ask yourself to justify your reasoning, and consider whether you’ve treated similar things in a different manner under similar circumstances. The more significant the outcomes of your thoughts, statements, or actions, in terms of factors such as the impact they will have on others, the more important it is to do this.

If you find yourself applying a double standard, you can generally use the same techniques to resolve it as you would when dealing with someone else’s use of double standards. Most notably, this involves internalizing the logical and moral issues with your reasoning, and using various debiasing techniques to help mitigate the emotional drives and reasoning errors that cause you to apply double standards in the first place.

Note that you should be especially wary of applying double standards toward yourself compared to others. This is a common phenomenon that takes many forms, and occurs when you treat yourself more favorably or more harshly than you treat others, for no good reason.

When it comes to avoiding this issue, you should make sure to watch out for the egocentric bias , which is a cognitive bias that causes people to rely too heavily on their own point of view when they examine events in their life or when they try to see things from other people’s perspective. To deal with it, you can use appropriate debiasing techniques, such as considering how events that you’re in are perceived by other people, rather than just yourself, and trying to view those events from an external perspective.

Related concepts

Hypocrisy involves thinking, speaking, or acting in a way that contradicts one’s other thoughts, statements, or actions, especially when the individual in question is claiming to be superior in some way, such as morally.

Hypocrisy often involves the use of double standards. For example, a hypocrite might attack someone for acting a certain way, even though the hypocrite acted the same way when they were in a similar situation.

Hypocrisy is generally viewed negatively, though the issues associated with it can sometimes be mitigated if the hypocrite openly acknowledges their hypocrisy, and provides proper justification for it.

The etymology and history of the term ‘double standard’

The term ‘double standard’ was initially used to refer to the concept of bimetallism , which is the use of two metals (usually gold and silver) as monetary units, at a fixed ratio to each other. The term appears in writing in this sense as early as 1764, in the “ Ames Library Pamphlet Collection ” (Volume 16, Issues 1-9), which is a “collection of monographs related to Indian history and civilization, as well as the British experience in India, from the 18th through the 20th centuries”.

Later, people began using the term in other senses. For example, an 1834 article contains the following excerpt:

“The chief objection, however, to the use of oaths is, that it establishes a double standard of veracity: it recognizes the principle that it is possible by some human contrivance to increase the obligation to tell the truth; a principle in our opinion utterly false, and fraught with the most pernicious consequences.” — In an 1834 review of James Endell Tyler’s “Origin, Nature and History of Oaths”, written in The Law Magazine (Volume 13)

The use of the term in the moral sense, which is closer to how it’s used today, appeared at a later stage, with the earliest known instance of it in writing appearing in an 1872 article:

“Mrs. Butler traced the present inequality in the requirements of society with regard to male and female morality to the natural tendency of the stronger to obtain the victory of the weaker… This tendency has led men to impose a strict rule of continence and fidelity upon women, while it allowed license to their own sex… The Christian religion sets up an equal standard of morality for both sexes; it proclaims an absolute rule of personal purity on all alike, and as if to correct, with scourging, the falsehood of the existing double standard, Christ threw the whole weight of His authority into His rebukes of male profligacy, while with infinite tenderness, He restored the slave of man’s lust to her place among the free.” — From an 1872 article titled “Unjust Judgments on Subjects of Morality”, written in The Ecclesiastical Observer (Volume 25), in response to a related lecture by Mrs. Josephine Butler

Similar uses of the term appeared in writing later, in a number of places, such as the following:

“The double standard of morality owes its continued existence very greatly to the want of a common sentiment concerning morality on the part of men and women, especially in the more refined classes of society.” — From an 1886 article titled “The Double Standard of Morality”, in the “Friends’ Intelligencer United with the Friends’ Journal” (Volume 43)

The term remained in consistent use since then, often in the context of gender-based double standards, where men and women were suggested to be held to different standards of morality. For example, one book famously described this issue by saying that:

“What was right for Jack was wrong for Jill.” — From the 1928 book “The Warrior, the Woman, and the Christ: A Study of the Leadership of Christ” by Geoffrey Anketell Studdert Kennedy

Note : the term ‘double standard’ has also been used in a number of niche technical senses , with the earliest known usage appearing in 1751.

Summary and conclusions

- A double standard is a principle or policy that is applied in a different manner to similar things, without proper justification.

- Intentional use of double standards is generally driven by the desire to achieve a certain outcome, while unintentional use of double standards is generally driven by emotional motivators, and often involves a failure to notice the double standards or understand that they’re problematic.

