How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

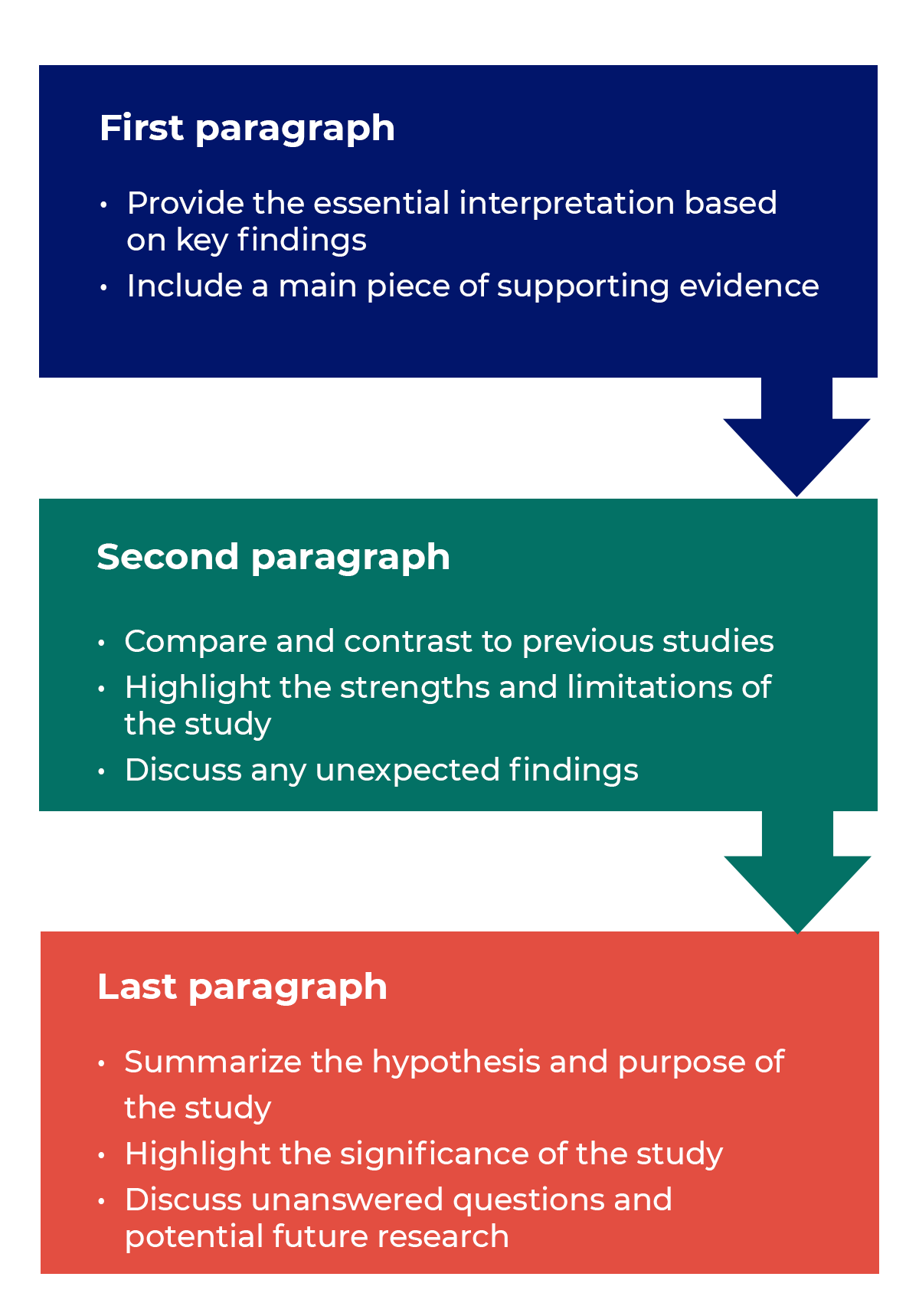

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how....

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of the main topics covered or a re-statement of your research problem, but a synthesis of key points derived from the findings of your study and, if applicable, where you recommend new areas for future research. For most college-level research papers, two or three well-developed paragraphs is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, more paragraphs may be required in describing the key findings and their significance.

Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides you with important opportunities to demonstrate to the reader your understanding of the research problem. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key findings in your analysis that advance new understanding about the research problem, that are unusual or unexpected, or that have important implications applied to practice.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger significance of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly re-emphasize your answer to the "So What?" question by placing the study within the context of how your research advances past research about the topic.

- Identifying how a gap in the literature has been addressed . The conclusion can be where you describe how a previously identified gap in the literature [first identified in your literature review section] has been addressed by your research and why this contribution is significant.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers an opportunity to elaborate on the impact and significance of your findings. This is particularly important if your study approached examining the research problem from an unusual or innovative perspective.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing or contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Bunton, David. “The Structure of PhD Conclusion Chapters.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (July 2005): 207–224; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

The general function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of the strengths of your main argument(s) and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Do this by clearly summarizing the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem you investigated in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found in the literature. However, make sure that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings. This reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your paper.

