Download the Data

Download the data that appear on the College Scorecard, as well as supporting data on student completion, debt and repayment, earnings, and more.

This data was last updated May 6, 2024 .

All Data Files Download (.zip, 436 MB)

- Institution-level data files for 1996-97 through 2021-22 containing aggregate data for each institution. Includes information on institutional characteristics, enrollment, student aid, costs, and student outcomes.

- Field of study-level data files for the pooled 2014-15, 2015-16 award years through the pooled 2018-19, 2019-20 award years containing data at the credential level and 4-digit CIP code combination for each institution. Includes information on cumulative debt at graduation and earnings one year after graduation.

- Crosswalk files for 2000-01 through 2020-21 that link the Department’s OPEID with an IPEDS UNITID for each institution.

Most Recent Institution-Level Data

Most recent data by field of study.

Looking for help? Visit StackExchange or email the help desk at [email protected] . For inquiries by members of the press, please contact [email protected] .

The Question of College Completion Rates

- Posted December 9, 2021

- By Jill Anderson

- College Access and Success

- Higher Education Leadership

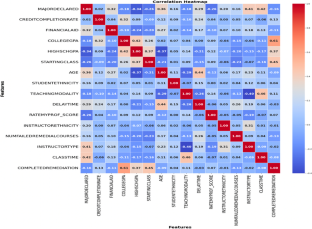

For the past few decades, college completion rates have slowly been going up. Economist Jeff Denning wanted to know why. As part of recent research, Why are College Completion Rates Increasing , Denning and co-researchers dug deep to understand this phenomenon. Denning, a Brigham Young University associate professor, says the reason isn’t what you might suspect like an increase in college enrollments or that students are studying more. Instead, his research shows that grade inflation is driving the change.

"[Whether it is] good or bad to inflate grades, I think is an open question," says Denning. "We show one side of this, which is: If you had told me before I wrote this paper, 'We have this policy lever, it's going to increase graduation [rates] and it's not going to cost any money, basically,' I'd be pretty interested in that policy lever."

In this episode, Denning provides insight into how he conducted this research and also what this might mean for higher education.

TRANSCRIPT:

Jill Anderson: I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast. Economist Jeff Denning set out to better understand why college completion rates are increasing. What he didn't expect to discover is the reason why. He says it's not an increase in enrollments or even student characteristics driving this increase, but actually great inflation.

As part of his research, he looked at many different factors to attribute this change. I spoke to Jeff and wanted to know what this might mean and why he started looking at college completion rates in the first place.

Jeff Denning: There was a very famous paper, My Circles by [Don Livine Hymantan 00:00:50] that he showed from the 1970s to the 1990s college completion rates declined. That is if you went to college, how often did you complete? And that actually was declining from the seventies to the nineties.

And so that was a fact that I knew and that other researchers knew. And then I saw in more recent data, I saw that college completion rates had been increasing. Starting in about the nineties, they started increasing and suddenly over that timeframe. And so we said, "Oh, that's interesting, that's a new fact. And let's see if we can explain it."

One thing I would say is college graduation rates are increasingly show, but they're still low. By the end of our period they're almost 60%. So it's not like everyone who goes to college completes, it's just slightly more now are completing than they used to.

Jill Anderson: It's something like about a 7% increases what you saw?

Jeff Denning: That's right. So seven percentage point increase relative to a baseline of 52 percentage points. So a reasonably sized increase in graduation rates.

Jill Anderson: When you really read this and you go through it, it's shocking how much data you looked at to come to your conclusion, which was that there's some grade inflation potentially happening.

So why don't you talk to me a little bit about how you did the research came to this realization that grade inflation is part of this?

Jeff Denning: Yeah, so we started with the fact completion rates are up. Why is that? Our starting place was to use the methodology of this earlier paper and consider factors that they considered. Could those explain it statistically?

So they come away saying one of the reasons that completion rates declined is that students were going to different colleges that had lower completion rates and that there was less support for higher education as measured by student faculty ratios.

So we looked at those trends and other trends and it turns out none of those trends would predict increasing graduation rates. So students are going to the same types of colleges as they were basically, they didn't change dramatically the distribution of colleges. Colleges Weren't getting more resources per student or anything like that. It had about the same amount of resources per student, maybe a little worse, but not markedly different.

We use evidence from other papers that show students are more likely to be employed for wages, not working at school, but working to make money. So that would make you think that that's not a good thing for graduation necessarily. Prices are up, tuition is up over this time. I think that might affect it. That's going kind of the wrong way as well. Students are studying less over time.

There's another paper that shows that. We started looking at all these different trends and we're like, "Oh, these are going the wrong way. They're not going to help us explain why college completion rates are increasing." But we noticed that grades were up. So first year grades were up by a fair amount. And so we're like, "Oh, well, grades are correlated with whether or not you finish college."

And so why are grades up? That might be our story. And so then we said, "Okay, why are grades up? Well, our students more prepared for college." And so we took data from some national surveys. We took data from several colleges and we saw after we used statistical methods to see comparing people who were at a similar level of preparation over time, that is that they have the same SAT score for instance, did they have higher grades in the later years? And they did. So we couldn't explain the increase in GPA by increases in preparation.

Like I said, students were studying less, so that's not explaining it. My favorite piece of evidence comes from a single university, which we are allowed to call Public Liberal Arts College. At this Public Liberal Arts College. We have data on a lot of things, but importantly, we have your grade in the class, as well as your final exam score.

And we showed that people's grades are going up over time, even after we compare people with the same final exam score. So two people in subsequent years, they have the same exact score on the final exam, but one just comes later. The person that comes later to that school, we would predict, have a higher GPA in that class.

And even further we found for some classes, they offered the exact same tests over time. And so we could compare people who got the exact same score on the exact same test and see, did they have higher grades if they were coming at the later part of the sample?

And the answer is, yes. So over time people were having higher grades, even though they presumably learned the same amount of stuff, they had the same score on the final exam. So I think that is our strongest evidence for great inflation at that particular college, but the trends in graduation and GPA at that college mirror what we see and more nationally representative data as well.

Jill Anderson: So people are going to hear this and they're going to say, "Does this mean college has gotten easier?"

Jeff Denning: Yeah. That's a great question. Our answer would be, it seems like it a little bit. Our next question is, is that a bad thing or a good thing? We set how hard college was. I don't know when in the seventies, fifties, whatever. And the question is, is that the right level of difficulty. Our paper is one that suggests like, well, there are benefits to making college a little bit easier. More people graduate, college graduation is a good thing.

It helps people in a lot of ways. It helps them earn higher wages, et cetera. And so this seems to be a benefit. There may be costs as well, but this seems to be a benefit of making it easier for students to graduate.

Jill Anderson: What do you think that this might say in the larger discussion about the value of college? Does it change it in any way?

Jeff Denning: People often ask, this is a great next question, right? Like, "Oh, so a college degree, somehow devalued." Not our paper, but other papers have shown that the college wage premium, that is how much more you make if you have a college degree compared to someone who doesn't, it's very high and has stayed pretty constant over the last 10 or 20 years, I don't remember exactly how long, but for the last little while it's very high and it's not shrinking, it's not getting worse.

So people who go to college have higher wages, and there's a lot of good evidence to suggest that college has a causal effect on wages. It increases wages. So I think the returns to college are very strong, certainly on average. You're right to wonder, you can imagine if college changed dramatically or got way, way easier, then you might be worried about it. That doesn't seem to have played out, at least in aggregate trends that we see in the data.

Jill Anderson: What about higher ed leaders and people working in higher education? How can they take this research and use it, or think about what their goals are for students?

Jeff Denning: I think the first thing that we would say is that grades are a policy tool. That this is something that they can use to affect whether or not students graduate. It can affect other things too, like the incentive to study and that sort of thing can be affected by grades. So you want to think about grades, not as just kind of arriving like the dew or something, but something that you can actually affect and would have consequences for your students. So that's the first thing.

