- Corrections

Aristotle’s Model of Communication: 3 Key Elements of Persuasion

What was Aristotle’s contribution to rhetoric? We explore his influential model of communication.

Aristotle took a stance on almost every possible philosophical debate of his time, but more importantly, he came up with new issues and kickstarted new discussions as well. Aristotle was one of the first thinkers to delve into rhetoric and contributed greatly to its forming and development. He came up with many insights and theories on the topic of linguistics within rhetoric. However, his communication model remains his most prominent theory to this day. Let’s see what his model of communication consists of.

Introduction to Aristotle’s Model of Communication

Before we begin analyzing Aristotle’s model of communication, some context is needed. Aristotle was one of the first philosophers that worked on the art of speaking. It was his treatise Rhetoric that founded the basic principles of rhetorical theory and spoke openly about the art of persuasion. To this day, most rhetoricians regard it as the most important single work on persuasion ever written. That’s why Aristotle’s model of communication is still used to this day.

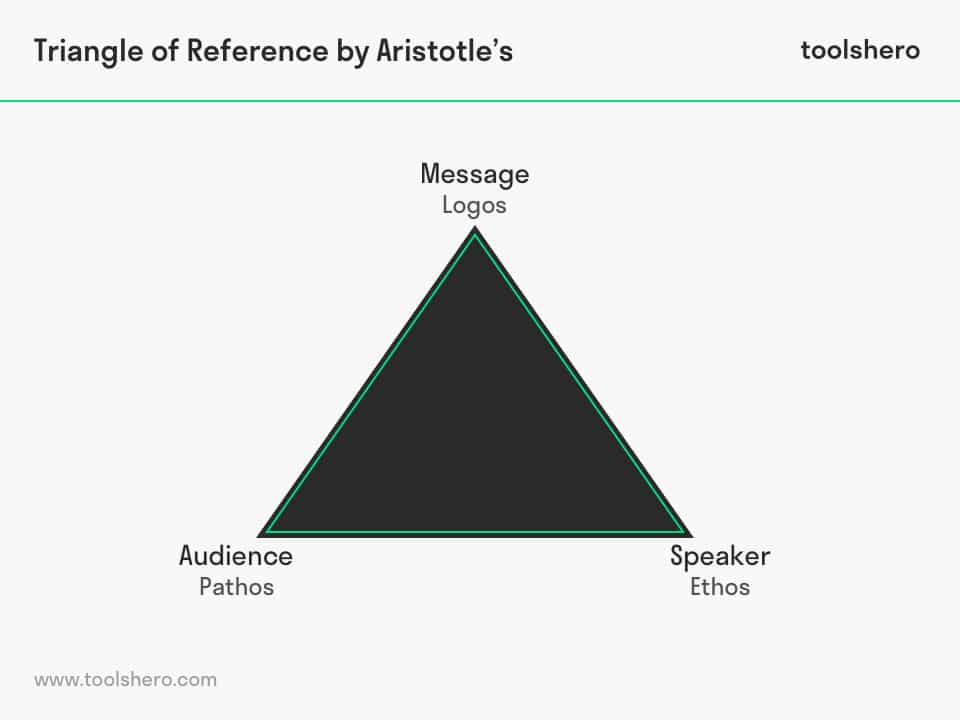

Aristotle’s model of communication is also known as the “rhetorical triangle” or as the “speaker-audience-message” model. It consists of three main elements: the speaker, the audience, and the message.

1. The Speaker

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox, please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The speaker is the person who is delivering the message. In this model, the speaker is responsible for creating and delivering the message effectively. This includes not only the words used but also the delivery style, tone, and body language.

2. The Audience

The audience is the group of people who receive the message. In this model, the audience is considered an essential part of the communication process. The speaker needs to understand the audience’s needs, interests, beliefs, and values to effectively communicate the message.

3. The Message

The message is the content of what is being communicated. In this model, the message should be clear, concise, and persuasive. The message should be crafted with the audience in mind to ensure that it is relevant and engaging.

Aristotle’s model of communication is important because it seems plausible and valid even in our modern lives. His model consists of three bullet points or three main important elements. That’s why we’ll explore each of them one by one.

The First Element of Communication: Ethos

The first element Aristotle comes up with is what he calls ethos . Ethos is essentially the speaker’s credibility to talk about the subject that he’s talking about and discuss it openly and with certainty.

What Aristotle means by ethos is the process of the speaker establishing his credibility about the subject he’s talking about. That can simply be done by mentioning the area of expertise he had majored in, but it can also be done by demonstrating his ability to back up his arguments. Credibility can also be built by using evidence, citing sources, or drawing on the speaker’s own experience or expertise. That’s why having empirical data to back up your arguments with clear proof is essential for this point.

What this does to an audience is create an image of the speaker as someone who knows what they are talking about and as someone that they can easily rely on and trust. That’s why Aristotle mentions it as the first important point out of the 3 most important ones.

The Second Element of Communication: Pathos

The second most important element of communication is what Aristotle calls pathos . The literal translation of pathos is emotion. Pathos is essentially the speaker establishing an emotional connection with the audience he’s speaking to.

The idea behind pathos is that the audience has to feel that they are being communicated with or that they are, in a way, interconnected. Emotional bonds will make the listeners fascinated, and they feel the speaker is “one of them.” In certain situations, the audience might want to feel more confident; in others, sadder, angry, or emotional. So, in Aristotle’s model of communication, pathos refers to the emotional appeal of a message. It focuses on engaging the audience’s emotions and creating a connection with them in order to persuade or influence their attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors.

Pathos can be conveyed through various elements of communication, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and the use of vivid language and imagery. In order to effectively use pathos in communication, Aristotle suggested that speakers should have a deep understanding of their audience and their emotional state. By appealing to their emotions and creating a connection with them, speakers can make their message more memorable and impactful.

The Third Element of Communication: Logos

The third most important element of communication Aristotle points out is logos. Logos refers to the logical or rational appeal of a message. This element focuses on the substance of the message and how it is presented to the audience.

Logos can be seen as the argument or reasoning behind a message, and it is often used to appeal to the audience’s sense of logic or reason. While ethos refers to the credibility or trustworthiness of the speaker or source of the message, and pathos refers to the emotional appeal in a message, logos focuses on the logical appeal and the argumentative structure of the message itself.

In order to effectively use logos in communication, Aristotle suggested that speakers should use clear and logical arguments, present evidence or facts to support their claims, and use reasoning to connect their ideas and persuade their audience. By appealing to the audience’s sense of logic and reason, speakers can create a persuasive message that is grounded in substance and can effectively influence their audience.

Criticisms of Aristotle’s Model of Communication

Now that we’ve carefully analyzed Aristotle’s model of communication, it’s time to look into the strong and weak points of the theory.

When it comes to the theory’s strengths, we can mention the following. First and foremost, the model emphasizes the importance of understanding the audience and adapting the message to their needs and interests. This means that the model’s main focus is figuring out the best approach to get through to the audience and their concerns, needs, and interests.

The second advantage this model provides is a clear structure for organizing a persuasive message, including the use of logos, ethos, and pathos. This makes it easier for the speaker to tailor his speech easily by following a particular structure. The third strength of this model is that it shows the importance of effective delivery techniques, such as tone and body language, which can enhance the impact of the message. Through these techniques, the speaker can easily point out a particular sentence or saying that he wants the audience to notice, for example.

However, regardless of the model’s many strengths, many of them unmentioned here, it is important to think critically and mention some of its weaker points and limitations.

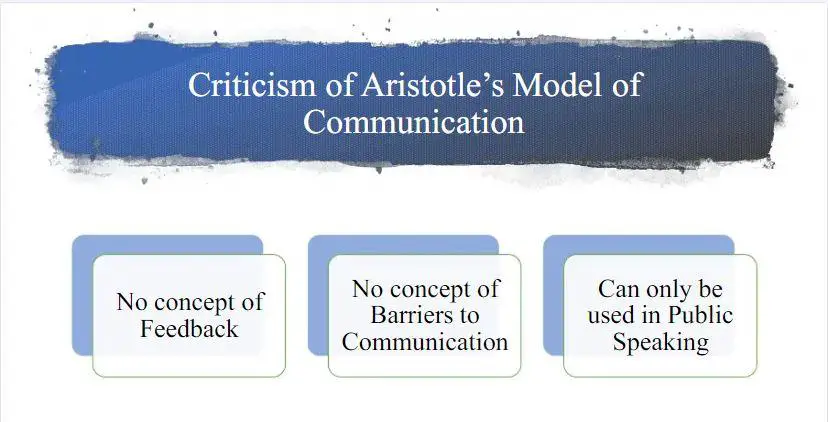

First, the model is primarily focused on persuasion and may not be as useful in non-persuasive communication contexts. The model’s main use is having an audience involved at an event of a certain kind, which is why it may not be efficient for everyday use.

