Abroadship.org

Centre of learning through mobility.

- Youth Exchanges

- Training Courses

- Online courses

- Scholarships & Grants

- Study Visit

- Internships & Apprenticeships

- Conferences & Seminars

- Gravity Jam – 1 DAY programme

- English Teaching Internship in India

- Montessori Teaching Internship in India

- Sports Coaching Internship in India

- Music, Arts & Crafts Teaching Internship in India

- Visa to India

- São Vicente

- Volunteering & Other opportunities

- National Agencies for Erasmus Plus Programme

- Erasmus+ Youth in Action Programme countries

- Erasmus+ Youthpass

- What is Erasmus+ Youth Exchange?

- European Health Insurance Card

- Young people with fewer opportunities

- Journal of Self-Branding – Media Creator – London

- Journal of Self-Branding – Media Creator 3 – London

- Offer Your Opportunity

- Video presentation of Abroadship

- Stories of Abroadship projects

- Abroadship Volunteers

- Marketing Offer

Training Course: Look up! Critical thinking in and about youth work – Iceland

Training Course: Look up! Critical thinking in and about youth work-Iceland

Óli Örn Atlason

E-Mail: [email protected]

Phone: +354 5155847

Participation fee

This project is financed by the participating National Agencies (NAs) of the Erasmus+ Youth in Action Programme. The participation fee varies from country to country. Please contact your National Agency or SALTO Resource Centre (SALTO) to learn more about the participation fee for participants from your country.

Accommodation and food

Unless specified otherwise, the hosting NA or SALTO of this offer will organise the accommodation and covers the costs for accommodation and food.

Travel reimbursement

Please contact your NA or SALTO in order to know whether they would support your travel costs. If yes, after being selected, get in touch with your NA or SALTO again to learn more about the overall procedure to arrange the booking of your travel tickets and the reimbursement of your travel expenses.

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing .”—Albert Einstein

In this complex and fast changing world, the new generation of youth workers must adapt as quickly as their environment is changing.

In the reality of climate change, difficult economic situations, fake news, radicalisation, and wars, it is essential to equip both youth workers and young people with the tools of critical thinking. Critical thinking enables us to reflect about, understand and question our own assumptions and beliefs as well as influence on and from organisations and society. In order to understand oneself and the world better, orient oneself in increasing complexity and create more peaceful relations, critical thinking is an essential tool of every youth worker and people connected to youth work.

Increased critical thinking in and about youth work allows youth workers to explore the concept of critical thinking from a personal point of view as well as an organisational point of view. The training is meant to facilitate the growth of critical thinking for youth workers and give them tools to multiply that knowledge with the youth they work with. At the same time it is important to think critically about the organisations or informal groups that youth workers work with and contemplate how the work can be ameliorated.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the training course is to support youth workers and youth leaders to facilitate critical thinking processes with young people by providing tools and methods for them and exploring the concept on personal, organisational and societal levels.

The objectives of the training are to:

develop a common understanding of critical thinking as a concept and as a tool in relation to youth work

improve participants’ critical thinking skills

learn how to facilitate critical thinking learning situations among young people through youth work

explore and share methods, tools, resources and best practices related to critical thinking

Learning outcomes

At the end of the training participants will:

leave with concrete tools and competences which can be used to facilitate young people’s critical thinking processes

be better equipped to critically analyse their environment at a personal, interpersonal, and societal level

enrich their own critical thinking toolbox

have confidence to implement critical thinking in a team working context

Participants’ profile

Participants at the training should be:

- youth workers, youth leaders and volunteers working with young people

- interested in the topic

- willing to share their own experiences and actively participate in the learning process

- committed to share their learnings and skills with young people after the training

- comfortable with English as a working language

- able and curious to keep learning after the training

Methodology

The methodologies will all be based on non-formal education, with the aim of creating an inclusive space for the participants to explore, learn and grow. They will be fitted to the participants attending the training course and will include the following domains:

- facilitated experiences within the group (e.g. role plays, games or outdoor activities)

- self-reflection (individually, in pairs or in the group)

- exploration of theories and concepts to contextualise experiential knowledge

- experimentation with the gained insights

Available downloads:

- Draft Agenda Look Up! – Schedule or the call.pdf

Abroadship is a centre for learning through mobility.

27 November 2022

Training Course

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent posts.

- Story – Inclusion Through Arts – South America

- Training Course: Mentors Training (II):Training series on Volunteer Management & Mentoring (Making Magic in the Kingdom of Volunteering) – Germany

- Training Course: Colourful Hands – Spain

- Training Course: TICTAC Training Course & Partnership Building Activity – Austria

- Training Course: Let’s vote – Slovenia

- Training Course: European Solidarity Corps: TOSCA – training and support for organisations active in the volunteering actions in the European Solidarity Corps – Slovakia

- Training Course: Sexual Health, Sexual Identity and Positive Relationships – Ireland

Subscribe to receive first hand!

Latest opportunities.

About Abroasdship.org

Our desire and mission is to encourage you to become world’s citizen with tolerance, sympathy and empathy towards different cultures, with understanding and appreciation of environment, with knowledge of interdependence, connection and benefits of collaboration.

We strive to create tools, provide information, organize events, training courses, exchange programs and in all ways possible enhance benefiting from being abroad. We want you to be more abroad-intelligent.

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

© 2024 Abroadship.org

Subscribe To Receive Opportunities Abroad

Why to waist precious time hunting for opportunities, if they can come straight to your doorstep?

No, Thank You

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Colour mode

Other settings

Accessibility statement

- Resource Pool Dive into our selection of online resources

- Resource map Explore Youth Participation in Europe

- European training calendar Find your next opportunity to learn and grow

- Glossary Everything there is to know about participation from A to Z

- Get Involved Ready to change the world? Here we go

- Flagship Projects Collection

Critical Thinking and Media Literacy in Youth Work

13 July 2021

The author of the cover picture is Margaret Pütsepp, a young Estonian artist

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Copy URL to clipboard

We live in the ‘information age, and our young people are surrounded by information coming from all sorts of directions and wrapped in all types of packaging. Every day a young person spends more than a third of their free time consuming, interacting with, and producing media – an important sign when it comes to thinking about what young people’s priorities are today. At this stage in life, their minds demand maximum social interaction – a phycological requirement of young age .

It is the time when people tend to have the greatest number of friends and close connections. It is the time of transition from high school to college, which brings with it a dramatic expansion of social circles. It is also the time when people are at their most vulnerable – seeking attention, acceptance, and approval of thoughts and actions. The search for where we belong is a process that can lead to very wrong places. Often unable to deal with their own feelings, young people have an even harder time when exposed to hate speech , mocking, cyberbullying , and radical/extremist content. Therefore, it is very important that young people have certain skills and techniques to understand that what they are seeing is not necessarily what they should believe in and that they need to be a little more disciplined in sorting out the information they receive and what they take from it.

Two of those skills are critical thinking and media literacy – and the two are very closely intertwined. Let’s look at what each of them is, how they can impact young people’s lives, and how youth workers can help develop these skills inside and outside the classroom.

Critical thinking in perceiving media

So, once critical thinking was established as “an ability to examine and analyze information and ideas in order to understand and assess their values and assumptions, rather than simply taking propositions at face value” (UNESCO, 2013), how would you say it connects to our understanding of media today? There is more than one direct answer. In fact, there are five ways we can look at it, according to the NW Center for Excellence in Media Literacy (College of Education, University of Washington):

- All media are carefully wrapped packages As carefully wrapped packages, the messages are ‘wrapped’ with enormous effort and expense, even though they appear quite natural to the audience. Media texts are the product of careful manipulation of constructive elements, both on an obvious and a subtle level. On an obvious level, constructions such as drawings, colours, and headlines may be used. But on a subtle level, constructions such as appeals (generalization appeal or appeal to emotion) may be used. Young people need to develop the skills of looking beneath the surface of media messages to see how they are constructed.

