Type search request and press enter

Education After Apartheid

Once imprisoned for his ideas on reform, ihron rensburg is now implementing them..

Reading time min

Courtesy Ihron Rensburg

Ihron Rensburg spent much of the late 1980s detained without trial in South African prisons for his antiapartheid work with the United Democratic Front (UDF). “Solitary confinement for nine months at a stretch poses an enormous challenge to one’s intellectual, physical and spiritual faculties,” says Rensburg, MA ’94, PhD ’96. “But my colleagues and I never saw prison as something that would stop us. We knew that eventually we would dismantle the old regime and bring in nonracist, nonsexist democracy.”

His intense drive to “deracialize” the educational system carried Rensburg through the dangerous period prior to the establishment of democracy in 1994. As general secretary of the UDF’s National Education Crisis Committee, he led negotiations with apartheid administrations to reform a system that severely discriminated against black students. After earning his degrees in international development education, Rensburg became deputy director general of South Africa’s department of education. For six years he helped change K-12 curriculum to better educate and empower black citizens culturally, politically and economically.

Rensburg was named vice chancellor of the University of Johannesburg last year and has worked to merge the two university campuses and a technical school that now form UJ. His vision is to turn the univer-sity into one of the world’s premier educational institutions.

Freelance writer Marguerite Rigoglioso spoke by telephone with Rensburg at his home in Johannesburg.

What are the big challenges facing higher education in South Africa today?

To understand today’s challenges, we need to go back to the apartheid years. Thirteen years ago, with the coming of the new democracy, we had 36 higher education institutions, 21 universities and 15 polytechnics, all state run. All of them were ethnically and racially unintegrated, with schools that black, colored and Indians attended being hopelessly under-resourced, and those that whites attended being well resourced.

The challenges we had then we continue to face today, although we’ve made much progress. At that time, the participation rate of black students was not commensurate with their share of the population. Student retention and graduation rates were low. The quality of academic programs and teaching was uneven, as were academics’ qualifications and capacities.

What kind of progress have you made in addressing these problems?

In 1994, we had about 500,000 students enrolled at these 36 institutions; by 2005, that number had increased to 734,000, and we expect it to reach 800,000 in 2010. This has been part of our effort to widen and deepen participation of our citizens in higher education, the target being an 18 percent participation rate for the 18-to-24 age group. That number sat at 5 percent in 1994; now we’re in the region of 13 percent. So we’re well on track with all of these goals. The number of black students at higher education institutions has doubled in the process. In 1994, about 55 percent of the student population was black; in 2005, it was 75 percent.

We now also have a council for higher education that regularly conducts institutional audits to assess the quality of universities, academic programs and teaching. Many programs have come through with good reviews, but several were deregistered for not meeting standards. We’re driving quality up rather than being satisfied with mediocrity.

What has been your most significant improvement in creating greater access for blacks?

We’ve created a national student financial aid scheme, particularly for students from disadvantaged and black communities who are academically deserving. We’ve gone from committing 20 million rand [$2.82 million] to committing 1.2 billion rand [$148.12 million] to this program annually. It’s an astronomical investment, and probably one of the greatest success stories of the postapartheid higher education transformation program.

What areas still need work?

We have a system that still reflects a two-nation society, a society comprising those in the formal and informal sectors, the rich and the poor. Some institutions are reasonably okay, while others, those that have historically been disadvantaged, are not in a position to grow into great universities.

We also need to focus on research. We still have a racially balkanized situation here, with 12 or so traditionally white universities producing the bulk of the research output, and the bottom institutions hardly contributing. This is the result of a complex history of inadequate attention to investment in these institutions.

In the most disadvantaged part of the system, graduation rate targets are way behind the national goal. The polytechnics in particular are also struggling because most of their academics have only a master’s degree or less. So we’re challenged to drive up their qualifications to the PhD level.

In general, significant physical and financial resources will need to be invested between now and 2014, the second decade of our democracy.

What is the government’s policy in this regard?

Over the last 20 years, we’ve seen a steady decline in the real value of state investment in our education. Only in the last year or two have we seen an upturn. But we still have a ways to go. Prior to 1985, the state contributed 80 percent of the cost of the university, leaving the university to obtain the rest through student tuition and residence fees, and third-stream sources such as partnerships with research institutions, and donor and alumni contributions. We’re now sitting with a 55 percent [government] contribution. As a result, universities have had to increase tuition fees significantly. But 75 percent of our students are black, and at least half are financially disadvantaged. So any significant increases in tuition could make universities inaccessible to many students.

The expectation is that the state will lift all institutions at least up to the aggregate level of the top 10 research institutions. To do that will require considerable resources, investments and time.

Is the government willing to invest more?

The treasury has never been in a better position. They’ve become extraordinarily effective in collecting taxes as well as widening the tax base. We now have a balanced budget and a surplus. We’re in a position to expand spending. So it’s not a matter of not having the cash. It’s still the historically disadvantaged institutions that have not yet seen effort or investments put into them. But I’m much more optimistic than I would have been two years ago, based on my conversations with the education minister and senior officials in government.

Why has South Africa decided to merge a number of universities?

One of the driving forces was the need to achieve efficiency. We had polytechnics and universities with 5,000 students, and they could not operate at the appropriate scale. So we merged our universities from 36 down to 23.

How will the merger benefit the University of Johannesburg?

It allows us to build a new institution, one that brings together a polytechnic structure into a university structure. I’m confident we’ll become the benchmark in a decade’s time for institutional productivity and responsiveness in South Africa. The top five universities that have not gone through such mergers miss the dynamism and energy that is enabling us to rethink our institution.

What models have you drawn on?

We look to the new generation of universities in the United Kingdom formed in the 1980s—for example, Manchester, Warwick—institutions that were born out of polytechnics and have become giant universities. And, of course, going further back, we look to MIT and Caltech in the United States, two excellent examples of the direction we’re leading UJ in.

