- Request new password

- Create a new account

Introducing Communication Research: Paths of Inquiry

Student resources.

Welcome to the SAGE edge site for Introducing Communication Research, Fourth Edition .

The SAGE edge site for Introducing Communication Research by Donald Treadwell and Andrea Davis offers a robust online environment you can access anytime, anywhere, and features an impressive array of free tools and resources to keep you on the cutting edge of your learning experience.

Introducing Communication Research: Paths of Inquiry teaches students the basics of communication research in an accessible manner by using interesting real-world examples, engaging application exercises, and up-to-date resources. Best-selling author Donald Treadwell and new co-author Andrea Davis guide readers through the process of conducting communication research and presenting findings for scholarly, professional, news/media, and web audiences. The Fourth Edition continues to emphasize the Internet and social media as topics of, and tools for, communication research, and incorporates new content on online methodologies, qualitative research, critical methodologies, and ethics.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Donald Treadwell and Andrea Davis for writing an excellent text. Special thanks are also due to Hailey Gillen Hoke of Weber State University, Vicki Karns of Suffolk University, and Thomas Wright of Temple University for developing the ancillaries on this site.

For instructors

Access resources that are only available to Faculty and Administrative Staff.

Want to explore the book further?

Order Review Copy

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Communication Research Methodology

DOI link for Communication Research Methodology

Get Citation

This introduction to communication research methods takes the student from the conceptual beginnings of a research project through the design and analysis. Emphasizing the correct questions to ask and how to approach the answers, authors Gary Petty, Cheryl Campanella Bracken, and Elizabeth Babin approach social science methods as a language to be learned, requiring multiple sessions and reinforcement through practice. They explain the basics of conducting communication research, facilitating students’ understanding of the operation and roles of research so that they can better critique and consume the materials in their classes and in the media.

The book takes an applied methods approach, introducing students to the conceptual elements of communication science and then presenting these elements in a single study throughout the text, articulating the similarities and differences of individual methods along the way. The study is presented as a communication campaign, involving multiple methodologies. The approach highlights how one method can build upon another and emphasizes the fact that, given the nature of methodology, no single study can give complete answers to our research questions.

Unique features of the text:

- It introduces students to research methods through a conceptual approach, and the authors demonstrate that the statistics are a tool of the concepts.

- It employs an accessible approach and casual voice to personalize the experience for the readers, leading them through the various stages and steps.

- The presentation of a communication campaign demonstrates each method discussed in the text. This campaign includes goals and objectives that will accompany the chapters, demonstrates each individual methodology, and includes research questions related to the communication campaign.

The tools gained herein will enable students to review, use, understand, and critique research, including the various aspects of appropriateness, sophistication and utility of research they encounter.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part i | 7 pages, a new language, chapter 1 | 11 pages, reality, what a concept: definition is everything, chapter 2 | 19 pages, six of one, half a dozen of the other: explication, validity, reliability, and measurement, chapter | 15 pages, ladies and gentlemen, place your bets: probability, sampling theory, and hypothesis testing, chapter 4 | 12 pages, ask it in the form of a question, please: developing questions and creating groups, chapter 5 | 14 pages, are they apples and oranges, or fruit: describing groups, part ii | 55 pages, methodologies/making observations, chapter 6 | 11 pages, getting to know you: empirical qualitative approaches, chapter 7 | 10 pages, intelligent design: basic approaches to design, chapter | 12 pages, kids, don’t try this at home: experimental design, chapter 9 | 11 pages, survey says: survey methodology, chapter 10 | 9 pages, is it a boy or a girl are those the only choices: content analysis, part iii | 2 pages, data analysis, chapter 11 | 9 pages, and what does it all mean: analytic principles, chapter | 11 pages, the count says: quantitative approaches, who are you calling a deviate: group differences, anova and the f, chapter | 13 pages, we need to have a talk about relationships: correlation, simple regression, multiple regression, chapter 15 | 8 pages, nobody got hurt: human subjects, institutional review boards, and ethics.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

- Words, Language & Grammar

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Media and Communication Research Methods: An Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches 5th Edition

This step-by-step introduction to conducting media and communication research offers practical insights along with Arthur Asa Berger’s signature lighthearted style to make discussion of qualitative and quantitative methods easy to comprehend. The Fifth Edition of Media and Communication Research Methods includes a new chapter on discourse analysis; expanded discussion of social media, including discussion of the ethics of Facebook experiments; and expanded coverage of the research process with new discussion of search strategies and best practices for analyzing research articles. Ideal for research students at both the graduate and undergraduate level, this proven book is clear, concise, and accompanied by just the right number of detailed examples, useful applications, and valuable exercises to help students to understand, and master, media and communication research.

- ISBN-10 1544332688

- ISBN-13 978-1544332680

- Edition 5th

- Publication date February 1, 2019

- Language English

- Dimensions 6 x 1 x 8.75 inches

- Print length 488 pages

- See all details

Products related to this item

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

Arthur Asa Berger is Professor Emeritus of Broadcast and Electronic Communication Arts at San Francisco State University, where he taught between 1965 and 2003. He has published more than 100 articles, numerous book reviews, and more than 60 books. Among his latest books are the third edition of Media and Communication Research Methods: An Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (2013), The Academic Writer’s Toolkit: A User’s Manual (2008), What Objects Mean: An Introduction to Material Culture (2009), Bali Tourism (2013), Tourism in Japan: An Ethno-Semiotic Analysis (2010), The Culture Theorist’s Book of Quotations (2010), and The Objects of Our Affection: Semiotics and Consumer Culture (2010). He has also written a number of academic mysteries such as Durkheim is Dead: Sherlock Holmes is Introduced to Sociological Theory (2003) and Mistake in Identity: A Cultural Studies Murder Mystery (2005). His books have been translated into eight languages and thirteen of his books have been translated into Chinese.

Product details

- Publisher : SAGE Publications, Inc; 5th edition (February 1, 2019)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 488 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1544332688

- ISBN-13 : 978-1544332680

- Item Weight : 1.46 pounds

- Dimensions : 6 x 1 x 8.75 inches

- #142 in Media Studies (Books)

- #899 in Communication Reference (Books)

- #2,095 in Communication & Media Studies

About the author

Arthur asa berger.

ARTHUR ASA BERGER

I am the author of more than 100 articles and more than 90 books on popular culture, media, humor, advertising and tourism. I have also written some academic murder mysteries in which I bump off academics various ways and write nasty things about academia. I was born in Boston, Mass. I went to school at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, MA for my BA degree in literature and philosophy. I went to the University of Iowa in Iowa City for my MA degree in journalism (but I also studied at the Writers' Workshop there)and I went to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis for my Ph.D degree in American Studies. I wrote my dissertation on the comic strip Li'L Abner. After I received my MA degree I was drafted into the US Army and I did public information in Washington DC for two years. I also wrote high school sports for the Washington Post weekends while I was in the Army. I lived in Italy for a year in 1963 and taught American literature at the University of Milan. I also lived in England for a year in 1973 doing research on pop culture there. I taught at San Francisco State University from 1965 until 2003, when I retired. My books have been translated into Russian, Italian, German, Arabic, Indonesia, Swedish, Korean and Chinese. These Chinese like my books and have translated 12 of my books. Not all reviewers like my books. A review of my book THE TV-GUIDED AMERICAN, published in the early 1970s read "Berger is to the study of television what Idi Amin is to tourism in Uganda." I've lectured in many different countries, such as England, France, Germany, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Thailand, Vietnam, Peru, and Tunisia. I was a visiting professor in Hong Kong for two months (in a school of tourism)in 2008 and I taught media criticism for six weeks in 2009 at Jinan University in Guangzhou and Tsing Hua University in Beijing. I spent a month in Argentina in September and October of 2012 lecturing on semiotics, media criticism and post modernism. In the course of my career I've lectured in around 20 foreign countries. I have continued to write and love to travel. I've visited more than 60 countries over the years. I live in Mill Valley, California.