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- Present your conclusions in clear, concise language. Re-state the purpose of your study, then describe how your findings differ or support those of other studies and why [i.e., what were the unique, new, or crucial contributions your study made to the overall research about your topic?].

- Do not simply reiterate your findings or the discussion of your results. Provide a synthesis of arguments presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem and the overall objectives of your study.

- Indicate opportunities for future research if you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper. Highlighting the need for further research provides the reader with evidence that you have an in-depth awareness of the research problem but that further investigations should take place beyond the scope of your investigation.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is presented well:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data [this is opposite of the introduction, which begins with general discussion of the context and ends with a detailed description of the research problem].

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have conducted will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way. If asked to think introspectively about the topics, do not delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply, not to guess at possible outcomes or make up scenarios not supported by the evidence.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Although an effective conclusion needs to be clear and succinct, it does not need to be written passively or lack a compelling narrative. Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following:

- If your essay deals with a critical, contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem proactively.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action that, if adopted, could address a specific problem in practice or in the development of new knowledge leading to positive change.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion already noted in your paper in order to lend authority and support to the conclusion(s) you have reached [a good source would be from your literature review].

- Explain the consequences of your research in a way that elicits action or demonstrates urgency in seeking change.

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to emphasize the most important finding of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point by drawing from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you presented in your introduction, but add further insight derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results from your study to recast it in new or important ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a succinct, declarative statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid

Failure to be concise Your conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too lengthy often have unnecessary information in them. The conclusion is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, and other forms of analysis that you make. Strategies for writing concisely can be found here .

Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from the general [the field of study] to the specific [the research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move from a specific discussion [your research problem] back to a general discussion framed around the implications and significance of your findings [i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In short, the conclusion is where you should place your research within a larger context [visualize your paper as an hourglass--start with a broad introduction and review of the literature, move to the specific analysis and discussion, conclude with a broad summary of the study's implications and significance].

Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. These are problems, deficiencies, or challenges encountered during your study. They should be summarized as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative or unintended results [i.e., findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section and discuss their implications in the discussion section of your paper. In the conclusion, use negative results as an opportunity to explain their possible significance and/or how they may form the basis for future research.

Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to be able to discuss how your research fits within your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize briefly and succinctly how it contributes to new knowledge or a new understanding about the research problem. This element of your conclusion may be only a few sentences long.

Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives in the social and behavioral sciences change while the research is being carried out. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine the original objectives in your introduction. As these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you presumably should know a good deal about it [perhaps even more than your professor!]. Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority as a researcher by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches that...." The overall tone of your conclusion should convey confidence to the reader about the study's validity and realiability.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin Madison; Miquel, Fuster-Marquez and Carmen Gregori-Signes. “Chapter Six: ‘Last but Not Least:’ Writing the Conclusion of Your Paper.” In Writing an Applied Linguistics Thesis or Dissertation: A Guide to Presenting Empirical Research . John Bitchener, editor. (Basingstoke,UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93-105; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining that they are reaching the end of your paper. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper. This why the conclusion rarely has citations to sources. If you have new information to present, add it to the discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no new information is introduced, the conclusion, along with the discussion section, is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; the conclusion is where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate that you understand the material that you’ve presented, and position your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic, including describing how your research contributes new insights to that scholarship.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 10:04 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

How to write a strong conclusion for your research paper

Last updated

17 February 2024

Reviewed by

Writing a research paper is a chance to share your knowledge and hypothesis. It's an opportunity to demonstrate your many hours of research and prove your ability to write convincingly.

Ideally, by the end of your research paper, you'll have brought your readers on a journey to reach the conclusions you've pre-determined. However, if you don't stick the landing with a good conclusion, you'll risk losing your reader’s trust.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper involves a few important steps, including restating the thesis and summing up everything properly.

Find out what to include and what to avoid, so you can effectively demonstrate your understanding of the topic and prove your expertise.

- Why is a good conclusion important?

A good conclusion can cement your paper in the reader’s mind. Making a strong impression in your introduction can draw your readers in, but it's the conclusion that will inspire them.

- What to include in a research paper conclusion

There are a few specifics you should include in your research paper conclusion. Offer your readers some sense of urgency or consequence by pointing out why they should care about the topic you have covered. Discuss any common problems associated with your topic and provide suggestions as to how these problems can be solved or addressed.

The conclusion should include a restatement of your initial thesis. Thesis statements are strengthened after you’ve presented supporting evidence (as you will have done in the paper), so make a point to reintroduce it at the end.

Finally, recap the main points of your research paper, highlighting the key takeaways you want readers to remember. If you've made multiple points throughout the paper, refer to the ones with the strongest supporting evidence.

