Civic Issues Blog

Just another Sites At Penn State site

Persuasive Essay on Decriminalization: Rough Draft

Everybody who has grown up in the United States in the past 40 years has heard the same spiel from their adults: all drugs are bad and addictive; never use them for any reason. At the time, kids listen and grow up with this in mind, and never really question what they hear. However, the issue is actually far more complex than the anti-drug programs make it out to be. The government’s “war on drugs” starting in the 1970’s has made it its goal to reduce the illegal drug trade, and this has included all types of drugs from heroin to marijuana. However, for marijuana specifically, the government’s classification and treatment of it has not only failed to achieve its original goal, but has also led to many unintended consequences that prove why the laws surrounding it are harsh. Despite marijuana’s growing popularity for its medicinal benefits, the government’s archaic treatment of it have led to many more consequences than benefits for communities across the United States. Current marijuana laws should be revised to make marijuana decriminalized because the laws have not only failed to reduce drug use, but have also disproportionately imprisoned minorities.

To start, the War on Drugs incorrectly classified marijuana, and the subsequent enforcement of these laws have not been successful in their original goals. As a response to increasing drug use in the 1970’s, Richard Nixon passed the Controlled Substances Act, which classified drugs based on their medical application and potential for abuse. Schedule 1 drugs were considered the most dangerous, posing a high risk for addiction with little evidence of medical benefits. This list includes heroin, LSD, ecstasy, and marijuana, despite its well documented medical benefits. Thus, when producing drug law legislation, the government treated marijuana with the same severity as heroin, already highlighting the ridiculousness of drug laws. The War on Drugs also included increased federal funding for drug control agencies and proposed strict measures (such as mandatory prison sentences) for drug crimes. Although there is disparity between state and federal laws, the federal law still mandates a sentence of 6-12 months for over 1 kg of marijuana, a 5 year minimum for cultivation of 100 kgs, and a 10 year minimum for over 1000 kgs (safeaccess). Mandatory minimum sentences require jail time after your second possession for any amount of marijuana, and sale of marijuana also warrants jail time (norml) Thus, although these laws differ from state to state, it is not difficult for a marijuana user to find themselves imprisoned (even if only for 15 days). Although this may seem harsh, if it has been successful, then what’s wrong with the laws? According to a Gallup poll, the amount of people who have said they have tried marijuana at some point in their lives has gone up from 4% in 1969 to 38% in 2013. Since the implementation of stricter drug regulations in the 1970’s, the amount of marijuana users has drastically increased, meaning that the illegal trade of drugs has not decreased and the laws in place have not been successful in reducing illegal use. Therefore, marijuana laws, which are too harsh in the first place, have not been successful in their intended purpose, a strong reason for why they should not continue to be in place.

Furthermore, not only are those laws overly harsh and inoperative, but they are also exceedingly expensive for the American public. There are two aspects of these laws that are expensive to the American public: paying the law enforcement who enforce the laws on a day-to-day basis, and paying for the housing/care of those imprisoned for marijuana offenses. According to a study by the ACLU in 2013, over the next 6 years, states will spend $20 billion enforcing marijuana laws; specifically, states pay $750 per marijuana-related arrest, and $95 is the national average per-diem cost of housing an inmate arrested due to a marijuana-related offense (CNBC). Many of the monetary costs are incurred in apprehending and processing offenders, which is a time-consuming and expensive process, especially for non-violent offenders. The enforcement of these laws is also expensive in terms of time spent by the officers enforcing the laws. For example, it was estimated that the NYPD spent 1 million hours enforcing low-level marijuana offenses between 2002 and 2012 (CNBC). Considering that most of these offenders are non-violent and utilizing a much less harmful drug than it is characterized, these numbers start to add up and the worth of these laws comes into question.

Furthermore, the enforcement of these marijuana laws is not consistent and is racially biased against African-Americans, despite their rate of use being similar to whites. Looking at figure 2 below, for both whites and blacks between the ages of 18-25 years old, marijuana use has been similar for both groups, with whites actually edging out blacks every year in usage rates (ACLU). Despite these similar usage rates, arrests for marijuana have shown that blacks are 4 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession, while in some states this number approaches 7-8 times as likely (ACLU). The reasoning behind these astonishing numbers is most likely an economic motive by the law enforcement agencies. Federal programs like the Edward Byrne Justice Assistance Grant Program include number of arrests in their criteria for distributing funds to local law enforcement. In order to increase their arrest statistics, law enforcement can concentrate on poorer neighborhoods (which are also more likely to be minority neighborhoods) to generate more busts for low-level offenses that will allow them to reach their numerical goal (NY Times). These minorities convicted of low level drug crimes now find themselves in an unfair position in comparison to their white counterparts, as they now face obstacles in getting jobs, getting professional licenses, or obtaining student loans. Thus, marijuana laws are disproportionately enforced to arrest more minorities, which leaves them with further obstacles to get their lives back on track; this systematic racism all stems from the same marijuana laws from the War on Drugs.

Although these laws are unfairly targeting minorities, the amount of total offenders for marijuana are so large that it is contributing to the overcrowding of prisons. Marijuana arrests account for a large percentage of arrests in the United States; the 587,000 arrests for marijuana related offenses accounted for about 5% of all arrests in the US, more than arrests for all crimes that the FBI classifies as violent combined (Washington Times). These high numbers of arrests do not translate well when those arrested are put into prison: around 50% of federal inmates are there for drug related crimes, with 27.6% of these drug users in prison for marijuana charges (Huff Post). The large amount of prisoners are causing problems for the prisons themselves, who are being forced to put 2 to 3 bunk beds in one room and turn open spaces into living quarters. If there was any single charge that one could point their finger towards in regards to what is causing overcrowded prisons, it’s drug offenses. Although some of those charged with drug offenses may deserve to be in federal prison, the large amount of people in for marijuana are in these prisons with people using/distributing much more dangerous drugs. Thus, marijuana users who are arguably unfairly in jail in the first place for using a drug that’s classified to be way more dangerous than it actually is are now contributing to the overcrowding of said prisons. Thus, the marijuana laws of the War on Drugs days has had a multitude of unintended consequences that has negatively impacted the communities they were trying to fix.

Because of marijuana’s laws lack of productivity and production of negative consequences, it would be best to revise these laws to decriminalize marijuana federally to reverse its adverse effects. Decriminalization means that marijuana will not be completely legal, but offenses for possessing marijuana will be treated similar to a traffic violation rather than a felony. Those caught with marijuana will receive a fine that they must pay, but they will not be arrested and the offense will not go on someone’s criminal record. The first obvious benefit of decriminalization is there will be a dramatic decrease in arrests for non-violent drug offenses, which account for 5% of all arrests in the US. Releasing those imprisoned for marijuana offenses/preventing anymore prisoners to enter the prison system on marijuana charges is a significant step in reducing the prison population, which was mostly overcrowded by drug offenders. However, decriminalization will not necessarily stop all the problems with the marijuana laws; the racial profiling and disproportionate arrests of minorities is a complex issue involving the entire criminal justice system. It does not stem entirely from the enforcement of marijuana laws. However, decriminalization is a step in the right direction to end the unfair arrests of minorities, as drug crimes is one of the largest reasons for arrest in the US, so many minorities affected by this will no longer feel these repercussions. Some may also argue that decriminalization will come with its own set of consequences, such as proliferation of substance abuse and an increase in crime as the result of no marijuana enforcement. Even if both of these consequences did happen, decriminalization has effectively prepared the government to respond to these problems in the form of saving money. From the billions of dollars that would be saved via decriminalization, the government could funnel more money into drug education/addiction facilities, or could facilitate more money to local law enforcement so that they could lock down on the increase in crime. These problems could also be stopped at their roots if more money is funneled into drug education and more people know the risks of what they’re using. Furthermore, any extra money that’s leftover from covering the unintended costs of decriminalization could be used for any other area of interest of the US government, such as infrastructure, healthcare, etc.

