Minna Bank: Japan's first digital bank

Japan’s digital native consumers don't need a brick-and-mortar banking experience, so Minna Bank built a different bank for them—in the cloud.

Call for change

First came the digital natives. Then, the financial technology companies flexed their muscles. Next, we saw a variety of non-banking companies entering the banking field. With all of these rule changes and paradigm shifts affecting banking on a global level, Bank of Fukuoka, the core bank of the Fukuoka Financial Group (FFG), based in Kyushu, Japan, knew they needed to transform. “The number of customers visiting traditional branches of the FFG decreased by 40% over the past 10 years, while the number of customers using internet banking increased by 2.4 times over the same period,” said Koji Yokota, President, Minna Bank. To create a bank for everyone—including digital natives—FFG would have to change. But how?

FFG began by establishing iBank Marketing Corporation, a platform company to explore potential business models for the bank of the future by connecting the financial and non-financial sectors with local communities. Kenichi Nagayoshi, the founder of iBank Marketing and Director and Vice President of Minna Bank, explained:

"Our mission was to create innovative financial services, which is why we launched iBank Marketing to develop simple financial functions and digital marketing, with data and analytics at its core. Our core product app, Wallet+, has been downloaded more than 1.6 million times. We thought it was time to create a new platform for financial services now that the game is changing."

We chose Accenture as our partner largely because of their global digital expertise in technology, in design, and in data analytics. This, combined with their ability to execute, enabled us to launch our service on time, even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Accenture is an excellent company and our best partner.

Koji Yokota / President, Minna Bank

Minna Bank has won the "Brand of the Year" award in the brand category of the Red Dot Design Award 2021, one of the world's three major design awards. They are the first Japanese company to win this award, and the first financial institution in the world to win it. The company also won "Best of the Best" (the highest award of the year) in the Communication Design category (Applications) and "Red Dot" in the Communication Design category (Brand Design & Identity), winning three awards simultaneously.

When tech meets human ingenuity

Under these circumstances, FFG is implementing a "two-way approach" in digital transformation. While FFG, which has a traditional bank, is steadily implementing digital transformation, the approach is to establish Japan's first digital bank, Minna Bank, as an organization to implement digital transformation in a single step without the constraints of the existing business. This bank was the first bank in the world to build a full cloud banking system, and the system was built in the midst of a pandemic, with overwhelming speed.

Minna Bank was designed as a digital technology company that provides financial services to digital native customers. “We looked all over the world for a suitable platform for a digital bank, but there was no banking system built in the public cloud. So we decided to create a full cloud bank ourselves,“ said Nagayoshi.

Accenture is providing support in the adoption of Agile development and in multiple areas such as automation, strategy and talent development. Its Banking, Strategy & Consulting, Technology, and Interactive teams have come together from Fukuoka, Osaka, Tokyo, Aizu, Hokkaido and two overseas locations, transcending national and organizational boundaries to partner with Minna Bank.

In addition to its own resources, Accenture has drawn on its vast ecosystem of technology partners—in this case, industry leaders such as Google, Microsoft, AWS, Salesforce and Oracle—to take advantage of their solutions and best practices.

Specifically, in the "Zero Bank Core Solution" jointly developed by Minna Bank and Accenture, the core system will be implemented on Google Cloud using Accenture's Digital Experience and cloud-first approach, connected technology and cloud-native core solution. For contact center operations, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Amazon Connect and Salesforce's Service Cloud have been combined. Microsoft's Azure is being used for the virtual desktop infrastructure for employee and system operations, and Oracle Cloud is being used for the accounting system. Collaboration with these solution providers has allowed Minna Bank to build its foundation as a cloud-first business with the latest technology available worldwide.

In 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Minna Bank project team continued to press forward. It took no more than 18 months to invent and launch a transformational bank in a country with strict regulations governing financial institutions—an unprecedented achievement.

"If it wasn't for cloud, we would have been six months late in opening. Cloud's scalability, speed of deployment and efficiency in fixing bugs are the reasons for the agility of our banking services," said Yokota.

A valuable difference

Minna Bank differs from traditional banks not only by virtue of its operating model, but also its marketing and promotion. Instead of using mass media, it actively employs social media and develops promotions by observing mentions among users. This approach is made possible by a user interface and experience that perfectly matches the preferences of the bank’s target market. To target digital natives, Accenture's team of designers pursued a simple and appealing graphical presentation with minimal descriptive information.

The planning and design process started with a thorough understanding of the thinking and behavior of digital natives, and a commitment to develop services from the customer's perspective: when and how do they want to use financial services? This approach enabled Minna Bank to become a frictionless app that people want to use every day. It is also a portal for non-financial services, providing great value to customers by turning data-based marketing into a service. "We are the first bank in Japan to truly integrate financial and non-financial data into a single service," said Nagayoshi.

Minna Bank has three core business concepts:

- Give shape to everyone's voice—provide new financial services in line with changes in customer behavior.

- Deliver the best for everyone—become a comprehensive financial concierge based on an understanding of customers.

- Integrate into people's daily lives—realize the concept of a BaaS (Banking as a Service) business.

BaaS is a new banking system offering based on the Accenture Cloud Native Core Solution. It helps business partners to create new value in the banking industry.

Minna Bank, a unique digital entity, is a bank for the age of a data-driven society. It will continue to be a bank that explores the potential of hyper-personalization and makes customers say "Wow!”

"As Japan's first digital bank, Minna Bank will be the epicenter of innovation in the Japanese financial industry. Accenture is committed to continuing to be an engine of innovation for Minna Bank," said Masashi Nakano, Senior Managing Director, Financial Services, Accenture.

Japan's first digital bank

Launched the business in 18 months

of employees are engineers

As Japan's first digital bank, Minna Bank will be the epicenter of innovation in the Japanese financial industry. Accenture is committed to continuing to be an engine of innovation for Minna Bank

Masashi Nakano / Senior Managing Director, Financial Services, Accenture Japan Ltd

Built for change podcast

Listen to our award-winning podcast, Built for Change: Adweek Podcast of the Year Award Winner for Best Thought Leadership Podcast.

EPISODE 11: Preparing for the Society of the Future

A select group of companies recognize that emerging consumer and investor lifestyle shifts will have a tremendous impact on business in the future. Learn how these “forerunners” are charting a course to growth by prioritizing ethical usage of technology, environmental sustainability, human care and more.

Meet the team

Masashi Nakano Senior Managing Director – Financial Services, Accenture Japan Ltd

Koji Miyara Managing Director – Banking Lead, Financial Services, Accenture Japan Ltd

Kentaro Mori Managing Director – Strategy, Banking Lead, Accenture Strategy & Consulting, Accenture Japan Ltd

Keisuke Yamane Managing Director – Intelligent Software Engineering Services Co-Lead, Accenture Technology, Accenture Japan Ltd LinkedIn

Ryote Mochizuki Managing Director – Accenture Interactive, Accenture Japan Ltd

Related capabilities

- Cloud services

- Banking cloud services

- Accenture Google Business Group

These 3 financial services brands maximized the impact of their rebrand. You can too.

Patrick Heath

Rebranding a financial services company can be challenging for a number of reasons. Many of these companies have complex and decentralized organizational structures which can lead to questions about who’s responsible for the many details related to implementation. Dozens — if not hundreds, or thousands! — of regional, national, and even international branches fall under your brand umbrella. And the sheer volume of branded assets you’ll need to convert before you can consider your rebrand complete can be severely under-estimated.

All these factors (and many more) present large-scale challenges for you to overcome. This is true whether you’re rebranding due to an M&A, modernizing your visual identity, trying to appeal to digital-first consumers, or expanding your products and services.

