IELTS Mock Test 2021 April

- Published on: 27 Apr 2021

- Tests taken: 767,686

Answer Keys:

Part 1: Question 1 - 12

- 7 (An) interest

- 8 Productivity

- 10 Gambling

- 11 Impulse control disorders

- 12 Psychological (root)

Part 2: Question 13 - 26

- 16 NOT GIVEN

- 20 NOT GIVEN

- 22 NOT GIVEN

- 24 Inland Taipan

- 25 Populated areas

Part 3: Question 27 - 40

- 34 Programming

- 36 Feelings

- 38 NOT GIVEN

Review your test now?

Leaderboard:

Share your score

Tips for improving your ielts score

剑桥雅思5听力原文-TEST3

19 Oct 2023

Scan below QR code to share with your friends

Review & Explanations:

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage 1 has seven paragraphs A-G.

Choose the correct heading for paragraphs B to G from the list of headings below.

Write the correct number i-x in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet.

Example : Paragraph A; Answer : viii

1 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph B 2 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph C 3 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph D 4 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph E 5 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph F 6 i ii iii iv v vi vii viii ix x Paragraph G

Questions 7-12

Answer the questions below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 7-12 on your answer sheet.

It is increasingly difficult to differentiate between an addiction and what?

What can soft addictions can lead to a decline in?

Addictions that involve consumption of a drug and have a clear connection with what?

What specific addiction has increased considerably over recent years?

In some cases, addictions should actually be labelled as what?

Extreme addictions often have what kind of root cause?

Questions 13-15

According to the information in the passage, classify the following information as relating to:

Write the correct letter, A, B or C in boxes 13-15 on your answer sheet

13 A B C are protected by secretions on their skin.

14 A B C are often colored to match the environment.

15 A B C aggressively use toxins.

Note : In order to save time, you should consider which part should be done first by taking a glance at the types of the given questions. For this passage, the questions are divided into 03 categories: classification, T/F/NG and short answers question. It is recommended to finish the T/F/NG before completing the two others.

All the relevant information to answer the questions 13-15 can be found in the second paragraph only

T/F/NG questions follow the sequence of the paragraphs

Questions 16-22

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 16-22 on your answer sheet write

16 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN There is a common misunderstanding of the difference between poisonous and venomous 17 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN Significant environmental disasters are more damaging than animals 18 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN The poison dart frog obtains its poison from its environment 19 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN Touching a puffer fish can cause paralysis 20 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN The Brazilian Wandering spider kills more people every year than any other venomous creature. 21 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN The box jellyfish can cause death by drowning 22 TRUE FALSE NOT GIVEN The tentacles on a box jellyfish are used for movement

Questions 23-26

Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

What do the people of South and Central America principally use poisoned blow darts for these days? 23

The venom of which creature can be neutralised if medical intervention is swift? 24

Where does the Brazilian Wandering spider often sleep? 25

After whom does the box jellyfish have its other name? 26

Questions 27-33

Match each statement with the correct person.

Write the correct answer A-D in boxes 27-33 on your answer sheet.

27 A B C D E A successful solution can only be found when there is a clear corporate structure for decision making. 28 A B C D E Decisions made without full consideration of the details are a potential by-product of pressure. 29 A B C D E Decision making that does not look into motives for the issue is the primary reason for continued problems. 30 A B C D E Poor decision making is the most easily identified form of weak managerial ability. 31 A B C D E Seeking a staff member on whom responsibility can be placed can have negative effects. 32 A B C D E Decision making abilities are at least partly formulated long before they have any business application. 33 A B C D E Long term solutions can only be found by asking the right questions.

Questions 34-37

Complete the flowchart below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 34 to 37 on your answer sheet.

Questions 38-40

Do the following statements agree with the views given in Reading Passage 3?

In boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet write

38 YES NO NOT GIVEN It is only in recent years that the mental processes behind decision making have been studied. 39 YES NO NOT GIVEN Garen Filke completely disagrees with the conclusion drawn by Martin Hewings. 40 YES NO NOT GIVEN John Tate believes that successful decision making is not related to psychology.

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-12 , which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

THE NATURE OF ADDICTION

A. Many people would perhaps, at least as an immediate response, not consider themselves to be ‘addicts’, yet a closer look into aspects of lifestyle and mental attitude often reveal a far different picture. The main problem at presents that the traditional definition of the word has become blurred and the lines between addiction and interest are far harder to identify. In the past, the label ‘addict’ was generally applied to those with an insatiable appetite for certain substances that were traditional known to be harmful, illegal or both: psychoactive drugs, alcohol and nicotine, for example. More recently, however, we find that a there is a multitude of potential addictions. Gambling, food, work, shopping – all of which are potential areas where addiction can lurk.

B. To try to define the subject of addiction (and in many cases the subsequent course of treatment to best combat it), psychologists now commonly referred to three distinct categories. The first is related to those forms of addictions that are perhaps not life-threatening or particularly dangerous, and are often labelled in an almost tongue-in-cheek manner , such as the consumption of chocolate possibly leading to the creation of a ‘chocoholic’. This category is referred to as soft addiction and is generally related only to a potential loss of productivity ; in the workplace, an employee who is addicted to social networking sites is likely to be a less useful member of staff.

C. Substance addiction, however, is a completely different category, and focuses ‘ on ingestion of a drug (either natural or synthetic) to temporarily alter the chemical constitution of the brain. It is a combination of physical and psychological dependency on substances that have known health dangers, and the knock-on problem that users in an addicted state will often go to great lengths to acquire these substances, hence leading to the very strong connection between drug abuse and crime .

D. Finally there is behavioural addiction, which is regarded as ‘a compulsion to engage in some specific activity, despite harmful consequences’ and is a relatively recent entrant to the field. This is where the ‘soft’ addictions taken go beyond a safe limit and can become dangerous . Overeating, especially on sweetened foods, is one of the more common behavioural addictions, potentially leading to morbid obesity and associated health risks. Also included in this grouping are concerns like excessive gambling, and for many the combination of the availability and anonymity of the internet, as well as a plethora of online gambling sites, has led to a vast increase in this form of addiction.

E. However, the point at which a soft addiction becomes a behavioural addiction is both hard to define and cause for significant controversy . A child who comes home after school and plays on the internet for three hours is considered by some to be suffering from a behavioural addiction; to others, this is just a modern form of leisure time and just as valid as reading a book or playing outside. Another point of friction among people involved in studying and treating sufferers is that some of the issues covered by the umbrella term ‘addiction’ are actually mislabelled, and they belong more to a different category altogether and should be referred to as ‘ Impulse control disorders ’.

F. The correct course of action when attempting to overcome an addiction varies greatly between the type of addiction it is, but also varies considerably among the medical community. Take substance addiction, for example. The traditional approach has been to remove the source – that is, remove the availability of the drug – but this is now no longer concerned the best long term approach. The old idea of incarcerating the addict away from any drugs proved faulty as this did not prevent relapses when back in society. There is now an increasing tendency to consider not only the mechanical nature of addiction, but the psychological source . Often, extreme addictions – both substance based and behavioural – stem front a psychological root such as stress, guilt, depression and rejection, and it is for this reason that counselling and open discussion are having more successful long-term results.