Is it good or bad to inflate grades, I think is an open question. We show one side of this, which is: If you had told me before I wrote this paper, "We have this policy lever, it's going to increase graduation [rates] and it's not going to cost any money, basically," I'd be pretty interested in that policy lever.

And that's basically what we found. Now, you might think there are trade offs in terms of student effort or signals to employers or that sort of thing. Our paper, I hope is one in a series of papers, that maybe other people will write, or that we'll write that say, "What's the right level here. What's the right level of grades that we should be giving out."

Jill Anderson: I don't know if there's any explanation you can give in practice. Do faculty members even realize that they're inflating the grade or is it just something that happens?

Jeff Denning: People mean different things by great inflation, but what we mean by great inflation is: Are grades higher for the same level of understanding or something like that over time, right? Could people talk about inflation across disciplines or something? We're talking about over time. So that's how we define it. Are grades higher than they were before, conditional on the same amount of knowledge or competency?

Now, why is this happening? I think is a really interesting question. When people ask me this, I usually answer it with a question is, "Why didn't it happen earlier?" Who was the constituency for tougher grades? As a professor I can tell you, it's not my students. They're not asking me to grade harsher, college administrators often are, they're interested in increasing graduation rates. And so they're I think skeptical of giving out really low grades.

So they're not really rooting for low grades often. Teachers who give out lower grades are likely to get lower student evaluations, which are important for decisions about promotion and that sort of thing.

So, there's not really an obvious constituency for lower grades within the university. So there are also other speculative reasons. I think there's some evidence to suggest adjuncts tend to give out higher grades than tenure track faculty.

There's a lot more information about professors and classes online than there used to be so you can perhaps there's incentives to find the teacher who will give higher grades or that sort of thing, or pressures to compete that way. We don't really know, but there doesn't seem to be a lot of incentives for lower grades that I can see in higher education.

Jill Anderson: Well, thank you so much Jeff.

Jeff Denning: Thanks for having me.

Jill Anderson: Jeff Denning is an associate professor at Brigham Young University. He's the lead researcher of, why have college completion rates increased, to be published in the American Economic Journal. I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast produced by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Higher Education's Resistance to Change

Visiting Professor Brian Rosenberg addresses the cultural and structural factors that impede significant transformations in higher education

College Admissions During COVID

Is the College Enrollment Decline Really a Crisis?

Access & Affordability

College completion rates highest in recent years, report finds.

A new report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center has found that 62.2 percent of first-time students who started college in fall 2015 graduated by spring 2021, the highest six-year completion rate in recent years. According to the Lumina Foundation , the report is perhaps the last snapshot of higher education trends before COVID-19, as most of the 2015 cohort graduated before 2020.

“What we can learn from this cohort is going to be really important, because it’s going to be the cohort we look back to, comparing back to an age of stable inequality, versus severely disrupted and impacted inequality,” Dr. Stell M. Flores, an associate professor and director at the University of Texas’s Education Research Center, explained to Diverse Issues in Higher Education .

Variation across institution types

According to Higher Ed Dive , the 2015 cohort’s completion rate is up 1.2 percentage points over that of the 2014 cohort and marks the third straight year of completion rates above 60 percent.

Compared with the year prior, completion rates rose across all institution types, including community colleges, public colleges, private nonprofit colleges, and private for-profit colleges. Students who started at community college had the largest completion rate increase, at 1.5 percentage points. However, compared with students at other types of institutions, they still had the lowest completion rate, at 42.2 percent. In contrast, four-year private nonprofit and public universities had the highest completion rate at 78.3 percent and 69 percent, respectively. The rate at four-year for-profit colleges was 46.4 percent.

Especially large increase for Black students

The report also showed racial disparities in college completion. “Reflecting other societal and educational inequities, Black, Hispanic, and Native American students are less likely to complete college degrees than white and Asian students,” Amy Feygin, principal researcher at American Institutes for Research, told Inside Higher Ed . However, Black students had the largest completion rate increase—nearly two percentage points—among all racial and ethnic groups studied. White and Latinx students’ completion rates also increased, while Asian students’ completion rates held steady.

Analyzing completion by age group, researchers found that adult learners (students who first entered college at age 24 and older) had the highest completion rate increase, although traditional college-age students (students who entered college at 20 years old or younger) continued to have higher completion rates than older students.

For Doug Shapiro, executive director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, “This broad measure of performance for higher education as a nationwide system…shows long-term improvements for students and colleges alike.” The Lumina Foundation attributes the results to several factors, including “more students starting their educational journeys at bachelor’s-granting institutions, and, possibly, better academic and financial support for students, especially students of color.”

A dip on the horizon?

Feygin, however, predicts that completion rates will soon trend downward, reflecting pandemic-related enrollment loss, especially among Black and Native American male students.

The report also noted worrisome signs, including the high rate of students “stopping out” (temporarily leaving school) and withdrawing from college permanently due to economic and academic hurdles. Increasing investments in financial, academic, and basic needs support is, according to Feygin, the best way to mitigate these downward trends.

Topics in this story

‘put the money to good use’: revisiting mackenzie scott’s transformative unrestricted gifts to hbcus.

More than a year after MacKenzie Scott donated $560 million in unrestricted funds to 23 public and private historically Black colleges and universities, the gifts have added resilience to minority-serving institutions confronting existential threats.

Sign up for our weekly email

- Please provide your first and last name. * First name Last name

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

College completion rates are up for all Americans, but racial gaps persist

Please try again

Students’ race and ethnicity affect their chances of earning a college degree, according to several new reports on higher education released in January and February 2023. However, the picture that emerges depends on the lens you use. College degrees are increasing among all racial and ethnic groups, but white and Asian Americans are far more likely to hold a college degree or earn one than Black, Hispanic or Native Americans.

Earning a college degree involves two steps: starting college and finishing college. Before the pandemic, white, Black and Hispanic Americans were enrolling in college at about the same rates, especially when unemployment was high and jobs were hard to find. (Asian Americans enrolled in college at much higher rates.) The bigger distinction is that once a student has started college, the likelihood of making it through the coursework and tuition payments and ultimately earning a degree varies so much by race and ethnicity.

First, let’s begin with enrollment. There are two ways to look at this. One is to see how the demographic makeup of college campuses has changed over time, becoming less white and more Hispanic. The pie charts below were produced in January by the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that provides data reporting services to colleges. In conjunction with these services, it monitors trends in higher education by aggregating the data submitted by more than 3,600 institutions, representing 97 percent of the students at the nation’s degree-granting colleges and universities. Earlier this year, the organization launched a DEI Data Lab site to put a spotlight on how college enrollment, persistence and completion vary by race and ethnicity.

In 2011, as the pie chart on the left shows, more than 60 percent of the nation’s 20.6 million college students were white, according to an estimate by the National Student Clearinghouse. By 2020, the year represented by the pie chart on the right, the total number of college students had fallen to 17.8 million and the share of white students had dropped by almost 9 percentage points to 52 percent, still a majority. During the same period, the share of Hispanic students grew from 14 percent to 21 percent, and the share of Black students remained constant at just under 14 percent. Asian students increased from 5 to 7 percent of the college population. This represents all undergraduate college students, both younger students entering straight after high school and older nontraditional students, studying full-time and part-time, and attending both four-year universities and two-year colleges.

The 2011 figures are rough estimates because only one out of five colleges reported race and ethnicity of students to the Clearinghouse. Today, more than three out of five colleges report on the race and ethnicity of their students to the Clearinghouse. (For the original version of this pie chart, click here .)

