New Report: How We Voted in 2022

Launching the 2022 Survey of the Performance of American Elections report and dataset

By Claire DeSoi 05.23.2023

https://electionlab.mit.edu/articles/new-report-how-we-voted-2022

A Brief Summary

Access the data + learn more.

Today we are thrilled to launch our report on the 2022 Survey of the Performance of American Elections, with its accompanying dataset.

The Survey of the Performance of American Elections (SPAE) provides information about how Americans experienced voting in the most recent federal election. The survey has been conducted after federal elections since 2008, and is the only public opinion project in the country that is dedicated explicitly to understanding how voters themselves experience the election process.

We are delighted to announce that our report detailing findings from the 2022 SPAE is now available to read, and that the 2022 dataset is now available for researchers to access and use!

10,200 registered voters responded to the 2022 survey—200 observations in each state plus the District of Columbia. We are proud to once again offer this comprehensive, nationwide dataset at the state level documenting election issues as experienced by voters.

Read the Report:

Don't have time to read the full report now, or just want to access the key findings? We've excerpted some of the report's executive summary below.

Voting by mail

- The percentage of voters casting ballots by mail retreated to 32 percent, down more than 10 points from 2020. more than doubling the fraction from 2016. The share of voters casting ballots on Election Day grew to 50 percent, from 31 percent in 2020.

- Forty-six percent of Democrats, compared to 27 percent of Republicans, reported voting by mail. This is down from 60 percent for Democrats and 32 percent for Republicans in 2020.

- The use of mail to return ballots that were mailed to voters rebounded in 2022, to 62 percent, compared to 53 percent in 2020. Twenty-one percent of mail ballots were returned to drop boxes, which is virtually unchanged from 2020.

- Almost five percent of voters who returned their ballot to a drop box reported seeing something disruptive, such as demonstrators, when they dropped off their ballot.

- Forty percent of mail voters reported using online ballot tracking.

In-person voting

- The use of schools to vote in-person continued its decade-long gradual decline.

- Average wait times to vote were roughly equal to the last midterm election for Election Day voters (6 percent waiting over 30 minutes compared to 5 percent in 2020); they declined for early voters (4 percent reported waiting over 30 minutes compared to 7 percent in 2020).

- Ten percent of Election Day voters and 9 percent of early voters reported seeing something disruptive when they voted. The most common disruptions were voters talking loudly and voters in a dispute with an election worker or other voter.

- Approximately 3 percent of in-person voters reported seeing demonstrators outside their polling place claiming the election was fraudulent.

Satisfaction with voting

- Voters who cast ballots in person and by mail continued to express high levels of satisfaction with the process, as in past years.

Reasons for not voting

- The primary reported reason for not voting in 2022 was not knowing enough about the choices (12.1 percent of non-voters), followed by not being interested (11.7 percent). and being too busy (9.8 percent).

Voter confidence

- Measured across all voters, confidence that votes were counted as intended remained similar to past years.

- The partisan gap in confidence that opened up in 2020 closed somewhat in 2022, with the primary reason being Republicans becoming more confident.

- Compared to 2020, the Democratic-Republican gap in state-level confidence declined significantly in most states. Major exceptions were Pennsylvania and Arizona.

- Among Republicans, lack of confidence in whether votes were counted as intended at the state level was strongly correlated with whether Donald Trump won the respondent’s state and with the fraction of votes cast by mail in the state.

Election security measures

- Of a set of common security measures used by election officials, respondents were most aware of logic-and-accuracy testing and securing paper ballots. One-third of respondents stated that election officials used none of the measures asked about.

- Respondents stated that the security measures that would give them the greatest assurance about the security and integrity of elections were logic-and-accuracy testing (74 percent), securing paper ballots (74 percent), and post-election audits (72 percent).

- Partisan attitudes about the prevalence of several types of vote fraud remained polarized in 2020, although less so than in 2020.

- Requiring electronic voting machines to have paper backups, requiring a photo ID to vote, automatically changing registrations when voters move, requiring election officials to be nonpartisan, and declaring Election Day a holiday were supported by majorities of both Democrats and Republicans.

- Adopting automatic voter registration, moving Election Day to the weekend, and Election-Day registration are supported by a majority of respondents, but not by a majority of Republicans.

- Ranked-choice voting, conducting elections entirely by mail, and allowing Internet voting were opposed by a majority of respondents but supported by a majority of Democrats; hand-counting paper ballots was opposed by a majority of respondents but supported by a majority of Republicans.

- Voting on cell phones was opposed by majorities of Democrats and Republicans.

Read the full report

Data and documents related to all versions of the Survey of the Performance of American Elections are available from the Harvard Dataverse, as is direct access to the 2022 data and documentation. For those links, or more information about the survey in general, navigate to:

Access the 2022 Data

Access all SPAE Data

Learn more about the SPAE

Claire DeSoi is the communications director for the MIT Election Data + Science Lab.

Back to Main

Related Articles

Retaining Election Officials in a Time of Uncertainty

Evaluating Practitioner Interventions to Increase Trust in Elections

By Jennifer Gaudette, Seth Hill, Thad Kousser, Mackenzie Lockhart, and Mindy Romero

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

PoliticalElections →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal

Home Thematic Issues 3 Studying Elections in India: Scie...

Studying Elections in India: Scientific and Political Debates

Election studies (which are here defined as scholarly work focusing on the major phases of the electoral process, i.e. the campaign, the vote, the announcement of results and subsequent government formation) constitute a distinct sub-genre of studies on democracy, which focuses, so to speak, on the ‘mechanics’ more than on the ‘substance’ of representative democracy. This sub-genre, being relatively more visible than other studies of representative democracy, has specific implications, in the academic but also in the political arena, which are the focus of this critical review of the literature on Indian elections since the 1980s. The paper argues that election studies are really in between science and politics, and that it is important, therefore, to contextualize them.

Index terms

Keywords: .

1 Studying elections in the largest democracy in the world is bound to be a challenge: given the size of the country and of its population, Indian national elections have been the largest electoral exercise in the world ever since the first national elections in 1952. Moreover the cultural, linguistic, ethnic and religious diversity of the Indian society, as well as the federal nature of the Indian state, make this event a particularly complex one. What, then, have been the methodologies and approaches deployed to study this major political event? What have been the disciplines and foci of election studies? Who have been the main authors? In what form have these studies been publicized, and what type of readership have they targeted? Reading the available literature with these questions in mind, I have tried to identify some major shifts over time, and to grasp their meaning and implications; a few interviews with specialists of the field have allowed me to test some of the interpretations suggested by the readings. Through a review of the literature on Indian elections since the 1980s, this paper aims at mapping the scientific and political debates around election studies.

- 1 Most works considered here deal with national elections, but some of them also focus on state elect (...)

- 2 I owe this formulation to Amit Prakash, whose comments on a previous version of this paper were ver (...)

2 Election studies are here defined as scholarly work focusing on the major phases of the electoral process, i.e. the campaign, the vote, the announcement of results and subsequent government formation. 1 This is a restrictive definition: elections are obviously a central institution of representative democracy, and as such they are connected to every aspect of the polity. Yet election studies constitute a distinct sub-genre of studies on democracy, which focuses, so to speak, on the ‘mechanics’ more than on the ‘substance’ of representative democracy. 2 This sub-genre, being relatively more visible than other studies of representative democracy, has specific implications, in the academic but also in the political arena, which will be the focus of this critical review. This paper will argue that election studies are really in between science and politics, and that it is important, therefore, to contextualize them.

3 The paper starts with a quick overview of the different types of election studies which have been produced on India, and goes on to analyze a series of dilemmas and debates attached to election studies, which highlight the intricate nature of the political and scientific issues at stake.

The study of Indian elections: an overview

4 At least three previous reviews of election studies have been realized, by Narain (1978), Brass (1985), and Kondo (2007). Both Narain and Kondo provide a fairly exhaustive list of publications in this field, and discuss their relevance and quality. Brass’ review also offers a detailed discussion of the advantages and limitations of ecological approaches, to which I will later return.

