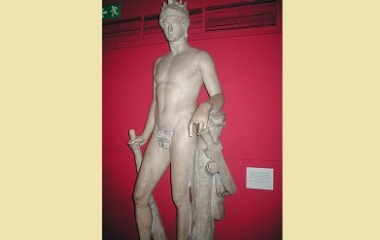

The son of either Poseidon or Aegeus and Aethra , Theseus was widely considered the greatest Athenian hero , the king who managed to politically unify Attica under the aegis of Athens . Son of either Aegeus , the king of Athens , or Poseidon , the god of the sea, and Aethra , a princess, Theseus was raised by his mother in the palaces of Troezen . Upon reaching adulthood and finding out the identity of his father, he set out on a journey to Athens, during which he managed to outwit and overpower few notorious brigands: Periphetes, Sinis, Phaea , Sciron, Cercyon, and Procrustes. In Athens, after thwarting Medea ’s attempts to eliminate him and capturing the Marathonian Bull, he volunteered to be one of the fourteen young Athenians sent to Crete as a sacrifice to the Minotaur so as to be able to kill the monster inside his Labyrinth. With the help of Ariadne who gave him a ball of thread to navigate himself inside the maze, Theseus managed to find and slay the Minotaur , after which he set sail back to Athens. There he ruled admirably for many years before an unsuccessful attempt (taken with his friend Pirithous ) to abduct Persephone from the Underworld resulted in his deposition and, consequently, treacherous murder by Lycomedes of Scyros.

Theseus in Troezen: Foreshadowings of a Hero

The night Theseus was conceived, his mother Aethra slept with Aegeus, the king of Athens, and Poseidon, the god of the sea. Whoever his father had been, Theseus’ exceptional parentage was evident even in his early years. Soon after Theseus reached adulthood, Aethra sent him to Athens.

The Story of Theseus’ Birth

Even after two wives – Meta and Chalciope – Aegeus, the esteemed king of Athens, was still childless. Fearing the intentions of his three brothers, he headed off to Pythia to learn from the Oracle if he will ever produce a male heir. As always, the advice was all but straightforward: “The bulging mouth of the wineskin, o best of men, loose not until thou hast reached the height of Athens.” Aegeus didn’t understand any of this and sorrowfully set out on a journey back home. On his way to Athens, however, he did make one stop: calling at Troezen , he didn’t miss the chance to ask its king Pittheus if he would help him decipher the Oracle’s ambiguous reply. Pittheus , wise as he famously was, understood it perfectly, but chose to use the knowledge to his benefit: wishing for a nephew with Aegeus’ blood, he got his guest drunk and then introduced him to his daughter Aethra; Aegeus slept with her, a few hours before Poseidon, the mighty god of the sea, did the same. Nine months later, Aethra gave birth to a beautiful child: Theseus.

Heracles’ Lion Skin

Whether the son of a god or an exceptional mortal, Theseus was discernibly unlike his peers even as a child, outshining them in every category. One time, when Heracles visited Pittheus’ kingdom and took off his lion-skin before sitting at the dinner table, the children of the palace, mistaking it for a real lion, all fled in fear and alarm. Theseus calmly took an ax and attacked the skin; even back then, watching the scene with eyes full of love and awe, Aethra already knew what she was supposed to do in few years’ time.

The Sword and the Sandals

Because, you see, before Aegeus left Troezen, he hid his sword and a pair of sandals under a great rock. “If you bore a son in nine months,” he told Aethra, “and if he is able to lift this rock once he reaches manhood – then send him to Athens with this sword and these sandals, for then I’d know that he is, indeed, my son, the future king of Athens.” When the time came, Aethra led Theseus to the rock and relayed to him his father’s message. Theseus lifted the rock with ease and, equipped with Theseus’ tokens of paternity, hit the road to Athens.

- Who were Zeus’ Lovers?

- How was the World created?

- What is the Trojan Horse?

On the Road to Athens

Sending him off to Athens, Aethra begged Theseus to travel by sea and, thus, bypass all the dangers which, by all accounts, lay on the land-route ahead of him. Theseus, however, wanted to earn himself a reputation worthy of a formidable hero before meeting his father. And by the time he reached Athens, he had vanquished so many famous villains – each with a memorable modus operandi – that people were already eager to compare him to his childhood idol, Heracles .

Periphetes, the Club-Bearer

Wielding a bronze club, Periphetes haunted the road near Epidaurus, threatening to savagely beat any traveler daring to cross paths with him. But Theseus wasn’t just any traveler: before Periphetes could realize, he managed to grab the club out of his hands and beat him to death with his own weapon. Emulating Heracles’ actions (who barely slipped out of the skin of the Nemean lion after completing his first labor), Theseus appropriated Periphetes’ club and, soon enough, it became the most recognizable piece of his equipment.

Sinis , the Pine-Bender

Before leaving Peloponnese, Theseus happened upon Sinis, the Pine Bender, so called because of his notorious habit of tying casual travelers to bent-down pine trees, which, upon release, instantaneously tore in two anyone unfortunate enough to be caught by this brutish bandit. However – and somewhat expectedly – Sinis was no match for Theseus: once again, the Athenian hero prevailed using his enemy’s own method of destruction.

Phaea, the Crommyonian Sow

An offspring of Typhon and Echidna , the Crommyonian Sow was either a huge wild pig which troubled the lands around Corinth and Megara or a vicious female robber nicknamed “The Sow” because of her appearance and vulgar manners. Either way, Theseus had no problems dealing with her as well.

Sciron, the Feet-Washer

Not much further, on the rocky coastal road of the Isthmus of Corinth , Theseus encountered Sciron, a mighty brigand who would force passing travelers to wash his feet – only so that he is able to kick his kneeling victims off the cliffs into the sea where a giant sea turtle waited to devour them. Recognizing the danger, once he bent down, Theseus grabbed Sciron by his foot, lifted him up, and then hurled him into the sea. The turtle got its meal either way.

Cercyon, the Wrestler

Compared to the other five malefactors Theseus came across on his road to Athens, Cercyon of Eleusis was somewhat old school: he challenged passersby on a win-or-die wrestling match. Not a good idea when your opponent is Theseus! Needless to say, it was Cercyon who got the wrong side of the proposed bargain. Or as a Greek poet put it in both humorous and oblique manner: Theseus “closed the wrestling school of Cercyon.”

Procrustes, the Stretcher

At first sight, Procrustes seemed a kind man: he offered his house as a shelter to any traveler in need who happened to run into him. The house had two beds, a short and a long one. However, once the ill-fated traveler would choose and lay down in one of them, Procrustes made sure to make him fit the bed ( not the other way around), either by using his infernal apparatus to elongate his extremities or by hammering down his length. As it should be evident by now, Theseus eventually dealt with his host in the same way he did with his guests. And even though we don’t know which one of Procrustes’ two beds spelled the end for Procrustes, it couldn’t have been a pleasurable experience either way.

Theseus in Athens: An Unwelcomed Guest

In Athens, Theseus was quickly recognized by Medea , the wife of his father, Aegeus. So, before Aegeus could make out Theseus’ identity, the hero had to prove his worth and capture the Marathonian Bull.

Aegeus and Medea

When Theseus arrived in Athens, he had the misfortune of being recognized by the wrong person: not by his father Aegeus, but by his then-wife, the sorceress Medea. Obviously, Medea didn’t want Aegeus to be succeeded in his throne by a son from a previous marriage, so she resolved to kill Theseus. She had no problem convincing Aegeus to her side, since the Athenian king still feared that he would be killed by one of his brother’s sons or, even worse, by an outsider. So, soon after arriving in Athens, Aegeus sent Theseus to capture the Marathonian Bull.

The Marathonian Bull

Now, the Marathonian Bull is actually the same bull Heracles managed to capture for his seventh labor. Formerly known as the Cretan Bull , the creature was either set free by Heracles or escaped from Tiryns by itself. After traversing the Isthmus of Corinth, it arrived at Marathon and bothered its inhabitants for years before Theseus finally managed to master it. After showing it to Aegeus and Medea, Theseus killed the Bull and sacrificed it to Apollo .

The Cup of Poison: Theseus Recognized

Medea didn’t expect Theseus to emerge victorious from his clash with the Marathonian Bull; nevertheless, she did have a Plan B, which included a feast and a cup of poison. Fortunately, barely a second before the poison touched Theseus’ lips, Aegeus recognized his sword and his sandals – and, moreover, Medea’s cruel intentions. Two proclamations followed, one naming Theseus as Aegeus’ rightful successor to the throne, and another banishing Medea from Athens forevermore.