G. For non-professionals with people in their lives who are suffering from some form of addiction, the importance now is in focussing on supporting their recovery, not enabling their dependence. Judgemental attitudes or helping to conceal addiction have been shown not only to perpetuate the problem, but in many cases actually exacerbate it.

--------------------

Great thanks to volunteer Trương Nhật Minh who has contributed these explanations and markings.

If you want to make a better world like this, please contact us.

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 13-26 which are based on Beading Passage 2 below.

POISONOUS ANIMALS

- Often benign and beautiful, there are so many potential dangers, often lethal, hidden in the natural world that our continued existence on the planet is actually quite astounding. Earthquakes, tsunami and volcanoes are some of natures more cataclysmic risks, but fade in comparison to the dangers presented by the more aggressive flora and fauna around the world .

- There are two classes of creature that use chemicals in either attack or defence, but it is important to draw a distinction between those that are considered poisonous and those that are venomous. A poisonous creature is one that has a chemical component to dissuade potential predators; they usually secrete toxins through their skin so that their attacker is poisoned. A venomous creature, on the other hand, is not so passive – they use toxins not in defence but in attack . This differentiation is often seen in the colouring of the creatures in question – those with poisonous toxins are often brightly coloured as a warning to potential predators, whereas those classed as venomous are often camouflaged to blend in with their surroundings , making them more efficient hunters.

- One of the most poisonous animals know to man is the poison arrow frog, native to Central and South America. Secreting poison through its skin, a single touch is enough to kill a fully grown human (in fact, the frog earned its name from the practice of putting tiny amounts of this poison onto blow darts used by the native population mainly for hunting and, historically at least, also for battle). It is interesting to note, however, that when bred in captivity, the dart frog is not actually poisonous – it generates its protection from its diet of poisonous ants, centipedes and mites .

- Another poisonous creature is the puffer fish, which is actually served as a delicacy in Japan. Although not aggressive or externally dangerous, its extremely high levels of toxicity cause rapid paralysis and death when ingested , and there is at this point no known antidote, hence preparation of puffer fish (called ‘fugu’ in Japan) is restricted only to licensed chefs, In the last ten years, it has been estimated that over 40 people have been killed by fugu poisoning due to incorrect preparation of the fish.

- Although there are many hundreds, even thousands of poisonous fauna, the number of venomous animals on the planet far exceeds their number, perhaps the most well-known of which are snakes and spiders. In the snake world, the most lethal is the Inland Taipan . Able to kill up to 100 humans with the intensity of the toxin in one bite, it can cause death in as little as 45 minutes. Fortunately, they are not only very shy when it comes to human contact, there is also a known antivenin (cure), although this needs to be administered quickly. In the arachnid world, the spider that has been identified as being the most venomous is the Brazilian wandering spider. It is responsible for the most number of human deaths of any spider, but perhaps more alarmingly it is true to its name, hiding during daytime in populated areas , such as inside houses, clothes, footwear and cars.

- When scientifically calculating the most venomous, there are two points which are considered: how many people can be killed with one ounce of the toxin, and how long it takes for death to occur. Without doubt, the overall winner in this category is the box jellyfish. Found mainly in waters in the Indo-Pacific area, they are notorious in Australia and have even been seen as far south as New Zealand. The box jellyfish has tentacles that can be as long as 10 feet (hence their other name ‘Fire Medusae’ after Medusa , a mythological character who had snakes for hair). Each tentacle has billions of stinging cells, which, when they come into contact with others, can shoot a poisonous barb from each cell. These barbs inject toxins which attack the nervous system, heart and skin cells, the intense pain of which can cause human victims to go in shock, drown or die of heart failure before even reaching shore.

-------------------

Great thanks to volunteer Truong Nhat Minh who has contributed these explanations and markings.

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27 – 40 which are based on Reading Passage 3.

PROBLEM SOLVING AND DECISION MAKING

- In the business world, much as in life in general, there are challenges that need to be faced, problems that need solutions and decisions that need to be made and acted upon. Over recent years, the psychology behind problem solving and decision making in a business context has been analysed and taught at a tertiary level.

- Marie Scrive, senior lecturer at Carling University, argues that poor management skills can be identified in many arenas, but few are perhaps as illustrative as the ability to make accurate judgements about a course of action to overcome an obstacle . She argues that there is a tendency for decisions to be made quickly, leading to only short term solutions and a recurrence of the problem at a later date. Pressure from other managers, senior staff or even employees can cause those in middle management to make decisions based quickly, reacting at speed to a problem that would have been better solved by a calmer, more inclusive style of management , However, Martin Hewings, author of Strategic Thinking, believes that the root of the issue is not in the speed at which a response is required but in a flawed way of looking at the problem from the outset. His argument is that most repetitive problems are actually not permanently resolved because of a lack of focus as to the true nature of the problem . He advocates a system whereby the problem must be clearly defined before the appropriate course of action can be decided upon, and this is achieved by applying questions to the problem itself: why is this happening? When is this happening? With whom is this happening ?

- Garen Filke, Managing Director of a large paper supply company, has put Hewings’ steps to the test , and although he referred to the results as ‘potentially encouraging’, there remains the feeling that the focus on who is causing the problem, and this in itself is the main reason for any implemented solution to falter if not fail. With over 30 years of management experience, Filke holds that looking at the problem as an organic entity in itself, without reference to who may be at fault, or at least exacerbating the issue, is the only way to find a lasting solution. Finger-pointing and blaming leads to an uncomfortable work environment where problems grow, and ultimately have a detrimental effect on the productivity of the workplace .

- Anne Wicks believes that our problem solving abilities are first run through five distinct filters, and that good managers are those that can negotiate these filters to arrive at an unbiased, logical and clear solution . Wicks has built the filters into a ladder through which all decisions have the potential to be coloured, the first step being programming – from the day we are born, there is an amount of conditioning that means we accept or reject certain points of view almost a reflex action. Programming will of course vary from person to person, but is often more marked when comparing nationalities. Our programming is the base of our character, but this is then built on by our beliefs, remembering that for someone to believe something does not necessarily mean it is true . So having built from programming to belief, Wicks argues that next on the ladder are our feelings – how we personally react to an issue will skew how we look at solving it. If you feel that someone involved is being unfair or unreasonable, then a solution could over-compensate for this, which of course would not be effective in the long run. This has the potential to impact on the next step – our attitudes. This involves not only those attitudes that are resistant to change, but also the daily modifications in how we feel – our mood . A combination of all these steps on the ladder culminate in our actions – what we choose to do or not do – and this is the step that most directly controls the success or failure of the decision making process.

- For some, however, the more psycho-analytical approach to problem solving has little place in a business decision – a point of view held by John Tate, former CEO of Allied Enterprise and Shipping, who believes the secret behind a solid decision is more mechanical. Tate argues that a decision should be made after a consideration of all alternatives, and a hierarchical structure that then takes responsibility for the decision and, most importantly, follows that decision through to verify whether the problem has indeed been resolved. From his point of view, a flawed decision is not one that did not work, but one that was decided on by too many people leaving no single person with sufficient accountability to ensure its success.