- Media construct versions of reality Audiences tend to accept media texts as natural versions of events and ideas when, in fact, they are only representations of events and ideas. The reality we see in media texts is a constructed reality built for us by the people who made the media text. Young people need to develop skills in interpreting texts so that they can tell the difference between reality and textual versions of reality.

- Media are interpreted through individual lenses Audiences interact with media texts in their own individual ways. Some audiences accept some messages totally at face value. Other audiences may reject the same text, disagree with its message , or find it objectionable. Yet other audiences, not certain if they have embraced or rejected the text, will try to come to terms with it by negotiating. Audiences who negotiate with a text might ask questions, seek out other people’s opinions or try several interpretations or reactions the same way we try on new clothes—to see how they suit us. Young people need to be open to multiple interpretations of texts and aware that a reaction to a text is a product of both the text itself and all that the audience brings to the text in terms of their accumulated life experience.

- Media are about money Modern media are expensive to produce. Producers need to make back their investment by marketing their products to audiences. One of the main purposes of the media is to promote consumerism. While we enjoy many of the products of media, such as magazines, we need to be aware that some media texts are created to deliver an audience to advertisers rather than to deliver texts to audiences. Others may use consumerism as a secondary motive. With increasing regularity, four or five massive communications conglomerates dominate media production facilities such as newspaper/book/magazine publishers and TV/film production and distribution companies. Young people need to be aware of the implications of media’s commercial agenda and how ‘convergence’ affects media and their content.

- Media promote agenda The very fact that some people object to some media texts is proof that those texts contain value messages . Most media texts are targeted to an audience that can be identified by their values or ideology (belief system). Detecting the ideological and values agenda of media texts is an important skill in media analysis.

Looking at the five ideas described above, one can be quite perplexed at how difficult it may be for a young person to grasp these concepts and find their own way to deal with the challenges they present. Therefore, the skill that comes to the fore is media literacy, or rather media and information literacy, as the experts explain today ( UNESCO, p.27 ).

Defining Media and Information Literacy

“We live in a world of almost total mediation,” states renowned British writer and media education researcher David Buckingham (2018). “New challenges have emerged, for example, in relation to fake news , online abuse, and threats to privacy, while older concerns – for example, about propaganda, pornography, and media’ addiction’ – have taken on new forms. The global media environment is now dominated by a very small number of near-monopoly providers, like Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, who control the most widely used media platforms and services, and yet whose power is much less overt and visible than the power of older ‘mass media’ corporations. We all need to think critically about how media work, how they represent the world and how they are produced and used”.

In the scope of today’s technology-saturated reality, media literacy, as the concept with roots in media and civic studies, is not sufficient. Being contributors to the information exchange via media, we cannot overstate the importance of the missing part – information literacy, as access to information, the evaluation, creation, and sharing of information and knowledge, using various tools, formats, and channels. Therefore, it is important to emphasize the term Media and Information Literacy (MIL), defined as “a set of competencies that empowers citizens to access, retrieve, understand, evaluate and use, to create as well as share information and media content in all formats, using various tools, in a critical, ethical and effective way, in order to participate and engage in personal, professional and societal activities” ( UNESCO ).

The ultimate goal of MIL is to empower people to exercise their universal rights and fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of opinion and expression, and to use the opportunities available in the most effective, inclusive, ethical, and efficient manner for the benefit of all individuals.

MIL skills are life skills!

A media and information literate person is able to distinguish between reliable sources of information, determine the role of media in culture, and be responsible for their understanding of the influence of mass communication as they move between different media platforms. MIL skills, in particular, are those that are fostered to address societal challenges such as misinformation and disinformation , extremism, cyberbullying , and hate speech on the Internet, as well as cybercrime of various kinds (sextortion, data theft, violation of human rights , etc.).

Critical thinking and media and information literacy both have a combined impact on human behaviour: When a person with a critical mind is exposed to shocking news, they do not jump to conclusions, nor do they react by immediately sharing the news with others before questioning the information given, but rather they seek verification and the logic behind the news. A person with a critical mind is also able to assess the rationale behind the choice of format, timing, and mode of communication. At a time when the media is so influenced and controlled by political agendas, a critical approach to the information we consume helps us to form our own personal opinions and resist attempts to be deceived by questionable sources.

Consequences of being media illiterate

Generally speaking, the biggest problem is that people do not understand what they are looking at. Part of the problem is that they may not understand that they are looking at a piece of information that is designed to get them to carry out bad things or to believe in things that are dangerous, which may lead them to violence. For example, when we talk about the people who decide to become terrorists or extremists, often they listen to the information which they believe to be true. So it is really important that when information comes to them, they understand that they need to interrogate this information closely to make sure that they are not belong told something that may be bad for them or their community.

Alternatively, messages can mislead the young reader to think that they have gained or missed something urging them to commit financially right there and then. In criminal cases, if done particularly well, messages can target the deep emotions and feelings young people tend to hide, driving them to harmful actions. Sad examples of these are sexual perpetrators stalking and harassing their victims to extort money (what is otherwise called sextortion) and online game challenges leading to suicides (read a BBC article about the Blue Whale challenge ). You can also find more information and resources about sextortion and cybercrimes from the Participation Resource Pool.

How to be media literate?

Hands down, the responsibility for the security of information in the media lies with both the media source and the recipient. Media should be professional, but more clearly, people should be able to distinguish media products from those of extremists or people telling stories. Media is important to show the people receiving the information that what they are getting is genuine and that they can tell what professional media is and what is meant to be propaganda. Professional journalists are trained to research each story properly, to use more than one source, to not believe the first person they hear, to check other sources and facts leading up to the story. These are the same criteria young audiences need to look for when they hear or see something.

- Where does it come from?

- What source?

- Is there more than one source?

- Is there somewhere I can look to get more information?

- Are the facts accurate?

When they think in this way, young people learn to listen (focus on what is being said – and what is not), analyze (look more closely and separate the main components of the message ), evaluate (examine different claims and arguments for validity), explain (consider evidence and claims together), and self-regulate (consider our pre-existing thoughts on the topic and any biases we may have) (Facione, 1990).

It is also important to watch out for and recognize the times when we become victims of cognitive distortions. Cognitive Distortions: What They Are and Why They Happen by Very Verified presents the most common biases – confirmation and familiarity biases – along with a few examples, which are easy to relate to.

Guiding questions to youth workers to develop critical thinking

To guide your practice, you can use a list of questions for your young people to ask when thinking critically about the piece of content at hand:

- Questions to the industry: Who is in charge? What do they want of me? Why? What else do they want?

- Questions to the product: What kind of text (genre) is this? How is the message constructed?

- Questions to the audience: Who is this intended for? What assumptions does the test make about the audience? Who am I supposed to be in relation to this text?

- Questions to the values: How real is the text? How/Where do I find the meaning? What values are presented? What is the commercial message ? What is the ideology of the text? What social/political/artistic messages does the text contain?

- Question to predisposition: Do I agree or disagree with the text’s message ? Do I argue or negotiate with the message in the text?

- Questions to the skills: What skills do I need to apply to this text? How do I deconstruct/reconstruct this text? What new skills does this text demand from me?

- Questions to yourself as to the information receiver: What does it all mean to me at the end?