5 There is no need to repeat this exercise here. But in view of situating the debates described in the next section of the paper, I simply want to sketch a broad typology of election studies published since the late 1980s—a moment which can be considered as the emergence of the new configuration of the Indian political scene, characterized by (i) the importance of regional parties and regional politics; (ii) the formation of ruling coalitions at the national and regional levels; and (iii) the polarization of national politics around the Congress, the BJP, and the ‘third space’.

6 All three reviews of the literature highlight the diversity of disciplines, methods, authors, institutions, and publication support of studies of Indian elections. But a major dividing line appears today between case studies and survey research (which largely match a distinction between qualitative and quantitative studies), with a number of publications, however, combining elements of both.

Case studies

7 Case studies analyze elections from the vantage point of a relatively limited political territory, which can be the village (for instance Somjee 1959), the city (or, within the city, the mohalla , the basti ), the constituency, the district, or the state. The major discipline involved in this type of research has been political science. Indeed elections have been the object par excellence of political science worldwide. In India as elsewhere, as we will see below, election studies reveal characteristic features of this relatively recent discipline, insofar as they embody some tensions between science and politics.

- 3 Another example is a study of parliamentary and state elections in a village in Orissa at the end o (...)

8 Paul Brass developed the case study method in the course of his long interest for politics in Uttar Pradesh. His monograph on the 1977 and 1980 elections focuses on Uttar Pradesh (he justifies this choice saying that this election was largely decided in North India). His research is based on fieldwork in five selected constituencies whose ‘electoral history’ is minutely recalled. Here the choice of the unit of analysis is linked to pedagogical considerations: ‘Each constituency chosen illustrates a different aspect of the main social conflicts that have been prominent in UP politics’, he writes (Brass 1985: 175). Indeed in the case study approach, the detailed observation of elections in a particular area aims at uncovering processes and dynamics which are relevant for a much wider territory. 3

- 4 In the early years of independent India, the Indian Council for Social Science Research (ICSSR) com (...)

- 5 One must note that among the various disciplines producing case studies, anthropology uses the larg (...)

9 Beside political science, anthropology has also approached elections in a manner close to case studies. 4 But anthropological studies are usually focused on a more limited political territory (typically, the village), and more importantly, they are centered on a questioning of the meaning of the electoral process 5 for voters: why do people vote? More precisely, why do they bother, what is the meaning of voting for them? Thus anthropologists often focus on the symbolic dimension of elections:

From this [symbolic] perspective, democracy is really an untrue but vitally important myth in support of social cohesion, with elections as its central and regular ritual enactment that helps maintain and restore equilibrium (Banerjee 2007: 1556).

10 Taking the ritual as a central metaphor in their accounts of elections, anthropologists help us see the various ‘ceremonies’ and ‘performances’ that constitute the electoral process:

To define [the] cultural qualities of Indian democracy, it is important to view the ritual of the election process through four consecutive ceremonies [:] Party endorsement […], the actual campaign […], the day of polling [and the] public announcement [of winners] (Hauser & Singer 1986: 945).

11 On the basis of their observations of two elections in Bihar in the 1980s, Hauser and Singer define the electoral process as a ‘cycle’. They describe the successive phases of this cycle, and draw parallels with religious rituals, noting for instance that the electoral process involves a series of processions. Their likening of the electoral campaign to a ‘pilgrimage’ manifesting the ‘inversion of power from the hands of the politicians back to the hands of the voters’ (Hauser & Singer 1986: 947) goes a long way in explaining the festive dimension of Indian elections.

12 Anthropological studies of elections also clearly show how elections precipitate, or at least highlight, otherwise latent political dynamics. The long fieldwork characteristic of the discipline makes it possible to concretely demonstrate how elections render visible otherwise subtle, if not invisible, relationships of influence:

[…] election day was when the complexity of the village’s social life was distilled into moments of structure and clarity, when diffuse tensions and loyalties were made unusually manifest (Banerjee 2007: 1561).

13 For Banerjee, who studied politics from the standpoint of a village in West Bengal, an election is a celebration in two ways: (i) it is a festive social event; (ii) it involves a sense of democracy as sacred. Therefore she understands ‘elections as sacred expressions of citizenship’ (Banerjee 2007: 1561).

14 For all their evocative strength, one can regret that anthropological studies of Indian elections deal mostly with villages and with traditional electoral practices. However one must also note that elections elsewhere have attracted even less attention from anthropologists. Indeed, a recent issue of Qualitative Sociology deplored that ‘at a time when few, if any, objects are beyond the reach and scrutiny of ethnographers, it is quite surprising that politics and its main protagonists (state officials, politicians and activists) remain largely un(der)studied by ethnography’s mainstream’ (Auyero 2006: 257).

Other approaches

15 A number of articles and books on Indian elections combine different methodological approaches. Thus some of Banerjee’s conclusions are shared by the political scientists Ahuja and Chibber ( n.d. ), in an interesting study combining quantitative and qualitative methods ( i.e. election surveys (1989-2004) and a series of focus group discussions) in three large Indian states. In order to understand the particular pattern of electoral turnout described by Yadav as characteristic of the ‘second democratic upsurge’ (Yadav 2000), Ahuja and Chibber identify three broad social groups, defined by three distinct ‘interpretations’ of voting. They argue that ‘differences in the voting patterns of opposite ends of the social spectrum exist because each group interprets the act of voting differently’. Thus the act of voting is considered as a ‘right’ by the groups who are on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum—the ‘marginalized’; as an ‘instrument […] to gain access to the state and its resources’ by those in the middle of that spectrum—the ‘State’s clients’; and as ‘civic duty’ by those at the top—‘the elite’ (Ahuja & Chibber 2009: 1-9).

- 6 One must also mention the ‘Chronicle of an Impossible Election’— i.e. the 2002 Assembly election in (...)

16 Among the ‘other approaches’ of elections, one also finds a number of monographs devoted to a single election 6 . For instance Myron Weiner’s study of the 1977 election constitutes an interesting, contemporary account of the beginning of the end of Congress dominance over Indian politics, with the first part devoted to the campaign and the second part to the analysis of results, on the basis on a medley of methods typical of political science:

In four widely scattered cities – Bombay […], Calcutta, Hyderabad, and New Delhi […]—[the author] talked to civil servants, candidates, campaign workers, newspaper editors, and people in the streets, attended campaign rallies and visited ward offices, collected campaign literature, listened to the radio, and followed the local press (Weiner 1978: 21)

17 In the 1990, a series of collective volume were published on parliamentary elections (for instance Roy & Wallace 1999). Often based on aggregate data such as those published by the Election Commission of India, they offer a series of papers that are interpretative, speculative, critical in nature.

- 7 This is in sharp contrast with France, where electoral geographers such as André Siegfried have bee (...)

18 I have found one single book of electoral geography (Dikshit 1993), 7 which presents election results (crossed with census data) as a series of maps. This particular method highlights unexpected regional contrasts and similarities, which stimulates the production of explanatory hypotheses.

- 8 This inventory of ‘ other’ election studies, that is, studies of elections that fall neither in the (...)

19 Finally, a recent book by Wendy Singer (2007) makes a case for an application of social history to elections. Going through a large material relating to elections (national, state, local) from 1952 to the 1990s, she shows how some details of the electoral process reveal important social changes over time. 8

20 The gathering of the above mentioned writings in a single, residual category is not meant to suggest that they are less effective than case studies or survey research in describing and explaining elections. On the contrary, the variety of methodologies that they mobilize shows the richness of elections as an object of scientific enquiry. But these studies eschew the strong methodological choices which define the other two categories and which point to the political stakes specific to election studies.

Survey research

21 Survey research has been dominating election studies since the 1990s for a variety of reasons. I will here use Yadav’s definition of this particular method:

[…] a technique of data gathering in which a sample of respondents is asked questions about their political preferences and beliefs to draw conclusions about political opinions, attitudes and behavior of a wider population of citizens (Yadav 2008: 5).

9 Eric Da Costa founded the Journal of Public Opinion .

- 10 The CSDS was meant, in Kothari’s own words: ‘One, to give a truly empirical base to political scien (...)

- 11 The CSDS did not even study the 1977 election, on which we fortunately have Myron Weiner’s monograp (...)