I have some new books I've written are being published that will be of interest: Everyday Life in the Postmodern World (Springer), Crowds in American Culture (Anthem), Searching for a Self (Anthem), Shakespeare's Comedy of Errors (Anthem),

The Political Animal (Cambridge Scholars).

Here is a complete list of my books and their publishers.

1. Li'l Abner, 1970 (Twayne), 1994 (Univ. of Mississippi Press)

2. The Evangelical Hamburger, 1970 (MSS Publications)

3. Pop Culture, 1973 (Pflaum)

4. About Man, 1974 (Pflaum)

5. The Comic Stripped American, 1974 (Walker & Co., Penguin, Milano Libri)

6. The TV Guided American, 1975 (Walker & Co.)

7. Language in Thought and Action (in collaboration with S.I.Hayakawa, 1974, 1978) (HBJ)

8. Film in SOCIETY, 1978 (Transaction)

9. Television as an Instrument of Terror, 1978 (Transaction)

10. Media Analysis Techniques, 1982, 2nd Edition 1998 (SAGE)

11. Signs in Contemporary Culture, 1984 (Longman); 2nd edition, Sheffield, 1998. (Indonesian edition, 2003)

12. Television in SOCIETY, l986 (Transaction)

13. Semiotics of Advertising, 1987 (Herodot)

14. Media USA, 1988, (Longman 2nd Edition, 1991

15. Seeing is Believing: An Introduction to Visual Communication, 1989 (McGraw-Hill).

16. Political Culture and Public Opinion, 1989 (Transaction)

17. Agitpop: Political Culture and Communication Theory, 1989 (Transaction)

18. Scripts: Writing for Radio and Television, 1990 (SAGE)

19. Media Research Techniques, 1991, 2nd edition 1998 (SAGE)

20. Reading Matter, 1992 (Transaction)

21. Popular Culture Genres, 1992 (SAGE)

22. An Anatomy of Humor, 1993. (Transaction)

23. Improving Writing Skills, 1993 (SAGE)

24. Blind Men & Elephants: Perspectives on Humor, 1995 (Transaction)

25. Cultural Criticism: A Primer of Key Concepts, 1995 (SAGE

26. Essentials of Mass Communication Theory, 1995 (SAGE)

27. Manufacturing Desire: Media, Popular Culture & Everyday Life, 1996 (Transaction)

28. Narratives in Popular Culture, Media & Everyday Life, 1997 (SAGE)

29. The Genius of the Jewish Joke, 1997 (Jason Aronson)

30. Bloom’s Morning, 1997 (Westview/HarperCollins)

31. The Art of Comedy Writing, 1997 (Transaction)

32. Postmortem for a Postmodernist, 1997 (AltaMira).

33. The Postmodern Presence, 1998. (AltaMira)

34. Media & Communication Research Methods, 2000. (SAGE)

35. Ads, Fads & Consumer Culture, 2000. (Rowman & Littlefield)

36. Jewish Jesters, 2001. (Hampton Press)

37. The Mass Comm Murders: Five Media Theorists Self-Destruct. 2002 (Rowman & Littlefield).

38. The Agent in the Agency. 2003 (Hampton Press)

39. The Portable Postmodernist, 2003 (AltaMira Press)

40. Durkheim is Dead: Sherlock Holmes is Introduced to Social Theory, 2003 (AltaMira Press)

41. Media and Society, 2003 (Rowman & Littlefield)

42. Games and Activities for Media, Communication and Cultural Studies Students. 2004. (Rowman & Littlefield)

43. Ocean Travel and Cruising, 2004 (Haworth)

44. Deconstructing Travel: A Cultural Perspective, 2004 (AltaMira Press)

45. Making Sense of Media: Key Texts in Media and Cultural Studies, 2004 (Blackwell)

46. Shop Till You Drop: Perspectives on American Consumer Culture. 2004. (Rowman & Littlefield)

47. The Kabbalah Killings. 2004. (PulpLit)

48. Vietnam Tourism. 2005. (Haworth)

49. Mistake in Identity: A Cultural Studies Murder Mystery. 2005. (AltaMira)

50. 50 Ways to Understand Communication. 2006. Rowman & Littlefield.

51. Thailand Tourism. 2008. (Haworth Hospitality and Tourism Press)

52. The Golden Triangle. 2008. (Transaction Books).

53. The Academic Writer’s Toolkit: A User’s Manual. 2008. (LeftCoast Press)

54. What Objects Mean: An Introduction to Material Culture 2009. (LeftCoast Press)

55. Tourism in Japan: An Ethno-Semiotic Analysis. 2010 (Channel View Publications)

56. The Cultural Theorist’s Book of Quotations. 2010. (Left Coast Press)

57. The Objects of Affection: Semiotics and Consumer Culture. 2010. (Palgrave)

58. Understanding American Icons: An Introduction to Semiotics. 2012. (Left Coast Press).

59. Media, Myth and Society. 2012. (Palgrave Pivot)

60. Theorizing Tourism. 2012. (Left Coast Press).

61. Bali Tourism. 2013. (Haworth).

62. A Year Amongst the UK: Notes on Character and Culture in England 1973-1974. Marin Arts Press.

63. Dictionary of Advertising and Marketing Concepts. 2013 (Left Coast Press)

64. Messages: An Introduction to Communication. 2015. (Left Coast Press)

65. Gizmos, or The Electronic Imperative. 2015. (Palgrave)

66. Applied Discourse Analysis. 2016. (Palgrave)

67. Marketing and American Consumer Culture. 2016 (Palgrave)

68. Perspectives on Everyday Life. 2018 (Palgrave)

69. Cultural Perspectives on Millennials. 2018 (Palgrave)

70. Freud is Fixated: Sherlock Holmes and Psychoanalytic Theory. 2018. (Marin Arts Press)

71. Semiotics of Sport. 2018. (Marin Arts Press)

72. Signs and Society: 2019 (Nanjing Normal University Press)

73. Three Tropes on Trump. 2019. (Peter Lang)

74. Brands and Cultural Analysis. 2019 (Palgrave)

75. Shopper’s Paradise: Retail and American Consumer Culture 2019 (Brill)

76. Humor, Psyche, and Society. 2020. (Vernon)

77. Saussure Suspects. 2020. (Marin Arts)

78. Travel Notes. 2020. (Marin Arts)

79. My Name is Sherlock Holmes. 2020 (Marin Arts)

80. Trump’s Followers. 2020. (Peter Lang)

81. USA POP. 2020. (Cambridge Scholars)

82. LUXE: Luxury in American Consumer Culture. 2020 (Cambridge Scholars)

83. The Creative Process. 2021. (Cambridge Scholars)

84. Smooth Sailing. 2022. (Brill) in press

85. Why We Love Westerns. 2022. (DSP)

86. Searching for a Self. 2022. (Vernon)

87. Everyday Life in the Postmodern World. 2022. (Springer) in press

88. Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors. 2022. (Anthem) in press

89. Semiotics of Sport. 2022. (Brill) in press

90. The Political Animal. 2022?

91. The New Crowd: An American Variation. 2022?

92. Taste: Why We Like What We Like. 2022?

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 75% 10% 5% 7% 3% 75%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 75% 10% 5% 7% 3% 10%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 75% 10% 5% 7% 3% 5%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 75% 10% 5% 7% 3% 7%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 75% 10% 5% 7% 3% 3%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

1st Edition

Communication Research Methodology A Strategic Approach to Applied Research

- Taylor & Francis eBooks (Institutional Purchase) Opens in new tab or window

Description

This introduction to communication research methods takes the student from the conceptual beginnings of a research project through the design and analysis. Emphasizing the correct questions to ask and how to approach the answers, authors Gary Petty, Cheryl Campanella Bracken, and Elizabeth Babin approach social science methods as a language to be learned, requiring multiple sessions and reinforcement through practice. They explain the basics of conducting communication research, facilitating students’ understanding of the operation and roles of research so that they can better critique and consume the materials in their classes and in the media. The book takes an applied methods approach, introducing students to the conceptual elements of communication science and then presenting these elements in a single study throughout the text, articulating the similarities and differences of individual methods along the way. The study is presented as a communication campaign, involving multiple methodologies. The approach highlights how one method can build upon another and emphasizes the fact that, given the nature of methodology, no single study can give complete answers to our research questions. Unique features of the text: It introduces students to research methods through a conceptual approach, and the authors demonstrate that the statistics are a tool of the concepts. It employs an accessible approach and casual voice to personalize the experience for the readers, leading them through the various stages and steps. The presentation of a communication campaign demonstrates each method discussed in the text. This campaign includes goals and objectives that will accompany the chapters, demonstrates each individual methodology, and includes research questions related to the communication campaign. The tools gained herein will enable students to review, use, understand, and critique research, including the various aspects of appropriateness, sophistication and utility of research they encounter.