Thank you for contacting us!

We have received your message.

We will get back within 48 hours.

You have subscribed successfully.

Thank you for your feedback, we will investigate and resolve the issue within 48 hours.

Your answers has been saved successfully.

Add Credits

You do not have enough iot credits.

Your account does not have enough IOT Credits to complete the order. Please purchase IOT Credits to continue.

Academic IELTS Reading: Test 2 Reading passage 3; How to make wise decisions; with best solutions and detailed explanations

This Academic IELTS Reading post focuses on solutions to IELTS Reading Test 2 Reading Passage 3 titled ‘ How to make wise decisions’ . This is a targeted post for IELTS candidates who have big problems finding out and understanding Reading Answers in the AC module. This post can guide you to the best to understand every Reading answer without much trouble. Finding out IELTS Reading answers is a steady process, and this post will assist you in this respect.

Academic IELTS Reading Module

Reading Passage 3: Questions 27-40

The headline of the passage: How to make wise decisions

Questions 27-30: Multiple-choice questions

[This type of question asks you to choose a suitable answer from the options using the knowledge you gained from the passage. Generally, this question is found as the last question so you should not worry much about it. Finding all the answers to previous questions gives you a good idea about the title.]

Question no. 27: What point does the writer make in the first paragraph?

Keywords for the question: point, writer make, first paragraph,

In the first paragraph, take a close look at line no. 3, “ . .. .. it isn’t an exceptional trait possessed by a small handful of bearded philosophers after all – .. .. .. .”

Here, the lines suggest that our basic assumption that ‘wisdom is an exceptional trait possessed by a small handful of bearded philosophers’ may not be correct.

So, the answer is: B (A basic assumption about wisdom may be wrong.)

Question no. 28: What does Igor Grossmann suggest about the ability to make wise decisions?

Keywords for the question: Igor Grossmann, suggest, ability, make wise decisions,

The first lines of the second paragraph have the answer to this question. Here, the author of the text writes, “‘It appears that experiential, situational and cultural factors are even more powerful in shaping wisdom than previously imagined ,’ says Associate Professor Igor Grossmann of the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. .. .. .”

Here, experiential, situational and cultural factors are even more powerful = The importance of certain influences, more powerful . . .. than previously imagined = underestimated,

So, the answer is: C (The importance of certain influences on it was underestimated.)

Question no. 29: According to the third paragraph, Grossmann claims that the level of wisdom an individual shows –

Keywords for the question: third paragraph, Grossmann, claims, level of wisdom, an individual shows,

The answer is found in the last lines of paragraph no. 3, “ . . .. .. Some situations are likely to promote wisdom than others .”

Here, the lines suggest that the level of wisdom that an individual shows can be different in different situations, or, circumstances.

So, the answer is: B (will be different in different circumstances.)

Question no. 30: What is described in the fifth paragraph?

Keywords for the question: described, fifth paragraph,

The answer is in paragraph no. 5, in lines 3-7, “ . . . .. Research suggest that when adopting a first-person viewpoint we focus on ‘the focal features of the environment’ and when we adopt a third-person, ‘observer’ viewpoint we reason more broadly and focus more on interpersonal and moral ideals such as justice and impartiality. Looking at problems from this more expansive viewpoint appears to foster cognitive processes related to wise decisions .”

Here, third-person, ‘observer’ viewpoint, or, this more expansive viewpoint = a recommended strategy, appears to foster cognitive processes related to wise decisions = can help people to reason wisely,

So, the answer is: D (a recommended strategy that can help people to reason wisely.)

Questions 31-35: Completing summary with a list of words

[In this type of question, candidates are asked to complete a summary with a list of words taken from the passage. Candidates must write the correct letter (not the words) as the answers. Keywords and synonyms are important to find answers correctly. Generally, this type of question maintains a sequence. Find the keywords in the passage and you are most likely to find the answers.]

Title of the summary: The characteristics of wise reasoning

Question no. 31: Igor Grossmann and colleagues have established four characteristics which enable us to make wise decisions. It is important to have a certain degree of _________ regarding the extent of our knowledge, . .. . . .. .

Keywords for the question: Igor Grossmann and colleagues, established, four characteristics, enable us, make wise decisions, important to have, certain degree of, extent of knowledge,

Take a look at paragraph no. 4. Here, the writer of the text says in the beginning, “Coming up with a definition of wisdom is challenging, but Grossmann and his colleagues have identified four key characteristics as part of a framework of wise reasoning . One is intellectual humility or recognition of the limits of our own knowledge, …. . .. .”

Here, wise reasoning = wise decisions, humility = modesty,

So, the answer is: D (modesty)

Question no. 32: .. . . .. and to take into account __________ which may not be the same as our own.

Keywords for the question: take into account, may not be, the same, as our own,

In paragraph no. 4, lines 3-4 say “ . .. and another is appreciation of perspectives wider than the issue at hand .”

Here, appreciation = to take into account, perspectives = opinions, wider than the issue at hand = may not be the same as our own,

So, the answer is: A (opinions)

Question no. 33: We should also be able to take a broad _________ of any situation.

Keywords for the question: should also be able, take a broad, any situation,

The final lines of paragraph no. 4 say, “ . . .. . Sensitivity to the possibility of change in social relations is also key, along with compromise or integration of different attitudes and beliefs .”

Here, compromise or integration = we should also be able to take, different = broad, attitudes and beliefs = view,

So, the answer is: C (view)

Question no. 34: Grossmann also believes that it is better to regard scenarios with ___________.

Keywords for the question: Grossmann, believes, better, regard scenarios,

In paragraph no. 5, the answer is at the very beginning in lines 1-3, “ Grossmann and his colleagues have also found that one of the most reliable ways to support wisdom in our own day-to-day decisions is to look at scenarios from a third-party perspective , as though giving advice to a friend. .. ..”

Here, look at scenarios = regard scenarios, third-party perspective = objectivity,

So, the answer is: F (objectivity)

Question no. 35: By avoiding the first-person perspective, we focus more on ________ and on other moral ideals, which in turn leads to wiser decision-making.

Keywords for the question: by avoiding, first-person perspective, focus more on, other moral ideals, in turn, leads to, wiser decision-making,

The answer lies in lines 3-6 of paragraph no. 5, “ . . .. . Research suggests that when adopting a first-person viewpoint we focus on ‘the focal features of the environment’ and when we adopt a third-person, ‘observer’ viewpoint we reason more broadly and focus more on interpersonal and moral ideals such as justice and impartiality . .. .. …”

Here, when we adopt a third-person, ‘observer’ viewpoint = By avoiding the first-person perspective, justice and impartiality = fairness,

So, the answer is: G (fairness)

Questions 36-40: TRUE, FALSE, NOT GIVEN

[In this type of question, candidates are asked to find out whether:

The statement in the question agrees with the information in the passage – TRUE The statement in the question contradicts the information in the passage – FALSE If there is no information on this – NOT GIVEN

For this type of question, you can divide each statement into three independent pieces and make your way through with the answer.]