The second and probably most notable limitation of this theory is that the model assumes that communication is a linear process and does not account for the dynamic and interactive nature of communication. This means that the model does not leave any space for any sort of feedback, questions, or brainstorming sessions from the audience, taking them to be passive listeners to the speech the speaker is giving. Thus, the model is only applicable to public speaking of a very specific kind.

Some thinkers object to this limitation. Even though Aristotle’s model of communication is mostly associated with public speaking and formal communication situations, they say, the principles of effective communication outlined in Aristotle’s model can also be applied to everyday communication. For example, understanding the audience’s needs and interests can help us communicate more effectively with friends, family members, and coworkers. Crafting a clear and concise message can also help us avoid misunderstandings and conflicts in everyday interactions. Aristotle’s model of communication emphasizes the importance of understanding the audience and crafting a persuasive message, which is an essential skill in all types of communication, whether it’s public speaking or everyday conversation. Still, the model’s limitation still stands and is plausible.

The third limitation is that the model may not account for contextual factors that can influence communication, such as cultural differences or power dynamics.

The Lasting Influence of Aristotle’s Model of Communication

In conclusion, Aristotle’s model of communication is a timeless framework that still has relevance today. The three elements of ethos, logos, and pathos provide a solid guide for speakers to effectively communicate their message and persuade their audience. Ethos focuses on the credibility and trustworthiness of the speaker, logos emphasizes the use of logic and reasoning in the message, and pathos is the emotional appeal that creates a connection with the audience.

While Aristotle’s model of communication is widely recognized as a classic, other similar models have emerged in the field of communication. For instance, Berlo’s model of communication incorporates four elements, including source, message, channel, and receiver, and emphasizes the importance of feedback in the communication process (thus avoiding one of the weaknesses of Aristotle’s approach). Similarly, Shannon and Weaver’s model of communication focuses on the transmission of a message through a channel and highlights the role of noise and distortion in the communication process.

It’s also important to mention that Aristotle was not the first one to notice the power that language can have. The Sophists taught a lot about language, and even Aristotle’s mentor Plato talked extensively about language as well. However, it was Aristotle that contributed the most to the forming of rhetoric as a discipline. Aristotle’s model of communication remains an important foundation for understanding effective communication, and it continues to influence contemporary models and theories in the field of communication.

Aristotle’s Philosophy: Eudaimonia and Virtue Ethics

By Antonio Panovski BA Philosophy Antonio holds a BA in Philosophy from SS. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, North Macedonia. His main areas of interest are contemporary, as well as analytic philosophy, with a special focus on the epistemological aspect of them, although he’s currently thoroughly examining the philosophy of science. Besides writing, he loves cinema, music, and traveling.

Frequently Read Together

What is Rhetoric and Is it Good? Exploring Plato’s Sophist

Why Aristotle Hated Athenian Democracy

What Were Aristotle’s Four Cardinal Virtues?

- List of Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Opt-out preferences

Aristotle’s Communication Model

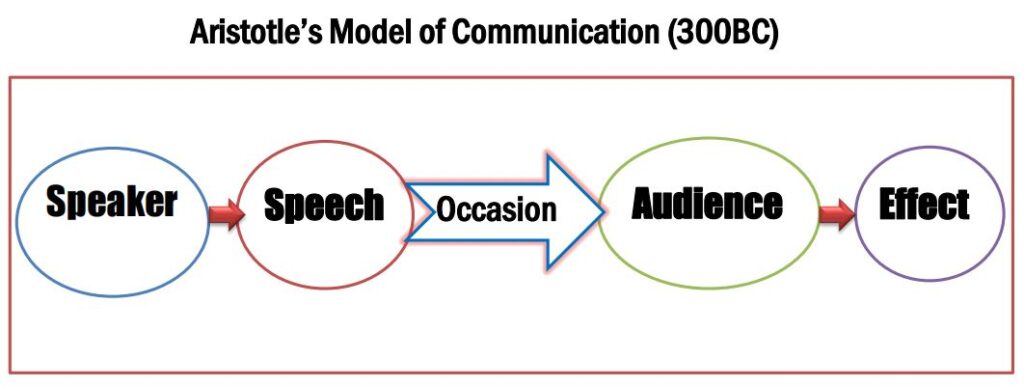

Aristotle, a great philosopher initiative the earliest mass communication model called “Aristotle’s Model of Communication”. He proposed model before 300 B.C who found the importance of audience role in communication chain in his communication model. This model is more focused on public speaking than interpersonal communication.

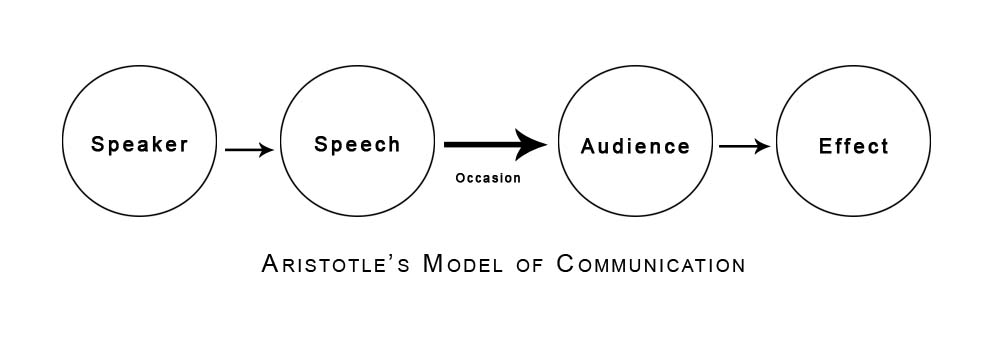

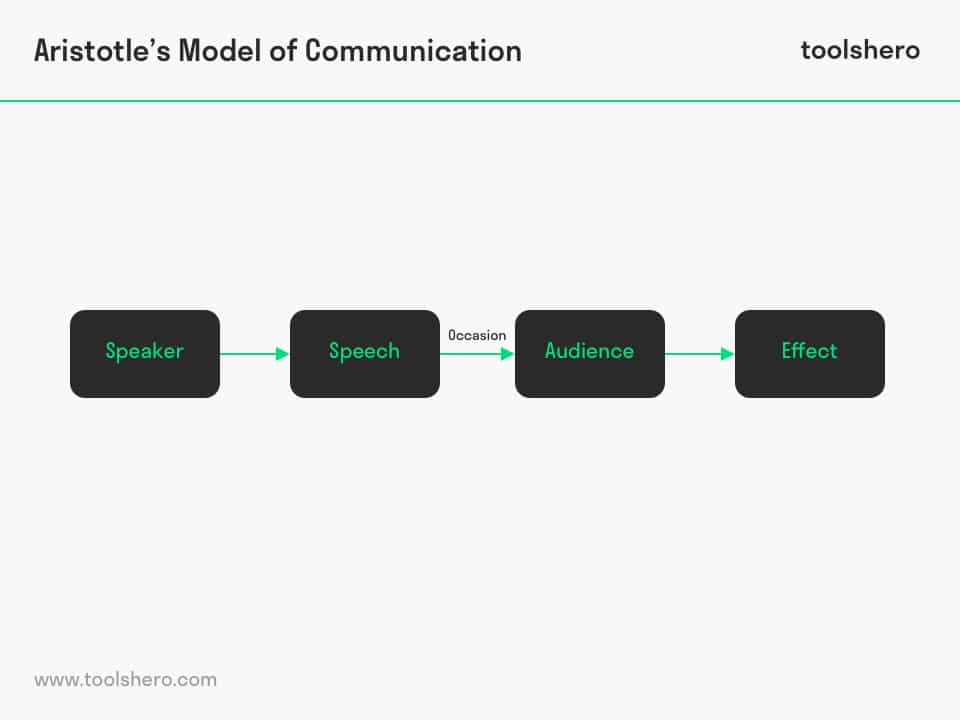

Aristotle Model of Communication is formed with 5 basic elements

(i) Speaker, (ii) Speech, (iii) Occasion, (iv) Audience and (v) Effect.