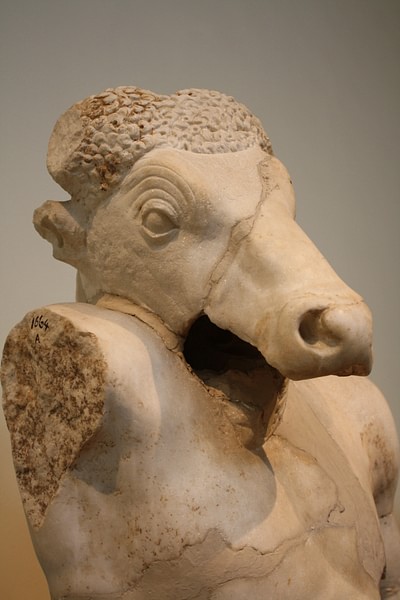

Theseus in Crete

Soon after Theseus’ return to Athens, it was due for Aegeus to pay the third yearly tribute to Minos , the king of Crete . Namely, in recompense for the death of Minos ’ son, Androgeus – once savagely killed by the Athenians out of jealousy and envy – Athens obliged to regularly send fourteen of its noblest young men and women to Crete, where each of them was destined to meet the same end: to be thrown into Daedalus ’ Labyrinth and be devoured by the monstrous half-man half-bull Minotaur.

Ariadne and the Minotaur

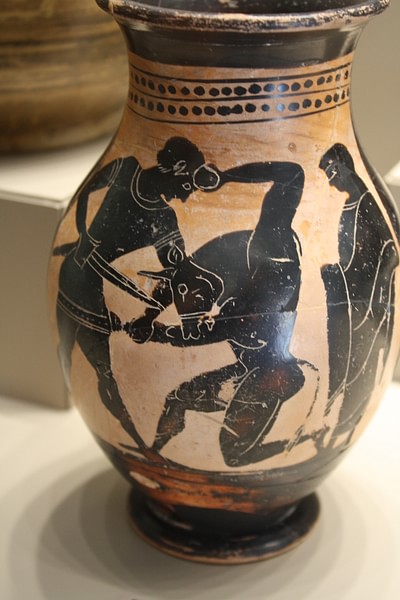

Always in pursuit for fame and glory – and now deeply despaired over the gruesome fate awaiting the innocent young Athenians – Theseus resolved to do something about this. So, when the time came, he volunteered to go to Crete, where Ariadne , Minos’ beautiful daughter, fell in love with him upon arrival, the very moment she laid eyes on the muscular Athenian prince. Determined to assist him, she begged Daedalus to tell her the secret of the Labyrinth, which, eventually, the old craftsman agreed to. And when the time came for Theseus to enter the Labyrinth, Ariadne gave him a ball of thread (provided by Daedalus) that was supposed to help him navigate himself inside the structure and guide him safely out of it.

Comforted by the fact that he would always be able to find his way out, Theseus delved deep into the Labyrinth and found the Minotaur haunting its innermost depths. As beastly as he was, the Minotaur was no match for Theseus’ strength and determination: after a brief fight, the Athenian killed the monster and followed the thread back to safety.

Theseus and Ariadne

Now, Theseus had promised Ariadne to marry her before even making his first step inside the Labyrinth; and, that’s the first thing he did after coming out of it safe and sound. After the brief marital ceremony, he took Ariadne with him and, together with the other young Athenians, left Crete. Strangely, his marriage with Ariadne lasted no more than just a few days: as soon as his ships reached the island of Dia (later called Naxos), Theseus left the sleeping Ariadne behind him and sailed away. Some say that he did this because he had fallen in love with another girl in the meantime (Panopeus’ daughter Aegle); others – because he had no choice but to obey the will of Dionysus who wanted Ariadne for himself. The latter claim that the god arrived on the island of Dia just moments after Theseus had left it, and swiftly carried Ariadne off in his chariot to be his beloved and immortal wife.

Theseus, the King of Athens

A broken promise.

Before setting off for Crete, Theseus had promised his father that, if he survived the Minotaur, he would change his ship’s black sail to a white one. Thus, Aegeus would be able to discern from some distance whether his son was still alive. Unfortunately, he either forgot his promise altogether or was too distraught to make the change on time. Watching from a vantage point, Aegeus couldn’t bear the sight he had most dreaded to see, so he hurled himself to his death straight away.

Unification of Attica

Theseus was now the king of Athens – and what a king he was! The list of his achievements is rather lengthy, but most authors agree that the greatest among them was the successful political unification ( synoikismos ) of Attica under Athens. In addition, Theseus is credited with instituting the festival of the Panathenaea and the Isthmian Games.

Phaedra and Hippolytus

From his expedition against the Amazons (see below), Theseus brought back to Athens one of their queens – either Antiope or Hippolyte – and she subsequently bore him a son, Hippolytus . After some time, he grew bored with his wife, so he found himself another: strangely enough, none other than Ariadne’s sister, Phaedra ! Phaedra gave Theseus two children – Acamas and Demophon – but, then, to her surprise, fell madly in love with her stepson, Hippolytus . After Hippolytus rejected her advances, she told Theseus that he had tried to rape her. Theseus cursed Hippolytus and, before long, his curse came true: Hippolytus was dragged to death by his horses. Either out of grief or because her treachery was exposed in the meantime, Phaedra hanged herself.

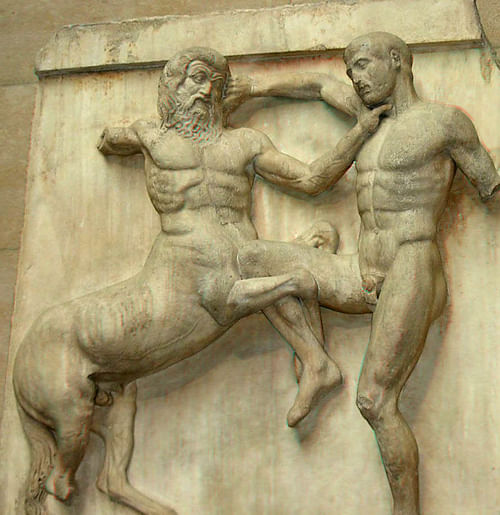

Theseus and Pirithous

While a king, Theseus befriended the king of the Lapiths, Pirithous . He shared numerous adventures with him, the most famous among them being the hunt for the Calydonian Boar , the Centauromachy, and an expedition among the Amazons , from which – to the utter dismay of the women warriors – both returned with new wives. Some years later, the two friends attempted a similar raid in the Underworld, but the abduction of Hades ’ wife, Persephone , didn’t go according to plan: instead of getting Persephone out of there, Theseus and Pirithous remained stuck inside, fixed immovable to two enchanted seats. On his way to capturing Cerberus , Heracles noticed and recognized the heroes ; even though, with some effort, he managed to free Theseus, the earth shook when he tried to do the same with Pirithous; so, Heracles had no choice but to leave Pirithous in the Underworld forevermore.

The Death of Theseus

Once freed from the Underworld, Theseus hurried back to Athens only to find out that the city now had a new ruler: Menestheus. He fled right away for refuge to Lycomedes, the king of the island of Scyros. A tragic mistake, since Lycomedes was a supporter of Menestheus! After a few days of feigned hospitality, Lycomedes took the unsuspecting Theseus on a tour of the island; the second they reached its highest cliff, he violently pushed Theseus to his death.

The Aftermath

Generations passed without much thought being given to Theseus. Then, during the Persian wars, Athenian soldiers reported seeing the ghost of Theseus, clad in bronze armor and in full charge, and came to believe that he was responsible for their victories. The Athenian general Cimon received a command from the Oracle at Delphi to find Theseus' bones and return them to Athens. He did so, and the gigantic skeleton of Theseus was reburied in a magnificent tomb in the heart of Athens, which thereon served as a sanctuary for the defenseless and the oppressed of the world.

Theseus Sources

Mentioned in both the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey,” Theseus is an important character in Euripides’ play “ Hippolytus .” Ovid recounts his conflict with Medea and the Minotaur in the seventh and the eighth book of his “Metamorphoses.” The first biography narrated in Plutarch’s influential “Parallel Lives” is that of Theseus .

See Also: Theseus Adventures , Minotaur, Aegeus, Aethra, Cretan Bull , Ariadne, Phaedra, Pirithous, Calydonian Boar

Theseus Q&A

Who was theseus.

The son of either Poseidon or Aegeus and Aethra , Theseus was widely considered the greatest Athenian hero , the king who managed to politically unify Attica under the aegis of Athens . Son of either Aegeus , the king of Athens , or Poseidon , the god of the sea, and Aethra , a princess, Theseus was raised by his mother in the palaces of Troezen .

What did Theseus rule over?

Theseus ruled over the Athens .

Where did Theseus live?

Theseus ' home was Athens .

Who were the parents of Theseus?

The parents of Theseus were Aegeus and Aethra .

Who were the consorts of Theseus?

Theseus ' consorts were Perigune, Antiope, Ariadne and Phaedra .

How many children did Theseus have?

Theseus had 4 children: Melanippus , Hippolytus , Acamas and Demophon .

Which were the symbols of Theseus?

Theseus ' symbol was the Club.

Theseus Associations

| , |

| , , Acamas, |

Cite This Article

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Who are some of the major figures of Greek mythology?

