Sociology of Poverty: Functionalist and Conflict Perspectives

Defining Poverty : Poverty is the state of being financially incapable of affording the essentials for the prevailing standard of living (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). Within this understanding of poverty, the prevailing standard of living and basic human needs, while overlapping are not synonymous. Basic human needs include goods that are necessary for survival, ie. food, water and shelter. While the prevailing standard of living, as defined by economist Elizabeth Ellis Hoyt- is not material things consumed but instead are the sum-total, not of things, but of satisfaction attained (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). From this definition, one can go about understanding poverty, not in absolutes but in relative terms, being in poverty is relative to how everyone else in a society/country lives. This is part of the reason why the poverty line differs from country to country. The first reason being that cost of living (ie. cost of goods and services) differ. But also because the prevailing standard of living differs (CrashCourse, 2017).

Taking this definition of poverty as the foundation, this paper will analyse poverty from two major sociological perspectives. These perspectives aim to look at the structure of society and how the prevailing structure causes or allows for the existence of poverty. The essay will compare and contrast the analysis of the two theories, however, the aim of the comparison is not to state which theory is superior. Instead, how the two theories differ and at times build on each other.

Functionalism & Poverty

Defining functionalism: Functionalists view society as if it were a machine, that singular aspect of society (ie. social structure) performs a function that is indispensable to the smooth running of said society. Hence, any ‘dysfunction’ of any aspect of society is a deviation from the norm and hence will need to be fixed. Proposed by 19th-century french sociologist Emile Durkheim every aspect or structure in society performs a function in society- either a latent or a manifest function. Manifest functions are the intended consequences of a social structure, while latent functions are unintentional. For example, one of the societies’ most prominent and primal social structures is the family (CrashCourse, 2017). The latent function of a family includes providing financial and emotional support, socialization, etc. these are the functions that are expected of a family, on the other hand, latent functions of a family could include stimulating the economy and paying taxes (Vibal, 2014). These are functions that support other social structures. Hence, the social structure of society fulfils the manifest function of supporting everyone within the structure (ie. the members of the family) and the latent function of supporting (as per the aforementioned example) the social structure that is the economy and the government. Lastly, if a function performed by a social structure is harmful to society, that function is referred to as dysfunctions- effects that disrupt the smooth operating of society (Nicki Lisa Cole, 2020).

Functionalism and Poverty: On the surface, poverty appears to be a dysfunction, however, according to Durkheim this is untrue stating instead that poverty or social inequality is necessary for the smooth functioning of society. This view on poverty can be better recognized by understanding the functionalist perspective on social stratification, specifically class stratification. According to the David-Moore thesis, stratification and inequality are necessary and beneficial to society to motivate individuals to train for and perform complex roles (Bell). And that the basis of class inequality is dependant on the degree of benefit that each occupation to society as well as the degree of complexity a job possesses. The if an occupation offers a great benefit to society then that occupation is considered valuable (LumenLearning). For example, the job of a doctor is complex, the basis on which this complexity is derived is that medical training and education average 10 years. Additionally, doctors offer a service that is core to survival and can not be replaced, hence the job of a doctor is both valuable as well as complex. To conclude the David-Moore thesis, a job that is valuable and complex needs to be economically and socially rewarded. It is the varying degrees of social and economic reward that causes class stratification.

In summary, the crux of the David-Moore thesis is that social stratification and as extension poverty is necessary because it performs a (latent) function and not a disfunction. The existence of stratification is based on occupation means that individuals will strive towards occupations that best suit them, as well as occupations that offer the most benefit to society, as it is these jobs that bring about the most rewards.

Criticism: The most prominent criticism of this theory is that it does not take into consideration how other social stratifying factors; such as race, gender, access to education, generational wealth, etc, can play a role in the occupation and ultimately the class one falls into (LumenLearning). The theory instead is built on the assumption that society is egalitarian and the only differentiating factor is an individual’s desire. Another prominent criticism is that oftentimes the relationship between social benefit and socio-economic reward is not consistent. This is best highlighted in occupations within media and entertainment, for example, actors do not necessarily require a high level of education nor do they offer a societal reward greater than teachers. Regardless, actors gain higher socio-economic rewards than teachers. Lastly, while the David-Moore thesis offers a way in which one can measure socio-economic reward (income and opportunity), as well as offers a measure of complexity on the basis of education. However, it does not offer an absolute manner by which one can measure societal benefit, nor is the correlation between complexity or income always positive. For example, a teacher who specialises in educating individuals with learning disabilities has more educational requirements, but will ultimately work with fewer people, there is no way to say whether this implies that a teacher who specializes in this field offers greater societal benefit than a general teacher.

Conflict Theory & Poverty

Defining conflict theory: Proposed by Marx and Engels, conflict theory is the sociological theory that looks at society in terms of a power struggle between groups within society over limited resources, under a post-industrialised capitalist society these resources are the modes of production (Hayes, 2021). The struggle for power is what Marx states as ultimately resulting in societal change ie. historical materialism (CrashCourse, 2017). While conflict theory can be applied to any number of sociological studies such as gender, race, etc, the first and most prominent use of conflict theory is the study of class conflict. Here the two competing groups are the proletariat (the working class) and the bourgeois (the capitalist class), who are struggling overpower which manifests as the means of production. Marx states this conflict between classes as the central conflict in society and the source of social inequality in power and wealth (CrashCourse, 2017). The emphasis on resources as the base of power can not be overstated, those who own the modes of production will then ultimately also have control over societies superstructure- culture, norms, politics, religion, etc . Hence, the superstructure grows out of the base and reflects the ruling class’ interests. As such, the superstructure justifies how the base operates through exploitation and keeps the power in the hands of the elite (Cole, 2020).

Conflict theory and poverty: Unlike functionalism’s viewpoint of class stratification and poverty being necessary to society, conflict theory argues the opposite. Stating instead that social stratification does not benefit society as a whole but instead only a small section- the bourgeoise. Acknowledging this inequality and the root of said inequality is only one facet of conflict theory’s analysis of poverty, another focal point is how this power or ownership occurs in the first place. Another key distinguishing factor is that the functionalist perspective makes the assumption that individuals who are highly skilled and trained will be able to gain high socio-economic rewards, and ultimately avoid poverty (Barkan, 2018). However, from the perspective of conflict theory, class stratification is caused by a lack of opportunity that an individual is born into. Implying that individuals are either born into the bourgeoisie or the proletariat class (Barkan, 2018). In this way conflict theory actively acknowledges and addresses the critique that functionalism fails to.

By exploiting the superstructures the bourgeois is able to maintain their hold on the means of production, this exploitation is broadly two-fold. The proletariat being the class that performs manual labour to produce goods, ie. without the proletariat’s class, the means of production owned by the bourgeois would be powerless. In spite of this, the bourgeoise undervalues this labour by underpaying the proletariat, ultimately allowing for the bourgeois to hold power. The second method is through what Marx refers to as alienation , this is the process by the working conditions and constant exploitation faced by the workers leaves them isolated and unable to work in solidarity to fight for power. According to this theory, the only way for the proletariat class to escape the position as the oppressed class is to gain the means of production.

Criticism: Conflict theories primary criticism is its emphasis on a two-group system, which is a system that is continually losing relevance. For example, there are many small business owners, who according to Marx would be considered part of the bourgeoisie, despite their standard living and power (especially when it comes to influencing the superstructure) being more in line with the working class.

