The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers

Student resources.

Welcome to the companion website for The Coding Manual for Qualitative Research , third edition, by Johnny Saldaña. This website offers a wealth of additional resources to support students and lecturers including:

CAQDAS links giving guidance and links to a variety of qualitative data analysis software.

Code lists including data extracted from the author’s study, “Lifelong Learning Impact: Adult Perceptions of Their High School Speech and/or Theatre Participation” (McCammon, Saldaña, Hines, & Omasta, 2012), which you can download and make your own practice manipulations to the data.

Coding examples from SAGE journals providing actual examples of coding at work, giving you insight into coding procedures.

Three sample interview transcripts that allow you to test your coding skills.

Group exercises for small and large groups encourage you to get to grips with basic principles of coding, partner development, categorization and qualitative data analysis

Flashcard glossary of terms enables you to test your knowledge of the terminology commonly used in qualitative research and coding.

About the book

Johnny Saldaña’s unique and invaluable manual demystifies the qualitative coding process with a comprehensive assessment of different coding types, examples and exercises. The ideal reference for students, teachers, and practitioners of qualitative inquiry, it is essential reading across the social sciences and neatly guides you through the multiple approaches available for coding qualitative data.

Its wide array of strategies, from the more straightforward to the more complex, is skilfully explained and carefully exemplified, providing a complete toolkit of codes and skills that can be applied to any research project. For each code Saldaña provides information about the method's origin, gives a detailed description of the method, demonstrates its practical applications, and sets out a clearly illustrated example with analytic follow up.

This international bestseller is an extremely usable, robust manual and is a must-have resource for qualitative researchers at all levels.

This website may contain links to both internal and external websites. All links included were active at the time the website was launched. SAGE does not operate these external websites and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. SAGE cannot take responsibility for the changing content or nature of linked sites, as these sites are outside of our control and subject to change without our knowledge. If you do find an inactive link to an external website, please try to locate that website by using a search engine. SAGE will endeavour to update inactive or broken links when possible.

Chapter 19. Advanced Codes and Coding

Introduction: forest and trees.

Chapter 17 introduced you to content analysis, a particular way of analyzing historical artifacts, media, and other such “content” for its communicative aspects. Chapter 18 introduced you to the more general process of data analysis for qualitative research, how you would go about beginning to organize, simplify, and code interview transcripts and fieldnotes. This chapter takes you a bit deeper into the specifics of codes and how to use them, particularly the later stages of coding, in which our codes are refined, simplified, combined, and organized for the purpose of identifying what it all means , theoretically. These later rounds of coding are essential to getting the most out of the data we’ve collected. By the end of the chapter, you should understand how “findings” are actually found.

I am going to use a particular analogy throughout this chapter, that of the relationship between the forest and trees. You know the saying “You can’t see the forest for the trees”? Think about what this actually means. One is so focused on individual trees that one neglects to notice the overall system of which the trees are a part. This is something beginning researchers do all the time, and the laborious process of coding can make this tendency worse. You focus on the details of your codes but forget that they are merely the first step in the analysis process, that after you have tagged your trees, you need to step back and look at the big picture that is the entire forest. Keep this metaphor in mind. We will come back to it a few times.

Let’s imagine you have interviewed fifty college students about their experiences during the pandemic, both as students and as workers. Each of these interviews has been transcribed and runs to about 35 pages, double-spaced. That is 1,750 pages of data you will need to code before you can properly begin to make sense of it all. Taking a sample of the interviews for a first round of coding (see chapter 17), you are likely to first note things that are common to the interviews. A general feeling of fear, anxiety, or frustration may jump out at you. There is something about the human brain that is primed to look for “the one common story” at the outset. Often, we are wrong about this. The process of coding and recoding and memoing will often show us that our initial takes on “what the data say” are seriously misleading for a couple of reasons: first, because voices or stories that counter the predominant theme are often ignored in the first round, and, second, because what startles us or surprises us can drive away the more mundane findings that actually are at the heart of what the data are saying. If we have experienced the pandemic with little anxiety, seeing anxiety in the interviews will surprise us and make us overstate its importance in general. If we expect to find something and we see something very different, we tend to overnotice that difference. This is basic psychology, I am sure.

