An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat

Recognizing Depression in the Elderly: Practical Guidance and Challenges for Clinical Management

Maria devita.

1 Department of General Psychology (DPG), University of Padua, Padua, Italy

2 Geriatrics Division, Department of Medicine (DIMED), University of Padua, Padua, Italy

Rossella De Salvo

Adele ravelli, marina de rui, alessandra coin, giuseppe sergi, daniela mapelli.

Depression is one of the most common mood disorders in the late-life population and is associated with poor quality of life and increased morbidity, disability and mortality. Nevertheless, in older adults, it often remains undetected and untreated. This narrative review aims at giving an overview on the main definitions, clinical manifestations, risk and protective factors for depression in the elderly, and at discussing the main reasons for its under/misdiagnosis, such as cognitive decline and their overlapping symptomatology. A practical approach for the global and multidisciplinary care of the older adult with depression, derived from cross-checking evidence emerging from the literature with everyday clinical experience, is thus provided, as a short and flexible “pocket” guide to orient clinicians in recognizing, diagnosing and treating depression in the elderly.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common mood disorders in the late-life population. 1 , 2 The prevalence of depressive disorder in the over 60 years old population is about 5.7%. 3 However, it increases with age, to reach the peak of 27% in over-85 individuals. 1 Interestingly, the prevalence still increases and reaches the 49% in those living in communities or nursing homes, 4 , 5 regardless of the severity or the definition of depression considered. 1

Late-life depression (LLD) can be distinguished according to the age at which the first depression occurred. Early-onset depression (EOD) identifies the persistence or recurrence in old age of a depression previously diagnosed throughout adulthood, while late-onset depression (LOD) represents a depressive disorder developed de novo in old age. 6

DSM 5 identifies a cluster of depressive symptoms, namely depressed mood, loss of interest and pleasure, weight loss or gain, fatigue, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor agitation or retardation, decreased concentration, thoughts of death and/or suicide and worthlessness. 3

However, LLD is characterized by an atypical cluster of symptoms, ie somatic symptoms which are predominant compared to mood symptoms, so it is important to be aware of this particular clinical presentation in order to not underestimate LLD.

Moreover, the complex spectrum of Late-Life Depression (LLD) goes beyond the main diagnostic entities of unipolar depressive disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and persistent depressive disorder. 7 Relevant depressive symptoms which do not fulfill the criteria for a diagnosis of depression have nevertheless a significant clinical relevance, because of their association with poorer quality of life and increased disability; however, they are often undetected and untreated, despite a very small chance of spontaneous remission. 8

Depressive symptoms produce clinically significant distress and impairment in daily life, notching social, familiar, and occupational areas of functioning. Depression is entangled in a bidirectional relationship with somatic morbidity finally resulting in an increase in patients’ burden of disability and frailty and augmenting mortality. 9 In fact, besides being a risk factor and a predictor of poor prognosis for many conditions, like diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, 10–12 depression can be precipitated and perpetuated by chronic medical conditions typical of the aging process. A longitudinal study of 3214 healthy elderly individuals proved that Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), as well as smoking and mobility, vision, and subjective memory impairments, can significantly increase the risk of depression. 13

Thus, the diagnosis of depression is challenging in elderly people, since it often presents with multifaceted and more somatic symptoms compared to adults, 14 thus resembling a “real” medical organic disease. 5

Also, treatment is demanding, because of the complexity of older patients, who more frequently have a pharmacological-resistant depression and require a multidimensional and, possibly, a multi-professional equipe taking charge.

The objective of this review is, on the one hand, to explain the strong impact of geriatric depression on individual and caregivers’ quality of life and the difficulties in recognizing and prescribing the adequate treatment and, on the other hand, to propose a practical approach for the global and multi-disciplinary care of the older adult with depression, from diagnosis up to the definition of a customized treatment. In order to do so, a short and flexible “pocket” guide is here proposed as a tool to orient clinicians in recognizing, diagnosing and treating depression in the elderly. To the best of our knowledge, there is no tool currently available, such as the here proposed pocket guide, thought to be flexible and easily adaptable to the most disparate clinical contexts.

Reviewing the Literature on Geriatric Depression: Definitions, Risk and Protective Factors, Symptomatology and Clinical Variants

Geriatric depression syndrome: characterization and symptomatology.