22 Survey research exemplifies the close relationship between the media and political science. It was introduced in India in the late 1950s by an economist turned journalist, Eric Da Costa, considered ‘the father of opinion polling in India’ (Butler et al. 1995: 41), 9 who went on to work with the Indian Institute of Public Opinion (IIPO) created in 1956—but it was political scientists such as Bashiruddin Ahmed, Ramashray Roy and Rajni Kothari who gave it a scientific grounding. In his Memoirs (2002), Kothari recalls how he went to Michigan University—which had developed an expertise in psephology, i.e. the statistical analysis of elections - to get trained in survey research. When he came back to India, Kothari applied this new method in his work at the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), which he had founded a few years earlier, in 1963. 10 The first election to which he applied this newly acquired expertise was the Kerala state election in 1965 (Lokniti team 2004: 5373). The CSDS team then went on to study general elections in 1967, 1971 and 1980, but it seems to have progressively lost interest for election studies—hence the gap between this first series 11 and the new series which started in 1996—in a new political context, as we will see further.

23 The renaissance, so to speak, of electoral surveys, came from another academic turned journalist: Prannoy Roy. An economist by training, Roy learnt survey research in the United Kingdom. After coming back to India in the early 1980s, he applied this method to Indian elections. He co-produced a series of volumes, with Butler and Lahiri, he conducted a series of all India opinion polls for the magazine India Today, but more importantly in 1998 he founded a new television channel, New Delhi Television (NDTV) on which he anchored shows devoted to the statistical analysis of elections—thus popularizing psephology.

- 12 The CSDS entered into a stable partnership with the new channel six months before it went on air, w (...)

24 The link between these two pioneering institutions of psephology, CSDS and NDTV, was provided by Yogendra Yadav, a young political scientist who was brought from Chandigarh University to the CSDS by Rajni Kothari. Yadav revived the data unit of the CSDS and went on to supervise an uninterrupted series of electoral studies which have been financially supported and publicized by the print media, but also by NDTV. Yadav’s expertise, his great ability to explain psephological analyses both in English and Hindi, made him a star of TV shows devoted to elections, first on NDTV, and then on the channel co-founded by the star anchor Rajdeep Sardesai after he left NDTV: CNN-IBN. 12 In 1995, the CSDS team around Yogendra Yadav created Lokniti, a network of scholars based in the various Indian states, working on democracy in general and on elections in particular. The Lokniti network has been expanding both in sheer numbers and in terms of disciplines, and it has consistently observed elections since 1996.

25 In a landmark volume published in 1995 by Roy along with two other scholars, David Butler and Ashok Lahiri, the authors had made a strong statement in favour of psephology, even while acknowledging its limits: ‘This book […] offers the ‘What?’ of the electoral record; it does not deal with the ‘Why?’’ (Butler et al. 1995: 4). In this regard, the CSDS data unit has strived, from 1996 onwards, to improve its data gathering in order to capture more of the ‘Why?’, i.e. to capture with increasing accuracy the electoral behaviour of Indians and its explanatory factors. More generally, it has aimed ‘to use elections as an occasion or as a window to making sense of trends and patterns in democratic politics’ (Lokniti Team 2004: 5373).

- 13 The ‘notes on elections’ published in Electoral Studies favour a strongly institutional perspective (...)

26 The CSDS election studies have also been published in academic supports such as the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) in India, or Electoral Studies on the international level 13 , and they have been used by a large number of academic works in political sociology (for instance Jaffrelot (2008) on the vote of the urban middle classes). Recently, the Lokniti network has published a series of state election studies in Hindi and in English, with academic publishing houses (Mohan 2009, Shastri 2009).

Scientific and political debates

27 Debates around the study of Indian elections involve political and scientific arguments which are sometimes difficult to disentangle. These debates underline that no method is politically neutral, and they illustrate the particularly problematic relationship of one discipline, political science, with the political sphere and with the media.

Scientific dilemmas

28 The opposition between case studies and survey research can be broken into a series of dilemmas and choices.

29 The first dilemma concerns the most relevant unit of analysis: should one privilege width or depth? The central difficulty here is often to combine feasibility and relevance. In his introduction to a series of case studies done in the 1960s and 1970s, Shah writes:

A major limitation of the survey method is its inability to capture the influence of local politics on the electoral behavior of small communities. A questionnaire administered to individual voters can elicit information about individual attitudes and opinions but cannot capture the larger reality of events involving a collectivity of individuals acting over a longer period of time. A fieldworker who knows the community is better equipped to capture that reality (Shah 2007: 12).

- 14 Both Brass (1985) and Palshikar (2007) make a forceful argument in favour of taking the constituenc (...)

30 As we saw, case studies, focusing on a limited area, 14 do offer historical depth, for example in Brass (1985). The anthropological brand of case studies also offers ‘cultural’ depth, through a wealth of concrete details which suggest the multiple meanings of elections for voters. However survey research allows generalizations; and it contextualizes results by identifying patterns, linked to regions or social groups.

31 The second dilemma concerns quantitative vs. qualitative methods. This opposition cannot be reduced to the use of figures vs. words. While many case studies involve some quantified description of the vote, they are deeply qualitative in nature, insofar as they aim at uncovering the qualities of particular political trajectories—of a community, a party, a constituency, a state etc. Survey research on the contrary aims at revealing general patterns. Here again the question of feasibility is central: while surveys are expensive, case studies are time intensive.

- 15 For instance, the first National Election Study, conducted by the CSDS in 1967, did not take women (...)

32 An important dimension of that dilemma relates, again, to the capacity of these two types of methods to capture the meaning of elections for voters. Survey research, functioning with closed questions, conveys only the meanings that the survey design has anticipated, and risks perpetuating the prejudices of its authors. 15 By contrast, qualitative methods such as open interviews and direct observation are more likely to bring out unexpected interpretations.

33 However one large consensus appears to bridge the divide between survey research a la CSDS and case studies: the ‘ecological’ approach is preferred to the ‘strategic’ approach of elections. Ecological analyses ‘correlate electoral with other kind of aggregate data’ (Brass 1985: 3). They focus on ‘the sociological characteristics of voters, which determine the construction of their representation of politics and their social solidarity’ (Hermet et al. 2001: 31), whereas the ‘economical’ or strategic approach is based on methodological individualism and the problematic of the rational voter. Already in 1985 Paul Brass argued that ‘ecological analyses had a ‘useful place in India electoral studies’ ( ibid )—indeed he expanded on their advantages and limitations, through a detailed discussion of the methodological issues arising from the difficulty of relating electoral and census data, and of the technical solutions found by a number of works which he reviewed.

34 The evolution of National Election Studies (NES) conducted by the CSDS since 1996 shows an attempt to develop increasingly ecological types of analysis, by introducing more and more variables in their considerations. Indeed the latest surveys come close to meeting the advantages of ecological approaches as explained by Brass: ‘Identifying the underlying structural properties of party systems, […] presenting time series data to discover trends in voting behaviour, […] identifying distinctive regional contexts in which voting choices occur, and […] discovering unthought of relationships through the manipulation of available data’ (Brass 1985: 4).

35 A recent exception vis-à-vis this consensus is Kanchan Chandra’s work on ‘ethnic voting’ (Chandra 2008), which analyses electoral mobilization as a mode of negotiation used by marginal groups. Chandra argues that the poorer groups in India use their vote as ‘their primary channel of influence’. In a description of ‘elections as auctions’, she argues that the ‘purchasing power of small groups of voters’ depends ‘upon the degree to which electoral contests are competitive’ (Chandra 2004: 4). Her interpretation of the relatively high turnout in Indian elections, even as one government after the other fails the poor, is a materialist one:

16 Emphasis mine. When survival goods are allotted by the political market rather than as entitlements, voters who need these goods have no option but to participate. […] Voters do not themselves have control over the distribution of goods. But by voting strategically and voting often, they can increase their chances of obtaining these goods (Chandra 2004: 5). 16

Academic rivalries

36 The above dilemmas are extremely widespread, but in the Indian context they also correspond, to some extent, to academic rivalries between scholars and institutions, which might explain their persistence over time.

- 17 The debate on the scientific legitimacy of survey research as opposed to more theoretical, or more (...)