What might other countries learn from South Africa’s experience promoting diversity and equal opportunity in education?

You have to dream of the possibility of building institutions that are truly embracing. And you have to begin with creating the social conditions that enable widened and deepened participation, not only as a political imperative, but as a social requirement, while also maintaining and strengthening your academic standards. You must rethink the culture of the university. Does it affirm individual differences? Or does it force people to come into a particular cultural space and live with it?

You also have to look at ways to identify at-risk students early on. You have to put in place the academic support services and systems, the student-counseling system, the language resources, to enable this wider participation to be successful. It’s one thing to widen participation; it’s another to widen success. These are some of the big challenges that face all universities as we move toward greater inclusion. It’s an international phenomenon.

Trending Stories

Advice & Insights

Law/Public Policy/Politics

You May Also Like

A special delivery.

Robot racers simulate military supply missions in city traffic.

Banding Together

Music brings gown to town.

- Letters to the Editor

Stanford Alumni Association

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Class Notes

Collections

- Recent Grads

- Vintage 1973

- Sandra Day O'Connor

- Mental Health

- Resolutions

- The VanDerveer Files

- The Stanfords

Get in touch

- Submit an Obituary

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Code of Conduct

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Non-Discrimination

© Stanford University. Stanford, California 94305.

- Introduction

Unequal education: apartheid's legacy

- Rediscovered activism

- Educational haves and have-nots

- Broken windows, missing books

- Campaign for school infrastructure

- Going to court

- Settlement and a draft

- Rushing into a quandary

- Download this case as a PDF

The Europeans who colonized Africa generally viewed the natives as intellectually and morally inferior, and exploited the labor of the local populations. Thus it was no surprise that when, in the early 20th century, colonial governments instituted public education systems, the goal was to prepare young Africans to be compliant laborers. In Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe), for instance, the formal British education policy aimed to “develop a vast pool of cheap unskilled manual labor.” [1] The result was, in effect, two school systems: one appropriately subsidized, and the other chronically under-resourced.

In South Africa, the minority white population retained control of the government when the then-Union of South Africa gained full independence from the United Kingdom in 1931. At the time, the education system was segregated and unequal. As one history recounted, “While white schooling was free, compulsory and expanding, black education was sorely neglected. Underfunding and an urban influx led to gravely insufficient schooling facilities, teachers and educational materials as well as student absenteeism or non-enrollment.” [2]

In 1948, 90 percent of the few black South Africans who went to school attended mission schools that were answerable to the country’s provincial governments. That year, the Afrikaner-dominated National Party won control of the white government and instituted the infamous apartheid system. Under apartheid, the government forced everyone to register her or his race and further restricted where nonwhites could live and work. It also established separate public amenities for whites and nonwhites similar to the US South during segregation. Education was a key component of apartheid, and the Bantu Education Act of 1953 centralized black South African education and brought it under the control of the national government. [3] The public schools that replaced the mission schools were funded via a tax paid by black South Africans; the monies raised were inadequate to maintain the schools properly. In 1961, just 10 percent of black teachers had graduated from high school. By 1967, the student-teacher ratio had risen to 58 to 1. [4]

© African National Congress, via Twitter

Soweto. In June 1976, high school students in Soweto, a black township on the southwest side of Johannesburg, organized a mass protest against unequal education. On June 16, thousands of students marched through the streets on their way to a rally at a stadium. The South African police broke up the march using dogs, batons, tear gas and, ultimately, gunfire. The police action and ensuing confrontations with the police left hundreds of students dead and more than a thousand injured. [5] The events of the day sparked a nationwide uprising, made Soweto an emblem of the anti-apartheid movement, put the apartheid education system in the spotlight, and cemented the role of students in the nation’s political struggle.

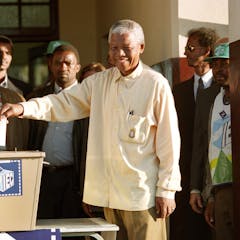

Nearly two decades later, on April 27, 1994, the African National Congress (ANC) won South Africa’s first democratic election, ending apartheid and the era of white minority rule. The country’s new constitution declared that all children had the right to a basic education. But overcoming apartheid’s legacy of severe educational inequality was a monumental task. In the first years after the constitution’s adoption, formerly nonwhite schools, meaning black, colored and Indian, graduated far fewer students than formerly white schools. Formerly black schools, which remained nearly 100 percent black, had abysmal matriculation rates.

As of 2000, 10 percent of formerly black schools graduated fewer than 20 percent of their students, 35 percent graduated 20-39 percent, 32 percent graduated 40-59 percent, 16 percent graduated 60-79 percent, and just 7 percent graduated 80-100 percent of their students. In contrast, 2 percent of formerly white schools graduated 60-79 percent of their students, and 98 percent graduated 80-100 percent. [6]

[1] Dickson A. Mungazi, Colonial education for Africans: George Stark's policy in Zimbabwe , New York: Praeger, 1991.

[2] Bantu Education Policy , South African History Online. See http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/bantu-education-policy

[5] South African History Online lists 383 names as casualties of the uprising. See: http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/june-16-soweto-youth-uprising?page=8

[6] Servaas van der Berg, “Apartheid’s Enduring Legacy: Inequalities in Education,” Journal of African Economies , Volume 16, Number 5, published online August 2, 2007, pp. 849–880.

Biographies

- Doron Isaacs

- Brad Brockman

- Geoff Budlender

System menu

Higher education post-apartheid: insights from South Africa

Chrissie Boughey and Sioux McKenna, Understanding Higher Education: Alternative Perspectives, African Minds, 2021

- Book review

- Published: 22 October 2021

- Volume 84 , pages 691–693, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Paul Othusitse Dipitso ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8351-6971 1

2781 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The implications of apartheid and decolonisation in higher education continue to be at the centre of critical debates in South Africa. Researchers of higher education continue to grapple with complex issues regarding curriculum, quality assessment, student development, as well as other aspects of teaching and learning. The need to understand the variety of perspectives that exist in the context of teaching and learning and not least challenges faced is still higher on researchers’ agenda.