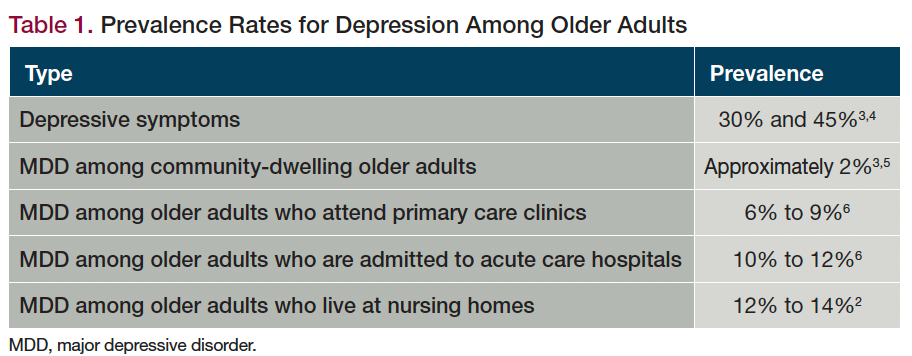

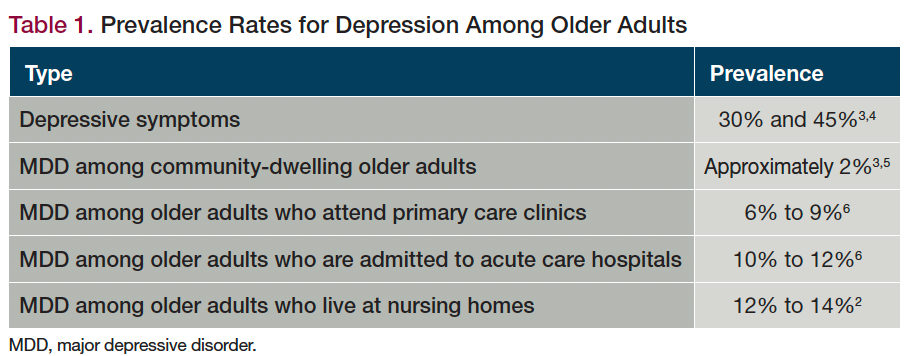

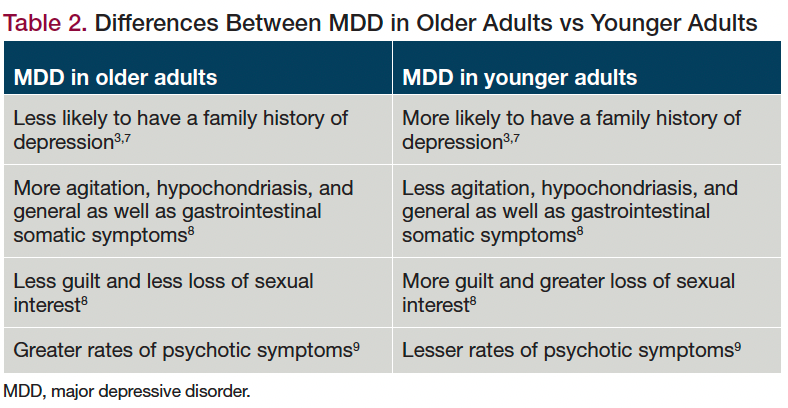

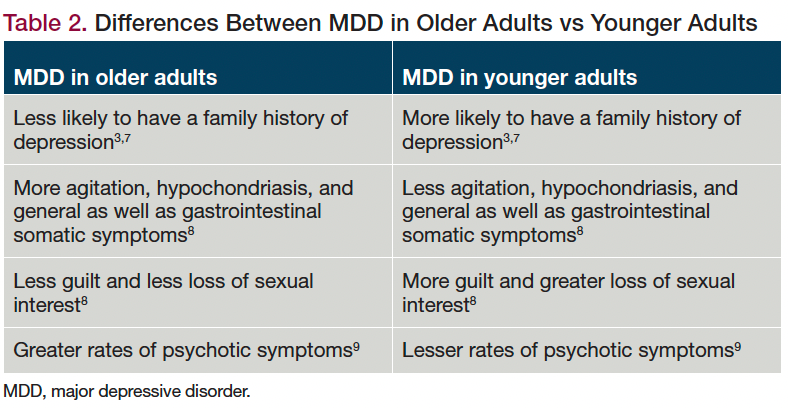

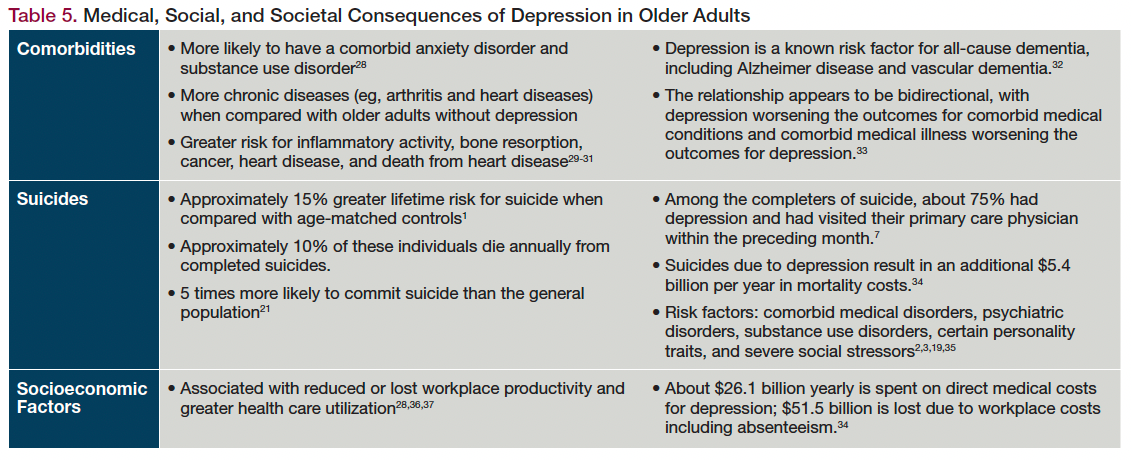

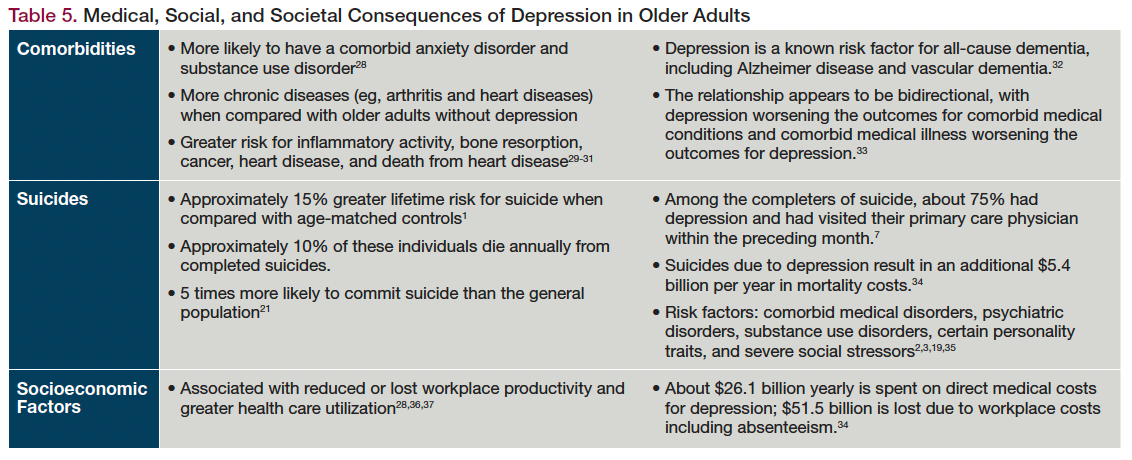

While the depression severity appears to remain stable across the lifespan, what really differentiates depression in middle and old age concerns qualitative differences in the clinical presentation of the symptomatology ( Table 1 ).

Depression Symptoms in Younger and Older Adults: Typical and Atypical Presentation

Abbreviations : *DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders; **GI, gastrointestinal.

As an example, considering depressed mood (sadness or dysphoria) and loss of interest (anhedonia), which are the two core symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) according to the DSM 5, they can be manifested differently in older adults compared younger people, 15 as well as inappropriate guilt or feelings of worthlessness. 16 Notably, regarding the first of these two core symptoms (ie depressed mood), feelings of dysphoria or sadness are frequently absent in older adults, 7 underlying a specific variant of geriatric depression indicated as “depression without sadness”, 17 characterized by lack of interest, sleep difficulties, lack of hope, loss of appetite and thoughts of death.

On the contrary, symptoms like lack of vigor and withdrawal, which are referred to the second core symptom of MDD, are usually more pronounced. In fact, “loss of interest” is usually pronounced, since older adults tend to be more apathetic. 18 Suicidal thoughts are frequent in LLD, together with state of anxiety, especially in the morning. 19

What characterizes even more LLD is a shift towards somatic symptoms, 18 which become prominent and vary in their manifestations compared to early onset depression, although the criteria symptoms remain the same. For example, while increased appetite and overeating may frequently occur in younger individuals, loss of appetite and weight are more common in late life. 20 Similarly, considering that sleep duration declines with age, decreased sleep is more common in LLD compared to hypersomnia, which is more typically experienced by younger depressed adults. 18 Fatigue is expressed both as physical tiring and lack of energy rather than a mental symptom, while the “poor concentration” symptom could be manifested more as a broader cognitive impairment where memory loss is related to executive dysfunction. 21 In general, older people manifest more vague and gastrointestinal somatic complaints, together with hypochondriasis. 22 Lastly, psychomotor retardation is more common in LLD than agitation, leading to disturbances in speech, facial expression, fine motor behavior, and gross locomotor activity, which exceed the general slowdown observed in normal aging. 23

It is therefore clear that one of the main challenges in recognizing the diagnostic features of geriatric depression is the overlap of its typical symptoms with those of other comorbid physical or neurologic conditions and, in general, with the typical signs of frailty (ie, weight loss, psychomotor slowing and exhaustion).

In fact, the somatic symptoms that in younger adults are indicative of depression, in the elderly may be correlated with aging and may not be indicative of a specific pathology, as well as could be due to other comorbid conditions. Thus, while including somatic symptoms in geriatric screening for depression regardless of their etiology (inclusive approach) may lead to false positives, 24 it remains true that they cannot be completely excluded from the diagnostic framework (as the exclusive approach, instead, proposes), as aging and its associated conditions do not necessarily justify all these aspects. An alternative is represented by the aetiological approach, in which somatic symptoms are considered only if they are not primarily due to another medical condition. 25 In general, a good clinical practice is to ask people about their mood when they refer to non-specific physical complaints, as to assess the presence of mood problems that older adults tend not to autonomously express, as previously stated.

Geriatric Depression Syndromes

Because of its peculiar features and complexity, different specific variants of geriatric depression have been proposed to better frame its presentations.

Among these, the “depletion syndrome”, 26 characterized by lack of interest, sleep difficulties, lack of hope, loss of appetite and thoughts of death, described the common condition of “depression without sadness” seen in older adults.

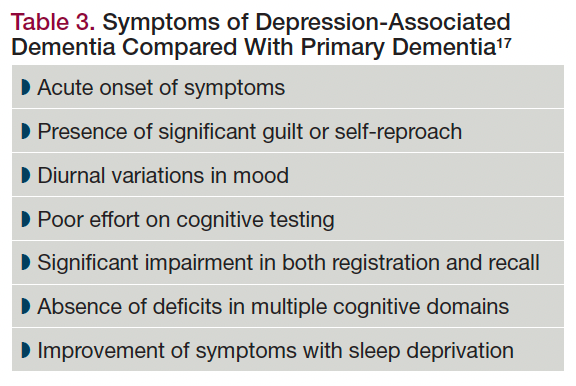

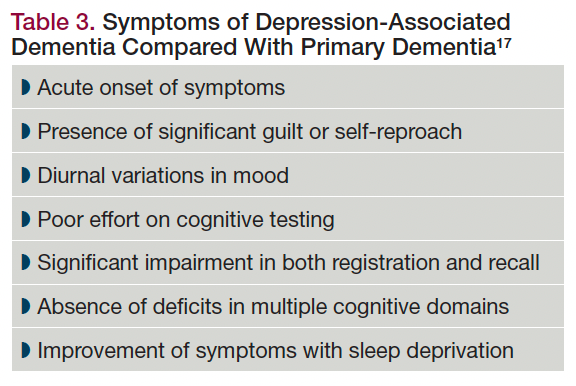

Another condition is referred to as “reversible dementia”. In some cases, in fact, older patients suffering from a severe depression development with marked cognitive impairment can induce the clinicians to misdiagnose dementia. 27 However, in these patients, the cognitive symptomatology recedes with the remission of depression, even if a part of them subsequently develops a proper dementia. 28 The label of “pseudodementia” this condition was addressed as, is no longer used, because of the complex relationship between depression and dementia, which represents an interaction between pathological processes, with more than one illness masquerading as another. 29

In fact, the complex entanglement involving aging-related processes, network dysfunction and depressive symptoms is also supported by the fact that two distinct syndromes regarding LOD can be recognized, ie the “depression-executive dysfunction syndrome” (DED) and vascular depression. DED 30 develops in patients whose fronto-striatal pathways are affected by aging-related or pathological changes. It is marked by psychomotor retardation, loss of interest, suspiciousness, lack of insight and pronounced disability, but rather mild vegetative symptoms and less prominent depressive ideation. 31 Moreover, individuals affected by this syndrome have impaired performance in tests of executive functioning (namely verbal fluency, response inhibition, problem solving, cognitive flexibility, working memory and ideomotor planning). 32 Vascular depression, instead, is characterized by psychomotor slowing, lack of initiative and apathy, and it is typically observed in patients with a medical history of hypertension and cognitive impairment. 31 The “vascular depression” hypothesis postulates that cerebrovascular disease may predispose, precipitate, or perpetuate some geriatric depressive disorders, 31 disrupting networks supporting affective and cognitive functions. 32

