Essay on Cancer for Students and Children

500+ words essay on cancer.

Cancer might just be one of the most feared and dreaded diseases. Globally, cancer is responsible for the death of nearly 9.5 million people in 2018. It is the second leading cause of death as per the world health organization. As per studies, in India, we see 1300 deaths due to cancer every day. These statistics are truly astonishing and scary. In the recent few decades, the number of cancer has been increasingly on the rise. So let us take a look at the meaning, causes, and types of cancer in this essay on cancer.

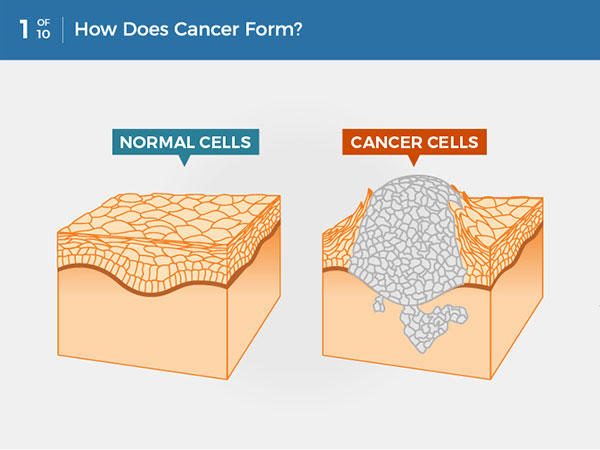

Cancer comes in many forms and types. Cancer is the collective name given to the disease where certain cells of the person’s body start dividing continuously, refusing to stop. These extra cells form when none are needed and they spread into the surrounding tissues and can even form malignant tumors. Cells may break away from such tumors and go and form tumors in other places of the patient’s body.

Types of Cancers

As we know, cancer can actually affect any part or organ of the human body. We all have come across various types of cancer – lung, blood, pancreas, stomach, skin, and so many others. Biologically, however, cancer can be divided into five types specifically – carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, lymphoma, leukemia.

Among these, carcinomas are the most diagnosed type. These cancers originate in organs or glands such as lungs, stomach, pancreas, breast, etc. Leukemia is the cancer of the blood, and this does not form any tumors. Sarcomas start in the muscles, bones, tissues or other connective tissues of the body. Lymphomas are the cancer of the white blood cells, i.e. the lymphocytes. And finally, melanoma is when cancer arises in the pigment of the skin.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Causes of Cancer

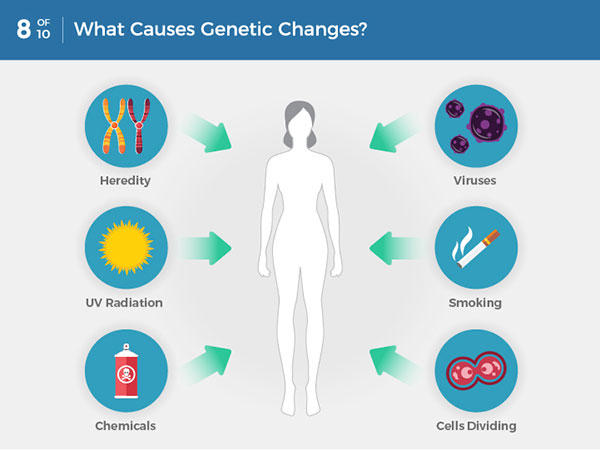

In most cases, we can never attribute the cause of any cancer to one single factor. The main thing that causes cancer is a substance we know as carcinogens. But how these develop or enters a person’s body will depend on many factors. We can divide the main factors into the following types – biological factors, physical factors, and lifestyle-related factors.

Biological factors involve internal factors such as age, gender, genes, hereditary factors, blood type, skin type, etc. Physical factors refer to environmental exposure of any king to say X-rays, gamma rays, etc. Ad finally lifestyle-related factors refer to substances that introduced carcinogens into our body. These include tobacco, UV radiation, alcohol. smoke, etc. Next, in this essay on cancer lets learn about how we can treat cancer.

Treatment of Cancer

Early diagnosis and immediate medical care in cancer are of utmost importance. When diagnosed in the early stages, then the treatment becomes easier and has more chances of success. The three most common treatment plans are either surgery, radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

If there is a benign tumor, then surgery is performed to remove the mass from the body, hence removing cancer from the body. In radiation therapy, we use radiation (rays) to specially target and kill the cancer cells. Chemotherapy is similar, where we inject the patient with drugs that target and kill the cancer cells. All treatment plans, however, have various side-effects. And aftercare is one of the most important aspects of cancer treatment.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

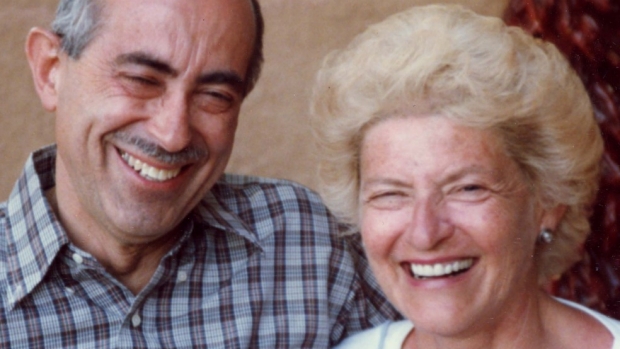

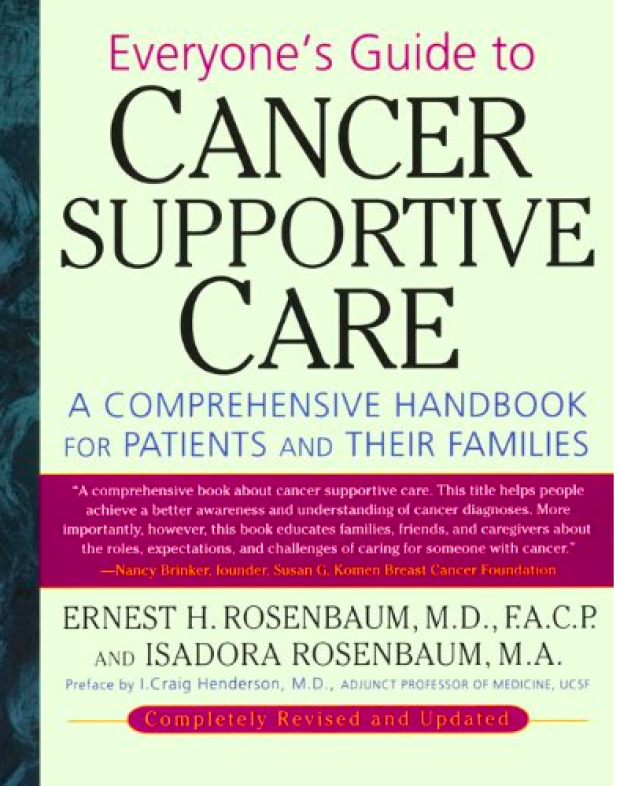

Ernest and Isadora Rosenbaum Library

The Will to Live

Ernest H. Rosenbaum, M.D. Isadora R. Rosenbaum, M.A.

As medical professionals, we have always been fascinated by the power of the will to live. Like all creatures in the animal world, human beings have a fierce instinct for survival. The will to live is a force within all of us to fight for survival when our lives are threatened by a disease such as cancer. Yet this force is stronger in some people than in others.

Many physicians have seen how two patients of similar ages and with the same diagnosis, degree of illness, and treatment program experience vastly different results.

Sometimes the biology of a cancer will dictate the course of events regardless of the patient’s attitude and fighting spirit. These events are often beyond our control. But patients with positive attitudes are better able to cope with disease-related problems and may respond better to therapy. Many physicians have seen how two patients of similar ages and with the same diagnosis, degree of illness, and treatment program experience vastly different results. One of the few apparent differences is that one patient is pessimistic and the other optimistic.

We have known for over 2,000 years— from the writings of Plato and Galen— that there is a direct correlation between the mind, the body, and one’s health. “The cure of many diseases is unknown to physicians,” Plato concluded, “because they are ignorant of the whole. For the part can never be well unless the whole is well.”

Recently there has been a shift in health care toward recognizing this wisdom, namely that the psychological and the physical elements of a body are not separate, isolated, and unrelated, but are vitally linked elements of a total system. Health is increasingly being recognized as a balance of many inputs, including physical and environmental factors, emotional and psychological states, and nutritional habits and exercise patterns.

Researchers are now experimenting with methods of actively enlisting the mind in the body’s combat with cancer, using techniques such as meditation, biofeedback, and visualization (creating in the mind positive images about what is occurring in the body). Some doctors and psychologists now believe that the proper attitude may even have a direct effect on cell function and consequently may be used to arrest, if not cure, cancer. This new field of scientific study, called psychoneuroimmunology, focuses on the effect that mental and emotional activity have on physical well-being, indicating that patients can play a much larger role in their recovery.

It will be many years before we know whether it is possible for the mind to control the immune defense system. Experiments with biofeedback and visualization are helpful in that they encourage positive thinking and provide relaxation, thereby increasing the will to live. But they can also be damaging if a patient puts all of his or her faith in them and ignores conventional therapy.

The Power of the Mind

The mind’s role in causing and curing disease has been debated endlessly. Speculation abounds, particularly in the case of cancer. But no studies have proven in a scientifically valid way that a person can control the course of his or her cancer with the mind, although patients often believe otherwise. There are many individual cases that attest to the power of positive attitudes and emotions. One patient with high-risk cancer had a mastectomy at age twentynine. At thirty-one, she had advanced Stage IV cancer with widespread massive liver and bone involvement and, subsequently, extensive lung metastases. She also had an amazingly strong will to live.

“I would get out of bed every morning as if nothing was wrong,” she once said. “I may have known I was going to have to face things and could feel sick during the day, but I never got out of bed that way. There was a lot I was fighting for. I had a three-year-old child, a wonderful life, and a magical love affair with my husband.” Thirty years later, she is still alive, still on chemotherapy, and still living an active life.