- Most importantly, it is crucial to ask, “how do I know that?” each time you arrive at the answer to any of the questions above to avoid assumptions and false conclusions.

How youth work helps to develop critical thinking and media literacy

The impact that a skilled youth worker can have on the development of critical thinking and media literacy in people is hard to underestimate, especially in an informal learning environment. In school, young people are often restricted in the use of their mobile phones, depriving them of the natural environment of tools and technologies available to them to work with information. There may be different views on whether this is good or not, but the fact remains the same: while they are restricted in the use of their devices, they are not in the same environment where they should know how to use skills in real-time.

In this sense, informal youth work environments can be much more flexible, allowing and encouraging the use of regular media, creating more realistic and valuable learning experiences. For example, youth can share examples from their own newsfeed as case studies for discussion or begin creating content directly in class using the tools and apps available to them. In addition, out-of-school environments foster a different personal dynamic, and that often means an easier way to express one’s views and make a valuable contribution.

So you may be wondering now, how can critical thinking be taught in the classroom/outside of it? Here are four general recommendations to stay on the right course ( Buckingham, 2018 ):

- We should be asking questions about the various ‘languages’ of media – the forms of grammar or rhetoric they employ.

- We should be looking at representation – at how different social groups are represented and how they represent themselves in these online spaces.

- We should be looking at the changing institutional structures and economic strategies of the new media companies.

- We should be looking critically at how people engage with these media – albeit perhaps more as ‘users’ than ‘audiences.’

Practical examples connecting MIL and youth work

Teaching critical thinking and media literacy has never been easy. But it has also never been more necessary than it is today. To meet this demand, youth workers should make sense of dialogic debate rather than getting students to agree to a predefined position on an issue. They should try to use key concepts to ask difficult questions of the media and also of themselves.

The variety of approaches, such as reflecting on media content and creating new artefacts, can make the learning experience very practical and immersive, while a safe and open space for sharing opinions and thoughts can free young people to think, lift their spirits and make a meaningful contribution.

Here are some practical examples of youth work projects that have tackled the various MIL topics well.

If you’re motivated to get your hands on the best resources for educators, you’ll find an impressive collection of inspiring practices, lesson plans, articles, and digital tools for exploring critical thinking and media literacy in the SALTO’s Participation Pool .

Sources to dig deeper:

- What would you say might be a connection between you, young people, and ancient Greece? The answer lies in the practice of critical thinking and in the legacy of a very wise Greek philosopher Socrates. In The Socratic Method: What it is and How to Use it in the classroom , you can read the experiences of a Stanford “Socratic” professor (Reich, 2003). Essentially, the article explains the components of the Socratic method and lists nine useful tips for using it in the classroom.

This article was originally published in Estonia’s youth work magazine MIHUS and has been edited for the Participation Resource Pool.

Aleksandra Mangus

With a Master Degree in Digital Literacy Education (Tampere University, Finland) Aleksandra has been working with UNESCO and other public organisations in Europe. She gives speeches and interactive workshops on MIL and youth engagement, as well as collaborates with SALTO Participation and Information Centre on creating the online Resource Pool for youth workers and educators.

Meelika Hirmo

Meelika Hirmo is a Communications expert who is currently working at Citizen OS promoting digital participation worldwide. The topics of democratic participation, environment, media and information literacy and culture are very close to her heart. She has campaigned for lowering the voting age in Estonia, coordinated international events, led the communication of the international civic movement World Cleanup Day, and is eager to put her skills into practice to create a positive social change.

COVID-19 Resources and Supports Read our Youth Mental Health Joint Statement from Members of the Child and Youth Mental Health Sector and its Stakeholders: Read More

Critical Youth Work: Bridging Theory and Practice

Free professional development opportunity for youth workers to critically analyze key issues and explore options for creative and viable forms of transformative practices that support and strengthen youth wellbeing.

This certificate creates space for youth workers to engage in critical dialogue and learning about the political, social and economic realities that characterize youth work.

Get the tools to critically analyze key youth work issues, and learn about creative and transformative practices that support and strengthen youth wellbeing.

Successful participation and completion of the three modules of the certificate entitles participants to a Certificate of Completion from Youth Research and Evaluation eXchange, York University.

COMPLETELY FREE This certificate is completely free. The cost of all the course materials, as well as lunch on each of the three days of the course, will be covered.

CERTIFICATE STRUCTURE The certificate includes three days of in-person sessions (9:30AM–4:30PM) and 10 hours of online learning.

In-Person Sessions (York University)

Module 1: November 15, 2023

Module 2: November 22, 2023

Module 3: November 29, 2023

Applications Open

October 9–November 1, 2023

Notice of Acceptance

November 3, 2023

Certificates and LinkedIn Badges will be available one week after you complete the certificate.

Questions? Get in touch with us at [email protected] .

“The potential for critical practice is inherent in many aspects of youth work, but workers need to be clearer about concepts such as power, purpose and learning and forms of social action, which connect the personal to the political. Because there can be no critical practice without critical practitioners, youth workers need a strong theoretical framework to underpin their work”.¹

— Bamber, J., & Murphy H.

¹Bamber, J., & Murphy, H. (1999). Youth work: The possibilities for critical practice. Journal of Youth Studies, 2(2), 227-242. doi:10.1080/13676261.1999.10593037

Who is this certificate for?

ELIGIBILITY

- Eligible participants will have a minimum of two years youth sector experience

- Currently engaged in Ontario’s youth sector either in a paid or volunteer capacity

COURSE REQUIREMENTS

- Able to commit 7 hours each week for the in-class modules, and 10 hours for online learning over the three weeks

- Willing to use and advance critical skills and approaches to community engagement, youth leadership and capacity building in communities in Ontario

- Committed to working and learning about youth work within a context of equity, respect, anti-racist and anti-oppressive practices

What topics will the certificate cover?

The Policy and Personal Context of Youth Work in Ontario

The first module will examine and critique the major policies that have impacted Ontario youth work in the last decade. Participants will also be asked to situate themselves and their work within this broader political context.

Theorizing Critical Youth Work – Dilemmas, Challenges and Possibilities

The second module will critically review the major theoretical and conceptual frameworks that underpin youth work discourses such as ‘youth at risk’; resilience; youth violence; criminalization; positive youth development; youth engagement; and marginalization.

MODULE THREE

Theory into Action – Best/Good/Promising Youth Work Practices

The third module on the third and last day will critically integrate the policy, personal and theoretical analyses from Modules One and Two into a practice context.

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Developing Critical Youth Work Theory

Building professional judgment in the community context.

Prices from (excl. shipping):

- Paperback: €42.00

- Hardback: €99.00

- E-Book (PDF): €99.00

- View PDF Flyer

- Preliminary Material Pages: i–xii

- The Paradox of Community Pages: 1–13

- Community Work in the UK – Context, Origins and Developments Community Development and Community Work in the Uk Pages: 15–37

- The Experience of Community Pages: 39–54

- Community and Control Pages: 55–74

- Collectiveness and Connectiveness Pages: 75–86

- Race and Ethnicity Pages: 87–99

- Frederic Froebel Pages: 101–108

- Informal Educators or Bureaucrats and Spies? Detached Youth Work and the Surveillance State Pages: 109–118

- Swimming Against the Tide? Pages: 119–130

- Here’s Looking at you Kid (or the Hoodies Fight Back) Pages: 131–143

- Che Guevara and the Modification of Old Dogmas Pages: 145–164

- Conclusion Pages: 165–166

Share link with colleague or librarian

Product details, collection information.

