Sustainable Development Goals

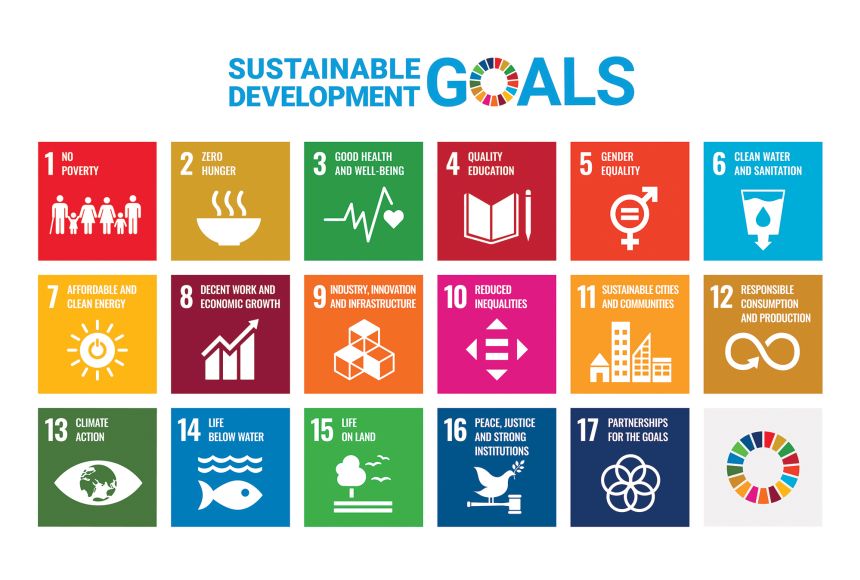

The Sustainable Development Goals were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a call-to-action for people worldwide to address five critical areas of importance by 2030: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership.

Biology, Health, Conservation, Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, Civics

Set forward by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are a collection of 17 global goals aimed at improving the planet and the quality of human life around the world by the year 2030.

Image courtesy of the United Nations

In 2015, the 193 countries that make up the United Nations (UN) agreed to adopt the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The historic agenda lays out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets for dignity, peace, and prosperity for the planet and humankind, to be completed by the year 2030. The agenda targets multiple areas for action, such as poverty and sanitation , and plans to build up local economies while addressing people's social needs.

In short, the 17 SDGs are:

Goal 1: No Poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Goal 2: Zero Hunger: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.

Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Goal 4: Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Goal 5: Gender Equality : Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.

Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation.

Goal 10: Reduced Inequality : Reduce in equality within and among countries.

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Goal 13: Climate Action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Goal 14: Life Below Water: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

Goal 15: Life on Land: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Goal 16: Peace, Justice , and Strong Institutions: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels.

Goal 17: Partnerships to Achieve the Goal: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

The SDGs build on over a decade of work by participating countries. In essence, the SDGs are a continuation of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which began in the year 2000 and ended in 2015. The MDGs helped to lift nearly one billion people out of extreme poverty, combat hunger, and allow more girls to attend school. The MDGs, specifically goal seven, helped to protect the planet by practically eliminating global consumption of ozone-depleting substances; planting trees to offset the loss of forests; and increasing the percent of total land and coastal marine areas worldwide. The SDGs carry on the momentum generated by the MDGs with an ambitious post-2015 development agenda that may cost over $4 trillion each year. The SDGs were a result of the 2012 Rio+20 Earth Summit, which demanded the creation of an open working group to develop a draft agenda for 2015 and onward.

Unlike the MDGs, which relied exclusively on funding from governments and nonprofit organizations, the SDGs also rely on the private business sector to make contributions that change impractical and unsustainable consumption and production patterns. Novozymes, a purported world leader in biological solutions, is just one example of a business that has aligned its goals with the SDGs. Novozymes has prioritized development of technology that reduces the amount of water required for waste treatment. However, the UN must find more ways to meaningfully engage the private sector to reach the goals, and more businesses need to step up to the plate to address these goals.

Overall, limited progress has been made with the SDGs. According to the UN, many people are living healthier lives now compared to the start of the millennium, representing one area of progress made by the MDGs and SDGs. For example, the UN reported that between 2012 and 2017, 80 percent of live births worldwide had assistance from a skilled health professional—an improvement from 62 percent between 2000 and 2005.

While some progress has been made, representatives who attended sustainable development meetings claimed that the SDGs are not being accomplished at the speed, or with the appropriate momentum, needed to meet the 2030 deadline. On some measures of poverty, only slight improvements have been made: The 2018 SDGs Report states that 9.2 percent of the world's workers who live with family members made less than $1.90 per person per day in 2017, representing less than a 1 percent improvement from 2015. Another issue is the recent rise in world hunger. Rates had been steadily declining, but the 2018 SDGs Report stated that over 800 million people were undernourished worldwide in 2016, which is up from 777 million people in 2015.

Another area of the SDGs that lacks progress is gender equality. Multiple news outlets have recently reported that no country is on track to achieve gender equality by 2030 based on the SDG gender index. On a scale of zero to 100, where a score of 100 means equality has been achieved, Denmark was the top performing country out of 129 countries with score slightly under 90. A score of 90 or above means a country is making excellent progress in achieving the goals, and 59 or less is considered poor headway. Countries were scored against SDGs targets that particularly affect women, such as access to safe water or the Internet. The majority of the top 20 countries with a good ranking were European countries, while sub-Saharan Africa had some of the lowest-ranking countries. The overall average score of all countries is a poor score of 65.7.

In fall of 2019, heads of state and government will convene at the United Nations Headquarters in New York to assess the progress in the 17 SDGs. The following year—2020—marks the deadline for 21 of the 169 SDG targets. At this time, UN member states will meet to make a decision to update these targets.

In addition to global efforts to achieve the SDGs, according to the UN, there are ways that an individual can contribute to progress: save on electricity while home by unplugging appliances when not in use; go online and opt in for paperless statements instead of having bills mailed to the house; and report bullying online when seen in a chat room or on social media.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Sustainability Hub

Companion Websites

Responsive Template

Education for Sustainable Development

Thematic essay.

- Case Study: ESD as Transformation

Case Study: Sustainable Schools Policy in the UK

Recommended routledge books, blogs and websites.

Click to download

‘Learner drivers’ for the future: a different education for a different world

Stephen Sterling, Plymouth University, UK

What do you think when you see those ‘L’ plates on the car in front? ‘Oh no, that’s going to slow me down...’? ; ‘Glad I got my test out of the way years ago’?

It’s a metaphor of course, but current conditions – economic, social, ecological, political, technological – are requiring us all to be ‘learner drivers’: more cautious, going slower, reading our broader environment, aware of dangers and signals of change. Because we are facing testing times like never before ‒ not just once as in the driving licence test, but over lifetimes. We are living in a different world than was the case even a decade or two ago, and the future is profoundly uncertain. As Al Gore says in his extensive study:

There is a clear consensus that the future now emerging will be extremely different from anything we have ever known in the past….There is no prior period of change that remotely resembles what humanity is about to experience. (Gore 2013: xv).