In conclusion, decriminalization would be an effective solution to the current failing marijuana laws as it would save the US money and help put an end to overcrowding of prisons and racial profiling in law enforcement. Although decriminalization is not perfect and does not end the debate on drug abuse on how it should be handled, it is a good solution given the benefits that will arise from it and from the fact that the original marijuana laws weren’t productive in the first place. In a country that is slowly gaining more and more support for legalization, the best place to start is by attacking at the root of these issues: the laws in place. By pushing for decriminalization, the dysfunctional laws will not only being replaced but the adverse effects that they caused will also be reversed. This is the start of change for our drug laws in the US: will you help pull the “weeds?”

Sources: https://www.safeaccessnow.org/federal_marijuana_law

http://norml.org/laws/item/federal-penalties-2

https://www.cnbc.com/id/100791442

https://www.aclu.org/gallery/marijuana-arrests-numbers

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/04/us/marijuana-arrests-four-times-as-likely-for-blacks.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/09/26/more-people-were-arrested-last-year-over-pot-than-for-murder-rape-aggravated-assault-and-robbery-combined/?utm_term=.d4205eac9285

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/10/war-on-drugs-prisons-infographic_n_4914884.html

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Why Oregon's groundbreaking drug decriminalization experiment is coming to an end

Dave Davies

In 2020, voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of hard drugs. Journalist E. Tammy Kim explains how and why public opinion has turned.

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies. In 2020, voters in Oregon overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of hard drugs, including fentanyl, heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine. The initiative was accompanied by new investments in addiction treatment and support services. The move was hailed by national drug reform advocates, who've long condemned the so-called war on drugs as a self-defeating policy that filled prisons, disproportionately harmed the poor and communities of color, and failed to deter drug use. But 3 1/2 years later, public opinion has turned against the groundbreaking approach, and the state legislature has acted to restore criminal penalties for hard drugs. The state experienced rising overdose deaths and high rates of drug use, and open air drug use in streets, parks and camping areas unnerved many residents.

Our guest, journalist E. Tammy Kim, wrote about the Oregon experience in The New Yorker, speaking with activists, treatment providers, police, lawmakers and drug users, among others. Kim is a contributing writer for The New Yorker, covering labor and the workplace, arts and culture, poverty and politics, and the Koreas. She previously worked as a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times and a staff writer for Al-Jazeera America. Kim is an attorney who worked in New York for low-wage workers and families facing medical debt before entering journalism. Her January story in The New Yorker is titled, "A Drug-Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." Well, E. Tammy Kim, welcome to FRESH AIR.

E TAMMY KIM: Thank you so much. It's a pleasure.

DAVIES: So let's set the stage for this story. November 2020 - Oregon embarks on this dramatic decriminalization of hard drugs in small amounts. This was approved in a state-wide voter referendum. So it wasn't just legislature. The voters had their say. You wrote that this was inspired by a sense of desperation. Meaning what?

KIM: This came at a time, obviously, during the pandemic, but also right after the reckoning over the summer with Black Lives Matter's protests being the largest in our nation's history. People were thinking about drug use and the addiction crisis, the opioid crisis, in a new and different way. I think in Oregon, the way that played out was people were seeing rising rates of overdose deaths. Fentanyl was coming into the market. And the previous program, which was really sort of law enforcement-based program, as it has historically been in this country, wasn't working. And I think in combination with the sort of sense of the Black Lives Matter movement saying, let's reevaluate our relationship to law enforcement more generally, people were wanting to try something new. And the form that that took was Measure 110, which was a ballot initiative that was developed both by national harm reduction and sort of criminal justice advocates, but also local activists and organizations who were interested in a new approach to the war on drugs.

DAVIES: Right. Now, this didn't legalize hard drugs, per se, right? What exactly did it provide?

KIM: It didn't. It decriminalized, which essentially meant that it took away the sort of usual policing power around use, so public use of drugs, and possession of small amounts of illicit drugs. In Oregon, meth has always been sort of the most popular illicit drug on the street. But of course, like the rest of the country, opioids have come in very strong over the past decade or so. And then kind of in distinction to the Midwest and the Northeast, where fentanyl already a decade ago was sort of overtaking oxycodone and heroin, we saw this happening sort of right before the pandemic in Oregon. And so what Measure 110 did on the policing side was to say to the police, we're not going to arrest people anymore for possession. You're going to give them an option where they can pay a fine, or they can call a hotline and sort of submit to an encounter to get counseling around treatment.

DAVIES: Right. So you'd get a ticket and then you'd either pay $100 fine or make this call and get sort of an on-the-phone evaluation, so not a heavy burden.

KIM: That's correct.

DAVIES: Right. But there was more about - more to this than the enforcement change, right? There was also supposed to be additional funding - for what?

KIM: Exactly. So Measure 110, sort of taking a sort of bird's-eye view of it, has two big prongs. So one is this change in law enforcement, so the decriminalization prong. And the other prong was a massive infusion of money from recreational marijuana tax dollars, primarily, to fund a treatment and harm reduction infrastructure across the state. A curious thing about Oregon is, I think nationally, we really think of it as a very progressive place with really advanced social services, a welfare state that's quite developed. And yet Oregon has ranked towards the bottom - by some rankings, 49th in the country - in terms of access to behavioral and mental health services. So it was sort of starting from a place of being very behind in the ability of people who wanted to get out of addiction to seek that treatment. And this was going to cure that, was the plan.

DAVIES: Right. Anybody who knows folks who've suffered with this knows that it's not easy to find treatment when you need it, and sometimes you need it right away.

KIM: Absolutely.

DAVIES: When someone's ready, you want to be able to respond.

KIM: And you need it multiple times, usually, also.

DAVIES: Right, right. Now, in addition to traditional, you know, outpatient and inpatient treatment, you know, there was this new notion of what is called harm reduction. It's a different kind of activity to deal with this issue. You want to just explain what it means?

KIM: Yeah. So what we wanted - what I was doing in this story was sort of looking at what does it mean to get treatment? And on the treatment prong of Measure 110, what was the kind of evolution in the thinking and the science around what the money would fund? And as you just said, you know, I think there's this TV version of sort of what it looks like to get out of alcohol or drug use, and it's kind of a Betty Ford clinic - right? - where you check in to a residential center, and you're kind of separated from your family and friends. You do a 90-day, you know, session, let's say, and then you kind of get out and go on your way. That's representing actually quite a limited part of the treatment infrastructure.

And what we actually have and has developed over the past few decades is this kind of continuum of care, which looks at people who aren't yet ready to give up drug and alcohol use. They need instead a safe place to perhaps do those drugs. They need supplies so that they don't get sick. You know, I think the key example for this is the free needles or needle exchange programs, which came about really in the AIDS crisis to combat the transmission of AIDS, HIV and Hep C and you know, so - but in addition to that, now people are using different kinds of drugs, consuming drugs in different ways. And so harm reduction might be, for example, giving out cookers or pipes that are safe and have been sanitized for people. So this is all to say, like on the side of people who aren't yet ready to go into a recovery or treatment program, you want to reduce the harm to themselves and to others, and then also infuse services that are more along the kind of traditional path of treatment.

DAVIES: Right. And it's a less judgmental way to deal with people who have this issue, and it also connects them to treatment if they're ready, right? The idea is that you're talking to somebody, and somebody who knows how to get you somewhere if you really want to get into a rehab or something. You know, a lot of people know that Portland is a place where politics are progressive, and there's a lot of tolerance for unhoused people and people dealing with addiction. Things changed there. But the law was statewide, and you looked at a community called Medford in southwest Oregon. You want to just talk about what some of the developments were that were troubling to some folks, and we'll get into some of the reasons for them. So what was the experience, what arose there that created issues for citizens of Medford and Jackson County?

