11 Best Tips on How to use Google Scholar

Google Scholar was my Number 1 Tool and absolute best friend as a university student. It should be yours, too.

Google Scholar is a goldmine of a resource for boosting your grades.

It makes studying easier, means you can find tons more articles than you thought you could, and often saves you a few trips into your library to find sources.

In this article I’ll show you exactly how to use Google Scholar like a Pro.

I can’t stress enough how important it is to master Google Scholar.

Whenever I found myself in a situation where I had an essay due on short notice , Google Scholar saved my life. I’ve been in situations in Northern England where my university was closed due to snowfall and the only way I could get the articles I needed to finish my essays was to use Google Scholar.

It works. And it’s saved my life a million times. I’ve written over 25 academic articles , and even as a professional, Google Scholar is my go-to source.

If you want to save time while writing your essay , Google Scholar is the source for you. In fact, even if you don’t want to save time, you really should be using Google Scholar for every single essay you write at university.

Let’s take a look under the hood and find out what Google Scholar’s all about, and how to use Google Scholar like a Pro!

1. Ditch Regular Google. Google Scholar Kicks its Butt.

Look, you’ve probably been told this a million times, but from the perspective of a professor, let me tell you: it needs to be said again. Don’t use regular Google to find information for your essay.

Okay, let me reword that: Don’t cite sources from regular Google. I know that you will probably Wikipedia key ideas, read easy-to-digest blog posts about your topics, and generally get to understand ideas through google searches. Okay, that’s fine. But that’s not what you’re going to cite in your essays. In fact, that’s what we might call Pre-Research. It’s what we do before we get serious about writing our essay .

When it’s time to get serious, you’ve got to only read and cite the quality articles written by experts. Take a look at this infographic for some ideas of what you should and shouldn’t cite:

Google Scholar is your go-to source when you want to find quality articles to cite in your essays. It filters out the nonsense for you and works hard to provide only the high-quality sources on the infographic above. It cuts out the junk to save you time.

So next time you’re wanting to cite a blog post or website, stop yourself. Go to Google Scholar, spend three minutes looking up some keywords, and cite a real scholarly source instead.

Here’s how to use Google Scholar in a nutshell:

1. Go to the Google Scholar website. Pay special attention: Google Scholar is not normal Google.

2. Type in the keywords for the topic you’re researching:

3. Read the descriptions under each search result

4. Select a source that seems relevant .

5. Read the source

6. Cite the source.

Done! It’s that simple. But wait … if you want to be a pro Google Scholar user, read on and I’ll zoom in on some strategies to take your Google Scholar searching to the next level…

2. Use Google Scholar to find the most Relevant Articles (It is way better than your University Database)

Does your university search database suck? I’m yet to find one that doesn’t.

I remember back in the 2008-2012 years when I was an undergrad using my university’s database to search for sources. Let me tell you, I could never find a source that was worth my time! I would even find it hard to find sources on mainstream, well researched topics! My university database would show up irrelevant, pointless sources – if it found any at all!

Even nowadays, University online library search databases suck at finding quality sources.

Google Scholar, on the other hand, is one great intuitive piece of software.

The reason? Most universities:

a) Don’t have access to a wide range of Journals. Each journal costs the university an annual fee of several thousand dollars. I get emails from my university regularly asking me whether it’s really worthwhile renewing a subscription to X, Y, or Z journal. I’m also constantly told that I can’t recommend articles to my students because the university doesn’t have access to those articles. But you know who probably does? Google Scholar!

b) They also don’t have an intuitive search brain. The university databases often only search for keywords in the article title. By contrast, Google Scholar searches for keywords not only in the title but also the abstract. This dramatically increases your search net and finds you articles that are more relevant to you. Thanks, Google Scholar!

3. Use Google Scholar to bypass Paywalls

Most quality scholarly articles are blocked behind paywalls. The way you get access to them is that your university pays a yearly fee to get access (see Point 2).

Google Scholar has intuitively crawled the web looking for ways to get around Journal paywalls. And, frankly, it does a really good job.

These days scholars who publish articles behind paywalls also make copies available via their own university websites or on sites like ResearchGate.net and Academia.edu. Google finds those articles for you and gives you one-click access.

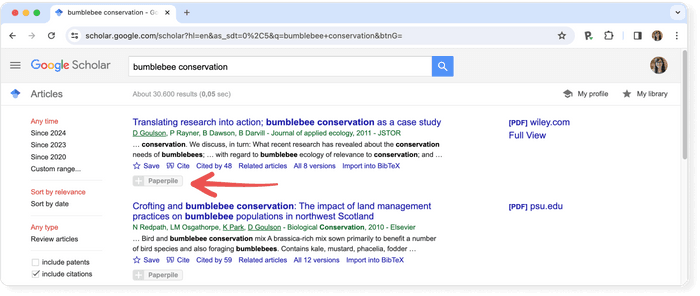

Here’s how you can take advantage of that: pay special attention to the [PDF] and [HTML] links on the right-hand side of the search results. All sources that you can have direct access to will have this link.

So, if you’re in a hurry, don’t pay attention to any others – just start looking for sources with those PDF and HTML links so you don’t waste time looking for articles you don’t have access to.

Fortunately, these days more than 50% of articles can be accessed without paywalls, all thanks to Google Scholar.

4. Link Up Google Scholar with your University Database

Okay, there’s still a purpose for your University search database. Here it is:

Google Scholar doesn’t technically have paid access to any Journals. I’ll explain to you how and why it gives you free access to so many articles in Point 4.

But it’s true, sometimes Google Scholar just can’t find you the full text of a source. Nonetheless, as I pointed out in Point 3, Google Scholar is still better at finding quality sources, even if it can’t give you access to them.

So, you should let Google Scholar know that you are attached to a University that might give you access. Then, Google Scholar will let you know if your university database can help you out.

Here’s what to do:

- Go to ‘Settings’ and ‘Library Links’.

- Enter your University’s name.

- Click Search.

- Check the box that shows your university database.

- Click Save.

- Then, go back and search for articles on Google Scholar (because it’s the best search engine for Scholarly sources!).

- Then, when you find articles that you think you want, see if Google Scholar can give you access (see Point 3 above)

- If it can’t, you should now have access to your University Database to see if your University can give you access in just one click.

5. Narrow your Search to Sources from the Past 10 Years

Has your teacher ever told you to only cite sources from the past 10 years? That’s a pretty solid piece of advice.

Google Scholar makes this so easy.

Simply conduct your search, then on the left-hand sidebar, click ‘Custom Range’ and narrow the search range to the past 10 years:

Done! Couldn’t be easier. Aren’t you glad you know how to use Google Scholar?

6. Use the ‘Cited By’ Method to find Newer (and more Relevant) Articles

Here’s where Google Scholar really comes into its own.

Let’s say you just couldn’t find a relevant source from the past 10 years. Sometimes it’s impossible!

There’s still a way around it.