- What are some major works in Greek mythology?

- When did Greek mythology start?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- World History Encyclopedia - Theseus

- UEN Digital Press with Pressbooks - Mythology Unbound: An Online Textbook for Classical Mythology - Theseus

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Theseus, Hero of Athens

- Perseus Digital Library - A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology - Theseus

- Ancient Origins - Theseus: The Greek Hero That Slayed the Minotaur

- Mythopedia - Theseus

- IndiaNetzone - ISKCON

- National Museums Liverpool - Theseus and the Minotaur

- Encyclopedia Mythica - Theseus

- Theoi Greek Mythology - Greek Mythology: Who is Theseus

- Greek Gods and Goddesses - Theseus

- Theseus - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Theseus , great hero of Attic legend , son of Aegeus , king of Athens , and Aethra , daughter of Pittheus, king of Troezen (in Argolis ), or of the sea god, Poseidon , and Aethra. Legend relates that Aegeus, being childless, was allowed by Pittheus to have a child (Theseus) by Aethra. When Theseus reached manhood, Aethra sent him to Athens. On the journey he encountered many adventures. At the Isthmus of Corinth he killed Sinis, called the Pine Bender because he killed his victims by tearing them apart between two pine trees. After that Theseus dispatched the Crommyonian sow (or boar). Then from a cliff he flung the wicked Sciron, who had kicked his guests into the sea while they were washing his feet. Later he slew Procrustes , who fitted all comers to his iron bed by hacking or racking them to the right length. In Megara Theseus killed Cercyon, who forced strangers to wrestle with him.

On his arrival in Athens, Theseus found his father married to the sorceress Medea , who recognized Theseus before his father did and tried to persuade Aegeus to poison him. Aegeus, however, finally recognized Theseus and declared him heir to the throne. After crushing a conspiracy by the Pallantids, sons of Pallas (Aegeus’s brother), Theseus successfully attacked the fire-breathing bull of Marathon. Next came the adventure of the Cretan Minotaur , half man and half bull, shut up in the legendary Cretan Labyrinth.

Theseus had promised Aegeus that if he returned successful from Crete , he would hoist a white sail in place of the black sail with which the fatal ship bearing the sacrificial victims to the Minotaur always put to sea. But he forgot his promise, and when Aegeus saw the black sail, he flung himself from the Acropolis and died.

Theseus then united the various Attic communities into a single state and extended the territory of Attica as far as the Isthmus of Corinth. To the Isthmian Games in honour of Melicertes ( Leucothea ), he added games in honour of Poseidon . Alone or with Heracles he captured the Amazon princess Antiope (or Hippolyte ). As a result, the Amazons attacked Athens, and Hippolyte fell fighting on the side of Theseus. By her he had a son, Hippolytus , beloved of Theseus’s wife, Phaedra. Theseus is also said to have taken part in the Argonautic expedition and the Calydonian boar hunt.

The famous friendship between Theseus and Pirithous , one of the Lapiths, originated when Pirithous drove away some of Theseus’s cows. Theseus pursued, but when he caught up with him, the two heroes were so filled with admiration for each other that they swore brotherhood. Pirithous later helped Theseus to carry off the child Helen . In exchange, Theseus descended to the Underworld with Pirithous to help his friend rescue Persephone , daughter of the goddess Demeter . But they were caught and confined in Hades until Heracles came and released Theseus.

When Theseus returned to Athens, he faced an uprising led by Menestheus, a descendant of Erechtheus , one of the old kings of Athens. Failing to quell the outbreak, Theseus sent his children to Euboea , and after solemnly cursing the Athenians he sailed away to the island of Scyros. But Lycomedes, king of Scyros, killed Theseus by casting him into the sea from the top of a cliff. Later, according to the command of the Delphic oracle , the Athenian general Cimon fetched the bones of Theseus from Scyros and laid them in Attic earth.

Theseus’s chief festival, called Theseia, was held on the eighth of the month Pyanopsion (October), but the eighth day of every month was also sacred to him.

Greek Gods & Goddesses

Not many heroes are best known for their use of silk thread to escape a crisis, but it is true of Theseus. The Greek demi-god is known for feats of strength but is even better remembered for divine intelligence and wisdom. He had many great triumphs as a young man, but he died a king in exile filled with despair.

Theseus grew up with his mother, Aethra. She was the daughter of Pittheus, the king of Troezen. Theseus had two fathers. One father was Aegeus, King of Athens, who visited Troezen after consulting the Oracle at Delphi about finding an heir. He married Aethra then left her behind, telling her that if she had a child and if that child could move a boulder and retrieve the sword and sandals he had buried underneath, then she should send that child to Athens. Theseus’ other father was Poseidon , the god of the sea, who joined Aethra for a seaside walk on her wedding night.

When Theseus grew up, he easily picked up the large boulder and found his father’s items, so his mother gave him directions to Athens. Rather than take the safer sea route, he chose to take the land route even though he knew there would be multiple dangers ahead. Along the road he had to fight six battles. He defeated four bandits, one monster pig and one giant, winning every battle through strength and cunning.

When Theseus arrived at Athens, he did not reveal himself to his father. His father had married the sorceress Medea . She recognized Theseus and wanted to kill him. First, she sent him on a dangerous quest to capture the Marathonian bull. When he was successful, she gave him poisoned wine. Medea’s husband knew of her plan. However at the last moment, Aegeus saw Theseus had the sword and sandals he had buried and knocked the cup from his hand. Medea fled to Asia. Aegeus welcomed Theseus and named him as heir to the throne.

Battle with the Minotaur

Sometime later came Theseus’ greatest challenge. Every seven years King Minos of Crete forced Athens to send seven courageous young men and seven beautiful young women to sacrifice to the Minotaur , a half-man, half-bull creature that lived in a complicated maze under Minos’ castle. This tribute was to prevent Minos starting a war after Minos’ son, Androgens, was killed in Athens by unknown assassins during the games. Theseus volunteered to be one of the men, promising to kill the Minotaur and end the brutal tradition. Aegeus was heartbroken, but made Theseus promise to change the ship’s flags from black to white before he returned to show that he had succeeded.

When Theseus arrived in Crete, King Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell in love with him and promised to help him escape the labyrinth if he agreed to take her with him and marry her. He agreed. Ariadne brought him a ball of silk thread, a sword and instructions from the maze’s creator Daedalus – once in the maze go straight and down, never to the left or right.

Theseus and the Athenians entered the labyrinth and tied the end of the thread near the door, letting out the string as they walked. They continued straight until they found the sleeping Minotaur in the center. Theseus attacked and a terrible battle ensued until the Minotaur was killed. They then followed the thread back to the door and were able to board the ship with the waiting Ariadne before King Minos knew what had happened.

That night Theseus had a dream – likely sent by the god Dionysus – saying he had to leave Ariadne behind because Fate had another path for her. In the morning, Theseus left her weeping on the Island of Naxos and sailed to Athens. Heartbroken, perhaps cursed by Ariadne, Theseus forgot to change the ship’s flags from black to white.

His father, seeing the black flags on the approaching ship, assumed Theseus was dead . Aegeus threw himself off the cliffs and into the sea to his death. The sea east of Greece is still called the Aegean Sea.

Ariadne would later marry Dionysus.

King of Athens

Theseus became King of Athens after his father’s death. He led the people well and united the people around Athens. He is credited as a creator of democracy because he gave up some of his powers to the Assembly. He continued to have adventures.

During one of his adventures, he travelled to the Underworld with his friend Pirithous, who was pursuing Persephone . Both friends sat on rocks to rest and found that they could not move. Theseus remained there for many months until he was rescued by his cousin Heracles , who was in the Underworld on his 12th task. Pirithous had been led away by Furies in the meantime and was not rescued.

On another adventure with Heracles, he set out to rescue the Amazon Queen Hippolyta’s girdle. After the quest, Theseus married her and they had a son named Hippolytus. When Hippolytus was a young man, he caused a fit of jealousy between the goddesses Aphrodite and Artemis .

Aphrodite, the goddess of love, caused Phaedra, who was Theseus’ second wife and Ariadne’s younger sister, to fall in love with her stepson. Phaedra killed herself and left a note blaming Hippolytus’ bad treatment of her for her actions.

When Theseus saw the note, he called on his father Poseidon to take revenge on Hippolytus. A sea monster frightened the horses of Hippolytus’ chariot so that he was thrown from it, got tangled in the reins and dragged. Then Artemis let Theseus know he had been deceived and he ran to find his son, who died in his arms.

Due to his despair over losing his wife and his son, Theseus quickly lost popularity and the support of his people. He fled Athens for the Island of Skyros, where the king feared Theseus was plotting to overthrow him and pushed him off a cliff and into the sea to this death.

After His Death

Some ancient Greeks believed Theseus was a historical king of Athens. During the Persian Wars from 499 to 449 B.C., Greek soldiers reported seeing Theseus’ ghost on the battlefield and believed it helped lead them to victory. In 476 B.C., the Athenian Kimon is said to have found and returned Theseus’ bones to Athens and then built a shrine that also served as a sanctuary for the defenseless.