KIM: I think on the policing side, the police had always played a very important role in the treatment infrastructure, if we can call it that. So before Measure 110, police would make arrests for misdemeanors and felonies related to drugs, obviously, and some of those were for possession - simple possession by users. The way the police saw themselves was they would make those arrests, they would bring people to the county jail and at the jail as a kind of interface point for social services and at the courthouse, they saw themselves as funneling people into treatment. You know, I think on the other side, obviously, the critics of that would say, well, you were creating harm by - just by arresting people and putting them in jail. And the jail and the court system was never really a good place for people to get treatment. There's an old adage in recovery and addiction, which is, you know, you can't get better until you're ready and that, you know, you really need to do this voluntarily. And so there's always been in that kind of dynamic.

Another thing that was going on in Southern Oregon was a steep rise in homelessness. Obviously, we've seen this across the country through the hardship of the pandemic, the mental health strains, all sorts of different reasons why people were more visibly homeless, and then, of course, the arrival of fentanyl. So we had, you know, sort of this strained system, fentanyl coming in, which is incredibly addictive and incredibly cheap and incredibly deadly, and this, you know, rise of homelessness and a backlash against homelessness. And so, I think the way that Southern Oregon was then experiencing this huge policy change under Measure 110 was, hey, Measure 110 happened when all of these bad things were happening. Therefore, it seems like Measure 110 might have caused these bad things.

DAVIES: Right. Measure 110 being the referendum which provided for the decriminalization of hard drugs. We're going to take a break here. Let me reintroduce you.

We're speaking with E. Tammy Kim. She's a contributing writer for The New Yorker. Her January story is titled, "A Drug Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." We'll continue our conversation in just a moment. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MATT ULERY'S "GAVE PROOF")

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with New Yorker contributing writer E. Tammy Kim about the end of Oregon's three-and-a-half year experiment with the decriminalization of the possession of hard drugs. She wrote a piece in January titled, "A Drug Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon."

You mentioned that there was increasing encampments of unhoused people at a greenway there in the area, and police now, under the new rules, could not apprehend people for using drugs. And so people could do it openly. What did local citizens see that they found so troubling here?

KIM: That's correct. I think there was a kind of twinning in people's minds of homelessness and the sort of physical, you know, messiness of homelessness and drug use. And under the decriminalization of drugs in Oregon, people were then essentially not able to be arrested for using drugs in public. You know, it wasn't just that they couldn't possess drugs, but that they couldn't - it wasn't just that they were able to possess drugs in public and not be arrested, it was that they could essentially use drugs in public and not be arrested. And so that did lead to more encounters by sort of, you know, your average people, your average families who were experiencing public places with drugs and drug use.

You know, we know that drug use occurs in every socioeconomic stratum. And if you have a home, if you have a place to use drugs, you're not as vulnerable, obviously, to law enforcement. But if you're using drugs in public, you know, you can be policed, but you can also have really uncomfortable interactions with people who don't like to see it. And it's not surprising that, you know, parents who were walking by, say, a homeless encampment on the greenway in Medford, Ore., and saw people smoking fentanyl or smelled something strange or saw people who were really amped up on uppers like meth would then have a really strong feeling about, hey, I don't think decriminalization is working, and this is actually making me and my community feel less safe.

DAVIES: One point I believe you wrote that the government of Medford, I guess the City Council enacted a tough anti-camping ordinance, right? What happened there?

KIM: So yeah, the Medford City Council and the Jackson County commissioners in this area, they wanted to crack down on what they called basically unauthorized camping. And what this was was a sort of combination of people who were gathering in public because they had lost housing or people who had already been homeless but were gathering in new areas because of displacement from wildfires. There were - there was a number of reasons why people were sort of moving around but that their homelessness was becoming more visible to people. And so at the same time that the police felt that they couldn't really interact with people in terms of their drug use, they were interacting with people much more in terms of their homelessness and basically prohibiting them from sleeping outside, from gathering in large groups. And this did, in a couple of instances, lead to observed harms. Activists in the area attribute the death of a man who was sleeping outside to this kind of policing.

DAVIES: Who froze to death, right?

KIM: Who froze to death. Yeah.

DAVIES: Tough weather. Yeah.

KIM: He was found in the morning.

DAVIES: There were complaints about crime. Any way to evaluate that? Was there more crime with the growth of these encampments and, you know, the open-air drug use?

KIM: One of the reasons it was hard to evaluate the asserted rise in crime rates was because before the decriminalization of drugs, a lot of drug arrests weren't simply drug arrests, per se. They were drug arrests that were made in connection with other sorts of crimes like, you know, theft or, you know, other sorts of, like, small, petty, kind of usually economic crimes. And I think one of the things that people were saying after the passage of Measure 110 was that there were kind of more people on the street who felt comfortable doing drugs and who also felt comfortable committing acts of petty theft and violence. It was difficult for me to sort of disaggregate, at least in the data that I was looking at, about, you know, whether that was true or whether that was a perception or whether the police were being sort of more vigilant about documenting those crimes as opposed to drug crimes now that they weren't working on those cases anymore.

DAVIES: You know, you just used the phrase petty theft and violence. Some might wonder, what is petty violence?

KIM: I guess I would group some of this under perceptions of disorder. So a thing that I heard repeatedly, like in Medford and Portland, Bend, Eugene, Salem, these different cities across the state was there all these people on meth who are kind of running around naked, or they are waving knives around, so this sort of thing where it wasn't necessarily that people were being assaulted, but they felt threatened by really disturbing things they were seeing on the streets. And I don't mean to say that that isn't disturbing. I think that there was a lot of harm caused by what people saw, you know, with this increased use in public.

DAVIES: You know, one of the things I liked about your story was its exploration of a debate among various folks who, in good faith, want to help drug users get clean and want to help deal with this problem in a constructive way. But there are different beliefs about what works and what doesn't. Maybe we should just start with an organization called Stabbin Wagon - its director, Melissa Jones, who sounded like she was a pretty compelling figure. Tell us what the organization and she were up to.

KIM: Melissa Jones and Stabbin Wagon are on - if we have a sort of gradient of services, are on kind of the more radical and political edge of harm reduction. And it's a group that basically owes its - all of its funding to Measure 110, to this experiment in Oregon. So for me, it was interesting to look at because it was part of the promise of Measure 110, which was that we're going to try new things. And Melissa Jones and Stabbin Wagon were trying new things in this community.

Most of what people saw of Stabbin Wagon's work was the distribution of safe use supplies and safe sex supplies and in-person outreach, delivery of meals through a white cargo van that Melissa and her staff kind of drive around town and park near where people are unhoused. And so, you know, I think for people who benefited from these services, it was a real godsend. And they felt very seen and heard by these people who weren't there to judge their drug use. But for more conservative people in town, they saw this as a representation of a very misguided social program, which is, hey, you're enabling drug use. Why are these state dollars that we voted for to fund treatment going to essentially helping people stay in their use?

DAVIES: Now, there's another point of view that you're right about, some who are more traditional treatment providers who think that addicts need some pressure to enter treatment. I mean, that pressure can come from, obviously, circumstances in their own lives, from loved ones and relatives, but also the threat of jail, where the - where there are alternatives to going to jail, particularly treatment alternatives - can be effective. Give us a sense of how that debate played out here.

KIM: Another provider that I talk about in my story is Sommer Wolcott, who is the director of OnTrack, which is a sort of large social services agency in southern Oregon. And Sommer is not at all an opponent of harm reduction. There is harm reduction sort of built into the treatment and recovery services that her organization provides. However, in some ways, her approach is quite traditional. I mean, the end goal for her interaction with their clients is recovery, to come out of addiction, to come out of drug use. They also partner with the local police in outreach to homeless people and to people who are using on the streets.

So, for example, OnTrack employees, who themselves are usually recovered people who are using drugs, will go out with Medford police officers and approach people who are using and say, hey, do you want to get into treatment? What are your needs? You know, do you need housing, this sort of thing? And, you know, again, the supply of social services is very limited, but they would sort of make that offer and try to do counseling.