So, if you’re banking on a rebrand to propel your organization forward, you’re probably feeling immense pressure to get it right. The good news is that there are valuable lessons you can glean from others who have already been down this road.

These three financial services institutions partnered with BrandActive to maximize the value of their rebrand. Take a page from their rebrand implementation roadmaps to help you position your company for a successful rebranding journey.

How two regional banks created a new powerhouse brand using thoughtful integration strategies

When two banks merged to form an even larger bank, two skilled marketing teams joined forces to launch a compelling new brand. The challenge? Each team came with its own culture, processes, and methodologies. And since the merger involved launching an entirely new name and identity to significantly increase market share, they realized they needed to reimagine their brand and marketing operations from the ground up.

To that end, the bank partnered with BrandActive to launch and execute a comprehensive rebranding implementation plan . We also helped their brand conversion teamwork through different processes and create a more cohesive marketing operation.

10 steps to brand implementation success

Here are 10 steps to take to ensure that your new brand is implemented into the marketplace correctly.

Creating order out of the nuances of a rebrand

Merging two teams together — even when they are talented and capable — can feel chaotic. To help our client navigate this transition, we:

- Conducted rationalization exercises . This involved auditing all existing materials from each legacy brand (e.g. brochures, product sheets, webpages, forms — you name it). From there, the team rationalized what should stay, what should go, and what should be reimagined from scratch so that two sets of materials became one unified portfolio.

- Created and optimized marketing processes. Each legacy team knew that the marketing processes they brought to the table would no longer suffice for a new brand with a broader reach. Therefore, we worked to document processes for things like kicking off a new creative project, following brand guidelines, and obtaining approvals (including those related to budgets and legal compliance).

- Worked with internal departments and external vendors to convert all legacy branded assets to the new brand. This included all of their collateral and helping implement the new brand onto key assets.

Working through each of these scenarios and projects together helped the legacy teams align with each other and solidify their new marketing culture and framework.

How one bank used a brand refresh to broaden brand identity and expression

If you’re refreshing or repositioning your brand, you may think you’re in for an easier time than a complete rebrand. But in reality, a brand refresh presents many of the same challenges — and requires similar resources and energy — as rebranding.

Most refreshes are across-the-board updates of a brand’s logo and visual identity. But when one North American bank decided to refresh their brand, they only changed certain elements of their logo and brand expression for specific business units and use cases. This nuanced approach led to unique challenges because they couldn’t use a one-size-fits-all branded and digital asset conversion strategy. Therefore, they engaged BrandActive to help them implement their refresh in just the necessary places and scenarios — and determine how much it would cost.

Even subtle brand refreshes require thoughtful budgeting, planning, and execution to achieve the impact you desire.

Through audits and workshops, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of every area the updated brand would impact. Then, we helped the client develop a realistic timeline and budget. Next, we developed a project structure for producing and updating collateral. This included creating all related processes and onboarding temporary freelance and agency partners to help them produce updated collateral quickly and cost-effectively. Finally, we kept all areas moving forward until the project was complete — no loose ends.

Bottom Line? Even subtle brand refreshes require thoughtful budgeting, planning, and execution to achieve the impact you desire.

Rolling out a logo-centric rebrand enabled this local credit union to emphasize its commitment to community and education

Gesa Credit Union , a member-owned institution, embarked on a rebrand to emphasize its ongoing commitment to education and community engagement. To accomplish this, they introduced a new logo and visual identity to better reflect their brand promise.

As an organization with small but mighty marketing team, Gesa engaged BrandActive to manage the end-to-end rebranding implementation process. As such, we owned the timeline, ensured vendors and agencies met their targets, and kept the entire project running smoothly.

This included:

- Helping Gesa choose and implement its rebrand launch strategy . In keeping with their values, Gesa made it a top priority to effectively engage employees as part of their launch.

- Managing the branded asset conversion process. Given Gesa’s community presence, it was incredibly important to the team — and the CMO — to introduce their new visual identity consistently across every branded asset. A large undertaking, we helped Gesa plan and account for every element and convert their assets on time and within budget.

- Managing their agency portfolio so launch and roll-out deadlines were met. We managed Gesa’s agency roster to ensure everyone was on target with their plans for launch and roll-out – and supported the launch of their new brand.

Your takeaway? Internal teams of all sizes need help implementing the details related to a rebrand. After all, most marketing teams are already stretched thin meeting the day-to-day demands of their fast-paced roles. An implementation partner can manage the details of implementing a rebrand so you don’t risk team burnout.

An experienced implementation partner can help you navigate the complexities of a financial services rebrand

Rebranding a financial services organization is a complex and time-consuming undertaking. It’s also expensive. With so much hinging on a successful outcome, you can’t afford to lose momentum and risk stalling out before reaching the finish line.

An experienced implementation partner can help you maximize the value of your rebrand investment and gain the dividends you expect. So if you’re ready to get started, just reach out . We’d love to help you launch your brand’s next chapter.

Related Insights

Planning for rebranding implementation

To optimize your brand for success, evaluate your marketing processes

How to jumpstart your stalled rebrand and take it across the finish line

Powering digital transformation through destination branding

Insight, Research & Analytics, Design Thinking, Innovation, Customer Journey Design, Destination Branding, UI/UX, Digital Asset Management