- To determine whether something constitutes a double standard, you should determine whether there is unequal treatment involved, and whether there is proper justification for such treatment.

- To deal with the use of double standards, you can use various techniques, such as asking the person applying the double standards to explain the rationale behind their behavior, or asking them how they would feel if someone else applied similar double standards toward them.

Other articles you may find interesting:

- Kant's Categorical Imperative: Act the Way You Want Others to Act

- The Sagan Standard: Extraordinary Claims Require Extraordinary Evidence

- The Golden Rule: Treat Others the Way You Want to Be Treated

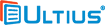

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

15 Double Standards Examples

Double standards are standards and principles that are applied to similar things in a differing manner, typically without proper justification.

For example, if a man can get away with behaving in a way that women cannot, then we have a gender-based double standard.

Given that double standards have high consequences, it’s important to recognize and challenge them (see also: hypocrisy examples ).

Below are 15 different ways and scenarios where double standards have infiltrated social practices.

Examples Of Double Standards

- Fathers vs Mothers: Fathers are praised for cooking dinner every now and then, while mothers are expected to do it all the time, without any praise.

- Body Image: Women’s body image tends to be scrutinized far more than men’s.

- Men’s vs Women’s Clothing: A male Australian television presenter wore the same suit every day for 12 months and no one noticed. He did it to highlight how men’s outfits are less scrutinized than women’s.

- Public Holidays: Christians get paid days off for their holidays (e.g. Christmas) while people of other religions don’t get the same courtesy.

- Men who Cry: Men are not allowed to cry or else the appear weak, while a crying woman is more accepted.

- Gendered Complaints: A woman who complains is considered ‘shrill’, while a man who complains is taken seriously.

- Assertive Women: Assertive women are seen as ‘bossy’ while assertiveness for men is often seen as a positive leadership trait.

- Journalism: A journalist who virtue signals online and is tough on a politician they don’t like, but provides softball questions to politicians they do like.

- Gendered Professions: A man who wants to be a nurse is ridiculed while a woman who wants to be a nurse is encouraged (and vice versa for other professions).

- Racial Profiling: Police racial profiling leads to the assumption that black men are up to no good while white people are giving the presumption of innocence.

- Attractive Clothing: A normatively attractive woman may get away with wearing a miniskirt, while women who are heavier may be criticized for the same outfit.

- Sons vs Daughters: A father who allows his 16 year old son to stay out until midnight but doesn’t let his daughter go out past 10pm.

- Female Broadcasters: A broadcasting corporation that fires the female on-air anchor when she turns 40, but keeps the male until retirement.

- Elites Get Away with It: A politician who conscripts working-class men to go to battle, but makes exceptions for the sons of the elites.

- Pay Gap: A company that pays some workers more for the same amount of work.

- The Bad Parent: Parents who tell their children not to do something, then they do it themselves.

15 Types of Double Standards

1. parenting.

Double standards within the parenting arena are plentiful. Fathers are praised for doing things that are simply expected of mothers!

In hetero partnerships, women are more likely to be seen as the caregiver and men as the breadwinner. These roles have been cemented throughout history and established standards for households.

If women work outside the home while their children are growing up, they are sometimes seen as unfit mothers and potentially as abandoning their “duties.”

Men, on the other hand, tend to be praised automatically for any slight effort or involvement with their kids as an aside to their full-time job.

2. Body Image

In recent years, the “dad bod” physique has been widely accepted and celebrated as an attractive body type for men.

The dad bod refers to a man is slightly overweight and not that muscular, or what is to be expected from a middle-aged man, (but applied to men of all age groups.)

Conversely, women do not typically receive the same latitude with their body and physique. Instead, they are encouraged and expected to stay slim at all stages and ages of life, including right after giving birth.

Failing to keep the standard of a preferred body image, women are at risk of facing criticisms that can have harmful effects and can be detrimental to mental health.

3. Employment

Race, religion, sexual orientation, and gender are just some of the unjustifiable grounds for double standards to exist and be executed in the workplace.

Whether it be opportunities for promotion or inclusion in company culture , employees have long been treated differently based on their identifying qualities as it relates to similar things.

For example, Christian-based holidays have been paid time-off for employees, while other religious celebrations are ignored and not afforded the same time off.

Although they are both religious holidays, they are perceived and treated with different levels of importance.

4. Expression of Emotions

Mental health issues affect all types of people from all walks of life.

