Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The violent death toll from the Iraq War: 2003–2023

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Economics, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, United Kingdom

- Michael Spagat

- Published: February 27, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

From the beginning of the Iraq war, in March of 2003, to the present day, controversy has swirled around the death toll of the war. This paper narrows down the range of uncertainty for the numbers and trends in violent deaths in the war. I assemble and appraise all primary sources that cover the period from March of 2003 onwards—six sample surveys plus a casualty recording project (Iraq Body Count [IBC]). Data permitting, I present cumulative monthly figures with, for the surveys, 95% bootstrapped uncertainty intervals. The analysis uncovers a core of high-quality mainstream sources that are highly consistent with each another. In addition, there are three outlier surveys that are compromised by serious flaws and produce estimates far outside the mainstream. Discarding the outlying and flawed surveys reveals a clear picture of the violent death toll from the Iraq war. IBC figures, extended to include combatants, occupy a central position within the mainstream range of estimates. The strong consistency across the high-quality sources provides a rare validation of three war-death-measurement methodologies—household-based surveys, sibling-based surveys, and casualty recording. Methodological success notwithstanding, we must transcend the numbers to truly comprehend the human costs of the war.

Citation: Spagat M (2024) The violent death toll from the Iraq War: 2003–2023. PLoS ONE 19(2): e0297895. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895

Editor: Masoud Behzadifar, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

Received: July 27, 2023; Accepted: January 11, 2024; Published: February 27, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Michael Spagat. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: I am the Chair of the charity Every Casualty Counts which advocates for a practice, casualty recording, which is one of the methodologies evaluated in the paper." I now confirm that this declaration does not alter my adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

1. Introduction

The Iraq War that began in March of 2003 has long been and remains a controversial subject (e.g., [ 1 ]). Indeed, the primary objective of [ 2 – 5 ] is to estimate the number of deaths in the war and these studies have received terrific attention with, respectively, 576, 865, 243 and 185 citations (57, 112, 41 and 80 since 2019) according to Google Scholar (checked 07/01/2024). Iraq Body Count (IBC) focuses strongly on violent deaths of civilians in the war and produces no fewer than 332,000 Google Scholar results (17,800 since 2019). In short, there exists quite a substantial, longstanding and continuing interest in the death toll from the Iraq War.

The attention lavished upon the above body of work has not, however, yielded a broad consensus on the quality of the sources of war deaths let alone on the number of people killed in the war. A recent survey on the collection of population health data both before and during the war [ 6 ] praises [ 2 , 3 ], cites [ 4 ] only in passing, ignores [ 5 ] and dismisses IBC. The Costs of War Project [ 7 ], in sharp contrast, notes that [ 2 – 4 ] were controversial and bases its account of the death toll during the first 20 years of the war on IBC. These clashing treatments of the primary sources on deaths in the war are just two recent manifestations of a long-standing controversy that has sometimes been spirited (e.g., [ 8 , 9 ]).

I show in this paper that the primary sources on violent deaths in the Iraq war, including two further sources introduced below, split into a high-quality group that provides us with valuable evidence and a second incompatible group that should be dismissed. The existence of this latter group has generated considerable confusion with, for example, an article written for the 15th anniversary of the invasion characterizing the death toll as “still murky” [ 10 ]. This perceived murkiness may account for a noticeable tendency within the lessons-learned literature occasioned by the 20th anniversary of the invasion to formulate its lessons without reference to the death toll of the war (e.g., [ 11 – 13 ]).

The present paper clears up much of the confusion over the violent death toll from the Iraq war. A separate paper would be required to cover excess (including non-violent) deaths in the war although [ 14 ] already travels some distance in this direction.

The plan of the paper is as follows. The Materials and Methods section introduces the primary sources on violent deaths in the war, admitting all (and only) sources with coverage that begins from the onset of the war (March of 2003). Section 2 also explains the bases for the survey-based central estimates and 95% uncertainty intervals used in the paper. Sometimes data unavailability forces me to adopt published numbers rather than making my own calculations. However, whenever possible I produce my own central estimates with bootstrapped uncertainty intervals. Bootstrapping will yield accurate uncertainty intervals when the sample distribution mirrors the population distribution reasonably well, a condition that can fail in small samples, especially for highly skewed population distributions [ 15 ]. Therefore, for the [ 3 ] survey I provide a separate, wider, uncertainty interval derived in [ 15 ] that accounts for the skewed data collected in that small survey.

I also harmonize the estimates, to the extent possible, through two main measures. First, I use a single consistent series for the population of Iraq rather than the idiosyncratic population numbers used in each survey. Second, I extend IBC civilian-only figures to also include combatants, thus enabling me to compare like with like since none of the surveys distinguish between civilians and combatants and, therefore, they include both. The Methods and Materials section also evaluates the quality of the sources and even provides some new maps that demonstrate the poor quality of the sampling in [ 2 ]. I do raise some objections to upward adjustments made in the [ 4 ] survey however the truly serious quality problems I identify pertain just to [ 2 , 3 ] and the ORB survey (introduced below).

The Results section presents all the data, first in graphs and then in tables. These overviews effectively eliminate the “murkiness” referred to in [ 10 ]. They reveal, in particular, a clear mainstream of five highly consistent sources and an incompatible non-mainstream group of three outlier surveys that are precisely the ones that display serious weaknesses as explained in the Materials and Methods section. The truth on violent deaths in the Iraq War almost surely falls within the range spanned by the five mainstream sources that are displayed in Figs 4 and 5 below.

It is worth noting that @daponte2007 evaluated the available evidence way back in 2007, i.e., before two of the surveys covered in the present paper had been conducted and without the benefit of much of the negative evidence that eventually emerged against [ 2 , 3 ] and brought to bear in the present paper. Yet, without classifying the sources that did not exist in 2007, [ 16 ] already proposed the same grouping into reliable and unreliable sources that I advocate here.

The Discussion section summarizes and extends the main evidence and findings of the paper. By showing that three different methodologies for measuring violent war deaths have yielded measurements that are consistent with one another, the paper makes a key contribution to the field of war-death measurement. These methodologies are household-based surveys, sibling-based surveys and casualty recording as practiced by IBC (see [ 17 – 19 ]). Importantly, the validation of household-based survey methodology only works to the extent that we can distinguish properly conducted surveys from improperly conducted ones. That is, the fact that we can find specific and serious flaws in the surveys that generate the non-mainstream estimates is good news for the war-deaths-measurement field as a whole because it locates the failure of these surveys in misapplications of survey methodology rather than in survey methodology itself.

An important contribution of the paper is to resolve the extraneous uncertainty that surrounds the violent death toll in the Iraq War stemming from the misinformation spread by the deficient surveys. This clarification constitutes a big step toward a proper understanding of the consequences of the momentous decision of the US to invade Iraq and is a crucial ingredient for drawing reliable lessons about the war.

The analysis shows that the IBC numbers, extended to included combatants, are a good guide to violent deaths through the middle of 2011, i.e., during the period for which surveys are available. Moreover, IBC methodology has remained stable so IBC is likely to continue being a good guide going forward after June of 2011. The Discussion section finishes with a back-of-an-envelope attempt to quantify uncertainty surrounding these post-June-2011 IBC-extended figures.

The Conclusion section sums the paper up and suggests going beyond the numbers in order to more deeply comprehend the true human costs of the war.

2. Materials and methods

This section introduces and evaluates the primary sources on post-2003 violent deaths in the Iraq war. These are [ 2 – 5 , 20 – 22 ]. I build violent-death figures for each source that are cumulative so as to maximize the opportunities for head-to-head comparisons across the sources. The appendix to the paper provides the R code that drives the analysis.

Iraq Body Count (IBC) Extended

Here I will just sketch the IBC methodology. Readers with a strong interest should consult [ 19 , 23 , 24 ]. IBC documents violent deaths of civilians in the Iraq war using mainly media sources that are supplemented by, e.g., reports from NGO’s, morgues, hospitals and the US military. Most database entries are dis-aggregated down to the incident level but many are composite figures that aggregate across multiple events, e.g., the number of violently killed individuals who passed through the Baghdad morgue during a full month (minus the number of specifically documented violent deaths recorded for Baghdad for the same month).