The ship Theseus used to sail to Crete was also believed to have been preserved in the city harbor until about 300 B.C. As wooden boards rotted they were replaced to keep the ship afloat. In time, people questioned whether any of the boards could have been from the original ship, which led to a question philosophers debate called the Ship of Theseus Paradox: “Is an object that has had all of its parts replaced still the original object?”

Quick Facts about Theseus

— Semigod ( demigod ) with two fathers, including the sea god Poseidon — Defeated the Minotaur — King of Athens credited with development of democracy — Lost his throne after the death of his wife and son — Aegean Sea is named for his human father — Frequently depicted in ancient and Romantic art — Experienced six tasks on his journey to Athens — Some believed him to be based on a historic kin

Link/cite this page

If you use any of the content on this page in your own work, please use the code below to cite this page as the source of the content.

Link will appear as Theseus: https://greekgodsandgoddesses.net - Greek Gods & Goddesses, February 11, 2017

- 1.1 Etymology

- 1.2 Pronunciation

- 1.3.1 Derived terms

- 1.3.2 Related terms

- 1.3.3 Translations

- 1.4 References

- 1.5 Further reading

- 1.6 Anagrams

- 2.1 Etymology

- 2.2 Pronunciation

- 3.1 Etymology

- 3.2 Pronunciation

- 3.3.1 Declension

- 3.3.2 Descendants

- 3.4 References

From Late Middle English thesis ( “ lowering of the voice ” ) [ 1 ] and also borrowed directly from its etymon Latin thesis ( “ proposition, thesis; lowering of the voice ” ) , from Ancient Greek θέσῐς ( thésis , “ arrangement, placement, setting; conclusion, position, thesis; lowering of the voice ” ) , from τῐ́θημῐ ( títhēmi , “ to place, put, set; to put down in writing; to consider as, regard ” ) [ 2 ] [ 3 ] (ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *dʰeh₁- ( “ to do; to place, put ” ) ) + -σῐς ( -sis , suffix forming abstract nouns or nouns of action, process, or result ) . The English word is a doublet of deed .

Sense 1.1 (“proposition or statement supported by arguments”) is adopted from antithesis . [ 2 ] Sense 1.4 (“initial stage of reasoning”) was first used by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), and later applied to the dialectical method of his countryman, the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831).

The plural form theses is borrowed from Latin thesēs , from Ancient Greek θέσεις ( théseis ) .

Pronunciation

- ( Received Pronunciation ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθiːsɪs/ , ( archaic ) /ˈθɛsɪs/

| Audio ( ): | ( ) |

- ( General American ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθisɪs/

- Rhymes: -iːsɪs

- Hyphenation: the‧sis

- ( Received Pronunciation ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθiːsiːz/

- ( General American ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈθisiz/

- Rhymes: -iːsiːz

- Hyphenation: the‧ses

thesis ( plural theses )

- ( rhetoric ) A proposition or statement supported by arguments .

- 1766 , [ Oliver Goldsmith ], “The Conclusion”, in The Vicar of Wakefield: [ … ] , volume II, Salisbury, Wiltshire: [ … ] B. Collins, for F [ rancis ] Newbery , [ … ] , →OCLC , pages 218–219 : I told them of the grave, becoming, and ſublime deportment they ſhould aſſume upon this myſtical occaſion, and read them two homilies and a theſis of my own compoſing, in order to prepare them.

- ( mathematics , computer science ) A conjecture , especially one too vague to be formally stated or verified but useful as a working convention.

- ( logic ) An affirmation , or distinction from a supposition or hypothesis .

- ( philosophy ) In the dialectical method of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel : the initial stage of reasoning where a formal statement of a point is developed ; this is followed by antithesis and synthesis .

- ( music , prosody , originally ) The action of lowering the hand or bringing down the foot when indicating a rhythm ; hence, an accented part of a measure of music or verse indicated by this action; an ictus , a stress . Antonym: arsis

- ( music , prosody , with a reversal of meaning ) A depression of the voice when pronouncing a syllables of a word ; hence, the unstressed part of the metrical foot of a verse upon which such a depression falls , or an unaccented musical note .

Derived terms

- all but thesis

- bachelor's thesis

- Church-Turing thesis

- conflict thesis

- doctoral thesis

- graduate thesis

- Habakkuk thesis

- master's thesis

- Merton thesis

- private language thesis

- thesis defense

- thesis statement

Related terms

Translations.

| (tʻez) , (tézis), (palažénnje), (téza) (téza), (tézis) / (leon dim ), / (leon tai ) / (lùndiǎn), / (lùntí) , , (tezisi) (thésis) , (tēze), (ろんだい, rondai), (しゅちょう, shuchō), (ていりつ, teiritsu) (teje), (nonje), (ronje) (North Korea) (teza) (tɛ́zis), (položénije) , , , , (téza), (tézys), (polóžennja) |

| (ʔuṭrūḥa) (atenaxosutʻyun), (disertacʻia), (diplomayin ašxatankʻ) (dysjertácyja), (dysertácyja), (dyplómnaja rabóta) (disertácija) , / (leon man ) / (lùnwén) , , , , ; ; , (diserṭacia) , , , , , (only a doctoral thesis) (mahāśodh nibandh) (téza) , (postgraduate), (ろんぶん, ronbun) (dissertasiä), (diplomdyq jūmys) (nɨkkheepaʼbɑt) (nonmun), (ronmun) (North Korea) (dissertatsiya) (wi tha nyā ni phon) (disertacija) or , (pâyân-nâme), , , (dissertácija), (diplómnaja rabóta) , , , (dissertatsiya) (wít-tá-yaa-ní-pon), (bpà-rin-yaa-ní-pon), (ní-pon) , , (dysertácija), (dyplómna robóta) , , |

| (thésis) |

- ^ “ thē̆sis, n. ”, in MED Online , Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan , 2007 .

- ^ “ thesis, n. ”, in Lexico , Dictionary.com ; Oxford University Press , 2019–2022 .

Further reading

- “ thesis ”, in The Century Dictionary [ … ] , New York, N.Y.: The Century Co. , 1911 , →OCLC .

- “ thesis ”, in Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary , Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam , 1913 , →OCLC .

- Heists , Sethis , heists , shiest , shites , sithes , thises

From Latin thesis , from Ancient Greek θέσις ( thésis , “ a proposition, a statement, a thing laid down, thesis in rhetoric, thesis in prosody ” ) .

| Audio: | ( ) |

thesis f ( plural theses or thesissen , diminutive thesisje n )

- Dated form of these . Synonyms: dissertatie , proefschrift , scriptie

From Ancient Greek θέσις ( thésis , “ a proposition, a statement, a thing laid down, thesis in rhetoric, thesis in prosody ” ) .

- ( Classical Latin ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈtʰe.sis/ , [ˈt̪ʰɛs̠ɪs̠]

- ( modern Italianate Ecclesiastical ) IPA ( key ) : /ˈte.sis/ , [ˈt̪ɛːs̬is]

thesis f ( genitive thesis ) ; third declension

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| | ||

Descendants

- → Dutch: thesis

- → Armenian: թեզ ( tʻez )

- → Dutch: these

- → Persian: تز ( tez )

- → Romanian: teză

- → Turkish: tez

- Galician: tese

- Italian: tesi

- English: thesis

- Portuguese: tese

- Spanish: tesis

- “ thesis ”, in Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short ( 1879 ) A Latin Dictionary , Oxford: Clarendon Press

- thesis in Gaffiot, Félix ( 1934 ) Dictionnaire illustré latin-français , Hachette.