Also Read: 6 Complementary Perspectives in Sociology and Examples

Comparing the theories

Similarly to how conflict theory is able to address the faults of the functionalist perspective on poverty, the same occurs inversely. It is conflict theories’ emphasis on change through struggle that results in neglecting to consider the importance of societal stability. According to American sociologist Herbert J. Gans, poverty continues to exist because it is functional for society (Barkan, 2018). In fact, some of these (latent) functions benefit those in poverty, the very existence of poverty is a source of employment for physicians, attorneys, and other professionals who provide services to the poor. Some critics acknowledge that societies are in a constant state of change, but point out that much of the change is often minor, not revolutionary (Boundless). For example, many modern capitalist states have avoided a communist revolution, and have instead instituted elaborate social service programs (Boundless).

Bibliography

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Poverty. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/poverty.

YouTube. (2017). Social Class & Poverty in the Us: Crash Course Sociology #24. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c8PEv5SV4sU&t=331s .

YouTube. (2017). Major Sociological Paradigms: Crash Course Sociology #2. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DbTt_ySTjaY.

Vibal, B. (2014). Manifest and latent functions of a family. prezi.com. https://prezi.com/uqqn3fywuyji/manifest-and-latent-functions-of-a-family/.

Nicki Lisa Cole, P. D. (2020). How sociology helps us study intended and unintended consequences. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/manifest-function-definition-4144979.

Bell, K. (n.d.). Davis-Moore thesis definition. Open Education Sociology Dictionary. https://sociologydictionary.org/davis-moore-thesis/#definition_of_davis-moore_thesis.

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Theoretical Perspectives on Social Stratification. Lumen. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/alamo-sociology/chapter/reading-theoretical-perspectives-on-social-stratification/.

Hayes, A. (2021, July 27). Conflict theory definition. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/conflict-theory.asp.

Cole, N. L. (2020). Learn to understand Marx’s base and superstructure. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-base-and-superstructure-3026372.

Barkan, S. (2018). The Conflict Approach. In A. Treviño (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Social Problems (pp. 241-258). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108656184.015

Boundless. (n.d.). Boundless sociology. Lumen. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-sociology/chapter/theoretical-perspectives-in-sociology/.

Natasha Dmello

Natasha D'Mello is currently a communications and sociology student at Flame University. Her interests include graphic design, poetry and media analysis.

Main navigation

- Child poverty

- Cost of living

- Deep poverty and destitution

- Savings, debt and assets

- Social security

- Imagination infrastructures

- Neighbourhoods and communities

- Race and ethnicity

- AI for public good

- Political mindsets

- Wealth, funding and investment practice

- Press office

- Vision, mission and principles

- Background and history

- Our trustees

- Governance information

- Social investments

This report discusses contested concepts that relate to how we might understand poverty from a sociological/social theory perspective. It finds that:

- some sociologists have tended to explain poverty by referring to people’s moral failings, fecklessness or dependency cultures, while others have argued that it can be better understood as a result of how resources and opportunities are unequally distributed across society;

- some sociologists have pointed to the declining influence of social class in the UK, yet research shows that social class and processes of class reproduction remain important – the opportunities open to people are still influenced, to a large extent, by their social class positions;

- sociologists point to the importance of stigma and shame in understanding the experience of poverty; and

- the ways that those experiencing poverty can be negatively stereotyped by institutions such as public or welfare delivery services has also been shown to be important in stigmatising and disadvantaging those experiencing poverty.

This report is one of four reviews looking at poverty from different perspectives.

- Sociological thinking focuses on the structure and organisation of society and how this relates to social problems and individual lives.

- In looking to explain poverty, sociologists have often tried to balance the relative importance of social structures (how society is organised) and the role of individual agency – people’s independent choices and actions.

- Sociologists are interested in how resources in society are distributed.

- Some sociologists, especially those writing in the 1970s and 1980s, have tended to explain poverty by referring to people’s moral failings, fecklessness or dependency cultures. Others have argued that poverty can be better understood as a result of the ways in which resources and opportunities are unequally distributed across society.

- Some sociologists have pointed to the declining influence of social class in the UK. Yet research has shown that social class and processes of class reproduction remain important, particularly for the continuity of poverty over time and across generations.

- On a related topic, sociologists have pointed to the importance of stigma and shame in understanding the experience of poverty. A particular concern is with how the spending patterns of those in the greatest poverty are often subject to stigmatisation.

- The ways in which institutions such as public or welfare delivery services can negatively stereotype those experiencing poverty has also been shown to be important in stigmatising and disadvantaging those experiencing poverty.

- To a large extent, people’s social class positions still influence the opportunities open to them. Starting out life in poverty means a greater risk of poverty in later life.

Much sociological theory is directed at understanding social change. Social theorists throughout history have rarely talked about poverty as such, but nonetheless their insights into the economic ordering and structure of society offer valuable ideas for understanding poverty. Marx and Engels, writing in Victorian Britain, pointed to the stark divide between the impoverished working classes who had nothing to sell but their labour and the capitalist classes who, by virtue of owning the means of production, were able to exploit this labour to their profit.

Sociologist Max Weber, writing around the turn of the 20th century, pointed to the importance not just of economic factors in producing and sustaining inequality, but also the influence of power, status and prestige in perpetuating dominant relations. Emile Durkheim, on the other hand, emphasised the functional necessity of social inequality for the well-being of society. Echoes of these early theoretical ideas can be seen in sociological thinking, to a greater or lesser degree, right up to the present day.

This review analysed sociological theories and concepts on the causes of poverty, focusing on how to understand poverty from a sociological perspective.

Poverty and the ‘undeserving poor’

Much sociological thinking on poverty, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, has revolved around the relative importance of social structures and individual agency in explaining the prevalence and perpetuation of poverty over time. The social and political propensity to mark out some people as being somehow responsible for their own hardship has a long history. In many accounts, particularly popular and political ones but also some academic studies, the emphasis has been on the supposedly ‘undeserving poor’, citing individual behaviours, supposed fecklessness or moral failings as key causes of poverty.

More recently, it has been argued that the welfare system is responsible for encouraging and supporting claimants into welfare dependency. Further recent variations of these ideas point to ‘cultures of worklessness’, ‘troubled families’ or families who have never worked as key explanations for poverty. Sociologists have been keen to use empirical evidence to challenge these dominant, individual and often psychological explanations for poverty. They point to the importance of the broader context and the kinds of opportunities open to people as being more important than individual behaviours and choices in explaining and understanding poverty.

The close association made between poverty and individual behaviours means that it can sometimes be difficult to disentangle poverty from related issues such as unemployment or receipt of welfare. This is especially the case in some current popular and political discourse, which ignores the fact that not all unemployed people are poor and nor are all of those experiencing poverty out of work. The tendency to conflate poverty with other social issues such as unemployment, welfare receipt or substance abuse, or to uncritically cite these conditions as explanations of poverty, is tied up with the tendency to portray poverty as a problem created by those experiencing it. It is also indicative of a more general tendency to downplay the significance of poverty altogether.

The ‘cultural turn’, consumption and social class

Sociologists use the concept of social class extensively in their research, and most agree that social class has an economic base. In recent years, some have argued that social class distinctions have become more complex and fuzzy and less significant for lifestyles and life experiences. It has been suggested that opportunities for identity formation have opened up and become more reflective of individual choice than they were in the past. It is argued that individuals now have greater control over their own destinies. Consumption practices (what people buy and consume) are often cited as a key mechanism by which people can demonstrate their individuality and create their own individual identities.