I began by downloading the publicly available IBC figures from the IBC website. These core IBC figures are for civilians only but the survey-based figures, described below, to which they are compared include combatants as well as civilians. I therefore bring the core IBC figures onto a comparable basis with the surveys by adding combatant figures to the downloaded civilian ones. I take most, but not all, of these combatant numbers from annual round-ups on the war that IBC posts on its website. However, I also plug a few gaps in these round-ups with other figures, most importantly those of [ 25 ] for the first (“shock and awe”) phase of the war and those of [ 26 ] for 2017–2020 & 2022.

The end result of the data work, described in detail in the appendix, is monthly combatant plus civilian figures for the first 20 years of the war.

Iraq Living Conditions Survey (ILCS)

The ILCS survey [ 21 ] recorded (among many other things) “war-related deaths” in 21,668 households spread across 2,200 clusters. I urge readers to consult the (copyrighted) map on Page 12 of [ 27 ]. It shows the cluster locations for the ILCS matching up very well with a night-lights map of Iraq, thus demonstrating the excellent representativeness of the sample.

The ILCS published an estimate of 24,000 war-related deaths, with a 95% uncertainty interval ranging from 18,000 to 29,000, that covers a period from the beginning of the war in March of 2003 through May of 2004. There is, unfortunately, no publicly available ILCS data set for me to work with so I use these published figures.

Roberts et al. 2004 [ 2 ]

[ 2 ] recorded violent (and non-violent) deaths in 983 households spread across 33 clusters. Fig 1 displays cluster locations for the survey together with primary roads for Iraq. Publicly released data, provided in the appendix of the present paper, specifies the locations of two triples of clusters (in the governorates of Babylon and Mayson) only at the governorate level. So in Fig 1 I assigned random locations to these clusters within each governorate.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.g001

The tendency to sample close to a few primary roads is accentuated if we locate the Babylon and Mayson clusters in, respectively, the governorate capitals of Hillah and Amarah as Fig 2 does.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.g002

The fact that many clusters with well-specified locations are placed within governorate capitals lends credibility to Fig 2 as a plausible guide to all the cluster locations in the [ 2 ] survey. However, even if Fig 1 is closer to the truth than Fig 2 is it is still clear that one field team followed a northern loop running from Baghdad to Balad to Baiji to Shirqat to Mosul to Sulaimaniya to Muqdadiya to Baqubah and back to Baghdad (or vice versa) while a southern team went from Baghdad to Karbala to Hillah (with possible detours) to Rifa to Shatra to Suq Al-Shoyokh to Amarah(with possible detours) to Kut to Baghdad (or vice versa). Another team made a quick round trip to Fallujah and back to Baghdad without penetrating any deeper into Anbar governorate.

The above mapping exercise demonstrates that the 33 cluster locations of [ 2 ] are not representative of the country as a whole. Indeed, there are no clusters whatsoever in the governorates of Basrah, Qadisiyah, Najaf, Salah Al-Din, Arbil, Duhok or Al-Muthanna, which are shown in green in Fig 3 :

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.g003

This convenience sampling along a handful of primary roads is consistent with the fact that all interviews are reported to have been completed in a very short span of time between September 8 and 20 ([ 2 ], p. 1860). [ 28 ] argued that the survey of [ 3 ] (covered below) was upward biased because the final stage of its sampling scheme started with main streets which are likely to be unrepresentatively violent (“main-street bias”). A version of this critique applies with particular force at a macro level to [ 2 ] given that all of its clusters seem to have been located along the paths of a few primary roads. In short, [ 2 ] is afflicted by “primary road”, rather than “main-street”, bias. I judge this sampling bias to be severe but simply note the problem without attempting to adjust for it.

There is sufficient available data for [ 2 ] to allow me to make my own estimate of 260,000 violent deaths with a 95% (bootstrapped) uncertainty interval running from 65,000 to 640,000. This gargantuan range suggests that the primary-road-bias critique may be beside the point. The extreme factor-of-10 uncertainty surrounding the above estimate renders it as a virtual non-measurement, akin to a prediction that tomorrow’s temperature will be between -20 and 50 degrees centigrade.

Burnham et al. (2006) [ 3 ]

Gilbert Burnham, the principal researcher on the [ 3 ] survey was formally censured in 2009 by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) for refusing to disclose essential facts about the survey’s methodology. Richard Kulka, the president of AAPOR at the time, issued the following summary statement to accompany the censure:

“When researchers draw important conclusions and make public statements and arguments based on survey research data, and then subsequently refuse to answer even basic questions about how their research was conducted, this violates the fundamental standards of science, seriously undermines open public debate on critical issues, and undermines the credibility of all survey and public opinion research. These concerns have been at the foundation of AAPOR’s standards and professional code throughout our history, and when these principles have clearly been violated, making the public aware of these violations is an integral part of our mission and values as a professional organization.” [ 29 ]

Moreover, [ 30 ] presents evidence of data fabrication and ethical violations in the [ 3 ] survey. Burnham’s university, Johns Hopkins, did not investigate the data fabrication evidence but did launch an investigation into the ethics of the project which led to the suspension of Gilbert Burnham because he collected unique identifiers for his interviewees despite obtaining light-touch review from his IRB by promising not to collect unique identifiers [ 31 ]. [ 16 , 32 ] also found serious shortcomings in the survey.

Despite these shadows that hang over the [ 3 ] survey, I include it in the present paper so that readers can place its ostensible findings within the context of all the primary evidence on violent deaths in the Iraq War. This bird-eye view reveals the violent-death estimates based on this survey to be extreme outliers.

[ 3 ] reportedly interviewed 1,849 households spread over 47 clusters about violent (and non-violent) deaths from the beginning of the war through June of 2006. One cluster, nonetheless, lists no fewer than 24 violent deaths in July of 2006, a month outside the coverage period for the survey. [ 3 ] includes these out-of-range deaths in the paper’s estimates and I follow this lead for my estimates. However, some readers may wish to subtract about 50,000 July-2006 deaths from my estimates to compensate for this coverage-period anomaly.

I am able to make monthly central estimates based on the data of [ 3 ], a level a detail that is not possible for the [ 21 ] or the [ 2 ] surveys. However, I can only construct an uncertainty interval around the central estimate for the whole time period covered by the survey because this is the only period for which I have cluster-by-cluster data. My central estimate for the whole period is 670,000 with a 95% uncertainty interval running from 440,000 to 940,000.

[ 15 ] point that [ 3 ] have a small sample for which the distribution of violent deaths by cluster is highly skewed. They argue that bootstrapped uncertainty intervals are, therefore, likely to be too narrow. They propose a special methodology for calculating uncertainty intervals in such cases which, when applied to the [ 3 ] data results in a 95% uncertainty interval running from 293,339 to 988,101 (rounded to the nearest 10,000). We will use both this interval and the bootstrapped on below.

Iraq Family Health Survey (IFHS)

The IFHS interviewed 9,345 households spread over 971 clusters and published a violent-death estimate covering the beginning of the war through June of 2006 in [ 4 ]: 151,000 with a 95% uncertainty interval running from 104,000 to 223,000.

The time period covered by the IFHS is identical to that of [ 3 ], aside from the latter’s July 2006 anomaly. Yet, the bottom of the bootstrapped 95% uncertainty interval for [ 3 ] is nearly twice the top of the 95% uncertainty interval for [ 4 ] and even the bottom of the [ 15 ] uncertainty interval does not overlap with the IFHS one. So at least one of the two surveys must badly mis-measure the number of violent deaths in the Iraq War for this common period. The obvious candidate to be wrong is [ 3 ], given the evidence of fabrication, non-transparency over its methods and ethical violations that suggest lack of control over the field work.