In Understanding Higher Education: Alternative Perspectives , Chrissie Boughey and Sioux McKenna provide critical insights into the changes that occurred within South African higher education over the past 20 years. The book problematises higher education issues in South Africa whilst acknowledging the contextual realities of the Global South. Boughey and McKenna essentially examine teaching and learning in South Africa and ask what changes occurred from the higher education reforms implemented post-apartheid. The book draws upon the structural developments in teaching and learning across universities and demonstrates how colonialism and apartheid affected access to knowledge. Its purpose is to inform the readers about the implications of globalisation and neoliberalism by reflecting on how this interplay enabled and constrained participation in higher education.

The book is organised into seven thematic chapters. In the first chapter, the authors focus on the value of higher education in a global world where the knowledge economy is critical. The chapter makes a case for higher education as a public good as opposed to being a private good, demand for high skills, quality assurance standards, accountability, and transparency within higher education. Chapter 2 turns to demonstrate the ability of social and critical theory in providing explanatory power concerning change in higher education. The authors show how the critical reality framework provided a lens of understanding policy changes in higher education. Of particular note are the consequences of apartheid and colonialism that shaped the higher education structure by enabling/constraining new ideas. Chapter 3 is concerned with the impacts of neoliberal policies within the higher education system. The authors’ critiques reveal that these policies affect the funding framework, governance structures, qualification frameworks, compliance, and accreditation systems.

Student agency is the central theme of Chapter 4. Here, the authors reveal the power of discourse linked to understanding university students in a context where social structures influence student success and constrain the learning process. It takes on issues such as ideological institutional practices that tend to enhance misappropriation of teaching and learning theories, the manifestation of language practices resulting in language problems, and lack of access to powerful disciplinary knowledge.

In the following chapter, the authors emphasise how the curriculum enables learners to access learning experiences that are valuable for social mobility. They highlight that critically challenging the dominant ideas and practices that legitimise knowledge in the curriculum enhances learning experiences. Chapter 6 illuminates the academics’ agency based on their ability to balance teaching, research, and community engagement. The authors also observe that, also in South Africa, the academics’ agency continue to be shaped by the global, national, and institutional trends fostering managerialism in universities and further subjecting academics to the principles of the new public management.

The final chapter concludes the book by ascertaining the growth of South African higher education in the context of institutional inequalities. In addition, the authors suggest a robust funding system that would enable differentiation, equity, and research culture. In the last section, the authors provide a COVID-19 postscript to articulate the implications that emerged from online learning. Chiefly, their concern is that online learning has adopted a technicist approach to learning; hence, this digital transformation results in digital divides that perpetuate inequalities among learners. Boughey and McKenna argue that equity requires the value of harmonising forms of knowledge to sustain epistemological access, epistemic justice, and maintain a social and critical deliberation on curricula.

The authors have delivered the key message in a consistent tone that enables higher education researchers to connect instantly with the subject matter. Boughey and McKenna demonstrate that widening participation in higher education is a vital tool to enhance social justice. Their contribution is valuable for the reason that they addressed topical issues concerned with student learning in higher education by providing a historical account of the factors that influenced the systemic changes. The book acknowledges that managerialism and the principles of new public management seem to dominate the higher education discourse in South Africa.

The book demonstrates that universities tend to overlook contextual realities, which sets the ground for decontextualizing students. One can note how the limited access to powerful disciplinary knowledge hinders students to develop new knowledge that enables innovation, thus restricting human capital development (Shay, 2013 ). Valuable insights to curriculum planners in higher education on how to be innovative when dealing with pedagogical knowledge are offered by the book, which could enable students to access powerful disciplinary knowledge equitably. Interestingly, the comprehensive application of the critical realist framework in this book provides researchers with new perspectives of dealing with teaching and learning in their respective fields.

The implications of massification in higher education, as the book shows have tremendous effects on resource allocation. The authors call for reimagining higher education in a context where public funding is declining, yet issues of access and equity are still a challenge. Notably, it seems that teaching and learning would be severely challenged by this shift, thus largely affecting students from poverty-stricken backgrounds in South Africa. Masehela ( 2018 ) argues that unequal access to higher education negatively affects students from low-income backgrounds due to financial constraints. As research from across the world and not least from South Africa has shown, poverty remains to be a contributing factor to the lack of access to higher education.

The timely critical debates raised by this book challenge the higher education agenda in the context of South Africa given that teaching and learning continue to experience a paradigm shift due to the 2015/16 #FeesMustFall movement, which advocated for decolonised higher education. The intellectual debates conceived in the book connect with ongoing scholarly engagements regarding the transformation in higher education post-apartheid. The debates interrogate the apartheid legacy characterised by inequalities that affect teaching and learning in higher education. The contemporary higher education system in South Africa responds to the realities of transforming apartheid policies and practices and educating diverse students who often come from low-income families (Scott & Ivala, 2019 ).

The challenge of student development and provision of skilled labour in higher education remains critical. In reading this book, one gets a sense of reflecting on how higher education institutions can improve employability in a context where graduate work readiness is linked to teaching and learning as well as university reputation. This requires rigorous thinking concerning language issues and knowledge inequalities that potentially affect the acquisition of employability skills. Essentially, a paradigm shift is necessary for enabling universities and industries to collaborate to create teaching and learning strategies that support employability. Crucially, one ought to note that higher education and work relations are context-bound, thus requiring effective coexistence (Marginson, 2019 ). As such, the constructive critiques raised in the book create conditions for further intellectual development to respond to the demands placed on higher education to produce work-ready graduates.

