- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Is This the Best One-Volume Biography of Churchill Yet Written?

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Richard Aldous

- Nov. 13, 2018

CHURCHILL Walking With Destiny By Andrew Roberts Illustrated. 1,105 pp. Viking. $40.

In April 1955, on the final weekend before he left office for the last time, Winston Churchill had the vast canvas of Peter Paul Rubens’s “The Lion and the Mouse” taken down from the Great Hall at the prime ministerial retreat of Chequers. He had always found the depiction of the mouse too indistinct, so he retrieved his paint brushes and set about “improving” on the work of Rubens by making the hazy rodent clearer. “If that is not courage,” Lord Mountbatten, the First Sea Lord, said later, “I do not know what is.”

Lack of courage was never Churchill’s problem. As a young man he was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery fighting alongside the Malakand Field Force on the North-West Frontier , and subsequently he took part in the last significant cavalry charge in British history at the Battle of Omdurman in central Sudan . In middle age he served in the trenches of World War I, during which time a German high-explosive shell came in through the roof of his dugout and blew his mess orderly’s head clean off. Later, as prime minister during World War II, and by now in his mid-60s, he thought nothing of visiting bomb sites during the Blitz or crossing the treacherous waters of the Atlantic to see President Roosevelt despite the very real chance of being torpedoed by German U-boats.

Churchill had political courage too, not least as one of the few to oppose the appeasement of Hitler. Many had thought him a warmonger and even a traitor. “I have always felt,” said that scion of the Establishment, Lord Ponsonby, at the time of the Munich debate in 1938, “that in a crisis he is one of the first people who ought to be interned.” Instead, when the moment of supreme crisis came in 1940, the British people turned to him for leadership. Here was his ultimate projection of courage: that Britain would “never surrender.”

If courage was not the issue, lack of judgment often was. Famous military disasters attached to his name, including Antwerp in 1914 , the Dardanelles (Gallipoli) in 1915 and Narvik in 1940 . So too did political controversies, like turning up in person to instruct the police during a violent street battle with anarchists, defying John Maynard Keynes in returning Britain to the gold standard or rashly supporting Edward VIII during the abdication crisis. His views on race and empire were anachronistic even for those times. The carpet bombing of German cities during World War II; the “naughty document” that handed over Romania and Bulgaria to Stalin; comparing the Labour Party to the Gestapo — the list of Churchillian controversies goes on. Each raised questions about his temperament and character. His drinking habits also attracted comment.

Such is the challenge facing any biographer of Churchill: how to weigh in the balance a life filled with so much triumph and disaster, adulation and contempt. The historian Andrew Roberts’s insight about Churchill’s relation to fate in “Churchill: Walking With Destiny” comes directly from the subject himself. “I felt as if I were walking with destiny,” Churchill wrote of that moment in May 1940 when he achieved the highest office. But the story Roberts tells is more sophisticated and in the end more satisfying. “For although he was indeed walking with destiny in May 1940, it was a destiny that he had consciously spent a lifetime shaping,” Roberts writes, adding that Churchill learned from his mistakes, and “put those lessons to use during civilization’s most testing hour.” Experience and reflection on painful failures, while less glamorous than a fate written in the stars, turn out to be the key ingredients in Churchill’s ultimate success.

He did not get off to a particularly happy start. His erratic and narcissistic father, Lord Randolph Churchill, saw the boy as “among the second rate and third rate,” predicting that his life would “degenerate into a shabby, unhappy and futile existence.” His American mother, Jennie, was often not much kinder, sending letters to him at Harrow that must have arrived like a Howler in a Harry Potter novel. Parental judgments became an obvious spur to fame and attention. “Few,” Roberts writes, “have set out with more coldblooded deliberation to become first a hero and then a Great Man.”

After stints in Cuba, India and Sudan, Churchill achieved instant fame during the Boer War after a daring escape from a South African P.O.W. camp in 1899. That renown propelled him into Parliament, where he soon added notoriety to his reputation by crossing the floor of the House of Commons, abandoning the Conservative Party for the Liberals. Thereafter, wrote his friend Violet, daughter of the future prime minister H. H. Asquith, he was viewed as “a rat, a turncoat, an arriviste and, worst crime of all, one who had certainly arrived.” “We are all worms,” Churchill told her. “But I do believe that I am a glowworm.”

And glow he did, becoming in 1908, at 33, the youngest cabinet member in 40 years and subsequently the youngest home secretary since Peel in 1822. As First Lord of the Admiralty he was credited with making the navy ready for war — his single most important achievement in government before 1940. Even when disaster befell him, Churchill always managed to bounce back. A new prime minister, David Lloyd George, returned him to the wartime cabinet despite the catastrophe of the Dardanelles. When the Liberal Party disintegrated after the rise of Labour, Churchill conveniently “re-ratted” back to the Conservatives, where Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin put him unhappily in charge of the nation’s finances.

By the late 1930s, out of office and despised for his opposition to appeasement, Churchill seemed finished once and for all. But he was ready. “The Dardanelles catastrophe taught him not to overrule the Chiefs of Staff,” Roberts writes, “the General Strike and Tonypandy taught him to leave industrial relations during the Second World War to Labour’s Ernest Bevin; the Gold Standard disaster taught him to reflate and keep as much liquidity in the financial system as the exigencies of wartime would allow.”

Less well known is that Churchill also learned from his successes. Cryptographical breakthroughs at the Admiralty during World War I led him to back Alan Turing and the Ultra decrypters in the second war; the anti-U-boat campaign of 1917 instructed him about the convoy system; his earlier advocacy of the tank encouraged him to support the development of new weaponry. Research for a life of Marlborough (a book that Leo Strauss called the greatest historical work of the 20th century) taught Churchill the value of international alliances in wartime.

If Churchill’s entire life was a preparation for 1940, “the man and the moment only just coincided.” He was 65 years old when he became prime minister and had only just re-entered front-line politics after a decade out of office. It would be like Tony Blair returning to 10 Downing Street today, ready to put lessons learned during the Iraq war to work. Had Hitler delayed by a few years, Roberts suggests, Churchill would surely have been away from front-rank politics too long to “make himself the one indispensable figure.”

Experience certainly did not make success inevitable. In France, Marshal Pétain, revered as the “Lion of Verdun” for his glorious career in World War I, made all the wrong decisions as prime minister from June 1940 onward, equating peace with occupation and collaboration.

Churchill was the anti-Pétain, but what was it that made him “indispensable”? Hope, certainly, and an ability to communicate resolve with both clarity and force. Recordings of wartime speeches can still provoke goose bumps. In the end, Roberts sums up Churchill’s overriding achievement in a single sentence: It was “not that he stopped a German invasion … but that he stopped the British government from making a peace.”

That turned out to be the whole ballgame. After the Battle of Britain was won and, first, the Russians and, then, the Americans came into the war, Churchill knew that “time and patience will give certain victory.” But it also meant a gradual relegation to second if not third place. Britain had entered the war as the most prestigious of the world’s great powers. By its conclusion, having lost about a quarter of its national wealth in fighting the war, Britain had become the fraction in the Big Two and a Half, and was effectively bust. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Roberts tells this story with great authority and not a little panache. He writes elegantly, with enjoyable flashes of tartness, and is in complete command both of his sources and the vast historiography. For a book of a thousand pages, there are surprisingly no longueurs . Roberts is admiring of Churchill, but not uncritically so. Often he lays out the various debates before the reader so that we can draw different conclusions to his own. Essentially a conservative realist, he sees political and military controversies through the lens of the art of the possible. Only once does he really bristle, when Churchill says of Stalin in 1945, “I like that man.” “Where was the Churchill of 1931,” he laments, “who had denounced Stalin’s ‘morning’s budget of death warrants’?”