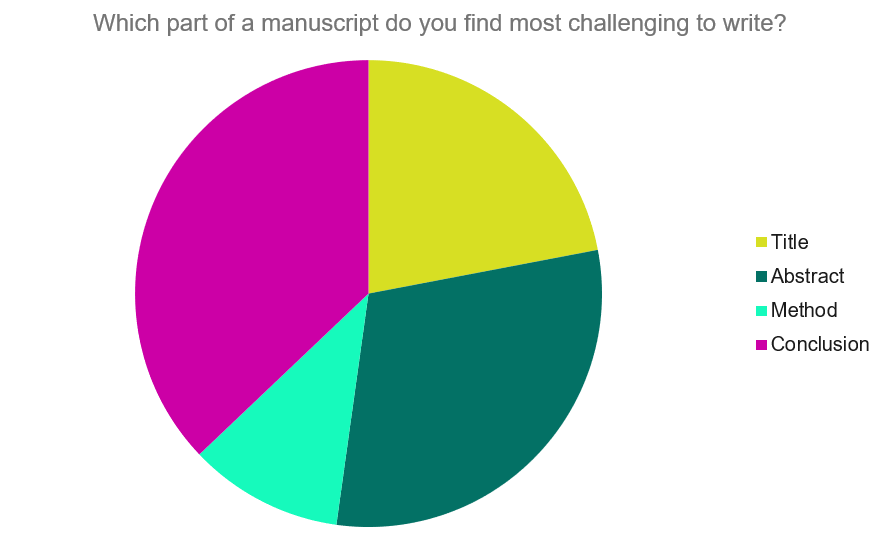

- Steps for writing a research paper conclusion

Many writers find the conclusion the most challenging part of any research project . By following these three steps, you'll be prepared to write a conclusion that is effective and concise.

- Step 1: Restate the problem

Always begin by restating the research problem in the conclusion of a research paper. This serves to remind the reader of your hypothesis and refresh them on the main point of the paper.

When restating the problem, take care to avoid using exactly the same words you employed earlier in the paper.

- Step 2: Sum up the paper

After you've restated the problem, sum up the paper by revealing your overall findings. The method for this differs slightly, depending on whether you're crafting an argumentative paper or an empirical paper.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

Argumentative papers involve introducing a thesis statement early on. In crafting the conclusion for an argumentative paper, always restate the thesis, outlining the way you've developed it throughout the entire paper.

It might be appropriate to mention any counterarguments in the conclusion, so you can demonstrate how your thesis is correct or how the data best supports your main points.

Empirical paper: Summarize research findings

Empirical papers break down a series of research questions. In your conclusion, discuss the findings your research revealed, including any information that surprised you.

Be clear about the conclusions you reached, and explain whether or not you expected to arrive at these particular ones.

- Step 3: Discuss the implications of your research

Argumentative papers and empirical papers also differ in this part of a research paper conclusion. Here are some tips on crafting conclusions for argumentative and empirical papers.

Argumentative paper: Powerful closing statement

In an argumentative paper, you'll have spent a great deal of time expressing the opinions you formed after doing a significant amount of research. Make a strong closing statement in your argumentative paper's conclusion to share the significance of your work.

You can outline the next steps through a bold call to action, or restate how powerful your ideas turned out to be.

Empirical paper: Directions for future research

Empirical papers are broader in scope. They usually cover a variety of aspects and can include several points of view.

To write a good conclusion for an empirical paper, suggest the type of research that could be done in the future, including methods for further investigation or outlining ways other researchers might proceed.

If you feel your research had any limitations, even if they were outside your control, you could mention these in your conclusion.

After you finish outlining your conclusion, ask someone to read it and offer feedback. In any research project you're especially close to, it can be hard to identify problem areas. Having a close friend or someone whose opinion you value read the research paper and provide honest feedback can be invaluable. Take note of any suggested edits and consider incorporating them into your paper if they make sense.

- Things to avoid in a research paper conclusion

Keep these aspects to avoid in mind as you're writing your conclusion and refer to them after you've created an outline.

Dry summary

Writing a memorable, succinct conclusion is arguably more important than a strong introduction. Take care to avoid just rephrasing your main points, and don't fall into the trap of repeating dry facts or citations.

You can provide a new perspective for your readers to think about or contextualize your research. Either way, make the conclusion vibrant and interesting, rather than a rote recitation of your research paper’s highlights.

Clichéd or generic phrasing

Your research paper conclusion should feel fresh and inspiring. Avoid generic phrases like "to sum up" or "in conclusion." These phrases tend to be overused, especially in an academic context and might turn your readers off.

The conclusion also isn't the time to introduce colloquial phrases or informal language. Retain a professional, confident tone consistent throughout your paper’s conclusion so it feels exciting and bold.

New data or evidence

While you should present strong data throughout your paper, the conclusion isn't the place to introduce new evidence. This is because readers are engaged in actively learning as they read through the body of your paper.

By the time they reach the conclusion, they will have formed an opinion one way or the other (hopefully in your favor!). Introducing new evidence in the conclusion will only serve to surprise or frustrate your reader.

Ignoring contradictory evidence

If your research reveals contradictory evidence, don't ignore it in the conclusion. This will damage your credibility as an expert and might even serve to highlight the contradictions.

Be as transparent as possible and admit to any shortcomings in your research, but don't dwell on them for too long.

Ambiguous or unclear resolutions

The point of a research paper conclusion is to provide closure and bring all your ideas together. You should wrap up any arguments you introduced in the paper and tie up any loose ends, while demonstrating why your research and data are strong.

Use direct language in your conclusion and avoid ambiguity. Even if some of the data and sources you cite are inconclusive or contradictory, note this in your conclusion to come across as confident and trustworthy.