Consumption, however, has also become an increasingly important element of distinction and stratification. Those experiencing poverty often find it difficult to partake in expected consumption behaviours. Furthermore, wider society often subjects the spending habits and patterns of those in the greatest poverty to stigmatisation.

So, while access to consumption might seem to open up opportunities for people to construct their lifestyles and identities in ways reflecting their own individual preferences and choices, it can also reinforce and support social class divisions and distinctions. Furthermore, social class positioning continues to be an important influence on many, if not all, aspects of people’s lives, including educational attainment, jobs and leisure activities.

Poverty, stigma and shame

Poverty and material deprivation are important drivers of stigma and shame. The depiction of those in poverty as ‘the other’ often occurs through the use of particular language, labels and images about what it means to be in poverty. These processes take place at different levels and in different sections of society. Those working in welfare sectors, for example, might negatively – and mostly mistakenly – point to individual character traits and behaviour when explaining the key reasons for unemployment. This is a process of negatively stereotyping those who are disadvantaged. While these labels are often applied from the top down, towards those experiencing poverty by those who are not, people in poverty can also buy into and perpetuate such stereotypes and stigmatisation. This is the consequence of the pressure those in poverty face to disassociate themselves from the stigma and shame associated with poverty.

Capitalism and the changing labour market

For a long time, successive governments have lauded work as the best route out of poverty. Yet the changing face of the labour market and work itself means that employment is no longer a guaranteed passport away from poverty, if indeed it ever was. In the current context, working conditions for many have worsened, public sector jobs have rapidly declined, unemployment and underemployment have been increasing, and low-paid and part-time work have proliferated. Low-paid work, or ‘poor work’ as it is sometimes referred to, is now an integral and growing aspect of the contemporary labour market. It is a particular problem for those countries which have followed an economy based on aggressive free-market principles. As a result, in-work poverty is an increasingly important explanation for contemporary poverty.

Sociology provides a powerful tool for thinking about poverty. ‘Thinking sociologically’ can help us to better comprehend social issues and problems. It allows us to understand personal troubles as part of the economic and political institutions of society, and permits us to cast a critical eye over issues that may otherwise be interpreted simplistically or misinterpreted. In looking at poverty, myths and misconceptions dominate both popular and political discussions. Sociological thinking can be helpful in trying to disentangle poverty from a range of related concepts and largely pejorative discussions about a variety of social problems.

Some attention has recently been devoted to the discussion of rising inequality. In the current context, economic inequality is getting more extreme, with those at the very top growing ever richer while the majority are finding life increasingly harsh and poverty rates are increasing. Much of the sociological evidence reviewed in this study has been concerned with the reproduction of (social class) inequalities over time. Research has shown that the majority of the British public accept that wealth can buy opportunities, but conversely most also believe in the notion of a meritocracy and that hard work is the best way to get on in life. Yet evidence shows that true equality of opportunity simply does not exist.

Using a framework of inequality (and equality) allows scope to think more closely about issues of class perpetuation and their relationship with poverty. It is not happenchance that countries with low rates of relative income poverty tend to have a strong focus on equality. Sociological theory can alert people to how a growing emphasis on individual responsibility and behaviour might make class inequality and the importance of opportunity structures less obvious. Despite this, it remains the case that where people start out in life continues to have a significant influence on where they are likely to end up. Starting out life in poverty means a greater risk of poverty later on in life.

About the project

This review analysed sociological theories and concepts on the causes of poverty and ways to understand poverty from a sociological perspective. The review was necessarily only partial, as the size of the field under consideration did not allow for a systematic review of all relevant literature. Hence, the review concentrated on what the authors deemed to be the most relevant debates for understanding poverty sociologically.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.3 Explaining Poverty

Learning objectives.

- Describe the assumptions of the functionalist and conflict views of stratification and of poverty.

- Explain the focus of symbolic interactionist work on poverty.

- Understand the difference between the individualist and structural explanations of poverty.

Why does poverty exist, and why and how do poor people end up being poor? The sociological perspectives introduced in Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems” provide some possible answers to these questions through their attempt to explain why American society is stratified —that is, why it has a range of wealth ranging from the extremely wealthy to the extremely poor. We review what these perspectives say generally about social stratification (rankings of people based on wealth and other resources a society values) before turning to explanations focusing specifically on poverty.

In general, the functionalist perspective and conflict perspective both try to explain why social stratification exists and endures, while the symbolic interactionist perspective discusses the differences that stratification produces for everyday interaction. Table 2.2 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes these three approaches.

Table 2.2 Theory Snapshot

The Functionalist View

As discussed in Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems” , functionalist theory assumes that society’s structures and processes exist because they serve important functions for society’s stability and continuity. In line with this view, functionalist theorists in sociology assume that stratification exists because it also serves important functions for society. This explanation was developed more than sixty years ago by Kingsley Davis and Wilbert Moore (Davis & Moore, 1945) in the form of several logical assumptions that imply stratification is both necessary and inevitable. When applied to American society, their assumptions would be as follows:

- Some jobs are more important than other jobs. For example, the job of a brain surgeon is more important than the job of shoe shining.

- Some jobs require more skills and knowledge than other jobs. To stay with our example, it takes more skills and knowledge to perform brain surgery than to shine shoes.

- Relatively few people have the ability to acquire the skills and knowledge that are needed to do these important, highly skilled jobs. Most of us would be able to do a decent job of shining shoes, but very few of us would be able to become brain surgeons.

- To encourage the people with the skills and knowledge to do the important, highly skilled jobs, society must promise them higher incomes or other rewards. If this is true, some people automatically end up higher in society’s ranking system than others, and stratification is thus necessary and inevitable.

To illustrate their assumptions, say we have a society where shining shoes and doing brain surgery both give us incomes of $150,000 per year. (This example is very hypothetical, but please keep reading.) If you decide to shine shoes, you can begin making this money at age 16, but if you decide to become a brain surgeon, you will not start making this same amount until about age 35, as you must first go to college and medical school and then acquire several more years of medical training. While you have spent nineteen additional years beyond age 16 getting this education and training and taking out tens of thousands of dollars in student loans, you could have spent those years shining shoes and making $150,000 a year, or $2.85 million overall. Which job would you choose?

Functional theory argues that the promise of very high incomes is necessary to encourage talented people to pursue important careers such as surgery. If physicians and shoe shiners made the same high income, would enough people decide to become physicians?

Public Domain Images – CC0 public domain.

As this example suggests, many people might not choose to become brain surgeons unless considerable financial and other rewards awaited them. By extension, we might not have enough people filling society’s important jobs unless they know they will be similarly rewarded. If this is true, we must have stratification. And if we must have stratification, then that means some people will have much less money than other people. If stratification is inevitable, then, poverty is also inevitable. The functionalist view further implies that if people are poor, it is because they do not have the ability to acquire the skills and knowledge necessary for the important, high-paying jobs.

The functionalist view sounds very logical, but a few years after Davis and Moore published their theory, other sociologists pointed out some serious problems in their argument (Tumin, 1953; Wrong, 1959).

First, it is difficult to compare the importance of many types of jobs. For example, which is more important, doing brain surgery or mining coal? Although you might be tempted to answer with brain surgery, if no coal were mined then much of our society could not function. In another example, which job is more important, attorney or professor? (Be careful how you answer this one!)