The key strength of the book is that it orients the reader to understand that institutional differentiation should facilitate teaching geared towards promoting epistemological access and epistemic justice. The book is beneficial in the sense that it illuminates how the historical context of South Africa higher education influences the present practices. It has been demonstrated that the change in student demographics calls for a rethinking at an institutional level to facilitate systemic change. Accordingly, the critical theory employed for the analysis provides valuable insights that demonstrate the factors that enabled and constrained systemic change within higher education.

This book provides an exciting opportunity to advance the knowledge of researchers who intend to employ critical analysis perspectives in the scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education. Interestingly, Boughey and McKenna argue that the decolonised knowledge discourses still lack a clear definition, thus making it difficult to produce and teach. As a result, conceptualising decolonised knowledge in higher education remains to be a significant issue for further research. The future investigation would possibly explore how decolonised knowledge intellectually contributes to social justice.

Marginson, S. (2019). Limitations of human capital theory*. Studies in Higher Education, 44 (2), 287–301.

Article Google Scholar

Masehela, L. (2018). The rising challenge of university access for students from low-income families. In P. Ashwin & J. M. Case (Eds.), Higher Education Pathways in South African Undergraduate Education and the Public Good . African Minds

Scott, C. L., & Ivala, E. N. (2019). Moving from apartheid to a post-apartheid state of being and its impact on transforming higher education institutions in South Africa. In C. L. Scott & E. N. Ivala (Eds.), Transformation of Higher Education Institutions in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Shay, S. (2013). Conceptualizing curriculum differentiation in higher education: A sociology of knowledge point of view. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34 (4), 563–582.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Post School Studies, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

Paul Othusitse Dipitso

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul Othusitse Dipitso .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dipitso, P.O. Higher education post-apartheid: insights from South Africa. High Educ 84 , 691–693 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00780-x

Download citation

Accepted : 12 October 2021

Published : 22 October 2021

Issue Date : September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00780-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Apartheid and education : the education of Black South Africans

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

obscured text on page 11-16

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

128 Previews

2 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station13.cebu on June 12, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

School Enrollment in Apartheid Era South Africa

Catherine Scotton / Getty Images

- American History

- African American History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Postgraduate Certificate in Education, University College London

- M.S., Imperial College London

- B.S., Heriot-Watt University

It is well known that one of the fundamental differences between the experiences of whites and Blacks in Apartheid-era South Africa was education. While the battle against enforced education in Afrikaans was eventually won, the Apartheid government's Bantu education policy meant that Black children did not receive the same opportunities as white children.

Data on School Enrollment for Blacks and whites in South Africa in 1982

Using data from South Africa's 1980 census, roughly 21 percent of the white population and 22 percent of the Black population were enrolled in school. There were approximately 4.5 million whites and 24 million Blacks in South Africa in 1980. Differences in population distributions, however, mean that there were Black children of school age not enrolled in school.

The second fact to consider is the difference in government spending on education. In 1982, the Apartheid government of South Africa spent an average of R1,211 on education for each white child (approximately $65.24 USD) and only R146 for each Black child (approximately $7.87 USD).

The quality of teaching staff also differed. Roughly a third of all white teachers had a university degree, the rest had all passed the Standard 10 matriculation exam. Only 2.3 percent of Black teachers had a university degree and 82 percent had not even reached the Standard 10 matriculation. More than half had not reached Standard 8. Education opportunities were heavily skewed towards preferential treatment for whites.

Finally, although the overall percentages for all scholars as part of the total population is the same for whites and Blacks, the distributions of enrollment across school grades are completely different.

White Enrollment in South African Schools in 1982

It was permissible to leave school at the end of Standard 8 and there was a relatively consistent level of attendance up to that level. What is also clear is that a high proportion of students continued on to take the final Standard 10 matriculation exam. Opportunities for further education also gave impetus to white children staying in school for Standards 9 and 10.

The South African education system was based on end-of-year exams and assessments. If you passed the exam, you could move up a grade in the next school year. Only a few white children failed end-of-year exams and needed to re-sit school grades. Remember, the quality of education was significantly better for whites.

Black Enrollment in South African Schools in 1982

In 1982, a much larger proportion of Black children were attending primary school (grades Sub A and B), compared to the final grades of secondary school.

It was common for Black children in South Africa to attend school for fewer years than white children. Rural life had significantly greater demands on the time of Black children, who were expected to help out with livestock and household chores. In rural areas, Black children often started school later than children in urban areas.

The disparity in teaching experienced in white and Black classrooms and the fact that Blacks were usually taught in their second (or third) language, rather than their primary one, meant that back children were much more likely to fail the end-of-year assessments. Many were required to repeat school grades. It was not unknown for a pupil to re-do a particular grade several times.

There were fewer opportunities for further education for Black students and thus, less reason to stay on at school.

Job reservation in South Africa kept white-collar jobs firmly in the hands of whites. Employment opportunities for Blacks in South Africa were generally manual jobs and unskilled positions.

- Understanding South Africa's Apartheid Era

- 16 June 1976 Student Uprising in Soweto

- What Was Apartheid in South Africa?

- South African Apartheid-Era Identity Numbers

- A Brief History of South African Apartheid

- The End of South African Apartheid

- South Africa's Extension of University Education Act of 1959

- Apartheid Era Signs - Racial Segregation in South Africa

- The Origins of Apartheid in South Africa

- Apartheid Quotes About Bantu Education

- South Africa's Black Consciousness Movement in the 1970s

- Pass Laws During Apartheid

- Grand Apartheid in South Africa

- Apartheid 101

- Biography of Nontsikelelo Albertina Sisulu, South African Activist

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: October 7, 2010

Apartheid, or “apartness” in the language of Afrikaans, was a system of legislation that upheld segregation against non-white citizens of South Africa. After the National Party gained power in South Africa in 1948, its all-white government immediately began enforcing existing policies of racial segregation. Under apartheid, nonwhite South Africans—a majority of the population—were forced to live in separate areas from whites and use separate public facilities. Contact between the two groups was limited. Despite strong and consistent opposition to apartheid within and outside of South Africa, its laws remained in effect for the better part of 50 years. In 1991, the government of President F.W. de Klerk began to repeal most of the legislation that provided the basis for apartheid.