Simply find an older source that still looks awesome and press the ‘Cited by’ button:

This will take you to all articles that have cited that original article. The upshot of this is that all these articles will have at least some relevance to the original article and will (naturally) also all be newer! This method often helps me find hard-to-reach articles that I can’t find any other way.

Next, to zoom in even more, you can set the custom range to the past 10 years again to find all articles that cite the original text, but happen to be new enough for you to cite!

But wait, there’s more. Let’s say you want to make sure the newer text you search for is still as relevant as possible. If you click ‘search within citing articles’, you can do a new search to find all articles that discuss the keyword you’re interested in and that cite the older text. For this example, I still wanted to look for newer articles like my original one (‘Inequality in Education’) but I also wanted to narrow it down to “gender” inequality. See below where I checked ‘Search within Citing Articles’ before searching ‘gender’:

7. Use Google Scholar to Generate Citations

Referencing is necessary, but tough. People often try to use citation generators online, but I hate citation generators. They never get citations right. And, to be honest, nor does Google Scholar’s. But, it is very convenient and helps me to get the basic skeleton of my citation that I can patch-up to make it right.

Here’s how to use Google Scholar to generate your citations:

1. Find the source you want to cite on Google Scholar.

2. Click the quote symbol beneath the source.

3. Copy the text for the citation style you are using.

4. Check it against a referencing style cheat sheet to make sure all the information is there and in the right spot.

8. Follow Author Links to find a Scholar’s Newest Articles

Another way to find more up-to-date sources is to follow an author’s list of works. When I was doing my PhD, I used an author called Neil Selwyn to examine a range of different ideas related to educational technologies . I therefore needed to be very much up to date with his complete works.

So, I went to Google Scholar, found one of his texts, and then clicked his name:

This took me to his complete list of works. I sorted them by ‘YEAR’, and hey presto! I found all of his newest ideas which I promptly read about and inserted into my thesis to improve my grade:

9. Google Scholar and Google Books work Hand-In-Hand

Google Scholar isn’t just for journal articles . You can also use Google Scholar to find relevant textbooks. Again, thanks to Google, you can read those books right on your computer – for free!

Here’s a book that I think might be relevant to my topic:

Google Scholar tells me it’s a [BOOK] and lets me click the link to go straight to the first page of the book. Sure, it’s a preview, but usually you get a good chunk of the book to read online (and can even search for keywords within the book):

If the link takes you elsewhere, you can always go to Google Books and search the full title of the book there to see if you can get access to a preview.

10. Bookmark Important Articles for Future Assignments

Sometimes one book comes in useful throughout your whole degree. My Education Studies students constantly cite a book by L. Pound that gives a really nice overview of a range of approaches to teaching. It’s a worthwhile book that students can go to in order to get great information.

So, my students often save this book in their Google Scholar bookmarks library for quick access. Simply save any book or article you love by pressing the star button under the title:

To access the books in your library, simply click ‘My Library’ in the top Menu. Here’s the first three articles saved in my library:

11. Create your own Google Scholar Profile

Academics can create their own Google Scholar profiles to claim publications of their own. I do this to claim my publications, but you should do it too – even if you’re not an author.

Because you can add ‘areas of interest’ to help Google Scholar find and recommend sources for you. You can also start to follow authors who are relevant to your studies – especially those authors whose work you use regularly (like L. Pound, who many of my students follow!)

Simply click ‘My Profile’ and then fill in the required questions.

Once you’ve made your profile, add ‘Areas of Interest’ and start following other authors. This will help Google Scholar recommend relevant articles for you in the future: Here’s the ‘Follow’ and ‘Areas of Interest’ links you might find useful:

Can you tell that I absolutely love Google Scholar? It saves time and increases my marks. What’s not to like? You need to know how to use Google Scholar!

In this post I’ve given you the advanced strategies that you need to use Google Scholar like a Pro. Use these strategies to navigate your way around, find top articles, save time, and grow your grades. Here’s a summary of the top 11 ways to use Google Scholar to grow your grades:

How to use Google Scholar Like a Pro

- Ditch Regular Google. Google Scholar Kicks its Butt.

- Use Google Scholar to find the most Relevant Articles (It is way better than your University Database)

- Use Google Scholar to bypass Paywalls

- Link Up Google Scholar with your University Database

- Use the ‘Cited By’ Method to find Newer (and more Relevant) Articles

- Use Google Scholar to Generate Citations

- Follow Author Links to find a Scholar’s Newest Articles

- Google Scholar and Google Books work Hand-In-Hand

- Bookmark Important Articles for Future Assignments

- Create your own Google Scholar Profile

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

1 thought on “11 Best Tips on How to use Google Scholar”

This is very helpful. I am even recommending it to my fellow first year students in Research and Academic Writing. Many thanks.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of academic search engines

1. Google Scholar

4. science.gov, 5. semantic scholar, 6. baidu scholar, get the most out of academic search engines, frequently asked questions about academic search engines, related articles.

Academic search engines have become the number one resource to turn to in order to find research papers and other scholarly sources. While classic academic databases like Web of Science and Scopus are locked behind paywalls, Google Scholar and others can be accessed free of charge. In order to help you get your research done fast, we have compiled the top list of free academic search engines.

Google Scholar is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only lets you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free but also often provides links to full-text PDF files.

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles

- Abstracts: only a snippet of the abstract is available

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, RIS, BibTeX

BASE is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany. That is also where its name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles (contains duplicates)

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✘

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open-access research papers. For each search result, a link to the full-text PDF or full-text web page is provided.

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles

- Links to full text: ✔ (all articles in CORE are open access)

- Export formats: BibTeX

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need anymore to query all those resources separately!

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles and reports

- Links to full text: ✔ (available for some databases)

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX (available for some databases)

Semantic Scholar is the new kid on the block. Its mission is to provide more relevant and impactful search results using AI-powered algorithms that find hidden connections and links between research topics.

- Coverage: approx. 40 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, BibTeX

Although Baidu Scholar's interface is in Chinese, its index contains research papers in English as well as Chinese.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 100 million articles

- Abstracts: only snippets of the abstract are available

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX

RefSeek searches more than one billion documents from academic and organizational websites. Its clean interface makes it especially easy to use for students and new researchers.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 1 billion documents

- Abstracts: only snippets of the article are available

- Export formats: not available

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Google Scholar is an academic search engine, and it is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only let's you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free, but also often provides links to full text PDF file.

Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature developed at the Allen Institute for AI. Sematic Scholar was publicly released in 2015 and uses advances in natural language processing to provide summaries for scholarly papers.

BASE , as its name suggest is an academic search engine. It is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany and that's where it name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open access research papers. For each search result a link to the full text PDF or full text web page is provided.

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need any more to query all those resources separately!

Stand on the shoulders of giants

Google Scholar provides a simple way to broadly search for scholarly literature. From one place, you can search across many disciplines and sources: articles, theses, books, abstracts and court opinions, from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and other web sites. Google Scholar helps you find relevant work across the world of scholarly research.

How are documents ranked?

