Cyber violence: What do we know and where do we go from here?

May 31, 2017

This paper reviews the existing literature on the relationship between social media and violence, including prevalence rates, typologies, and the overlap between cyber and in-person violence. This review explores the individual-level correlates and risk factors associated with cyber violence, the group processes involved in cyber violence, and the macro-level context of online aggression. The paper concludes with a framework for reconciling conflicting levels of explanation and presents an agenda for future research that adopts a selection, facilitation, or enhancement framework for thinking about the causal or contingent role of social media in violent offending. Remaining empirical questions and new directions for future research are discussed.

Get access to the full article from Aggression and Violent Behavior, Volume 34, here .

Authors: Jillian Peterson and James Densley

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.012

- Peer-Reviewed

- Watch or Listen

- By Jill and James

- Data Visualizations

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- November 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- August 2017

Privacy Overview

- UN Women HQ

A Guide for Women and Girls to Prevent and Respond to Cyberviolence

A Guide for Women and Girls to Prevent and Respond to Cyberviolence has been developed to help build awareness on the different forms of cyberviolence and provide some essential practices and strategies to minimize being subjected to cyberviolence - and to be able to respond in case it happens.

Restrictions, lockdowns and other response measures to the COVID-19 pandemic have boosted people’s already-growing online presence, interactions and reliance on digital services. This connective technology holds enormous potential for empowering women and girls; it expands access to public services, creates opportunities for education and skills development, enables social engagement at a distance, provides a wealth of entertainment and open doors to employment and entrepreneurship. Unfortunately, it can also lead to cyberviolence - harms such as bullying, harassment, loss of privacy and direct violence - especially against women and girls who are just crossing the digital divide. These risks need to be eliminated so that women and girls have equal access to and use of digital tools and can equally benefit from growth in the digital economy.

The guide has been produced by UN Women and UNICEF under the joint UN project ‘Accelerating Women’s Empowerment for Economic Resilience and Renewal: The post-COVID-19 reboot in Armenia’, implemented by UNDP, UNIDO, UNICEF and UN Women.

View online/download

Armenian , English

Bibliographic information

Latest news.

- About UN Women

- Executive Director

- Regional Director

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Procurement

- UN Women in Action

- EU 4 Gender Equality

- Digital Library

- 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence

- Refugee Response Plan

- UN System Coordination in Europe and Central Asia

- Women's Entrepreneurship EXPO

- Programme implementation

- Transformative Financing for Gender Equality in the Western Balkans

- Leadership and Political Participation

- Economic Empowerment

- Ending Violence against Women

- National Planning and Budgeting

- Representative

- Women's Economic Empowerment

- Gender-Responsive Governance and Leadership

- Communications and Advocacy

- Partnership and Coordination

- Economic Empowerment of Women

- Elimination of Violence against Women

- National planning and budgeting

- Sustainable Development Agenda

- Ending violence against women

- Peace and security and engendering humanitarian action

- Economic empowerment

- Peace and security

- Leadership and political participation

- UN system coordination

- Gender Equality Facility

- Ending violence against women and girls

- Refugee Response

- Gender-responsive planning and budgeting

- Private sector partnerships and male engagement

- Strengthening Civil Society Capacities and Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships

- Regional Civil Society Advisory Group

- Regional Forum on Sustainable Development for the UNECE region

- UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW68)

- International Women's Day 2023

- UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW67)

- Supporting women and girls in Türkiye in the aftermath of the earthquakes

- Ukraine crisis is gendered, so is our response

- Regional Forum on Sustainable Development for the UNECE Region

- International Women’s Day 2022

- International Day of Women and Girls in Science

- Women, peace and security

- Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

- Generation Equality

- International Girls in ICT Day

- Women refugees and migrants

- Women in humanitarian action

- International Day of Rural Women

- Women and the SDGs

- Media contacts

- Publications

- SDG monitoring report

- Progress of the world’s women

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Effects of information overload, communication overload, and inequality on digital distrust: a cyber-violence behavior mechanism.

- 1 School of Management, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

- 2 Department of Business Administration, Sukkur Institute of Business Administration University, Sukkur, Pakistan

- 3 School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China

In recent years, there has been an escalation in cases of cyber violence, which has had a chilling effect on users' behavior toward social media sites. This article explores the causes behind cyber violence and provides empirical data for developing means for effective prevention. Using elements of the stimulus–organism–response theory, we constructed a model of cyber-violence behavior. A closed-ended questionnaire was administered to collect data through an online survey, which results in 531 valid responses. A proposed model was tested using partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS 3.0, v (3.2.8). Research findings show that information inequality is a strong external stimulus with a significant positive impact on digital distrust and negative emotion. However, the effects of information overload on digital distrust and the adverse effects of communication overload on negative emotions should not be ignored. Both digital distrust and negative emotions have significant positive impacts on cyber violence and cumulatively represent 11.5% changes in cyber violence. Furthermore, information overload, communication overload, information inequality, and digital distrust show a 27.1% change in negative emotions. This study also presents evidence for competitive mediation of digital distrust by information overload, information inequality, and cyber violence. The results of this study have implications for individual practitioners and scholars, for organizations, and at the governmental level regarding cyber-violence behavior. To test our hypotheses, we have constructed an empirical, multidimensional model, including the role of specific mediators in creating relationships.

Introduction

Cyber violence refers to any behavior on the Internet advocating violence or using language calculated to inflame the passions to achieve mass emotional catharsis ( Hou and Li, 2017 ), which can be considered an extension of social violence to the Internet ( Li et al., 2017 ). In the past 2 years, with the rapid growth of Internet users, cyber violence incidents on social media have appeared frequently, including such behavior as bullying, flaming, and verbal abuse, and even death threats. For example, Doctor An, the protagonist of the “collision” incident at the Deyang swimming pool in 2018, committed suicide as a result of the added stress of cyber violence. During the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) epidemic in 2020, private information such as ID numbers and photographs of confirmed COVID-19 patients and people who live in Hubei province was widely spread on social networks. This resulted in suffering and serious secondary harm to the parties involved from excessive hardcore prevention and control. Studies have shown that cyber violence can have serious adverse consequences on an individual's psychology and physiology ( Sincek et al., 2017 ; Backe et al., 2018 ) and is a major factor in fomenting social instability. Therefore, clarifying the mechanism of cyber violence and understanding its essence constitute a worthwhile goal for governmental policy makers to develop scientific guidelines for relevant online behavior, as well as protecting the physical and mental health of Internet users and maintaining social stability and unity.

In the academic world, domestic and foreign scholars from many fields, such as political philosophy ( Finlay, 2018 ), law ( Cheung, 2009 ), media ( Zhang, 2012 ), sociology ( Owen et al., 2017 ), and psychology ( Hou and Li, 2017 ), have made many useful contributions to the study of cyber violence. The research concerns of Chinese scholars with regard to cyber violence mainly focus on analyzing the type of behavior and key influences, the characteristics of the current situation, and new development trends in governance. The research methods mainly involve qualitative analysis and typical case studies. These investigations have produced a wealth of data, providing a solid theoretical basis and practical information for future scholars. However, the work to date has mainly centered on the occurrence and development of cyber violence from the macro and medium perspective. Only rarely have investigators combed through the antecedents and internal mechanisms of the formation of cyber violence from the viewpoint of individual users. Therefore, utilizing the theoretical framework of stimulus–organism–response (SOR) modeling, this article combines external environmental stimuli with individual cognition to explore the relationships between the various factors that generate cyber violence to reveal its mechanism.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Theoretical background.

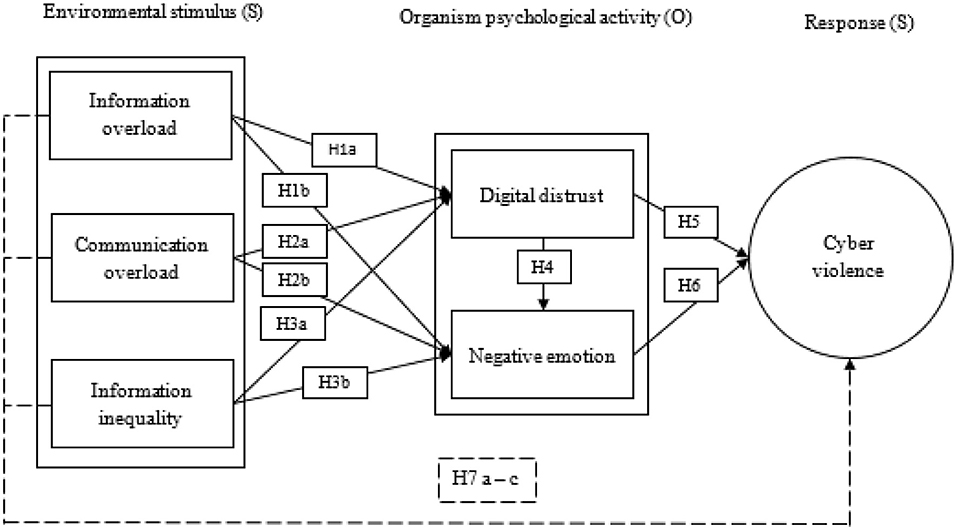

In the 1970s, some scholars began to realize that all aspects of the environment are external stimuli that affect an individual's cognition and emotion, which in turn influences them toward responsible behavior, leading to the proposal of the well-known SOR theory ( Mehrabian and Russell, 1974 ). Domestic scholars have applied SOR theory to the study of consumers' shopping behavior ( Zhang and Lin, 2017 ), online shopping trends ( Syastra and Wangdra, 2018 ), employee complaints ( Xie et al., 2019 ), and many other social phenomena. Thus, SOR theory and its associated framework have become accepted as the primary research tools for effectively analyzing individual behavior. Based on previous studies and SOR theory, this article holds that the formation of cyber violence progresses through three stages, namely, influences of environmental stimuli (S), psychological activity of the organism (O), and its collective responses (R). Our model has the following attributes:

1. In terms of external stimulation, individual users are affected by the information and communication overload (CO) unique to the digital era, and the information inequality (II) caused by the information cocoon room effect.