Risk and Protective Factors

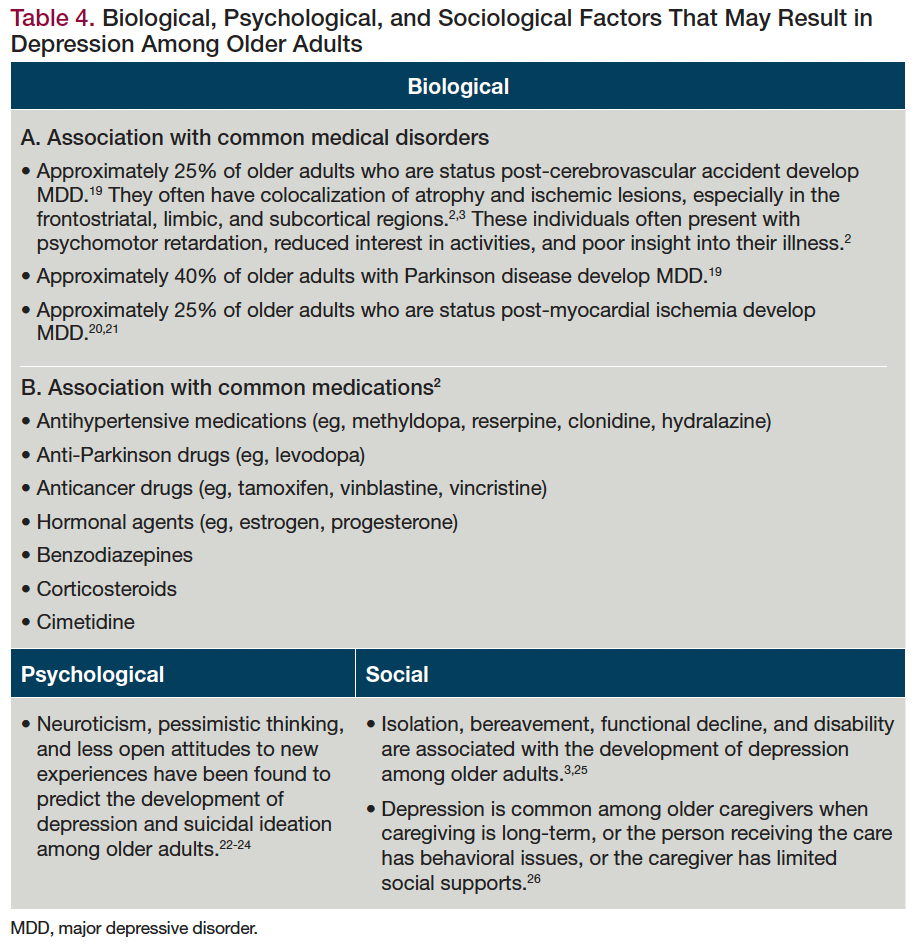

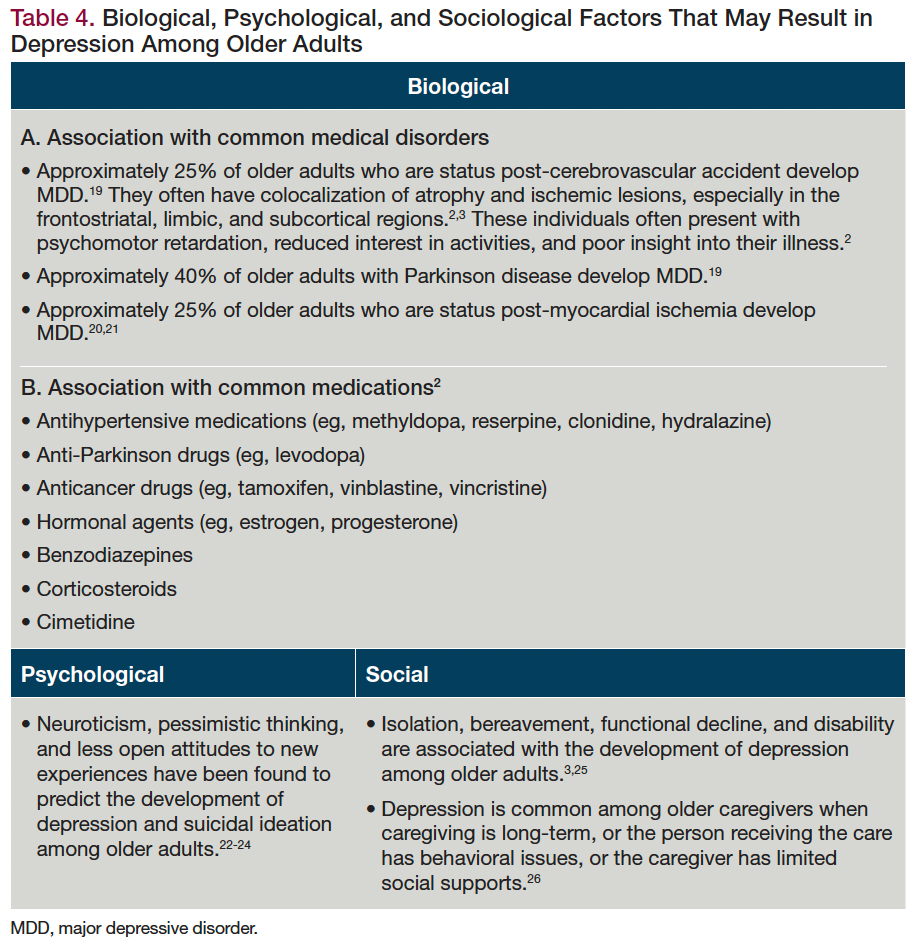

The identification of factors that can increase or protect from the risk of developing depression in the elderly population is crucial in order to promote prevention strategies, but also for the best comprehensive approach to this disease. The literature has shown that suffering from a chronic disorder 4 , 33–35 or cognitive impairment, 36 having a weak social, emotional and supportive network, 5 , 37 living isolated, taking care of relatives with chronic disease, 38 losing a partner, 39 can facilitate the rising of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, gender differences, well known in younger patients, persists also into late life, so being a woman can represent a risk factor. 40 On the other hand, having a high level of self-esteem, 41 resilience 42 and sense of control, 41 keeping a healthy lifestyle 43 and having a medium/high level of cognitive reserve 44 represent protective factors for the rising of depression in elderly age. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the main risk and protective factors involved in geriatric depression.

Risk and Protective Factors for Depression in Elderly

Recognizing Geriatric Depression in the Elderly: A Current Challenge

Depression in older adults is often under- or misdiagnosed and thus undertreated or inappropriately treated. Reasons for underdiagnosis are several and include psychosocial factors too. The first issue concerns the prejudice that depression is a normal phase of aging, because of the medical and situational conditions typical of older age, such as the limitations imposed by functional disability, health concerns and psychological stressors as decreasing social contacts, transitions in key social roles (ie, retirement) and grief. 15 Although, mood deflection is certainly understandable, it does not imply that it should be neglected, nor that it is not treatable, especially when it is a source of suffering and impairs functioning. Another barrier for depression recognition involves stigmatization. In fact, some individuals are reluctant to accept a diagnosis of depression, and often both patients and clinicians may hope to find a “medical illness” in order to avoid the stigma of a psychiatric diagnosis. 20 Moreover, older adults are less likely to express mood problems, like dysphoria or worthlessness, and may describe their symptoms in a more “somatic” way. 7 In general, older adults often find physical illness to be more acceptable than psychiatric illness. 45 At the same time, physicians may lack screening for depression because of more urgent physical problems or because they wrongly attribute depressive symptoms to comorbid medical illness. 46

In addition to underdiagnosis, another factor that contributes to undertreatment is misdiagnosis. As previously stated ( Table 1 ), in the elderly depression has an atypical presentation, including persistent complaints of pain, headache, fatigue, apathy, agitation, insomnia, weight loss, low attention and other nonspecific symptoms which can overlap with or be confused with other physical illnesses and dementia. This can lead clinicians to pursue an expensive medical workup, when they may not be able to recognize these problems as being part of a depressive episode. At the same time, older adults may relate their symptoms to a medical condition, thus not seeking the proper help. 18 Thus, it is necessary to gain insight on variability in the presentation of specific depressive symptoms across the lifespan.

Confounding Factors: Cognitive Impairment and Depression in Older Adults

Another specific challenge in the accurate diagnosis of depression concerns its entanglement with cognitive impairment and dementia. In fact, there is a substantial overlapping in the clinical presentation of late-life depression and early-stage dementia: a subjective perception of memory loss, as well as psychomotor retardation and a lack of motivation in answering at cognitive tests are typically observed in depressed older adults, and can be interpreted as signs of dementia. 47 Moreover, in older adults, depression is commonly accompanied by cognitive deficits, which are present in 20 to 50% of cases. 48 , 49 On the other hand, depressive symptoms are a common neuropsychiatric symptom of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). 50 Still, given the prevalence of both syndromes in the older population, they can also independently co-occur, and the two diagnoses are not mutually exclusive. 36

Geriatric depression is characterized by cognitive deficits involving executive functions, such as problem solving, planning, decision-making and inhibition, along with selective and sustained attention and working memory impairment. 51 Other deficits, involving some aspects of episodic memory and visuospatial functions, may be secondary to executive dysfunction. 28 These symptoms remain significant even after the remission of the depressive symptomatology. 52 In a 10-year longitudinal study, Ly et al 53 have shown that depressed older adults perform worse than compared healthy controls in cognitive tasks, maybe for the neurotoxic effects of depression and reduced cognitive reserve.

The relationship between late-life depression and cognitive decline is even more complex, considering that, besides mimicking each other, they also can coexist and be mutually a risk factor.

On the one hand, in fact, older adults with dementia can develop pure depressive symptoms. Clinical depression in these cases can be either reactive to the diagnosis or a relapse of a previously diagnosed depression. 54 Olin et al proposed diagnostic criteria for “depression of Alzheimer’s disease”, including the presence of at least three significant depressive symptoms during the same two-week period that represents a significant perturbation from previous functioning, when all the criteria of AD are fulfilled. 55

On the other hand, Ly et al 53 found that late-onset depression, but not EOD, was associated with a more rapid cognitive decline over time. These findings suggest that EOD, whose symptoms are persistent or recurrent in old age, is a vulnerability factor that alters cognitive abilities even in healthy aging, representing a risk factor for dementia. 21 On the contrary, LOD could be a real harbinger of dementia. In particular, highly educated people are more likely to show depressive symptoms as initial presentation of dementia, probably because cognitive reserve may delay the onset of cognitive, but not depressive, symptomatology. 56

Reviewing the Literature on Therapeutic Approaches to Depression in the Elderly

The effective management of geriatric depression builds upon different strategies, involving both pharmacological and non-pharmacological options that have to be considered based on the patient’s characteristics and psychosocial environment, in order to shape a tailored and comprehensive intervention. In fact, the most effective approach is the biopsychosocial one, combining pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy and an array of lifestyle and social environment’s personalized modifications. These therapies and good practices have shown to be effective, resulting in improved quality of life, enhanced functional capacity, possible improvement in medical health status, increased longevity, and lower health care costs. 14

Pharmacological Treatment of Depression in Older Adults

Late-life depression compared with that of younger patients shows a lower response rate to antidepressants, nonetheless several treatment options exist.