Yet there are two reasons to believe that even the [ 4 ] survey overestimated violent deaths; correcting these problems would pull it even further below the [ 3 ] estimates. First, [ 4 ] uses the following weak argument to multiply what would have been a conventional survey-based violent-death estimate by more than a factor of 1.6:

“In general, the underreporting of deaths is likely to be common in household surveys. The most serious concern is household dissolution after the death of a household member. Several demographic assessments have suggested that there has been an underreporting of deaths in the IFHS. The application of the growth balance method, 7 with the use of the age distribution of deaths in the population obtained from the household roster, indicates that the level of completeness in the reporting of death was 62%. However, this estimation needs to be interpreted with caution, since a basic assumption of the method—a stable population—is violated in Iraq. Furthermore, the comparison is not made to a rate of death derived from two successive censuses, as is usually done, but from the age distribution of the households in the IFHS.”

Moreover, this large upwards adjustment, aptly labelled an “arbitrary fudge” [ 33 ], is applied on top of an earlier adjustment to account for clusters that were selected for interviews but were not ultimately included in the sample because of security concerns that arose during the field work. The motivation for the missing-cluster adjustment is much stronger than the motivation for the factor-of-1.6 adjustment. However, the specific adjustment that is applied assumes that missing clusters in Baghdad were roughly four times as violent as the completed clusters throughout the whole course of the war. This big adjustment is justified on the ground that it brings the IFHS ratio of Baghdad deaths to deaths in a basket of relatively peaceful governorates into rough equality with the same ratio for IBC. However, this adjustment will be excessive to the extent that IBC is relatively better at recording Baghdad deaths than it is at recording deaths outside of Baghdad.

The two upward adjustments combined roughly double the violent-death estimate of [ 4 ]. It is probably going too far to totally eliminate both of them but, at a minimum, awareness of their existence should make us cautious about the adjusted IFHS estimate. In the tables and graphs below I include both adjusted and unadjusted IFHS figures although I cannot produce uncertainty intervals for the unadjusted ones. As always, the appendix provides details including R code.

Opinion Research Business (ORB) Survey

The internet no longer contains primary material on the ORB survey so the best way to learn about it is through a critique, reply and rejoinder published in Survey Research Methods [ 34 , 35 ].

ORB initially announced in October 2007 that they had interviewed 1,499 people spread across an undisclosed number of clusters and made an estimate of 1,229,580 violent deaths with a range of 733,158 to 1,446,063 covering a period from the beginning of the war through August 2007. In January 2008 ORB announced that it had done further rural sampling and that:

“… we now estimate that the death toll between March 2003 and August 2007 is likely to have been of the order of 1,033,000. If one takes into account the margin of error associated with survey data of this nature then the estimated range is between 946,000 and 1,120,000.” ORB (2008a)

ORB added that this estimate was based on 2,163 interviews spread over 112 “sampling points”, i.e., clusters. Note that the published range cannot be a proper 95% uncertainty interval, given the small number of clusters in the sample.

There are remarkable anomalies in the ORB survey which emerge when it is placed between two other ORB surveys conducted in Iraq before and after the one that yielded the estimate of 1 million violent deaths [ 34 ]. The before and after surveys supposedly ask about deaths of family members whereas the middle survey (responsible for the 1 million estimate) supposedly asks about deaths within households . Household is a much narrower category than family, the latter of which can include brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, etc., all people who might not live within the immediate household. Sensibly, in southern governorates the fraction of interviewees that reported violent deaths decreased by a factor of 5 in the middle survey compared to the first one. However, in four central governorates that account for about 80% of the estimated 1 million deaths the fraction of respondents reporting deaths in the middle, supposedly household-based survey, is substantially higher than the fraction reporting deaths in the first, supposedly family-based, survey. The third survey delivers a further blow to the credibility of ORB’s work in Iraq; interviewers supposedly switch to asking about families again but the fractions reporting deaths are roughly equal in the South for the middle and third survey.

In short, ORB’s Iraq work is not credible. Nevertheless, I still include it in the present paper, again to place it into perspective. I use ORB’s published figures since ORB has not released the data that I would need to make an independent estimate.

University Collaborative Iraq Mortality Study (UCIMS)

The UCIMS, written up in [ 5 ], is by far the best of the surveys according to the criterion of data openness. I am able to make monthly UCIMS-based violent-death estimates complete with 95% bootstrapped uncertainty intervals. Moreover, I can make a second set of estimates based on the sub-category of reported deaths that were backed by death certificates. Still better, I can make separate monthly violent-death estimates with 95% bootstrapped uncertainty intervals based on a different module in the survey’s questionnaire that asks about deaths of siblings rather than deaths of household members.

The UCIMS interviewed 1,976 households spread across 100 clusters about violent (and non-violent) deaths from the beginning of the war through June of 2011. My central estimates for violent deaths for this whole period are 200,000, 140,000 and 140,000 based on, respectively, all reported violent deaths within households, only within-household deaths backed by death certificates and reported violent deaths of siblings. The 95% uncertainty intervals for the three estimates are, respectively, 140,000 to 270,000, 100,000 to 180,000 and 110,000 to 180,000. I give the above estimates for orientation but the graphs of the next section show cumulative estimates with uncertainty intervals for every month covered by the survey. Note that [ 5 ] did not publish a proper violent-death estimates based on the household module of their survey but they did publish a central estimate of 132,000 with a 95% uncertainty interval of 89,000 to 174,000 based on the sibling module, numbers that are fairly close to my sibling-based estimates. As always, the details are in the appendix.

Graphical comparisons

Fig 4 shows cumulative figures covering the first 20 years of the war for IBC, ILCS, [ 2 , 3 ], IHFS-adjusted, ORB, UCIMS-household (accepting all reported deaths regardless of death-certificate backing) and UCIMS-sibling. I show all data at the lowest possible level of aggregation, down to the month level if possible. The picture also displays 95% uncertainty intervals. For [ 3 ] I show both my bootstrapped interval (the narrower one) and the [ 15 ] interval (the wider one). I use shading for the two UCIMS-based estimates and line segments otherwise.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.g004

The violent-death estimates for the Iraq war divide into two groups. Group 1 consists of the ILCS, IFHS-adjusted, UCIMS (household and sibling) and IBC-extended. None of these sources are above criticism, of course, and I did suggest that at least part of the upward adjustment made to the IFHS in [ 4 ] went too far. However, none of them have glaring deficiencies comparable to those of the group-2 surveys: [ 2 , 3 ] and the ORB survey. The latter the three surveys are the ones identified as particularly problematic in the previous section: [ 2 ] for sampling just along a few primary roads and a terrifically wide uncertainty interval, [ 3 ] for non-transparency, data fabrication and ethical violations and ORB for discrediting irregularities across multiple surveys. Recall, moreover, that the ILCS has by far the biggest sample of all the surveys and the figure on page 12 of [ 27 ] demonstrates that this sample represents the population of Iraq well.

Fig 5 shows just the group-1 sources and uses the unadjusted IFHS figures along with the version of the UCIMS-household figures that require death-certificate verification for each death. Again, all figures are cumulative and I show 95% uncertainty intervals where possible, using either line segments or shading (for the UCIMS). These five sources, different in two cases from the group-1 sources in Fig 4 , continue to tell a consistent story.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.g005

Tabular comparisons

I turn to tables in the present sub-section for two main reasons. First, the pictures in the previous sub-section are challenging to read in areas where there are multiple estimates and uncertainty intervals in close proximity to each other. Second, the tables contain information on the bootstrap runs that is not present in the pictures in the previous sub-section.

All tables present cumulative figures that cover periods from the beginning of the war in 2003 and stop at the following endpoints: April 2004, September 2004, May 2005, June/July 2006 and August 2007. These endpoints are dictated by the periods covered by the various surveys.

Table 1 gives central estimates and 95% bootstrapped uncertainty intervals, when possible, together with the IBC-extended number for violent deaths in the Iraq War from March 2003 through April 2004. It also provides the maximum estimate over 10,000 bootstraps whenever bootstrapping is possible; this is new information that was not in the graphs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.t001

There is a mainstream of six sources with central estimates ranging between 16,000 and 32,000 violent deaths and no instances of the bottom of a 95% uncertainty interval coming remotely close to exceeding the top of another interval within this mainstream. I classify the IFHS adjusted estimate as “on the edge” because the bottom of its 95% uncertainty interval is close to exceeding the tops of three of the intervals that are within the mainstream. I classify [ 3 ] as outside the mainstream because its central estimate for the period exceeds by wide margins even the maximum bootstrap outcomes in all cases for which bootstrapping is possible.