2. The combined effects of the above stimuli cause individuals to have complex psychological reactions, such as feeling of doubt and disagreement among users, expressed as digital distrust (DD) and negative emotions such as anxiety and disgust.

3. Individual reactions may take the form of specific negative behavior, such as cyber violence.

Based on the above analysis, behavior leading to cyber violence is essentially a kind of feedback from digital users for coping with negative influences from the external environment combined with internal psychological stress. The external environmental factors include information overload (IO), CO, and II. Online distrust and negative emotions are typical psychological responses to these external factors. Cyber violence is the behavioral feedback resulting from these individual psychological activities.

Hypotheses Development

Information overload.

IO refers to the situation where information exceeds the ability of a user to process and utilize it, resulting in negative feelings of failure. IO is a function of information quality and quantity—specifically, excessive quantity and poor quality ( Rong, 2010 ; Cheng et al., 2014 ). Excess information is usually a result of redundancy, and users can reduce this factor with various digital technologies that continuously compare the effectiveness of information among users and increase the possibility of disagreements among users. The decrease in information quality makes users doubt the truth of the information presented and have to take time to determine its veracity. When users have to spend too much time in an attempt to obtain effective information, negative emotions will occur ( Asif Naveed and Anwar, 2020 ). The research of Congard and Carole (2020) on IO in the international network environment also showed that too much information will generate negative emotions among users. Therefore, this article proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a: IO has a significant positive effect on DD.

H1b: IO has a significant positive effect on negative emotions.

Communication Overload

CO refers to a situation in which a network's communication needs exceed an individual's communication ability ( Cho et al., 2011 ; Tripathy et al., 2016 ), which can interrupt a user's study or work schedule ( Cao and Sun, 2017 ). CO can disturb the normal routine of users ( Mcfarlane and Latorella, 2002 ), and the frequent interruptions make it difficult for them to concentrate ( O'Connail and Frohlich, 1995 ; Mcfarlane, 1998 ). This can lead to a decline in the accuracy of judgment and thus negatively affect users' feelings about trusting the information and even other individuals ( Mcfarlane and Latorella, 2002 ). At the same time, when faced with social communications that have to be dealt with, users who lack effective communication skills may be at a loss and can suffer from fatigue and anxiety ( Mcfarlane, 1998 ). Consequently, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H2a: CO has a significant positive effect on DD.

H2b: CO has a significant positive effect on negative emotions.

Information Inequality

II results from inherent social inequities that affect how people at different socioeconomic levels gain access to information and what types of information are distributed to them. Differences in information access are mainly related to the level of technological development in a region, but also to individual educational background. Good education and high-quality social resources generally ensure equal access to and use of information technology and information resources ( Figueiredo, 2018 ). The essence of information distribution inequality is the selectiveness inherent in the power to control information, which is considered a necessary element of resource distribution ( Hargittai and Hsieh, 2013 ). As inequities in information access have been largely addressed by most countries, the II discussed in this article will mostly refer to its unequal distribution. Controlling who gets what information is much easier on Internet-based platforms than with print media. Mastering the technology for channeling fragmented information according to some algorithm has allowed media giants to take advantage of the system to restrict distribution and deprive users of their right to information. II selectively influences users' perceptions, reduces comprehension and objective understanding of the world, and lowers trust among users. When information flow is selectively altered to make it more homogeneous, the user's rational and cognitive abilities become inoperable. Rational thinking cannot take place when facts are withheld or misrepresented. In such a situation, differences of opinion are increased, and communication barriers occur among different groups, resulting in further narrowing of information bandwidth and the creation of an information “cocoon” around the users, producing cognitive dissonance in the group and increased communication difficulties ( Hargittai and Hsieh, 2013 ). When the differences in values between groups are constantly expanding, negative emotions are likely to occur. To address this, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3a: II has a significant positive impact on DD.

H3b: II has a significant positive effect on negative emotions.

Digital Distrust

The Pew Research Center released a study entitled “The Future of Well-Being in a Tech-Saturated World” in April 2018 ( Janna and Lee, 2018 ). In the report, DD was defined for the first time as exclusion among digital technology users. When people believe that others are better than themselves, DD will reduce individual initiative and intensify the further weaponization of shock, fear, anger, humiliation, and other emotions on the Internet, thus causing disagreement and questioning ( Judith, 2016 ). People's positive emotion is the mental state represented as “trust,” whereas the negative emotion is the mental state represented by “distrust” ( Sha et al., 2015 ). DD can divide users, create negative emotions, and potentially tear society apart, making negative behavior such as cyber violence more likely to occur. Consequently, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H4: DD has a significant positive effect on negative emotions.

H5: DD has a significant positive effect on cyber violence.

Negative Emotions

Negative stimuli can produce negative emotions ( Liu and Liu, 2013 ). In the Internet environment, users' negative emotions include regret, anxiety, fear, disgust, irritability, etc. ( Ruensuk et al., 2019 ). In his research on China's cyber violence from the perspective of initiators and participants, Hou and Li (2017) showed that the motivations for cyber violence could be divided into moral judgments and cathartic malicious attacks, arising from cathartic emotions. The Internet provides a convenient place for people to vent their emotions, but if this is done carelessly, it can result in the rapid spread of negative feelings and the instigation of cyber violence. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Negative emotions have a significant positive effect on cyber violence.

The Mediating Role of Digital Distrust

For products that they have purchased, consumers often post comments or reviews in which they rate the item positively or negatively according to their experience with it. The negative deviation theory states that negative information can have a powerful deterrent effect on users, in contrast to positive or neutral information. Other researchers ( Zhu et al., 2020 ) found that positive information was considered more trustworthy than negative information. Furner and Zinko (2017) studied the influence of IO on the development of trust and purchase intention based on online product reviews in a mobile vs. web context. The results confirmed that IO had a strong influence on trust. Furner Christopher et al. (2016) revealed an association between IO, trust, and purchase intention. A recent study ( Zhu et al., 2020 ) supported the idea of a mediating role of trust and satisfaction between information quality, social presence, and purchase intention. Therefore, this article proposed the following hypothesis:

H7: DD mediates the relationship between information and CO and II.

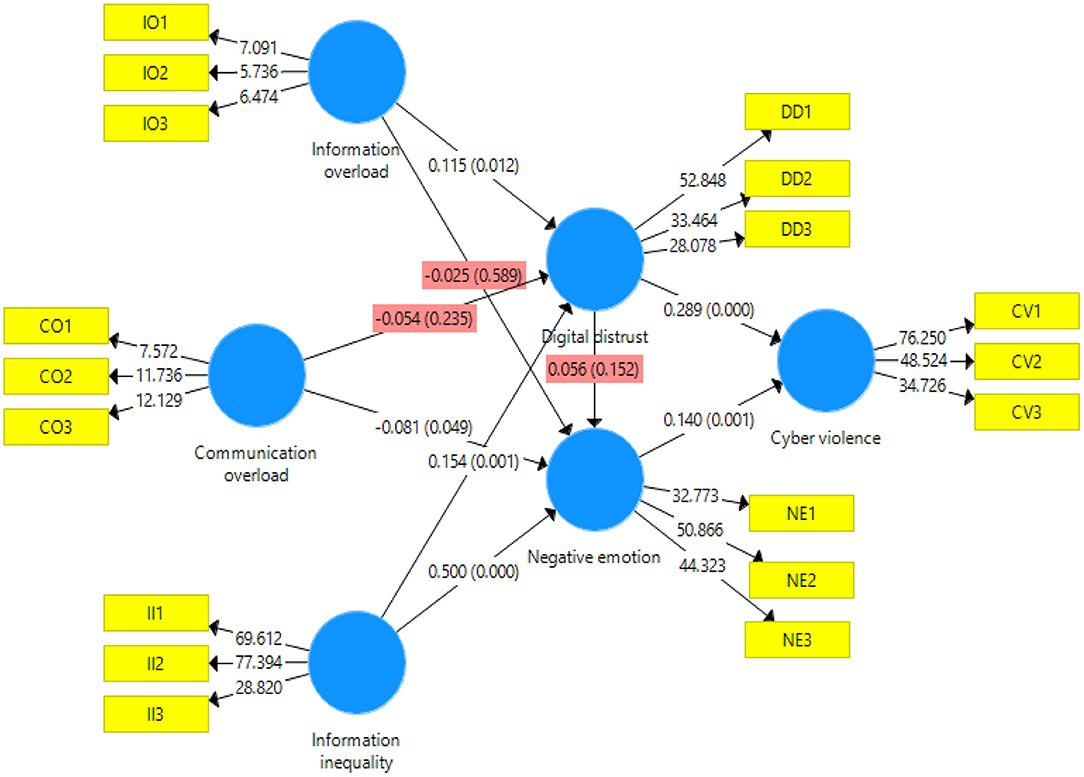

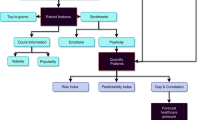

Our SOR-based cyber violence mechanism model constructed according to the above assumptions is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Theoretical model.

