- Library databases

- Library website

Library Guide to Capstone Literature Reviews: Role of the Literature Review

The role of the literature review.

Your literature review gives readers an understanding of the scholarly research on your topic.

In your literature review you will:

- demonstrate that you are a well-informed scholar with expertise and knowledge in the field by giving an overview of the current state of the literature

- find a gap in the literature, or address a business or professional issue, depending on your doctoral study program; the literature review will illustrate how your research contributes to the scholarly conversation

- provide a synthesis of the issues, trends, and concepts surrounding your research

Be aware that the literature review is an iterative process. As you read and write initial drafts, you will find new threads and complementary themes, at which point you will return to search, find out about these new themes, and incorporate them into your review.

The purpose of this guide is to help you through the literature review process. Take some time to look over the resources in order to become familiar with them. The tabs on the left side of this page have additional information.

Short video: Research for the Literature Review

Short Video: Research for the Literature Review

(4 min 10 sec) Recorded August 2019 Transcript

Literature review as a dinner party

To think about the role of the literature review, consider this analogy: pretend that you throw a dinner party for the other researchers working in your topic area. First, you’d need to develop a guest list.

- The guests of honor would be early researchers or theorists; their work likely inspired subsequent studies, ideas, or controversies that the current researchers pursue.

- Then, think about the important current researchers to invite. Which guests might agree with each other? Which others might provide useful counterpoints?

- You likely won’t be able to include everyone on the guest list, so you may need to choose carefully so that you don’t leave important figures out.

- Alternatively, if there aren’t many researchers working in your topic area, then your guest list will need to include people working in other, related areas, who can still contribute to the conversation.

After the party, you describe the evening to a friend. You’ll summarize the evening’s conversation. Perhaps one guest made a comment that sparked a conversation, and then you describe who responded and how the topic evolved. There are other conversations to share, too. This is how you synthesize the themes and developments that you find in your research. Thinking about your literature research this way will help you to present your dinner party (and your literature review) in a lively and engaging way.

Short video: Empirical research

Video: How to locate and identify empirical research for your literature review

(6 min 16 sec) Recorded May 2020 Transcript

Here are some useful resources from the Writing Center, the Office of Research and Doctoral Services, and other departments within the Office of Academic Support. Take some time to look at what is available to help you with your capstone/dissertation.

- Familiarize yourself with Walden support

- Doctoral Capstone Resources website

- Capstone writing resources

- Office of Student Research Administration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Visit the Writing Center

You can watch recorded webinars on the literature review in our Library Webinar Archives .

- Next Page: Scope

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

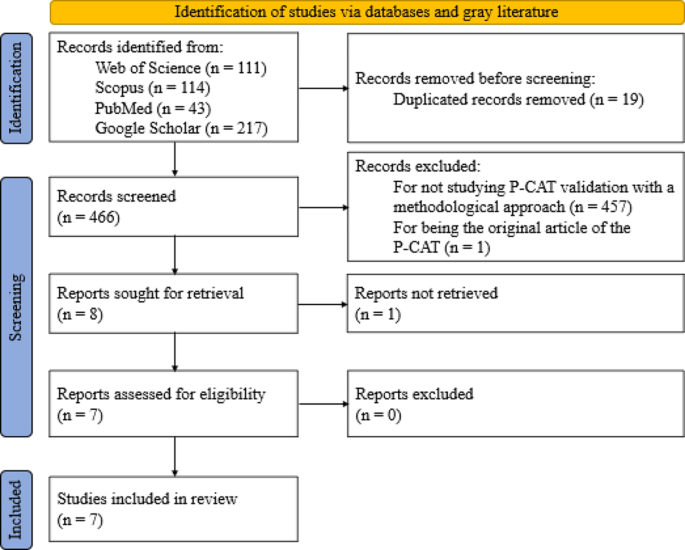

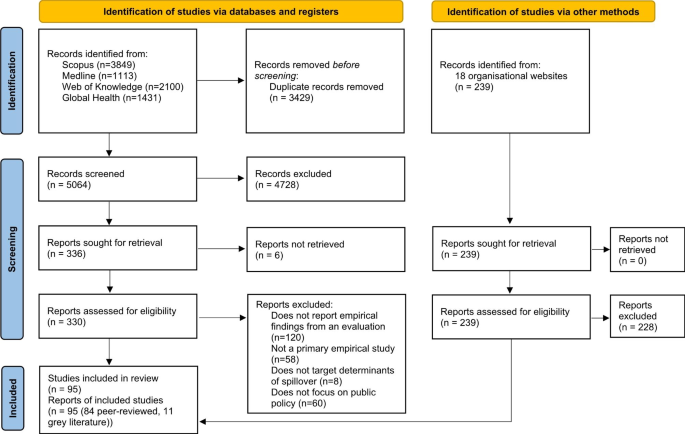

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 3:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Dec 8, 2023 10:11 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Literature Reviews

Introduction, what is a literature review.