- 18 The preference for qualitative methods actually extends to other disciplines among social sciences (...)

- 19 In this regard, Mukherji’s account of State elections in the early 1980s in a constituency of West (...)

37 One can identify, to start with, an implicit rivalry between political science and psephology—even though the latter can be considered as a sub-discipline of the former. 17 A few texts, but also interviews, reveal a mutual distrust, both in scientific and political terms. Indian political science values theoretical work more than empirical research; qualitative more than quantitative methods; 18 politically, it favours a radical critique of the political system. 19 Survey research, of course, is essentially empirical, quantitative and ‘status quoist’. Yogendra Yadav thus sums up the situation that prevailed in the late 1980s:

The label ‘ survey research’ stood for what was considered most inappropriate in the third world imitation of American science of politics: it was methodologically naïve, politically conservative and culturally inauthentic (Yadav 2008: 3).

38 Even today, quantitative methods, which are much fashionable in American (and more lately in French) political science, are hardly taught in the political science curriculum of Indian universities. Thus Kothari’s endeavour to launch a ‘so-called ‘new political science’’ in the CSDS in the 1960s—this was the time of the behaviorist revolution in social sciences—was a lonely one. He describes this ambition thus:

[It] was mainly based on the empirical method leading to detailed analytical understanding of the political processes […] The ‘ people’ came within that framework, as voters and citizens with desires, attitudes and opinions; our task as academics was to build from there towards a macro-theory of democracy, largely through empirical surveys of political behavior (by and large limited to electoral choices) but also through broader surveys of social and political change (Kothari 2002: 60-61).

39 This project actually seems to be realized through the Lokniti network which links the CSDS data unit with a number of colleges or universities across the country (and thus contributes to training an increasingly large number of students who are then hired as investigators for National and State Election studies).

40 As far as the political agenda of survey research is concerned, Yadav makes a passionate plea for ‘transfer as transformation’ (Yadav 2008: 16) i.e. for an adaptation of survey research to the political culture of countries of the global South, with a double objective: (i) to make survey research more relevant scientifically; (ii) to use it as a politically empowering device, that is ‘[…] to ensure that subaltern and suppressed opinions are made public’ (Yadav 2008: 18).

41 Much of the latent opposition between psephologists and other political scientists is probably due to the disproportionate visibility of psephologists when compared to other social scientists working on elections. But the close connection between psephology and the media is a double edged sword. On the one hand, it offers researchers a much needed financial support:

Some of the leading media publications like the Hindu, India Today, Frontline and the Economist supported [National Election Studies] between 1996 and 1999 (Lokniti team 2004: 5375).

- 20 Thus in spite of the continuing efforts of NES to improve its methods, it failed to accurately pred (...)

42 On the other hand, it forces them to engage with the scientifically dubious, and economically risky, exercise of predicting results, 20 or explaining them immediately after their publication. However, the consistent transparency and critical self-appraisal of surveys conducted by the CSDS goes a long way in asserting their scientific credibility:

Within India, the NES series has sought to distinguish itself from the growing industry of pre-election opinion polls […] The difficulties of obtaining independent support for NES made the Lokniti group turn to media support which in turn required the group to carry out some pre-election opinion polls and even exit polls linked to seats forecast. The experiment yielded mixed results, some reasonably accurate forecasts along with some embarrassing ones (Lokniti team 2004: 5380)

- 21 See, for instance, Lokniti Team 2004, in which the methodological flaws and evolutions (in terms of (...)

43 A more explicit and constructive debate has been taking place, lately, between psephology and anthropology. Notwithstanding his refusal to ‘participate in methodological crusades on social sciences’ (Yadav 2008: 4), Yadav has consistently sought to situate, explain, improve and diffuse his brand of survey research on elections 21 . His call for a ‘dialogue’, elaborated upon by Palshikar (‘how to integrate the methods and insights of field study and survey research’ 2007: 25) has been answered by Mukulika Banerjee, who is currently directing, along with Lokniti, an unprecedented project of Comparative Electoral Ethnography, which aims at ‘bringing together the strengths of large-scale and local-level investigations’ ( www.lokniti.org/comparative_electoral_ethnography.html accessed in May 2009) .

Political issues

44 One can distinguish three types of relationship between elections studies and politics, which correspond to three distinct, if related, questions. Firstly, how do elections studies meet the need of political actors? Secondly, to what extent are they an offshoot of American political science? And thirdly, what representation of democracy do they support?

45 Firstly, the development of survey research is directly linked to Indian political life:

In the 1950s there were virtually no market research organizations in India. The dominance of the Congress diminished any incentive to develop political polls (Butler et al . 1995: 41).

46 At the time of the second non-Congress government at the Centre (1989-1991), political parties started commissioning surveys which they used to build their electoral strategy (Rao 2009). Indian elections have been decided at the state level since the 1990s, and the proliferation of national pre-poll survey from the 1991 election onwards can be linked to the uncertainty of the electoral results in a context of increasing assertion of regional parties (Rao 2009). The fact that the CSDS resumed its elections series in 1996 is doubtlessly linked to the transformations that have been characterizing the Indian political scene since the beginning of that decade. The rise to power of the Bahujan Samaj Party in Uttar Pradesh and its emergence in other North Indian states, and more generally the fragmentation of political representation, with new parties representing increasingly smaller social groups, has made it increasingly necessary to know who votes for which party in which state—and why.

47 Furthermore the decentralization policy adopted in 1992 has generated a lot of interest both from actors and observers of Indian politics. Today the newfound interest for ethnographic, locally rooted types of election studies may well have to do with the fact that the national scale is increasingly challenged as the most relevant one to understand Indian politics.

48 Secondly, a more covert, but no less important aspect of the debate relates to what could be roughly called the ‘Western domination’ of survey research. Methods have been learnt by leading Indian figures in the United States or in the United Kingdom (even in the 2000s, CSDS members get trained in the summer school in survey research in Michigan University). Authors are often American (or working in the American academia). Funding often involves foreign funding agencies.

- 22 This problem is not restricted to survey research alone: thus Mitra evokes the ‘Americanisation of (...)

- 23 Linz, Stepan and Yadav 2007 represents a good example of the changing status of the Indian case in (...)

24 See Fauvelle 2008.

49 More importantly, the key concepts of survey research are often drawn from the rich field of American election studies, 22 and particularly from behaviourism, a school of thought which is rejected by part of the Indian academia. Lastly, the general (and often implicit) reference to which the Indian scenario is compared is actually the United States and Western Europe. On the one hand, these comparative efforts 23 testify to the fact that India is not an outsider any more as far as democracies are concerned. On the other hand, one can regret an excessive focus, in comparisons, on the West, insofar as it skews the assessment of the Indian case (for instance the Indian pattern of voter turnout, which is qualified as ‘exceptional’ by Yadav because it breaks from the trend observed in North America and Western Europe, might appear less so if it was compared, say, to post-Apartheid South Africa). 24

50 Thirdly, all election studies support a (more or less implicit) discourse on Indian democracy; they can always be read as a ‘state of democracy report’ (Jayal 2006). In this regard, one of the criticisms addressed to psephological studies is that their narrow focus tends to convey a rosy picture, since elections are usually considered as ‘free and fair’ in the Indian democracy, which is often qualified as ‘procedural’, i.e. which conforms to democratic procedures (regular elections and political alternance, a free press) but not to democratic values (starting with equality). The sheer magnitude of the logistics involved in conducting national elections is bound to evoke admiring appraisals, which tend to obliterate the limits of procedural democracy. Thus Jayal criticizes the ‘the fallacy of electoralism’:

The scholars who subscribe to the limited, proceduralist view of democracy, are generally buoyant about Indian democracy... Their analyses emphatically exclude the many social and economic inequalities that make it difficult for even formal participation to be effective (Jayal 2001: 3).

51 Moreover the huge costs involved in conducting sample surveys on ever larger samples imply that the funders—which include the media—can put pressure on the team conducting the survey. And one can see two reasons why survey research is so media friendly: one, its (supposed) ability to predict results makes it an indispensable component of the horse-race, entertaining aspect of elections; two, it contributes to the ‘feel good’ factor as it shows, election after election, that the turnout is high and that results are unpredictable; it thus gives credit to the idea of democratic choice.

