How to Write Limitations of the Study (with examples)

This blog emphasizes the importance of recognizing and effectively writing about limitations in research. It discusses the types of limitations, their significance, and provides guidelines for writing about them, highlighting their role in advancing scholarly research.

Updated on August 24, 2023

No matter how well thought out, every research endeavor encounters challenges. There is simply no way to predict all possible variances throughout the process.

These uncharted boundaries and abrupt constraints are known as limitations in research . Identifying and acknowledging limitations is crucial for conducting rigorous studies. Limitations provide context and shed light on gaps in the prevailing inquiry and literature.

This article explores the importance of recognizing limitations and discusses how to write them effectively. By interpreting limitations in research and considering prevalent examples, we aim to reframe the perception from shameful mistakes to respectable revelations.

What are limitations in research?

In the clearest terms, research limitations are the practical or theoretical shortcomings of a study that are often outside of the researcher’s control . While these weaknesses limit the generalizability of a study’s conclusions, they also present a foundation for future research.

Sometimes limitations arise from tangible circumstances like time and funding constraints, or equipment and participant availability. Other times the rationale is more obscure and buried within the research design. Common types of limitations and their ramifications include:

- Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study.

- Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data.

- Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data.

- Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of the findings.

- Ethical: limits the access, consent, or confidentiality of the data.

Regardless of how, when, or why they arise, limitations are a natural part of the research process and should never be ignored . Like all other aspects, they are vital in their own purpose.

Why is identifying limitations important?

Whether to seek acceptance or avoid struggle, humans often instinctively hide flaws and mistakes. Merging this thought process into research by attempting to hide limitations, however, is a bad idea. It has the potential to negate the validity of outcomes and damage the reputation of scholars.

By identifying and addressing limitations throughout a project, researchers strengthen their arguments and curtail the chance of peer censure based on overlooked mistakes. Pointing out these flaws shows an understanding of variable limits and a scrupulous research process.

Showing awareness of and taking responsibility for a project’s boundaries and challenges validates the integrity and transparency of a researcher. It further demonstrates the researchers understand the applicable literature and have thoroughly evaluated their chosen research methods.

Presenting limitations also benefits the readers by providing context for research findings. It guides them to interpret the project’s conclusions only within the scope of very specific conditions. By allowing for an appropriate generalization of the findings that is accurately confined by research boundaries and is not too broad, limitations boost a study’s credibility .

Limitations are true assets to the research process. They highlight opportunities for future research. When researchers identify the limitations of their particular approach to a study question, they enable precise transferability and improve chances for reproducibility.

Simply stating a project’s limitations is not adequate for spurring further research, though. To spark the interest of other researchers, these acknowledgements must come with thorough explanations regarding how the limitations affected the current study and how they can potentially be overcome with amended methods.

How to write limitations

Typically, the information about a study’s limitations is situated either at the beginning of the discussion section to provide context for readers or at the conclusion of the discussion section to acknowledge the need for further research. However, it varies depending upon the target journal or publication guidelines.

Don’t hide your limitations

It is also important to not bury a limitation in the body of the paper unless it has a unique connection to a topic in that section. If so, it needs to be reiterated with the other limitations or at the conclusion of the discussion section. Wherever it is included in the manuscript, ensure that the limitations section is prominently positioned and clearly introduced.

While maintaining transparency by disclosing limitations means taking a comprehensive approach, it is not necessary to discuss everything that could have potentially gone wrong during the research study. If there is no commitment to investigation in the introduction, it is unnecessary to consider the issue a limitation to the research. Wholly consider the term ‘limitations’ and ask, “Did it significantly change or limit the possible outcomes?” Then, qualify the occurrence as either a limitation to include in the current manuscript or as an idea to note for other projects.

Writing limitations

Once the limitations are concretely identified and it is decided where they will be included in the paper, researchers are ready for the writing task. Including only what is pertinent, keeping explanations detailed but concise, and employing the following guidelines is key for crafting valuable limitations:

1) Identify and describe the limitations : Clearly introduce the limitation by classifying its form and specifying its origin. For example:

- An unintentional bias encountered during data collection

- An intentional use of unplanned post-hoc data analysis

2) Explain the implications : Describe how the limitation potentially influences the study’s findings and how the validity and generalizability are subsequently impacted. Provide examples and evidence to support claims of the limitations’ effects without making excuses or exaggerating their impact. Overall, be transparent and objective in presenting the limitations, without undermining the significance of the research.

3) Provide alternative approaches for future studies : Offer specific suggestions for potential improvements or avenues for further investigation. Demonstrate a proactive approach by encouraging future research that addresses the identified gaps and, therefore, expands the knowledge base.

Whether presenting limitations as an individual section within the manuscript or as a subtopic in the discussion area, authors should use clear headings and straightforward language to facilitate readability. There is no need to complicate limitations with jargon, computations, or complex datasets.

Examples of common limitations

Limitations are generally grouped into two categories , methodology and research process .

Methodology limitations

Methodology may include limitations due to:

- Sample size

- Lack of available or reliable data

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic

- Measure used to collect the data

- Self-reported data

The researcher is addressing how the large sample size requires a reassessment of the measures used to collect and analyze the data.

Research process limitations

Limitations during the research process may arise from:

- Access to information

- Longitudinal effects

- Cultural and other biases

- Language fluency

- Time constraints

The author is pointing out that the model’s estimates are based on potentially biased observational studies.

Final thoughts

Successfully proving theories and touting great achievements are only two very narrow goals of scholarly research. The true passion and greatest efforts of researchers comes more in the form of confronting assumptions and exploring the obscure.

In many ways, recognizing and sharing the limitations of a research study both allows for and encourages this type of discovery that continuously pushes research forward. By using limitations to provide a transparent account of the project's boundaries and to contextualize the findings, researchers pave the way for even more robust and impactful research in the future.

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Print this article

Limited by our limitations

- Nikki L. Bibler Zaidi

- Nikki L. Bibler Zaidi , Medical School, University of Michigan, United States

Study limitations represent weaknesses within a research design that may influence outcomes and conclusions of the research. Researchers have an obligation to the academic community to present complete and honest limitations of a presented study. Too often, authors use generic descriptions to describe study limitations. Including redundant or irrelevant limitations is an ineffective use of the already limited word count. A meaningful presentation of study limitations should describe the potential limitation, explain the implication of the limitation, provide possible alternative approaches, and describe steps taken to mitigate the limitation. This includes placing research findings within their proper context to ensure readers do not overemphasize or minimize findings. A more complete presentation will enrich the readers’ understanding of the study’s limitations and support future investigation.

- Page/Article: 261-264

- DOI: 10.1007/S40037-019-00530-X

- Peer Reviewed

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

How to present limitations in research

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Limitations don’t invalidate or diminish your results, but it’s best to acknowledge them. This will enable you to address any questions your study failed to answer because of them.