Table 2 covers the period from the beginning of the war through September of 2004. The central estimate for [ 3 ] is, again, well above the highest of 10,000 bootstrap estimates whenever bootstrapping is possible. The central estimate for [ 2 ] is very much higher than even the [ 3 ] estimate although the 95% uncertainty interval for the former estimate is so wide that it almost reaches down as far as the central estimate for the UCIMS household survey when all reported deaths, regardless of death-certificate confirmation, are included.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.t002

Table 3 presents all the available evidence covering the period from the beginning of the war through May of 2005. This time I have placed the adjusted IFHS estimate within the mainstream since its central estimate is substantially closer to the mainstream than was the case in Table 1 . [ 3 ], on the other hand, is even further outside the mainstream than it was in Table 1 with a central estimate more than double the largest bootstrap estimate obtained within the mainstream.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.t003

Table 4 covers the period from the beginning of the war through the middle of 2006. Now I am able to do bootstrapping for [ 3 ], revealing that even the bottom of its 95% uncertainty is more than double the largest bootstrap simulation within the mainstream. Even the bottom of the exceptionally wide uncertainty interval of [ 15 ] still exceeds the top of the IFHS interval by 60,000 deaths. In fact, the minimum bootstrap estimate for [ 3 ] is 270,000, a number that exceeds the maximum bootstrap estimate for the mainstream sources by 70,000 deaths. In short, there is radical incompatibility between [ 3 ] and the mainstream.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.t004

Finally, Table 5 displays the available information for the period from the beginning of the war through August of 2007.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.t005

To summarize, the tables support the idea that there is a mainstream of estimates that extends from the household-based UCIMS estimates that count only deaths backed by death certificates up to the adjusted IFHS estimates. These are the sources designated as group 1 in the previous section.

For periods of the Iraq war covered by one of the above tables it is likely that the true number of violent deaths lies within or near to the mainstream figures shown in the tables. It is bad practice to cite just a single figure for any period but, if forced, I would choose the IBC-extended number which is always at the heart of the mainstream. After June of 2011 we are left with only the IBC-extended figures. Based on the consistent progression of IBC-extended through the middle of the group-1 surveys during the periods covered by the surveys and the fact that IBC did not change its methodology after 2011 I would suggest that IBC-extended remains a good guide to the violent death toll of the war after June of 2011.

4. Discussion

The present paper provides a rare validation for three different methodologies: household-based survey estimation [ 4 , 5 , 21 ], sibling-based survey estimate [ 5 ] and casualty recording (IBC). The only comparable validation I am aware of is [ 36 ] which finds strong consistency between three accounts of violent deaths in the Kosovo war that use three different methodologies. These methodologies included a household survey and a casualty recording project so this Kosovo validation enhances confidence in the results of the present paper. More such validations in the future would enhance confidence both in the results of the present paper and in the methods used for measuring violent war deaths.

Discussions of the death toll in the Iraq war have long been complicated and confused by the presence of a parallel universe of outlying estimates (group 2) that are inconsistent with the mainstream universe (group 1). But this confusion evaporates once we discard group 2, a move that is supported both by quality assessments of the sources and the weirdness of the numbers. Indeed, if there were not serious and identifiable shortcomings in the group-2 surveys we would have to acknowledge the methodology of survey-based measurement of war deaths to be unreliable to the point of unusability. Similarly, we would have to discard a body-temperature-measuring device if, when used as intended, can measure 100 degrees one moment and 90 degrees the next. Thus, the credibility of the survey methodology for measuring violent war deaths hinges on our ability to separate improper applications of the methodology from proper ones. Fortunately, it turns out that we are able to do this.

The present paper clears up extraneous uncertainty over violent deaths in the Iraq war between March of 2003 and June of 2011 when we have not only the IBC-extended numbers but also good surveys using multiple methods and treatments, e.g, household vs. sibling, adjusted versus unadjusted and many time periods. Nevertheless, considerable uncertainty remains which we have quantified through 95% uncertainty intervals for individual surveys when these exist. Yet each such uncertainty interval is calculated in isolation from the other group-1 evidence, thereby ignoring the great consistency across these sources and probably exaggerating the remaining uncertainty.

IBC is the sole remaining source covering the whole country after June of 2011. We cannot, therefore, cross validate the IBC-extended numbers for the post-June-2011 period as we did for the pre-June-2011 period. Nevertheless, the analysis of the paper consistently locates IBC-extended squarely within the range of the mainstream sources when group-1 surveys exist and IBC methodology did not change in July of 2011. So it is reasonable to accept the IBC-extended numbers as a good guide to the post-June-2011 violent death toll in the war.

The absence of post-June-2011 surveys imposes the further cost of denying us an obvious basis for quantifying the uncertainty surrounding the IBC-extended figures as these are not sample-based estimates. I cautiously fill this gap with a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the following observation. During the pre-June-2011 period, i.e., when there are surveys, we have 95% confidence intervals surrounding these surveys. The IBC-extended figures go right through the middle of the central estimates of these surveys so we can take the uncertainty intervals surrounding the survey central estimates as characterizing the uncertainty around the IBC figures up until June-2011. I then project this uncertainty forward. The ratios of IBC-extended figures to the central estimates for each treatment of the group-1 surveys for the whole time period covered by each survey are 0.83, 0.86, 0.87, 0.94, 1.2 and 1.9 for, respectively, UCIMS-household requiring death certificate backing, UCIMS-sibling, ILCS, IFHS-unadjusted, UCIMS-household including all violent deaths and IFHS-adjusted. These numbers lead to the following tentative conclusions about the human cost of the first 20 years of the war; 1. The IBC-extended figures, roughly 200,000 violent deaths might be 20% higher than the true numbers of violent deaths: 2. The true numbers of violent deaths might, at a stretch, be twice the IBC-extended Fig 3 . The mean of the above ratios is 1.1 while the median ratio is 0.91 so the preponderance of evidence points toward the IBC-extended figures being about right.

Although I have drawn some fairly strong conclusions from the analysis it is important to review the main limitations of this study which divide broadly into issues with the quantity and the quality of the data. On the quantity issue, I note that more data, especially after 2011, would be welcome as we have only Iraq Body Count after that. But more pre 2011 data would also be welcome.

The main quality issue concerns the extreme unreliability of the (Roberts et al. 2004), (Burnham et al. 2006) and ORB estimates. Much effort in the paper is required to dispel the misinformation created by these works. However, quality issues are not confined to these surveys. For example, all field teams worked under time pressure because they were operating in time of war and the Iraq Family Health Survey even had to abandon some of its clusters due to security problems. A further issue is that several of the surveys have not made their data available.

5. Conclusion

The above analysis validates the choice of the Costs of War Project [ 7 ] to use IBC as the basis for its quantification of the human cost of the Iraq War and to give short shrift to the group-2 surveys favored by [ 6 ]. Such quantification projects must work with the best available evidence and should not squander their credibility through exaggeration as, e.g., [ 37 ] do with their estimate of 2.4 million deaths in the Iraq war with a range of 1.5 million to 3.4 million.

Inevitably, some scientific papers are wrong and public trust in science requires that these errors are exposed and discarded. The existence of dueling survey-based estimates of violent deaths in the Iraq war has damaged the credibility of the field while the present paper should help to restore some of this precious commodity. Transparency is a central ingredient to the scientific vetting process, and I have relied on the availability of some, alas not all, of the crucial data in writing the present paper. Hopefully, the field of war-death estimation will move toward greater transparency in the future so that more work along the lines of the present paper will be possible.

[ 38 , 39 ] argue that good quantification is important yet inadequate to the task of illuminating the horror of warfare. They advocate telling the stories of the many individual victims who lie beneath the abstract numbers. [ 19 ] does precisely this, telling the stories of many of the individuals whose deaths are incorporated into the IBC database. The present paper’s validation of IBC data can only enhance the value of this work because it shows that [ 19 ] provides, broadly, an overview of the stories of all victims in the war.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297895.s001

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Michael Robbins for useful feedback on this paper.