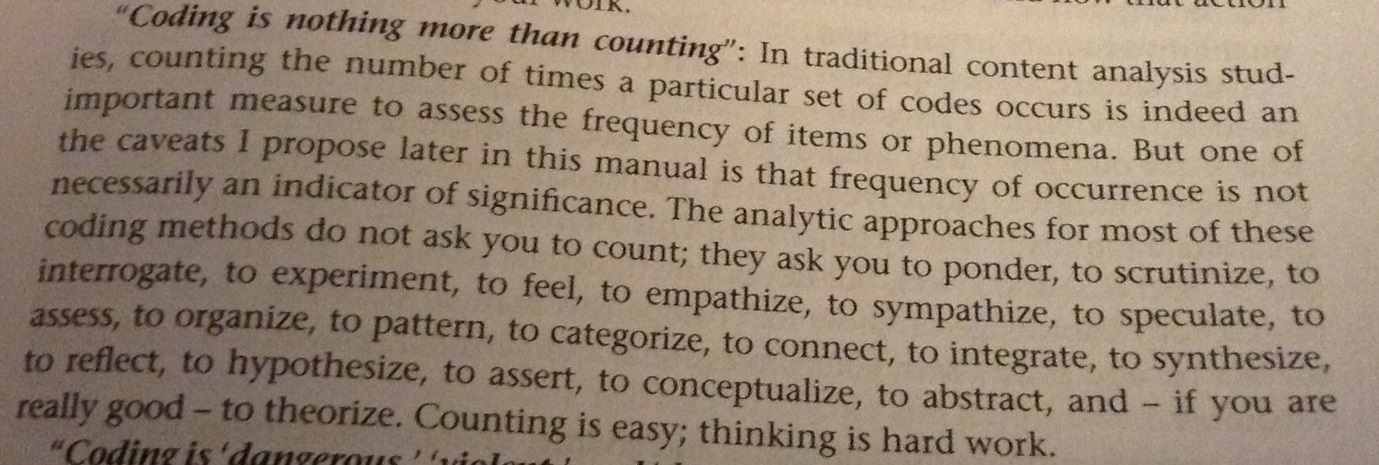

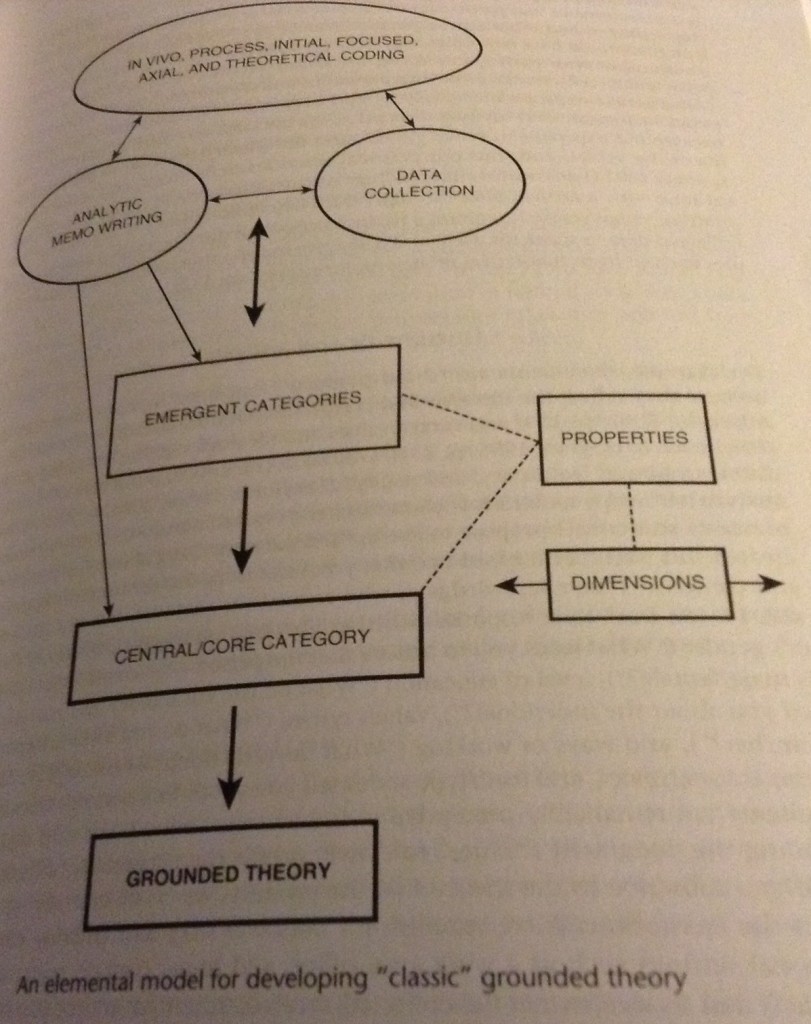

This is where coding comes in to help you verify, amplify, complicate, or delimit your initial first impressions. Coding is a rigorous process because it helps us move away from preconceptions and other judgment errors and pin down what is actually present in the data. It helps you identify the trees, which is actually important before we can properly see the forest. We start with “It’s a forest” (not really that helpful), then move to “These are specific trees, with particular roots and branches,” and finally move back to a better understanding of the forest (“It’s a boreal forest that works like this…”). Coding is the rigorous connecting process between the first (often wrong or incomplete) impression and the final interpretation, the “results” of the study (figure 19.1). If you remember that this is the point of coding, you will be less likely to get lost in the woods. Coding is not about tagging every possible root and branch of every tree to create some kind of master compendium of forest particulars. Coding is about learning how to identify what is important about that forest overall. [1] When you are new to the forest, you won’t know which root or branch is of importance, but as you walk through it again and again, you will learn to appreciate its rhythms and know what to pick up as important and what to discard as irrelevant.

There is no single correct way to go about coding your data. When I first began teaching qualitative research methods, I resolutely refused to “teach” coding, as I thought it was a little like trying to teach people to write fiction. It’s very personal and best developed through practice. But I have come to see the value of providing some guidelines—maps through the forest, if you will. I have drawn heavily here from Johnny Saldaña’s extensive and beautiful “coding manual,” but the particular suggestions here are what have worked best for me. We are going to walk through the forest many times, first in an open exploratory way and then in a more focused way once we have found our stride. Finally, we will sit down with all of our maps and materials and see what it is we can discover about the world by looking at our data.

First Walks in the Woods: Open Coding

Saldaña ( 2014 ) provides dozens of types of codes and coding processes, but we are going to confine our discussion two five. These are the five kinds of codes that I think work best for beginning researchers in your first walks through the woods. Used together, they have the potential to get at the heart of what is important in social science research. They are descriptive , i n vivo , process , values , and emotions . Select a sample of your data in the first round of coding. If you tried to tag everything in these initial rounds, you will never get out of the woods. Your sample should be broad enough to capture essential aspects of your data corpus but small enough to allow you free rein to pick up as many branches as you think interesting. Set aside a significant amount of time for this. And then double or triple that time allotment. You’ll need it.

Descriptive codes are codes used to tag specific activities, places, and things that seem to be important in particular passages. They are identifying tags (“This is a branch from an elm tree”; “This is an acorn”). Be careful here because you can really end up trying to identify everything—every word, every line, every passage. Don’t do that! It’s helpful to remind yourself what your research is about—what is your research question or focus? Some twigs can stay on the forest floor. Saldaña’s ( 2014 ) use of the term is narrower. Descriptive codes are meant to summarize the basic topic of a passage in a single word or short phrase, what is also called “topic coding” or “index coding.” These descriptive codes will allow you to easily search for and return to passages about a particular topic or feature of the forest; this will allow you to make better comparisons in later rounds of analysis. The actual word or phrase you come up with will be rather personal to you and dependent on the focus of your research. Here is an exemplary passage from a fictitious interview with a working-class college student: “I had no idea what scholarships were available! No one in my family had ever gone to college before, so there was no one I could ask. And my high school counselor was always too busy. What a joke! Plus, I was a little embarrassed, to be honest. So, yeah, I owe a lot of money. It’s really not that fair.”

What descriptive codes can be developed here? How would you define the topic or topics of this passage? On the one hand, the subject appears to be scholarships or how this student paid for college. “How Pay” might be a good descriptive code for the entire passage. But there are a lot of other interesting things going on here too. If your focus is on how peer groups work or social networks, you might focus on those aspects of the passage. Perhaps “No Assistance” could work as a descriptive code in this first round of coding. Descriptive codes are pretty straightforward, so they are easy for beginning researchers to use, but “they may not enable more complex and theoretical analyses as the study progresses, particularly with interview transcript data” ( 137 ).

In vivo codes are codes that use the actual words people have used to tag an important point or message. In the above passage, “no one I could ask” might be such a code. These indigenous terms or phrases are particularly useful when seeking to “honor or prioritize” the voice of the participants ( Saldaña 2014:138 ). They don’t require you to impose your own sense on a passage. They are also rather enjoyable to generate, as they encourage you to step into the shoes of those you have interviewed or observed. The terms or phrases should jump out at you as something salient to your research question or focus (or simply jump out at you in surprising ways that you hadn’t expected, given your research question).

Process codes are codes that label conceptual actions. This is another way to describe the data, but rather than focus on the topic, we organize it around key actions and activities. For example, we could tag the passage above with “asking for help.” By convention, process codes are gerunds , those strange verb forms that end in -ing and operate a bit like nouns. Process codes are particularly helpful for studies that focus on change and development over time, as the use of tagged gerunds can really highlight stages, if such exist. Grounded theorists often employ process codes for this reason. I find it useful, as it reminds me to focus not only on what participants say and how they say it but on the activities that they are engaged in.