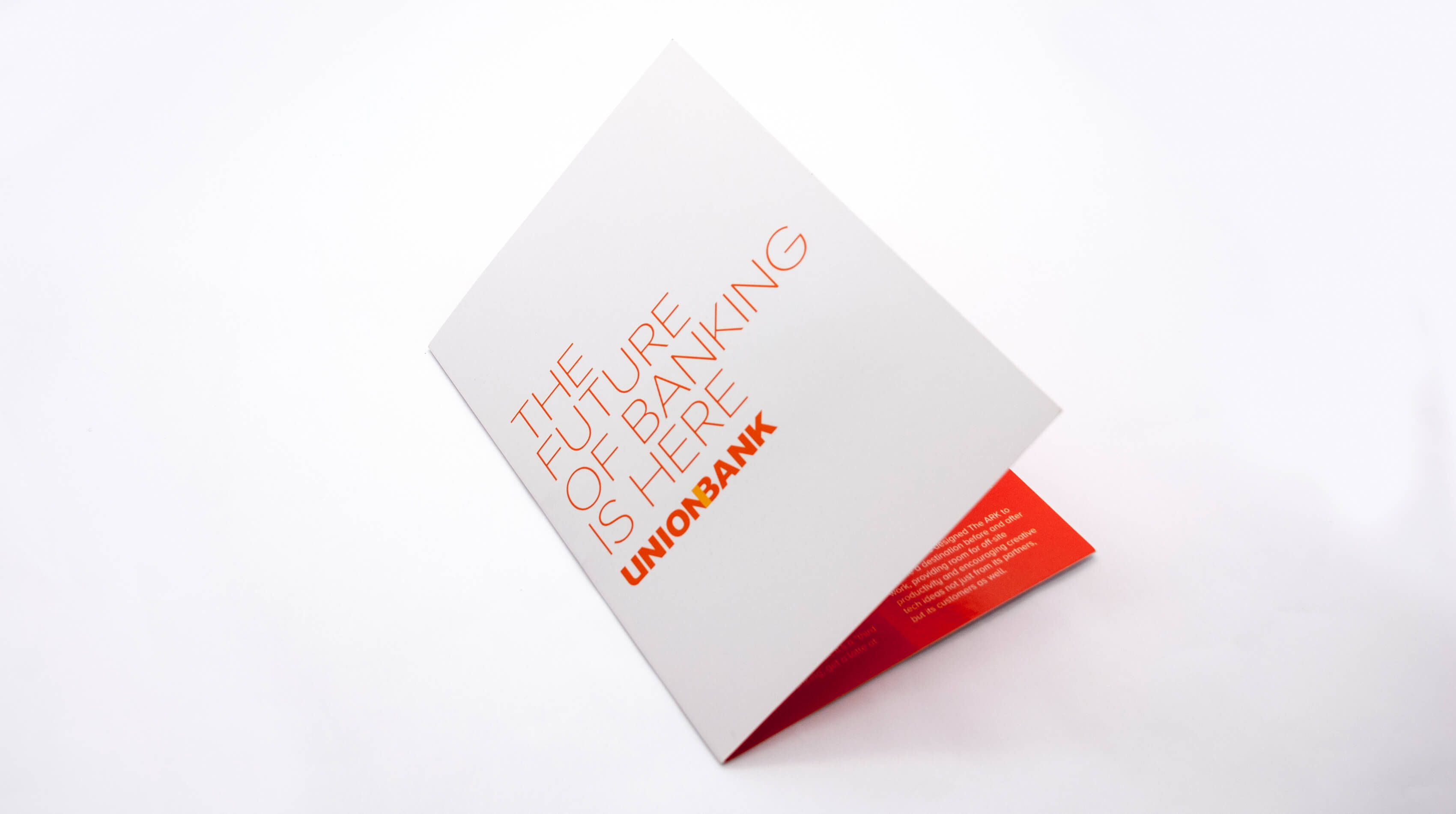

Established in 1918, UnionBank is one of the fastest-growing banks in the Philippines, ranking seventh in terms of assets under management.

With only 200 branches, UnionBank had a comparatively small retail footprint. But they saw an opportunity to complement that real estate with technology to advance the digital transformation agenda. Success in digitally infused customer experience would position them as the most innovative bank and respond to emerging shifts in retail banking.

The aim was to get millennials to the bank and to get the older demographics to bank digitally. Unionbank wanted to reassure the market that they were the right partners for the digital future. The idea was to shift the retail focus from service and transaction to relationships and sales. But most of all, Unionbank was keen on making banking more accessible through customer experience innovation, in line with the CEO’s ethos of “No one left behind”.

The Ark – an innovation lab on the high street. Bonsey Design was appointed to deliver the model for a next-generation banking destination. We started with a flagship centre in Manila known as The ARK. The concept was to design hi-tech, high-touch innovation lab to showcase UnionBank’s customer-centric innovation strategy.

Our research at the Design Thinking stage uncovered vital customer pain points.

The biggest challenge was the tedious queuing. And the frustration was amplified by having to line-up at multiple counters. The overall journey was inflexible and did not invite customers to engage beyond their transactional needs.

The Human Experience: We developed the Ark Ambassador Persona to reimagine the modern banker. The Ark Ambassadors are warm, well trained and always show up at the right time. The customer no longer needs to ricochet from one desk to the next.

The Physical Experience: We created an inviting environment in which customers would be relaxed and receptive. Space engages the visitors at a multi-sensory level. The modular design of the main banking floor allows new functionality like speaking events, cocktails and hackathons

The Digital Experience: A customer arriving at The ARK would simply need to pick up a tablet to conduct their banking transactions or explore new products. Intuitively responding to the customer’s needs, the ARK Ambassadors would facilitate the digital banking process.

For those customers unfamiliar with digital banking, we modelled the UI and UX to emulate social media and familiar digital touchpoints. We also developed specialised video, VR and AR content to facilitate customer education and enriched baking experiences.

Within six months, The ARK saw a six-fold increase in account openings, with an average 20% reduction in transaction times.

Sales for new products has increased, and the dependency on traditional banking processes has decreased. Customers now prefer self-service machines.

Over 70 different events were held here within the first year of operation, bringing together The Ark community.

We are now applying the model and its learnings across the remaining 195 bank branches. Bonsey Design is managing the roll-out with the client teams.

Our effort was further validated by the ARK winning numerous awards including:

– Most Innovative Digital Branch Project – The Asset Triple A Digital Awards 2018 (HongKong)

– Top 14 Most Stunning Bank Branch Designs in the World

– Retail Banker International: Winner of the Best Branch Customer Experience in the Asia Pacific (Singapore) 2018

– International Data Corporation (IDC) Philippines: Digital Transformer of the Year 2018

- brand & digital strategy

- brand naming

- brand identity

- project management

- in the news

- Case studies

- Our services

- News & views

- sustainability

FINANCIAL BRANDING CASE STUDIES | DIGITAL FINANCE CASE STUDIES

Explore our digital brand case studies with examples in financial services, with branding, rebranding and digital case studies across wealth management, private banking, retail banking, investment banking and fintech.

As a leading digital brand agency, our case studies span brand strategy, brand naming, rebranding and digital transformation, including branding for start-ups, repositioning heritage banks, brand identity design, and frictionless user experience design for online banking websites and apps.

Re-naming a global financial brand in 72 hours

brand + digital

Kelvin chia.

Rebranding - Legal pioneers across Asia

brand + digital + ip

The bank that helps you revive your finances

A digital bank built around customer needs

The new name in wealth management technology

My Indosuez

An app to manage your wealth

Branding a family office in Nigeria

Indosuez Wealth Management

A worldwide wealth management brand

Coronation Merchant Bank

A new force in African banking

Coronation Capital

Brand proposition for a private equity firm

Growing digital communities through payments

Branding a fintech information marketplace

A new name in technology investment banking

Tiera Capital

Naming a private equity investment product

Smart Transactions Group

Branding the UK’s leading smart payments group

Rothschild Global Financial Advisory

Redefining global investment banking

Rothschild Reserve

Harnessing the magic of Rothschild for consumers

Rothschild Wealth Management & Trust

Seven illustrious generations distilled

European Banking Authority

Advising a European Commission initiative

Standard Chartered

Usability research for B2B banking online

Global usability research for online banking

NatWest Markets

Branding a global investment bank

First Direct

A pioneering example of online banking

INTEGRATED BRAND EXPERIENCES FOR DIGITAL BANKS

Our brand and digital case studies illustrate examples of our work for retail banks, online banks, wealth managers, investment banks and fintechs, with examples in the UK, Europe, Nigeria and international financial institutions.

As a digital brand agency with deep experience in financial services we combine specialist brand and digital skillsets to create immersive brand experiences for financial brands across all media, including UX design of account opening processes, online banking services and banking apps.

We have worked with some of the world's leading banking software provider to design banking solutions, as well as fintech start-ups with their own technology.

Read more about our digital brand agency services .

This website uses cookies to provide you with the best user experience. By using our website, you consent to our use of cookies in accordance with our cookie policy .

Case Study 7: The Digital Transformation of Banking—An Industry Changing Beyond Recognition

- First Online: 06 February 2020

Cite this chapter

- Hubert Tardieu 6 ,

- David Daly 7 ,

- José Esteban-Lauzán 8 ,

- John Hall 9 &

- George Miller 10

Part of the book series: Future of Business and Finance ((FBF))

1900 Accesses

1 Citations

Partly as a result of the rise of FinTechs, banking is a sector that is facing significant disruption. In this case study, we identify some of the innovations that are being made both by young start-ups and long-established banks. We explore emerging opportunities in terms of business models, as well as how new operating models will boost customer-centricity and optimize costs through intelligent automation. The challenges of strategy, leadership, and attracting and retaining digital talent are analyzed. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of how platforms will enable new ecosystems of partners to work together to create and capture customer value.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Accenture. (2018). Beyond north Star gazing . https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/pdf-85/accenture-banking-beyond-north-star-gazing.pdf . Accessed October 26, 2019.