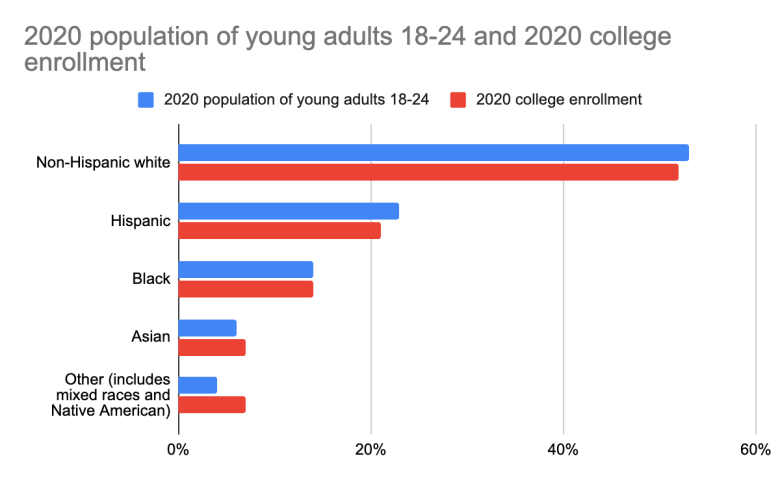

How should we think about these college enrollment numbers? Do they largely mirror each racial and ethnic group’s share of the population? I was surprised to learn that the answer is yes – with a few caveats. Asian Americans are slightly overrepresented on college campuses and Hispanic Americans are slightly underrepresented.

I created this chart below, comparing the National Student Clearinghouse’s college enrollment data for 2020 with the young adult population, as reported by the U.S Census, so you can see how closely college enrollment tracks actual demographics.

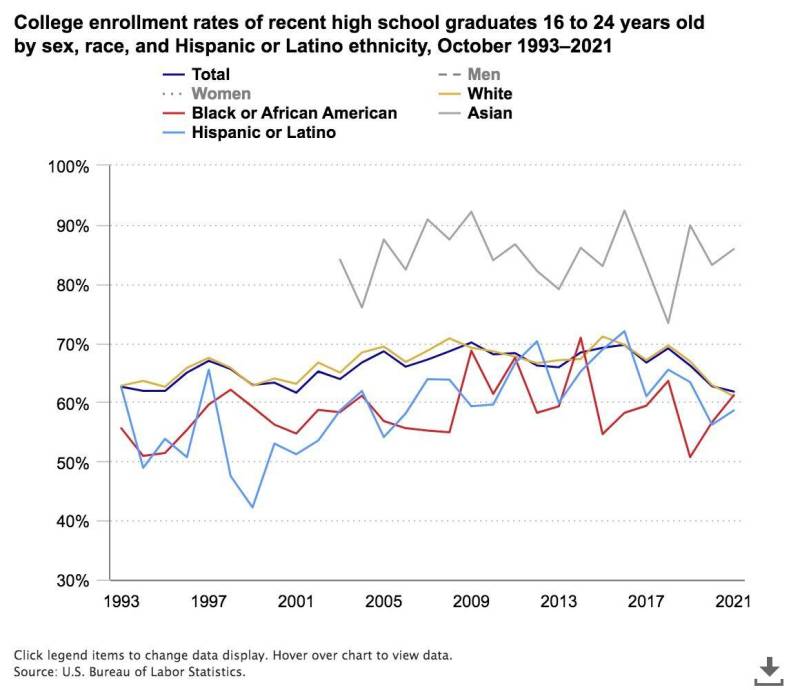

Another way to look at college enrollment is to see how many young adults enroll in college. The chart below, by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows that the college enrollment rates of Black and Hispanic young adults improved after the 2008 recession, and approached the college going rate of white Americans. Roughly 60 percent of young Black, Hispanic and white Americans are trying for a college degree. The college going rate for Asian Americans is much higher; more than 80 percent enroll. The zigs and zags in this chart show how college going among Hispanic and Black Americans is influenced by business cycles.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics obtains enrollment data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of households conducted by the Bureau of Census. (Here is the chart on the BLS site .)

When jobs are plentiful, many low-income students may join the labor force and defer their higher education. That especially reduces enrollments among Black and Hispanic young adults, among whom poverty rates are higher. When unemployment is high, more young adults enroll at college, particularly at two-year community colleges. Most recently, during the pandemic, many young Americans deferred college to help support or take care of their families. Some students chose to wait until in-person classes resumed.

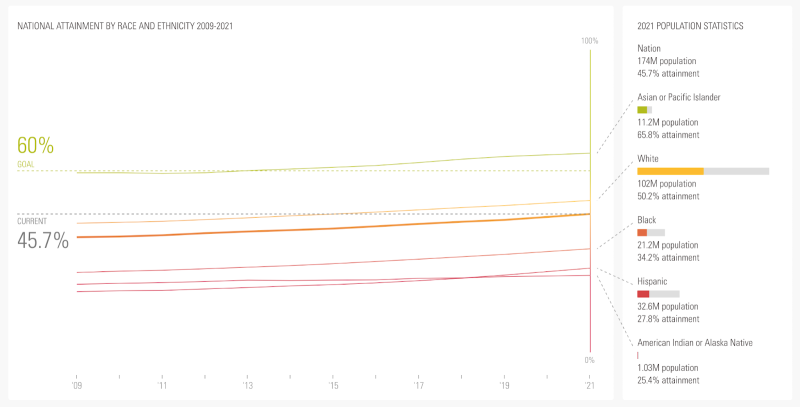

Going to college is one thing; finishing it is another. This fourth chart, produced by the Lumina Foundation, shows that over time, more Americans of every race and ethnicity are earning college degrees. The Lumina Foundation is a private foundation that seeks to increase the number of adults with college degrees and other credentials, and was formed through the sale to Sallie Mae of USA Group's assets that were used to create and collect monthly payments on student loans.* It is also among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.

Share of adult population, ages 25-64, with college degrees

This chart above, originally published here on Jan. 31, is based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. It tracks the percentage of adults 25 to 64 with two-year associate and four-year bachelor’s degrees. The share of Americans with a college degree rose from 38 percent in 2009 to nearly 46 percent in 2021 – an increase of eight percentage points.

Every race and ethnicity saw gains. The eight-percentage point gain was the same for both Black and white adults.

But racial gaps continue. In 2021, there remained an enormous 40 percentage point difference between Asian American adults, among whom 66 percent have a college degree, and Native American adults, among whom only 25 percent have a college degree. Among Black adults, 34 percent have college degrees. Among Hispanic adults, it’s 28 percent and among white adults, it’s 50 percent.

Improvements in college attainment can seem slow because graduation rates are much lower among Americans over 35. It takes years for higher college graduation rates among younger adults to raise overall college numbers. College attainment rates have jumped the fastest among young Hispanic adults under age 35, rising from below 20 percent in 2009 to above 30 percent in 2021. Courtney Brown, the chief data and research officer at Lumina, credits a variety of support programs, from tutoring to food pantries, and the convenience of online courses to explain why more young people are graduating, despite rising tuition costs. “Colleges are trying to serve students better,” said Brown. “Even the way they staff colleges, not all on getting enrollments but having more success coaches available and counselors helping students get to the finish line.”

Still, Brown acknowledges that it’s been difficult to make a dent in the stubborn gaps in college attainment between people of different races and ethnicities. “Unfortunately, everyone is increasing,” Brown said. “And so we are not seeing those gaps reduced.”

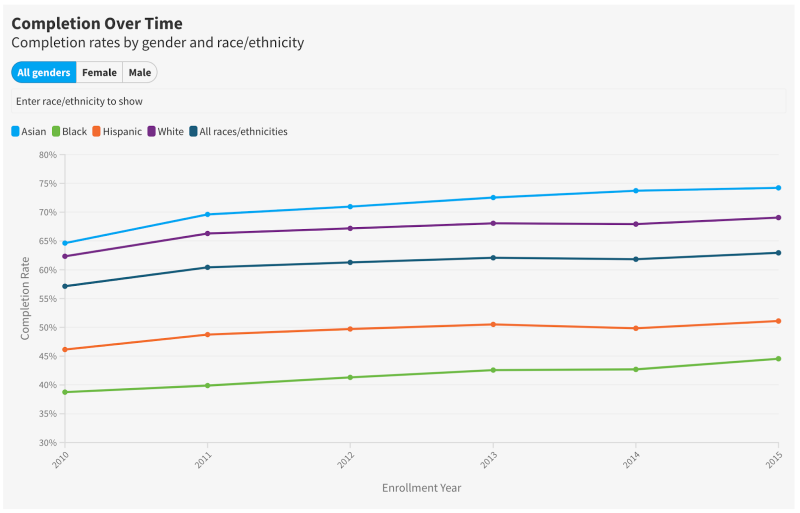

The National Student Clearinghouse’s DEI Data Lab also shows this completion problem starkly.