There are almost daily headlines around such issues as energy,food security, biodiversity and species loss, poverty and inequity, climate change and shifting and extreme weather patterns, employment issues, social justice, economic volatility and a rising population. These fuel a renewed urgency and debate about the possibility of sustainable development (Assadourian and Prugh 2013) – how to live well, into the future, without eroding the Earth’s ability to sustain present and future generations. Continuing the metaphor, we can ‘drive on’ blindly of course, hoping for the best. Or we can anticipate, think ahead, take avoiding action, take alternative routes. We can choose to be wise learners for the future.

When I started in environmental education some 40 years ago, it was about education that would help people understand and act on environmental issues. Now, more broadly, it’s about education and learning that can help secure a more sustainable future than ‘the one in prospect’ – as the renowned educator David Orr puts it.

For example, the international Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s (SDSN) Action Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDSN 2013) details ‘ten priority challenges of sustainable development’: ending poverty, development within planetary boundaries, effective learning for children and youth, gender equality and human rights, health and wellbeing, improving agricultural systems, curbing climate change, resilient cities, securing ecosystem services and biodiversity, and transforming governance. These are proposed as the basis of ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs), which are currently being discussed prior to their elaboration and adoption internationally in 2015 to replace the Millennium Development Goals.

So there is a growing consensus on the broad directions that need to be taken. The means by which such goals are to be addressed are often presented as: policy and monitoring, finance and incentives, legislation and regulation, information and campaigns. But these policy instruments are often only effective for as long as they are in operation ‒ because they are externally applied. Education however, can build lasting change - that is, sustainable change ‒when it is owned by the learner. Whilst policy instruments tend to treat symptoms of unsustainable activities and behaviours, education and learning can reach hearts and minds, and therefore address root causes. Further, many commentators over some years have been pointing to the urgency of a deeper cultural change, away from short-termism, individualism, excessive competition and materialism, towards an ethic of care, social justice, mutuality and wellbeing (see Earth Charter www.earthcharterinaction.org ).

Put alternatively, outer change depends on inner change as regards how we view ourselves and our relation with others and the wider world towards a relational consciousness, and this is essentially a learning process. Futurist Paul Raskin argues that, ‘The shape of the global future rests with the reflexivity of human consciousness – the capacity to think critically about why we think what we do – and then to think and act differently’ (Raskin 2008: 469). Hence the importance of the kinds of education that can effect this transformative process. The field of education for sustainable development (ESD) can be seen as a response to these considerable challenges.

Particularly since the Rio Earth Summit of 1992, and Agenda 21 ‒ which in chapter 36 laid out the challenge of educating for a more sustainable society ‒ an international ESD movement has emerged strongly, drawing on longer-established approaches such as environmental education, conservation education, development education, human rights education, and global education. This movement is concerned with identifying and advancing the kinds of education, teaching and learning policy and practice that appear to be required if we are concerned about ensuring social, economic and ecological viability and well-being, now and into the long-term future. It is, on the face of it, hugely ambitious. As UNESCO states:

ESD is far more than teaching knowledge and principles related to sustainability. ESD, in its broadest sense, is education for social transformation with the goal of creating more sustainable societies. ESD touches every aspect of education including planning, policy development, programme implementation, finance, curricula, teaching, learning, assessment, administration. ESD aims to provide a coherent interaction between education, public awareness, and training with a view to creating a more sustainable future (UNESCO, 2012:33).

This calls for a particular quality and orientation of educational and learning policies and practices, across all societies and contexts. UNESCO defines ESD as education which, ‘allows every human being to acquire the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values necessary to shape a sustainable future’ (UNESCO 2014) http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-sustainable-development/ .

Yet this reflects the central paradox of ESD. On the one hand, it is seen as critical to any prospect of a more sustainable future, but on the other, it challenges mainstream thinking, policy and practice in much formal education. Sustainability issues are often characterised by ‘wicked problems’, complexity and uncertainty, requiring participative pedagogies and collaborative engagement, interdisciplinarity, real world research and engagement, and an open-ended and a provisional approach to knowledge. This is a different kind of education for a different age. However, universities – in particular – are based on silos with regard to their teaching, learning and research, and the more transformative and holistic approach that sustainability requires is often difficult to implement, requiring systemic change and organisational learning over time (as we have attempted at Plymouth University).

Yet despite the real challenges involved ‒ and the lack of a supportive political climate in England ‒ there is a strong and growing movement towards the embedding of sustainability in education in schools and universities. This is often ‘bottom-up’, but increasingly there are signs that senior managers recognise that sustainability is important to an institution’s operation, curriculum and reputation, and the rich notion of whole institutional change towards the ‘sustainable university’ is beginning to take root (Sterling et al. 2013). Amongst university students, an NUS and Higher Education Academy study over three years shows that more than 80% of students surveyed believe sustainable development should be actively promoted and incorporated by UK universities ‒ a powerful incentive to universities hoping to increase student numbers ( NUS HEA survey , Drayson et al. 2013). Further, the centrality of learning to developing effective leadership for sustainability is increasingly recognised in the business world (Courtice 2012).

We are all ‘driving the future’, through our everyday actions and choices. If we are to secure a safer and enduring future for generations to come, the sustainability revolution ‘requires each person to act as a learning leader at some level, from family to community, from nation to world’ (Meadows et al. 2005:280). This is a big ask, but an inescapable one, and education needs to step up to the task.

Assadourian, E and Prugh, T et al. (2013) Is Sustainability Still Possible? Worldwatch Institute, Island Press, Washington.

Courtice, P. ‘The critical link: strategy and sustainability in leadership development’, in CPSL (2012) The Future in Practice – the State of Sustainability Leadership, University of Cambridge Programme for Sustainability Leadership, Cambridge. http://digital.edition-on.net/links/6431_the_future_in_practice_cpsl.asp

Drayson, R, Bone, E, Agombar, J, and Kemp, S (2013 ) Student attitudes towards and skills for sustainable development, Higher Education Academy/NUS, York.

Gore, A (2013) The Future, W.H. Allen, New York.

Meadows, D, Meadows, D and Randers, J (2005) Limits to Growth: The 30-year Update, Earthscan, London.

Raskin, P (2008) ‘World lines: A framework for exploring global pathways,’ Ecological Economics, 65, 461–70.

SDSN (2103) An Action Agenda for Sustainable Development – Report for the UN Secretary-General, Leadership Council of the Sustainable Development Leadership Council. http://unsdsn.org/resources/publications/an-action-agenda-for-sustainable-development/

Sterling, S, Maxey, L and Luna, H (2013) The Sustainable University – progress and prospects, Earthscan, Abingdon. http://www.routledge.com/9780415627740/#description

UNESCO (2012) ESD Sourcebook, Learning & Training Tools, No. 4. Paris, UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002163/216383e.pdf

Case study: ESD as Transformation – a liberal review

William Scott, University of Bath, UK

“We must take the first determined steps toward a sustainable future with dignity for all. Transformation is our aim. We must transform our economies, our environment and our societies. We must change old mindsets, behaviours and destructive patterns. We must embrace the integrated essential elements of dignity, people, prosperity, planet, justice and partnership. We must build cohesive societies, in pursuit of international peace and stability. … Such a future is possible if we collectively mobilize political will and the necessary resources to strengthen our nations and the multilateral system. We have the means and methods to meet these challenges if we decide to employ them and work together.” (UNGA, 2014)

Social critique and transformation

In 1989, the biologist Mary Clark argued that in Western history there have only been two major periods of conscious social change and transformation where societies deliberately critiqued themselves and created new worldviews. The first occurred in the Greek city states (500 – 400 BC) where old ways of thinking became suspect and the first schools emerged. Philosophers purposefully asked different kinds of questions through public dialogues, new lines of thought and social action emerged, and a new status quo was established whose ideas and practices spread. The second time, Clark said, was through the Renaissance and the Enlightenment when Western culture, through its natural and social philosophers, subjected itself to critical thought and renewal. The result was the modern worldview that the West more or less retains today, and which many believe has resulted in the sustainability problems that affect us all. The irony is, of course, that the Enlightenment also brought new values and political and social freedoms that many live by, and would wish to defend. Clark (1989: 235) argued that we need to “collectively create a new worldview that curbs ecological and social exploitation, and recreates social meaning”. She saw that this process needed to be a society-wide, citizenly, phenomenon involving everyone – not just political, social, religious or cultural elites.