In this guide, learn how to recognize, present, and overcome limitations in research.

- What is a research limitation?

Research limitations are weaknesses in your research design or execution that may have impacted outcomes and conclusions. Uncovering limitations doesn’t necessarily indicate poor research design—it just means you encountered challenges you couldn’t have anticipated that limited your research efforts.

Does basic research have limitations?

Basic research aims to provide more information about your research topic. It requires the same standard research methodology and data collection efforts as any other research type, and it can also have limitations.

- Common research limitations

Researchers encounter common limitations when embarking on a study. Limitations can occur in relation to the methods you apply or the research process you design. They could also be connected to you as the researcher.

Methodology limitations

Not having access to data or reliable information can impact the methods used to facilitate your research. A lack of data or reliability may limit the parameters of your study area and the extent of your exploration.

Your sample size may also be affected because you won’t have any direction on how big or small it should be and who or what you should include. Having too few participants won’t adequately represent the population or groups of people needed to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research process limitations

The study’s design can impose constraints on the process. For example, as you’re conducting the research, issues may arise that don’t conform to the data collection methodology you developed. You may not realize until well into the process that you should have incorporated more specific questions or comprehensive experiments to generate the data you need to have confidence in your results.

Constraints on resources can also have an impact. Being limited on participants or participation incentives may limit your sample sizes. Insufficient tools, equipment, and materials to conduct a thorough study may also be a factor.

Common researcher limitations

Here are some of the common researcher limitations you may encounter:

Time: some research areas require multi-year longitudinal approaches, but you might not be able to dedicate that much time. Imagine you want to measure how much memory a person loses as they age. This may involve conducting multiple tests on a sample of participants over 20–30 years, which may be impossible.

Bias: researchers can consciously or unconsciously apply bias to their research. Biases can contribute to relying on research sources and methodologies that will only support your beliefs about the research you’re embarking on. You might also omit relevant issues or participants from the scope of your study because of your biases.

Limited access to data : you may need to pay to access specific databases or journals that would be helpful to your research process. You might also need to gain information from certain people or organizations but have limited access to them. These cases require readjusting your process and explaining why your findings are still reliable.

- Why is it important to identify limitations?

Identifying limitations adds credibility to research and provides a deeper understanding of how you arrived at your conclusions.

Constraints may have prevented you from collecting specific data or information you hoped would prove or disprove your hypothesis or provide a more comprehensive understanding of your research topic.

However, identifying the limitations contributing to your conclusions can inspire further research efforts that help gather more substantial information and data.

- Where to put limitations in a research paper

A research paper is broken up into different sections that appear in the following order:

Introduction

Methodology

The discussion portion of your paper explores your findings and puts them in the context of the overall research. Either place research limitations at the beginning of the discussion section before the analysis of your findings or at the end of the section to indicate that further research needs to be pursued.

What not to include in the limitations section

Evidence that doesn’t support your hypothesis is not a limitation, so you shouldn’t include it in the limitation section. Don’t just list limitations and their degree of severity without further explanation.

- How to present limitations

You’ll want to present the limitations of your study in a way that doesn’t diminish the validity of your research and leave the reader wondering if your results and conclusions have been compromised.

Include only the limitations that directly relate to and impact how you addressed your research questions. Following a specific format enables the reader to develop an understanding of the weaknesses within the context of your findings without doubting the quality and integrity of your research.

Identify the limitations specific to your study

You don’t have to identify every possible limitation that might have occurred during your research process. Only identify those that may have influenced the quality of your findings and your ability to answer your research question.

Explain study limitations in detail

This explanation should be the most significant portion of your limitation section.

Link each limitation with an interpretation and appraisal of their impact on the study. You’ll have to evaluate and explain whether the error, method, or validity issues influenced the study’s outcome and how.

Propose a direction for future studies and present alternatives

In this section, suggest how researchers can avoid the pitfalls you experienced during your research process.

If an issue with methodology was a limitation, propose alternate methods that may help with a smoother and more conclusive research project. Discuss the pros and cons of your alternate recommendation.

Describe steps taken to minimize each limitation

You probably took steps to try to address or mitigate limitations when you noticed them throughout the course of your research project. Describe these steps in the limitation section.

- Limitation example

“Approaches like stem cell transplantation and vaccination in AD [Alzheimer’s disease] work on a cellular or molecular level in the laboratory. However, translation into clinical settings will remain a challenge for the next decade.”

The authors are saying that even though these methods showed promise in helping people with memory loss when conducted in the lab (in other words, using animal studies), more studies are needed. These may be controlled clinical trials, for example.

However, the short life span of stem cells outside the lab and the vaccination’s severe inflammatory side effects are limitations. Researchers won’t be able to conduct clinical trials until these issues are overcome.

- How to overcome limitations in research

You’ve already started on the road to overcoming limitations in research by acknowledging that they exist. However, you need to ensure readers don’t mistake weaknesses for errors within your research design.

To do this, you’ll need to justify and explain your rationale for the methods, research design, and analysis tools you chose and how you noticed they may have presented limitations.

Your readers need to know that even when limitations presented themselves, you followed best practices and the ethical standards of your field. You didn’t violate any rules and regulations during your research process.

You’ll also want to reinforce the validity of your conclusions and results with multiple sources, methods, and perspectives. This prevents readers from assuming your findings were derived from a single or biased source.

- Learning and improving starts with limitations in research

Dealing with limitations with transparency and integrity helps identify areas for future improvements and developments. It’s a learning process, providing valuable insights into how you can improve methodologies, expand sample sizes, or explore alternate approaches to further support the validity of your findings.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Open access

- Published: 23 February 2012

Discussing study limitations in reports of biomedical studies- the need for more transparency

- Milo A Puhan 1 ,

- Elie A Akl 2 ,

- Dianne Bryant 3 ,

- Feng Xie 4 ,

- Giovanni Apolone 5 &

- Gerben ter Riet 6

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 10 , Article number: 23 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

29k Accesses

29 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Unbiased and frank discussion of study limitations by authors represents a crucial part of the scientific discourse and progress. In today's culture of publishing many authors or scientific teams probably balance 'utter honesty' when discussing limitations of their research with the risk of being unable to publish their work. Currently, too few papers in the medical literature frankly discuss how limitations could have affected the study findings and interpretations. The goals of this commentary are to review how limitations are currently acknowledged in the medical literature, to discuss the implications of limitations in biomedical studies, and to make suggestions as to how to openly discuss limitations for scientists submitting their papers to journals. This commentary was developed through discussion and logical arguments by the authors who are doing research in the area of hedging (use of language to express uncertainty) and who have extensive experience as authors and editors of biomedical papers. We strongly encourage authors to report on all potentially important limitations that may have affected the quality and interpretation of the evidence being presented. This will not only benefit science but also offers incentives for authors: If not all important limitations are acknowledged readers and reviewers of scientific articles may perceive that the authors were unaware of them. Authors should take advantage of their content knowledge and familiarity with the study to prevent misinterpretations of the limitations by reviewers and readers. Articles discussing limitations help shape the future research agenda and are likely to be cited because they have informed the design and conduct of future studies. Instead of perceiving acknowledgment of limitations negatively, authors, reviewers and editors should recognize the potential of a frank and unbiased discussion of study limitations that should not jeopardize acceptance of manuscripts.