- 1. Draper R. To start a war: How the bush administration took america into iraq. Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Books; 2021.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 12. Kori schake on how america has moved beyond the debacle of the iraq war. The Economist. Available: https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2023/03/22/kori-schake-on-how-america-has-moved-beyond-the-debacle-of-the-iraq-war .

- 17. Every casualty counts. Available: https://everycasualty.org/ .

- 19. Hamourtziadou L. Body count: The war on terror and civilian deaths in iraq. 1st ed. Bristol University Press; 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv19j7568

- 20. Iraq Body Count Database. Iraq body count database. Available: https://www.iraqbodycount.org/database/ .

- 21. Programme UD, ReliefWeb. Iraq Living Conditions Survey 2004; Volume II. 2005. Available: https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2024352.html .

- 22. ORB survey of Iraq War casualties. 2022. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=ORB_survey_of_Iraq_War_casualties&oldid=1105674823 .

- 23. Methods:: Iraq body count. Available: https://www.iraqbodycount.org/about/methods/ .

- 24. Sloboda J, Dardagan H, Spagat M, Hsiao-Rei Hicks M. Iraqi body count: A case study in the uses of incident-based conflict casualty data. In: Seybolt TB, Aronson JD, Fischhoff B, editors. Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 0. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199977307.003.0004

- 26. UCDP home page. 2022. Available: https://ucdp.uu.se/ .

- 27. Iraq Living Conditions Survey 2004—Iraq | ReliefWeb. 2005. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-living-conditions-survey-2004 .

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

A careful rethinking of the Iraq War

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

The term “fog of war” expresses the chaos and uncertainty of the battlefield. Often, it is only in hindsight that people can grasp what was unfolding around them.

Now, additional clarity about the Iraq War has arrived in the form of a new book by MIT political scientist Roger Petersen, which dives into the war’s battlefield operations, political dynamics, and long-term impact. The U.S. launched the Iraq War in 2003 and formally wrapped it up in 2011, but Petersen analyzes the situation in Iraq through the current day and considers what the future holds for the country.

After a decade of research, Petersen identifies four key factors for understanding Iraq’s situation. First, the U.S. invasion created chaos and a lack of clarity in terms of the hierarchy among Shia, Sunni, and Kurdish groups. Second, given these conditions, organizations that comprised a mix of militias, political groups, and religious groups came to the fore and captured elements of the new state the U.S. was attempting to set up. Third, by about 2018, the Shia groups became dominant, establishing a hierarchy, and along with that dominance, sectarian violence has fallen. Finally, the hybrid organizations established many years ago are now highly integrated into the Iraqi state.

Petersen has also come to believe two things about the Iraq War are not fully appreciated. One is how widely U.S. strategy varied over time in response to shifting circumstances.

“This was not one war,” says Petersen. “This was many different wars going on. We had at least five strategies on the U.S. side.”

And while the expressed goal of many U.S. officials was to build a functioning democracy in Iraq, the intense factionalism of Iraqi society led to further military struggles, between and among religious and ethnic groups. Thus, U.S. military strategy shifted as this multisided conflict evolved.

“What really happened in Iraq, and the thing the United States and Westerners did not understand at first, is how much this would become a struggle for dominance among Shias, Sunnis, and Kurds,” says Petersen. “The United States thought they would build a state, and the state would push down and penetrate society. But it was society that created militias and captured the state.”

Attempts to construct a well-functioning state, in Iraq or elsewhere must confront this factor, Petersen adds. “Most people think in terms of groups. They think in terms of group hierarchies, and they’re motivated when they believe their own group is not in a proper space in the hierarchy. This is this emotion of resentment. I think this is just human nature.”

Petersen’s book, “ Death, Dominance, and State-Building: The U.S. in Iraq and the Future of American Military Intervention ,” is published today by Oxford University Press. Petersen is the Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science at MIT and a member of the Security Studies Program based at MIT’s Center for International Studies.

Research on the ground

Petersen spent years interviewing people who were on the ground in Iraq during the war, from U.S. military personnel to former insurgents to regular Iraqi citizens, while extensively analyzing data about the conflict.

“I didn’t really come to conclusions about Iraq until six or seven years of applying this method,” he says.

Ultimately, one core fact about the country heavily influenced the trajectory of the war. Iraq’s Sunni Muslims made up about 20 percent or less of the country’s population but had been politically dominant before the U.S. took military action. After the U.S. toppled former dictator Saddam Hussein, it created an opening for the Shia majority to grasp more power.

“The United States said, ‘We’re going to have democracy and think in individual terms,’ but this is not the way it played out,” Petersen says. “The way it played out was, over the years, the Shia organizations became the dominant force. The Sunnis and Kurds are now basically subordinate within this Shia-dominated state. The Shias also had advantages in organizing violence over the Sunnis, and they’re the majority. They were going to win.”

As Petersen details in the book, a central unit of power became the political militia, based on ethnic and religious identification. One Shia militia, the Badr Organization, had trained professionally for years in Iran. The local Iraqi leader Moqtada al-Sadr could recruit Shia fighters from among the 2 million people living in the Sadr City slum. And no political militia wanted to back a strong multiethnic government.

“They liked this weaker state,” Petersen says. “The United States wanted to build a new Iraqi state, but what we did was create a situation where multiple and large Shia militia make deals with each other.”

A captain’s war

In turn, these dynamics meant the U.S. had to shift military strategies numerous times, occasionally in high-profile ways. The five strategies Petersen identifies are clear, hold, build (CHB); decapitation; community mobilization; homogenization; and war-fighting.

“The war from the U.S. side was highly decentralized,” Petersen says. Military captains, who typically command about 140 to 150 soldiers, had fairly wide berth in terms of how they were choosing to fight.

“It was a captain’s war in a lot of ways,” Petersen adds.

The point is emphatically driven home in one chapter, “Captain Wright goes to Baghdad,” co-authored with Col. Timothy Wright PhD ’18, who wrote his MIT political science dissertation based on his experience and company command during the surge period.

As Petersen also notes, drawing on government data, the U.S. also managed to suppress violence fairly effectively at times, particularly before 2006 and after 2008. “The professional soldiers tried to do a good job, but some of the problems they weren’t going to solve,” Petersen says.

Still, all of this raises a conundrum. If trying to start a new state in Iraq was always likely to lead to an increase in Shia power, is there really much the U.S. could have done differently?

“That’s a million-dollar question,” Petersen says.

Perhaps the best way to engage with it, Petersen notes, is to recognize the importance of studying how factional groups grasp power through use of violence, and how that emerges in society. It is a key issue running throughout Petersen’s work, and one, he notes, that has often been studied by his graduate students in MIT’s Security Studies Program.

“Death, Dominance, and State-Building” has received praise from foreign-policy scholars. Paul Staniland, a political scientist at the University of Chicago, has said the work combines “intellectual creativity with careful attention to on-the ground dynamics,” and is “a fascinating macro-level account of the politics of group competition in Iraq. This book is required reading for anyone interested in civil war, U.S. foreign policy, or the politics of violent state-building."

Petersen, for his part, allows that he was pleased when one marine who served in Iraq read the manuscript in advance and found it interesting.

“He said, ‘This is good, and it’s not the way we think about it,’” Petersen says. “That’s my biggest compliment, to have a practitioner say it make them think. If I can get that kind of reaction, I’ll be pleased.”

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Roger Petersen

- Security Studies Program

- Center for International Studies

- Department of Political Science

Related Topics

- Books and authors

- Political science

- Middle East

- Security studies and military

- International relations

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

More MIT News

Now corporate boards have responsibility for cybersecurity, too

Read full story →

An AI dataset carves new paths to tornado detection

MIT faculty, instructors, students experiment with generative AI in teaching and learning

Julie Shah named head of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Remembering Chasity Nunez, a shining star at MIT Health

Exploring the history of data-driven arguments in public life

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Profits of War: Corporate Beneficiaries of the Post-9/11 Pentagon Spending Surge

Pentagon spending has totaled over $14 trillion since the start of the war in Afghanistan, with one-third to one-half of the total going to military contractors.