This chart tracks cohorts of students who began college at the same time and calculates how many of them earned any college degree within six years. Among students who started college in the fall of 2010, 62 percent of white students completed a degree by the summer of 2016, compared with only 39 percent of Black students. That’s a giant 23 percentage point gap, and a sign that a disproportionate number of Black students are dropping out of college in debt. Completion rates improved considerably for students who started college in 2015, but large gaps remain. Almost 70 percent of white students completed a degree by the summer of 2021, but only 45 percent of Black students hit this milestone. The Black-white college completion gap actually widened slightly from 23 to 24 percentage points.

The reasons for why completion rates remain much lower for Black, Hispanic and Native American students are complex. These students are more likely to attend community colleges, which have lower funding per student and fewer support services. Many students weren’t adequately prepared in high schools to handle college-level coursework, especially in math.

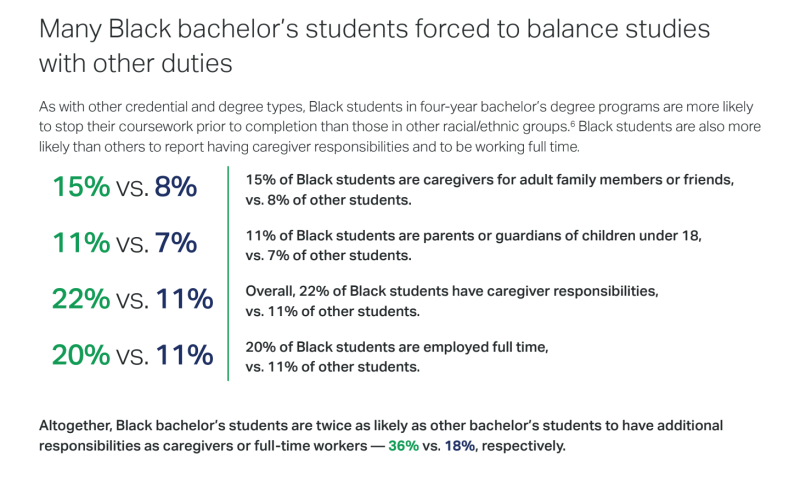

A poll of Black college students by Gallup-Lumina , released on Feb. 9, found that 21 percent of Black students report feeling discriminated against frequently or occasionally at the college they are attending, and that 45 percent have considered dropping out in the past six months. Black students in bachelor’s programs are far more likely to juggle family and work responsibilities alongside their studies.

“Black students are encountering so much more discrimination, and they have multiple responsibilities that no other race or ethnicity really has,” said Lumina’s Brown. “A lot of it is that Black students are more likely to have children. Working full time, having children and trying to get a bachelor’s degree at the same time is just obviously overwhelming.”

On Feb. 2, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center released the most recent college enrollment numbers for 2022. Undergraduate enrollment for both white and Black students fell for the fifth straight year, while enrollment of Hispanic and Asian students at public two-year colleges improved. However, their numbers are below pre-pandemic levels. For example, there were roughly 975,000 Hispanic students enrolled in public two-year colleges, also called community colleges, in the fall of 2022, up from 944,000 in the fall of 2021, but considerably down from 1.14 million in 2019. (Click here and navigate to the demographics tab for these fall 2022 charts.)

And here’s a startling data point: Black student enrollment at two-year community colleges declined by a staggering 44 percent, from 1.2 million in 2010 to 670,000 in 2020, according to a Sept. 2022 report by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a think tank that studies policy issues affecting Black Americans.

Fewer students at college now certainly means fewer college-educated adults in the years ahead. And that is not a promising future.

* Correction: An earlier version incorrectly said that Lumina was founded through the sale of Sallie Mae, instead of USA Group’s sale of assets to Sallie Mae. USA Group was sold, not Sallie Mae.

This story about higher ed data was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Improving community college completion rates by addressing structural and motivational barriers

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, elizabeth mann levesque elizabeth mann levesque former brookings expert, student support & classroom climate consultant - university of michigan @elizkmann.

October 8, 2018

Many community college students in the U.S. do not complete a credential or degree, facing dramatically reduced earning potential. However, evidence suggests that helping students navigate the college environment and connect their coursework to their lives can help solve the community college completion puzzle. In this report, Elizabeth Mann Levesque discusses the structural and motivational barriers these students face, potential solutions, and offers policy recommendations to boost completion rates.

Table of Contents Introduction Section 1: The problem of low completion rates Section 2: The structural barrier Section 3: The motivational barrier Section 4: Policy recommendations

- 63 min read

Introduction

Community colleges have the potential to provide students across the United States with viable pathways into good-paying jobs. However, many students who enroll in community college in the United States do not complete a certificate or degree. Specifically, fewer than 40 percent of community college students earn a certificate or degree within six years of enrollment (Bailey et al. 2015). Individuals who do not complete any type of certificate (also referred to as a credential) beyond a high school diploma face dramatically reduced earning potential (Belfield and Bailey 2017). Low completion rates are thus an urgent problem for millions of Americans seeking a pathway into the middle class and employers reliant on a skilled and educated workforce.

To address this problem, this report discusses structural and motivational barriers to completion that community college students face, as well as strategies to overcome these barriers. The key takeaways are that making it easier for students to navigate the college environment and connect their coursework to their lives can improve student outcomes. This analysis is relevant for community colleges, policymakers seeking to provide students with a viable route to upward economic mobility, employers hoping to strengthen their workforce development partnerships, and philanthropies invested in reducing economic inequality.

Before proceeding, it is important to note that this report is not a comprehensive discussion of all the barriers to completion that community college students face. Many factors contribute to low completion rates, including inadequate academic preparation and financial constraints, despite the relative affordability of public two-year colleges (Holzer and Baum 2017; Goldrick-Rab 2016). Indeed, addressing educational and financial barriers is fundamentally important to improving community college completion. 1 The goal here is to spotlight two particular barriers, structural and motivational, that policymakers, colleges, and employers should address to improve students’ prospects.

Making it easier for students to navigate the college environment and connect their coursework to their lives can improve student outcomes.

Section 1 discusses the role that community colleges play in the higher education landscape, the well-known but intransigent problem of low completion rates, and the value of completing a postsecondary credential or degree. Sections 2 and 3 discuss the structural and motivational barriers, respectively. Section 4 discusses policy recommendations about how to address these barriers.

Section 1: The problem of low completion rates

Extensive evidence indicates that completing a credential or degree beyond a high school diploma, from an associate’s degree all the way up to a doctorate, improves employment outcomes and earnings for individuals (Oyserman 2012; Holzer and Baum 2017; Carnevale et al. 2017; Belfield and Bailey 2017). Yet, community colleges, as the institutions of higher education that serve a large share of low-income students, graduate less than 40 percent of students within six years (Bailey et al. 2015). Thus, community colleges have substantial unrealized potential to improve the earnings and employment outcomes for those at the bottom of the income distribution.

Indeed, community colleges could play a pivotal role in providing a pathway to upward economic mobility because of their ability to reach a large population of low-income and minority students. In fall 2015, community colleges served 41 percent of all U.S. undergraduates. Furthermore, community colleges serve a large share of the country’s non-white undergraduates: 56 percent of Native Americans, 52 percent of Hispanics, 43 percent of African-Americans, and 40 percent of Asian/Pacific Islanders. Public community colleges are also more affordable compared to four-year colleges. For 2017-18, the average annual tuition and fees for public, in-district community colleges was $3,570 compared to $9,970 for public, in-state four year colleges. 2 Given these differences in cost, it is unsurprising that a 2011 analysis found that “44 percent of low-income students (those with family incomes of less than $25,000 per year) attend community colleges as their first college after high school.” 3 In short, community colleges offer a pathway into higher education for a large share of low-income and minority students.