Google Scholar aims to rank documents the way researchers do, weighing the full text of each document, where it was published, who it was written by, as well as how often and how recently it has been cited in other scholarly literature.

Features of Google Scholar

- Search all scholarly literature from one convenient place

- Explore related works, citations, authors, and publications

- Locate the complete document through your library or on the web

- Keep up with recent developments in any area of research

- Check who's citing your publications, create a public author profile

Disclaimer: Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

- Privacy & Terms

Thesis and Dissertation Guide

- Starting your Dissertation/Thesis

- Dissertation/Thesis Resources

- Books That May Help

- Literature Reviews

- Annotated Bibliography

- We Don't Have It? / Interlibrary Loan

- Online Learning Study Tips

- Search Strategy

- Advanced Search Techniques

- Kemp Library Video Tutorials

- Find Articles / Journals / Databases

- What are...

- Database Video Tutorials

- Peer Reviewed

- How to confirm and cite peer review

- Primary/Secondary Sources

- Other Types of Sources (i.e. Newspapers)

- Legal Research Resources

- Evidence Based Practice/Appraisal Resources

Google Scholar

- Website Evaluation

- Internet Searching

- Apps You Didn't Know You Needed

- Who is citing me?

- Questions After Hours

- ESU Thesis Submission

- ESU Dissertation Submission

- How to Integrate

- How to Use It

What is Google Scholar and Why Should You Care?

Google Scholar is a special division of Google that searches for academic content. It is not as robust as Google, and as such it can be harder to search. However, if you are looking for a specific article it is a fantastic resource for finding out if you can access it through your library or if it's available for free.

Below are a few videos on how to use Google Scholar (you can skip the intros if you want) that will show you tips and tricks on how to best use Google Scholar.

Did you know that you can use Google Scholar in addition to Primo to help search Kemp library materials? You just have to add us to your Google Scholar and our results will show up in your searches showing you what you have access to as an ESU community member!

- Go to Google Scholar

- Make sure you're logged into your Google Account - you'll see your initials or your icon in the top right hand corner of the screen if you're logged in.

- Click on Settings (either from the top of the Scholar home page, or from the drop-down on the right hand side of the results page).

Choose Library Links .

Type ‘East Stroudsburg University’ into the search box.

Click the boxes next to “ESU” and "Kemp Library"

Click Save .

If you have other institutions you're affilitated with, or ResearchGate, you can add them too!

Getting to Google Scholar Settings:

The Library Link Screen: Search, Select and Save!

What your search results will look like:

Add / Reorder

Databases have more sophisticated search features than Google Scholar , but if you have a one or two word topic Google Scholar can be useful. You can also try using the Advanced Search in Google Scholar (see the first video below).

However, if you're having trouble finding something specific, i.e. a specific article, try Google Scholar. For example you want " Game of Thrones and Graffiti" and you don't see it in a database, search the title of the article in Google Scholar (here you'd search "Game of Thrones and Graffiti"). You may find it freely available OR discover it is available through the library, but in a database you didn't look at.

If we don't have it and you can't access it on Google Scholar, you can always request it via interlibrary loan .

"If Google Scholar isn’t turning up what you need, try an open Google search with the article title in quotes, and type the added filter “filetype:pdf”. This scours the open web for papers hosted somewhere, by someone, in PDF format. Google Books provides limited preview access to many copyrighted books. Other alternate services include SemanticScholar , Microsoft Academic , Dimensions , or GetTheResearch . Here too there are subject-specific portals like EconBiz or the Virtual Health Library , some of which offer multilingual search options." - Paragraph taken from A Wikipedia Librarian.

The other services like Microsoft Academic mentioned above are also useful when looking for freely available journal article and research! Don't forget to cite everything you use in your paper/project/presentation/etc.

Google Scholar Videos

- << Previous: Evidence Based Practice/Appraisal Resources

- Next: Website Evaluation >>

- Last Updated: Mar 29, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://esu.libguides.com/thesis

- Library databases

- Library website

Full-Text Articles: Articles at Google Scholar

Google scholar.

Find scholarly content on the web with Google Scholar. It's useful for conducting comprehensive literature reviews beyond Walden Library.

Learn more from this guide:

- Google Scholar by Jon Allinder Last Updated Aug 16, 2023 8866 views this year

Find an article at Google Scholar

If Walden doesn't have an article you want, check Google Scholar. You may find a free copy online.

If there is no link on the right:

- Click the article title. Though rare, you may get it free from the publisher. You might also see how much it costs if you're interested in buying it.

- Try searching regular Google .

- Buy the article.

- Use the Document Delivery Service . Remember, it can take 7-10 business days to get an article from DDS.

Connect Google Scholar to the Walden Library

Option 1: search using google scholar pre-connected to the walden library.

Access Google Scholar directly through the Library's website to use a pre-connected version .

Option 2: Manually connect Google Scholar to Walden Library

Follow these steps to manually link Google Scholar to the Walden Library collection:

- Go to Google Scholar (scholar.google.com).

- In the search box, type in Walden and click the Search button.

- Click Save. Google Scholar will remember this setting until you clear your browser cookies . Now when you search Google Scholar, you will see Find @ Walden links to the right of articles available in the Library.

- When you click on Find @ Walden you will be asked to login with your Walden username and password.

- You may see a list of databases that contain the article; you will need to click on one of these database links to be taken to the article.

- Pay attention to the years listed by the database links, as databases may have different publication years available. Click on the database you want to try and it should take you to the article.

- Previous Page: Find an Exact Article

- Next Page: Buy an Article

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Ask a Librarian

Citation Databases

- Searching Scopus

- Researcher Profiles

- Researcher IDs

- Searching Web of Science

- Google Scholar

- Research Impact and Metrics

Introduction to Google Scholar

Google Scholar is the largest citation search-base in the world, though it suffers from some difficulties it is the most widely used of all such search engines. The reason for this is that author profiles in Google Scholar tend to index the entirety of an author’s output. The database is maintained by a powerful algorithm which searches the entire internet for citations, documents, and other research output. However, not all of the material which can be found in Google Scholar is peer-reviewed so remember that it is up to you to be a critical consumer of information. Google Scholar cannot sort by research field or type, browse by title, and cannot limit search results (except for by year).

Uses for Researchers

There are many use cases of Google Scholar for researchers, the most obvious cases are literature reviews and making note of research trends. Searching Google Scholar is easy, and by making use of some of the tips below you will be able to narrow your search results.

Search Tips

Here are some easy search tips for using Google Scholar.

Opening Advanced search: to open advanced search navigate to the three lines at the top left of the google scholar home page, click on that and then click on advanced search.

Using “Boolean Operators” such as ‘AND’ as well as ‘OR’ can allow you to search for things which include specific words

Using the command “intitle:” we can do an in title search, so for example “Intitle: “Romanitas” Roman”' will search for articles with “Romanitas” in the title and the word “Roman” in the text of the article. This can help you to find articles with specific content.