Introduction

The physicist Richard Feynman argued, during his commencement address at the California Institute of Technology in 1974, that utter honesty must be a cornerstone of scientific integrity. He cautioned researchers from fooling themselves by saying: "We've learned from experience that the truth will come out. Other experimenters will repeat your experiment and find out whether you were wrong or right. Nature's phenomena will agree or they'll disagree with your theory. And, although you may gain some temporary fame and excitement, you will not gain a good reputation as a scientist if you haven't tried to be very careful in this kind of work."[ 1 ]

We think that, in today's culture of publishing biomedical studies, many authors may not want to discuss limitations of their studies because they perceive a transparency threshold beyond which the probability of manuscript acceptance goes down (perhaps even to zero) [ 2 ]. The goals of this commentary are to briefly review how limitations are currently acknowledged in the biomedical literature, to discuss implications of limitations in biomedical studies, and to make suggestions as to how to openly discuss limitations for scientists who submitting their papers to biomedical journals. This commentary was initiated by two of the authors (MP and GtR), who are doing research in the area of hedging (use of language to express uncertainty), and proposed to the editors of Health and Quality of Life Outcomes . All editors supported the idea of writing a commentary on the importance of discussing limitations transparently and four editors (EAA, DB, FX, GA) joined the writing group. This commentary was developed through discussion and logical arguments by the authors who have extensive experience as authors and editors of biomedical papers themselves.

Recognition, acknowledgment and discussion of all potentially important limitations by authors, if presented in an unbiased way, represent a crucial part of the scientific discourse and progress. The advantages of openly discussing limitations are probably long-term and benefit the scientific community and other users of the evidence: A candid discussion of limitations helps readers to correctly interpret the particular study. Conflicting results across studies may be explained by the patterns in limitations. Moreover, frank discussion of limitations informs future studies, which are likely to be of higher quality if they address the limitations of earlier studies. However, while encouraging others to openly discuss limitations of their studies is easy, discussing the limitations of one's own study is more challenging. Researchers usually have their opinion about how to design and execute studies or how to interpret the results and may not agree that some aspects of a study represent, in the view of others, a limitation. Risks of acknowledging limitations and having an open scientific discourse may include, at least in today's culture, eliciting negative comments by peer reviewers, non-acceptance by journals and a potentially negative image as a researcher.

Discussion of limitations in the medical literature

There is some evidence that limitations are not thoroughly discussed in the medical literature. A study using automated key word searching found that only 17% out of 400 papers published in leading medical journals used at least one word referring to limitations [ 3 ]. Not a single article discussed how a limitation could affect the conclusion. In a more detailed assessment of the medical literature, in which two independent reviewers assessed the abstract and discussion sections of 300 medical research papers, published in first and second tier general medical and specialty journals, 73% of all papers were found to acknowledge a median of 3 limitations [ 4 ]. This higher proportion (compared to the first study) is likely due to a more thorough assessment (i.e., by reviewers rather than an automated search) but could also be related to a slightly different selection of papers. The detailed assessment of these 300 papers revealed that 62% of all limitations referred to aspects of internal validity, which could systematically distort the results. Measurement errors, failure to measure important variables and potential confounding were among those acknowledged most frequently. The remaining limitations referred to aspects of applicability of the results to clinical practice (external validity). Differences between the study population and real-world populations were mentioned most frequently as barriers for applying the results in practice. Few authors discussed how the limitations could have affected the interpretation of study findings.

What is currently unclear is whether authors do or do not address those limitations that are most likely to affect internal validity and applicability of results in real practice. It may well be possible that authors discuss limitations because it is required by journal policies and worry that too open discussion jeopardizes the chances of acceptance. Also, more research is needed to see how the acknowledgment of potentially important limitations fits with the claims made in an article, for example about the effectiveness of a medical intervention or about the measurement properties of a patient-reported outcome.

It is time to discuss limitations not in isolation but in the context of the entire article and as part of a rhetorical-epistemic phenomenon that linguists call "hedging." Hedging refers to "the means by which writers can present a proposition as an opinion rather than a fact" [ 5 ]. By using hedging authors can express the extent of uncertainty about the importance and validity of their study but also prevent readers from making false accusations for strong or definitive statements. Of note, hedging has both positive and negative connotations since it can be used to set an appropriate tone but also to express an opinion that may not be fully supported by the facts.

Discussing implications of limitations prevents misunderstandings and supports interpretation of data

It requires a great deal of judgment to estimate the potential impact of limitations on internal or external validity of a study. Sometimes, the direction of bias may be towards an over- or underestimation of effects. For example, if there is systematic measurement error that equally affects different study groups (so called non-differential measurement error, for example if the exposure is measured with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 90%) the results are usually biased towards an underestimation of the effect [ 6 ]. Or, if a confounder is positively associated with the outcome and more prevalent in study participants exposed to the risk factor of interest, an overestimation of the effect can be expected. Some biases, for example selection bias and some forms of measurement error can, affect the results in a direction that is difficult to predict [ 6 ]. Sometimes, the impact of biases on internal validity may be so small that its description may not be warranted.

Very often the authors of an article are in the best position to judge the direction of a potential bias because they executed the study and have experienced first-hand limitations of their study. In addition, they often have the needed content knowledge that would inform the direction and potential extent of bias. Thus authors should acknowledge recognized limitations and discuss their likely implications on the interpretations of the findings; by doing so, they reduce the probability that readers will misjudge the validity and impact of their study. Of course, it is important that the authors also include the reasoning behind their judgment of the magnitude and direction of the potential bias to enable readers to form their own opinion on the impact of limitations.

For some limitations, however, the impact can better be judged in a meta-epidemiological context, that is, when all studies addressing the same research questions are analyzed together. Some journals ask authors to discuss their results in reference to an existing systematic review [ 7 ]. Thereby, not only heterogeneity of results across studies can be detected but it may be possible to estimate how much a limitation may affect the results. For example, a randomized trial may use a generic health-related quality of life instrument to evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment. The trial may show no effect and have high internal validity. However, other trials evaluating the same treatment may have used a disease-specific instrument and shown an effect that exceeded the minimal important difference. Or, studies may have shown that disease-specific instruments discriminate better between disease severity or change over time than generic instruments [ 8 , 9 ]. The limitation of the first trial that used a much less responsive generic instrument only becomes much clearer in a meta-epidemiological context. Another important purpose of systematic reviews is to identify limitations of existing studies and to help investigators to avoid them in the future. It is beyond the scope of this commentary to discuss different types of biases and their implications for the quality of evidence but we refer readers to the extensive literature on biases and to some approaches that are currently used to judge the implications of limitations on the strength of evidence [ 6 , 10 – 12 ].