And so - but there - you know, there was this contrast between what OnTrack was doing and what groups like Stabbin Wagon were doing. And I think from the OnTrack perspective, they have seen thousands of clients go through treatment and recovery. They believe it can be done. And they just felt that they needed more resources to do that. And they, too, were sort of confused about, well, where is the Measure 110 money going, and is it over-privileging the distribution, for example, of safe use supplies when really we should be having more sober homes, more recovery housing, more inpatient treatment and outpatient treatment?

DAVIES: We're going to take another break here. Let me reintroduce you. We're speaking with E. Tammy Kim. She is a contributing writer for The New Yorker. Her January story is titled, "A Drug Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." She'll be back to talk more after this short break. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies. We're speaking with New Yorker contributing writer E. Tammy Kim about the end of Oregon's 3-1/2-year experiment with decriminalizing the possession of hard drugs, including fentanyl, heroin and methamphetamine. The move to decriminalize was overwhelmingly approved by Oregon voters in November 2020, but high rates of overdose deaths and open-air drug use in streets, parks and makeshift camping areas soured public opinion, resulting in legislative action to restore criminal penalties. Other aspects of the initiative, including new investments in drug treatment and related social services, are preserved.

Tammy Kim's January article in The New Yorker is titled "A Drug Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." It seems that although this - you know, this measure which decriminalized hard drugs and provided for investments in treatment, it took quite a while for that funding to get going for reasons that are actually pretty understandable, I guess, right?

KIM: Right. That is perhaps the poison pill of this experiment in Oregon, which is that decriminalization went into effect right away. And the amped-up treatment infrastructure took about a year and a half to get going, essentially. So it took more than a year for the promised funding to begin rolling out to organizations across Oregon.

Part of that was this sort of bureaucratic issue that the organization responsible for doling out that money was also responsible for dealing with COVID. It was the Oregon Health Authority, and they were incredibly overwhelmed. There was under - it was very difficult to hire also for drug and alcohol counselors. So many things that we kind of know about because of the pandemic economy were undermining the ability of this agency to implement this program.

I think another thing that is sort of telling, just kind of thinking about this as a public policy experiment, is this is a program that came to be because of voters in our most sort of direct democratic process of a ballot initiative. However, what that meant also was that there wasn't necessarily institutional buy-in or a kind of institutional advocate for the program. So, you know, many government officials, including at the Oregon Health Authority, would sort of explain this to me as, hey, we didn't, you know, want this. We didn't ask for this. It was foisted upon us by the voters. And now we're kind of rushing to implement this. And it's not fast. It goes slow.

DAVIES: Oh, that's so interesting. So, yeah, like, if it's the governor's pet project, then he gears it up. In this case, she gears it up. But if it's the voters telling you to do it, then it's a slow start. I mean, I will say, having covered government for a long time, even if there is funding and will, it just takes a while for government programs to get up 'cause there are all of these rules that are established to prevent, you know, self-dealing and cronyism and waste. And it just - and, you know, you got to give everybody their chance to have their say. And there's competitive bidding. And it just - it all takes a while under the best of circumstances. And with COVID, it was going to be slow.

DAVIES: You write that the money distributed through this measure was both a lot and not very much. What did you mean?

KIM: About $300 million over a period of time was allocated from the marijuana taxes towards treatment and recovery. Sounds like a huge amount of money, but obviously that needs to be distributed statewide. There were also allocations to tribes. So, you know, just kind of jurisdictional, like, everybody gets a piece, but it's very spread out.

Then on top of that, if you're thinking about inpatient or outpatient treatment, these are very expensive programs. And Medicaid will often cover parts of that, but the sort of health parts of that. In addition, you also need to figure out where people are going to live and what they're going to eat while they're going through these programs. And so if you're thinking about kind of a holistic response and kind of taking person who is trying to get out of addiction from, you know, zero to 10, this is very costly. And so I think, you know, there were huge expectations placed on this experiment. And yet it was an experiment that kind of wasn't funded to address all of those hopes and dreams.

DAVIES: You refer to a December 2023 marathon hearing in the legislature, which essentially became a debate over the merits of the decriminalization measure. What complaints did lawmakers hear about it? And then let's talk about what was offered in its defense. First of all, those who favored reversing this move, what did they tell them?

KIM: Most of the people who were speaking to lawmakers against Measure 110 talked about public use and about perceived increases in dangerous drugs. Certainly, business owners also were talking about, you know, people sleeping in front of their properties and getting rowdy in front of those properties, harassing, you know, patrons of their businesses.

And so what was interesting is, I think especially listening to the people testify from Portland - was that part of that is also just the fact that Portland's downtown has been vacated since the pandemic. You know, there are no office workers there anymore. And so it has this sort of vacant quality. And that is going to be - you know, those empty spaces then have been filled by people without homes. And so, again, we're just seeing kind of like this lab experiment be infiltrated by all of the factors that weren't sort of anticipated at the time.

DAVIES: And those who wanted to defend the decriminalization initiative, what did they say in its defense?

KIM: The defenders had generally two arguments. One is that the treatment and recovery and harm reduction infrastructure is expanding and working and that they were seeing it every day. And there are countless examples of people in new detox facilities, recovery homes, in new treatment programs and new family counseling programs where those - you know, they had great stories of their clients.

And then I think the second prong is the racial justice element. Oregon is a fairly white state. However, the disproportionality statistics around drug enforcement arrests, incarceration, to some extent, those are, you know, very skewed against Black, Latino, Native people in particular. And there was a call, like, from a man named Larry Turner, who I quote, who has been doing racial justice work in Portland for a very long time in the African American community, saying, why have we given the drug war decades to do its thing? And now two, three years into this great experiment, we're going to already cut the cord. You know, we need more time to see this out. It is working for our community. And if we reverse it, we're going to go back to the kinds of racial disproportionality that we saw before.

DAVIES: So legislative leaders said, you know, we have to have some change, and a package of legislation was passed. Let's talk about what it does. I mean, what does it do in terms of, you know, rules for possession of these hard drugs?

KIM: The bills - there are two bills that were just passed by the Oregon Legislature. And one of them essentially recriminalizes. And so we're going back to the pre-Measure 110 status quo, where it is a misdemeanor to possess small amounts of illicit drugs. This sets a jail term of about six months. But there is a kind of opt-in program that counties can decide on that's called, like, deflection or diversion, where if somebody says, I'm going to go into treatment and kind of follows through with a treatment and recovery regimen, then the misdemeanor can be wiped out and they don't do jail time. And so that is the kind of, you know, harm reduction promise built into it. However, again, that part of this law is not mandatory. And so it's kind of customizable county by county.

The other bill in this package derives $211 million additional dollars, which is quite a lot to - again, to beef up the treatment infrastructure. This re-criminalization doesn't do away with the treatment and recovery part of Measure 110. Exactly. And so the funding that was going to providers will stay in place in the $211 million newly allocated will support that. And so, you know of course, always, like, devil in the details, we have to see how this is going to be implemented. I think advocates of the 2020 experiment are devastated and feel like this is just going back to the traditional drug war. But lawmakers have been taking pains to say, no, this is not exactly the same. We're just trying to do this in a more efficient way that, you know, lets law enforcement in again to help people on their way to treatment.

DAVIES: We're going to take another break here. Let me reintroduce you.

We are speaking with E. Tammy Kim. She is a contributing writer for The New Yorker. Her January story is titled, "A Drug Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." We'll continue our conversation in just a moment. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF PAQUITO D'RIVERA QUINTET'S "CONTRADANZA")

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with New Yorker contributing writer E. Tammy Kim about the end of Oregon's three-and-a-half year experiment with decriminalizing the possession of hard drugs, including fentanyl, heroin and methamphetamine, that was approved by voters in a 2020 referendum. It's now being reversed due to action by state lawmakers.