Table of Contents

Gary Pettey, Cheryl Campanella Bracken, Elizabeth B. Pask

About VitalSource eBooks

VitalSource is a leading provider of eBooks.

- Access your materials anywhere, at anytime.

- Customer preferences like text size, font type, page color and more.

- Take annotations in line as you read.

Multiple eBook Copies

This eBook is already in your shopping cart. If you would like to replace it with a different purchasing option please remove the current eBook option from your cart.

Book Preview

The country you have selected will result in the following:

- Product pricing will be adjusted to match the corresponding currency.

- The title Perception will be removed from your cart because it is not available in this region.

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

- Chapter One: Introduction

In this chapter, we first describe how developing a command of research methods can assist you in your careers and personal lives. Second, we provide a brief definition of our topic of study in this book – communication research. Third we identify the predominant research and creative methods used in the field of Communication Studies. Fourth, we explain the academic roots of the diverse methods used in communication studies: the humanities and social sciences. Fifth, we explain the implicit and explicit relationships between theory and research methods. Sixth, we describe how the choice of research methods influences the results of a study. Sixth, we provide a preview of the remainder of the book, and finally, seventh, we describe our approach to writing this book.

- Chapter Two: Understanding the distinctions among research methods

- Chapter Three: Ethical research, writing, and creative work

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 2 - Doing Your Study)

- Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods (Part 3 - Making Sense of Your Study)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Five: Qualitative Data (Part 2)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 1)

- Chapter Six: Critical / Rhetorical Methods (Part 2)

- Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results

How Will Research Methods Help in My Life?

If you want to learn practical skills relevant to your professional, personal and community life, learn research methods. Given that daily life is full of decision-making opportunities and challenges, knowing how to effectively do research is essential. Ideally, any decision you make is based on research, and rigorous methods enable you to conduct better research and make better decisions. People who know how to ethically use research methods quickly become leaders in their workplaces and communities. Research also can inform creative expression. If you understand why things work the way they do, you can make more thoughtful, creative choices.

Consider how you make choices in everyday life such as the following:

- Which route to take to get to class on time

- What to eat for lunch

- How to make a major purchasing decision

Or, how you address more complex questions such as whether dishonesty is ever warranted, or if there is a God?

Brainstorm all the ways in which you think you know something for one or more of the examples listed above.

If you are like previous students in this course, you may have responded: "read," "observe," "intuit," "faith," "advice," "physical senses," "test it out," "compare," "Google it" and more.

What does this activity reveal about how you come to know something?

We hope the activity above reveals you already are a researcher, and use some informal research methods every day of your life. You likely use more than one way to know something. Multiple methods construct knowledge. And being educated includes questioning the results of each method. For example, if you use Google or Wikipedia to find information, how do you know the source is reliable? What clues should you look for?

Research methods will help you be a better ....

- Critical Consumer — You will find you look at the world of information through a more refined lens. You may ask questions about information you never thought to ask before, such as: "What evidence is this conclusion based on?" "Why did the researcher interview rather than survey a larger number of people?" and "Would the results have been different if the participants were more ethnically and racially diverse?

- Competent Contributor — When an organization you belong to wants to attain a group's input on a program, product or service, you will know how to construct, administer and statistically analyze survey results. Or if the project warrants small focus group discussions for information gathering, you will know how to facilitate them as well as how to identify themes from the discussions.

- Problem-Solver — Research methods skills are nearly synonymous with problem- solving skills. You will learn how to synthesize information, assess a current state of knowledge, think creatively, and make a plan of action for original research gathering and application.

- Strategic Planner – Knowing research methods can teach you how to gather the necessary information to forecast and plan tactically rather than only react to situations, whether it is in your work place or personal life.

- Decision-Maker — As you cross through life transitions and major decisions stare you in the face, such as how to keep a job, give the best care for aging parents, or select the least invasive medical treatment, you will have coping skills to help you break down the decision into manageable parts and approach the decision making process from more than one perspective.

- Informed Citizen — As a person educated in how knowledge is constructed, you will have the skills needed to be vigilant for your community and to identify and address potential problems, be they environmental, political, social, educational, and/or about quality of community life.

For more specific ideas about how a command of research methods can broaden your life options, see the examples of practical research at Communication Currents: Knowledge for Communicating Well . It is a reader-friendly magazine where communication scholars discuss research about current social problems ( The National Communication Association - Communication Currents ). Also check out the National Communication Association website http://www.natcom.org/ for careers in communication.

The Topic of Study: Communication Research

You may have noticed we, the authors, use the singular form of the term communication to refer to the academic field of study on a wide variety of message types, rather than the plural form: communications. The distinction is a quick way to tell who understands communication is one specific field of study and who does not, so you will want to use the proper, singular form when referring to the field of study. Communications – plural is used only when referring to multiple media sources, as in "the communications news media" (Korn, Morreale, & Boileau, 2000).

The forms communication can take are nearly endless. They include, but are not limited to: language, nonverbal communication, one-on-one interpersonal communication, organizational communication, film, oral interpretations of prose or poetry, theatre, public speeches, public events, political campaigns, public relations campaigns, news media, Internet, social media, photography, television, social movements, performance in everyday life, journalistic writing, and more. Yet, the theme that runs through almost all Communication Studies research is that communication is more than a means to transmit information. Although it is used to transmit information and get things done, more importantly, communication is the means through which people make meaning and come to understand each other and the world.

Because of this, communication scholars tend to operate with the assumption that reality is a social construction, constructed through human beings' use of communication, both verbal and visual (Gergen, 1994). Thus, when communication scholars conduct research, they ask questions not only about how to make communication more precise and/or effective, but they also ask questions about how communication is being used in a particular context to shape individuals' and groups' world views.

Research, as a form of communication, contributes to the social construction of knowledge. Knowledge does not come out of a vacuum that is free of cultural values. Instead, research results, or what society calls knowledge, is influenced by the values, beliefs, methods choices, and interpretations of those in a given culture doing the research. Knowledge and one's reality are constructed through an interactive, interpretive process. Although scholars from a more traditional natural science view might argue there are absolute truths and set realities, in the study of human interaction, there are few universal truths about communication and what is seen as knowledge changes across cultures and over time. Unique cultural contexts, social roles, and inequities create a wide spectrum of behaviors ( Kim , http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weber/ ). That is what makes miscommunication common and why research in our field is so much in demand. It is highly practical and relevant work.

Research refers to the systematic study of a topic and can include social science and creative work. Research, quite simply, refers to people's intellectual work of gathering, organizing, and analyzing data, which enables them to create meaning they can then present to others. Research is conducted to answer questions or solve problems in a systematic way. Being systematic means that the steps of the study are guided by principles and theory, rather than just chaotic wandering; the data used is representative and not just anecdotal or random. Being systematic in a way that can be replicated is usually emphasized more in natural and social science research, such as organizational and interpersonal communication research, than the humanities and fine arts, such as rhetorical studies and performance studies, but, rhetoric scholars and artists also rely on methods and theoretical training to guide their work.

Communication Studies research has several unique characteristics:

- Communication research is the study of how people make meaning. If one thinks of communication as the process of making meaning, then the study of communication is the study of this meaning making process.

- Communication research is the study of patterns (Keyton, 2011). Communication and meaning are made possible through the creation of patterns. For example, languages are rule-based and construct recognizable patterns (such as sentences). Conversations have social norms of politeness to enable participants to build on each party's turns at talk; social media have unique patterns of interaction (such as the abbreviations used in text messaging on cell phones or the emoticons used in e-mail and social networks); and persuasive messages are built on patterns of communication strategies (such as advertisements showing sequences of visual appeals for destitute children to solicit donations).