- Educational Research E-Books Online, Collection 2005-2017

Related Content

Reference Works

Primary source collections

COVID-19 Collection

How to publish with Brill

Open Access Content

Contact & Info

Sales contacts

Publishing contacts

Stay Updated

Newsletters

Social Media Overview

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Statement

Cookie Settings

Accessibility

Legal Notice

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Statement | Cookie Settings | Accessibility | Legal Notice | Copyright © 2016-2024

Copyright © 2016-2024

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

Character limit 500 /500

064. “Look up! Critical thinking in and about youth work” – Training Course

15 nov 064. “look up critical thinking in and about youth work” – training course.

DATA: 15.11.2022

TITOLO PROGETTO: “Look up! Critical thinking in and about youth work”

RICHIESTA PROVENIENTE DA: Óli Örn Atlason (Islanda)

TIPOLOGIA: Training Course

ARGOMENTO: The aim of the training course is to support youth workers and youth leaders to facilitate critical thinking processes with young people by providing tools and methods for them and exploring the concept on personal, organisational and societal levels.

PAESI PARTNER CHE HANNO GIÀ ADERITO: –

ALTRE NOTIZIE:

Activity date: 31 January – 5 February 2023. Venue place, venue country: Iceland Summary: In this training course, we will tackle the topic of critical thinking from different angles. We will not only explore together what critical thinking is, but will also critically reflect on ourselves and the society we are living in. Group size: 25 participants. For participants from: Erasmus+ Youth Programme countries. Target group: Youth workers, Youth leaders, Youth project managers. Accessibility info: This activity and venue place are accessible to people with disabilities. Details: In this complex and fast changing world, the new generation of youth workers must adapt as quickly as their environment is changing. In the reality of climate change, difficult economic situations, fake news, radicalisation, and wars, it is essential to equip both youth workers and young people with the tools of critical thinking. Critical thinking enables us to reflect about, understand and question our own assumptions and beliefs as well as influence on and from organisations and society. In order to understand oneself and the world better, orient oneself in increasing complexity and create more peaceful relations, critical thinking is an essential tool of every youth worker and people connected to youth work. Increased critical thinking in and about youth work allows youth workers to explore the concept of critical thinking from a personal point of view as well as an organisational point of view. The training is meant to facilitate the growth of critical thinking for youth workers and give them tools to multiply that knowledge with the youth they work with. At the same time it is important to think critically about the organisations or informal groups that youth workers work with and contemplate how the work can be ameliorated. Aims and objectives The aim of the training course is to support youth workers and youth leaders to facilitate critical thinking processes with young people by providing tools and methods for them and exploring the concept on personal, organisational and societal levels. The objectives of the training are to: • develop a common understanding of critical thinking as a concept and as a tool in relation to youth work; • improve participants’ critical thinking skills; • learn how to facilitate critical thinking learning situations among young people through youth work; • explore and share methods, tools, resources and best practices related to critical thinking. Learning outcomes At the end of the training participants will: • leave with concrete tools and competences which can be used to facilitate young people’s critical thinking processes; • be better equipped to critically analyse their environment at a personal, interpersonal, and societal level; • enrich their own critical thinking toolbox; • have confidence to implement critical thinking in a team working context. Participants’ profile Participants at the training should be: • youth workers, youth leaders and volunteers working with young people; • interested in the topic; • willing to share their own experiences and actively participate in the learning process; • committed to share their learnings and skills with young people after the training; • comfortable with English as a working language; • able and curious to keep learning after the training. Methodology The methodologies will all be based on non-formal education, with the aim of creating an inclusive space for the participants to explore, learn and grow. They will be fitted to the participants attending the training course and will include the following domains: • facilitated experiences within the group (e.g. role plays, games or outdoor activities); • self-reflection (individually, in pairs or in the group); • exploration of theories and concepts to contextualise experiential knowledge; • experimentation with the gained insights. Costs: Participation fee This project is financed by the participating National Agencies (NAs) of the Erasmus+ Youth in Action Programme. The participation fee varies from country to country. Please contact your National Agency or SALTO Resource Centre (SALTO) to learn more about the participation fee for participants from your country. Accommodation and food Unless specified otherwise, the hosting NA or SALTO of this offer will organise the accommodation and covers the costs for accommodation and food. Travel reimbursement Please contact your NA or SALTO in order to know whether they would support your travel costs. If yes, after being selected, get in touch with your NA or SALTO again to learn more about the overall procedure to arrange the booking of your travel tickets and the reimbursement of your travel expenses. Working language: English.

SCADENZA: 5 December 2022.

- Get Involved

How critical thinking can help the youth avoid conflict and antagonism

September 5, 2022.

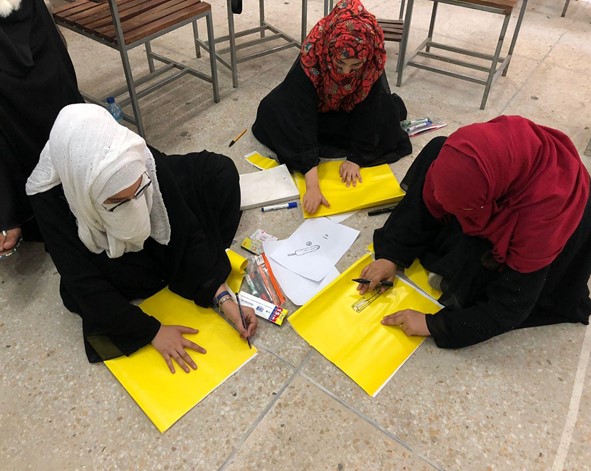

Group work during Intergative Complexity (IC) session in University of Malakand

Pakistan’s education system is marred by rote learning and tutorially instilled conformity which stifles critical thinking. The system generally promotes black and white perspectives about complex issues pertaining to society, economy, culture, and politics. This not only limits the students’ worldview but also creates psychological barriers against the integration and appreciation of ideas, thoughts, and information that does not align with the society’s dominant value systems.

Approached from a peacebuilding perspective, the encounter between artificially imposed monolithic models of thinking and a world characterised by multi-layered complexities often leads to reinforcement of established ways of thinking in intense and sometimes violent ways. This concern has gained increased ascendancy in the current political and social climate, marked by increasing polarisation and resurgence of political and social groups with regressive agendas and formidable rhetoric to mobilise support, especially among youth.

This especially holds true in universities and institutions of higher learning where regressive value systems and myopic world views are often promoted by organized groups to influence students and recruit them for political ends. The situation calls for an overhaul of the educational system in Pakistan by promoting state-of-the-art learning techniques that encourage appreciation of diversity and capacitate students to critically analyse information before making decisions.

To this end, UNDP Pakistan with support from the Australian High Commission (AHC) led an initiative “Integrative Complexity Workshops” to promote critical thinking in institutes of higher learning in Pakistan. The pilot, tested to help reduce young people’s vulnerability to black and white thinking, was held with university students in Swat and Malakand.

Integrative complexity is one's ability to differentiate and integrate multiple perspectives or dimensions on an issue. It allows one to understand an issue by integrating different elements from various points of view while considering an issue. This helps one in overcoming black and white thinking and empathising with others' thoughts and world views about a particular issues while developing one's own understanding of the same.

The workshops involved the application of cutting-edge psychology tools, developed in collaboration with the University of Cambridge UK, to measure the extent to which university students in Swat and Malakand were vulnerable to polarised thinking. The research involved a counterfactual methodology with a control group and a treatment group for comparison. Data was collected at the initial baseline and end line stages to assess the extent to which young people were able to overcome a monolithic understanding of the world after the intervention.

