Research Bias 101: What You Need To Know

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | September 2022

If you’re new to academic research, research bias (also sometimes called researcher bias) is one of the many things you need to understand to avoid compromising your study. If you’re not careful, research bias can ruin the credibility of your study.

In this post, we’ll unpack the thorny topic of research bias. We’ll explain what it is , look at some common types of research bias and share some tips to help you minimise the potential sources of bias in your research.

Overview: Research Bias 101

- What is research bias (or researcher bias)?

- Bias #1 – Selection bias

- Bias #2 – Analysis bias

- Bias #3 – Procedural (admin) bias

So, what is research bias?

Well, simply put, research bias is when the researcher – that’s you – intentionally or unintentionally skews the process of a systematic inquiry , which then of course skews the outcomes of the study . In other words, research bias is what happens when you affect the results of your research by influencing how you arrive at them.

For example, if you planned to research the effects of remote working arrangements across all levels of an organisation, but your sample consisted mostly of management-level respondents , you’d run into a form of research bias. In this case, excluding input from lower-level staff (in other words, not getting input from all levels of staff) means that the results of the study would be ‘biased’ in favour of a certain perspective – that of management.

Of course, if your research aims and research questions were only interested in the perspectives of managers, this sampling approach wouldn’t be a problem – but that’s not the case here, as there’s a misalignment between the research aims and the sample .

Now, it’s important to remember that research bias isn’t always deliberate or intended. Quite often, it’s just the result of a poorly designed study, or practical challenges in terms of getting a well-rounded, suitable sample. While perfect objectivity is the ideal, some level of bias is generally unavoidable when you’re undertaking a study. That said, as a savvy researcher, it’s your job to reduce potential sources of research bias as much as possible.

To minimize potential bias, you first need to know what to look for . So, next up, we’ll unpack three common types of research bias we see at Grad Coach when reviewing students’ projects . These include selection bias , analysis bias , and procedural bias . Keep in mind that there are many different forms of bias that can creep into your research, so don’t take this as a comprehensive list – it’s just a useful starting point.

Bias #1 – Selection Bias

First up, we have selection bias . The example we looked at earlier (about only surveying management as opposed to all levels of employees) is a prime example of this type of research bias. In other words, selection bias occurs when your study’s design automatically excludes a relevant group from the research process and, therefore, negatively impacts the quality of the results.

With selection bias, the results of your study will be biased towards the group that it includes or favours, meaning that you’re likely to arrive at prejudiced results . For example, research into government policies that only includes participants who voted for a specific party is going to produce skewed results, as the views of those who voted for other parties will be excluded.

Selection bias commonly occurs in quantitative research , as the sampling strategy adopted can have a major impact on the statistical results . That said, selection bias does of course also come up in qualitative research as there’s still plenty room for skewed samples. So, it’s important to pay close attention to the makeup of your sample and make sure that you adopt a sampling strategy that aligns with your research aims. Of course, you’ll seldom achieve a perfect sample, and that okay. But, you need to be aware of how your sample may be skewed and factor this into your thinking when you analyse the resultant data.

Need a helping hand?

Bias #2 – Analysis Bias

Next up, we have analysis bias . Analysis bias occurs when the analysis itself emphasises or discounts certain data points , so as to favour a particular result (often the researcher’s own expected result or hypothesis). In other words, analysis bias happens when you prioritise the presentation of data that supports a certain idea or hypothesis , rather than presenting all the data indiscriminately .

For example, if your study was looking into consumer perceptions of a specific product, you might present more analysis of data that reflects positive sentiment toward the product, and give less real estate to the analysis that reflects negative sentiment. In other words, you’d cherry-pick the data that suits your desired outcomes and as a result, you’d create a bias in terms of the information conveyed by the study.

Although this kind of bias is common in quantitative research, it can just as easily occur in qualitative studies, given the amount of interpretive power the researcher has. This may not be intentional or even noticed by the researcher, given the inherent subjectivity in qualitative research. As humans, we naturally search for and interpret information in a way that confirms or supports our prior beliefs or values (in psychology, this is called “confirmation bias”). So, don’t make the mistake of thinking that analysis bias is always intentional and you don’t need to worry about it because you’re an honest researcher – it can creep up on anyone .

To reduce the risk of analysis bias, a good starting point is to determine your data analysis strategy in as much detail as possible, before you collect your data . In other words, decide, in advance, how you’ll prepare the data, which analysis method you’ll use, and be aware of how different analysis methods can favour different types of data. Also, take the time to reflect on your own pre-conceived notions and expectations regarding the analysis outcomes (in other words, what do you expect to find in the data), so that you’re fully aware of the potential influence you may have on the analysis – and therefore, hopefully, can minimize it.

Bias #3 – Procedural Bias

Last but definitely not least, we have procedural bias , which is also sometimes referred to as administration bias . Procedural bias is easy to overlook, so it’s important to understand what it is and how to avoid it. This type of bias occurs when the administration of the study, especially the data collection aspect, has an impact on either who responds or how they respond.

A practical example of procedural bias would be when participants in a study are required to provide information under some form of constraint. For example, participants might be given insufficient time to complete a survey, resulting in incomplete or hastily-filled out forms that don’t necessarily reflect how they really feel. This can happen really easily, if, for example, you innocently ask your participants to fill out a survey during their lunch break.

Another form of procedural bias can happen when you improperly incentivise participation in a study. For example, offering a reward for completing a survey or interview might incline participants to provide false or inaccurate information just to get through the process as fast as possible and collect their reward. It could also potentially attract a particular type of respondent (a freebie seeker), resulting in a skewed sample that doesn’t really reflect your demographic of interest.

The format of your data collection method can also potentially contribute to procedural bias. If, for example, you decide to host your survey or interviews online, this could unintentionally exclude people who are not particularly tech-savvy, don’t have a suitable device or just don’t have a reliable internet connection. On the flip side, some people might find in-person interviews a bit intimidating (compared to online ones, at least), or they might find the physical environment in which they’re interviewed to be uncomfortable or awkward (maybe the boss is peering into the meeting room, for example). Either way, these factors all result in less useful data.

Although procedural bias is more common in qualitative research, it can come up in any form of fieldwork where you’re actively collecting data from study participants. So, it’s important to consider how your data is being collected and how this might impact respondents. Simply put, you need to take the respondent’s viewpoint and think about the challenges they might face, no matter how small or trivial these might seem. So, it’s always a good idea to have an informal discussion with a handful of potential respondents before you start collecting data and ask for their input regarding your proposed plan upfront.

Let’s Recap

Ok, so let’s do a quick recap. Research bias refers to any instance where the researcher, or the research design , negatively influences the quality of a study’s results, whether intentionally or not.

The three common types of research bias we looked at are:

- Selection bias – where a skewed sample leads to skewed results

- Analysis bias – where the analysis method and/or approach leads to biased results – and,

- Procedural bias – where the administration of the study, especially the data collection aspect, has an impact on who responds and how they respond.