It is clear that such processes need to be global in scale and scope, and optimists will want to find evidence of their happening in phenomena ranging from the UN-focused COP climate change discussions and the establishment of Sustainable Development Goals, to ground-up social action such as the Occupy, Anonymous, Divestment and Transition movements. All these, and more, might well be seen as unco-ordinated attempts to address the sustainability problematique : how can we all live well, without compromising the planet’s continuing ability to enable us all to live well, but just to write this down is to illustrate its inchoate state.

Education as transformation

Clark saw such transformational endeavours as educational in the widest sense, but she understood that the process could not just be trusted to formal educational institutions. She made a clear distinction between dominant processes of moulding society to fit in with the status quo and its received wisdoms, and the enabling of a critique of beliefs and assumptions which aids transformative change and the creation of new ways of thinking and being.

Whilst it is the case that a transformative ideal has long been near the heart of some visions of education, particularly liberal ones, this has mostly been in the sense of personal growth and fulfilment. Even to consider that formal education as we know it could lead attempts to transform society and resolve the sustainability problematique , is to reveal a core paradox; that to change society, education and schools would themselves first need to be changed by that society. This is doubly problematic because two main purposes for schooling are conservative ones of values and cultural transmission, and a preparation for citizenly and economic participation in the society that exists; in this, education is necessarily seen in instrumental, not transformative, terms.

Anyway, as some such as Andy Stables (2010) have argued, school students are only ever likely to pick up a general and diffuse sense of concern about and for the world’s problems, that is led or reinforced by any involvement they may have in the overall public discourse. Because of this, Stables says, curriculum should focus on the development of skills of critical thinking, dialogue and debate, with sustainability as one possible theme. Through this, young people would be enabled, should they choose, to take an increasing role in society and social change. The position of students in colleges and universities is similar, although their depths of understanding are greater, as is the influence they might bring to bear within those institutions, and in the jobs they take up.

ESD and transformation

For others, it is not education, per se , but education for sustainable development (ESD) that has, alongside transition, divestment, etc, this socially transformative potential. This is partly because ESD has both the imprimatur of the United Nations, and because of its ability to bring together a wide variety of educational groups and strategies aimed at addressing our existential problems. UNESCO (2012a:13) has encouraged this view:

“ESD is far more than teaching knowledge and principles related to sustainability. … in the broadest sense it is education for social transformation with the goal of creating more sustainable societies. … ESD aims to provide a coherent interaction between education, public awareness, and training with a view to creating a more sustainable future.”

However, despite UN endorsement, UNESCO sponsorship, NGO activity, and much individual effort, ESD has not fulfilled that promise, and a core difficulty is something we have seen already, albeit in different language. Stephen Sterling (2015: 4) terms it the central paradox of ESD:

“It is seen as critical to any prospect of a more sustainable future, but … it challenges mainstream thinking, policy and practice in much formal education. … The more transformative and holistic approach that sustainability requires is often difficult to implement, requiring systemic change and organisational learning over time ...”

Indeed, if education, per se cannot do this, how could ESD be more successful? An artful response to this question is to advance a co-evolutionary argument: that successful ESD would lead to change in the demands made of education by society, which would then reinforce the need for more ESD, leading, eventually to a positive transformative cycle. Thus, the argument goes, with ESD working symbiotically within both the education system and within society more generally, those in power would soon come to understand the error of their ways. This view, however, relies too heavily on disingenuous appeals to false consciousness to be taken seriously.

That said, the appeal of ESD is clear as it can claim to bring together forms of education whose geneses lie in learning activities that examine [i] how living things depend on each other and on the biosphere, [ii] why there is such a widespread lack of social justice and human fulfillment across the world and what might be done about this, and [iii] how everyone’s quality of life is increasingly imperiled by our current economic models. Thus the potential of ESD is that it might enable such deeply inter-related issues to be addressed together so that we might come to understand, address, and then resolve, the sustainability problematique. This, as we have seen, links the quality of people’s lives (now and in the future), the economic and political systems these are embedded in, and the continuing supply of goods and services from the biosphere that underpin and drive such systems.

A potential strength of ESD is the variation that is found from one context to another which has arisen from local interpretations and developments as the concept is shaped to fit, more or less comfortably, with existing policy and practice. Inevitably, this all involves accommodations with preferred ideological and epistemological dispositions. Equally inevitably, all interpretations of ESD rest on understandings of what sustainable development itself is , even if the conceptual links are loose. This diversity within ESD, which is clear to see from emerging practice, is also a weakness as it rests on a lack of shared understandings which, in turn, inhibit communication and collaboration.

Another view of ESD

Of course, not all its proponents see ESD as transformational, per se , understanding that the aim must be to effect change where possible, and usually in systems not well disposed to it. This was broadly the UN’s view (UNESCO 2005:5) when it agreed to an ESD Decade (2005 – 2014), and identified four overarching goals for “all Decade stakeholders”:

- Promote and improve the quality of education

- Reorient curriculum

- Raise public awareness and understanding of sustainable development

- Train the workforce

There is nothing here which suggests that the UN thought that educational systems or institutions should set out to be socially transformative. Rather, it took its cue from the Tbilisi Declaration (UNESCO-UNEP, 1978) and Agenda 21, building on the rich (though largely ineffective) legacy of environmental education provision whose intertwined social and environmental goals were summed up by Stapp et al ., 1979: 92):

“The evolving goal of environmental education is to foster an environmentally literate global citizenry that will work together in building an acceptable quality of life for all people.”

In the two decades following this, policy proposals, curriculum and teacher development programmes, and innovative educational resources were all developed in largely unsuccessful attempts to nudge mainstream education practice towards the Tbilisi goals. Whilst there was some modest influence on curriculum and professional development, this was not ultimately significant and made little lasting impact on education systems. Looking back on all this in 1995, John Smyth argued that the adjective environmental had been a significant barrier, as it signalled that environmental education was something separate from established disciplines and practice, and was thereby outside mainstream educational activity and influence. The fact that environmental education tended to be promoted by ministries of the environment, rather than education, both reflected the problem, and further entrenched it.