Bain. New bank strategies require new operating models . https://www.bain.com/contentassets/a97b9014afc84a76ae9fb723d3e94ead/bain_brief_new_bank_strategies_require_new_operating_models.pdf . Accessed October 26, 2019.

The Financial Brand. Is the banking industry prepared for a world without bankers ? https://thefinancialbrand.com/86253/banking-future-of-work-training-digital-trends/ . Accessed October 26, 2019.

Capgemini. (2017, October). The digital talent gap . https://www.capgemini.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/report_the-digital-talent-gap_final.pdf . Accessed October 26, 2019.

Efma. (2018, September). World retail banking report 2018 . https://www.efma.com/study/detail/28603 . Accessed October 26, 2019.

EY. (2018, June). How convergence in banking could be an opportunity for growth . https://consulting.ey.com/convergence-banking-opportunity-growth/ . Accessed October 26, 2019.

EY. (2016). Global consumer banking survey . https://eyfinancialservicesthoughtgallery.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ey-the-relevance-challenge-2016.pdf . Accessed October 26, 2019.

IDC. (2018, March). The business value of the stripe payments platform . https://stripe.com/files/payments/IDC_Business_Value_of_Stripe_Platform_Full%20Study.pdf

KPMG. (2019, July). The future of digital banking: Banking in 2030. https://home.kpmg/au/en/home/insights/2019/07/future-of-digital-banking-in-2030.html . Accessed October 26, 2019.

McKinsey. (2018, August). The lending revolution: How digital credit is changing banks from the inside . https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/the-lending-revolution-how-digital-credit-is-changing-banks-from-the-inside . Accessed October 26, 2019.

OnDeck. (2019). https://www.ondeck.com/home5-lendstart . Accessed October 26, 2019.

Quartz. (2019, August). Digital banks are racking up users, but will they ever make money ? https://qz.com/1679197/when-will-digital-banks-like-n26-and-revolut-start-making-money/ . Accessed october 26, 2019.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Paris, France

Hubert Tardieu

Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, UK

Madrid, Spain

José Esteban-Lauzán

Warrington, Cheshire, UK

West Wittering, West Sussex, UK

George Miller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hubert Tardieu .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Tardieu, H., Daly, D., Esteban-Lauzán, J., Hall, J., Miller, G. (2020). Case Study 7: The Digital Transformation of Banking—An Industry Changing Beyond Recognition. In: Deliberately Digital. Future of Business and Finance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37955-1_28

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37955-1_28

Published : 06 February 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-37954-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-37955-1

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Midas touch of branding: banks' brand value, intellectual capital and the optimization of the Interbrand methodology

Journal of Intellectual Capital

ISSN : 1469-1930

Article publication date: 15 February 2021

Issue publication date: 17 December 2021

The aim of this paper is to show how a bank's brand value is quantitatively assessed using the Interbrand methodology, taking into account the specifics of the banking market. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to review the ways in which brands contribute to the higher market value of banks by strengthening intellectual capital (IC), as reflected in increased levels of competitiveness and the reputation that the bank maintains in the minds of customers.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper applies the Interbrand methodology, which indicates that the assessment of brand value implies the determination of economic profit as the difference between the net operating profit after tax and the cost of capital. The brand profit is then calculated as the product of the economic profit and the index of the brand role. Brand value is obtained as the product of the brand's profit and the discount rate of the brand. In order to further test the results obtained through the application of the Interbrand methodology, linear regression was applied to the panel data in order to provide more efficient econometric estimates of the model parameters.

This research has shown that the Interbrand methodology's empirical foundations lie in the Montenegrin banking market, but also that, out of all of the analyzed parameters, the greatest significance is obtained from the profit of the brand, which influences the value of bank brands.

Research limitations/implications

This research is related to the service sector–in this case, financial services – meaning that it is necessary to adjust the calculation of the weighted average cost of capital. Although the banking sector is a very competitive market, a limitation exists in the fact that the research was conducted only in Montenegro. In other words, in order to achieve a more detailed analysis, this methodology should be applied to more countries, such as those within the Western Balkans, as they have a relatively similar level of development.

Practical implications

A main contribution of this paper is that the assessment of the banks' brand value could be useful to future investors. Therefore, the improvement of the financial sector–in this case, banks–as institutions that hold a dominant position in the financial market in Montenegro, is a particularly important issue. It is important to point out that the research conducted could serve as a means by which to bridge the gap between theory and practice, since the methodology of the consulting company Interbrand has been optimized and adjusted to the Montenegrin banking market.

Social implications

On considering the fact that most countries of the Western Balkans are at a similar level of development, the authors can conclude that, with the help of this adapted form of methodology, this research can be applied to assess banks' brand value in neighboring countries.

Originality/value

This paper serves as the basis for further research as the analysis of banking institutions that comprise both marketing and financial aspects, i.e. the application of the Interbrand methodology, was not conducted in Montenegro. Also, this paper overcomes the literal gap between theory and practice as there is little research thus far involving the application of the Interbrand methodology to the field of finance; especially in the field of banking. The authors point out the specifics of the banking sector as a key explanation for this. This is why it is necessary to make certain adjustments to the methodology. The research has positive implications for banks' internal and external stakeholders. The originality of this research is reflected in the fact that the Interbrand methodology has been optimized in order to assess the brand of banks, taking into account the specificity of the analyzed market. Brand is analyzed as a component of IC: another factor that exemplifies the value of this research.

- Intangible assets

- Intellectual capital

Melović, B. , Vukčević, M. and Dabić, M. (2021), "The Midas touch of branding: banks' brand value, intellectual capital and the optimization of the Interbrand methodology", Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 22 No. 7, pp. 92-120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-08-2020-0272

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Boban Melović, Milica Vukčević and Marina Dabić

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Due to the competitive nature of the market, company management teams strive to build strong brands in order to differentiate themselves, for which more detailed marketing research is necessary. Brand creation, as a segment of intangible assets, i.e. intellectual capital (IC), is important and thus requires special attention. Brand is a key factor in enabling the achievement of long-term competitive advantages for a company ( Ratnatunga and Ewing, 2009 ; Agus Harjoto and Salas, 2017 ; Bharadwaj et al. , 2020 ).

Building a competitive brand within a market, however, requires assessment in order to obtain a clear picture of how a well-built brand contributes to the positive business results of the company ( Möller, 2006 ; Otubanjo, 2018 ; Wang et al. , 2018 ). Brands also play on psychological aspects or symbolic structures in users' minds on the basis of which future expectations about their operation will be generated. This is difficult to measure and capture objectively ( Feiz and Moradi, 2019 ; Khamitov et al. , 2020 ). We can define brand value as the incremental utility or added value to the product by brand name ( Rubio, 2016 ). It should be noted that conducting research on a brand as an intangible asset is demanding, especially when it comes to assessing its value. This is because intangible assets increase in importance as, and for most brands, their value does not lie in tangible, material assets, but rather in intangible ones. This has been confirmed by Cravens and Guilding (2000) and Popovic et al. (2015) , who show that the brand, as an intangible asset, represents a major part of the total corporate value of successful companies. Thus, questions pertaining to the significance and assessment of such assets are becoming increasingly prevalent – another motivation for this research. The demanding element of assessing the value of a brand not only arises from its intangible nature, but the fact that it is also based on determining future trends and prospects for the development of a particular brand. The research questions are: Can the Interbrand methodology find an empirical basis for assessing the brand value of banks? and Which of the parameters of the Interbrand methodology have the greatest significance when it comes to the value of a bank ' s brand?