Aristotle advises speakers to build speech for different audience on different time (occasion) and for different effects.

Speaker plays an important role in Public speaking. The speaker must prepare his speech and analysis audience needs before he enters into the stage. His words should influence in audience mind and persuade their thoughts towards him.

Alexander gave brave speech to his soldiers in the war field to defeat Persian Empire.

Speaker – Alexander

Speech – about his invasion

Occasion – War field

Audience – Soldiers

Effect – To defeat Persia

Related Posts:

- Limited Effects Theory

- Knapp’s Relationship Model

- BERLO'S SMCR MODEL OF COMMUNICATION

- Westley and MacLean’s Model of Communication

- De Fleur Model of Communication

- SOCIAL IDENTITY THEORY

put more information pliz aristotle bt its gud work really appriciate it thank yu

I understand the model clearly. thx

great work, as it take into consideration effect

I’m subversively impressed by the works of Aristotle though more could have been given on the negative dimension of the model

Thanks for your clear explanation… How about merits and demerits’ of this mode

i think this is allwrong and everybody who thinks diferent needs to do more reasearvh cause Aristotle is stupid

Aristotle wrote two thousand four hundred years ago but his clear and logical insights are still foundations for communications theory, as they are in theater (another form of communication ) as well. Besides writing on communications in the last four thousand years(!) there has certainly been a lot of really insightful work done in the last thirty years -in fact, I was amazed when I revisited the field recently, how much insightful and useful theory and investigation HAS taken place in these last thirty years.

thanks a lot , i now understand the theory clearly

how come my communication skills lecturer only mentioned three elements of the Aristotle model of communication i.e speaker-speech-audience?

Communication simply sharing idea

thank u so much i have got more than what i needed ur the best

I want to know more about this and in hence my brain wise

well researched have been assisted a lot thank you

I want to know more about this model communication so that I can enhance my knowledge….

I like cuz it has so many information 🙂

Well understood model

I understand the models so vividly. he gave a very important and fine explanation on communication. thanks to him.

model is too biased cause its largely one way communication

The model is explained in the simplest way that anyone can be in position to understand. I like it.

its good of know about the ancient way of communication, but put most recent for us to learn better. you’ve done well. thanks

pls add more information

Thanks so much

some senses surely…tnx

there is no consideration of feedback but is a good explanation,,,kudos to him

more source

Aristotle’s theory was groundbreaking during its time; it put so much power on the speaker and little on the audience. However, later day theories are conscious of the other major elements in the communication process, such as audience effect as well as barriers to communication resulting from siurce, channel or receiver. These important components were scarecely considered in Aristotelian theory. If the theory has any drawbacks, these could be some of them.

thanks so much eish…….that was the only thing that was likely to hinder me from getting my distinction but now i know uuum…..Thanks so much

Good exposition

Thanks for your explanation

It’s a awesome explanation and detailed very understandable

You didn’t give the basic explanation Arustotle’s communication model is sender based with four elements The sender The message The receiver and The Effect The main function is to persuade the other party irrespective of the feedback It dwells on the sender nit caring how the receiver receives the message.

i understand the model now but what are the limitations of this model

It’s very good and easy to understand,thanks but add more content like ways to improve this model of communication

And isn’t it STRANGE that NOBODY ever CHALLENGED Aristotle on his falsifiable assumption. He does not describe or define communicating, but sendership and listenership among human beings. No accountable science uses Classical philosophy as its bottomline… So why do professors in propaganda still do so?

Thankyou for the explanation

Leave a Comment

Next post: Shannon and Weaver Model of Communication

Previous post: Management by objectives (Drucker)

- Advertising, Public relations, Marketing and Consumer Behavior

- Business Communication

- Communication / General

- Communication Barriers

- Communication in Practice

- Communication Models

- Cultural Communication

- Development Communication

- Group Communication

- Intercultural Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Mass Communication

- Organisational Communication

- Political Communication

- Psychology, Behavioral And Social Science

- Technical Communication

- Visual Communication

Communication Theory

- Memberships

Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle Model of Communication: this article provides a practical explanation of the Aristotle Model of Communication . The article contains the definition of the Aristotle Model of Communication, and example of the diagram and practical tips. Enjoy reading!

What is Aristotle Model of Communication?

It was Aristotle who first proposed and wrote about a unique model of communication.

Today, his model is referred to as the Aristotle Model of Communication. The great philosopher Aristotle already created this linear model before 300 BC, placing more emphasis on public speaking than on interpersonal communication.

The simple model is presented in a diagram and is still widely used in preparing seminars, lectures and speeches to this day.

Aristotle model of communication diagram

The Aristotle Model of Communication diagram can roughly be divided into five elements. The speaker is the most important element, making this model a speaker-oriented model.

Figure 1 – Aristotle model of communication diagram

Aristotle Model of Communication: the Role of the Speaker

According to the Aristotle Model of Communication, the speaker is the main figure in communication. This person is fully responsible for all communication. In this model of communication, it is important that the speaker selects his words carefully.

He or she must analyse his audience and prepare his speech accordingly. At the same time, he or she should assume the right body language, as well as ensuring proper eye contact and voice modulations.

In order to entice the audience, blank expressions, confused looks, and monotonous speech must be avoided at all times. The audience must believe in the speaker’s ability to easily put his money where his mouth is.

A politician (the speaker) gives a speech on a market square during an election campaign (the occasion). His goal is the win the votes of the citizens (the audience) present as well as those of the citizens potentially watching the speech on TV.

The people will vote (the effect) for the politician if they believe in his views. At the same time, the way in which he presents his story is crucial in convincing his audience.

The politician talks about his party’s standpoints and will probably be familiar with his audience. In other situations, it would be more suitable to actively research the audience in advance and determine their potential viewpoints or opinions.

The Rhetorical Triangle

The rhetorical triangle is essentially a method to organise and distinguish the three elements of rhetoric. The rhetorical triangle consists of three convincing strategies, to be used in direct communication situations.

Aristotle did not use a triangle himself in the Aristotle Model of Communication, but effectively described the three modes of persuasion , namely logos, pathos, and ethos.

These modes of persuasion always influence each other during conversations in which arguments are shared back and forth, but also in one-way communication, such as during speeches.

Figure 2 – Aristotle’s Triangle of Reference

Ethos is about the writer or speaker’s credibility and degree of authority, especially in relation to the subject at hand. A doctor’s ethos is the result of years of study and training. Due to his qualifications, a doctor’s words involve a significant degree of authority.

One’s ethos can be damaged in the blink of an eye, however. For example, the reputable politician may be found out when corruption scandals come to light and his private life turns out to be in complete contrast with his political standpoints. Tips for building ethos in communication:

- Use words that suit the target group

- Keep communication professional

- Conduct research before words are presented as facts

- Use recommendations from qualified experts

- Make logical connections and avoid fallacies

The literal translation of pathos is emotion. In the rhetoric, pathos refers to the audience and the way in which they react to the speaker’s message, the center in the Aristotle Model of Communication.

The idea behind pathos is that the audience must feel that they are communicated with. In certain situations, they want to feel more confident, in others more sad, angry, or emotional.

Before and during the Second World War, Adolf Hitler gave many speeches in front of tens of thousands of people. His words and particular pronunciation made his audience feel attracted to him. Pathos, emotion, can therefore also be abused. For example, people may become anxious as a result of the false consequences of not buying a product presented in the sales world.

The question of whether emotions may be manipulated in sales strategies is a sensitive one. When collecting money for charities, this is somewhat socially acceptable.

However, when selling products or services, many people will express their doubts. Nevertheless, capitalising on pathos can be very effective.

Tips for effectively addressing emotions:

- People’s involvement is stimulated by humour. Always keep different types of humour in mind, though

- Use images or other visual materials to evoke strong emotions

- Pay attention to the intonation and tempo of one’s voice in order to elicit enthusiasm or anxiety

The direct translation of logos is logic, but in rhetoric it more broadly refers to the speaker’s message and more specifically the facts, statements, and other elements that comprise the argument.