Some may find Roberts’s emphasis on politics and war old-fashioned, indistinguishable, say, from the approach taken almost half a century ago by Henry Pelling. He is out of step with much of the best British history being written today, where the likes of Dominic Sandbrook, Or Rosenboim and John Bew have successfully blended cultural and intellectual history with the study of high politics. But it would be foolish to say Roberts made the wrong choice. He is Thucydidean in viewing decisions about war and politics, politics and war as the crux of the matter. A life defined by politics here rightly gets a political life. All told, it must surely be the best single-volume biography of Churchill yet written.

Richard Aldous, the author of “Reagan and Thatcher” and “Schlesinger,” teaches at Bard.

Official Biography

- The Churchill Documents

- Book Reviews

- Bibliography

- Annotated Bibliography: Works About WSC

- The Churchill Timeline,1874-1977

- Churchill on Palestine, 1945-46

- Road to Israel, 1947-49

- The Art of Winston Churchill Gallery

- Churchill Conference Archive

- Dramatizations

- Documentaries

Winston S. Churchill

by Randolph S. Churchill and Martin Gilbert

“A milestone, a monument, a magisterial achievement… rightly regarded as the most comprehensive life ever written of any age.” —Andrew Roberts, historian and author

“The most scholarly study of Churchill in war and peace ever written.” —Herbert Mitgang, The New York Times

“Confronted with this mighty ocean of narrative, the only possible response is total immersion. The great tidal wave of detail plunges the reader almost involuntarily into Churchill’s life….It is a Churchilliad, and Gilbert is its bard.” —Simon Schama, The New Republic

Volume I, Youth, 1874-1900

This wonderfully readable volume was received with broad praise. Generally positive, though not without criticism, it reflects the theme of the work, “he shall be his own biographer,” but Randolph Churchill adds his own literary style, thoroughly documented with “wonderful grub” provided by his dedicated researchers, including his ultimate successor, Martin Gilbert. The text covers the years from Churchill’s birth in 1874, his education at Harrow and Sandhurst, his early adventures as a war correspondent and sensational escape during the Boer War, his North American lecture tour, and his entry into Parliament. The term “official” does not mean that the biographers were required to stick to an authorized line or avoid certain subjects; rather, that they were allowed unprecedented access to the Churchill archive from which the biography is largely drawn. Buy Now >

Volume II, Young Statesman, 1901-1914

The last volume written by Randolph Churchill traces the story of his father’s entry into Parliament as a Conservative, aged twenty-six. An independent spirit and rebel, Churchill is praised for his maiden speech by the Leader of the Opposition. His lifelong collegiality toward the opposite party is soon in evidence. Finally, in 1904, he breaks with the Conservatives over Free Trade, which he ardently supports. “Crossing the floor” to the Liberals with his usual good timing, Churchill holds increasingly important cabinet positions in the great Liberal governments of 1906-14. The volume details his work as a crusading Home Secretary, his key role in reforming the House of Lords, his advocacy of Irish Home Rule, and his arrival at the Admiralty, where he prepares the Royal Navy for war with Germany. Buy Now >

Volume III, The Challenge of War, 1914-1916

Martin Gilbert, appointed official biographer after Randolph’s death in 1968, now begins an almost day by day chronology of Churchill’s life, concentrating on the first perilous years of World War I. We begin with Churchill leading the Admiralty in early battles with the German fleet, moving to the epic failure of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli campaigns, when Churchill falls from power and is exiled to Belgian trenches as “the escaped scapegoat.” Detailed accounts describe Churchill the warrior, including his efforts to prolong the siege of Antwerp, to develop the expanded use of air power, and to promote his concept for what he calls a “land caterpillar,” soon to be known as the tank. In Flanders, he heads a battalion of Scots Fusiliers—at first unwelcome, later beloved by them all. Buy Now >

Volume IV, World in Torment, 1916-1922

This meticulous account of Churchill’s wide-ranging activities toward the end of World War I and its aftermath displays his persuasive oratory, administrative skill, and masterful leadership. Remarkably, only a few years after the disaster of the Dardanelles, Churchill regains a leading position in British political life. He returns to government as Minister of Munitions, becomes Minister for War and Air, and finally Colonial Secretary. Here we read of his minor role in the Versailles Treaty, his critical work demobilizing the army, and his intervention against the Bolsheviks in Russia. Here too we see his actions over the Chanak Crisis with Turkey, the remaking of the Middle East, and the creation of the Irish Free State, when an Irish patriot wrote: “Tell Winston we could never have done without him.” Buy Now >

Volume V, The Prophet of Truth, 1922-1939

Here is a vivid, intimate picture of Churchill’s public and private life between the wars—eighteen years of triumph and tragedy. He becomes Chancellor of the Exchequer and defends the government during the General Strike. Out of office in 1929, he travels North America, enters a ten year sojourn in the political wilderness, but soon reaches his zenith as a writer. He fights the India Bill, champions Edward VIII in the Abdication crisis, and warns of the threat of Hitler. Martin Gilbert reveals the extent to which senior civil servants and officers risked their careers supplying Churchill with secret information about German rearmament. Finally, war is declared in September 1939 and Churchill becomes First Lord of the Admiralty a quarter century since he last held that post. Buy Now >

Volume VI, Finest Hour, 1939-1941

This precise narrative puts us at Churchill’s shoulder during the most critical years of his life and the world’s, starting with the outbreak of war in September 1939 and ending with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Martin Gilbert unfolds the early events of World War II: Hitler’s supreme triumph on the continent, Britain’s victories in the air, the London Blitz, the U-boat war, Hitler’s attack on Russia, Churchill’s first personal contact with Roosevelt at the Atlantic Charter conference in August 1941, Pearl Harbor, and the forging of the “Grand Alliance.” In Churchill’s crucial meetings with FDR, Gilbert shows not only how each decision was reached, but what influences lay behind it, carefully developing an intimate account of a unique—if not wholly untroubled—relationship between the two great allies. Buy Now >

Volume VII, Road to Victory, 1941-1945

This volume runs from the Japanese attack on Hawaii and British Asia in 1941 through V-E Day and beyond to the end of World War II. From the nadir of the war we observe the turning of “the Hinge of Fate,” the battles of Alamein and Stalingrad, the invasions of North Africa, Italy, and finally France. We are there for the great summit conferences, from Moscow in 1942 (“like carrying a large lump of ice to the North Pole”) to Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam. We witness Churchill’s reaction to the waxing of American and Soviet power, the ring closing around Germany, arguments over invasion routes, the death of Hitler, growing concerns about postwar Soviet expansion, the atomic bomb, and the fateful British election that cost the prime minister his job. Buy Now >

Volume VIII, Never Despair, 1945-1965

The final volume covers Churchill’s last twenty years, starting with his role as a scintillating Leader of the Opposition (1945-51). We witness his great speeches of resolve and reconciliation at Fulton, Zurich, and The Hague, his efforts for “a final settlement” with the Soviets, and Eisenhower’s determined resistance. We follow Churchill’s return to the premiership (1951-55), his last efforts to secure permanent peace, his resignation, his final words to his colleagues, his declining years, and his death—seventy years almost to the hour of his father’s passing in 1895. Included is the full text of “The Dream,” Churchill’s imagined encounter with his father’s ghost, when he describes all that has happened since 1895—never revealing the role Winston himself played. Buy Now >

History of the Official Biography

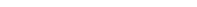

February 1932

Randolph Churchill asks his father for permission to write his biography. Winston says wait.