Values codes are codes that reflect the attitudes, beliefs, or values held by a participant. Values codes capture things such as principles, moral codes and situational norms (“values”), the way we think about ourselves and others (“attitudes”), and all of our personal knowledge, experience, opinions, assumptions, biases, prejudices, morals, and other interpretive perceptions of the world (“beliefs”). They are extremely powerful tags and absolutely essential for phenomenological researchers. We might attach the values code “unfair” to the passage above or even note the “What a joke!” passage as disbelief or disgust.

Values codes are a particular subset of affective coding , where codes are developed to “investigate subjective qualities of human experience (e.g., emotions, values, conflicts, judgments) by directly acknowledging and naming those experiences” ( Saldaña 2014:159 ). The fifth suggested code is also another form of affective coding, emotions codes , labels of feelings shared by the participants. “Embarrassment” is an obvious emotion code in the above passage. In the kinds of research I mostly do, phenomenological and interview based, often about sensitive subjects around discrimination, power, and marginalization, coding emotions is incredibly helpful and productive: “Emotion coding is appropriate for virtually all qualitative studies, but particularly for those that explore intrapersonal or interpersonal participant experiences and actions, especially in matters of identity, social relationships, reasoning, decision-making, judgment, and risk-taking” ( 160 ).

A Final Purposeful Hike through the Forest: Closed Coding

After initial rounds of coding (several walks through the woods), you should begin to see important themes emerge from your data and have a general idea of what is important enough to look at more closely. Between first-cycle coding and your last hike through the forest, you will have created a list of codes or even a codebook that records these emergent categories and themes (see chapter 18). It is quite possible your research question(s) or focus has shifted based on what you have seen in the first rounds of coding. [2] If you need more data collection based on these shifts, collect more data. Once you feel comfortable that you have reached saturation and know what it is you are looking at and for, you are ready for one final purposeful hike through your forest to tag (code) all your data using a pared-down set of codes.

Building Meaning, Identifying Patterns, Comparing Trees, and Seeing Forests

The final cycle of coding is also the time to generate analyses of your data. As with so much qualitative research, this is not a linear process (finish stage A and move to stage B followed by stage C). To some extent, analysis is happening all the time, even when you are in the field. Journaling, reflecting, and writing analytical memos are important in all stages of coding. But it is in the final stages of coding that you truly start to put everything together—that’s when you start understanding the nature of the forest you have been walking through. That, after all, is the point. What do all these codes of various people’s actions (fieldnotes) or people’s words (interviews) tell you about the larger phenomenon of interest? This will require mapping your codes across your data set, comparing and contrasting themes and patterns often relative to demographic factors, and overall trying to “see” the forest instead of the trees.

Different researchers employ various tools and methods to do this. Some draw pictures or concept maps, seeking to understand the connections between the themes that have emerged. Others spend time counting code frequencies or drawing elaborate outlines of codes and reworking these in search of general patterns and structure. Some even use in vivo codes to generate found poems that might provide insight into the deeper meanings and connections of the data. Mapping word clouds is a similar process. As a sociologist who is interested in issues of identity, my go-to method is to look for interactions between the codes, noting demographic elements of comparison. For example, in the very first study I conducted ( Hurst 2010a ), I used emotion codes. Specifically, I found numerous examples of sadness, anger, shame, embarrassment, pride, resentment, and fear. With the exception of pride, these are not very positive emotions. I could have stopped there, with the finding of overwhelming instances of negative emotions in the stories told by working-class college students. But I played around with these categories, clustering them by incidence and frequency and then comparing these across demographic categories (age, race, gender). I found no race or gender differences and only a hint of a difference between traditional-age college students and older students. What I did find, however, was that the emotions sorted themselves out in clusters relative to other codes. Embarrassment, shame, resentment, and fear were often found together in the same interview, along with a pattern of using “they” to refer to working-class people like the interviewees’ families. Conversely, anger, sadness, and pride were often found together, along with a pattern of using “we” to refer to working-class people. This led me to develop a theory about how working-class students manage their class identities in college, with some desirous of becoming middle class (“Renegades”) and others wanting very strongly to remain identified as working class (“Loyalists”; Hurst 2010a ).