A large portion of these contracts -- one-quarter to one-third of all Pentagon contracts in recent years -- have gone to just five major corporations: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman. The $75 billion in Pentagon contracts received by Lockheed Martin in fiscal year 2020 is well over one and one-half times the entire budget for the State Department and Agency for International Development for that year, which totaled $44 billion.

Weapons makers have spent $2.5 billion on lobbying over the past two decades, employing, on average, over 700 lobbyists per year over the past five years. That is more than one for every member of Congress.

Numerous companies took advantage of wartime conditions—which require speed of delivery and often involve less rigorous oversight—to overcharge the government or engage in outright fraud. In 2011, the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan estimated that waste, fraud and abuse had totaled between $31 billion and $60 billion.

As the U.S. reduces the size of its military footprint in Iraq and Afghanistan, exaggerated estimates of the military challenges posed by China have become the new rationale of choice in arguments for keeping the Pentagon budget at historically high levels. Military contractors will continue to profit from this inflated spending.

READ FULL PAPER >

Archives Library Information Center (ALIC)

War in Iraq

Allied Participation in Operation Iraqi Freedom This publication from the U.S. Army Center of Military History "highlights a number of key aspects of allied support to the U.S.-led operation."

Apparatus of Lies: Saddam's Disinformation and Propaganda, 1990-2003 This report from the George W. Bush administration discusses the tactics that Iraq used to promote its propaganda and disinformation in four broad categories: "Crafting Tragedy", "Exploiting Suffering", "Exploiting Islam", and "Corrupting the Public Record."

Army Artists Look at the War on Terrorism The artworks reproduced in this online book from the Army Center of Military History were created by soldier-artists assigned to the Army Staff Artist Program. A chapter is devoted to the war in Iraq.

Battleground Iraq: Journal of a Company Commander The experiences of Capt. Robert ("Todd") Sloan Brown, a company commander in the war in Iraq, as described in his journal. In addition to the journal, the book contains an informative appendix.

Hired Guns: Views about Armed Contractors in Operation Iraqi Freedom A free e-book from RAND Corporation analyzing the use of armed private security contractors in the Iraq war.

The Invasion of Iraq PBS documentary about the allied invasion that removed Saddam Hussein from power.

Fact Sheet: Operation Iraqi Freedom A brief description of the events leading up to the invasion of Iraq through May, 2003.

Iraq This website provides a portal to National Public Radio's reporting on Iraq from June of 2004 to the present.

Iraq Gallup has aggregated its polling of the American people about the war in Iraq from 2003 forward on this website.

Iraq: A Chronology of UN Inspections From the Arms Control Association, this site lists a chronology of UN inspections from 1991-2002 and an assessment of UN accomplishments in Iraq as a result of weapons inspections.

Iraq and Weapons of Mass Destruction The National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 80 discusses the presence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, including digitized documents from 1981 to 2004.

Iraq: the Human Cost This website from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzes studies of Iraq War mortality statistics.

Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs The CIA's report on the search for Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.

Iraq War Medal of Honor Recipients A listing of recipients of the Medal of Honor for actions during the war in Iraq.

Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI): Iraq Overview Overview of Iraq's nuclear, biological, and chemical weapon capabilities through 2011.

On Point: The United States Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom An extensive study of the war in Iraq undertaken shortly after official combat operations ceased. From the U.S. Army's Office of the Chief of Staff.

Operation Iraqi Freedom: Casualties The Defense Casualty Analysis System provides data regarding casualties incurred during the war in Iraq. Information is available by demographics, by casualty category, by month, and by names of the fallen.

Operation Iraqi Freedom: Strategies, Approaches, Results, and Issues for Congress A 2009 report from the Congressional Research Service.

President Bush Addresses the Nation Text of President George W. Bush's address to the nation announcing the initiation of war against Iraq.

Security Council Resolution S/RES/1441 (2002) On November 8, 2002, the Security Council gave Iraq a "final opportunity" to comply with the disarmament resolutions and established a rigorous regiment of inspections.

Seven Years in Iraq: An Iraq War Timeline A year by year, month by month chronology from Time Magazine. Also included are links to videos and photographs.

Timeline: The Iraq War This interactive chronology is presented by the Council on Foreign Relations.

U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes - H.J.Res. 114 Results of the U.S. Senate vote to authorize the use of United States armed forces against Iraq.

UN Security Council: Update on Inspections Dr. Hans Blix's update to the UN on January 27, 2003.

United States Forces - Iraq "United States Forces - Iraq advises, trains, assists, and equips Iraqi Security Forces, enabling them to provide for internal security while building a foundation capability to defend against external threats."

The War Diaries: The Iraq war diaries of Lt. Tim McLaughlin This website is based on “Invasion: Diaries and Memories of War in Iraq,†an exhibit that opened at The Bronx Documentary Center in March of 2013. It includes digitized images of Lt. Tim McLaughlin's handwritten diary and journal.

War and Occupation in Iraq A 2007 report from GPF, the Global Policy Forum.

War in Iraq From PBS, "A collection of Frontline's reporting on Saddam Hussein and Iraq from the Gulf War to the present."

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

A Look Back at How Fear and False Beliefs Bolstered U.S. Public Support for War in Iraq

Twenty years ago this month, the United States launched a major military invasion of Iraq, marking the second time it fought a war in that country in a little more than a decade. It was the start of an eight-year conflict that resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 U.S. servicemembers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

The war began March 19, 2003, with an overwhelming show of American military might, described by the unforgettable phrase “shock and awe.” Within weeks, the United States achieved the primary objective of Operation Iraqi Freedom, as the military operation was called, ousting the regime of dictator Saddam Hussein.

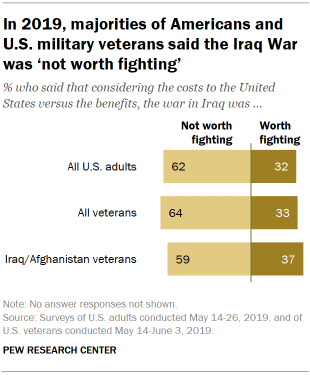

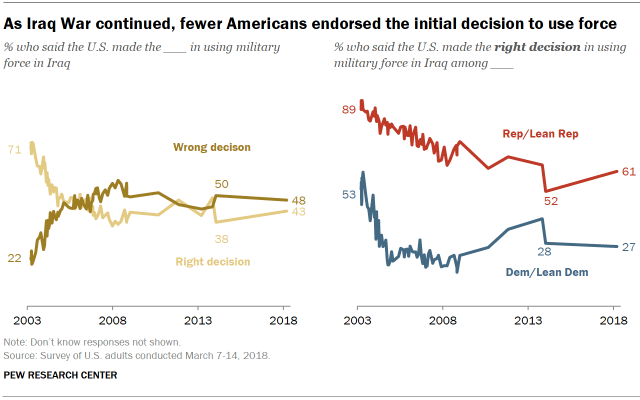

Yet the military campaign that began so auspiciously ended up deeply dividing Americans and alienating key U.S. allies . As Americans looked back on the war four years ago, 62% said it was not worth fighting. Majorities of military veterans, including those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan, came to the same conclusion.

The bleak retrospective judgments on the war obscure the breadth of public support for U.S. military action at the start of the conflict and, perhaps more importantly, in the months leading up to it. Throughout 2002 and early 2003, President George W. Bush and his administration marshaled wide backing for the use of military force in Iraq among both the public and Congress.

The administration’s success in these efforts was the result of several factors, not least of which was the climate of public opinion at the time. Still reeling from the horrors of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Americans were extraordinarily accepting of the possible use of military force as part of what Bush called the “global war on terror.”

By early 2002 , with U.S. troops already fighting in Afghanistan, large majorities of Americans favored the use of military force in Iraq to oust Hussein from power and to destroy terrorist groups in Somalia and Sudan. These attitudes represented “a strong endorsement of the prospective use of force compared with other military missions in the post-Cold War era,” Pew Research Center noted at the time.