As I mentioned, there are many other forms of research bias, but we can only cover a handful here. So, be sure to familiarise yourself with as many potential sources of bias as possible to minimise the risk of research bias in your study.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

This is really educational and I really like the simplicity of the language in here, but i would like to know if there is also some guidance in regard to the problem statement and what it constitutes.

Do you have a blog or video that differentiates research assumptions, research propositions and research hypothesis?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

What is research bias?

Understanding unconscious bias, how to avoid bias in research, bias and subjectivity in research.

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Bias in research

In a purely objective world, research bias would not exist because knowledge would be a fixed and unmovable resource; either one knows about a particular concept or phenomenon, or they don't. However, qualitative research and the social sciences both acknowledge that subjectivity and bias exist in every aspect of the social world, which naturally includes the research process too. This bias is manifest in the many different ways that knowledge is understood, constructed, and negotiated, both in and out of research.

Understanding research bias has profound implications for data collection methods and data analysis , requiring researchers to take particular care of how to account for the insights generated from their data .

Research bias, often unavoidable, is a systematic error that can creep into any stage of the research process , skewing our understanding and interpretation of findings. From data collection to analysis, interpretation , and even publication , bias can distort the truth we seek to capture and communicate in our research.

It’s also important to distinguish between bias and subjectivity, especially when engaging in qualitative research . Most qualitative methodologies are based on epistemological and ontological assumptions that there is no such thing as a fixed or objective world that exists “out there” that can be empirically measured and understood through research. Rather, many qualitative researchers embrace the socially constructed nature of our reality and thus recognize that all data is produced within a particular context by participants with their own perspectives and interpretations. Moreover, the researcher’s own subjective experiences inevitably shape how they make sense of the data. These subjectivities are considered to be strengths, not limitations, of qualitative research approaches, because they open new avenues for knowledge generation. This is also why reflexivity is so important in qualitative research. When we refer to bias in this guide, on the other hand, we are referring to systematic errors that can negatively affect the research process but that can be mitigated through researchers’ careful efforts.

To fully grasp what research bias is, it's essential to understand the dual nature of bias. Bias is not inherently evil. It's simply a tendency, inclination, or prejudice for or against something. In our daily lives, we're subject to countless biases, many of which are unconscious. They help us navigate our world, make quick decisions, and understand complex situations. But when conducting research, these same biases can cause significant issues.

Research bias can affect the validity and credibility of research findings, leading to erroneous conclusions. It can emerge from the researcher's subconscious preferences or the methodological design of the study itself. For instance, if a researcher unconsciously favors a particular outcome of the study, this preference could affect how they interpret the results, leading to a type of bias known as confirmation bias.

Research bias can also arise due to the characteristics of study participants. If the researcher selectively recruits participants who are more likely to produce desired outcomes, this can result in selection bias.

Another form of bias can stem from data collection methods . If a survey question is phrased in a way that encourages a particular response, this can introduce response bias. Moreover, inappropriate survey questions can have a detrimental effect on future research if such studies are seen by the general population as biased toward particular outcomes depending on the preferences of the researcher.

Bias can also occur during data analysis . In qualitative research for instance, the researcher's preconceived notions and expectations can influence how they interpret and code qualitative data, a type of bias known as interpretation bias. It's also important to note that quantitative research is not free of bias either, as sampling bias and measurement bias can threaten the validity of any research findings.

Given these examples, it's clear that research bias is a complex issue that can take many forms and emerge at any stage in the research process. This section will delve deeper into specific types of research bias, provide examples, discuss why it's an issue, and provide strategies for identifying and mitigating bias in research.

What is an example of bias in research?

Bias can appear in numerous ways. One example is confirmation bias, where the researcher has a preconceived explanation for what is going on in their data, and any disconfirming evidence is (unconsciously) ignored. For instance, a researcher conducting a study on daily exercise habits might be inclined to conclude that meditation practices lead to greater engagement in exercise because that researcher has personally experienced these benefits. However, conducting rigorous research entails assessing all the data systematically and verifying one’s conclusions by checking for both supporting and refuting evidence.

What is a common bias in research?

Confirmation bias is one of the most common forms of bias in research. It happens when researchers unconsciously focus on data that supports their ideas while ignoring or undervaluing data that contradicts their ideas. This bias can lead researchers to mistakenly confirm their theories, despite having insufficient or conflicting evidence.

What are the different types of bias?

There are several types of research bias, each presenting unique challenges. Some common types include:

Confirmation bias: As already mentioned, this happens when a researcher focuses on evidence supporting their theory while overlooking contradictory evidence.

Selection bias: This occurs when the researcher's method of choosing participants skews the sample in a particular direction.

Response bias: This happens when participants in a study respond inaccurately or falsely, often due to misleading or poorly worded questions.

Observer bias (or researcher bias): This occurs when the researcher unintentionally influences the results because of their expectations or preferences.

Publication bias: This type of bias arises when studies with positive results are more likely to get published, while studies with negative or null results are often ignored.

Analysis bias: This type of bias occurs when the data is manipulated or analyzed in a way that leads to a particular result, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

What is an example of researcher bias?

Researcher bias, also known as observer bias, can occur when a researcher's expectations or personal beliefs influence the results of a study. For instance, if a researcher believes that a particular therapy is effective, they might unconsciously interpret ambiguous results in a way that supports the efficacy of the therapy, even if the evidence is not strong enough.

Even quantitative research methodologies are not immune from bias from researchers. Market research surveys or clinical trial research, for example, may encounter bias when the researcher chooses a particular population or methodology to achieve a specific research outcome. Questions in customer feedback surveys whose data is employed in quantitative analysis can be structured in such a way as to bias survey respondents toward certain desired answers.

Turn your data into findings with ATLAS.ti

Key insights are at your fingertips with our powerful interface. See how with a free trial.

Identifying and avoiding bias in research

As we will remind you throughout this chapter, bias is not a phenomenon that can be removed altogether, nor should we think of it as something that should be eliminated. In a subjective world involving humans as researchers and research participants, bias is unavoidable and almost necessary for understanding social behavior. The section on reflexivity later in this guide will highlight how different perspectives among researchers and human subjects are addressed in qualitative research. That said, bias in excess can place the credibility of a study's findings into serious question. Scholars who read your research need to know what new knowledge you are generating, how it was generated, and why the knowledge you present should be considered persuasive. With that in mind, let's look at how bias can be identified and, where it interferes with research, minimized.

How do you identify bias in research?

Identifying bias involves a critical examination of your entire research study involving the formulation of the research question and hypothesis , the selection of study participants, the methods for data collection, and the analysis and interpretation of data. Researchers need to assess whether each stage has been influenced by bias that may have skewed the results. Tools such as bias checklists or guidelines, peer review , and reflexivity (reflecting on one's own biases) can be instrumental in identifying bias.

How do you identify research bias?

Identifying research bias often involves careful scrutiny of the research methodology and the researcher's interpretations. Was the sample of participants relevant to the research question ? Were the interview or survey questions leading? Were there any conflicts of interest that could have influenced the results? It also requires an understanding of the different types of bias and how they might manifest in a research context. Does the bias occur in the data collection process or when the researcher is analyzing data?