The objective of this paper is to quantitatively present the ways in which the value of a bank's brand can be measured by applying the Interbrand methodology, thus assisting clients in obtaining a clearer picture of a particular bank, while simultaneously helping management to create strategies that allow them to achieve a greater market share.

The Interbrand methodology is used by the British marketing agency of the same name – Interbrand. The method is based on the observation of the entire continuous flow of investment in the brand and the process of managing it as an intangible asset ( Interbrand methodology, 2019 ). This methodology is grounded in the understanding that the core value of a brand is its economic value, i.e. the net present value (discounted) of future profits made exclusively by the brand. This is the methodology that first complied with the monetary requirements of ISO 10668 in 2010 ( Janoskova and Krizanova, 2017 ). Unlike other methods of assessing brand value, the Interbrand methodology covers both financial and marketing elements of brand evaluation, providing clearer insights into the brand-bank relationship. This served as another motivation for the application of this methodology. Alongside the Interbrand methodology, there are other methods with which to assess brand value, such as Aaker's Brand Equity Ten, the Brand Finance Method, BAV (Brand Asset Valuator method), and more, depending on the approach chosen. These methods, however, do not emphasize both aspects of brand valuation observation. It is also difficult to apply them to large numbers of markets due to the specifics of financial reporting and unadjusted financial statements. This also applies to the market analyzed in this study. Another objective of this study was to show that the Interbrand methodology, in addition to its standard application for ranking the most valuable brands in the world in the fields of production, trade, services, technology and telecommunications, can be applied to the banking sector and financial services.

The complexity of the assessment process is also contributed to by the fact that the measurement of brand value is carried out in the service sector; in this case the financial service sector, which is one of the factors that makes this paper original. In particular, an assessment of the banks' brand value in the Montenegrin market was conducted using the Interbrand methodology. According to the Interbrand methodology, the brand valuation process is based on three steps. The first step is the determination of economic profit, the second step is the calculation of brand profit, and the third step is brand evaluation. An additional objective of this paper is to show that the Interbrand methodology can be applied to the banking sector and financial services sector alongside its standard application, in which it ranks the most valuable brands in the world in technology and telecommunications, manufacturing and trades or services. This research will show the ways in which banks can be ranked from a marketing perspective through the assessment of the brand value of banks using the Interbrand methodology.

There are not enough researchers involved the application of the Interbrand methodology in the field of finance; particularly in banking. The authors have concluded that the specifics of the banking sector are a key reason for this and that this is why it is necessary to make certain adjustments to the methodology. In Montenegro, the value of brand banks has not been assessed using any method, serving as a further motivation. Specifically, the authors sought to assess the brand value of banks doing business in Montenegro while testing the Interbrand methodology, which is used today as a reference point on a global level. The competitiveness of commercial banks–fifteen in Montenegro–is of great importance to this analysis. This is a large number when we consider the fact that Montenegro is a relatively small market. Competition between banks develops the need for managers to discover how loyal their customers are and, in this way, determine how much their bank, as a kind of brand, contributes to that loyalty.

This paper seeks to observe brand through the context of IC, adding further value to this study. This is because the brand represents a significant item of IC. The brand is associated with IC through its analysis as an element of IC. Therefore, the brand belongs to the relational component of IC ( Roos et al. , 2001 ; Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ). Hence, the brand and elements of brand identity have a significant impact on the strengthening of the IC of the company ( Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ). It is therefore not surprising that research on brand as an intangible asset–and thus an element of IC –is an increasingly prominent topic in modern business. This paper seeks to shed new light on IC in transition countries by outlining the assessment of its important relational component, thus offering clearer insights into complex methods for assessing IC as a whole. The banking sector is ideal when applying research on the development of IC because it is primarily based on knowledge, as demonstrated by Tran and Vo (2018) . In order to provide the best service to their clients, banks must invest in human resources, brands, systems and knowledge processes ( Tran and Vo, 2018 ). In addition to the work of the aforementioned authors, the importance of IC for competitive business has been confirmed by previous studies too ( El–Bannany, 2008 ; Goh, 2005 ; Mavridis, 2004 ; Muhammad and Ismail, 2009 ; Kamath, 2007 ). These researchers have analyzed IC using the example of financial institutions, i.e. banks. In accordance with previous research, we conducted an analysis of brand valuation as a component of IC in the Montenegrin banking market in order to see how much a bank, as a brand, contributes to successful business. This paper provides a summary of existing scholarship on the elements of IC; the adequate assessment of which strengthens the market position of banks in Montenegro and in other countries, as characterized by a high concentration of banks in the financial market. In this way, the importance and role of IC in creating additional corporate value in banks is further emphasized in an attempt to build sustainable strengths to further the bank's competitive position in the market. The paper consists of six parts. The introduction highlights the role and importance of the brand and its assessment when it comes to modern ways of conducting business. The second part provides a review of previous research in this area and outlines the specifics of the application of the Interbrand methodology in the field of financial services, i.e. in banks as financial institutions. The third part shows the Interbrand methodology and the results of the application. The discussion of the results is shown in the fourth section. The fifth part provides the conclusions and implications of the paper and the sixth part presents the limitations of the research and gives the authors' recommendations for future researchers.

2. Literature review

2.1 theoretical framework for intellectual capital assessment – brand relationships.

A number of previous researchers have pointed out that, decades ago, well-developed companies did not base their competitiveness on tangible assets, but on intangible ones, focusing on the development of IC as a type of intangible asset ( Teece, 1998 ; Loyarte et al. , 2018 ). IC is an important component of intangible assets and it can significantly contribute to the competitive advantage of a company and, thus, the growth of its market share ( Chen et al. , 2005 ; Mondal and Ghosh, 2012 ; Jurczak, 2008 ). This enhances and highlights the need to measure the performance of IC, which allows for comparisons to be drawn between other companies in the marketplace and facilitates the monitoring of developments and improvements over a certain period of observation ( Jurczak, 2008 ). There are three techniques with which to measure IC: balanced scorecard, intangible asset monitor and Scandia Value Scheme ( Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ). Unlike previous authors, Chan (2009) identifies five approaches for measuring IC: the Market Capitalization approach, the Direct IC Measurement approach, the Scorecard approach, the Economic Value-Added approach and the VAIC methodology. On the other hand, Fiano et al. (2020) , identifies four approaches to the valuation of IC: direct intellectual capital (DIC) methods, market capitalization methods (MCM), return on assets (ROA) methods and Scorecard methods (SC). Table 1 shows the most common methods used to measure and analyze IC and its components.

Based on this table, we can see that some of the methods used to measure the value of IC can be applied to brand valuation, such as the EVA method, the method based on the weighted average cost of capital and return on equity (ROE), which is not surprising given the fact that brand is a relational component of IC. The role and the importance of the brand can be observed through the lens of IC. IC includes knowledge, brand, patents, human capital, research and development. It is considered the main resource with which to generate economic growth and wealth ( Forte et al. , 2017 ). Moreover, investments in IC are important to companies that want to achieve increased productivity and efficiency and thus represent a key item with which to improve business processes ( Forte et al. , 2017 ). Intangible assets are a main source of wealth, prosperity, economic growth and innovation ( Loyarte et al. , 2018 ). The basic components of IC are: human, structural and relational (see Figure 1 ). The connection between the brand and IC can be observed. Brand and elements of brand identity represent important segments of IC. Therefore, the brand belongs to the relational component of IC in terms of reputation, strategic alliances, customers, licensing, agreements and distribution channels. All of these elements are interconnected and they form a whole that largely determines the competitiveness of companies operating in the market.