Apartheid in South Africa

Racial segregation and white supremacy had become central aspects of South African policy long before apartheid began. The controversial 1913 Land Act , passed three years after South Africa gained its independence, marked the beginning of territorial segregation by forcing Black Africans to live in reserves and making it illegal for them to work as sharecroppers. Opponents of the Land Act formed the South African National Native Congress, which would become the African National Congress (ANC).

Did you know? ANC leader Nelson Mandela, released from prison in February 1990, worked closely with President F.W. de Klerk's government to draw up a new constitution for South Africa. After both sides made concessions, they reached agreement in 1993, and would share the Nobel Peace Prize that year for their efforts.

The Great Depression and World War II brought increasing economic woes to South Africa, and convinced the government to strengthen its policies of racial segregation. In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party won the general election under the slogan “apartheid” (literally “apartness”). Their goal was not only to separate South Africa’s white minority from its non-white majority, but also to separate non-whites from each other, and to divide Black South Africans along tribal lines in order to decrease their political power.

Apartheid Becomes Law

By 1950, the government had banned marriages between whites and people of other races, and prohibited sexual relations between Black and white South Africans. The Population Registration Act of 1950 provided the basic framework for apartheid by classifying all South Africans by race, including Bantu (Black Africans), Coloured (mixed race) and white.

A fourth category, Asian (meaning Indian and Pakistani) was later added. In some cases, the legislation split families; a parent could be classified as white, while their children were classified as colored.

A series of Land Acts set aside more than 80 percent of the country’s land for the white minority, and “pass laws” required non-whites to carry documents authorizing their presence in restricted areas.

In order to limit contact between the races, the government established separate public facilities for whites and non-whites, limited the activity of nonwhite labor unions and denied non-white participation in national government.

Apartheid and Separate Development

Hendrik Verwoerd , who became prime minister in 1958, refined apartheid policy further into a system he referred to as “separate development.” The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959 created 10 Bantu homelands known as Bantustans. Separating Black South Africans from each other enabled the government to claim there was no Black majority and reduced the possibility that Black people would unify into one nationalist organization.

Every Black South African was designated as a citizen as one of the Bantustans, a system that supposedly gave them full political rights, but effectively removed them from the nation’s political body.

In one of the most devastating aspects of apartheid, the government forcibly removed Black South Africans from rural areas designated as “white” to the homelands and sold their land at low prices to white farmers. From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in the Bantustans, where they were plunged into poverty and hopelessness.

Opposition to Apartheid

Resistance to apartheid within South Africa took many forms over the years, from non-violent demonstrations, protests and strikes to political action and eventually to armed resistance.

Together with the South Indian National Congress, the ANC organized a mass meeting in 1952, during which attendees burned their pass books. A group calling itself the Congress of the People adopted a Freedom Charter in 1955 asserting that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black or white.” The government broke up the meeting and arrested 150 people, charging them with high treason.

Sharpeville Massacre

In 1960, at the Black township of Sharpeville, the police opened fire on a group of unarmed Black people associated with the Pan-African Congress (PAC), an offshoot of the ANC. The group had arrived at the police station without passes, inviting arrest as an act of resistance. At least 67 people were killed and more than 180 wounded.

The Sharpeville massacre convinced many anti-apartheid leaders that they could not achieve their objectives by peaceful means, and both the PAC and ANC established military wings, neither of which ever posed a serious military threat to the state.

Nelson Mandela

By 1961, most resistance leaders had been captured and sentenced to long prison terms or executed. Nelson Mandela , a founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), the military wing of the ANC, was incarcerated from 1963 to 1990; his imprisonment would draw international attention and help garner support for the anti-apartheid cause.

On June 10, 1980, his followers smuggled a letter from Mandela in prison and made it public: “UNITE! MOBILIZE! FIGHT ON! BETWEEN THE ANVIL OF UNITED MASS ACTION AND THE HAMMER OF THE ARMED STRUGGLE WE SHALL CRUSH APARTHEID!”

President F.W. de Klerk

In 1976, when thousands of Black children in Soweto, a Black township outside Johannesburg, demonstrated against the Afrikaans language requirement for Black African students, the police opened fire with tear gas and bullets.

The protests and government crackdowns that followed, combined with a national economic recession, drew more international attention to South Africa and shattered any remaining illusions that apartheid had brought peace or prosperity to the nation.

The United Nations General Assembly had denounced apartheid in 1973, and in 1976 the UN Security Council voted to impose a mandatory embargo on the sale of arms to South Africa. In 1985, the United Kingdom and United States imposed economic sanctions on the country.

Under pressure from the international community, the National Party government of Pieter Botha sought to institute some reforms, including abolition of the pass laws and the ban on interracial sex and marriage. The reforms fell short of any substantive change, however, and by 1989 Botha was pressured to step aside in favor of another conservative president, F.W. de Klerk, who had supported apartheid throughout his political career.

When Did Apartheid End?

Though a conservative, De Klerk underwent a conversion to a more pragmatic political philosophy, and his government subsequently repealed the Population Registration Act, as well as most of the other legislation that formed the legal basis for apartheid. De Klerk freed Nelson Mandela on February 11, 1990.

A new constitution, which enfranchised Black citizens and other racial groups, took effect in 1994, and elections that year led to a coalition government with a nonwhite majority, marking the official end of the apartheid system.