52 To this positive assessment, some Indian political scientists oppose the more critical vision offered by case studies of Indian politics focusing not on the mainstream, but on the margins. Here anthropology offers a way out, since the informed perspective of the long time fieldworker allows a simultaneous perception of the mainstream and of the margins. Thus the works of Hauser and Singer or that of Banerjee, offering a minute description of the various ‘ceremonies’ that together constitute the election process from the vantage point of voters, highlight both the empowering and the coercive dimensions of voting. Their studies suggest that when it comes to elections, the relationship between celebration and alienation is a very subtle one.

53 Elections are a complex, multi-dimensional social and political event which can be captured only through a variety of methods: this literature review underlines how the different approaches complete each other and are therefore equally necessary. While Indian election studies, at least at the national and state levels, have been dominated, since the 1990s, by survey research, the Lokniti based project of ‘Comparative Electoral Ethnography’ should contribute to restoring some balance between various types of studies. Also, academic debates around the scientific and political implications and limitations of election studies seem to lead to a convergence: while questionnaire-based surveys evolve towards a finer apprehension of the opinions and attitudes of Indian voters, anthropological studies strive to overcome the limitations of fieldwork based on a single, limited area.

- 25 For instance anthropological studies tend to focus on the short period comprised between the beginn (...)

54 One can regret that studies of Indian elections, by all disciplines, tend to focus exclusively on the vote, which certainly is a climactic moment of the electoral process, but by no means the only interesting one. 25 Indeed a recent attempt by the CSDS team to understand participation beyond voting, in order to qualify the ‘second democratic upsurge’ (Yadav 2000) through a state wise analysis of the 2004 Lok Sabha elections, suggests that a broader definition of the electoral process might significantly contribute to solving the ‘puzzle of Indian democracy’ (Chibber & Petrocik 1989, Lijphart 1996). They conclude that ‘comparison across social sections shows that a broader entry of the underprivileged into the political arena is much more limited, even today, than the entry of the more privileged social sections’ (Palshikar & Kumar 2004: 5414). The complementarities of different approaches are here glaring: ethnographic work is much needed to understand the implications of the fact that ‘over the years there is a steady increase in the number of people who participated in election campaign activity’ (Palshikar & Kumar 2004: 5415).

55 One wishes also that anthropological studies of future elections deal not only with the traditional elements of voting (the campaign procession, the inking of the finger etc.), but also with newer elements of the process: what has been the impact of the model code of conduct, or of the increasing use of SMS and internet in the campaign, on electoral rituals? What about the collective watching of TV shows focusing on elections, both before and after the results are known?

56 Finally, at a time when election surveys have acquired an unprecedented visibility, due to their relationship with the mass media, one can only lament the absence of rigorous studies on the role of the media, both print and audio-visual, in funding, shaping and publicizing election studies.

Bibliography

Ahuja, Amit; Chhibber, Pradeep (nd) ‘Civic Duty, Empowerment and Patronage: Patterns of Political Participation in India’, http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/polisci/cpworkshop/papers/Chhibber.pdf (accessed on 21 November, 2009).

Auyero, Javier (2006) ‘Introductory Note to Politics under the Microscope: Special Issue on Political Ethnography I’, Qualitative Sociology , 2, pp. 257-9.

Banerjee, Mukulika (2007) ‘Sacred Elections’, Economic and Political Weekly , 28 April, pp. 1556-62.

Brass, Paul (1985) Caste, Faction and Party in Indian Politics. Volume Two: Election Studies , Delhi: Chanakya Publications.

Butler, David; Lahiri, Ashok; Roy, Prannoy (1995) India Decides. Elections 1952-1995 , Delhi: Books & Things.

Chandra, Kanchan (2004) ‘Elections as Auctions’, Seminar , 539.

Chandra, Kanchan (2008) ‘Why voters in patronage democracies split their tickets: Strategic voting for ethnic parties’, Electoral Studies , 28, pp. 21-32.

Chhibber, Pradeep; Petrocik, John R.K. (1989) ‘The Puzzle of Indian Politics: Social Cleavages and the Indian Party System’, British Journal of Political Science , 19(2), pp. 191-210.

Dikshit, S.K. (1993) Electoral Geography of India, With Special Reference to Sixth and Seventh Lok Sabha Elections , Varanasi: Vishwavidyalaya Prakashan.

Eldersveld, Samuel; Ahmed, Bashiruddin (1978) Citizens and Politics: Mass Political Behaviour in India , Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fauvelle-Aymar, Christine (2008) ‘Electoral turnout in Johannesburg: Socio-economic and Political Determinants’, Transformation, Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa , 66/67, pp. 142-67.

Hauser, Walter; Singer, Wendy (1986) ‘The Democratic Rite: Celebration and Participation in the Indian Elections’, Asian Survey , 26(9), pp. 941-58.

Hermet, Guy; Badie, Bertrand; Birnbaum, Pierre; Braud, Philippe (2001) Dictionnaire de la science politique et des institutions politiques , Paris: Armand Colin.

Jaffrelot, Christophe (2008) ‘‘Why Should We Vote? ’ The Indian Middle Class and the Functioning of the World’s Largest Democracy’, in Christophe Jaffrelot & Peter Van der Veer (eds.), Patterns of Middle Class Consumption in India and China , Delhi: Sage.

Jayal, Niraja Gopal (2001) ‘Introduction’, in Niraja Gopal Jayal (ed.), Democracy in India , Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-49.

Jayal, Niraja Gopal (2006) ‘Democratic dogmas and disquiets’, Seminar , 557.

Kondo, Norio (2007) Election Studies in India , Institute of Developing Economies: Discussion Paper n°98.

Kothari, Rajni (2002) Memoirs. Uneasy is the Life of the Mind , Delhi: Rupa & Co.

Lijphart, Arend (1996) ‘The Puzzle of Indian Democracy: A Consociational Interpretation’, The American Political Science Review , 90(2), pp. 258-68.

Linz, Juan; Stepan, Alfred; Yadav, Yogendra (2007) ‘‘Nation State’ or ‘State Nation’—India in Comparative Perspective’, in Shankar K. Bajpai (ed.), Democracy and Diversity: India and the American Experience , Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 50-106.

Lokniti Team (2004) ‘National Election Study 2004: An Introduction’, Economic and Political Weekly , 18 December, pp. 5373-81.

Lyngdoh, James Michael (2004) Chronicle of an Impossible Election: The Election Commission and the 2002 Jammu and Kashmir Assembly Elections , Delhi: Penguin/Viking.

Mitra, Subrata K. (1979) ‘Ballot Box and Local Power: Electoral Politics in an Indian Village’, Journal of Commonwealth and Comparative Politics , 17(3), pp. 282-99.

Mitra, Subrata K. (2005) ‘Elections and the Negotiation of Ethnic Conflict: An American Science of Indian Politics?’, India Review , 24, pp. 326-43.

Mohan, Arvind (ed.) (2009) Loktantra ka Naya Lok , Delhi: Vani Prakashan.

Mukherji, Partha N. (1983) From Left Extremism to Electoral Politics: Naxalite Participation in Elections , New Delhi: Manohar.

Narain, Iqbal; Pande, K.C.; Sharma, M.L.; Rajpal, Hansa (1978) Election Studies in India: An Evaluation , New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

Palshikar, Suhas; Kumar, Sanjay (2004) ‘Participatory Norm: How Broad-based Is It?’, Economic and Political Weekly , 18 December, pp. 5412-17.

Palshikar, Suhas (2007) ‘The Imagined Debate between Pollsters and Ethnographers’, Economic and Political Weekly , 27 October, pp. 24-8.

Rao, Bhaskara (2009) A Handbook of Poll Surveys in Media: An Indian Perspective , Delhi: Gyan Publications.

Roy, Ramashray; Wallace, Paul (1999) Indian Politics and the 1998 Election: Regionalism, Hindutva and State Politics , New Delhi, Thousand Oaks, London: Sage Publications.

Saez, Lawrence (2001) ‘The 1999 General Election in India’, Electoral Studies , 20, pp. 164-9.