Bush and senior members of his administration then spent more than a year outlining the dangers that they claimed Iraq posed to the United States and its allies. Two of the administration’s arguments proved especially powerful, given the public’s mood: first, that Hussein’s regime possessed “weapons of mass destruction” (WMD), a shorthand for nuclear, biological or chemical weapons; and second, that it supported terrorism and had close ties to terrorist groups, including al-Qaida, which had attacked the U.S. on 9/11.

As numerous investigations by independent and governmental commissions subsequently found, there was no factual basis for either of these assertions. Two decades later, debate continues about whether the administration was the victim of flawed intelligence, or whether Bush and his senior advisers deliberately misled the public about its WMD capabilities, in particular.

In the months leading up to the war, sizable majorities of Americans believed that Iraq either possessed WMD or was close to obtaining them, that Iraq was closely tied to terrorism – and even that Hussein himself had a role in the 9/11 attacks. Two decades after the war began, a review of Pew Research Center surveys on the war in Iraq shows that support for U.S. military action was built, at least in part, on a foundation of falsehoods.

The path to war: From the ‘axis of evil’ to a ‘mushroom cloud’

In his 2002 State of the Union address , Bush began making the case for why the United States might need to use military force to remove Saddam Hussein from power. “Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror,” he said. “The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop anthrax and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons, for over a decade.”

Iraq was one of three countries, along with Iran and North Korea, that constituted an “axis of evil,” according to Bush. But Iraq drew much more attention from the former president than did those countries. “This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world,” Bush said.

Even before his speech, Americans were inclined to believe the worst about Hussein’s regime. In a survey conducted a few weeks prior to the State of the Union , 73% favored military action in Iraq to end Hussein’s rule; just 16% were opposed. More than half (56%) said the U.S. should take action against Iraq “even if it meant U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties.”

Bush delivered this address, among the most memorable of his presidency, just four months after the terrorist attacks in New York City and near Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Americans remained on edge: 62% said they were very or somewhat worried another terrorist attack was imminent.

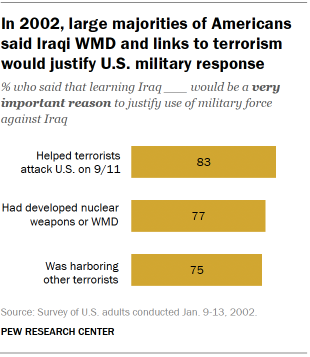

At that point, more than a year before the United States went to war, Americans overwhelmingly embraced several possible rationales for military action: 83% said that if the U.S. learned that Iraq had aided the 9/11 terrorists, that would be a “very important reason” to use military force in Iraq; nearly as many said the same if it was shown that Iraq was developing WMD (77%) or harboring other terrorists (75%).

Over the next several months, Bush and other senior officials claimed with varying degrees of certainty that there was evidence justifying the use of U.S. military force. In a speech to a Veterans of Foreign Wars convention in August 2002, former Vice President Dick Cheney was unequivocal in asserting: “Simply stated, there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us.”

On other occasions, Bush and his advisers suggested that even if there was no definitive proof that Iraq possessed WMD, it was too risky not to act, given Hussein’s failure to abide by UN weapons resolutions. “The problem here is that there will always be some uncertainty about how quickly he [Hussein] can acquire nuclear weapons,” said National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice in a CNN interview . “But we don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud.”

Such warnings resonated strongly with Americans: Most believed that Hussein either already possessed WMD or was close to obtaining them. In October 2002, 65% of the public said Hussein was close to having nuclear weapons, while another 14% volunteered that he already possessed them. Just 11% said he was not close to developing such weapons.

That month, Congress overwhelmingly approved a resolution authorizing Bush to use the U.S. armed forces “as he determines to be necessary and appropriate” to defend the security of the United States and enforce UN resolutions on Iraq. (This month, more than 20 years after it passed, Congress is moving to repeal the resolution. )

In addition to alleging that Hussein possessed (or was on the verge of obtaining) unconventional weapons, administration officials also repeatedly linked his regime to terrorists and terrorism. For the most part, these allegations were vague and unspecified, but on occasion, senior officials – including the president himself – directly connected Iraq with al-Qaida, the terrorist group that attacked the United States on 9/11. “We know that Iraq and the al-Qaida terrorist network share a common enemy – the United States of America,” Bush said that October . “We know that Iraq and al-Qaida have had high-level contacts that go back a decade.”

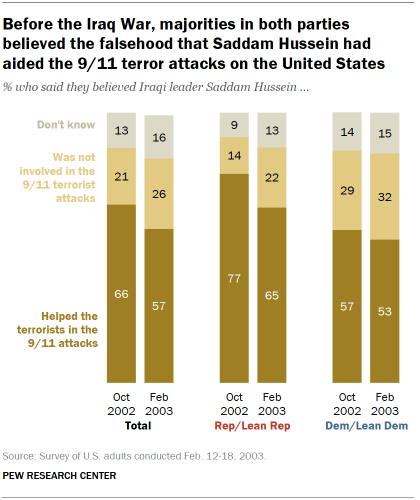

Neither Bush nor senior administration officials directly linked Iraq or its leader to the planning or execution of the 9/11 attacks. Yet a sizable majority of Americans believed that Hussein aided the terrorist attacks that took nearly 3,000 lives.

The same month that Congress approved the use of force resolution against Iraq, 66% of the public said that “Saddam Hussein helped the terrorists in the September 11th attacks”; just 21% said he was not involved in 9/11. In February 2003 , a month before the war began, that belief was only somewhat less widespread; 57% thought Hussein had supported the 9/11 terrorists.

It is not entirely clear why so many Americans – including majorities in both parties – embraced this falsehood. But by connecting Hussein to terrorism and the group that attacked the United States, administration officials blurred the lines between Iraq and 9/11. “The notion was reinforced by these hints, the discussions that they had about possible links” with al-Qaida terrorists, the late Andrew Kohut, founding director of Pew Research Center, told The Washington Post after the war was underway in 2003.

As prospects for war grew, thousands took to the streets to protest

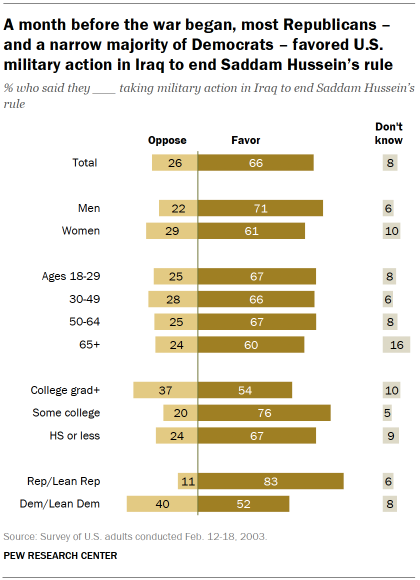

In the months leading up to the war, majorities of between 55% and 68% said they favored taking military action to end Hussein’s rule in Iraq. No more than about a third opposed military action.

However, support for military action in Iraq was consistently less pronounced among a handful of demographic and partisan groups.

The Center’s final survey before the U.S. invasion, conducted in mid-February 2003 , highlighted these differences: Women were about 10 percentage points less likely than men to support the use of military force against Iraq (61% vs. 71%).

A sizable majority of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (83%) favored the use of military force to end Hussein’s rule. Democrats and Democratic leaners were less supportive; still, more Democrats favored (52%) than opposed (40%) military action.

Yet Democrats were divided in opinions about whether to go to war in Iraq, with liberal Democrats less likely than conservative and moderate Democrats to favor using military force.

To build greater backing for the use of force among U.S. allies – and assuage lingering public concerns about war – the administration dispatched one of its most popular figures, Secretary of State Colin Powell, to the UN Security Council. In a pivotal moment in the Iraq debate , Powell presented what he described as “facts and conclusions, based on solid intelligence” to show that Iraq had failed to comply with UN weapons resolutions. “Leaving Saddam Hussein in possession of weapons of mass destruction for a few more months or years is not an option, not in a post-Sept. 11 world,” Powell said.