- Communication research is practical knowledge construction. The field of communication is highly applied. Scholars and practitioners try to do work that matters. Work that improves the quality of people's lives, that solves problems, and that is needed. Research in the field is pragmatic. Film makers tell a story that they believe needs to be told, performance studies students create interactive scenarios to draw the audience into needed cultural discussion, and public relations practitioners conduct market analyses as a basis for planning a client's communication strategies.

- A ll research builds an argument. Whether it is a creative, rhetorical, qualitative or quantitative project, the author necessarily has a point to make. The introductory rationale for a project, the choices the researcher makes in methods selection, the interpretations offered, and the significance she or he claims for the results are all a part of building an argument. If all knowledge is socially constructed, then all research or scholarship is a persuasive process.

Whether one is doing Creative, qualitative, rhetorical or quantitative work, the methods share the above characteristics, as they are inherent in the very communication process being studied.

Research Methods

The term method refers to the processes that govern scholarly and creative work. Methods provide a framework for collecting, organizing, analyzing and presenting data. Scholars use a range of methods in Communication Studies: quantitative, qualitative, critical/rhetorical, and creative. This text focuses on the first three, but the authors note connections to creative work when relevant.

Quantitative Studies reduce data into measurable numerical units (quantities). An example would be a survey administered to determine the number of times first-year college students use social networking sites and for what purposes. Such a survey could provide general statistics on frequency and purpose of use. But, such a study also could be set up to determine if first and fourth year college students use social networks differently, or if students with smart phones spend more time on Facebook than students who rely on computers to check Facebook.

Qualitative Studies use more natural observations and interviews as data. An example would be a study about a workplace organization's leadership and communication patterns. A researcher could interview all the members of the business, and then also observe the members in action in their place of work. The researcher would then analyze the data to see if themes emerge, and if the interview and observational data results are similar. The researcher might then propose changes to the organization to enhance communication and performance for the organization.

Critical/Rhetorical Studies focus on texts as sources for data. The term texts is used loosely here to refer to any communication artifact --films, speeches, historical monuments, news stories, letters, tattoos, photos, etc. Here, the data collected is the text, and it is used by the researcher to support an argument about how the text participates in the construction of people's understanding of the world. An example would be an analysis of a presidential inaugural address to understand how the speech writers and speaker are attempting to reunite the nation after a hotly contested election and invest the new president with the powers of the office.

Creative Scholarship in the field of Communication Studies refers most often to work done in performance studies, film making, and computer digital imagery, such as Dreamweaver and Photoshop (e.g. Camp Multimedia Begins Two-Week Run ). Performance Studies is a wide umbrella term used to refer to several methods and products of scholarship. It is distinct from theater in that it is the study of performances in everyday life. It involves students in script writing, acting, and directing productions based upon oral history and ethnographic qualitative research, as well as personal experience and creative performance techniques used to tell a story more evocatively. Film Making can also include interviews, oral histories, and ethnographies, as well as learning aesthetic methods to effectively present verbal and visual images. Our colleague Karen Mitchell has used qualitative methods of interviewing and ethnography to script performances on topics from the lives of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. to romance novel readers (1996).

Communication Studies Bridges the Humanities and Social Sciences

How is it that Communication Studies as an academic field came to embrace so many different methods, given most other disciplines tend to use only one, or maybe two? The answer lies in the history of the field.

Communication Studies is different from other academic fields because it is rooted in one of the oldest areas of scholarship (rhetoric is one of the original four liberal arts) and in several of the newest areas of scholarship (such as electronic media and intercultural communication). The study of rhetoric dates back to 350 B.C.E, the time of Aristotle and the formation of democratic governance in Greece. The study of intercultural communication dates back to the 1940s and emerged out of the commerce and political needs in the U.S. after World War II (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1990). The study of the Internet took shape in the 1990s as it became a popular medium for communication (Campbell, Martin & Fabos, 2010). Because the discipline of Communication Studies includes research on all forms of communication, the method of study needs to fit as the form of communication. However, just because new forms emerge (like social media), old forms (like public speaking) do not disappear. Thus, as students, future practitioners and scholars, we need to employ a wide range of scholarly approaches. (for more about the history of the field see: Communication Scholarship and the Humanities ) .

The diverse origins of Communication Studies mean its scholars use a range of methods from the humanities (e.g., rhetorical criticism and performance) and the social sciences (e.g., quantitative and qualitative research). Both focus on the study of society, but the humanities embrace a more holistic approach to knowledge and creativity. The humanities are those fields of study that focus on analytic and interpretive studies of human stories, ideas and words (rather than numbers), and include philosophy, English, religion, modern and classical languages, and Communication Studies. When Communication Studies scholars analyze how communicative acts (like speeches or photographs or letters) create social meaning, they do so from a perspective that emphasizes interpretation.

The social sciences use research methods borrowed from previously established and recognized fields of natural science study, such as biology and chemistry. Scientific methods of knowledge construction are accomplished through controlled observation and measurement or laboratory experiments, and generally use statistics to form conclusions (Kim, 2007). The social sciences apply scientific methods to study human behavior, for example scholars use surveys to find out about people's communication patterns or create laboratory experiments to observe interruption patterns in conversation. In addition to Communication Studies, examples of other social science fields include economics, geography, psychology, sociology, and political science.

Studying human communication from the perspective of the social sciences differs in important ways from studying human communication from the perspective of the humanities. Social scientists typically are interested in studying shared everyday life experiences, such as turn-taking norms in conversation, how people build relationships through self-disclosure, and what behaviors contribute to a successful group, family or organizational culture. Social science researchers attempt to find generalizations about human behaviors based on extensive research that may be used to make predictions about that behavior. Take, for instance, research on communication in heterosexual married couples. Based on over twenty years of research, psychologist John Gottman found in 1994 he could predict with 94% accuracy which marriages will fail based on patterns of only five negative conflict behaviors among couples who ended in divorce(for updates on his work visit his website ( Research FAQs ). (Of course exceptions exist to generalizations, but for a social scientist, the exception to the rule may be ignored as an insignificant outliers, a random error.

Instead of seeking out generalizations about communication, scholars in the humanities tend to focus on the outliers, or what are considered distinctive human creations, such as Abraham Lincoln's "Gettysburg Address," Elizabeth Cady Stanton's "Solitude of Self," Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet , Lorraine Hansberry's Raisin in the Sun , Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, or Ani diFranco's "Dilate." Humanities scholars tend to focus on understanding how something happened or how someone attempted to evoke meanings and aesthetic reactions in the receivers of a message, rather than describing what occurred and predicting what will occur.

As an example of how diverse methods have been used to research a topic, consider how researchers who want to try to reduce intimate partner violence have approached the problem drawing on methods from across fields of study.

Quantitative researchers administered the National Survey on Violence Against Women and found 1.5 million women are physically or sexually assaulted by their domestic partners annually in the U.S. (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). The survey identified the difficult reality about the enormous extent of the problem. Qualitative researcher, Loren Olson (2010), wrote an autoethnography of her personal experience as a battered woman. By doing so she put a face on the problem and demonstrated a way in which she was able to reconstruct her identity after the abuse.

Performance studies scholar M. Heather Carver and ethnographic folklorist Elaine Lawless (2009) conducted a qualitative study with women who are surviving intimate violence and generated a creative performance script from their observations. The theatrical performance developed with creative methods literally help to give voice to the experiences of the women in the qualitative study, raises awareness about the problem, and may motivate audience members to address the problem in their personal or community lives.

Researchers also have critically analyzed the way domestic violence is communicated in various media. For example, Cathy Ferrand Bullock (2008) studied media framing in domestic violence news stories in Utah newspapers and rhetoric scholar Nathan Stormer (2003) studied the play, A Jury of Her Peers , to explore how collective memory is formed about acts of domestic violence. These samples of research into the complex social problem of domestic violence demonstrate how both humanities and social science approaches to scholarship are needed and valued. Because the social sciences and humanities provide different contributions to the construction of knowledge, together they create a fuller picture of a social problem or issue of study.