You know, the Drug Policy Alliance, which is a national organization which heavily supported the decriminalization initiative in 2020 and has criticized this, has advocated changes in a lot of different states. And I think the idea was that success in Oregon would inspire more change in other states across the country. What do you think the impact will be in other states now that we're considering changes?

KIM: This is a huge setback for the harm reduction and sort of drug reform movements. Yes, Oregon was supposed to sort of pave the way for similar changes in other places. You know, we were - the movement was eyeing California and Maine and Vermont. I think most of those efforts now are going to have a very hard time getting off the ground because of the negative press coverage and the sort of general perception that what was tried in Oregon did not work. The Oregon model also is often referred to as kind of being based on the Portugal model. You know, Portugal being a country where there has been a long history of pretty positive experiment with decriminalization and infusion of services. And so, you know, I think now that people think, well, decriminalizing just, you know, sort of isn't going to work anywhere, we probably won't see as many proposals in other states.

DAVIES: You know, police officers have been frustrated for many years with arresting people for minor drug offenses and spending a lot of time going to court and then nothing really seems to change. You talked to some police officers and prosecutors. What sense did you get of how they feel about criminal penalties for possession?

KIM: The police officers I spoke to were not enthusiastic about policing for a minor possession. You know, they obviously want to be engaged with more significant crimes. And that is the kind of demand from the community that, you know, obviously, they're responding to calls for major robberies and physical assaults, etc. However, they felt offended that they no longer had much of a role to play after decriminalization went into effect. Because, again, I think they have, in many cases, seen instances where they apprehended people, took them to jail and those people got clean and then later sort of thanked the police and the law enforcement infrastructure for that help.

DAVIES: You know, these debates about these harm reduction strategies, which, you know, try to meet drug users where they are as opposed to other methods occurring in all kinds of communities. I'm in Philadelphia, where there's a big battle here over one neighborhood that has a lot of open-air drug markets.

And one of the things that struck me as I've observed the debate is that sometimes I would see harm reduction advocates make a very persuasive case that what they're doing, which is, you know, providing, you know, clean needles and safe injection, is going to keep users alive. It's going to help them get more of them into treatment. But it's definitely going to reduce harm to the users, but they don't really address the community that feels besieged, whose kids have to, you know, walk through needles on the sidewalk and step over people, you know, shooting up and these kinds of things. And sometimes, community advocates, you know, talk about what they're seeing, but they don't really address what - you know, what will be good for these folks who are afflicted with addiction. I don't know what the question here is, but it's just - it seems a really difficult debate.

KIM: Yeah. I think you've honed in on such a key - kind of the emotional key to this whole question. And for my reporting, I went to Vancouver, British Columbia, which is - kind of has long been a sort of beacon of harm reduction. But - and so there's all sorts of practices there that are backed by science and public health researchers, like having safe injection sites, like having drug users who are involved in policy-making, decriminalizing drugs. They did that in 2022. But that doesn't mean that the streets are, you know, sunny, and everybody has a good middle-class job, and there's no, you know, problems. I mean, there's going to be a collision on the street because people are poor, because people are living in desperate circumstances, because people have mental health issues, all sorts of things. And when you throw drugs into that mix, it's a very difficult encounter.

I think your question highlights the need for strong institutional leadership, whether that comes from provincial or state, county or national leaders, to say, yes, we need to respect the human rights of drug users, and harm reduction is science and policy and so - and, you know, so are these sorts of treatment mechanisms. At the same time, we need to figure out how to respect people's desired quality of life on the streets where they live and walk. And, you know, I think a lot of this actually boils down to the question of homelessness policy and housing policy, because, again, it's this question of where are people who use drugs supposed to use drugs 'cause they are going to continue to use drugs?

DAVIES: Well, E. Tammy Kim, thank you so much for speaking with us.

KIM: Thank you. Really appreciate your time.

DAVIES: E. Tammy Kim is a contributing writer for The New Yorker. Her January story is titled "A Drug-Decriminalization Fight Erupts In Oregon." Coming up, Kevin Whitehead remembers jazz and classical and pop singer Sarah Vaughan on the 100th anniversary of her birth. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ROBBEN FORD AND BILL EVANS' "PIXIES")

Copyright © 2024 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Home — Essay Samples — Law, Crime & Punishment — Marijuana Legalization — Why Marijuana Should Be Legalized and Its Benefits

Why Marijuana Should Be Legalized and Its Benefits

- Categories: Marijuana Legalization

About this sample

Words: 1013 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 1013 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Introduction

- American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). (n.d.). The War on Marijuana in Black and White. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/report/report-war-marijuana-black-and-white

- Drug Policy Alliance. (n.d.). Marijuana Arrests by the Numbers. Retrieved from https://www.drugpolicy.org/resource/marijuana-arrests-numbers

- Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). (2014). Medical Cannabis Laws and Opioid Analgesic Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1999-2010. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1897424

- Leafly. (2020). Cannabis Jobs Report 2020. Retrieved from https://d3atagt0rnqk7k.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/07123735/Leafly-Jobs-Report-2020.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2021). Marijuana Research Report. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana

- Tax Foundation. (2016). The Budgetary Effects of Ending Drug Prohibition. Retrieved from https://taxfoundation.org/budgetary-effects-ending-drug-prohibition

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Law, Crime & Punishment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 563 words

3 pages / 1303 words

2 pages / 1060 words

1 pages / 643 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Marijuana Legalization

The debate over the legalization of weed is a contentious and multifaceted issue, with implications for medicine, economics, ethics, and society. In this essay on whether weed should be legalized, we will explore the potential [...]

The debate over the dangers of Marijuana has been a dominant topic of conversation for a long time. Unfortunately, many individuals have a problem accepting the plant’s demonstrated medicinal effects. Opinions on medical [...]

Legalizing marijuana has been a topic of debate for many years, with strong arguments on both sides of the issue. However, as scientific research and public opinion continue to evolve, it is becoming increasingly clear that the [...]

Marijuana, also known as cannabis, has been used for various medical purposes for centuries. However, its legality and acceptance as a medical treatment have been a subject of debate for many years. This essay will argue that [...]

“There are two sides to every story, and the truth usually lies somewhere in the middle.” – Jean Gati There is the “War on Drugs” on one side and Marijuana Legalization as a response to the failures of this war. The binge of [...]

The topic of cannabis legalization has been a subject of heated debate in the United Kingdom for several years. Cannabis, often referred to as weed, marijuana, pot, or hemp, is a psychoactive drug derived from the Cannabis plant [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Most americans favor legalizing marijuana for medical, recreational use, legalizing recreational marijuana viewed as good for local economies; mixed views of impact on drug use, community safety.

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand the public’s views about the legalization of marijuana in the United States. For this analysis, we surveyed 5,140 adults from Jan. 16 to Jan. 21, 2024. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for the report and its methodology .

As more states pass laws legalizing marijuana for recreational use , Americans continue to favor legalization of both medical and recreational use of the drug.

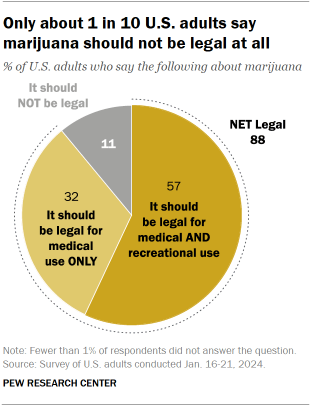

An overwhelming share of U.S. adults (88%) say marijuana should be legal for medical or recreational use.

Nearly six-in-ten Americans (57%) say that marijuana should be legal for medical and recreational purposes, while roughly a third (32%) say that marijuana should be legal for medical use only.

Just 11% of Americans say that the drug should not be legal at all.

Opinions about marijuana legalization have changed little over the past five years, according to the Pew Research Center survey, conducted Jan. 16-21, 2024, among 5,14o adults.

The impact of legalizing marijuana for recreational use

While a majority of Americans continue to say marijuana should be legal , there are varying views about the impacts of recreational legalization.