Although it is a universal experience, how we express our emotions during mental health issues is judged differently depending on who is experiencing it. Often perpetuated in movies, the act of crying, for instance, can be perceived differently between men and women.

While women who openly cry and express their emotions may be wrongfully called “emotional” or “crazy”, it is still socially acceptable for them to cry and express emotions.

In comparison, men who show emotion, especially through crying, are seen as weak and not acting “like a man” in the way society expects them to.

5. Workplace Behaviours

Female bosses have a much harder time than male bosses in the workplace.

While men are often praised for being assertive and strong when making decisions, women who approach decision-making in the same way are perceived as “bossy” and “difficult.”

Although both leaders may strive to lead the company, women tend to be held back in their career progress based on these gender stereotypes and hurdles they face that their male counterparts do not.

6. News Outlets

Media, specifically the news, shares information from a particular perspective based on the motivations or often the political ideologies it identifies with. This can result in double standards in news reporting.

For example, protests and social movements are communicated differently depending on who is directly involved with them. That is, protests tend to be framed as rallies instead of riots if the news organization supports the protesters’ point of view.

Similar events, when initiated by those identifying with the opposite position, are condemned as radical and problematic, although their purpose is the same: to voice opinions and concerns about government.

7. Intimate Relationships

In a seemingly never-ending debate, social norms have positioned those identifying as men and those identifying as women in disparate positions when it comes to romantic intimacy.

Men, for instance, are accepted and encouraged to have multiple partners. Women, on the other hand, are stigmatized and shamed for having a history of multiple intimate partners, and in some cases judged for expressing a desire to have intimate relationships.

Although both men and women may be intimate with the same number of people, men are often congratulated while women are degraded for doing the same act: a double standard in plain sight.

Historically, there were socially agreed-upon careers paths for different genders to take on. A man who wants to be a nurse may be ridiculed while a woman who wants to be a nurse may be lauded.

When these paths are disrupted, people are often scrutinized or made fun of for stepping into a lane that “shouldn’t be theirs.”

Take for example the movie, Meet the Parents , Ben Stiller is identified as a nurse, a traditionally female-held job, and throughout the trilogy is belittled and made to appear as “weak” or “less than” other men with more masculine perceived jobs.

Similarly, women that work in trades are often discounted as not being strong enough.

9. Race and Culture

Race and culture are arguably the most pervasive double standards. It has not been uncommon throughout history to hold one race up to one standard and another to a completely different standard.

We have seen this between white colonialists and Indigenous people. Typically, white people in positions of power have held the standard of “good” and “authority,” while those in marginalized groups have been met with standards that associate them as problematic to society.

10. Pop Culture

The music industry is an instructive place to find double standards at work.

Oftentimes, female rappers and male rappers are perceived and responded to differently based on their choice of lyrics.

While they may both utilize innuendos or make reference to certain offhand subjects, female rappers are often judged more harshly and receive backlash for including this type of content in their music, while music of the same nature by their male counterparts is accepted, and to a degree, celebrated.

The legal system, while intentioned to apply universal law to all, often contains double standards.

Although all parties should stand equal before the law, it is very common to see judges who do not apply the same standards to all people.

As judges are humans, there is a chance that they may be given different sentencing based on different judge’s subjective biases, or favoritism that is based purely on socioeconomics, ethnicity, gender, or religion.

Take, for example, the US supreme court, which (depending on the court’s makeup) will often interpret law in ways that favors one political leaning over another.

The same goes for jury trials in court because of implicit or subconscious biases: see the movie 12 Angry Men , to get a better sense of prejudicial attitudes in court trials.

12. Attraction

Double standards are also at work in the realm of dating and levels of attraction.

Society accepts people in certain forms but uses different levels of judgment for others in a similar situation. For instance, it is only okay for a man to flirt with someone if he fits the image of what society deems as attractive.

If an un-attractive man hits on someone, it is seen as “creepy” or “unwanted.”

Similarly, revealing clothes on a woman who is an ideal beauty type is accepted, but a woman who is heavier in weight wearing the same thing is perceived as unattractive.

13. Entertainment

Movies and video games are both popular forms of entertainment that many enjoy around the world.

Aside from the positive qualities of enjoyment, it’s easy to find double standards at play without searching too far.

For instance, in the Marvel universe, a brand that spans across film, and video games, as well as its original home in comic books, women and men are presented with different standards of portrayal although they are both superheroes.

For instance, female superheroes are supposed to be scantily clad, while their male counterparts are more likely to be fully clothed and in less revealing outfits.

Even the act of aging is not immune to the judgments of double standards in our society.