Shah, A.M. (2007) ‘Introduction’, in A.M. Shah (ed.), The Grassroots of Democracy: Field Studies of Indian Elections , Delhi: Permanent black, pp. 1-27.

Shastri, Sandeep; Suri, K.C.; Yadav, Yogendra (2009) Electoral Politics in Indian States: Lok Sabha Elections in 2004 and Beyond , Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Singer, Wendy (2007) ‘A Constituency Suitable for Ladies’ And Other Social Histories of Indian Elections , New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Somjee, A.H. (1959) Voting Behaviour in an Indian Village , Baroda: M.S.University.

Sundar, Nandini; Deshpande, Satish; Uberoi, Patricia (2000) ‘Indian Anthropology and Sociology: Towards a History’, Economic and Political Weekly , 10 June, pp. 1998-2002.

Weiner, Myron (1978), India at the Polls. The Parliamentary Elections of 1977 , Washington D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

Yadav, Yogendra (2000) ‘Understanding the Second Democratic Upsurge: Trends of Bahujan Participation in Electoral Politics in the 1990s’, in Francine R. Frankel; Zoya Hasan; Rajeev Bhargava; Balveer Arora (eds.), Transforming India: Social and Political Dynamics of Democracy , Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Yadav, Yogendra (2007) ‘Invitation to a dialogue: What work does ‘fieldwork’ do in the field of elections?’, in A.M. Shah (ed.), The Grassroots of Democracy: Field Studies of Indian Elections , Delhi: Permanent black, pp. 345-68.

Yadav, Yogendra (2008) ‘Whither Survey Research? Reflections on the State of Survey Research on Politics in Most of the World’, Malcom Adiseshiah Memorial Lecture, Chennai.

1 Most works considered here deal with national elections, but some of them also focus on state elections.

2 I owe this formulation to Amit Prakash, whose comments on a previous version of this paper were very helpful.

3 Another example is a study of parliamentary and state elections in a village in Orissa at the end of Emergency, in which S. Mitra describes the caste dynamics in the village and the way it plays out during electoral times to show how ‘elections are used as instruments by various sections of the society to convert their political resources and power into authority’ (Mitra 1979: 419).

4 In the early years of independent India, the Indian Council for Social Science Research (ICSSR) commissioned a series of case studies, some of which are reviewed by Narain (1978). A more recently published volume offers a sample of such studies, conducted in the late 1960s by the sociology department of Delhi University under the supervision of M.N.Srinivas and A.M.Shah (Shah 2007).

5 One must note that among the various disciplines producing case studies, anthropology uses the largest definition of political participation, to include not only voting, but also participating in meetings, supporting the campaign of a particular party or candidate etc.

6 One must also mention the ‘Chronicle of an Impossible Election’— i.e. the 2002 Assembly election in Jammu and Kashmir - as told by the then Chief Election Commissioner, J.M. Lyngdoh (2004), which provides an insider’s view of how election procedures are the result of a series of (sometimes minute) decisions—aiming at asserting that the Election Commission does not represent the Indian government.

7 This is in sharp contrast with France, where electoral geographers such as André Siegfried have been the founding fathers of political science. For an illustration of how geography enriches our understanding of elections, see Lefèbvre and Robin in this volume.

8 This inventory of ‘ other’ election studies, that is, studies of elections that fall neither in the ‘case study’ nor in the ‘survey research’ type, would obviously become much more complex and large if we were to include in it the large body of literature on the party system, or on the federal structure as they evolve over time in India. However that literature does take elections as its main focus, and has therefore not been considered here.

10 The CSDS was meant, in Kothari’s own words: ‘One, to give a truly empirical base to political science [...] Two, to engage in a persistent set of writings through which our broad conceptualisation of democracy in India was laid out [...] And three, institutionalise not just the Centre as a place of learning but as part of the larger intellectual process itself’ (Kothari 2002: 39-40). Over the years, the CSDS has retained a unique place in the Indian academia, as it remains distinct from universities even while engaging in a number of collaborations with their faculty—Lokniti being a case in point.

11 The CSDS did not even study the 1977 election, on which we fortunately have Myron Weiner’s monograph.

12 The CSDS entered into a stable partnership with the new channel six months before it went on air, which testifies to the saleability of this brand of research. One week before the results of the Fifteenth election were announced, huge signboards bore a picture of the star anchor of CNN-IBN along with Yogendra Yadav, asserting the latter’s increasing popularity.

13 The ‘notes on elections’ published in Electoral Studies favour a strongly institutional perspective, concerned almost exclusively with political parties (the alliances they form, the issues they raise, the candidates they select etc.) Interestingly, nothing is said about voters.

14 Both Brass (1985) and Palshikar (2007) make a forceful argument in favour of taking the constituency as a unit of analysis.

15 For instance, the first National Election Study, conducted by the CSDS in 1967, did not take women voters into account! (Lokniti team 2004: 5374).

16 Emphasis mine.

17 The debate on the scientific legitimacy of survey research as opposed to more theoretical, or more qualitative, approaches is by no means restricted to India. Political science is a relatively young discipline, defined more by its objects than by its methods, and by a scientific community that strives to assert its scientific credentials. In this regard, electoral surveys have an ambiguous record. On the one hand, the highly technical aspect of quantitative methods gives an image of ‘scientificity’; on the other hand, the proximity (in terms of sponsors, institutions and publication supports) of electoral surveys to opinion polls (characterized by a large margin of error, and a close association with marketing techniques) maintains a doubt on the scientificity of this sub-discipline.

18 The preference for qualitative methods actually extends to other disciplines among social sciences in India: ‘A tabulation of articles in Contributions to Indian Sociology and the Sociological Bulletin [...], though not a comprehensive account of scholarship in sociology and social anthropology, did nevertheless seem to substantiate the fact that ethnographic methods far outpaced any other kind of research method’ (Sundar et al. 2000: 2000).

19 In this regard, Mukherji’s account of State elections in the early 1980s in a constituency of West Bengal dominated by Naxalites is an exception among monographic studies of elections. The book offers a candid evocation of the methodological dilemmas, constraints and solutions inherent in studying elections, and particularly of the political agenda behind election studies (in this particular case, the author, engaged in a study of the Naxalite movement, presents himself early on as a Naxalite) (Mukherji 1983).

20 Thus in spite of the continuing efforts of NES to improve its methods, it failed to accurately predict the results of elections, both in 2004 and in 2009.

21 See, for instance, Lokniti Team 2004, in which the methodological flaws and evolutions (in terms of sample size, number of languages used, decentralization of data entry and analysis etc.) of National Election Studies are discussed in detail.

22 This problem is not restricted to survey research alone: thus Mitra evokes the ‘Americanisation of [the study of] ethnic politics in the Indian context’ (Mitra 2005: 327)

23 Linz, Stepan and Yadav 2007 represents a good example of the changing status of the Indian case in comparative studies of democracy—from an exception to a major case.

25 For instance anthropological studies tend to focus on the short period comprised between the beginning of the electoral campaign and the announcement of results. A larger timeframe is needed if we are to understand how clientelism operates through the electoral process.

Electronic reference

Stéphanie Tawa Lama-Rewal , “ Studying Elections in India: Scientific and Political Debates ” , South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], 3 | 2009, Online since 23 December 2009 , connection on 19 April 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/2784; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj.2784

About the author

Stéphanie tawa lama-rewal.

Research fellow, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris

By this author

- Niraja Gopal Jayal, Citizenship and its Discontents: An Indian History [Full text] Published in South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Book Reviews

- Introduction. Urban Democracy: A South Asian Perspective [Full text] Published in South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , 5 | 2011

- Introduction. Contextualizing and Interpreting the 15 th Lok Sabha Elections [Full text] Published in South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , 3 | 2009

The text only may be used under licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 . All other elements (illustrations, imported files) are “All rights reserved”, unless otherwise stated.