Following the establishment of a baseline, a total of 347 students (182 men and 165 women), doing their masters degrees from universities in Swat and Malakand, participated in the critical thinking workshops that allowed them to empathize with alternative world views and ways of thinking through role-play and playful exploration of various topics pertaining to peace, security, and social cohesion. The role playing exercises included simple group activities in which students divided into cohorts with opposing views about peace and conflict or traditional and scientific knowledge. They held informed debates with each other and attempted to come to an empathetic understanding of the others’ point of view.

More advanced role playing exercises involved students playing the roles of historical figures like Henry VIII and Abraham Lincoln. The participants were encouraged to draw commonalities between historical developments in England and the United States with prevalent scenarios in Pakistan, and think critically about the role of religion in society or the importance of leadership during political crises.

“I never identified myself with people who take drugs. But after attending these sessions, I want to spend some time with them to try to understand how they become addicted and what I can do for them; being intolerant will not solve the problem,” shares a student from the University of Swat.

Exercises like these helped in strengthening the students’ capacities to reflect on and integrate multiple perspectives in their thinking and decision-making. It involves developing empathy for others’ points of view by understanding the conduct or behaviour of people belonging to different religious, ethnic, or economic backgrounds from oneself as rational responses to their own social, political, and economic contexts.

Women students dressed as Catholic Clergy in the IC session on Henry VIII

Students doing IC group work

While the overall results of the exercise have been positive, a worrying aspect of the trainings was the baseline results which showed that the majority of students fell below the fifth percentile in terms of their baseline logical reasoning, indicating compromised ability for logical reasoning.

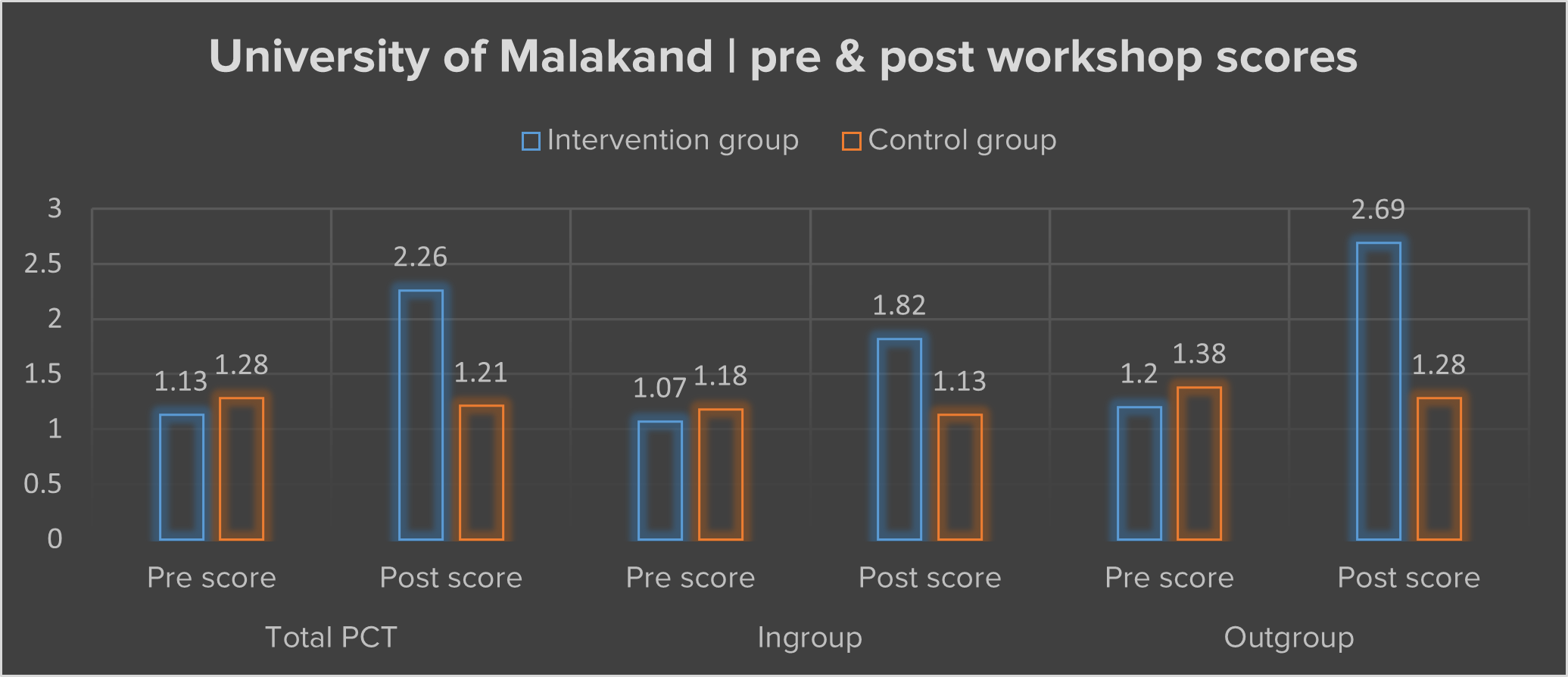

The graph below (Figure 1) provides an overview of the Integrative Complexity (IC) results obtained from the University of Malakand in the pre and post workshop stages. The findings show that the intervention group of students was able to overcome binary or monolithic ways of thinking and critically analyse diverse ways of comprehending information before making a decision.

Figure 1: Integrative Complexity results obtained from the University of Malakand in the pre & post workshop stages

While there have been significant improvements in terms of enhanced IC of the intervention group after participation in the workshops, the overall score of both control and IC group participants indicates logically impaired thinking as evident in the percentile ranks and categories table (Table 1) given below.

Table 1: Integrative Complexity ranking scale

This was an overall trend as the 42 students from the control group also did not fare well in terms of critical and logical thinking capabilities. In this regard, the low IC percentage of university students was similar to the data collected from radicalized young people undergoing rehabilitation through Government run reintegration and rehabilitation camps.

This implies that an uncritical acceptance of information is a key feature of mainstream youth as well as young people involved in anti-social activities, implying that the former is also vulnerable to involvement in violence and conflict if exploited by extremist actors with command over political rhetoric.

The experiment points to a need for the Government of Pakistan to invest in innovative methods to promote critical thinking among youth. This is especially crucial in the current scenario where youth encounter fake news and misinformation through digital and social media platforms while lacking the ability to critically analyse this information. This susceptibility poses serious threats to social cohesion and community resilience especially if the information paints a black and white view of the world and targets vulnerable social, ethnic, or political groups.

While it is impossible to control the information shared, the experiment shows that young people can be taught how to think and process information—making rationally informed and empathetic decisions.

“By participating in these sessions, I learned the importance of transcending rigid thinking about important matters. For instance, Quran is in language that we do not understand. In the session, I learned that when we do not understand our book, it is easy for other people to manipulate us by using the Quran as reference. This is why we should read the Quran in Urdu or Pashto,” shares a student from the University of Malakand

The pilot is a replicable blueprint for adoption by policymakers and educationists in Pakistan. It will help in institutionalizing an empirical methodology that can equip young people with the right tools to process politically charged or socially sensitive information and make informed decisions to avoid possible conflict and antagonism.

We took our findings to the Higher Education Commission (HEC) after which UNDP and Social Welfare Accademics and Training for Pakistan (SWAaT) are now working to roll out these trainings in four more educational institutions across Pakistan. The trainings will focus on countering young people’s vulnerability to being exploited by hate speech and extremist content online.