Second, the functionalist explanation implies that the most important jobs have the highest incomes and the least important jobs the lowest incomes, but many examples, including the ones just mentioned, counter this view. Coal miners make much less money than physicians, and professors, for better or worse, earn much less on the average than lawyers. A professional athlete making millions of dollars a year earns many times the income of the president of the United States, but who is more important to the nation? Elementary school teachers do a very important job in our society, but their salaries are much lower than those of sports agents, advertising executives, and many other people whose jobs are far less essential.

Third, the functionalist view assumes that people move up the economic ladder based on their abilities, skills, knowledge, and, more generally, their merit. This implies that if they do not move up the ladder, they lack the necessary merit. However, this view ignores the fact that much of our stratification stems from lack of equal opportunity. As later chapters in this book discuss, because of their race, ethnicity, gender, and class standing at birth, some people have less opportunity than others to acquire the skills and training they need to fill the types of jobs addressed by the functionalist approach.

Finally, the functionalist explanation might make sense up to a point, but it does not justify the extremes of wealth and poverty found in the United States and other nations. Even if we do have to promise higher incomes to get enough people to become physicians, does that mean we also need the amount of poverty we have? Do CEOs of corporations really need to make millions of dollars per year to get enough qualified people to become CEOs? Do people take on a position as CEO or other high-paying job at least partly because of the challenge, working conditions, and other positive aspects they offer? The functionalist view does not answer these questions adequately.

One other line of functionalist thinking focuses more directly on poverty than generally on stratification. This particular functionalist view provocatively argues that poverty exists because it serves certain positive functions for our society. These functions include the following: (1) poor people do the work that other people do not want to do; (2) the programs that help poor people provide a lot of jobs for the people employed by the programs; (3) the poor purchase goods, such as day-old bread and used clothing, that other people do not wish to purchase, and thus extend the economic value of these goods; and (4) the poor provide jobs for doctors, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals who may not be competent enough to be employed in positions catering to wealthier patients, clients, students, and so forth (Gans, 1972). Because poverty serves all these functions and more, according to this argument, the middle and upper classes have a vested interested in neglecting poverty to help ensure its continued existence.

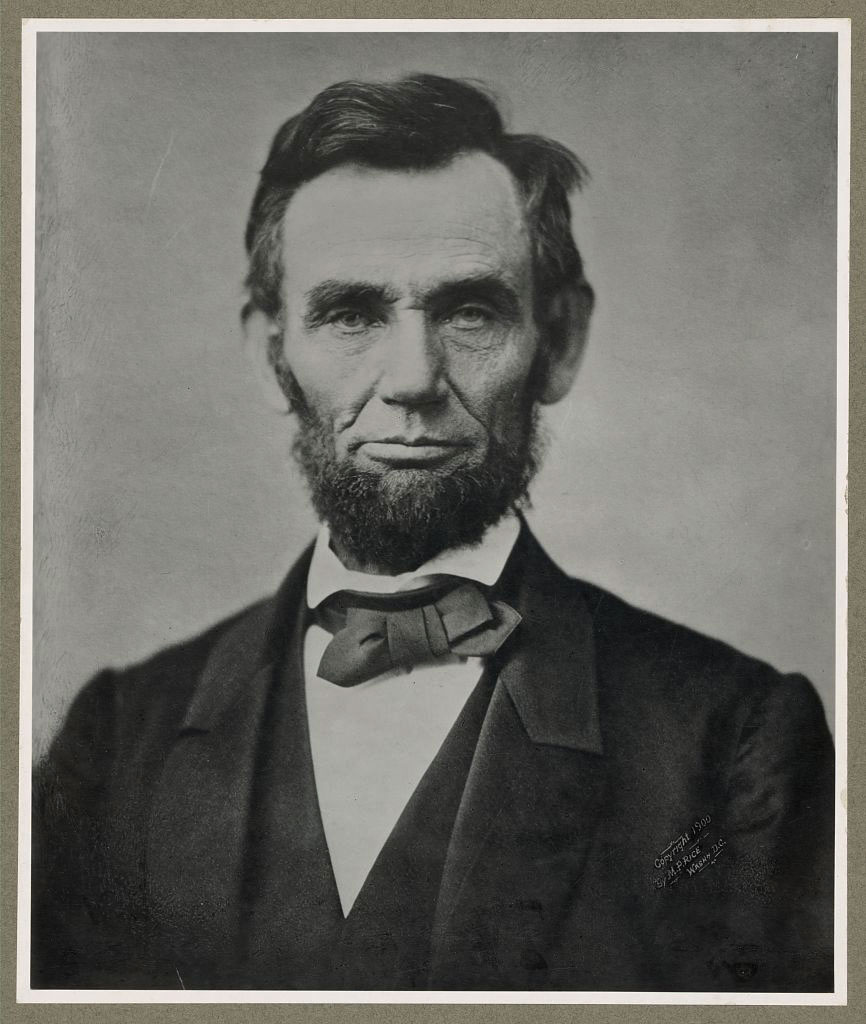

The Conflict View

Because he was born in a log cabin and later became president, Abraham Lincoln’s life epitomizes the American Dream, which is the belief that people born into poverty can become successful through hard work. The popularity of this belief leads many Americans to blame poor people for their poverty.

US Library of Congress – public domain.

Conflict theory’s explanation of stratification draws on Karl Marx’s view of class societies and incorporates the critique of the functionalist view just discussed. Many different explanations grounded in conflict theory exist, but they all assume that stratification stems from a fundamental conflict between the needs and interests of the powerful, or “haves,” in society and those of the weak, or “have-nots” (Kerbo, 2012). The former take advantage of their position at the top of society to stay at the top, even if it means oppressing those at the bottom. At a minimum, they can heavily influence the law, the media, and other institutions in a way that maintains society’s class structure.

In general, conflict theory attributes stratification and thus poverty to lack of opportunity from discrimination and prejudice against the poor, women, and people of color. In this regard, it reflects one of the early critiques of the functionalist view that the previous section outlined. To reiterate an earlier point, several of the remaining chapters of this book discuss the various obstacles that make it difficult for the poor, women, and people of color in the United States to move up the socioeconomic ladder and to otherwise enjoy healthy and productive lives.

Symbolic Interactionism

Consistent with its micro orientation, symbolic interactionism tries to understand stratification and thus poverty by looking at people’s interaction and understandings in their daily lives. Unlike the functionalist and conflict views, it does not try to explain why we have stratification in the first place. Rather, it examines the differences that stratification makes for people’s lifestyles and their interaction with other people.

Many detailed, insightful sociological books on the lives of the urban and rural poor reflect the symbolic interactionist perspective (Anderson, 1999; C. M. Duncan, 2000; Liebow, 1993; Rank, 1994). These books focus on different people in different places, but they all make very clear that the poor often lead lives of quiet desperation and must find ways of coping with the fact of being poor. In these books, the consequences of poverty discussed later in this chapter acquire a human face, and readers learn in great detail what it is like to live in poverty on a daily basis.

Some classic journalistic accounts by authors not trained in the social sciences also present eloquent descriptions of poor people’s lives (Bagdikian, 1964; Harrington, 1962). Writing in this tradition, a newspaper columnist who grew up in poverty recently recalled, “I know the feel of thick calluses on the bottom of shoeless feet. I know the bite of the cold breeze that slithers through a drafty house. I know the weight of constant worry over not having enough to fill a belly or fight an illness…Poverty is brutal, consuming and unforgiving. It strikes at the soul” (Blow, 2011).