Research Methodology

Sample and procedure.

A sample of 531 was obtained from general public using a convenient random sampling approach because of time and budget constraints. A closed-ended questionnaire was administered by email and through online platforms such as WeChat and WhatsApp. Online surveys are often used when the population is large ( Tian et al., 2020 ). Authenticated online surveys are considered a valid tool for new research and provide a fast, simple, and less costly approach to collecting data ( Qalati et al., 2021 ). The formal survey was designed and conducted from February 2020 to April 2020, and the major reason for collecting data in 4 months' lag time was to mitigate common method bias (CMB) ( Li et al., 2020 ). In the present study, 783 questionnaires were collected from a general audience, of which 252 were invalidated because of a selection of the same option and the use of the same IP for the response. This left 531 valid questionnaires for an effective response rate of 67.82%.

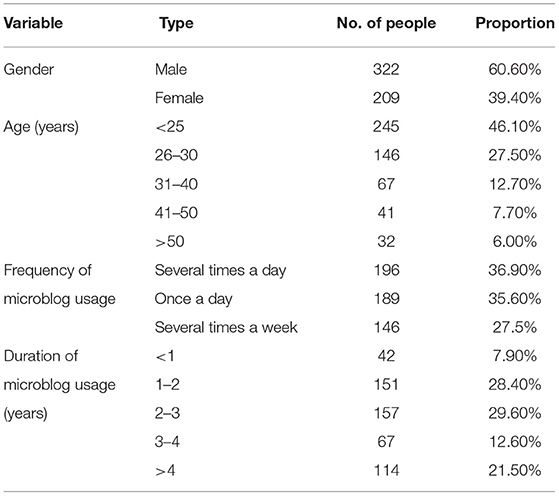

Respondents' Information

Table 1 reflects that a total of 322 male and 209 female participants accounted for 60% and 40%, respectively. Respondents younger than 25 (245), 26–30 (146), 31–40 (67), 41–50 (41), and older than 50 years accounted for 46.1, 27.5, 12.7, 7.7, and 6%, respectively. Regarding the frequency of microblog usage, approximately more than one-third of participants accounted for once a day (35.6%) and several times a day (36.9%), whereas more than one-quarter of them (27.5%) for several times a week. Regarding the duration of microblog usage under a year (42), 1–2 (151), 2–3 (157), 3–4 (67), and more than 4 (114) years accounted for 7.9, 28.4, 29.6, 12.6, and 21.5%, respectively.

Table 1 . Descriptive statistics.

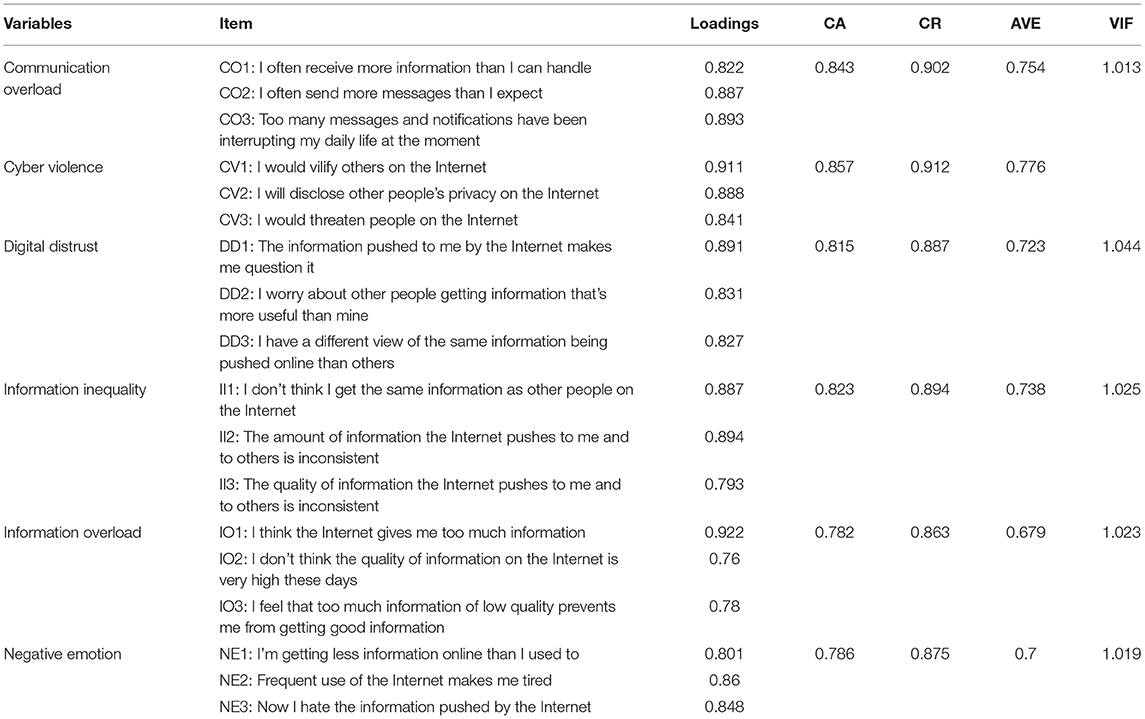

The study used seven-point Likert scales (1 = very unimportant to 7 = very important) to record responses. A pilot survey containing 21 questions was first conducted to validate the questionnaire method. After analyzing and discussing the pilot study results with experts, the questions, wording, and semantics of the questionnaire were modified, resulting in a final list of 18 items that were issued as the formal questionnaire ( Table 3 ). IO was measured using three items from Karr-Wisniewski and Lu (2010) , Lee et al. (2016) . CO was assessed using three items ( Cho et al., 2011 ; Lee et al., 2016 ; Shi et al., 2020 ). II was measured using three items adapted from Lee et al. (2016) and Yu et al. (2017) . DD was measured using three items from Zhu et al. (2020) . Negative emotions were assessed using three items adapted from Kang et al. (2013) and Chiu et al. (2020) , and cyber violence was assessed using three items from Lee et al. (2016) and Sari and Camadan (2016) .

Data Analysis

To consider the influence of multiple variables on the model and verify the validity of the theoretical hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the data. SPSS 24.0 and SmartPLS 3.2.8 were the statistical software used in the study. In particular, SPSS was used for descriptive information of the participants and some test related to CMB and sample adequacy, whereas SmartPLS 3.0 was used for partial least squares (PLS) SEM because it is widely used across fields ( Hair Joseph et al., 2019 ; Ahmed et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, it is considered a comprehensive software program with an intuitive graphical user interface to run PLS-SEM analysis, which certainly has had a massive impact. Besides, it enables the specification of complex interrelationships between observed and latent constructs ( Hair Joseph et al., 2019 ).

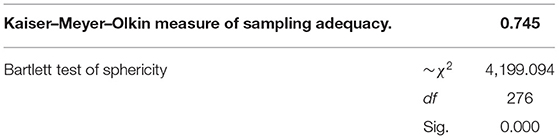

Common Method Bias and Bartlett Spherical Test

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value and Bartlett spherical test value of sample data were calculated. The KMO value was 0.745, the chi-squared value was 4,199.094, the degrees of freedom were 276, and the p < 0.001 ( Table 2 ). The larger the KMO value, the stronger the correlation between variables. The variables were suitable for factor analysis, and the structural validity between variables was good ( Chen et al., 2016 ). This study used three approaches to detect the CMB. First, Harman's single factor test stated that the first factor represents only 16.18% of the variance, which is far below the acceptable threshold (50.0%) ( Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). Second, variance inflation factor (VIF), which is called the full-collinearity approach using SmartPLS ( Ali Qalati et al., 2021 ), requires to be ≤ 3 ( Hair Joseph et al., 2019 ) ( Table 3 ). Third, Bagozzi et al. (1991) proposed that if the correlation among the constructs was >0.9, there is evidence of CMB. However, none of the constructs was found to be greater than the minimum cutoff value ( Table 4 ).

Table 2 . KMO and Bartlett test.

Table 3 . Measurement model.

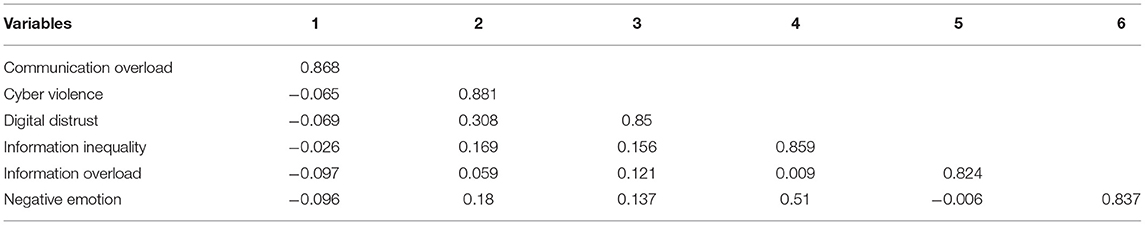

Table 4 . Discriminant validity.