- Examples of research paper conclusions

Your research paper should provide a compelling close to the paper as a whole, highlighting your research and hard work. While the conclusion should represent your unique style, these examples offer a starting point:

Ultimately, the data we examined all point to the same conclusion: Encouraging a good work-life balance improves employee productivity and benefits the company overall. The research suggests that when employees feel their personal lives are valued and respected by their employers, they are more likely to be productive when at work. In addition, company turnover tends to be reduced when employees have a balance between their personal and professional lives. While additional research is required to establish ways companies can support employees in creating a stronger work-life balance, it's clear the need is there.

Social media is a primary method of communication among young people. As we've seen in the data presented, most young people in high school use a variety of social media applications at least every hour, including Instagram and Facebook. While social media is an avenue for connection with peers, research increasingly suggests that social media use correlates with body image issues. Young girls with lower self-esteem tend to use social media more often than those who don't log onto social media apps every day. As new applications continue to gain popularity, and as more high school students are given smartphones, more research will be required to measure the effects of prolonged social media use.

What are the different kinds of research paper conclusions?

There are no formal types of research paper conclusions. Ultimately, the conclusion depends on the outline of your paper and the type of research you’re presenting. While some experts note that research papers can end with a new perspective or commentary, most papers should conclude with a combination of both. The most important aspect of a good research paper conclusion is that it accurately represents the body of the paper.

Can I present new arguments in my research paper conclusion?

Research paper conclusions are not the place to introduce new data or arguments. The body of your paper is where you should share research and insights, where the reader is actively absorbing the content. By the time a reader reaches the conclusion of the research paper, they should have formed their opinion. Introducing new arguments in the conclusion can take a reader by surprise, and not in a positive way. It might also serve to frustrate readers.

How long should a research paper conclusion be?

There's no set length for a research paper conclusion. However, it's a good idea not to run on too long, since conclusions are supposed to be succinct. A good rule of thumb is to keep your conclusion around 5 to 10 percent of the paper's total length. If your paper is 10 pages, try to keep your conclusion under one page.

What should I include in a research paper conclusion?

A good research paper conclusion should always include a sense of urgency, so the reader can see how and why the topic should matter to them. You can also note some recommended actions to help fix the problem and some obstacles they might encounter. A conclusion should also remind the reader of the thesis statement, along with the main points you covered in the paper. At the end of the conclusion, add a powerful closing statement that helps cement the paper in the mind of the reader.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

3-minute read

- 29th August 2023

If you’re writing a research paper, the conclusion is your opportunity to summarize your findings and leave a lasting impression on your readers. In this post, we’ll take you through how to write an effective conclusion for a research paper and how you can:

· Reword your thesis statement

· Highlight the significance of your research

· Discuss limitations

· Connect to the introduction

· End with a thought-provoking statement

Rewording Your Thesis Statement

Begin your conclusion by restating your thesis statement in a way that is slightly different from the wording used in the introduction. Avoid presenting new information or evidence in your conclusion. Just summarize the main points and arguments of your essay and keep this part as concise as possible. Remember that you’ve already covered the in-depth analyses and investigations in the main body paragraphs of your essay, so it’s not necessary to restate these details in the conclusion.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Highlighting the Significance of Your Research

The conclusion is a good place to emphasize the implications of your research . Avoid ambiguous or vague language such as “I think” or “maybe,” which could weaken your position. Clearly explain why your research is significant and how it contributes to the broader field of study.

Here’s an example from a (fictional) study on the impact of social media on mental health:

Discussing Limitations

Although it’s important to emphasize the significance of your study, you can also use the conclusion to briefly address any limitations you discovered while conducting your research, such as time constraints or a shortage of resources. Doing this demonstrates a balanced and honest approach to your research.

Connecting to the Introduction

In your conclusion, you can circle back to your introduction , perhaps by referring to a quote or anecdote you discussed earlier. If you end your paper on a similar note to how you began it, you will create a sense of cohesion for the reader and remind them of the meaning and significance of your research.

Ending With a Thought-Provoking Statement

Consider ending your paper with a thought-provoking and memorable statement that relates to the impact of your research questions or hypothesis. This statement can be a call to action, a philosophical question, or a prediction for the future (positive or negative). Here’s an example that uses the same topic as above (social media and mental health):

Expert Proofreading Services

Ensure that your essay ends on a high note by having our experts proofread your research paper. Our team has experience with a wide variety of academic fields and subjects and can help make your paper stand out from the crowd – get started today and see the difference it can make in your work.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

What is a content editor.

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

- Posted on May 12, 2023

The key to an impactful research paper is crafting an effective conclusion. The conclusion provides a final opportunity to make a lasting impression on the reader by providing a powerful summary of the main argument and key findings.

A well-written conclusion not only summarizes your research but also ties everything back to your thesis statement. Plus, it provides important takeaways for your reader, highlighting what they should remember from your research and how it contributes to the larger academic discourse.

Crafting an impactful conclusion can be tricky, especially in argumentative papers. However, with our expert tips and tricks, you can rest assured that your conclusion will effectively restate the main argument and thesis statement in a way that resonates with your audience and elevates your research to new heights.