However, if we take into account that, in order to create a good and recognizable brand, it is necessary to have knowledge and skills; additional emphasis is placed on the connection between these two types of intangible assets. Specifically, the creation of a competitive brand implies adequate knowledge. This is even more important if we take into account the fact that contemporary knowledge is seen as the most important resource and factor by which companies differentiate themselves from others in the market ( Del Giudice and Maggioni, 2014 ). As shown in Figure 1 , knowledge is one of the essential elements of IC, as confirmed by the research of a number of scholars ( Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ; Goh, 2005 ; Taherparvar et al. , 2014 ). The role of knowledge, and thus the role of human capital, is particularly expressed in the service industry and especially in banks as financial institutions. The reason behind this is that service providers–in this case, bank employees and managers across all levels of the decision-making process–must have additional knowledge and skills in order to properly respond to the challenges of modern business. This was confirmed in a study on banks conducted in Portugal by Cabrita and Bontis (2008) , in which it was pointed out that human capital has a positive effect on the components of IC and, thus, on the brand as well. It can therefore be concluded that higher levels of knowledge and skills affect more competitive brands and that a recognizable brand strengthens IC as a whole ( Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ). This leads to the conclusion that investing in IC contributes to better company performance, which confirms the significant relationship between the performance of companies and IC, including its basic components ( Phusavat et al. , 2011 ; Salehi et al. , 2014 ). For further analysis of IC, and thus the brand as a relational component of this, it is important to understand the balancing of this type of intangible asset in financial statements. Therefore, Petty and Cuganesan (2005) demonstrate that the degree of presentation of IC in financial statements is still low, but this also depends on the size of the company and the branch to which the company belongs.

2.1.1 Theoretical framework for brand value assessment

Brand is one of the most important elements of IC. It is therefore not surprising that brand and brand valuation are increasing in importance, given the fact that IC is now recognized as an important element when strengthening the competitiveness of companies in the market ( Chen et al. , 2005 ; Seetharaman et al. , 2004 ). However, researching a brand is challenging, especially when it comes to assessing its value. The complexity of quantifying intangible assets does not arise only from their non-monetary nature, but also with regards to future flows and perspectives of the development of a certain brand. The extent to which the value of the brand and, therefore, its assessment, is important in modern business when improving business performance, which is demonstrated by this research and outlined in Table 2 .

As shown in the table, we can conclude that, in addition to the Interbrand methodology, other methods can be used to assess the value of the company brand, such as: Forbes, Brand Finance, Millward Brown and the Damodaran method, by using statistical methods to depict the relationship or influence of brand value on the financial and market performance of companies. Unlike the aforementioned methods, which are difficult to apply to some markets (as is the case in our research) due to specific financial reporting and the fact that financial and marketing aspects of brand valuation are not included, the Interbrand methodology can be applied. This is important both from a marketing and financial standpoint; especially considering the specificity of the banking market.

Additionally, it is the brand, as an intangible asset, which appears to be key to strategies differentiating and establishing relationships with consumers because, on the one hand, this is a means of distinguishing the company from competitors and, on the other hand, this is the basis of trust and close relationships with consumers ( Ball et al. , 2004 ; Čavalić, 2013 ).

However, it is very difficult to identify a brand and present it in financial statements ( Nimtrakoon, 2015 ). International Valuation Standards Council, ( International Valuation Standards Council IVS, 2010 ), enforce a precise hierarchy in the valuation criteria: market and income methodology. The most recognized business consulting agencies follow this hierarchy. Thus, the need to determine the value of the brand is an important factor when creating and preserving the overall value of the company, alongside the need to establish a better methodology for evaluating the company as a whole ( Rubio et al. , 2016 ). At the end of the 1980s, the brand was classified as an intangible asset in financial statements. This problem is recognized in the context of the need to evaluate the brand as a category that plays a major role in creating the overall value of the company ( Cottan-Nir, 2019 ).

Based on previous research, it has been acknowledged that, in marketing theory, the basic methodologies for brand evaluation can be classified into one of two basic groups. These authors point out that the first group consists of methodologies for determining brand value based on research results on consumer behavior and attitudes, and methodologies based on financial results or the financial performance of the brand which, in a classical sense, equates with the brand's financial value. The second group of methodologies relates to the tendency to assess the (financial) value of a brand as an intangible asset ( Damodaran, 2012 ).

There are four approaches to brand valuation: cost, market, production and formulary ( Cravens and Guilding, 1999 ; Seetharaman et al. , 2001 ). All of these approaches contain methods by which brand value can be assessed. However, as these are comprised of multiple evaluation criteria, the formal approach and the Interbrand methodology belonging to this approach are of particular interest. The formal approach is suitable for internal managerial evaluation purposes, but also when reporting to external users ( Brlečić, Valčić and Hodžić, 2016 ). These authors also point out that the methodology of this approach focuses on profitability determination.

The brand evaluation methodology, Interbrand, was the first to meet the international standard for monetary requirements, see ISO 10668 in 2010 ( Duguleana and Duguleana, 2014 ). This methodology is becoming increasingly important as it is based on observing the continuous flow of investment in the brand and its management of intangible assets ( Krstić and Popović, 2011 ).

The Interbrand methodology assumes that the greatest value of a brand is its economic value, representing the net present value of discounted profits, which are obtained exclusively from the brand, and it complicates the process of implementing this methodology. That is, according to the Interbrand methodology, determining the value of the brand involves three phases in which economic profit is determined first, then the profit from the brand and, finally, the value of the brand ( Krstić and Popović, 2011 ).

The methodology applied when ranking of the most valuable brands by the consulting company Interbrand combines marketing, financial and legal aspects in determining the value of the brand ( Veljković and Đorđević, 2010 ). These authors point out that brand value is calculated via the net present value of the future benefits of possessing a brand. It is crucial to determine the earnings of the brand and cash flow by applying the discount factor to reduce the value of the present net. In order to make the final calculation, it is necessary to determine which part of the company's revenue is of merit to a specific brand. Risk is assessed through brand strength assessment. This is a precondition for determining the discount factor, on the basis of which the final calculation is performed.

Although there are a number of methods for assessing the brand value, the success of any method depends on the company's ability to use that measure to improve financial performance ( Pakseresht and Mark-Herbert, 2016 ).

The application of different methods in measuring brand value is a way to differentiate between companies ( Duguleana and Duguleana, 2014 ; He and Calder, 2020 ). Such is the case in the banking market as well. Strong competition in this market increasingly emphasizes the role and importance of a bank's corporate identity. At first, the brand identity is created in order to enable the recognition of banks and establish how corporate identity is an essential component of market competitiveness. Therefore, modern and current trends in the banking industry are reflected in the corporate identity of the banks ( Trent and Mohr, 2017 ). This is the reason why the assessment of banks' brand value is a topic of contemporary relevance. However, it takes time in order to create a recognizable brand and to follow stages in the brand creation process. This has been confirmed by Milić (2014) , who showed that modern literature and economic practices show that the brand is created through long-term, persistent, patient and dedicated work.

2.2 Optimization of the Interbrand methodology for assessing banks' brand value

As mentioned above, this research is based on the application of the Interbrand methodology when assessing bank's brand value. Therefore, the specifics that characterize the application of this methodology in the banking market will be presented below.

The sample of this survey consisted of all of the banks operating in Montenegro, with the number of banks varying depending on the year in which the survey was conducted. The Interbrand methodology was applied for a period of three business years, i.e. 2014, 2015 and 2016. In the first observed year (2014), 12 banks operated in Montenegro, whereas in the second observed year (2015), 14 banks operated, and in the third (2016), 15 banks operated. The reason why this period was taken for analysis is that, at the time of conducting research with the Central Bank of Montenegro, there were no complete financial statements with the reports of the official auditor from which the data necessary for the research could be collected and which was in reference to 2017. Therefore, the Central Bank of Montenegro is regarded as the most reliable source of information with regards to the balance sheets and audit reports necessary for the implementation of the Interbrand methodology.