Measurement Model

According to Roldán and Sánchez-Franco (2012) , a proposition to measure the model is required to assess the individual items for reliability, internal consistency, content validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Individual item reliability was measured by outer loadings of items related to a particular dimension ( Hair et al., 2012 ). Hair et al. (2016) recommended that factor loading should be between 0.40 and 0.70, whereas Hair et al. (2017) proposed a value of ≥0.7 ( Table 3 ). According to Nunnally (1978) , Cronbach α values should exceed 0.7: the threshold values of constructs in this study ranged between 0.782 and 0.857. The internal consistency reliability ( Bagozzi and Yi, 1988 ) required that the composite reliability (CR) be ≥0.7, and the CR coefficient values in this study were between 0.863 and 0.912. Regarding convergent validity, Fornell and Larcker (1981) recommended that the average variance extracted (AVE) should be ≥0.5. The AVE values in this study were between 0.679 and 0.776, confirming a satisfactory level of convergent validity. With regard to discriminant validity, Fornell and Larcker (1981) stated that the square root of the AVE for each construct should exceed the correlation of the construct with other model constructs. Table 4 gives the discriminant validity of the results.

Structural Model

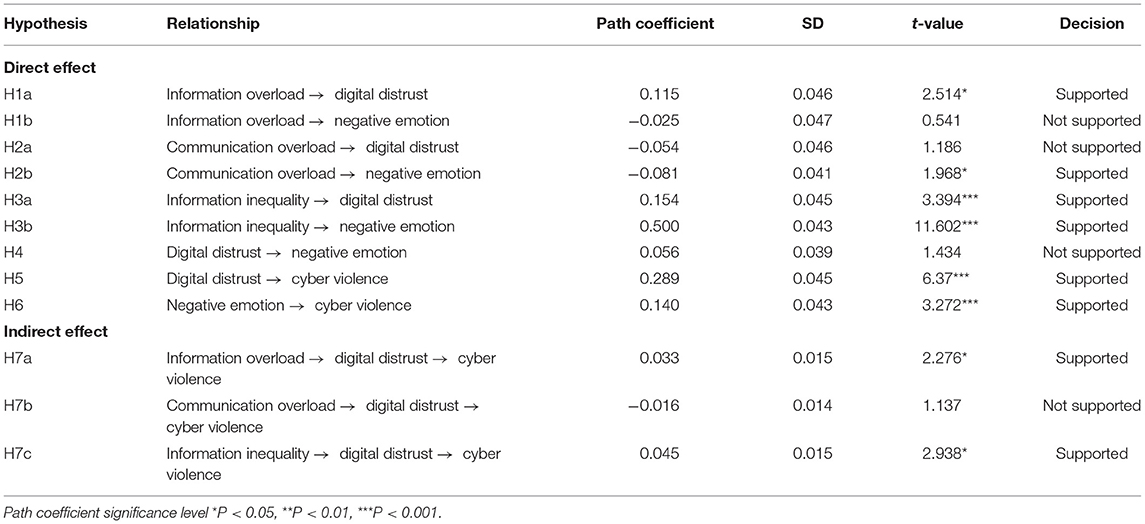

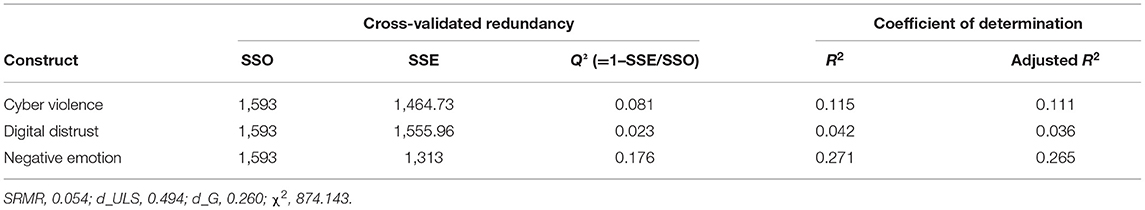

In this article, SmartPLS 3.2.8 was used to estimate the path coefficient and verify the hypothesis. This article used PLS bootstrapping with 5,000 bootstraps for the 531 cases to demonstrate results associated with the path coefficients and their significance level ( Table 5 ). Among them, H1a, H2b, H3a, H3b, H5, H6, H7a, and H7c passed the significance test. However, the path coefficient of H2b was −0.081, which proves the hypothesis stating that CO had a significant negative impact on negative emotions, but it is very close to the rejection cutoff. The model path analysis found that the hypotheses, H1b, H2a, H4, and H7b, were not valid. The graphical presentation of the model with path and significance level is shown in Figure 2 . The results can be interpreted to conclude that IO and II have a significant positive impact on DD and that II has a significant positive effect on negative emotions. CO has a significant negative impact on negative emotions. DD and negative emotions have a significant positive effect on cyber violence. According to Zhao et al. (2010) , there are five types of mediation: complementary, competitive, indirect only, direct only, and no effect (non-mediated). The authors stated that if the mediated effect ( a × b ) and direct effect c both exist and point in the same direction, it is called complementary mediation. The evidence from this study proves that DD is a complementary mediator. There is no global measure of goodness of fit in SmartPLS-SEM ( Hair et al., 2011 ).

Table 5 . Path coefficients and hypothesis testing.

Figure 2 . Structural equation modeling.

According to Cohen (1988) , R 2 values of 0.60, 0.33, and 0.19 are, respectively, substantial, moderate, and weak. However, Falk and Miller (1992) argued that an R 2 value as low as 0.10 is also acceptable. The R 2 value for this study was 0.115 for cyber violence. This suggests that DD and negative emotion explain 11.5% of the variation ( Table 6 ), as the R 2 -value is sufficiently above the minimum cutoff according to Falk and Miller (1992) . This study also employed the cross-validated redundancy measure ( Q 2 ) to evaluate the model. Henseler et al. (2009) suggested that a Q 2 > 0 shows that the model has predictive relevance. Values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, indicate that an exogenous construct has a small, medium, or considerable predictive relevance for a specific endogenous construct. The current study's model has weak predictive relevance for cyber violence and DD and medium for negative emotions ( Table 6 ).

Table 6 . Strength of the model.

Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was used to assess the goodness of fit. SRMR is an absolute measure of fit: a value of zero indicates a perfect fit, and a value of <0.08 is considered a good fit ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ). In this study, the SRMR value obtained was 0.054, which is well-below the minimum cutoff ( Table 6 ).

Utilizing the results from 531 valid questionnaires, five of the nine hypotheses regarding the mechanism of cyber violence in this article were verified, and all of them were significantly correlated. IO and II have a significant positive impact on DD, as supported by hypotheses H1a and H3a. Thus, digital users need to sift through the overload of information in order to dispel doubts and prevent disagreements with others. Because the user has gradually lost control of information access, effective information acquisition is more difficult. This results in a growing divergence between users that eventually creates DD. There are two main reasons for this. On the one hand, it is one of the characteristics of the digital age that information redundancy and information quality decline when IO exists. On the other hand, digital users have come to see that technological empowerment in the digital era has resulted in information control. This may manifest as problems such as living in an information cocoon and being subject to algorithm discrimination, which prevents users from obtaining the full complement of information and using it for production and creation. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies. II (path coefficient = 0.149) has a slightly stronger effect on DD than IO (path coefficient = 0.114). This demonstrates that the control of information by businesses empowered by digital technology has emerged as a growing threat to online shoppers and social media users. Therefore, improving information quality, reducing redundancy, and strengthening users' rights to access all information will help to reduce DD.

II has a significant positive impact on negative emotions, as supported by our findings in support of H3b. The more that digital users feel the unequal power of information control, the stronger their negative emotions will be. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies. The development of a digital society has led users to pay more attention to the value of information. Possessing excellent opportunities for searching, processing, and analyzing information is the sine qua non for success in social competition. However, when information access and distribution are deliberately manipulated over a period of time, conflicts among social groups will grow, and their mutual interests will diverge to the point where the different social groups may be torn apart, and severe negative social emotions will be the result. To prevent this from happening, stricter limits on information control by businesses need to be enacted and enforced. Internet users should be given equal access to and use of information to reduce differences of opinion and communication barriers between different groups to eliminate negative emotions.

DD and negative emotions have a significant positive impact on cyber violence, supported by findings from the H5 and H6 paths. The more serious the doubts and differences among digital users, the stronger will be the associated negative emotions, and the more serious the online violence. Compared with negative emotions (path coefficient = 0.176), DD has a higher degree of influence (path coefficient = 0.322), which indicates that the causes of cyber violence are not only the negative emotions associated with the emotional catharsis of users, but the doubts and disagreements between users that have become embedded in their minds. The goal, then, is the construction of a free and fair communication channel between users, eliminating doubts and disagreements, providing a clean and honest Internet environment, to stop negative emotions and cyber violence.

CO negatively affects negative emotions but is inconsistent with the H2b hypothesis, so the path is not supported. This suggests that digital users believe that negative emotions and behavior do not increase even in the presence of unmanageable communication and IO. This conclusion is inconsistent with previous studies, which may be due to the fact that CO has been widely perceived as an emerging social problem. However, compared with the more prominent problematic Internet use or social network addiction, it appears to have a lower impact and is easily ignored ( Gui and Büchi, 2019 ). In addition, academic research results on the correlation between CO and negative emotions are inconsistent. For example, Chen and Lee concluded that CO caused by too frequent use of Facebook produced anxiety ( Chen and Lee, 2013 ), whereas Jelenchick et al. found that the constant use of this social network on the university campus had nothing to do with anxiety ( Jelenchick et al., 2013 ). Therefore, the conclusions drawn from this article should be tempered by the consideration that Chinese digital users may not have a systematic understanding of CO, and the results may be related to the type of Internet platform and study group, as well as their environment and cultural background.