The End of Apartheid. Archive: U.S. Department of State . A History of Apartheid in South Africa. South African History Online . South Africa: Twenty-Five Years Since Apartheid. The Ohio State University: Stanton Foundation .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- EN / EL / ES / PT / ZH

Apartheid Education

Apartheid was a system of government in South Africa, abolished in 1994, which systematically separated groups on the basis of race classification. The Apartheid system of racial segregation was made law in South Africa in 1948, when the country was officially divided into four racial groups, White, Black, Indian and Coloureds (or people of mixed race, or non-Whites who did not fit into the other non-White categories). ‘Homelands’ were created for Blacks, and when they lived outside of the homelands with Whites, non-Whites could not vote and had separate schools and hospitals, and even beaches where they could swim or park benches they could sit on.

It was a criminal offence for a White person to have sexual relations with a person of another race, but the person of the other race, not the White, would be prosecuted as a result. The system of Apartheid came to an end when President Nelson Mandela came to power in 1994

A classroom in Crossroads, a squatter township in South Africa, 1979. ] ‘Apartheid’ means ‘being apart’ in Dutch and Afrikaans, a variation of Dutch spoken by the Dutch settlers of South Africa.

With these notorious words, Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd introduced Bantu Education to Parliament in 1953. This began the era of apartheid education. In 1959 universities were segregated. In 1963 a separate education system was set up for the ‘coloureds.’ Indian education followed in 1964. And an Education Act for whites was passed in 1967 …

The 37 million people who live in South Africa [in 1990, just before the end of Apartheid] … are … officially divided into four ‘population groups’: ‘African’ (about 75%—of whom some 45% are under the age of 15), ‘Whites’ (13%), ‘Coloureds’ (9%) and ‘Indians’ (3%). Apart from a few ‘mixed’ ‘private’ schools, there are separate schools for the four ‘population groups’; it is illegal for a person to attend a state school designated for a ‘population group’ other than that to which she has officially been assigned, or for a school to admit as a pupil someone from the ‘wrong population group’.

Along almost any dimension of comparison, there have been, and are glaring inequalities between the four schooling systems in South Africa. This applies to teacher qualifications, teacher-pupil ratios, per capita funding, buildings, equipment, facilities, books, stationery … and also to ‘results’ measured in terms of the proportions and levels of certificates awarded. Along these dimensions, “White’ schools are far better off than any of the others, and ‘Indian’ and ‘Coloured’ schools are better off than those for ‘Africans’. Schooling is compulsory for ‘Whites’, ‘Indians’ and ‘Coloureds’ but not for ‘Africans’.

When the apartheid government came to power in 1948, it saw the schooling system as the major vehicle for the propagation of its beliefs. For the period of its duration, schools were one of the system’s most stark symbols. Today, as a new and democratic government seeks to repair and reconstruct the fabric of South Africa’s ravaged past, it is to the schooling system that much of its attention has turned.

The structure for education was marked by the central principle of apartheid, namely separate schooling infrastructure for separate groups. In terms of the apartheid principle, nineteen education departments were established. Each designated ethnic group had its own education infrastructure.

Curriculum development in South African education during the period of apartheid was controlled tightly from the center. While theoretically, at least, each separate department had its own curriculum development and protocols, in reality curriculum formation in South Africa was dominated by committees attached to the white House of Assembly … So prescriptive was this system, abetted on the one hand by a network of inspectors and subject advisors and on the other by several generations of poorly qualified teachers, that authoritarianism, rote learning, and corporal punishment were the rule. These conditions were exacerbated in the impoverished environments of schools for children of color. Examination criteria and procedures were instrumental in promoting the political perspectives of those in power and allowed teachers very little latitude to determine standards or to interpret the work of their students.

Morrow, Walter Eugene. 1990. ‘Aims of Education in South Africa.’ International Review of Education/Internationale Zeitschrift fur Erziehunswissenschaft/Revue Internationale de l’Education 36:171–181. p. 174.

Gilmore, David, Crain Soudien and David Donald. 1999. ‘Post-Apartheid Policy and Practice: Educational Reform in South Africa.’ Pp. 341–350 in Education in a Global Society: A Comparative Perspective, edited by Mazurek Kas, Margaret Winzer and Czeslaw Czeslaw Majorek. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. pp. 341–343. || Amazon || WorldCat

Articles on What happened to Nelson Mandela's South Africa?

Displaying all articles.

South Africans tasted the fruits of freedom and then corruption snatched them away – podcast

Gemma Ware , The Conversation and Thabo Leshilo , The Conversation

After the euphoria of Nelson Mandela’s election, what happened next? Podcast

What happened to Nelson Mandela’s South Africa? A new podcast series marks 30 years of post-apartheid democracy

Thabo Leshilo , The Conversation

Related Topics

- African National Congress (ANC)

- Nelson Mandela

- South Africa

- South Africa democracy 30

- The Conversation Weekly

Top contributors

Associate Professor, Political Sciences, and Deputy Dean Teaching and Learning (Humanities), University of Pretoria

Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

Adjunct Professor, University of the Witwatersrand

Professor of Public Affairs, Tshwane University of Technology

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

- COVID-19 Library Updates

- Make Appointment

LSP 112 (Adibe): Apartheid in Twentieth-Century South Africa: Find Articles

- Find Articles

- Find Primary Sources & Data

Research Databases

- Politics Collection (ProQuest) This link opens in a new window Includes PAIS Index, Policy File Index, Political Science Database, and Worldwide Political Science Abstracts. Covers international literature in political science and public administration/policy, along with related fields. It forms part of the Social Science Premium Collection. Dates covered: 1914-present.

- Historical Abstracts This link opens in a new window Indexes journals, books and dissertations on all time periods of world history, excluding the United States and Canada; for those countries use the database America: History & Life. "Dates covered" refers to publication dates included; all historic eras are addressed, from B.C. to present day. Dates Covered: 1954-present.