Dr Feriha Peracha Dr. Peracha has worked as a consultant with UNDP. As a trained psychologist, she has developed and conducted workshops in universities to enhance critical thinking skills, empathy and social intelligence. She is also the CEO of SWAaT for Pakistan.

Hamza Hasan Hamza Hasan works with UNDP's Youth Empowerment Programme as a Senior Social Inclusion Officer. He is a Cultural Anthropologist with experience of promoting and facilitating meaningful participation of vulnerable groups in the development process through research, strategic programme development, and inclusive project implementation

Ayesha Babar (Communications Analyst & Head of Communications Unit, UNDP Pakistan) Tabindah Anwar (Communications Associate, UNDP Pakistan)

Critical Youth Work for Youth-Driven Innovation: A Theoretical Framework

- First Online: 13 December 2017

Cite this chapter

- Daniele Morciano 3 &

- Maurizio Merico 4

838 Accesses

6 Citations

A theoretical framework is presented which conceptualizes how youth work can empower or lead to youth-led innovation. Attention is given to critical youth work, its ability to uncover social inequality mechanisms and to support social emancipation of young people. A comprehensive definition of innovation opens reflection both with respect to the business or technological sphere and to the participatory and cultural domains. The sociological perspective helps to highlight the role of the youth worker as a mediator between the young peoples’ claims for change and the adults’ defense of social stability. The psychoanalysis aspect of the framework offers a theoretical lens to investigate the intra-psychic experiences set in motion when youth work plays a role of intergenerational mediation. Finally, social pedagogy suggests effective educational relationships among young people and youth workers when they strive for generating change.

- Critical youth work

- Critical consciousness

- Theories of change

- Youth work models

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Since 2008, for example, the Flemish Community in Belgium and the Youth Partnership between the European Commission and the Council of Europe organized a series of workshops and research reports on youth work in different national contexts. See the volumes published up to now on http://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/knowledge-books .

Culture jamming is a form of critique and resistance to the ideology of consumerism. It is practiced as a form of disruption or subversion of media culture and its mainstream cultural institutions. Culture jamming activities includes, for example, the adulteration of billboard advertising, anti-advertising media communication and DIY political theater.

In this regard, Dahlin ( 2014 ) draws on social network analysis in order to focus attention on various network structures that appear to facilitate innovation. In the case of structural holes, for example, innovation-oriented learning dynamics appear to be activated thanks to actors who have developed relationships within networks which are in themselves unconnected with “early access to diverse, often contradictory, information and interpretations” (Burt, 2002 , p. 158). In other cases, the presence of a system of small yet connected networks (small-world networks) affects not only the processes of the generation of new ideas but also their dissemination and the promotion of change. Finally, the membership of an actor to different networks (structural folds) increases their ability to “recombine diverse sets of knowledge that are specific to each group to generate novel solutions” (Burt, 2002 , p. 675).

In a broader perspective, any life stage requires the development of new dispositions and capabilities in order to grow towards the successive stage. The pressure towards the life stage transition of a specific age category appears, therefore, as a way to limit its contribution to the present.

Research on intrinsic motivation has identified the hallmarks of a similar education-learning experience such as pleasure and enjoyment, autonomy, and interest; a sense of challenge balanced with a sense of competence and self-efficacy; self-expression (which includes feelings of intense involvement, vitality, completeness, self-realization, and connection with the community). For a literature review on these concepts in education psychology and youth work studies see Morciano ( 2015 ).

Developed in the 1970s and promoted by the University of Connecticut with the explicit intention of developing innovation skills in more talented students, this method is based on a combination of self-learning activities (General Exploratory Activities), group training (Group Training activities) focused on the development of innovation-related skills (e.g., problem-solving, critical thinking, self-learning skills), and study and research on real problems.

Such an approach is also found in surveys involving samples of high-achieving youth with the aim of gathering their views on how to improve educational services in order to facilitate the development and implementation of their talent (e.g., in YACSI, 2002 ).

Particular reference is made to the work of the Youth Partnership between the Council of Europe and the European Commission. See in particular the five volumes of the series “The history of youth work in Europe” published by the Council of Europe Publishing (see http://pjp-eu.coe.int/en/web/youth-partnership/knowledge-books ).

Adolf, M., Mast, J. L., & Stehr, N. (2013). The foundations of innovation in modern societies: The displacement of concepts and knowledgeability. Mind & Society , 12 (1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-013-0112-x

Article Google Scholar

Allaste, A. A., & Tidenberg, K. (2015). “In search of …”: New methodological approaches to youth research . Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Google Scholar

Anderson, C. (2012). Makers: The new industrial revolution makers . New York: Crown Business.

André, P. G. (2016). Counteracting fabricated antigay public pedagogy in Uganda with strategic lifelong learning as critical action. International Journal of Lifelong Education , 35 (1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2015.1129366

Bamber, J., & Murphy, H. (1999). Youth work: The possibilities of critical practice. Journal of Youth Studies , 2 (2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.1999.10593037

Banaji, S., & Burn, A. (2006). The rhetorics of creativity: A literature review . Newcastle upon Tyne: Arts Council England. Retrieved from http://www.creativitycultureeducation.org/research-impact/literature-reviews/

Baskaran, S., & Mehta, K. (2016). What is innovation anyway? Youth perspectives from resource-constrained environments. Technovation , 52 (53), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.01.005

Becker, H. S. (1982). Art worlds . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Belton, B. (Ed.). (2014). Cadjan – Kiduhu’: Global perspectives on youth work . Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Biasin, C. (2010). L’accompagnamento: Teorie, pratiche, contesti [The accompaniment: Theories, practices and contexts]. Milan: Franco Angeli.

Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Brunson, L. (2014). Creating settings for youth empowerment and leadership: An ecological perspective. Child & Youth Services , 35 (3), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2014.938735

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1972). Reproduction in education, society and culture . London: Sage.

Brake, M. (1980). The sociology of youth culture and youth subcultures: Sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll? London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bureau of European Policy Advisers. (2014). Social innovation: A decade of changes . Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Burrel, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis . London: Heinemann.

Burt, R. S. (2002). The social capital of structural holes. In M. F. Guillen, M. Meyer, P. England, & R. Collins (Eds.), The new economic sociology (pp. 148–190). New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Cahn, R. (1998). L’adolescent dans la psychanalyse: L’adventure de la subjectivation [The adolescent in psychoanalysis: The adventure of the subjectivation]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Cameron, C., & Moss, P. (2011). Social pedagogy and working with children and young people: Where care and education meet . London: Jessica Kinglsey Publishers.

Camino, L. (2005). Pitfalls and promising practices of youth–adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections. Journal of Community Psychology , 33 (1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20043

Chisholm, L., Kovacheva, S., & Merico, M. (Eds.). (2011). European youth studies. Integrating research, policy and practice . Innsbruck: MA EYS Consortium.

Conklin, J. (2005). Dialogue mapping: Building shared understanding of wicked problems . Chichester: Wiley.

Cooper, C. (2012). Imagining “radical” youth work possibilities. Challenging the “symbolic violence” within the mainstream tradition in contemporary state-led youth work practice in England. Journal of Youth Studies , 15 (1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2011.618489

Cooper, T., & White, R. (1994). Models of youth work practice. Youth Studies Australia , 13 (4), 30–35.

Côté, J. (2014). Youth studies: Fundamental issues and debates . Basingstoke: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-11214-9

Book Google Scholar

Coussée, F. (2008). A century of youth work policy . Gent: Academia Press.