According to the Aristotle model of communication, logos is the most important part of one’s argument. For this reason, it is crucial that sales talks always emphasise this particular element.

The appeal to logic also means that paragraphs and arguments must be properly ordered. Facts, statistics and logical reasoning are especially important here. When analysing logos, always ask yourself:

- What is the context? What conditions are relevant?

- What are the potential counter-arguments?

- Is there any evidence that supports my argument? Always mention this

- Do I correctly avoid generalisations and am I being specific enough?

The Complete Communication Skills Master Class for Life More information

An Example of Proper Use of Rhetoric

One man who understood rhetoric very well and applied it effectively was Steve Jobs , founder of Pixar Animation, NeXT, and Apple. He also applied the Aristotle model of communication effectively. This business guru stands head and shoulders above others of his generation in terms of communication techniques.

Much research has been conducted into the ways in which he used to communicate a constant series of messages and themes about his company’s products and his vision of the future.

Communication experts especially distinguish Steve Jobs’ ethos. His degree of ethos, or credibility, had a major influence on how he used logos and pathos.

If ethos was low, Steve Jobs would use high levels of pathos and low levels of logos. If ethos was high, he would use low levels of pathos and high levels of logos.

In addition to effective use of the rhetorical triangle, Jobs also used a mix of rhetorical strategies such as repetition, re-stirring of discussions to suit his vision and goals, and amplification. Amplification refers to a literary technique in which the user enhances a series of words by adding information to increase their value and comprehensibility.

Criticism of Aristotle Model of Communication

Despite the fact that at first glance there does not seem much wrong with Aristotle’s communication model, there are important points of criticism of the model.

The main point of communication is that the model considers a directional process, from speaker to receiver.

In reality, it is a dynamic process in which both the speaker and receiver are active. Evidence for this can be found, for example, in the technology of eavesdropping.

Because of the above, the model is useless in many situations because the feedback is not included.

Now it’s your turn

What do you think? Are you familiar with the Aristotle model of communication? How do you think you can use this information to improve your communication skills? Do you have any additional tips for effective communication? Do you have any other suggestions or additions?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Kallendorf, C., & Kallendorf, C. (1985). The figures of speech, ethos, and Aristotle: Notes toward a rhetoric of business communication . The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 22(1), 35-50.

- Griffin, E. M. (2006). A first look at communication theory . McGraw-Hill .

- Braet, A. C. (1992). Ethos, pathos and logos in Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A re-examination . Argumentation, 6(3), 307-320.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2018). Aristotle Model of Communication . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/aristotle-model-of-communication/

Original publication date: 10/07/2018 | Last update: 11/08/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/communication-methods/aristotle-model-of-communication/a>Toolshero: Aristotle Model of Communication</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.8 / 5. Vote count: 19

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Ladder of Abstraction (Hayakawa)

Dialogue Mapping by Jeff Conklin: a Summary

7 C’s of Communication Theory

Social Intelligence (SI) explained

Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS)

Impression Management Theory by Erving Goffman

Also interesting.

David Berlo’s SMCR Model of Communication explained

Storytelling Method: Basics and Steps

Core Quality Quadrant Model explained

2 responses to “aristotle model of communication”.

It would be great if we find Criticism of this model.

Yes we do have some criticisms of this model 1. There is no concept of feedback, it is one way from the speaker to the audience. 2. There is no concept of communication failures like noise and barriers. 3. This model can only be used in public speaking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

Aristotle Model of Communication: Advantages and Disadvantages

Aristotle contributed significantly to the field of rhetoric and communication through his work on persuasive communication and effective argumentation. Aristotle did not provide a single, comprehensive definition of communication in the way that modern communication scholars might. However, his works, particularly those related to rhetoric, contain insights into how he understood the process of communication. In Aristotle’s view, communication is primarily concerned with persuasive discourse and the art of effective persuasion. He emphasized the role of rhetoric in communication, which involves using language and argumentation to influence an audience’s beliefs, attitudes, and actions.

Definition of Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle’s communication theories , often discussed in his work “Rhetoric” (4th century BCE), revolve around the art of persuasion and the means by which people can influence others through speech and discourse. He outlined three main components of persuasive communication that include:

- Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

Persuasion and Audience Analysis

Aristotle defined rhetoric as the faculty of discovering the available means of persuasion in a given situation. It involves crafting persuasive messages and arguments that are tailored to the audience’s characteristics and emotions. Rhetoric is not just about conveying information, but also about convincing and persuading others. Alongside that, ethos, pathos, and logos are the three persuasive appeals that Aristotle identified as essential components of effective communication.

This refers to the speaker’s credibility and character. A persuasive message is more effective when it comes from someone who is perceived as trustworthy, knowledgeable, and morally upright.

Pathos appeals to the audience’s emotions. Aristotle believed that emotions play a crucial role in persuasion, and a communicator can effectively sway an audience by evoking specific emotional responses through their speech.

Logos refers to the logical appeal of an argument. Communicators should present a well-structured and reasoned argument, using evidence and reasoning to support their claims.

Aristotle emphasized the importance of understanding the audience’s beliefs, values, and emotions. Effective communication requires adapting the message to the specific characteristics of the audience.

While Aristotle’s focus was more on the art of persuasion and rhetoric, his ideas have had a lasting impact on communication theory and practice. His insights into understanding the audience, using emotions, and crafting compelling arguments continue to influence how we think about communication strategies and persuasive discourse.

Elements of Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle’s communication model, although not explicitly presented in a modern diagrammatic form, can be understood through his concepts related to persuasive communication and rhetoric. Here are five key elements that represent Aristotle’s communication model:

Speaker (Rhetor)

The communicator or speaker is a central figure in Aristotle’s communication model. The speaker is responsible for crafting and delivering persuasive messages to the audience. The speaker’s credibility (ethos), ability to evoke emotions (pathos), and use of logical arguments (logos) play essential roles in influencing the audience.

Message (Logos)

The message is the content of communication. Aristotle emphasized the importance of constructing a well-structured and logically sound argument. This involves presenting evidence, reasoning, and examples to support the speaker’s claims and persuade the audience of a particular viewpoint.

Audience (Listener/Viewer)

The audience is a crucial component of the communication process. Aristotle emphasized the significance of analyzing the audience’s characteristics, beliefs, emotions, and values. Effective communication requires tailoring the message to resonate with the audience’s interests and persuading them based on their specific context.

In Aristotle’s model of communication, the “occasion” refers to the specific context or situation in which communication takes place. While the concept of occasion is not always explicitly discussed in his works, it is an important element that underlies his ideas about persuasive communication and rhetoric. Aristotle believed that effective communication requires a deep understanding of the occasion, including factors such as the audience, the purpose of communication, the cultural and social context, and the timing of the message. The occasion influences how the speaker tailors their message to connect with the audience and achieve the desired persuasive outcome.

In Aristotle’s model of communication, the concept of “effect” refers to the intended impact or outcome of persuasive communication. It is one of the fundamental elements that the speaker aims to achieve through effective rhetoric and persuasive discourse. Aristotle’s focus on effect underscores the goal-oriented nature of communication, where the speaker seeks to influence the audience’s beliefs, attitudes, and actions.

These five elements—speaker, message, audience, occasion, and effect—form the core components of Aristotle Model of Communication, which revolves around the art of persuasion and effective discourse.

Explore the seven essential steps in the communication process .

Diagram of Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle’s model of communication is not typically represented in a diagrammatic form like modern communication models. However, here is a simplified diagram that captures the key elements and relationships in Aristotle’s model:

Please note that this diagram simplifies the model for visualization purposes. In reality, the interactions between the elements are more complex and dynamic. The model emphasizes the interplay between the speaker’s use of ethos, pathos, and logos to craft a message tailored to the audience and occasion, with the ultimate goal of achieving a desired persuasive effect.

Advantages of Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle’s model of communication, rooted in the principles of rhetoric and persuasive discourse, offers several advantages that continue to be relevant and applicable in various communication contexts. Some of the advantages of Aristotle’s model include:

Emphasis on Persuasion

Aristotle’s model places a strong emphasis on persuasive communication. It provides insights into how to effectively influence and persuade an audience through the strategic use of ethos, pathos, and logos. This focus on persuasion is valuable in fields such as public speaking, marketing, advertising, and politics.