- English terms derived from Proto-Indo-European

- English terms derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *dʰeh₁-

- English terms inherited from Middle English

- English terms derived from Middle English

- English terms borrowed from Latin

- English terms derived from Latin

- English terms derived from Ancient Greek

- English doublets

- English 2-syllable words

- English terms with IPA pronunciation

- English terms with audio links

- Rhymes:English/iːsɪs

- Rhymes:English/iːsɪs/2 syllables

- Rhymes:English/iːsiːz

- Rhymes:English/iːsiːz/2 syllables

- English lemmas

- English nouns

- English countable nouns

- English nouns with irregular plurals

- en:Rhetoric

- English terms with quotations

- en:Mathematics

- en:Computer science

- en:Philosophy

- English contranyms

- Dutch terms derived from Latin

- Dutch terms derived from Ancient Greek

- Dutch terms with audio links

- Dutch lemmas

- Dutch nouns

- Dutch nouns with Latin plurals

- Dutch nouns with plural in -en

- Dutch feminine nouns

- Dutch dated forms

- Latin terms derived from Proto-Indo-European

- Latin terms derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *dʰeh₁-

- Latin terms borrowed from Ancient Greek

- Latin terms derived from Ancient Greek

- Latin 2-syllable words

- Latin terms with IPA pronunciation

- Latin lemmas

- Latin nouns

- Latin third declension nouns

- Latin feminine nouns in the third declension

- Latin feminine nouns

- Word of the day archive

- English entries with language name categories using raw markup

- Pages with 3 entries

- Terms with Armenian translations

- Terms with Asturian translations

- Terms with Azerbaijani translations

- Terms with Belarusian translations

- Terms with Bulgarian translations

- Terms with Catalan translations

- Terms with Cantonese translations

- Mandarin terms with redundant transliterations

- Terms with Mandarin translations

- Terms with Czech translations

- Terms with Danish translations

- Terms with Dutch translations

- Terms with Esperanto translations

- Terms with Estonian translations

- Terms with Finnish translations

- Terms with French translations

- Terms with Galician translations

- Terms with Georgian translations

- Terms with German translations

- Terms with Ancient Greek translations

- Terms with Hungarian translations

- Terms with Italian translations

- Terms with Japanese translations

- Terms with Korean translations

- Terms with Latin translations

- Terms with Macedonian translations

- Terms with Malay translations

- Terms with Maori translations

- Terms with Norwegian Bokmål translations

- Terms with Persian translations

- Terms with Polish translations

- Terms with Portuguese translations

- Russian terms with non-redundant manual transliterations

- Terms with Russian translations

- Terms with Serbo-Croatian translations

- Terms with Slovak translations

- Terms with Slovene translations

- Terms with Spanish translations

- Terms with Swedish translations

- Terms with Tagalog translations

- Terms with Turkish translations

- Terms with Ukrainian translations

- Terms with Vietnamese translations

- Terms with Arabic translations

- Terms with Gujarati translations

- Terms with Hebrew translations

- Terms with Indonesian translations

- Terms with Kazakh translations

- Terms with Khmer translations

- Terms with Kyrgyz translations

- Terms with Lao translations

- Terms with Latvian translations

- Terms with Lithuanian translations

- Terms with Norwegian Nynorsk translations

- Terms with Romanian translations

- Terms with Tajik translations

- Terms with Thai translations

- Terms with Uzbek translations

- Terms with Middle English translations

Navigation menu

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Theseus, hero of athens.

Terracotta amphora (jar)

Signed by Taleides as potter

Terracotta kylix: eye-cup (drinking cup)

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask)

Attributed to the Diosphos Painter

Terracotta kylix (drinking cup)

Attributed to the Briseis Painter

Terracotta calyx-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water)

Attributed to a painter of the Group of Polygnotos

Terracotta Nolan neck-amphora (jar)

Attributed to the Dwarf Painter

Attributed to the Eretria Painter

Marble sarcophagus with garlands and the myth of Theseus and Ariadne

Andrew Greene Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

August 2009

In the ancient Greek world, myth functioned as a method of both recording history and providing precedent for political programs. While today the word “myth” is almost synonymous with “fiction,” in antiquity, myth was an alternate form of reality . Thus, the rise of Theseus as the national hero of Athens, evident in the evolution of his iconography in Athenian art, was a result of a number of historical and political developments that occurred during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.

Myth surrounding Theseus suggests that he lived during the Late Bronze Age, probably a generation before the Homeric heroes of the Trojan War. The earliest references to the hero come from the Iliad and the Odyssey , the Homeric epics of the early eighth century B.C. Theseus’ most significant achievement was the Synoikismos, the unification of the twelve demes, or local settlements of Attica, into the political and economic entity that became Athens.

Theseus’ life can be divided into two distinct periods, as a youth and as king of Athens . Aegeus, king of Athens, and the sea god Poseidon ( 53.11.4 ) both slept with Theseus’ mother, Aithra, on the same night, supplying Theseus with both divine and royal lineage. Theseus was born in Aithra’s home city of Troezen, located in the Peloponnesos , but as an adolescent he traveled around the Saronic Gulf via Epidauros, the Isthmus of Corinth, Krommyon, the Megarian Cliffs, and Eleusis before finally reaching Athens. Along the way he encountered and dispatched six legendary brigands notorious for attacking travelers.

Upon arriving in Athens, Theseus was recognized by his stepmother, Medea, who considered him a threat to her power. Medea attempted to dispatch Theseus by poisoning him, conspiring to ambush him with the Pallantidae Giants, and by sending him to face the Marathonian Bull ( 56.171.48 ).

Likely the most famous of Theseus’ deeds was the slaying of the Minotaur ( 64.300 ; 47.11.5 ; 09.221.39 ). Athens was forced to pay an annual tribute of seven maidens and seven youths to King Minos of Crete to feed the Minotaur, half man, half bull, that inhabited the labyrinthine palace of Minos at Knossos. Theseus, determined to end Minoan dominance, volunteered to be one of the sacrificial youths. On Crete, Theseus seduced Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, who conspired to help him kill the Minotaur and escape by giving him a ball of yarn to unroll as he moved throughout the labyrinth ( 90.12a,b ). Theseus managed to flee Crete with Ariadne, but then abandoned her on the island of Naxos during the voyage back to Athens. King Aegeus had told Theseus that upon returning to Athens, he was to fly a white sail if he had triumphed over the Minotaur, and to instruct the crew to raise a black sail if he had been killed. Theseus, forgetting his father’s direction, flew a black sail as he returned. Aegeus, in his grief, threw himself from the cliff at Cape Sounion into the Aegean, making Theseus the new king of Athens and giving the sea its name.

There is but a sketchy picture of Theseus’ deeds in later life, gleaned from brief literary references of the early Archaic period , mostly from fragmentary works by lyric poets. Theseus embarked on a number of expeditions with his close friend Peirithoos, the king of the Lapith tribe from Thessaly in northern Greece. He also undertook an expedition against the Amazons, in some versions with Herakles , and kidnapped their queen Antiope, whom he subsequently married ( 31.11.13 ; 56.171.42 ). Enraged by this, the Amazons laid siege to Athens, an event that became popular in later artistic representations.

There are certain aspects of the myth of Theseus that were clearly modeled on the more prominent hero Herakles during the early sixth century B.C. Theseus’s encounter with the brigands parallels Herakles’ six deeds in the northern Peloponnesos. Theseus’ capture of the Marathonian Bull mirrors Herakles’ struggle with the Cretan Bull. There also seems to be some conflation of the two since they both partook in an Amazonomachy and a Centauromachy. Both heroes additionally have links to Athena and similarly complex parentage with mortal mothers and divine fathers.

However, while Herakles’ life appears to be a string of continuous heroic deeds, Theseus’ life represents that of a real person, one involving change and maturation. Theseus became king and therefore part of the historical lineage of Athens, whereas Herakles remained free from any geographical ties, probably the reason that he was able to become the Panhellenic hero. Ultimately, as indicated by the development of heroic iconography in Athens, Herakles was superseded by Theseus because he provided a much more complex and local hero for Athens.

The earliest extant representation of Theseus in art appears on the François Vase located in Florence, dated to about 570 B.C. This famous black-figure krater shows Theseus during the Cretan episode, and is one of a small number of representations of Theseus dated before 540 B.C. Between 540 and 525 B.C. , there was a large increase in the production of images of Theseus, though they were limited almost entirely to painted pottery and mainly showed Theseus as heroic slayer of the Minotaur ( 09.221.39 ; 64.300 ). Around 525 B.C. , the iconography of Theseus became more diverse and focused on the cycle of deeds involving the brigands and the abduction of Antiope. Between 490 and 480 B.C. , interest centered on scenes of the Amazonomachy and less prominent myths such as Theseus’ visit to Poseidon’s palace ( 53.11.4 ). The episode is treated in a work by the lyric poet Bacchylides. Between 450 and 430 B.C. , there was a decline in representations of the hero on vases; however, representations in other media increase. In the mid-fifth century B.C. , youthful deeds of Theseus were placed in the metopes of the Parthenon and the Hephaisteion, the temple overlooking the Agora of Athens. Additionally, the shield of Athena Parthenos, the monumental chryselephantine cult statue in the interior of the Parthenon, featured an Amazonomachy that included Theseus.

The rise in prominence of Theseus in Athenian consciousness shows an obvious correlation with historical events and particular political agendas. In the early to mid-sixth century B.C. , the Athenian ruler Solon (ca. 638–558 B.C. ) made a first attempt at introducing democracy. It is worth noting that Athenian democracy was not equivalent to the modern notion; rather, it widened political involvement to a larger swath of the male Athenian population. Nonetheless, the beginnings of this sort of government could easily draw on the Synoikismos as a precedent, giving Solon cause to elevate the importance of Theseus. Additionally, there were a large number of correspondences between myth and historical events of this period. As king, Theseus captured the city of Eleusis from Megara and placed the boundary stone at the Isthmus of Corinth, a midpoint between Athens and its enemy. Domestically, Theseus opened Athens to foreigners and established the Panathenaia, the most important religious festival of the city. Historically, Solon also opened the city to outsiders and heightened the importance of the Panathenaia around 566 B.C.