Question no. 36: Students participating in the job prospects experiment could choose one of two perspectives to take.

Keywords for the question: students, participating, job prospects experiment, could choose, one of two perspectives, to take,

In lines 1-4 of paragraph no. 7, the writer says, “For example, in one experiment that took place during the peak of a recent economic recession, graduating college seniors were asked to reflect on their job prospects. The students were instructed to imagine their career either ‘as if you were a distant observer’ or ‘before your own eyes as if you were right there’. … … ..”

Here, graduating college seniors = students, The students were instructed to imagine = the students could NOT choose,

So, the answer is: FALSE

Question no. 37: Participants in the couples experiment were aware that they were taking part in a study about wise reasoning.

Keywords for the question: Participants in the Santa Cruz study, more accurate, identifying, laughs of friends, than, strangers,

Paragraph no. 8 talks about the couples’ experiment. However, there is no mention of whether the participants were aware or not that they were taking part in a study about wise reasoning.

So, the answer is: NOT GIVEN

Question no. 38: In the couples experiments, the length of the couples’ relationships had an impact on the results.

Keywords for the question: couples experiments, length, couples’ relationships, had an impact, on the results,

Again, we do not find any mention of impact due to the length of the couples’ relationships.

Question no. 39: In both experiments, the participants who looked at the situation from a more detached viewpoint tended to make wiser decisions.

Keywords for the question: both experiments, participants, looked to the situation, more detached viewpoint, tended to, make wiser decisions,

The answer lies in the final lines of paragraph no. 7 and 8.

First, in paragraph no. 7, lines 4-5 say, “ .. . .. Participants in the group assigned to the ‘ distant observer ’ role displayed more wisdom-related reasoning . …. .”

Here, ‘distant observer’ = more detached viewpoint,

Then, in lines 4-5 of paragraph no. 8, the author says, “ . .. . Couples in the ‘other’s eyes’ condition were significantly more likely to rely on wise reasoning . .. . .. .”

Here, ‘other’s eyes’ condition = more detached viewpoint,

So, the answer is: TRUE

Question no. 40: Grossmann believes that a person’s wisdom is determined by their intelligence to only a very limited extent.

Keywords for the question: Grossmann, believes, a person’s wisdom, determined by, intelligence, only a very limited extent,

In the final paragraph, the author mentions in lines 1-3, “We might associate wisdom with intelligence or particular personality traits, but research shows only a small positive relationship between wise thinking and crystallized intelligence and the personality traits of openness and agreeableness. . .. ..”

Here, small positive relationship between wise thinking and crystallized intelligence = a person’s wisdom is determined by their intelligence to only a very limited extent,

Click here for solutions to passage 1: The White Horse of Uffington

Click here for solutions to passage 2: I Contain Multitudes

4 thoughts on “ Academic IELTS Reading: Test 2 Reading passage 3; How to make wise decisions; with best solutions and detailed explanations ”

- Pingback: Academic IELTS Reading: Test 2 Reading passage 2; I contain multitudes; with best solutions and detailed explanations - IELTS Deal

- Pingback: Academic IELTS Reading: Test 2 Reading passage 1; The White Horse of Uffington; with all solutions and detailed explanations - IELTS Deal

Hi thanks in million for your efforts as you provide solutions for complicated reading passages but may I know where I can check cambridge book 1 solutions for all three passages

36 incorrect question and answer as well

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Academic IELTS Reading: Test 2 Passage 1; The Dead Sea Scrolls; with top solutions and best explanations

This Academic IELTS Reading post focuses on solutions to an IELTS Reading Test 2 passage 1 that has a passage titled ‘The Dead Sea Scrolls’. This is a targeted post for Academic IELTS candidates who have major problems locating and understanding Reading Answers in the AC module. This post can guide you the best to understand […]

Academic IELTS Reading: Test 1 Reading passage 3; To catch a king; with best solutions and explanations

This Academic IELTS Reading post focuses on solutions to an IELTS Reading Test 1 Reading Passage 3 titled ‘To catch a king’. This is a targeted post for IELTS candidates who have great problems finding out and understanding Reading Answers in the AC module. This post can guide you the best to understand every Reading answer […]

Welcome Guest!

- IELTS Listening

- IELTS Reading

- IELTS Writing

- IELTS Writing Task 1

- IELTS Writing Task 2

- IELTS Speaking

- IELTS Speaking Part 1

- IELTS Speaking Part 2

- IELTS Speaking Part 3

- IELTS Practice Tests

- IELTS Listening Practice Tests

- IELTS Reading Practice Tests

- IELTS Writing Practice Tests

- IELTS Speaking Practice Tests

- All Courses

- IELTS Online Classes

- OET Online Classes

- PTE Online Classes

- CELPIP Online Classes

- Free Live Classes

- Australia PR

- Germany Job Seeker Visa

- Austria Job Seeker Visa

- Sweden Job Seeker Visa

- Study Abroad

- Student Testimonials

- Our Trainers

- IELTS Webinar

- Immigration Webinar

Decision Making and Happiness – IELTS Reading Answers

11 min read

Updated On Dec 01, 2023

Share on Whatsapp

Share on Email

Share on Linkedin

Limited-Time Offer : Access a FREE 10-Day IELTS Study Plan!

Since IELTS Reading is considered the second easiest module of the exam after Listening, try to solve and review Decision Making and Happiness Reading and similar passages to ensure that your reading skills are up to the mark.

The Academic passage, Decision Making and Happiness is a reading passage that appeared in an IELTS Test. Since questions get repeated in the IELTS exam, these passages are ideal for practice. If you want more practice, try taking an IELTS reading practice test.

The question types found in the Decision Making and Happiness passage are:

- Matching Features (Q. 1-4)

- True/False/Not Given (Q. 5-10)

- Multiple-choice questions (Q. 11-13)

Want to boost your IELTS Reading score? Check out the video below!

Reading Passage

Decision making and happiness.

A Americans today choose among more options in more parts of life than has ever been possible before. To an extent, the opportunity to choose enhances our lives. It is only logical to think that if some choices are good, more is better; people who care about having infinite options will benefit from them, and those who do not can always just ignore the 273 versions of cereal they have never tried. Yet recent research strongly suggests that, psychologically, this assumption is wrong, with 5% lower percentage announcing they are happy. Although some choices are undoubtedly better than none, more is not always better than less.

B Recent research offers insight into why many people end up unhappy rather than pleased when their options expand. We began by making a distinction between “maximizers” (those who always aim to make the best possible choice) and “satisficers” (those who aim for “good enough,” whether or not better selections might be out there).

C In particular, we composed a set of statements—the Maximization Scale—to diagnose people’s propensity to maximize. Then we had several thousand people rate themselves from 1 to 7 (from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”) on such statements as “I never settle for second best.” We also evaluated their sense of satisfaction with their decisions. We did not define a sharp cutoff to separate maximizers from satisficers, but in general, we think of individuals whose average scores are higher than 4 (the scale’s midpoint) as maxi- misers and those whose scores are lower than the midpoint as satisficers. People who score highest on the test—the greatest maximizers—engage in more product comparisons than the lowest scorers, both before and after they make purchasing decisions, and they take longer to decide what to buy. When satisficers find an item that meets their standards, they stop looking. But maximizers exert enormous effort reading labels, checking out consumer magazines and trying new products. They also spend more time comparing their purchasing decisions with those of others.