Cited by References search is a powerful tool which allows you to search for articles that have cited a particular article. Search for an article and then click “cited by” under the entry.

Setting library links can be done by clicking “settings”, clicking on “library links” and then searching for “Purdue”, and finally clicking “save”. This will allow you to access materials you find on Google Scholar directly from your searches

Your path to academic success

Improve your paper with our award-winning Proofreading Services , Plagiarism Checker , Citation Generator , AI Detector & Knowledge Base .

Proofreading & Editing

Get expert help from Scribbr’s academic editors, who will proofread and edit your essay, paper, or dissertation to perfection.

Plagiarism Checker

Detect and resolve unintentional plagiarism with the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker, so you can submit your paper with confidence.

Citation Generator

Generate accurate citations with Scribbr’s free citation generator and save hours of repetitive work.

Happy to help you

You’re not alone. Together with our team and highly qualified editors , we help you answer all your questions about academic writing.

Open 24/7 – 365 days a year. Always available to help you.

Very satisfied students

This is our reason for working. We want to make all students happy, every day.

It is not my first time using scribbr…

It is not my first time using scribbr and honestly, you impress me with your proofreading services every time. Checking mistakes, editing and paraphrasing are excellent.

Good Citation Generator

Scribbr works, and is reliable. I use it for all my research papers. Although it doesn't pick up on everything in each source, and I often need to put in a date or whatever into the source, it is good for organising and generally helping make sure your sources are correct and look good. Scribbr's citation generator is reliable; I consistently use it when I am researching. It's good at accurately formatting, and organising the citations, however, most times it doesn't not record every detail from each source. For example, I often have to manually put in a date, or the correct title. In saying this, Scribbr is a great tool for correctly formatting your sources. :)

All I can say is that the Scribbr work…

All I can say is that the Scribbr work engine is great. Thank you.

It helps with school

Reference page made easy

Using the platform to store my references. With the edit button I can easily add all information necessary and as I add references it places it alphabetically and I can them generate to a word document.

Great experience

Great experience using scribbr. I recommend it any day and at anytime

Awesome support and a great tool

Awesome support and a great tool. I really enjoyed using this website.

Fantastic website!

Fantastic website! Citations are available in multiple formats (APA, MLA, etc.) The only occasional issues I run into are around logging in.

Great free citation service

Great free citation service, Much better than citation generator. Must use!

This site has saved me when writing my…

This site has saved me when writing my papers. It always has my references save and able to give me the cite notation. They give you options on how you need the citations to be. This site is awesome.

Thank you Scribbr.

The ability to create and save multiple folder for different project. I have find using Scribbr for citing of many of my term papers, projects, and assignments more helpful than I could imagine. Thank you Scribbr.

This is one of the best citation generators. Currently a uni student and this has saved my life

I enjoy Scribbr! My papers and sources are phenomenal

I enjoy Scribbr as it makes my writing formats easier to generate without confusion or too much thought. If any information is missing, I still have the ability to edit and makes changes to add more details. Also, what makes this program great is the ability to show a narrative citation and paraphrasing which in some cases can be difficult for me to generate when I am not trying to copy every bit of a quote. Additionally, the formats are saved at the bottom in alphabetical order so you may copy all the citations you need or select a few. You may also edit the same saved citation and change the formats for other papers that vary from APA to MLA.

Scribbr never fails!

Great site, easy to use, and excellent processing speed. I've been using Scribbr's citation generator for years now and it has never failed. The search engine is near perfect and the formatting options are extensive. I am so grateful for Scribbr, it has made citing sources less of a headache, cannot praise this site enough!

Great site for APA citations

I love the site because it helps me with proper APA citations.

Excellent software and very helpful if…

Excellent software and very helpful if you accidentally delete a reference list. I contacted via whatsapp and got an immediate call back.

good great!

Scribbr is quick and easy

Scribbr is quick and easy. I can get all my citations either in APA or MLA format in the matter of seconds. Without this, I wouldn't know what to do

They have helped me through both…

They have helped me through both undergrad and grad school.

This is super easy to use and accurate.

This is super easy to use and accurate. The only issue is double-checking citations after they are put into your Word document, as formatting and capitalization might be incorrect.

Everything you need to write an A-grade paper

Free resources used by 5,000,000 students every month.

Bite-sized videos that guide you through the writing process. Get the popcorn, sit back, and learn!

Lecture slides

Ready-made slides for teachers and professors that want to kickstart their lectures.

- Academic writing

- Citing sources

- Methodology

- Research process

- Dissertation structure

- Language rules

Accessible how-to guides full of examples that help you write a flawless essay, proposal, or dissertation.

Chrome extension

Cite any page or article with a single click right from your browser.

Time-saving templates that you can download and edit in Word or Google Docs.

Help you achieve your academic goals

Whether we’re proofreading and editing , checking for plagiarism or AI content , generating citations, or writing useful Knowledge Base articles , our aim is to support students on their journey to become better academic writers.

We believe that every student should have the right tools for academic success. Free tools like a paraphrasing tool , grammar checker, summarizer and an AI Proofreader . We pave the way to your academic degree.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Frequently asked questions

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier Sponsored Documents

The persuasive essays for rating, selecting, and understanding argumentative and discourse elements (PERSUADE) corpus 1.0

This paper introduces the Persuasive Essays for Rating, Selecting, and Understanding Argumentative and Discourse Elements (PERSUADE) corpus.The PERSUADE corpus is large-scale corpus of writing with annotated discourse elements. The goal of the corpus is to spur the development of new, open-source scoring algorithms that identify discourse elements in argumentative writing to open new avenues for the development of automatic writing evaluation systems that focus more specifically on the semantic and organizational elements of student writing

- • We introduce the PERSUADE corpus.

- • The corpus contains over 25,000 essays with annotated discourse elements.

- • The PERSUADE corpus can be used to assess writing quality.

1. Introduction

Writing is an essential skill for college and career success. Still, many students struggle to produce writing that meets college and career standards (NCES, 2012). One way to help students improve their writing is to provide students with more opportunities to write and receive feedback on their writing ( Graham & Perin, 2007 ). However, assigning more writing to students places a burden on teachers to generate timely feedback. One potential solution is the use of automated writing evaluation (AWE) systems, which can evaluate student writing and provide feedback independently. These kinds of systems can encourage students to write and revise more frequently and reduce the amount of time that teachers spend grading ( Strobl et al., 2019 ).

The feedback algorithms found in AWE systems rely on corpora of essays that have been generally hand-coded by raters for specific elements related to writing. These elements may include holistic scores of writing quality ( Shermis, 2014 ), analytic scores of quality that focus on specific text elements like organization, grammar, or vocabulary use ( Crossley & McNamara, 2010 ), or annotations of argumentative elements like claims ( Stab & Gurevych, 2017 ). However, large corpora that are annotated for argumentative elements are non-existent, thus making it difficult for AWE systems to provide accurate and reliable feedback on important elements of writing success.