When prescribing drugs, including psychotropic drugs, to older adults’ attention should be paid to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes associated with aging. In fact, drug distribution varies, due to the increase in body fat that leads to an increasing distribution volume and elimination of half-life for lipophilic drugs. Renal filtration rate decrease enhances the problem of drug elimination. In addition, hepatic metabolism, besides being affected by aging, is also influenced by other concomitant drugs that induce or inhibit cytochrome P-450 metabolic enzymes.

In the choice of antidepressant treatment, the patient’s previous response to treatment should be considered, as well as his/her other comorbidities and medications, in order to minimize the risk of side effects and drug–drug interactions. In addition, somatic symptoms associated with depression like anxiety, psychotic symptoms, insomnia/hypersomnia, hyperphagia/poor nutrition should be considered.

The second-generation antidepressants, ie Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), are considered the first-line treatment options for depression in the elderly, because of their efficacy, 57 tolerability and safety profile. Except for paroxetine, they have lower anticholinergic effects than older antidepressants (ie tricyclics) and are thus well tolerated by patients with cognitive impairment or cardiovascular disease. SSRIs are also good for improving cognition, 58 while SNRIs are a good first choice in comorbid neuropathic pain. Most frequent SSRIs and SNRIs side effects include hyponatremia, 59 nausea and gastro-intestinal bleeding, 60 so periodic blood exams are recommended. Another second-generation antidepressant is mirtazapine that improves appetite being useful for anorexia, 61 and whose sedative side effect can be useful for insomnia. 62 A novel antidepressant, vortioxetine, a multimodal serotonin modulator, seems to be promising for elderly people since it also has a positive effect on cognition, independently of the improvement in depression. 63

When psychotic symptoms coexist, the addition of antipsychotics to antidepressants may be more effective than antipsychotics or antidepressants monotherapy, as reported by Meyers et al, 64 who found that the combination treatment of olanzapine plus sertraline was not only more effective than monotherapy but also equally tolerated.

Psychotherapy in Geriatric Depression

As for younger adults, also for older people psychotherapeutic approaches are to be encouraged, even in the presence of cognitive decline, since that treatment’s versatility gives the therapist the opportunity to adapt it to the patient’s needs and characteristics and to his/her physical and emotional environment.

In the following paragraphs a brief overview of the principal psychotherapy approaches available for older persons with depression is shortly provided.

Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH)

PATH is a home-delivered psychosocial intervention, which has shown to lead to significant positive results in elderly with depression, by providing help in emotional regulation. 65 , 66 This kind of therapy puts the focus on strategies personalized on each patient’s needs (ie memory and organizational deficits, behavioral/functional limitations, interpersonal tension, social isolation and anhedonia). 65 PATH looks to lessen the negative impact of emotions by improving pleasurable activities, using a problem-solving approach and integrating environmental adaptations and compensatory strategies, for instance using calendars, checklists and strategies to sustain or shift attention.

Engage Therapy

This stepped therapy targets behavioral domains grounded on neurobiological constructs using simple and efficient behavioral techniques. 31 The intervention aims at modulating patient’s response using the “reward exposure” strategy, working on three main behavioral domains, ie “negativity bias” (negative valence system dysfunction), “apathy” (arousal system dysfunction), and “emotional dysregulation” (cognitive control dysfunction), and add strategies targeting these domains.

Problem Solving Therapy (PST)

PST is an 8-week intervention that consists in a seven-step process to solve problems, including problem orientation that directs patient attention to one problem at a time, problem definition that helps patients select relevant information to determine what the root problem is, goal setting that focuses attention to the desired outcome, brainstorming that helps patients consider different ways for reaching the goal, decision-making, to evaluate the alternative solutions likelihood and picking the best choice, and action planning that involves a step-by-step plan for the patient to implement his/her solution. 67

Supportive Therapy

This home-delivered psychotherapy focuses on nonspecific therapeutic factors as facilitating expression of affect, conveying empathy, highlighting successful experiences, and imparting optimism. Supportive Therapy reduces depression and disability in older patients with major depression, cognitive impairment, and disability. 65

Interpersonal Therapy

Interpersonal Therapy is a psychodynamic therapy that focuses on complicated grief, role transition, role dispute/interpersonal conflicts, and interpersonal deficits. 68 During the first phase of treatment, therapists help patients to explore and understand depressive symptoms through a psychoeducational approach. In later phases, problems are identified and understood in the interpersonal context. In the final phase, the therapist focuses on the gains and limitations of therapy and the prevention of relapses. 68

Computerized Cognitive Remediation (CCR)

CCR has demonstrated improvements in mood and self-reported function in depressed patients similar to those obtained through the Problem Solving Therapy. 81 CCR is suitable for patients with an MMSE score of at least 24/30. 68 It makes use of a video game to treat depression (EVO), personalized, self-administered and continuously adapted to the patients’ aptitude both at baseline and progress in treatment. 67 Unlike Problem Solving Therapy, the EVO participants showed generalization to untrained measures of working memory and attention, as well as negativity bias. CCR is relatively inexpensive and can be used at the patients’ homes, thus minimizing barriers to access of care, common in older adults. 31

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

An effective treatment for depression in elderly population, available from mental health specialists, is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). 69 In ECT, an electrical stimulus is given for a brief period to produce a generalized seizure. The treatment is effective especially for psychotic depression, severe suicidality, treatment-refractory depression, catatonia, and depression with severe weight loss and anorexia, moreover, is indicated for older old (≥80 years). 70 A meta-analysis of the cognitive effects of ECT suggests its relative safety and the transient character of its effects on cognition. 71 Compared to antidepressants, ECT induces a higher speed of remission. 72

Practical Guidance for Depression Diagnosis and Treatment in the Elderly: A Pocket Guide for the Daily Clinical Management

If the proper recognition of geriatric depression remains at current challenge, the key aspects and main evidence presented here, along with a long interdisciplinary team clinical experience, lead to the identification of some guidelines to optimize the recognition and the adequate differential diagnosis of depression in the elderly. All the contents discussed below are summarized in the pocket guide, as a practical reference for a comprehensive diagnostic procedure in everyday clinical practice (see Figure 1 ).

Pocket guide for the assessment and management of geriatric depression in everyday clinical practice.

Clinicians should carefully consider depression among possible differential diagnosis, particularly when: patients refer to their attention with vague complaints as pain, fatigue and diffuse symptoms and/or suffer from anxiety or sleep disturbances; some clues are evident, such as poor personal hygiene, flat affect and slumped posture; the patient tends to frequently use healthcare resources, as calls or visits to practitioners. 46 , 48

In these cases, an accurate screening for the underlying risk factors and a collection of anamnestic data, which include medical, psychological and cognitive remote and recent history, is crucial to evaluate all potential contributing or protecting factors. Furthermore, to assess the individual’s protective factors (that mainly deal with aspects related to social network, hobbies, physical activity or personal interests) will also have a positive clinical implication in the management and treatment of depressive symptoms from a non-pharmacological point of view, by knowing the activities that could be pleasant and stimulating, as well as his or her personal resources.

Moreover, caregivers and families can be helpful, since they may provide information about the patient’s mood, behavior and general functioning. In fact, they could notice relevant changes that are not reported by the patient, especially if she or he has poor insight, as in the case of the co-occurrence of cognitive impairment.

When talking to patients, instead, it is important to adequate to the social and cultural background of older adults. As discussed in the previous sections, they are not used to deal with mental health issues and to verbally express concerns about their mood. Thus, the clinician should prefer to use expressions such as “Are you feeling low/down?” instead of directly asking “Are you depressed?” in order to address the stigma, and discuss mental health referral in the broader context of other medical conditions to increase the acceptability. 38 At the same time, all the healthcare professionals should promote the sensitization of the elderly to mood disorders and more generally to mental health, so that they can themselves become more attentive and aware in recognizing their emotional and psychological difficulties.