According to the Interbrand methodology (2019) , brand value assessment involves determining economic profit first, then profit from the brand and finally the value of the brand, which is described below.

2.2.1 Calculation of economic profit by adjusting the Interbrand methodology to the banking sector

wd–the share of debt in the desired capital structure;

kd–debt price;

wp–share of preferred shares in the desired capital structure;

kp–price of the capital from the issue of preferred shares;

we–the share of equity in the desired capital structure;

ke–cost of equity;

T - income tax rate.

However, due to the specifics of the banking market in Montenegro and the lack of availability of information on market indicators, as well as the fact that most banks do not pay dividends, which was confirmed based on the reports of the Montenegro Stock Exchange (2019) , in order to implement the Interbrand methodology, the weighted average cost of capital should be adjusted to the available data of the analyzed market.

we–the share of equity in liabilities;

kd–price of borrowed capital;

wd–share of borrowed capital in liabilities;

p - income tax rate.

In accordance with the example of the WACC budget in practice ( Telekom Srbija, 2016 ) the authors decided to adapt the Interbrand methodology. This method of calculating the weighted average cost of capital involves the analysis of the liabilities of the balance sheets of banks from the perspective of financial structure, all with the aim of calculating the share of equity and borrowed capital. The cost of equity is calculated as a ROE, which is calculated according to the following formula: Return on equity = Net profit Share capital × 100

For each bank, the value of the net profit is divided by the value of the share capital and this is taken individually from the balance sheet and income statement. The ROE rate should be multiplied by the share of equity in the liabilities of the balance sheet. This share is obtained when the value of equity is divided by the total value of liabilities.

The price of the borrowed capital is then determined. The interest rate on time deposits deposited for more than one year was taken as the price of borrowed capital ( Bikker and Gerritsen, 2018 ). This interest rate is taken from the audit reports for each year and for each bank individually. The price of borrowed capital is multiplied by the share of borrowed capital in the bank's liabilities and by (1-p), where p is profit tax rate, which amounts to 9% in Montenegro ( Chamber of Economy, 2020 ). Finally, the product of the cost of equity and the share of equity in the bank's liabilities is increased by the product of the price of borrowed capital, the share of borrowed capital in the liabilities of the bank and (1-p). In this way, an average weighted cost of capital was obtained for each bank for the observed time period. The calculated weighted average cost of capital is multiplied by the total capital and thus the cost of capital is obtained. The obtained cost of capital is deducted from the operating profit and so the first step in estimating the value of the brand is completed, i.e. the value of the economic profit of each bank is obtained.

2.2.2 Calculating the budget profit from the brand by adapting the Interbrand methodology to the banking sector

Profit from the brand is considered to be a product of economic profit and brand role index. Economic profit, which strives to measure the true profitability of the business ( Osinski et al. , 2017 ), is explained in the previous section, whereas the brand role index is calculated with the help of parameters. It is worth noting that each parameter carries a corresponding weight. Every parameter should establish scales in order to distribute the points corresponding to the weight–as objectively as possible–that these parameters have as a whole.

According to Jia and Zhang and Interbrand methodology, ( Jia and Zhang, 2013 ), the following is necessary for this research: market (10%), stability (15%), leadership (25%), trend (10%), support (10%), internationalization (25%) and protection (5%). These parameters for the calculation of the brand role index are also indicated by Vasileva (2016) . However, due to the specifics of the banking market, the parameters were adjusted to fit with financial services, i.e. banks as financial institutions, so that the Interbrand methodology could be applied.

The market parameters should show whether or not the market is stable, growing and whether there are strong barriers to entering the banking market. In this study, parameters with a weight of 10% were identified through the annual reports of the Central Bank of Montenegro. In the observed business years, according to the reports of the Central Bank of Montenegro (2019) , the banking market was stable, with a tendency to expand. This was supported by the fact that the banking market in Montenegro in the first observed business year expanded by one bank, in the second by two banks and in the third by one new bank. With regards to barriers to entry, all newly opened banks met the conditions prescribed by the rules and laws. Taking into account all of the above, according to this parameter, each bank could obtain a maximum of 10 points.

Parameter stability with weight (15%) suggests that new brands may not have the same significance to customers as brands with a long history, especially with regards to financial services, where two of the advantages that banks capitalize on are security and trust. According to van Esterik-Plasmeijer and van Raaij (2017) , trust is a very important determinant for the banking sector, which confirms the aforementioned claims. Thus, banks with a long history are better positioned in this aspect in the mind of the client and are trusted more than newly opened banks. This parameter is determined based on the years of operation of each bank. The years of establishment of each bank at the Montenegrin market are taken from the official website of each bank and the number of points is awarded accordingly. Depending on the number of years of operation of each bank, according to this criterion, banks could get three, six, nine, twelve, or fifteen points. Therefore, banks with the longest tradition received fifteen points and banks with the shortest period of operation received three points. The values in between were assigned in accordance with the years of operation of the bank according to the formed scale. If the bank did not operate at the market in a certain year, it was awarded zero points.

The leadership parameter (25%) is observed through the sum of assets. A larger amount of assets suggests an increased competitiveness of the bank, which is reflected in the larger number of loans that make up the most important item in the bank's portfolio, which attracts more clients. The bank with the largest amount of assets had a maximum of twenty-five points, whereas the bank with the smallest amount of assets was awarded five points. Points between five and twenty-five were awarded according to the scale formed.

The trend parameter (10%) is viewed from two perspectives, namely from the perspective of the bank's orientation toward new markets (5%) and new clients (5%). Data on whether a bank was oriented toward new clients were obtained on the basis of the mission and vision of each bank individually, as confirmed by an interview with each bank's management team. Therefore, if the bank was oriented toward new clients, it was awarded 5 points. If only existing clients were in focus, 0 points were awarded. The orientation of banks to new markets was observed based on the number of open branch offices in the territory of Montenegro. In other words, the number of branches and subsidiaries of each bank was compared first in relation to the previous business year, in the second year in relation to the first and in the third in relation to the second business year. If there was an increase in the number of branches and subsidiaries, the bank was awarded 5 points, if the number remained the same compared to the previous year it was given 2.5 points, and if there was a decrease in the number of branches compared to the previous year then 0 points were awarded, which told us that the bank was not oriented toward new markets. By adding the awarded points, the value of the trend parameter was obtained for each bank individually for all three years covered by this research.

The support parameter should show how much support the brand had in terms of investing in marketing or activities, such as sponsorship and social responsibility, which greatly contributes to brand recognition in the market and indirectly triggers positive associations in the client's mind. Based on the audit reports, which present a detailed analysis of the bank's operations, the item marketing costs were shown and points were awarded for each bank. The bank with the highest marketing cost was awarded ten points for the weight for this parameter, while the bank with the lowest marketing cost was awarded two points, according to the pre-formed scale. The number of points–between two and ten points–were awarded in accordance with the formed intervals and scales.

Internationalization with a weight of 25% indicates the spread of the brand beyond the borders of the country of origin. This parameter is determined by the number of countries in whose markets these banks do business. Data for this parameter were obtained from the official websites of the banks covered by the survey. Each bank had information on their websites on the number of countries in which they do business, and this was confirmed in an interview with the banks' employees. The more countries in which the banks operate, the higher the number of points awarded to them, in accordance with pre-formed scale and intervals. The bank that operated in most countries was awarded 25 points, whereas if a bank operated in only one country, it was awarded 5 points.