Much the same can be said today of ESD, but it is now the term, with its implicit reification, that embodies the problem. Just as we think of the UN, WHO, IMF, UNESCO, etc as institutions, so it is with ESD which, rather than being an influence on education systems and practice, has become thought and talked about as an alternative to these, and / or as equivalent to a subject or discipline. For example:

" ESD is difficult to teach in traditional school settings where studies are divided and taught in a disciplinary framework. " (McKeown 2002: 32)

This reification is particularly pronounced in higher education where much emphasis has been placed on ‘introducing ESD’ (which hardly anyone had heard about) rather than further developing the considerable professional sustainability-focused activity and expertise that already exists. The result is that no one who really matters in education systems, takes ESD seriously, and, although UNESCO (2012:5) does say that "the need for ESD [has become] well established in national policy frameworks", the evidence for this is nugatory.

A liberal end view

The more liberal view of all this (Scott, 2014) is that educational institutions need to prioritise student learning over institutional, behaviour or social change, whilst making use of any such change to support and broaden that learning. In this sense, it is fine for a school, college or university to encourage its students to save energy, create less waste, promote biodiversity, work in the community, or get involved with initiatives such as fair trade, provided that these are developed with student learning and their actual studies in mind. To do otherwise is to forget why educational institutions exist. Being restorative of social or natural capital is laudable, but not if it neglects or negates the development of learning, and doing all this in collaboration with the communities within which institutions are socially, economically and environmentally embedded, will aid everyone's learning, and perhaps even sustainable development. Thus, a successful liberal education today will take sustainability seriously in everything it does. In particular, at its heart will be students asking critical questions of society, looking for the need for change, and getting involved. Whilst some will see this as ESD, for the majority it will just be education . Paradoxically, it may well be through such small-scale, on-the-ground, open-minded developments that the potential for the sort of transformation that Mary Clark called for, and the UN General Assembly says is so necessary, may well be enhanced.

Agenda 21 http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

Clark ME (1989) Ariadne's Thread. New York: St. Martin's Press

McKeown R (2002) ESD Toolkit. http://www.esdtoolkit.org

Scott WAH (2014)Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): a critical review of concept, potential and risk. In R Matar & R Jucker (Eds) Schooling for Sustainable Development in Europe: Concepts, Policies and Educational Experiences at the End of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Dordrecht: Springer. pps 47-70

Smyth J (1995) Environment and Education: a view from a changing scene. Environmental Education Research , 1(1), 1–20

Stables AWG (2010) New Worlds Rising. Policy Futures in Education , 8(5), 593–601

Stapp W et al. (1979) Towards [a] National Strategy for Environmental Education. In AB Sacks & CB Davis (Eds.), Current Issues in EE and Environmental Studies (pp. 92–125). Columbus, OH: ERIC/SMEAC.

Sterling SR (2015) ‘Learner Drivers’ for the Future: a different education for a different world. Routledge Education for Sustainable Development Thematic Essay http://www.routledgetextbooks.com/textbooks/sustainability/education.php

UNESCO-UNEP (1978) Inter-governmental Conference on Environmental Education . Paris http://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/EE-Tbilisi_1977.pdf

UNESCO (2005) Promotion of a Global Partnership for the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable development: the International Implementation Scheme for the Decade in brief. Paris UNESCO. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001473/147361e.pdf.

UNESCO (2012a)Shaping the Education of Tomorrow: Full-length Report on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Paris http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002164/216472e.pdf

UNESCO (2012b) ESD Sourcebook, Learning and Training Tools No. 4, UNESCO: Paris http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002163/216383e.pdf

UNGA (2014) UN General Assembly. 4th December, 2014. A/69/700. The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet. Synthesis report of the Secretary-General on the post-2015 sustainable development agenda

John Blewitt

Schools are an important part of any community whose importance in promoting social health, skills and social capital should not be denied. Schools can lead by example by demonstrating ways of living, working and being that generate ecological literacy and practical competence. The UK's New Labour government aimed that all schools become models of sustainable development by 2020 with sustainable schools being 'guided by the principle of care: for oneself, care for each other (across cultures, distances and time) and care for the environment (far and near)' (DfES, 2006: 2). The UK's National Framework for Sustainable Schools asked schools to extend their commitment to sustainable development in eight key areas or 'doorways' incorporating the curriculum (teaching and learning), campus (ways of working, food, travel, energy, building construction and renovation) and community (promoting well being and public spirited behaviour). Initiatives like Sustainable Schools in the UK need substantial legislation to ensure any degree of serious success. This did not occur and the good intentions outlined here were abandoned as a result of the economic recession and the election of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat Coalition government in 2010.

Department of Education and Skills (2006) Sustainable Schools: for pupils, communities and the environment, available at www.education.gov.uk/consultations/downloadableDocs/Consultation%20Paper%20Final.pdf.

Supplementary Reading

http://blogs.bath.ac.uk/edswahs/

http://sustainability-education.blogspot.co.uk/

- Sustainability Exchange http://www.eauc.org.uk/exchange

- Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges (EAUC) http://www.eauc.org.uk/

- The Higher Education Academy http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/ourwork/teachingandlearning/sustainability

- Learning in Future Environments http://www.thelifeindex.org.uk/about-life/

- Higher Education Environmental Performance Improvement http://www.goodcampus.org/index.php

- A UK-based one-stop shop initiative by Asitha Jayawardena http://www.sustainableuni.kk5.org/

- Guide to Quality and Education for Sustainability in Higher Education http://efsandquality.glos.ac.uk

- Sustainability and Environmental Education http://se-ed.co.uk/edu/

- Plymouth University sustainability pages http://www.plymouth.ac.uk/sustainability

- UNESCO and ESD http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda

- United Nations University Education for Sustainability www.ias.unu.edu/sub_page.aspx?catID=108&ddlID=54

- Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education www.aashe.org/

- Principles for Responsible Management Education www.unprme.org/

- Eco-Schools www.eco-schools.org/

Education for Sustainability Blogs

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, academic identity and “education for sustainable development”: a grounded theory.

- Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

The research described in this article set out to explore the nature of higher education institutions’ commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs and to develop a theory of this phenomenon to support further research. The research used grounded theory methodology and took place over a two-month period in 2023. Cases were collected in four universities in New Zealand, India and Sweden and included interviews with individuals, participation in group activities including a higher education policy meeting, seminars and workshops, unplanned informal conversations, institutional policy documents and media analyses in the public domain. Cases were converted to concepts using a constant comparative approach and selective coding reduced 46 concepts to three broad and overlapping interpretations of the data collected, focusing on academic identity, the affective (values-based) character of learning for social, environmental and economic justice, and the imagined, or judged, rather than measured, portrayal of the outcomes or consequences of the efforts of this cultural group in teaching contexts. The grounded theory that derives from these three broad interpretations suggests that reluctance to measure, monitor, assess, evaluate, or research some teaching outcomes is inherent to academic identity as a form of identity protection, and that this protection is essential to preserve the established and preferred identity of academics.

1. Introduction

Many higher education institutions (HEIs) around the world have made some form of commitment to support the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals agreed by most of the nations on this planet in 2015. 1 For example, more than 1,500 universities from more than 100 countries have submitted portfolios to the 2023 Times Higher Education Impact Rankings ( Times Higher Education, 2023 ). The SDGs and the concept of sustainability relate equally to notions of social, environmental, and economic justice (sometimes described as the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit). It is to be noted that these current commitments built upon long-standing prior HEI commitments related to international agreements following on from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development 1992, including in particular Agenda 21 ( United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1992 ). Institutional commitments to sustainability generally relate to institutional research, teaching and to university campuses (or “campus as role model”). It is also to be noted that, in the context of teaching, some commitments have been made at the individual institutional level; for example, those institutions whose leaders commit via the Talloires Declaration ( Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 1994 ) to “educate for environmentally responsible citizenship.” Some commitments occur at a national level, including for example Sweden’s commitment made in 2006 that all of its educational institutions will promote sustainable development explored by Finnveden et al. (2020) . The broad field of inquiry known as Education for Sustainable Development (ESD, sometimes as HESD in higher education contexts) provides the disciplinary focus to explore these commitments and, as with all disciplines in higher education, diverse perspectives on how it operates are inherent to its practices. Even so, that education should be for sustainable development and not simply about sustainable development is fundamental to its mission.