Research transparency requires a careful accounting of how the study was designed, conducted, and analyzed. In qualitative research involving human subjects, the researcher is responsible for documenting the characteristics of the research population and research context. With respect to research methods, the procedures and instruments used to collect and analyze data are described in as much detail as possible.

While describing study methodologies and research participants in painstaking detail may sound cumbersome, a clear and detailed description of the research design is necessary for good research. Without this level of detail, it is difficult for your research audience to identify whether bias exists, where bias occurs, and to what extent it may threaten the credibility of your findings.

How to recognize bias in a study?

Recognizing bias in a study requires a critical approach. The researcher should question every step of the research process: Was the sample of participants selected with care? Did the data collection methods encourage open and sincere responses? Did personal beliefs or expectations influence the interpretation of the results? External peer reviews can also be helpful in recognizing bias, as others might spot potential issues that the original researcher missed.

The subsequent sections of this chapter will delve into the impacts of research bias and strategies to avoid it. Through these discussions, researchers will be better equipped to handle bias in their work and contribute to building more credible knowledge.

Unconscious biases, also known as implicit biases, are attitudes or stereotypes that influence our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. These biases can inadvertently infiltrate the research process, skewing the results and conclusions. This section aims to delve deeper into understanding unconscious bias, its impact on research, and strategies to mitigate it.

What is unconscious bias?

Unconscious bias refers to prejudices or social stereotypes about certain groups that individuals form outside their conscious awareness. Everyone holds unconscious beliefs about various social and identity groups, and these biases stem from a tendency to organize social worlds into categories.

How does unconscious bias infiltrate research?

Unconscious bias can infiltrate research in several ways. It can affect how researchers formulate their research questions or hypotheses , how they interact with participants, their data collection methods, and how they interpret their data . For instance, a researcher might unknowingly favor participants who share similar characteristics with them, which could lead to biased results.

Implications of unconscious bias

The implications of unconscious research bias are far-reaching. It can compromise the validity of research findings , influence the choice of research topics, and affect peer review processes . Unconscious bias can also lead to a lack of diversity in research, which can severely limit the value and impact of the findings.

Strategies to mitigate unconscious research bias

While it's challenging to completely eliminate unconscious bias, several strategies can help mitigate its impact. These include being aware of potential unconscious biases, practicing reflexivity , seeking diverse perspectives for your study, and engaging in regular bias-checking activities, such as bias training and peer debriefing .

By understanding and acknowledging unconscious bias, researchers can take steps to limit its impact on their work, leading to more robust findings.

Why is researcher bias an issue?

Research bias is a pervasive issue that researchers must diligently consider and address. It can significantly impact the credibility of findings. Here, we break down the ramifications of bias into two key areas.

How bias affects validity

Research validity refers to the accuracy of the study findings, or the coherence between the researcher’s findings and the participants’ actual experiences. When bias sneaks into a study, it can distort findings and move them further away from the realities that were shared by the research participants. For example, if a researcher's personal beliefs influence their interpretation of data , the resulting conclusions may not reflect what the data show or what participants experienced.

The transferability problem

Transferability is the extent to which your study's findings can be applied beyond the specific context or sample studied. Applying knowledge from one context to a different context is how we can progress and make informed decisions. In quantitative research , the generalizability of a study is a key component that shapes the potential impact of the findings. In qualitative research , all data and knowledge that is produced is understood to be embedded within a particular context, so the notion of generalizability takes on a slightly different meaning. Rather than assuming that the study participants are statistically representative of the entire population, qualitative researchers can reflect on which aspects of their research context bear the most weight on their findings and how these findings may be transferable to other contexts that share key similarities.

How does bias affect research?

Research bias, if not identified and mitigated, can significantly impact research outcomes. The ripple effects of research bias extend beyond individual studies, impacting the body of knowledge in a field and influencing policy and practice. Here, we delve into three specific ways bias can affect research.

Distortion of research results

Bias can lead to a distortion of your study's findings. For instance, confirmation bias can cause a researcher to focus on data that supports their interpretation while disregarding data that contradicts it. This can skew the results and create a misleading picture of the phenomenon under study.

Undermining scientific progress

When research is influenced by bias, it not only misrepresents participants’ realities but can also impede scientific progress. Biased studies can lead researchers down the wrong path, resulting in wasted resources and efforts. Moreover, it could contribute to a body of literature that is skewed or inaccurate, misleading future research and theories.

Influencing policy and practice based on flawed findings

Research often informs policy and practice. If the research is biased, it can lead to the creation of policies or practices that are ineffective or even harmful. For example, a study with selection bias might conclude that a certain intervention is effective, leading to its broad implementation. However, suppose the transferability of the study's findings was not carefully considered. In that case, it may be risky to assume that the intervention will work as well in different populations, which could lead to ineffective or inequitable outcomes.

While it's almost impossible to eliminate bias in research entirely, it's crucial to mitigate its impact as much as possible. By employing thoughtful strategies at every stage of research, we can strive towards rigor and transparency , enhancing the quality of our findings. This section will delve into specific strategies for avoiding bias.

How do you know if your research is biased?

Determining whether your research is biased involves a careful review of your research design, data collection , analysis , and interpretation . It might require you to reflect critically on your own biases and expectations and how these might have influenced your research. External peer reviews can also be instrumental in spotting potential bias.

Strategies to mitigate bias

Minimizing bias involves careful planning and execution at all stages of a research study. These strategies could include formulating clear, unbiased research questions , ensuring that your sample meaningfully represents the research problem you are studying, crafting unbiased data collection instruments, and employing systematic data analysis techniques. Transparency and reflexivity throughout the process can also help minimize bias.

Mitigating bias in data collection

To mitigate bias in data collection, ensure your questions are clear, neutral, and not leading. Triangulation, or using multiple methods or data sources, can also help to reduce bias and increase the credibility of your findings.

Mitigating bias in data analysis

During data analysis , maintaining a high level of rigor is crucial. This might involve using systematic coding schemes in qualitative research or appropriate statistical tests in quantitative research . Regularly questioning your interpretations and considering alternative explanations can help reduce bias. Peer debriefing , where you discuss your analysis and interpretations with colleagues, can also be a valuable strategy.

By using these strategies, researchers can significantly reduce the impact of bias on their research, enhancing the quality and credibility of their findings and contributing to a more robust and meaningful body of knowledge.

Impact of cultural bias in research

Cultural bias is the tendency to interpret and judge phenomena by standards inherent to one's own culture. Given the increasingly multicultural and global nature of research, understanding and addressing cultural bias is paramount. This section will explore the concept of cultural bias, its impacts on research, and strategies to mitigate it.

What is cultural bias in research?

Cultural bias refers to the potential for a researcher's cultural background, experiences, and values to influence the research process and findings. This can occur consciously or unconsciously and can lead to misinterpretation of data, unfair representation of cultures, and biased conclusions.

How does cultural bias infiltrate research?