- Literature Reviews for Thesis or Dissertation

- Stand-alone and Systemic Reviews

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Texts on Conducting a Literature Review

- Identifying the Research Topic

- The Persuasive Argument

- Searching the Literature

- Creating a Synthesis

- Critiquing the Literature

- Building the Case for the Literature Review Document

- Presenting the Literature Review

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Higher Education Research

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Politics of Education

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishing

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Literature Reviews by Lawrence A. Machi , Brenda T. McEvoy LAST REVIEWED: 27 October 2016 LAST MODIFIED: 27 October 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0169

Literature reviews play a foundational role in the development and execution of a research project. They provide access to the academic conversation surrounding the topic of the proposed study. By engaging in this scholarly exercise, the researcher is able to learn and to share knowledge about the topic. The literature review acts as the springboard for new research, in that it lays out a logically argued case, founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about the topic. The case produced provides the justification for the research question or problem of a proposed study, and the methodological scheme best suited to conduct the research. It can also be a research project in itself, arguing policy or practice implementation, based on a comprehensive analysis of the research in a field. The term literature review can refer to the output or the product of a review. It can also refer to the process of Conducting a Literature Review . Novice researchers, when attempting their first research projects, tend to ask two questions: What is a Literature Review? How do you do one? While this annotated bibliography is neither definitive nor exhaustive in its treatment of the subject, it is designed to provide a beginning researcher, who is pursuing an academic degree, an entry point for answering the two previous questions. The article is divided into two parts. The first four sections of the article provide a general overview of the topic. They address definitions, types, purposes, and processes for doing a literature review. The second part presents the process and procedures for doing a literature review. Arranged in a sequential fashion, the remaining eight sections provide references addressing each step of the literature review process. References included in this article were selected based on their ability to assist the beginning researcher. Additionally, the authors attempted to include texts from various disciplines in social science to present various points of view on the subject.

Novice researchers often have a misguided perception of how to do a literature review and what the document should contain. Literature reviews are not narrative annotated bibliographies nor book reports (see Bruce 1994 ). Their form, function, and outcomes vary, due to how they depend on the research question, the standards and criteria of the academic discipline, and the orthodoxies of the research community charged with the research. The term literature review can refer to the process of doing a review as well as the product resulting from conducting a review. The product resulting from reviewing the literature is the concern of this section. Literature reviews for research studies at the master’s and doctoral levels have various definitions. Machi and McEvoy 2016 presents a general definition of a literature review. Lambert 2012 defines a literature review as a critical analysis of what is known about the study topic, the themes related to it, and the various perspectives expressed regarding the topic. Fink 2010 defines a literature review as a systematic review of existing body of data that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes for explicit presentation. Jesson, et al. 2011 defines the literature review as a critical description and appraisal of a topic. Hart 1998 sees the literature review as producing two products: the presentation of information, ideas, data, and evidence to express viewpoints on the nature of the topic, as well as how it is to be investigated. When considering literature reviews beyond the novice level, Ridley 2012 defines and differentiates the systematic review from literature reviews associated with primary research conducted in academic degree programs of study, including stand-alone literature reviews. Cooper 1998 states the product of literature review is dependent on the research study’s goal and focus, and defines synthesis reviews as literature reviews that seek to summarize and draw conclusions from past empirical research to determine what issues have yet to be resolved. Theoretical reviews compare and contrast the predictive ability of theories that explain the phenomenon, arguing which theory holds the most validity in describing the nature of that phenomenon. Grant and Booth 2009 identified fourteen types of reviews used in both degree granting and advanced research projects, describing their attributes and methodologies.

Bruce, Christine Susan. 1994. Research students’ early experiences of the dissertation literature review. Studies in Higher Education 19.2: 217–229.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079412331382057

A phenomenological analysis was conducted with forty-one neophyte research scholars. The responses to the questions, “What do you mean when you use the words literature review?” and “What is the meaning of a literature review for your research?” identified six concepts. The results conclude that doing a literature review is a problem area for students.

Cooper, Harris. 1998. Synthesizing research . Vol. 2. 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

The introductory chapter of this text provides a cogent explanation of Cooper’s understanding of literature reviews. Chapter 4 presents a comprehensive discussion of the synthesis review. Chapter 5 discusses meta-analysis and depth.