We often ask our patients to explain how they are able to transcend their problems. We have found that however diverse they are in ethnic or cultural background, age, educational level, or type of illness, they have all gone through a similar process of psychological recovery.

We often ask our patients to explain how they are able to transcend their problems. We have found that however diverse they are in ethnic or cultural background, age, educational level, or type of illness, they have all gone through a similar process of psychological recovery. They all consciously made a “decision to live.” After an initial period of feeling devastated, they simply decided to assess their new reality and make the most of each day.

Their “will to live” means that they really want to live, whether or not they’re afraid to die. They want to enjoy life, they want to get more out of life, they believe that their life is not over, and they’re willing to do whatever they can to squeeze more out of it.

The threat of death often renews our appreciation of the importance of life, love, friendship, and all there is to enjoy. We open up to new possibilities and begin taking risks we didn’t have the courage to take before. Many patients say that facing the uncertainties of living with an illness makes life more meaningful. The smallest pleasures are intensified and much of the hypocrisy in life is eliminated. When bitterness and anger begin to dissipate, there is still a capacity for joy.

One patient wrote, “I love living, I love nature. Being outdoors, feeling the sun on my skin or the wind blowing against my body, hearing birds sing, breathing in the spray of the ocean. I never lose hope that I may somehow stumble upon or be graced with a victory against this disease.”

Strengthening Your Will to Live

Unfortunately, and quite understandably, many patients react to the diagnosis of cancer in the same way that people in primitive cultures react to the imposition of a curse or spell: as a sentence to a ghastly death. This phenomenon, known as “bone pointing,” results in a paralytic fear that causes the victim to simply withdraw from the world and await the inevitable end. In modern medical practice, a similar phenomenon may occur when, out of ignorance or superstition, a patient believes the diagnosis of cancer to be a death sentence. However, the phenomenon of self-willed death is only effective if the person believes in the power of the curse.

In the treatment of cancer, we’ve seen patients fail on their first course of chemotherapy, fail again on the second and third treatments, then—with more advanced disease—a fourth treatment is highly successful.

In all things, you have to take a risk if you want to win, to get a remission or recover with the best quality of life. Just the willingness to take a risk seems to generate hope and a positive atmosphere in which the components of the will to live are enhanced. There are many other ways of strengthening the will to live.

Getting Involved The best thing a patient can do to strengthen the will to live is to get involved as an active participant in combating his or her disease. When patients approach their disease in an aggressive fighting posture, they are no longer helpless victims. Instead, they become active partners with their medical support team in the fight for improvement, remission, or cure. This partnership must be based on honesty, open communication, shared responsibility, and education about the nature of the disease, therapy options, and rehabilitation. The result of this partnership is an increased ability to cope that, in turn, nurtures the will to live.

Helping and Sharing with Others – A way to strengthen this partnership is to extend the relationship to others. The emotional experience of sharing and enjoying your family and partnerships supports your love for life and your will to survive.

As you make the transition from helpless victim to activist, one of the most important realizations is that you have everything to do with how others perceive you and treat you. If you can accept your condition and hold self-pity at bay, others won’t feel sorry for you. If you can discuss your disease and medical therapy in a matter-of-fact manner, they’ll respond in kind without fear or awkwardness. You are in charge. You can subtly and gently put your family, friends, and coworkers at ease by being frank about what you want to talk about or not talk about and by being explicit about whether and when you want their help.

Sharing your life with others and receiving aid or support from friends and family will improve your ability to cope and help you fight for your life. A person who is lonely or alone often feels like a helpless victim. There is a need to share your own problems, but helping others find solutions to or cope better with the problems of daily living gives strength to both the giver and the receiver. There are few more satisfying experiences in life than helping a person in need.

Patients can also take part in psychological support programs, either through private counseling or through group therapy. Sharing frustrations with others in similar circumstances often relieves the sense of isolation, terror, and despair cancer patients often feel.

Those who must live with cancer can live to the maximum of their capacity by

- living in the present, not the past,

- setting realistic goals and being willing to compromise,

- regaining control of their lives and maintaining a sense of independence and self-esteem,

- trying to resolve negative emotions and depression by actively doing things to help themselves and others, and

- following an improved diet and exercising regularly.

Nurturing Hope

Of all the ingredients in the will to live, hope is the most vital. Hope is the emotional and mental state that motivates you to keep on living, to accomplish things, and to succeed. A person who lacks hope can give up on life and lose the will to live. Without hope, there is little to live for. But with hope, a positive attitude can be maintained, determination strengthened, coping skills sharpened, and love and support more freely given and received.

Even if a diagnosis is such that the future seems limited, hope must be maintained. Hope is what people have to live on. Take away hope, and you take away a chance for the future, which leads to depression. When people fall to that low emotional state, their bodies simply turn off.

Hope can be maintained as long as there is even a remote chance for survival. It can be kindled and nurtured by minor improvements or a remission and maintained when crises or reversals occur. There may be times when you will feel exhausted and drained by never-ending problems and feel ready to give up the struggle to survive. All too often it seems easier to give up than to keep on fighting. Frustrations and despair can sometimes feel overwhelming. Determination or dogged persistence is needed to accomplish the difficult task of fighting for your health.

The experience of cancer not only is destructive in a physical way, but can be a major deterrent to your fighting attitude and will to live. But even during the roughest times, there are often untapped reserves of physical and emotional strength to call upon to help you survive one more day. These reserves can add meaning to your life as well as serve as a lighthouse that leads you to a safe haven during a turbulent storm.

Hope has different meanings for each person. It is a component of a positive attitude and acceptance of our fate in life. We use our strengths to gain success to live life to the fullest. Circumstances often limit our hopes of happiness, cure, remission, or increased longevity. We also live with fears of poverty, pain, a bad death, or other unhappy experiences.

You may worry so much that you lose sight of the possibility of recovery and lose your sense of optimism. On the other hand, you may become so hopeful and confident that you lose sight of reality. Your main challenge is balancing your worry and your hope.

Hope is nourished by the way we live our lives. Achieving the best quality of life requires settling old problems, quarrels, and family strife as well as completing current tasks. Problems that have not been resolved need to have completion. New tasks should be undertaken. If the future seems limited, you can achieve the satisfaction of knowing that you have taken care of your affairs and not left the burden to your family or others. By doing so, you can achieve peace of mind, which will also help strengthen your will to live. With each passing day, try to complete what you can and have that satisfaction that you have done your best.

Be bold, be venturesome, and be willing to experience each day to the fullest to enhance your enjoyment of life. As long as fear, suffering, and pain can be controlled, life can be lived fully until the last breath. Each of us has the capacity to live each day a little better, but we need to focus on both purpose and goals and set into action a realistic daily plan—often altered many times—to help us achieve them. These resources are the foundation of the will to live. Only by using the power of the will to live—nourished by hope—can we achieve the sublime feelings of knowing and experiencing the wonders of life and appreciate its meanings through vital living.

Related Articles

The Role of the Clergy

Religion and Spirituality

The Art of Forgiveness

Coping with Cancer

Coping with Depression

When Your Spouse Has Cancer

The Waiting Process

Patient Stories

One Patients Way of Coping

Feeling Right When Things Go Wrong

I Live a Disease-Threatening Life

The Scent of an Orange

In Touch with My Dream

I Don't Have Time Not to Live

A Cup of Breath

One in a Million

Expedition Inspiration

To Call Forth That Spark

Ernest h. rosenbaum, m.d..

Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, Comprehensive Cancer Center; Adjunct Clinical Professor, Department of Medicine, Stanford University Medical Center; Director, Stanford Cancer Supportive Care Programs National/International, Stanford Complementary Medicine Clinic, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California. More

Ernest H. Rosenbaum’s career has included a fellowship at the Blood Research Laboratory of Tufts University School of Medicine (New England Center Hospital) and MIT. He teaches at the University of California, San Francisco, Comprehensive Cancer Center, was the cofounder of the Northern California Academy of Clinical Oncology, and founded the Better Health Foundation and the Cancer Supportive Care Program at the Stanford Complementary Medicine Clinic, Stanford University Medical Center.

His passionate interest in clinical research and developing ways to improve patient care and communication with patients and colleagues has resulted in over fifty articles on cancer and hematology in various medical journals. He has also participated in many radio and television programs and frequently lectures to medical and public groups.

He has written numerous books, including Living with Cancer: A Home Care Training Program for Cancer Patients; Decisions for Life: You Can Live Ten Years Longer with Better Health; Cancer Supportive Care: A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Patients and Their Families; Nutrition for the Cancer Patient; Everyone’s Guide to Cancer Therapy; and Everyone’s Guide to Cancer Survivorship. For Everyone’s Guide to Cancer Therapy, Ernest Rosenbaum, M.D., Malin Dollinger, M.D., and Greg Cable received and Honorable Mention in 1991 from the American Medical Writers Association for Excellence in Medical Publications. Ernest and Isadora Rosenbaum received the same award in 1982 for their book, A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Patients and Their Families.

Isadora Rosenbaum, M.A.

Isadora Rosenbaum is a medical assistant who worked in immunology research and is currently at an oncology practice at the UCSF Comprehensive Cancer Center offering advice and psychosocial support. She coauthored Nutrition for the Cancer Patient and The Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Patients and Their Families. She has written chapters in Everyone’s Guide to Cancer Therapy, Living with Cancer, and You Can Live 10 Years Longer with Better Health.

The Unique Hell of Getting Cancer as a Young Adult

W hen I got diagnosed with Stage 3b Hodgkin Lymphoma at age 32, it was almost impossible to process. Without a family history or lifestyle risk factors that put cancer on my radar, I stared at the emergency room doctor in utter disbelief when he said the CT scan of my swollen lymph node showed what appeared to be cancer—and lots of it. A few days away from a bucket list trip to Japan, I’d only gone to the emergency room because the antibiotics CityMD prescribed to me when I was sick weren’t working.I didn’t want to be sick in a foreign country. So when the doctor told me of my diagnosis, the only question I could conjure was: “So Tokyo is a no-go?”