Powell’s address had a significant impact on U.S. public opinion, even among those who were opposed to war. Roughly six-in-ten adults (61%) said Powell had explained clearly why the United States might use military force to end Hussein’s rule; that was greater than the share saying Bush had clearly explained the stakes in Iraq (52%). Powell was particularly persuasive among those who were opposed to using force in Iraq: 39% said he had clearly explained why the U.S. may need to take military action, about twice the share saying the same about Bush.

In a last-ditch effort to prevent war, millions of protestors took to the streets in numerous cities across the world and in the U.S. on Feb. 15. While the largest demonstrations were in London and Rome , several hundred thousand antiwar protesters crowded the streets of New York City, with some carrying signs saying “No Blood for Oil.”

Americans initially rallied behind the war; then support plummeted

After the war began, administration officials were confident that the United States would quickly prevail. For a time, it appeared they would be right: U.S. and allied forces easily overwhelmed the Iraqi army.

By April 9, U.S. forces and Iraqi civilians brought down a statue of Saddam Hussein in a Baghdad square. And on May 1, Bush stood on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln – in front of a banner proclaiming “Mission Accomplished” – and declared that major combat operations had ended.

Yet the war continued for another eight years. Public support for the use of U.S. military force in Iraq, which rose to 74% during the month that Bush gave what became known as his “Mission Accomplished” speech, never again reached that level.

As U.S. forces faced a mounting Iraqi insurgency, a growing share of Americans – especially Democrats – expressed doubts about the war. The share of Americans saying the U.S. military effort in Iraq was going well, which surpassed 90% in the war’s early weeks, fell to about 60% in late summer 2003.

There had been partisan differences in attitudes related to Iraq since Bush began raising the prospect of war in 2002. But as the war continued, these differences intensified: In October 2003 , a 56% majority of Democrats said that U.S. forces should be brought home from Iraq as soon as possible, a 12-point increase from just a month earlier. By contrast, fewer than half of independents (40%) and just 20% of Republicans favored withdrawing U.S. troops.

Support for U.S. military action declined further the next year as two incidents brought the horrors of war home to Americans. In March 2004, four American private security contractors were killed and their bodies desecrated in a spate of anti-American violence. Then, the first pictures emerged of abuse of prisoners by U.S. troops at Abu Ghraib , an Iraqi prison. In a survey that May , the share of Americans who said the use of military force was going at least “fairly well” fell below 50% for the first time.

Bush’s reelection as president in November underscored the extent to which the war in Iraq had divided the nation. Among the narrow majority of voters (51%) who then approved of the decision to go to war, 85% voted for Bush; among the smaller share (45%) who disapproved, 87% voted for his Democratic opponent, John Kerry, according to national exit polls .

Public support for the war declined further during Bush’s second term. By January 2007, with the situation on the ground deteriorating, Bush defied growing calls from Democrats to withdraw U.S. forces from Iraq and instead announced that he was sending more troops to the country. What Bush called “a new way forward ” in Iraq – which became more widely known as the troop surge, or surge – was a risky gambit to alter the trajectory of the war.

The new strategy, in which more than 20,000 additional U.S. forces were deployed to Iraq, was broadly unpopular with a public that had grown weary of war. By roughly two-to-one (61% to 31%) , Americans opposed Bush’s plan to send additional forces to Iraq. Bush’s new strategy “triggered increased partisan polarization on the debate over what to do in Iraq,” the Center noted in its report on the January 2007 survey.

Still, while the overall impact of the surge on Iraq was intensely debated, it was widely credited with helping to reduce the level of violence in the country, both among U.S. troops and Iraqi civilians . While Americans acknowledged the improvement in the situation in Iraq, they remained deeply skeptical of the decision to go to war.

In November 2007 , nearly half of Americans (48%) said the war was going very or fairly well, an 18 percentage point increase from February of that year. Yet support for withdrawing U.S. forces from Iraq was undiminished; by 54% to 41%, more Americans favored bringing troops home from Iraq as soon as possible rather than keeping troops there until the situation had stabilized. Those attitudes were virtually unchanged from earlier in 2007.

With the 2008 presidential campaign approaching – and roughly 100,000 U.S. troops still in Iraq – it seemed likely that the war would again be a major issue. During the Democratic primaries , Barack Obama repeatedly contrasted his early opposition to the war with Hillary Clinton’s 2002 Senate vote in support of the war authorization.

However, after Obama defeated Clinton for the Democratic nomination and faced John McCain in the general election, the Iraq War was increasingly overshadowed by turmoil in financial markets, which triggered a worldwide economic crisis. In national exit polls conducted after Obama’s victory over McCain, 63% of voters cited the economy as the most important issue facing the country; just 10% mentioned the war in Iraq.

During the 2008 campaign , Obama vowed to end the war in Iraq, adding that the United States “would be as careful getting out of Iraq as we were careless getting in.” Three years later, the U.S. withdrew all but a handful of its troops; in a ceremony on Dec. 15, 2011 , the United States lowered the flag of command that had flown over Baghdad. President Obama’s decision drew overwhelming public support. A month before the ceremony , 75% of Americans – including nearly half of Republicans – approved of his decision to withdraw all combat troops from Iraq.

Yet Obama soon discovered how difficult it would be for the U.S. to fully disengage from Iraq. In 2014, a new security threat emerged in Iraq – the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. With ISIS taking over territory in Iraq and committing high-profile terrorist acts, the group quickly became one of the U.S. public’s top security threat s . In response, Obama reluctantly authorized U.S. airstrikes and dispatched a small number of U.S. forces back to Iraq. Five years later, his successor, then-President Donald Trump, claimed that the group was on the verge of defeat in Iraq and Syria , although some U.S. security officials say it remains a threat .

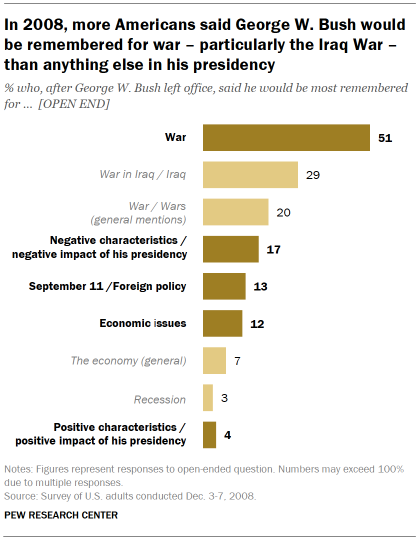

Judgments on the Iraq War and its impact on Bush’s legacy

The Iraq War has a long and complicated legacy. After the war officially ended, it remained an issue, to varying degrees, in both the 2012 and 2016 presidential election campaigns. Even in the 2020 campaign , nearly a decade after the war’s end, Trump and Joe Biden each portrayed themselves as better able to extricate the nation from what have been called “endless wars” – the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

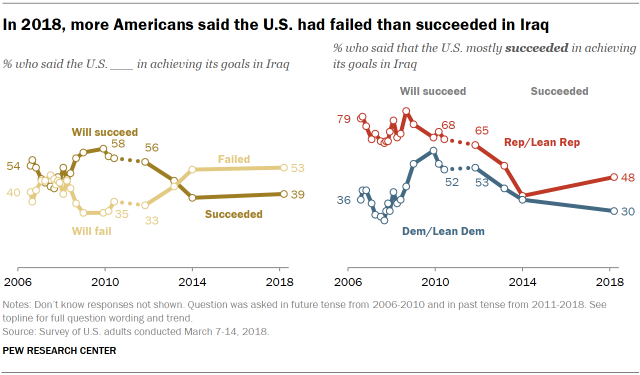

By that point, most Americans had largely moved on from the war. Shortly before the United States withdrew its forces in 2011, a majority of Americans (56%) had concluded that, despite the war’s enormous costs, the U.S. had “mostly succeeded” in achieving its goals in Iraq.

But over the next few years, that belief faded. By 2018 , the 15th anniversary of the start of the war, just 39% of Americans said the U.S. had succeeded in Iraq, while 53% said it had failed to achieve its goals.

Even among Republicans, who had consistently favored the use of U.S. military force throughout the war and before it began, there were divisions over whether the U.S. had achieved its goals in Iraq. Only about half (48%) of Republicans and Republican leaners said the U.S. had succeeded, although that was 10 points higher than four years earlier.