Fink, Arlene. 2010. Conducting research literature reviews: From the Internet to paper . 3d ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

The first chapter of this text (pp. 1–16) provides a short but clear discussion of what a literature review is in reference to its application to a broad range of social sciences disciplines and their related professions.

Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26.2: 91–108. Print.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

This article reports a scoping review that was conducted using the “Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis” (SALSA) framework. Fourteen literature review types and associated methodology make up the resulting typology. Each type is described by its key characteristics and analyzed for its strengths and weaknesses.

Hart, Chris. 1998. Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination . London: SAGE.

Chapter 1 of this text explains Hart’s definition of a literature review. Additionally, it describes the roles of the literature review, the skills of a literature reviewer, and the research context for a literature review. Of note is Hart’s discussion of the literature review requirements for master’s degree and doctoral degree work.

Jesson, Jill, Lydia Matheson, and Fiona M. Lacey. 2011. Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Chapter 1: “Preliminaries” provides definitions of traditional and systematic reviews. It discusses the differences between them. Chapter 5 is dedicated to explaining the traditional review, while Chapter 7 explains the systematic review. Chapter 8 provides a detailed description of meta-analysis.

Lambert, Mike. 2012. A beginner’s guide to doing your education research project . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Chapter 6 (pp. 79–100) presents a thumbnail sketch for doing a literature review.

Machi, Lawrence A., and Brenda T. McEvoy. 2016. The literature review: Six steps to success . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

The introduction of this text differentiates between a simple and an advanced review and concisely defines a literature review.

Ridley, Diana. 2012. The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . 2d ed. Sage Study Skills. London: SAGE.

In the introductory chapter, Ridley reviews many definitions of the literature review, literature reviews at the master’s and doctoral level, and placement of literature reviews within the thesis or dissertation document. She also defines and differentiates literature reviews produced for degree-affiliated research from the more advanced systematic review projects.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

What is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

4-minute read

- 23rd October 2023

If you’re writing a research paper or dissertation , then you’ll most likely need to include a comprehensive literature review . In this post, we’ll review the purpose of literature reviews, why they are so significant, and the specific elements to include in one. Literature reviews can:

1. Provide a foundation for current research.

2. Define key concepts and theories.

3. Demonstrate critical evaluation.

4. Show how research and methodologies have evolved.

5. Identify gaps in existing research.

6. Support your argument.

Keep reading to enter the exciting world of literature reviews!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical summary and evaluation of the existing research (e.g., academic journal articles and books) on a specific topic. It is typically included as a separate section or chapter of a research paper or dissertation, serving as a contextual framework for a study. Literature reviews can vary in length depending on the subject and nature of the study, with most being about equal length to other sections or chapters included in the paper. Essentially, the literature review highlights previous studies in the context of your research and summarizes your insights in a structured, organized format. Next, let’s look at the overall purpose of a literature review.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Literature reviews are considered an integral part of research across most academic subjects and fields. The primary purpose of a literature review in your study is to:

Provide a Foundation for Current Research

Since the literature review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the existing research, it serves as a solid foundation for your current study. It’s a way to contextualize your work and show how your research fits into the broader landscape of your specific area of study.

Define Key Concepts and Theories

The literature review highlights the central theories and concepts that have arisen from previous research on your chosen topic. It gives your readers a more thorough understanding of the background of your study and why your research is particularly significant .

Demonstrate Critical Evaluation

A comprehensive literature review shows your ability to critically analyze and evaluate a broad range of source material. And since you’re considering and acknowledging the contribution of key scholars alongside your own, it establishes your own credibility and knowledge.

Show How Research and Methodologies Have Evolved

Another purpose of literature reviews is to provide a historical perspective and demonstrate how research and methodologies have changed over time, especially as data collection methods and technology have advanced. And studying past methodologies allows you, as the researcher, to understand what did and did not work and apply that knowledge to your own research.

Identify Gaps in Existing Research

Besides discussing current research and methodologies, the literature review should also address areas that are lacking in the existing literature. This helps further demonstrate the relevance of your own research by explaining why your study is necessary to fill the gaps.

Support Your Argument

A good literature review should provide evidence that supports your research questions and hypothesis. For example, your study may show that your research supports existing theories or builds on them in some way. Referencing previous related studies shows your work is grounded in established research and will ultimately be a contribution to the field.

Literature Review Editing Services

Ensure your literature review is polished and ready for submission by having it professionally proofread and edited by our expert team. Our literature review editing services will help your research stand out and make an impact. Not convinced yet? Send in your free sample today and see for yourself!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!