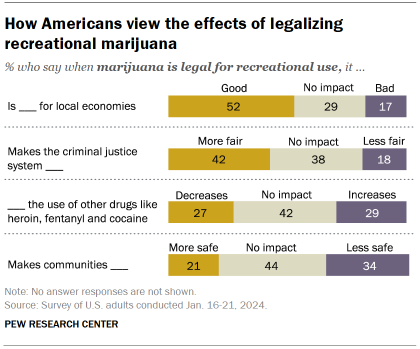

About half of Americans (52%) say that legalizing the recreational use of marijuana is good for local economies; just 17% think it is bad and 29% say it has no impact.

More adults also say legalizing marijuana for recreational use makes the criminal justice system more fair (42%) than less fair (18%); 38% say it has no impact.

However, Americans have mixed views on the impact of legalizing marijuana for recreational use on:

- Use of other drugs: About as many say it increases (29%) as say it decreases (27%) the use of other drugs, like heroin, fentanyl and cocaine (42% say it has no impact).

- Community safety: More Americans say legalizing recreational marijuana makes communities less safe (34%) than say it makes them safer (21%); 44% say it has no impact.

Partisan differences on impact of recreational use of marijuana

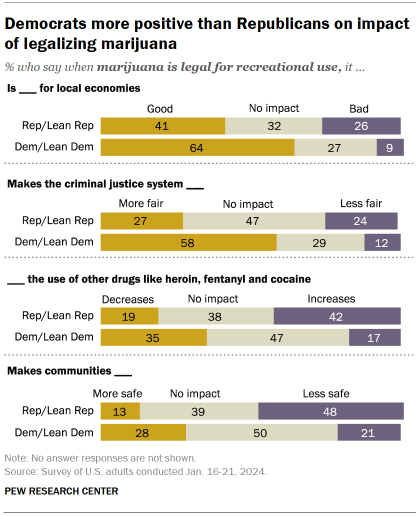

There are deep partisan divisions regarding the impact of marijuana legalization for recreational use.

Majorities of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say legalizing recreational marijuana is good for local economies (64% say this) and makes the criminal justice system fairer (58%).

Fewer Republicans and Republican leaners say legalization for recreational use has a positive effect on local economies (41%) and the criminal justice system (27%).

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to cite downsides from legalizing recreational marijuana:

- 42% of Republicans say it increases the use of other drugs, like heroin, fentanyl and cocaine, compared with just 17% of Democrats.

- 48% of Republicans say it makes communities less safe, more than double the share of Democrats (21%) who say this.

Demographic, partisan differences in views of marijuana legalization

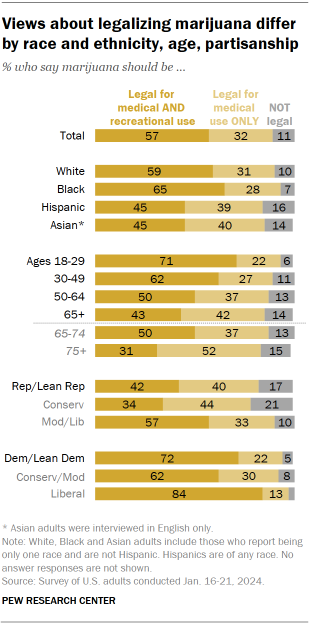

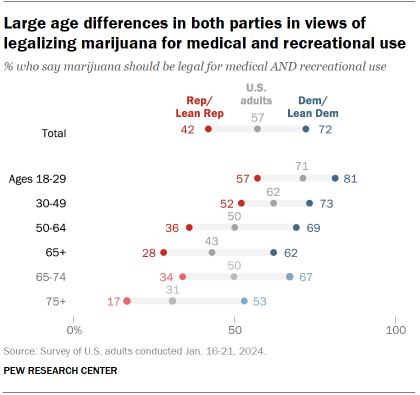

Sizable age and partisan differences persist on the issue of marijuana legalization though small shares of adults across demographic groups are completely opposed to it.

Older adults are far less likely than younger adults to favor marijuana legalization.

This is particularly the case among adults ages 75 and older: 31% say marijuana should be legal for both medical and recreational use.

By comparison, half of adults between the ages of 65 and 74 say marijuana should be legal for medical and recreational use, and larger shares in younger age groups say the same.

Republicans continue to be less supportive than Democrats of legalizing marijuana for both legal and recreational use: 42% of Republicans favor legalizing marijuana for both purposes, compared with 72% of Democrats.

There continue to be ideological differences within each party:

- 34% of conservative Republicans say marijuana should be legal for medical and recreational use, compared with a 57% majority of moderate and liberal Republicans.

- 62% of conservative and moderate Democrats say marijuana should be legal for medical and recreational use, while an overwhelming majority of liberal Democrats (84%) say this.

Views of marijuana legalization vary by age within both parties

Along with differences by party and age, there are also age differences within each party on the issue.

A 57% majority of Republicans ages 18 to 29 favor making marijuana legal for medical and recreational use, compared with 52% among those ages 30 to 49 and much smaller shares of older Republicans.

Still, wide majorities of Republicans in all age groups favor legalizing marijuana at least for medical use. Among those ages 65 and older, just 20% say marijuana should not be legal even for medical purposes.

While majorities of Democrats across all age groups support legalizing marijuana for medical and recreational use, older Democrats are less likely to say this.

About half of Democrats ages 75 and older (53%) say marijuana should be legal for both purposes, but much larger shares of younger Democrats say the same (including 81% of Democrats ages 18 to 29). Still, only 7% of Democrats ages 65 and older think marijuana should not be legalized even for medical use, similar to the share of all other Democrats who say this.

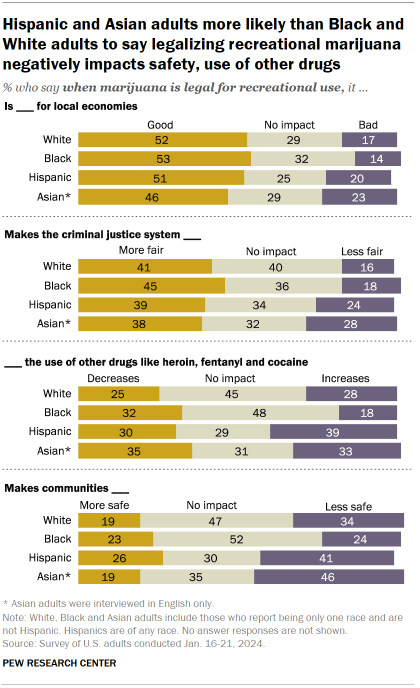

Views of the effects of legalizing recreational marijuana among racial and ethnic groups

Substantial shares of Americans across racial and ethnic groups say when marijuana is legal for recreational use, it has a more positive than negative impact on the economy and criminal justice system.

About half of White (52%), Black (53%) and Hispanic (51%) adults say legalizing recreational marijuana is good for local economies. A slightly smaller share of Asian adults (46%) say the same.

Criminal justice

Across racial and ethnic groups, about four-in-ten say that recreational marijuana being legal makes the criminal justice system fairer, with smaller shares saying it would make it less fair.

However, there are wider racial differences on questions regarding the impact of recreational marijuana on the use of other drugs and the safety of communities.

Use of other drugs

Nearly half of Black adults (48%) say recreational marijuana legalization doesn’t have an effect on the use of drugs like heroin, fentanyl and cocaine. Another 32% in this group say it decreases the use of these drugs and 18% say it increases their use.

In contrast, Hispanic adults are slightly more likely to say legal marijuana increases the use of these other drugs (39%) than to say it decreases this use (30%); 29% say it has no impact.

Among White adults, the balance of opinion is mixed: 28% say marijuana legalization increases the use of other drugs and 25% say it decreases their use (45% say it has no impact). Views among Asian adults are also mixed, though a smaller share (31%) say legalization has no impact on the use of other drugs.