ESD practitioners are well aware of many of the challenges involved in utilising the social construct of higher education for social change, substantially reviewed in Barth et al. (2015) . Higher education has had to manage massification (increased registration without similarly increasing funding), its broadly middle-class and privileged nature (potentially undermining its efforts towards social justice), and the market-driven ethos of higher education nowadays. Universities also attract students with a wide range of personal ambitions and expectations. Some students choose to study in academic areas to which sustainability concepts make a natural and compelling contribution. Some students even choose to study programmes designed to educate sustainability professionals. But many students, perhaps most, study subjects for which sustainability has a more challenging or transient contribution. Higher education commitments and societal expectations, however, apply to all students, not only to those who express commitment to sustainability before they arrive. And, naturally, some academics in all disciplines are highly motivated towards sustainability and likely to ensure that their teaching addresses sustainability-related topics; but some less so.

Much effort has been expended by ESD practitioners to develop educational outcomes that may in some way align to institutional contributions to the achievement of the sustainable development goals with focus recently on the development of ESD competencies ( Brundiers et al., 2020 ); competencies that may allow those who learn them to operate in a sustainable society. Relatively little emphasis however has been placed on monitoring, measuring, assessing, evaluating or researching the educational outcomes achieved by university graduates. One of the first research-based indications that higher education was finding the mission of ESD problematic came from institutional research in the USA. The University of Michigan is an institution with a renowned sustainability focus. Using both quantitative and qualitative research approaches directed at student learning, this research found; “… no evidence that, as students move through [the University], they became more concerned about various aspects of sustainability or more committed to acting in environmentally responsible ways, either in the present moment or in their adult lives” ( Schoolman et al., 2016 , p. 498). Research that reflects similar concerns was reviewed by Brown et al. (2019) . Other than these expressions of concern, there is little evidence in the public domain that the mission of ESD is on track in our universities.

The author of the current article has explored institutional efforts and outcomes in the broad contexts of environmental education (EE) and ESD over several decades in several institutions and nations. No doubt all academic researchers believe that their research and their research questions are rather important. The current author is no different but emphasises here an observation that dictates choice of research methodology and the author’s personal role within the research. How humans interact with each other and with other life on our shared planet, and with the physical planet itself, has become in recent years an existential matter for humans and for many other species. Given the extent to which our universities teach people on our planet (for example, high proportions of young people in many nations pass through higher education. India is home to one sixth of the world’s human population and more than 25% of its young people pass through its higher education sector), and the accepted vital role of education in achieving the SDGs, their role needs to be seen as an important contributory factor. In this context, the institution of higher education does need to consider its role in the context of whether higher education teaching is predominantly leading to solutions or is, perhaps, more contributing to the problems that need solutions. This research addresses not the research that universities do, but rather the research that universities might not do, or are reluctant to do, involving the consequences of what they teach on what their students learn. The research described in this article set out to explore the nature of higher education’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs and to develop a theory of this phenomenon to support further research. The research occurred in four universities in New Zealand, India and Sweden. Analysis drew from Bourdieusian social theory ( Bourdieu, 1993 ), Kahan’s exploration of the measurement problem in climate-science communication incorporating identity protection ( Kahan, 2015 ) and psychological theories that link experience and affect to behaviour.

2.1. Methodological underpinning

Given the complex nature of the SDGs and of higher education teaching, research in this broad area is unlikely to have an existing and explanatory theoretical foundation, laying as it does at the intersection of many fields of higher education enquiry. Many factors are likely involved in this situation without necessarily being clearly and widely understood or necessarily related to one another. The research needs to consider the relevance of its lines of questioning to these constituent factors and even if the institution of higher education, gatekeeper to our shared conceptualisation of scholarship, is open to such lines of questioning.

Grounded theory developed in the social sciences, whose main epistemological interest is in explaining and predicting behaviour in social interactions. The overarching goal of grounded theory is to develop theory in such circumstances, with an implicit orientation towards action, but an explicit expectation that new theory will emerge though cycles of data collection, inductive analysis and speculation on theory. The constant comparative approach ( Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ) where new data always requires the researcher to compare current inductive imaginations with past theory-building to reassess its utility, is an abiding feature of grounded-theory research. Nevertheless, the extent to which theory emerges from the analysis, or is dependent on the prior knowledge and theoretical grounding of the researcher, is a contested point. Glaser and Strauss (1967) , the two main originators of grounded theory, originally stressed the importance of the researcher developing theoretical sensitivity, so as to be mindful of theoretical possibilities as cases are considered, but not to be highly dependent on prior understanding. Strauss and Corbin (1990) , in later manifestations of grounded theory, emphasised the inevitability of the researcher using their own personal and professional experience as well as knowledge gained from the relevant literature to build new theory. The research described here used grounded theory as perhaps the only research methodology capable of addressing the research question in the complex environment of international higher education and celebrates the past professional experiences of the researcher in international higher education, not to limit possibilities of new theoretical insights but to bring awareness of multiple discourses, incorporating already-rich explanatory insights, to the task. Charmaz and Bryant (2010) emphasise that modern, constructivist interpretations of grounded theory enable researchers to explore tacit meanings and processes in complex social systems and to challenge established explanations of social functioning.

Data contributing to grounded theory in social contexts is, unlike many other qualitative research methods, not based solely on interviews. Each datum is a “case” and may give rise to an individual “concept” that represents a unit of interest. As Corbin and Strauss (2015) emphasise; “ … it is concepts and not people, per se, that are sampled” (p. 135). Cases may include, as examples, interviews with people, interviews with groups, listening or participation in group activities such as conferences, seminars and workshops, informal conversations whether planned or not, publications, fieldnotes incorporating memoranda and reflective commentaries, webpages and press releases. Cases are collected by a process of “theoretical sampling” and are developed by the researcher recording and reflecting on planned and unplanned experiences. Cases are sampled continuously and included in the analysis as planned events, as accidental or coincidental happenings, and as the consequence of further development and refinement of a developing theory needing further and focussed clarification. Importantly, cases are not necessarily built from reoccurring themes or quantifiable circumstances. An individual conversation with a single discussant can have a powerful impact on a developing grounded theory. The iterative processes of data sampling, data analysis and theory development are, theoretically, ongoing until new data ceases to contribute to the development of theory, a situation known as theoretical saturation. As a constructivist approach, data are undoubtably influenced by the researcher’s personal perspectives, experiences, values and geographical settings and the researcher’s developing understanding is essentially reflexive in nature. To some degree, grounded theory must also be somewhat unplanned and opportunistic. It is not possible to describe in advance what sources will be involved, what lines of questioning in interviews or other forms of data collection will be involved, or what experiences will be influential in developing theory. In addition, as this is research based in more than one nation, individual national or individual institutional ethics authorities are not directly applicable. Internationally recognised ethical research principles of research have been adopted in this research, as described by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council ( UKRI, 2021 ): minimising risks and maximising benefits for individuals and societies; respecting the rights and dignity of individuals and groups; ensuring that, wherever possible, participation is voluntary and appropriately informed; being conducted with integrity and transparency, with clearly defined lines of responsibility and accountability, making conflicts of interest explicit, and maintaining the independence of research. In this study, initially each case description in the author’s field notes included institution and nation, to contextualise the developing concept within it, but after the early stage of iterative data collection and analysis, the process of refining and amalgamating concepts stressed their educational, rather than geo-political contexts and allowed for a high degree of anonymity to be developed and maintained in their further analysis. Concepts described below protect the anonymity of their source, as individual, institution and nation, focusing on the author’s conception of the issue within, rather than its origin. In all cases concepts in this article are written in the author’s words, summarising each case as understood by the author, rather than as quotations attributable to groups, individuals, institutions or nations.