Why is a Conclusion Necessary for a Research Paper?

The conclusion of a research paper is essential in tying together the different parts of the paper and offering a final perspective on the topic. It reinforces the main idea or argument presented and summarizes the key points and findings of the research, highlighting its significance.

Additionally, the conclusion creates a full circle of the research by connecting back to the thesis statement presented at the paper’s beginning. It provides an opportunity to showcase the writer’s critical thinking skills by demonstrating how the research supports the main argument.

The conclusion is essential for a research paper because it provides closure for the reader. It serves as a final destination that helps the reader understand how all the different pieces of information fit together to support the main argument presented. It also offers insights into how the research can inform future studies and contribute to the larger academic discourse.

It also ensures that the reader does not get lost in the vast amount of information presented in the paper by providing a concise and coherent summary of the entire research. Additionally, it helps the reader identify the paper’s main takeaway and understand how the research contributes to the larger body of knowledge in the field.

Leave a Lasting Impression

A well-crafted conclusion is an essential element of any research paper. Its purpose is to leave a lasting impression on the reader and tie together the different parts of the paper.

To achieve this goal, a conclusion should summarize the main points and highlight the key findings of the research. By doing so, the reader can easily understand the focus and significance of the study.

A strong conclusion should also discuss any important findings that can be applied in the real world. This practical perspective gives readers a better sense of the impact and relevance of the research.

Summarize Your Thoughts

The conclusion of a research paper should be concise and provide a summary of the writer’s thoughts and ideas about the research.

It should go beyond simply restating the main points and findings and address the “so what” of the research by explaining how it contributes to the existing body of knowledge on the same topic. This way, the conclusion can give readers a better understanding of the research’s significance and relevance to the broader academic community.

Demonstrate How Important Your Idea Is

Moving beyond a superficial overview and delving into the research in-depth is crucial to create a compelling conclusion. This entails summarizing the key findings of the study, highlighting its main contributions to the field, and placing the results in a broader context. Additionally, it would help if you comprehensively analyzed your work and its implications, underscoring its value to the broader academic community.

New Insights

The conclusion section of a research paper offers an opportunity for the writer to present new insights and approaches to addressing the research problem.

Whether the research outcome is positive or negative, the conclusion provides a platform to discuss practical implications beyond the scope of the research paper. This discussion can help readers understand the potential impact of the research on the broader field and its significance for future research endeavors.

How to Write a Killer Conclusion with Key Points

When writing a conclusion for a research paper, it is important to cover several key points to create a solid and effective conclusion.

Restate the Thesis

When crafting a conclusion, restating the thesis statement is an important step that reminds readers of the research paper’s central focus. However, it should not be a verbatim repetition of the introduction.

By restating the thesis concisely and clearly, you can effectively tie together the main ideas discussed in the body of the paper and emphasize the significance of the research question. However, keep in mind that the restated thesis should capture the essence of the paper and leave the reader with a clear understanding of the main topic and its importance.

Summarize the Main Points

To write an impactful conclusion, summarizing the main points discussed in the body of the paper is essential. This final section provides the writer with a last opportunity to highlight the significance of their research findings.

However, it is equally important to avoid reiterating information already discussed in the body of the paper. Instead, you should synthesize and summarize the most significant points to emphasize the key findings. By doing so, the conclusion can effectively tie together the research findings and provide a clear understanding of the importance of the research topic.

Discuss the Results or Findings

The next step is to discuss the results or findings of the research. The discussion of the results or findings should not simply be a repetition of the information presented in the body of the paper.

Instead, it should provide a more in-depth analysis of the significance of the findings. This can involve explaining why the findings are important, what they mean in the context of the research question, and how they contribute to the field or area of study.

Additionally, it’s crucial to address any limitations or weaknesses of the study in this section. This can provide a more balanced and nuanced understanding of the research and its implications. By doing so, the reader will have a better understanding of the scope and context of the study, which can ultimately enhance the credibility and validity of the research.

Ruminate on Your Thoughts

The final step to crafting an effective conclusion is to ruminate on your thoughts. This provides an opportunity to reflect on the meaning of the research and leaves the reader with something to ponder. Remember, the concluding paragraph should not introduce new information but rather summarize and reflect on the critical points made in the paper.

Furthermore, the conclusion should be integrated into the paper rather than presented as a separate section. It should provide a concise overview of the main findings and suggest avenues for further research.

Different Types of Conclusions

There are various types of conclusions that can be employed to conclude a research paper effectively, depending on the research questions and topic being investigated.

Summarizing

Summarizing conclusions are frequently used to wrap up a research paper effectively. They restate the thesis statement and provide a brief overview of the main findings and outcomes of the research. This type of conclusion serves as a reminder to the reader of the key points discussed throughout the paper and emphasizes the significance of the research topic.

To be effective, summarizing conclusions should be concise and to the point, avoiding any new information not previously discussed in the body of the paper. Moreover, they are particularly useful when there is a clear and direct answer to the research question. This allows you to summarize your findings succinctly and leave the reader with a clear understanding of the implications of the research.