In this article, H1b, H2a, H4, and H7b were not verified; however, that does not mean that IO has no effect on negative emotions or that CO does not foster DD. DD had no effect on negative emotions and no mediating effect between CO and cyber violence. There are many possible reasons for the lack of verification of the hypotheses, but these will have to be pursued in subsequent studies. The conclusions from this investigation are that to circumvent the generation of cyber violence based on the perspective of individual users, more attention should be paid to the influence of IO, II, DD, and negative emotions, as well as their significant correlation.

Theoretical Implications

This study has several theoretical implications and makes a significant contribution to the existing literature on cyber violence. First, prior studies have paid more attention to information quality and less to the cumulative effects of IO, CO, and II. Second, this study leverages the application of the SOR model to the online environment, where the responses can be treated as new stimuli. Third, this study is grounded on the SOR theory to explain the intrinsic association between information, communication, II, and DD, negative emotions, and cyber-violence behavior. It should be noted that CO is not a significant antecedent of either DD or negative emotion, whereas IO and inequality comprise significant drivers of both. Our findings highlight the important mediating role of DD and negative emotions, revealing the clear association between an individual's perceptions of the digital world and its power to generate negative emotions. Therefore, this study can be considered as a new approach to understanding the path from stimuli such as IO, CO, and II to Internet behavior mediated by DD and negative emotions in the context of e-commerce.

Practical Implications at the National, Enterprise, and Individual Level

At the national level, the government and relevant departments should impose new laws and regulations to clearly define the boundaries of information rights and interests between enterprises and users and to ensure that all users share equally in the access to information. The government need to be more proactive in regulating the network environment, establishing a spam tracing mechanism, punishments for deliberate misinformation, and controls on the generation and dissemination of low-quality, redundant information. Digital users should be encouraged to communicate with the authorities about incipient problems before they become a source of differences and doubts. Purging social groups of negative emotions necessitates the creation of a positive Internet ecosystem.

At the enterprise level, emerging Internet businesses need to establish the survival logic of “maximization of users' rights and interests rather than profit maximization.” Managers need to reconfigure the enterprise's value system and ease up on the control of information access and distribution to restore users' information rights and interests. The corporate Internet information review system needs to replace the production and diffusion of useless information with diversified high-quality information, to help users understand the world and reach a social consensus. More attention should be paid to users' emotional needs, and the engendering of negative emotions by the media should be stopped.

At the individual level, users should maintain a positive and optimistic attitude, but still be alert to the formation of information cocoons and algorithmic discrimination. They should take steps to enhance their information literacy, effectively identify and filter out low-quality information, and cultivate their information search and analysis ability. Their goals should be to strengthen their level of self-cognition, objectively view the self's need for information, conscientiously obtain objective information from multiple channels and points of view, and strive to reduce doubts and disagreements.

The theoretical model developed in this article is applicable to the analysis of the mechanism of cyber violence and provides the basis for a reasonable explanation of the formation of DD and negative emotions, which can be further explored in future studies.

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

This study has certain limitations that highlight avenues for future research. We used a convenient random sampling approach because of budget and time constraints. Collecting data from China only limits our findings' generalizability, and future studies should employ a cross-cultural approach to investigate the causes of cyber-violence behavior. As data were collected through an online survey, which also impedes the generalizability of findings in other countries, thus we call for future studies to include field surveys. The questionnaire survey scope could be expanded to increase the accuracy of the research results, as the sample size and reach may also be considered a limitation. Future studies could also investigate the effects of the government's policy on the mechanism.

The selection of research variables could be further subdivided into the internal environment and external environment variables to probe more deeply into the etiology of network violence. The follow-up will continue to analyze the above issues in detail to provide more theoretical and practical guidance for research on cyber violence.

Comparative studies could also be performed to validate our results and expand application of the proposed model using organizations and small- and medium-sized enterprises. This study did not examine the relationship between participants' attitudes, DD, negative emotions, and intentions, and future programs should investigate the influence of participant's attitudes and intentions. Finally, the mediating role of DD and negative emotions should be explored further.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Jiangsu University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This study is supported by National Statistics Research Project of China (2016LY96).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahmed, N., Li, C., Qalati, S. A., Rehman, H. U., Khan, A., and Rana, F. (2020). Impact of business incubators on sustainable entrepreneurship growth with mediation effect. Entrep. Res. J . 1–23. doi: 10.1515/erj-2019-0116

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ali Qalati, S., Li, W., Ahmed, N., Ali Mirani, M., and Khan, A. (2021). Examining the factors affecting SME performance: the mediating role of social media adoption. Sustainability 13:75. doi: 10.3390/su13010075

Asif Naveed, D.-M., and Anwar, M. (2020). Towards information anxiety and beyond. Webology 17, 65–80. doi: 10.14704/WEB/V17I1/a208

Backe, E. L., Lilleston, P., and Mccleary-Sills, J. (2018). Networked individuals, gendered violence: a literature review of cyberviolence. Viol. Gender 2018, 135–146. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0056

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 16, 74–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02723327

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q . 36, 421–458. doi: 10.2307/2393203

Cao, X., and Sun, J. (2017). Exploring the effect of overload on the discontinuous intention of social media users: an S-O-R perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav . 81, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.035

Chen, W., and Lee, K. H. (2013). Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 16, 728–734. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0272

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, X.-S., Chen, G.-F., and Zhang, R. (2016). Research on the relationship between the index structure of journal evaluation based on factor analysis and SEM model. Informat. Sci. 34, 61–64. doi: 10.13833/j.cnki.is.2016.10.011

CrossRef Full Text

Cheng, W.-Y., Cao, J.-D., and Lu, S.-Y. (2014). Revision of information anxiety scale. Information 33, 6–9. doi: 10.13833/j.cnki.is.2014.01.014

Cheung, A. S. Y. (2009). A study of cyber-violence and internet service providers' liability: lessons from China. Pacific Rim Law & Policy J. 18, 323–346.

Google Scholar

Chiu, H. T., Yee, L. T. S., Kwan, J. L. Y., Cheung, R. Y. M., and Hou, W. K. (2020). Interactive association between negative emotion regulation and savoring is linked to anxiety symptoms among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 68, 494–501. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1580712

Cho, J., Ramgolam, D. I., Schaefer, K. M., and Sandlin, A. N. (2011). The rate and delay in overload: an investigation of communication overload and channel synchronicity on identification and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 39, 38–54. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2010.536847

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Congard, A., and Carole, R. (2020). Measuring Situational Anxiety Related to Information Retrieval on the Web Among English-Speaking Internet Users . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Falk, R. F., and Miller, N. B. (1992). A Primer for Soft Modeling. Akron, OH: University of Akron Press.

Figueiredo, A. (2018). “Information frictions in education and inequality,” in 2018 Meeting Papers (Mexico City).

Finlay, C. J. (2018). Just war, cyber war, and the concept of violence. Philos. Technol. 31, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s13347-017-0299-6

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Furner Christopher, P., Zinko, R., and Zhu, Z. (2016). Electronic word-of-mouth and information overload in an experiential service industry. J. Serv. Theo. Pract. 26, 788–810. doi: 10.1108/JSTP-01-2015-0022

Furner, C. P., and Zinko, R. A. (2017). The influence of information overload on the development of trust and purchase intention based on online product reviews in a mobile vs. web environment: an empirical investigation. Electro. Markets 27, 211–224. doi: 10.1007/s12525-016-0233-2

Gui, M., and Büchi, M. (2019). From use to overuse: digital inequality in the age of communication abundance. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 39:089443931985116. doi: 10.1177/0894439319851163

Hair Joseph, F., Risher Jeffrey, J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle Christian, M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Euro. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theo. Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Pieper, T. M., and Ringle, C. M. (2012). The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: a review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 45, 320–340. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2012.09.008

Hair, J. F. Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2016). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.15358/9783800653614

Hair, J. F. Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., and Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Hargittai, E., and Hsieh, Y. P. (2013). “Digital inequality,” The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies , ed W. H. Dutton (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 129–150. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199589074.013.0007

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). “The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing,” in New Challenges to International Marketing . Emerald Group Publishing Limited (Bingley). doi: 10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Hou, Y., and Li, X. (2017). Cyber violence in China: its influencing factors and underlying motivation. J. Pek. Univers. 54, 101–107.

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. Multidiscipl. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Janna, A., and Lee, R. (2018). The Future of Well-Being in a Tech-Saturated World . Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/04/17/the-future-of-well-being-in-a-tech-saturated-world/

Jelenchick, L. A., Eickhoff, J. C., and Moreno, M. A. (2013). “Facebook Depression?” Social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 52, 128–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.008

Judith, D. (2016). The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online. Cambridge: Leonardo.

Kang, Y. S., Min, J., Kim, J., and Lee, H. (2013). Roles of alternative and self-oriented perspectives in the context of the continued use of social network sites. Int. J. Informat. Manage. 33, 496–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.12.004

Karr-Wisniewski, P., and Lu, Y. (2010). When more is too much: operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26, 1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.008

Lee, A. R., Son, S.-M., and Kim, K. K. (2016). Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: a stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.011

Li, H., Zeng, L., and Teng, S. (2017). Research on the development of network violence:intension and type,status characteristics and governance measures——an analysis based on the cases of network violence during 2012-2016. J. Intelli. 36, 139–145.