D We found that the greatest maximizers are the least happy with the fruits of their efforts. When they compare themselves with others, they get little pleasure from finding out that they did better and substantial dissatisfaction from finding out that they did worse. They are more prone to experiencing regret after a purchase, and if their acquisition disappoints them, their sense of well-being takes longer to recover. They also tend to brood or ruminate more than satisficers do.

E Does it follow that maximizers are less happy in general than satisficers? We tested this by having people fill out a variety of questionnaires known to be reliable indicators of wellbeing. As might be expected, individuals with high maximization scores experienced less satisfaction with life and were less happy, less optimistic and more depressed than people with low maximization scores. Indeed, those with extreme maximization ratings had depression scores that placed them in the borderline of clinical range.

F Several factors explain why more choice is not always better than less, especially for maximisers. High among these are “opportunity costs.” The quality of any given option cannot be assessed in isolation from its alternatives. One of the “costs” of making a selection is losing the opportunities that a different option would have afforded. Thus, an opportunity cost of vacationing on the beach in Cape Cod might be missing the fabulous restaurants in the Napa Valley. Early Decision Making Research by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed that people respond much more strongly to losses than gains. If we assume that opportunity costs reduce the overall desirability of the most preferred choice, then the more alternatives there are, the deeper our sense of loss will be and the less satisfaction we will derive from our ultimate decision.

G The problem of opportunity costs will be better for a satisficer. The latter’s “good enough” philosophy can survive thoughts about opportunity costs. In addition, the “good enough” standard leads to much less searching and inspection of alternatives than the maximizer’s “best” standard. With fewer choices under consideration, a person will have fewer opportunity costs to subtract.

H Just as people feel sorrow about the opportunities they have forgone, they may also suffer regret about the option they settled on. My colleagues and I devised a scale to measure proneness to feeling regret, and we found that people with high sensitivity to regret are less happy, less satisfied with life, less optimistic and more depressed than those with low sensitivity. Not surprisingly, we also found that people with high regret sensitivity tend to be maximizers. Indeed, we think that worry over future regret is a major reason that individuals become maximizers. The only way to be sure you will not regret a decision is by making the best possible one. Unfortunately, the more options you have and the more opportunity costs you incur, the more likely you are to experience regret.

I In a classic demonstration of the power of sunk costs, people were offered season subscriptions to a local theatre company. Some were offered the tickets at full price and others at a discount. Then the researchers simply kept track of how often the ticket purchasers actually attended the plays over the course of the season. Full-price payers were more likely to show up at performances than discount payers. The reason for this, the investigators argued, was that the full-price payers would experience more regret if they did not use the tickets because not using the more costly tickets would constitute a bigger loss. To increase sense of happiness, we can decide to restrict our options when the decision is not crucial. For example, make a rule to visit no more than two stores when shopping for clothing.

Questions 1-4

A “maximizers”

B “satisficers”

C neither “maximizers” nor “satisficers”

D both “maximizers” and “satisficers”

1 rated to the Maximization Scale of making choice

2 don’t take much time before making a decision

3 are likely to regret about the choice in the future

4 choose the highest price in the range of purchase

Questions 5-8

5 In today’s world, since society is becoming wealthier, people are happier.

6 In society, there are more maximisers than satisficers.

7 People tend to react more to losses than gains.

8 Females and males acted differently in the study of choice-making.

Questions 9-12

9 The Maximization Scale is aimed to

A know the happiness when they have more choices.

B measure how people are likely to feel after making choices.

C help people make better choices.

D reduce the time of purchasing.

10 According to the text, what is the result of more choices?

A People can make choices more easily

B Maximizers are happier to make choices.

C Satisficers are quicker to make wise choices.

D People have more tendency to experience regret.

11 The example of a theatre ticket is to suggest that

A they prefer to use more money when buying tickets.

B they don’t like to spend more money on theatre.

C higher-priced things would induce more regret if not used properly

D full-price payers are real theatre lovers.

12 How to increase happiness when making a better choice?

A use less time

B make more comparisons

C buy more expensive products

D limit the number of choices in certain situations

Want to improve your IELTS Academic Reading score?

Grab Our IELTS Reading Ebook Today!

Decision Making and Happiness Reading Answers With Location and Explanation

Read further for the explanation part of the reading answer.

1 Answer: D

Question type: Matching Features

Answer Location: Paragraph C

Answer explanation: “D” (both “maximizers” and “satisficers”). In paragraph C, the Maximization Scale is described as a tool used to diagnose people’s propensity to maximize. This scale is used to determine whether individuals are maximizers or satisficers, so it applies to both groups.

2 Answer: B

Answer Location: Paragraph G

Answer explanation: Although this information is not explicitly stated in the passage, it can be inferred from paragraph G, which contrasts the behaviour of maximizers (who take more time) with satisficers. Satisficers are more likely to make quicker decisions. Hence the answer is B.

3 Answer: A

Answer Location: Paragraph H

Answer explanation: “A” (“maximizers”). This information is found in paragraph H, which discusses the sensitivity to regret and how maximizers are more prone to experiencing regret after making choices. Hence the answer is A.

4 Answer: C

Answer explanation: The passage does not explicitly state that either maximizers or satisficers consistently choose the highest price. Maximizers aim for the best possible choice, which doesn’t necessarily mean the highest price, and satisficers aim for “good enough,” which may not involve choosing the highest price. Hence the answer is C.

5 Answer: False

Question type: True/False/Not given

Answer Location: Paragraph E

Answer explanation: “ Indeed, those with extreme maximization ratings had depression scores that placed them in the borderline of clinical range.” The passage does not suggest that people are becoming happier due to having more choices; in fact, it discusses how more choices can lead to unhappiness for some individuals.

6 Answer: Not Given

Answer Location: N.A.

Answer explanation: There is no information about the given sentence in the paragraphs.

7 Answer: True

Answer Location: Paragraph F

Answer explanation: “ People respond much more strongly to losses than gains. Opportunity costs reduce the overall desirability of the most preferred choice, then the more alternatives there are, the deeper our sense of loss will be and the less satisfaction we will derive from our ultimate decision.” This mentions that people respond much more strongly to losses than gains, which supports the statement that people tend to react more to losses.

8 Answer: Not Given

Answer explanation: The passage doesn’t provide information about gender-based differences in the study of choice-making.

9 Answer: B

Question type: Multiple Choice Question

Answer explanation: The Maximization Scale is used to diagnose people’s propensity to maximize, and it is related to how they feel after making choices. Hence the answer is B.

10 Answer: D

Answer explanation: The passage discusses that more choices can lead to increased regret, which aligns with the statement. Hence the answer is D.

11 Answer: C

Answer Location: Paragraph I

Answer explanation: The example of the theatre ticket illustrates that people who paid a higher price for the tickets were more likely to attend the performances to avoid the regret of wasting a more substantial investment. Hence the answer is C.