Given its multi-methodological research, Communication Studies is uniquely positioned to contribute to both of the two most prominent approaches to knowledge construction: humanistic and social scientific approaches. This is why, as the authors of this book, we believe Communication Studies provides a well-rounded education to prepare students to respond to the challenges and opportunities of the culturally, technologically, and economically complex 21st century.

The Interdependence of Theory and Research Methods

Whether you approach a topic of study from a humanistic or social science perspective, you will necessarily work with two-components: theory (explanations that guide or evolve from a study) and methods (application of tools to analyze texts or data). Even though the two serve distinct research functions, there is great interdependence between theory and method. Theory informs methods, and methods enable theory construction and revision.

At its essence, a theory is simply a person's attempt to explain or understand something. Individuals use theories to help make sense of their world and everyday lives. An academic theory is different from everyday theories only in the degree of rigor and research used to develop it and the depth of explanation it provides. Academic theories are more formal, with detailed explanations of the parts that make up the theory, and are usually tested (West & Turner, 2010). But as with theories for everyday life, they are subject to change and refinement. DeFrancisco and Palczewski (2007) emphasize, "A theory is not an absolute truth, but an argument to see, order, and explain the world in a particular way" (p. 27). For any topic of study, multiple theories could explain it, and research can be used to determine which theory offers the best explanation. Communication theories tend to focus on helping explain how and why people interact as they do in interpersonal relationships, small groups, organizations, cultures, nations, publics, and mediated contexts. Theories can help people understand their own and others' communication.

When you make decisions in daily life, you probably use an informal theory. You might collect some data (or try and recall what information you have), you might discard data that comes from non-credible sources, and then you might assess your options. You will likely make your assessment based on hunches or underlying assumptions you have about what makes sense. Those hunches or assumptions are a lay person's theory. They help you make sense of things and inform your decisions.

Activity Consider the following questions to determine if you use theories in your daily life:

- What is your advice for how to live on a college student's budget?

- Do you think advertising influences your purchasing decisions? If so, how?

- What is your approach to making a good first impression on a person to whom you are attracted?

- How do you know someone is attracted to you?

- Why do you think people tend to avoid relationships with others they perceive as different from them?

If you have ideas on the above topics, you are a theorist.

Now ask yourself: what do your answers to the specific questions consist of?

- Are they attempts to explain a phenomenon?

- How did you form the explanations?

- Are they based on prior experience, advice from others, and/or informal research?

Likely your answers are a little of each.

A further question to ask yourself is:

- Are other explanations possible besides the ones you developed?

Students have developed more than one way to survive on a college student's budget. For one thing, not all college students are living on a tight budget, many will survive through student loans and jobs, others may get allowances from their parents, have spouses or partners who are supporting them, etc. Some will delay gratification of purchases such as cars, I-Pads, smartphones, spring break trips, and more. Others may argue, "You only live once," and use credit cards to charge for their pleasures or life necessities. The point is people develop multiple theories for any topic of interest, and many are useful.

People develop theories through testing, academic debates, and scholarly/creative work. Natural science and social science researchers, in particular, believe that the best research is directed or driven by academic theory. This means the research methods chosen are not random but are firmly based in a credible theoretical approach that has been tested over time.

Theories often guide research. When studying presidential campaigns for example, scholars often use Thomas Burke's theories on how speakers create identification to explore the ways in which candidates create connections with their audience (Burke, 2002).

Sometimes the research will extend or challenge the legitimacy of the theory. For example, intercultural communication scholar, William Gudykunst extended Berger and Calabrese's (1975) assumed universal Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT) regarding what people do to reduce uncertainty anxiety when communicating with strangers. During 30 years of research, Gudykunst tested URT in cross cultural interactions and developed a new intercultural theory, Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) with 47 axioms or specific distinctions that help explain the universal and cultural variances he found (2005). Contrary to the original URT, Gudykunst now proclaims cultures vary in terms of comfort with uncertainty and the methods they use to manage it. These cultural differences contribute to unique cultural identities and help explain communication problems with other groups.

In the field of gender studies in communication there are countless examples of research that has disproven the commonly held theoretical assumption that universal gender differences exist between all women and men (e.g. Tannen, 1990; or in the popular press: Men are from Mars and Women are from Venice (Gray, 1992). In fact, communication scholars Kathryn Dindia and Dan Canary (2006) published a series of quantitative meta-analyses (a statistical way to control for differences across studies to directly compare the results) on just about every presumed communication difference previous researchers have studied. What did they find? While some differences were present, the variances among women's behaviors and among men's behaviors were greater than those between the sexes, and furthermore, women and men communicate in many more ways that are similar rather than different. Finally, they found that the assumption of two distinct sets of behavior is far too simplistic. It ignores the fact that people have the ability to adjust their behaviors according to situational needs and that gender identity does not affect one's behavior alone. It is also influenced by one's race, ethnic, age, nationality, sexual orientation and more.

A useful way to think of the relationship between theory and scholarly/creative work is that it is synergistic – each influences the other, almost simultaneously. As the illustration below shows, the theories selected direct the types of research questions posed to guide a study, the questions dictate the appropriate research methods needed, which then affect the results produced, which in turn contributes to theory building, thus the cycle repeats.

The General Research Process: Circular and Interdependent

Knowledge generally refers to a command of facts, theory and practical information. There is not one agreed upon approach for constructing knowledge as is illustrated in the above discussion of diverse research methods. Indeed, there is an entire field of philosophy, epistemology , which focuses on debates about how knowledge is attained. Epistemologists ask "how does one know something?" Is knowledge found or created? These are questions we encourage you to ask as you learn about the various research methods. The methods researchers use to construct knowledge are generally called methodology . The term simply means an approach being used to form knowledge is assumed to have both a theory and a method. Here again the interdependence between theory and method are evident.

Finally, throughout the research process the ability to think critically is essential. To be critical means to examine material in more depth, to peel back layers of meaning, to look beyond chunks of information to the context in which the information is presented, to look for multiple interpretations, to attempt to identify why a piece of information or perspective is important and/or not important. It requires doing a close reading or investigation of the topic of study in a more nuanced, systematic way. It does not mean to always be negative, but rather to question even common assumptions.

Research Methods Influence Results

The research methods one chooses for a study are critical. The methods will largely determine the results or what is called knowledge. The influence of methods choices is more visible when comparing social science and humanities approaches to the construction of knowledge, as will be discussed in chapter 2. The two are designed to answer different types of research questions. Together, they will offer you a wealth of methods choices.

For example, consider the relatively simple task of measuring the floor area of a room. We assigned small groups of students to measure the square footage in a room. Each group was provided different measurement tools. One group used a tape measure 12 feet long, another used a tape measure 40 feet long, another group used their own feet, and another used a metric tape measure. As you can imagine, the groups' results differed every time. Some used feet rather than inches to calculate square feet, some did not measure the same exact places in the room, metric measurements produced different results than the U.S. measuring system, and human feet produced varying results. The point here is not that one method was superior to another or that the groups made errors. The point is that even a slight change in methods can produce significant changes in results (Turman, personal communication, January 27, 2010). (If you would like to see more on metrics versus U.S. units conversion, see for example, Metric to U.S. units conversion .

If diverse results can be produced when measuring the floor area of a room, imagine how different research methods may influence the study of processes as complex as human communication. Leslie Baxter has studied interpersonal relationship development and maintenance for nearly 20 years. Most of her early research was based on quantitative surveys of romantic partners in an attempt to identify the specific tensions or stresses in their relationship. By using standardized surveys she was able to identify three dominant tensions most couples struggled with: connection/independence, openness/closedness, and predictability/spontaneity. From this she developed what is now a well known theory in the field, Dialectic Tensions Theory. However, more recently she revised her theory based on qualitative studies of relational partners' conversations. Baxter now argues that by examining tensions in actual discourse rather than surveys, she is not only able to identify common tensions, but move beyond identification to see why some relationships successfully negotiate the tensions and why others do not (2011). We offer this example not to argue qualitative methods are superior to quantitative ones, but simply to make the point that the two serve different functions.