Cultural bias can infiltrate research at various stages. It can affect the framing of research questions , the design of the study, the methods of data collection , and the interpretation of results . For instance, a researcher might unintentionally design a study that does not consider the cultural context of the participants, leading to a biased understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

Implications of cultural bias

The implications of cultural bias are profound. Cultural bias can skew your findings, limit the transferability of results, and contribute to cultural misunderstandings and stereotypes. This can ultimately lead to inaccurate or ethnocentric conclusions, further perpetuating cultural bias and inequities.

As a result, many social science fields like sociology and anthropology have been critiqued for cultural biases in research. Some of the earliest research inquiries in anthropology, for example, have had the potential to reduce entire cultures to simplistic stereotypes when compared to mainstream norms. A contemporary researcher respecting ethical and cultural boundaries, on the other hand, should seek to properly place their understanding of social and cultural practices in sufficient context without inappropriately characterizing them.

Strategies to mitigate cultural bias

Mitigating cultural bias requires a concerted effort throughout the research study. These efforts could include educating oneself about other cultures, being aware of one's own cultural biases, incorporating culturally diverse perspectives into the research process, and being sensitive and respectful of cultural differences. It might also involve including team members with diverse cultural backgrounds or seeking external cultural consultants to challenge assumptions and provide alternative perspectives.

By acknowledging and addressing cultural bias, researchers can contribute to more culturally competent, equitable, and valid research. This not only enriches the scientific body of knowledge but also promotes cultural understanding and respect.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Keep in mind that bias is a force to be mitigated, not a phenomenon that can be eliminated altogether, and the subjectivities of each person are what make our world so complex and interesting. As things are continuously changing and adapting, research knowledge is also continuously being updated as we further develop our understanding of the world around us.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Incorporate STEM journalism in your classroom

- Exercise type: Activity

- Topic: Science & Society

- Category: Research & Design

- Category: Diversity in STEM

How bias affects scientific research

- Download Student Worksheet

Purpose: Students will work in groups to evaluate bias in scientific research and engineering projects and to develop guidelines for minimizing potential biases.

Procedural overview: After reading the Science News for Students article “ Think you’re not biased? Think again ,” students will discuss types of bias in scientific research and how to identify it. Students will then search the Science News archive for examples of different types of bias in scientific and medical research. Students will read the National Institute of Health’s Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable and analyze how this policy works to reduce bias in scientific research on the basis of sex and gender. Based on their exploration of bias, students will discuss the benefits and limitations of research guidelines for minimizing particular types of bias and develop guidelines of their own.

Approximate class time: 2 class periods

How Bias Affects Scientific Research student guide

Computer with access to the Science News archive

Interactive meeting and screen-sharing application for virtual learning (optional)

Directions for teachers:

One of the guiding principles of scientific inquiry is objectivity. Objectivity is the idea that scientific questions, methods and results should not be affected by the personal values, interests or perspectives of researchers. However, science is a human endeavor, and experimental design and analysis of information are products of human thought processes. As a result, biases may be inadvertently introduced into scientific processes or conclusions.

In scientific circles, bias is described as any systematic deviation between the results of a study and the “truth.” Bias is sometimes described as a tendency to prefer one thing over another, or to favor one person, thing or explanation in a way that prevents objectivity or that influences the outcome of a study or the understanding of a phenomenon. Bias can be introduced in multiple points during scientific research — in the framing of the scientific question, in the experimental design, in the development or implementation of processes used to conduct the research, during collection or analysis of data, or during the reporting of conclusions.

Researchers generally recognize several different sources of bias, each of which can strongly affect the results of STEM research. Three types of bias that often occur in scientific and medical studies are researcher bias, selection bias and information bias.

Researcher bias occurs when the researcher conducting the study is in favor of a certain result. Researchers can influence outcomes through their study design choices, including who they choose to include in a study and how data are interpreted. Selection bias can be described as an experimental error that occurs when the subjects of the study do not accurately reflect the population to whom the results of the study will be applied. This commonly happens as unequal inclusion of subjects of different races, sexes or genders, ages or abilities. Information bias occurs as a result of systematic errors during the collection, recording or analysis of data.

When bias occurs, a study’s results may not accurately represent phenomena in the real world, or the results may not apply in all situations or equally for all populations. For example, if a research study does not address the full diversity of people to whom the solution will be applied, then the researchers may have missed vital information about whether and how that solution will work for a large percentage of a target population.

Bias can also affect the development of engineering solutions. For example, a new technology product tested only with teenagers or young adults who are comfortable using new technologies may have user experience issues when placed in the hands of older adults or young children.

Want to make it a virtual lesson? Post the links to the Science News for Students article “ Think you’re not biased? Think again ,” and the National Institutes of Health information on sickle-cell disease . A link to additional resources can be provided for the students who want to know more. After students have reviewed the information at home, discuss the four questions in the setup and the sickle-cell research scenario as a class. When the students have a general understanding of bias in research, assign students to breakout rooms to look for examples of different types of bias in scientific and medical research, to discuss the Science News article “ Biomedical studies are including more female subjects (finally) ” and the National Institute of Health’s Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable and to develop bias guidelines of their own. Make sure the students have links to all articles they will need to complete their work. Bring the groups back together for an all-class discussion of the bias guidelines they write.

Assign the Science News for Students article “ Think you’re not biased? Think again ” as homework reading to introduce students to the core concepts of scientific objectivity and bias. Request that they answer the first two questions on their guide before the first class discussion on this topic. In this discussion, you will cover the idea of objective truth and introduce students to the terminology used to describe bias. Use the background information to decide what level of detail you want to give to your students.

As students discuss bias, help them understand objective and subjective data and discuss the importance of gathering both kinds of data. Explain to them how these data differ. Some phenomena — for example, body temperature, blood type and heart rate — can be objectively measured. These data tend to be quantitative. Other phenomena cannot be measured objectively and must be considered subjectively. Subjective data are based on perceptions, feelings or observations and tend to be qualitative rather than quantitative. Subjective measurements are common and essential in biomedical research, as they can help researchers understand whether a therapy changes a patient’s experience. For instance, subjective data about the amount of pain a patient feels before and after taking a medication can help scientists understand whether and how the drug works to alleviate pain. Subjective data can still be collected and analyzed in ways that attempt to minimize bias.

Try to guide student discussion to include a larger context for bias by discussing the effects of bias on understanding of an “objective truth.” How can someone’s personal views and values affect how they analyze information or interpret a situation?

To help students understand potential effects of biases, present them with the following scenario based on information from the National Institutes of Health :

Sickle-cell disease is a group of inherited disorders that cause abnormalities in red blood cells. Most of the people who have sickle-cell disease are of African descent; it also appears in populations from the Mediterranean, India and parts of Latin America. Males and females are equally likely to inherit the condition. Imagine that a therapy was developed to treat the condition, and clinical trials enlisted only male subjects of African descent. How accurately would the results of that study reflect the therapy’s effectiveness for all people who suffer from sickle-cell disease?