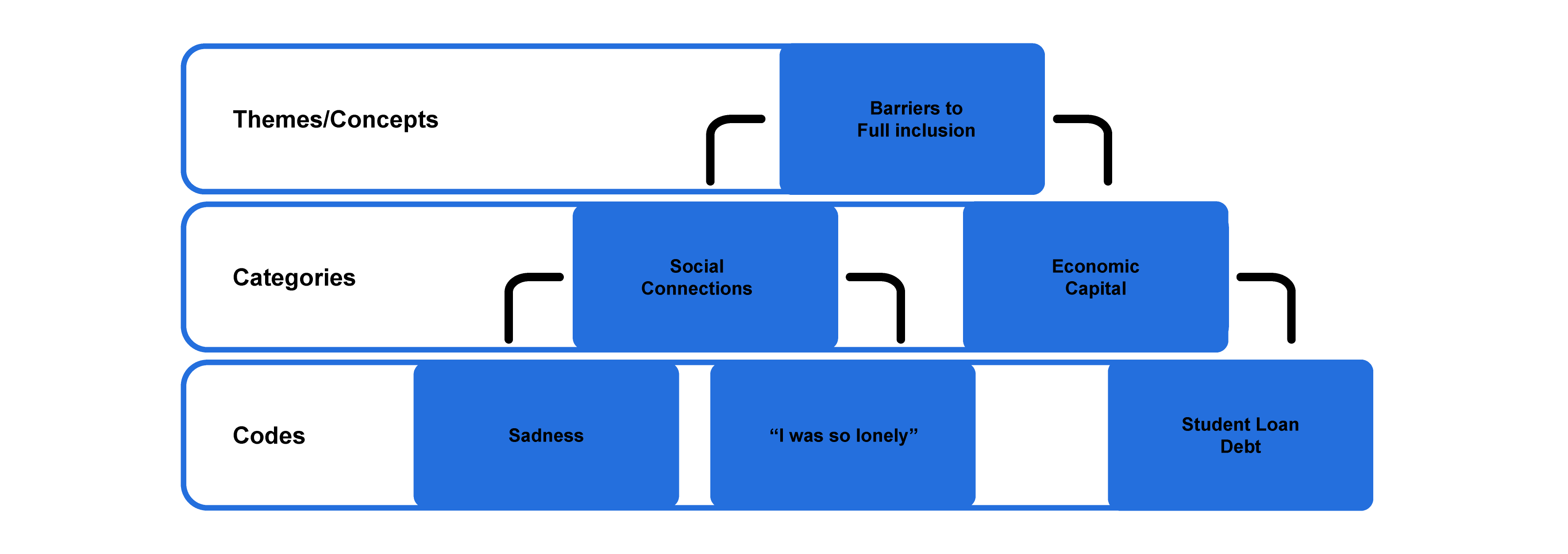

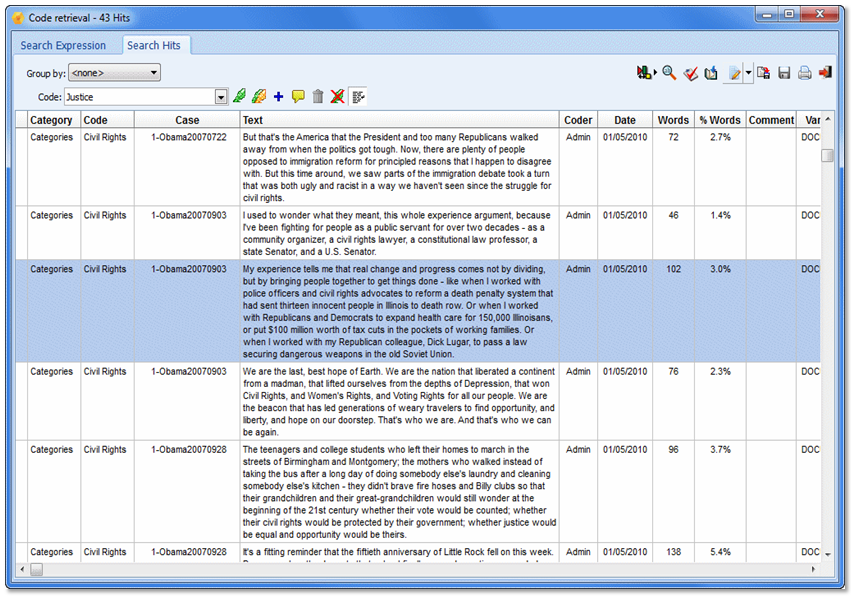

Saldaña ( 2014 ) summarizes many of these techniques. He draws a distinction between "code mapping" and “ code landscaping .” Code mapping is a systematic and rigorous reordering of all codes into an increasingly simplified hierarchical organization. One can move from fifty or so specific stand-alone codes of various types (e.g., sadness, “I was so alone,” socializing, financial aid) and attempt to impose some meaningful order on them by clustering like phenomena with like phenomena. Perhaps sadness (an emotion code), “I was so alone” (an in vivo code), and socializing (an action code) are understood as belonging together, perhaps under a category of SOCIAL CONNECTIONS or, depending on what has emerged from your data, EXCLUSION. Code mapping is an iterative process, meaning that you can do a second or a third take of simplification and reordering. In the end, you might be left with one or two big conceptual themes or patterns.

Code landscaping “integrates textual and visual methods to see both the forest and trees” ( Saldaña 2014:285 ). Using computer-assisted word cloud mapping (WordItOut.com, wordclouds.com, wordle.net) is one way of doing this, or at least a way to jump-start the process. Word clouds quickly allow you to see what stands out in the interview or fieldnotes and can suggest relationships of importance between codes. Manually, one can also diagram the codes in terms of relationship, stressing the processual elements (what leads to what: “I felt so alone” >> sadness).

Another helpful suggestion is to chart the incidence of codes across your data set. This is particularly helpful with interview data. What (simplified) codes emerge in each interview transcript? Is there a pattern here? The two categories of Loyalist and Renegade would not have emerged had I not made these kinds of code comparisons by person interviewed. You might create a master document or spreadsheet that places each interview subject on its own row, with a brief description of that person’s story (what emerges as the focus of the interview or who they are in terms of social location, character, etc.) in a separate column and then a third column listing the key codes found in the interview. This is a good way to “see” the forest in a snapshot.

Whatever method or technique is employed, the general direction is to move from simple tags (codes) to categories to themes/concepts (figure 19.2). Eventually, those identified themes/concepts will help you build a new theory or at a minimum produce relevant theoretically informed findings, as in the second example at the end of this chapter.

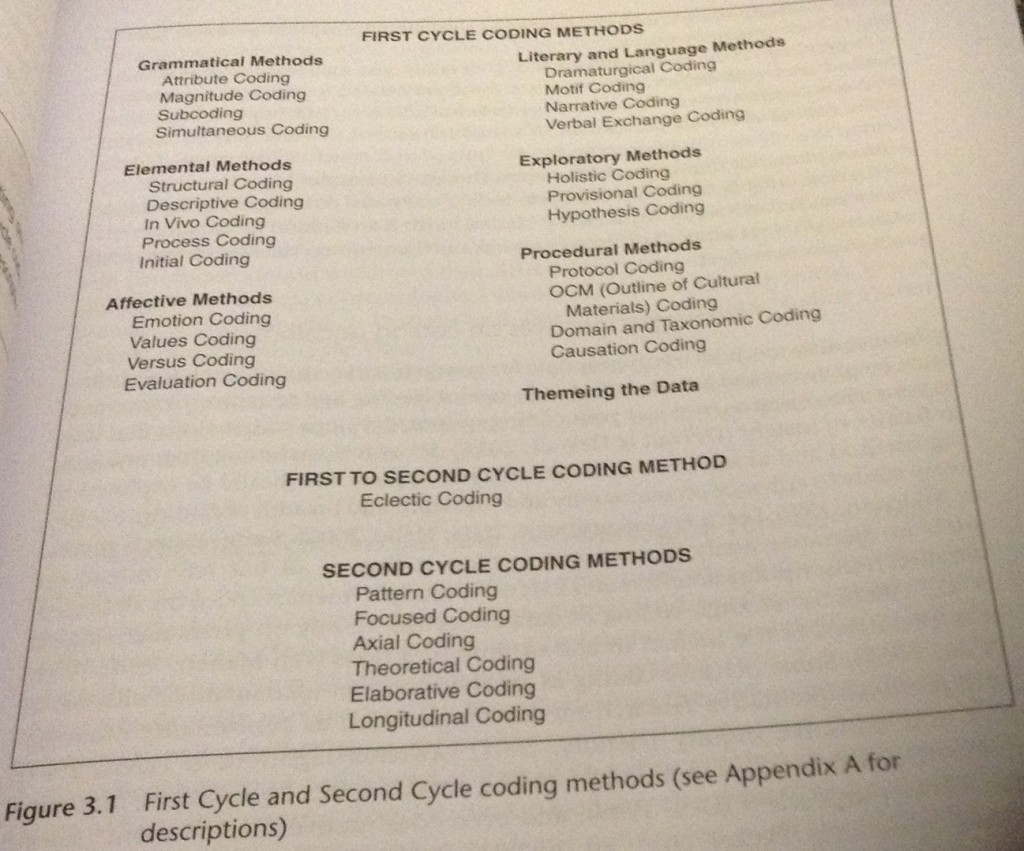

Grounded Theory has its own vocabulary when it comes to coding and data analysis, so if you are trying to do a “proper” Grounded Theory study, you might want to read up on this in more detail ( Charmaz 2014 ; Strauss 1987 ; Strauss and Corbin 2015 ). A quick summary of the approach follows. First-cycle coding employs the following kinds of codes: in vivo , process, and initial. Second-cycle coding employs focused , axial , and theoretical codes. The names of these second-cycle codes are meant to evoke the Grounded Theory approach itself: in the second cycle, the grounded theorists focus the study on axes of importance to generate theories. Focused coding pulls out the most frequent or significant codes from the first round. Axial coding reassembles data around a category, or axis. These categories or axes are meant to be concept generating: “Categories should not be so abstract as to lose their sensitizing aspect, but yet must be abstract enough to make [the emerging] theory a general guide” ( Glaser and Strauss 1967:242 ). Theoretical codes “function like umbrellas that cover and account for all other codes and categories” ( Saldaña 2014:314 ). Key words or key phrases (e.g., “Exclusion” or “Always Crying”) capture the emergent theory in the theoretical code.