- Book Reviews

Full text issues

- 30 | 2023 The Digitalization of Urban Governance in India

- 29 | 2022 South Asia in Covid Times

- 28 | 2022 Subalternity, Marginality, Agency in Contemporary India

- 27 | 2021 Political Mobilizations of South Asians in Diaspora: Intertwining Homeland Politics and Host-Society Politics

- 26 | 2021 Engaging the Urban from the Periphery

- 24/25 | 2020 The Hindutva Turn: Authoritarianism and Resistance in India

- 23 | 2020 Unique Identification in India: Aadhaar, Biometrics and Technology-Mediated Identities

- 22 | 2019 Student Politics in South Asia

- 21 | 2019 Representations of the “Rural” in India from the Colonial to the Post-Colonial

- 20 | 2019 Sedition, Sexuality, Gender, and Gender Identity in South Asia

- 19 | 2018 Caste-Gender Intersections in Contemporary India

- 18 | 2018 Wayside Shrines: Everyday Religion in Urban India

- 17 | 2018 Through the Lens of the Law: Court Cases and Social Issues in India

- 16 | 2017 Changing Family Realities in South Asia?

- 15 | 2017 Sociology of India’s Economic Elites

- 14 | 2016 Environment Politics in Urban India: Citizenship, Knowledges and Urban Political Ecologies

- 13 | 2016 Land, Development and Security in South Asia

- 12 | 2015 On Names in South Asia: Iteration, (Im)propriety and Dissimulation

- 11 | 2015 Contemporary Lucknow: Life with ‘Too Much History’

- 10 | 2014 Ideas of South Asia

- 9 | 2014 Imagining Bangladesh: Contested Narratives

- 8 | 2013 Delhi's Margins

- 7 | 2013 The Ethics of Self-Making in Postcolonial India

- 6 | 2012 Revisiting Space and Place: South Asian Migrations in Perspective

- 5 | 2011 Rethinking Urban Democracy in South Asia

- 4 | 2010 Modern Achievers: Role Models in South Asia

- 3 | 2009 Contests in Context: Indian Elections 2009

- 2 | 2008 ‘Outraged Communities’

- 1 | 2007 Migration and Constructions of the Other

Other Contributions

- Free-Standing Articles

- What is SAMAJ?

- Editorial Board

- Advisory Board

- Partnership with EASAS

- Information for authors

- Publication Ethics and Malpractice Statement

- Subscribe to our newsletter

Informations

- Publishing policies

Newsletters

- OpenEdition Newsletter

In collaboration with

- Journal supported by the Institut des sciences humaines et sociales (InSHS) of the CNRS, 2023-2024

Electronic ISSN 1960-6060

Read detailed presentation

Site map – Syndication

Privacy Policy – About Cookies – Report a problem

OpenEdition member – Published with Lodel – Administration only

You will be redirected to OpenEdition Search

Application of Twitter sentiment analysis in election prediction: a case study of 2019 Indian general election

- Original Article

- Published: 18 May 2023

- Volume 13 , article number 88 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Priyavrat Chauhan 1 ,

- Nonita Sharma 2 &

- Geeta Sikka 3

753 Accesses

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 12 June 2023

This article has been updated

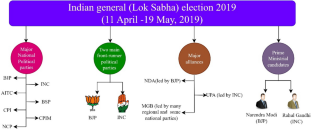

Everyone must have experienced a huge collection of political content on their social media account’s home page during election time. Most of the users are busy in liking, sharing, and commenting political posts on the social media platform at that time, and these user activities show their attitude or behaviour towards the electoral or the political party. This study has mined the collective behaviour of Twitter users towards the Indian General election 2019. This work performed weekly sentiment analysis of massive Twitter content related to electoral and political parties during election time using a lexicon-based sentiment analysis approach. Based on this empirical study, the aim is to find out the feasibility of election prediction through social media analysis in a developing country like India. Further, an explorative analysis has been performed on the collected data, which gives answers to some dominant research hypotheses formulated in this paper. This paper shows how public mood can be gauged from social media content during the election period and how it can be considered as a parameter to predict the election results along with other factors. In addition, results evaluation has been done based on mean absolute error by considering the vote share and seat share of competing parties and leaders in the election. The predicted result of this work has been compared with exit poll results from various news agencies and the actual election result. It was found that our result of election prediction is quite similar to the final election results.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Sentiment Analysis in Social Media Data for Depression Detection Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review

Nirmal Varghese Babu & E. Grace Mary Kanaga

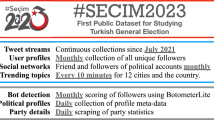

First public dataset to study 2023 Turkish general election

Ali Najafi, Nihat Mugurtay, … Onur Varol

Analyzing voter behavior on social media during the 2020 US presidential election campaign

Loris Belcastro, Francesco Branda, … Paolo Trunfio

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

10 june 2023.

The original article is revised to update Equation 7 and some missed out corrections

12 June 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01096-7

RCP is a website ( https://www.realclearpolitics.com/ ) that predicts election results by calculating the average of many popular media and survey institutes.

AL Dayel A, Magdy W (2021) Stance detection on social media: state of the art and trends. Inf Process Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102597

Article Google Scholar

Agarwal A, Toshniwal D, Bedi J (2020) Can Twitter help to predict outcome of 2019 Indian General Election: a deep learning based study. In: Communications in computer and information science, pp 38–53

Ahmed S, Skoric MM (2014) My name is Khan: the use of twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan general election. In: Proceedings of the annual hawaii international conference on system sciences, IEEE, pp 2242–2251

Ain QT, Ali M, Riaz A et al (2017) Sentiment analysis using deep learning techniques: a review. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 8:424–433

Google Scholar

Al Zamal F, Liu W, Ruths D (2012) Homophily and latent attribute inference: inferring latent attributes of Twitter users from neighbors. In: ICWSM 2012—Proceedings of the 6th international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media, pp 387–390

Awais M, Hassan S-U, Ahmed A (2021) Leveraging big data for politics: predicting general election of Pakistan using a novel rigged model. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 12:4305–4313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-019-01378-z

BBC News (2019) Balakot: Indian air strikes target militants in Pakistan. Accessed 31 Jan 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47366718

Bansal B, Srivastava S (2018) On predicting elections with hybrid topic based sentiment analysis of tweets. Procedia Computer Science 135:346–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.183

Bansal B, Srivastava S (2019) Lexicon-based twitter sentiment analysis for vote share prediction using emoji and N-gram features. Int J Web Based Communities 15:85–99. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWBC.2019.098693

Batista-Navarro RT, Kontonatsios G, Mihǎilǎ C et al (2013) Facilitating the analysis of discourse phenomena in an interoperable NLP platform. Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics) 7816 LNCS:559–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37247-6_45

Bermingham A, Smeaton AF (2011) On Using Twitter to monitor political sentiment and predict election results. In: Proceedings of the workshop on sentiment analysis where AI meets Psychology (SAAIP 2011), pp 2–10

Budiharto W, Meiliana M (2018) Prediction and analysis of Indonesia Presidential election from Twitter using sentiment analysis. J Big Data. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-018-0164-1

Burnap P, Gibson R, Sloan L et al (2016) 140 characters to victory?: using twitter to predict the UK 2015 general election. Elect Stud 41:230–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ELECTSTUD.2015.11.017

Cambria E (2016) Affective computing and sentiment analysis. IEEE Intell Syst 31:102–107. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2016.31

Cambria E, Ebrahimi M, Hossein Yazdavar A et al (2017) Challenges of sentiment analysis for dynamic events. IEEE Intell Syst 32:70–75. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2017.3711649

Ceron A, Curini L, Iacus SM (2015) Using Sentiment analysis to monitor electoral campaigns: method matters—evidence from the United States and Italy. Soc Sci Comput Rev 33:3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314521983

Chauhan P, Sharma N, Sikka G (2021) The emergence of social media data and sentiment analysis in election prediction. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 12:2601–2627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-020-02423-y

Chauhan P, Singh AJ (2017) Sentiment analysis: a comparative study of supervised machine learning algorithms using rapid miner. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol V. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2017.11011

Chen L, Chen CLM, Lee C, Chen M (2019) Exploration of social media for sentiment analysis using deep learning. Soft Comput 24:8187–8197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-019-04402-8

Clement J (2020) Twitter: most users by country. Accessed 12 Aug 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/242606/number-of-active-twitter-users-in-selected-countries/