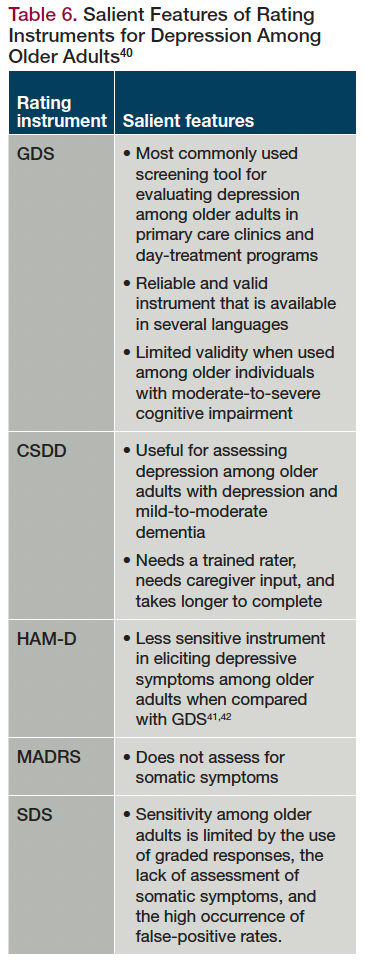

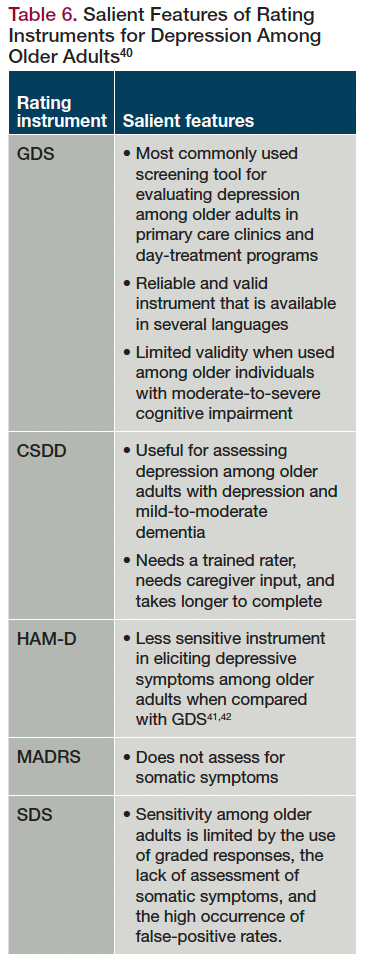

Clinicians can count on several validated tools to quantitatively assess the presence and severity of depression, namely self-report scales, clinician rating scales and structured interviews. Despite their popularity and their clear advantages, some considerations have to be taken into account when dealing with older adults. First of all, these tools were mostly developed for young adults, so they do not always catch the appropriate features for the elderly. 73 This also falls on their validity and reliability, which are strictly related to the population they are based on. 74 Self-reports are widely used because of their quickness and ease of administration. However, they are susceptible to some respondent’s characteristics, such as low educational attainment or cognitive impairment, which can influence the true comprehension of questions or of the response format. 75 In general, in the case of older adults with cognitive impairment, it is preferable to avoid self-reports and use alternative assessment methods that include direct observation and family reports. 7 Moreover, especially for patients with comorbidities, items with somatic content may need further clarifications, since somatic symptoms could be misattributed to depression. 76 Lastly, visual impairment can obstacle the completion of self-report scales: in these cases, the clinician can either propose an enlarged copy of the scale or administrate it orally. The use of clinician rating scales overcomes some of these issues, since they are based on the direct observation of a trained professional. If clinician rating scales offer a more accurate measurement of depression, it has been found that they are less sensitive in detecting changes in mild forms of depression. 77 Structured interviews offer the possibility to facilitate the comprehension of questions, as well as to deeper investigate aspects that need to be better clarified, as the nature of somatic symptoms; however, because of the time and skills requested for their administration, their utility is limited. 78 Overall, there is no single superior assessment method; rather, it is important that clinicians are aware of their strengths and shortcomings and informed about the psychometric properties of the main tools, so that they can choose the most appropriate instrument depending on the characteristics of the individuals. Moreover, using multiple methods and sources of information (ie, multidimensional assessment) has been shown to be the most effective approach. 78

When depressive symptoms are detected and a diagnosis of LLD is probable, among all the other factors, also the domestic and family context has to be looked at, that is, whether there are dynamics that can exacerbate the depressive symptomatology of the patient. This could be the case, for example, of a dysfunctional interaction in the patient-caregiver dyad or of some psycho-affective characteristics of the caregiver himself (for example, if he or her is depressed as well), likewise tensions in family relationships or other health or financial issue of relevant psychological impact.

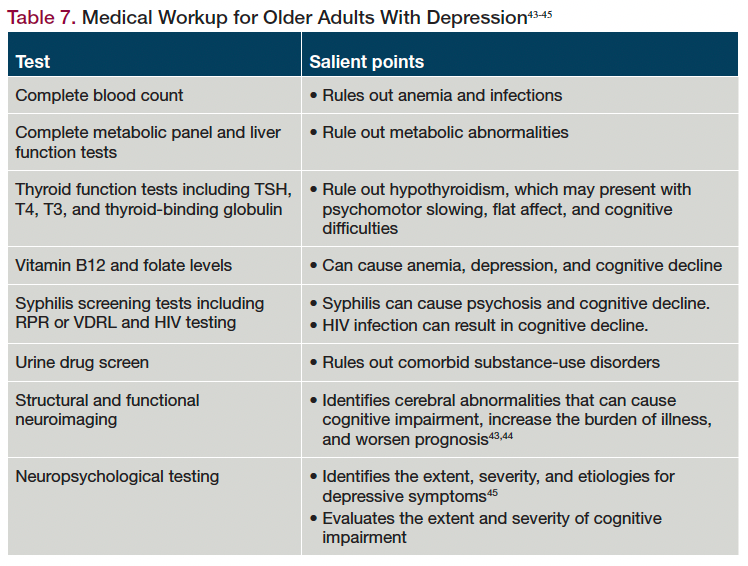

Lastly, it is important to exclude somatic causes of depression and to characterize a depressive episode or symptoms through patient history, clinical examination, laboratory tests, and/or imaging. In fact, LLD can per se be distinguished into a proper LOD or the recurrence of an EOD and, as stated, this has some clinical implications. Alternatively, depression can be secondary to a general medical condition or to a substance or medication use, considering that multimorbidity and polypharmacy are extremely common conditions among older adults. 79 Moreover, depressive symptoms could be the manifestation of a cerebrovascular disease or of a prodromal stage of AD, thus having a primarily organic origin. It is also important, in any case, to repeat when possible both the instrumental examinations (namely imaging techniques for the investigation of regional brain glucose metabolism, as FDG-PET) and the administration of cognitive and/or psychological screening tools in order to re-evaluate the overall diagnosis at a follow-up after 6–9 months. In fact, since LLD is a treatable and reversible condition, when a diagnosis of depression is made and a pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment has been proposed, there should be evidence of efficacy. Otherwise, the question arises if the depressive symptoms observed were secondary to another cause (so, the diagnosis was incorrect) or the therapeutic approach chosen was not the most suitable one.

Depression and Cognitive Impairment: How to Address Differential Diagnosis?

Whereas depressive and cognitive disorders often coexist in the elderly, it is crucial to distinguish a geriatric depression that includes cognitive deficits from a mild dementia with depressive symptoms. What needs to be determined from a clinical point of view, in particular, is whether or not the picture observed will evolve into dementia.

Time is a first important criterion: while in the case of dementia symptoms will develop with a slow progression over several years, depressive symptomatology onset can be dated with more precision and the progression of symptoms is more rapid. 48 , 80 Another relevant cue concerns awareness. Patients with reversible dementia complain more about their cognitive disturbances, highlighting their failures and disability and precisely describing the pattern of their deficits; older adults with dementia, on the contrary, usually lack insight and their description of cognitive loss is vague. 80

From a neuropsychological point of view, evidence has been described about a different characterization of cognitive profiles of patients with AD and depression that can be striking in the differential diagnosis.

First of all, patients with LLD show a prominent dysexecutive profile, with a slight impairment in global cognition. 21 Conversely, a broader cognitive impairment, with significant deficits of orientation, language, praxis and memory is typical of AD. 81 Secondly, although a memory disturbance is visible in both AD and LLD, they have a different functional origin. The episodic memory impairment of AD, due to hippocampal damage, is defined by a recall deficit that does not improve with cueing or recognition testing, since storage processes are primarily affected. 82 Depression, instead, leads to an insufficient allocation of attentional resources and executive dysfunction that affect encoding or retrieval strategies, 83 without a pure storage deficit. Thus, a differential diagnosis can be made with specific memory testing based on effective and specific encoding of information and retrieval facilitation with cueing. 82 Inefficacy of cueing and a flat learning curve despite exposure is typical of AD, while an improvement with exposure and a normal recall with retrieval cues are distinctive features of depression. 36

In general, patients with depression have a suboptimal cognitive performance due to poor motivation that leads them to give up the task more easily, not pay enough attention and use ineffective strategies, so their overall performance is more influenced by the cognitive load of the task and the extent to which it relies on executive functions. 83

In addition to all the steps that have to be gone through, and the factors that have to be taken into account for a comprehensive assessment that includes depression among the differential hypothesis, some general guidelines are here suggested about organizational aspects that can be implemented to improve the detection of depressive symptoms in the elderly.

First, given the predominance of somatic symptoms in late-life depression, as well as their tendency to focus more on their physical (rather than mental) issues, it is plausible that older adults who suffer from depression do not spontaneously refer to a mental health professional at first, but to other figures, such as general practitioners, physicians or other health professionals. For this reason, it would be important to improve the knowledge about late-life depression presentation, as well as the capacity to carry out screening activities, of specialists of other disciplines. In fact, although a formal diagnosis of depression is not part of their role, they could improve the detection of potential cases because of their position, as it is the case of occupational and physical therapists, nurses or general practitioners. 45

Furthermore, different professional figures, as psychiatrists, geriatricians, psychologists and neuropsychologists, often have to interface with older adults’ depressive symptoms in the presence of multimorbidity and/or cognitive deficits, and thus answer questions concerning the differential diagnosis of depression. It is of paramount importance for each specialist to evaluate individuals in their whole complexity. In this regard, a multidimensional assessment should always be provided, in order to take into account all the aspects discussed above, such as risk and protective factors, medical and psychological history, social context and recent life events. Moreover, when appropriate, specialists should choose a multidisciplinary approach, referring patients to other professionals that can have a role in the differential diagnosis or in identifying the most appropriate therapeutic option. When possible, it would be a valuable resource for figures with different and complementary competences to work together.

For example, in the specific case of older adults with depressive symptoms with a subjective perception or signs of cognitive impairment, geriatricians and neuropsychologists could manage outpatient visits and consultations in wards together, considering the tangled characteristics of LLD discussed above. In this way, these professional figures can provide a first screening of cognitive functioning and the characterization of some deficits that will help in the differential diagnosis between depression and dementia. Moreover, this synergy can help to consciously investigate the presence of a mood disorder and, where necessary, to offer to the patient a more accurate psychological and cognitive assessment, targeted medical investigations and therefore a tailored treatment.