Around the world, cancer rates in people under 50 are surging, with a recent study in BMJ Oncology showing that new cases for young adults have risen 79% overall over the past three decades. In the U.S. alone, new cancer diagnoses in people under 50 hit 3.26 million, with the most common types being breast, windpipe, lung, bowel, and stomach. A new feature in the Wall Street Journal highlights the mad dash among doctors and researchers to determine what’s causing this troubling rise. Strangely, overall cancer rates in the U.S. have dropped over the past three decades, while young people—particularly with colorectal cancers—are increasingly diagnosed at late stages. “We need to make it easier for adolescents and young adults to participate in clinical trials to improve outcomes and study the factors contributing to earlier onset cancers so we can develop new cures,” says Julia Glade Bender, MD, co-lead of the Stuart Center for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancers at Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York City (where I am currently a patient.)

Doctors suspect that lifestyle factors and environmental elements, from microplastics to ultra-processed foods, could be to blame. But many adults in their 20s and 30s, such as myself, were otherwise healthy before their diagnoses. It felt like all those years of forcing myself to run, eat high-fiber foods, and choke down kombucha were for nothing.

Cancer is hell at any age, but the challenges facing young adults are especially steep, as the disease disrupts a formative period for building a career, family, and even healthy self-esteem, from body image to gender identity. It’s critical that our approach to treating and supporting these patients reflects the severity of this disruption. In recent years, a growing number of cancer hospitals have developed young adult-specific programming like support groups, information sessions on dating and sexual health, and even mobile apps to help counter social alienation. But there is still a long way to go.

Read more: Why I Stopped Being A “Good” Cancer Patient

Shockingly enough, canceling my trip to Japan was the least of my worries. Beyond the excruciating physical side effects of high-dose chemotherapy and a number of life-threatening complications, cancer pulverized my self-esteem into nothingness, as I watched peers get married and promoted from my bed. Thankfully, after switching to a new hospital, I found support groups that connected me with a community of peers who got it, as well as social workers who work exclusively with young adults and thus recognized many of my biggest challenges, like social isolation, financial strain, the dating nightmare, and hating my bald head.

Perhaps the biggest reason I resented cancer was for disrupting a milestone I’d worked for my whole life: a book launch. (My diagnosis came two months before my first book was published.) Young adulthood is meant to be littered with these kinds of professional and personal benchmarks, many of which are hard enough to accomplish without tumors; dating, for instance, is impossible for me even as a healthy person. Now I have to re-enter the pool older, weaker, and more traumatized?

“Young adult patients may be trying to assert independence from parents, establish a career or intimate relationship, or even be parents themselves,” says Bender. “Most will be naïve to the medical system or a serious health condition.” And so they require flexible, creative clinicians who can help navigate them “to and through the best available therapy and back to their lives, inevitably ‘changed’ but intact.” Not only do these patients need specialized psychosocial support, but research initiatives should prioritize developing treatments that minimize long-term toxicities.

Given that many young patients haven’t yet built financial stability and are often in some form of debt, organizations like Young Adults Survivors United (YASU) have emerged to support young adult survivors and patients through the financial overwhelm. Stephanie Samolovitch, MSW and founder of YASU, says that there’s still an enormous need for resources supporting young adult cancer patients and survivors.

“Cancer causes a young adult to be dependent again, whether it’s moving back in with parents, getting rides to appointments, or asking for financial help,” says Samolovitch, who was diagnosed with leukemia in 2005, two weeks before her 20th birthday. “Young adults never expect to apply for Medicaid or Social Security Disability during our twenties or thirties, yet cancer doesn't give us a choice sometimes. That causes stress, shame, depression, and anxiety when trying to navigate the healthcare system.”

Read more: How to Create an Action Plan After a Cancer Diagnosis

When Ana Calderone, a 33-year-old magazine editor, was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer at 30, the most challenging part of getting diagnosed so young was “everything.”

“I felt like it set my whole life back, which sounds stupid because I was literally fighting for my life,” she says. “Who cares if I had to delay my wedding a year because I was still getting radiation treatment? But it was really hard at the time. Everything was delayed, and still is.”

During chemo, Calderone’s doctors gave her a shot that she still receives to try and preserve her ovaries, and she’s been able to try IVF twice. She says she had to proactively advocate for those things with her care team. While Calderone is currently cancer free, she still must take medication that has further delayed her plans to build a family. “I’m fairly confident I’d have a child by now if I didn’t get cancer. That’s been the most devastating part,” she says. “My oncologist would consider letting me get pregnant in two more years, which would be 4.5 years post-diagnosis, and even that is still a risk.”

For 32-year-old Megan Koehler, whose son was one and a half when she was diagnosed with Hodgkin Lymphoma, the hardest part “was knowing the world continued on while I spent days in bed,” she says. “My coworkers still worked on projects I was supposed to be part of, and the worst was knowing my son was growing up, learning to speak sentences, and just becoming a toddler without me – or so it felt that way.”

She remembers crying for most of his second birthday because she was in bed post chemo, feeling devastated that she didn’t have the energy to spend the day with him. During a 50-plus day hospital stay caused by an adverse reaction to a chemotherapy drug, she would Facetime him and cry when he spoke in sentences, because he wasn’t doing that before she was admitted. While she’s grateful for the support she had from her husband and mother, she felt alienated. “I spoke to a few people my age via social media, but no one in person. My center mostly catered to the older generations, so it was somewhat isolating. I did have a great relationship with a few of the infusion nurses who were around my age.”

While oncologists may be rightly focused on saving patients’ lives, there must be more consideration for quality of life during and after treatment – both physical and mental. “More questions need to be asked about their relationships, fertility options, and any mental health concerns or symptoms,” says Samolovitch. From a research perspective, initiatives must expand to pinpoint not only the reason for the rise of cancer in young adults, but find ways to screen and diagnose earlier.

Towards the beginning of my treatment, before I switched hospitals, my oncologist seemed to treat my concerns about self-esteem and hair loss as trivial compared to the real work of saving my life. At my weakest, I had to advocate repeatedly to get accurate information on cold capping, a process of scalp cooling that can preserve most of your hair during chemotherapy, and I had to beg again and again for a social worker to reach out to me, which took weeks.

It’s a beautiful thing that more young adults with cancer are surviving their illnesses. But that means they’ll have decades of life ahead of them. Providers must do a better job supporting young adult patients through all the collateral damage that comes with cancer and its treatment.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

I’ll Tell You the Secret of Cancer

It’s been almost 20 years since my diagnosis, and I’ve learned quite a bit.

Are you someone who enjoys the unsolicited opinions of strangers and acquaintances? If so, I can’t recommend cancer highly enough. You won’t even have the first pathology report in your hands before the advice comes pouring in. Laugh and the world laughs with you; get cancer and the world can’t shut its trap.

Stop eating sugar; keep up your weight with milkshakes. Listen to a recent story on NPR; do not read a recent story in Time magazine. Exercise—but not too vigorously; exercise— hard , like Lance Armstrong. Join a support group, make a collage, make a collage in a support group, collage the shit out of your cancer. Do you live near a freeway or drink tap water or eat food microwaved on plastic plates? That’s what caused it. Do you ever think about suing? Do you ever wonder whether, if you’d just let some time pass, the cancer would have gone away on its own?

Before I got cancer, I thought I understood how the world worked, or at least the parts that I needed to know about. But when I got cancer, my body broke down so catastrophically that I stopped trusting what I thought and believed. I felt that I had to listen when people told me what to do, because clearly I didn’t know anything.

Much of the advice was bewildering, and all of it was anxiety-producing. In the end, because so many people contradicted one another, I was able to ignore most of them. But there was one warning I heard from a huge number of people, almost every day, and sometimes two or three times a day: I had to stay positive. People who beat cancer have a great positive attitude . It’s what distinguishes the survivors from the dead.

There are books about how to develop the positive attitude that beats cancer, and meditation tapes to help you visualize your tumors melting away. Friends and acquaintances would send me these books and tapes—and they would send them to my husband, too. We were both anxious and willing to do anything in our control.

But after a terrible diagnosis, a failed surgery, a successful surgery, and the beginning of chemotherapy, I just wasn’t feeling very … up. At the end of another terrible day, my husband would gently ask me to sit in the living room so that I could meditate and think positive thoughts. I was nauseated from the drugs, tired, and terrified that I would leave my little boys without a mother. All I wanted to do was take my Ativan and sleep. But I couldn’t do that. If I didn’t change my attitude, I was going to die.

P eople get diagnosed with cancer in different ways. Some have a family history, and their doctors monitor them for years. Others have symptoms for so long that the eventual diagnosis is more of a terrible confirmation than a shock. And then there are people like me, people who are going about their busy lives when they push open the door of a familiar medical building for a routine appointment and step into an empty elevator shaft.

The afternoon in 2003 that I found out I had aggressive breast cancer, my boys were almost 5. The biggest thing on my mind was getting the mammogram over with early enough that I could pick up some groceries before the babysitter had to go home. I put on the short, pink paper gown and thought about dinner. And then everything started happening really fast. Suddenly there was the need for a second set of films, then a sonogram, then the sharp pinch of a needle. In my last fully conscious moment as the person I once was, I remember asking the doctor if I should have a biopsy. The reason I asked was so that he could look away from the screen, realize that he’d scared me, and reassure me. “No, no,” he would say; “it’s completely benign.” But he didn’t say that. He said, “That’s what we’re doing right now.”

Later I would wonder why the doctor hadn’t asked my permission for the needle biopsy. The answer was that I had already passed through the border station that separates the healthy from the ill. The medical community and I were on new terms.