Fewer than 40 percent of community college students earn a certificate or degree within six years of enrollment.

However, many who enroll in community college do not complete a post-secondary certificate or degree. Bailey et al. (2015) summarize the problem succinctly: “Most students who enter these colleges never finish: fewer than four of every ten complete any type of degree or certificate within six years” (p. 1). For example, one analysis finds that, of the students who enroll in community college, only 26 percent earn an associate’s or bachelor’s degree after six years (Jacob 2018).

The story when we consider four-year degree completion rates for students who start at community colleges is also troubling. According to the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Columbia University Teachers College (CCRC), 81 percent of entering community college students indicate they want to earn at least a bachelor’s degree, but only 33 percent transfer to a four-year institution within six years (Horn and Skomsvold 2011; Jenkins and Fink 2016). Of those who transfer, CCRC reports that “42 percent complete a bachelor’s degree within six years (Jenkins and Fink 2016).” The stunning implication is that only “14 percent of the entire cohort of entering community college students earns a bachelor’s degree within six years (Jenkins and Fink 2016).” 4 To be clear, the problem is not a lack of aspiration among community college students (Aelenei et al. 2017). Rather, as this report will discuss in detail, structural barriers in many community colleges often make it difficult for students to achieve their goals.

In addition, college completion rates differ systematically by household income. Comparing two age cohorts, those born in 1961-1964 and 1979-1982, Bailey and Dynarski (2011) find that college entry and completion rates rose over time for children from high- and low-income households in both cohorts. However, they note that “the increases were highly uneven, with gains largest at the top of the income distribution and smallest at the bottom” (p. 120). While the college completion rate for the 1979-1982 birth cohort is 54 percent for students from households in the top income quartile, this rate drops precipitously as income declines, to 32 percent for households in the third quartile, 21 percent in the second quartile, and only 9 percent in the lowest quartile. 5

These low completion rates are clearly problematic, particularly in light of evidence that completing a two-year degree is undeniably valuable in terms of earnings potential. Belfield and Bailey (2017) review analyses of eight states and find that the average earnings gains to completing an associate’s degree compared to enrolling in college but not completing a degree are $4,460 for men and $7,160 for women per year (p. 7). 6 In a different analysis of data from the state of Florida, Holzer and Baum (2017) similarly find large returns to higher education. 7 They find that the largest returns are to completing an advanced degree and bachelor’s degree, which are associated with, on average, 99 and 71 percent increases in earnings relative to completing only a high school diploma, respectively. While the gains to two-year degrees are smaller, they remain substantial. They find that, on average, completing an associate’s degree is associated with a 37 percent increase in earnings compared to only completing a high school diploma. 8 Further, Carnevale (2012) argues that there is important variation in potential earnings by major, describing how, in some cases, students who graduate with a two-year degree in one field stand to earn more than students with a four-year degree in a different field. He explains: “For example, an engineering technician with an associate’s degree can make more than a guidance counselor with a master’s degree” (p. 61).

Related Content

Elizabeth Mann Levesque

July 31, 2017

Not all associate’s degrees yield the same gains. Belfield and Bailey (2017) find heterogeneity in the returns to associate’s degrees in different fields, although they find that across all eight states in their analysis, “Earnings gains are highest for health-related fields” (p. 12). Holzer and Baum (2017) find differences in returns to associate of arts versus associate of science degrees; returns to an associate of science or applied science degree are, on average, 59 percent higher than returns to a high school diploma. In comparison, returns to an associate of arts degree are, on average, 29 percent higher than returns to a high school diploma. 9 Similarly, Belfield and Bailey (2017) note that the returns to associate of science degrees are “much greater than the returns to associate degrees in arts” (p. 12). 10 In addition, there is important variation between outcomes for students who attend for-profit colleges compared to public institutions. Cellini and Turner (2018) find that for students in certificate programs, “In all 50 states and Washington, DC students in public institutions have higher earnings and lower debt that their counterparts in for-profit institutions” (p. 3). Despite this variation across different types of associate’s degrees, one thing is clear: Community colleges play a crucial role in students’ earnings potential.

The estimates of returns to earning a credential are more mixed. Analyzing data from the state of Florida, Holzer and Baum (2017) find that, on average, completing a credential is associated with a 30 percent increase in earnings compared to a high school diploma. 11 Analyzing statewide administrative data sets across multiple states, Belfield and Bailey (2017) find that returns to earning a certificate “vary widely across states” (p. 7). 12

Despite this variation, the bottom line is clear: Compared to only earning a high school diploma, completing a postsecondary credential or degree is associated with higher earnings. In this context, low completion rates among students enrolled in community colleges pose a huge problem, not only for individuals’ earning potential and related life outcomes, but also for society more broadly. Particularly considering that almost half of all low-income Americans first enroll in a community college to pursue higher education, these low completion rates may exacerbate existing economic inequality. Further, there is a strong case for addressing low completion rates in order for the U.S. to remain competitive in the global economy. Low community college completion rates pose a clear challenge for employers reliant on a healthy labor market. For example, in his discussion of how artificial intelligence and emerging technologies are reshaping the nature of work, West (2018) observes the important role that community colleges play in preparing students for the workforce.

Indeed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) predicts that many jobs requiring an associate’s degree or a postsecondary non-degree award (such as a credential) are likely to grow in the near future. As of April 2018, the BLS Occupational Outlook Handbook identified 48 different types of jobs that require an associate’s degree for an entry-level position. For 69 percent of these jobs, the growth rate is predicted to be as fast as or faster than average. 13 BLS also identified 46 types of jobs that require a postsecondary non-degree award, such as a credential, for entry-level positions. Of these, 36 percent are predicted to grow as fast as or faster than average. 14

Low completion rates are a problem for the colleges that seek to serve these students, employers reliant on a strong, local, and appropriately trained workforce, and policymakers responsible for creating a strong workforce capable of driving economic prosperity.

These predictions suggest that in many fields, demand for employees who have a certificate or associate’s degree is increasing. Yet considering the low completion rates for students who enter community colleges, employers may struggle to fill positions. Indeed, West (2018) highlights results from a Deloitte survey that found that “39% of large company executives said they were either ‘barely able’ or ‘unable’ to find the talent their firms required” (p. 112).

Low community college completion rates are a concern for current and prospective students who rely on community colleges to help provide a pathway to financial security. In addition, low completion rates are a problem for the colleges that seek to serve these students, employers reliant on a strong, local, and appropriately trained workforce, and policymakers responsible for creating a strong workforce capable of driving economic prosperity.

A step in the right direction: Providing information on student outcomes

One approach to improving outcomes for community college students (and prospective students) is increasing awareness of the labor market outcomes associated with certain fields of study and degrees. Indeed, evidence suggests a clear need to increase awareness among community college students about outcomes associated with particular programs of study, including information on average earnings and employment opportunities by major and degree. A recent survey of community college students finds that students “overestimate salaries by 13% and underestimate the probability of finding employment by almost 25% in almost all fields” (Baker et al. 2018, p. 19). The authors conclude that providing community college students with more information on labor market outcomes and increasing the salience of this information “could serve community colleges’ goal of improving their students’ labor market prospects” (p. 19).

Evidence suggests a clear need to increase awareness among community college students about outcomes associated with particular programs of study, including information on average earnings and employment opportunities by major and degree.