Sociological accounts of the poor provide a vivid portrait of what it is like to live in poverty on a daily basis.

Pixabay – CC0 public domain.

On a more lighthearted note, examples of the symbolic interactionist framework are also seen in the many literary works and films that portray the difficulties that the rich and poor have in interacting on the relatively few occasions when they do interact. For example, in the film Pretty Woman , Richard Gere plays a rich businessman who hires a prostitute, played by Julia Roberts, to accompany him to swank parties and other affairs. Roberts has to buy a new wardrobe and learn how to dine and behave in these social settings, and much of the film’s humor and poignancy come from her awkwardness in learning the lifestyle of the rich.

Specific Explanations of Poverty

The functionalist and conflict views focus broadly on social stratification but only indirectly on poverty. When poverty finally attracted national attention during the 1960s, scholars began to try specifically to understand why poor people become poor and remain poor. Two competing explanations developed, with the basic debate turning on whether poverty arises from problems either within the poor themselves or in the society in which they live (Rank, 2011). The first type of explanation follows logically from the functional theory of stratification and may be considered an individualistic explanation. The second type of explanation follows from conflict theory and is a structural explanation that focuses on problems in American society that produce poverty. Table 2.3 “Explanations of Poverty” summarizes these explanations.

Table 2.3 Explanations of Poverty

It is critical to determine which explanation makes more sense because, as sociologist Theresa C. Davidson (Davidson, 2009) observes, “beliefs about the causes of poverty shape attitudes toward the poor.” To be more precise, the particular explanation that people favor affects their view of government efforts to help the poor. Those who attribute poverty to problems in the larger society are much more likely than those who attribute it to deficiencies among the poor to believe that the government should do more to help the poor (Bradley & Cole, 2002). The explanation for poverty we favor presumably affects the amount of sympathy we have for the poor, and our sympathy, or lack of sympathy, in turn affects our views about the government’s role in helping the poor. With this backdrop in mind, what do the individualistic and structural explanations of poverty say?

Individualistic Explanation

According to the individualistic explanation , the poor have personal problems and deficiencies that are responsible for their poverty. In the past, the poor were thought to be biologically inferior, a view that has not entirely faded, but today the much more common belief is that they lack the ambition and motivation to work hard and to achieve success. According to survey evidence, the majority of Americans share this belief (Davidson, 2009). A more sophisticated version of this type of explanation is called the culture of poverty theory (Banfield, 1974; Lewis, 1966; Murray, 2012). According to this theory, the poor generally have beliefs and values that differ from those of the nonpoor and that doom them to continued poverty. For example, they are said to be impulsive and to live for the present rather than the future.

Regardless of which version one might hold, the individualistic explanation is a blaming-the-victim approach (see Chapter 1 “Understanding Social Problems” ). Critics say this explanation ignores discrimination and other problems in American society and exaggerates the degree to which the poor and nonpoor do in fact hold different values (Ehrenreich, 2012; Holland, 2011; Schmidt, 2012). Regarding the latter point, they note that poor employed adults work more hours per week than wealthier adults and that poor parents interviewed in surveys value education for their children at least as much as wealthier parents. These and other similarities in values and beliefs lead critics of the individualistic explanation to conclude that poor people’s poverty cannot reasonably be said to result from a culture of poverty.

Structural Explanation

According to the second, structural explanation , which is a blaming-the-system approach, US poverty stems from problems in American society that lead to a lack of equal opportunity and a lack of jobs. These problems include (a) racial, ethnic, gender, and age discrimination; (b) lack of good schooling and adequate health care; and (c) structural changes in the American economic system, such as the departure of manufacturing companies from American cities in the 1980s and 1990s that led to the loss of thousands of jobs. These problems help create a vicious cycle of poverty in which children of the poor are often fated to end up in poverty or near poverty themselves as adults.

As Rank (Rank, 2011) summarizes this view, “American poverty is largely the result of failings at the economic and political levels, rather than at the individual level…In contrast to [the individualistic] perspective, the basic problem lies in a shortage of viable opportunities for all Americans.” Rank points out that the US economy during the past few decades has created more low-paying and part-time jobs and jobs without benefits, meaning that Americans increasingly find themselves in jobs that barely lift them out of poverty, if at all. Sociologist Fred Block and colleagues share this critique of the individualistic perspective: “Most of our policies incorrectly assume that people can avoid or overcome poverty through hard work alone. Yet this assumption ignores the realities of our failing urban schools, increasing employment insecurities, and the lack of affordable housing, health care, and child care. It ignores the fact that the American Dream is rapidly becoming unattainable for an increasing number of Americans, whether employed or not” (Block, et. al., 2006).

Most sociologists favor the structural explanation. As later chapters in this book document, racial and ethnic discrimination, lack of adequate schooling and health care, and other problems make it difficult to rise out of poverty. On the other hand, some ethnographic research supports the individualistic explanation by showing that the poor do have certain values and follow certain practices that augment their plight (Small, et. al., 2010). For example, the poor have higher rates of cigarette smoking (34 percent of people with annual incomes between $6,000 and $11,999 smoke, compared to only 13 percent of those with incomes $90,000 or greater [Goszkowski, 2008]), which helps cause them to have more serious health problems.

Adopting an integrated perspective, some researchers say these values and practices are ultimately the result of poverty itself (Small et, al., 2010). These scholars concede a culture of poverty does exist, but they also say it exists because it helps the poor cope daily with the structural effects of being poor. If these effects lead to a culture of poverty, they add, poverty then becomes self-perpetuating. If poverty is both cultural and structural in origin, these scholars say, efforts to improve the lives of people in the “other America” must involve increased structural opportunities for the poor and changes in some of their values and practices.

Key Takeaways

- According to the functionalist view, stratification is a necessary and inevitable consequence of the need to use the promise of financial reward to encourage talented people to pursue important jobs and careers.

- According to conflict theory, stratification results from lack of opportunity and discrimination against the poor and people of color.

- According to symbolic interactionism, social class affects how people interact in everyday life and how they view certain aspects of the social world .

- The individualistic view attributes poverty to individual failings of poor people themselves, while the structural view attributes poverty to problems in the larger society.

For Your Review

- In explaining poverty in the United States, which view, individualist or structural, makes more sense to you? Why?

- Suppose you could wave a magic wand and invent a society where everyone had about the same income no matter which job he or she performed. Do you think it would be difficult to persuade enough people to become physicians or to pursue other important careers? Explain your answer.

Anderson, E. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Bagdikian, B. H. (1964). In the midst of plenty: The poor in America . Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Banfield, E. C. (1974). The unheavenly city revisited . Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Block, F., Korteweg, A. C., & Woodward, K. (2006). The compassion gap in American poverty policy. Contexts, 5 (2), 14–20.

Blow, C. M. (2011, June 25). Them that’s not shall lose. New York Times , p. A19.

Bradley, C., & Cole, D. J. (2002). Causal attributions and the significance of self-efficacy in predicting solutions to poverty. Sociological Focus, 35 , 381–396.

Davidson, T. C. (2009). Attributions for poverty among college students: The impact of service-learning and religiosity. College Student Journal, 43 , 136–144.