Externalizing

On the opposite end of the spectrum are externalizing conclusions. Unlike summarizing conclusions, externalizing conclusions introduce new ideas that may not be directly related to the research findings. This type of conclusion can be beneficial because it broadens the scope of the research topic and can lead to new insights and directions for future research.

By presenting new ideas, externalizing conclusions can challenge conventional thinking in the field and open up new avenues for exploration. This approach is instrumental in fields where research is ongoing, and new ideas and approaches are constantly being developed.

Editorial conclusions are a type of conclusion that allows the writer to express their commentary on the research findings. They can be particularly effective in connecting the writer’s insights with the research conducted and can offer a unique perspective on the research topic. Adding a personal touch to the conclusion can help engage the reader and leave a lasting impression.

Remember that regardless of the type of conclusion you choose, it should always start with a clear and concise restatement of the thesis statement, followed by a summary of the main findings in the body paragraphs. The first sentence of the conclusion should be impactful and attention-grabbing to make a strong impression on the reader.

What to Avoid in Your Conclusion

When crafting your conclusion, it’s essential to keep in mind several key points to ensure that it is effective and well-received by your audience:

- Avoid introducing new ideas or topics that have not been covered in the body of your paper.

- Refrain from simply restating what has already been said in your paper without adding new insights or analysis.

- Do not apologize for any shortcomings or limitations of your research, as this can undermine the importance of your findings.

- Avoid using overly emotional or flowery language, as it can detract from the professionalism and objectivity of the research.

- Lastly, avoid any examples of plagiarism. Be sure to properly cite any sources you have used in your research and writing.

Example of a Bad Conclusion

- Recapitulation without Insight: In conclusion, this paper has discussed the importance of exercise for physical and mental health. We hope this paper has been helpful to you and encourages you to start exercising today.

- Introduction of New Ideas: In conclusion, we have discussed the benefits of exercise and how it can improve physical and mental health. Additionally, we have highlighted the benefits of a plant-based diet and the importance of getting enough sleep for overall well-being.

- Emotional Language: In conclusion, exercise is good for your body and mind, and you should definitely start working out today!

Example of a Good Conclusion

- Insights and Implications: In light of our investigation, it is evident that regular exercise is undeniably beneficial for both physical and mental well-being, especially if performed at an appropriate duration and frequency. These findings hold significant implications for public health policies and personal wellness decisions.

- Limitations and Future Directions: While our investigation has shed light on the benefits of exercise, our study is not without limitations. Future research can delve deeper into the long-term effects of exercise on mental health and explore the impact of exercise on specific populations, such as older adults or individuals with chronic health conditions.

- Call to Action: In conclusion, we urge individuals to prioritize exercise as a critical component of their daily routine. By making exercise a habit, we can reap the many benefits of a healthy and active lifestyle.

Final Thoughts

When writing a research paper, the conclusion is one of the most crucial elements to leave a lasting impression on the reader. It should effectively summarize the research and provide valuable insights, leaving the reader with something to ponder.

To accomplish this, it is essential to include vital elements, such as restating the thesis , summarizing the main points, and discussing the findings. However, it is equally important to avoid common mistakes that can undermine the effectiveness of the conclusion, such as introducing new information or repeating the introduction.

So to ensure that your research is of the highest quality, it’s crucial to use proper citations and conduct a thorough literature review. Additionally, it is crucial to proofread the work to eliminate any errors.

Fortunately, there are many available resources to help you with both writing and plagiarism prevention. Quetext , for example, offers a plagiarism checker, citation assistance, and proofreading tools to ensure the writing is top-notch. By incorporating these tips and using available resources, you can create a compelling and memorable conclusion for readers.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

Can You Go to Jail for Plagiarism?

- Posted on March 22, 2024 March 22, 2024

Empowering Educators: How AI Detection Enhances Teachers’ Workload

- Posted on March 14, 2024

The Ethical Dimension | Navigating the Challenges of AI Detection in Education

- Posted on March 8, 2024

How to Write a Thesis Statement & Essay Outline

- Posted on February 29, 2024 February 29, 2024

The Crucial Role of Grammar and Spell Check in Student Assignments

- Posted on February 23, 2024 February 23, 2024

Revolutionizing Education: The Role of AI Detection in Academic Integrity

- Posted on February 15, 2024

How Reliable are AI Content Detectors? Which is Most Reliable?

- Posted on February 8, 2024 February 8, 2024

What Is an Article Spinner?

- Posted on February 2, 2024 February 2, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

In a short paper—even a research paper—you don’t need to provide an exhaustive summary as part of your conclusion. But you do need to make some kind of transition between your final body paragraph and your concluding paragraph. This may come in the form of a few sentences of summary. Or it may come in the form of a sentence that brings your readers back to your thesis or main idea and reminds your readers where you began and how far you have traveled.

So, for example, in a paper about the relationship between ADHD and rejection sensitivity, Vanessa Roser begins by introducing readers to the fact that researchers have studied the relationship between the two conditions and then provides her explanation of that relationship. Here’s her thesis: “While socialization may indeed be an important factor in RS, I argue that individuals with ADHD may also possess a neurological predisposition to RS that is exacerbated by the differing executive and emotional regulation characteristic of ADHD.”