An open discussion of limitations should not jeopardize paper acceptance by journals

We would like to strongly encourage authors submitting their articles to biomedical journals to openly discuss all potentially relevant limitations of their study. Specifically, we suggest including text in the abstract and discussion section (Table 1 ):

At the end of the results section add one sentence highlighting the one or two main limitations of the study. The conclusion section should reflect the seriousness of the limitations as perceived by the authors and their potential impact on the results and interpretation of the study.

Discussion section

Report on all limitations that may have affected the quality of the evidence being presented, including aspects of study design and implementation. Readers depend on a candid communication by the authors and may get the impression that the investigators were naive if they are not reported. If space is limited an online appendix could be considered that describes the limitations as well as their potential implications in more details.

Give the authors' view on how the limitations impact on the quality of the evidence and discuss the direction and magnitude of bias. For example, a recent study reporting on the association of quality of life of elderly people with nursing home placement and death discussed the potential mechanism of a selection bias by economic status. The authors concluded that a selection bias based on economic status was unlikely because access to health care, and thus selection into the study, did not depend on economic status [ 13 ]. As explained above, few authors currently discuss how limitations could have affected the strength of the conclusions that may be drawn. However, the authors should take advantage of their content knowledge and familiarity with the study and the meta-epidemiological context to prevent misinterpretations of the limitations by reviewers and readers.

Do not restrict the discussion of limitations to aspects of internal validity. For readers, it is important to learn about potential barriers for applying the evidence, generated in scientific studies, to practice. Discuss where the limits of applicability of the results may lie. This requires a discussion of the setting in which the study took place, how and why the results may differ in another setting (potential effect modification) and what barriers may exist to adopt new interventions or diagnostic procedures in a setting that is different from the research setting [ 14 ].

Discuss the strengths of the study that may counterbalance or outweigh (some of) the limitations. Be explicit about the strengths, in particular how the study was implemented, and do not limit the discussion of strengths to general statements about study design.

Provide suggestions for future research specifically overcoming the limitations of the current study. One may also consider describing how one's own study could be repeated and conducted differently to avoid some of the limitations. Articles acknowledging and putting into context all potentially relevant limitations could help shape the research agenda and may be more likely to be cited because they inform the design and conduct of future studies.

We acknowledge that, even if limitations are openly discussed, some articles will be rejected by journals because the limitations affect an article's validity, level of interest to the reader and comprehensibility too much as assessed by peer reviewers. But we believe that journal editors should consider the thoroughness with which limitations are discussed in their editorial decisions on acceptance. In fact, editors should consider it a shortcoming of the submission if a candid discussion is lacking. To end with Feynman's words, "[...] if you are doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid - not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you've eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked - to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated."[ 1 ]

Feynman RP: Cargo Cult Science. Eng Sci 1974, 37(7):10–13.

Google Scholar

Montori VM, Jaeschke R, Schunemann HJ, Bhandari M, Brozek JL, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH: Users' guide to detecting misleading claims in clinical research reports. BMJ 2004, 329(7474):1093–1096. 10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1093

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Ioannidis JP: Limitations are not properly acknowledged in the scientific literature. J Clin Epidemiol 2007, 60(4):324–329. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.011

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Puhan MA, Heller N, Joleska I, Siebeling L, Muggensturm P, Umbehr M, Goodman S, ter Riet G: Acknowledging Limitations in Biomedical Studies: The ALIBI Study. In The Sixth International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication . Vancouver, Canada: JAMA and BMJ; 2009.

Hyland K: Hedging in scientific research articles . Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publication Company; 1998.

Book Google Scholar

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL: Modern Epidemiology . 3rd edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Clark S, Horton R: Putting research into context--revisited. Lancet 2010, 376(9734):10–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61001-X

Puhan MA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein R, Mador J, McKim D, Stahl E, Griffith L, Schunemann HJ: Relative responsiveness of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire, St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire and four other health-related quality of life instruments for patients with chronic lung disease. Respir Med 2007, 101(2):308–316. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.04.023

Teckle P, Peacock S, McTaggart-Cowan H, van der Hoek K, Chia S, Melosky B, Gelmon K: The ability of cancer-specific and generic preference-based instruments to discriminate across clinical and self-reported measures of cancer severities. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 106. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-106

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ: What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008, 336(7651):995–998. 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ: GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336(7650):924–926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Haynes RB, Sackett D, Tugwell P, Guyatt GH: Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research. 3rd edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Bilotta C, Bowling A, Nicolini P, Case A, Pina G, Rossi SV, Vergani C: Older People's Quality of Life (OPQOL) scores and adverse health outcomes at a one-year follow-up. A prospective cohort study on older outpatients living in the community in Italy. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 72. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-72

Bausewein C, Simon ST, Benalia H, Downing J, Mwangi-Powell FN, Daveson BA, Harding R, Higginson IJ: Implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in palliative care--users' cry for help. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 27. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-27

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 North Wolfe Street, Mail room E6153, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Milo A Puhan

Department of Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

Dianne Bryant

Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

Scientific Directorate, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova, IRCCS, Reggio Emilia, Italy

Giovanni Apolone

Department of General Practice, Academic Medical Center University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Gerben ter Riet

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Milo A Puhan .

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Puhan, M.A., Akl, E.A., Bryant, D. et al. Discussing study limitations in reports of biomedical studies- the need for more transparency. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10 , 23 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-23

Download citation

Received : 15 March 2011

Accepted : 23 February 2012

Published : 23 February 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-23

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical Literature

- Content Knowledge

- Internal Validity

- Minimal Important Difference

- Scientific Discourse

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

ISSN: 1477-7525

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Limitations of the Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research. Study limitations are the constraints placed on the ability to generalize from the results, to further describe applications to practice, and/or related to the utility of findings that are the result of the ways in which you initially chose to design the study or the method used to establish internal and external validity or the result of unanticipated challenges that emerged during the study.

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Theofanidis, Dimitrios and Antigoni Fountouki. "Limitations and Delimitations in the Research Process." Perioperative Nursing 7 (September-December 2018): 155-163. .

Importance of...

Always acknowledge a study's limitations. It is far better that you identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor and have your grade lowered because you appeared to have ignored them or didn't realize they existed.