In terms of providing more information, policy appears to be moving in the right direction. State governments maintain websites that provide information on the state labor market, such as the annual salary of different occupations, as well as projections about the likely growth or contraction of available jobs by occupation in the future. The ease of finding and navigating these websites varies, as does the specific type of information available. 15 Some states have partnered with research institutions to provide relevant information via easily navigable sites; the Launch My Career websites are one example of this approach. Working to bridge the information gap, the Skillful initiative is an example of a private-public partnership that seeks to provide resources for job seekers, employers, and coaches. 16 Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, has advocated for making the connection between postsecondary education and available jobs explicit by creating online matching systems that link job openings with coursework at postsecondary institutions (2012).

The federal government maintains multiple online resources to provide students with information about institutions of higher education. The National Center for Education Statistics maintains the online College Navigator. This resource allows students to explore information on colleges and universities, including information on available majors, cost, enrollment, admissions, retention, and graduation rates. The College Navigator provides information on graduation rates by major, as well as information on the rate at which students default on their student loans. The Department of Education introduced the online College Scorecard in September 2015. The scorecard provides detailed information on institutions of higher education, including student body characteristics, financial aid, debt after graduation, graduation and retention, and average salaries of former students. 17 In sum, this non-exhaustive discussion provides a glimpse into the valuable online resources that provide information to the public about the labor market outcomes associated with higher education.

While important, providing students with information as they make choices about which program of study to embark upon is only part of the solution to the completion problem. Students who need help making informed decisions may not be the ones who are most likely to use information provided online. Noting variation in how students responded to the initial release of the College Scorecard in September 2015–with private school students demonstrating more responsiveness to new information on reported earnings (Hurwitz and Smith 2018)–Holzer and Baum (2017) argue that “[j]ust making general information available is unlikely to significantly improve the college decisions of students from less-privileged backgrounds” (p. 123). Indeed, as discussed above, Baker et al. (2018) recommend not only making information on earnings available, but also making it more salient in students’ decisionmaking.

As the rest of this report discusses in detail, structural and motivational barriers may derail students even when they are equipped with information about labor market outcomes. To preview the nature of these barriers, consider that students who select a major with high potential earnings may find themselves confused about how to complete their chosen program of study. Or, during their coursework, students may not see the connection between their courses and their selected career path. Further, recall that while 81 percent of students enter community college intending to earn a four-year degree, only 14 percent of these students actually do so within six years (Horn and Skomsvold 2011; Jenkins and Fink 2016).

The intent to graduate with a postsecondary degree is clearly present among a majority of community college students. In addition to inaccurate or incomplete information about the potential value of different degrees, other barriers prevent students from reaching their goals. In the subsequent sections, this report discusses structural and motivational barriers to college completion that we should consider alongside strategies designed to provide students with information on labor market outcomes.

Section 2: The structural barrier

The traditional structure of community colleges hampers students’ progress toward completing a credential or degree. This is the core critique by researchers who have recently made a strong and convincing case for rethinking the structure of community colleges (Bailey et al. 2015; Holzer and Baum 2017). Bailey et al. (2015) characterize this traditional structure as a “cafeteria model” (p. 13). In this section, I explain the barriers students face in cafeteria-style colleges, as well as promising strategies for addressing these problems. To be clear, the problems in cafeteria-style colleges are attributable to the structure and design features of colleges, not to faculty, staff, and other individuals who work hard on the behalf of students.

The traditional structure of community colleges hampers students’ progress toward completing a credential or degree.

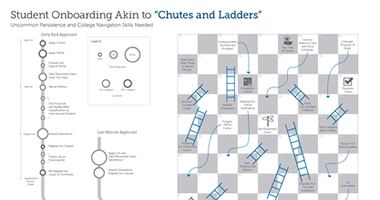

To appreciate the nature of this problem, consider the community college environment. Completing a credential or degree requires students to sort through an overwhelming amount of information to make complicated decisions, such as what to major in, what courses to take to satisfy program requirements, whether and how to get involved in a job training program, whether and how to transfer to a four-year program, and what kind of job to pursue after graduation, just to name a few (Scott-Clayton 2011; Bailey et al. 2015).

In the cafeteria model, it is often difficult for students to identify a clear pathway from enrollment to obtaining a credential, earning a two-year degree, or transferring to a four-year program. Program requirements and options are often unclear, and students have insufficient guidance and support to make informed choices. Bailey et al. (2015) describe how in a cafeteria-style college, “Students are left to navigate often complex and ill-defined pathways mostly on their own” (p. 13). The authors link this structure, and students’ difficulties navigating it, to dropping out: “We find that the typical student is overwhelmed by the many choices available, resulting in poor program or course selection decisions, which in turn cost time and money, and likely lead many students to drop out in frustration” (p. 22).

Cafeteria-style colleges often do not have enough advising resources to support students as they try to navigate this complex environment. The ratio of students to academic advisers is staggering. Estimates of the typical adviser’s caseload vary, but in all cases, it is clear that advisers are stretched incredibly thin. Bailey et al. (2015) cite estimates of approximately one adviser per every 800-1,200 students (p. 58-59). The National Academic Advising Association reports a median of 441 students per adviser in community colleges (Scrivener et al. 2015 p. 26, citing Robbins 2013).

During initial advising sessions, there is typically not enough time for long-term planning, goal-setting, or a thorough orientation to college life and how to navigate from enrollment to completion (Bailey et al. 2015). Bailey et al. (2015) report that on the Community College Survey of Student Engagement, “Only 38 percent of students reported that an advisor helped them to set academic goals and create a plan for achieving those goals” (p .55). Through the orientation and registration process, students often do not learn about the college’s program offerings or career or transfer pathways. Without a clear understanding of available opportunities, “They embark on a slate of courses whose relevance to their own nascent goals and interests may not be entirely clear” (Bailey et al. 2015, p. 56). While cafeteria-style colleges may offer support services to help students navigate this terrain, Bailey et al. (2015) conclude that navigating even the support services can be “complicated and confusing” (p. 58-59).

Holzer and Baum (2017) draw a clear connection between the structural barriers in cafeteria-style colleges and low completion rates that is worth quoting at length:

The cafeteria approach reduces success rates among students for a variety of reasons. Students have too many options, too little information about the alternatives, and too little insight into their own skills and preferences when choosing courses and majors…Instead of gathering sufficient information to make sensible choices, students defer difficult choices like choosing a major and fall back on default options, taking the path of least resistance. They struggle to complete the degree or credential they seek, with too little guidance about what courses to take and in what sequence. Students have particular difficulty transferring into other programs and to institutions because the credits they have earned are frequently not accepted (p. 160).

In short, students entering community college often face many decisions about how to define and achieve their goals. Confronted with an overwhelming number of options, many students do not know how to progress from enrollment to program completion, lacking sufficient support in charting a course and adhering to their plans. As a result, students invest time and money in classes that may not feel related to their own goals and may not adequately satisfy specific program requirements. In this environment, students may not see the value in remaining enrolled.

Addressing the structural barrier

Addressing the structural barrier requires rethinking the organization of community colleges to reduce the confusion and frustration that contributes to low completion rates. This type of approach is referred to as the “guided pathways” model. In contrast to the cafeteria model, guided pathways models feature clearly structured programs and extensive advising support. Bailey et al. (2015) describe the guided pathways approach as a comprehensive strategy to address the problems found in the cafeteria model, focusing on program structure, intake and student supports, instruction, and developmental education.

In contrast to the traditional “cafeteria-style model” of community colleges, the guided pathways approach features clearly structured programs and extensive advising support.

Bailey et al. (2015) explain the guided pathways framework as follows. 18 The steps for moving toward completing a credential or degree are much clearer, and the decisionmaking process is simplified. Academic programs are clearly defined, with coherent trajectories. Students who enter without a clear direction are assisted in choosing an area of study with a default curriculum that the student can modify to fit their interests. The intake and student support services provide students with consistent, structured advising. Students are not left on their own to make important decisions about career pathways or to ask for help when they are struggling. Rather, students receive career counseling at the outset, and advisers track students’ progress through their programs. In terms of instruction, faculty help to clarify how students will achieve the learning outcomes associated with each program of study. Developmental education courses, which can often be a stumbling block for students, are more deliberately incorporated into programs of study.