12 Answer: D

Answer explanation: The passage suggests that limiting options or choices in certain situations can help increase happiness when making decisions. Hence the answer is D.

Tips for Answering the Question Types in the Decision Making and Happiness Reading Passage

Let us check out some quick tips to answer the types of questions in the ‘Decision Making and Happiness’ Reading passage.

Matching Features:

Matching Features is a type of IELTS reading question that requires you to match a list of features to the correct people, places, or things in a passage.

To answer matching features questions, you can use the following strategies:

- Read the features first: This will give you an idea of the types of information that you are looking for in the passage.

- Read the passage quickly: This will give you a general understanding of the content of the passage.

- Match the features to the people, places , or things: As you read the passage, look for the information that matches each feature.

- Check your answers: Once you have matched all of the features, double-check your answers to make sure that they are correct.

True/False/Not Given:

True/False/Not Given questions are a type of IELTS Reading question that requires you to identify whether a statement is true, false, or not given in the passage.

- True statements are statements that are explicitly stated in the passage.

- False statements are statements that are explicitly contradicted in the passage.

- Not Given statements are statements that are neither explicitly stated nor contradicted in the passage

To answer True/False/Not Given questions, you need to be able to understand the passage and identify the key information. You also need to be able to distinguish between statements that are explicitly stated, contradicted, and not given.

Multiple-Choice Questions:

You will be given a reading passage followed by several questions based on the information in the paragraph in multiple-choice questions. Your task is to understand the question and compare it to the paragraph in order to select the best solution from the available possibilities.

- Before reading the passage, read the question and select the keywords. Check the keyword possibilities if the question statement is short on information.

- Then, using the keywords, read the passage to find the relevant information.

- To select the correct option, carefully read the relevant words and match them with each option.

- You will find several options with keywords that do not correspond to the information.

- Try opting for the elimination method mostly.

- Find the best option by matching the meaning rather than just the keywords.

Great work on attempting to solve the Decision Making and Happiness IELTS reading passage! To crack your IELTS Reading in the first go, try solving more of the recent IELTS reading passages here.

Also Check:

- IELTS Reading Tips and Techniques to Increase your Reading Speed

- How to Do Short Answer Type of Questions in IELTS Reading? | IELTSMaterial.com

- Emigration to the US, How bugs hitch-hike across the galaxy, Finding out about the world from television news – Reading Answers

- What Cookbooks Really Teach Us, Is There More To Video Games Than People Realize?, Seed Vault Guards Resources For The Future – IELTS Reading Answers

- The Loch Ness Monster, Co- Educational Versus Single Sex Classrooms – IELTS Reading Answers

Practice IELTS Writing Task 1 based on report types

Start Preparing for IELTS: Get Your 10-Day Study Plan Today!

Nehasri Ravishenbagam

Nehasri Ravishenbagam, a Senior Content Marketing Specialist and a Certified IELTS Trainer of 3 years, crafts her writings in an engaging way with proper SEO practices. She specializes in creating a variety of content for IELTS, CELPIP, TOEFL, and certain immigration-related topics. As a student of literature, she enjoys freelancing for websites and magazines to balance her profession in marketing and her passion for creativity!

Explore other Reading Actual Tests

Post your Comments

Recent articles.

Kasturika Samanta

Our Offices

Gurgaon city scape, gurgaon bptp.

Step 1 of 3

Great going .

Get a free session from trainer

Have you taken test before?

Please select any option

Get free eBook to excel in test

Please enter Email ID

Get support from an Band 9 trainer

Please enter phone number

Already Registered?

Select a date

Please select a date

Select a time (IST Time Zone)

Please select a time

Mark Your Calendar: Free Session with Expert on

Which exam are you preparing?

Great Going!

WILLPOWER IELTS Reading Passage with Answers

Willpower ielts reading with answers.

Get ready to explore the fascinating world of self-control and decision-making in the IELTS Practice Reading Passage titled “ WILLPOWER ,” also known as “ Decision Fatigue .” This easy-to-understand reading material delves into how our minds handle determination and the challenges of making decisions. Discover practical tips for boosting your willpower and making better choices. Join us on this journey of understanding the strength within you, making the complexities of willpower simple and relatable. Let’s uncover the secrets of self-control together!

Real IELTS Exam Question, Reported On:

READING PASSAGE 3 You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on Reading Passage 3 below.

A Although willpower does not shape our decisions, it determines whether and how long we can follow through on them. It almost single-handedly determines life outcomes. Interestingly, research suggests the general population is indeed aware of how essential willpower is to their wellbeing; survey participants routinely identify a ‘lack of willpower’ as the major impediment to making beneficial life changes. There are, however, misunderstandings surrounding the nature of willpower and how we can acquire more of it. There is a widespread misperception, for example, that increased leisure time would lead to subsequent increases in willpower.

B Although the concept of willpower is often explained through single-word terms, such as ‘resolve’ or ‘drive’, it refers in fact to a variety of behaviours and situations. There is a common perception that willpower entails resisting some kind of a ‘treat’, such as a sugary drink or a lazy morning in bed, in favour of decisions that we know are better for us, such as drinking water or going to the gym. Of course this is a familiar phenomenon for all. Yet willpower also involves elements such as overriding negative thought processes, biting your tongue in social situations, or persevering through a difficult activity. At the heart of any exercise of willpower, however, is the notion of ‘delayed gratification’, which involves resisting immediate satisfaction for a course that will yield greater or more permanent satisfaction in the long run.

C Scientists are making general investigations into why some individuals are better able than others to delay gratification and thus employ their willpower, but the genetic or environmental origins of this ability remain a mystery for now. Some groups who are particularly vulnerable to reduced willpower capacity, such as those with addictive personalities, may claim a biological origin for their problems. What is clear is that levels of willpower typically remain consistent over time (studies tracking individuals from early childhood to their adult years demonstrate a remarkable consistency in willpower abilities). In the short term, however, our ability to draw on willpower can fluctuate dramatically due to factors such as fatigue, diet and stress. Indeed, research by Matthew Gailliot suggests that willpower, even in the absence of physical activity, both requires and drains blood glucose levels, suggesting that willpower operates more or less like a ‘muscle’, and, like a muscle, requires fuel for optimum functioning.

D These observations lead to an important question: if the strength of our willpower at the age of thirty-five is somehow pegged to our ability at the age of four, are all efforts to improve our willpower certain to prove futile? According to newer research, this is not necessarily the case. Gregory M. Walton, for example, found that a single verbal cue – telling research participants how strenuous mental tasks could ‘energise’ them for further challenging activities – made a profound difference in terms of how much willpower participants could draw upon to complete the activity. Just as our willpower is easily drained by negative influences, it appears that willpower can also be boosted by other prompts, such as encouragement or optimistic self-talk.