Winston Churchill writes his son Randolph: “I have reflected carefully on what you said. I think that your biography of Derby is a remarkable work, and I should be happy that you should write my official biography when the time comes.”

October 25, 1962

Martin Gilbert is hired by Randolph Churchill to serve as one of his research assistants.

Randolph Churchill publishes the first narrative volume of the official biography, Winston S. Churchill: Youth, 1874-1900.

Randolph Churchill dies aged only 57.

October 1968

Martin Gilbert is selected to succeed the late Randolph Churchill as the official biographer.

Larry Arnn begins working on the official biography as Sir Martin’s research assistant.

Martin Gilbert publishes the eighth and final narrative volume of the official biography, Winston S. Churchill: Never Despair, 1945-1965.

The document volumes, which had ceased appearing in 1982 after The Coming of War 1936-1939, resume publication as The Churchill War Papers, thanks to the kind generosity of Wendy Reves.

Martin Gilbert accepts a position with Hillsdale College as the William and Berniece Grewcock Distinguished Fellow.

Hillsdale College becomes the publisher of the official biography and undertakes to return every previous volume to print along with the still-unpublished document volumes covering 1942-1965.

The first Hillsdale editions are published, comprising Volume I, Youth 1874-1900, together with its two document volumes. Henceforth, the document volumes will be numbered sequentially.

After forty-four years as official biographer, Martin Gilbert falls ill and is unable to continue his work.

Hillsdale’s document volumes reach Vol. 17, Testing Times, 1942—the first new set of documents in thirteen years.

February 2015

Sir Martin Gilbert passes away aged 78.

Larry Arnn edits and publishes The Churchill Documents: Volume 18, One Continent Redeemed, January –August 1943 as a continuation of Martin Gilbert’s work.

October 2016

Volume 19, Fateful Question, September 1943 to April 1944, is published. At over 2,700 pages, it is the longest volume to date.

February 2018

Volume 20, Normandy and Beyond, May-December 1944, is published.

September 2018

Volume 21, The Shadows of Victory, January-July 1945, is published.

August 2019

Volume 22, Leader of the Opposition, August 1945 to October 1951, is published.

Volume 23, Never Flinch, Never Weary, November 1951 to February 1965, is published, thus completing the publication of the Official Biography.

Stay In Touch With Us

Subscribe now and receive weekly newsletters with educational materials, new courses, interesting posts, popular books, and much more!

YOUR EMAIL ADDRESS

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Winston Churchill

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 7, 2019 | Original: October 27, 2009

Winston Churchill was one of the best-known, and some say one of the greatest, statesmen of the 20th century. Though he was born into a life of privilege, he dedicated himself to public service. His legacy is a complicated one: He was an idealist and a pragmatist; an orator and a soldier; an advocate of progressive social reforms and an unapologetic elitist; a defender of democracy – especially during World War II – as well as of Britain’s fading empire. But for many people in Great Britain and elsewhere, Winston Churchill is simply a hero.

Winston Churchill came from a long line of English aristocrat-politicians. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was descended from the First Duke of Marlborough and was himself a well-known figure in Tory politics in the 1870s and 1880s.

His mother, born Jennie Jerome, was an American heiress whose father was a stock speculator and part-owner of The New York Times. (Rich American girls like Jerome who married European noblemen were known as “dollar princesses.”)

Did you know? Sir Winston Churchill won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953 for his six-volume history of World War II.

Churchill was born at the family’s estate near Oxford on November 30, 1874. He was educated at the Harrow prep school, where he performed so poorly that he did not even bother to apply to Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, in 1893 young Winston Churchill headed off to military school at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Battles and Books

After he left Sandhurst, Churchill traveled all around the British Empire as a soldier and as a journalist. In 1896, he went to India; his first book, published in 1898, was an account of his experiences in India’s Northwest Frontier Province.

In 1899, the London Morning Post sent him to cover the Boer War in South Africa, but he was captured by enemy soldiers almost as soon as he arrived. (News of Churchill’s daring escape through a bathroom window made him a minor celebrity back home in Britain.)

By the time he returned to England in 1900, the 26-year-old Churchill had published five books.

Churchill: “Crossing the Chamber”

That same year, Winston Churchill joined the House of Commons as a Conservative. Four years later, he “crossed the chamber” and became a Liberal.

His work on behalf of progressive social reforms such as an eight-hour workday, a government-mandated minimum wage, a state-run labor exchange for unemployed workers and a system of public health insurance infuriated his Conservative colleagues, who complained that this new Churchill was a traitor to his class.

Churchill and Gallipoli

In 1911, Churchill turned his attention away from domestic politics when he became the First Lord of the Admiralty (akin to the Secretary of the Navy in the U.S.). Noting that Germany was growing more and more bellicose, Churchill began to prepare Great Britain for war: He established the Royal Naval Air Service, modernized the British fleet and helped invent one of the earliest tanks.

Despite Churchill’s prescience and preparation, World War I was a stalemate from the start. In an attempt to shake things up, Churchill proposed a military campaign that soon dissolved into disaster: the 1915 invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey.

Churchill hoped that this offensive would drive Turkey out of the war and encourage the Balkan states to join the Allies, but Turkish resistance was much stiffer than he had anticipated. After nine months and 250,000 casualties, the Allies withdrew in disgrace.

After the debacle at Gallipoli, Churchill left the Admiralty.

Churchill Between the Wars

During the 1920s and 1930s, Churchill bounced from government job to government job, and in 1924 he rejoined the Conservatives. Especially after the Nazis came to power in 1933, Churchill spent a great deal of time warning his countrymen about the perils of German nationalism, but Britons were weary of war and reluctant to get involved in international affairs again.

Likewise, the British government ignored Churchill’s warnings and did all it could to stay out of Hitler’s way. In 1938, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain even signed an agreement giving Germany a chunk of Czechoslovakia – “throwing a small state to the wolves,” Churchill scolded – in exchange for a promise of peace.

A year later, however, Hitler broke his promise and invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war. Chamberlain was pushed out of office, and Winston Churchill took his place as prime minister in May 1940.

Churchill: The “British Bulldog”

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat,” Churchill told the House of Commons in his first speech as prime minister.

“We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I can say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.”

Just as Churchill predicted, the road to victory in World War II was long and difficult: France fell to the Nazis in June 1940. In July, German fighter planes began three months of devastating air raids on Britain herself.

Though the future looked grim, Churchill did all he could to keep British spirits high. He gave stirring speeches in Parliament and on the radio. He persuaded U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide war supplies – ammunition, guns, tanks, planes – to the Allies, a program known as Lend-Lease, before the Americans even entered the war.

Though Churchill was one of the chief architects of the Allied victory, war-weary British voters ousted the Conservatives and their prime minister from office just two months after Germany’s surrender in 1945.

The Iron Curtain

The now-former prime minister spent the next several years warning Britons and Americans about the dangers of Soviet expansionism.

In a speech in Fulton, Missouri , in 1946, for example, Churchill declared that an anti-democratic “Iron Curtain,” “a growing challenge and peril to Christian civilization,” had descended across Europe. Churchill’s speech was the first time anyone had used that now-common phrase to describe the Communist threat.