In the sickle-cell scenario described above, scientists will have a good idea of how the therapy works for males of African descent. But they may not be able to accurately predict how the therapy will affect female patients or patients of different races or ethnicities. Ask the students to consider how they would devise a study that addressed all the populations affected by this disease.

Before students move on, have them answer the following questions. The first two should be answered for homework and discussed in class along with the remaining questions.

1.What is bias?

In common terms, bias is a preference for or against one idea, thing or person. In scientific research, bias is a systematic deviation between observations or interpretations of data and an accurate description of a phenomenon.

2. How can biases affect the accuracy of scientific understanding of a phenomenon? How can biases affect how those results are applied?

Bias can cause the results of a scientific study to be disproportionately weighted in favor of one result or group of subjects. This can cause misunderstandings of natural processes that may make conclusions drawn from the data unreliable. Biased procedures, data collection or data interpretation can affect the conclusions scientists draw from a study and the application of those results. For example, if the subjects that participate in a study testing an engineering design do not reflect the diversity of a population, the end product may not work as well as desired for all users.

3. Describe two potential sources of bias in a scientific, medical or engineering research project. Try to give specific examples.

Researchers can intentionally or unintentionally introduce biases as a result of their attitudes toward the study or its purpose or toward the subjects or a group of subjects. Bias can also be introduced by methods of measuring, collecting or reporting data. Examples of potential sources of bias include testing a small sample of subjects, testing a group of subjects that is not diverse and looking for patterns in data to confirm ideas or opinions already held.

4. How can potential biases be identified and eliminated before, during or after a scientific study?

Students should brainstorm ways to identify sources of bias in the design of research studies. They may suggest conducting implicit bias testing or interviews before a study can be started, developing guidelines for research projects, peer review of procedures and samples/subjects before beginning a study, and peer review of data and conclusions after the study is completed and before it is published. Students may focus on the ideals of transparency and replicability of results to help reduce biases in scientific research.

Obtain and evaluate information about bias

Students will now work in small groups to select and analyze articles for different types of bias in scientific and medical research. Students will start by searching the Science News or Science News for Students archives and selecting articles that describe scientific studies or engineering design projects. If the Science News or Science News for Students articles chosen by students do not specifically cite and describe a study, students should consult the Citations at the end of the article for links to related primary research papers. Students may need to read the methods section and the conclusions of the primary research paper to better understand the project’s design and to identify potential biases. Do not assume that every scientific paper features biased research.

Student groups should evaluate the study or engineering design project outlined in the article to identify any biases in the experimental design, data collection, analysis or results. Students may need additional guidance for identifying biases. Remind them of the prior discussion about sources of bias and task them to review information about indicators of bias. Possible indicators include extreme language such as all , none or nothing ; emotional appeals rather than logical arguments; proportions of study subjects with specific characteristics such as gender, race or age; arguments that support or refute one position over another and oversimplifications or overgeneralizations. Students may also want to look for clues related to the researchers’ personal identity such as race, religion or gender. Information on political or religious points of view, sources of funding or professional affiliations may also suggest biases.

Students should also identify any deliberate attempts to reduce or eliminate bias in the project or its results. Then groups should come back together and share the results of their analysis with the class.

If students need support in searching the archives for appropriate articles, encourage groups to brainstorm search terms that may turn up related articles. Some potential search terms include bias , study , studies , experiment , engineer , new device , design , gender , sex , race , age , aging , young , old , weight , patients , survival or medical .

If you are short on time or students do not have access to the Science News or Science News for Students archive, you may want to provide articles for students to review. Some suggested articles are listed in the additional resources below.

Once groups have selected their articles, students should answer the following questions in their groups.

1. Record the title and URL of the article and write a brief summary of the study or project.

Answers will vary, but students should accurately cite the article evaluated and summarize the study or project described in the article. Sample answer: We reviewed the Science News article “Even brain images can be biased,” which can be found at www.sciencenews.org/blog/scicurious/even-brain-images-can-be-biased. This article describes how scientific studies of human brains that involve electronic images of brains tend to include study subjects from wealthier and more highly educated households and how researchers set out to collect new data to make the database of brain images more diverse.

2. What sources of potential bias (if any) did you identify in the study or project? Describe any procedures or policies deliberately included in the study or project to eliminate biases.

The article “Even brain images can be biased” describes how scientists identified a sampling bias in studies of brain images that resulted from the way subjects were recruited. Most of these studies were conducted at universities, so many college students volunteer to participate, which resulted in the samples being skewed toward wealthier, educated, white subjects. Scientists identified a database of pediatric brain images and evaluated the diversity of the subjects in that database. They found that although the subjects in that database were more ethnically diverse than the U.S. population, the subjects were generally from wealthier households and the parents of the subjects tended to be more highly educated than average. Scientists applied statistical methods to weight the data so that study samples from the database would more accurately reflect American demographics.

3. How could any potential biases in the study or design project have affected the results or application of the results to the target population?

Scientists studying the rate of brain development in children were able to recognize the sampling bias in the brain image database. When scientists were able to apply statistical methods to ensure a better representation of socioeconomically diverse samples, they saw a different pattern in the rate of brain development in children. Scientists learned that, in general, children’s brains matured more quickly than they had previously thought. They were able to draw new conclusions about how certain factors, such as family wealth and education, affected the rate at which children’s brains developed. But the scientsits also suggested that they needed to perform additional studies with a deliberately selected group of children to ensure true diversity in the samples.

In this phase, students will review the Science News article “ Biomedical studies are including more female subjects (finally) ” and the NIH Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable , including the “ guidance document .” Students will identify how sex and gender biases may have affected the results of biomedical research before NIH instituted its policy. The students will then work with their group to recommend other policies to minimize biases in biomedical research.

To guide their development of proposed guidelines, students should answer the following questions in their groups.

1. How have sex and gender biases affected the value and application of biomedical research?

Gender and sex biases in biomedical research have diminished the accuracy and quality of research studies and reduced the applicability of results to the entire population. When girls and women are not included in research studies, the responses and therapeutic outcomes of approximately half of the target population for potential therapies remain unknown.

2. Why do you think the NIH created its policy to reduce sex and gender biases?

In the guidance document, the NIH states that “There is a growing recognition that the quality and generalizability of biomedical research depends on the consideration of key biological variables, such as sex.” The document goes on to state that many diseases and conditions affect people of both sexes, and restricting diversity of biological variables, notably sex and gender, undermines the “rigor, transparency, and generalizability of research findings.”

3. What impact has the NIH Policy on Sex as a Biological Variable had on biomedical research?

The NIH’s policy that sex is factored into research designs, analyses and reporting tries to ensure that when developing and funding biomedical research studies, researchers and institutes address potential biases in the planning stages, which helps to reduce or eliminate those biases in the final study. Including females in biomedical research studies helps to ensure that the results of biomedical research are applicable to a larger proportion of the population, expands the therapies available to girls and women and improves their health care outcomes.