Davis, K., & Moore, W. (1945). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10 , 242–249.

Duncan, C. M. (2000). Worlds apart: Why poverty persists in rural America . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ehrenreich, B. (2012, March 15). What “other America”? Salon.com . Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2012/03/15/the_truth_about_the_poor/ .

Gans, H. J. (1972). The positive functions of poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 78 , 275–289.

Goszkowski, R. (2008). Among Americans, smoking decreases as income increases. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/105550/among-americans-smoking-decreases-income-increases.aspx .

Harrington, M. (1962). The other America: Poverty in the United States . New York, NY: Macmillan.

Holland, J. (2011, July 29). Debunking the big lie right-wingers use to justify black poverty and unemployment. AlterNet . Retrieved from http://www.alternet.org/story/151830/debunking_the_big_lie_right-wingers_use_to_justify_black_poverty _and_unemployment_?page=entire .

Kerbo, H. R. (2012). Social stratification and inequality . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Lewis, O. (1966). The culture of poverty. Scientific American, 113 , 19–25.

Liebow, E. (1993). Tell them who I am: The lives of homeless women . New York, NY: Free Press.

Murray, C. (2012). Coming apart: The state of white America, 1960–2010 . New York, NY: Crown Forum.

Rank, M. R. (1994). Living on the edge: The realities of welfare in America . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Rank, M. R. (2011). Rethinking American poverty. Contexts, 10 (Spring), 16–21.

Schmidt, P. (2012, February 12). Charles Murray, author of the “Bell Curve,” steps back into the ring. The Chronicle of Higher Education . Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Charles-Murray-Author-of-The/130722/?sid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en .

Small, M. L., Harding, D. J., & Lamont, M. (2010). Reconsidering culture and poverty. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 629 (May), 6–27.

Tumin, M. M. (1953). Some principles of stratification: A critical analysis. American Sociological Review, 18 , 387–393.

Wrong, D. H. (1959). The functional theory of stratification: Some neglected considerations. American Sociological Review, 24 , 772–782.

Social Problems Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Sociological Perspectives on Poverty

Related Papers

Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

Patricia Gurin

The European journal of development …

Federica Misturelli , Claire Heffernan

Robert Lake

A boundless optimism leaps from every page of this book. It is a book of audacious ambition, unrestrained passion, unbridled hope, and unstinting ethical commitment. Fueling this optimism is an inextinguishable conviction that poverty theory illuminates a discernable path from our present circumstances to an auspicious future and that an implicit link connects knowledge of poverty to knowledge for its elimination. The ultimate contribution of Territories of Poverty may rest on how well the editors and contributors are justified in these beliefs. Editors Ananya Roy and Emma Shaw Crane state unequivocally in their Preface that " this project is unapologetically concerned with theory. " The editors fully endorse the Enlightenment precept that knowledge is power. They are confident in their wager that theorizing poverty in the right way, correcting the false starts and misguided theories that litter the history of poverty knowledge, will finally prepare the ground for its elimination. That belief rests on two presumptions. First is the certainty that poverty is knowable, is available to the knower, and is willing to let itself be known—not only seen but known in its ontological essence. Second is the wager that poverty knowledge is the avenue to progress, and that better knowledge constitutes a political tactic that can be marshaled to make a world without poverty. The chapters that follow the editors' preface and introduction, however, challenge such optimism in a series of astute analyses of existing poverty policy. With unerring insight and incisive analysis, the authors narrate an unbroken record in which policy ostensibly claiming to reduce or eliminate poverty instead exacerbated or redistributed the problem and found new ways to subject its intended beneficiaries to new forms of indignity, degradation and further immiseration. The collective lessons of these penetrating analyses are twofold: first, that regardless of its particular form or focus, poverty policy consistently accommodates the changing requirements of a social, political and economic order that repeatedly reinvents itself; and, second, that a discourse of poverty alleviation legitimates programs and actions that align with the changing requirements of that structural and procedural reinvention. It is unclear, as a result, how these incisive analyses of poverty policy contribute to the book's optimistic premise. A theory of poverty is not a theory of the absence of poverty and an analytic theory is not a theory of change. Calling out the failures of existing policy is not the same as calling for an alternative solution, and critique of current policy does not in itself reveal a route to a different future. Despite the Enlightenment belief that knowledge is power, how to use that knowledge moving forward still remains to be explained before collecting on the wager that theory opens the path to a better future. Further challenging the book's optimistic premise is the possibility that better knowledge may reveal that poverty is impermeable to solution, an intractable element of the human condition. The editors and contributors adopt a broadly relational approach to theorizing poverty, an approach that I strongly endorse for its ability to probe beyond reductive

Jan Vranken

Claire Heffernan , Federica Misturelli

Open Journal of Social Sciences

Neil Bechervaise

Ethische Perspectieven

Luís Capucha

Stephen D'Arcy

Educational Leadership

Paul Gorski

Loek Halman

RELATED PAPERS

Aryanti Alfi

Christine Butts

The Iowa Review

Don Colburn

Studia Iuridica Lublinensia

Jarosław Kostrubiec

Journal of Thermal Analysis

Ahmed Ibrahim

Enfermería Global

Christefany Régia Braz Costa

David Leong

Alberto Souto

Ciência da Informação em Revista

Edivanio Duarte de Souza

Ethnolinguistics. Problems of Language and Culture

Diseases of the Colon & Rectum

Rene Hartmann

Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications

Frank B Williamson

Elio Phillo , Yoga Sahria

Revista latinoamericana de educación inclusiva

Jorge Carcamo

American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology

chandira kumar

Applied Energy

Stephen Ogaji

Sandra Maria Corso Orams

Academic Perspective Procedia

Turgay Beyaz

Knowledgeable Research: A Multidisciplinary Journal

Shradha Sarswat

Slovenská literatúra

Hana Lacova

International Journal of Thermophysics

laurent pitre

Fundamentos filosóficos del taekwondo

manuel repol

Current Science

Subbiah Arunachalam

Wieslawa Miemiec

Hiandra Munique S Costa

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Future of European Welfare pp 41–62 Cite as

Poverty and Social Exclusion: A Sociological View

- Serge Paugam

130 Accesses

10 Citations

The sociological literature on both poverty and social exclusion is large and varied, and the abundance of references means that providing a review is an arduous task. It becomes even more difficult when trying to compare different nations or cultures. Thus, there is no question of providing an exhaustive study of recent, past and ongoing research; however, it is more realistic to establish the complex linkage between this research, and social and political debate. The main problem for scholars in this field is constructing a research question which, whilst being distinct from contemporary ways of thinking which characterize the social debate (science must distance itself from the subject matter in order to build a conceptual framework) can also stimulate debate. Sociologists will favour studying what appears dysfunctional or anomalous in the social system at any given moment. They must, therefore, partially base their work in social debate. But the science which they aim to develop cannot simply be social criticism or, conversely, an ideological justification of existing norms.

Translated by Jocelyn Evans

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Abrahamson, P. (1994) ‘La pauvreté en Scandinavie’, in F.-X. Merrien (ed.), Face à la pauvreté. L’Occident et les pauvres hier et aujourd’hui , Paris: Les Editions de l’Atelier, pp. 171–88.

Google Scholar

Aron, R. (1969) Les désillusions du progrès. Essai sur la dialectique du progrès , Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

Aguilar, M. et al. (1995) La caña y el pez. Estudio sobre los Salarios Sociales en las Comunidades Autonomas , Madrid: Fundación Foessa.