Keep in mind that acknowledgment of a study's limitations is an opportunity to make suggestions for further research. If you do connect your study's limitations to suggestions for further research, be sure to explain the ways in which these unanswered questions may become more focused because of your study.

Acknowledgment of a study's limitations also provides you with opportunities to demonstrate that you have thought critically about the research problem, understood the relevant literature published about it, and correctly assessed the methods chosen for studying the problem. A key objective of the research process is not only discovering new knowledge but also to confront assumptions and explore what we don't know.

Claiming limitations is a subjective process because you must evaluate the impact of those limitations . Don't just list key weaknesses and the magnitude of a study's limitations. To do so diminishes the validity of your research because it leaves the reader wondering whether, or in what ways, limitation(s) in your study may have impacted the results and conclusions. Limitations require a critical, overall appraisal and interpretation of their impact. You should answer the question: do these problems with errors, methods, validity, etc. eventually matter and, if so, to what extent?

Price, James H. and Judy Murnan. “Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them.” American Journal of Health Education 35 (2004): 66-67; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com.

Descriptions of Possible Limitations

All studies have limitations . However, it is important that you restrict your discussion to limitations related to the research problem under investigation. For example, if a meta-analysis of existing literature is not a stated purpose of your research, it should not be discussed as a limitation. Do not apologize for not addressing issues that you did not promise to investigate in the introduction of your paper.

Here are examples of limitations related to methodology and the research process you may need to describe and discuss how they possibly impacted your results. Note that descriptions of limitations should be stated in the past tense because they were discovered after you completed your research.

Possible Methodological Limitations

- Sample size -- the number of the units of analysis you use in your study is dictated by the type of research problem you are investigating. Note that, if your sample size is too small, it will be difficult to find significant relationships from the data, as statistical tests normally require a larger sample size to ensure a representative distribution of the population and to be considered representative of groups of people to whom results will be generalized or transferred. Note that sample size is generally less relevant in qualitative research if explained in the context of the research problem.

- Lack of available and/or reliable data -- a lack of data or of reliable data will likely require you to limit the scope of your analysis, the size of your sample, or it can be a significant obstacle in finding a trend and a meaningful relationship. You need to not only describe these limitations but provide cogent reasons why you believe data is missing or is unreliable. However, don’t just throw up your hands in frustration; use this as an opportunity to describe a need for future research based on designing a different method for gathering data.

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic -- citing prior research studies forms the basis of your literature review and helps lay a foundation for understanding the research problem you are investigating. Depending on the currency or scope of your research topic, there may be little, if any, prior research on your topic. Before assuming this to be true, though, consult with a librarian! In cases when a librarian has confirmed that there is little or no prior research, you may be required to develop an entirely new research typology [for example, using an exploratory rather than an explanatory research design ]. Note again that discovering a limitation can serve as an important opportunity to identify new gaps in the literature and to describe the need for further research.

- Measure used to collect the data -- sometimes it is the case that, after completing your interpretation of the findings, you discover that the way in which you gathered data inhibited your ability to conduct a thorough analysis of the results. For example, you regret not including a specific question in a survey that, in retrospect, could have helped address a particular issue that emerged later in the study. Acknowledge the deficiency by stating a need for future researchers to revise the specific method for gathering data.

- Self-reported data -- whether you are relying on pre-existing data or you are conducting a qualitative research study and gathering the data yourself, self-reported data is limited by the fact that it rarely can be independently verified. In other words, you have to the accuracy of what people say, whether in interviews, focus groups, or on questionnaires, at face value. However, self-reported data can contain several potential sources of bias that you should be alert to and note as limitations. These biases become apparent if they are incongruent with data from other sources. These are: (1) selective memory [remembering or not remembering experiences or events that occurred at some point in the past]; (2) telescoping [recalling events that occurred at one time as if they occurred at another time]; (3) attribution [the act of attributing positive events and outcomes to one's own agency, but attributing negative events and outcomes to external forces]; and, (4) exaggeration [the act of representing outcomes or embellishing events as more significant than is actually suggested from other data].

Possible Limitations of the Researcher

- Access -- if your study depends on having access to people, organizations, data, or documents and, for whatever reason, access is denied or limited in some way, the reasons for this needs to be described. Also, include an explanation why being denied or limited access did not prevent you from following through on your study.

- Longitudinal effects -- unlike your professor, who can literally devote years [even a lifetime] to studying a single topic, the time available to investigate a research problem and to measure change or stability over time is constrained by the due date of your assignment. Be sure to choose a research problem that does not require an excessive amount of time to complete the literature review, apply the methodology, and gather and interpret the results. If you're unsure whether you can complete your research within the confines of the assignment's due date, talk to your professor.

- Cultural and other type of bias -- we all have biases, whether we are conscience of them or not. Bias is when a person, place, event, or thing is viewed or shown in a consistently inaccurate way. Bias is usually negative, though one can have a positive bias as well, especially if that bias reflects your reliance on research that only support your hypothesis. When proof-reading your paper, be especially critical in reviewing how you have stated a problem, selected the data to be studied, what may have been omitted, the manner in which you have ordered events, people, or places, how you have chosen to represent a person, place, or thing, to name a phenomenon, or to use possible words with a positive or negative connotation. NOTE : If you detect bias in prior research, it must be acknowledged and you should explain what measures were taken to avoid perpetuating that bias. For example, if a previous study only used boys to examine how music education supports effective math skills, describe how your research expands the study to include girls.

- Fluency in a language -- if your research focuses , for example, on measuring the perceived value of after-school tutoring among Mexican-American ESL [English as a Second Language] students and you are not fluent in Spanish, you are limited in being able to read and interpret Spanish language research studies on the topic or to speak with these students in their primary language. This deficiency should be acknowledged.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Senunyeme, Emmanuel K. Business Research Methods. Powerpoint Presentation. Regent University of Science and Technology; ter Riet, Gerben et al. “All That Glitters Isn't Gold: A Survey on Acknowledgment of Limitations in Biomedical Studies.” PLOS One 8 (November 2013): 1-6.

Structure and Writing Style

Information about the limitations of your study are generally placed either at the beginning of the discussion section of your paper so the reader knows and understands the limitations before reading the rest of your analysis of the findings, or, the limitations are outlined at the conclusion of the discussion section as an acknowledgement of the need for further study. Statements about a study's limitations should not be buried in the body [middle] of the discussion section unless a limitation is specific to something covered in that part of the paper. If this is the case, though, the limitation should be reiterated at the conclusion of the section.

If you determine that your study is seriously flawed due to important limitations , such as, an inability to acquire critical data, consider reframing it as an exploratory study intended to lay the groundwork for a more complete research study in the future. Be sure, though, to specifically explain the ways that these flaws can be successfully overcome in a new study.