When the tyrant Peisistratos seized power in 546 B.C. , as Aristotle noted, there already existed a shrine dedicated to Theseus, but the exponential increase in artistic representations during Peisistratos’ reign through 527 B.C. displayed the growing importance of the hero to political agenda. Peisistratos took Theseus to be not only the national hero, but his own personal hero, and used the Cretan adventures to justify his links to the island sanctuary of Delos and his own reorganization of the festival of Apollo there. It was during this period that Theseus’s relevance as national hero started to overwhelm Herakles’ importance as Panhellenic hero, further strengthening Athenian civic pride.

Under Kleisthenes, the polis was reorganized into an even more inclusive democracy, by dividing the city into tribes, trittyes, and demes, a structure that may have been meant to reflect the organization of the Synoikismos. Kleisthenes also took a further step to outwardly claim Theseus as the Athenian hero by placing him in the metopes of the Athenian treasury at Delphi, where he could be seen by Greeks from every polis in the Aegean.

The oligarch Kimon (ca. 510–450 B.C. ) can be considered the ultimate patron of Theseus during the early to mid-fifth century B.C. After the first Persian invasion (ca. 490 B.C. ), Theseus came to symbolize the victorious and powerful city itself. At this time, the Amazonomachy became a key piece of iconography as the Amazons came to represent the Persians as eastern invaders. In 476 B.C. , Kimon returned Theseus’ bones to Athens and built a shrine around them which he had decorated with the Amazonomachy, the Centauromachy, and the Cretan adventures, all painted by either Mikon or Polygnotos, two of the most important painters of antiquity. This act represented the final solidification of Theseus as national hero.

Greene, Andrew. “Theseus, Hero of Athens.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/thes/hd_thes.htm (August 2009)

Further Reading

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland, and Paul T. Barber. When They Severed Earth from Sky: How the Human Mind Shapes Myth . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Boardman, John "Herakles." In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologicae Classicae , vol. V, 1. Zürich: Artemis, 1981.

Camp, John McK. The Archaeology of Athens . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Gehrke, Hans-Joachim. "Myth, History, and Collective Identity: Uses of the Past in Ancient Greece and Beyond." In The Historian's Craft in the Age of Herodotus , edited by Nino Luraghi, pp. 286–313. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Harrison, Evelyn B. "Motifs of the City Siege of Athena Parthenos." American Journal of Archaeology 85, no. 3 (July 1981), pp. 281–317.

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth, eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary . 3d ed., rev. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Neils, Jenifer. "Theseus." In Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologicae Classicae , vol. VII, 1, pp. 922–51. Zürich: Artemis, 1981.

Servadei, Cristina. La figura di Theseus nella ceramica attica: Iconografia e iconologia del mito nell'Atene arcaica e classica . Bologna: Ante Quem, 2005.

Shapiro, H. A. "Theseus: Aspects of the Hero in Archaic Greece." In New Perspectives in Early Greek Art , edited by Diana Buitron-Oliver, pp. 123–40. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Shapiro, H. A. Art and Cult under the Tyrants in Athens . Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1989.

Simon, Erika. Festivals of Attica . Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Related Essays

- Greek Gods and Religious Practices

- The Labors of Herakles

- Minoan Crete

- The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.)

- Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece

- Greek Art in the Archaic Period

- Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- The Kithara in Ancient Greece

- Music in Ancient Greece

- Mycenaean Civilization

- Mystery Cults in the Greek and Roman World

- Paintings of Love and Marriage in the Italian Renaissance

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Scenes of Everyday Life in Ancient Greece

- Women in Classical Greece

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of the Ancient Greek World

- Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Ancient Greece, 1–500 A.D.

- Achaemenid Empire

- Ancient Greek Art

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Roman Art

- Anthropomorphism

- Archaeology

- Archaic Period

- Black-Figure Pottery

- Classical Period

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Funerary Art

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- Greek Literature / Poetry

- Herakles / Hercules

- Homer’s Iliad

- Homer’s Odyssey

- Literature / Poetry

- Mycenaean Art

- Mythical Creature

- Painted Object

- Poseidon / Neptune

- Relief Sculpture

- Sarcophagus

- Sculpture in the Round

Artist or Maker

- Briseis Painter

- Diosphos Painter

- Dwarf Painter

- Eretria Painter

- Pollaiuolo, Antonio

- Polygnotos Group

- Taleides Painter

Theseus and Aethra by Laurent de La Hyre (ca. 1635–1636)

Theseus—son of Aegeus (or Poseidon) and Aethra—was by far the most important of the mythical heroes and kings of Athens. His heroic accomplishments included killing the Minotaur, though he was also remembered as a political innovator who transformed his city into a major regional power.

Theseus was raised by his mother in Troezen but moved to Athens upon reaching adulthood. He traveled widely and performed many heroic exploits, eventually sailing to Crete to kill the Minotaur.

As king of Athens, Theseus greatly improved the government and expanded the power of his city. He was sometimes seen as the mythical predecessor of the political unification of Attica.

Who were Theseus’ parents?

Theseus was the product of an affair between Aegeus, the king of Athens, and Aethra, a princess of Troezen. But in some traditions, the sea god Poseidon slept with Aethra the same night as Aegeus, making Theseus his son instead.

Theseus was raised by his mother Aethra in Troezen. The identity of his father was kept secret until Theseus had proven himself worthy of his inheritance.

Whom did Theseus marry?

Theseus had a weakness for women and was not always loyal to them. He eventually married Phaedra, a princess from Crete. Their marriage ended disastrously, however, when Phaedra fell passionately in love with Hippolytus, Theseus’ son by another consort.

Aside from Phaedra, Theseus had many lovers throughout his storied career. These included Phaedra’s own sister Ariadne; an Amazon queen named either Antiope or Hippolyta; and even the famous Helen, according to some traditions.

Ariadne by Asher Brown Durand, after John Vanderlyn (ca. 1831–1835)

How did Theseus die?

Like many Greek heroes, Theseus did not die happily. In the common tradition, he was exiled from Athens after his recklessness turned the city and its nobility against him. He traveled to the small island of Scyros, where he fell to his death from a cliff (or was thrown from the cliff by the local king).

Roman fresco of Theseus from Herculaneum (ca. 45–79 CE)

Theseus Slays the Minotaur

Shortly after meeting his father Aegeus in Athens, Theseus voyaged to the island of Crete as one of the fourteen “tributes” sent annually as a sacrifice to the Minotaur—a half-man, half-bull hybrid imprisoned in the Labyrinth. Theseus vowed to kill the Minotaur and end the bloody custom once and for all.

In Crete, Theseus’ good looks won him the love of Ariadne, the daughter of the king. Ariadne helped Theseus on his mission by giving him a ball of thread that he unraveled as he made his way through the maze-like Labyrinth. After finding and killing the Minotaur, Theseus re-wound the thread to safely escape.

Theseus Slaying the Minotaur by Antoine-Louis Barye (1843)

The name Theseus was likely derived from the Greek word θεσμός ( thesmos ), which means “institution.” Theseus’ name thus reflects his mythical role as a founder or reformer of the Athenian government.

Pronunciation

| Theseus | Θησεύς |

| [THEE-see-uhs] | /ˈθiːsiəs/ |

In his iconography, Theseus is usually depicted as a handsome, strong, and beardless young hero. Theseus’ battle with the half-bull Minotaur was an especially popular theme in Greek art.

Theseus’ father was either Poseidon , the god of the sea, or Aegeus, the king of Athens. His mother was Aethra, the daughter of King Pittheus of Troezen.

Family Tree

Theseus was the son of Aethra, the daughter of King Pittheus of Troezen, and either Aegeus or Poseidon. Aegeus, who was the king of Athens, had no children and therefore no heir to his throne. Hoping to remedy this, Aegeus went to Delphi, where he received a strange prophecy:

The bulging mouth of the wineskin, O best of men, loose not until thou hast reached the height of Athens. [1]

On his way back to Athens, Aegeus stopped at Troezen, where he was entertained by King Pittheus. Aegeus revealed the prophecy to Pittheus, who understood its meaning and plied Aegeus with wine. Aegeus then slept with Pittheus’ daughter Aethra.

Before leaving Troezen, Aegeus hid a sword and sandals under a large stone. He told Aethra that if she had a son, she should wait until he had grown up and bring him to the stone. If he managed to lift it and retrieve the tokens, he should be sent to Athens.

According to other versions, Aethra had also been seduced by the god Poseidon, and it was he who was Theseus’ father. [2] In any case, Theseus grew up to be a strong and intelligent young man. When he had come of age, his mother took him to the stone where Aegeus had long ago deposited his sword and sandals. Theseus successfully retrieved these tokens and left for Athens to find his father.

Journey to Athens

Instead of travelling to Athens by sea, Theseus decided to make a name for himself by taking the more dangerous overland route through the Greek Isthmus. At the time, it was plagued by bandits and monsters. On his way to Athens, Theseus cleared the Isthmus in what are sometimes called the “Six Labors of Theseus”:

At Epidaurus, Theseus met Periphetes, famous for slaughtering travellers with a giant club. Theseus killed Periphetes and claimed the club for himself.