Coussée, F. (2012). Historical and intercultural consciousness in youth work and youth policy–a double odyssey. In F. Coussée, H. Williamson, & G. Verschelden (Eds.), The history of youth work in Europe (Vol. 3, pp. 7–12). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Dahlin, E. C. (2014). The sociology of innovation: Organizational, environmental, and relative perspectives. Sociology Compass , 8 (6), 671–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12177

D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., & Kallis, G. (2015). Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era . London: Routledge.

Daniel, L. J., & Klein, J. A. (2014). Innovation agendas: The ambiguity of value creation. Prometheus , 32 (1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109028.2014.956504

Davies, B. (2005). Youth work: A manifesto of our times. Youth and Policy , 88 , 5–27.

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Devlin, M. (2010). Young people, youth work and youth policy: European developments. Youth Studies Ireland , 5 (2), 66–82.

Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning. Media architecture pedagogy . New York: Routledge.

Estensoro, M. (2015). How can social innovation be facilitated? Experiences from an action research process in a local network. Systemic Practice and Action Research , 28 (6), 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-015-9347-2

Eyerman, R. (1981). False consciousness and ideology in Marxist theory. Acta Sociologica , 24 (1–2), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169938102400104

Fessenden, S. G. (2015). The voice of the voiceless: Limitations of empowerment and the potential of insideractivist methodologies with anarcho-punk youth. In S. Bastien & H. Holmarsdottir (Eds.), Youth “at the margins”: Perspectives and experiences of participatory research worldwide (pp. 103–121). Rotterdam: Sense. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-052-9_1

Chapter Google Scholar

Freire, P. (1970a). Cultural action and conscientization. Harvard Educational Review , 40 (3), 452–477. 10.17763/haer.40.3.h76250x720j43175

Freire, P. (1970b). Pedagogy of oppressed . London: The Continuum International Publishing.

Funnell, S. C., & Rogers, P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Furlong, A. (2012). Youth studies: An introduction . New York: Routledge.

Giroux, H. (1983). Theories of reproduction and resistance in the new sociology of education: A critical analysis. Harvard Education Review , 53 (3), 257–293. 10.17763/haer.53.3.a67x4u33g7682734

Godin, B. (2010). Innovation without the word: William F. Ogburn’s contribution to the study of technological innovation. Minerva: A Review of Science, Learning & Policy , 48 (3), 277–307.

Hall, S., & Jefferson, T. (1975). Resistance through rituals. Youth subcultures in post-war Britain . London: Routledge.

Hart, R. (1992). Children participation from tokenism to citizenship . Florence: Unicef, Innocenti Research Centre.

Hubert, A. (2010). Empowering people, driving change: Social innovation in the European Union . Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Hurley, L., & Treacy, D. (1993). Models of youth work: A sociological framework . Dublin: Irish Youth Work Press.

Jégou, F., & Manzini, E. (2008). Collaborative services: Social innovation and design for sustainability . Torino: Edizioni POLI.design.

Kunze, I. (2012). Social innovations for communal and ecological living: Lessons from sustainability research and observations in intentional communities. Communal Societies , 32 (1), 39–55.

Lerner, J. V., Phelps, E., Forman, Y., & Bowers, E. P. (2009). Positive youth development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (Vol. 1: Individual bases of adolescent development) (pp. 524–558). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001016

Mannheim, K. (1944). Diagnosis of our time: Wartime essays of a sociologist . New York: Oxford University Press.

Merico, M. (2004). Giovani e società [Youth and society]. Rome: Carocci.

Merico, M. (2012). Giovani, generazioni e mutamento nella sociologia di Karl Mannheim [Youth, generations and change in Karl Mannheim’s sociology]. Studi di Sociologia , 50 (1), 108–129.

Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure . New York, NY: Free Press.

Milmeister, M., & Williamson, H. (Eds.). (2006). Dialogues and networks. Organising exchanges between youth field actors . Luxembourg: Editions Phi.

Morciano, D. (2015). Evaluating outcomes and mechanisms of non-formal education in youth centres. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education , 7 (1), 67–96.

Morciano, D., Scardigno, F., Manuti, A., & Pastore, S. (2016). A theory-based evaluation to improve youth participation in progress: A case study of a youth policy in Italy. Child & Youth Services , 37 (4), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2015.1125289

Morciano, D., Scardigno, F., & Merico, M. (2015). Introduction to the special section: Youth work, non-formal education and youth participation. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education , 7 (1), 1–11.

Naima, T. W., Wong, M., Zimmerman, A., & Parker, E. A. (2010). A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology , 46 , 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9330-0

Passerini, L. (1997). Youth as a metaphor for social change: Fascist Italy and America in the 1950s. In G. Levi & J. C. Schmitt (Eds.), A history of young people in the west (Vol. II, pp. 281–340). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Percy-Smith, B., & Thomas, N. (Eds.). (2009). A handbook of children and young people’s participation: Perspectives from theory and practice . London and New York: Routledge.

Pohlmann, M. (2005). The evolution of innovation: Cultural backgrounds and the use of innovation models. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management , 17 (1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320500044396

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences , 4 , 155–169.

Rustin, M. (2001). Reason and unreason: Psychoanalysis, science and politics . Middletown: Wesley University Press.

Sandlin, J. A., & Milam, J. L. (2008). Mixing pop (culture) and politics: Cultural resistance, culture jamming and anti-consumption activism as critical public pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry , 38 (3), 323–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2008.00411.x

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sebba, J., Griffiths, V., Luckock, B., Hunt, F., Robinson, C., & Flowers, J. (2009). Youth-led innovation: Enhancing the skills and capacity of the next generation of innovators . London: NESTA–National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skott-Myhre, H. A. (2005). Captured by capital: Youth work and the loss of revolutionary potential. Child & Youth Care Forum , 34 (2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-004-2182-8

Skott-Myhre, H. A. (2009). Youth and subculture as creative force: Creating new spaces for radical youth work . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, M. K. (1988). Developing youth work: Informal education, mutual aid and popular practice . Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Trier, J. (2014). Detournement as pedagogical praxis . Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-800-8

Trigilia, C. (2007). La costruzione sociale dell’innovazione: economia, società e territorio [The social construction of innovation: Economy, society and territory]. Florence: Firenze University Press.

Verschelden, G., Coussée, F., Van de Walle, T., & Williamson, H. (2009). The history of youth work in Europe and its relevance for youth policy today . Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Wainrib, S. (2012). Is psychoanalysis a matter of subjectivation? International Journal of Psychoanalysis , 93 , 1115–1135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2012.00645.x

Wilson, B. (2006). Ethnography, the Internet, and youth culture: Strategies for examining social resistance and “online-offline” relationships. Canadian Journal of Education , 29 (1), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/20054158

Winnicott, D. (1971). Playing and reality . London: Tavistock Publication.

Woodman, D., & Wyn, J. (2014). Youth and generation: Rethinking change and inequality in the lives of young people . London: Sage.

Worden, E. A., & Miller-Idriss, C. (2017). Beyond multiculturalism: Conflict, co-existence, and messy identities. International Perspectives on Education & Society , 30 , 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-367920160000030018

YACSI. (2002). Making innovation sustainable among youth in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.innovationstrategy.gc.ca/cmb/innovation.nsf/SectorReports/YACSI .

Zeldin, S., Christens, B. D., & Powers, J. L. (2012). The psychology and practice of youth-adult partnership: Bridging generations for youth development and community change. American Journal of Community Psychology , 51 , 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9558-y

Zeschky, M. B., Winterhalter, S., & Gassmann, O. (2014). From cost to frugal and reverse innovation: Mapping the field and implications for global competitiveness. Research-Technology Management , 57 (4), 20–27.

Zimmerman, K. (2007). Making space, making change: Models for youth-led social change organizations. Children, Youth and Environments , 17 (2), 298–314.