Read: I thought Stage IV cancer was bad enough

The doctor could see that I was in shock, and he seemed pretty rattled himself. He kept saying that he should call my husband. “You need to prepare yourself,” he said, twice. And once: “It’s aggressive.” But I didn’t want him to call my husband. I wanted to tear off my paper gown and never see that doctor, his office, or even the street where the building was located ever again. I had a mute, animal need to get the hell out of there. The news was so bad, and it kept getting worse. I couldn’t think straight. My little boys were so small. They were my life, and they needed me.

Three weeks later, I was in the infusion center. Ask Google “What is the worst chemotherapy drug?” and the answer is doxorubicin. That’s what I got, as well as some other noxious pharmaceuticals. That oncologist filled me and my fellow patients up with so much poison that the sign on the bathrooms said we had to flush twice to make sure every trace was gone before a healthy person—a nurse, or a family member—could use the toilet. I was not allowed to hug my children for the first 24 hours after treatment, and in the midst of this absolute hell—in the midst of the poison and the crying and the sorrow and the terror—I was supposed to get a really great positive attitude.

The book we were given several copies of, which was first published in 1986 and has been reissued several times since, is titled Love, Medicine and Miracles and was written by a pediatric surgeon named Bernie Siegel. He seems less interested in exceptional scientific advances than in “exceptional patients.” To be exceptional, you have to tell your body that you want to live; you have to say “No way” to any doctor who says you have a fatal illness. You have to become a channel of perfect self-love, and remember that “the simple truth is, happy people generally don’t get sick.” Old angers or disappointments can congeal into cancer. You need to get rid of those emotions, or they will kill you.

In 1989 a Stanford psychiatrist named David Spiegel published a study of women with metastatic breast cancer. He created a support group for half the women, whom he taught self-hypnosis. The other women got no extra social support. The results were remarkable: Spiegel reported that the women in the group survived twice as long as the other women. This study was hugely influential in modern beliefs about meditation and cancer survival. It showed up in the books my husband read to me, which were filled with other stories of miraculous healings, of patients defying the odds though their own emotional work. But I was so far behind. From the beginning I couldn’t stop crying. I began to think I was hopeless and would never survive.

I needed help, and I remembered a woman my husband and I had talked to in the first week after my diagnosis. Both of us had found in those conversations our only experience of calm, our only reassurance that we were doing the right things. Anne Coscarelli is a clinical psychologist and the founder of the Simms/Mann-UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology , which helps patients and their families cope with the trauma of cancer. We had reached out to her when we were trying to understand my diagnosis. Now I needed her for much more.

For the first half hour in her office, we just talked about how sick I felt and how frightened I was. Then—nervously—I confessed: I wasn’t doing the work of healing myself. I wasn’t being positive.

“Why do you need to be positive?” she asked in a neutral voice.

I thought it should be obvious, but I explained: Because I didn’t want to die!

Coscarelli remained just as neutral and said, “There isn’t a single bit of evidence that having a positive attitude helps heal cancer.”

What? That couldn’t possibly be right. How did she know that?

“They study it all the time,” she said. “It’s not true.”

David Spiegel was never able to replicate his findings about metastatic breast cancer. The American Cancer Society and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health say there’s no evidence that meditation or support groups increase survival rates. They can do all sorts of wonderful things, like reducing stress and allowing you to live in the moment instead of worrying about the next scan. I’ve learned, whenever I start to get scared, to do some yoga-type breathing with my eyes closed until I get bored. If I’m bored, I’m not scared, so then I open my eyes again. But I’m not alive today because of deep breathing.

When I began to understand that attitude doesn’t have anything to do with survival, I felt myself coming up out of deep water. I didn’t cause my cancer by having a bad attitude, and I wasn’t going to cure it by having a good one.

And then Coscarelli told me the whole truth about cancer. If you’re ready, I will tell it to you.

Cancer occurs when a group of cells divide in rapid and abnormal ways. Treatments are successful if they interfere with that process.

That’s it, that’s the whole equation.

Everyone with cancer has a different experience, and different beliefs about what will help. I feel strongly that these beliefs should be respected—including the feelings of those who decide not to have any treatment at all. It’s sadism to learn that someone is dangerously ill and to impose upon her your own set of unproven assumptions, especially ones that blame the patient for getting sick in the first place.

That meeting with Anne Coscarelli took place 18 years ago, and never once since then have I worried that my attitude was going to kill me. I’ve had several recurrences, all of them significant, but I’m still here, typing and drinking a Coke and not feeling super upbeat.

Before I left that meeting, I asked her one last question: Maybe I couldn’t think my way out of cancer, but wasn’t it still important to be as good a person as I could be? Wouldn’t that karma improve my odds a little bit?

Coscarelli told me that, over the years, many wonderful and generous women had come to her clinic, and some of them had died very quickly. Yikes. I had to come clean: Not only was I un-wonderful. I was also kind of a bitch.

God love her, she came through with exactly what I needed to hear: “I’ve seen some of the biggest bitches come in, and they’re still alive.”

And that, my friends, was when I had my very first positive thought. I imagined all those bitches getting healthy, and I said to myself, I think I’m going to beat this thing.

What Is Cancer?

Get email updates from NCI on cancer health information, news, and other topics

Get email updates from NCI

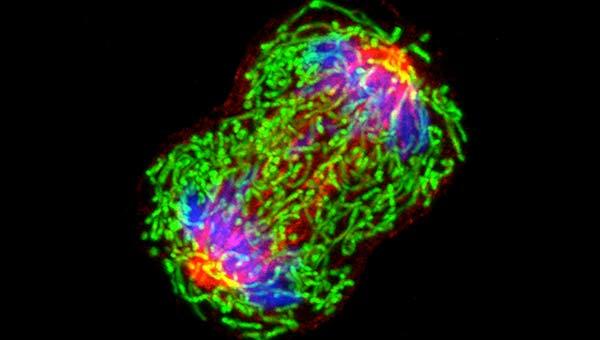

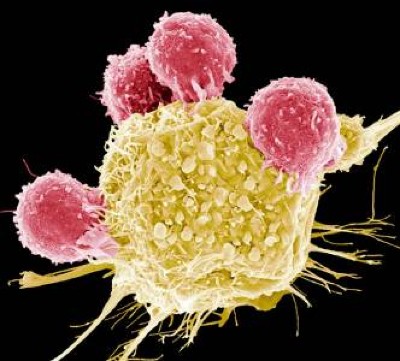

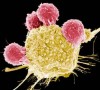

A dividing breast cancer cell.

The Definition of Cancer

Cancer is a disease in which some of the body’s cells grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body.

Cancer can start almost anywhere in the human body, which is made up of trillions of cells. Normally, human cells grow and multiply (through a process called cell division) to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old or become damaged, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes this orderly process breaks down, and abnormal or damaged cells grow and multiply when they shouldn’t. These cells may form tumors, which are lumps of tissue. Tumors can be cancerous or not cancerous ( benign ).

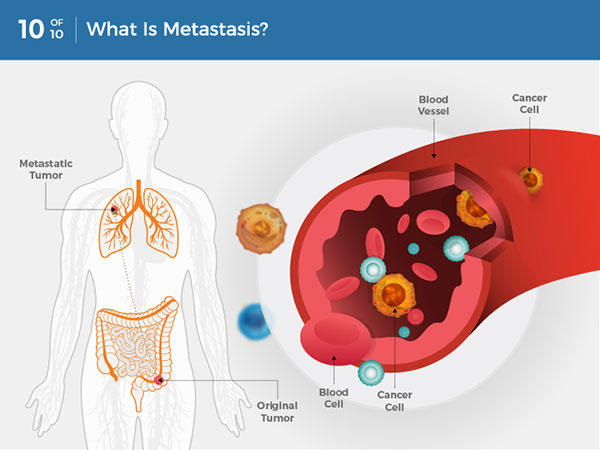

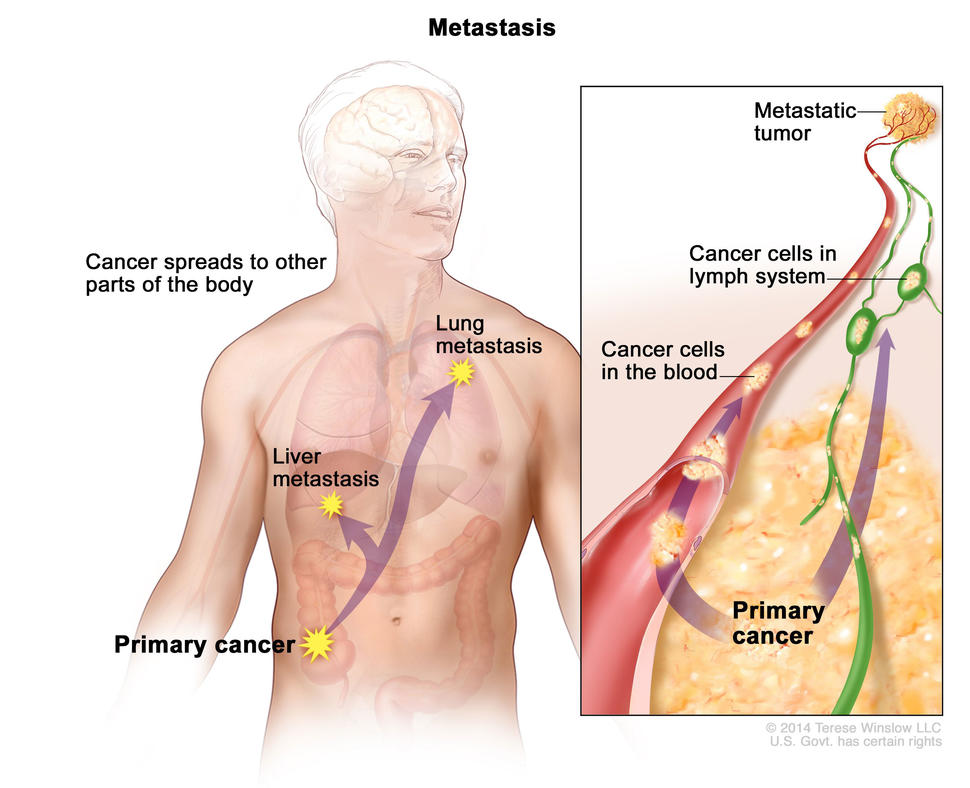

Cancerous tumors spread into, or invade, nearby tissues and can travel to distant places in the body to form new tumors (a process called metastasis ). Cancerous tumors may also be called malignant tumors. Many cancers form solid tumors, but cancers of the blood, such as leukemias , generally do not.