E Strengthening willpower thus relies on a two-pronged approach: reducing negative influences and improving positive ones. One of the most popular and effective methods simply involves avoiding willpower depletion triggers, and is based on the old adage, ‘out of sight, out of mind’. In one study, workers who kept a bowl of enticing candy on their desks were far more likely to indulge than those who placed it in a desk drawer. It also appears that finding sources of motivation from within us may be important. In another study, Mark Muraven found that those who felt compelled by an external authority to exert self-control experienced far greater rates of willpower depletion than those who identified their own reasons for taking a particular course of action. This idea that our mental convictions can influence willpower was borne out by Veronika Job. Her research indicates that those who think that willpower is a finite resource exhaust their supplies of this commodity long before those who do not hold this opinion.

F Willpower is clearly fundamental to our ability to follow through on our decisions but, as psychologist Roy Baumeister has discovered, a lack of willpower may not be the sole impediment every time our good intentions fail to manifest themselves. A critical precursor, he suggests, is motivation – if we are only mildly invested in the change we are trying to make, our efforts are bound to fall short. This may be why so many of us abandon our New Year’s Resolutions – if these were actions we really wanted to take, rather than things we felt we ought to be doing, we would probably be doing them already. In addition, Muraven emphasises the value of monitoring progress towards a desired result, such as by using a fitness journal, or keeping a record of savings toward a new purchase. The importance of motivation and monitoring cannot be overstated. Indeed, it appears that, even when our willpower reserves are entirely depleted, motivation alone may be sufficient to keep us on the course we originally chose.

Questions 27-33 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 27–32 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information FALSE if the statement contradicts the information NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

27 Willpower is the most significant factor in determining success in life. 28 People with more free time typically have better willpower. 29 Willpower mostly applies to matters of diet and exercise. 30 The strongest indicator of willpower is the ability to choose long-term rather than short-term rewards. 31 Researchers have studied the genetic basis of willpower. 32 Levels of willpower usually stay the same throughout our lives. 33 Regular physical exercise improves our willpower ability.

Questions 34 –39 Look at the following statements (Questions 37–40) and the list of researchers below. Match each statement with the correct person, A–D. Write the correct letter, A–D, in boxes 37–40 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use some letters more than once.

This researcher …

34 identified a key factor that is necessary for willpower to function. 35 suggested that willpower is affected by our beliefs. 36 examined how our body responds to the use of willpower. 37 discovered how important it is to make and track goals. 38 found that taking actions to please others decreases our willpower. 39 found that willpower can increase through simple positive thoughts.

List of People

A Matthew Gailliot B Gregory M. Walton C Mark Muraven D Veronika Job E Roy Baumeister

Question 40 Which of the following is NOT mentioned as a factor in willpower?

Willpower is affected by:

A physical factors such as tiredness B our fundamental ability to delay pleasure C the levels of certain chemicals in our brains D environmental cues such as the availability of a trigger

Willpower IELTS Reading Answers

31. NOT GIVEN

33. NOT GIVEN

Also Check : Museum of Lost Objects IELTS Reading with Answers

Oh hi there! It’s nice to meet you.

Sign up to receive awesome content in your inbox, every week.

We promise not to spam you or share your Data. 🙂

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Oh Hi there! It’s nice to meet you.

We promise not to Spam or Share your Data. 🙂

Related Posts

Pacific Navigation and Voyaging IELTS Reading

Recent IELTS Exam 23 March 2024 India Question Answers

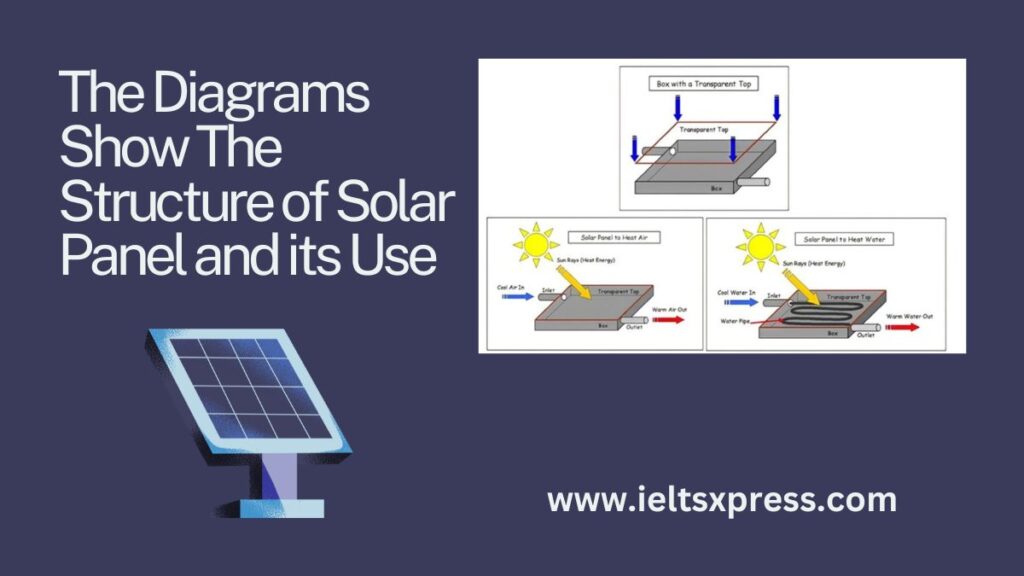

The Diagrams Show the Structure of Solar Panel and its Use

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Yes, add me to your mailing list

Start typing and press enter to search

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.4: Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20754

Learning Objectives

- Learn to understand the problem.

- Learn to combine creative thinking and critical thinking to solve problems.

- Practice problem solving in a group.

Much of your college and professional life will be spent solving problems; some will be complex, such as deciding on a career, and require time and effort to come up with a solution. Others will be small, such as deciding what to eat for lunch, and will allow you to make a quick decision based entirely on your own experience. But, in either case, when coming up with the solution and deciding what to do, follow the same basic steps.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

Group Think: Effective Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a process of generating ideas for solutions in a group. This method is very effective because ideas from one person will trigger additional ideas from another. The following guidelines make for an effective brainstorming session:

- Decide who should moderate the session. That person may participate, but his main role is to keep the discussion flowing.

- Define the problem to be discussed and the time you will allow to consider it.

- Write all ideas down on a board or flip chart for all participants to see.

- Encourage everyone to speak.

- Do not allow criticism of ideas. All ideas are good during a brainstorm. Suspend disbelief until after the session. Remember a wildly impossible idea may trigger a creative and feasible solution to a problem.

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team.

Decisions, Decisions

You will be called on to make many decisions in your life. Some will be personal, like what to major in, or whether or not to get married. Other times you will be making decisions on behalf of others at work or for a volunteer organization. Occasionally you will be asked for your opinion or experience for decisions others are making. To be effective in all of these circumstances, it is helpful to understand some principles about decision making.

First, define who is responsible for solving the problem or making the decision. In an organization, this may be someone above or below you on the organization chart but is usually the person who will be responsible for implementing the solution. Deciding on an academic major should be your decision, because you will have to follow the course of study. Deciding on the boundaries of a sales territory would most likely be the sales manager who supervises the territories, because he or she will be responsible for producing the results with the combined territories. Once you define who is responsible for making the decision, everyone else will fall into one of two roles: giving input, or in rare cases, approving the decision.