In 1951, 77-year-old Winston Churchill became prime minister for the second time. He spent most of this term working (unsuccessfully) to build a sustainable détente between the East and the West. He retired from the post in 1955.

In 1953, Queen Elizabeth made Winston Churchill a knight of the Order of the Garter. He died in 1965, one year after retiring from Parliament.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Winston Churchill

(1874-1965)

Who Was Winston Churchill?

Early years.

Churchill was born on November 30, 1874, at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, England.

From an early age, young Churchill displayed the traits of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, a British statesman from an established English family, and his mother, Jeanette "Jennie" Jerome, an independent-minded New York socialite.

Churchill grew up in Dublin, Ireland, where his father was employed by his grandfather, the 7th Duke of Marlborough, John Spencer-Churchill.

Churchill proved to be an independent and rebellious student; after performing poorly at his first two schools, Churchill in April 1888 began attending Harrow School, a boarding school near London. Within weeks of his enrollment, he joined the Harrow Rifle Corps, putting him on a path to a military career.

At first, it didn't seem the military was a good choice for Churchill; it took him three tries to pass the exam for the British Royal Military College. However, once there, he fared well and graduated 20th in his class of 130.

Up to this time, his relationship with both his mother and father was distant, though he adored them both. While at school, Churchill wrote emotional letters to his mother, begging her to come see him, but she seldom came.

His father died when he was 21, and it was said that Churchill knew him more by reputation than by any close relationship they shared.

Military Career

Churchill enjoyed a brief but eventful career in the British Army at a zenith of British military power. He joined the Fourth Queen's Own Hussars in 1895 and served in the Indian northwest frontier and the Sudan, where he saw action in the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.

While in the Army, he wrote military reports for the Pioneer Mail and the Daily Telegraph , and two books on his experiences, The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898) and The River War (1899).

In 1899, Churchill left the Army and worked as a war correspondent for the Morning Post , a conservative daily newspaper. While reporting on the Boer War in South Africa, he was taken prisoner by the Boers during a scouting expedition.

He made headlines when he escaped, traveling almost 300 miles to Portuguese territory in Mozambique. Upon his return to Britain, he wrote about his experiences in the book London to Ladysmith via Pretoria (1900).

Parliament and Cabinet

In 1900, Churchill became a member of the British Parliament in the Conservative Party for Oldham, a town in Manchester. Following his father into politics, he also followed his father's sense of independence, becoming a supporter of social reform.

Unconvinced that the Conservative Party was committed to social justice, Churchill switched to the Liberal Party in 1904. He was elected a member of Parliament in 1908 and was appointed to the prime minister's cabinet as president of the Board of Trade.

As president of the Board of Trade, Churchill joined newly appointed Chancellor David Lloyd George in opposing the expansion of the British Navy. He introduced several reforms for the prison system, introduced the first minimum wage and helped set up labor exchanges and unemployment insurance.

Churchill also assisted in the passing of the People's Budget, which introduced taxes on the wealthy to pay for new social welfare programs. The budget passed in the House of Commons in 1909 and was initially defeated in the House of Lords before being passed in 1910.

In January 1911, Churchill showed his tougher side when he made a controversial visit to a police siege in London, with two alleged robbers holed up in a building.

Churchill's degree of participation is still in some dispute: Some accounts have him going to the scene only to see for himself what was going on; others state that he allegedly gave directions to police on how to best storm the building.

What is known is that the house caught fire during the siege and Churchill prevented the fire brigade from extinguishing the flames, stating that he thought it better to "let the house burn down," rather than risk lives rescuing the occupants. The bodies of the two robbers were later found inside the charred ruins.

Wife and Children

In 1908, Winston Churchill married Clementine Ogilvy Hozier after a short courtship.

The couple had five children together: Diana, Randolph, Sarah, Marigold (who died as a toddler of tonsillitis) and Mary.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S WINSTON CHURCHILL FACT CARD

First Lord of the Admiralty

Named First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911, Churchill helped modernize the British Navy, ordering that new warships be built with oil-fired instead of coal-fired engines.

He was one of the first to promote military aircraft and set up the Royal Navy Air Service. He was so enthusiastic about aviation that he took flying lessons himself to understand firsthand its military potential.

Churchill also drafted a controversial piece of legislation to amend the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913, mandating sterilization of the feeble-minded. The bill, which mandated only the remedy of confinement in institutions, eventually passed in both houses of Parliament.

World War I

Churchill remained in his post as First Lord of the Admiralty through the start of World War I , but was forced out for his part in the disastrous Battle of Gallipoli . He resigned from the government toward the end of 1915.

For a brief period, Churchill rejoined the British Army, commanding a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front and seeing action in "no man's land."

In 1917, he was appointed minister of munitions for the final year of the war, overseeing the production of tanks, airplanes and munitions.

After World War I

From 1919 to 1922, Churchill served as minister of war and air and colonial secretary under Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

As colonial secretary, Churchill was embroiled in another controversy when he ordered air power to be used on rebellious Kurdish tribesmen in Iraq, a British territory. At one point, he suggested that poisonous gas be used to put down the rebellion, a proposal that was considered but never enacted.

Fractures in the Liberal Party led to the defeat of Churchill as a member of Parliament in 1922, and he rejoined the Conservative Party. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, returning Britain to the gold standard, and took a hard line against a general labor strike that threatened to cripple the British economy.

With the defeat of the Conservative government in 1929, Churchill was out of government. He was perceived as a right-wing extremist, out of touch with the people.

In the 1920s, after his ouster from government, Churchill took up painting. “Painting came to my rescue in a most trying time,” he later wrote.

Churchill went on to create over 500 paintings, typically working en plein air , though also practicing with still lifes and portraits. He claimed that painting helped him with his powers of observation and memory.

Sutherland Portrait

Churchill himself was the subject of a famous - and famously controversial - portrait by renowned artist Graham Sutherland.

Commissioned in 1954 by members of Parliament to mark Churchill's 80th birthday, the portrait was first unveiled in a public ceremony in Westminster Hall, where it met with considerable derision and laughter.

The unflattering modernist painting was reportedly loathed by Churchill and members of his family. Churchill's wife Clementine had the Sutherland portrait secretly destroyed in a bonfire several months after it was delivered to their country estate, Chartwell , in Kent.

'Wilderness Years'

Through the 1930s, known as his "wilderness years," Churchill concentrated on his writing, publishing a memoir and a biography of the First Duke of Marlborough.

During this time, he also began work on his celebrated A History of the English-Speaking Peoples , though it wouldn't be published for another two decades.

As activists in 1930s India clamored for independence from British rule, Churchill cast his lot with opponents of independence. He held particular scorn for Mahatma Gandhi , stating that "it is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer ... striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace ... to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor."

- World War II

Although Churchill didn't initially see the threat posed by Adolf Hitler 's rise to power in the 1930s, he gradually became a leading advocate for British rearmament.

By 1938, as Germany began controlling its neighbors, Churchill had become a staunch critic of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain 's policy of appeasement toward the Nazis.

On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, Churchill was again appointed First Lord of the Admiralty and a member of the war cabinet; by April 1940, he became chairman of the Military Coordinating Committee.

Later that month, Germany invaded and occupied Norway, a setback for Chamberlain, who had resisted Churchill's proposal that Britain preempt German aggression by unilaterally occupying vital Norwegian iron mines and seaports.