Benign tumors do not spread into, or invade, nearby tissues. When removed, benign tumors usually don’t grow back, whereas cancerous tumors sometimes do. Benign tumors can sometimes be quite large, however. Some can cause serious symptoms or be life threatening, such as benign tumors in the brain.

Differences between Cancer Cells and Normal Cells

Get Answers >

Have questions? Connect with a Cancer Information Specialist for answers.

Cancer cells differ from normal cells in many ways. For instance, cancer cells:

- grow in the absence of signals telling them to grow. Normal cells only grow when they receive such signals.

- ignore signals that normally tell cells to stop dividing or to die (a process known as programmed cell death , or apoptosis ).

- invade into nearby areas and spread to other areas of the body. Normal cells stop growing when they encounter other cells, and most normal cells do not move around the body.

- tell blood vessels to grow toward tumors. These blood vessels supply tumors with oxygen and nutrients and remove waste products from tumors.

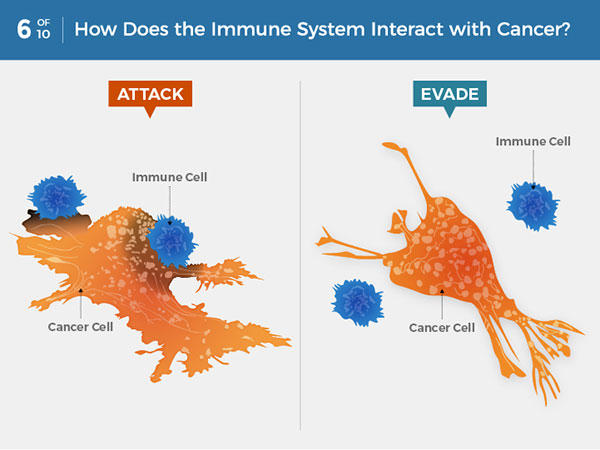

- hide from the immune system . The immune system normally eliminates damaged or abnormal cells.

- trick the immune system into helping cancer cells stay alive and grow. For instance, some cancer cells convince immune cells to protect the tumor instead of attacking it.

- accumulate multiple changes in their chromosomes , such as duplications and deletions of chromosome parts. Some cancer cells have double the normal number of chromosomes.

- rely on different kinds of nutrients than normal cells. In addition, some cancer cells make energy from nutrients in a different way than most normal cells. This lets cancer cells grow more quickly.

Many times, cancer cells rely so heavily on these abnormal behaviors that they can’t survive without them. Researchers have taken advantage of this fact, developing therapies that target the abnormal features of cancer cells. For example, some cancer therapies prevent blood vessels from growing toward tumors , essentially starving the tumor of needed nutrients.

How Does Cancer Develop?

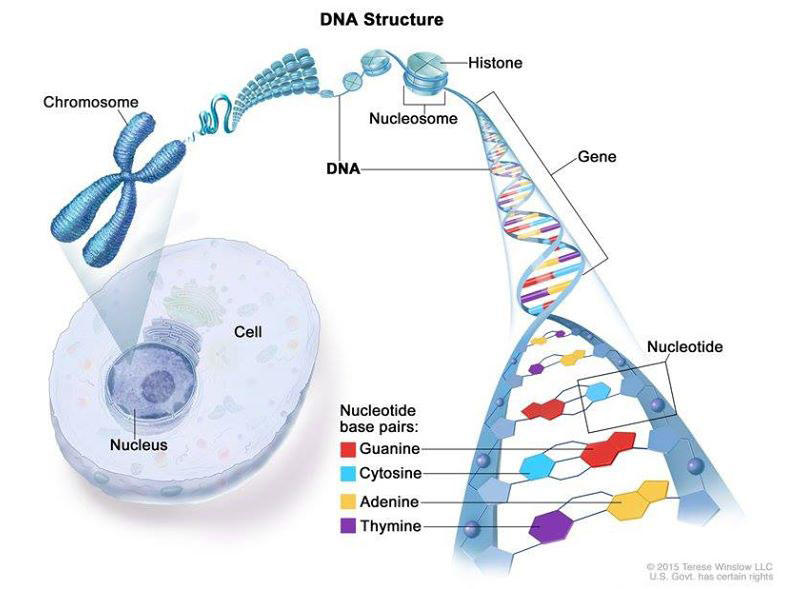

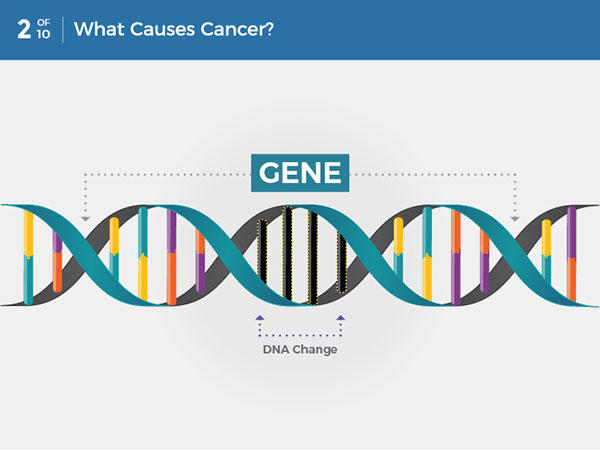

Cancer is caused by certain changes to genes, the basic physical units of inheritance. Genes are arranged in long strands of tightly packed DNA called chromosomes.

Cancer is a genetic disease—that is, it is caused by changes to genes that control the way our cells function, especially how they grow and divide.

Genetic changes that cause cancer can happen because:

- of errors that occur as cells divide.

- of damage to DNA caused by harmful substances in the environment, such as the chemicals in tobacco smoke and ultraviolet rays from the sun. (Our Cancer Causes and Prevention section has more information.)

- they were inherited from our parents.

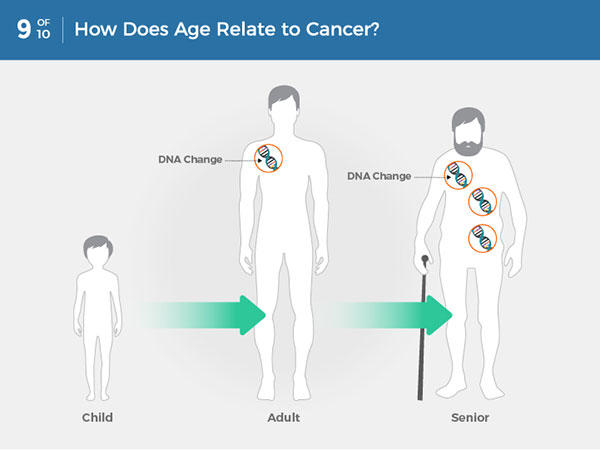

The body normally eliminates cells with damaged DNA before they turn cancerous. But the body’s ability to do so goes down as we age. This is part of the reason why there is a higher risk of cancer later in life.

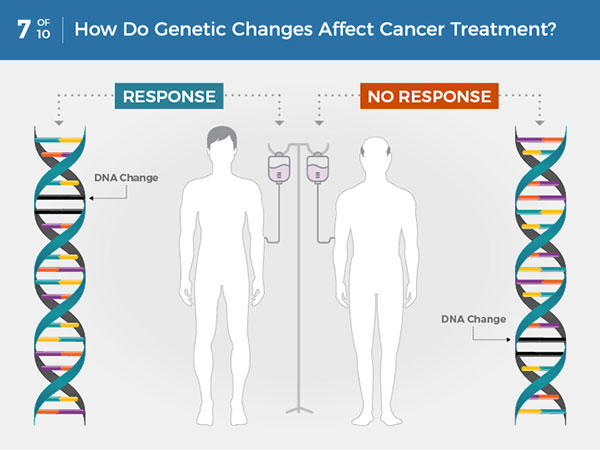

Each person’s cancer has a unique combination of genetic changes. As the cancer continues to grow, additional changes will occur. Even within the same tumor, different cells may have different genetic changes.

Fundamentals of Cancer

Cancer is a disease caused when cells divide uncontrollably and spread into surrounding tissues.

Cancer is caused by changes to DNA. Most cancer-causing DNA changes occur in sections of DNA called genes. These changes are also called genetic changes.

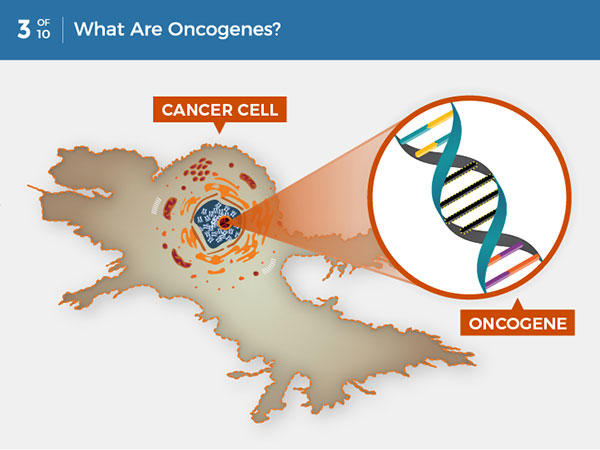

A DNA change can cause genes involved in normal cell growth to become oncogenes. Unlike normal genes, oncogenes cannot be turned off, so they cause uncontrolled cell growth.