Data analysis starts by considering each case as a potential concept and allocating a code to it. Often a case needs to be broken into smaller constituent parts, each of which can be deeply analysed both as a possible contribution to new theory but also in the light of existing theory identified and understood by the researcher. Similar cases may be labelled with the same code. Coded elements become concepts and multiple concepts may be amalgamated or combined in some way as a higher-order category or phenomenon ( Strauss and Corbin, 1990 ). Although many different ways of exploring the relationships between concepts and categories have been described, Corbin and Strauss (2015) simplified the coding process to the three main features of conditions/circumstances, actions/interactions, and consequences/outcomes, and this simplified coding sequence was used in the research described here. Concepts are initially compared based on the conditions or circumstances in which they occurred. Subsequently concepts are related by their actions or interactions that occurred between them. Only then are concepts compared on the basis of their outcomes or consequences. The final element of grounded theory production is generally identified as “selective coding” and results in combinations of categories, where more than one category exists, to create one cohesive theory, or grounded theory.

Although a wide range of processes can be applied to research to evaluate its quality, the quality of qualitative research and in particular grounded theory is not evaluated according to measures of objectivity and significance, but according to criteria that stress utility and trustworthiness in the context within which the grounded theory has been developed. With reference to Guba and Lincoln (1989) four general types of trustworthiness in qualitative research, it is hoped that the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of this analysis would be reasonable, given the diverse nature of the discussants and places, the past experience of the researcher in HE and ESD, and the ethical processes involved in analysis and reporting. Notably the grounded theory developed in this research takes cases from diverse sources in three different nations and abstracts these to the institution of higher education internationally. Its applicability in any particular nation or institution is necessarily limited. Limitations based on the happenstance of experiencing cases, and therefore of concepts, are inevitable in grounded theory research. Nevertheless, and in line with Thomas (2006) , the credibility of the grounded theory to arise from this analysis is being tested using diverse approaches of peer review and international public debate, including this publication, with expectations that academic readers of this article will look for resonance between it and their own experiences. Transferability and dependability of the analysis are tested, to a degree, by comparison with international literature within this article. Confirmability, in particular, has not been tested but may come later, as others work with, and within, similar groups of higher education people in these and in other nations.

2.2. Data analysis: cases, concepts, categories, and a grounded theory

Case collection for this article took place over a two-month period in 2023. Cases were collected in three nations and four universities. Case collection started in the author’s own institution, a research-intensive public university in New Zealand. Case collection continued in India, initially in a research-intensive public Indian Institute of Technology, involving participation in a policy workshop to which academics interested in India’s higher education expansion programme and university contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals were invited to contribute, and subsequently in a small, private university, with a known focus on equity and related social purposes. The final stages of case collection occurred in Sweden, in a research-intensive university. Reflection on cases and data analysis continued after this two-month period once the author had returned to New Zealand.

Beyond starting in the author’s own institution and nation, choice of nation in which to conduct this research was purposeful.

India has a population of over 1.4 billion and 25% of its young people attend universities. India has more than 1,000 universities, 42,000 higher education colleges, and more than 1.5 million academic staff. India’s 2020 National Education Policy (NEP) expresses an intention to raise its gross enrolment ratio to 50% by 2035, to restructure its education system to match India’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals, and to use higher education as a tool for social change, in particular in the context of equity and social justice. India implemented quota-based policies to address caste-based differences in university recruitment in the 20th Century (Reservation) and policies to address gender differences in university participation. Much more is planned.

… “The global education development agenda reflected in the Goal 4 (SDG4) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by India in 2015 – seeks to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030. Such a lofty goal will require the entire education system to be reconfigured to support and foster learning, so that all of the critical targets and goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development can be achieved ( NEP, 2020 , p. 3). … The National Education Policy lays particular emphasis on the development of the creative potential of each individual. It is based on the principle that education must develop not only cognitive capacities – both the “foundational capacities” of literacy and numeracy and “higher-order” cognitive capacities, such as critical thinking and problem solving – but also social, ethical, and emotional capacities and dispositions ( NEP, 2020 , p. 4). … 11.8. Towards the attainment of such a holistic and multidisciplinary education, the flexible and innovative curricula of all HEIs shall include credit-based courses and projects in the areas of community engagement and service, environmental education, and value-based education ( NEP, 2020 , p. 37).

Sweden is one of very few nations that has historically legislated that its universities are to educate for sustainable development. Since 2006, higher education institutions (HEIs) in Sweden, should according to the Higher Education Act, promote sustainable development (SD). In 2016, the Swedish Government asked the Swedish Higher Education Authority to evaluate how this role was proceeding. An academic article based on the study’s final report suggested that “Overall, a mixed picture developed. Most HEIs could give examples of programmes or courses where SD was integrated. However, less than half of the HEIs had overarching goals for integration of SD in education or had a systematic follow-up of these goals. Even fewer worked specifically with pedagogy and didactics, teaching and learning methods and environments, sustainability competences or other characters of education for SD. Overall, only 12 out of 47 got a higher judgement” ( Finnveden et al., 2020 , p. 1). The author’s enquiries focus in particular on exploring incidences of the systematic follow-up referred to by Finnveden et al. (2020) .

Arguably, the scale of India, and of its higher education system, suggests that, globally, what happens there in the context of ESD is somewhat more important than what happens in most other individual countries. It seems likely that more than 20% of the world’s academics and higher education students are Indian. Sweden’s historical commitment to promoting sustainable development via its education system makes it internationally recognised as a case of special interest. Despite its scale, New Zealand also has significant aspirations in the context of social justice, its colonial past, and waves of immigration. Although each of New Zealand’s eight universities has significant independence, a range of government measures directs many of their actions, for example, processes aimed at improving Māori and Pacific Islands student enrolment, retention and success (See for example TEC, 2023 , on equity funding). At present, attendance at university does not reflect either Māori aspirations for partnership, endorsed by the nations’ Treaty of Waitangi, or the aspirations of Pacifica people for equitable access to higher education, to the professions, to jobs, and to health care, social support and social inclusion in general. A key issue for Aotearoa New Zealand in the context of its Treaty of Waitangi and notions of partnership is the place of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) in formal education. Seven professors from one New Zealand university recently questioned parity for mātauranga Māori with other bodies of knowledge, initiating considerable debate within the sector. Another university is addressing claims of institutional racism in these contexts. New Zealand also takes academic freedom seriously. It is legislated for in its Education Act, as is the principal aim of tertiary education of developing intellectual independence ( Shephard, 2020 , 2022 ). New Zealand may be a small nation, but these issues are directly relevant to discourses of ESD and are of international relevance.