In case older adults are aware of having a mood problem, they mainly refer to the psychiatrist. Notwithstanding the crucial role and competence of psychiatrists in this context, it is still important for them to consider older adults in their whole complexity. In this regard, they should provide a multidimensional assessment that takes into account all the aspects previously stated (ie, risk and protective factor, medical and psychological history, social context, recent life events…) and, when appropriate, have a multidisciplinary approach, referring patients to other professionals that can have a role in the differential diagnosis or in identifying the most appropriate therapeutic approach.

Another professional figure that frequently has to cope with the differential diagnosis of depression are geriatricians, since in their clinical practice they consult with patients who show signs or have a subjective perception of cognitive or neuropsychiatric problems. Both in outpatient visits and in consultations in wards, it could be a valuable resource for the geriatricians to be assisted by a neuropsychologist. For the characteristics of LLD discussed above, it would be beneficial for patients if the geriatrician and the psychologist/neuropsychologist could work together in the assessment of older adults, both for the outpatient visits and for the consultation inwards.

In this way, these professional figures can synergistically provide a first screening of cognitive functioning and the characterization of some deficits that will help in the differential diagnosis between depression and dementia. Moreover, it can help to consciously investigate the presence of a mood disorder and, where necessary, to offer the patient a more accurate psychological and cognitive assessment, targeted medical investigations and therefore a tailored treatment.

In conclusion, as a general indication, it is overall important to periodically screen older adults for depression. Furthermore, patients who already are in treatment for depression need to be periodically re-evaluated, since the persistence of a depressive symptomatology suggests that the therapeutic approach chosen (pharmacological or not) should be revised.

Conclusions

This review, beyond reviewing depression, its clinical main characterizations and current challenges had the goal to propose a few guidelines born from the “every-day” clinical activity carried-out on this population. A “pocket guide” has been produced in order to hopefully orient clinicians in their daily clinical management of depression and in sensitizing different professionals to a comprehensive, global and multidisciplinary assessment of a complex disorder affecting complex individuals such as the elderly are. Shortly, after a first multidimensional assessment, clinicians are provided with clinical cues orienting their diagnostic process. Whereas the diagnosis of depression is confirmed, by also excluding other co-occurrent/different pathologies (ie cognitive decline), a first- and second-line therapeutic approaches are suggested, including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological options. Lastly, follow-ups and periodic clinical assessments are strongly recommended to monitor individuals over time.

Finally, by considering not only the risk, but also the protective factors that may help people in facing depression along late life, this review also indirectly encourages clinicians in promoting active social, cognitive and psycho-affective lifestyles in the elderly, as crucial, modifiable factors that may significantly influence the natural course of their aging.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Depression and Aging

Depression is not a normal part of growing older.

Depression is a true and treatable medical condition, not a normal part of aging. However older adults are at an increased risk for experiencing depression. If you are concerned about a loved one, offer to go with him or her to see a health care provider to be diagnosed and treated.

Depression is not just having “the blues” or the emotions we feel when grieving the loss of a loved one. It is a true medical condition that is treatable, like diabetes or hypertension.

- How do I know if it's Depression?

- How is depression different for older adults?

- How many older adults are depressed?

- How do I find help?

- Additional Resources

How do I know if it’s Depression?

Someone who is depressed has feelings of sadness or anxiety that last for weeks at a time. He or she may also experience–

- Feelings of hopelessness and/or pessimism

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness and/or helplessness

- Irritability, restlessness

- Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable

- Fatigue and decreased energy

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering details and making decisions

- Insomnia, early–morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping

- Overeating or appetite loss

- Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts

- Persistent aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not get better, even with treatment

How is Depression Different for Older Adults?

- Older adults are at increased risk. We know that about 80% of older adults have at least one chronic health condition, and 50% have two or more. Depression is more common in people who also have other illnesses (such as heart disease or cancer) or whose function becomes limited.

- Older adults are often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Healthcare providers may mistake an older adult’s symptoms of depression as just a natural reaction to illness or the life changes that may occur as we age, and therefore not see the depression as something to be treated. Older adults themselves often share this belief and do not seek help because they don’t understand that they could feel better with appropriate treatment.

How Many Older Adults are Depressed?

The good news is that the majority of older adults are not depressed.

Some estimates of major depression in older people living in the community range from less than 1% to about 5% but rise to 13.5% in those who require home healthcare and to 11.5% in older hospitalized patients.

How do I Find Help?

Most older adults see an improvement in their symptoms when treated with antidepression drugs, psychotherapy, or a combination of both. If you are concerned about a loved one being depressed, offer to go with him or her to see a health care provider to be diagnosed and treated.

If you or someone you care about is in crisis, please seek help immediately.

Visit a nearby emergency department or your health care provider’s office

Call the toll-free, 24-hour hotline of the national suicide prevention lifeline at 988 to talk to a trained counselor.

- National Institute on Aging, Depression and Older Adults

- National Institute on Mental Health, Older Adults, and Depression

- PEARLS Toolkit (Program to Encourage Active, Rewarding Lives), CDC University of Washington Prevention Research Center [PDF – 588 KB]

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) Toolkit for Treatment of Depression in Older Adults

- Loneliness and Social Isolation in Older Adults

To receive email updates about Alzheimer's Disease and Healthy Aging, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Current Issue

- Upcoming Issue

- Guidance to Authors

- Editorial Executive Board

- Individual Details

- Become a Peer Reviewer

- Proof Readers

- Terms & Conditions

- Submit a Manuscript

- Manuscript Guidance

- Add Conference

- Add Job Advert

Depression in older adults

Claire Pocklington

Introduction

Depression is a clinical syndrome. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic classification systems describe three core symptoms of depression; low mood, anhedonia and reduced energy levels 1 . Other symptoms include impaired concentration, loss of confidence, suicidal ideation, disturbances in sleep and changes in appetite. Symptoms must have been present for at least a period of two weeks for a diagnosis of depression to be made. Major depression refers to the presence of all three core symptoms and, in accordance with ICD criteria, at least the presence of a further five other symptoms 1 . See Table 1 for severity criteria of a depressive episode according to ICD criteria.

Table 1: Severity criteria of a depressive episode according to ICD-10 1

Depressive symptoms, which can be clinically significant, can be present in the absence of a major depressive episode. Depressive symptoms are those that do not fulfil diagnostic criteria for a diagnosis of depression to be made. Depressive symptoms can be collectively referred to as sub-threshold depression, sub-syndromal depression or minor depression 2 .

It has been proposed that there are two types of depression; early-onset and late-onset depression. Late-onset depression refers to a new diagnosis in individuals aged 65 years of age or older. Over half of all cases of depression in older adults are newly arising (i.e. the individual has never experienced depression before) and thus late-onset type depression. Late-onset type depression is associated more with structural brain changes, vascular risk factors and cognitive deficits. It has been suggested that late-onset depression could be prodromal to dementia 3 .

The Kings Fund has estimated that by 2032 the proportion of older adults aged 65-84 years old will have increased by 39% whereas the proportion over the age of 85 years will have increased by 106% 4 . This increase in population will consequently see the incidence and prevalence of depression rise. By 2020 it is estimated that depression will be the second leading cause of disability in the world regardless of age 5 . Recognising, and so diagnosing, depression in older adults will become more important because of a greater demand on existing healthcare services and provisions, due to physical health consequences, impact upon healthcare utilisation and greater economic healthcare costs.

Presentation of depression in older adults

The presentation of depression in older adults is markedly different to that in younger adults. The most significant and fundamental difference in presentation in older adults is that depression can be present with the absence of an affect component, i.e. subjective feelings of low mood or sadness are not experienced 3,6-9 . The absence of an affective component is referred to as ‘depression without sadness’ 8-9 . It is common instead for older adults to report a lack of feeling or emotion when depressed 8-9 .

Anhedonia is also less prevalent in this population. However, reduced energy levels and fatigue are frequently reported 8-9 .

Compared to younger adults, psychological symptoms of depression occur more frequently and are more prevalent in older adults 10 . Such psychological symptoms include feelings of guilt, poor motivation, low interest levels, anxiety related symptoms and suicidal ideation. The presence of irritability and agitation are key features as well 7 . Hallucinations and delusions are also more common in older adults, particularly nihilistic delusions (i.e. a person believing their body is dead or a part of their body is not working properly or rotting).

Cognitive deficits are characteristic of depression in older adults 7,11 and are described as ‘substantial and disabling’ 12 . Such deficits mainly concern executive function 13-14 . Pseudodementia is a phenomenon seen in older adults 15 . The term refers to cognitive impairment secondary to a psychiatric condition, most commonly depression 16 . Pseudodementia has become synonymous with depression. Pseudodementia can be mistaken for an organic dementia and so older adults who are depressed can present primarily to mental health services with memory problems. Pseudodementia is classically associated with ‘don’t know’ answers, whereas older adults with a true dementia will often respond with incorrect answers 17 .

‘Depression-executive dysfunction syndrome’ is a more specific and descriptive term to describe the cognitive deficits found in older adults with depression 14 . It is associated with psychomotor retardation, which can be a core feature of depression in this population 7,14,18 . Psychomotor retardation describes a slowing of movement and mental activity 19 . Like pure cognitive deficits, psychomotor retardation contributes significantly to functional impairment 19 . Both executive dysfunction and psychomotor retardation have been found to be related to underlying structural changes in the frontal lobes 14, 20-21 . Psychomotor retardation is further related to white matter changes in the motor system, which leads to impaired motor planning 21 . There is conflicting evidence of whether the presence of psychomotor retardation is related to depression severity 18-19 .

Somatisation and hypochondriasis are associated with depression in older adults and increasing age in general 22-23 . Somatisation is often overlooked in older adults by healthcare professional who actively search to attribute such symptoms to a physical cause. Somatisation is more common in those who have physical comorbidities. Somatisation in older adults is associated with structural brain changes and cognitive deficits 24 .