As you will learn in the coming chapters, each method used to collect data carries with it a different implied theory about how knowledge should be, or is formed. When researchers use surveys they value the ability to solicit a larger number of people and make generalizations from the responses. When researchers analyze conversations or use interviews, they value the ability to probe individual perspectives in more depth and are less concerned with generalizations. As teachers, scholars and practitioners, the authors of this book believe a command of research methods is central to developing one's unique expertise.

Preview of Chapters

In this book, three general research approaches are included: quantitative social science research methods, qualitative social science research methods, and critical rhetorical research methods. This does not mean these three are the only approaches to knowledge construction used in the field of Communication Studies or that they are necessarily independent or opposite of each other. Communication Studies is a wonderfully diverse field of study. In addition to rhetorical methods, other humanities scholarship include performance studies and film making. Because of the extreme interdisciplinary nature of film-making and performance studies, no one research method or chapter is dedicated to them. Instead we integrate examples throughout the collection, and readers should keep in mind how such work pushes the boundaries of traditional academic fields. Below are summaries/previews of the remaining chapters in this book.

Chapter One Summary : In the present chapter, we overviewed the interdisciplinary nature of the field of Communication Studies and demonstrated how this provides a broader choice of research methods for students and faculty members in the field. We introduced basic concepts necessary to have a foundation for the study of research methods. Even though scholars use diverse research methods in the field, they are built on common premises. One is that knowledge is constructed. The way it is constructed is influenced by the theoretical approaches used and the related research methods chosen. Understanding these fundamental relationships will help students be more informed critical consumers and contributors to the field of Communication Studies, their chosen professions, and society.

Chapter Two: General Comparisons . In chapter two, we offer basic points of comparison for the research methods taught in this book. This comparison should help provide a structure to understand how the diverse methods are distinct from each other before you are introduced to the specifics of conducting research in each method in subsequent chapters. The comparison is based on the two general orientations to knowledge construction introduced in chapter one: humanistic and social scientific.

Chapter Three: Ethical Research, Writing, and Creative Work . In this chapter, we discuss the importance of researcher ethics. This chapter is placed at the front of the book to stress this importance. Regardless of the method chosen, researchers have ethical choices to make in writing honestly, citing other sources, and treating human subjects fairly. Good research is, at its core, based on ethical principles.

Chapter Four: Quantitative Methods . The first research approach presented is quantitative research methods from the social sciences. The rules involved in doing quantitative methods are very clear, with a linear research process. Reading this chapter will teach you how to plan and conduct a quantitative study, and make sense of your findings once you have collected your data.

Chapter Five: Qualitative Methods . Qualitative research methods can be placed in the middle of a continuum of research methods from the scientific to the humanistic. Qualitative methods are usually considered to be a social science approach, but in more recent years researchers have been pushing these boundaries to embrace multiple ways of knowing.

Chapter Six: Critical/Rhetorical Methods . The core assumption of rhetorical criticism is that symbolic action (the use of words, images, stories, and argument) are more than a means to transmit information, but actually construct social reality, or people's understanding of the world. Learning methods of rhetorical criticism enable you to critique the use of symbolic action and understand how it constructs a particular understanding of the world by framing a concept in one way rather than another. The more adept you become at analyzing others' messages, the more skilled you become at constructing your own.

Chapter Seven: Presenting Your Results . This chapter teaches you how to present the results of your study, regardless of the choice made among the three methods. Writing in academics has a basic form and style that you will want to learn not only to report your own research, but also to enhance your skills at reading original research published in academic journals. Beyond the basic academic style of report writing, there are specific, often unwritten assumptions about how quantitative, qualitative, and rhetorical studies should be organized and the information they should contain. In this chapter students will learn about the functions of each part of a report (e.g. introduction, methods and data description, and critical conclusion) and find useful criteria to help guide the writing of each part in a research report.

Approach to Writing this Resource Book

When the faculty in the UNI Department of Communication Studies decided to make research methods a required course for all students majoring in the department (starting Fall, 2010), we searched for a textbook that equitably covered methods used in the humanities and social sciences. We could not find one, so we decided to write our own. This resource book is the product of a collaborative effort by faculty in the department. Although five of us wrote and organized the chapters, everyone in the department was invited to contribute ideas and examples.

The result is not a traditional textbook. For one thing, rather than one voice, the authors hope you will hear their distinct voices in each chapter influenced, in part, by the methods chosen and the values these methods reflect. The differing styles should help prepare you for the differing writing styles you will find when you read original research in journals that feature quantitative, qualitative, or critical/rhetorical studies. Consequently, the citation systems we use to document sources differ across chapters. In chapters on social science research (quantitative and qualitative research methods) we use the American Psychological Association (APA) (2010) style, because it is the format of choice for most journals publishing social science research. In the chapters on ethics and rhetorical methods we use the format prescribed by the Modern Language Association (MLA) (2009) because rhetoric is rooted in the Humanities, and rhetorical research often is published in journals that also include scholarship from performance studies, English literature and the fine arts. As one reads the coming chapters, it can be insightful to attempt to identify how the methods and values are reflected in the writing styles.

Another distinction is that because the text is digital, rather than paper, we are able to make the book more interactive, including additional websites and other resources to hopefully help make the methods come alive. Perhaps most importantly for you as a student, using a digital delivery system means far less expense. The digital delivery system also means we have the ability to update material continuously.

Through this book, we hope you will become excited by the possibilities of participating in the construction of knowledge in Communication Studies. We also hope to help demystify the research process and reveal underlying assumptions of each process. Contrary to what some public figures, educators and media sources would have the public believe, most knowledge is not absolute. We invite your critical voice to this learning process.

American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Baxter, L. (2011). Voicing relationships: A dialogic perspective . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. (1975). Some explorations in initial interactions and beyond: Toward a development theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research , 1, 99-112.

Bullock, C. F. (2008). Official sources dominate domestic violence reporting. Newspaper Research Journal , 29(2), 6-22.

Burke, K. (1966). Language as symbolic action: Essays on life, literature, and method . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Burke, T. (2002). Lawyers, lawsuits and legal rights: The battle over litigation in American society . Berkeley, CA: University of California.

Campbell, R., Martin, C. R., & Fabos, B. (2010). Media & culture: An introduction to mass communication (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Carver, M. H., & Lawless, E. J. (2009). Troubling violence: A performance project . Jackson, MI: University of Mississippi Press.

DeFrancisco, V. P., & Palczewski, C. H. (2007). Communicating gender diversity: A critical approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dindia, K., & Canary, D. J. (Eds.). (2006). Sex differences and similarities in communication (2nd edition). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dues, M., & Brown, M. (2004). Boxing Plato' s shadow: An introduction to the study of human communication . Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

Gergen, K. J. (1994). Realities and relationships: Soundings in social construction . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gray, J. (1992). Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: A practical guide for improving communication and getting what you want in your relationship . New York: HarperCollins.

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of effective communication: Making the mesh of the net finer. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 281-322). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Keyton, J. (2011). Communicating research: Asking questions, finding answers (3rd ed). New York: McGraw Hill.

Kim, B. (n.d.) Social constructivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology . Department of Educational Psychology and Instructional Technology, University of Georgia. Retrieved from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/epltt/index.php?title=Social_Constructivism

Kim, S. H. (2007). Max Weber. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy . Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weber/

Korn, C.J., Morreale, S.P., and Boileau, D.M. (2000). Defining the field: Revisiting the ACA 1995 definition of communication studies. Journal of the Association for Communication Administration , 29, 40-52.

Leeds-Hurwitz, W. (1990). Notes in the history of intercultural communication: The foreign service institute and the mandate for intercultural training. Quarterly Journal of Speech , 76, 262-281.

Merriam-Webster's Word of the Year 2006. (2006). Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/info/06words.htm

Mitchell, K. S. (1996). Ever after: Reading the women who read (and re-write) romance. Theatre Topics 6.1 (1996) 51-69

The Modern Language Association. (2009). MLA handbook for writers of research papers (7th ed.). New York: The Modern Language Association of America.