4. What other policies do you think the NIH could institute to reduce biases in biomedical research? If you were to recommend one set of additional guidelines for reducing bias in biomedical research, what guidelines would you propose? Why?

Students could suggest that the NIH should have similar policies related to race, gender identity, wealth/economic status and age. Students should identify a category of bias or an underserved segment of the population that they think needs to be addressed in order to improve biomedical research and health outcomes for all people and should recommend guidelines to reduce bias related to that group. Students recommending guidelines related to race might suggest that some populations, such as African Americans, are historically underserved in terms of access to medical services and health care, and they might suggest guidelines to help reduce the disparity. Students might recommend that a certain percentage of each biomedical research project’s sample include patients of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

5. What biases would your suggested policy help eliminate? How would it accomplish that goal?

Students should describe how their proposed policy would address a discrepancy in the application of biomedical research to the entire human population. Race can be considered a biological variable, like sex, and race has been connected to higher or lower incidence of certain characteristics or medical conditions, such as blood types or diabetes, which sometimes affect how the body reponds to infectious agents, drugs, procedures or other therapies. By ensuring that people from diverse racial and ethnic groups are included in biomedical research studies, scientists and medical professionals can provide better medical care to members of those populations.

Class discussion about bias guidelines

Allow each group time to present its proposed bias-reducing guideline to another group and to receive feedback. Then provide groups with time to revise their guidelines, if necessary. Act as a facilitator while students conduct the class discussion. Use this time to assess individual and group progress. Students should demonstrate an understanding of different biases that may affect patient outcomes in biomedical research studies and in practical medical settings. As part of the group discussion, have students answer the following questions.

1. Why is it important to identify and eliminate biases in research and engineering design?

The goal of most scientific research and engineering projects is to improve the quality of life and the depth of understanding of the world we live in. By eliminating biases, we can better serve the entirety of the human population and the planet .

2. Were there any guidelines that were suggested by multiple groups? How do those actions or policies help reduce bias?

Answers will depend on the guidelines developed and recommended by other groups. Groups could suggest policies related to race, gender identity, wealth/economic status and age. Each group should clearly identify how its guidelines are designed to reduce bias and improve the quality of human life.

3. Which guidelines developed by your classmates do you think would most reduce the effects of bias on research results or engineering designs? Support your selection with evidence and scientific reasoning.

Answers will depend on the guidelines developed and recommended by other groups. Students should agree that guidelines that minimize inequities and improve health care outcomes for a larger group are preferred. Guidelines addressing inequities of race and wealth/economic status are likely to expand access to improved medical care for the largest percentage of the population. People who grow up in less economically advantaged settings have specific health issues related to nutrition and their access to clean water, for instance. Ensuring that people from the lowest economic brackets are represented in biomedical research improves their access to medical care and can dramatically change the length and quality of their lives.

Possible extension

Challenge students to honestly evaluate any biases they may have. Encourage them to take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) to identify any implicit biases they may not recognize. Harvard University has an online IAT platform where students can participate in different assessments to identify preferences and biases related to sex and gender, race, religion, age, weight and other factors. You may want to challenge students to take a test before they begin the activity, and then assign students to take a test after completing the activity to see if their preferences have changed. Students can report their results to the class if they want to discuss how awareness affects the expression of bias.

Additional resources

If you want additional resources for the discussion or to provide resources for student groups, check out the links below.

Additional Science News articles:

Even brain images can be biased

Data-driven crime prediction fails to erase human bias

What we can learn from how a doctor’s race can affect Black newborns’ survival

Bias in a common health care algorithm disproportionately hurts black patients

Female rats face sex bias too

There’s no evidence that a single ‘gay gene’ exists

Positive attitudes about aging may pay off in better health

What male bias in the mammoth fossil record says about the animal’s social groups

The man flu struggle might be real, says one researcher

Scientists may work to prevent bias, but they don’t always say so

The Bias Finders

Showdown at Sex Gap

University resources:

Project Implicit (Take an Implicit Association Tests)

Catalogue of Bias

Understanding Health Research

- Research Bias: Definition, Types + Examples

Sometimes, in the cause of carrying out a systematic investigation, the researcher may influence the process intentionally or unknowingly. When this happens, it is termed as research bias, and like every other type of bias , it can alter your findings.

Research bias is one of the dominant reasons for the poor validity of research outcomes. There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to research bias and this simply means that it can happen at any time; if you do not pay adequate attention.

The spontaneity of research bias means you must take care to understand what it is, be able to identify its feature, and ultimately avoid or reduce its occurrence to the barest minimum. In this article, we will show you how to handle bias in research and how to create unbiased research surveys with Formplus.

What is Research Bias?

Research bias happens when the researcher skews the entire process towards a specific research outcome by introducing a systematic error into the sample data. In other words, it is a process where the researcher influences the systematic investigation to arrive at certain outcomes.

When any form of bias is introduced in research, it takes the investigation off-course and deviates it from its true outcomes. Research bias can also happen when the personal choices and preferences of the researcher have undue influence on the study.

For instance, let’s say a religious conservative researcher is conducting a study on the effects of alcohol. If the researcher’s conservative beliefs prompt him or her to create a biased survey or have sampling bias , then this is a case of research bias.