Barclay, P. (1995) Joseph Rowntree Foundation Inquiry into Income and Wealth , York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Castel, R. (1995) Les métamorphoses de la question sociale. Une chronique du salariat , Paris: Fayard.

European Economic Community (1990) La perception de la pauvreté en Europe en 1989 , Bruxelles, Eurobaromètre.

Commisione di indagine sulla povertà (1994) La povertà in Italia nel 1993 , Roma, documento reso publico il 14 luglio 1994.

Eurostat (1990) La pauvreté en chiffres: l’Europe au début des années 80 , Luxembourg.

Evans, M., Paugam, S. and Prelis, J.A. (1995) Chunnel Vision: Poverty, Social Exclusion and The Debate on Social Security in France and Britain , London School of Economics, STICERD, Welfare State Programme/115.

Gallie, D., Marsh, C. and Vogler, C. (eds.) (1994) Social Change and the Experience of Unemployment , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hauser, R. (1993) Arme unter uns Teil 1, Ergebnisse und Konsequenzen der Caritas-Armutsuntersuchung , Caritas.

d’Iiribarne, P. (1990) Le chômage paradoxal , Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Jaurez, M. (ed.) (1994) Informe sociologico sobre la situacion social en España , Madrid: Fundación Foessa (see especially pp. 315-34).

Mendras, H. (1976) Sociétés paysannes. Eléments pour une théorie de la paysannerie , Paris, Armand Colin, revised Folio edition, 1995.

Merrien, F-X. (1994) ‘Divergences franco-britanniques’, in F-X. Merrien (ed.), Face à la pauvreté. L’Occident et les pauvres hier et aujourd’hui , Paris: Les Editions de l’Atelier, pp. 99–135.

Morris, L. (1995) Social Divisions, Economic Decline and Social Structural Change , London: UCL Press.

Paugam, S. (1991) La disqualification sociale. Essai sur la nouvelle pauvreté , Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (3rd revised and augmented edition, 1994).

Paugam, S. (1993) La société française et les pauvres , Paris: Presses Universitaires de France (2nd edition, 1995).

Paugam, S. (ed.) (1996) L’exclusion, l’état des savoirs , Paris: La Découverte, Coll. ‘Textes à l’appui’.

Paugam, S., Prelis, J.A. and Zoyem, J-P. (1994) Appréhension de la pauvreté sous l’angle de la disqualification sociale , Rapport du CERC, Eurostat: Commission des Communautés Européennes, 1994.

Paugam, S., Zoygem, J-P. and Charbonnel, J-M. (1993) Précarité et risque d’exclusion en France , Paris: La Documentation Française, Coll. ‘Documents du CERC’, no. 109.

Pugliese, E. (1993) Sociologia délia disoccupazione , Bologna: II Mulino (see especially Chapter 5 ‘II modello italiano délia disoccupazione’, pp. 147–89).

Simmel, G. (1908) Soziologie. Unterschungen öber die Formen der Vergesellschaftung , Leipizig, Duncker-Humboldt.

Schnapper, D. (1981) L’épreuve du chômage , Paris: Gallimard, new revised Folio edition, 1994.

Schnapper, D. (1989) ‘Rapport à l’emploi, protection sociale et status sociaux’, Revue française de Sociologie , XXX, 1, pp. 3–29.

Article Google Scholar

Schultheis, F. (1966) ‘L’Etat et la société civile face à la pauvreté en Allemagne’, in S. Paugam (ed.), L’exclusion, l’état des savoirs , Paris, La Découverte, Coll. ‘Textes à l’appui’.

Sgritta, G. and Innocenzi G. (1993) ‘La povertà’, in M. Paci (ed.), Le dimensioni della disuguaglianza. Rapporto della Fondazione Cespe sulla disuguaglianza sociale in Italia , Bologna, Società éditrice il Mulino, pp. 261–92.

Wacquant, L. (1992) ‘Banlieues françaises et ghetto noir américain: de l’amalgame à la comparaison’, French Politics and Society , 10, 4.

Xiberras, M. (1994) Les théories de l’exclusion. Pour une construction de l’imaginaire de la déviance , Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck (preface by Julien Freund).

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Robert Schuman Centre, European University Institute, Florence, Italy

Martin Rhodes ( Senior Research Fellow ) & Yves Mény ( Professor, Director ) ( Senior Research Fellow ) & ( Professor, Director )

Institut d’ Etudes Politiques, Paris, France

Yves Mény ( Professor, Director ) ( Professor, Director )

Copyright information

© 1998 Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Paugam, S. (1998). Poverty and Social Exclusion: A Sociological View. In: Rhodes, M., Mény, Y. (eds) The Future of European Welfare. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26543-5_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26543-5_3

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-26545-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-26543-5

eBook Packages : Palgrave Political & Intern. Studies Collection Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective Autobiography Essay

Personal explanation, sociological imagination, data/statistics.

Psychology helps people understand their self-esteem, politics entails governance and polling matters, while biology relates to life issues. However, sociological imagination by Mills provides scope for knowing the complex social world that supersedes our ordinary imagination and experiences. Although Mills’ concept was not initially recognized, it is applied in the modern society to provide knowledge on various issues affecting the humanity. The theory forbids individuals from regarding their personal experience as their own creation but seeing the problems as those created by the society. In other words, if one individual is suffering, then there are many others undergoing the same all over the world. For instance, I have been raised in a poor family, but sociological imagination discourages me from only focusing on the negative side of poverty, but instead encourages me to take the challenge with an open mind. This essay will apply C. W. Mills’ sociological imagination concept to explain the issue of poverty problem I have been experiencing.

I was born 26 years ago in Princeton, a small city in Missouri. Although it is small in size and population, it is rich in geographical beauty. I was raised in a nuclear family, where my mum was a housewife, and my father worked in a local hog farm as the overall manager. Although I considered myself lucky, since I had both my parents living together in an environment where single parents raise most children, life could not be considered easy. Poverty was the norm of the day since my dad was only paid a small amount of money, yet he had four of us to support. He was always overwhelmed, and at some point in life, he had to seek a second job to increase his financial status.

My elder brother and I joined a local public school, which was considered an education center for the low-class citizens. Moreover, having Christmas gifts and birthday celebrations was a luxury. In most cases, we even forgot our birthdates because it was just a typical day. Our misfortune blossomed when my father was diagnosed with stage III stomach cancer. With my dad bedridden and unable to pay his usual bills, my brother and I had to look for an income. When my dad died on July 31, 2016, I realized what poverty meant.

Smith and I became employed as casual laborers in a small grocery store. Although the state’s law forbidden us from working, we had to labor more hours to earn a living and pay our bills. My mother still had to stay at home and take care of our two young sisters. Despite the challenges, we remained focused and continued with our education. We knew that only academic excellence could raise our financial status and attained high grades throughout our high school terms. As a result, my brother joined a prestigious university in the country, and he is set to graduate this year as a doctor. I am also lucky to be enrolled in one of the good colleges in the city.

Society classifies individuals into different categories, such as the poor, the middle class, and the wealthy. Some people might argue that some may rise to better income level from poverty, but in reality, nobody chooses their economic status. Although most individuals are able to work hard to earn more, it is impossible to choose whether to be poor or rich. It is the society which determines a persons’ present and future financial status.