National Communication Association. (2007). Communication scholarship and the humanities: A white paper sponsored by the National Communication Association. Retrieved from http://www.natcom.org/uploadedFiles/Resources_For/Policy_Makers/PDF-Communication_Scholarship_and_the_Humanities_A_White_Paper_by_NCA.pdf

Olson, L. N. (2010). The role of voice in the (re)construction of a battered woman's identity: An autoethnography of one woman's experiences of abuse. Women's Studies in Communication 27(1), 1-33. DOI: 10.1080/0749/409-2004.10162464

Stormer, N. (2003). To remember, to act, to forget: Tracing collective remembrance through "A Jury of Her Peers". Communication Studies , 54(4), 510-529.

Sunstein, C. (2001). Republic.com . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don't understand: Women and men in conversation . New York: William Morrow.

Tjaden, P. & Thoennes, N. (2000, July). Extent, nature and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. (NCJ 181867). Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/181867.pdf

Walker, L. (1979). The battered woman . New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Corpus ID: 60602524

Investigating Communication: An Introduction to Research Methods

- L. Frey , Carl H. Botan , Gary L. Kreps

- Published 5 November 1999

1,069 Citations

Communication research methods, teaching engaged research literacy: a description and assessment of the research ripped from the headlines project, methodological issues in advertising research: current status, shifts, and trends.

- Highly Influenced

Course info

Comm2201 introduction to communication research methods.

This course is an introduction to research as it relates to media and communication. Emphasis will be on the theory and practice of media and communication research. The course is intended to equip students with theoretical knowledge and practical skills needed to conduct communication research in a variety of professional and academic settings. Students who intend to pursue graduate studies in communication should be interested in this course. The course is really designed for the student who has no basic knowledge of research.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 September 2024

Robust identification of perturbed cell types in single-cell RNA-seq data

- Phillip B. Nicol 1 ,

- Danielle Paulson 1 ,

- Gege Qian 2 ,

- X. Shirley Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4736-7339 3 ,

- Rafael Irizarry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3944-4309 3 &

- Avinash D. Sahu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2193-6276 4

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 7610 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Bioinformatics

- Computational models

- Data mining

- Statistical methods

- Transcriptomics

Single-cell transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding how different cells contribute to disease progression by identifying cell types that change across diseases or conditions. However, detecting changing cell types is challenging due to individual-to-individual and cohort-to-cohort variability and naive approaches based on current computational tools lead to false positive findings. To address this, we propose a computational tool, scDist , based on a mixed-effects model that provides a statistically rigorous and computationally efficient approach for detecting transcriptomic differences. By accurately recapitulating known immune cell relationships and mitigating false positives induced by individual and cohort variation, we demonstrate that scDist outperforms current methods in both simulated and real datasets, even with limited sample sizes. Through the analysis of COVID-19 and immunotherapy datasets, scDist uncovers transcriptomic perturbations in dendritic cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and FCER1G+NK cells, that provide new insights into disease mechanisms and treatment responses. As single-cell datasets continue to expand, our faster and statistically rigorous method offers a robust and versatile tool for a wide range of research and clinical applications, enabling the investigation of cellular perturbations with implications for human health and disease.

Introduction

The advent of single-cell technologies has enabled measuring transcriptomic profiles at single-cell resolution, paving the way for the identification of subsets of cells with transcriptomic profiles that differ across conditions. These cutting-edge technologies empower researchers and clinicians to study human cell types impacted by drug treatments, infections like SARS-CoV-2, or diseases like cancer. To conduct such studies, scientists must compare single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data between two or more groups or conditions, such as infected versus non-infected 1 , responders versus non-responders to treatment 2 , or treatment versus control in controlled experiments.

Two related but distinct classes of approaches exist for comparing conditions in single-cell data: differential abundance prediction and differential state analysis 3 . Differential abundance approaches, such as DA-seq, Milo, and Meld 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , focus on identifying cell types with varying proportions between conditions. In contrast, differential state analysis seeks to detect predefined cell types with distinct transcriptomic profiles between conditions. In this study, we focus on the problem of differential state analysis.

Past differential state studies have relied on manual approaches involving visually inspecting data summaries to detect differences in scRNA data. Specifically, cells were clustered based on gene expression data and visualized using uniform manifold approximation (UMAP) 8 . Cell types that appeared separated between the two conditions were identified as different 1 . Another common approach is to use the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) as a metric for transcriptomic perturbation. However, as noted by ref. 9 , the number of DEGs depends on the chosen significance level and can be confounded by the number of cells per cell type because this influences the power of the corresponding statistical test. Additionally, this approach does not distinguish between genes with large and small (yet significant) effect sizes.

To overcome these limitations, Augur 9 uses a machine learning approach to quantify the cell-type specific separation between the two conditions. Specifically, Augur trains a classifier to predict condition labels from the expression data and then uses the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) as a metric to rank cell types by their condition difference. However, Augur does not account for individual-to-individual variability (or pseudoreplication 10 ), which we show can confound the rankings of perturbed cell types.