Data collection and analysis proceeded in an iterative manner, within the constraints of a journey from New Zealand through India to Sweden and back to New Zealand. Elements of grounded theory methodology, particularly that involving constant comparison between data and developing theory, are difficult to delineate as method and result. Much that relates to method, therefore is interpreted in this analysis as result.

Initially, at a surface level, in each country, cases simply revealed known barriers to ESD, such as academics “ … keeping their heads down” (perhaps resulting in them not teaching for social, environmental or economic justice as anticipated in national and institutional policies) and suggestions by university academics, of schoolteachers “ … not being prepared or trained to teach sustainability” (perhaps as a consequence of university education departments’ practices but resulting in newly recruited HE students perhaps needing more learning than otherwise anticipated). These were initially coded as barriers, but as more cases were added they could be coded with more insight as, for example, lack of research into higher education practices and outcomes. At an early stage, however, in each nation, many cases needed to be coded as relating to values and attitudes, rather than to knowledge and skills. For example, an observation by a discussant who teaches in Development Studies, that students are good at critical thinking in the classroom but do not use their critical thinking skills to overcome typical prejudices. A different discussant confirmed that “Employers think our students are critical thinkers but may not be empathetic to disadvantaged people . ” Another discussant emphasised that “The State cannot legislate for attitudes … . ” Many such cases emphasised that ESD is inherently a quest for affective learning or values, attitudes and dispositions, rather than just for cognitive learning for knowledge and skills.

At particular stages in this enquiry, key events occurred that forced this researcher to re-evaluate the coding on previously assessed cases. For example, one discussant (who was personally highly active in promoting social purposes in their own institution) suggested that (in their experience) some university teachers simply did not identify with, or teach, a social purpose even though they may be, in other respects, very effective academics within their own disciplines. This same discussant confirmed that some institutions did not apply drivers or incentives to direct their academics towards the social purposes espoused by that institution, and (most meaningfully for the researcher) doubted that such academics should feel obliged to be directed by these drivers, even if they existed. This discussant felt strongly that teachers should teach as their conscience directs them to, and that institutions should encourage this to happen. This discussant was verbalizing a concept relating to the behaviours of individual academics and of institutions that appears to stem from the professional identities of individual academics, and the organisational behaviours of academic institutions, that prioritises academic freedom. As a result of this case, many other cases needed to be re-examined and recoded to include aspects of academic identity and academic freedom. School teachers not being prepared or willing to teach sustainability becomes a possible consequence of the expression of academic freedom by academics in education departments (where schoolteachers are trained or educated) and of the organisational behaviour of institutions charged with the responsibility to train or educate schoolteachers. This case also interacted with others to emphasise the complexity of related circumstances in higher education. While this discussant perhaps emphasised the academic freedom of academics and of institutions to teach as they thought fit, other cases emphasised that university teachers or groups of university teachers should not be allowed to teach as they see fit. Some discussants in a group conversation suggested that other academics in their institution were strongly opposed to that group’s experimental and experiential approaches to teach “for” sustainable development and in particular expressed doubt that it was the role of higher education to encourage students to become emotionally attached to ideas such as sustainability, social justice or sustainable development. Discussants in this conversation, on the other hand, felt strongly that becoming emotionally, or affectively, involved with sustainability issues was at the heart of their nation’s commitment to sustainable development and to their institution’s obligations to educate for sustainable development. Supporting this case, other discussants in other institutions shared concerns that academics who become emotionally involved in their teaching are subject to burn-out, and that such academics who teach broader educational objectives, such as sustainability, are highly vulnerable in higher education. Many such conversations implicitly addressed the roles that academics, academic groups and institutions should have and the internal and external drivers that enable, limit or maintain these roles, and collectively identified diverse viewpoints in these regards.

Noticeable within this data was that while many, perhaps most, discussants were happy to reflect on what HE should be doing, and how HE should operate, and what it should achieve, this was generally based on deeply-held beliefs about HE, personal experience within HE, and perceptions of academic and disciplinary identity held by academic people, rather than on particular knowledge of the sustainability-related outcomes or consequences of HE, either in particular circumstances, relating to particular teachers or courses, or collectively, relating to whole institutions. Implicit within concepts such as “Academics in this university simply do not want to learn how best to teach students to be for sustainability” is not a sound evidence base of knowledge that higher education students are not learning to be for sustainability, but a deeply held belief that they should be for sustainability, a concern that at present and on balance they may not be, and an experience-based inference that academics in general do not wish to apply themselves to this end. Implicit within concepts such as “What can higher education give to society in the future? Transmission of information is no longer enough . ” is not a sound evidence base of knowledge that higher education is not currently delivering something more than “Transmission of information” but a strong and personal feeling that this is what is currently, and on balance, happening now. Of course, much within this interpretation depends on how knowledge is perceived in this context. Notably, expressed concerns about: “increasing inequality,” “racism, discrimination, and bullying” ; “ [being] disadvantaged by language, lack of cultural capitol, lack of preparation, lack of support” ; “Higher education need [ing] a substantial and broad change to perform a social purpose” ; and “It [being] difficult to measure or monitor change in values” relate not in particular to individual courses or programmes where sustainability might be a predetermined focus, and where students have elected to study and learn in this context, but to higher education experiences in general.

In some contexts, perhaps knowledge can be contextualised as what personal experience suggests might be the case, but in most HE contexts knowledge claims have higher levels of accountability. In all disciplines, for example, knowledge claims are based on and develop from scholarly research that builds on prior knowledge, contributes to future interpretations through knowledge-based discourse, and is circulated in peer-reviewed publications. Different disciplines have different means to develop disciplinary knowledge and different ways to describe knowledge, but no disciplines base their knowledge claims solely on the deeply held beliefs of practitioners. Advances in knowledge within the disciplines is hard-won. Higher education is not, of course, simply a collection of disciplines, but differences in how the institution of higher education conceptualises its own development, from how it conceptualises the development of disciplines that exist within it, are strongly evident in the concepts that contribute to the present research. A core element of the grounded theory developing here is that much relating to outcomes and consequences within this broad ESD context is not based on knowledge, but on hopes, aspirations, good intentions, assertions, and beliefs about what should happen, and on diverse expressions of the academic identity and mission of individual academics and of universities relating to how these things should come about.