- Project MUSE This link opens in a new window Full-image journals in the humanities and social sciences. Extent: Multidisciplinary

- Africana Periodical Literature An index of over 300 selected periodicals (mostly scholarly) which are acquired regularly from 29 African countries.

- Foreign Affairs

- Africa Today

- Journal of Modern African Studies

- Africa Confidential

- Ethics & International Affairs

- << Previous: Find News

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 8:21 AM

- URL: https://libguides.depaul.edu/AdibeLSP112

How South Africa’s former leader Zuma turned on his allies and became a surprise election foe

JOHANNESBURG (AP) — South Africa faces an unusual national election this year, its seventh vote since transitioning from white minority rule to a democracy 30 years ago. Polls and analysts warn that for the first time, the ruling African National Congress party that has comfortably held power since Nelson Mandela became the country’s first Black president in 1994 might receive less than 50% of votes.

One big reason is Jacob Zuma, the former president and ANC leader who stepped down in disgrace in 2018 amid a swirl of corruption allegations but has emerged in recent months with a new political party. It intends to be a major election player as the former president seeks revenge against former longtime allies.

Here is what you need to know about the 82-year-old Zuma’s return to the political ring and how it might play a significant election role.

WHO IS JACOB ZUMA?

Zuma has long been one of South Africa’s most recognizable politicians. He was a senior leader in the ANC during the liberation struggle against apartheid. A former ANC intelligence chief, he has repeatedly threatened to reveal some of the party’s secrets. While Zuma was not one of Mandela’s preferred choices to succeed him, Mandela trusted Zuma to play an influential role in ending deadly political violence that engulfed KwaZulu-Natal province before the historic 1994 elections. The province has remained a vocal base of support for Zuma ever since, and members of Zuma’s Zulu ethnic group make up its majority. Zuma became deputy leader of the ANC in 1997 and was appointed South Africa’s deputy president in 1999.

HOW DID HE BECOME PRESIDENT?

Zuma’s path to power included legal challenges. In 2006, he was found not guilty of raping the daughter of a comrade at Zuma’s home in Johannesburg. A year earlier, he was fired as South Africa’s deputy president after his financial advisor was convicted for corruption for soliciting bribes for Zuma during an infamous arms deal. Alleging a political witch hunt, Zuma launched an aggressive political campaign that saw him elected ANC president in 2007. His campaign appealed to widespread discontent with then-President Thabo Mbeki, who was often described as autocratic and aloof. The corruption charges against Zuma were later dropped, amid controversy, and he was elected South Africa’s president in 2009.

HOW DID HE LOSE POWER?

Zuma’s presidency was often under fire. His close friends and allies, the Gupta family, were accused of influencing appointments to key cabinet positions in exchange for lucrative business deals. The allegations of corruption in government and state-owned companies eventually led the ANC force Zuma to resign in 2018. A judicial commission of inquiry uncovered wide-ranging evidence, and Zuma in 2021 was convicted and sentenced to 15 months in jail for refusing to testify. Zuma remains aggrieved with the ANC and his successor, President Cyril Ramaphosa. But few South Africans expected the break to go so far.

HOW HAS HE REEMERGED?

Zuma shocked the country in December by denouncing the ANC and campaigning against a party that had been at the heart of his political career. His new political party, UMkhonto WeSizwe, was named after the ANC’s military wing, which was disbanded at the end of the struggle against white minority rule. The ANC has launched a legal case seeking to stop the new party from using a name and logo that are similar to those of the military wing. The charismatic Zuma continues to crisscross the country, delivering lively speeches, and an image of his face will represent the party on ballots.

WHAT ARE ZUMA’S ELECTION CHANCES?

The ANC already had been facing pressure from other opposition parties. But Zuma’s new party threatens to draw support from within the often divided ANC. South Africa’s electoral body has cleared him to run for a parliament seat, despite his past conviction. Polls suggest the new party may emerge as one of the country’s biggest opposition parties and could play a significant role if the weakening ANC must form coalitions to run the country. Addressing his supporters at a recent rally, Zuma declared that “I need to return so that I can fix things.”

Most Read Nation & World Stories

- Hikers kept climbing Hawaii’s ‘Stairway to Heaven.’ Now it’ll be removed

- Dubai grinds to standstill as cloud seeding worsens flooding

- These two Oregon and Washington cities named among best places to live in U.S.

- A real prince of Denmark tries to live a normal Washington, D.C., life

- O.J. Simpson feared he had CTE but his family has said a ‘hard no’ to brain study

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Apartheid in South Africa: Effects on Life and Education. The National Party gained power in South Africa in 1948, approximately 30 years after its founding. Originally, the National Party was created as a new, opposing political party to the ruling South African Party in 1913-14 by General JBM Hertzog (Carter, 1955, "Apartheid and reactions ...

Bantu Education Act, South African law, enacted in 1953 and in effect from January 1, 1954, that governed the education of Black South African (called Bantu by the country's government) children. It was part of the government's system of apartheid, which sanctioned racial segregation and discrimination against nonwhites in the country.. From about the 1930s the vast majority of schools ...

Historically, education in South Africa formed an important part of the government's plan to develop a racially segregated society. While there is a significant amount of research that describes the widespread problems of schooling in South Africa, there are few reports about the subjective qualities of education.

The History of Education under Apartheid, 1948-1994: The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall Be Opened. Edited by Peter Kallaway. History of Schools and Schooling, Vol. 28. New York: Peter Lang, 2002. Pp. xvi, 399. 10 illustrations. $34.95 paper. Though about the history of education during South Africa's apartheid era, this

During the Apartheid era in South Africa, education was organized along racial lines. The apartheid policy of separate development partitioned the country into racial lines where each population group and homelands designed specifically for blacks, had their own departments of education, 18 such departments that centrally governed public schools.