Community safety

Hispanic and Asian adults also are more likely to say marijuana’s legalization makes communities less safe: 41% of Hispanic adults and 46% of Asian adults say this, compared with 34% of White adults and 24% of Black adults.

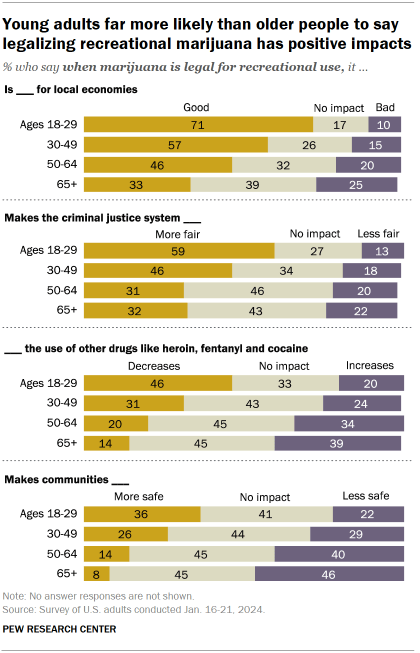

Wide age gap on views of impact of legalizing recreational marijuana

Young Americans view the legalization of marijuana for recreational use in more positive terms compared with their older counterparts.

Clear majorities of adults under 30 say it is good for local economies (71%) and that it makes the criminal justice system fairer (59%).

By comparison, a third of Americans ages 65 and older say legalizing the recreational use of marijuana is good for local economies; about as many (32%) say it makes the criminal justice system more fair.

There also are sizable differences in opinion by age about how legalizing recreational marijuana affects the use of other drugs and the safety of communities.

Facts are more important than ever

In times of uncertainty, good decisions demand good data. Please support our research with a financial contribution.

Report Materials

Table of contents, most americans now live in a legal marijuana state – and most have at least one dispensary in their county, 7 facts about americans and marijuana, americans overwhelmingly say marijuana should be legal for medical or recreational use, clear majorities of black americans favor marijuana legalization, easing of criminal penalties, religious americans are less likely to endorse legal marijuana for recreational use, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Persuasive essay

Monday, October 21, 2013

Drug legalization.

No comments:

Post a comment.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Legal Pot Pioneer Was Busted in Idaho With 56 Pounds. He Has a Plan.

At 77, Dana Beal is charged with trafficking marijuana. It could be the finale for a man who never stopped crusading even after the victory was won.

By Corey Kilgannon

In retrospect, the Idaho shortcut might have been a bad idea.

The mission had already begun to go sideways when Dana Beal — a pioneer of New York’s marijuana legalization movement but someone who has never obtained a driver’s license — enlisted a ketamine enthusiast to chauffeur him across America.

Or perhaps the fateful moment was when Mr. Beal decided to avoid the cold by staying in the minivan conked out on the shoulder of Interstate 84. That forced the helpful state trooper to come over and get a noseful of the 56 pounds of weed that Mr. Beal was bringing back to New York.

In reality, there were any number of chances for Mr. Beal, 77, to avoid his current situation: facing felony drug trafficking charges carrying a potential 15 years in prison.

Mr. Beal has spent nearly six decades challenging pot laws and is a fixture of New York’s graying counterculture, famous for handing out joints at rallies. He has undertaken many weed-buying odysseys and has wiggled out of scores of arrests. Usually, anyway. Now, despite the broad legalization of cannabis, he has managed to get arrested in one of the strictest states in the country and finds himself in his most serious jam yet.

After his Jan. 15 arrest, he spent nearly two months in jail and a fortune in prepaid phone time to mobilize his network of activists to raise a bond payment on his $250,000 bail, which freed him on March 9. He has rejected an offer to plead guilty and serve a year, and says he will “roll the dice” at trial.

He now says he will stick around Idaho. He has a plan.

“My legal strategy now hinges on me helping to legalize marijuana in Idaho,” Mr. Beal said.

Mr. Beal has made a life out of penurious activism. He was an early member of the Youth International Party, the Yippie movement known for its Dadaesque pranks and theatrical Vietnam War protests, and he lived for years in the group’s Greenwich Village headquarters, before the place was foreclosed upon in 2014.

He led civil rights demonstrations and furnished medical marijuana for AIDS and cancer patients. He helped organize Rock Against Racism concerts and the Global Marijuana March. He put together hundreds of smoke-ins, demonstrations, marches and parades, and made cross-country smuggling runs to both finance his activism and procure pot to hand out at events where he could be found carrying a giant inflatable joint.

“Nobody has pushed for the legalization of pot in New York for so many years as Dana,” said John Penley, a friend of Mr. Beal’s and a legalization advocate.

And, in 2021, he succeeded when New York legalized marijuana, as much of the rest of the country has.

But legal weed was no panacea: The prices at medical and recreational dispensaries were too steep for Mr. Beal and his longtime circle, many of whom live on fixed incomes. Mr. Beal himself was couch surfing in Manhattan after being booted out of the attic of a Midtown synagogue where he spent the pandemic lockdown.

So Mr. Beal continued his weed runs in the name of affordable pot for all, and also to raise money for his other legalization crusade: a banned psychoactive vegetable substance called ibogaine that has long been studied as a treatment for opioid addiction , Parkinson’s disease and many other ailments.

His latest scheme was to produce ibogaine abroad and then bring it to Ukrainian soldiers suffering from battlefield trauma and brain injuries. He had just finished one such mission in December before heading out to Oregon to buy a large amount of marijuana to resell in New York to fund another one.

It may have been his career finale.

Mr. Beal’s misadventure started one day in mid-January, when his ride out of southern Oregon fell through. “The truck was stolen by some speed freaks and the driver relapsed,” Mr. Beal said in a call from jail earlier this month. “Somebody put fentanyl in his ketamine.”

So Mr. Beal said he found another man headed east, albeit with a vehicle that “wasn’t up to snuff.” Thus he and his 56 pounds of pot were entrusted to a stranger who drove a 2003 minivan with a dying transmission.

Still, he had his urgent ibogaine plan to accomplish, so Mr. Beal pushed to cut through Idaho. Sure enough, the transmission expired on the interstate and the two men and the illicit cargo glided to a stop on the shoulder just outside Twin Falls.

“I thought we were going to pull over and then call for a tow,” he said, but were instead espied by a state trooper. “In less than 10 minutes, this guy pulls up on us.”

“It was all bad timing,” he said.

With temperatures well below freezing, Mr. Beal, wearing his usual tweed jacket and cowboy boots, stayed in the vehicle — another mistake, he lamented — forcing the state trooper to come to them and wind up getting a whiff of the cargo. (Mr. Beal said he regretted not having packed an air freshener.)

Mr. Beal tried his Ukraine story on the trooper, who was not buying it.

“I told him, ‘I was bringing them the medicine they really need, and now it’s on you,’” Mr. Beal said.

Mr. Beal acknowledged that the bags in the car belonged to him, the trooper said in a sworn complaint. The driver was released with a summons.

Idaho is surrounded mostly by pot friendly states and is strict about people driving through with the stuff. The authorities are especially vigilant in “corridor counties” along Interstate 84, of which Gooding County — where Mr. Beal encountered the state police — is one.

Under state law, carrying more than 25 pounds of marijuana is a felony with a mandatory minimum sentence of five years; the maximum is 15 years, with a maximum fine of $50,000.

“It’s one of the worst places in the country to possess marijuana, definitely,” Michelle Agee, Mr. Beal’s court-appointed lawyer, said. “Idaho is stuck in the 1950s as far as marijuana goes. It’s definitely the wrong place, wrong time for a person to be accused of having marijuana.”

Many longtime comrades view the Idaho debacle as just another Dana Beal mishap, but he fears that his prominence might tempt prosecutors to make him an example.

Reached for comment, Idaho’s attorney general, Raúl R. Labrador, a former Republican congressman who helped found the conservative House Freedom Caucus, said that legalization in neighboring states had done nothing to deter the strict enforcement of the laws in Idaho.