But, do not use this as an excuse for not developing a thorough research paper! Review the tab in this guide for developing a research topic . If serious limitations exist, it generally indicates a likelihood that your research problem is too narrowly defined or that the issue or event under study is too recent and, thus, very little research has been written about it. If serious limitations do emerge, consult with your professor about possible ways to overcome them or how to revise your study.

When discussing the limitations of your research, be sure to:

- Describe each limitation in detailed but concise terms;

- Explain why each limitation exists;

- Provide the reasons why each limitation could not be overcome using the method(s) chosen to acquire or gather the data [cite to other studies that had similar problems when possible];

- Assess the impact of each limitation in relation to the overall findings and conclusions of your study; and,

- If appropriate, describe how these limitations could point to the need for further research.

Remember that the method you chose may be the source of a significant limitation that has emerged during your interpretation of the results [for example, you didn't interview a group of people that you later wish you had]. If this is the case, don't panic. Acknowledge it, and explain how applying a different or more robust methodology might address the research problem more effectively in a future study. A underlying goal of scholarly research is not only to show what works, but to demonstrate what doesn't work or what needs further clarification.

Aguinis, Hermam and Jeffrey R. Edwards. “Methodological Wishes for the Next Decade and How to Make Wishes Come True.” Journal of Management Studies 51 (January 2014): 143-174; Brutus, Stéphane et al. "Self-Reported Limitations and Future Directions in Scholarly Reports: Analysis and Recommendations." Journal of Management 39 (January 2013): 48-75; Ioannidis, John P.A. "Limitations are not Properly Acknowledged in the Scientific Literature." Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60 (2007): 324-329; Pasek, Josh. Writing the Empirical Social Science Research Paper: A Guide for the Perplexed. January 24, 2012. Academia.edu; Structure: How to Structure the Research Limitations Section of Your Dissertation. Dissertations and Theses: An Online Textbook. Laerd.com; What Is an Academic Paper? Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Writing Tip

Don't Inflate the Importance of Your Findings!

After all the hard work and long hours devoted to writing your research paper, it is easy to get carried away with attributing unwarranted importance to what you’ve done. We all want our academic work to be viewed as excellent and worthy of a good grade, but it is important that you understand and openly acknowledge the limitations of your study. Inflating the importance of your study's findings could be perceived by your readers as an attempt hide its flaws or encourage a biased interpretation of the results. A small measure of humility goes a long way!

Another Writing Tip

Negative Results are Not a Limitation!

Negative evidence refers to findings that unexpectedly challenge rather than support your hypothesis. If you didn't get the results you anticipated, it may mean your hypothesis was incorrect and needs to be reformulated. Or, perhaps you have stumbled onto something unexpected that warrants further study. Moreover, the absence of an effect may be very telling in many situations, particularly in experimental research designs. In any case, your results may very well be of importance to others even though they did not support your hypothesis. Do not fall into the trap of thinking that results contrary to what you expected is a limitation to your study. If you carried out the research well, they are simply your results and only require additional interpretation.

Lewis, George H. and Jonathan F. Lewis. “The Dog in the Night-Time: Negative Evidence in Social Research.” The British Journal of Sociology 31 (December 1980): 544-558.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Sample Size Limitations in Qualitative Research

Sample sizes are typically smaller in qualitative research because, as the study goes on, acquiring more data does not necessarily lead to more information. This is because one occurrence of a piece of data, or a code, is all that is necessary to ensure that it becomes part of the analysis framework. However, it remains true that sample sizes that are too small cannot adequately support claims of having achieved valid conclusions and sample sizes that are too large do not permit the deep, naturalistic, and inductive analysis that defines qualitative inquiry. Determining adequate sample size in qualitative research is ultimately a matter of judgment and experience in evaluating the quality of the information collected against the uses to which it will be applied and the particular research method and purposeful sampling strategy employed. If the sample size is found to be a limitation, it may reflect your judgment about the methodological technique chosen [e.g., single life history study versus focus group interviews] rather than the number of respondents used.

Boddy, Clive Roland. "Sample Size for Qualitative Research." Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 19 (2016): 426-432; Huberman, A. Michael and Matthew B. Miles. "Data Management and Analysis Methods." In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 428-444; Blaikie, Norman. "Confounding Issues Related to Determining Sample Size in Qualitative Research." International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (2018): 635-641; Oppong, Steward Harrison. "The Problem of Sampling in qualitative Research." Asian Journal of Management Sciences and Education 2 (2013): 202-210.

- << Previous: 8. The Discussion

- Next: 9. The Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2019

Impact of peer review on discussion of study limitations and strength of claims in randomized trial reports: a before and after study

- Kerem Keserlioglu 1 ,

- Halil Kilicoglu 2 &

- Gerben ter Riet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2231-7637 3 , 4

Research Integrity and Peer Review volume 4 , Article number: 19 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

8437 Accesses

2 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

In their research reports, scientists are expected to discuss limitations that their studies have. Previous research showed that often, such discussion is absent. Also, many journals emphasize the importance of avoiding overstatement of claims. We wanted to see to what extent editorial handling and peer review affects self-acknowledgment of limitations and hedging of claims.

Using software that automatically detects limitation-acknowledging sentences and calculates the level of hedging in sentences, we compared the submitted manuscripts and their ultimate publications of all randomized trials published in 2015 in 27 BioMed Central (BMC) journals and BMJ Open. We used mixed linear and logistic regression models, accounting for clustering of manuscript-publication pairs within journals, to quantify before-after changes in the mean numbers of limitation-acknowledging sentences, in the probability that a manuscript with zero self-acknowledged limitations ended up as a publication with at least one and in hedging scores.

Four hundred forty-six manuscript-publication pairs were analyzed. The median number of manuscripts per journal was 10.5 (interquartile range 6–18). The average number of distinct limitation sentences increased by 1.39 (95% CI 1.09–1.76), from 2.48 in manuscripts to 3.87 in publications. Two hundred two manuscripts (45.3%) did not mention any limitations. Sixty-three (31%, 95% CI 25–38) of these mentioned at least one after peer review. Changes in mean hedging scores were negligible.

Conclusions

Our findings support the idea that editorial handling and peer review lead to more self-acknowledgment of study limitations, but not to changes in linguistic nuance.

Peer Review reports

One of the main functions of the editorial process (peer review and editorial handling) as employed by almost all serious scientific journals is to ensure that the research articles published are accurate, transparent, and complete reports of the research conducted. Spin is a term used to describe reporting practices that distort the interpretation of a study’s results [ 1 ] . Not mentioning (all important) study limitations is one way in which readers can be misguided into believing that, for example, the beneficial effect of an experimental treatment is greater than the trial’s result warrant.