Here, we introduce the Persuasive Essays for Rating, Selecting, and Understanding Argumentative and Discourse Elements (PERSUADE) corpus. The PERSUADE corpus is an open-source corpus comprising over 25,000 essays annotated for argumentative and discourse elements and relationships between these elements. In addition, the PERSUADE corpus includes detailed demographic information for the writers.

Our goal in releasing the corpus is to spur the development of new, open-source scoring algorithms that identify discourse elements in argumentative writing. Because the PERSUADE corpus also includes detailed demographic information, developed algorithms can also be assessed for potential bias to ensure they do not favor one population over another. Once developed, algorithms can be included in AWE systems to provide more pinpointed feedback to writers about their use of argumentative and discourse elements. Such feedback would open new avenues for the development of AWE systems that focus more specifically on the semantic and organizational elements of student writing.

The PERSUADE corpus was pulled from a larger corpus of student writing (N = ~500,000). The PERSUADE corpus comprises two sub-corpora consisting of source-based essays (n = 12,875) and independent essays (n = 13,121). Source-based writing requires the student to refer to a text while independent writing excludes this requirement. The source-based set was derived from seven unique writing prompts and related sources. The writing reflects students in grades 6 through 10. The independent set reflects writing where background knowledge of the topic was not a requirement, and no sources were required to produce the texts. The independent sub-corpus was collected from students in grades 8 through 12, and the collection was derived from eight unique writing prompts. All prompts and sources are available within the PERSUADE corpus.

The PERSUADE corpus was limited to essays with a minimum of 150 words of which 75% had to be correctly spelled American English words. These filters were used to ensure appropriate coverage of argumentative and discourse elements in the texts as well as to ensure the essays contained enough language from which to develop natural language processing (NLP) features to inform algorithm development ( Crossley, 2018 ). Additionally, the filters help to confirm that the essays were written in English and that the essays did not contain a large amount of gibberish. Descriptive statistics for number of words, number of sentences, and number of paragraphs per essay are reported in Table 1 .

Descriptive statistic for PERSUADE corpus.

The PERSUADE corpus was selected to reflect a range of writing from diverse student populations that was representative of the writing population in the United States. All essays in the PERSUADE corpus are linked to information on the student’s gender and race/ethnicity. A subset of the corpus (n = 20,759) also contains data on student eligibility for federal assistance programs such as free or reduced-price school lunch, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs, which we broadly define as economic disadvantage. A large sub-sample of the essays in the corpus also includes information on English Language Learner status (n = 24,787) and disability status (n = 24,828). The racial, gender, and economic composition of the corpus collection closely resembles the U.S. secondary public school population using data from the National Center for Education Statistics as a benchmark. Descriptive statistics on demographic representation in terms of economic disadvantage and race/ethnicity are reported in Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 , Fig. 3 , Fig. 4 .

Economic composition of PERSUADE corpus authors, text-dependent essays.

Economic composition of PERSUADE corpus authors, independent essays.

Racial/ethnic composition of PERSUADE corpus authors, text-dependent essays.

Racial/ethnic composition of PERSUADE authors, independent essays.

Each essay in the PERSUADE corpus was human annotated for argumentative and discourse elements as well as relationships between argumentative elements. The corpus was annotated using a double-blind rating process with 100% adjudication such that each essay was independently reviewed by two expert raters and adjudicated by a third expert rater. All ratings were completed by an educational consulting firm in the United States and by raters with at least two years of experience. Prior to norming, raters received anti-bias training and anti-bias strategy instruction that was designed to address issues of bias that occur during scoring and are inherent to the use of standardized rubrics ( Warner, 2018 ). Raters used an annotation platform provided by a third-party commercial partner that allowed raters to highlight text segments of an essay, assign a discourse element category to each segment, and provide effectiveness ratings and hierarchical relations for that segment. Raters were trained on each prompt separately and on independent and source-based essays separately. Raters were provided with bridge sets for each prompt that included essays of varying quality. Ratings were spot-checked throughout the process to ensure rater accuracy.

The annotation rubric was developed to identify and evaluate discourse elements commonly found in argumentative writing. The rubric was developed in-house and went through multiple revisions based on feedback from two teacher panels as well as feedback from a research advisory board comprising experts in the fields of writing, discourse processing, linguistics, and machine learning. The discourse elements chosen for this rubric come from Nussbaum, Kardash, and Graham (2005) and Stapleton and Wu (2015) . Both annotation schemes are adapted or simplified versions of the Toulmin argumentative framework (1958). Elements scored and brief descriptions for the elements are provided below.

Lead. An introduction that begins with a statistic, a quotation, a description, or some other device to grab the reader’s attention and point toward the thesis.

Position. An opinion or conclusion on the main question.

Claim . A claim that supports the position.

Counterclaim. A claim that refutes another claim or gives an opposing reason to the position.

Rebuttal. A claim that refutes a counterclaim.

Evidence. Ideas or examples that support claims, counterclaims, rebuttals, or the position.

Concluding Statement. A concluding statement that restates the position and claims.

Relationships between the argumentative elements are illustrated through a hierarchical organization inspired by Rhetorical Structure Theory ( Mann & Thompson, 1988 ) and general tree structures. The purpose of the relationships is to examine organization and coherence among argumentative elements at the text level. Each argumentative element is marked as a parent, child, or sibling of another element. For example, a claim that supports a position is annotated as the child of the position. Supporting evidence for the claim is annotated as a child of the claim. If two pieces of evidence are provided for a claim, they will both be labeled children of the claim and siblings of one another. An overview of these relationships is depicted in Fig. 5 .

Prototypical Diagram for Relations Among Argumentation Elements.

2. Learning objectives and related research

Argumentation can be viewed as a logical appeal that involves stating claims and offering support to justify or refute beliefs to influence others ( Newell, Beach, Smith, & VanDerHeide, 2011 ). The ability to persuade with good argumentation skills lies at the core of critical thinking and has long been valued in personal, professional, and academic contexts. Given the important role of argumentation in students’ cognitive development and academic learning, the K-12 Common Core State Standards (2010) highlights the cultivation of argumentation skills in writing instruction and stipulates that students need to achieve proficiency in using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence to support claims. However, many students in the U.S. struggle to construct a solid argument in writing due to its cognitively demanding nature. According to the 2012 NAEP Writing Report Card, only about 25% of students' argumentative essays were competent. Thus, systematic analysis of the arguments in students' essays informed through in-depth understanding of informal reasoning and written argumentation affords tremendous pedagogical values.

Identifying the generic elements that compose an argument is the starting point for analyzing arguments in students' essays. Although argument has been interpreted and conceptualized differently depending on specific sets of theoretical assumptions ( Newell et al., 2011 ), research has generally indicated that Toulmin (1958) model of informal argument and its variations are effective in capturing the type of organizational structures in students' argumentative writing (e.g., Knudson, 1992 ). Toulmin's model of argument revolves around three key elements: a claim , or the assertion to be argued for, data that provide the supportive evidence (empirical or experiential) for the claim, and a warrant that explains how the data support the claim. To capture the different aspects related to the nature of human reasoning, Toulmin also added three other argument elements: backing that affords justifications for the warrant, qualifiers to signal the strength of the argument, and rebuttals that denote exceptions to the elements of the argument.