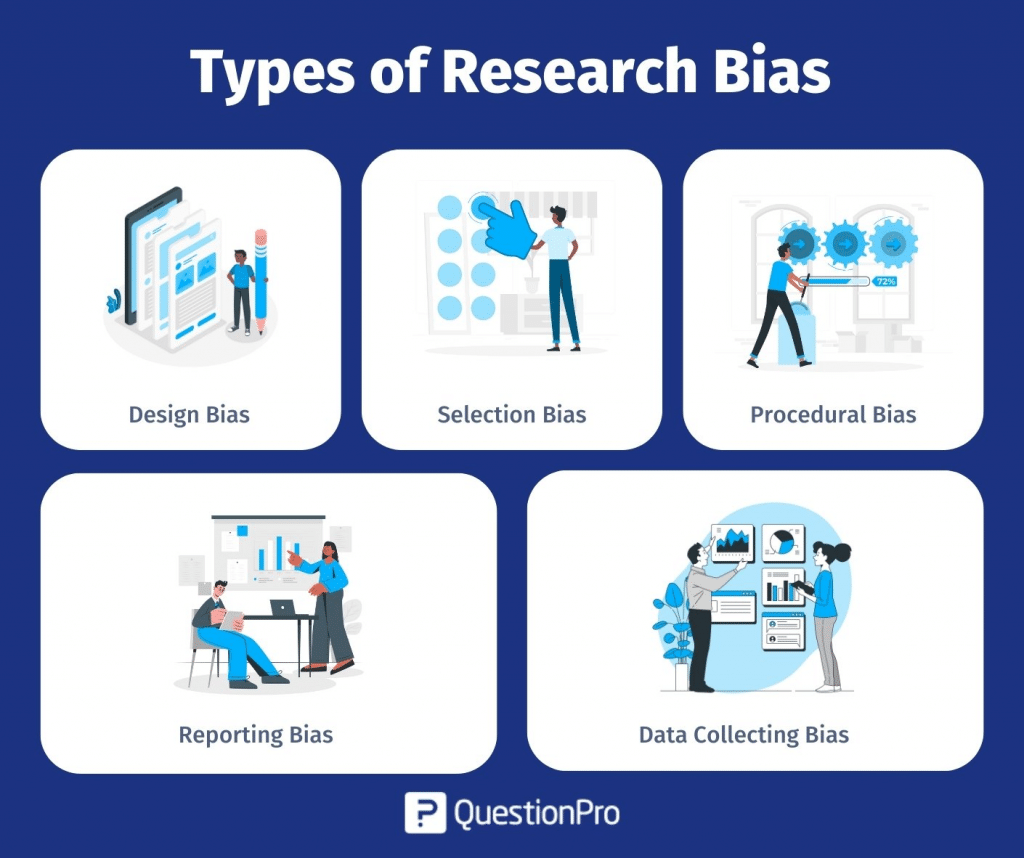

Types of Research Bias

- Design Bias

Design bias has to do with the structure and methods of your research. It happens when the research design, survey questions, and research method is largely influenced by the preferences of the researcher rather than what works best for the research context.

In many instances, poor research design or a pack of synergy between the different contributing variables in your systematic investigation can infuse bias into your research process. Research bias also happens when the personal experiences of the researcher influence the choice of the research question and methodology.

Example of Design Bias

A researcher who is involved in the manufacturing process of a new drug may design a survey with questions that only emphasize the strengths and value of the drug in question.

- Selection or Participant Bias

Selection bias happens when the research criteria and study inclusion method automatically exclude some part of your population from the research process. When you choose research participants that exhibit similar characteristics, you’re more likely to arrive at study outcomes that are uni-dimensional.

Selection bias manifests itself in different ways in the context of research. Inclusion bias is particularly popular in quantitative research and it happens when you select participants to represent your research population while ignoring groups that have alternative experiences.

Examples of Selection Bias

- Administering your survey online; thereby limiting it to internet savvy individuals and excluding members of your population without internet access.

- Collecting data about parenting from a mother’s group. The findings in this type of research will be biased towards mothers while excluding the experiences of the fathers.

- Publication Bias

Peer-reviewed journals and other published academic papers, in many cases, have some degree of bias. This bias is often imposed on them by the publication criteria for research papers in a particular field. Researchers work their papers to meet these criteria and may ignore information or methods that are not in line with them.

For example, research papers in quantitative research are more likely to be published if they contain statistical information. On the other hand, Non-publication in qualitative studies is more likely to occur because of a lack of depth when describing study methodologies and findings are not presented.

- Analysis Bias

This is a type of research bias that creeps in during data processing. Many times, when sorting and analyzing data, the researcher may focus on data samples that confirm his or her thoughts, expectations, or personal experiences; that is, data that favors the research hypothesis.

This means that the researcher, albeit deliberately or unintentionally, ignores data samples that are inconsistent and suggest research outcomes that differ from the hypothesis. Analysis bias can be far-reaching because it alters the research outcomes significantly and provides a false presentation of what is obtainable in the research environment.

Example of Analysis Bias

While researching cannabis, a researcher pays attention to data samples that reinforce the negative effects of cannabis while ignoring data that suggests positives.

- Data Collection Bias

Data collection bias is also known as measurement bias and it happens when the researcher’s personal preferences or beliefs affect how data samples are gathered in the systematic investigation. Data collection bias happens in both q ualitative and quantitative research methods.

In quantitative research, data collection methods can occur when you use a data-gathering tool or method that is not suitable for your research population. For example, asking individuals who do not have access to the internet, to complete a survey via email or your website.

In qualitative research, data collection bias happens when you ask bad survey questions during a semi-structured or unstructured interview . Bad survey questions are questions that nudge the interviewee towards implied assumptions. Leading and loaded questions are common examples of bad survey questions.

- Procedural Bias

Procedural is a type of research bias that happens when the participants in a study are not given enough time to complete surveys. The result is that respondents end up providing half-thoughts and incomplete information that does not provide a true representation of their thoughts.

There are different ways to subject respondents to procedural respondents. For instance, asking respondents to complete a survey quickly to access an incentive, may force them to fill in false information to simply get things over with.

Example of Procedural Bias

- Asking employees to complete an employee feedback survey during break time. This timeframe puts respondents under undue pressure and can affect the validity of their responses.

Bias in Quantitative Research

In quantitative research, the researcher often tries to deny the existence of any bias, by eliminating any type of bias in the systematic investigation. Sampling bias is one of the most types of quantitative research biases and it is concerned with the samples you omit and/or include in your study.

Types of Quantitative Research Bias

Design bias occurs in quantitative research when the research methods or processes alter the outcomes or findings of a systematic investigation. It can occur when the experiment is being conducted or during the analysis of the data to arrive at a valid conclusion.

Many times, design biases result from the failure of the researchers to take into account the likely impact of the bias in the research they conduct. This makes the researcher ignore the needs of the research context and instead, prioritize his or her preferences.

- Sampling Bias

Sampling bias in quantitative research occurs when some members of the research population are systematically excluded from the data sample during research. It also means that some groups in the research population are more likely to be selected in a sample than the others.

Sampling bias in quantitative research mainly occurs in systematic and random sampling. For example, a study about breast cancer that has just male participants can be said to have sampling bias since it excludes the female group in the research population.

Bias in Qualitative Research

In qualitative research, the researcher accepts and acknowledges the bias without trying to deny its existence. This makes it easier for the researcher to clearly define the inherent biases and outline its possible implications while trying to minimize its effects.

Qualitative research defines bias in terms of how valid and reliable the research results are. Bias in qualitative research distorts the research findings and also provides skewed data that defeats the validity and reliability of the systematic investigation.

Types of Bias in Qualitative Research

- Bias from Moderator

The interviewer or moderator in qualitative data collection can impose several biases on the process. The moderator can introduce bias in the research based on his or her disposition, expression, tone, appearance, idiolect, or relation with the research participants.

- Biased Questions

The framing and presentation of the questions during the research process can also lead to bias. Biased questions like leading questions , double- barrelled questions, negative questions, and loaded questions , can influence the way respondents provide answers and the authenticity of the responses they present.

The researcher must identify and eliminate biased questions in qualitative research or rephrase them if they cannot be taken out altogether. Remember that questions form the main basis through which information is collected in research and so, biased questions can lead to invalid research findings.

- Biased Reporting

Biased reporting is yet another challenge in qualitative research. It happens when the research results are altered due to personal beliefs, customs, attitudes, culture, and errors among many other factors. It also means that the researcher must have analyzed the research data based on his/her beliefs rather than the views perceived by the respondents.

Bias in Psychology

Cognitive biases can affect research and outcomes in psychology. For example, during a stop-and-search exercise, law enforcement agents may profile certain appearances and physical dispositions as law-abiding. Due to this cognitive bias, individuals who do not exhibit these outlined behaviors can be wrongly profiled as criminals.