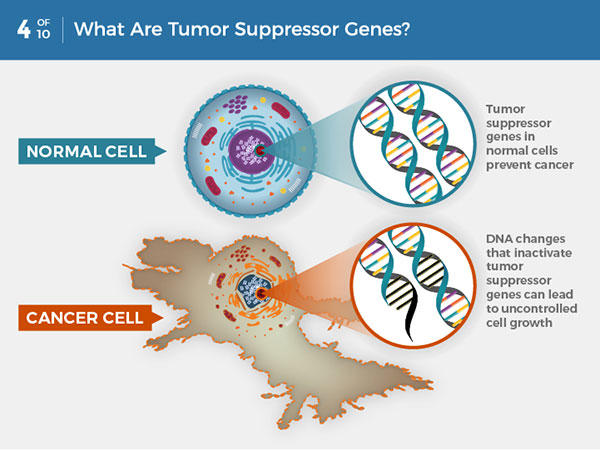

In normal cells, tumor suppressor genes prevent cancer by slowing or stopping cell growth. DNA changes that inactivate tumor suppressor genes can lead to uncontrolled cell growth and cancer.

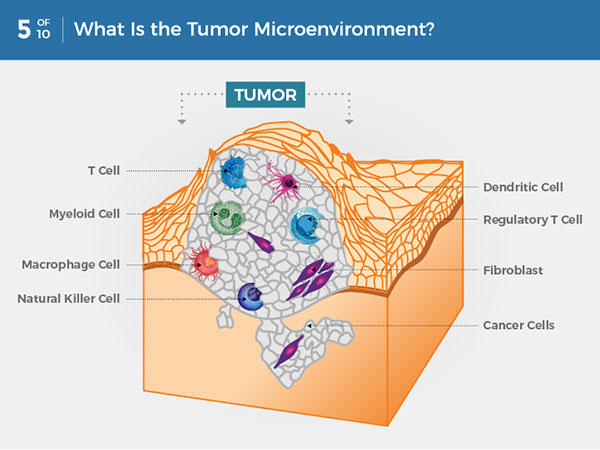

Within a tumor, cancer cells are surrounded by a variety of immune cells, fibroblasts, molecules, and blood vessels—what’s known as the tumor microenvironment. Cancer cells can change the microenvironment, which in turn can affect how cancer grows and spreads.

Immune system cells can detect and attack cancer cells. But some cancer cells can avoid detection or thwart an attack. Some cancer treatments can help the immune system better detect and kill cancer cells.

Each person’s cancer has a unique combination of genetic changes. Specific genetic changes may make a person’s cancer more or less likely to respond to certain treatments.

Genetic changes that cause cancer can be inherited or arise from certain environmental exposures. Genetic changes can also happen because of errors that occur as cells divide.

Most often, cancer-causing genetic changes accumulate slowly as a person ages, leading to a higher risk of cancer later in life.

Cancer cells can break away from the original tumor and travel through the blood or lymph system to distant locations in the body, where they exit the vessels to form additional tumors. This is called metastasis.

Types of Genes that Cause Cancer

The genetic changes that contribute to cancer tend to affect three main types of genes— proto-oncogenes , tumor suppressor genes , and DNA repair genes. These changes are sometimes called “drivers” of cancer.

Proto-oncogenes are involved in normal cell growth and division. However, when these genes are altered in certain ways or are more active than normal, they may become cancer-causing genes (or oncogenes), allowing cells to grow and survive when they should not.

Tumor suppressor genes are also involved in controlling cell growth and division. Cells with certain alterations in tumor suppressor genes may divide in an uncontrolled manner.

DNA repair genes are involved in fixing damaged DNA. Cells with mutations in these genes tend to develop additional mutations in other genes and changes in their chromosomes, such as duplications and deletions of chromosome parts. Together, these mutations may cause the cells to become cancerous.

As scientists have learned more about the molecular changes that lead to cancer, they have found that certain mutations commonly occur in many types of cancer. Now there are many cancer treatments available that target gene mutations found in cancer . A few of these treatments can be used by anyone with a cancer that has the targeted mutation, no matter where the cancer started growing .

When Cancer Spreads

In metastasis, cancer cells break away from where they first formed and form new tumors in other parts of the body.

A cancer that has spread from the place where it first formed to another place in the body is called metastatic cancer. The process by which cancer cells spread to other parts of the body is called metastasis.

Metastatic cancer has the same name and the same type of cancer cells as the original, or primary, cancer. For example, breast cancer that forms a metastatic tumor in the lung is metastatic breast cancer, not lung cancer.

Under a microscope, metastatic cancer cells generally look the same as cells of the original cancer. Moreover, metastatic cancer cells and cells of the original cancer usually have some molecular features in common, such as the presence of specific chromosome changes.

In some cases, treatment may help prolong the lives of people with metastatic cancer. In other cases, the primary goal of treatment for metastatic cancer is to control the growth of the cancer or to relieve symptoms it is causing. Metastatic tumors can cause severe damage to how the body functions, and most people who die of cancer die of metastatic disease.

Tissue Changes that Are Not Cancer

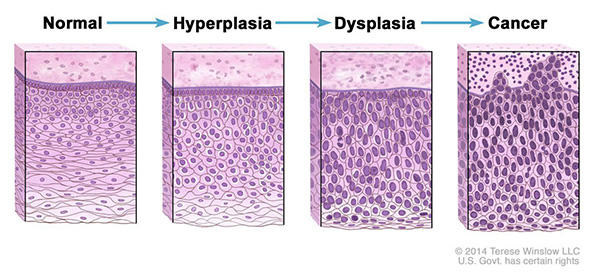

Not every change in the body’s tissues is cancer. Some tissue changes may develop into cancer if they are not treated, however. Here are some examples of tissue changes that are not cancer but, in some cases, are monitored because they could become cancer:

- Hyperplasia occurs when cells within a tissue multiply faster than normal and extra cells build up. However, the cells and the way the tissue is organized still look normal under a microscope. Hyperplasia can be caused by several factors or conditions, including chronic irritation.

- Dysplasia is a more advanced condition than hyperplasia. In dysplasia, there is also a buildup of extra cells. But the cells look abnormal and there are changes in how the tissue is organized. In general, the more abnormal the cells and tissue look, the greater the chance that cancer will form. Some types of dysplasia may need to be monitored or treated, but others do not. An example of dysplasia is an abnormal mole (called a dysplastic nevus ) that forms on the skin. A dysplastic nevus can turn into melanoma, although most do not.

- Carcinoma in situ is an even more advanced condition. Although it is sometimes called stage 0 cancer, it is not cancer because the abnormal cells do not invade nearby tissue the way that cancer cells do. But because some carcinomas in situ may become cancer, they are usually treated.

Normal cells may become cancer cells. Before cancer cells form in tissues of the body, the cells go through abnormal changes called hyperplasia and dysplasia. In hyperplasia, there is an increase in the number of cells in an organ or tissue that appear normal under a microscope. In dysplasia, the cells look abnormal under a microscope but are not cancer. Hyperplasia and dysplasia may or may not become cancer.

Types of Cancer

There are more than 100 types of cancer. Types of cancer are usually named for the organs or tissues where the cancers form. For example, lung cancer starts in the lung, and brain cancer starts in the brain. Cancers also may be described by the type of cell that formed them, such as an epithelial cell or a squamous cell .

You can search NCI’s website for information on specific types of cancer based on the cancer’s location in the body or by using our A to Z List of Cancers . We also have information on childhood cancers and cancers in adolescents and young adults .

Here are some categories of cancers that begin in specific types of cells:

Carcinomas are the most common type of cancer. They are formed by epithelial cells, which are the cells that cover the inside and outside surfaces of the body. There are many types of epithelial cells, which often have a column-like shape when viewed under a microscope.

Carcinomas that begin in different epithelial cell types have specific names:

Adenocarcinoma is a cancer that forms in epithelial cells that produce fluids or mucus. Tissues with this type of epithelial cell are sometimes called glandular tissues. Most cancers of the breast, colon, and prostate are adenocarcinomas.

Basal cell carcinoma is a cancer that begins in the lower or basal (base) layer of the epidermis, which is a person’s outer layer of skin.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a cancer that forms in squamous cells, which are epithelial cells that lie just beneath the outer surface of the skin. Squamous cells also line many other organs, including the stomach, intestines, lungs, bladder, and kidneys. Squamous cells look flat, like fish scales, when viewed under a microscope. Squamous cell carcinomas are sometimes called epidermoid carcinomas.

Transitional cell carcinoma is a cancer that forms in a type of epithelial tissue called transitional epithelium, or urothelium. This tissue, which is made up of many layers of epithelial cells that can get bigger and smaller, is found in the linings of the bladder, ureters, and part of the kidneys (renal pelvis), and a few other organs. Some cancers of the bladder, ureters, and kidneys are transitional cell carcinomas.

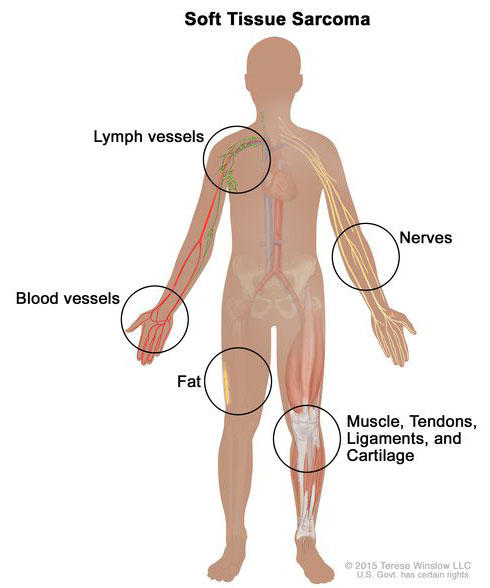

Soft tissue sarcoma forms in soft tissues of the body, including muscle, tendons, fat, blood vessels, lymph vessels, nerves, and tissue around joints.