Li, W., Qalati, S. A., Khan, M. a,.S, Kwabena, G. Y., Erusalkina, D., et al. (2020). Value co-creation and growth of social enterprises in developing countries: moderating role of environmental dynamics. Entrepren. Res. J . 1–28. doi: 10.1515/erj-2019-0359

Liu, Z.-M., and Liu, L. (2013). Public negative emotion model in emergencies based on aging theory. J. Indust. Eng. Eng. Manage. 27, 15–21. doi: 10.13587/j.cnki.jieem.2013.01.008

Mcfarlane, D. (1998). Interruption of People in Human-Computer Interaction. Washington, DC: The George Washington University

Mcfarlane, D., and Latorella, K. (2002). The scope and importance of human interruption in human-computer interaction design. Humancomput. Interact. 17, 1–61. doi: 10.1207/S15327051HCI1701_1

Mehrabian, A., and Russell, J. A. (1974). An Approach to Environmental Psychology . Cambridge: MIT.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric Methods . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

O'Connail, B., and Frohlich, D. (1995). “Timespace in the workplace: dealing with interruptions,” in Proceedings of the Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Denver, CO), 262–263. doi: 10.1145/223355.223665

Owen, T., Noble, W., and Speed, F. (2017). “Biology and cybercrime: towards a genetic-social, predictive model of cyber violence,” in New Perspectives on Cybercrime (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 27–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-53856-3_3

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88:879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Qalati, S. A., Vela, E. G., Li, W., Dakhan, S. A., Hong Thuy, T. T., and Merani, S. H. (2021). Effects of perceived service quality, website quality, and reputation on purchase intention: the mediating and moderating roles of trust and perceived risk in online shopping. Cog. Bus. Manage. 8:1869363. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2020.1869363

Roldán, J. L., and Sánchez-Franco, M. J. (2012). “Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research,” in Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 193–221. doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-0179-6.ch010

Rong, Y. (2010). On knowledge and information service oriented to information anxiety. Informat. Stud. Theo. Applicat. (Beijing). 32, 64–67. doi: 10.16353/j.cnki.1000-7490.2010.05.010

Ruensuk, M., Oh, H., Cheon, E., Oakley, I., and Hong, H. (2019). “ Detecting Negative Emotions During Social Media Use on Smartphones,” in Asian HCI Symposium'19 (Glasgow). doi: 10.1145/3309700.3338442

Sari, S. V., and Camadan, F. (2016). The new face of violence tendency:cyber bullying perpetrators and their victims. Comput. Hum. Behav. 59, 317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.027

Sha, Y., Yan, J., Wang, Z., and Management S. O. University L. Management S. O. (2015). Public trust on the red cross society of China after Ya'an earthquake—analysis based on sentiment analysis of microblog data. J. Public Manage. 12, 93–104. doi: 10.16149/j.cnki.23-1523.2015.03.009

Shi, C., Yu, L., Wang, N., Cheng, B., and Cao, X. (2020). Effects of social media overload on academic performance: a stressor–strain–outcome perspective. Asian J. Commun. 30, 179–197. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2020.1748073

Sincek, D., Duvnjak, I., and Mili, M. (2017). Psychological outcomes of cyber-violence on victims, perpetrators and perpetrators/victims. Hrvat. Revija Za Rehabili. Istrai. 53:98. doi: 10.31299/hrri.53.2.8

Syastra, M., and Wangdra, Y. (2018). Analisis online impulse buying dengan menggunakan framework SOR. J. Sist. Inform. Bisnis 8:19. doi: 10.21456/vol8iss2pp133-140

Tian, H., Iqbal, S., Akhtar, S., Qalati, S. A., Anwar, F., Khan, M., et al. (2020). The impact of transformational leadership on employee retention: mediation and moderation through organizational citizenship behavior and communication. Front. Psychol. 11:314. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00314

Tripathy, S., Aich, S., Chakraborty, A., and Lee Gyu, M. (2016). Information technology is an enabling factor affecting supply chain performance in Indian SMEs: a structural equation modelling approach. J. Model. Manage. 11, 269–287. doi: 10.1108/JM2-01-2014-0004

Xie, Y., Li, L., Qin, Y., Dun, H., and University H. (2019). A literature review of employee grievance and prospects based on SOR theory framework. Chin. J. Manage. 16, 783–790.

Yu, T.-K., Lin, M.-L., and Liao, Y.-K. (2017). Understanding factors influencing information communication technology adoption behavior: the moderators of information literacy and digital skills. Comput. Hum. Behav. 71, 196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.005

Zhang, B., and Lin, J.-B. (2017). The influence factor of consumers′adverse selection in the context of food harm:based on the perspective of SOR theory. Stats Inform. Forum 32, 116–123.

Zhang, Y. (2012). The violent tendency of internet public opinion and countermeasures. J. Intelli. 31, 86–90.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G. Jr, and Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering baron and kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 37, 197–206. doi: 10.1086/651257

Zhu, L., Li, H., Wang, F.-K., He, W., and Tian, Z. (2020). How online reviews affect purchase intention: a new model based on the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework. Aslib J. Inform. Manage. 72, 463–488. doi: 10.1108/AJIM-11-2019-0308

Keywords: cyber violence, information overload, communication overload, information inequality, digital distrust, negative emotions, SOR theory

Citation: Fan M, Huang Y, Qalati SA, Shah SMM, Ostic D and Pu Z (2021) Effects of Information Overload, Communication Overload, and Inequality on Digital Distrust: A Cyber-Violence Behavior Mechanism. Front. Psychol. 12:643981. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643981

Received: 19 December 2020; Accepted: 10 March 2021; Published: 20 April 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Fan, Huang, Qalati, Shah, Ostic and Pu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sikandar Ali Qalati, 5103180243@stmail.ujs.edu.cn ; sidqalati@gmail.com

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness

Recently, social media has become a platform for cyber violence. This issue primarily concerns public health and is associated with adverse mental or physical outcomes. As a result, cyberbullying is one of the top contemporary problems that needs to be approached from different angles to be resolved entirely. The purpose of this paper is to review several articles concerning cyber violence and draw a conclusion about their structures and effectiveness.

The first article is named Cyber violencitsat do we know and where do we go from here? and written by J. Peterson and J. Densley. The report is published in a journal called Aggression and Violent Behaviour in May 2017. The primary method the authors use is the selection and analysis of the already extant materials and sources related to the topic. It denotes that the authors resorted to the second type of research, which represents utilizing the existing articles and library sources to provide evidence-based theory. The material is well structured and has all the organizational components (introduction, main body, and conclusion). The authors introduce the acuteness of cyber violence to the reader, represent individual, group, and environmental explanations of the phenomenon, and investigate different approaches towards the issue (Peterson & Densley, 2017). Therefore, to my mind, this article is wisely structured, and all the elements are interrelated. I find it appealing due to the authors’ ability to apply theoretical material to ground their standpoint.

The second article is named Adolescent cyberbullying: A review of characteristics, prevention, and intervention strategies. It was posted in the journal Aggression and Violent Behavior in 2015 by R. Ang. The methods used in the text include firm reliance on secondary scientific research. The article has a logical organization of paragraphs, and it is easy to navigate throughout the whole paper. The author investigates adolescent cyber violence and thinks of it in terms of adults’ tendency to be involved in high-risk behaviors (Ang, 2015). While explaining the point of view, the author uses different variables associated with cyberbullying and parent-adult behavior to establish the relation between them. In the climax part of the article, the author suggests the strategies for better protection of adolescents online. I found this article quite convincing due to the strong scientific base, the author’s ability to analyze the dependence between the variables, and present the guidelines for the issue which were presented in an understandable manner.

The third article is entitled Cyberbullying prevention and intervention efforts: current knowledge and future direction and was issued in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry in 2016 by D. Espelageand J. Hong. The methodology comprises the implementation of scientific articles that include results of surveys and experiments and theoretical underpinnings. The structure of the material seems well organized as it contains the main elements. Though the introduction and the conclusion are missing, the reader can clearly understand that other paragraphs substitute these parts. The authors described the present situation concerning the spread of cyber harassment, explained the extant preventive methods, exemplified the efficacy of school-based cyberbulextentinterventions, and expressed their attitude towards future prevention programs. According to Espelageand and Hong (2016), future researches must attract health care workers to prevent long-term health consequences. Thus, I consider this article relevant as it gives much information to reflect upon and has strong scientific underpinnings.

The fourth article stands under the title Out of the beta phase: Obstacles, challenges, and promising paths in the study of cyber criminology. The paper was issued in 2015 in the International Journal of Cyber Criminology by B. Diamond and M. Bachmann. The article’s organization follows the standards of a scientific article outline; therefore, one may orientate well throughout the paper. The methodology implemented relates to the second type of research, which is based on using extant scientific evidence. The article provides an overview of the present state of cyber criminology and views it from the aspects of teaching, research, and theory. The author suggested that there are still not enough pieces of evidence concerning the behavioral side behind cyber violence. In my opinion, this article is decent as it vividly discloses the study of cyber criminology and significantly explained why cyberbullying will be the main focus of it.

The fifth article is called the Effects of the cyberbullying prevention program media heroes (Medienhelden) on traditional bullying. The paper was published in the journal named Aggressive Behavior in 2016 by several authors: E. Chaux, A. Velásque, A. Schultze-Krumbholz, and H. Scheithauer. The authors used the methods of pretest–post-test quantitative experimental evaluation of the program, and to underpin the results, they use the theoretical base. The paper’s structure is well organized and comprises additional elements for the experiment part. The study focuses on analyzing the spillover effects of the cyber violence preventive programs named Media Heroes on conventional bullying. This prevention program aims to promote empathy, awareness of risks and their repercussions, and strategies that would help to defend the victims. In my opinion, this article may be an excellent example of a research work that other researchers may use to support their evidence.