Prime Minister

On May 10, 1940, Chamberlain resigned and King George VI appointed Churchill as prime minister and minister of defense.

Within hours, the German army began its Western Offensive, invading the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Two days later, German forces entered France. As clouds of war darkened over Europe, Britain stood alone against the onslaught.

Churchill was to serve as prime minister of Great Britain from 1940 to 1945, leading the country through World War II until Germany’s surrender.

Battle of Britain

Quickly, Churchill formed a coalition cabinet of leaders from the Labor, Liberal and Conservative parties. He placed intelligent and talented men in key positions.

On June 18, 1940, Churchill made one of his iconic speeches to the House of Commons, warning that "the Battle of Britain " was about to begin. Churchill kept resistance to Nazi dominance alive and created the foundation for an alliance with the United States and the Soviet Union.

Churchill had previously cultivated a relationship with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, and by March 1941, he was able to secure vital U.S. aid through the Lend Lease Act , which allowed Britain to order war goods from the United States on credit.

After the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Churchill was confident that the Allies would eventually win the war. In the months that followed, Churchill worked closely with Roosevelt and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to forge an Allied war strategy and postwar world.

In a meeting in Tehran (1943), at the Yalta Conference (1945) and the Potsdam Conference (1945), Churchill collaborated with the two leaders to develop a united strategy against the Axis Powers and helped craft the postwar world with the United Nations as its centerpiece.

As the war wound down, Churchill proposed plans for social reforms in Britain but was unable to convince the public. Despite Germany's surrender on May 7, 1945, Churchill was defeated in the general election in July 1945.

'Iron Curtain' Speech

In the six years after Churchill’s defeat, he became the leader of the opposition party and continued to have an impact on world affairs.

In March 1946, while on a visit to the United States, he made his famous "Iron Curtain" speech , warning of Soviet domination in Eastern Europe. He also advocated that Britain remain independent from European coalitions.

With the general election of 1951, Churchill returned to government. He became prime minister for the second time in October 1951 and served as minister of defense between October 1951 and March 1952.

Churchill went on to introduce reforms such as the Mines and Quarries Act of 1954, which improved working conditions in mines, and the Housing Repairs and Rent Act of 1955, which established standards for housing.

These domestic reforms were overshadowed by a series of foreign policy crises in the colonies of Kenya and Malaya, where Churchill ordered direct military action. While successful in putting down the rebellions, it became clear that Britain was no longer able to sustain its colonial rule.

Nobel Prize

In 1953, Churchill was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II .

The same year, he was named the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature for "his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values," according to the Nobel Prize committee.

Churchill died on January 24, 1965, at age 90, in his London home nine days after suffering a severe stroke. Britain mourned for more than a week.

Churchill had shown signs of fragile health as early as 1941 when he suffered a heart attack while visiting the White House. Two years later, he had a similar attack while battling a bout of pneumonia.

In June 1953, at age 78, he endured a series of strokes at his office. That particular news was kept from the public and Parliament, with the official announcement stating that he had suffered from exhaustion.

Churchill recuperated at home and returned to his work as prime minister in October. However, it was apparent even to the great statesman that he was physically and mentally slowing down, and he retired as prime minister in 1955. Churchill remained a member of Parliament until the general election of 1964 when he did not seek reelection.

There was speculation that Churchill suffered from Alzheimer's disease in his final years, though medical experts pointed to his earlier strokes as the likely cause of reduced mental capacity.

Despite his poor health, Churchill was able to remain active in public life, albeit mostly from the comfort of his homes in Kent and Hyde Park Gate in London.

As with other influential world leaders, Churchill left behind a complicated legacy.

Honored by his countrymen for defeating the dark regime of Hitler and the Nazi Party , he topped the list of greatest Britons of all time in a 2002 BBC poll, outlasting other luminaries like Charles Darwin and William Shakespeare .

To critics, his steadfast commitment to British imperialism and his withering opposition to independence for India underscored his disdain for other races and cultures.

Churchill Movies and Books

Churchill has been the subject of numerous portrayals on the big and small screen over the years, with actors from Richard Burton to Christian Slater taking a crack at capturing his essence. John Lithgow delivered an acclaimed performance as Churchill in the Netflix series The Crown , winning an Emmy for his work in 2017.

That year also brought the release of two biopics: In June, Brian Cox starred in the titular role of Churchill , about the events leading up to the World War II invasion of Normandy. Gary Oldman took his turn by undergoing an eye-popping physical transformation to become the iconic statesman in Darkest Hour .

Churchill's standing as a towering figure of the 20th century is such that his two major biographies required multiple authors and decades of research between volumes. William Manchester published volume 1 of The Last Lion in 1983 and volume 2 in 1986, but died while working on part 3; it was finally completed by Paul Reid in 2012.

The official biography, Winston S. Churchill , was begun by the former prime minister's son Randolph in the early 1960s; it passed on to Martin Gilbert in 1968, and then into the hands of an American institution, Hillsdale College , some three decades later. In 2015, Hillsdale published volume 18 of the series.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Winston Churchill

- Birth Year: 1874

- Birth date: November 30, 1874

- Birth City: Blenheim Palace, Woodstock

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Winston Churchill was a British military leader and statesman. Twice named prime minister of Great Britain, he helped to defeat Nazi Germany in World War II.

- World Politics

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Harrow School

- Brunswick School

- Royal Military College (Academy) at Sandhurst

- St. George's School

- Interesting Facts

- Winston Churchill was a prolific writer and author and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953.

- Churchill was a son of a British statesman father and an American socialite mother.

- In 1963 President JFK bestowed Churchill honorary U.S. citizenship, the first time a president gave such an award to a foreign national.

- Death Year: 1965

- Death date: January 24, 1965

- Death City: Hyde Park Gate, London

- Death Country: England

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Winston Churchill Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/winston-churchill

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: January 22, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last.

- I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.

- Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

- A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.

- Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities ... because it is the quality which guarantees all others.

- From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.

Famous British People

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Quick Links

Sir winston churchill: a biography, the aim of this page is to give a brief introduction to the career of sir winston churchill, and to reveal the main features of both the public and the private life of the most famous british prime minister of the twentieth century..

Winston Churchill was born into the privileged world of the British aristocracy on November 30, 1874. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was a younger son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough. His mother, Jennie Jerome, was the daughter of an American business tycoon, Leonard Jerome.

Winston’s childhood was not a particularly happy one. Like many Victorian parents, Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill were distant. The family Nanny, Mrs Everest, became a surrogate mother to Winston and his younger brother, John S Churchill.

The Soldier

After passing out of Sandhurst and gaining his commission in the 4th Hussars’ in February 1895, Churchill saw his first shots fired in anger during a semi-official expedition to Cuba later that year. He enjoyed the experience which coincided with his 21st birthday.

In 1897 Churchill saw more action on the North West Frontier of India, fighting against the Pathans. He rode his grey pony along the skirmish lines in full view of the enemy. “Foolish perhaps,” he told his mother, ” but I play for high stakes and given an audience there is no act too daring and too noble.” Churchill wrote about his experiences in his first book The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898). He soon became an accomplished war reporter, getting paid large sums for stories he sent to the press – something which did not make him popular with his senior officers.

Using his mother’s influence, Churchill got himself assigned to Kitchener’s army in Egypt. While fighting against the Dervishes he took part in the last great cavalry charge in English history – at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.