Growing older is, in general, celebrated through various kinds of milestones and wisdom that is earned in older years.

Unfortunately, the effects of aging are not perceived equally; especially as it relates to the genders.

That is, age acts as an instrument of oppression: it enhances a man’s overall image but conversely older women are seen as outdated.

We don’t have to look any farther than beauty ideals to see this at work: older men are “silver foxes” but older women with silver hair are dismissed .

15. Social Interactions

People form bonds and relationships through communication. We express, listen, speak, and open our minds to others in an effort to form meaningful relationships.

Unfortunately, the way we choose to speak to one another is not always judged equally by society.

For instance, if a group of men are communicating in a vulgar or explicit manner it is seen as normal, but if a group of women were doing the same thing it would be frowned upon and perceived as “un-ladylike.”

Similarly, gossiping is usually perceived as more of a woman’s form of communication, but men who share information about others is informative.

In order for meaningful and authentic change to happen, we must recognize the double standards that we participate in whether consciously or unconciously.

It is not just to treat someone different in similar situations based on preconceived notions about them. If you find yourself in a moment of judgement against someone, stop and reflect on if that judgement is based on factual evidence or if you may be treating someone unfairly based on their differences.

Dalia Yashinsky (MA, Phil)

Dalia Yashinsky is a freelance academic writer. She graduated with her Bachelor's (with Honors) from Queen's University in Kingston Ontario in 2015. She then got her Master's Degree in philosophy, also from Queen's University, in 2017.

- Dalia Yashinsky (MA, Phil) #molongui-disabled-link Third Variable Problem: Definition & 10 Examples

- Dalia Yashinsky (MA, Phil) #molongui-disabled-link 20 Standardized Tests Pros And Cons

- Dalia Yashinsky (MA, Phil) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Examples of Inclusive Language

- Dalia Yashinsky (MA, Phil) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Denying the Antecedent Examples (Logical Fallacy)

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Journal of Population Sciences

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2020

Thinking as the others do: persistence and conformity of sexual double standard among young Italians

- Matteo Migheli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5051-4462 1 &

- Chiara Pronzato 1 , 2 , 3

Genus volume 76 , Article number: 25 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

7637 Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details

The double standard represents a standard of good behaviour that, unfairly, some people are expected to follow or achieve, but others are not. Once neglected by social scientists, the double standard in sexual attitudes has become more and more studied. In this paper, we inquire about the existence of the double standard in opinions regarding peers’ sexual behaviours and study its determinants. What makes young people judge the sexual behaviour of women in a more conservative way than that of men? The paper uses data collected from Italian university students, who are asked to express their (dis)approval of a series of sexual behaviours, considering peers of either gender participating in those behaviours. The results show that the double standard exists and has been persistent amid Italian undergraduate students over the last 20 years, and that the cultural context matters more than the family in shaping students’ beliefs.

Introduction

The double standard represents a standard of good behaviour that, unfairly, some people are expected to follow or achieve, but others are not. Once neglected by social scientists (Reiss, 1956 ), the double standard (DS) regarding sexual attitudes and behaviours, and the opinions and judgements expressed about them, has become more and more studied. Following Bordini and Sperb ( 2013 ), we may define the sexual double standard as the existence of different attitudes, viewpoints and judgements between men and women about sexual habits, behaviours and tendencies. Indeed, the literature shows that women tend to stick to traditional sexual paradigms from young ages (Bordini and Sperb, 2013 and Kukulj & Keresteš, 2019 ), for example, refusing experimentation with sexual intercourse much more than men do (Lai & Hynie, 2011 ). As such, the sexual DS represents a limitation to women’s freedom and therefore is something that societies should carefully consider both as an indicator of distance from gender equality (Allison & Risman, 2013 ) and as a way to promote the latter by reducing the former (Bobbitt-Zeher, 2011 ). Moreover, sexual prejudices have other negative effects on both social and economic terms. They are a determinant of aggressiveness against sexual minorities (Parrott & Zeichner, 2005 ; Parrott et al., 2011 ), lead to occupational segregation (Plug et al., 2014 ) and ultimately decrease economic growth, as they engender an inefficient allocation of resources through discrimination (Berggren & Elinder, 2012 ).

Empirical evidence shows that the sexual DS is present already in adolescence (Kreager et al., 2016 ), suggesting that effective policies to reduce it should target people from a young age. There are thus several reasons to study the DS, and in particular its determinants and the possible actions which may be taken to reduce it. Jackson and Cram ( 2003 ) show that the DS may be disrupted using, for instance, focus groups with young women (aged 16–18), where the language of the sexual DS is challenged and sexual desires are freely presented and discussed by the participants.