Describing and Explaining the Forest: Findings and Theories

It is only now, after the laborious process of coding is complete, that you can actually move on to generate and present findings about your data. Many beginning researchers attempt to skip the middle work and get straight to writing, only to find that what they say about the data is pretty thin. The quality of qualitative research comes from the entire analytical process: open and closed coding, writing analytical memos, identifying patterns, making comparisons, and searching for order in the voluminous transcripts and fieldnotes.

But let’s say that you have followed all the steps so far. You have done multiple rounds of coding—refining, simplifying, and ordering your codes. You’ve looked for patterns. You think you have seen some master concepts emerge, and you have a good idea of what the important themes and stories are in your data. How do you begin to explain and describe those themes and stories and theories to an audience? Chapter 20 will go into further detail on how to present your work (e.g., formats, length, audience, etc.), but before we get to that, we need to talk about the stage after coding but before writing. You will want to be clear in your mind that you have the story right, that you have not missed anything of importance, and that you have searched for disconfirming evidence and not found it (if you have, you have to go back to the data and start again on a new track).

Begin with your research question(s), either as originally asked or as reformulated. What is your answer to these questions? How have your underlying goals (see chapter 4) been addressed or achieved by these answers? In other words, what is the outcome of your study? Is it about describing a culture, raising awareness of a problem, finding solutions, or delineating strategies employed by participants? Perhaps you have taken a critical approach, and your outcome is all about “giving voice” to those whose voices are often unheard. In that case, your findings will be participant driven, and your challenge will be to present passages (direct quotes) that exemplify the most salient themes found in your data. On the other hand, if you have engaged in an ethnographic study, your findings may be thick, theoretically informed descriptions of the culture under study. Your challenge there will be writing evocatively. Or to take a final example, perhaps you undertook a mixed methods study to find the best way to improve a program or policy. Your findings should be such that suggest particular recommendations. Note that in none of these cases are you presenting your codes as your findings! The coding process merely helps you find what is important to say about the case based on your research questions and underlying aims and goals.

The gold star of qualitative research presentation is the formulation of theory. Even for those not following the Grounded Theory tradition, finding something to say that goes beyond the particulars of your case is an important part of doing social science research. Remember, social science is generally not idiographic. A “theory” need not be earth shattering, as in the case of Freud’s theory of Ego, Id, and Superego. A theory is simply an explanation of something general. [3] It is a story we tell about how the world works. Theories are provisional. They can never be proven (although they can be disproven). My description of Loyalists and Renegades is a theory about how college students from the working class manage the problem of class identity when their class backgrounds no longer match their class destinations. While qualitative research is not statistically generalizable , it is and should be theoretically generalizable in this way. Loyalists and Renegades are strategies that I believe occur generally among those who are experiencing upward social mobility; they are not confined solely to the twenty-one students I interviewed in 2005 in a college in the Pacific Northwest.

What is the story your research results are telling about the world? That is the ultimate question to ask yourself as you conclude your data analysis and begin to think about writing up your results.

Further Readings

Note: Please see chapter 18 for further reading on coding generally.

Charmaz, Kathy 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Although this is a general textbook on conducting all stages of Grounded Theory research, a significant portion is directed at the coding process.

Strauss, Anselm. 1987. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. An essential reading on coding Grounded Theory for advanced students, written by one of the originators of the Grounded Theory approach. Not an easy read.

Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A good basic textbook for those exploring Grounded Theory. Accessible to undergraduates and graduate students

- A small aside here on social science in general and sociology in particular: It is often believed that sociologists are concerned about “people” and what people do and believe. Actually, people are our trees. We are really interested in the forest, or society. We try to understand society by listening to and observing the people who compose it. Behavioral science, in contrast, does take the individual as the object of study. ↵

- It might be helpful to read the first example of writings about qualitative data analysis in the "Further Readings" section. ↵

- Saldaña ( 2014 ) lists five essential characteristics of a social science theory: “(1) expresses a patterned relationship between two or more concepts; (2) predicts and controls action through if-then logic; (3) accounts for parameters of or variation in the empirical observations; (4) explains how and/or why something happens by stating its cause(s); and (5) provides insights and guidance for improving social life” ( 349 ). ↵

A form of first-cycle coding in which codes are developed to “investigate subjective qualities of human experience (e.g., emotions, values, conflicts, judgments) by directly acknowledging and naming those experiences” (Saldaña 2021:159). See also emotions coding and values coding .

A technique of second-cycle coding in which codes developed in the first rounds of coding are restructured into an increasingly simplified hierarchical organization, thereby allowing the general patterns and underlying structure of the field data to emerge more clearly.

A technique of second-cycle coding that “integrates textual and visual methods to see both the forest and trees" (Saldaña 2021:285).

A first-cycle coding process in which terms or phrases used by the participants become the code applied to a particular passage. It is also known as “verbatim coding,” “indigenous coding,” “natural coding,” “emic coding,” and “inductive coding,” depending on the tradition of inquiry of the researcher. It is common in Grounded Theory approaches and has even given its name to one of the primary CAQDAS programs (“NVivo”).

A later stage coding process used in Grounded Theory that pulls out the most frequent or significant codes from initial coding .

A later stage coding process used in Grounded Theory in which data is reassembled around a category, or axis.

A later stage-coding process used in Grounded Theory in which key words or key phrases capture the emergent theory.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Research, Digital, UX and a PhD.

A Guide to Coding Qualitative Data

Published September 18, 2014 by Salma Patel

Coding qualitative data can be a daunting task, especially for the first timer. Below are my notes, which is a useful summary on coding qualitative data (please note, most of the text has been taken directly from The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers by Johnny Saldana ).

Background to Coding

A coding pattern can be characterised by:

- similarity (things happen the same way)

- difference (they happen in predictably different ways)

- frequency (they happen often or seldom)

- sequence (they happen in a certain order)

- correspondence (they happen in relation to other activities or events)

- causation (one appears to cause another)

A theme is an outcome of coding

Questions to consider when you are coding:

- what are people doing? What are they trying to accomplish?