The Politician

Churchill was first elected to parliament in 1900 shortly before the death of Queen Victoria. He took his seat in the House of Commons as the Conservative Member for Oldham in February 1901 and made his maiden speech four days later. But after only four years as a Conservative he crossed the floor and joined the Liberals, making the flamboyant gesture of sitting next to one of the leading radicals, David Lloyd George.

Churchill rose swiftly within the Liberal ranks and became a Cabinet Minister in 1908 – President of the Board of Trade. In this capacity and as Home Secretary (1910-11) he helped to lay the foundations of the post-1945 welfare state.

His parliamentary career was far from being plain sailing and he made a number of spectacular blunders, so much so that he was often accused of having genius without judgement. The chief setback of his career occurred in 1915 when, as First Lord of the Admiralty, he sent a naval force to the Dardanelles in an attempt to knock Turkey out of the war and to outflank Germany on a continental scale. The expedition was a disaster and it marked the lowest point in Churchill’s fortunes.

However, Churchill could not be kept out of power for long and Lloyd George, anxious to draw on his talents and to spike his critical guns, soon re-appointed him to high office. Their relationship was not always a comfortable one, particularly when Churchill tried to involve Britain in a crusade against the Bolsheviks in Russia after the Great War.

Between 1922 and 1924 Churchill left the Liberal Party and, after some hesitation, rejoined the Conservatives. Anyone could “rat”, he remarked complacently, but it took a certain ingenuity to “re-rat”. To his surprise, Churchill was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer by Stanley Baldwin, an office in which he served from 1924 to 1929. He was an ebullient if increasingly anachronistic figure, returning Britain to the Gold Standard and taking an aggressive part in opposing the General Strike of 1926.

After the Tories were defeated in 1929, Churchill fell out with Baldwin over the question of giving India further self-government. Churchill became more and more isolated in politics and he found the experience of perpetual opposition deeply frustrating. He also made further blunders, notably by supporting King Edward VIII during the abdication crisis of 1936. Largely as a consequence of such errors, people did not heed Churchill’s dire warnings about the rise of Hitler and the hopelessness of the appeasement policy. After the Munich crisis, however, Churchill’s prophecies were seen to be coming true and when war broke out in September 1939 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain appointed him First Lord of the Admiralty. So, nearly twenty-five years after he had left the post in pain and sorrow, the Navy sent out a signal to the Fleet: “Winston is back”.

The War Leader

For the first nine months of the conflict, Churchill proved that he was, as Admiral Fisher had once said, “a war man”. Chamberlain was not. Consequently the failures of the Norwegian Campaign were blamed on the pacific Prime Minister rather than the belligerent First Lord, and, when Chamberlain resigned after criticisms in the House of Commons, Churchill became leader of a coalition government. The date was May 10, 1940: it was Churchill’s, as well as Britain’s, finest hour.

When the German armies conquered France and Britain faced the Blitz, Churchill embodied his country’s will to resist. His oratory proved an inspiration. When asked exactly what Churchill did to win the war, Clement Attlee, the Labour leader who served in the coalition government, replied: “Talk about it.” Churchill talked incessantly, in private as well as in public – to the astonishment of his private secretary, Jock Colville, he once spent an entire luncheon addressing himself exclusively to the marmalade cat.

Churchill devoted much of his energy to trying to persuade President Roosevelt to support him in the war. He wrote the President copious letters and established a strong personal relationship with him. And he managed to get American help in the Atlantic, where until 1943 Britain’s lifeline to the New World was always under severe threat from German U-Boats.

Despite Churchill’s championship of Edward VIII, and despite his habit of arriving late for meetings with the neurotically punctual King at Buckingham Palace, he achieved good relations with George VI and his family. Clementine once said that Winston was the last surviving believer in the divine right of kings.

As Churchill tried to forge an alliance with the United States, Hitler made him the gift of another powerful ally – the Soviet Union. Despite his intense hatred of the Communists, Churchill had no hesitation in sending aid to Russia and defending Stalin in public. “If Hitler invaded Hell,” he once remarked, “I would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.”

In December 1941, six months after Hitler had invaded Russia, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The war had now become a global one. But with the might of America on the Allied side there could be no doubt about its outcome. Churchill was jubilant, remarking when he heard the news of Pearl Harbor: “So we have won after all!”

However, America’s entry into the war also caused Churchill problems; as he said, the only thing worse than fighting a war with allies is fighting a war without them. At first, despite disasters such as the Japanese capture of Singapore early in 1942, Churchill was able to influence the Americans. He persuaded Roosevelt to fight Germany before Japan, and to follow the British strategy of trying to slit open the “soft underbelly” of Europe. This involved the invasions of North Africa, Sicily, and Italy – the last of which proved to have a very well armoured belly.

It soon became apparent that Churchill was the littlest of the “Big Three”. At the Teheran Conference in November, 1943, he said, the “poor little English donkey” was squeezed between the great Russian bear and the mighty American buffalo, yet only he knew the way home.

In June 1944 the Allies invaded Normandy and the Americans were clearly in command. General Eisenhower pushed across Northern Europe on a broad front. Germany was crushed between this advance and the Russian steamroller. On May 8, 1945 Britain accepted Germany’s surrender and celebrated Victory in Europe Day. Churchill told a huge crowd in Whitehall: “This is your victory.” The people shouted: “No, it is yours”, and Churchill conducted them in the singing of Land of Hope and Glory. That evening he broadcast to the nation urging the defeat of Japan and paying fulsome homage to the Crown.

From all over the world Churchill received telegrams of congratulations, and he himself was generous with plaudits, writing warmly to General de Gaulle whom he regarded as an awkward ally but a bastion against French Communism. But although victory was widely celebrated throughout Britain, the war in the Far East had a further three months to run. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki finally brought the global conflict to a conclusion. But at the pinnacle of military victory, Churchill tasted the bitterness of political defeat.

The Elder Statesman

Churchill expected to win the election of 1945. Everything pointed to his victory, from the primitive opinion polls to the cartoons in newspapers and the adulation Churchill received during the campaign, but he did not conduct it well. From the start he accused the Labour leaders – his former colleagues – of putting party before country and he later said that Socialists could not rule without a political police, a Gestapo. As it happened, such gaffes probably made no difference. The political tide was running against the Tories and towards the party which wholeheartedly favoured a welfare state – the reward for war-time sacrifices. But Churchill was shocked by the scale of his defeat. When Clementine, who wanted him to retire from politics, said that it was perhaps a blessing in disguise, Churchill replied that the blessing was certainly very effectively disguised. For a time he lapsed into depression, which sympathetic letters from friends did little to dispel.

Soon, however, Churchill re-entered the political arena, taking an active part in political life from the opposition benches and broadcasting again to the nation after the victory over Japan. In defeat Churchill had always been defiant, but in victory he favoured magnanimity. Within a couple of years he was calling for a partnership between a “spiritually great France and a spiritually great Germany” as the basis for the re-creation of “the European family”. He was more equivocal about Britain’s role in his proposed “United States of Europe”, and, while the embers of the World War II were still warm, he announced the start of the Cold War. At Fulton, Missouri, in 1946, he pointed to the new threat posed by the Soviet Union and declared that an iron curtain had descended across Europe. Only by keeping the alliance between the English-speaking peoples strong, he maintained, could Communist tyranny be resisted.

After losing another election in 1950, Churchill gained victory at the polls the following year. Publicly he called for “several years of quiet steady administration”. Privately he declared that his policy was “houses, red meat and not getting scuppered”. This he achieved. But after suffering a stroke and the failure of his last hope of arranging a Summit with the Russians, he resigned from the premiership in April 1955.