In this paper, we inquire the existence of DS in opinions about peers’ sexual behaviours and study its determinants. The paper uses data collected from Italian university students, who are asked to express their (dis)approval of a series of sexual behaviours, considering peers of either gender holding those behaviours. The survey reports such information for both 2000 and 2017, allowing the observation of the evolution of sexual opinions and of the DS over time. Concerning the determinants of this phenomenon, the paper investigates how family and contextual characteristics may influence students’ answers. The results show that the DS exists and has been persistent among Italian undergraduate students over the period considered and that the cultural context matters more than the familial one in shaping students’ beliefs.

As Dalla Zuanna et al. ( 2019 ), this paper explores the changes in sexual behaviours of girls and boys and the related opinions, using the same data. Their focus is on the convergence between males and females’ opinions over time, which is due to the feminisation of male sexual behaviour within the couple (escapades become less acceptable also for boys) and to the masculinisation of female sexual behaviour outside the couple (having more partners becomes more acceptable also for girls). Instead, the present study contributes to the literature by studying the determinants of the individual asymmetry in judging girls and boys and, in particular, the influence exerted by the reference cultural context.

Related literature

Scholars have paid much attention to the sexual opinions and attitudes of undergraduate students over the last decades. In particular, many studies focus on the existence of a DS in both behaviours and opinions. The extant literature shows that behaviours and opinions have evolved together with the existence of the DS, which has never disappeared. Ferrell et al. ( 1977 ) consider sexual attitudes and behaviours in a sample of college students in the US between 1967 and 1974; their findings show the presence of strong DS about premarital sex in all the years considered. Scott ( 1998 ), using a similar population (i.e. college students) confirms these results for both the USA and the UK, providing evidence for the existence of the DS at young ages and in highly educated people. A recent review of the literature on the DS produced in the first decade of this century (Bordini & Sperb, 2013 ) highlights that several sexual behaviours are evaluated differently for men and women, while premarital sex and sexual intercourse outside committed relationships are more accepted for both genders now than in the past. Behaviours, norms and attitudes towards them are part of the wider and more general domain of culture Footnote 1 , which includes traits that may shape how people behave, think and judge others’ choices. Culture is also a major factor that supports the existence of the sexual DS: in most countries, the role of women is subordinated to that of men and such a subordination included sexual initiative, with more active roles attributed to men and women assigned to more passive roles. In addition, Sakaluk and Milhausen ( 2012 ) show not only that the DS exists but also that it is stronger in the male than in the female population. More recently, Emmerink et al. ( 2016 ) find that men endorse sexual DS much more than women, probably as a consequence of the traditional sexual roles assigned to the two genders. Endendijk et al. ( 2020 ) review 99 studies through a meta-analysis and confirm that, where differences between gender roles are bigger, the DS is stronger because men have more power than women. That part of culture, which refers to gender roles, will be inquired in the analysis, as one of the aspects of interest.

The DS in sexual attitudes, behaviours and opinions is indeed pervasive, starting from the very beginning of the sexual act, i.e. the approach to the other person, as Reid et al. ( 2011 ) show in their study of hooking up among US college students. Premarital sexual intercourse was the first topic to be studied (Reiss, 1956 ) where the DS emerges strongly; several other works have highlighted that it is more accepted for males than for females, in accordance with the dominant cultural stereotypes (Wilson & Medora, 1990 ; Ramos et al., 2005 ; England & Bearak, 2014 ). Another related attitude involves early sexual intercourse, which is socially stigmatised in young women, but not in young men (McCarthy & Bodnar, 2005 ; Kreager et al., 2016 ). However, many other fields of sexuality are affected by the presence of a DS, the number of sexual partners being another relevant example (Ramos et al., 2005 ; Bordini & Sperb, 2013 ; Sprecher et al., 2013 ). Very recently, Marks et al. ( 2019 ) asked a sample of about 5000 US young people, aged 18–35, to evaluate the sexual behaviour of one of their friends whose sexual life they knew. The results show the emergence of a strong DS, in particular with respect to the number of sexual partners, with women evaluated worse than men as the number of partners increases. Also, the provision of condoms by women is generally seen scarcely convenient, as people in general (Smith et al., 2008 ) and even women in particular (Hynie & Lydon, 1995 ) believe that it is more a male than a female matter. Footnote 2 Jozkowski et al. ( 2017 ) show that endorsing a sexual DS also affects sexual consent communication between college students, engendering problems of misunderstanding and influencing the perception of sexual violence.