Evidence suggests that implementing reforms aligned with this guided pathways approach can improve student outcomes. Perhaps the most high-profile success story of a guided pathways approach is the City University of New York’s (CUNY) Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP). The ASAP program is “designed to help more students graduate and help them graduate more quickly” (Scrivener et al. 2015, p. iii). The program requires participants to attend classes full time, and students are encouraged to take developmental courses early and to graduate within three years. Students receive advising services from advisers with small caseloads, and they receive enhanced career services and tutoring. Students can take blocked courses in the first year, and they can also take a seminar during their first few semesters that emphasizes skills like goal-setting. ASAP participants receive a tuition waiver that covers all expenses including tuition and fees, free use of textbooks, and free passes for public transportation provided that students participate in certain program services (Scrivener et al. 2015, p. iii).

MDRC, a nonprofit, nonpartisan education and social policy research organization, conducted a rigorous evaluation of the ASAP program using a random assignment study at three CUNY community colleges (Scrivener et al. 2015). The study compared low-income students who needed developmental coursework and were randomly assigned to participate in ASAP with similar students who were randomly assigned to a control group; the control group students had access to the standard CUNY services for students. The results were overwhelmingly positive. The evaluation found that over three years, ASAP students earned nine more credits than control group students. Graduation rates almost doubled among ASAP students—40 percent of ASAP students had received a degree within three years, compared to 22 percent of the control group. Further, transfer rates to four-year programs were higher among ASAP students (25 percent of the group) compared to control group students (17 percent). The program was also cost effective; because the graduation rate was so much higher among ASAP students, the cost of services per graduate was actually lower.

The authors of the MDRC report underscore the importance of these results: “ASAP’s effects are the largest MDRC has found in any of its evaluations of community college reforms. The model offers a highly promising strategy to markedly accelerate credit accumulation and increase graduation rates among educationally and economically disadvantaged populations” (p. iii). Without a doubt, the ASAP program represents an effective strategy for improving college completion rates among disadvantaged populations.

Several aspects of the ASAP program target the structural barriers found in cafeteria models. In particular, the ASAP program provides comprehensive advisement services, described as such by the authors of the MDRC report:

During the course of the study, ASAP students were required to meet with their assigned adviser in person twice per month throughout each semester; advisers also sometimes communicated with students by phone, e-mail, or text message. Advising appointments were tracked, and attendance was linked to students’ receipt of monthly Metro-Cards. ASAP students were assigned an adviser during their first semester and usually continued to see the same person throughout their college careers (Scrivener et al. 2015, p. 26).

As part of the evaluation, ASAP and control group students were surveyed during their first year of college. These survey responses show that students in the ASAP program group reported seeing their advisers much more frequently compared to students in the control group (21 times on average in the first semester compared to four, and 17 times in the second semester compared to two). ASAP students were more likely to rate their advising experiences as high quality, and on average, they reported spending more time with their advisers during each session (64 percent of ASAP survey respondents reported advising sessions of 16 to 30 minutes on average compared to 47 percent of control group survey respondents). 19 Students in the ASAP program also report discussing a wider range of topics with their advisers. For example, 95 percent of ASAP program participants reported discussing academic progress with their adviser compared to 62 percent of control group respondents (p. 29).

Over a three-year evaluation, graduation rates almost doubled among ASAP students—40 percent of ASAP students had received a degree within three years, compared to 22 percent of the control group. Further, transfer rates to four-year programs were higher among ASAP students compared to control group students.

ASAP students and control group students worked with different advisers. The ASAP advisers had much smaller caseloads, serving an average of 60 to 80 students per semester. At the three colleges in the ASAP study, non-ASAP advisers had caseloads that ranged from 600 to 1,500 students per adviser (p. 26). The report notes that “[while] dedicated, the colleges’ non-ASAP advisers managed very large caseloads that typically did not permit the more personalized touch that students experienced in ASAP advising” (p. 28).

ASAP students were also required to visit an ASAP career and employment specialist (CES) once a semester. These specialists discussed topics such as finding part-time jobs, networking, writing resumes, and aligning majors with career paths. Students in the control group were not required to visit a specialist, and survey results indicate that ASAP students used these services more frequently: 80 percent of ASAP survey respondents indicated that they spoke with CES staff in their first year, compared to 29 percent of control group students (p. 31, Table 3.4).

As mentioned above, the program mandated specific requirements of students and provided additional resources beyond advisement and career services, such as financial support, free use of textbooks, and free public transportation. Indeed, the authors of the MDRC report observe that ASAP program is an “uncommonly comprehensive and long-term program” (p. iii). Furthermore, the MDRC analysis discussed here was not designed to evaluate the impact that individual components of the program had on students’ credit accumulation and graduation rates. Rather, the evaluation estimates how the “full package” of ASAP services affected students’ academic outcomes (p. 85). Policymakers hoping to learn from and adapt this approach must be aware that it is not necessarily the case that implementing some, but not all, of the ASAP approach will produce the same positive outcomes for students.

Students face substantial structural barriers to college completion when colleges are organized in the traditional “cafeteria-style” model. As the ASAP program convincingly demonstrates, addressing these design flaws can dramatically improve completion rates among students. Admittedly, enacting this entire suite of structural changes in a community college may be a daunting and costly prospect. 20 Nonetheless, the evidence is clear that embracing the guided pathways approach is an essential step toward improving community college completion rates. Section 4 below offers recommendations about steps aligned with the guided pathways approach that community colleges can take to improve their students’ experiences and outcomes.

Section 3: The motivational barrier

Community college environments fundamentally shape students’ experiences, as the previous section illustrated. In cafeteria-style environments, it can be very difficult for students to identify connections between their coursework and their own lives and future goals. This disconnect is what I refer to as a motivational barrier. Unfortunately, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the structural problems in cafeteria-style colleges contribute to this barrier. For this reason, while this section primarily focuses on the motivational barrier, it also builds on the prior discussion of structural challenges and acknowledges the relationship between structural and motivational barriers.

This section discusses the importance of motivation in educational settings and reflects on how adopting a guided pathways approach and incorporating specific instructional strategies can help address this motivational barrier. It is important to emphasize at the outset that community college students do not have inherent shortcomings that create a motivational barrier. As discussed above, the vast majority of community college students enter college intending to complete a four-year degree. Furthermore, low-income students who attend four-year colleges and universities have “very similar earnings outcomes” compared to high-income students who attend the same school (Chetty et al. 2017, p. 2). However, in cafeteria-style colleges, students face structural barriers that make the road to completion unclear and difficult. Compounding these structural challenges, community college students are more likely than their four-year university peers to experience life circumstances that make navigating academic settings more difficult (Aelenei et al. 2017).

Defining the motivational barrier

The subsequent discussion focuses on a particular aspect of motivation that can have powerful, positive effects on student outcomes, including long-term interest in a subject and academic performance: students’ perceptions that their coursework is meaningful in relation to their lives. Maintaining this type of motivation can unfortunately be quite difficult in cafeteria-style college settings. Bailey et al. (2015) note that “without a specific goal to work toward, it can be difficult for students to maintain their motivation to persist in school” (p. 57). They describe how this lack of motivation may be a barrier for students, citing survey results in which current and former community college students indicate that having a goal helps them stay on track in college. Karp (2011) similarly describes how students need to perceive a connection between their coursework and their lives to stay sufficiently motivated: “Students who do not see the value in their coursework often behave in counterproductive ways, for example, by failing to complete assignments or dropping required courses” (p. 12).