“I am ready to meet my Maker,” Churchill had said on his seventy-fifth birthday; “whether my Maker is prepared for the great ordeal of meeting me is another matter”. Churchill remained a member of parliament, though an inactive one, and announced his retirement from politics in 1963. This took effect at the general election the following year. Churchill died on 24 January 1965 – seventy years to the day after the death of his father. He received the greatest state funeral given to a commoner since that of the Duke of Wellington. He was buried in Bladon churchyard beside his parents and within sight of his birthplace, Blenheim Palace.

The Family Man

In the autumn of 1908 Churchill, then a rising Liberal politician, married Clementine Hozier, granddaughter of the 10th Earl of Airlie. Their marriage was to prove a long and happy one, though there were often quarrels – Clementine once threw a dish of spinach at Winston (it missed). Clementine was high principled and highly strung; Winston was stubborn and ambitious. His work invariably came first, though, partly as a reaction against his own upbringing, he was devoted to his children.

Winston and Clementine’s first child, Diana, was born in 1909. Diana was a naughty little girl and continued to cause her parents great distress as an adult. In 1932 she married John Bailey, but the marriage was unsuccessful and they divorced in 1935. In that year she married the Conservative politician, Duncan Sandys, and they had three children. That marriage also proved a failure. Diana had several nervous breakdowns and in 1963 she committed suicide.

The Churchills’ second child and only son, Randolph, was born in 1911. He was exceptionally handsome and rumbustious, and his father was very ambitious for him. During the 1930s Randolph stood for parliament several times but he failed to get in, being regarded as a political maverick. He did serve as Conservative Member of Parliament for Preston between 1940 and 1945, and ultimately became an extremely successful journalist and began the official biography of his father during the 1960s.

Randolph was married twice, first in 1939 to Pamela Digby (later Harriman) by whom he had a son, Winston, and secondly in 1948 to June Osborne by whom he had a daughter, Arabella. Neither marriage was a success.

The life of Sarah, the Churchills’ third child, born in 1914, was no happier than that of her elder siblings. Amateur dramatics at Chartwell led her to take up a career on the stage which flourished for a time. Sarah’s charm and vitality were also apparent in her private life, but her first two marriages proved unsuccessful and she was widowed soon after her third. Her first husband was a music hall artist called Vic Oliver whom she married against her parents’ wishes. Her second was Anthony Beauchamp but this marriage did not last and after their separation he committed suicide.

In 1918 Clementine Churchill gave birth to a third girl, Marigold. But in 1921, shortly after the deaths of both Clementine’s brother and Winston’s mother, Marigold contracted septicaemia whilst on a seaside holiday with the childrens’ governess. When she died Winston was grief-stricken and, as his last private secretary recently disclosed in an autobiography, Clementine screamed like an animal undergoing torture.

The following September the Churchills’ fifth and last child, Mary, was born. Unlike her brother and older sisters, Mary was to cause her parents no major worries. Indeed she was a constant source of support, especially to her mother. In 1947 she married Christopher Soames; who was then Assistant Military Attaché in Paris and later had a successful parliamentary and diplomatic career. Theirs was to be a long and happy marriage. Over the years Christopher became a valued confidant and counsellor to his father-in-law. They had five children, the eldest of whom (Nicholas) became a prominent member of the Conservative party. Christopher Soames died in 1987.

The Private Man

Churchill’s enormous reserves of energy and his legendary ability to exist on very little sleep gave him time to pursue a wide variety of interests outside the world of politics.

Churchill loved gambling and lost what was, for him, a small fortune in the great crash of the American stock market in October 1929, causing a severe setback to the family finances. But he continued to write as a means of maintaining the style of life to which he had always been accustomed. Apart from his major works, notably his multi-volume histories of the First and Second World Wars and the Life of his illustrious ancestor John, first Duke of Marlborough, he poured forth speeches and articles for newspapers and magazines. His last big book was the History of the English-Speaking Peoples, which he had begun in 1938 and which was eventually published in the 1950s. In 1953 Churchill was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Churchill took up painting as an antidote to the anguish he felt over the Dardanelles disaster. Painting became a constant solace and preoccupation and he rarely spent a few days away from home without taking his canvas and brushes. Even during his tour of France’s Maginot Line in the middle of August 1939 Churchill managed to snatch a painting holiday with friends near Dreux.

In the summer of 1922, while on the lookout for a suitable country house, Churchill caught sight of a property near Westerham in Kent, and fell instantly in love with it. Despite Clementine’s initial lack of enthusiasm for the dilapidated and neglected house, with its overgrown and seemingly unmanageable grounds, Chartwell was to become a much-loved family home. Clementine, however, never quite overcame her resentment of the fact that Winston had been less than frank with her over the buying of Chartwell, and from time to time her feelings surfaced.

With typical enthusiasm, Churchill personally undertook many major works of construction at Chartwell such as a dam, a swimming pool, the building (largely with his own hands) of a red brick wall to surround the vegetable garden, and the re-tiling of a cottage at the bottom of the garden. In 1946 Churchill bought a farm adjoining Chartwell and subsequently derived much pleasure, though little profit, from farming.

Churchill was born into the world of hunting, shooting and fishing and throughout his life they were to prove spasmodic distractions. But it was hunting and polo, first learned as a young cavalry officer in India, that he enjoyed most of all.

In the summer of 1949, Churchill embarked on a new venture – he bought a racehorse. On the advice of Christopher Soames, he purchased a grey three-year-old colt, Colonist II. It was to be the first of several thoroughbreds in his small stud. They were registered in Lord Randolph’s colours – pink with chocolate sleeves and cap. (These have been adopted as the colours of Churchill College.) Churchill was made a member of the Jockey Club in 1950, and greatly relished the distinction.

Among Winston’s closest friends were Professor Lindemann and the “the three B’s” (none popular with Clementine), Birkenhead, Beaverbook, Bracken. The Churchills entertained widely, including among their guests Charlie Chaplin, Albert Einstein and Lawrence of Arabia. Churchill regularly holidayed with rich friends in the Mediterranean, spending several cruises in the late 1950s as the guest of Greek millionaire shipowner, Aristotle Onassis.

Editorial note

Much of the information presented here was originally compiled by Josephine Sykes, Monica Halpin and Victor Brown. It was edited by Allen Packwood.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Paul Addison's top 10 books on Churchill

Paul Addison is director of the centre for second world war studies at the University of Edinburgh. He is a former visiting fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, and the author of Churchill: The Unexpected Hero recently published by Oxford University Press.

1 My Early Life by Winston Churchill

My top 10 have not been arranged in order of merit - but if they had been, this would still be number one. The best source on the making of Winston Churchill is still Churchill himself. Written in late middle age, his autobiography recalled his unhappy childhood and his youthful quest for glory as a soldier and war correspondent. A classic adventure story, it was also a lament for a vanished age of aristocracy and empire.

2. Churchill: Four Faces and the Man (Various)

First published in 1969, this sparkling collection of essays anatomised Churchill's qualities as a statesman (AJP Taylor), politician (Robert Rhodes James), historian (JH Plumb), military strategist (Basil Liddell Hart) and depressive human being (Anthony Storr). Research has moved on since then, but as an analysis of the essential Churchill the book has never been surpassed. It founded the British school of Churchillians who admire him 'warts and all'.