Given the focus of this paper, a digression on the so-called reverse DS is needed, with particular reference to same-sex sexual behaviours, as this is the case, where the phenomenon is most often observed. A reverse DS (i.e. more permissive attitudes towards women than towards men) is sometimes found, and generally emerges when considering same-sex sexual behaviours: here, sexual relationships between men are generally stigmatised more than between women (Siegel & Meunier, 2019 ). Lesbian sexual relations generally receive more positive evaluations, possibly because they are considered more erotic than sexual relations between men (Louderback and Whitley Jr., 1997 ). Herek ( 2000 ) found that heterosexual women hold similar attitudes toward both gay men and lesbians, whilst heterosexual men tend to accept lesbians more than gay men. Of course, such a reversion in the DS may depend on the norms that are typical of heterosexuality; as mentioned before, the DS exists because men and women have different views and attitudes towards sexual matters. In particular, the traditionally preeminent role of men and the subordinate role of women may affect how the two genders perceive and evaluate same-sex sexual behaviours. When the last is viewed as something that hinders masculinity (Javaid, 2018 ), the emergence of a reversed DS, when same-sex sexuality is concerned, may simply be the specular image of the DS existing in heterosexual attitudes and behaviours.

One may wonder why the sexual DS is so persistent over time. A first answer is that it is rooted in the cultural values of most modern societies, where the role of women is still seen as a subaltern to that of men. MacCorquodale ( 1989 ) highlights that the gender roles learnt at young ages are relevant in shaping gendered perceptions of sexual attitudes. Indeed, women with more egalitarian gender role attitudes and more ‘masculine’ personality traits are more prone to have multiple partners and exhibit more ‘masculine’ sexual behaviours and attitudes (Lucke, 1998 ). The culture of virginity, which has seen it as a positive trait for young women over centuries, is responsible for the fact that young women evaluate female virginity much more positively than men do with male virginity (Sprecher & Regan, 1996 ). Always considering culture, Crawford and Popp ( 2003 ) highlight that the sexual DS is a local construction, as it depends on cultural stereotypes that vary with place. This means also that while the DS is present almost everywhere, there may be differences in judgements from a place to another, due to differences in the prevalent local cultures. Such a variation may weaken the effectiveness of large-scale policies aimed at fighting the sexual DS. Nevertheless, as the literature surveyed in what follows shows, most of the existing studies identify many traits and trends that are common to different countries (e.g. New Zealand, Turkey, UK and USA) and, therefore, cultures. Such regularities support (at least partially) the external validity of studies conducted within a specific cultural context. Yost and Zurbriggen ( 2006 ) show that unrestricted sociosexual orientation (i.e. willingness to engage in sexual relations without romantic involvement) correlates positively with premarital sex and the number of sexual partners; they also highlight the importance of the local sociocultural context for these aspects. However, for men, such an orientation correlates positively also with more conservative attitudes towards women, thus reinforcing the sexual DS. Eşsizoğlu et al. ( 2011 ) study a sample of Turkish undergraduate students, finding that traditional gender roles affect the attitude towards premarital sex: more conservative individuals—i.e. those who stick to more traditional gender roles—stigmatise premarital and early sex more than those with a more progressive vision do. Analysing the answers of US undergraduate students, Zaikman and Marks ( 2014 ) find that US individuals with more sexist attitudes also exhibit stronger DS in their evaluations of peers with multiple sexual partners.

Fasula et al. ( 2014 ) highlight the role of racial and gender inequality in explaining the existence of the sexual DS in the USA; in particular, they claim that the DS is a consequence of such inequalities. Similar conclusions are reached by Lefkowitz et al. ( 2014 ): US undergraduate students who exhibit conventional stereotyped beliefs about gender roles endorse a stronger DS regarding the use of condoms by women and for multi-partner relations than students with a more egalitarian vision of gender roles. In the same vein, Zaikman et al. ( 2016 ) interview 483 US adults, proposing examples of gender role violations regarding sexual behaviours; their results show the emergence of a stronger DS when traditional roles are violated than when they are observed. All these studies relate the existence and the strength of a sexual DS surrounding the individual image of gender roles; thus, in a sense, the same individual is observed from two different perspectives. While individual preferences and attitudes may well depend on those diffused in the environment where the person was (and is) socialised, the individual dimension does not shed any light on environmental influence on one’s preferences and attitudes.