Sociological imagination helps the public to distinguish the social levels from personal circumstances. Once an individual is able to differentiate the two, the or she can make personal decisions which can serve him best due to the larger social forces people face. Being that I was raised in a poor home does not mean that I will stay in poverty. Instead of focusing on looking for money, I changed my perception and decided to put all my effort into education. Although schooling was not instantly paying, it was a long-term investment that was promising in my perception. The social troubles impacted my success by helping me to find solace in studying. In other words, I became empowered to understanding what reduces poverty levels. Although social imagination is sometimes misunderstood due to providing excuses to people, every person should account for their actions.

Conflict theory best describes my initial situation by illustrating that society is full of competition, and people have to contest for the limited available resources. According to Keirns et al. (2018), the world is composed of people from different social classes who have to compete for the few available opportunities. Institutions such as education, religion, and government have to keep more resources, thus promoting unequal social structure. Individuals who obtain more resources use their influence and power to maintain their social class, while those who are allocated little possessions have to struggle to find their way to the wealthy class.

In this regard, the level of poverty that I experienced was caused by the state. The government made education expensive when my parents were still schooling. They could not afford the school fees of the good institutes, and eventually, they dropped out. As a result, they only got employed in jobs which were not well-paid. However, this motivated me to work hard to surpass the level of education my parents achieved.

Numerous people are experiencing high levels of poverty across the United States. Based on the study conducted by Dotson and Foley (2016), students who perform well in class originate from families who can cater to their needs. Besides, the black people are more exposed to poverty compared to other races. A survey performed in 2018/2019 showed that poverty levels decreased to 10.5% from the initial 11.8% witnessed in 2018 (Semega et al., 2020). Despite the previous high levels of poverty, current research shows that the gap between the poor and the rich decreases, and many people can cater to their needs.

In conclusion, poverty is a social issue that has affected many generations. Conflict theory illustrates the case as a societal problem that avails limited resources to people, giving them no option but to compete. However, there is no fairground for competition as the rich use their power and authority to manipulate the wealthy institutions to protect their interests. Concurrently, the lower class struggles to climb the social level. Sociological imagination offers hope to the less fortunate by encouraging them to understand that their situation is not their creation but a societal problem. One must not take advantage of the Mills’ concept to explain their position, but instead employ it positively to overturn their present misfortunes. Hence, poverty should not prevent a person from achieving the set goals

Dotson, L., & Foley, V. (2016). Middle grades student achievement and poverty levels: Implications for teacher preparation. Journal of Learning in Higher Education , 12 (2), 33-44.

Keirns, N., Strayer, E., Griffiths, H., Cody-Rydzewski, S., Scaramuzzo, G., Sadler, T., Vvain, s., Bry, J. & Jones, F. (2018). Introduction to sociology . OpenStax. Web.

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Shrider, E. A., & Creamer, J. (2020 ). Income and poverty in the United States: 2019 . United States Bureau. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, November 1). Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-a-sociological-imagination-perspective/

"Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective." IvyPanda , 1 Nov. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-a-sociological-imagination-perspective/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective'. 1 November.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective." November 1, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-a-sociological-imagination-perspective/.

1. IvyPanda . "Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective." November 1, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-a-sociological-imagination-perspective/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Poverty: A Sociological Imagination Perspective." November 1, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/poverty-a-sociological-imagination-perspective/.

- Rich Dad Poor Dad Essay

- Financial Education in Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki

- The Road to Financial Success: "Rich Dad Poor Dad" by Robert Kiyosaki

- Stay-At-Home Dads

- Lucky Dube as the Icon in the Reggae Music Industry

- Stay at Home Dads: Not So Bad

- I Love Lucy vs. See Dad Run

- “To Twitter or Not to Twitter”: Critique of Robert’s W. Lucky Article

- Mills' "The Sociological Imagination" Summary

- Sociological Imagination Concept

- The Impact of Poverty on Children Under the Age of 11

- Poverty Policy Recommendations

- Poverty Reduction and Natural Assets

- The Impact of Globalization Today and Polarization of the World Economy

- Finance in Huffington's Thrive and Kafka's The Metamorphosis

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Approaches to subjective poverty in economic and sociological research

- Martin Lačný

Poverty is a complex phenomenon which has been the subject of research across the social sciences. There have been varying approaches to defining and measuring poverty, especially with regard to research focus. In economic and sociological research, the concept of subjective poverty, which is particularly interesting in terms of psychological research into poverty, represents an alternative to the predominant objective measures of poverty. This article reviews the approaches to poverty used in economic and sociological research, paying special regard to representative approaches to subjective poverty, including subjective poverty lines and outlines the aspects relevant to psychological research into poverty.

Introduction

While there have been different approaches to and concepts for defining and measuring poverty, inferior living conditions and their serious individual and social consequences have remained dominant. The scale of poverty ranges from the imminent threat of starvation and increased risk of certain diseases, to the inability to participate in the services normally available to the rest of society. The economic concept of poverty deals with subsistence income levels. Several levels are taken into account: (1) the existential subsistence minimum, the lowest standard of living at which only the most basic living needs can be satisfied (extreme poverty line); (2) social subsistence minimum, reflecting ability to meet socially recognized needs (poverty line); (3) minimal comfort, society’s minimum level for a comfortable standard of living.

In the economic sciences, poverty is understood as a comparative concept based on the consensus of those who view the phenomenon of poverty from the outside. This is generally based on statistics ( Riegel, 2007 ).

In sociology, there are particular views of specific aspects of poverty. For example, Shildrick and Rucell (2015) describe a functionalist approach in which poverty is understood to be a consequence of circumstance. In other words, the poor share the general values of society but are unable to implement them because of low income, insufficient qualifications and so on. Lewis, Webley, and Furnham (1995) have discussed conflict theory which emphasizes that poverty inhibits the ability to fight for the distribution of scarce resources, while interaction theory underlines the stigma of poverty, because poverty is not only an economic deprivation but is involved in self-concept as well.

Gordon (1972) interpreted radical theories which distinguish the primary labour market (typically relative stability and high income) from the secondary labour market (unstable with low income), resulting from bad interaction between governments and trade unions. Townsend (1979) described the theory of minority groups and subculture theory . The former approach distinguishes between primary poverty (resulting from the death of the breadwinner, illness, injury) and secondary poverty (resulting from alcoholism, mismanagement, irregular income, etc.). Subculture theory identifies the common features of poorer segments of societies in different countries. These include values, interpersonal relationships, family and community structures, similar patterns of consumption and time spending and differences in economic, intellectual or emotional level compared with the majority of society.

Psychology has the ability to go deeper into the objective and subjective components of poverty. However, Džuka, Babinčák, Kačmárová, Mikulášková, and Martončik (2017) consider the initial state of psychological research into poverty to be an ‘open space’ in Slovakia. In other countries, research has only just started to reveal the psychological aspects of poverty and has not yet focused on a comprehensive understanding. They point out that, globally, the psychological research on poverty enjoys significant attention, especially that relating to the subjective causes and psychological consequences of poverty. The aim of this article is to review the representative approaches to subjective poverty and outline the aspects that are important for psychological research into poverty: first, the basic approaches to defining the variables for conceptualizing poverty (financial resources, capabilities and the multidimensional approach); second, the identification of objective and subjective poverty; and finally, third, subjective poverty lines and subjective sub-indicators used in poverty measures.

Income vs capabilities