Theseus then met Sinis, who would bend two pine trees to the ground, tie a traveller between the bent trees, and then let the trees go, thus tearing apart the traveller’s limbs. Theseus killed Sinis using this same method. He then seduced Sinis’ daughter Perigone, who later gave birth to a son named Melanippus.

Theseus next killed the monstrous Crommyonian Sow (sometimes called Phaea), [3] an enormous pig that terrorized travellers.

Near Megara, Theseus met the robber Sciron, who would throw his victims off a cliff. Theseus, as usual, used his opponent’s method against him and threw Sciron off a cliff.

At Eleusis, Theseus fought Cerycon , who challenged travellers to a wrestling match and killed whomever he defeated. Following this model, Theseus wrestled Cerycon, beat him, and killed him.

Finally, Theseus defeated Procrustes (sometimes called Damastes), who had two beds that he would offer to travellers. If the traveller was too tall to fit in the bed, Procrustes would cut off their limbs; if they were too short, he would stretch them until they fit. Theseus killed Procrustes by putting him on one of his beds, cutting off his legs, and then decapitating him.

Arrival at Athens

After clearing the Isthmus, Theseus finally arrived at Athens. He did not, however, reveal himself to his father Aegeus immediately. Aegeus became suspicious of the stranger and consulted Medea , whom he had married after sleeping with Aethra.

Medea realized that Theseus was the son of Aegeus, but she did not want Aegeus to recognize him. She was afraid he would choose Theseus as his heir over her own son. Medea therefore tried to trick her husband into killing Theseus.

In some stories, Medea convinced Aegeus to send Theseus to slay the monstrous Bull of Marathon, hoping that the bull would kill him first.

Painting in tondo of kylix showing Theseus fighting the Bull of Marathon by unknown artist (c. 440–430 BC).

In other stories, Medea tried to poison Theseus. But Aegeus recognized Theseus by the sword he was carrying (the sword he had left with Aethra at Troezen) and stopped him from drinking the poison. Medea fled into exile.

Medea was not the only threat to Theseus’ standing in Athens. The sons of Aegeus’ brother Pallas (often called the Pallantides) had hoped to inherit the throne if their uncle Aegeus died childless. According to some sources, the sons of Pallas ambushed or rebelled against Theseus and Aegeus. This attempt failed, however, and after Theseus killed the sons of Pallas he was secured as the heir to the throne of Athens. [4]

The Minotaur

During Aegeus’ reign, the Athenians were forced to send a regular tribute of fourteen youths (seven boys and seven girls) to Minos , the king of the island of Crete. This was reparation for the murder of Minos’ son Androgeus in Athens several years before.

When the fourteen tributes reached Crete, they were fed to the Minotaur, a terrible bull-man hybrid born from an affair between a divine bull and Minos’ wife Pasiphae:

A mingled form and hybrid birth of monstrous shape, ... Two different natures, man and bull, were joined in him. [5]

The Minotaur was imprisoned in the Labyrinth, a giant maze built by the Athenian architect Daedalus. None of the tributes who were sent into the Labyrinth ever made it out.

Soon after his arrival in Athens, Theseus sailed off as one of the fourteen tributes dedicated to the Minotaur. According to some traditions, Theseus actually volunteered to go to Crete, vowing that he would kill the Minotaur and bring an end to the terrible tribute once and for all. [6]

The ship on which he and the other tributes embarked had a black sail; before the ship left for Crete, Aegeus made Theseus swear that if he managed to return alive he would have the black sail changed to a white one.

At Crete, Minos’ daughter Ariadne fell in love with Theseus and agreed to help him kill the Minotaur if he would take her with him to Athens. Before Theseus entered the Labyrinth, Ariadne gave him a ball of thread. Theseus unravelled the thread as he moved through the Labyrinth, killed the Minotaur, and found his way out of the Labyrinth by following the thread back to the exit. Theseus and Ariadne then escaped from Crete with the other tributes.

Detail of the Aison cup showing Theseus slaying the Minotaur in the presence of Athena (c. 435–415 BC).

On their journey back to Athens, Theseus stopped at the island of Naxos. There are different versions of what happened to Ariadne there. According to some, Theseus simply abandoned her. Another well-known story, however, claims that Dionysus fell in love with Ariadne while she was on Crete and carried her off for himself. In any case, Theseus arrived at Athens without Ariadne. [7]

Ariadne weeps as Theseus' ship leaves her on the island of Naxos. Roman fresco from Pompeii at Naples Archaeological Museum.

Whether distracted by the loss of Ariadne or for some other reason, Theseus forgot to raise the white flag as he came back to Athens. Aegeus, who was watching from a tower, saw the black flag and thought that his son had died.

Overcome by grief, Aegeus killed himself by leaping into the sea (this is the origin, according to the Greeks, of the name of the “Aegean Sea”). Theseus arrived to find his father dead and so became king of Athens.

The Amazons

Like many heroes of Greek mythology, Theseus waged war with the Amazons . The Amazons were a fierce race of warrior women who lived near the Black Sea or the Caucasus. Their queens were said to be the daughters of the war god Ares .

While among the Amazons, Theseus fell in love with their queen, Antiope (sometimes called Hippolyta), [8] and carried her off with him to Athens. The Amazons then attacked Athens in an attempt to get Antiope back. In some versions of the myth, the Amazons laid waste to the countryside of Attica and only left after Antiope was accidentally killed in battle. [9]

In other versions, Theseus tried to abandon Antiope so that he could marry Phaedra, a princess from Crete; when the jilted Antiope tried to stop the wedding, Theseus killed her himself. [10] In all versions of the story, however, Theseus finally managed to drive the Amazons away from Athens after the death of Antiope, though only after Antiope had given him a son named Hippolytus.

After the death of Antiope, Theseus married Phaedra, the daughter of the Cretan king Minos and thus the sister of his former lover Ariadne. Phaedra bore Theseus two children, Acamas and Demophon .

Roman mosaic of Phaedra and Hippolytus at House of Dionysus, Cyprus (ca. 3rd century CE).

Eventually, however, Phaedra fell in love with Hippolytus, the son of Theseus’ first wife, Antiope. Phaedra tried to convince Hippolytus to sleep with her. When he refused, Phaedra tore her clothing and falsely claimed that Hippolytus had raped her. Theseus was furious and prayed to Poseidon that Hippolytus might be punished.

Poseidon, unfortunately, heard Theseus’ prayer and sent a bull from the sea to charge Hippolytus as he was riding his chariot near the coast. Hippolytus’ horses were frightened; he lost control of the chariot, became entangled in the reins, and was trampled to death.

Theseus discovered his son’s innocence too late; Phaedra, ashamed and guilty, hanged herself. [11]

Abduction of Helen and Persephone

Theseus took part in several other adventures. Some sources include him among the Argonauts who sailed with Jason to retrieve the Golden Fleece, or with the heroes who took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt.

In many of these adventures, Theseus was accompanied by his best friend Pirithous , the king of the Lapiths of northern Greece. In one famous tradition, Theseus and Pirithous both vowed to marry daughters of Zeus. Theseus chose Helen, and Pirithous helped him abduct her from her father Tyndareus’ home in Sparta.

Pirithous then chose Persephone as his bride, even though she was already married to Hades . Theseus left Helen in the care of his mother, Aethra, while he and Pirithous went to the Underworld to abduct Persephone. Predictably, this did not end well. Theseus and Pirithous were caught trying to abduct Persephone and trapped in the Underworld.

While Theseus was away from Athens, Helen’s brothers, Castor and Polydeuces , retrieved her and took Aethra prisoner. Meanwhile, Theseus was eventually rescued from Hades by Heracles, but Pirithous remained trapped in eternal punishment for his impiety (in the most common version of the story). [12] When Theseus returned to Athens, he found that Helen was gone and that his mother had become her slave in Sparta.

Athenian Government and Death

Theseus was said to have been responsible for the synoikismos (“dwelling-together”), the political and cultural unification of the region of Attica under the rule of the city-state of Athens. In later times, some Athenians even traced the origins of democratic government to Theseus’ rule, even though Theseus was a king. Theseus was always seen as an important founding figure of Athenian history.

As an old man, Theseus fell out of favor in Athens. Driven into exile, he came to Scyrus, a small island in the Aegean Sea. It was in Scyrus that Theseus died. In some stories, he was thrown from a cliff by Lycomedes, the king of Scyrus. In 475 BCE, the Athenians claimed to have identified the remains of Theseus on Scyrus and brought them back to be reinterred in Athens.

Festivals and/or Holidays

The festival of Theseus, called the Theseia, was celebrated in Athens in the autumn. It was presided over by the Phytalidae, the hereditary priests of Theseus. The Phytalidae were said to have been the direct descendants of the fourteen tributes Theseus saved when he killed the Minotaur. [13] Little else is known of the festivals or worship of Theseus.