Whereas Toulmin's model lends itself well to the analysis and construction of single claims, it is less helpful to deal with the structure of arguments at the macro level ( Wingate, 2012 ). Therefore, modified versions of Toulmin’s model have been developed to attend to the macrostructure of written argumentation. For instance, Nussbaum et al. (2005) adapted Toulmin's model to feature an opinion or a conclusion on the main question ( final claim ) which is usually supported by one or more reasons ( primary claims ) or claims ( rebuttals ) refuting some potentially opposing opinions ( counterclaims ). Nussbaum et al. also included into the model supporting reasons or examples used to back up the stated claims. Similarly, Qin and Karabacak (2010) used a coding scheme based on Toulmin's model that comprised six elements: claim , data , counterargument claim , counterargument data , rebuttal claim , and rebuttal data to identify argument elements in argumentative essays.

There are many problems with relying solely on prototypical argumentative discourse schema like those laid out by Toulmin. One problem is that such approaches are not based on theories of text analysis and may thus lack construct relevancy ( Azar, 1999 ). Additionally, discourse schemas do not show relations at the text level, giving the impression that essays are static and making it difficult to understand how argumentative elements can shape an entire text ( Freeman, 2011 ). To address these problems, Mann and Thompson (1988) developed Rhetorical Structure Theory (RST) which helps to arrange and connect parts of a text type to construct a whole. RST does this by focusing on relationships between discourse elements to demonstrate how a whole text functions. Specifically, discourse elements are connected through a small set of rhetorical relations that break texts into segments and develops relationships between segments to connect them coherently ( Azar, 1999 ). Azar concluded that RST was a useful tool for modeling argumentative text that complemented Toulmin’s approach. Green (2010) also adopted RST to model argumentative texts by using hierarchical trees to identify how evidence can link a claim with its argument and how a background relationship can link evidence with its warrant.

3. Connections

There are few currently available corpora that focus on assessing argumentation in persuasive writing and none that include rhetorical features like leads or concluding summaries. While existing corpora provide annotations for argumentative elements, the corpora are small, do not contain detailed argumentative features, do not focus on argumentative relationships, and do not contain demographic information.

The two best known corpora annotated for argumentative elements were released by Stab and Gurevych, 2014 , Stab and Gurevych, 2017 . Their initial corpus released in 2014 was small and consisted of 90 essays. The argument components annotated include major claims , claims , and premises . Major claims referred to sentences that directly expressed the general stance of the author that was supported by additional arguments. Claims were the central component of an argument, and premises were reasons that supported the claims. Stab and Gurevych also annotated the relationships between premises and major claims or claims in terms of whether they supported the claims or not. A follow up corpus followed the same annotation procedure and was released in 2017. This corpus contained 402 argumentative essays written by students (including the original 90 essays in the 2014 corpus). Both corpora were publicly released in order to increase access to annotated instances of argumentation in essays.

4. Limitations and future steps

The PERSUADE corpus was the foundation for the Feedback Prize competition hosted by Kaggle, an online community of data scientists. The Feedback Prize sought to develop machine learning models to best classify discourse elements in the PERSUADE corpus. Over 2000 teams participated, and the twelve top teams shared $160,000 in prize money. The winning model reported a classification accuracy for argumentative and discourse elements of just over 75%. All winning algorithms and the training portion of the PERSUADE corpus are freely available on the Feedback Prize Kaggle website (https://www.kaggle.com/c/feedback-prize-2021).

As a large-scale, open-sourced corpus of annotated discourse elements, the PERSUADE is unparalleled. However, it does have limitations. For instance, the corpus only focuses on 6–12th grade writers, leaving out younger writers developing proficiency and older, more proficient writers. The corpus also has a limited number of prompts (N = 15) and the current release of the PERSUADE corpus does not include quality ratings for the discourse elements or the essay as a whole. Lastly, the corpus only focuses on independent and integrated writing tasks (i.e., argumentative essays). Argumentative essays are overrepresented in secondary schools and first-year composition courses, especially when compared to the types of writing (e.g., explanatory writing) that students are exposed to in their post-secondary courses ( Aull and Ross, 2020 , Aull, 2019 ). In this sense, the PERSUADE corpus may lead to increased generalizations about the narrowness of academic writing that favors argumentation over other types of persuasion. This may be compounded if models to classify argument types based on PERSUADE are incorporated into AWE systems as planned. AWE systems, which have wide uptake, have the potential to further popularize the notion that academic writing is best represented through argumentation. Thus, future corpora would benefit from the inclusion of writing samples from compare-and-contrast essays, research reports, and analysis papers.

While the PERSUADE corpus was designed for machine learning, it is available to anyone, and we envision it will be used by writing researchers interested in both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. We also presume that the PERSUADE corpus could be used for other pedagogical applications including student-centered assessment, the development of heuristics for explicit genre knowledge, descriptive feedback in peer-reviews, and other uses developed by classroom teachers and writing program administrators.

Our next steps are to collect quality ratings for the individual discourse elements and the essays. We will then host additional Kaggle competitions to develop algorithms to predict discourse element quality and holistic essay score. Once those competition are completed, the entire PERSUADE corpus will be released publicly on Kaggle and other websites.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and Schmidt Futures for their support.

Scott Crossley is a professor of Applied Linguistics and Computer Sciences at Georgia State University. His primary research focus is on natural language processing and the application of computational tools and machine learning algorithms in language learning, writing, and text comprehensibility. His main interest area is the development and use of natural language processing tools in assessing writing quality and text difficulty.

Troubleshooting

Inclusion Guidelines for Webmasters

This documentation describes the technology behind indexing of websites with scholarly articles in Google Scholar. It's written for webmasters who would like their papers included in Google Scholar search results. Detailed technical information is helpful if you're trying to fix an error in indexing of your own website, or you need to make sure that your article hosting product is compatible with Google and Google Scholar search services.

Individual Authors

If you're an individual author, it works best to simply upload your paper to your website, e.g., www.example.edu/~professor/jpdr2009.pdf; and add a link to it on your publications page, such as www.example.edu/~professor/publications.html. Make sure that:

- the full text of your paper is in a PDF file that ends with ".pdf",

- the title of the paper appears in a large font on top of the first page,

- the authors of the paper are listed right below the title on a separate line, and

- there's a bibliography section titled, e.g., "References" or "Bibliography" at the end.

That's it! Our search robots should normally find your paper and include it in Google Scholar within several weeks.

If it doesn't work, you could either (1) read more detailed technical guidelines in this documentation or (2) check if your local institutional repository is already configured for indexing in Google Scholar, and upload your papers there.

University Repositories

If you're a university repository, we recommend that you use the latest version of Eprints (eprints.org), Digital Commons (digitalcommons.bepress.com), or DSpace (dspace.org) software to host your papers.