Depression in older adults is associated with functional impairment cognitively, physically and socially 7,12,25 . Such functional impairment is linked to loss of independent function and increased rates of disability 26 . Withdrawal from normal social and leisure activities can be marked 7,25 . Social avoidance reduces interaction with others and is often a maintaining factor for depression 25 .

Self-neglect is a classical feature of depression 7 , with the presence of depressive symptoms in older adults being predictive of it 27 . Behavioural disturbances can be a common mode of presentation, especially for older adults living in institutionalised care 6-7 . Behavioural disturbances include incontinence, food refusal, screaming, falling and violence towards others 7 .

Diagnostic difficulties

Depression in older adults has been a condition that has constantly been under-recognised. Several issues account for this. Firstly, phenomenological differences are present. Many have argued that phenomenological issues contribute heavily to diagnostic difficulties 28 ; both the DSM and ICD classification systems do not have specific diagnostic criteria for depression in older adults. Potentially invalid diagnostic criteria for depression in older adults could result in fundamental difficulties in understanding, with consequent impact on both clinical practice and research.

Diagnostic difficulties are also encountered because depression in older adults can present with vague symptoms, which do not correspond to the classical triad of low mood, low energy levels and anhedonia, which can all be cardinal symptoms in a younger population. Reports of fatigue, poor sleep and reduced appetite can be attributed to a host of causes other than depression and therefore it is no surprise that a diagnosis of depression is overlooked and goes undetected by healthcare professionals 29 .

The absence of an affective component (i.e. low mood) can lead to healthcare professionals disregarding the potential for the presence of depression and consequently not exploring for other symptoms.

Furthermore, symptoms of depression, especially somatic ones, are often attributed to physical illnesses. Depressive somatic symptoms often lead to a diagnosis of depression being over looked; such symptoms ‘mask’ the clinical diagnosis of depression and hence the term ‘masked depression’ 30 . Depressive somatic symptoms – e.g. low energy levels, insomnia, poor appetite and weight loss - are often attributed to physical illness and/or frailty by both the individual and healthcare professional 7-8, 31 .

Further complicating diagnostic difficulties and under-recognition is the fact that older adults are less likely to report any symptoms associated with mental health problems and ask for help in the first place 7,10,32 ; explanations for this include older adults being less emotionally open, having a sense of being a burden or nuisance, and believing symptoms are a normal part of ageing or secondary to physical illness 7,10,29,33 .Older adults also have a reluctance to report mental health problems due to their perception of associated stigma; many older adults hold the view the mental health problems are shameful, represents personal failure and leads to a loss of autonomy 7 .

There is an overlap between symptoms of depression and symptoms of dementia. It is quite common for older adults with dementia to initially present with depressive symptoms. Depression has a high incidence in those with dementia, especially those with vascular dementia. Depression is particularly difficult to diagnose in dementia due to communication difficulties; diagnosis is often based on observed behaviours 8,33 .

Depression and comorbidity in older adults

In those with pre-existing physical health problems, depression is associated with deterioration, impaired recovery and overall worse outcomes 34 . For example, the relative risk of increased morbidity related to coronary heart disease is 3.3 in comparison to individuals without depression 35 . Mykletun et al. established that a diagnosis of depression in older adults increased mortality by 70% 36 . Several causative routes account for poor physical illness outcomes. Older adults with depression are less likely to report worsening health. Depressive symptomatology indirectly affects physical illness through reduced motivation (often secondary to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness) and engagement with management. Poor compliance with management advice, notably adherence to medications is observed 37 . Feelings of hopelessness, helplessness and negativity will contribute to the failure to seek medical attention in the first place or report worsening health when seen by a healthcare professional.

Depression affects biological pathways directly, which impairs physical recovery. Such biological effects include pro-inflammatory factors, metabolic factors, impact upon the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and autonomic nervous system changes 38 .

Older adults who are depressed are more likely to have existing physical health conditions and more likely to develop physical health conditions 15 . Depression is particularly associated with specific physical illnesses; cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. A study by Win et al . found that cardiovascular mortality is higher in older adults with depression because of physical inactivity; the study established that physical inactivity was accountable for a 25% increased risk in cardiovascular disease 39 . The relationships between depression and cardiovascular disease and depression and diabetes have been described as “bidirectional” 38 .

Higher incidents of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus are seen in people with depression regardless of age. A study by Brown et al. found that older adults with depression had a 1.46 relative risk increase for developing coronary heart disease compared to those without depression 40 . The hypothalamic-pituitary axis dysfunction found in depression leads to increased levels of cortisol, which in turn, increases visceral fat. Increased visceral fat is associated with increased insulin resistance, promoting diabetes mellitus, and increased cardiovascular pathology 38 .

Depression is a risk factor for the subsequent development of dementia; this is especially so if an older adult has no previous history of depression (i.e. depression is late-onset) 13 .

Healthcare utilisation and economic impacts

Older adults are less likely to report depressive symptoms to healthcare professionals explaining the under-utilisation of mental health services for depression 32,41 . Despite older adults under-utilising mental health services they over utilise other healthcare services 26,41 . For example, those presenting with non-specific medical complaints or somatisation have been found to have an increase use of healthcare services. Non-specific medical complaints and somatisation lead to an unnecessary use of resources, such as unnecessary consultations with healthcare professionals and investigations 41 . Increase in service utilisation means an increase in the associated economic cost of depression in older adults 41-43 .

Healthcare costs of older adults with a comorbid physical illness and depression are far greater than those without depression – findings in diabetes mellitus are a good example 43 . The majority of the increased healthcare costs are associated with the chronic physical disease and not the care and treatment of the depression 44 . Poor compliance with physical illness management is associated with missed appointments and a greater number of hospital admissions, which both have financial implications.

Aetiology and associations of depression in older adults

Late-onset type depression in older adults has been associated with the term ‘vascular depression’ 45-47 . Studies have found a significant higher rate and severity of white matter hyperintensities on MRI imaging in older adults with depression compared to those without depression 46,48,50 . White matter hyperintensities represent damage to the nerve cells; such damage is a result of hypo-perfusion of the cells secondary to small blood vessel damage 49 . White hyperintensities are associated with vascular risk factors (e.g. age, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking) and are linked to cerebrovascular disease, such as stroke, vascular dementia. A relationship has been found between psychosocial stress and consequent development of vascular risk factors, which further supports the hypothesis of ‘vascular depression’ 46 . Clinically, ‘depression-executive dysfunction syndrome’ and psychomotor retardation are associated with vascular changes 48 .

In older adults with depression, white matter hyperintensities are associated with structural changes to corticostriatal circuits and subsequent executive functional deficits. Loss of motivation or interest and cognitive impairment in depression are hallmark features of structural brain changes associated with the frontal lobes, which in turn are associated with a vascular pathology 20 . A study by Hickie et al. established that white matter hyperintensities in older adults with depression are associated with greater neurological impairment and poorer response to antidepressant treatment 50 . It is not fully understood why vascular depression responds less well to antidepressants; poor response has been linked directly to vascular factors but has also been associated with deficits in executive function 46-47 .

The relationship between cerebrovascular disease and depression is described as ‘bi-directional’ 45,51 ; depression has been found to cause cardiovascular disease and vice versa 51 . Baldwin et al. direct the reader to the presence of post-stroke depression and the occurrence of depression in vascular dementia 45 .

Younger and older adults share a number of fundamental risk factors for depression; such as female gender, personal history and family history 7 . Older adults have additional risk factors related to ageing, which are not just physiological in nature.

Age related changes:

Age related changes occurring in the endocrine, cardiovascular, neurological, inflammatory and immune systems have been directly linked to depression in older adults 3 .

The normal ageing process sees changes to sleep architecture and circadian rhythms with resultant changes to sleep patterns 52 . Thus sleep disturbances are common in older adults and positively correlated to advancing age 52 ; over a quarter of adults over the age of 80 years report insomnia, and research has well-established that this is a risk factor for depression 53-54 . A meta-analysis by Cole et al . found sleep disturbances to be a significant risk factor for the development of depression in older adults 53 .

Sensory impairment:

Sensory impairments, whether secondary to the ageing or a disease process, are risk factors 53,55 . Research has found that hearing and vision impairments are linked to depression 56 . A sensory impairment can lead to social isolation and withdrawal, which, in turn, are further risk factors for depression.

Physical illness:

Physical illness, regardless of age, is a risk factor for depression. Older adults are more likely to have physical illnesses and so in turn are more at risk of depression. See Table 2. Physical illness is associated with sensory impairments, reduced mobility, impairment in activities of daily living and impaired social function, all of which can lead to depression. Physical illnesses associated with chronicity, pain and disability pose the greatest risk for the subsequent development of depression 7,53,55 . Physical illness affecting particular systems of the body, such as the cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and neurological, are more likely to cause depression 3 . Essentially, however, any serious or chronic illness can lead to the development of depression. It should be noted that a large proportion of older adults have physical illness but do not experience depression symptoms, therefore other factors must be at play 5,57 .

Treatments of physical illness are directly linked to aetiology in depression, for example, certain medications are known to cause depression; cardiovascular drugs (e.g. Propranolol, thiazide diuretics), anti-Parkinson drugs (e.g. levodopa), anti-inflammatories (e.g. NSAIDs), antibiotics (e.g. Penicillin, Nitrofurantoin), stimulants (e.g. caffeine, cocaine, amphetamines), antipsychotics (e.g. Haloperidol), anti-anxiolytics (e.g. benzodiazepines), hormones (e.g. corticosteroids), and anticonvulsants (e.g. Phenytoin, Carbamazepine) 7,29 . Polypharmacy is present in many older adults further increasing the risk of depression. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic age related changes also contribute to an increased risk of medication induced depression in older adults.

Table 2: Table of physical illnesses associated with depression 3,7

Dementia is common in old age and those with dementia are at higher risk of developing depression compared to those who do not have it 58 . 20-30% of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease have depression 59 . Depression is a risk factor for the subsequent onset of dementia.