Holistic Understanding

The model considers multiple elements, including the speaker, message, audience, ethos, pathos, and logos. This holistic approach recognizes that effective communication is a complex interplay of various factors. It encourages communicators to consider all these elements when crafting their messages.

Adaptability to Context

Aristotle’s model highlights the importance of analyzing the occasion, audience, and purpose of communication. This adaptability allows communicators to tailor their messages to specific situations and audiences, making the model suitable for diverse contexts.

Focus on Ethical Communication

The concept of ethos in Aristotle’s model promotes ethical communication. Speakers are encouraged to establish credibility and maintain moral integrity, fostering a sense of trust and authenticity in their interactions with the audience.

Emotional Appeal

The emphasis on pathos acknowledges the role of emotions in communication. This aspect is particularly relevant for creating emotional connections, engaging audiences, and making messages memorable.

Logical Argumentation

The inclusion of logos encourages the use of logical reasoning and evidence-based argumentation. This can enhance the persuasiveness of a message by providing a solid foundation for the claims being made.

Timeless Principles

While Aristotle’s model was developed over two millennia ago, its core principles remain timeless. Concepts like credibility, emotional appeal, and logical reasoning are still central to effective communication today.

Foundation for Communication Studies

Aristotle’s model laid the groundwork for the study of communication and rhetoric. It continues to be a foundational text in communication education and theory, providing a historical context for understanding the evolution of communication scholarship.

Read about Lasswell’s Model of Communication .

Audience-Centered Approach

The model encourages communicators to analyze and adapt to the audience’s characteristics and preferences. This audience-centered approach is valuable for tailoring messages to resonate with the intended recipients.

Explore the Two-Step Flow Theory .

Flexibility and Creativity

Aristotle’s model does not prescribe a rigid step-by-step process, allowing communicators to exercise creativity and adaptability in their communication strategies.

While Aristotle’s model may not encompass the complexities of modern communication, it offers enduring insights into the art of persuasion and effective discourse, making it a valuable framework for understanding and improving communication practices.

Disadvantages of Aristotle Model of Communication

While Aristotle’s model of communication offers valuable insights into persuasion and rhetoric, it also has certain limitations that need to be acknowledged in contemporary communication contexts:

Simplicity and Incompleteness

Aristotle’s model is relatively simple and focuses primarily on persuasion. It lacks the comprehensive structure and detail found in modern communication models, which consider various elements such as feedback, noise, and multiple channels of communication.

Limited Interactivity

The model does not adequately address interactive communication, such as two-way conversations, dialogue, or online interactions, which are common in today’s communication landscape.

Cultural and Contextual Variation

Aristotle’s model does not fully account for the influence of cultural diversity and contextual differences in communication. It assumes a relatively uniform audience response without accounting for variations in cultural norms and values.

Bias Toward Oratory

The model was developed in the context of persuasive oratory and rhetoric, which may limit its applicability to other forms of communication, such as interpersonal, organizational, and mediated communication.

Overemphasis on Persuasion

While persuasion is a central aspect of Aristotle’s model, not all communication situations involve the intent to persuade. The model may not fully capture communication for the purpose of sharing information, expressing emotions, or building relationships.

Discover the Agenda-Setting Theory .

Lack of Contemporary Technological Considerations

The model was conceived long before the advent of modern communication technologies. It does not address the role of digital media, social platforms, or the complexities introduced by electronic communication channels.

Limited Role of Feedback

The model does not explicitly incorporate feedback, which is crucial for understanding how messages are received and interpreted by the audience. Feedback is often a dynamic and ongoing process in communication.

Assumption of Rational Audience

The model assumes that audiences are rational and respond primarily to logical arguments. In reality, emotions, biases, and cognitive heuristics can play a significant role in shaping audience responses.

Read about the advantages and disadvantages of Cultivation Theory .

Neglect of Nonverbal Communication

The model primarily focuses on verbal communication and logical arguments, neglecting the important role of nonverbal cues, body language, and visual elements in communication.

Static Nature

The model presents communication as a one-time event, not accounting for ongoing conversations, evolving relationships, or the iterative nature of communication processes.

Normative Approach

Aristotle’s model can be seen as somewhat prescriptive, focusing on the ideal elements of persuasive communication. It may not fully encompass the complexities and variations in actual communication practices.

While Aristotle’s model remains influential and provides foundational principles for persuasive communication, it should be used in conjunction with more comprehensive and contemporary communication models to account for the complexities of modern communication contexts.

Examples of Aristotle Model of Communication

Here are a few examples that illustrate how Aristotle Model of Communication can be applied in various real-life scenarios:

Political Speech

A politician giving a campaign speech aims to persuade the audience to vote for them. The speaker establishes credibility (ethos) by highlighting their experience and values, evokes emotions (pathos) by sharing personal stories or discussing pressing issues, and presents logical arguments (logos) by outlining their policy proposals and providing evidence of their effectiveness.

Advertising Campaign

An advertisement for a new smartphone emphasizes the credibility of the brand (ethos) by showcasing its reputation for quality. The ad uses emotional appeal (pathos) by depicting scenes of people enjoying the phone’s features and benefits. It also employs logical reasoning (logos) by highlighting the phone’s specifications and technological advancements.

Read about the DAGMAR and AIDA models in advertising .

Motivational Speech

A motivational speaker addresses a group of students. The speaker establishes credibility (ethos) by sharing their personal journey of overcoming challenges. They use emotional appeal (pathos) by recounting inspirational stories and encouraging the audience to believe in themselves. Logical arguments (logos) are presented through practical steps and strategies for achieving success.

Public Service Announcement

An anti-smoking campaign targets teenagers. The message focuses on establishing credibility (ethos) by featuring testimonials from former smokers who successfully quit. Emotional appeal (pathos) is used by showing the negative health consequences of smoking and the impact on loved ones. Logical reasoning (logos) is employed through statistical data and medical facts about smoking-related illnesses.

Explore the pros and cons of the Magic Bullet Theory .

Corporate Presentation

A company presents a proposal to potential investors. The company’s CEO establishes credibility (ethos) by showcasing the company’s track record and expertise in the industry. Emotional appeal (pathos) is integrated by highlighting the company’s commitment to innovation and positive societal impact. Logical arguments (logos) are provided through financial projections, market analysis, and the potential for growth.

Debate Competition

Two debaters argue for and against a specific motion. Each debater builds credibility (ethos) by demonstrating their knowledge of the subject matter. Emotional appeal (pathos) is used to evoke empathy for the potential consequences of their opponent’s stance. Logical reasoning (logos) is presented through well-researched arguments, statistics, and counterarguments.

These examples showcase how the elements of ethos, pathos, and logos from Aristotle’s model are integrated into various communication situations to influence, persuade, and engage the audience. While the specific context and goals may vary, the underlying principles of effective communication remain consistent in their application.

Aristotle’s model of communication, though originating over two millennia ago, remains an enduring framework that offers valuable insights into the art of persuasion and effective discourse. Rooted in the principles of rhetoric, this model highlights the intricate dance between the speaker, the message, the audience, and the context. Through ethos, pathos, and logos, Aristotle recognized the power of credibility, emotion, and logical reasoning in shaping persuasive communication.

While the model may appear simplistic compared to modern communication theories , it serves as a foundational cornerstone for understanding the dynamics of communication. Its emphasis on adapting messages to the occasion and audience underscores the importance of context awareness in crafting influential discourse. Aristotle’s legacy endures as his model continues to inspire and influence communication practices and theories.

Aristotle’s Model of Communication centers on persuasive discourse, emphasizing the strategic interplay of ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logical argument) to influence audiences. Rooted in rhetoric, this model underscores the speaker’s role in tailoring messages to context and audience, aiming for a desired effect. While simplistic by modern standards, its enduring focus on persuasion, credibility, emotional appeal, and logical reasoning continues to shape communication theories and practice, albeit with limitations in addressing contemporary complexities like interactivity, cultural diversity, and nonverbal communication.

Aristotle’s Model of Communication operates through the strategic integration of ethos (speaker credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argument) to persuade an audience. The speaker adapts messages to the occasion and audience, establishing credibility, evoking emotions, and presenting reasoned arguments. By tailoring communication to context, the model seeks to achieve a desired effect, influencing beliefs, attitudes, and actions. Though straightforward, it lacks modern complexities like interactivity and feedback. Nonetheless, its enduring principles of persuasion and effective discourse continue to guide communication practices, transcending time and cultures.

In Aristotle’s Model of Communication, the speech is dependent on the occasion and the audience because effective persuasion requires a tailored approach. The occasion defines the context, purpose, and timing of the communication, influencing the message’s relevance and impact. Understanding the audience’s characteristics, beliefs, and emotions is essential to crafting messages that resonate. Ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logical argument) must be strategically balanced to suit the audience’s context and preferences. By adapting the speech to the occasion and audience, communicators maximize the chances of achieving the desired persuasive effect and fostering a meaningful connection with those they seek to influence.

The Aristotle Model of Communication remains important due to its foundational insights into persuasive discourse and effective communication. It emphasizes ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argument) as key factors for successful persuasion. By recognizing the significance of tailoring messages to the occasion and audience, the model offers timeless guidance for crafting impactful communication. While simplified compared to modern theories, its focus on credibility, emotion, and logic continues to influence various fields, fostering a better understanding of how to engage and persuade audiences.

Aristotle’s Model of Communication is distinctive for its emphasis on persuasive discourse and the art of rhetoric. It uniquely integrates ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical argument) to influence audiences. Its focus on tailoring messages to the occasion and audience highlights context awareness. While simplified, its enduring principles continue to guide effective communication. The model’s historical significance, rooted in ancient Greek philosophy, sets it apart as a foundational framework that shapes an understanding of persuasion and discourse, providing a basis for exploring human interaction, credibility, emotion, and logical reasoning across time and cultures.

Similar Posts

Multi-Step Flow Theory: Definition & Examples

Explore the Multi-Step Flow Theory and the dynamics of information dissemination through opinion leaders, shaping public opinion.

Media Dependency Theory: Strengths and Weaknesses

Explore the strengths and weaknesses of the Media Dependency Theory and understand its relevance in modern society.

Mass Communication Theories and Models

Explore six fundamental theories and models of mass communication. This article includes their definitions and examples.

Osgood-Schramm Model of Communication: Definition & Examples

The Osgood-Schramm Model emphasizes sender-message-receiver dynamics, feedback, context, and noise in human communication interactions.

Gatekeeping Theory in Mass Communication

Gatekeeping theory explores how media professionals control information flow, shaping public perceptions through selection, filtering, and framing.

Lasswell’s Model of Communication: Advantages and Disadvantages

Explore the pros and cons of Lasswell’s Model of Communication. Discover not only its simplicity but also its limitations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Organizational Behaviour

- Communication - Basics & Strategies

- Aristotle Model of Communication

Aristotle was the first to take an initiative and design the communication model.

Let us first go through a simple situation.

In a political meeting, the prospective leader delivers speech to the audience urging for more votes from the constituency. He/She tries to convince the crowd in the best possible way He/She can so that He/She emerges as a winner. What is He/She actually doing?

He/She is delivering his speech in a manner that the listeners would get convinced and cast their votes only in his favour, or in other words respond in the same manner the speaker wanted to.

Here the leader or the speaker or the sender is the centre of attraction and the crowd simply the passive listeners.

The example actually explains the Aristotle model of communication.

According to this model, the speaker plays a key role in communication . He/She is the one who takes complete charge of the communication. The sender first prepares a content which he does by carefully putting his thoughts in words with an objective of influencing the listeners or the recipients, who would then respond in the sender’s desired way.

No points in guessing that the content has to be very very impressive in this model for the audience or the receivers to get convinced.

The model says that the speaker communicates in such a way that the listeners get influenced and respond accordingly.

The speaker must be very careful about his selection of words and content in this model of communication. He/She should understand his target audience and then prepare his speech.

Making eye contact with the second party is again a must to create an impact among the listeners. Let us again go through the first example.

The politician must understand the needs of the people in his constituency like the need of a shopping mall, better transport system, safety of girls etc and then design his speech.

His/Her speech should address all the above issues and focus on providing the solutions to their problems to expect maximum votes from them.

Voice tone and pitch should also be loud and clear enough for the people to hear and understand the speech properly. Stammering, getting nervous in between of a conversation must be avoided.

Voice modulations also play a very important role in creating the desired effect. Blank expressions, confused looks and similar pitch all through the speech make it monotonous and nullify its effect.

The speaker should know where to lay more stress on, highlight which words to influence the listeners.

One will definitely purchase the mobile handset from that store where the sales man gives an impressive demo of the mobile.

It depends on the sales man what to speak and how to speak in a manner to influence the listeners so that they respond to him in a way he actually wants i.e. purchase the handset and increase his billing.

The Aristotle model of communication is the widely accepted and the most common model of communication where the sender sends the information or a message to the receivers to influence them and make them respond and act accordingly.

Aristotle model of communication is the golden rule to excel in public speaking, seminars, lectures where the sender makes his point clear by designing an impressive content, passing on the message to the second part and they simply respond accordingly. Here the sender is the active member and the receiver is passive one.

Related Articles

- Overview of Phonetics & Homophones

- Communication Theory

- Communication Models

- Berlo’s Model of Communication

- Shannon and Weaver Model

View All Articles

Authorship/Referencing - About the Author(s)

The article is Written and Reviewed by Management Study Guide Content Team . MSG Content Team comprises experienced Faculty Member, Professionals and Subject Matter Experts. We are a ISO 2001:2015 Certified Education Provider . To Know more, click on About Us . The use of this material is free for learning and education purpose. Please reference authorship of content used, including link(s) to ManagementStudyGuide.com and the content page url.

- Communication - Introduction

- Types of Communication

- Normal vs Effective Communication

- Role of Effective Communication

- Theories of Organizational Communication

- Schramm’s Model of Communication

- Helical Model of Communication

- Westley & MacLean’s Model

- Barriers of Communication

- Strategies to Improve Communication

- Communication Skills at Workplace

- Communication Skills of an Individual

- Communication in Group Discussion

- Tips for Group Discussion

- Preparing a Presentation

- Communication in Presentation

- Understanding Communication System

- Types of Communication Systems

- Digital Communication System

- Laser Communication System

- Satellite Communication System

- Network Society - Rise of Digital Networks

- Effective communication strategy at workplace

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) numbers among the greatest philosophers of all time. Judged solely in terms of his philosophical influence, only Plato is his peer: Aristotle’s works shaped centuries of philosophy from Late Antiquity through the Renaissance, and even today continue to be studied with keen, non-antiquarian interest. A prodigious researcher and writer, Aristotle left a great body of work, perhaps numbering as many as two-hundred treatises, from which approximately thirty-one survive. [ 1 ] His extant writings span a wide range of disciplines, from logic, metaphysics and philosophy of mind, through ethics, political theory, aesthetics and rhetoric, and into such primarily non-philosophical fields as empirical biology, where he excelled at detailed plant and animal observation and description. In all these areas, Aristotle’s theories have provided illumination, met with resistance, sparked debate, and generally stimulated the sustained interest of an abiding readership.

Because of its wide range and its remoteness in time, Aristotle’s philosophy defies easy encapsulation. The long history of interpretation and appropriation of Aristotelian texts and themes—spanning over two millennia and comprising philosophers working within a variety of religious and secular traditions—has rendered even basic points of interpretation controversial. The set of entries on Aristotle in this site addresses this situation by proceeding in three tiers. First, the present, general entry offers a brief account of Aristotle’s life and characterizes his central philosophical commitments, highlighting his most distinctive methods and most influential achievements. [ 2 ] Second are General Topics , which offer detailed introductions to the main areas of Aristotle’s philosophical activity. Finally, there follow Special Topics , which investigate in greater detail more narrowly focused issues, especially those of central concern in recent Aristotelian scholarship.

1. Aristotle’s Life

2. the aristotelian corpus: character and primary divisions, 3. phainomena and the endoxic method, 4.2 science, 4.3 dialectic, 5. essentialism and homonymy, 6. category theory, 7. the four causal account of explanatory adequacy, 8. hylomorphism, 9. aristotelian teleology, 10. substance, 11. living beings, 12. happiness and political association, 13. rhetoric and the arts, 14. aristotle’s legacy, a. translations, b. translations with commentaries, c. general works, d. bibliography of works cited, other internet resources, related entries.

Born in 384 B.C.E. in the Macedonian region of northeastern Greece in the small city of Stagira (whence the moniker ‘the Stagirite’, which one still occasionally encounters in Aristotelian scholarship), Aristotle was sent to Athens at about the age of seventeen to study in Plato’s Academy, then a pre-eminent place of learning in the Greek world. Once in Athens, Aristotle remained associated with the Academy until Plato’s death in 347, at which time he left for Assos, in Asia Minor, on the northwest coast of present-day Turkey. There he continued the philosophical activity he had begun in the Academy, but in all likelihood also began to expand his researches into marine biology. He remained at Assos for approximately three years, when, evidently upon the death of his host Hermeias, a friend and former Academic who had been the ruler of Assos, Aristotle moved to the nearby coastal island of Lesbos. There he continued his philosophical and empirical researches for an additional two years, working in conjunction with Theophrastus, a native of Lesbos who was also reported in antiquity to have been associated with Plato’s Academy. While in Lesbos, Aristotle married Pythias, the niece of Hermeias, with whom he had a daughter, also named Pythias.

In 343, upon the request of Philip, the king of Macedon, Aristotle left Lesbos for Pella, the Macedonian capital, in order to tutor the king’s thirteen-year-old son, Alexander—the boy who was eventually to become Alexander the Great. Although speculation concerning Aristotle’s influence upon the developing Alexander has proven irresistible to historians, in fact little concrete is known about their interaction. On the balance, it seems reasonable to conclude that some tuition took place, but that it lasted only two or three years, when Alexander was aged from thirteen to fifteen. By fifteen, Alexander was apparently already serving as a deputy military commander for his father, a circumstance undermining, if inconclusively, the judgment of those historians who conjecture a longer period of tuition. Be that as it may, some suppose that their association lasted as long as eight years.

It is difficult to rule out that possibility decisively, since little is known about the period of Aristotle’s life from 341–335. He evidently remained a further five years in Stagira or Macedon before returning to Athens for the second and final time, in 335. In Athens, Aristotle set up his own school in a public exercise area dedicated to the god Apollo Lykeios, whence its name, the Lyceum . Those affiliated with Aristotle’s school later came to be called Peripatetics , probably because of the existence of an ambulatory ( peripatos ) on the school’s property adjacent to the exercise ground. Members of the Lyceum conducted research into a wide range of subjects, all of which were of interest to Aristotle himself: botany, biology, logic, music, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, cosmology, physics, the history of philosophy, metaphysics, psychology, ethics, theology, rhetoric, political history, government and political theory, and the arts. In all these areas, the Lyceum collected manuscripts, thereby, according to some ancient accounts, assembling the first great library of antiquity.

During this period, Aristotle’s wife, Pythias, died and he developed a new relationship with Herpyllis, perhaps like him a native of Stagira, though her origins are disputed, as is the question of her exact relationship to Aristotle. Some suppose that she was merely his slave; others infer from the provisions of Aristotle’s will that she was a freed woman and likely his wife at the time of his death. In any event, they had children together, including a son, Nicomachus, named for Aristotle’s father and after whom his Nicomachean Ethics is presumably named.

After thirteen years in Athens, Aristotle once again found cause to retire from the city, in 323. Probably his departure was occasioned by a resurgence of the always-simmering anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens, which was free to come to the boil after Alexander succumbed to disease in Babylon during that same year. Because of his connections to Macedon, Aristotle reasonably feared for his safety and left Athens, remarking, as an oft-repeated ancient tale would tell it, that he saw no reason to permit Athens to sin twice against philosophy. He withdrew directly to Chalcis, on Euboea, an island off the Attic coast, and died there of natural causes the following year, in 322. [ 3 ]

Aristotle’s writings tend to present formidable difficulties to his novice readers. To begin, he makes heavy use of unexplained technical terminology, and his sentence structure can at times prove frustrating. Further, on occasion a chapter or even a full treatise coming down to us under his name appears haphazardly organized, if organized at all; indeed, in several cases, scholars dispute whether a continuous treatise currently arranged under a single title was ever intended by Aristotle to be published in its present form or was rather stitched together by some later editor employing whatever principles of organization he deemed suitable. [ 4 ] This helps explain why students who turn to Aristotle after first being introduced to the supple and mellifluous prose on display in Plato’s dialogues often find the experience frustrating. Aristotle’s prose requires some acclimatization.

All the more puzzling, then, is Cicero’s observation that if Plato’s prose was silver, Aristotle’s was a flowing river of gold ( Ac. Pr. 38.119, cf. Top . 1.3, De or. 1.2.49). Cicero was arguably the greatest prose stylist of Latin and was also without question an accomplished and fair-minded critic of the prose styles of others writing in both Latin and Greek. We must assume, then, that Cicero had before him works of Aristotle other than those we possess. In fact, we know that Aristotle wrote dialogues, presumably while still in the Academy, and in their few surviving remnants we are afforded a glimpse of the style Cicero describes. In most of what we possess, unfortunately, we find work of a much less polished character. Rather, Aristotle’s extant works read like what they very probably are: lecture notes, drafts first written and then reworked, ongoing records of continuing investigations, and, generally speaking, in-house compilations intended not for a general audience but for an inner circle of auditors. These are to be contrasted with the “exoteric” writings Aristotle sometimes mentions, his more graceful compositions intended for a wider audience ( Pol. 1278b30; EE 1217b22, 1218b34). Unfortunately, then, we are left for the most part, though certainly not entirely, with unfinished works in progress rather than with finished and polished productions. Still, many of those who persist with Aristotle come to appreciate the unembellished directness of his style.

More importantly, the unvarnished condition of Aristotle’s surviving treatises does not hamper our ability to come to grips with their philosophical content. His thirty-one surviving works (that is, those contained in the “Corpus Aristotelicum” of our medieval manuscripts that are judged to be authentic) all contain recognizably Aristotelian doctrine; and most of these contain theses whose basic purport is clear, even where matters of detail and nuance are subject to exegetical controversy.

These works may be categorized in terms of the intuitive organizational principles preferred by Aristotle. He refers to the branches of learning as “sciences” ( epistêmai ), best regarded as organized bodies of learning completed for presentation rather than as ongoing records of empirical researches. Moreover, again in his terminology, natural sciences such as physics are but one branch of theoretical science , which comprises both empirical and non-empirical pursuits. He distinguishes theoretical science from more practically oriented studies, some of which concern human conduct and others of which focus on the productive crafts. Thus, the Aristotelian sciences divide into three: (i) theoretical, (ii) practical, and (iii) productive. The principles of division are straightforward: theoretical science seeks knowledge for its own sake; practical science concerns conduct and goodness in action, both individual and societal; and productive science aims at the creation of beautiful or useful objects ( Top . 145a15–16; Phys . 192b8–12; DC 298a27–32, DA 403a27–b2; Met. 1025b25, 1026a18–19, 1064a16–19, b1–3; EN 1139a26–28, 1141b29–32).

(i) The theoretical sciences include prominently what Aristotle calls first philosophy , or metaphysics as we now call it, but also mathematics , and physics , or natural philosophy. Physics studies the natural universe as a whole, and tends in Aristotle’s hands to concentrate on conceptual puzzles pertaining to nature rather than on empirical research; but it reaches further, so that it includes also a theory of causal explanation and finally even a proof of an unmoved mover thought to be the first and final cause of all motion. Many of the puzzles of primary concern to Aristotle have proven perennially attractive to philosophers, mathematicians, and theoretically inclined natural scientists. They include, as a small sample, Zeno’s paradoxes of motion, puzzles about time, the nature of place, and difficulties encountered in thought about the infinite.

Natural philosophy also incorporates the special sciences, including biology, botany, and astronomical theory. Most contemporary critics think that Aristotle treats psychology as a sub-branch of natural philosophy, because he regards the soul ( psuchê ) as the basic principle of life, including all animal and plant life. In fact, however, the evidence for this conclusion is inconclusive at best. It is instructive to note that earlier periods of Aristotelian scholarship thought this controversial, so that, for instance, even something as innocuous-sounding as the question of the proper home of psychology in Aristotle’s division of the sciences ignited a multi-decade debate in the Renaissance. [ 5 ]

(ii) Practical sciences are less contentious, at least as regards their range. These deal with conduct and action, both individual and societal. Practical science thus contrasts with theoretical science, which seeks knowledge for its own sake, and, less obviously, with the productive sciences, which deal with the creation of products external to sciences themselves. Both politics and ethics fall under this branch.

(iii) Finally, then, the productive sciences are mainly crafts aimed at the production of artefacts, or of human productions more broadly construed. The productive sciences include, among others, ship-building, agriculture, and medicine, but also the arts of music, theatre, and dance. Another form of productive science is rhetoric, which treats the principles of speech-making appropriate to various forensic and persuasive settings, including centrally political assemblies.

Significantly, Aristotle’s tri-fold division of the sciences makes no mention of logic. Although he did not use the word ‘logic’ in our sense of the term, Aristotle in fact developed the first formalized system of logic and valid inference. In Aristotle’s framework—although he is nowhere explicit about this—logic belongs to no one science, but rather formulates the principles of correct argumentation suitable to all areas of inquiry in common. It systematizes the principles licensing acceptable inference, and helps to highlight at an abstract level seductive patterns of incorrect inference to be avoided by anyone with a primary interest in truth. So, alongside his more technical work in logic and logical theory, Aristotle investigates informal styles of argumentation and seeks to expose common patterns of fallacious reasoning.

Aristotle’s investigations into logic and the forms of argumentation make up part of the group of works coming down to us from the Middle Ages under the heading the Organon ( organon = tool in Greek). Although not so characterized in these terms by Aristotle, the name is apt, so long as it is borne in mind that intellectual inquiry requires a broad range of tools. Thus, in addition to logic and argumentation (treated primarily in the Prior Analytics and Topics ), the works included in the Organon deal with category theory, the doctrine of propositions and terms, the structure of scientific theory, and to some extent the basic principles of epistemology.

When we slot Aristotle’s most important surviving authentic works into this scheme, we end up with the following basic divisions of his major writings:

- Categories ( Cat .)

- De Interpretatione ( DI ) [ On Interpretation ]

- Prior Analytics ( APr )

- Posterior Analytics ( APo )

- Topics ( Top .)

- Sophistical Refutations ( SE )

- Physics ( Phys .)

- Generation and Corruption ( Gen. et Corr .)

- De Caelo ( DC ) [ On the Heavens ]

- Metaphysics ( Met .)

- De Anima ( DA ) [ On the Soul ]

- Parva Naturalia ( PN ) [ Brief Natural Treatises ]

- History of Animals ( HA )

- Parts of Animals ( PA )

- Movement of Animals ( MA )

- Meteorology ( Meteor .)

- Progression of Animals ( IA )

- Generation of Animals ( GA )

- Nicomachean Ethics ( EN )

- Eudemian Ethics ( EE )

- Magna Moralia ( MM ) [ Great Ethics ]

- Politics ( Pol .)

- Rhetoric ( Rhet .)

- Poetics ( Poet .)

The titles in this list are those in most common use today in English-language scholarship, followed by standard abbreviations in parentheses. For no discernible reason, Latin titles are customarily employed in some cases, English in others. Where Latin titles are in general use, English equivalents are given in square brackets.

Aristotle’s basic approach to philosophy is best grasped initially by way of contrast. Whereas Descartes seeks to place philosophy and science on firm foundations by subjecting all knowledge claims to a searing methodological doubt, Aristotle begins with the conviction that our perceptual and cognitive faculties are basically dependable, that they for the most part put us into direct contact with the features and divisions of our world, and that we need not dally with sceptical postures before engaging in substantive philosophy. Accordingly, he proceeds in all areas of inquiry in the manner of a modern-day natural scientist, who takes it for granted that progress follows the assiduous application of a well-trained mind and so, when presented with a problem, simply goes to work. When he goes to work, Aristotle begins by considering how the world appears, reflecting on the puzzles those appearances throw up, and reviewing what has been said about those puzzles to date. These methods comprise his twin appeals to phainomena and the endoxic method.

These two methods reflect in different ways Aristotle’s deepest motivations for doing philosophy in the first place. “Human beings began to do philosophy,” he says, “even as they do now, because of wonder, at first because they wondered about the strange things right in front of them, and then later, advancing little by little, because they came to find greater things puzzling” ( Met. 982b12). Human beings philosophize, according to Aristotle, because they find aspects of their experience puzzling. The sorts of puzzles we encounter in thinking about the universe and our place within it— aporiai , in Aristotle’s terminology—tax our understanding and induce us to philosophize.

According to Aristotle, it behooves us to begin philosophizing by laying out the phainomena , the appearances , or, more fully, things appearing to be the case , and then also collecting the endoxa , the credible opinions handed down regarding matters we find puzzling. As a typical example, in a passage of his Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle confronts a puzzle of human conduct, the fact that we are apparently sometimes akratic or weak-willed. When introducing this puzzle, Aristotle pauses to reflect upon a precept governing his approach to many areas of inquiry:

As in other cases, we must set out the appearances ( phainomena ) and run through all the puzzles regarding them. In this way we must prove the credible opinions ( endoxa ) about these sorts of experiences—ideally, all the credible opinions, but if not all, then most of them, those which are the most important. For if the objections are answered and the credible opinions remain, we shall have an adequate proof. ( EN 1145b2–7)

Scholars dispute concerning the degree to which Aristotle regards himself as beholden to the credible opinions ( endoxa ) he recounts and the basic appearances ( phainomena ) to which he appeals. [ 6 ] Of course, since the endoxa will sometimes conflict with one another, often precisely because the phainomena generate aporiai , or puzzles, it is not always possible to respect them in their entirety. So, as a group they must be re-interpreted and systematized, and, where that does not suffice, some must be rejected outright. It is in any case abundantly clear that Aristotle is willing to abandon some or all of the endoxa and phainomena whenever science or philosophy demands that he do so ( Met. 1073b36, 1074b6; PA 644b5; EN 1145b2–30).

Still, his attitude towards phainomena does betray a preference to conserve as many appearances as is practicable in a given domain—not because the appearances are unassailably accurate, but rather because, as he supposes, appearances tend to track the truth. We are outfitted with sense organs and powers of mind so structured as to put us into contact with the world and thus to provide us with data regarding its basic constituents and divisions. While our faculties are not infallible, neither are they systematically deceptive or misdirecting. Since philosophy’s aim is truth and much of what appears to us proves upon analysis to be correct, phainomena provide both an impetus to philosophize and a check on some of its more extravagant impulses.

Of course, it is not always clear what constitutes a phainomenon ; still less is it clear which phainomenon is to be respected in the face of bona fide disagreement. This is in part why Aristotle endorses his second and related methodological precept, that we ought to begin philosophical discussions by collecting the most stable and entrenched opinions regarding the topic of inquiry handed down to us by our predecessors. Aristotle’s term for these privileged views, endoxa , is variously rendered as ‘reputable opinions’, ‘credible opinions’, ‘entrenched beliefs’, ‘credible beliefs’, or ‘common beliefs’. Each of these translations captures at least part of what Aristotle intends with this word, but it is important to appreciate that it is a fairly technical term for him. An endoxon is the sort of opinion we spontaneously regard as reputable or worthy of respect, even if upon reflection we may come to question its veracity. (Aristotle appropriates this term from ordinary Greek, in which an endoxos is a notable or honourable man, a man of high repute whom we would spontaneously respect—though we might, of course, upon closer inspection, find cause to criticize him.) As he explains his use of the term, endoxa are widely shared opinions, often ultimately issuing from those we esteem most: ‘ Endoxa are those opinions accepted by everyone, or by the majority, or by the wise—and among the wise, by all or most of them, or by those who are the most notable and having the highest reputation’ ( Top. 100b21–23). Endoxa play a special role in Aristotelian philosophy in part because they form a significant sub-class of phainomena ( EN 1154b3–8): because they are the privileged opinions we find ourselves unreflectively endorsing and reaffirming after some reflection, they themselves come to qualify as appearances to be preserved where possible.