If you use a less common hosting product or service, or an older version of these, please read this entire documentation and make sure that your website meets our technical guidelines.

Journal Publishers

If you publish a small number of journals, consider using one of the established journal hosting services, e.g., Atypon, Highwire, Ingenta and Silverchair. Aggregators that host many journals on a single website, such as JSTOR or SciELO, often work too, but please check with your aggregator to make sure that they support full-text indexing in Google Scholar. Alternatively, if you have the technical expertise to manage your own website, we recommend the Open Journal Systems (OJS) software that's available for download from the Public Knowledge Project (PKP).

If you use a smaller journal hosting service, or if you maintain your own custom website, please read this entire documentation and make sure that your website meets our technical guidelines.

Content Guidelines

Google Scholar includes scholarly articles from a wide variety of sources in all fields of research, all languages, all countries, and over all time periods. Chances are that your collection of research papers will be a welcome addition to the index. To be considered for inclusion, the content of your website needs to meet the two basic criteria.

1. Scholarly articles

The content hosted on your website must consist primarily of scholarly articles - journal papers, conference papers, technical reports, or their drafts, dissertations, pre-prints, post-prints, or abstracts. Content such as news or magazine articles, book reviews, and editorials is not appropriate for Google Scholar. Documents larger than 5MB, such as books and long dissertations, should be uploaded to Google Book Search; Google Scholar automatically includes scholarly works from Google Book Search.

2. Showing abstracts

Users click through to your website to read your articles. To be included, your website must make either the full text of the articles or their complete author-written abstracts freely available and easy to see when users click on your URLs in Google search results. Your website must not require users (or search robots) to sign in, install special software, accept disclaimers, dismiss popup or interstitial advertisements, click on links or buttons, or scroll down the page before they can read the entire abstract of the paper. Sites that show login pages, error pages, or bare bibliographic data without abstracts will not be considered for inclusion and may be removed from Google Scholar.

Crawl Guidelines

Google Scholar uses automated software, known as "robots" or "crawlers", to fetch your files for inclusion in the search results. It operates similarly to regular Google search. Your website needs to be structured in a way that makes it possible to "crawl" it in this manner. In particular, automatic crawlers need to be able to discover and fetch the URLs of all your articles, as well as to periodically refresh their content from your website.

1. File formats

Your files need to be either in the HTML or in the PDF format. PDF files must have searchable text, i.e., you must be able to search for and find words in the document using Adobe Acrobat Reader.

Each file must not exceed 5MB in size. To index larger files, or to index scanned images of pages that require OCR, please upload them to Google Book Search.

2. Browse interface

A browse interface is necessary for the search robots to discover the URLs of your articles. We recommend that the URL of every article is reachable from the homepage by following at most ten simple HTML links . Here're several common ways to organize a website that make it easy for the search robots to find and index all of the articles.

If you're hosting a small collection of publications, such as papers written by a single author or a small group, then we recommend that you list all articles on a single HTML page, such as www.example.edu/~professor/publications.html, and include links to their full text in the PDF format.

If your website has thousands of papers or more, the best way to make sure they're all discovered by the search robots is to provide a way to list them by the date of publication or the date of record entry. Other forms of browse interfaces, such as browse by author or by keyword, often generate more URLs than your website can deliver to the search robots in a reasonable amount of time.

For websites with more than a hundred thousand papers, we recommend that you create an additional browse interface that lists only the articles added in the last two weeks. This smaller set of webpages can be recrawled more frequently than your entire browse interface, which will facilitate timely coverage of your recent papers by the search robots.

Keep in mind that the use of Flash, JavaScript, or form-based navigation makes it hard for our automated system to find your articles. If your website uses these types of navigation, please also add a "browse by date" interface that uses only simple HTML GET links.

3. Website availability

Since Google refers users to your website to read the papers, your webpages must be available to both users and crawlers at all times. The search robots will visit your webpages periodically in order to pick up the updates, as well as to ensure that your URLs are still available. If the search robots are unable to fetch your webpages, e.g., due to server errors, misconfiguration, or an overly slow response from your website, then some or all of your articles could drop out of Google and Google Scholar.

- Use HTTP 5xx codes to indicate temporary errors that should be retried soon, such as temporary shortage of backend capacity.

- Use HTTP 4xx codes to indicate permanent errors that should not be retried for some time, such as file not found.

- If you need to move your articles to new URLs, set up HTTP 301 redirects from the old location of each article to its new location. Do not redirect article URLs to the homepage - users need to see at least the abstract when they click on your URL in Google results.

4. Robots exclusion protocol

If your website uses a robots.txt file, e.g., www.example.com/robots.txt, then it must not block Google's search robots from accessing your articles or your browse URLs. Conversely, it should block robots from accessing large dynamically generated spaces that aren't useful in the discovery of your articles, such as shopping carts, comment forms, or results of your own keyword search.

E.g., to let Google's robots access all URLs on your site, add the following section to your robots.txt:

User-agent: Googlebot Allow: /

Or, to block all robots from adding articles to your shopping cart, add the following:

User-agent: * Disallow: /add_cart.php

Refer to http://www.robotstxt.org/ for more information about robots.txt files.

Indexing Guidelines

Google Scholar uses automated software, known as "parsers", to identify bibliographic data of your papers, as well as references between the papers. Incorrect identification of bibliographic data or references will lead to poor indexing of your site. Some documents may not be included at all, some may be included with incorrect author names or titles, and some may rank lower in the search results, because their (incorrect) bibliographic data would not match (correct) references to them from other papers. To avoid such problems, you need to provide bibliographic data and references in a way that automated "parser" software can process.

1. Preparing article URLs

Place each article and each abstract in a separate HTML or PDF file. At this time, we're unable to effectively index multiple abstracts on the same webpage or multiple papers in the same PDF file. Likewise, we're unable to index different sections of the same paper in different files. Each paper must have its own unique URL in order for it to be included in Google Scholar.

2. Configuring the meta-tags

If you're using repository or journal management software, such as Eprints, DSpace, Digital Commons or OJS, please configure it to export bibliographic data in HTML "<meta>" tags. Google Scholar supports Highwire Press tags (e.g., citation_title), Eprints tags (e.g., eprints.title), BE Press tags (e.g., bepress_citation_title), and PRISM tags (e.g., prism.title). Use Dublin Core tags (e.g., DC.title) as a last resort - they work poorly for journal papers because Dublin Core doesn't have unambiguous fields for journal title, volume, issue, and page numbers. To check that these tags are present, visit several abstracts and view their HTML source.

The title tag, e.g., citation_title or DC.title, must contain the title of the paper. Don't use it for the title of the journal or a book in which the paper was published, or for the name of your repository. This tag is required for inclusion in Google Scholar.

The author tag, e.g., citation_author or DC.creator, must contain the authors (and only the actual authors) of the paper. Don't use it for the author of the website or for contributors other than authors, e.g., thesis advisors. Author names can be listed either as "Smith, John" or as "John Smith". Put each author name in a separate tag and omit all affiliations, degrees, certifications, etc., from this field. At least one author tag is required for inclusion in Google Scholar.