Sarcomas are cancers that form in bone and soft tissues, including muscle, fat, blood vessels, lymph vessels , and fibrous tissue (such as tendons and ligaments).

Osteosarcoma is the most common cancer of bone. The most common types of soft tissue sarcoma are leiomyosarcoma , Kaposi sarcoma , malignant fibrous histiocytoma , liposarcoma , and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans .

Our page on soft tissue sarcoma has more information.

Cancers that begin in the blood-forming tissue of the bone marrow are called leukemias. These cancers do not form solid tumors. Instead, large numbers of abnormal white blood cells (leukemia cells and leukemic blast cells) build up in the blood and bone marrow, crowding out normal blood cells. The low level of normal blood cells can make it harder for the body to get oxygen to its tissues, control bleeding, or fight infections.

There are four common types of leukemia, which are grouped based on how quickly the disease gets worse (acute or chronic) and on the type of blood cell the cancer starts in (lymphoblastic or myeloid). Acute forms of leukemia grow quickly and chronic forms grow more slowly.

Our page on leukemia has more information.

Lymphoma is cancer that begins in lymphocytes (T cells or B cells). These are disease-fighting white blood cells that are part of the immune system. In lymphoma, abnormal lymphocytes build up in lymph nodes and lymph vessels, as well as in other organs of the body.

There are two main types of lymphoma:

Hodgkin lymphoma – People with this disease have abnormal lymphocytes that are called Reed-Sternberg cells. These cells usually form from B cells.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – This is a large group of cancers that start in lymphocytes. The cancers can grow quickly or slowly and can form from B cells or T cells.

Our page on lymphoma has more information.

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is cancer that begins in plasma cells , another type of immune cell. The abnormal plasma cells, called myeloma cells, build up in the bone marrow and form tumors in bones all through the body. Multiple myeloma is also called plasma cell myeloma and Kahler disease.

Our page on multiple myeloma and other plasma cell neoplasms has more information.

Melanoma is cancer that begins in cells that become melanocytes, which are specialized cells that make melanin (the pigment that gives skin its color). Most melanomas form on the skin, but melanomas can also form in other pigmented tissues, such as the eye.

Our pages on skin cancer and intraocular melanoma have more information.

Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors

There are different types of brain and spinal cord tumors. These tumors are named based on the type of cell in which they formed and where the tumor first formed in the central nervous system. For example, an astrocytic tumor begins in star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes , which help keep nerve cells healthy. Brain tumors can be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer).

Our page on brain and spinal cord tumors has more information.

Other Types of Tumors

Germ cell tumors.

Germ cell tumors are a type of tumor that begins in the cells that give rise to sperm or eggs. These tumors can occur almost anywhere in the body and can be either benign or malignant.

Our page of cancers by body location/system includes a list of germ cell tumors with links to more information.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors form from cells that release hormones into the blood in response to a signal from the nervous system. These tumors, which may make higher-than-normal amounts of hormones, can cause many different symptoms. Neuroendocrine tumors may be benign or malignant.

Our definition of neuroendocrine tumors has more information.

Carcinoid Tumors

Carcinoid tumors are a type of neuroendocrine tumor. They are slow-growing tumors that are usually found in the gastrointestinal system (most often in the rectum and small intestine). Carcinoid tumors may spread to the liver or other sites in the body, and they may secrete substances such as serotonin or prostaglandins, causing carcinoid syndrome .

Our page on gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors has more information.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- National Cancer Awareness Day: Empowering Hope and Health

Coveted as one of the most notorious diseases in the world, cancer has known to be one of the leading causes of death across the world. Cancer in any form is life-threatening and people often shy away from discussing it. However, cancer awareness can be of great benefit to the common people.

Long Essay on Cancer

In this long essay on cancer, we are providing you with cancer meaning, speech on cancer awareness. Go through this cancer essay to get a complete overview of this deadly disease.

In a recent study conducted in 2018, it was found that around 9.5 million people died that year owing to cancer. The World Health Organisation has revealed that cancer is the second leading cause of death across the world. The statistics in India are also no better and as per recent figures about 1300 people die every day owing to cancer of different types. Cancer types and causes have seen a steady increase in the past decade which does not bode well for the world population.

Meaning of Cancer

Before we proceed in this essay on cancer, we must understand cancer's meaning or what exactly is cancer? Cancer is the term given collectively to any and all forms of unregulated cell growth. Normally, the cells inside our body follow a definitive cycle from generation to death. However, in a person suffering from cancer, this cycle is unchecked and hence the cell cycle passes through the checkpoints unhinged and the cells continue to grow.

Types of Cancer

Now, that we have a preliminary understanding of the meaning of cancer, let us proceed to the cancer types or specifications. Cancer types are usually named after the area they affect in the body - usually like skin, lung, pancreas, blood, stomach among the others. However, if classified biologically, there are primarily five types of cancer. These include - leukemia, melanoma, carcinoma, sarcoma, and lymphoma.

Leukemia is the type of cancer that originates in the blood marrow and is a cancer of the blood. In this cancer type, no tumors are formed. Melanoma is regarded as one of the most dangerous types of cancer as in this, the skin coloring pigment or melanin becomes cancerous in nature. Carcinomas are cancers of the various types of glands or organs such as the breasts, stomach, lungs, pancreas, etc. Cancers of the connective tissues such as the bones, muscles, etc are classified as sarcomas. Lymphomas, on the other hand, are cancers of the white blood cells. Among the most diagnosed types of cancers are carcinomas.

Cancer Causes

In the present day living environment, a number of factors are liable to cause cancer. However, in many cases, one single factor cannot be attributed or held responsible for causing cancer in an individual. The substances that are known to be cancer-causing or increasing the risks of cancer are known as carcinogens. Carcinogens can range from anything from pollutants to tobacco to something as simple as processed meats.

The effect of carcinogens, however, on different individuals is different and it is also dependent on a number of factors, be it physical, lifestyle-choice, or biological. The physical factors enabling the effect of carcinogens include exposure to different environmental conditions such as UV rays, X-rays, etc. Cancer among mining workers because of their constant exposure to asbestos and fine silicone dust is common. Biological factors generally include hereditary factors, such as the passing of a mutated BRCA1 or 2 mutations from mother to daughter in case of breast cancer. In addition, they also include factors such as age, gender, blood type, etc. Lifestyle choice refers to habits such as smoking, drinking, radiation exposure, etc, which can act as triggers for carcinogens.

Cancer Treatment

In this segment of our essay on cancer, we will discuss the various types of cancer treatments involved and their applicability. The most commonly applied cancer treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Often, these treatments are given in a combination of one with the other. Surgery is usually performed in the case of benign tumors usually followed by a short cycle of preventive chemotherapy. The treatment of chemotherapy includes a combination of drugs targeted to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy, on the other hand, makes use of radiations to kill cancerous cells. All these treatments are usually known to have side effects, so after-care for cancer survivors is also equally important.

The kind of treatment best suited for a patient is usually determined by the physician. The most important aspect of cancer treatment is early diagnosis and immediate medical intervention. The chances of surviving or beating cancer increase by a paramount value if diagnosed in the early stages.

Cancer Awareness

In India, and many other countries, speaking or discussing cancer is still considered taboo and this perception is in dire need of a change. Always remember cancer awareness is the first step towards cancer prevention. You must come across survivors sharing their journey by means of speech of cancer awareness. It can be of great benefit to know about the disease beforehand as it will keep you wary of any signs or symptoms you might come across and bring the same to the notice of your physician immediately. This will help in preventing or fighting cancer more effectively.

Short Essay on Cancer

To provide you with a grasp on the subject matter, we have provided a short essay on cancer here. Cancer is a disease in which the cells in specified or different parts of the body start dividing continuously. Cancer is usually caused by specific substances that affect several factors in our body. These specific substances are called carcinogens.

Cancer can be caused owing to exposure to pollution, radiation, harmful substances, poor lifestyle choices, etc. Cancer is best treated when detected early. Usually, surgery as well as other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, etc. are used to treat cancer.

Cancer awareness is one of the best means that help in preventing and fighting the disease.

Points to Remember About Cancer

Students are recommended to remember the point of facts so it can be helpful for the students to write an essay with ease. Below are listed a few quick points for the convenience of students who are opting to write an essay on Cancer—

Cancer is a condition in which the cells divide in vast numbers uncontrollably which results in impairment and other damage to the body.

Excessive alcohol consumption, poor nutrition or physical inactivity and, excess weight of the body are some of the causes of Cancer.

Genetic factors can be responsible for the development of cancer.

Some genetic malfunctions occur after birth and factors like exposure to the sun and smoking can increase the risks.

A person can also inherit a certain predisposition for a particular type of cancer.

Chemotherapy is one of the treatments for cancer that targets the dividing cells, it can cure cancer but the side effects can be fatal.

Hormone Therapy is another way for treating cancer where the medication targets certain hormones that interfere with the human body. Hormones are essential in breast cancer and prostate cancer.

Immunotherapy is another way where the medication and treatment target the immune system to boost it.

Personalized medication is one of the newer developments where the treatment is more personalized depending on the person’s body and gene. It is believed that this kind of treatment can cure all types of cancer.

Radiation therapy is the treatment in which a high dose of radiation is given out to kill the cancerous cells. It can be used for shrinking the tumors before the surgery.

Stem cell transplant is essential for blood-related cancer like leukemia and lymphoma. In this treatment, the blood cells are removed that are destroyed by chemotherapy and radiation and then the cells are put back into the body after being developed by the doctors.

Surgery is also a part of the treatment.