Corchs S, Fersini E, Gasparini F (2019) Ensemble learning on visual and textual data for social image emotion classification. Int J Mach Learn Cybern 10:2057–2070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-017-0734-0

D’Andrea A, Ferri F, Grifoni P, Guzzo T (2015) Approaches, tools and applications for sentiment analysis implementation. Int J Comput Appl 125:26–33. https://doi.org/10.5120/ijca2015905866

ECI (2019a) HIGHLIGHTS—General Election 2019a—Election Commission of India. Accessed 30 Oct 2019a. https://eci.gov.in/files/file/10991-2-highlights/

ECI (2019b) PC wise distribution of votes polled. Accessed 20 Aug 2021. https://eci.gov.in/files/file/10967-14-pc-wise-distribution-of-votes-polled/

Fang A, Ounis I, Habel P, et al (2015) Topic-centric classification of twitter user’s political orientation. In: Proceedings of the 38th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval—SIGIR’15. ACM Press, New York, pp 791–794

Gayo-Avello D (2012b) No, you cannot predict elections with twitter. IEEE Internet Comput 16:91–94. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2012.137

Gayo-Avello D (2013) A meta-analysis of state-of-the-art electoral prediction from twitter data. Soc Sci Comput Rev 31:649–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313493979

Gayo-Avello D (2012a) “I wanted to predict elections with twitter and all i got was this lousy paper”—a balanced survey on election prediction using twitter data, pp 1–13

Gayo-avello D, Metaxas PT, Mustafaraj E (2011) Limits of electoral predictions using social media data. In: Fifth international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media

Gentry J (2016) Package ‘twitteR’. Accessed 5 Jan 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/twitteR/twitteR.pdf

Habimana O, Li Y, Li R et al (2020) Sentiment analysis using deep learning approaches: an overview. Sci China Inf Sci 63:1–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11432-018-9941-6

Hemmatian F, Sohrabi MK (2017) A survey on classification techniques for opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Artif Intell Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-017-9599-6

Hindu T (2019a) Modi insulting Army by questioning UPA era strikes: Congress. Accessed 1 Jul 2019a. https://www.thehindu.com/elections/lok-sabha-2019/modi-is-insulting-army-by-questioning-upa-era-strikes/article27028372.ece

Huddar MG, Sannakki SS, Rajpurohit VS (2019) A Survey of computational approaches and challenges in multimodal sentiment analysis. Int J Comput Sci Eng 7:876–883. https://doi.org/10.26438/ijcse/v7i1.876883

Idan L, Feigenbaum J (2019) Show me your friends and I will tell you whom you vote for. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM international conference on advances in social networks analysis and mining, ACM Press, New York, pp 816–824

India Today (2019) NDA, UPA and others: who’s friends with whom as things stand, explained. Accessed 18 Jul 2019. https://www.indiatoday.in/elections/lok-sabha-2019/story/nda-upa-others-alliances-lok-sabha-polls-2019-1528855-2019-05-19

Jaidka K, Ahmed S, Skoric M, Hilbert M (2019) Predicting elections from social media: a three-country, three-method comparative study. Asian J Commun 29:252–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1453849

JavanAmoli A, Bagheri A (2016) A review of studies conducted in opinion mining. Spec J Electron Comput Sci 2:71–83

Jungherr A, Jungherr A (2016) Twitter use in election campaigns : a systematic literature review. J Inform Tech Polit 13:72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

Karthikeyan S (2019) The federal front: what is it and can it succeed in being an alternative to the NDA Or UPA once the 2019 Lok Sabha results are announced?. Accessed 20 Aug 2019. https://www.republicworld.com/election-news/indian-general-elections/the-federal-front-what-is-it-and-can-it-succeed-in-being-an-alternative-to-the-nda-or-upa-once-the-2019-lok-sabha-results-are-announced.html

Keramatfar A, Amirkhani H (2019) Bibliometrics of sentiment analysis literature. J Inf Sci 45:3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551518761013

Khan A, Zhang H, Boudjellal N et al (2021) Election prediction on twitter: a systematic mapping study. Complexity 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5565434

Khatua A, Khatua A, Ghosh K, Chaki N (2015) Can #Twitter_Trends predict election results? Evidence from 2014 indian general election. 2015 48th Hawaii international conference on system sciences. IEEE, New York, pp 1676–1685

Chapter Google Scholar

Lai M, Cignarella AT, Hernández Farías DI et al (2020) Multilingual stance detection in social media political debates. Comput Speech Lang 63:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2020.101075

Ligthart A, Catal C, Tekinerdogan B (2021) Systematic reviews in sentiment analysis: a tertiary study. Artif Intell Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-09973-3

Liu T, Ding X, Chen Y et al (2016) Predicting movie Box-office revenues by exploiting large-scale social media content. Multimed Tools Appl 75:1509–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-014-2270-1

Liu H, Member S, Chatterjee I et al (2020) Aspect-based sentiment analysis : a survey of deep learning methods. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 7:1358–1375

LokSabha (2020) Lok Sabha. Accessed 7 Sep 2020. https://loksabha.nic.in/

Loria Steven (2020) textblob Documentation Release 0.16.0. Accessed from. https://textblob.readthedocs.io/en/dev/authors.html

Makazhanov A, Rafiei D, Waqar M (2014) Predicting political preference of twitter users. Soc Netw Anal Min 4:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-014-0193-5

Medhat W, Hassan A, Korashy H (2014) Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: a survey. Ain Shams Eng J 5:1093–1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2014.04.011

Metaxas PT, Mustafaraj E, Gayo Avello D (2011) How (Not) to Predict Elections. 2011 IEEE third int’l conference on privacy, security, risk and trust and 2011 IEEE third int’l conference on social computing. IEEE, New York, pp 165–171

Mäntylä MV, Graziotin D, Kuutila M (2018) The evolution of sentiment analysis—a review of research topics, venues, and top cited papers. Comput Sci Rev 27:16–32

Nazir F, Ghazanfar MA, Maqsood M et al (2019) Social media signal detection using tweets volume, hashtag, and sentiment analysis. Multimed Tools Appl 78:3553–3586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-6437-z

Pennacchiotti M, Popescu A-M (2011) Democrats, republicans and starbucks afficionados. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining—KDD ’11. ACM Press, New York, p 430

Prasetyo ND, Hauff C (2015) Twitter-based election prediction in the developing world. In: HT 2015—proceedings of the 26th ACM conference on hypertext and social media, pp 149–158

Preotiuc Pietro D, Hopkins DJ, Liu Y, Ungar L (2017) Beyond binary labels: political ideology prediction of twitter users. ACL 2017 55th Annu Meet Assoc Comput Linguist Proc Conf (long Pap) 1:729–740. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P17-1068

Priyavrat SN, Sikka G (2021) Multimodal sentiment analysis of social media data: a review. In: Singh PK, Singh Y, Kolekar MH et al (eds) Recent innovations in computing. Springer, Singapore, pp 545–561

Ramani S (2019) Analysis: highest-ever national vote share for the BJP—The Hindu. Accessed 13 Jul 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/elections/lok-sabha-2019/analysis-highest-ever-national-vote-share-for-the-bjp/article27218550.ece

Rao D, Yarowsky D, Shreevats A, Gupta M (2010) Classifying latent user attributes in twitter. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international workshop on Search and mining user-generated contents SMUC 10, ACM Press, New York, pp 37–44

Sanga A, Samuel A, Rathaur N et al (2020) Bayesian prediction on PM Modi’s future in 2019. Lecture notes in electrical engineering. Springer, Charm, pp 885–897

Sharma V (2019a) 2019 Vs 2014: how much votes BJP and Congress got? Here is the comparison. Accessed 17 Jun 2019. https://english.newsnationtv.com/election/lok-sabha-election-2019/2019-vs-2014-how-much-votes-bjp-and-congress-got-here-is-the-comparison-225589.html

Sharma V (2019b) Here is complete list of BJP-led NDA candidates for Lok Sabha Elections 2019b. Accessed 21 Jun 2019. https://english.newsnationtv.com/election/lok-sabha-election-2019/here-is-complete-list-of-nda-candidates-for-lok-sabha-elections-2019-219182.html