- How, exactly, do they do this? What specific means and/or strategies do they use?

- How do members talk about, characterise, and understand what is going on?

- what assumptions are they making?

- what do I see going on here?

- what did I learn from these notes?

- why did I include them?

- what surprised me? (To track your assumptions)

- what intrigued me? (To track your positionality)

- what disturbed me? (To track the tensions within your value, attitude, and belief systems)

Writing Analytic Memos

Gordon-Finlayson (2010) emphasises that “coding is simply a structure on which reflection (via memo writing) happens. It is memo-writing that is the engine go grounded theory, not coding”. Glazer and Holton (2004) further clarify that “Memos present hypotheses about connections between categories and/or their properties and begin to integrate these connections with clusters of other categories to generate the theory”.

The coding cycles

Depending on the qualitative coding method(s) you employ, the choice may have numerical conversion and transformation possibilities for basic descriptive statistics for mixed method studies.

First Cycle Coding

1. Grammatical Methods include

- attribute coding (essential information about the data and demographic characteristics of the participants for future management and reference)

- magnitude coding (applies alphanumeric or symbolic codes to data, to describe their variable characteristics such as intensity or frequency, example, Strongly (STR) Moderately (MOD) No opinions (NO). They can be qualitative, quantitative and/or nominal indicators to enhance description, and it’s a way of quantitizing and qualitizing data

- sub coding and simultaneous coding.

2. Elemental methods are primary approaches to data analysis. They include:

- structural coding is a question-based code that acts as a labelling and index device, allowing researchers to quickly access data likely to be relevant to a particular analysis from a larger data set. It’s used as a categorisation technique for further qualitative data analysis.

- descriptive coding summarises in a word or noun the basic topic of a passage of qualitative data.

- In Vivo Coding refers to coding with a word or short phrase from the actual language found in the qualitative data record.

- Process coding uses gerunds (“-ing” words) exclusively to connote action in the data.

- Initial Coding is breaking down qualitative data into discrete parts, closely examining them, and comparing them for similarities and differences.

3. Affective methods investigate subjective qualities of human experience (eg emotions, values, conflicts, judgements) by directly acknowledging and naming those experiences. They include:

- Emotion coding labels the emotion recalled or experienced

- Values coding assess a participant’s integrated value, attitude, and belief systems. (side note: Questionnaires and surveys such as Likert scales and semantic differentials, are designed to collect and measure a participant’s values, attitudes, and beliefs about selected subjects).

- Versus Coding acknowledges that humans are frequently in conflict, and the codes identify which individuals, groups, or systems are struggling for power.

- Evaluation Coding focuses on how we can analyse data that judge the merit and worth of programs and policies.

4. Literary and Language Methods are a contemporary approach to the analysis of Oral communication. They include Dramaturgical Coding, Motif Coding, Narrative coding and Verbal Exchange Coding, and all explore underlying sociological, psychological and cultural constructs.

5. Exploratory Methods are preliminary assignment of codes to the data, after which the researcher might proceed to more specific First Cycle or Second Cycle coding methods.

- Holistic Coding applies a single code to each large unit of data in the corpus to capture a sense of the overall contents and the possible categories that may develop.

- Provisional Coding begins with a “start list” of researcher- generated codes based on what preparatory investigation suggest might appear in the data before they are analysed.

- Hypothesis Coding applies researcher-developed “hunches” of what might occur in the data before or after they have been initially analysed.

6. Procedural Methods consist of pre- established systems or very specific ways of analysing qualitative data. They include:

- Protocol Coding is coding data according to a pre-established, recommended, standardised or prescribed system.

- OCM (Outline of Cultural Materials) Coding is a systematic coding system for ethnographic studies.

- Domain and Taxonomic Coding is an ethnographic method for discovering the cultural knowledge people use to organise their behaviours and interpret their experiences.

- Causation coding is to locate, extract, and/or infer causal beliefs from qualitative data.

Code Mapping and Landscaping

Code Mapping is categorising and organising the codes, and code landscaping is presenting these codes in a visual manner, for example by using a Wordle graphic.

Operational Model Diagramming can be used to map or diagram the emergent sequences or networks of your codes and categories related to your study in a sophisticated way.

Second Cycle Coding

Second cycle coding is reorganising and condensing the vast array of initial analytic details into a “main dish”. They include:

1. Pattern coding is a way of grouping summaries into a smaller number of sets, themes, or constructs.

2. Focused coding searches for the most frequent or significant codes. It categorises coded data based on thematic or conceptual similarity

3. Axial coding describes a category’s properties and dimensions and explores how the categories and subcategories relate to each other.

4. Theoretical coding progresses towards discovering the central or core category that identifies the primary theme of the research

5. Elaborative coding builds on a previous study’s codes, categories, and themes while a current and related study is underway. This method employs additional qualitative data to support or modify the researcher’s observations developed in an earlier project.

6. Longitudinal coding is the attribution of selected change processes to qualitative data collected and compared across time.

After Second Cycle Coding

Code weaving is the actual integration of key code words and phrases into narrative form to see how the puzzle pieces for together. Codeweave the primary codes, categories, themes, and/or concepts of your analysis into as few sentences as possible. Try writing several variations to investigate how the items might interrelate, suggest causation, indicate a process, or work holistically to create a broader theme. Search for evidence in the data that supports your summary statements, and/or disconfirming evidence that suggests revision of your statements.

From Coding to Theorising

A social science theory has three main characteristics: it predicts and controls action through an if-then logic; explains how and/or why something happens by stating it’s cause(s); and provides insights and guidance for improving social life.

The stage at which I seem to find a theory emerging in my mind is when I create categories of categories.

Use categories and analytic memos as sources of theory.

If I cannot develop a theory, then I will be satisfied with my construction of a key assertion, a summative and data supported statement about the particulars of a research study, rather than generalisable and transferable meanings of my findings to other settings and contexts.