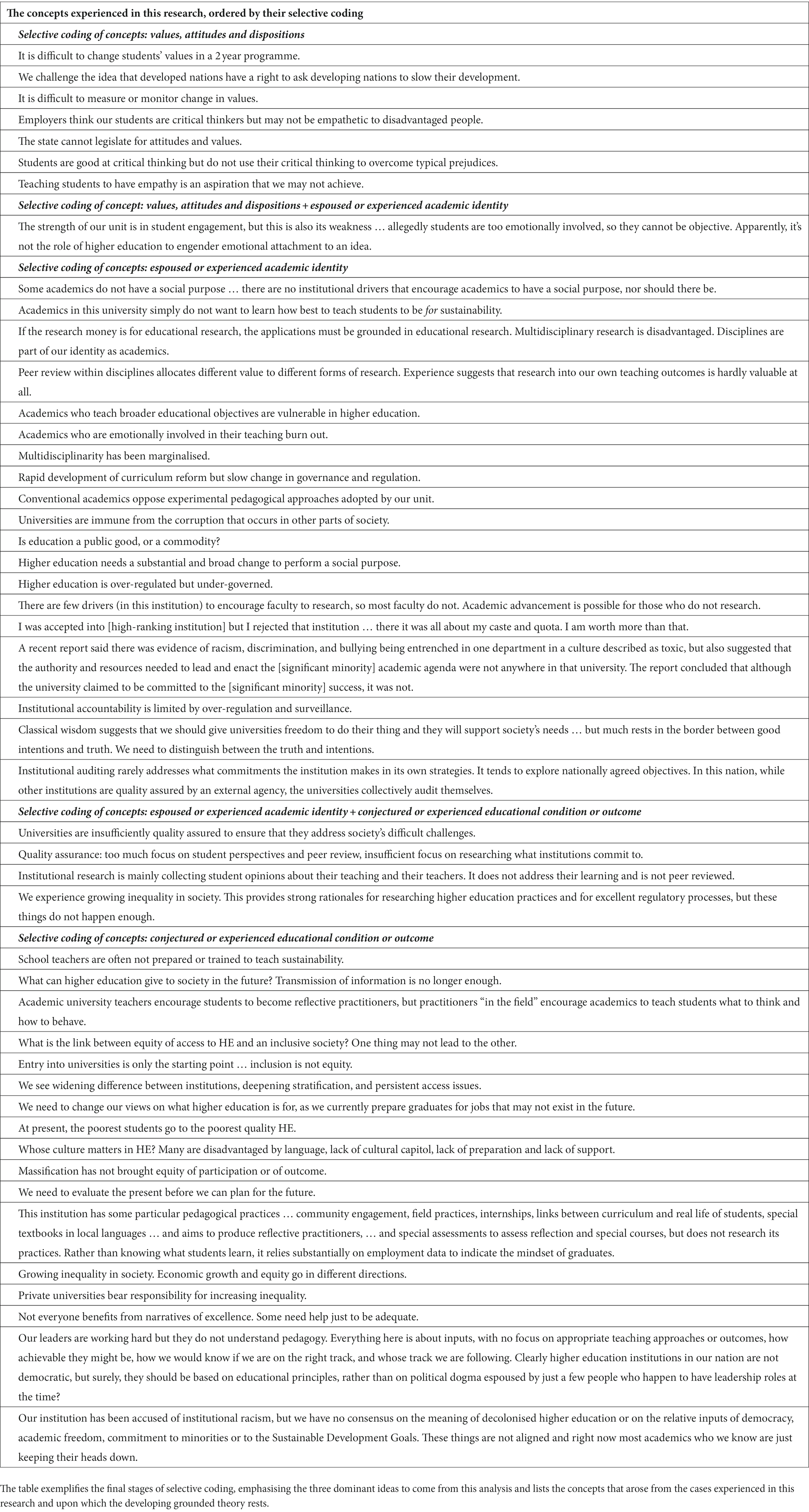

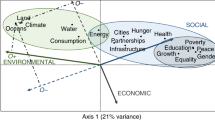

The process of selective coding therefore started with three broad and overlapping interpretations of the data collected. The first focuses on academic identity, or the cultural identity of higher education academics, and perceptions of what people in this cultural group think they or others should do, think they should not do, and think that they actually do and achieve, particularly as these things relate to learning in the affective domain. The second identifies affect and emotion as a central feature of the concepts addressed in this research and of the nature of ESD. The third addresses the imagined, or judged, rather than measured nature of the outcomes or consequences of the efforts of this cultural group, or application of this academic cultural identity, in teaching contexts. Nowhere within this research was an assertion of academic or institutional identity based on a sound knowledge base of what graduate outcomes were being achieved, on balance, in the name of social, environmental and economic justice. Even expressions of lack of sustainability-related achievements were based on assumption, supposition and expressions of barriers to ESD. Expressions of higher education quality in these contexts are based on inputs rather than outcomes. The grounded theory that derives from these three broad interpretations suggests that reluctance to measure, monitor, assess, evaluate or research teaching outcomes (or the consequences of the expression of academic identity in the context of teaching), so as to give expression to ESD, is inherent to this identity as a form of identity protection, and that this protection is essential to preserve the established identity of academics in the face of threats imposed by learning in the affective domain. The grounded theory suggests that academic identity in the context of sustainability focuses on achieving cognitive outcomes, not affective outcomes, and that protection of this identity-ideal requires academics to minimise their engagement with educational outcomes that stress emotional engagement with concepts or ideas (other than those that enhance or protect academic identity itself or, to a degree, that are explicit within particular disciplines or professions), even to the point of being unwilling to explore the emotional or affective outcomes of their teaching, individually or at an institutional level. As a consequence, the institution of higher education is unable to report its teaching-related contribution to sustainability outcomes, at the same time as being able to pronounce its positive contributions to sustainability through its very genuine research and campus-sustainability efforts. Table 1 lists concepts that arose from the cases experienced in this research and upon which the developing grounded theory rests, and the final stage of selective coding, emphasising the three dominant ideas to come from this analysis. Table 1 represents, in effect, one step in a pathway to an integrated set of conceptual hypotheses developed from empirical data (as described by Glaser, 1998 ).

Table 1 . Development of a grounded theory to explain the nature of HEI’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs.

4. Discussion

Selective coding of the concepts developed in this research emphasises three concepts that together say much about the nature of HEI’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs; academic identity, concerns about affect and emotion as central features of social, environmental and economic justice, and the imagined, or judged, rather than measured nature of the outcomes or consequences of university teaching in this context. Grounded theory seeks to find commonality between these concepts and to progressively develop a theory with explanatory power that could potentially suggest action. The theory that has emerged from this research suggests that reluctance to measure ESD is inherent to the academic identity dominant in higher education as a form of identity protection, essential to preserve the established identity of academics in the face of threats imposed by teaching, and learning, in the affective domain.

It is demonstrably the case that higher education teaching is undertaking ESD and achieving outcomes in this context. An abundance of higher education research and institutional contributions to international collaborations such as the AASHE STARS programme ( STARS, 2023 ) make it clear that many higher education institutions and many individual academics in these institutions are using their teaching to achieve significant sustainability-related outcomes. In addition, an abundance of guidance (see for example, UNESCO, 2017 ) and commitments from academic leaders in higher education institutions (see for example Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 1994 ) confirms that such actions are significantly promoted and supported in and by the sector. But the concepts explored in this study point to some significant limitations in these efforts and in these outcomes. Concepts such as “Employers think our students are critical thinkers but may not be empathetic to disadvantaged people” and “Teaching students to have empathy is an aspiration that we may not achieve” reinforce the message that ESD is a quest for affective outcomes ( Shephard, 2008 ). “It is difficult to measure or monitor change in values , ” suggests that such affective outcomes are difficult to realise ( Craig et al., 2022 ). “The state cannot legislate for attitudes and values . ” and “Apparently, it’s not the role of higher education to engender emotional attachment to an idea . ” point not only to the challenges of teaching in the affective domain, but also to perceptions of what might be missing in the context of a functional conceptualisation of ESD.