Another example of cognitive bias in psychology can be observed in the classroom. During a class assessment, an invigilator who is looking for physical signs of malpractice might mistakenly classify other behaviors as evidence of malpractice; even though this may not be the case.

Bias in Market Research

There are 5 common biases in market research – social desirability bias, habituation bias, sponsor bias, confirmation bias, and cultural bias. Let’s find out more about them.

- Social desirability bias happens when respondents fill in incorrect information in market research surveys because they want to be accepted or liked. It happens when respondents are seeking social approval and so, fail to communicate how they truly feel about the statement or question being considered.

A good example will be market research to find out preferred sexual enhancement methods for adults. Some persons may not want to admit that they use sexual enhancement drugs to avoid criticism or disapproval.

- Habituation bias happens when respondents give similar answers to questions that are structured in the same way. Lack of variety in survey questions can make respondents lose interest, become non-responsive, and simply regurgitate answers.

For example, multiple-choice questions with the same set of answer options can cause habituation bias in your survey. What you get is that respondents just choose answer options without reflecting on how well their choices represent their thoughts, feelings, and ideas.

- Sponsor bias takes place when respondents have an idea of the brand or organization that is conducting the research. In this case, their perceptions, opinions, experiences, and feelings about the sponsor may influence how they answer the questions about that particular brand.

For example, let’s say Formplus is carrying out a study to find out what the market’s preferred form builder is. Respondents may mention the sponsor for the survey (Formplus) as their preferred form builder out of obligation; especially when the survey has some incentives.

- Confirmation bias happens when the overall research process is aimed at confirming the researcher’s perception or hypothesis about the research subjects. In other words, the research process is merely a formality to reinforce the researcher’s existing beliefs.

Electoral polls often fall into the confirmation bias trap. For example, civil society organizations that are in support of one candidate can create a survey that paints the opposing candidate in a bad light to reinforce beliefs about their preferred candidate.

- Cultural bias arises from the assumptions we have about other cultures based on the values and standards we have for our own culture . For example, when asked to complete a survey about our culture, we may tilt towards positive answers. In the same vein, we are more likely to provide negative responses in a survey for a culture we do not like.

How to Identify Bias in a Research

- Pay attention to research design and methods.

- Observe the data collection process. Does it lean overwhelmingly towards a particular group in the survey population?

- Look out for bad survey questions like loaded questions and negative questions.

- Observe the data sample you have to confirm if it is a fair representation of your research population.

How to Avoid Research Bias

- Gather data from multiple sources: Be sure to collect data samples from the different groups in your research population.

- Verify your data: Before going ahead with the data analysis, try to check in with other data sources, and confirm if you are on the right track.

- If possible, ask research participants to help you review your findings: Ask the people who provided the data whether your interpretations seem to be representative of their beliefs.

- Check for alternative explanations: Try to identify and account for alternative reasons why you may have collected data samples the way you did.

- Ask other members of your team to review your results: Ask others to review your conclusions. This will help you see things that you missed or identify gaps in your argument that need to be addressed.

How to Create Unbiased Research Surveys with Formplus

Formplus has different features that would help you create unbiased research surveys. Follow these easy steps to start creating your Formplus research survey today:

- Go to your Formplus dashboard and click on the “create new form” button. You can access the Formplus dashboard by signing into your Formplus account here.

- After you click on the “create new form” button, you’d be taken to the form builder. This is where you can add different fields into your form and edit them accordingly. Formplus has over 30 form fields that you can simply drag and drop into your survey including rating fields and scales.

- After adding form fields and editing them, save your form to access the builder’s customization features. You can tweak the appearance of your form here by changing the form theme and adding preferred background images to it.

- Copy the form link and share it with respondents.

Conclusion

The first step to dealing with research bias is having a clear idea of what it is and also, being able to identify it in any form. In this article, we’ve shared important information about research bias that would help you identify it easily and work on minimizing its effects to the barest minimum.

Formplus has many features and options that can help you deal with research bias as you create forms and questionnaires for quantitative and qualitative data collection. To take advantage of these, you can sign up for a Formplus account here.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- examples of research bias

- types of research bias

- what is research bias

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Systematic Errors in Research: Definition, Examples

In this article, we are going to explore the types of systematic error, the causes of this error, how to identify, and how to avoid it.

Quota Sampling: Definition, Types, Pros, Cons & Examples

In this article, we’ll explore the concept of quota sampling, its types, and some real-life examples of it can be applied in rsearch

How to do a Meta Analysis: Methodology, Pros & Cons

In this article, we’ll go through the concept of meta-analysis, what it can be used for, and how you can use it to improve how you...

Selection Bias in Research: Types, Examples & Impact

In this article, we’ll discuss the effects of selection bias, how it works, its common effects and the best ways to minimize it.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research bias: What it is, Types & Examples

The researcher sometimes unintentionally or actively affects the process while executing a systematic inquiry. It is known as research bias, and it can affect your results just like any other sort of bias.

When it comes to studying bias, there are no hard and fast guidelines, which simply means that it can occur at any time. Experimental mistakes and a lack of concern for all relevant factors can lead to research bias.

One of the most common causes of study results with low credibility is study bias. Because of its informal nature, you must be cautious when characterizing bias in research. To reduce or prevent its occurrence, you need to be able to recognize its characteristics.

This article will cover what it is, its type, and how to avoid it.

Content Index

What is research bias?

How does research bias affect the research process, types of research bias with examples, how questionpro helps in reducing bias in a research process.

Research bias is a technique in which the researchers conducting the experiment modify the findings to present a specific consequence. It is often known as experimenter bias.

Bias is a characteristic of the research technique that makes it rely on experience and judgment rather than data analysis. The most important thing to know about bias is that it is unavoidable in many fields. Understanding research bias and reducing the effects of biased views is an essential part of any research planning process.

For example, it is much easier to become attracted to a certain point of view when using social research subjects, compromising fairness.

Research bias can majorly affect the research process, weakening its integrity and leading to misleading or erroneous results. Here are some examples of how this bias might affect the research process:

Distorted research design

When bias is present, study results can be skewed or wrong. It can make the study less trustworthy and valid. If bias affects how a study is set up, how data is collected, or how it is analyzed, it can cause systematic mistakes that move the results away from the true or unbiased values.

Invalid conclusions

It can make it hard to believe that the findings of a study are correct. Biased research can lead to unjustified or wrong claims because the results may not reflect reality or give a complete picture of the research question.

Misleading interpretations

Bias can lead to inaccurate interpretations of research findings. It can alter the overall comprehension of the research issue. Researchers may be tempted to interpret the findings in a way that confirms their previous assumptions or expectations, ignoring alternate explanations or contradictory evidence.

Ethical concerns

This bias poses ethical considerations. It can have negative effects on individuals, groups, or society as a whole. Biased research can misinform decision-making processes, leading to ineffective interventions, policies, or therapies.

Damaged credibility

Research bias undermines scientific credibility. Biased research can damage public trust in science. It may reduce reliance on scientific evidence for decision-making.