In a survey among scientists, insufficient reporting of study limitations ranked high in a list of detrimental research practices [ 2 ]. In a masked before-after study at the editorial offices of Annals of Internal Medicine, Goodman et al. found that the reporting of study limitations was fairly poor in manuscripts but improved after peer review and editing [ 3 ]. Ter Riet et al. demonstrated that more than a quarter of biomedical research articles do not mention any limitations [ 4 ]. And finally, Horton, in a survey among all authors of ten Lancet papers, found that “Important weaknesses were often admitted on direct questioning, but were not included in the published article” [ 5 ]. Other forms of spin are inappropriate extrapolation of results and inferring causal relationships when the study’s design does not allow for it [ 1 ].

Peer reviewers should spot and suggest changes to overstatements and claims that are too strong and point out non-trivial study weaknesses that are not mentioned. The peer review process may therefore been seen as “a negotiation between authors and journal about the scope of the knowledge claims that will ultimately appear in print” [ 6 ]. Specific words that can be used to add nuance to statements and forestall potential overstatement are so-called “hedges”; these are words like “might,” “could,” “suggest,” “appear,” etc. [ 7 ] Authors of an article are arguably in the best position to point out their study’s weaknesses, but they may feel that naming too many or discussing them too extensively could hurt their chances of publication. In this contribution, we hypothesized that, compared to the subsequent publications, the discussion sections of the submitted manuscripts contain fewer acknowledgments of limitations and are less strongly hedged.

In this study, we considered the discussion sections of randomized clinical trial (RCT) reports published in 27 BioMed Central (BMC) journals and BMJ Open. Using two software tools, we determined the number of sentences dedicated to the acknowledgment of specific study limitations and the use of linguistic hedges, before (manuscripts) and after peer review (publications). The limitation detection tool relies on the structure of the discussion sections and linguistic clues to identify limitation sentences [ 8 ]. In a formal evaluation, its accuracy was found to be 91.5% (95% CI 90.1–92.9). The hedging detection tool uses a lexicon containing 190 weighted hedges. The system computes an overall hedging score based on the number and strength of hedges in a text. Hedge weights range from 1 (low hedging strength, e.g., “largely”) to 5 (high hedging strength, e.g., “may”). The overall hedging score is then divided by the word count of the discussion section (normalization). We also calculated “unweighted” scores, in which all hedges are weighted equally as 1. The software tool yielded 93% accuracy in identifying hedged sentences in a formal evaluation [ 9 ]. The manuscripts were downloaded from the journals’ websites followed by manual pre-processing to restore sentence and paragraph structure. Our software automatically extracted the discussion sections in the publications from PubMed Central.

We also carried out a qualitative analysis of the two publications with the largest increase and decrease of hedging score, respectively. For these two papers, KK compared the before and after discussion sections to see what the actual changes were. The reviewer reports, consisting of the reviewer’s comments and the authors responses, were analyzed.

We performed mixed linear regression analysis, for each manuscript-publication pair, of the mean changes in the number of limitation sentences and normalized hedging scores, with the journal as a random intercept. We repeated these analyses adjusting for the journal’s impact factor (continuous), editorial team size (continuous), and composition of authors in terms of English proficiency (three dummy variables representing four categories). English proficiency was derived from the classification of majority native English-speaking countries by the United Kingdom (UK) government for British citizenship application [ 10 ]. English proficiency was categorized as follows: (i) All authors are residents of an English native country; (ii) the first author is an English native, but at least one co-author is not; (iii) the first author is not an English native, but at least one co-author is; and (iv) none of the authors are English natives. We performed a sensitivity analysis, in which we excluded the manuscript-publication pairs of BMJ Open ( n = 69) and BMC Medicine ( n = 14) due to their exceptional number of editorial team members (84 and 182, respectively). Finally, using scatterplots and fractional polynomial functions, we visually explored if the effect on the changes in the number of limitation-acknowledging sentences was affected by the number of limitation-acknowledging sentences in the manuscript controlled for regression to the mean using a median split as suggested by Goodman et al. [ 3 ]. We present the results of the crude and adjusted analyses in Table 2 and those of the sensitivity analyses in Appendix 1 .

We used mixed-effects logistic regression analysis to assess the impact of the abovementioned factors on the likelihood of mentioning at least one limitation in the publication among those that had none in the manuscript. Sensitivity analyses consisted of restricting the data set to the journals with fewer than 20 editorial team members, at least 10 manuscript-publication pairs, and both of those restrictions simultaneously, respectively.

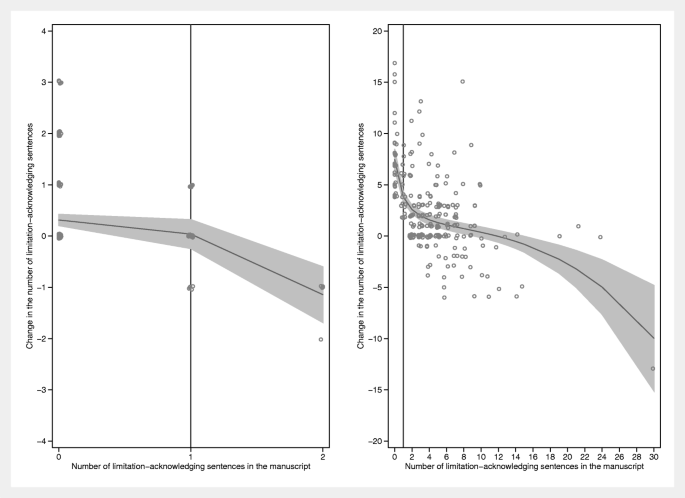

Four hundred forty-six research articles were selected. Table 1 shows a few key journal characteristics. The median number of manuscripts per journal was 10.5 (interquartile range (IQR) 6.5–18.5; range 2–69). Table 2 shows the results. The average number of distinct limitation sentences increased by 1.39, from 2.48 (manuscripts) to 3.87 (publications). Two hundred two manuscripts (45.3%) did not mention any limitations. Sixty-three (31%, 95% CI 25–38) of these mentioned at least one after peer review. Of the 244 manuscripts that mentioned at least one limitation, eight (3%, 95% CI 2–6) mentioned none in the publication. Across the (sensitivity) analyses performed, the probability of mentioning at least one limitation in the publication among those that had none in the manuscript was not consistently associated with any of the three covariables assessed, although higher impact factors tended to be weakly associated with lower probabilities and size of the editorial team weakly with higher probabilities (data not shown). The visual assessment of how the number of changes in the limitation-acknowledging sentences depended on the number of such sentences in the manuscript showed an inverse relation, that is, larger changes were seen in manuscripts with low numbers of limitation-acknowledging sentences (Fig. 1 ).