Education in South Africa. Since 1986, though, discourses of schooling and education in South Africa shifted from analysis of experiences under apartheid to a formulation of educational alternatives. This was most poignantly captured in the idea of a "people's education". People's education was a populist response to apartheid; it provided

Education After Apartheid. Once imprisoned for his ideas on reform, Ihron Rensburg is now implementing them. November/December 2007. Reading time 8 min. Courtesy Ihron Rensburg. Ihron Rensburg spent much of the late 1980s detained without trial in South African prisons for his antiapartheid work with the United Democratic Front (UDF).

Sayed Yusuf, Kanjee Anil. 2013. An overview of education policy change in post-apartheid South Africa. In The search for education quality in post-apartheid South Africa: Interventions to improve learning and teaching, eds. Sayed Yusuf, Kanjee Anil, Mokubung Nkomo, 5-38. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Abstract. In this article, I explore the utility of effectively maintained inequality theory in examining educational inequality in South Africa at the end of the apartheid era. As an obviously unequal country, South Africa provides an excellent opportunity to test the claim that even with large quantitative differences in achievement ...

Education was a key component of apartheid, and the Bantu Education Act of 1953 centralized black South African education and brought it under the control of the national government. [3] The public schools that replaced the mission schools were funded via a tax paid by black South Africans; the monies raised were inadequate to maintain the ...

South Africa is failing too many of its young people when it comes to education. Although it has made significant progress since the end of apartheid in widening access this has not always translated into a quality education for all pupils. The system continues to be dogged by stark inequalities and chronic underperformance that have […]

Despite the end of apartheid, South Africa grapples with its legacy. Unequal education, segregated communities, and economic disparities persist. However, the National Action Plan to combat racism, xenophobia, racial discrimination and related intolerance, provides the basis for advancing racial justice and equality.

Apartheid was a policy in South Africa that governed relations between the white minority and nonwhite majority during the 20th century. Formally established in 1948, it sanctioned racial segregation and political and economic discrimination against nonwhites. Apartheid legislation was largely repealed in the early 1990s.

Jennifer S. Roberts. This paper explores the profound connection between race, gender, and culture in post-apartheid education at a public Afrikaans dual-language school in South Africa. Illustrating how the residues and remnants of apartheid legacies propagate arcane constructions of whiteness through interwoven racial and gendered stereotypes ...

Legacy of apartheid still haunts pupils fighting for a decent education in South Africa, 30 years later. Children in townships and rural areas struggle to access quality schools in affluent ...

Education: Keystone of Apartheid1. Walton R. Johnson*. This paper is an analysis of the relationship of education to the system of apartheid in South Africa. It explores the manner in which education is being manipulated to maintain a system of social stratification based upon race, ethnic background and language.

The implications of apartheid and decolonisation in higher education continue to be at the centre of critical debates in South Africa. Researchers of higher education continue to grapple with complex issues regarding curriculum, quality assessment, student development, as well as other aspects of teaching and learning.

Education was segregated by the 1953 Bantu Education Act, which crafted a separate system of education for black South African students and was designed to prepare black people for lives as a labouring class. ... pursuant to which the US maintained close relations with the Apartheid South African government.

Charles T. Loram and the American model for African education in South Africa. Administration of financing of African education in South Africa 1910 -- 1953. Apartheid and education. Role of fundamental pedagogics in the formulation of educational policy in South Africa. Hearts and minds of the people. Bantu education: apartheid ideology and ...

One of the key features of South Africa's education system during the apartheid regime was pronounced education inequality and fragmentation (McKeever, 2017). The system, prior to 1994, was that ...

In 1982, the Apartheid government of South Africa spent an average of R1,211 on education for each white child (approximately $65.24 USD) and only R146 for each Black child (approximately $7.87 USD). The quality of teaching staff also differed. Roughly a third of all white teachers had a university degree, the rest had all passed the Standard ...

South Africa: Broken and unequal education perpetuating poverty and inequality. The South African education system, characterised by crumbling infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms and relatively poor educational outcomes, is perpetuating inequality and as a result failing too many of its children, with the poor hardest hit according to a new report published by Amnesty International today.

Under Apartheid South Africa, there were eight education departments that followed different curricula and offered different standards of learning quality. ... As discussed, ICT usage in South African education has slowly developed from computer use for basic functions like word processing to mobile technology and app usage by students and into ...

Apartheid, the legal and cultural segregation of the non-white citizens of South Africa, ended in 1994 thanks to activist Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk.

Apartheid Education. Apartheid was a system of government in South Africa, abolished in 1994, which systematically separated groups on the basis of race classification. The Apartheid system of racial segregation was made law in South Africa in 1948, when the country was officially divided into four racial groups, White, Black, Indian and ...

The aim of post apartheid education is to improve the quality of life for every South African regardless of disability, race, color or creed. Apartheid education set the stage for educational disparities in school funding, quality of content and resources in black schools throughout the country. Thus, post apartheid education is aimed at ...

Published: May 7, 2014 1:02am EDT. Since the dawn of democracy in South Africa 20 years ago, pass rates in the country's end-of-school exam - commonly known as the matric - have been ...

A lot of good has happened since apartheid ended in 1994. Sadly, 30 years on, the country is in a political and economic crisis. Many are questioning the choices of the past three decades.

LSP 112 (Adibe): Apartheid in Twentieth-Century South Africa; Find Articles; LSP 112 (Adibe): Apartheid in Twentieth-Century South Africa: Find Articles Research resources for students in LSP 112, Spring 2024 ... Indexes journals in the social sciences, humanities, general science, multicultural studies and education. Dates Covered: 1887 ...

South Africa faces an unusual national election this year, its seventh vote since transitioning from white minority rule to a democracy 30 years ago.