This perceived disconnect between coursework and students’ own lives may be exacerbated within the cafeteria-style college. Without sufficient knowledge of the programs of study available or how to choose courses related to a particular academic or career path, students may enroll in courses that have little relevance to their career goals. Even if students are enrolled in courses that are related to their long-term interests, it may be difficult to see how a specific course helps them come closer to earning a credential or degree if program pathways are unclear. Indeed, these are some of the main shortcomings of the cafeteria model as discussed by Holzer and Baum (2017) and Bailey et al. (2015). Perceiving little to no “real-world” application of their coursework, students may decide that remaining enrolled in coursework is a bad investment, opting instead to drop out of college to join the workforce immediately. In other words, for students to stay motivated to persist on their academic trajectory, they need to both see the destination (the careers and earnings an education will provide) and the pathway to get there (the connections between what they are doing in school and what they would like to achieve) (Oyserman and Lewis 2017). The motivational barrier is thus an obstacle to degree completion, with negative consequences for students and the workforce more broadly.

For students to stay motivated to persist on their academic trajectory, they need to both see the destination (the careers and earnings an education will provide) and the pathway to get there (the connections between what they are doing in school and what they would like to achieve).

I draw on the expectancy-value (EV) framework to define this type of motivational barrier more precisely. 21 Hulleman et al. (2016) explain that since the 1980s, psychologists have applied the EV framework to explain student behavior in educational contexts. According to the EV framework, there are “two critical aspects of motivation that are necessary for students to be optimally engaged. First, students need to believe that they can succeed (i.e. positive expectancies). Second, students need to perceive an important reason to engage in the behavior (i.e. need to have positive values)” (Hulleman et al. 2016, p. 242). Hulleman and colleagues add a third dimension to this framework: cost. “Even if students believe they can do a task and have a reason to do a task, they still might not be motivated if they experience significant cost preventing them from engaging in that task” (Hulleman et al. 2016, p. 258). Thus, in terms of the EV framework, a motivation barrier may occur if students have low expectancy (do not believe they can succeed), low value (do not perceive value in a particular behavior), or high costs (insufficient time or resources to engage in the behavior).

In the context of community college completion, students may be particularly vulnerable to low expectancy, low value, and high costs. In terms of expectancy, students who enter community college and who have previously struggled in academic settings may not believe that they will be successful in their coursework. In terms of value, particularly in cafeteria-style settings, students may not see a connection between completing current courses and progressing toward academic and/or career goals. Given the demands on many community college students’ time, including work and family commitments (Johnson and Rochkind 2009), perceiving value in their coursework may be critically important to sustaining the necessary motivation to stay enrolled. Finally, in terms of cost, community college students may lack sufficient financial resources to stay enrolled (Goldrick-Rab 2016). 22

Expectancy value interventions

Research on the relationship between students’ perceptions of value and their academic outcomes provides insight into the role of motivation in student success. Hulleman et al. (2010) argue that “it is plausible that students who are disengaged from school due to a history of poor performance or low expectations may benefit the most from a utility value intervention” (p. 882). Indeed, a large body of rigorous, experiment-based research on EV interventions in educational settings illustrates the importance of helping students to build motivation. Further, this work suggests that increasing students’ perception of the value of their coursework can have powerful, positive effects, particularly for students who initially have low expectancies.

A large body of rigorous, experiment-based research on expectancy-value interventions in educational settings illustrates the importance of helping students to build motivation.

These EV interventions vary, but in general, they prompt students to connect their coursework to their lives–in the words of Hullemen and colleagues, to “generate their own connections and discover for themselves the relevance of course materials to their lives” (Hullemen et al. 2010, p. 881). Several interventions implemented in different educational contexts have demonstrated that increasing students’ value in a particular task can positively impact student outcomes, including performance and interest in a course (Hulleman and Harackiewicz 2009; Hulleman et al. 2010; Harackiewicz et al. 2015; Rozek et al. 2015). This type of intervention appears particularly effective for students with low expectations at the beginning of a course (Hulleman et al. 2010). These experiments have been conducted in high school (Hulleman and Harackiewicz 2009; Rozek et al. 2015) and college settings (Hulleman et al. 2010; Harackiewicz et al. 2015; Hullemen et al. 2017).

A brief discussion of a college-level EV intervention helps exemplify what this type of intervention entails and how it can affect student outcomes. Hullemen et al. (2010) conducted two EV interventions via two experiments, one in a laboratory setting and one in an introductory psychology course. This discussion focuses on the latter. Students were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, and each group received a different writing assignment (the assignments were part of the syllabus and were completed for course credit). These assignments required students to choose a topic covered in the course and write a one to two page essay on the topic; students were required to complete this assignment twice.

In the treatment group, students were either assigned to write a letter to a significant person in their lives “describing the relevance of their topic to this person” or “find a media report … that pertained to their topic and write an essay that discussed the relevance of the media report to information they were learning in class” (p. 888). Both assignments “asked students to connect the course material to their lives through their social connections or the popular media” (p. 888). In the control group, students were not asked to make this personal connection. Instead, they either summarized a topic from class or searched an online database for abstracts related to the topic and discussed how the abstracts “expanded upon the material they were learning in class” (p. 888). Neither control group prompt encouraged students to identify the relevance of their coursework for their own lives.

The researchers measured students’ interest in psychology and their perceptions of the value of the course (utility value) based on their responses to a number of items. For example, one item used to measure perceptions of utility value was: “I think what we are studying in Introductory Psychology is useful for me to know” (p. 888). The researchers also measured students’ grades in the course. The study finds that the intervention increased students’ perceptions of utility value, and in turn, students were more interested in majoring in psychology. Further, students’ grades improved as their utility values increased. These effects were strongest for students with lower prior performance in the course. In short, the intervention increased students’ perception of value in the course material, which in turn increased interest in the field of psychology and improved academic performance in the course. 23

Keep in mind that this intervention only required students to write two short essays reflecting on the relevance of their coursework for their lives. Furthermore, this intervention worked particularly well for students with low expectancies. The authors summarize the practical application of these results:

Practically speaking, the relevance intervention is easy and inexpensive to implement, produces effects in as few as one or two trials, can be flexibly implemented during class or on the students’ own time, and is applicable to a diverse array of topics or activities. Although the participants in our research only wrote about two topics (mental math and psychology), there is no reason to assume that similar results cannot be obtained in other domains, such as history, English, or chemistry. In fact, some recent research indicates that these results also obtain in high school science and college statistics classes (Hulleman, Hendricks, & Harackiewicz, 2007; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009). Importantly, the students who most often concern teachers—those who perform poorly and have low performance expectations— benefited the most from our intervention, and those with high performance expectations were not harmed by it (p. 892).

In short, EV interventions are promising strategies to help improve student motivation. This research illustrates the positive academic outcomes associated with helping students identify the applicability of their coursework to their lives outside the classroom.

Students benefit from perceiving a connection between their coursework and their lives. The implications for improving community college completion rates are two-fold. First, this research on motivation underscores the urgency of addressing structural barriers that make it difficult for students to identify and complete a course of study. When students, particularly those with low expectations, identify the relevance of their coursework to their lives, they perform better and express more interest in the subject they are studying. Yet, this is precisely the type of connection that can be difficult to make in cafeteria-style settings, where paths of study are unclear and resources are confusing to navigate. Structural reforms can help students identify and progress along clear pathways from enrollment to graduation. In this environment, it may be easier for students to identify a clear connection between their coursework and their own lives, which may have positive outcomes for their performance and interest in their program of study.

Second, EV interventions may be useful tools for instructors and perhaps advisers in a community college context. These interventions can be tailored to specific courses, and if implemented properly, EV interventions may help students perceive value in their coursework, increase their interest in the course, and improve their performance. These positive outcomes may be building blocks that help students complete the necessary courses to earn a postsecondary credential or degree. As Section 4 discusses at length, this is not to say that including EV interventions within courses can singlehandedly solve the completion problem; far from it. However, these interventions may be valuable components of a broader strategy to create a college environment conducive to student success.

Section 4: Policy recommendations

Community colleges can play a pivotal role in providing individuals with viable pathways into the American middle class, maintaining a strong workforce, and building a competitive 21 st -century economy. Delivering on this promise requires innovative solutions to increase the number of community college students who complete a postsecondary credential or degree.

Delivering on the promise of community college requires innovative policy solutions to increase the number of students who complete a postsecondary credential or degree.