3. In Search of Churchill by Martin Gilbert

Political biography was a gentlemanly affair of delving into one or two archives until Martin Gilbert came on the scene. As Churchill's official biographer he set rigorous new standards of research, working through scores of manuscript collections and travelling far and wide in search of new material. The six volumes of his life are a towering achievement but not many people have the leisure, this side of retirement, to savour all 7,285 pages. In the meantime there could be no better introduction than Gilbert's highly entertaining account of his methods of writing, and his search for buried treasure: eye witnesses whose recollections had never been recorded, and caches of documents that had lain hidden for decades.

4. Winston Churchill: His Life as a Painter by Mary Soames

Denis Healey used to say that every politician needs a hinterland - an absorbing outside interest beyond the world of Westminster. Churchill found it in painting. He seldom travelled without his brushes and oils and the moment he set up his easel he was lost to the world. Churchill never claimed to be a great artist but he delighted in the landscapes he saw on his travels, domestic scenes from his home at Chartwell, and portraits of his family and friends. The story of his life as a painter, delightfully told by his daughter Mary Soames, is a revelation of the private self who kept the statesman human.

5. Churchill and Secret Service by David Stafford

Churchill's lifelong fascination with secret intelligence is the theme of this riveting book which covers everything from his first encounter with the 'Great Game' on the north-west frontier to his involvement in the Anglo-American inspired coup that led to the overthrow of Mussadiq in Iran in 1953. Though Stafford is at pains to disprove some of the conspiracy theories which implicate Churchill in episodes like the sinking of the Lusitania or the attack on Pearl Harbor, he shows that Churchill played a crucial part in the development of the intelligence services and was no mean hand with a cloak and dagger.

6. Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and his Legend since 1945 by John Ramsden

Ramsden has added a new dimension to Churchill studies with a richly detailed analysis of the growth of his legend since 1945. His book sets out "to understand how that fame was created, perceived, marketed, spun and in some cases even fabricated." In the course of a fascinating conducted tour of perceptions of Churchill around the English-speaking world, Ramsden identifies the publicists and politicians who constructed the legend and the monuments and memorabilia which celebrated him. Such is his eye for detail that he even remarks on Churchill's unassailable lead in commemorative Toby jugs: 22 different designs compared with two each for Baldwin, Chamberlain and Lloyd George.

7. In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War by David Reynolds

In writing his war memoirs Churchill had two main aims. The first was to make a fortune for himself and his family while protecting it from the taxman. The second was to create a useable past that would vindicate his judgment as a war leader and assist his activities as a postwar statesman. In a masterly feat of sustained scholarly analysis Reynolds explains how Churchill achieved a triumphant success on both counts. In anyone else Churchill's profiteering, manipulation of the documents, and unacknowledged use of ghost writers would look disreputable, but all is forgiven the saviour of his country.

8. Churchill: The End of Glory by John Charmley

The furore over the so-called 'Charmley thesis' - the case for a compromise peace with Hitler in 1940 - has distracted attention from an otherwise perceptive political life grounded in a coherent critique of Churchill's flaws, and a far from ungenerous appreciation of his abilities. Charmley adopts the sceptical view of Churchill held by most of his contemporaries before 1939, and extends it to apply to his conduct of the war - a debatable but stimulating exercise.

9. The Iron Curtain: Churchill, America and the Origins of the Cold War by Fraser J Harbutt

It is no secret that Churchill is revered by many Americans as a philosopher king and role model for leadership. Whereas in Britain we see him as a man of the past, he is admired in the US as a guide to the present and future. Churchill's unique stature on the other side of the Atlantic owes something to his wartime alliance with Roosevelt, but as Fraser Harbutt shows in a powerfully argued book, the decisive factor was the part Churchill played, while he was out of office, in facilitating the entry of the US into the cold war. The tipping point was his 'iron curtain' speech at Fulton in March 1946.

10. Churchill by Roy Jenkins; Churchill: A Study in Greatness by Geoffrey Best

The competition for the title of best one volume life of Churchill is intense and the result, it seems to me, is a tie between Roy Jenkins and Geoffrey Best. Both authors are comprehensive, accurate, and stylish, but in different ways. Jenkins brings to the subject a veteran politician's feel for office and power, a worldly appreciation of Churchill's love of the good life, and an encyclopaedic appetite for detail. His account is richly descriptive but tends to stick to the surface of events. Best is a more reflective and speculative writer with a historian's flair for the insights that lie just beyond the tangible evidence. By different routes both authors come to the same conclusion, or as Best puts it: 'His achievements, taken all in all, justify his title to be known as the greatest Englishman of his age...in this later time we are diminished if, admitting Churchill's failings and failures, we can no longer appreciate his virtues and victories.'

- History books

Most viewed

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Churchill: The Greatest Briton Unmasked

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

The magnitude of Winston Churchill's political career, with its numerous twists and turns, continues to baffle the efforts of biographers. The official biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert, buried him under a long and detailed chronology. Geoffrey Best turned him into a Boy's Own Paper hero. The most satisfactory of the single-volume biographies is that by Roy Jenkins, but it tails off after 1945, and deals in only a perfunctory manner with Churchill's peacetime premiership.

Jenkins followed Oliver Cromwell's advice to paint a portrait "warts and all". Yet he concluded that Churchill was the greatest man ever to have occupied 10 Downing Street. Nigel Knight, by contrast, has painted a portrait that contains nothing but warts. His book, a case for the prosecution, is written mainly from secondary sources, some of which are themselves works of popularisation rather than historical scholarship; and his bibliography includes works such as The Wicked Wit of Winston Churchill and Quotations for our Time, from which he takes some of his quotations.

Despite the iconoclastic subtitle, Churchill contains little that is new. It begins in 1914 and this enables Knight to dismiss Churchill's remarkable career at the Board of Trade, a period well covered in Jenkins' biography, during which Churchill presided over the introduction of the world's first scheme of unemployment insurance. Instead, Knight has managed to resurrect nearly every disreputable story about Churchill, many of which have already been consumer tested for many years. Do you want to know what Churchill said at the gentleman's urinal in the House of Commons in the early 1950s? You can learn the answer here. Do you want to be reminded of how Churchill failed at Gallipoli - an idea brilliant in conception but faulty in execution? That too is provided. It is with a polite if weary smile of recognition that we welcome back all these old friends.

Oddly enough, Knight has missed a trick in his discussion of the abdication. He ignores the evidence that indicates that in 1936 Churchill was motivated not by a quixotic love affair with the monarchy, but by a desire to overthrow the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin. There are two letters written by the Marquess of Zetland, Secretary of State for India in Baldwin's Government, to the Viceroy of India, one of which is published in Zetland's autobiography, Essayez, and the other of which is in the India Office library, suggesting that Churchill would have been willing to form a government of King's Friends had Baldwin been forced to resign. Churchill told Edward VIII that his Government did not really represent the true wishes of the people. As a result, so Zetland believed, the country was "faced with a problem compared with which even the international issues, grave as they assuredly are, pale into comparative insignificance". This is an important episode, since the distrust Churchill aroused contributed to the difficulties he faced in securing an audience for his fight against appeasement.

Knight cites examples of Churchill's conflicts with Alanbrooke, another well-worn topic better covered in Andrew Roberts' recent book, Masters and Commanders - a book that pays full tribute to Churchill's strategic sense and his ability to learn from mistakes. But Knight does not cite Alanbrooke's encomium that Churchill was "one of the most wonderful national leaders of our history", and one of the "human beings who stand out head and shoulders above all others".