Download references

Acknowledgment

This chapter is based on the results of a research review carried out within the research project “Non-formal education as a tool of youth employability through youth-led innovation” (2016–2018), funded by the Puglia Region (Italy), “Future in Research” program.

While the authors together wrote the Introduction, Daniele Morciano contributed most substantially to the discussion regarding the paragraphs “Innovation and critical youth work” and “How critical youth work supports youth-driven innovation,” whereas Maurizio Merico contributed most to the discussion on the paragraph “Opportunities and challenges.”

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Bari, Bari, Italy

Daniele Morciano

University of Salerno, Fisciano, Italy

Maurizio Merico

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health Science, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway

Sheri Bastien

Oslo and Akershus University College, Oslo, Norway

Halla B. Holmarsdottir

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Morciano, D., Merico, M. (2017). Critical Youth Work for Youth-Driven Innovation: A Theoretical Framework. In: Bastien, S., Holmarsdottir, H. (eds) Youth as Architects of Social Change. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66275-6_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66275-6_3

Published : 13 December 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-66274-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-66275-6

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

6 tips for teens on how to develop critical thinking

My name is Marianna and I am 19 years old. I live in Kyiv, Ukraine.

We all know how important it is for young people to stay safe and savvy online. With the rise in 'fake news’, experts have warned us to check sources carefully, pay attention to manipulative headlines and think twice about the stories we share with friends.

Like me, you have probably heard these tips many times. But I didn’t truly become media literate until I took the time to develop critical thinking.

Media literacy affects the way we look at and perceive the world. For me, it started at school, when I was constantly writing research papers for competitions. I had to carefully check all the facts because I needed to be ready for anything when it came to defending my paper. And today, at Model United Nations conferences, I have to be sure of every word I say.

Here are six ways that you can, too.

1. Online games

Let’s start with the simplest way – online games. Maybe you are skeptical about them, or you play every night. It doesn’t matter, because you can always join.

My first game about critical thinking was the one that, for me, destroyed the myths about decentralization – My Community . At that time, I didn’t know much. But the game helped me work things out and debunk the main myths.

There are lots of games like this – you can easily find them on your own. Of the most popular, I can recommend the following:

- (In)corruptibility – how to fight corruption and how critical thinking skills are needed for that;

- Mission Media Literacy – helps adults check whether they are able to resist fake news and prejudices;

- The Adventures of Literatus – demonstrates how to search for information and distinguish fake news from real news;

- NABU Investigating – how to fight corruption and uncover real facts.

The first time I seriously got into critical thinking began with the book by Oksana Moroz, The Nation of Vegetables? How Information Changes the Thinking and Behaviour of Ukrainians . My grandpa gave me the book as a present. I liked that there were many specific examples of ways to counteract information overload, so I continued to search for similar books.

There are a lot of books about critical thinking, and you can decide whether to read them all. You can read Hans Rosling’s Factfulness , which teaches you to read between the lines and discuss misconceptions about the world. Another good option is Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow , where you will learn how our irrationality affects our actions.

A good idea is to read the reviews before the book itself. Pay attention not to how many stars a book is given, but to the impression that it left on readers.

3. Internships at fact-checking initiatives

Internships can make you look at the world in a new way. Initiatives, organisations and projects that are often looking for volunteers include VoxCheck, StopFake, On the Other Side of the News, Without Lies, Internews-Ukraine and Media Detector. And if there is no vacancy available, just email them – they will hear you. After all, there is much more fake news than people ready to unravel it.

4. Generating your own content

Another option is to create your own fact-checking platform or media literacy blog. In this way, you will realize several goals simultaneously:

- join the process of change;

- independently investigate fake news and distinguish it much better;

- gain an opportunity for self-expression and new social contacts.

Self-study really helps – you learn to read the texts that lie beyond the first page of the search engine, and you forget about prejudices and stereotypes. Of course, a big blog will need the help of at least one other person – for example, if you don’t know how to design a webpage or if you have difficulty editing text. But, like this, you will also be able to find new friends, because there are more future change-makers nearby than you think.

5. Conferences and webinars on media literacy

This is necessary if you are used to learning from someone and not on your own.

Fortunately, there are so many webinars now that there are plenty to choose from, and most of them are available for free. In addition, at the end of some online courses, they open a set of internships at the organisations that created them, so you are able to master some practical skills later on.

Not sure which webinars to start with? I helped to start YNGO PLUS, a youth organisation that runs informal educational projects for young people. Sometimes we hold webinars on media literacy and critical thinking, so feel free to join us on social media and stay tuned.

6. DilemMe Critical Thinking Board Game

You might be asking – why are you writing about critical thinking at all?

It is because my team and I are also working on the first board game about critical thinking and media literacy called DilemMe. We developed the concept during an online hackathon on media literacy called INFOTON, organized by UNICEF and supported by USAID.

What do you do when a neighbour tells everyone to take garlic as a medication? What if a friend denies the existence of HIV? These are the situations you must face in the game. For each situation – and there are as many as three hundred in the game – we have created a QR code which links to tips and links for further research, if you are interested.

We have been working on the board game for a very long time. Not only did we create it during a pandemic, but all members of the team live in different cities of Ukraine. One of us even lives in Riga now! However, we are all united by the desire to prove that critical thinking is a skill worth learning.

Develop critical thinking and don’t let fake news flood the world!

About Marianna Iovenko:

I am 19 years old, I was born and live in Kyiv. I am a third-year student of law at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and, since 2020, I have been the head of the youth non-governmental organization PLUS. I also actively participate in sessions of the European Youth Parliament. Following my participation in INFOTON, run by Inscience and UNICEF, I helped to create a board game about critical thinking and countering fake news. In my free time, I write fiction, learn foreign languages on my own, travel and jog.

View the discussion thread.

Related Stories

Education: My right, my fight, not a privilege.

The Story of the Digital World from Another Angle

The Click moment: Seizing the opportunity and bridging the digital divide

STEM education

C 2019 Voices of Youth. All Rights Reserved.

- Boyce Digital Repository Home

- Dissertations, Theses, and Projects

- Restricted Access Dissertations and Theses

The role of critical thinking in youth ministry leadership praxis: A grounded theory

Description, collections.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Biden-Harris Administration Announces $39.4 Million in Funding Opportunities for Grants to Help Advance the President’s Unity Agenda

Today, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), has announced notices of funding opportunities for grant programs addressing behavioral health across the country. The grant opportunities total $39.4 million and are part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s priorities to beat the overdose epidemic and tackle the mental health crisis – two key pillars of the President’s Unity Agenda for the nation.

“We are building a truly integrated, equitable and accessible behavioral health care system,” said HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra. “Our efforts to change the way mental health is viewed and treated in this country are making it possible for more people to get the care and support they need. This funding is a critical investment that the Biden-Harris Administration is making to strengthen behavioral health in America.”

“The Department remains committed to ensuring we can connect more Americans to the care they need, and integrating behavioral health into our communities and primary care systems is critical to meeting people where they are,” said Deputy Secretary Andrea Palm. “The resources SAMHSA is announcing today further demonstrate our commitment to improving access to behavioral health care.”

“SAMHSA grants allow individuals and their families to get the support and care they need for mental health and substance use challenges,” said Miriam E. Delphin-Rittmon, Ph.D., HHS Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use and the leader of SAMHSA. “This funding addresses a broad range of supports including integrating primary and behavioral health care and facilitating substance use prevention and recovery. It will also improve the lives of people across the United States by helping to bridge gaps for mental health services in communities.”