Leukemia, Breast cancer, thyroid cancer, melanoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, pancreatic, endometrial, colon, liver, and bladder cancer are the types of cancer that people are diagnosed with every year.

The most common types of cancer are lung cancer and melanoma.

Cancer is classified by doctors in two ways.

First, by the location of the cancerous cells.

And secondly, by the tissues that are affected by it.

Metastasis is a condition where cancerous cells spread to different parts of the body.

Improvements in the rate of cancer have been seen over the years after a significant drop in tobacco consumption and smoking.

The outlook of cancer depends on the severity, type, and location of the cancerous cells.

Some cancer can exhibit symptoms while others don’t so it is always advised to report anything to the medical expert if something is wrong. Cancer doesn’t exhibit many symptoms unless it is in an advanced stage so it is usually better to go for regular checkups.

Tumors can be caused in the brain and spinal that can be cancerous in nature.

Germ cell tumors give rise to sperm and eggs in the body and it can be caused in any part of the body.

Quick Ways to Remember and Write an Essay on Cancer

Do the research

It is essential to write the valid points and present them in this essay as it is based on Cancer. An essay on Cancer must be comprehensive and should ideally contain the context related to this topic hence, it is very important for a student to know about this topic thoroughly in order to write the essay brilliantly.

Analyze the question

A student must understand the intention of the essay and know the terms that are needed to be used. It will clearly form an essay that consists of all the valid points related to cancer.

Remembering the information on Cancer

Cancer as a topic is vast because there are several types of Cancer and writing about all of them is not possible in a condensed essay so it is important to understand and remember the points which are more essential than the others to be mentioned in the essay.

Defining the terms and theories

It is essential for a student to explain the terms being used in the essay. For example, writing the names of the types of Cancer is not enough, it also has to be explained by the student on how it affects and how it may be treated.

Organize a structured essay

Students must write the essay in a coherent manner which must begin with the introduction to cancer, followed by the body of the essay that must contain the types of cancer, treatment, and other information regarding the topic of Cancer. It must be well concluded later to tie everything up neatly.

Cancer is, undoubtedly, one of the most life-shattering diseases. Together, let us make an effort to take on this disease with more care and hope.

FAQs on National Cancer Awareness Day: Empowering Hope and Health

1. Differentiate Between Cancerous and Non-Cancerous Tumours.

The unregulated cell mass inside the body is known as a tumour and can be specified to a particular area or the uninhibited cell growth may spread to the surrounding tissues. Based on this, tumours are majorly classified into two types:

Benign Tumours: This type of tumours are usually regarded as non-cancerous as they are specified to a particular area and can be surgically removed without causing damage to the surrounding tissue.

Malignant Tumours: These tumours, on the other hand, have broken free from their site of origin and spread to other tissues, usually through the bloodstream. These tumours are cancerous in nature and usually require other treatments.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a drug treatment that uses powerful chemicals to kill fast-growing cells in your body.

Chemotherapy is most often used to treat cancer, since cancer cells grow and multiply much more quickly than most cells in the body.

Many different chemotherapy drugs are available. Chemotherapy drugs can be used alone or in combination to treat a wide variety of cancers.

Though chemotherapy is an effective way to treat many types of cancer, chemotherapy treatment also carries a risk of side effects. Some chemotherapy side effects are mild and treatable, while others can cause serious complications.

Products & Services

- Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center

- Sign up for Email: Get Your Free Resource – Coping with Cancer

Why it's done

Chemotherapy is used to kill cancer cells in people with cancer.

There are a variety of settings in which chemotherapy may be used in people with cancer:

- To cure the cancer without other treatments. Chemotherapy can be used as the primary or sole treatment for cancer.

- After other treatments, to kill hidden cancer cells. Chemotherapy can be used after other treatments, such as surgery, to kill any cancer cells that might remain in the body. Doctors call this adjuvant therapy.

- To prepare you for other treatments. Chemotherapy can be used to shrink a tumor so that other treatments, such as radiation and surgery, are possible. Doctors call this neoadjuvant therapy.

- To ease signs and symptoms. Chemotherapy may help relieve signs and symptoms of cancer by killing some of the cancer cells. Doctors call this palliative chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy for conditions other than cancer

Some chemotherapy drugs have proved useful in treating other conditions, such as:

- Bone marrow diseases. Diseases that affect the bone marrow and blood cells may be treated with a bone marrow transplant, also known as a stem cell transplant. Chemotherapy is often used to prepare for a bone marrow transplant.

- Immune system disorders. Lower doses of chemotherapy drugs can help control an overactive immune system in certain diseases, such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Side effects of chemotherapy drugs can be significant. Each drug has different side effects, and not every drug causes every side effect. Ask your doctor about the side effects of the particular drugs you'll receive.

Side effects that occur during chemotherapy treatment

Common side effects of chemotherapy drugs include:

- Loss of appetite

- Mouth sores

- Constipation

- Easy bruising

Many of these side effects can be prevented or treated. Most side effects subside after treatment ends.

Long-lasting and late-developing side effects

Chemotherapy drugs can also cause side effects that don't become evident until months or years after treatment. Late side effects vary depending on the chemotherapy drug but can include:

- Damage to lung tissue

- Heart problems

- Infertility

- Kidney problems

- Nerve damage (peripheral neuropathy)

- Risk of a second cancer

Ask your doctor if you have a risk of any late side effects. Ask what signs and symptoms you should be aware of that may signal a problem.

How you prepare

How you prepare for chemotherapy depends on which drugs you'll receive and how they'll be administered. Your doctor will give you specific instructions to prepare for your chemotherapy treatments. You may need to:

- Have a device surgically inserted before intravenous chemotherapy. If you'll be receiving your chemotherapy intravenously — into a vein — your doctor may recommend a device, such as a catheter, port or pump. The catheter or other device is surgically implanted into a large vein, usually in your chest. Chemotherapy drugs can be given through the device.

- Undergo tests and procedures to make sure your body is ready to receive chemotherapy. Blood tests to check kidney and liver functions and heart tests to check for heart health can determine whether your body is ready to begin chemotherapy. If there's a problem, your doctor may delay your treatment or select a different chemotherapy drug and dosage that's safer for you.

- See your dentist. Your doctor may recommend that a dentist check your teeth for signs of infection. Treating existing infections may reduce the risk of complications during chemotherapy treatment, since some chemotherapy may reduce your body's ability to fight infections.

- Plan ahead for side effects. Ask your doctor what side effects to expect during and after chemotherapy and make appropriate arrangements. For instance, if your chemotherapy treatment will cause infertility, you may wish to consider your options for preserving your sperm or eggs for future use. If your chemotherapy will cause hair loss, consider planning for a head covering.

Make arrangements for help at home and at work. Most chemotherapy treatments are given in an outpatient clinic, which means most people are able to continue working and doing their usual activities during chemotherapy. Your doctor can tell you in general how much the chemotherapy will affect your usual activities, but it's difficult to predict exactly how you'll feel.

Ask your doctor if you'll need time off work or help around your home after treatment. Ask your doctor for the details of your chemotherapy treatments so that you can make arrangements for work, children, pets or other commitments.

Prepare for your first treatment. Ask your doctor or chemotherapy nurses how to prepare for chemotherapy. It may be helpful to arrive for your first chemotherapy treatment well rested. You might wish to eat a light meal beforehand in case your chemotherapy medications cause nausea.

Have a friend or family member drive you to your first treatment. Most people can drive themselves to and from chemotherapy sessions. But the first time you may find that the medications make you sleepy or cause other side effects that make driving difficult.

What you can expect

Determining which chemotherapy drugs you'll receive.

Your doctor chooses which chemotherapy drugs you'll receive based on several factors, including:

- Type of cancer

- Stage of cancer

- Overall health

- Previous cancer treatments

- Your goals and preferences

Discuss your treatment options with your doctor. Together you can decide what's right for you.

How chemotherapy drugs are given

Chemotherapy drugs can be given in different ways, including:

- Chemotherapy infusions. Chemotherapy is most often given as an infusion into a vein (intravenously). The drugs can be given by inserting a tube with a needle into a vein in your arm or into a device in a vein in your chest.

- Chemotherapy pills. Some chemotherapy drugs can be taken in pill or capsule form.

- Chemotherapy shots. Chemotherapy drugs can be injected with a needle, just as you would receive a shot.

- Chemotherapy creams. Creams or gels containing chemotherapy drugs can be applied to the skin to treat certain types of skin cancer.

- Chemotherapy drugs used to treat one area of the body. Chemotherapy drugs can be given directly to one area of the body. For instance, chemotherapy drugs can be given directly in the abdomen (intraperitoneal chemotherapy), chest cavity (intrapleural chemotherapy) or central nervous system (intrathecal chemotherapy). Chemotherapy can also be given through the urethra into the bladder (intravesical chemotherapy).

- Chemotherapy given directly to the cancer. Chemotherapy can be given directly to the cancer or, after surgery, where the cancer once was. As an example, thin disk-shaped wafers containing chemotherapy drugs can be placed near a tumor during surgery. The wafers break down over time, releasing chemotherapy drugs. Chemotherapy drugs may also be injected into a vein or artery that directly feeds a tumor.

How often you receive chemotherapy treatments

Your doctor determines how often you'll receive chemotherapy treatments based on what drugs you'll receive, the characteristics of your cancer and how well your body recovers after each treatment. Chemotherapy treatment schedules vary. Chemotherapy treatment can be continuous, or it may alternate between periods of treatment and periods of rest to let you recover.

Where you receive chemotherapy treatments

Where you'll receive your chemotherapy treatments depends on your situation. Chemotherapy treatments can be given:

- In an outpatient chemotherapy unit

- In a doctor's office

- In the hospital

- At home, such as when taking chemotherapy pills

You'll meet with your cancer doctor (oncologist) regularly during chemotherapy treatment. Your oncologist will ask about any side effects you're experiencing, since many can be controlled.