Psychosocial:

When compared to younger adults, older adults are at a greater risk of developing depression due to the increased likelihood of experiencing particular psychosocial stressors, in particular adverse life events. Stressors include lack of social support, social isolation, loneliness and financial hardship. Financial hardship and functional impairment often sees older adults downsizing in property. Deteriorating physical health often sees older adults no longer being able to manage living independently at home necessitating a move into institutional living. Bereavement, especially spousal, and the associated role change that follows this are risk factors for depression 3 .

Sub-threshold depression:

Sub-threshold depression is an established risk factor for major depression.

Prevalence and epidemiology

The prevalence of depression in older adults in England and Wales was found to be 8.7% in 2007; however, if those with dementia are included this figure rises to 9.7% 60 . A meta-analysis by Luppa et al. established a 7.2% point prevalence of major depression and a 17.1% point prevalence of depressive disorder in older adults 61 . The projected lifetime risk of an older adult developing major depression by the age of 75 years old is 23% 62 .

Sub-threshold depression is 2-3 times more prevalent than major depression in older adults 26,63 . These depressive symptoms are often clinically relevant 26,29 . 8-10% of older adults per year with sub-threshold depressive symptoms go onto develop a major depressive episode 63 .

Incidence and prevalence are greater in women; 10.4% of women over the age of 65 years have depression compared to 6.5% of men 60 . Older women are more likely to experience recurrent episodes of depression compared to older men 62 . The gender gap in incidence and prevalence becomes narrower with increasing age 3 . It should be acknowledged however that women are more likely to present to healthcare services and seek help in comparison to men 64-65 .

The prevalence of major depression in older adults varies by setting 66 . Highest rates are seen in long-term institutional care and inpatient hospital settings 67 . Table 3 summaries prevalence rates of major depression by setting.

Table 3: Prevalence rate of major depression by setting 7, 67

Prognosis of depression in older adults

Depression in older adults is associated with a slower rate of recovery 9 , worse clinical outcomes compared to younger adults 3 and is associated with higher relapse rates 68 . Worse prognosis in older adults correlates with advancing age, physical comorbidities and functional impairment 70 . The structural brain changes associated with depression in older adults are linked, as discussed, to poorer treatment response.

Morbidity and mortality associated with depression can be described as primary or secondary; primary morbidity and mortality arises directly from the depressive illness; whereas secondary morbidity and mortality arises from physical health problems, which are secondary to depression.

Outcomes from sub-threshold depression are on par with those of major depression; however sub-threshold depression which develops into major depression is associated with worse outcomes 2 .

Proportionally more people over the age of 65 years commit suicide compared to younger people 71 . Depression is the leading cause of suicide in older adults 29,71 ; one study reports that 75% of older adults who killed themselves were depressed 72 .

The vast majority of older adults who commit suicide have had contact with a health professional within the preceding month 9 ; this figure has been quoted as high as 70% 3 . This further supports and suggests the fact the depression is under-detected. Unlike younger adults, older adults are less likely to report suicidal ideation and can experience suicidal ideation without feeling low in mood 3,7 . Older adults have few suicide attempts, compared to younger adults, because their suicide methods are more lethal 13 .

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2001a. The World Health Report. Mental Health: New understanding, new hope., WHO.

- Cherubini, A., Nistico, G., Rozzini, R., Liperoti, R., Di Bari, M., Zampi, E., Ferrannini, L., Aguglia, E., Pani, L and Bernabei, R. 2012. Subthreshold depression in older subjects: An unmet therapeutic need. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 16 , 909-913.

- Fiske, A., Wetherell, J. L. & Gatz, M. 2009. Depression in older adults. Annual review of clinical psychology, 5 , 363-389.

- The Kings Fund. 2014. Ageing Population [Online]. Available: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/time-to-think-differently/trends/demography/ageing-population [Accessed October 1st 2014].

- Mathers, C. D. & Loncar, D. 2006. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS medicine, 3 , e442.

- Evans, M. 1995. Detection and management of depression in the elderly physically ill patient. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 10 , S235-S241.

- Evans, M. & Mottram, P. 2000. Diagnosis of depression in elderly patients. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 6 , 49-56.

- Alexopoulos, G. S. 2005. Depression in the elderly. The Lancet, 365 , 1961-1970.

- Arean, P. A. & Ayalon, L. 2005. Assessment and treatment of depressed older adults in primary care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12 , 321-335.

- Mitchell, A. J., Rao, S. & Vaze, A. 2010. Do primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late-life depression? A meta-analysis stratified by age. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 79 , 285-94.

- Butters, M. A., Mulsant, B. H., Houck, P. R., Dew, M. A., Nebes, R. D., Reynolds, C. F., Bhalla, R. K., Mazumdar, S., Begley, A. E., Pollock, B. G & Becker, J. T. 2004. Executive Functioning, Illness Course, and Relapse/Recurrence in Continuation and Maintenance Treatment of Late-life Depression: Is There a Relationship? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12 , 387-394.

- Butters, M., A, Whyte, E. M., Nebes, R. D., Bebley, A. E., Dew, M. A., Mulsant, B. H., Zmuda, M. D., Bhalla, R., Meltzer, C. C. & Pollock, B. G. 2004. The Nature and Determinants of Neuropsychological Functioning in Late-LifeDepression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61 , 587-595.

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Meyers, B. S., Young, R. C., Kalayam, B., Kakuma, T., Gabrille, M., Sirey, J. A. & Hull, J. 2000. Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57 , 285-290.

- Lockwood, K., A., Alexopoulos, G. S., Kakuma, T. & Van Gorp, W. G. 2000. Subtypes of cognitive impairment in depressed older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 8 , 201-208.

- Chapman, D. P & Perry, G. S. 2008. Depression as a major component of public health for older adults. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, 7.

- Kang, H., Zhao, F., You, L., Giorgetta, C., Venkatesh, D., Sarkhel, S. & Prakash, R. 2014. Pseudo-dementia: A neuropsychological review. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 17 , 147-154.

- Bieliauskas, L. A. & Drag, L. 2013. Differential Diagnosis of Depression and Dementia, New York, Springer.

- Beheydt, L., Schrijvers, D., Docx, L., Bouckart, F., Hulstijn, W. & Sabbe, B. 2014. Psychomotor retardation in elderly untreated depressed patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5 , 196.

- Bennabi, D., Vandel, P., Papaxanthis, C., Pozzo, T. & Haffen, E. 2013. Psychomotor retardation in depression: a systematic review of diagnostic, pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. BioMed Research International.

- Rapp, M. A., Dahlman, K., Sano, M., Grossman, H. T., Haroutunian, V. & Gorman, J. M. 2005. Neuropsychological differences between late-onset and recurrent geriatric major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162 , 691-698.

- Walthers, S., Hofle, O., Federspiel, A., Horn, H., Hugli, S., Wiest, R., Strik, W. & Muller, T. J. 2012. Neural correlates of disbalanced motor control in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136 , 124-133.

- El-Gabalawy, R., Mackenzie, C., Thibodeau, M., Asmundson, G. & Sareen, J. 2013. Health anxiety disorders in older adults: conceptualizing complex conditions in late life. Clinical Psychology Review, 33 , 1096-1105.

- Shahpesandy, H. 2005. Different manifestation of depressive disorder in the elderly. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 26 , 691-5.

- Inamura, K., Tsuno., N., Shinagawa, S., Nagata, K & Nakayaman, K. 2015. Correlation between cognition and symptomatic severity in patients with late-life somatoform disorders. Aging and Mental Health, 19 , 169-174.

- Polenick, C. A. 2013. Behavioral activation for depression in older adults: theoretical and practical considerations. Association for Behavioral Analysis International, 36 , 35-55.

- Rinaldi, P., Mecocci, P., Benedetti, C., Ercolani, S., Bregnocchi, M., Menculini, G., Catani, M., Senin, U & Cherubini, A. 2003. Validation of the Five‐Item Geriatric Depression Scale in Elderly Subjects in Three Different Settings. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51 , 694-698.

- Abraams, R. C., Lachs, M., Mcavay, G., Keohane, D. J., Bruce, M. L. 2002. Predictors of self-neglect in community-dwellings elders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159 , 1724-30.

- Prakash, O., Gupta, L. N., Singh, V. B & Nagarajarao, G. 2009. Applicability of 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale to detect depression in elderly medical outpatients. Asian journal of psychiatry, 2 , 63-65.

- Birrer, R. B. & Vemuri, S. P. 2004. Depression in later life: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. American Family Physician, 69.

- Small, G. W. 1991. Recognition and treatment of depression in the elderly. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 52, 11-22.

- Friedman, B., Conwell, Y., Delavan, R. R., Wamsley, B. R & Eggert, G. M. 2005. Depression and suicidal behaviors in Medicare primary care patients under age 65. Journal of general internal medicine, 20 , 397-403.

- Crabb, R. & Hunsley, J. 2006. Utilization of mental health care services among older adults with depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62 , 299-312.

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Kiosses, D. N., Heo, M., Murphy, C. F., Shanmugham, B. & Gunning-Dixon, F.2005. Executive dysfunction and the course of geriatric depression. Biological Psychiatry, 58 , 204-10.

- Aroma, A., Raitasalo, A., Reunanen, O., Impivaara, M., Heliovaara, P. & Knekt, P. 1994. Depression and cardiovascular diseases. Acta Psychiatr Scand. Supple, 377, 77-82.

- Mykletun, A., Bjerkeset, O. & Overland, S. 2009. Levels of anxiety and depression as predictors of mortality: the HUNT study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 195: 118-125.

- Evans, M., Hammond, M., Wilson, K., Lye, M. & Copeland, J. 1997. Treatment of depression in the elderly: effect of physical illness on response. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12 , 1189-94.

- Katon, W. J. 2011. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13 , 7-23.