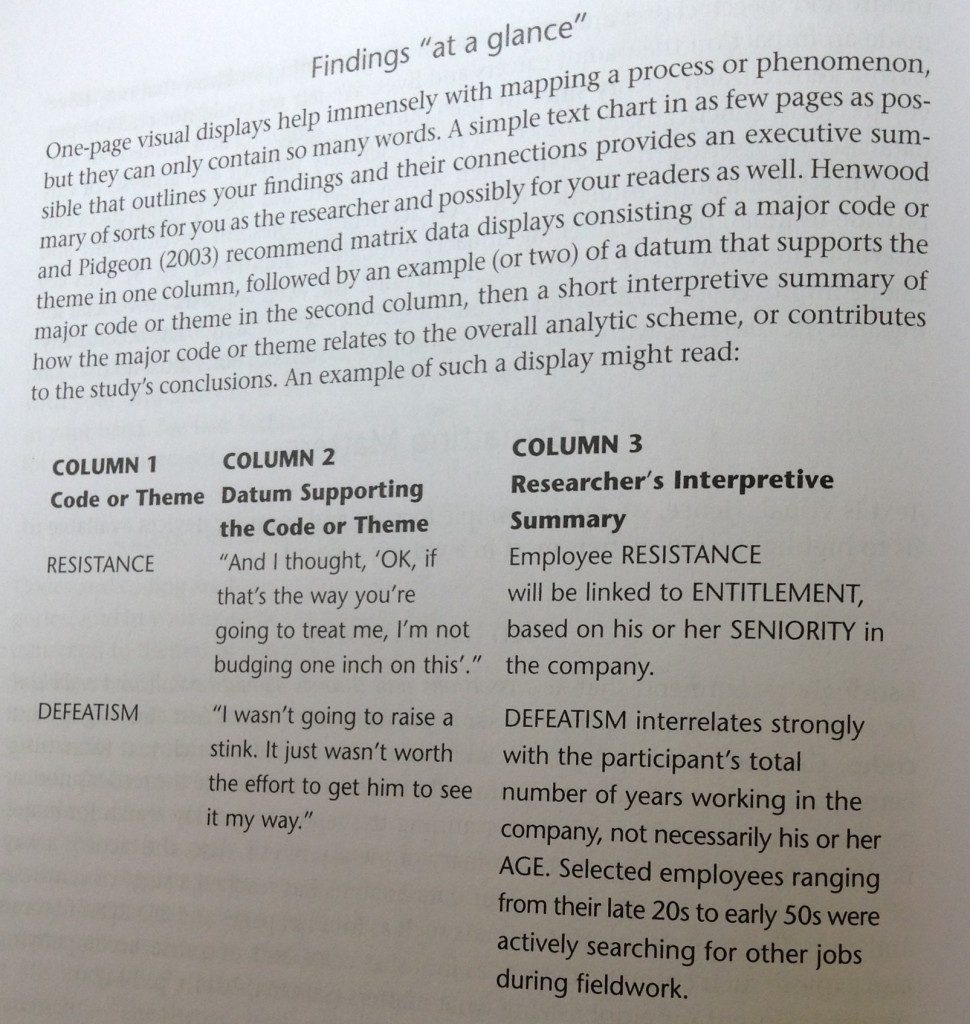

Findings at a glance can be presented as follows:

The coding journey should be noted in the analytical memos and discussed in your dissertation.

Related Posts:

- Thematic Analysis - how do you generate themes?

- Saturation in qualitative research samples

- Performance Analysis Workshop

- Notes from workshop (GDS): How to carry out basic…

- Forward Research Plan - Childminder service in public beta

Published in Headline Qualitative Research Research Methods

- coding data

- coding qualitative data

- qualitative research

- research design

10 Comments

Very helpful article. Can you please list the references you mentioned in the article? which book are you refering to explain the coding types?

Thanks. Which specific reference would you like? I can look it up in the book.

Same question. You show a number of books in the various images, none of which look familiar. Could you list/cite those resources? That would be most helpful

The reference is mentioned at the top of the article. It links to the book these images are all from. See here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/1446247376 (Sadana, 2012)

Best wishes, Salma

I also got a a question regarding the second cycle coding. Is it possible to use multiple coding forms? For example, can I code my interviews by using pattern coding, focused coding and axial coding? Or would I have to decide on one?

Yes Lara, you can use multiple coding forms. Just keep a note of it for your write up.

Thank you so much, Salma Patel, for taking the time to lay this critical and complex process out with all the illustrations. It’s so helpful to me. May your work and life continue to flourish.

thank you so much Ms. Patel

great article. thanks a lot

Great article. Very helpful! Can you point us to any examples of how researchers have coded data using some of these techniques? It would be helpful to see this in action, especially in helping understand how these different aspects of coding sit side by side in the analytical process. Thanks again!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What is Emotional Coding in Qualitative Research?

Table of Contents

Emotional coding in qualitative research: an essential guide.

Emotional coding in qualitative research is the process of identifying and categorizing emotions expressed in the data to better understand participants’ experiences. This method emphasizes the significance of emotions in shaping responses and interactions, which can provide deeper insights into the research subject. By focusing on the emotional content of the data, researchers can uncover patterns and meanings that might be overlooked with traditional coding methods.

Qualitative research relies heavily on the interpretation of text data, such as interview transcripts or open-ended survey responses. Emotional coding enhances this interpretation by revealing the underlying emotional landscape, which can be crucial for fields that study human behavior and interactions. For instance, emotional coding can help in understanding how participants feel about certain topics, which can highlight essential themes relevant to the study.

When done effectively, emotional coding adds a valuable layer of depth to qualitative analysis. Researchers can create a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of their data, leading to findings that accurately reflect the complexity of human emotions and experiences. Engaging with these emotional aspects can ultimately lead to more impactful and empathetic research outcomes.

Foundations of Emotional Coding

Emotional coding is a key method in qualitative research that helps researchers understand human emotions in data. This section explores its definition and historical development.

Definition of Emotional Coding

Emotional coding is a method used to identify and categorize emotions expressed by participants in qualitative research. This process involves labeling segments of data—such as interview transcripts or field notes—with terms that describe emotional experiences. The method is versatile and can be integrated with various qualitative approaches including grounded theory and ethnography.

According to Saldaña, emotional coding is useful for studying interpersonal experiences and actions. Emotions like joy, anger, sadness, and fear are commonly coded. This practice allows researchers to uncover deeper insights into participants’ emotional states and reactions, providing a richer understanding of the data.

History and Evolution

The concept of using emotions as data is not new. It has roots in early psychological studies where researchers like Ekman asserted that emotion is a universal human feature. Over the years, the methodology has evolved to include more systematic approaches.

Lustick (2021) developed a framework called “emotion coding” to formalize this method. This framework helps in systematically analyzing emotional content within qualitative data. Researchers have found emotional coding particularly beneficial in studies focusing on sensitive topics like discrimination and marginalization, as it allows for a nuanced exploration of participant experiences.

For more about how emotional coding has adapted to contemporary research needs, visit this comprehensive discussion on emotion coding .

Methodology in Emotional Coding

Emotional coding in qualitative research focuses on identifying, categorizing, and coding emotions to better understand the data. It requires careful attention to detail and a consistent approach to capture the depth of emotional experiences present in the analyzed materials.

Identifying Emotions

To start, researchers need to pinpoint the emotions expressed in the data. This involves reading through transcripts, field notes, or any qualitative text and noting where emotions are displayed. They may look for words or phrases that indicate feelings such as “happy,” “angry,” or “frustrated.” Non-verbal cues in interviews, such as tone of voice or body language, can also be critical indicators. Researchers aim to capture both obvious and subtle emotional expressions to ensure a comprehensive analysis.

Categorizing Emotions

Once identified, emotions should be grouped into categories. This step reduces complexity by organizing similar emotions together. For example, “joy,” “satisfaction,” and “happiness” might be listed under a “positive emotions” category, while “anger,” “fear,” and “sadness” could fall under “negative emotions.” This categorization helps in analyzing patterns and trends within the data. It is important to create clear definitions for each category to maintain consistency throughout the research.