Ang, R. P. (2015). Adolescent cyberbullying: A review of characteristics, prevention, and intervention strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 35–42. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.011

Espelage, D. L., & Hong, J. S. (2016). Cyberbullying Prevention and Intervention Efforts: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62 , 6, 374–380. doi:10.1177/0706743716684793

Chaux, E., Velásquez, A. M., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., & Scheithauer, H. (2016). Effects of the cyberbullying prevention program media heroes (Medienhelden) on traditional bullying . Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 157–165. doi:10.1002/ab.21637

Diamond, B., & Bachmann, M. (2015). Out of the beta phase: obstacles, challenges, and promising paths in the study of cyber criminology. International Journal of Cyber Criminology , 9, 1, 24–34.

Peterson, J., & Densley, J. (2017). Cyber violence: What do we know and where do we go from here? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 193-200.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, February 2). Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness. https://studycorgi.com/cyber-violence-structures-and-effectiveness/

"Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness." StudyCorgi , 2 Feb. 2022, studycorgi.com/cyber-violence-structures-and-effectiveness/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness'. 2 February.

1. StudyCorgi . "Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness." February 2, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/cyber-violence-structures-and-effectiveness/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness." February 2, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/cyber-violence-structures-and-effectiveness/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness." February 2, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/cyber-violence-structures-and-effectiveness/.

This paper, “Cyber Violence: Structures and Effectiveness”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: October 30, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

UConn Today

- School and College News

- Arts & Culture

- Community Impact

- Entrepreneurship

- Health & Well-Being

- Research & Discovery

- UConn Health

- University Life

- UConn Voices

- University News

April 19, 2021 | Caitlin Elsaesser, Assistant Professor of Social Work

How Social Media Turns Online Arguments Between Teens Into Real-World Violence

Social media isn’t just mirroring conflicts happening in schools and on streets – it’s triggering new ones

Common social media practices like commenting and tagging can exacerbate arguments among teens and in some cases lead to violence (Adobe Stock).

The deadly insurrection at the U.S. Capitol in January exposed the power of social media to influence real-world behavior and incite violence. But many adolescents, who spend more time on social media than all other age groups, have known this for years.

“On social media, when you argue, something so small can turn into something so big so fast,” said Justin, a 17-year-old living in Hartford, during one of my research focus groups. (The participants’ names have been changed in this article to protect their identities.)

For the last three years, I have studied how and why social media triggers and accelerates offline violence . In my research , conducted in partnership with Hartford-based peace initiative COMPASS Youth Collaborative , we interviewed dozens of young people aged 12-19 in 2018. Their responses made clear that social media is not a neutral communication platform.

In other words, social media isn’t just mirroring conflicts happening in schools and on streets – it’s intensifying and triggering new conflicts. And for young people who live in disenfranchised urban neighborhoods, where firearms can be readily available, this dynamic can be deadly.

Internet Banging

It can result in a phenomenon that researchers at Columbia University have coined “internet banging.” Distinct from cyberbullying, internet banging involves taunts, disses, and arguments on social media between people in rival crews, cliques, or gangs. These exchanges can include comments, images, and videos that lead to physical fights, shootings and, in the worst cases, death .

It is estimated that the typical U.S. teen uses screen media more than seven hours daily, with the average teenager daily using three different forms of social media. Films such as “ The Social Dilemma ” underscore that social media companies create addictive platforms by design, using features such as unlimited scrolling and push notifications to keep users endlessly engaged.

According to the young people we interviewed, four social media features in particular escalate conflicts: comments, livestreaming, picture/video sharing, and tagging.

Comments and Livestreams

The feature most frequently implicated in social media conflicts, according to our research with adolescents, was comments. Roughly 80% of the incidents they described involved comments, which allow social media users to respond publicly to content posted by others.

Taylor, 17, described how comments allow people outside her friend group to “hype up” online conflicts: “On Facebook if I have an argument, it would be mostly the outsiders that’ll be hypin’ us up … ‘Cause the argument could have been done, but you got outsiders being like, ‘Oh, she gonna beat you up.’”

Meanwhile, livestreaming can quickly attract a large audience to watch conflict unfold in real time. Nearly a quarter of focus group participants implicated Facebook Live, for example, as a feature that escalates conflict.

Brianna, 17, shared an example in which her cousin told another girl to come to her house to fight on Facebook Live. “But mind you, if you got like 5,000 friends on Facebook, half of them watching … And most of them live probably in the area you live in. You got some people that’ll be like, ‘Oh, don’t fight.’ But in the majority, everybody would be like, ‘Oh, yeah, fight.’”

She went on to describe how three Facebook “friends” who were watching the livestream pulled up in cars in front of the house with cameras, ready to record and then post any fight.

Strategies to Stop Violence

Adolescents tend to define themselves through peer groups and are highly attuned to slights to their reputation. This makes it difficult to resolve social media conflicts peacefully. But the young people we spoke with are highly aware of how social media shapes the nature and intensity of conflicts.

A key finding of our work is that young people often try to avoid violence resulting from social media. Those in our study discussed four approaches to do so: avoidance, deescalation, reaching out for help and bystander intervention.

Avoidance involves exercising self-control to avoid conflict in the first place. As 17-year-old Diamond explained, “If I’m scrolling and I see something and I feel like I got to comment, I’ll go [to] comment and I’ll be like, ‘Hold up, wait, no.’ And I just start deleting it and tell myself … ‘No, mind my business.’”

Reaching out for support involves turning to peers, family or teachers for help. “When I see conflict, I screenshot it and send it to my friends in our group chat and laugh about it,” said Brianna, 16. But there’s a risk in this strategy, Brianna noted: “You could screenshot something on Snapchat, and it’ll tell the person that you screenshot it and they’ll be like, ‘Why are you screenshotting my stuff?’”

The deescalation strategy involves attempts by those involved to slow down a social media conflict as it happens. However, participants could not recount an example of this strategy working, given the intense pressure they experience from social media comments to protect one’s reputation.

They emphasized the bystander intervention strategy was most effective offline, away from the presence of an online audience. A friend might start a conversation offline with an involved friend to help strategize how to avoid future violence. Intervening online is often risky, according to participants, because the intervener can become a new target, ultimately making the conflict even bigger.

Peer Pressure Goes Viral

Young people are all too aware that the number of comments a post garners, or how many people are watching a livestream, can make it extremely difficult to pull out of a conflict once it starts.

Jasmine, a 15-year-old, shared, “On Facebook, there be so many comments, so many shares and I feel like the other person would feel like they would be a punk if they didn’t step, so they step even though they probably, deep down, really don’t want to step.”

There is a growing consensus across both major U.S. political parties that the large technology companies behind social media apps need to be more tightly regulated. Much of the concern has focused on the dangers of unregulated free speech .

But from the vantage point of the adolescents we spoke with in Hartford, conflict that occurs on social media is also a public health threat. They described multiple experiences of going online without the intention to fight, and getting pulled into an online conflict that ended up in gun violence. Many young people are improvising strategies to avoid social media conflict. I believe parents, teachers, policymakers and social media engineers ought to listen closely to what they are saying.

Originally published in The Conversation .

Recent Articles

April 26, 2024

New Alzheimer’s Treatment Available at UConn Health

Read the article

Marissa Salvo Named the 2024 School of Pharmacy Faculty Service Award Recipient

Mathew Chandy ’24, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

Cyber Violence Essays

Essay on cyber violence, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 November 2022

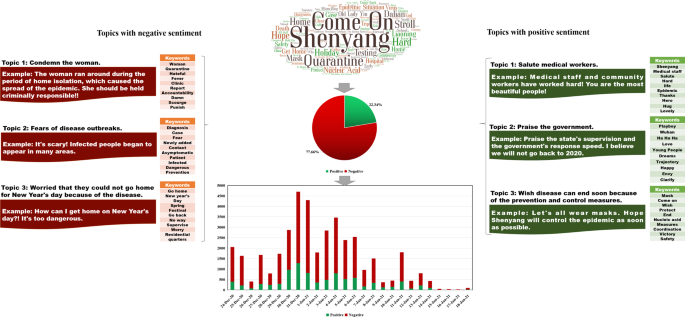

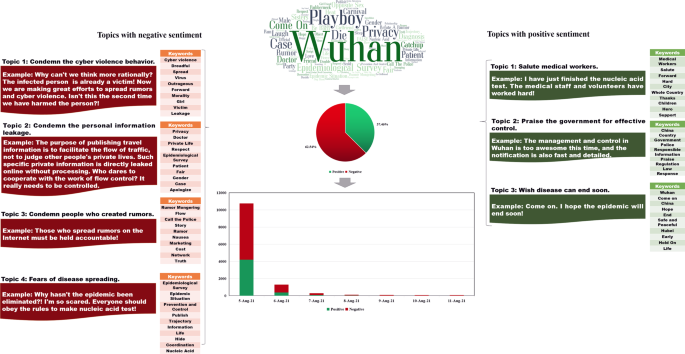

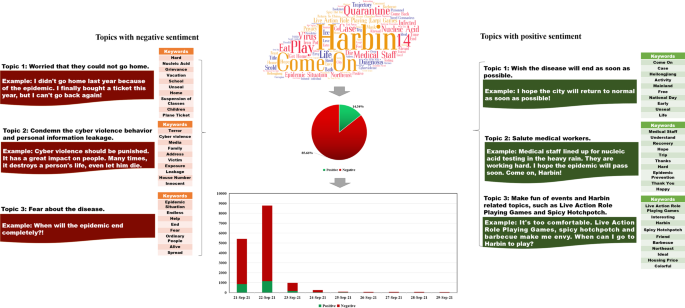

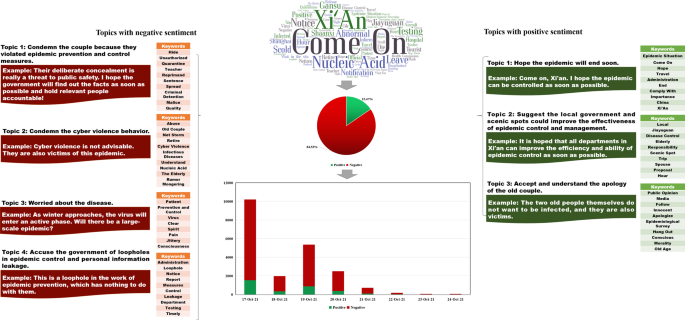

Cyber violence caused by the disclosure of route information during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Ying Lian 1 ,