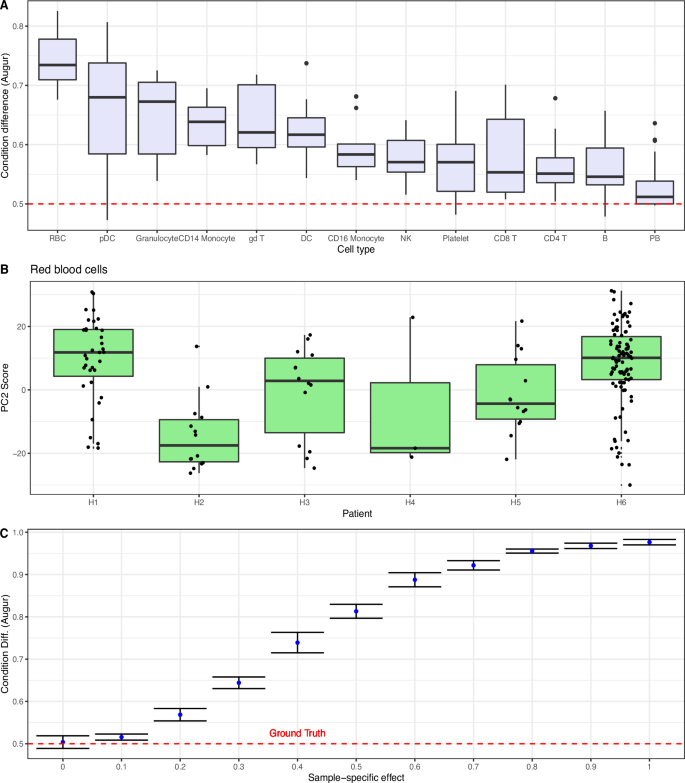

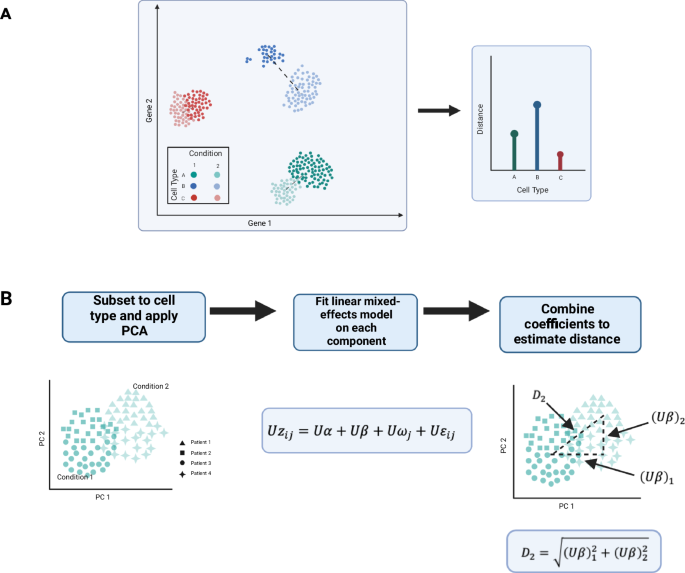

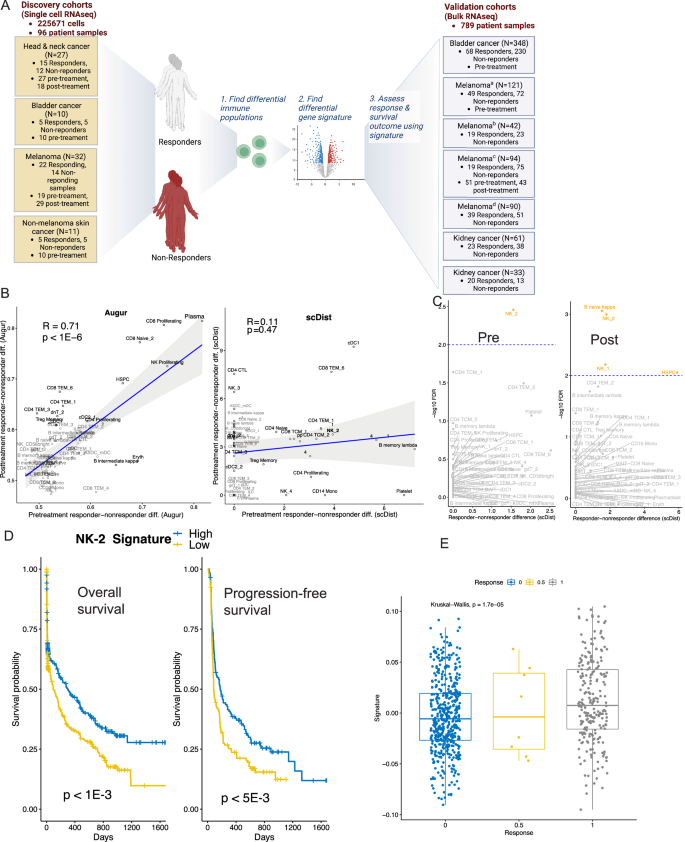

In this study, we develop a statistical approach that quantifies transcriptomic shifts by estimating the distance (in gene expression space) between the condition means. This method, which we call scDist , introduces an interpretable metric for comparing different cell types while accounting for individual-to-individual and technical variability in scRNA-seq data using linear mixed-effect models. Furthermore, because transcriptomic profiles are high-dimensional, we develop an approximation for the between-group differences, based on a low-dimensional embedding, which results in a computationally convenient implementation that is substantially faster than Augur . We demonstrate the benefits using a COVID-19 dataset, showing that scDist can recover biologically relevant between-group differences while also controlling for sample-level variability. Furthermore, we demonstrated the utility of the scDist by jointly inferring information from five single-cell immunotherapy cohorts, revealing significant differences in a subpopulation of NK cells between immunotherapy responders and non-responders, which we validated in bulk transcriptomes from 789 patients. These results highlight the importance of accounting for individual-to-individual and technical variability for robust inference from single-cell data.

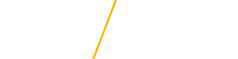

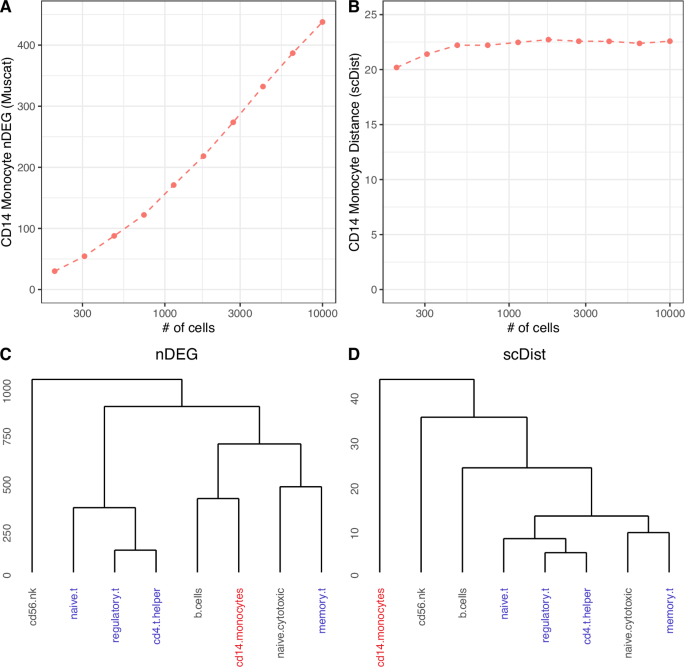

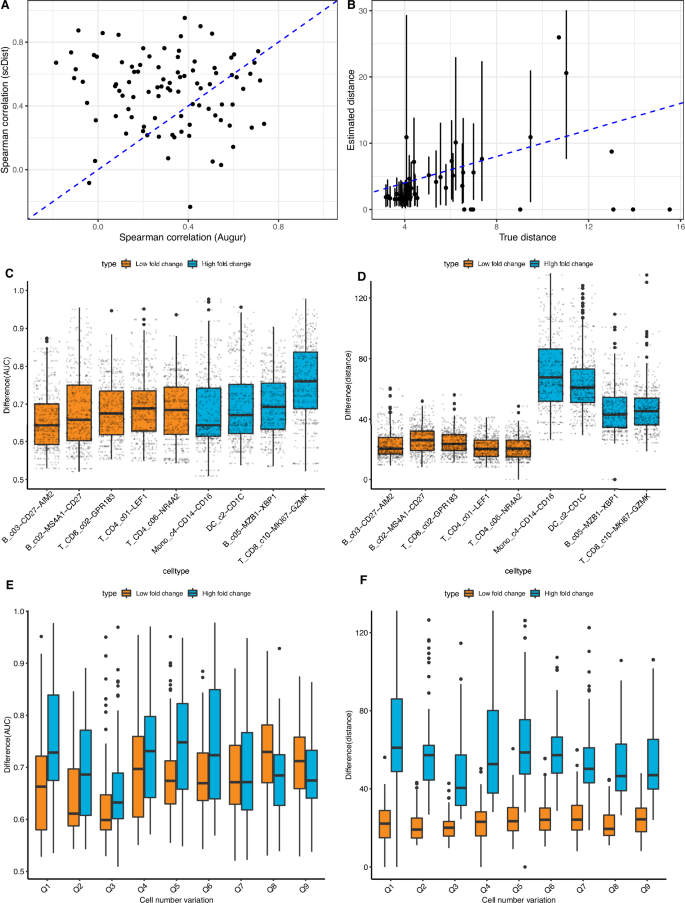

Not accounting for individual-to-individual variability leads to false positives

We used blood scRNA-seq from six healthy controls 1 (see Table 1 ), and randomly divided them into two groups of three, generating a negative control dataset in which no cell type should be detected as being different. We then applied Augur to these data. This procedure was repeated 20 times. Augur falsely identified several cell types as perturbed (Fig. 1 A). Augur quantifies differences between conditions with an AUC summary statistic, related to the amount of transcriptional separation between the two groups (AUC = 0.5 represents no difference). Across the 20 negative control repeats, 93% of the AUCs (across all cell typess) were >0.5, and red blood cells (RBCs) were identified as perturbed in all 20 trials (Fig. 1 A). This false positive result was in part due to high across-individual variability in cell types such as RBCs (Fig. 1 B).

A AUCs achieved by Augur on 20 random partitions of healthy controls ( n = 6 total patients divided randomly into two groups of 3), with no expected cell type differences (dashed red line indicates the null value of 0.5). B Boxplot depicting the second PC score for red blood cells from healthy individuals, highlighting high across-individual variability (each box represents a different individual). The boxplots display the median and first/third quartiles. C AUCs achieved by Augur on simulated scRNA-seq data (10 individuals, 50 cells per individual) with no condition differences but varying patient-level variability (dashed red line indicates the ground truth value of no condition difference, AUC 0.5), illustrating the influence of individual-to-individual variability on false positive predictions. Points and error bands represent the mean ±1 SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.