The publication date tag, e.g., citation_publication_date or DC.issued, must contain the date of publication, i.e., the date that would normally be cited in references to this paper from other papers. Don't use it for the date of entry into the repository - that should go into citation_online_date instead. Provide full dates in the "2010/5/12" format if available; or a year alone otherwise. This tag is required for inclusion in Google Scholar.

For journal and conference papers, provide the remaining bibliographic citation data in the following tags: citation_journal_title or citation_conference_title, citation_issn, citation_isbn, citation_volume, citation_issue, citation_firstpage, and citation_lastpage. Dublin Core equivalents are DC.relation.ispartof for journal and conference titles and the non-standard tags DC.citation.volume, DC.citation.issue, DC.citation.spage (start page), and DC.citation.epage (end page) for the remaining fields. Regardless of the scheme chosen, these fields must contain sufficient information to identify a reference to this paper from another document, which is normally all of: (a) journal or conference name, (b) volume and issue numbers, if applicable, and (c) the number of the first page of the paper in the volume (or issue) in question.

For theses, dissertations, and technical reports, provide the remaining bibliographic citation data in the following tags: citation_dissertation_institution, citation_technical_report_institution or DC.publisher for the name of the institution and citation_technical_report_number for the number of the technical report. As with journal and conference papers, you need to provide sufficient information to recognize a formal citation to this document from another article.

For all document types, the guiding principle is to present your article as it would normally be cited in the "References" section of another paper. E.g., citations to technical reports normally include their assigned numbers, so the number of the report should be present in some appropriate field. Likewise, the name of the journal should be written as "Transactions on Magic Realism" or "Trans. Mag. Real.", not as "Magic Realism, Transactions on" or "T12". Omission or unusual presentation of key bibliographic fields can lead to mis-identification of your articles.

All tag values are HTML attributes, so you must escape special characters appropriately. E.g., <meta name="citation_title" content=""Andar com meus sapatos" - uma análise crítica">. There's no need to escape characters that are written directly in your webpage's character encoding, such as Latin diacritics on a page in ISO-8859-1. However, you must still escape the quotes and the angle brackets.

The "<meta>" tags normally apply only to the exact page on which they're provided. If this page shows only the abstract of the paper and you have the full text in a separate file, e.g., in the PDF format, please specify the locations of all full text versions using citation_pdf_url or DC.identifier tags. The content of the tag is the absolute URL of the PDF file; for security reasons, it must refer to a file in the same subdirectory as the HTML abstract.

Failure to link the alternate versions together could result in the incorrect indexing of the PDF files, because these files would be processed as separate documents without the information contained in the meta tags.

Keep in mind that, regardless of the meta-tag scheme chosen, you need to provide at least three fields: (1) the title of the article, (2) the full name of at least the first author, and (3) the year of publication. Pages that don't provide any one of these three fields will be processed as if they had no meta tags at all. Likewise, all PDF files will be processed as if they had no meta tags at all, unless they're linked from the corresponding HTML abstracts using citation_pdf_url or DC.identifier tags. It works best to provide the meta-tags for all versions of your paper, not just for one of the versions.

2.a. Indexing of content without the meta-tags

If it's not practical for you to implement the HTML "<meta>" tags, e.g., if your papers are only available in the PDF format, then the document needs to be visually laid out according to the following conventions.

The title of the paper must be the largest chunk of text on top of the page. Either use font size of at least 24 pt. in PDF, or place the title inside an "<h1>" or an "<h2>" tag in HTML, or use a CSS class named "citation_title". Please use the same font for the entire title. Make sure that all other text on the page, in particular the name of the repository or the journal, is set in a smaller font than the title of the paper - otherwise, this other, larger, text may be incorrectly interpreted as the title of the paper.

The authors of the paper must be listed right before or right after the title, in a slightly smaller font that is still larger than normal text. Either use a 16-23 pt. font in PDF, or place the authors inside an "<h3>" tag in HTML, or wrap them in a CSS class named "citation_author". Please use the same font for all author names. Make sure the names of the repository and the journal, as well as the text of the section headings, are set in a smaller font than the authors of the paper - otherwise, this other, larger, text may be incorrectly interpreted as the authors. Use "Sentence case" as opposed to "Title Case" for section headings et. al., to avoid confusion with author names. Separate multiple author names with commas or semicolons and omit their affiliations, degrees, and certifications from the author line. Use an explicit format such as "by John Smith" or "Author: John Smith", if appropriate.

Include a bibliographic citation to a published version of the paper on a line by itself, and place it inside the header or the footer of the first page in the PDF file, or next to the title and the authors in HTML. Use an explicit citation format, e.g.: "J. Biol. Chem., vol. 234, no. 8, pp. 1971-1975, August 1959". If the paper is unpublished, include the full date of its present version on a line by itself, e.g., "August 12, 2009".

Avoid use of Type 3 fonts in PDF files, because they're often generated with missing or incorrect font size and character encoding information, which makes it difficult for our parser software to extract the bibliographic data. You can check the types of the fonts under the File -> Properties... menu in Adobe Acrobat Reader. If you're using LaTeX, consider switching to Type 1 fonts, e.g., \usepackage{times}, \usepackage{helvet}, or \usepackage{palatino}.

Please understand that it's not possible for our automated parsers to correctly identify bibliographic data in such loosely defined formats with 100% accuracy; and that failure to correctly identify certain fields can lead to exclusion of your papers from Google Scholar. If you're not satisfied with the accuracy of your Google Scholar results, you need to create HTML pages with abstracts and add the "<meta>" tags to them, as described above.

3. Marking the references

Mark the section of the paper that contains references to other works with a standard heading, such as "References" or "Bibliography", on a line just by itself. Individual references inside this section should be either numbered "1. - 2. - 3." or "[1] - [2] - [3]" in PDF, or put inside an "<ol>" list in HTML. The text of each reference must be a formal bibliographic citation in a commonly used format, without free-form commentary .

Please understand that the references are identified automatically by the parser software; they're not entered or corrected by human operators. While we try to support the most common reference formats, it is not possible to guarantee that all references are identified correctly; and incorrect identification of references could lead to exclusion of your papers from Google Scholar or to low ranking of your papers in the search results.

To check if a particular paper is included in Google Scholar, search Google Scholar for its title. To check the coverage of your website in Google Scholar, search for titles of several dozen papers and see if these papers are included. If you can't find many of the papers in Google Scholar, there's probably a problem with the indexing of your website; please read the troubleshooting tips below.

Keep in mind that changes that you make on your website will usually not be reflected in Google Scholar search results for some time. New papers are normally added several times a week; however, updates of papers that are already included usually take 6-9 months. Updates of papers on very large websites may take several years, because to update a site, we need to recrawl it - the time it takes to recrawl a large site is usually limited by the speed at which the target website is able to deliver content to the search robots.