In her final paragraph, Roser reminds us of where she started by echoing her thesis: “This literature demonstrates that, as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Highlight the “so what”

At the beginning of your paper, you explain to your readers what’s at stake—why they should care about the argument you’re making. In your conclusion, you can bring readers back to those stakes by reminding them why your argument is important in the first place. You can also draft a few sentences that put those stakes into a new or broader context.

In the conclusion to her paper about ADHD and RS, Roser echoes the stakes she established in her introduction—that research into connections between ADHD and RS has led to contradictory results, raising questions about the “behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

She writes, “as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Leave your readers with the “now what”

After the “what” and the “so what,” you should leave your reader with some final thoughts. If you have written a strong introduction, your readers will know why you have been arguing what you have been arguing—and why they should care. And if you’ve made a good case for your thesis, then your readers should be in a position to see things in a new way, understand new questions, or be ready for something that they weren’t ready for before they read your paper.

In her conclusion, Roser offers two “now what” statements. First, she explains that it is important to recognize that the flawed behavioral mediation hypothesis “seems to place a degree of fault on the individual. It implies that individuals with ADHD must have elicited such frequent or intense rejection by virtue of their inadequate social skills, erasing the possibility that they may simply possess a natural sensitivity to emotion.” She then highlights the broader implications for treatment of people with ADHD, noting that recognizing the actual connection between rejection sensitivity and ADHD “has profound implications for understanding how individuals with ADHD might best be treated in educational settings, by counselors, family, peers, or even society as a whole.”

To find your own “now what” for your essay’s conclusion, try asking yourself these questions:

- What can my readers now understand, see in a new light, or grapple with that they would not have understood in the same way before reading my paper? Are we a step closer to understanding a larger phenomenon or to understanding why what was at stake is so important?

- What questions can I now raise that would not have made sense at the beginning of my paper? Questions for further research? Other ways that this topic could be approached?

- Are there other applications for my research? Could my questions be asked about different data in a different context? Could I use my methods to answer a different question?

- What action should be taken in light of this argument? What action do I predict will be taken or could lead to a solution?

- What larger context might my argument be a part of?

What to avoid in your conclusion

- a complete restatement of all that you have said in your paper.

- a substantial counterargument that you do not have space to refute; you should introduce counterarguments before your conclusion.

- an apology for what you have not said. If you need to explain the scope of your paper, you should do this sooner—but don’t apologize for what you have not discussed in your paper.

- fake transitions like “in conclusion” that are followed by sentences that aren’t actually conclusions. (“In conclusion, I have now demonstrated that my thesis is correct.”)

- picture_as_pdf Conclusions

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

Table of Contents

Writing a conclusion for a research paper is a critical step that often determines the overall impact and impression the paper leaves on the reader. While some may view the conclusion as a mere formality, it is actually an opportunity to wrap up the main points, provide closure, and leave a lasting impression. In this article, we will explore the importance of a well-crafted conclusion and discuss various tips and strategies to help you write an engaging and impactful conclusion for your research paper.

Introduction

Before delving into the specifics of writing a conclusion, it is important to understand why it is such a crucial component of a research paper. The conclusion serves to summarize the main points of the paper and reemphasize their significance. A well-written conclusion can leave the reader satisfied and inspired, while a poorly executed one may undermine the credibility of the entire paper. Therefore, it is essential to give careful thought and attention to crafting an effective conclusion.

When writing a research paper, the conclusion acts as the final destination for the reader. It is the point where all the information, arguments, and evidence presented throughout the paper converge. Just as a traveler reaches the end of a journey, the reader reaches the conclusion to find closure and a sense of fulfillment. This is why the conclusion should not be taken lightly; it is a critical opportunity to leave a lasting impact on the reader.

Moreover, the conclusion is not merely a repetition of the introduction or a summary of the main points. It goes beyond that by providing a deeper understanding of the research findings and their implications. It allows the writer to reflect on the significance of their work and its potential contributions to the field. By doing so, the conclusion elevates the research paper from a mere collection of facts to a thought-provoking piece of scholarship.

In the following sections, we will explore various strategies and techniques for crafting a compelling conclusion. By understanding the importance of the conclusion and learning how to write one effectively, you will be equipped to create impactful research papers.

Structuring the Conclusion

In order to create an effective conclusion, it is important to consider its structure. A well-structured conclusion should begin by restating the thesis statement and summarizing the main points of the paper. It should then move on to provide a concise synthesis of the key findings and arguments, highlighting their implications and relevance. Finally, the conclusion should end with a thought-provoking statement that leaves the reader with a lasting impression.

Additionally, using phrases like "this research demonstrates," "the findings show," or "it is clear that" can help to highlight the significance of your research and emphasize your main conclusions.

Tips for Writing an Engaging Conclusion

Writing an engaging conclusion requires careful consideration and attention to detail. Here are some tips to help you create an impactful conclusion for your research paper:

- Revisit the Introduction: Start your conclusion by referencing your introduction. Remind the reader of the research question or problem you initially posed and show how your research has addressed it.

- Summarize Your Main Points: Provide a concise summary of the main points and arguments presented in your paper. Be sure to restate your thesis statement and highlight the key findings.