- Yueting Zhou 1 ,

- Xueying Lian 2 &

- Xuefan Dong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2318-4805 2 , 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 417 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2260 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

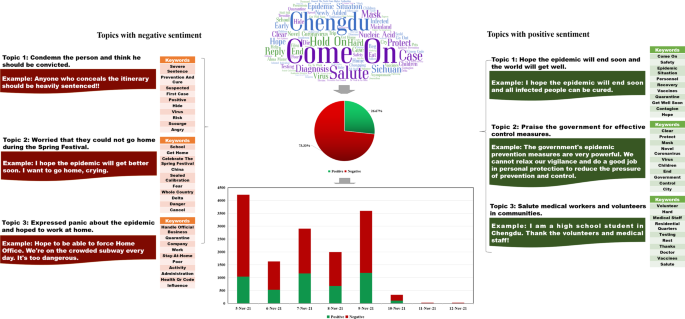

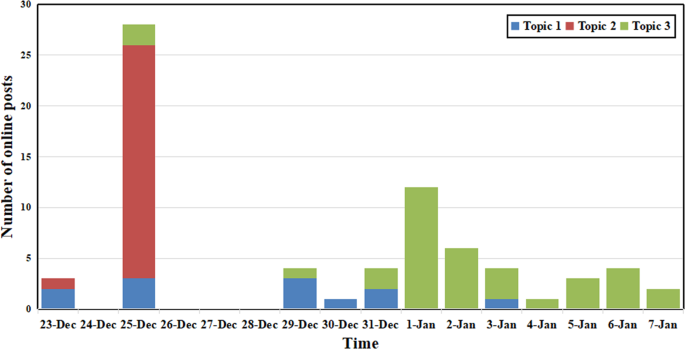

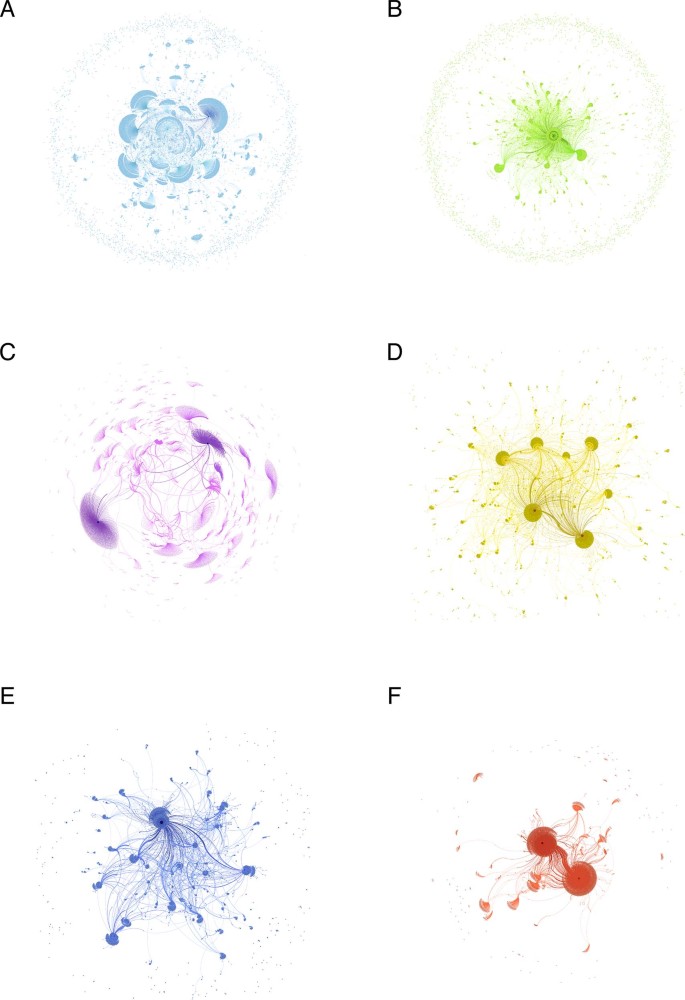

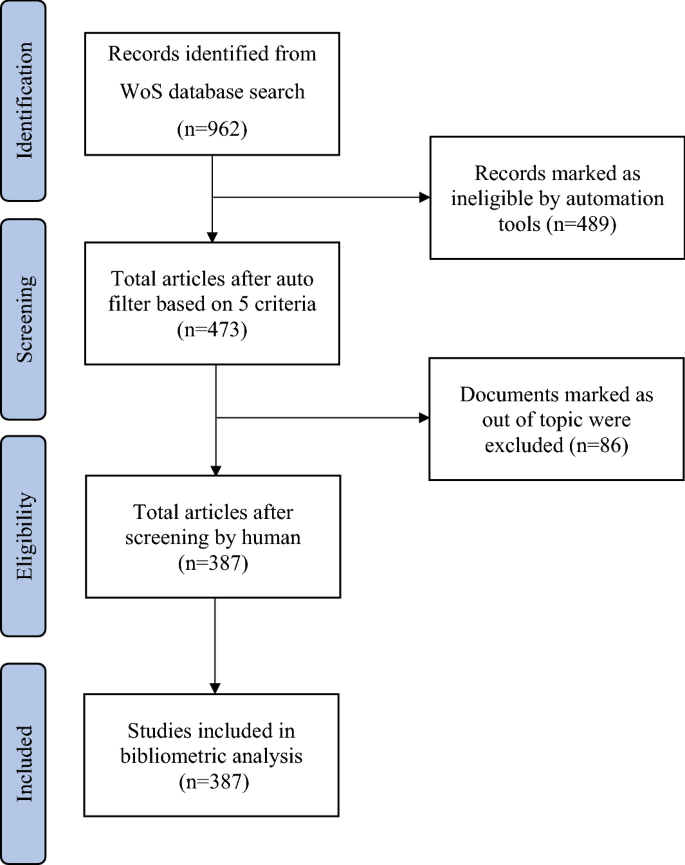

- Cultural and media studies

- Science, technology and society

- Social policy

Disclosure of patients’ travel route information by government departments has been an effective and indispensable pandemic prevention and control measure during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this measure may make patients susceptible to cyber violence (CV). We selected 13 real cases that occurred in China during the COVID-19 pandemic for analysis. We identified several characteristics that commonly appeared due to route information, such as rumors about and moral condemnation of patients, and determined that patients who are the first locally confirmed cases of a particular wave of the pandemic are more likely to be the victims of CV. We then analyzed and compared six real cases using data mining and network analysis approaches. We found that disclosing travel route information increases the risk of exposing patients to CV, especially those who violate infection prevention regulations. In terms of disseminating information, we found that mainstream media and influential we-media play an essential role. Based on the findings, we summarized the formation mechanism of route information disclosure-caused CV and proposed three practical suggestions—namely, promote the publicity of the media field with the help of mainstream media and influential we-media, optimize the route information collection and disclosure system, and ease public anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to focus on CV on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that our findings can help governments better carry out pandemic prevention and control measures on a global scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Early warnings of COVID-19 outbreaks across Europe from social media

Government disclosure in influencing people’s behaviors during a public health emergency

In.To. COVID-19 socio-epidemiological co-causality

Introduction, cyber violence (cv).

Although the Internet has provided numerous advantages to the world, such as a convenient communication channel, rapid knowledge sharing, and a transparent public engagement process, some disadvantages have emerged, of which CV is a representative example. Definitions of CV vary but generally refer to internet-related behaviors that espouse violence or use language in a calculated manner to inflame passions and eventually achieve mass emotional catharsis (Peterson and Densley, 2017 ). According to several investigations, the prevalence of CV has reached a considerable level worldwide (Barlett et al., 2012 ; Cava et al., 2020 ; Jones et al., 2013 ; Peskin et al., 2017 ), especially among youths like students (Saleem et al., 2021 ). A national telephone survey of about 4500 youths aged 10–17 in 2000, 2005, and 2010 in the US reported a significant increase in the rate of online harassment between 2000 and 2010 (Jones et al., 2013 ). The survey also found that girls are more likely to experience CV, especially cyber dating violence. According to Hinduja et al., 20% of a random sample of 4441 students aged between 10 and 18 years experienced CV (Hinduja et al., 2013 ). In general, CV is much easier to perpetrate than traditional (or offline) violence because its carrier, the Internet, transcends geographic and temporal boundaries (Cava et al., 2020 ). However, CV can also generate the same adverse effects on victims as traditional violence, including but not limited to fear and other distressing emotions (Casas et al., 2013 ; Peterson and Densley, 2017 ) and even suicidal behavior. For example, a famous Korean actress committed suicide in October 2008 because of CV (Chiyohara, 2010 ).

CV and social media