The last parameter, protection, with a weight of 5%, shows the company's ability to protect its brand. Whether a bank has protected its brand or, in this case, its logo, was determined with the help of the Intellectual Property Office of Montenegro (2019) and WIPO Madrid Monitor (2019) . Based on the website of the Intellectual Property Office of Montenegro and the “trademark search” option, we established which banks in the Montenegrin market had a protected logo. Based on interviews with the authorities in this area at the Intellectual Property Office of Montenegro, it was confirmed that only a trademark can be protected in Montenegro which, in this case, is the bank's logo. As there are banks in the market that operate under the auspices of a certain group, we determined the degree of protection of their logos on the basis of the WIPO Madrid Monitor website. Banks with a protected logo were given a maximum of 5 points, and banks that did not have a protected logo were given 0 points.

After determining the parameters for each bank individually, the values assigned to each parameter were summarized and this is how the brand role index was obtained. The higher the brand role index, the better the bank, because the profit from the brand would be higher, which will be reflected upon later in the estimated value of the brand.

2.2.3 Calculation of the brand value of the bank by the Interbrand methodology

As the third step, on the end, the brand's value is considered to be a product of the brand's profit and the discount rate of the brand's strength. The discount rate of a brand's strength is calculated by the brand with the highest strength being discounted at a rate without a risk – a risk free rate–because risk is assessed through brand strength assessment ( Veljkovic and Djordjevic, 2010 ), while the average power brand is discounted with the weighted average cost of capital for a given branch.

Due to the specifics of the market, the obtained value of brand profit is discounted with the average weighted cost of capital at a branch level, which was obtained for each year individually, from the previously calculated weighted prices of capital for each bank and an average was found. The discount rate obtained is multiplied by the profit from the brand and the brand value of the banks is found. However, this paper also postulates what would happen if brand profits were discounted at a risk free rate. The risk free rate can be determined on the basis of the capital asset pricing (CAPM) model; however, due to the lack of data for the calculation of the ß coefficient in the Montenegrin banking market, this is calculated with the help of auctions of treasury bills. Also, this method calculated a risk free rate through the Damodaran (2019) , which does not have this data, and so we could not deduce a date for Montenegro. As the Central Bank of Montenegro does not have an issuance function, the risk free rate is calculated based on auctions of treasury bills ( Treasury bills auctions, 2019 ), which is acceptable. In other words, only auctions related to one hundred and eighty two day bills were observed, then the average price at each auction at which treasury bills were sold during the observed year was observed, and after that an average was found. The value obtained is multiplied by the brand profit and thus the brand value of the banks is calculated.

This shows the specifics of the application of the Interbrand methodology in the banking market, especially in Montenegro. However, despite these specifics, it is possible to apply this methodology, which adds value to this work, while meeting one of the research objectives related to the fact that the Interbrand methodology, in addition to its standard use in technology and telecommunications, manufacturing, trade and classic service, can also be applied to the banking sector.

2.3 Conceptual model and research issues

Can the Interbrand methodology find an empirical basis for assessing the brand value of banks?

Which of the parameters of the Interbrand methodology have the greatest significance when it comes to the value of the bank's brand?

Conceptual model of the research is shown in Figure 2 .

3. Methodology

Although other methods, such as Forbes, Brand Finance, Millward Brown and the Damodaran methodology ( Janoskova and Krizanova, 2017 ; Fernandez, 2001 ), can be used to assess brand value, in order to determine the banks' brand value, the Interbrand methodology was applied. This was adjusted in accordance with the specifics of banks as financial institutions. Brand evaluation methodology was conducted in three steps: the first step determined the economic profit as the difference between operating profit and the cost of capital. The cost of capital was obtained by multiplying the total capital with the weighted average cost of capital. Due to the specific application of this methodology in the banking sector, the items for calculating the weighted average cost of capital were adjusted to the banking market, in accordance with practice, in an attempt to apply the Interbrand methodology. The authors identify that the second step involves the calculation of brand profit as a product of economic profit and the brand role index. The brand role index was based on the determination of the values of parameters adjusted to the banking market, as previously explained. The third step was related to the calculation of the brand value, which was obtained by discounting the profit from the brand with the weighted average cost of capital at a branch level and with the risk free rate. The weighted average cost of capital at a branch level was obtained when an average of the previously calculated weighted cost of capital for each bank was found. The risk free rate was calculated based on government bond auctions, as described above. For each bank individually in the observed business year, an assessment of brand value was performed. Although the aforementioned methodology could be implemented in one year, the authors believed that a period of three years offered more reliable, timely data necessary for the most objective research, creating a clearer depiction of the process. In this way, we were able to see how the bank's ranking changed according to its estimated brand value in the observed time period and whether there was a trend of growth or decline in the banks' brand value.

If we consider that the brand belongs to IC, and that the quality of services provided to customers is determined by IC ( Goh, 2005 ), it is not surprising that brand evaluation is a particularly important topic in contemporary business. Therefore, in order to determine the banks' brand value, this methodology was applied in the banking sector, bridging the gap between theory and practice. In other words, according to the authors, this is the first application of the Interbrand methodology in the banking sector, which is an additional contribution of this paper.

First, secondary data were collected from the official reports of banks (balance sheet and income statement) on the website of the Central Bank of Montenegro (Central bank, 2017) as well as on the banks' websites. Data from official sites refer to the parameters necessary to calculate the brand role index. In particular, for the stability parameter, which indicates that brands with a long history are not given the same treatment as new brands, it is necessary to know the years of operation of banks in the market and when they were established. As far as the parameter of internationalization is concerned, it is important to know whether the bank operates outside the borders of its country of business, which is shown on the official websites of each bank. The parameter of internationalization is especially important because the process of brand assessment itself becomes more complex when the international dimension is added. The support parameter requires audit reports for each bank individually for each year, because these reports contain clearly separated data on the funds that banks invest in marketing and other related activities. The protection parameter requires data from the website of the Intellectual Property Office of Montenegro and WIPO Madrid Monitor. For other parameters, data were gathered either from income statements or through communication with each bank's management.

The collected data are processed and prepared for end use.

Application of the Interbrand methodology.

By applying the Interbrand methodology across all three years, we are able to establish whether there has been a significant switch in the value of the banks' brand during the observed period. Below is a graphical representation of the results obtained.

Finally, there is a discussion of the obtained results, with conclusions made based on the research results.

4. Research results

This section presents the results of the research, obtained by applying the Interbrand methodology to the banking market. All of the data on which this research is based is available on request. Also, it should be noted that, due to the specifics of the area within which this methodology is applied, the Interbrand methodology had to be adjusted to the Montenegrin market conditions in some segments in order to implement it. In this way, an optimized Interbrand methodology was obtained. This was in accordance with practice and was confirmed by Jia and Zhang (2013) , indicating that, in this way, a more comprehensive analysis was achieved by applying an optimized model.

The banks' brand values used by the Interbrand methodology are shown in the following tables.

The brand values in Table 3 are shown in the graph below ( Figure 3 ).

Based on the given table and graph, we can see that the highest brand value is held by Bank 3, Bank 8, Bank 1 and Bank 2, which is expected if we take into account the performances of these banks, as well as the brand role index, which is highest in these banks respectively. The idea that brand value is related to the business performance of banks was confirmed through a study by Mavridis (2004) , which indicated that banks perform best in IC and, thus, in branding as brand is a relational element of IC. As can be seen, the discount rate of brand strength, i.e. the weighted average cost of capital at a branch level in the first observed business year, was 0.049, while the risk free rate, obtained on the basis of the auctions of treasury bills, was 0.013.