“We’ve watched how those decisions to legalize drugs have ruined other states, and Idaho demands just a bit better for our citizens and communities,” he said. “If you are trying to transport marijuana across state lines through Idaho, take the long way instead. It’ll save us money on your incarceration.”

Mr. Beal is no stranger to the cell, having been arrested during countless trips to buy weed over several decades.

In Nebraska in 2009 he was arrested with more than 100 pounds of pot. After an arrest in 2011, he spent two years in a Wisconsin prison, during which he had a double bypass operation after a nearly fatal heart attack and spent a week in a medically induced coma.

In 2017, he was busted with 22 pounds of illegal marijuana in Northern California after the authorities spotted him in a rental car weaving slowly across a road. He served no time then, nor after he was arrested in 2020 in Oregon, he said.

Mr. Beal was finally bailed out of the Gooding County Jail this month by the marijuana activist Adam Eidinger and Don Wirtshafter, a lawyer who founded the Cannabis Museum in Athens, Ohio.

In hopes of leniency, Mr. Beal said he was also trying to get Idaho prosecutors his medical records from his episode in Wisconsin.

Mr. Beal’s legalization efforts are a decided long shot. Idaho has steadfastly refused to legalize weed. But Mr. Beal said that, after a trip back to New York to regroup, he will maintain a presence in Idaho for the fight, and not just to bolster his own case.

“It’s a moral stand, man,” he said. “I’m not, like, the average guy passing through.”

Last week, he was crashing with a fellow activist in Boise and was visiting the State Capitol to wangle a meeting with a Democratic state legislator to pitch his vision for legislation.

Mr. Beal said he had teamed up with an old acquaintance whom he worked with organizing the annual Global Marijuana March, and had gotten in touch with organizers at Kind Idaho, a group advocating legal medical marijuana. He is already scheduled to speak at the Boise Hempfest on May 11 and hopes to pack the courtroom with activists when he appears at a court hearing shortly afterward.

“If they didn’t want to change the law in Idaho,” he said, “they shouldn’t have stopped me.”

Mr. Wirtshafter was not so sure. Mr. Beal is in tougher political terrain than he is used to navigating, he said.

“But he’s irrepressible,” he added. “He’ll make himself enough of a pain in the ass that they’ll either be more vengeful in their prosecution, or just get rid of him.”

If so, Mr. Beal said, he will resume the ibogaine mission now sidelined by his hasty decision to cut through Idaho.

“Looking back, I probably shouldn’t have done that,” he said. But, he explained, “I was in a rush, man. I had to get back to Ukraine.”

Corey Kilgannon is a Times reporter who writes about crime and criminal justice in and around New York City, as well as breaking news and other feature stories. More about Corey Kilgannon

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Produced by 'The Argument'. Medical marijuana is now legal in more than half of the country. The cities of Denver, Seattle, Washington and Oakland, Calif., have also decriminalized psilocybin ...

The first obvious benefit of decriminalization is there will be a dramatic decrease in arrests for non-violent drug offenses, which account for 5% of all arrests in the US. Releasing those imprisoned for marijuana offenses/preventing anymore prisoners to enter the prison system on marijuana charges is a significant step in reducing the prison ...

Why Oregon's groundbreaking drug decriminalization experiment is coming to an end In 2020, voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of hard ...

This essay will argue that marijuana should be legalized for several reasons, including its potential medical benefits, the reduction of criminal activity, and the economic advantages it offers. In the realm of medical marijuana, there is a wealth of evidence supporting its potential therapeutic properties.

This essay will discuss drug legalization issues only in America by giving valid data and considerate suggestion to explain why researcher believes drug should be legalized in the U.S. Drug can lead to multiple social problems and potential threats in most case, and there are several reasons why the US is currently suffering from serious drug ...

Marijuana Must Not Be Legalized. According to the national institute of drug abuse, the active chemical in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol, act on the region of the brain responsible for time awareness, sensory, attention, thoughts, memory and pleasure. Policy Brief: Why Marijuana Use Should Be Legalized in the Us.

Over the long term, there has been a steep rise in public support for marijuana legalization, as measured by a separate Gallup survey question that asks whether the use of marijuana should be made legal - without specifying whether it would be legalized for recreational or medical use.This year, 68% of adults say marijuana should be legal, matching the record-high support for legalization ...

As more states pass laws legalizing marijuana for recreational use, Americans continue to favor legalization of both medical and recreational use of the drug.. An overwhelming share of U.S. adults (88%) say marijuana should be legal for medical or recreational use.. Nearly six-in-ten Americans (57%) say that marijuana should be legal for medical and recreational purposes, while roughly a third ...

Some Americans believe that legalizing marijuana would have more negative outcomes than positive outcomes. Even though legalizing marijuana would increase drug use, legalizing marijuana would boost the economy because legalization would decrease crime rates and legalized marijuana would be safer for consumer use than marijuana from street dealers.

Persuasive Essay On The Legalization Of Drugs. The systematic scheduling of drugs in the United States is arbitrary which leads to a discriminative social injustice. Some psychedelic substances such as Psilocybin are schedule 1 drugs, while alcohol and nicotine are legal. According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) both alcohol and ...

A lawsuit that restricts a widely used abortion drug is unlikely to be the last challenge to Americans' reproductive freedom.

Persuasive Essay On Drug Legalization 986 Words | 4 Pages. As most people know, drug can easily make people addicted. Conventional drugs such as opium, heroin, methamphetamine (ice), morphine, marijuana, cocaine can all classify as narcotic drugs and psychotropic drugs. Drug has been a severe problem for decades.

Persuasive Essay On The Legalization Of Drugs. The systematic scheduling of drugs in the United States is arbitrary which leads to a discriminative social injustice. Some psychedelic substances such as Psilocybin are schedule 1 drugs, while alcohol and nicotine are legal. According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) both alcohol and ...

Persuasive Essay On The Legalization Of Drugs. The systematic scheduling of drugs in the United States is arbitrary which leads to a discriminative social injustice. Some psychedelic substances such as Psilocybin are schedule 1 drugs, while alcohol and nicotine are legal. According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) both alcohol and ...

Marijuana, also known as cannabis, is a psychoactive drug made from a plant and used for recreational and medical purposes. Being fully prohibited in some countries, it is fully legalized in others. In your essay about marijuana, you might want to focus on the pros and cons of its legalization. Another option is to discuss marijuana dependence.

Persuasive Essay On Drug Legalization 986 Words | 4 Pages. Recently, people being calling that they have freedom to do what the want—using drugs, and proposing legalizing using drugs. This essay will discuss drug legalization issues only in America by giving valid data and considerate suggestion to explain why researcher believes drug should ...

Legalizing marijuana could help so many people dealing with a criminal record for simply having or consuming a drug that is not doing any harm. Save your time! We can take care of your essay

Marijuana: Legalization on a federal level The federal legalization of marijuana and the positive effects it can bring to the people and our economy. Marijuana was outlawed in 1970 when the Controlled Substance Act was passed. Since the passing of this bill marijuana has be considered a harmful drug and its users have been criticized, until now.

Persuasive Speech on Marijuana Legalization. Topics: Cannabis/Medical Marijuana Marijuana Legalization. Words: 1147. Pages: 3. This essay sample was donated by a student to help the academic community. Papers provided by EduBirdie writers usually outdo students' samples.

The legalization of drugs has been at the center of interminable debate. Drugs have widely been perceived as a dominant threat to the moral fabric of society. Drug use has been attributed as the source responsible for a myriad of key issues. For instance, it is believed that drugs have exacerbated the already weak status of mental health in the ...

Drug Legalization And Decriminalization In The United States. 1745 Words; 7 Pages; ... How To Write A Persuasive Essay On Legalizing Marijuana. Twenty-six states currently have laws legalizing cannabis in some form, sixteen states have medical marijuana programs, and three states are readying a "tax and sell" or other legalization programs. ...