Coding Process

The final step involves coding, where each defined emotion category is applied to relevant sections of the data. Researchers use code labels or tags to mark text segments that correspond to specific emotions. This can be done manually or with software like QDA Miner. The coding process allows for the efficient retrieval and examination of emotional patterns. It is crucial to review and refine codes regularly to enhance accuracy and reliability. The goal is to systematically track how emotions influence and shape the findings, ensuring a nuanced understanding of the research topic.

Applications of Emotional Coding

Emotional coding is used in various settings to uncover deeper insights. It is particularly useful in case studies and has specific applications in multiple industries.

Case Studies

Emotional coding sheds light on participants’ feelings and experiences in qualitative case studies. By identifying and analyzing emotional expressions, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of personal narratives and social contexts.

For example, in studies about discrimination, emotional coding can reveal how participants feel about their experiences of unfair treatment. This helps to understand the intensity and type of emotions involved, such as anger, sadness, or frustration. By using this technique, researchers can create more detailed and nuanced case studies that capture the complexity of human emotions.

In educational settings, emotional coding helps to understand students’ feelings towards learning environments. It allows researchers to see how emotions like anxiety or motivation influence learning outcomes. This approach provides a richer context for interpreting qualitative data, making it possible to devise more effective educational strategies.

Industry-Specific Uses

In healthcare, emotional coding helps in understanding patient experiences and their emotional responses to treatments. It can identify emotional triggers and stressors, which aids in improving patient care and communication.

In business, emotional coding is used to analyze customer feedback and employee satisfaction. By assessing emotions in feedback, companies can better understand customer needs and improve service quality. Employees’ emotional coding can highlight workplace issues, leading to better management practices and a healthier work environment.

In social work, this method helps to explore the emotional well-being of clients. By examining clients’ emotional responses, social workers can tailor their support strategies to address the specific needs of individuals. This approach is vital in dealing with sensitive issues such as trauma and abuse, where understanding emotions is key to providing effective support.

Society can benefit greatly from the insights provided by emotional coding across these diverse fields.

Challenges in Emotional Coding

Emotional coding offers valuable insights, but it comes with significant challenges. These include dealing with subjectivity and navigating ethical considerations.

Subjectivity Issues

One major challenge in emotional coding is subjectivity. Researchers must interpret emotions from data, which can vary greatly between individuals. Different coders might assign different meanings to the same piece of data, leading to inconsistent results.

This subjectivity can also influence the overall findings, making it difficult to ensure objectivity. Personal biases may skew the interpretation, affecting the reliability of the research.

To mitigate this, employing multiple coders and using standardized coding frameworks can help, but it’s not a foolproof solution. Training coders and encouraging regular discussions can also partially address these inconsistencies.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations play a crucial role in emotional coding. Researchers must handle sensitive data with care. Emotionally charged information can be deeply personal, and misinterpreting or mishandling it can cause harm.

Informed consent is essential. Participants must understand how their emotional data will be used. Researchers must ensure confidentiality to protect participants’ privacy. Balancing the need for detailed emotional insights with respecting participants’ boundaries is critical.

Additionally, the potential impact on researchers themselves should be acknowledged. Dealing with intense emotional data can be taxing, requiring mental health support and self-care strategies to prevent emotional burnout. Researchers must craft ethical guidelines that consider all these factors.

Advancements and Future Directions

Emotional coding in qualitative research continues to innovate through the integration of technology and the development of predictive analytic tools. These advancements aim to enhance accuracy and provide deeper insights into emotional patterns.

Technological Integration

With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, emotional coding has seen significant enhancements. Tools powered by AI can now automate parts of the coding process. For example, text analysis software can quickly identify and categorize emotions in large datasets, making it faster and more efficient.

Additionally, advancements in natural language processing (NLP) improve the detection of nuanced emotional expressions. This means AI can understand subtleties in language, such as sarcasm or mixed emotions, which can be difficult for human coders to catch consistently.

Visual and audio analysis tools also contribute to this field. Software can analyze facial expressions and vocal tones during interviews, providing a richer context for understanding participants’ emotions beyond just their spoken words.

Predictive Analysis and Trends

Another promising area is the use of predictive analytics to identify emotional trends over time. Researchers can analyze large volumes of qualitative data to forecast how emotions might evolve in certain contexts. For instance, trends in emotional responses to social issues can help policymakers develop better strategies.

By applying machine learning models, researchers can predict outcomes based on emotional patterns. This can be particularly useful in fields like marketing, where understanding future customer emotions can inform campaign strategies.

Moreover, the ability to track changes in sentiment over time allows for more dynamic and responsive research designs. This ensures that studies remain relevant and accurately reflect participants’ evolving emotional landscapes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Emotional coding in qualitative research helps identify and classify emotional expressions in data. This section covers important questions about its application, role, and differences from other types of coding.

How can emotional coding be applied in qualitative data analysis?

Emotional coding can be used to analyze interviews, focus groups, and other qualitative data. Researchers tag keywords and non-verbal cues to identify emotions. This method helps transform raw data into meaningful insights by highlighting emotional responses. More details on this can be found here .

What is the role of emotional coding within the broader spectrum of qualitative coding techniques?

Emotional coding is one method among many in qualitative research. It focuses on identifying feelings expressed in the data, adding depth to the analysis. Unlike thematic coding, which looks for patterns and themes, emotional coding zeroes in on the emotional tone and context of the responses.

How does emotional coding differ from other types of coding in qualitative research?

Emotional coding specifically focuses on emotions communicated through words, tone, and non-verbal cues. Other types, like thematic and pattern coding, concentrate on themes, patterns, or repeating ideas within the data. This unique focus allows a nuanced understanding of the emotional landscape in the research.

Can you provide a clear example of how emotional coding is used in a research study?

In a study on patient experiences in healthcare, researchers might use emotional coding to tag words like “scared” or “relieved.” Non-verbal cues like sighs or laughter might also be noted. This data helps build a picture of emotional responses to treatment, which is crucial for improving patient care.

What are the advantages of using emotional coding in analyzing qualitative data?

Emotional coding provides a deeper understanding of participants’ feelings and experiences. It can uncover hidden emotions that thematic coding might miss. This approach adds richness to the data, offering insights into how emotions influence behaviors and decisions.

How does one differentiate between emotional coding and pattern coding in qualitative research?

Emotional coding identifies specific emotions expressed in the data. Pattern coding, on the other hand, looks for recurring themes or patterns across the dataset. Emotional coding is more about the “feel” of the data, while pattern coding is about organizing it into meaningful categories.

For more examples and detailed explanations, consider reading the article on advanced coding techniques .

Supercharge the way you Process interviews

Stop wasting hours sorting through transcripts. Get straight to the insights you need.

Discover more from DialogueIQ

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >