- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

Rethinking Performance Management for Post-Pandemic Success

Organizations serious about high performance must rethink performance metrics.

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Leadership Skills

- Talent Management

- Analytics & Business Intelligence

Performance Management

Will dispersed, distributed, and remote workforces become the post-pandemic new normal? It may be too soon to say. Much clearer is how misleading and unhelpful legacy metrics are for assessing work-from-home performance. Pre-COVID-19 workplace analytics are no longer fit for purpose. They don’t capture the disjointed realities of digital workflows. Stressed, separated, and challenged to do better with less, people need greater insight into how they’re doing. Productivity now demands more aggressive and actionable measures.

Recalibrating key performance indicators (KPIs) is essential to ensuring that remote work actually works. Enterprises that want the best from their workers — and for their customers — innovatively invest in digital accountability, but these efforts must acknowledge and respect newly blurred distinctions between work and home life. Digitally colonizing people’s homes is not an option; workforce mood and morale matter. Thoughtful leaders grasp the need for a healthy coexistence.

Email Updates on the Future of Work

Monthly research-based updates on what the future of work means for your workplace, teams, and culture.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

Without trust and transparency, remote workforce monitoring appears intrusive and exploitative. With transparency and trust, tracking can authentically be branded and experienced as data-driven workforce support . Increasingly, monitoring and measuring morale — qualitatively, as well as quantitatively — matters. But soft skills deserve hard numbers, too. Emergent post-pandemic dashboards embrace affective metrics as firmly and fairly as effective ones.

That means that leading companies must renovate their data-driven dashboards to better inspire people and project teams and promote positive outcomes. They must automatically capture and analyze, and explicitly communicate, their high-performance criteria. The most important takeaway: High-performance management depends on high-performance measurement. The digital future of one depends on the digital future of the other.

Redefining and remeasuring high performance may prove to be the true disruptive opportunity for post-COVID-19 growth.

At one global professional services company, for example, top management dramatically accelerated project delivery schedules for its newly remote teams. This forcing mechanism deliberately inspired greater communication, coordination, and collaboration expectations for team members. At the same time, however, the company created a complementary buddy system to help ensure that more isolated and/or introverted employees felt connected. Tech support migrated from a back-office help-desk function to a digital project facilitator and enabler for global teams with demanding deadlines. The number of pulse surveys monitoring employee engagement and morale increased from fortnightly to every few days. Top management is tracking what‚ and who — delivers value well.

A senior global research project manager at Adobe programmed his laptop to display a personalized end-of-day dashboard visually summarizing — with pie charts and graphs — how he spent his time, whom he contacted, messages sent and received, documents exchanged, appointments scheduled, commitments made, and to-do list items accomplished, along with the top three items for the following day. He started sharing this dashboard with his team and is now wondering whether he should nudge — or require — colleagues to create comparable dashboards. “Should we be visible to each other in this way?” he asks. He says that such “dashboard transparency” has sparked cross-functional exchanges he’d never had before.

At least two global banks seek to capture remote-working lessons and best practices for internal discussion and sharing. Looking ahead, they’re rethinking whether they really need all the commercial office space they currently possess. They’re now reviewing with IT how significantly having a dispersed workforce alters their process automation road maps. Consequently, IT and its business process owner counterparts now track and map dispersed workforce workflows with a new remote automation strategy in mind.

Using Data to Better (See and Communicate) Performance

Mandatory remoteness quickly obsolesced executive truisms like “management by walking around,” and “under management’s watchful eye,” along with the concept of an “open-door policy.” Disrupted organizations soon learn just how little they know about how well — and how poorly — their people and teams work together. Virtually every serious organization now grasps that some meaningfully measurable form of real-time monitoring is essential to value orchestration and oversight.

For some, this quest for transparency translates to “Trust but verify”; for others, the mantra is “Verify but trust.” Either way, trust is core. “Do I trust my people? Yes,” says one investment banking lead. “Do I now need to be able to see how they spend their time? Yes. They need to trust me, too.”

Proactive enterprise communication is central to this cultural shift. When a Fortune /Adobe survey asked CIOs what has proved to be the biggest challenge in facilitating their companies’ remote work, only 20% said hardware, and 21% tech tools. Over half — 53% — said the hardest issue was getting employees to effectively communicate with one another. Why is that so seemingly hard? There’s certainly no shortage of smart messaging tools. As the COVID-19 crisis reveals, companies overwhelmingly depend on them.

Yet, most companies lack real-time metrics or measures assessing team and/or process communication effectiveness. Typically, those indicators are bundled into performance management reviews. That helps explain an accelerating managerial trend: greater reliance on performance management systems to better orchestrate and upgrade team performance. This emergent application of performance management systems ensures more communication and conversations about performance.

Unsurprisingly, next-generation performance management depends on digital monitoring and tracking platforms to generate real-time analytic insights. Those workflow and process insights can be prescriptive and predictive, as well as descriptive. High-performing leaders embrace this practice. Dispersed, technologically enabled enterprises seamlessly converge people, process, and technology into performance management systems.

With improved dashboards, leaders can see which teams best add value to what processes. They can observe which workflows invite consolidation, automation, and/or professional development . Leadership now has the data and analytics necessary to refine what high performance should mean for people and what it could mean for machines. These insights are indispensable. The more repeatable, replicable, and scalable the high-performance workflow, the better its candidacy for automation and/or machine learning. Correlating and connecting instrumented workflows with KPIs lets organizations turn the “remoteness from COVID-19”-imposed bug into a high-performance-enabling feature.

We see this in law firms, logistics providers, customer contact centers, and even health care providers. From telemedicine to texts about a customer’s arrival for curbside pickup, organizations are repurposing and instrumenting their performance management platforms in ways that measurably redefine high performance.

For example, colocated contact centers have been forced to geographically disperse. This has brutally disrupted legacy work patterns and forced a performance management reevaluation. Chatbots prioritize and route inquiries; support workers more easily message or transfer callers to colleagues; automated follow-ups with relevant links attached are readily sent. Response time, Net Promoter Score, and customer satisfaction KPIs retain pride of metrics place. But better analytics orchestration lets management track the digital blends of process and performance ingredients best correlated to desired outcomes. The resultant data highlights touch points best suited for automation and those where human contact best improves outcomes. The new constraints and opportunities imposed by remoteness and automation have transformed how the contact centers have chosen to align performance assessment, efficiency, and customer response.

Similarly, a “remote-ified” Silicon Valley law firm quickly and effectively deployed transcription-as-a-service to convert every Zoom-based client and partner meeting into editable documents. Instant transcripts dramatically changed how legal teams collaborated with each other and with clients. Measuring value-added revisions to those documents — and how those revisions were included in filings and client communications — immediately emerged as an essential workflow monitoring challenge. Version management governance became a new driver for decision-making. Partners now track their time-and-version ratios between simultaneous and asynchronous review. For some partners and associates, ROI effectively means return on iteration — in other words, which lawyers and legal teams have the biggest productive impact editing, annotating, and converting transcripts into desired client deliverables.

These examples show that successful leaders can use performance management analytics as portal and platform to convert new capabilities and constraints into new value. Data-informed performance management invites and inspires more productive workforce exchanges.

These interim COVID-19 findings represent genuine business applications of conclusions reached by our 2019 research report “ Performance Management’s Digital Shift .” That report anticipated the disruptive dominance data-driven workforce communication would enjoy. “The biggest cultural and organizational impact of next-generation performance management systems,” we observed, “will be feedback time, tempo, and impact. Instead of annual, quarterly, or impromptu reviews, talent- and accountability-oriented enterprises will encourage and enable near-constant feedback.”

Feedback — actionable, constructive, trackable, and influential — is the informational and motivational coin of the digital realm in the post-pandemic distributed workforce. Feedback — data-enriched, KPI-aligned — simultaneously promotes situational awareness and self-awareness. Feedback is how people get better at getting better. High-performance systems require high-performance feedback. Better-quality feedback means better-quality outcomes. This simple management — and leadership — truth is being rediscovered and reconfigured in light of COVID-19.

To cultivate healthy returns from a healthy — if remote and distributed — workforce requires leaders to treat data and analytics as nutrients for people, not just fuel for economic growth. That means leaders need to do the following:

Commit to a continuous feedback culture. Much as individuals use Google Maps or Waze to manage expectations around travel, employees and associates need dynamic visualizations to manage their expectations around work. Performance management platforms must facilitate ongoing feedback on professional progress, growth, and development opportunities. Executives must define the feedback experience for their people. Doing so forces leaders to define and develop a shared perspective about what high performance means.

Commit to clarity between assessment and development. Managers should make clear when feedback targets performance assessment versus cultivating new capabilities and skills. Development matters. Especially for remote workers and distributed teams, human resource policies must balance assessment and the safe cultivation of new skills and capabilities.

Commit to transparency. Post-pandemic performance management credibility and trustworthiness depend on transparency. People must be able to see that their contributions to meetings are recognized and/or that their blown deadlines cost the company a big client. This requires significant shifts in data governance: Connecting and aligning feedback transparency to data collection must become a core cultural value and practice. In short, transparency is the foundation for a performance culture that can also literally be seen as a fair and equitable culture.

Related Articles

Commit to performance management and KPI alignment. Aspiration and expectation require quantification. There is no meaningful performance management without measurable KPIs. High-performance accountability requires clear and concise KPIs or key results. Linking performance management to KPIs or objectives and key results is the strategic duty and obligation of serious leadership. Managers, not HR, ensure that performance management activities support measurable, valuable business outcomes.

There will always be tensions — and opportunities — between managing high-performance people, high-performance machines, and high-performance systems. Innovatively confronting those challenges will be the most important leadership challenge this global pandemic creates.

About the Author

Michael Schrage is a research fellow at the MIT Sloan School of Management’s Initiative on the Digital Economy, where he does research and advisory work on how digital media transforms agency, human capital, and innovation.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Performance →

- 02 Jan 2024

- What Do You Think?

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Nov 2023

- Research & Ideas

Humans vs. Machines: Untangling the Tasks AI Can (and Can't) Handle

Are you a centaur or a cyborg? A study of 750 consultants sheds new light on the strengths and limits of ChatGPT, and what it takes to operationalize generative AI. Research by Edward McFowland III, Karim Lakhani, Fabrizio Dell'Acqua, and colleagues.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 28 Aug 2023

The Clock Is Ticking: 3 Ways to Manage Your Time Better

Life is short. Are you using your time wisely? Leslie Perlow, Arthur Brooks, and DJ DiDonna offer time management advice to help you work smarter and live happier.

- 08 Aug 2023

The Rise of Employee Analytics: Productivity Dream or Micromanagement Nightmare?

"People analytics"—using employee data to make management decisions—could soon transform the workplace and hiring, but implementation will be critical, says Jeffrey Polzer. After all, do managers really need to know about employees' every keystroke?

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 05 Jun 2023

Is the Anxious Achiever a Post-Pandemic Relic?

Achievement has been a salve for self-doubt for many generations. But many of the oldest members of Gen Z, who came of age amid COVID-19, think differently about the value of work. Will they forge a new leadership style? wonders James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 27 Feb 2023

How One Late Employee Can Hurt Your Business: Data from 25 Million Timecards

Employees who clock in a few minutes late—or not at all—often dampen sales and productivity, says a study of 100,000 workers by Ananth Raman and Caleb Kwon. What can managers do to address chronic tardiness and absenteeism?

- 01 Feb 2023

Will Hybrid Work Strategies Pull Down Long-Term Performance?

Many academics consider remote and hybrid work the future, but some business leaders are pushing back. Can colleagues working from anywhere still create the special glue that bonds teams together? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Aug 2022

- Cold Call Podcast

Management Lessons from the Sinking of the SS El Faro

Captain Michael Davidson of the container ship SS El Faro was determined to make his planned shipping trip on time—but a hurricane was approaching his intended path. To succeed, Davidson and his fellow officers had to plot a course to avoid the storm in the face of conflicting weather reports from multiple sources and differing opinions among the officers about what to do. Over the 36-hour voyage, tensions rose as the ship got closer and closer to the storm. And there were other factors compounding the challenge. The El Faro was an old ship, about to be scrapped. Its owner, TOTE Maritime, was in the process of selecting officers to crew its new ships. Davidson and some of his officers knew the company measured a ship’s on-time arrival and factored that into performance reviews and hiring decisions. When the ship ultimately sunk on October 1, 2015, it was the deadliest American shipping disaster in decades. But who was to blame for the tragedy and what can we learn from it? Professor Joe Fuller discusses the culpability of the captain, as well as his subordinates, and what it reveals about how leaders and their teams communicate under pressure in his case, "Into the Raging Sea: Final Voyage of the SS El Faro."

- 01 Aug 2022

Does Religious Belief Affect Organizational Performance?

Chinese firms exposed to Confucianism outperformed peers and contributed more to their communities, says a recent study. James Heskett considers whether the role of religion in management merits further research. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Mar 2022

How Etsy Found Its Purpose and Crafted a Turnaround

Etsy, the online seller of handmade goods, was founded in 2005 as an alternative to companies that sold mass-manufactured products. The company grew substantially, but remained unprofitable under the leadership of two early CEOs. Ten years later, Etsy went public and was forced into a new arena, where it was beholden to stakeholders who demanded financial success and accountability. Unable to contain costs, the company was almost bought out by private equity firms in 2017—until CEO Josh Silverman arrived with a mission to save the company financially and, in the process, save its soul. Harvard Business School professor Ranjay Gulati discusses the purpose-driven turnaround Silverman and his team led at Etsy—to make the company profitable and improve its social and environmental impact—in the case, “Etsy: Crafting a Turnaround to Save the Business and Its Soul.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 Nov 2021

The Simple Secret of Effective Mentoring Programs

The employees who need guidance most rarely seek it out. New research by Christopher Stanton sheds light on what companies stand to gain from mentorship programs that include everyone. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Oct 2021

Want Hybrid Work to Succeed? Trust, Don’t Track, Employees

Many companies want employees back at desks, but workers want more flexibility than ever. Tsedal Neeley offers three rules for senior managers trying to forge a new hybrid path. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 13 Jul 2021

Strategies for Underdogs: How Alibaba’s Taobao Beat eBay in China

In 2007, Alibaba’s Taobao became China’s leading consumer e-commerce marketplace, displacing the once dominant eBay. How did underdog Taobao do it? And will it be able to find a way to monetize its marketplace and ensure future success? Professor Felix Oberholzer-Gee discusses his case, “Alibaba’s Taobao,” and related strategy lessons from his new book, Better, Simpler Strategy: A Value-Based Guide to Exceptional Performance. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Oct 2020

- Sharpening Your Skills

Steps to Help You Get Out of Your Own Way

These research-based tips will help you slow down, fight the fog, and improve both your home life and work life. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 08 Oct 2020

Keep Your Weary Workers Engaged and Motivated

Humans are motivated by four drives: acquire, bond, comprehend, and defend. Boris Groysberg and Robin Abrahams discuss how managers can use all four to keep employees engaged. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 29 Sep 2020

Employee Performance vs. Company Values: A Manager’s Dilemma

The Cold Call podcast celebrate its five-year anniversary with a classic case study. Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria discusses the dilemma of how to treat a brilliant individual performer who can't work with colleagues. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 07 Sep 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Entrepreneurs (Co-) Working in Close Proximity: Impacts on Technology Adoption and Startup Performance Outcomes

In one of the largest entrepreneurial co-working spaces in the United States, startups are influenced by peer startups within a distance of 20 meters. The associated advantages for learning and innovation could be lost using at-a-distance work arrangements.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Performance Management Revolution

- Peter Cappelli

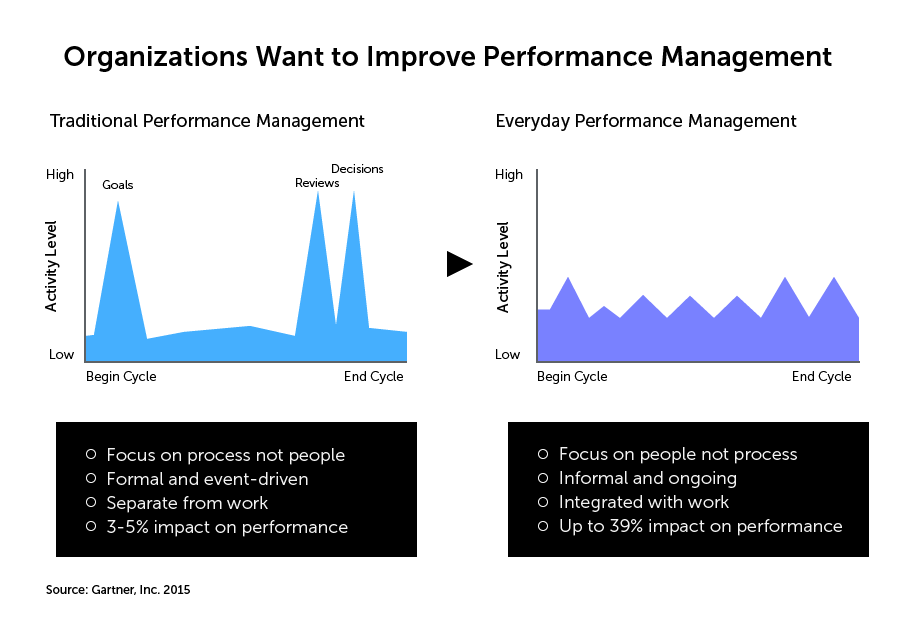

Hated by bosses and subordinates alike, traditional performance appraisals have been abandoned by more than a third of U.S. companies. The annual review’s biggest limitation, the authors argue, is its emphasis on holding employees accountable for what they did last year, at the expense of improving performance now and in the future. That’s why many organizations are moving to more-frequent, development-focused conversations between managers and employees.

The authors explain how performance management has evolved over the decades and why current thinking has shifted: (1) Today’s tight labor market creates pressure to keep employees happy and groom them for advancement. (2) The rapidly changing business environment requires agility, which argues for regular check-ins with employees. (3) Prioritizing improvement over accountability promotes teamwork.

Some companies worry that going numberless may make it harder to align individual and organizational goals, award merit raises, identify poor performers, and counter claims of discrimination—though traditional appraisals haven’t solved those problems, either. Other firms are trying hybrid approaches—for example, giving employees performance ratings on multiple dimensions, coupled with regular development feedback.

The focus is shifting from accountability to learning.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

By emphasizing individual accountability for past results, traditional appraisals give short shrift to improving current performance and developing talent for the future. That can hinder long-term competitiveness.

The Solution

To better support employee development, many organizations are dropping or radically changing their annual review systems in favor of giving people less formal, more frequent feedback that follows the natural cycle of work.

The Outlook

This shift isn’t just a fad—real business needs are driving it. Support at the top is critical, though. Some firms that have struggled to go entirely without ratings are trying a “third way”: assigning multiple ratings several times a year to encourage employees’ growth.

When Brian Jensen told his audience of HR executives that Colorcon wasn’t bothering with annual reviews anymore, they were appalled. This was in 2002, during his tenure as the drugmaker’s head of global human resources. In his presentation at the Wharton School, Jensen explained that Colorcon had found a more effective way of reinforcing desired behaviors and managing performance: Supervisors were giving people instant feedback, tying it to individuals’ own goals, and handing out small weekly bonuses to employees they saw doing good things.

- Peter Cappelli is the George W. Taylor Professor of Management at the Wharton School and the director of its Center for Human Resources. He is the author of several books, including Our Least Important Asset: Why the Relentless Focus on Finance and Accounting Is Bad for Business and Employees (Oxford University Press).

- AT Anna Tavis is a clinical associate professor of human capital management at New York University and the Perspectives editor at People + Strategy, a journal for HR executives.

Partner Center

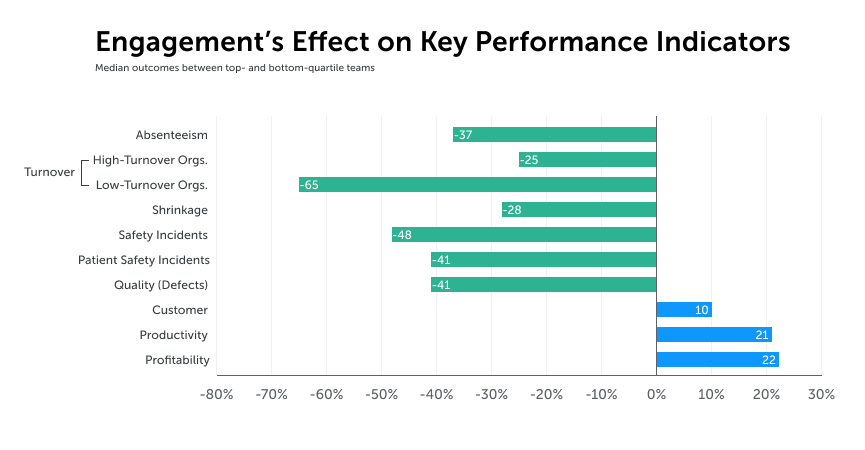

Harnessing the power of performance management

These days, performance management is a source of dissatisfaction at many organizations. Large shares of respondents to a recent McKinsey Global Survey on the topic say their organizations’ current systems and practices have no effect—or even a negative one—on company performance. 1 1. The online survey was in the field from July 18 to July 28, 2017, and garnered responses from 1,761 participants representing the full ranges of regions, industries, company sizes, functional specialties, and tenures. To adjust for differences in response rates, the data are weighted by the contribution of each respondent’s nation to global GDP. Moreover, they do not see positive returns on investment for the time spent on performance management. Yet the results also show that when executed well, performance management has a positive impact on employees’ performance and the organization’s performance overall.

Stay current on your favorite topics

Our analysis indicates that the key to reaping positive business outcomes from performance management is to establish a system that employees and managers perceive as fair. 2 2. As McKinsey’s Scott Keller and Mary Meaney write in Leading Organizations: Ten Timeless Truths , “We believe people aren’t against being evaluated, and, in fact, they want to know where they stand. They just want the process to be fair. They want a process that differentiates without false precision, that is both forward- and backward-looking, that happens far more frequently than once a year (but not so much as to create feedback fatigue), that involves an honest, two-way conversation, that is based on more data and input than just the boss’s view, that considers not just what was achieved, but also how, and links rewards and consequences to performance.” For more, see Scott Keller and Mary Meaney, Leading Organizations: Ten Timeless Truths , first edition, London: Bloomsbury Business, 2017. To ensure that perception, managers should master three critical practices: linking individuals’ goals with business priorities, coaching effectively , and differentiating compensation across levels of performance.

Disappointed and seeking to improve quickly

On the whole, respondents express doubt that their current performance-management systems foster strong performance. In fact, more than half of respondents believe performance management has not had a positive effect on employee or organizational performance (Exhibit 1).

Accordingly, many respondents say their companies are making changes. Two-thirds report the implementation of at least one meaningful modification to their performance-management systems in the past 18 months. These results also show that companies are making a wide variety of adjustments. No more than one-third of respondents report implementing even one of the three most commonly cited changes—simplifying ratings, streamlining formal review processes, and separating conversations about performance and compensation (Exhibit 2).

Despite the lack of consensus on where to focus improvements, the responses clearly indicate that performance management, when done well, boosts overall performance. Respondents who say their companies’ performance-management systems have a positive impact on both employee and business performance are much likelier than others to report better business outcomes. 3 3. We measured business outcomes based on respondents’ reporting of how their organization performed in the past three years, relative to peers. The outperforming companies are those that, according to respondents, have performed much better or somewhat better than their competitors. Among respondents who consider their companies’ performance-management systems effective, 60 percent say their companies have outperformed their peers in the past three years—nearly three times the share of respondents who rate their companies’ performance management as ineffective.

Three practices for successful performance management

From the results, we have identified three practices that correlate most closely with the key factor of performance management’s effectiveness: the perceived fairness of the system . These practices are linking performance goals to business priorities , effective coaching by managers, and differentiating compensation across levels of performance (Exhibit 3).

What’s more, these practices are mutually reinforcing: implementing one practice well can have a positive effect on the performance of others and leads to more effective performance management overall. In fact, among respondents who say their organizations perform well on all three practices, 84 percent report a positive impact on performance management (Exhibit 4). They are 12 times likelier to report effective performance-management systems than respondents who say their companies have not implemented any of the three.

Linking performance goals to business priorities. The first practice of the three, linking individual employees’ performance goals to business priorities, not only correlates with a higher level of perceived fairness but also helps companies achieve their strategic goals. Where employees’ goals are linked to business priorities, 46 percent of respondents report effective performance management, compared with 16 percent at companies that don’t follow this practice.

The results suggest that performance goals, besides being linked to strategy, should be adaptable and revisited as market conditions change or extenuating circumstances occur. The regular review of goals helps ensure that individuals in the organization continue to believe that the system is fair and also has a positive impact on performance management. Of respondents who report effective performance management, 62 percent say their companies revisit goals at least twice a year or on an ad hoc basis.

Manager coaching. Our analysis indicates not only that effective coaching is the strongest driver of perceived fairness but also that there is a direct relationship between effective managers and the effectiveness of a company’s performance-management system. When managers effectively coach and develop their employees—a practice that less than 30 percent of all respondents report—74 percent say their performance-management systems are effective, and 62 percent say their organizations’ performance is better than that of competitors. Where respondents do not see managers as effective coaches, only 15 percent report effective performance management, and just 30 percent report outperformance relative to competitors.

On specific coaching methods, the results suggest that ongoing development conversations between managers and employees also support better outcomes. In fact, 68 percent of respondents agree that ongoing coaching and feedback conversations have a positive impact on individual performance. Respondents who say that ongoing discussions take place are ten times likelier than others to rate performance-management systems at their companies as effective, and they are nearly twice as likely to say their companies have outperformed competitors. So if organizations do nothing else to improve performance management, they should invest in managers’ capabilities and communicate their expectations for having high-quality coaching and development conversations with employees.

Other results suggest that respondents, on the whole, understand the value of strong manager capabilities . When asked about changes their companies have made to existing performance-management systems in the past 18 months, the change that links most closely to improved employee performance is resetting manager expectations around coaching and development . And among the actions that respondents say their organizations will take in the next 18 months, the most common is more frequent coaching conversations.

Differentiating compensation. The third practice is meaningful differentiation of compensation among low, midlevel, and high performers. Less than half of all respondents agree that at their organizations, employee pay is meaningfully different across levels of performance—and the results confirm that this practice links closely with outperformance. Of the respondents reporting differentiated compensation at their companies, 54 percent rate their performance-management systems as effective, compared with only 16 percent at companies without meaningfully different compensation. Among those following the practice, 52 percent say their organizations have performed better than their peers in recent years.

Also on compensation, the results suggest that effective performance management is more likely when organizations separate compensation conversations from formal evaluations. Of the respondents who say their companies separate discussions about performance from discussions about compensation, 47 percent report effective performance management—compared with 30 percent at companies that don’t separate such discussions.

Would you like to learn more about OrgSolutions ?

While multiple factors contribute to a perceived sense of fairness, the previous three practices have the most impact on whether respondents say their companies’ performance-management systems are considered to be fair. And of all the organizational practices the survey asked about, perceived fairness correlates most closely with positive business outcomes. Among respondents who agree that their performance-management systems are perceived as fair, 60 percent report an overall effective system. 4 4. Thirty-eight percent of respondents rate their performance-management systems as effective (that is, they say that performance management has had a positive impact both on individual employees’ performance and on their organizations’ performance). Of their peers who do not agree, only 7 percent report an overall effective system. What’s more, the respondents reporting perceived fairness are nearly twice as likely as those who don’t (52 percent, compared with 27 percent) to say their companies are outperforming competitors.

Beyond these key points, the responses also indicate a few secondary—but important—practices that can encourage effective performance management. One is the use of technology to revamp performance-management systems. Respondents say their organizations are using technology for a wide variety of performance-management interventions, from tracking progress against performance goals to monitoring completion of development conversations. Yet other than the completion of forms for formal performance reviews, none of the other applications is used moderately or greatly by a majority of respondents. The value of technology seems to be clear, though, for the companies that have already implemented it. At companies that have launched mobile technologies to support performance management in the past 18 months, 65 percent of respondents say this change has had a positive effect on both employee and company performance. But while technology can certainly enable effective performance management, the most important measures to get right are the three best practices that foster a sense of fairness across the organization.

The contributors to the development and analysis of this survey include Sabrin Chowdhury, a consultant in McKinsey’s New Jersey office , Bill Schaninger , a senior partner in the Philadelphia office , and Elizabeth Hioe, an alumna of the New Jersey office.

They wish to thank Lili Duan and David Mendelsohn for their contributions to this work.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

The fairness factor in performance management

Performance management: Why keeping score is so important, and so hard

The CEO’s guide to competing through HR

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Behav Sci

- v.42(4); 2019 Dec

Evidence-Based Performance Management: Applying Behavioral Science to Support Practitioners

Matthew d. novak.

4001 Dole Human Development Center, Department of Applied Behavioral Science, University of Kansas, 1000 Sunnyside Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66045 USA

Florence D. DiGennaro Reed

Tyler g. erath, abigail l. blackman, sandra a. ruby, azure j. pellegrino.

The science of behavior has effectively addressed many areas of social importance, including the performance management of staff working in human-service settings. Evidence-based performance management entails initial preservice training and ongoing staff support. Initial training reflects a critical first training component and is necessary for staff to work independently within an organization. However, investment in staff must not end once preservice training is complete. Ongoing staff support should follow preservice training and involves continued coaching and feedback. The purpose of this article is to bridge the research-to-practice gap by outlining research-supported initial training and ongoing staff support procedures within human-serving settings, presenting practice guidelines, and sharing information about easy-to-implement ways practitioners may stay abreast of current research.

Train people well enough so they can leave, treat them well enough so they don’t want to. —Richard Branson

The science of behavior has effectively addressed many areas of social importance including education (e.g., Sulzer-Azaroff & Gillat, 1990 ), traffic safety (e.g., van Houten, Nau, & Marini, 1980 ; Yeaton & Bailey, 1978 ), substance use (e.g., Higgins, Silverman, & Heil, 2007 ), parent training (e.g., Lindgren et al., 2016 ; Phaneuf & McIntyre, 2007 ), behavioral medicine (e.g., Piazza, Milnes, & Shalev, 2015 ), and others. Perhaps the most widely known application is the behavioral treatment of autism (Freedman, 2016 ). Due to the research supporting its effectiveness (e.g., National Autism Center, 2009 , 2015 ), autism treatment based on the principles of behavior analysis is endorsed by the U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1999 ), National Institutes of Health (Strock, 2007 ), and the National Research Council (Lord & McGee, 2001 ). The model that has evolved for the provision of services to individuals with autism and other disabilities presents a challenge that is unique to those in health and human services. Whereas psychological therapy is delivered by licensed psychologists and medical procedures are performed by doctors, behavior analysts with the most amount of training and education (i.e., Board Certified Behavior Analysts®) often do not deliver services directly. Rather, they typically oversee the provision of services delivered by others. Thus, the challenge for those providing behavioral services to vulnerable populations is ensuring that individuals with relatively less training and education (i.e., Registered Behavior Technicians® or Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analysts®) provide direct services in an effective and responsible manner.

To be successful, this unique service model necessitates effective performance management—the careful training and supervision of staff who implement behavioral treatment. Unfortunately, recent research suggests the field could benefit from improvements in this area. DiGennaro Reed and Henley ( 2015 ) administered a survey to certified and aspiring behavior analysts to determine the extent to which evidence-based staff training practices were implemented by their employers. The results were worrisome and launched efforts by the authors to disseminate recommended practices to practitioners and organizational leaders (e.g., DiGennaro Reed, 2016 , 2017 , 2018 , 2019 ; Henley, 2018 , 2019 ). Only 55% of respondents indicated they received initial training after being hired; when training was provided, organizations relied on tactics with little empirical support, such as instruction alone. Fortunately, 71% of respondents reported they received ongoing training and support, but primarily in the forms of a lecture or monthly feedback, which are typically less effective than other forms of performance management. Respondents who worked as supervisors were also queried about the training they received to prepare them for the important responsibility of leading and managing staff. Only 33% indicated they received any formal training on how to effectively implement research-supported supervision practices. These results suggest training and performance management in settings that employ behavior analysts are not consistent with recommended practices. Many respondents began working without any formal training, received less-than-ideal ongoing support, and were expected to supervise staff without any guidance regarding best practices.

Many practicing behavior analysts lack sufficient training and ongoing support, which is worrisome because the lack of evidence-based staff training and performance management may lead to negative outcomes, including staff turnover, poor service quality, and charges of unethical conduct. Kazemi, Shapiro, and Kavner ( 2015 ) surveyed 100 behavior technicians from several companies and found that satisfaction with initial training, ongoing staff support, and supervisor behavior were key factors influencing respondents’ intent to quit their jobs. These results suggest that providing evidence-based staff training may help to mitigate staff turnover, which is reported to be as high as 75% within human-service organizations (Kazemi et al., 2015 ). Moreover, staff turnover places substantial financial strain on an organization, with average costs ranging from $5,000 for a single behavior technician to $10,000 for a certified behavior analyst (Sundberg, 2016 ).

In addition to affecting workforce stability, insufficient training and performance management may further disrupt the quality of behavioral services by influencing treatment integrity—the extent to which prescribed treatment procedures are implemented correctly (Peterson, Homer, & Wonderlich, 1982 ). In a review of 19 parametric analyses of treatment integrity, Brand, Henley, DiGennaro Reed, Gray, and Crabbs ( 2019 ) reported that treatment integrity errors produce unpredictable client outcomes. Although, in some instances, errors in behavioral treatment did not negatively influence client skill acquisition or problem behavior (e.g., Leon, Wilder, Majdalany, Myers, & Saini, 2014 ), in general researchers showed that integrity errors resulted in slower learner progress and less effective treatment. These findings underscore the importance of ensuring that staff implement treatment protocols as designed, which is fostered by the quality of training and performance management staff experience.

Insufficient performance management practices may have consequences that extend beyond affecting direct services; they may carry severe consequences for behavior analysts individually as well as for the profession more broadly. To ensure quality provision of services, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board® (BACB®) Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2014 ) outlines a set of guidelines that all behavior analysts must follow. For example, section 5.03 of the Code states, “If the supervisee does not have the skills necessary to perform competently, ethically, and safely, behavior analysts provide conditions for the acquisition of those skills” (p. 14). Thus, supervisors are obligated to provide staff with effective training. On the topic of ongoing staff support, section 5.06 states, “Behavior analysts design feedback and reinforcement systems in a way that improves supervisee performance. Behavior analysts provide documented, timely feedback regarding the performance of a supervisee on an ongoing basis” (p. 14). Together these statements indicate that behavior analysts must rely on evidence-based staff training and performance management procedures to ensure compliance with this code. Failure to do so may result in ethical charges against the credentialed behavior analyst, which could lead to loss of certification or state licensure.

Evidence-based performance management involves a program that includes initial preservice training and ongoing staff support. Initial training, often referred to as orientation or onboarding , reflects a critical first training component and is necessary for staff to work independently within an organization. However, investment in staff must not end once preservice training is complete. Ongoing staff support should follow preservice training and it involves supervisors providing continued coaching and feedback regarding the staff’s performance in one or more areas. The purpose of this article is to bridge the research-to-practice gap by outlining research-supported initial training and ongoing staff support procedures within human-service settings, presenting practice guidelines based on our experience and current research, and sharing information about ways to stay up to date with research.

Preservice Training

The natural first step to ensuring high-quality staff training is the delivery of preservice training, which allows new employees to learn relevant job skills in a controlled, distraction-free environment. Although orientation and onboarding procedures are ubiquitous across all forms of employment, the presence of training alone does not guarantee proficiency with job skills. To be most effective, preservice training should use empirically supported training techniques. One empirically supported technique is behavioral skills training (BST), which is a procedure used to train new skills through a package including instruction, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback (Parsons, Rollyson, & Reid, 2012 ). Behavioral skills training can be implemented individually or in groups and has been used to train several tasks in the human service industry, including discrete trial instruction (Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004 ) and mand training (Nigro-Bruzzi & Sturmey, 2010 ) among others. Each component of BST is outlined below.

Instruction

The first component of BST is instruction, which involves describing a target skill or behavior one expects the trainee to perform (Miltenberger, 2016 ). Trainers can deliver instruction by describing procedures vocally (e.g., lecture, discussion) or textually (e.g., written protocols). Written protocols can include text alone or text with supplemental components, such as diagrams and images (i.e., enhanced written instructions; Berkman, Roscoe, & Bourret, 2019 ; Graff & Karsten, 2012 ). All too often, preservice training ends after instruction alone (DiGennaro Reed & Henley, 2015 ). It is critical to know that instruction alone is insufficient in training new skills (Ducharme & Feldman, 1992 ). Instead, training should begin with instruction followed by the other components that comprise BST.

This is not to say that instruction does not influence performance. Indeed, there are several ways in which instruction can be delivered to influence trainees’ performance. For example, Henley, Hirst, DiGennaro Reed, Becirevic, and Reed ( 2017 ) compared the use of directive instructions (e.g., “you must”) to nondirective instructions (e.g., “you might consider”) on trainees’ responding under changing reinforcement schedules in a laboratory task. When presented with directive instructions, participants responded in accordance with the instructions, even when the instructions were inaccurate (i.e., instructions did not match the reinforcement schedules). Participants in the nondirective condition, however, responded in accordance with the reinforcement schedules, independent of the instructions. Studies on this topic suggest that, when creating instructions for staff, it is important to consider how instructions are delivered, as minor variations may affect performance.

There are isolated instances in the literature of participants correctly performing skills after detailed instruction alone. For example, Graff and Karsten ( 2012 ) taught staff to effectively conduct preference assessments using enhanced written instructions, which included a detailed data sheet, diagrams, and step-by-step instructions written without technical jargon. However, Shapiro, Kazemi, Pogosjana, Rios, and Mendoza ( 2016 ) only partially replicated Graff and Karsten’s findings and had to include additional training procedures to reach criterion performance. Instances of performing to criterion after instruction alone are rare and may depend on various factors, such as the skill being trained, the instruction format, and the trainee’s history. Because these several factors must align for instruction alone to be effective, it is prudent to implement all components of BST when conducting preservice training.

Practice Guidelines

We recommend that trainers present clear and succinct instructions about procedures, as Jarmolowicz et al. ( 2008 ) demonstrated that treatment adherence is better when instructions are written in a conversational form than in technical language. Moreover, it may be helpful to provide jargon-free, written protocols with diagrams (Graff & Karsten, 2012 ) that staff can use during training and refer to later, if needed. In our consultation experience, we have observed that trainees often appreciate the rationale for certain procedures, and providing that information may help guard against performance drift, though research is still needed in this area. Finally, we recommend trainers and supervisors be transparent about specific behaviors that will be observed and measured. It is presumed that the behaviors that will be observed and measured are of the utmost importance and, thus, should not be kept a secret from trainees. Also, new staff members generally want to perform well and may become nervous about their responsibilities and being observed. In our experience, transparency about what is expected and how performance will be measured generally reduces trainees’ nervousness.

The second component of BST is modeling, which involves an experienced staff person demonstrating perfect performance of a target skill or behavior one expects the trainee to imitate (Miltenberger, 2016 ). Modeling can take place in person or shown via video. Video modeling includes the advantages of conserving resources if used over time and being transportable, allowing trainees the opportunity to view the video model outside of the training session. Further, a live model may contain slight errors or inconsistencies across trainings that affect training outcomes; video modeling provides the added benefit of standardizing training procedures and ensuring that only desired models are shown 1 (DiGennaro Reed, Blackman, Erath, Brand, & Novak, 2018 ; Shapiro & Kazemi, 2017 ).

Recent research has shown video modeling, in particular video modeling with voiceover instruction, to be more effective than written instructions alone—though feedback was required for some participants—when training new staff to implement discrete trial instruction and behavior reduction interventions (e.g., DiGennaro Reed, Codding, Catania, & Maguire, 2010 ; Giannakakos, Vladescu, Kisamore, & Reeve, 2016 ). Furthermore, staff effectively learned how to conduct preference assessments after receiving training comprised of video modeling with voiceover instruction (e.g., Delli Bovi, Vladescu, DeBar, Carroll, & Sarokoff, 2017 ).

When incorporating modeling in training, it is important to model the entire procedure for the trainee. In addition, we recommend standardizing the models across training episodes to ensure the relevant skills are being modeled consistently. The latter recommendation may be accomplished by relying on video models or ensuring live models receive written protocols to follow during training. Finally, to aid in generalization, modeling should entail multiple exemplars of the target skill (Moore & Fisher, 2007 ). DiGennaro Reed, Erath, Brand, and Novak ( 2019 ) provide resources for creating video models, which readers may find beneficial.

The third component of BST, rehearsal—also referred to as practice or role play—involves having trainees practice a target skill (Miltenberger, 2016 ). Rehearsal can be arranged in multiple ways, such as using a trained researcher or confederate (e.g., Iwata et al., 2000 ; McGimsey, Greene, & Lutzker, 1995 ; Phillips & Mudford, 2008 ), another trainee who is acquiring the skill being rehearsed (e.g., Palmen, Didden, & Korzilius, 2010 ; Wallace, Doney, Mintz-Resudek, & Tarbox, 2004 ), a service recipient (e.g., Erbas, Tekin-Iftar, & Yucesoy, 2006 ), or by varying the number of rehearsal opportunities (e.g., Jenkins & DiGennaro Reed, 2016 ). An important distinction is that rehearsal alone does not guarantee high levels of performance; in fact, it may allow trainees to practice errors, which may impede acquisition (Ward-Horner & Sturmey, 2012 ). Thus, rehearsal is typically accompanied by performance feedback and continues until trainees achieve mastery (Reid, Parsons, & Green, 2011 ).

In suggesting guidelines for trainers, we offer that practice does not make perfect; rather, practice with feedback makes perfect. That is, feedback should be delivered immediately following each rehearsal opportunity; thus, rehearsal and feedback should occur in tandem. Feedback is described in more detail in the next section. To help trainees acquire all relevant skills, the trainer must engineer opportunities for the trainee to practice the entire procedure, respond to a range of client responses, receive feedback, and meet a mastery criterion. These opportunities include using confederates in-vivo or in an analog setting, and having the confederate behave in scripted or predetermined ways to ensure the trainee practices all the components of a procedure and responds to a range of behaviors. Allowing trainees to respond to many situations is important, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations and procedures that need to be implemented with high integrity.

The fourth component of BST is feedback, which refers to information about past performance that specifies how the trainee can improve performance in the future (Miltenberger, 2016 ). At this stage of training, feedback should be delivered immediately after each rehearsal opportunity and specify steps performed correctly and steps requiring correction (DiGennaro Reed et al., 2018 ). Several reviews of the literature reveal there are various dimensions of feedback, such as its source (supervisor, peer), medium or mode (written, verbal), frequency (daily, weekly), recipients (individuals, groups), privacy (private, public), and content (type of information provided; Alvero, Bucklin, & Austin, 2001 ; Balcazar, Hopkins, & Suarez, 1985 ; Prue & Fairbank, 1981 ). In addition, the way in which corrective and positive feedback are sequenced can influence its efficacy (Henley & DiGennaro Reed, 2015 ; Slowiak & Lakowske, 2017 ). Although supervisors and trainers have flexibility regarding how to implement the various dimensions of feedback, it is likely most efficient and effective to deliver both corrective and positive verbal feedback immediately upon completion of rehearsal.

The numerous variations and dimensions of feedback present a challenge to researchers seeking to examine the most effective combinations. Thus, no practice recommendations with an exact combination of methods can be made, which may be impractical as most supervisors are subject to various organizational and logistical constraints that limit their control over certain factors. However, research on the dimensions of feedback and its delivery has produced results with enough consistency to support general practice guidelines.

We recommend trainers base their feedback on direct observations rather than verbal reports or indirect measures. The use of observational data provides important information for the trainer and may also be used as a data source for delivering feedback. Next, trainee performance may improve faster if corrective feedback is presented before positive feedback (Henley & DiGennaro Reed, 2015 ); however, we often ask trainees to specify their preference for the order in which feedback is delivered. Third, supervisors should deliver feedback immediately after performance, as research suggests immediate feedback is more effective than delayed feedback (Goodman, Brady, Duffy, Scott, & Pollard, 2008 ) and staff prefer immediate feedback compared to delayed feedback (Reid & Parsons, 1996 ). We also recommend that feedback is used in conjunction with the components of BST described previously. Finally, it is important that feedback is delivered in a respectful and professional manner to maintain a positive working relationship, in particular when corrective feedback must be shared.

Ongoing Staff Support

It would be a mistake to assume that, once preservice training is complete, staff will perform all skills with high integrity while on the job and in a complex real-world environment. Thus, high-quality preservice training should be viewed as the initial investment in the professional development of staff. Based on decades of research, it is reasonable to assume that staff may not generalize skills learned in a contrived training environment to the actual work setting or maintain high levels of performance over extended periods of time. To address these challenges and support the maintenance and growth of staff skills, ongoing coaching is necessary. In the following sections, we outline how supervisors can provide ongoing support to staff following preservice training.

Observations and Feedback

The next step in the training process is the provision of ongoing supervision and support. This usually involves supervisory observations of the staff implementing varied procedures. The purpose of direct observations is twofold: to provide the supervisor with opportunities to monitor treatment integrity in the natural environment and to use data to provide performance feedback to staff. Depending on contextual variables operating in the organization (e.g., staff schedules, supervisor schedules, the setting), these observations can vary widely in when, how, and how often they are employed. For example, observations can be scheduled in advance or unscheduled drop-ins ( when ); viewed live (i.e., in-vivo) or via video recordings ( how ); and conducted as often or as little as needed, depending on staff performance, feasibility, and other related variables ( how often ).

Although variability exists regarding how supervisory observations are implemented, one commonality across all variations is to ensure recommended practices are being used. Table Table1 1 depicts an on-the-job training protocol (adapted from Ricciardi, 2005 ) for using recommended practices to conduct ongoing observations. This protocol uses a competency-based approach to training (e.g., Reid & Parsons, 2002 ), and shares many of the same components used in initial training procedures (e.g., instruction, rehearsal, performance feedback). Thus, divergence from initial training procedures is more in relation to the training process , not training content , wherein the goal of ongoing supervision observations is to provide practice opportunities for staff to demonstrate high levels of treatment integrity in their actual workplace setting. The provision of supervision and support in this capacity also affords other benefits, such as the opportunity for supervisors and staff to troubleshoot issues regarding implementation in practice—an issue which may not have been present in the controlled training settings where initial training typically occurs. Related to this, supervisors can also embed coaching procedures (e.g., prompting, prompt fading, reinforcement) into their observations to facilitate staff implementation at mastery levels.

On-the-job training protocol (adapted from Ricciardi, 2005 )

Pay for Performance

An important consideration for maintaining desirable performance is the method by which staff are compensated for their work. Most compensation systems in the United States involve pay-for-time systems, in which compensation is primarily based on the amount of time spent at work, not performance of job duties. The prevalence of pay-for-time systems presents an interesting challenge for behavior-analyst supervisors, as the primary contingency (i.e., pay) is delivered largely independent of performance of job duties. Although pay-for-performance systems likely maintain higher quality and quantity work than pay-for-time, several factors impede implementation of the pay-for-performance systems.

The first barrier to performance-contingent pay is that many supervisors may not be in a position in their organization where they are able to dramatically change existing pay structures. Those supervisors who have control over organizational pay structures would also be likely to experience resistance from staff due to the ubiquity of traditional pay structures. A second barrier to pay-for-performance systems is a concern that these systems may place undue stress on employees—because their income is tied directly to their performance (Ganster, Kiersch, Marsh, & Bowen, 2011 ). This issue is made worse when incentive systems are dependent on factors beyond staff control.

Notwithstanding these barriers, supervisors must identify methods for reinforcing desirable performance within a traditional pay-for-performance system. A large body of research on the use of incentives in organizational settings suggests that desirable staff performance can be maintained by monetary incentives that account for a relatively small proportion of total compensation for staff (e.g., Dickinson & Gillette, 1994 ). That is, desired performance is maintained by the presence of an incentive contingency, not the percentage of incentive pay (Poling, Dickinson, Austin, & Normand, 2000 ). Thus, one solution may be for supervisors to use monetary incentives in conjunction with traditional pay systems—readers in organizations capable of and interested in providing performance-based pay are directed to Abernathy ( 1996 , 2014 ) for additional resources. Note that this type of system is not without limitations. First, monetary incentives must be arranged so they are sustainable over an extended duration, and many human-service settings simply do not have the funds to maintain these efforts. Second, monetary incentives may be subject to certain federal and state labor regulations (e.g., Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 ), which may create unwanted logistical difficulties for an organization. Thus, despite the advantages of using a generalized conditioned reinforcer in the form of monetary incentives, supervisors may seek alternative forms of incentive delivery to maintain desirable staff performance.

Identifying Potential Incentives

Although supervisors may feel confident in their ability to select effective nonmonetary incentives for their staff, we urge caution in doing so. Wilder, Rost, and McMahon ( 2007 ) asked supervisors to rank-order potential incentives based on how effective they thought the incentive would be for each of their employees. When comparing supervisor predictions with employee rankings, Wilder et al. observed high agreement between supervisors’ indication of their employees’ most preferred items or activities; however, few supervisors accurately predicted moderate- and lower-preferred items or activities. These findings were replicated by Wilder, Harris, Casella, Wine, and Postma ( 2011 ) and suggest that supervisors generally do a poor job at predicting effective incentives.

Daniels and Bailey ( 2014 ) offer a systematic procedure to assist with selecting incentives. First, supervisors should consider what types of incentives they can reasonably provide. At this stage it is important to consider that incentives may be a mix of items, activities, or privileges. Whereas monetary and most tangible incentives have an inherent cost to an organization, many activities or privileges may come at little or no cost. For example, Iwata, Bailey, Brown, Foshee, and Alpern ( 1976 ) maintained high levels of daily care and training activities from staff working in a residential facility using an incentive where staff could rearrange their days off for the following week. Another important consideration at this stage is that supervisors should select items or activities that are sustainable for use for the indefinite future. Although reinforcement schedules may be thinned over time, the incentive program is only effective for as long as it is being implemented. Supervisors may need to have conversations with their organization’s management to identify incentives that the organization allows and can support—so the supervisor does not have to pay for it out-of-pocket.

Second, supervisors may wish to discuss these options for potential incentives with staff to identify a small number of items, activities, or privileges. This step should be conducted after first identifying potential items and activities because, otherwise, employees do not know what is available or may ask for things that cannot be delivered (see Daniels & Bailey, 2014 ).

Finally, after potential incentives have been identified, supervisors should conduct a systematic preference assessment with staff. Although there is a rich literature evaluating methods for assessing preference in clinical populations with limited verbal repertoires (e.g., Fisher et al., 1992 ), these methods are likely not appropriate for staff with strong verbal repertoires (see Waldvogel & Dixon, 2008 ). Two commonly used methods for assessing employee preference for incentives are a reinforcer survey (Daniels & Bailey, 2014 ) and a ranking procedure (Waldvogel & Dixon, 2008 ; Wine, Reis, & Hantula, 2014 ). The reinforcer survey asks employees to rate how much work they would be willing to do for each item or activity on a Likert-type scale from 0 ( none at all ) to 4 ( very much ). The ranking procedure is similar but provides a relative value for each potential incentive by asking employees to rank the items or activities from least to most preferred. Both the survey and ranking procedure provide relatively accurate indications of effective incentives—although the survey method may be better at identifying a greater range of effective incentives (see Wine et al., 2014 for a comparison).

Incentive Delivery

A final consideration for ensuring effective use of incentives is the way they are delivered. Some variables that warrant additional consideration for use with staff include incentive quality, probability of delivery, and delay to delivery. Incentive quality is largely determined by preference, although incentive magnitude and schedule also affect quality. Incentives may be delivered on a dense schedule initially and thinned once the employee has consistently demonstrated desired performance. Two considerations with respect to quality are that staff preferences may shift over time (Wine, Gilroy, & Hantula, 2012 ) and the use of incentives of varied preference may maintain high levels of performance (Wine & Wilder, 2009 ). Thus, supervisors should consider assessing preference on a regular basis and using a variety of moderate- to high-preferred incentives.

Although rules can help bridge the gap of delays to reinforcement, supervisors should seek to minimize delays as much as possible. In addition, with respect to the probability of incentive delivery, reinforcers may not need to be delivered each time. Though there is little research assessing probability of incentive delivery in OBM settings, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of lottery systems at maintaining performance (e.g., Cook & Dixon, 2006 ; Iwata et al., 1976 ). Taken together, there has been little OBM research assessing the relative impact of reinforcer dimensions. However, recent research incorporating the area of behavioral economics has provided a promising methodology through which a thorough understanding may be developed (e.g., Henley, DiGennaro Reed, Reed, & Kaplan, 2016 ; Wine et al., 2012 ).

Assessing Performance Problems

Despite best efforts to train and provide follow-up support to staff, supervisors will likely encounter instances of less-than-desirable performance. As is true with service delivery in clinical populations, performance management interventions typically provide benefit when they are informed by preintervention functional assessment. Though several informant assessments exist and have been implemented with success (e.g., Daniels & Lattal, 2017 ; Mager & Pipe, 1984 ), the Performance Diagnostic Checklist–Human Services (PDC–HS; Carr, Wilder, Majdalany, Mathisen, & Strain, 2013 ) has emerging support for use in human-service settings. The PDC–HS may be especially advantageous for BCBAs in supervisory positions who may have limited OBM experience as it is less time consuming and does not require the same level of expertise as behavioral systems analysis (for more information about behavioral systems analysis, see Johnson, Casella, McGee, & Lee, 2014 ; McGee & Diener, 2010 ; Sigurdsson & McGee, 2015 ). The PDC–HS is an informant assessment that may be used to identify variables causing or maintaining substandard performance. The assessment consists of 20 questions across four domains: (a) training; (b) task clarification and prompting; (c) resources, materials, and processes; and (d) performance consequences, effort, and competition. As its name suggests, the PDC–HS was developed specifically for use in human service settings, and the questions and domains were developed to target environmental variables that commonly affect performance in this particular setting.

The first section, training , contains questions about the type of training received and whether the employee has demonstrated desired levels of performance in the past. The second section, task clarification and prompting , includes questions about the employee’s knowledge of job requirements and the environment where the behavior is expected to occur. Third, the resources, materials, and processes section contains questions about the organization’s systems and resources that may be beyond the employee’s control. Finally, the performance consequences, effort, and competition section includes questions about overall supervisor support and supervision, feedback, and potential competing activities.

Carr et al. ( 2013 ) indicated that seven of the items on the PDC–HS can be answered through direct observation and recommended administering the remaining 13 items through discussion with the employee’s supervisor. Practitioners administering the PDC–HS might consider also administering it with multiple supervisors or across different levels of the organization (e.g., management, supervisors, employees) as there may not be 100% agreement across all relevant parties (e.g., Merritt, DiGennaro Reed, & Martinez, 2019 ).

When complete, results of the PDC–HS are scored by counting the number of items for which an area of concern was flagged in each domain (see Carr & Wilder, 2016 ; Carr et al., 2013 ); the domain with the most flagged items typically indicates the “function” of the performance problem, or the area to be targeted for intervention. Where the PDC–HS may be particularly useful is the accompanying intervention planning guide, which provides a list of recommended interventions (with supporting literature) for each domain. For example, Bowe and Sellers ( 2018 ) conducted a PDC–HS to assess inaccurate implementation of error correction procedures during teaching sessions, and results indicated that insufficient training was likely the greatest contributing factor for performance problems. The experimenters then compared an indicated intervention of BST with an intervention recommended in the task clarification and prompting domain (posting reminders; i.e., a nonindicated intervention) and found that performance improved only following the indicated intervention. In sum, the PDC–HS is particularly beneficial for supervisors in human service settings as it provides a systematic assessment of performance problems, is tailored specifically for use in human service settings, and helps supervisors select a function-indicated intervention.

Continuing Education for Staff

As employees continue their professional growth at an organization, their interests may begin to extend beyond the scope of what a supervisor is able to provide. These interests may be viewed as an opportunity to develop skills by facilitating additional learning opportunities. Many of the approaches described in the section below on staying up to date with research can also be adapted for staff development. For example, a supervisor may encourage staff to attend regional conferences or workshops by providing time off work or assisting with registration costs. Those who oversee a large number of staff may consider inviting speakers to deliver workshops on topics related to the services the organization provides. By facilitating continuing education opportunities, supervisors create varied learning opportunities for staff while also creating natural rewards for staff who stay with an organization.

Staying Up to Date in Performance Management Research

Staying current with the research literature is an important skill for practitioners as it may foster the provision of high-quality supervision, training, and services across all levels of the organization. Section 1.01 of the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code includes a provision that states “behavior analysts rely on professionally derived knowledge based on science and behavior analysis when making scientific or professional judgements in human service provision, or when engaging in scholarly or professional endeavors” (BACB, 2014 , p. 4). To meet this standard, credentialed behavior analysts must remain abreast of current scientific findings. At the broadest level, this often involves various classes of behavior that can be categorized into two areas: (a) attending professional development opportunities and (b) reading peer-reviewed publications in staff training and performance management.

Attending professional development opportunities often means attending local, regional, and/or international behavior-analytic conferences and workshops to learn about recent developments in a given area. With current technology, webinars, online-based trainings, and podcasts may be options. For example, the OBM Network ( http://obmnetwork.com ) provides numerous webinars from excellent researchers in the field of OBM on topics such as feedback, remote supervision, pay-for performance, leadership, and staff turnover, among others.