The hero-cult of Theseus was almost certainly concentrated solely in the city of Athens. The main sanctuary of Theseus, the Theseion, may have existed as early as the sixth century BCE. [14] It was most likely located at the center of Athens, in the vicinity of the Agora. Though the Theseion was probably the main center of Theseus’ hero-worship, little else is known about it, and there is still virtually no archaeological evidence of it. There were likely other sanctuaries of Theseus in Athens by the fourth century BCE.

Pop Culture

Theseus has had a rich afterlife in modern popular culture. The 2011 film Immortals is loosely based on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur; Theseus is portrayed by Henry Cavill. Theseus also features in the miniseries Helen of Troy (2003), in which he kidnaps Helen with his friend Pirithous.

The myths of Theseus are also retold in many modern books and novels. Mary Renault’s critically acclaimed The King Must Die (1958) is a historicized retelling of Theseus’ early life and his battle with the Minotaur; its sequel, The Bull from the Sea (1962), deals with Theseus’ later career. The myth of Theseus and Antiope is also reimagined in Steven Pressfield’s novel Last of the Amazons (2002).

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The House of Asterion (published in Spanish in 1947) presents an interesting variation on the myth of the Minotaur, told from the perspective of the Minotaur rather than Theseus. The myth of Theseus inspired Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy (2008–2010).

by Edith Hamilton

Mythology summary and analysis of theseus.

Theseus is the great Athenian hero. His father Aegeus is king of Athens, but Theseus grows up in southern Greece with his mother. When he is old enough, Theseus travels to the city to meet his father and overcomes many obstacles along the way. By the time he reaches Athens, he is known as a hero. Not realizing that Theseus is his son, King Aegeus is about to poison him, but just in time Theseus shows him a sword that his father left for him. Aegeus declares Theseus heir to the throne and sends him on an important journey.

Aegeus recounts the tragedy of Minos , the powerful ruler of Crete, who lost his only son Androgeus while the boy was in Athens. Aegeus had sent him on an expedition to kill a dangerous bull, but it killed Androgeus, and in revenge, King Minos vowed to destroy Athens unless every year seven maidens and seven men were sent to Crete. These sacrificial youth would be fed to the Minotaur , a monster, half-bull and half-human, who lived inside a labyrinth. Theseus comes forward to be offered as one of the victims. He promises his father that he will kill the Minotaur, and upon his successful return, his ship will carry a white sail.

When the fourteen men and women arrive in Crete, they are paraded through the town. Minos's daughter Ariadne sees and instantly falls in love with Theseus. She confers with Daedalus the architect to devise a plan for her beloved to stay safe. Then she meets with Theseus, who promises to marry her if he escapes from the labyrinth. Theseus follows Ariadne's plan, walking through the maze as he lets run a ball of string so he can retrace his steps. Theseus finds the Minotaur sleeping and kills it with his bare hands. Theseus, Ariadne, and the other Athenian youth all escape to the ship going back to Athens.

On the way back, Ariadne dies. Some say Theseus deserted her on an island. Others say he let her rest on an island because she was seasick, then got caught in a storm, and by the time he returned to the island she was dead. In any case, for some reason Theseus forgets to raise the white sail. His father, seeing the black sail, assumes his son has died and jumps into the sea. The sea has been called the Aegean ever since.

Theseus rules in a people-friendly fashion, and Athens becomes the happiest city in the world. In later years, however, sadness ensues after he marries Ariadne's sister Phaedra . Theseus already had a child, Hippolytus . When Theseus and Phaedra visit him, Phaedra falls madly in love with Hippolytus, her stepson. He refuses her advances, but she writes a letter falsely alleging that he violated her, and then she kills herself. Theseus finds the letter and banishes his innocent son. Artemis appears to Theseus and reveals the truth, but it is too late because the boy has already been killed at sea.

The story of Theseus is one of the most famous tales of Greek mythology. Indeed, Theseus is one of the best examples of a Greek hero. Not only does he use cunning and strength to kill the Minotaur, but he also works to reunite his family and his kingdom. He goes on to become a monarch who serves his people well. This myth also illuminates the perception that Athens was, in its day, the most respected and just land. The government of justice that Theseus oversaw became an idealized model for Greek and Roman culture throughout history.

The story's tragic end, however, suggests the fragility of goodness and mortal happiness even for a hero like Theseus. Like Bellerophon , he becomes a more complex character as the end of his life becomes more complex than its clearly heroic beginnings. Between Ariadne's death, Aegeus's suicide, and the Phaedra tragedy, Theseus becomes a complicated figure who outgrows his earlier, simpler role of hero.

The tale of Phaedra and Hippolytus may illustrate some of the gendered power relations in ancient Greek life. It was reasonable to imagine that a woman at that time might kill herself after being raped. Phaedra takes advantage of that expectation in revenge, being so distraught over her failure to seduce Hippolytus that she is willing both to kill herself and to ruin his life. Contrast this relationship to that of Theseus and Ariadne; without her, he could not have escaped the labyrinth.

Indeed, the relationship between Ariadne and Theseus is an interesting one as it speaks to the recurring theme of true love. Although in the beginning it seems as if these two lovers have found the true love that the gods support, Hamilton puts that idea into doubt when she reports the idea that Theseus may have left her on an island to die. Although such an action would seem out of place for his character, the alternative suggestion is that Ariadne died because he left her on an island for too long. When he marries her sister, tragic events unfold, and it seems that fate did not look happily on the affair. True love, it seems, is not simple at all--it can cause all kinds of trouble and lead to all kinds of quests and adventures.

The tragedy of Aegeus brings up the recurring theme of a tragic mistake. When Theseus forgets to raise the correct flag, his carelessness takes a fatal turn against someone he loves. Like Apollo killing his best friend Hyacinthus , Theseus clearly means well but makes a tragic mistake. Unlike the other fathers who lose sons, Aegeus is so distraught that he chooses to die himself.

Like the story of Perseus , the tales of Theseus take on an adventurous tone with epic proportions. From the Labyrinth to the Minotaur, Ariadne to Aegeus, the tales of Theseus have become iconic in the Western canon.

Mythology Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Mythology is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

How does Perseus respond to people and events in the story? How does this response move the story forward?

Which specific myth are you referring to? Title, please?

What drink is given to Polyphemus ? What is the Effect?

The give Polyphemus wine. He falls asleep.

3 gods of goddness

Whatbparticular myth are you referring to?

Study Guide for Mythology

The Mythology study guide contains a biography of Edith Hamilton, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis of the major Greek myths and Western mythology.

- About Mythology

- Mythology Summary

- Character List

Lesson Plan for Mythology

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Mythology

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Mythology Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for Mythology

- Introduction

- Dictionary entries

- Quote, rate & share

- Meaning of θέσις

θέσις ( Ancient Greek)

Origin & history.

- a setting , placement , arrangement

- adoption (of a child)

- adoption (in the more general sense of accepting as one's own)

- ( philosophy ) position , conclusion , thesis

- ( dancing ) putting down the foot

- ( metre ) the last half of the foot

- ( rhetoric ) affirmation

- ( grammar ) stop

▾ Derived words & phrases

- ἀντεπίθεσις

- ἀντιμετάθεσις

- ἀντιπαράθεσις

- ἐπιπρόσθεσις

- ἐπισύνθεσις

- ἡμισύνθεσις

- προδιάθεσις

- συγκατάθεσις

- συναντίθεσις

- συνεπίθεσις

▾ Descendants

- Latin: thesis

▾ Dictionary entries

Entries where "θέσις" occurs:

thesis : thesis (English) Origin & history From Latin thesis, from Ancient Greek θέσις ("a proposition, a statement, a thing laid down, thesis in rhetoric, thesis in prosody") Pronunciation IPA: /ˈθiːsɪs/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Rhymes:…

deed : …action"), Swedish and Danish dåd ("act, action"). The Proto-Indo-European root is also the source of Ancient Greek θέσις ("setting, arrangement"). Related to do. Pronunciation IPA: /diːd/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Rhymes:…

tes : …Origin & history I Noun tes Indefinite genitive singular of te Origin & history II From Latin thesis and Ancient Greek θέσις ("a proposition, a statement"), used in Swedish since 1664. Noun tes (common gender) a thesis, a statement…

Tat : …Low German Daat, Dutch daad, English deed, Danish dåd, Gothic 𐌳𐌴𐌸𐍃, and Ancient Greek θέσις ("arrangement"). Pronunciation IPA: /taːt/ Rhymes: -aːt Homophones: tat Noun Tat (fem.) (genitive Tat…

antithesis : antithesis (English) Origin & history From Ancient Greek ἀντί ("against") + θέσις ("position"). Surface analysis anti- + thesis. Pronunciation (Amer. Eng.) IPA: /ænˈtɪ.θə.sɪs/ Pronunciation example: Audio (US) Examples:…

Quote, Rate & Share