Understanding the role of input is very important for good decisions. Input is sought or given due to experience or expertise, but it is up to the decision maker to weigh the input and decide whether and how to use it. Input should be fact based, or if offering an opinion, it should be clearly stated as such. Finally, once input is given, the person giving the input must support the other’s decision, whether or not the input is actually used.

Consider a team working on a project for a science course. The team assigns you the responsibility of analyzing and presenting a large set of complex data. Others on the team will set up the experiment to demonstrate the hypothesis, prepare the class presentation, and write the paper summarizing the results. As you face the data, you go to the team to seek input about the level of detail on the data you should consider for your analysis. The person doing the experiment setup thinks you should be very detailed, because then it will be easy to compare experiment results with the data. However, the person preparing the class presentation wants only high-level data to be considered because that will make for a clearer presentation. If there is not a clear understanding of the decision-making process, each of you may think the decision is yours to make because it influences the output of your work; there will be conflict and frustration on the team. If the decision maker is clearly defined upfront, however, and the input is thoughtfully given and considered, a good decision can be made (perhaps a creative compromise?) and the team can get behind the decision and work together to complete the project.

Finally, there is the approval role in decisions. This is very common in business decisions but often occurs in college work as well (the professor needs to approve the theme of the team project, for example). Approval decisions are usually based on availability of resources, legality, history, or policy.

Key Takeaways

- Effective problem solving involves critical and creative thinking.

The four steps to effective problem solving are the following:

- Define the problem

- Narrow the problem

- Generate solutions

- Choose the solution

- Brainstorming is a good method for generating creative solutions.

- Understanding the difference between the roles of deciding and providing input makes for better decisions.

Checkpoint Exercises

Gather a group of three or four friends and conduct three short brainstorming sessions (ten minutes each) to generate ideas for alternate uses for peanut butter, paper clips, and pen caps. Compare the results of the group with your own ideas. Be sure to follow the brainstorming guidelines. Did you generate more ideas in the group? Did the quality of the ideas improve? Were the group ideas more innovative? Which was more fun? Write your conclusions here.

__________________________________________________________________

Using the steps outlined earlier for problem solving, write a plan for the following problem: You are in your second year of studies in computer animation at Jefferson Community College. You and your wife both work, and you would like to start a family in the next year or two. You want to become a video game designer and can benefit from more advanced work in programming. Should you go on to complete a four-year degree?

Define the problem: What is the core issue? What are the related issues? Are there any requirements to a successful solution? Can you come up with a metaphor to describe the issue?

Narrow the problem: Can you break down the problem into smaller manageable pieces? What would they be?

Generate solutions: What are at least two “right” answers to each of the problem pieces?

Choose the right approach: What do you already know about each solution? What do you still need to know? How can you get the information you need? Make a list of pros and cons for each solution.

Problem Solving and Decision Making

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Learn to understand the problem.

- Learn to combine creative thinking and critical thinking to solve problems.

- Practice problem solving in a group.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

Group Think: Effective Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a process of generating ideas for solutions in a group. This method is very effective because ideas from one person will trigger additional ideas from another. The following guidelines make for an effective brainstorming session:

- Decide who should moderate the session. That person may participate, but his main role is to keep the discussion flowing.

- Define the problem to be discussed and the time you will allow to consider it.

- Write all ideas down on a board or flip chart for all participants to see.

- Encourage everyone to speak.

- Do not allow criticism of ideas. All ideas are good during a brainstorm. Suspend disbelief until after the session. Remember a wildly impossible idea may trigger a creative and feasible solution to a problem.

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team.

Decisions, Decisions

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Effective problem solving involves critical and creative thinking.

- Define the problem

- Narrow the problem

- Generate solutions

- Choose the solution

- Brainstorming is a good method for generating creative solutions.

- Understanding the difference between the roles of deciding and providing input makes for better decisions.

CHECKPOINT EXERCISES

- Gather a group of three or four friends and conduct three short brainstorming sessions (ten minutes each) to generate ideas for alternate uses for peanut butter, paper clips, and pen caps. Compare the results of the group with your own ideas. Be sure to follow the brainstorming guidelines. Did you generate more ideas in the group? Did the quality of the ideas improve? Were the group ideas more innovative? Which was more fun? Write your conclusions here.

- Define the problem: What is the core issue? What are the related issues? Are there any requirements to a successful solution? Can you come up with a metaphor to describe the issue?

- Narrow the problem: Can you break down the problem into smaller manageable pieces? What would they be?

- Generate solutions: What are at least two “right” answers to each of the problem pieces?

- Choose the right approach: What do you already know about each solution? What do you still need to know? How can you get the information you need? Make a list of pros and cons for each solution.

- Success in College. Authored by : anonymous. Located at : http://2012books.lardbucket.org/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of group at table. Authored by : Juhan Sonin. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/6YRkya . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of figure with arrows. Authored by : Impact Hub. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/64TEyQ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

18 4.4 Problem Solving and Decision Making

Learning objectives.

- Learn to understand the problem.

- Learn to combine creative thinking and critical thinking to solve problems.

- Practice problem solving in a group.

Much of your university and professional life will be spent solving problems; some will be complex, such as deciding on a career, and require time and effort to come up with a solution. Others will be small, such as deciding what to eat for lunch, and will allow you to make a quick decision based entirely on your own experience. But, in either case, when coming up with the solution and deciding what to do, follow the same basic steps.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

Video: TED-Ed – “Working Backward to Solve Problems” (length 5:56)

Group Think: Effective Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a proces s of generating ideas for solutions in a group. This method is very effective because ideas from one person will trigger additional ideas from another. The following guidelines make for an effective brainstorming session:

- Decide who should moderate the session. That person may participate, but his main role is to keep the discussion flowing.

- Define the problem to be discussed and the time you will allow to consider it.

- Write all ideas down on a board or flip chart for all participants to see.

- Encourage everyone to speak.

- Do not allow criticism of ideas. All ideas are good during a brainstorm. Suspend disbelief until after the session. Remember a wildly impossible idea may trigger a creative and feasible solution to a problem.

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team.

Decisions, Decisions

You will be called on to make many decisions in your life. Some will be personal, like what to major in, or whether or not to get married. Other times you will be making decisions on behalf of others at work or for a volunteer organization. Occasionally you will be asked for your opinion or experience for decisions others are making. To be effective in all of these circumstances, it is helpful to understand some principles about decision making.

First, define who is responsible for solving the problem or making the decision. In an organization, this may be someone above or below you on the organization chart but is usually the person who will be responsible for implementing the solution. Deciding on an academic major should be your decision, because you will have to follow the course of study. Deciding on the boundaries of a sales territory would most likely be the sales manager who supervises the territories, because he or she will be responsible for producing the results with the combined territories. Once you define who is responsible for making the decision, everyone else will fall into one of two roles: giving input, or in rare cases, approving the decision.

Understanding the role of input is very important for good decisions. Input is sought or given due to experience or expertise, but it is up to the decision maker to weigh the input and decide whether and how to use it. Input should be fact based, or if offering an opinion, it should be clearly stated as such. Finally, once input is given, the person giving the input must support the other’s decision, whether or not the input is actually used.