Changes in the number of limitation-acknowledging sentences between manuscripts and publications as a function of the number such sentences in the manuscript. Left panel: manuscript-publication pairs below the median split. Right panel: manuscript-publication pairs above the median split. The median split was calculated as the average of the number of limitation-acknowledging sentences in the manuscript ( L m ) and in the publication ( L p ): ( L m + L p )/2. These averages were ranked and the median (value = 2; interquartile range 0–5) determined. The lines are fitted using fractional polynomials with 95% confidence intervals (Stata 13.1, twoway fpfitci command). Note that, in both panels, the changes tend to increase with decreasing numbers of limitation-acknowledging sentences in the manuscript. In particular, the effect of peer review and editorial handling is large in those manuscripts above the median split (right panel) with zero limitation-acknowledging sentences in the manuscript. The vertical line in the right panel is the line x = 1. Cluttering of data points was prevented by jittering them. Therefore, data points for x = 0 are not placed exactly above the tick mark for x = 0 but somewhat scattered to the left and right. The same holds for all data points and for the vertical placement of the points

The hedging-related differences were all very close to zero. A post hoc analysis inspired by the hypothesis that limitation-acknowledging sentences themselves might affect the average hedging scores confirmed the main analysis.

The largest increase in hedging score was + 1.67 (from 3.33 to 5.00). The weighted hedging scores were 50 across the 15 detected sentences in the manuscript and 145 across the 29 detected sentences in the published paper, respectively. The largest decrease in hedging score was − 2.55 (from 6.85 to 4.30). The weighted hedging score was 192 across 28 sentences in the manuscript and 142 across 33 sentences in the published paper (see Appendix 3 for the textual changes).

In a sample of 446 randomized trial reports published in 28 open access journals, we found a 56% increase in the number of sentences dedicated to study limitations after peer review, although one may argue that in absolute terms, the gain was modest (1.39 additional sentences). Our automated approach showed that 33% of research reports do not contain limitation sentences after peer review. This is comparable with the finding of 27% by Ter Riet et al., which they determined with a manual approach. Goodman et al. found that mentioning study limitations is one of the poorest scoring items before and one of the most improved factors after peer review [ 3 ]. Like Goodman et al., we found evidence that peer review and editorial handling had greater impact on manuscripts with zero and very low numbers of limitation-acknowledging sentences. In Appendix 2 , we highlight the attention to mentioning study limitations in seven major reporting guidelines.

Our findings do not support the hypothesis that the editorial process increases the qualification of claims by using a more nuanced language. The small-scale qualitative analysis of two manuscript-publication pairs indicated that authors are asked to both tone down statements, that is, hedge more strongly, and make statements less speculative, that is hedge less. These phenomena may offset each other resulting in minimal changes in the overall use of hedges (see Appendix 3 for the actual text changes). While the hedging terms and their strength scores were selected based on a careful analysis of the linguistic literature on this topic, it is possible that authors use terms indicating different degrees of certainty (e.g., could vs. may ) somewhat interchangeably. This may explain our finding that the net change in hedging scores was very small.

To better understand the influence of peer review on changes made to manuscripts before publication, it may be interesting to conduct more extensive qualitative analyses of the peer review reports and correspondence available in the files of editorial boards or publishers. Another interesting research avenue may be the comparison of rejected manuscripts to accepted ones, to assess if acknowledgment of limitations and degree of hedging affects acceptance rates. It may be useful to restrict such analyses to sentences in which particular claims on, for example, generalizability are made.

Arguably, our software tools might be utilized by editorial boards (or submitting authors) to flag up particular paragraphs that might deserve more (editorial) attention. The limitation sentence recognizing software could for example be used to alert editors to manuscripts with zero self-acknowledged limitations to see if such omission can be justified. If reference values existed that represented the range of hedging scores across a large body of papers, the hedge-detection software could help inform reviewers (or even authors) that the manuscript has an unusual (weighted) hedging score and let them revisit some the formulations in the paper. We think that currently, no direct conclusions should be drawn from the numbers alone. Human interpretation will remain critical for some time to come, but a signposting role of the software seems currently feasible.

A limitation of our study is that we only included reports or randomized trials that made it to publications. Acknowledgment of limitations among all submissions, including also observational studies, may be different than what we report here. Another limitation is that we only included open peer review journals of more than average editorial team quality. Blind peer review may lead to different results as may the case for journals with lower quality editorial team. Note also that the weight assigned to the hedges is somewhat subjective. However, our results were stable across weighted and unweighted hedges. Finally, one may argue that there is a discrepancy between our interest in overstated claims and what we actually measured, namely, hedging scores in all sentences in the discussion sections. A stricter operationalization of our objective would have required that we detect “claim sentences” first and then measure hedging levels in those sentences only. On the other hand, our approach to focus on discussion sections only is better than analyzing complete papers, because claims are usually made in the discussion sections. A strength of our study is the automated assessment of limitation sentences and hedges, limiting the likelihood of analytical or observational bias. Such automated assessment could also assist journal editors as well as peer reviewers in their review tasks. Our results suggest that reviewers and/or editors demand discussion of study limitations that authors were unaware of or unwilling to discuss. Since good science implies the full disclosure of issues that may (partially) invalidate the findings of a study, this increase in the number of limitation sentences is a positive effect of the peer and editorial review process.

Our findings support the idea that editorial handling and peer review, on average, cause a modest increase in the number of self-acknowledged study limitations and that these effects are larger in a manuscript reporting zero or very few limitations. This finding is important in the debates about the value of peer review and detrimental research practices. Software tools such as the ones used in this study may be employed by authors, reviewers, and editors to flag potentially problematic manuscripts or sections thereof. More research is needed to assess more precisely the effects, if any, of peer review and editorial handling on linguistic nuance of claims.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study as well as the software tools used for the detection of limitation-acknowledging sentences and hedges are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

BioMed Central

Confidence interval

Interquartile range

Randomized clinical trial

Standard deviation

United Kingdom

Chiu K, Grundy Q, Bero L. ‘Spin’ in published biomedical literature: a methodological systematic review. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(9):e2002173.

Article Google Scholar

Bouter LM, Tijdink J, Axelsen N, Martinson BC, Ter Riet G. Ranking major and minor research misbehaviors: results from a survey among participants of four World Conferences on Research Integrity. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2016;1:17.

Goodman SN, Berlin J, Fletcher SW, Fletcher RH. Manuscript quality before and after peer review and editing at Annals of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(1):11–21.

Ter Riet G, Chesley P, Gross AG, Siebeling L, Muggensturm P, Heller N, et al. All that glitters isn’t gold: a survey on acknowledgement of limitations in biomedical studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e73623.

Horton R. The hidden research paper. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2775–8.

Green SM, Callaham ML. Implementation of a journal peer reviewer stratification system based on quality and reliability. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(2):149–52 e4.

Hyland K. Hedging in scientific research articles. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 1998.

Book Google Scholar