- Offer a Fresh Perspective: Use the conclusion as an opportunity to provide a fresh perspective or offer insights that go beyond the main body of the paper. This will leave the reader with something new to consider.

- Leave a Lasting Impression: End your conclusion with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action. This will leave a lasting impression on the reader and encourage further exploration of the research topic.

Addressing Counter Arguments In Conclusion

While crafting your conclusion, you can address any potential counterarguments or limitations of your research. This will demonstrate that you have considered alternative perspectives and have taken them into account in your conclusions. By acknowledging potential counterarguments, you can strengthen the credibility and validity of your research. And by openly discussing limitations, you demonstrate transparency and honesty in your research process.

Language and Tone To Be Used In Conclusion

The language and tone of your conclusion play a crucial role in shaping the overall impression of your research paper. It is important to use clear and concise language that is appropriate for the academic context. Avoid using overly informal or colloquial language that may undermine the credibility of your research. Additionally, consider the tone of your conclusion – it should be professional, confident, and persuasive, while still maintaining a respectful and objective tone.

When it comes to the language used in your conclusion, precision is key. You want to ensure that your ideas are communicated effectively and that there is no room for misinterpretation. Using clear and concise language will not only make your conclusion easier to understand but will also demonstrate your command of the subject matter.

Furthermore, it is important to strike the right balance between formality and accessibility. While academic writing typically requires a more formal tone, you should still aim to make your conclusion accessible to a wider audience. This means avoiding jargon or technical terms that may confuse readers who are not familiar with the subject matter. Instead, opt for language that is clear and straightforward, allowing anyone to grasp the main points of your research.

Another aspect to consider is the tone of your conclusion. The tone should reflect the confidence you have in your research findings and the strength of your argument. By adopting a professional and confident tone, you are more likely to convince your readers of the validity and importance of your research. However, it is crucial to strike a balance and avoid sounding arrogant or dismissive of opposing viewpoints. Maintaining a respectful and objective tone will help you engage with your audience in a more persuasive manner.

Moreover, the tone of your conclusion should align with the overall tone of your research paper. Consistency in tone throughout your paper will create a cohesive and unified piece of writing.

Common Mistakes to Avoid While Writing a Conclusion

When writing a conclusion, there are several common mistakes that researchers often make. By being aware of these pitfalls, you can avoid them and create a more effective conclusion for your research paper. Some common mistakes include:

- Repeating the Introduction: A conclusion should not simply be a reworded version of the introduction. While it is important to revisit the main points, try to present them in a fresh and broader perspective, by foregrounding the implications/impacts of your research.

- Introducing New Information: The conclusion should not introduce any new information or arguments. Instead, it should focus on summarizing and synthesizing the main points presented in the paper.

- Being Vague or General: Avoid using vague or general statements in your conclusion. Instead, be specific and provide concrete examples or evidence to support your main points.

- Ending Abruptly: A conclusion should provide a sense of closure and completeness. Avoid ending your conclusion abruptly or leaving the reader with unanswered questions.

Editing and Revising the Conclusion

Just like the rest of your research paper, the conclusion should go through a thorough editing and revising process. This will help to ensure clarity, coherence, and impact in the conclusion. As you revise your conclusion, consider the following:

- Check for Consistency: Ensure that your conclusion aligns with the main body of the paper and does not introduce any new or contradictory information.

- Eliminate Redundancy: Remove any repetitive or redundant information in your conclusion. Instead, focus on presenting the key points in a concise and engaging manner.

- Proofread for Clarity: Read your conclusion aloud or ask someone else to read it to ensure that it is clear and understandable. Check for any grammatical or spelling errors that may distract the reader.

- Seek Feedback: Consider sharing your conclusion with peers or mentors to get their feedback and insights. This can help you strengthen your conclusion and make it more impactful.

How to Write Conclusion as a Call to Action

Finally, consider using your conclusion as a call to action. Encourage the reader to take further action, such as conducting additional research or considering the implications of your findings. By providing a clear call to action, you can inspire the reader to actively engage with your research and continue the conversation on the topic.

Adapting to Different Research Paper Types

It is important to adapt your conclusion approach based on the type of research paper you are writing. Different research paper types may require different strategies and approaches to writing the conclusion. For example, a scientific research paper may focus more on summarizing the key findings and implications, while a persuasive research paper may emphasize the call to action and the potential impact of the research. Tailor your conclusion to suit the specific goals and requirements of your research paper.

Final Thoughts

A well-crafted conclusion can leave a lasting impression on the reader and enhance the impact of your research. By following the tips and strategies outlined in this article, you can create an engaging and impactful conclusion that effectively summarizes your main points, addresses potential counterarguments, and leaves the reader with a sense of closure and inspiration. Embrace the importance of the conclusion and view it as an opportunity to showcase the significance and relevance of your research.

Important Reads

How To Humanize AI Text In Scientific Articles

Elevate Your Writing Game With AI Grammar Checker Tools

A Guide to Using AI Tools to Summarize Literature Reviews

AI for Essay Writing — Exploring Top 10 Essay Writers

Role of AI in Systematic Literature Review

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions