A statement that could be true, which might then be tested.

Example: Sam has a hypothesis that "large dogs are better at catching tennis balls than small dogs". We can test that hypothesis by having hundreds of different sized dogs try to catch tennis balls.

Sometimes the hypothesis won't be tested, it is simply a good explanation (which could be wrong). Conjecture is a better word for this.

Example: you notice the temperature drops just as the sun rises. Your hypothesis is that the sun warms the air high above you, which rises up and then cooler air comes from the sides.

Note: when someone says "I have a theory" they should say "I have a hypothesis", because in mathematics a theory is actually well proven.

A hypothesis is a proposition that is consistent with known data, but has been neither verified nor shown to be false.

In statistics, a hypothesis (sometimes called a statistical hypothesis) refers to a statement on which hypothesis testing will be based. Particularly important statistical hypotheses include the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis .

In symbolic logic , a hypothesis is the first part of an implication (with the second part being known as the predicate ).

In general mathematical usage, "hypothesis" is roughly synonymous with " conjecture ."

Explore with Wolfram|Alpha

More things to try:

- 100011010 base 2

- extrema calculator

Cite this as:

Weisstein, Eric W. "Hypothesis." From MathWorld --A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/Hypothesis.html

Subject classifications

- Math Article

Hypothesis Definition

In Statistics, the determination of the variation between the group of data due to true variation is done by hypothesis testing. The sample data are taken from the population parameter based on the assumptions. The hypothesis can be classified into various types. In this article, let us discuss the hypothesis definition, various types of hypothesis and the significance of hypothesis testing, which are explained in detail.

Hypothesis Definition in Statistics

In Statistics, a hypothesis is defined as a formal statement, which gives the explanation about the relationship between the two or more variables of the specified population. It helps the researcher to translate the given problem to a clear explanation for the outcome of the study. It clearly explains and predicts the expected outcome. It indicates the types of experimental design and directs the study of the research process.

Types of Hypothesis

The hypothesis can be broadly classified into different types. They are:

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis that there exists a relationship between two variables. One is called a dependent variable, and the other is called an independent variable.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is used when there is a relationship between the existing variables. In this hypothesis, the dependent and independent variables are more than two.

Null Hypothesis

In the null hypothesis, there is no significant difference between the populations specified in the experiments, due to any experimental or sampling error. The null hypothesis is denoted by H 0 .

Alternative Hypothesis

In an alternative hypothesis, the simple observations are easily influenced by some random cause. It is denoted by the H a or H 1 .

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is formed by the experiments and based on the evidence.

Statistical Hypothesis

In a statistical hypothesis, the statement should be logical or illogical, and the hypothesis is verified statistically.

Apart from these types of hypothesis, some other hypotheses are directional and non-directional hypothesis, associated hypothesis, casual hypothesis.

Characteristics of Hypothesis

The important characteristics of the hypothesis are:

- The hypothesis should be short and precise

- It should be specific

- A hypothesis must be related to the existing body of knowledge

- It should be capable of verification

To learn more Maths definitions, register with BYJU’S – The Learning App.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Maths related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.1: Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10211

- Kyle Siegrist

- University of Alabama in Huntsville via Random Services

Basic Theory

Preliminaries.

As usual, our starting point is a random experiment with an underlying sample space and a probability measure \(\P\). In the basic statistical model, we have an observable random variable \(\bs{X}\) taking values in a set \(S\). In general, \(\bs{X}\) can have quite a complicated structure. For example, if the experiment is to sample \(n\) objects from a population and record various measurements of interest, then \[ \bs{X} = (X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n) \] where \(X_i\) is the vector of measurements for the \(i\)th object. The most important special case occurs when \((X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n)\) are independent and identically distributed. In this case, we have a random sample of size \(n\) from the common distribution.

The purpose of this section is to define and discuss the basic concepts of statistical hypothesis testing . Collectively, these concepts are sometimes referred to as the Neyman-Pearson framework, in honor of Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson, who first formalized them.

A statistical hypothesis is a statement about the distribution of \(\bs{X}\). Equivalently, a statistical hypothesis specifies a set of possible distributions of \(\bs{X}\): the set of distributions for which the statement is true. A hypothesis that specifies a single distribution for \(\bs{X}\) is called simple ; a hypothesis that specifies more than one distribution for \(\bs{X}\) is called composite .

In hypothesis testing , the goal is to see if there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject a presumed null hypothesis in favor of a conjectured alternative hypothesis . The null hypothesis is usually denoted \(H_0\) while the alternative hypothesis is usually denoted \(H_1\).

An hypothesis test is a statistical decision ; the conclusion will either be to reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative, or to fail to reject the null hypothesis. The decision that we make must, of course, be based on the observed value \(\bs{x}\) of the data vector \(\bs{X}\). Thus, we will find an appropriate subset \(R\) of the sample space \(S\) and reject \(H_0\) if and only if \(\bs{x} \in R\). The set \(R\) is known as the rejection region or the critical region . Note the asymmetry between the null and alternative hypotheses. This asymmetry is due to the fact that we assume the null hypothesis, in a sense, and then see if there is sufficient evidence in \(\bs{x}\) to overturn this assumption in favor of the alternative.

An hypothesis test is a statistical analogy to proof by contradiction, in a sense. Suppose for a moment that \(H_1\) is a statement in a mathematical theory and that \(H_0\) is its negation. One way that we can prove \(H_1\) is to assume \(H_0\) and work our way logically to a contradiction. In an hypothesis test, we don't prove anything of course, but there are similarities. We assume \(H_0\) and then see if the data \(\bs{x}\) are sufficiently at odds with that assumption that we feel justified in rejecting \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_1\).

Often, the critical region is defined in terms of a statistic \(w(\bs{X})\), known as a test statistic , where \(w\) is a function from \(S\) into another set \(T\). We find an appropriate rejection region \(R_T \subseteq T\) and reject \(H_0\) when the observed value \(w(\bs{x}) \in R_T\). Thus, the rejection region in \(S\) is then \(R = w^{-1}(R_T) = \left\{\bs{x} \in S: w(\bs{x}) \in R_T\right\}\). As usual, the use of a statistic often allows significant data reduction when the dimension of the test statistic is much smaller than the dimension of the data vector.

The ultimate decision may be correct or may be in error. There are two types of errors, depending on which of the hypotheses is actually true.

Types of errors:

- A type 1 error is rejecting the null hypothesis \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is true.

- A type 2 error is failing to reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) when the alternative hypothesis \(H_1\) is true.

Similarly, there are two ways to make a correct decision: we could reject \(H_0\) when \(H_1\) is true or we could fail to reject \(H_0\) when \(H_0\) is true. The possibilities are summarized in the following table:

Of course, when we observe \(\bs{X} = \bs{x}\) and make our decision, either we will have made the correct decision or we will have committed an error, and usually we will never know which of these events has occurred. Prior to gathering the data, however, we can consider the probabilities of the various errors.

If \(H_0\) is true (that is, the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_0\)), then \(\P(\bs{X} \in R)\) is the probability of a type 1 error for this distribution. If \(H_0\) is composite, then \(H_0\) specifies a variety of different distributions for \(\bs{X}\) and thus there is a set of type 1 error probabilities.

The maximum probability of a type 1 error, over the set of distributions specified by \( H_0 \), is the significance level of the test or the size of the critical region.

The significance level is often denoted by \(\alpha\). Usually, the rejection region is constructed so that the significance level is a prescribed, small value (typically 0.1, 0.05, 0.01).

If \(H_1\) is true (that is, the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_1\)), then \(\P(\bs{X} \notin R)\) is the probability of a type 2 error for this distribution. Again, if \(H_1\) is composite then \(H_1\) specifies a variety of different distributions for \(\bs{X}\), and thus there will be a set of type 2 error probabilities. Generally, there is a tradeoff between the type 1 and type 2 error probabilities. If we reduce the probability of a type 1 error, by making the rejection region \(R\) smaller, we necessarily increase the probability of a type 2 error because the complementary region \(S \setminus R\) is larger.

The extreme cases can give us some insight. First consider the decision rule in which we never reject \(H_0\), regardless of the evidence \(\bs{x}\). This corresponds to the rejection region \(R = \emptyset\). A type 1 error is impossible, so the significance level is 0. On the other hand, the probability of a type 2 error is 1 for any distribution defined by \(H_1\). At the other extreme, consider the decision rule in which we always rejects \(H_0\) regardless of the evidence \(\bs{x}\). This corresponds to the rejection region \(R = S\). A type 2 error is impossible, but now the probability of a type 1 error is 1 for any distribution defined by \(H_0\). In between these two worthless tests are meaningful tests that take the evidence \(\bs{x}\) into account.

If \(H_1\) is true, so that the distribution of \(\bs{X}\) is specified by \(H_1\), then \(\P(\bs{X} \in R)\), the probability of rejecting \(H_0\) is the power of the test for that distribution.

Thus the power of the test for a distribution specified by \( H_1 \) is the probability of making the correct decision.

Suppose that we have two tests, corresponding to rejection regions \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), respectively, each having significance level \(\alpha\). The test with region \(R_1\) is uniformly more powerful than the test with region \(R_2\) if \[ \P(\bs{X} \in R_1) \ge \P(\bs{X} \in R_2) \text{ for every distribution of } \bs{X} \text{ specified by } H_1 \]

Naturally, in this case, we would prefer the first test. Often, however, two tests will not be uniformly ordered; one test will be more powerful for some distributions specified by \(H_1\) while the other test will be more powerful for other distributions specified by \(H_1\).

If a test has significance level \(\alpha\) and is uniformly more powerful than any other test with significance level \(\alpha\), then the test is said to be a uniformly most powerful test at level \(\alpha\).

Clearly a uniformly most powerful test is the best we can do.

\(P\)-value

In most cases, we have a general procedure that allows us to construct a test (that is, a rejection region \(R_\alpha\)) for any given significance level \(\alpha \in (0, 1)\). Typically, \(R_\alpha\) decreases (in the subset sense) as \(\alpha\) decreases.

The \(P\)-value of the observed value \(\bs{x}\) of \(\bs{X}\), denoted \(P(\bs{x})\), is defined to be the smallest \(\alpha\) for which \(\bs{x} \in R_\alpha\); that is, the smallest significance level for which \(H_0\) is rejected, given \(\bs{X} = \bs{x}\).

Knowing \(P(\bs{x})\) allows us to test \(H_0\) at any significance level for the given data \(\bs{x}\): If \(P(\bs{x}) \le \alpha\) then we would reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\); if \(P(\bs{x}) \gt \alpha\) then we fail to reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\). Note that \(P(\bs{X})\) is a statistic . Informally, \(P(\bs{x})\) can often be thought of as the probability of an outcome as or more extreme than the observed value \(\bs{x}\), where extreme is interpreted relative to the null hypothesis \(H_0\).

Analogy with Justice Systems

There is a helpful analogy between statistical hypothesis testing and the criminal justice system in the US and various other countries. Consider a person charged with a crime. The presumed null hypothesis is that the person is innocent of the crime; the conjectured alternative hypothesis is that the person is guilty of the crime. The test of the hypotheses is a trial with evidence presented by both sides playing the role of the data. After considering the evidence, the jury delivers the decision as either not guilty or guilty . Note that innocent is not a possible verdict of the jury, because it is not the point of the trial to prove the person innocent. Rather, the point of the trial is to see whether there is sufficient evidence to overturn the null hypothesis that the person is innocent in favor of the alternative hypothesis of that the person is guilty. A type 1 error is convicting a person who is innocent; a type 2 error is acquitting a person who is guilty. Generally, a type 1 error is considered the more serious of the two possible errors, so in an attempt to hold the chance of a type 1 error to a very low level, the standard for conviction in serious criminal cases is beyond a reasonable doubt .

Tests of an Unknown Parameter

Hypothesis testing is a very general concept, but an important special class occurs when the distribution of the data variable \(\bs{X}\) depends on a parameter \(\theta\) taking values in a parameter space \(\Theta\). The parameter may be vector-valued, so that \(\bs{\theta} = (\theta_1, \theta_2, \ldots, \theta_n)\) and \(\Theta \subseteq \R^k\) for some \(k \in \N_+\). The hypotheses generally take the form \[ H_0: \theta \in \Theta_0 \text{ versus } H_1: \theta \notin \Theta_0 \] where \(\Theta_0\) is a prescribed subset of the parameter space \(\Theta\). In this setting, the probabilities of making an error or a correct decision depend on the true value of \(\theta\). If \(R\) is the rejection region, then the power function \( Q \) is given by \[ Q(\theta) = \P_\theta(\bs{X} \in R), \quad \theta \in \Theta \] The power function gives a lot of information about the test.

The power function satisfies the following properties:

- \(Q(\theta)\) is the probability of a type 1 error when \(\theta \in \Theta_0\).

- \(\max\left\{Q(\theta): \theta \in \Theta_0\right\}\) is the significance level of the test.

- \(1 - Q(\theta)\) is the probability of a type 2 error when \(\theta \notin \Theta_0\).

- \(Q(\theta)\) is the power of the test when \(\theta \notin \Theta_0\).

If we have two tests, we can compare them by means of their power functions.

Suppose that we have two tests, corresponding to rejection regions \(R_1\) and \(R_2\), respectively, each having significance level \(\alpha\). The test with rejection region \(R_1\) is uniformly more powerful than the test with rejection region \(R_2\) if \( Q_1(\theta) \ge Q_2(\theta)\) for all \( \theta \notin \Theta_0 \).

Most hypothesis tests of an unknown real parameter \(\theta\) fall into three special cases:

Suppose that \( \theta \) is a real parameter and \( \theta_0 \in \Theta \) a specified value. The tests below are respectively the two-sided test , the left-tailed test , and the right-tailed test .

- \(H_0: \theta = \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0\)

- \(H_0: \theta \ge \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \lt \theta_0\)

- \(H_0: \theta \le \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \gt \theta_0\)

Thus the tests are named after the conjectured alternative. Of course, there may be other unknown parameters besides \(\theta\) (known as nuisance parameters ).

Equivalence Between Hypothesis Test and Confidence Sets

There is an equivalence between hypothesis tests and confidence sets for a parameter \(\theta\).

Suppose that \(C(\bs{x})\) is a \(1 - \alpha\) level confidence set for \(\theta\). The following test has significance level \(\alpha\) for the hypothesis \( H_0: \theta = \theta_0 \) versus \( H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0 \): Reject \(H_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \notin C(\bs{x})\)

By definition, \(\P[\theta \in C(\bs{X})] = 1 - \alpha\). Hence if \(H_0\) is true so that \(\theta = \theta_0\), then the probability of a type 1 error is \(P[\theta \notin C(\bs{X})] = \alpha\).

Equivalently, we fail to reject \(H_0\) at significance level \(\alpha\) if and only if \(\theta_0\) is in the corresponding \(1 - \alpha\) level confidence set. In particular, this equivalence applies to interval estimates of a real parameter \(\theta\) and the common tests for \(\theta\) given above .

In each case below, the confidence interval has confidence level \(1 - \alpha\) and the test has significance level \(\alpha\).

- Suppose that \(\left[L(\bs{X}, U(\bs{X})\right]\) is a two-sided confidence interval for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta = \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \ne \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \lt L(\bs{X})\) or \(\theta_0 \gt U(\bs{X})\).

- Suppose that \(L(\bs{X})\) is a confidence lower bound for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta \le \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \gt \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \lt L(\bs{X})\).

- Suppose that \(U(\bs{X})\) is a confidence upper bound for \(\theta\). Reject \(H_0: \theta \ge \theta_0\) versus \(H_1: \theta \lt \theta_0\) if and only if \(\theta_0 \gt U(\bs{X})\).

Pivot Variables and Test Statistics

Recall that confidence sets of an unknown parameter \(\theta\) are often constructed through a pivot variable , that is, a random variable \(W(\bs{X}, \theta)\) that depends on the data vector \(\bs{X}\) and the parameter \(\theta\), but whose distribution does not depend on \(\theta\) and is known. In this case, a natural test statistic for the basic tests given above is \(W(\bs{X}, \theta_0)\).

Professor: Erika L.C. King Email: [email protected] Office: Lansing 304 Phone: (315)781-3355

The majority of statements in mathematics can be written in the form: "If A, then B." For example: "If a function is differentiable, then it is continuous". In this example, the "A" part is "a function is differentiable" and the "B" part is "a function is continuous." The "A" part of the statement is called the "hypothesis", and the "B" part of the statement is called the "conclusion". Thus the hypothesis is what we must assume in order to be positive that the conclusion will hold.

Whenever you are asked to state a theorem, be sure to include the hypothesis. In order to know when you may apply the theorem, you need to know what constraints you have. So in the example above, if we know that a function is differentiable, we may assume that it is continuous. However, if we do not know that a function is differentiable, continuity may not hold. Some theorems have MANY hypotheses, some of which are written in sentences before the ultimate "if, then" statement. For example, there might be a sentence that says: "Assume n is even." which is then followed by an if,then statement. Include all hypotheses and assumptions when asked to state theorems and definitions!

Still have questions? Please ask!

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

- The Number System and Place Value

- Calculations and Numerical Methods

- Fractions, Decimals, Percentages, Ratio and Proportion

- Properties of Numbers

- Patterns, Sequences and Structure

- Algebraic expressions, equations and formulae

- Coordinates, Functions and Graphs

Geometry and measure

- Angles, Polygons, and Geometrical Proof

- 3D Geometry, Shape and Space

- Measuring and calculating with units

- Transformations and constructions

- Pythagoras and Trigonometry

- Vectors and Matrices

Probability and statistics

- Handling, Processing and Representing Data

- Probability

Working mathematically

- Thinking mathematically

- Mathematical mindsets

- Cross-curricular contexts

- Physical and digital manipulatives

For younger learners

- Early Years Foundation Stage

Advanced mathematics

- Decision Mathematics and Combinatorics

- Advanced Probability and Statistics

Published 2008 Revised 2019

Understanding Hypotheses

'What happens if ... ?' to ' This will happen if'

The experimentation of children continually moves on to the exploration of new ideas and the refinement of their world view of previously understood situations. This description of the playtime patterns of young children very nicely models the concept of 'making and testing hypotheses'. It follows this pattern:

- Make some observations. Collect some data based on the observations.

- Draw a conclusion (called a 'hypothesis') which will explain the pattern of the observations.

- Test out your hypothesis by making some more targeted observations.

So, we have

- A hypothesis is a statement or idea which gives an explanation to a series of observations.

Sometimes, following observation, a hypothesis will clearly need to be refined or rejected. This happens if a single contradictory observation occurs. For example, suppose that a child is trying to understand the concept of a dog. He reads about several dogs in children's books and sees that they are always friendly and fun. He makes the natural hypothesis in his mind that dogs are friendly and fun . He then meets his first real dog: his neighbour's puppy who is great fun to play with. This reinforces his hypothesis. His cousin's dog is also very friendly and great fun. He meets some of his friends' dogs on various walks to playgroup. They are also friendly and fun. He is now confident that his hypothesis is sound. Suddenly, one day, he sees a dog, tries to stroke it and is bitten. This experience contradicts his hypothesis. He will need to amend the hypothesis. We see that

- Gathering more evidence/data can strengthen a hypothesis if it is in agreement with the hypothesis.

- If the data contradicts the hypothesis then the hypothesis must be rejected or amended to take into account the contradictory situation.

- A contradictory observation can cause us to know for certain that a hypothesis is incorrect.

- Accumulation of supporting experimental evidence will strengthen a hypothesis but will never let us know for certain that the hypothesis is true.

In short, it is possible to show that a hypothesis is false, but impossible to prove that it is true!

Whilst we can never prove a scientific hypothesis to be true, there will be a certain stage at which we decide that there is sufficient supporting experimental data for us to accept the hypothesis. The point at which we make the choice to accept a hypothesis depends on many factors. In practice, the key issues are

- What are the implications of mistakenly accepting a hypothesis which is false?

- What are the cost / time implications of gathering more data?

- What are the implications of not accepting in a timely fashion a true hypothesis?

For example, suppose that a drug company is testing a new cancer drug. They hypothesise that the drug is safe with no side effects. If they are mistaken in this belief and release the drug then the results could have a disastrous effect on public health. However, running extended clinical trials might be very costly and time consuming. Furthermore, a delay in accepting the hypothesis and releasing the drug might also have a negative effect on the health of many people.

In short, whilst we can never achieve absolute certainty with the testing of hypotheses, in order to make progress in science or industry decisions need to be made. There is a fine balance to be made between action and inaction.

Hypotheses and mathematics So where does mathematics enter into this picture? In many ways, both obvious and subtle:

- A good hypothesis needs to be clear, precisely stated and testable in some way. Creation of these clear hypotheses requires clear general mathematical thinking.

- The data from experiments must be carefully analysed in relation to the original hypothesis. This requires the data to be structured, operated upon, prepared and displayed in appropriate ways. The levels of this process can range from simple to exceedingly complex.

Very often, the situation under analysis will appear to be complicated and unclear. Part of the mathematics of the task will be to impose a clear structure on the problem. The clarity of thought required will actively be developed through more abstract mathematical study. Those without sufficient general mathematical skill will be unable to perform an appropriate logical analysis.

Using deductive reasoning in hypothesis testing

There is often confusion between the ideas surrounding proof, which is mathematics, and making and testing an experimental hypothesis, which is science. The difference is rather simple:

- Mathematics is based on deductive reasoning : a proof is a logical deduction from a set of clear inputs.

- Science is based on inductive reasoning : hypotheses are strengthened or rejected based on an accumulation of experimental evidence.

Of course, to be good at science, you need to be good at deductive reasoning, although experts at deductive reasoning need not be mathematicians. Detectives, such as Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot, are such experts: they collect evidence from a crime scene and then draw logical conclusions from the evidence to support the hypothesis that, for example, Person M. committed the crime. They use this evidence to create sufficiently compelling deductions to support their hypotheses beyond reasonable doubt . The key word here is 'reasonable'. There is always the possibility of creating an exceedingly outlandish scenario to explain away any hypothesis of a detective or prosecution lawyer, but judges and juries in courts eventually make the decision that the probability of such eventualities are 'small' and the chance of the hypothesis being correct 'high'.

- If a set of data is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation 0.5 then there is a 97.7% certainty that a measurement will not exceed 1.0.

- If the mean of a sample of data is 12, how confident can we be that the true mean of the population lies between 11 and 13?

It is at this point that making and testing hypotheses becomes a true branch of mathematics. This mathematics is difficult, but fascinating and highly relevant in the information-rich world of today.

To read more about the technical side of hypothesis testing, take a look at What is a Hypothesis Test?

You might also enjoy reading the articles on statistics on the Understanding Uncertainty website

This resource is part of the collection Statistics - Maths of Real Life

- Mathematicians

- Math Lessons

- Square Roots

- Math Calculators

- Hypothesis | Definition & Meaning

JUMP TO TOPIC

Explanation of Hypothesis

Contradiction, simple hypothesis, complex hypothesis, null hypothesis, alternative hypothesis, empirical hypothesis, statistical hypothesis, special example of hypothesis, solution part (a), solution part (b), hypothesis|definition & meaning.

A hypothesis is a claim or statement that makes sense in the context of some information or data at hand but hasn’t been established as true or false through experimentation or proof.

In mathematics, any statement or equation that describes some relationship between certain variables can be termed as hypothesis if it is consistent with some initial supporting data or information, however, its yet to be proven true or false by some definite and trustworthy experiment or mathematical law.

Following example illustrates one such hypothesis to shed some light on this very fundamental concept which is often used in different areas of mathematics.

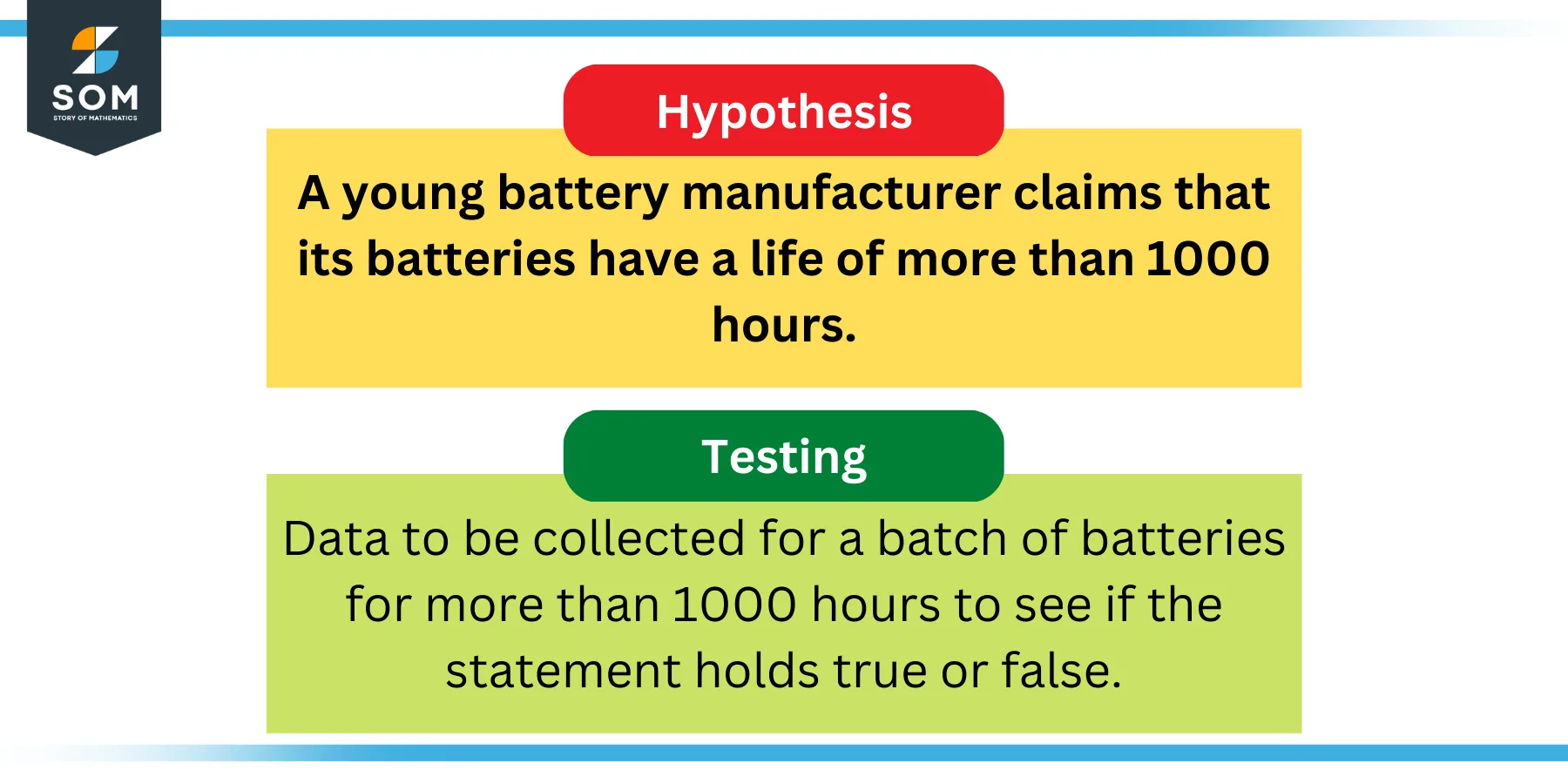

Figure 1: Example of Hypothesis

Here we have considered an example of a young startup company that manufactures state of the art batteries. The hypothesis or the claim of the company is that their batteries have a mean life of more than 1000 hours. Now its very easy to understand that they can prove their claim on some testing experiment in their lab.

However, the statement can only be proven if and only if at least one batch of their production batteries have actually been deployed in the real world for more than 1000 hours . After 1000 hours, data needs to be collected and it needs to be seen what is the probability of this statement being true .

The following paragraphs further explain this concept.

As explained with the help of an example earlier, a hypothesis in mathematics is an untested claim that is backed up by all the known data or some other discoveries or some weak experiments.

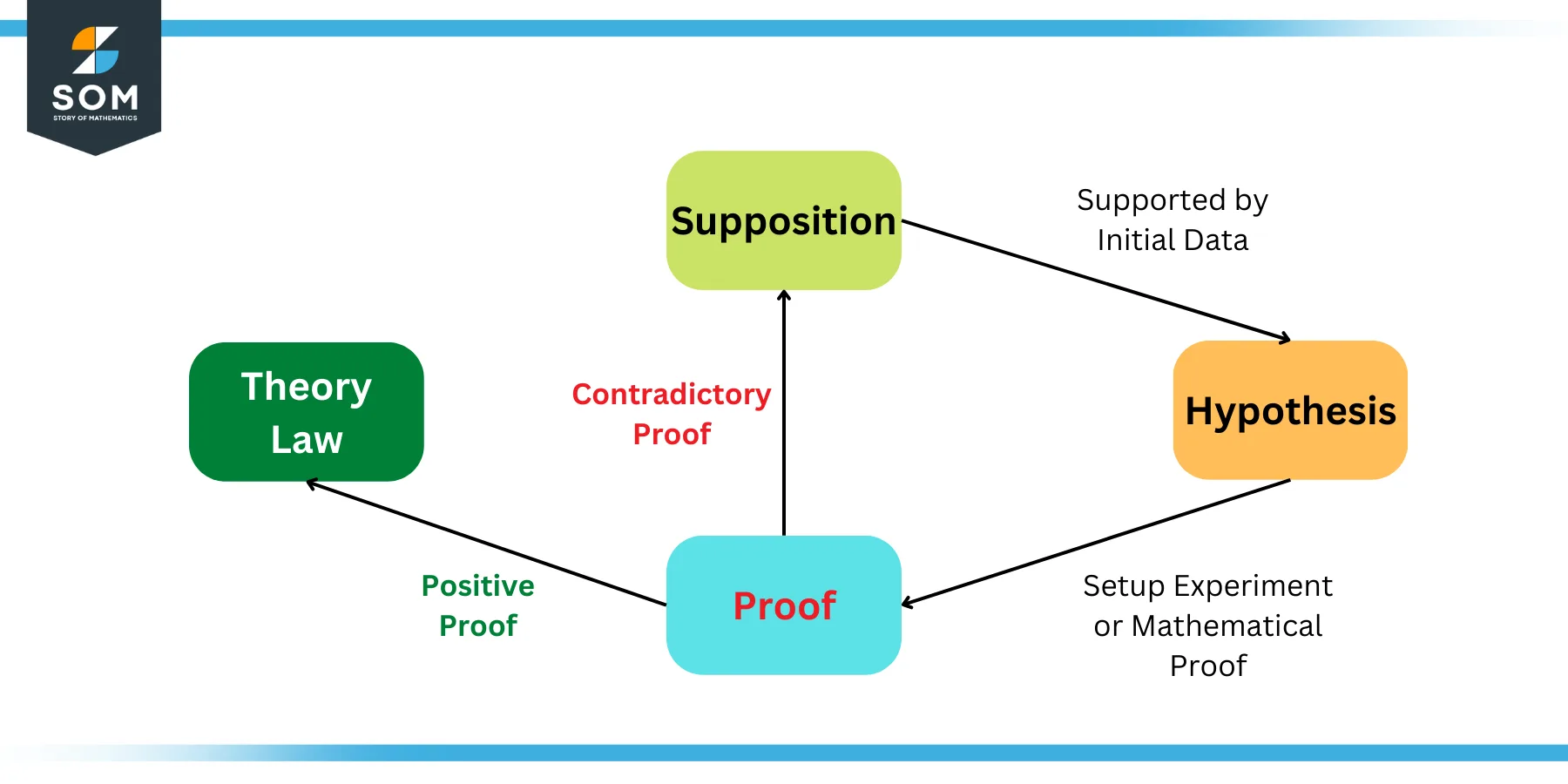

In any mathematical discovery, we first start by assuming something or some relationship . This supposed statement is called a supposition. A supposition, however, becomes a hypothesis when it is supported by all available data and a large number of contradictory findings.

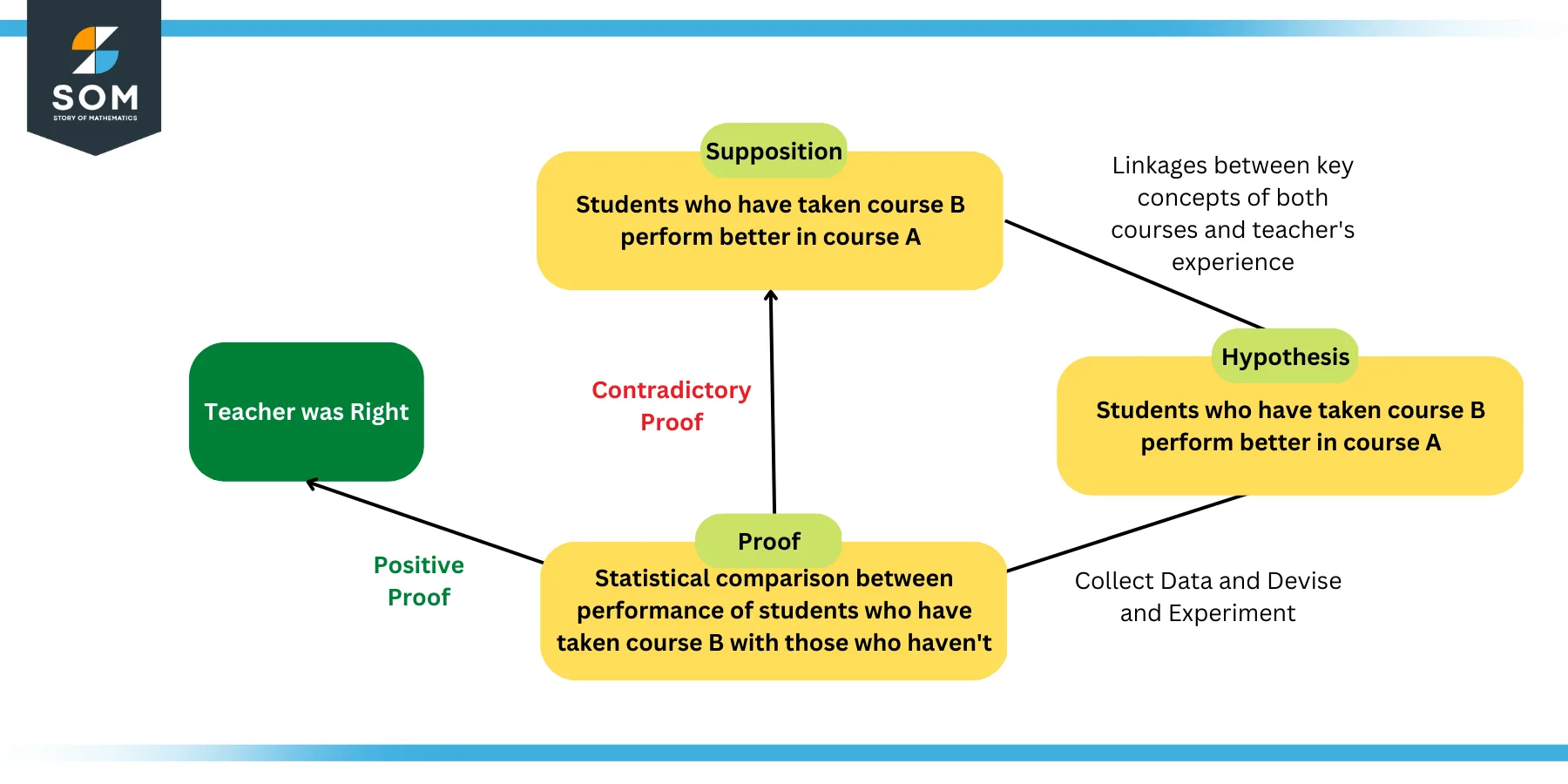

The hypothesis is an important part of the scientific method that is widely known today for making new discoveries. The field of mathematics inherited this process. Following figure shows this cycle as a graphic:

Figure 2: Role of Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

The above figure shows a simplified version of the scientific method. It shows that whenever a supposition is supported by some data, its termed as hypothesis. Once a hypothesis is proven by some well known and widely acceptable experiment or proof, its becomes a law. If the hypothesis is rejected by some contradictory results then the supposition is changed and the cycle continues.

Lets try to understand the scientific method and the hypothesis concept with the help of an example. Lets say that a teacher wanted to analyze the relationship between the students performance in a certain subject, lets call it A, based on whether or not they studied a minor course, lets call it B.

Now the teacher puts forth a supposition that the students taking the course B prior to course A must perform better in the latter due to the obvious linkages in the key concepts. Due to this linkage, this supposition can be termed as a hypothesis.

However to test the hypothesis, the teacher has to collect data from all of his/her students such that he/she knows which students have taken course B and which ones haven’t. Then at the end of the semester, the performance of the students must be measured and compared with their course B enrollments.

If the students that took course B prior to course A perform better, then the hypothesis concludes successful . Otherwise, the supposition may need revision.

The following figure explains this problem graphically.

Figure 3: Teacher and Course Example of Hypothesis

Important Terms Related to Hypothesis

To further elaborate the concept of hypothesis, we first need to understand a few key terms that are widely used in this area such as conjecture, contradiction and some special types of hypothesis (simple, complex, null, alternative, empirical, statistical). These terms are briefly explained below:

A conjecture is a term used to describe a mathematical assertion that has notbeenproved. While testing may occasionally turn up millions of examples in favour of a conjecture, most experts in the area will typically only accept a proof . In mathematics, this term is synonymous to the term hypothesis.

In mathematics, a contradiction occurs if the results of an experiment or proof are against some hypothesis. In other words, a contradiction discredits a hypothesis.

A simple hypothesis is such a type of hypothesis that claims there is a correlation between two variables. The first is known as a dependent variable while the second is known as an independent variable.

A complex hypothesis is such a type of hypothesis that claims there is a correlation between more than two variables. Both the dependent and independent variables in this hypothesis may be more than one in numbers.

A null hypothesis, usually denoted by H0, is such a type of hypothesis that claims there is no statistical relationship and significance between two sets of observed data and measured occurrences for each set of defined, single observable variables. In short the variables are independent.

An alternative hypothesis, usually denoted by H1 or Ha, is such a type of hypothesis where the variables may be statistically influenced by some unknown factors or variables. In short the variables are dependent on some unknown phenomena .

An Empirical hypothesis is such a type of hypothesis that is built on top of some empirical data or experiment or formulation.

A statistical hypothesis is such a type of hypothesis that is built on top of some statistical data or experiment or formulation. It may be logical or illogical in nature.

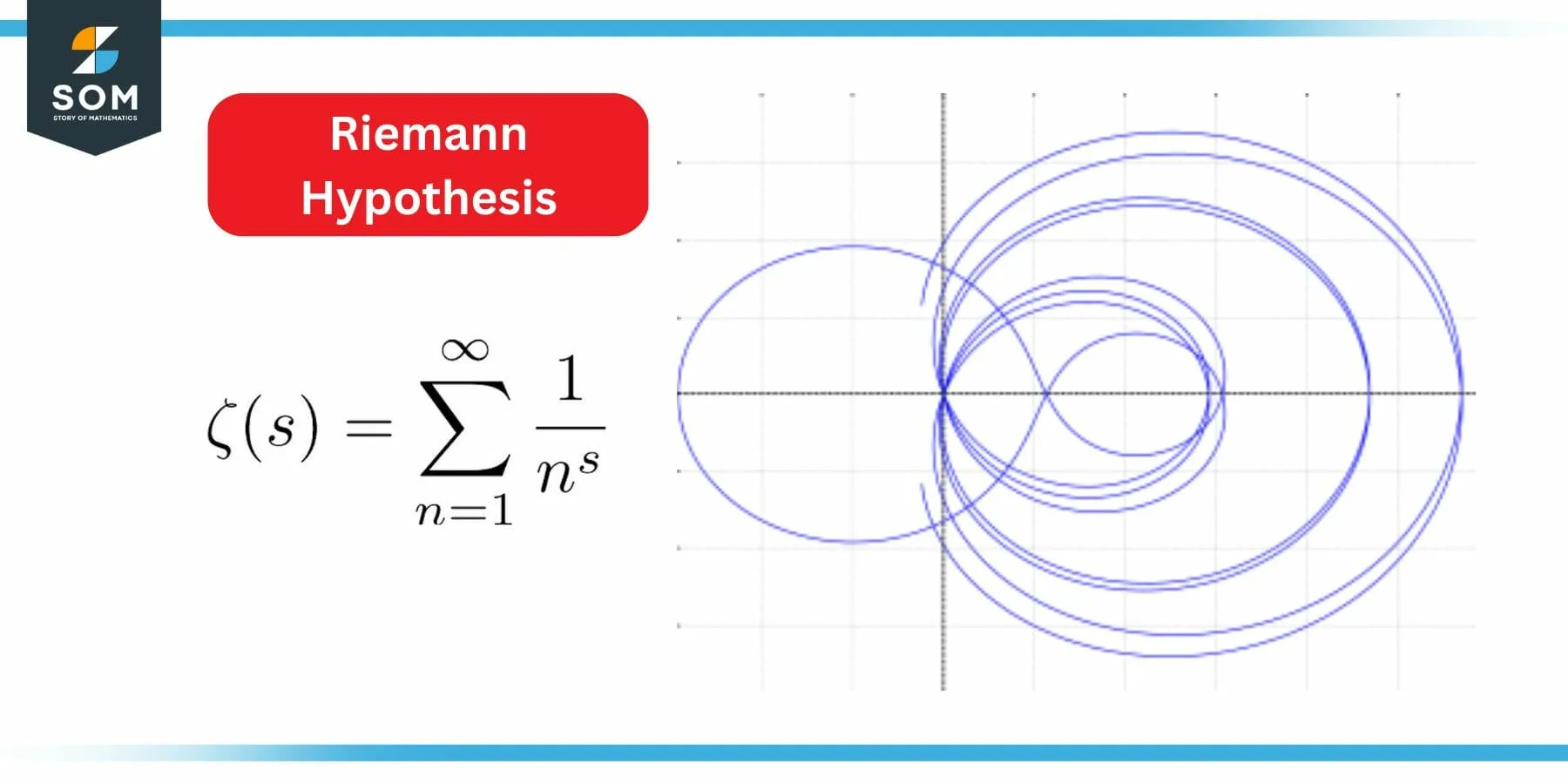

According to the Riemann hypothesis, only negative even integers and complex numbers with real part 1/2 have zeros in the Riemann zeta function . It is regarded by many as the most significant open issue in pure mathematics.

Figure 4: Riemann Hypothesis

The Riemann hypothesis is the most well-known mathematical conjecture, and it has been the subject of innumerable proof efforts.

Numerical Examples

Identify the conclusions and hypothesis in the following given statements. Also state if the conclusion supports the hypothesis or not.

Part (a): If 30x = 30, then x = 1

Part (b): if 10x + 2 = 50, then x = 24

Hypothesis: 30x = 30

Conclusion: x = 10

Supports Hypothesis: Yes

Hypothesis: 10x + 2 = 50

Conclusion: x = 24

All images/mathematical drawings were created with GeoGebra.

Hour Hand Definition < Glossary Index > Identity Definition

Forgot password? New user? Sign up

Existing user? Log in

Hypothesis Testing

Already have an account? Log in here.

A hypothesis test is a statistical inference method used to test the significance of a proposed (hypothesized) relation between population statistics (parameters) and their corresponding sample estimators . In other words, hypothesis tests are used to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample to prove a hypothesis true for the entire population.

The test considers two hypotheses: the null hypothesis , which is a statement meant to be tested, usually something like "there is no effect" with the intention of proving this false, and the alternate hypothesis , which is the statement meant to stand after the test is performed. The two hypotheses must be mutually exclusive ; moreover, in most applications, the two are complementary (one being the negation of the other). The test works by comparing the \(p\)-value to the level of significance (a chosen target). If the \(p\)-value is less than or equal to the level of significance, then the null hypothesis is rejected.

When analyzing data, only samples of a certain size might be manageable as efficient computations. In some situations the error terms follow a continuous or infinite distribution, hence the use of samples to suggest accuracy of the chosen test statistics. The method of hypothesis testing gives an advantage over guessing what distribution or which parameters the data follows.

Definitions and Methodology

Hypothesis test and confidence intervals.

In statistical inference, properties (parameters) of a population are analyzed by sampling data sets. Given assumptions on the distribution, i.e. a statistical model of the data, certain hypotheses can be deduced from the known behavior of the model. These hypotheses must be tested against sampled data from the population.

The null hypothesis \((\)denoted \(H_0)\) is a statement that is assumed to be true. If the null hypothesis is rejected, then there is enough evidence (statistical significance) to accept the alternate hypothesis \((\)denoted \(H_1).\) Before doing any test for significance, both hypotheses must be clearly stated and non-conflictive, i.e. mutually exclusive, statements. Rejecting the null hypothesis, given that it is true, is called a type I error and it is denoted \(\alpha\), which is also its probability of occurrence. Failing to reject the null hypothesis, given that it is false, is called a type II error and it is denoted \(\beta\), which is also its probability of occurrence. Also, \(\alpha\) is known as the significance level , and \(1-\beta\) is known as the power of the test. \(H_0\) \(\textbf{is true}\)\(\hspace{15mm}\) \(H_0\) \(\textbf{is false}\) \(\textbf{Reject}\) \(H_0\)\(\hspace{10mm}\) Type I error Correct Decision \(\textbf{Reject}\) \(H_1\) Correct Decision Type II error The test statistic is the standardized value following the sampled data under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true, and a chosen particular test. These tests depend on the statistic to be studied and the assumed distribution it follows, e.g. the population mean following a normal distribution. The \(p\)-value is the probability of observing an extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternate hypothesis, given that the null hypothesis is true. The critical value is the value of the assumed distribution of the test statistic such that the probability of making a type I error is small.

Methodologies: Given an estimator \(\hat \theta\) of a population statistic \(\theta\), following a probability distribution \(P(T)\), computed from a sample \(\mathcal{S},\) and given a significance level \(\alpha\) and test statistic \(t^*,\) define \(H_0\) and \(H_1;\) compute the test statistic \(t^*.\) \(p\)-value Approach (most prevalent): Find the \(p\)-value using \(t^*\) (right-tailed). If the \(p\)-value is at most \(\alpha,\) reject \(H_0\). Otherwise, reject \(H_1\). Critical Value Approach: Find the critical value solving the equation \(P(T\geq t_\alpha)=\alpha\) (right-tailed). If \(t^*>t_\alpha\), reject \(H_0\). Otherwise, reject \(H_1\). Note: Failing to reject \(H_0\) only means inability to accept \(H_1\), and it does not mean to accept \(H_0\).

Assume a normally distributed population has recorded cholesterol levels with various statistics computed. From a sample of 100 subjects in the population, the sample mean was 214.12 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter), with a sample standard deviation of 45.71 mg/dL. Perform a hypothesis test, with significance level 0.05, to test if there is enough evidence to conclude that the population mean is larger than 200 mg/dL. Hypothesis Test We will perform a hypothesis test using the \(p\)-value approach with significance level \(\alpha=0.05:\) Define \(H_0\): \(\mu=200\). Define \(H_1\): \(\mu>200\). Since our values are normally distributed, the test statistic is \(z^*=\frac{\bar X - \mu_0}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}=\frac{214.12 - 200}{\frac{45.71}{\sqrt{100}}}\approx 3.09\). Using a standard normal distribution, we find that our \(p\)-value is approximately \(0.001\). Since the \(p\)-value is at most \(\alpha=0.05,\) we reject \(H_0\). Therefore, we can conclude that the test shows sufficient evidence to support the claim that \(\mu\) is larger than \(200\) mg/dL.

If the sample size was smaller, the normal and \(t\)-distributions behave differently. Also, the question itself must be managed by a double-tail test instead.

Assume a population's cholesterol levels are recorded and various statistics are computed. From a sample of 25 subjects, the sample mean was 214.12 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter), with a sample standard deviation of 45.71 mg/dL. Perform a hypothesis test, with significance level 0.05, to test if there is enough evidence to conclude that the population mean is not equal to 200 mg/dL. Hypothesis Test We will perform a hypothesis test using the \(p\)-value approach with significance level \(\alpha=0.05\) and the \(t\)-distribution with 24 degrees of freedom: Define \(H_0\): \(\mu=200\). Define \(H_1\): \(\mu\neq 200\). Using the \(t\)-distribution, the test statistic is \(t^*=\frac{\bar X - \mu_0}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}=\frac{214.12 - 200}{\frac{45.71}{\sqrt{25}}}\approx 1.54\). Using a \(t\)-distribution with 24 degrees of freedom, we find that our \(p\)-value is approximately \(2(0.068)=0.136\). We have multiplied by two since this is a two-tailed argument, i.e. the mean can be smaller than or larger than. Since the \(p\)-value is larger than \(\alpha=0.05,\) we fail to reject \(H_0\). Therefore, the test does not show sufficient evidence to support the claim that \(\mu\) is not equal to \(200\) mg/dL.

The complement of the rejection on a two-tailed hypothesis test (with significance level \(\alpha\)) for a population parameter \(\theta\) is equivalent to finding a confidence interval \((\)with confidence level \(1-\alpha)\) for the population parameter \(\theta\). If the assumption on the parameter \(\theta\) falls inside the confidence interval, then the test has failed to reject the null hypothesis \((\)with \(p\)-value greater than \(\alpha).\) Otherwise, if \(\theta\) does not fall in the confidence interval, then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternate \((\)with \(p\)-value at most \(\alpha).\)

- Statistics (Estimation)

- Normal Distribution

- Correlation

- Confidence Intervals

Problem Loading...

Note Loading...

Set Loading...

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Hypothesis. A statement that could be true, which might then be tested. Example: Sam has a hypothesis that "large dogs are better at catching tennis balls than small dogs". We can test that hypothesis by having hundreds of different sized dogs try to catch tennis balls. Sometimes the hypothesis won't be tested, it is simply a good explanation ...

A hypothesis is a proposition that is consistent with known data, but has been neither verified nor shown to be false. In statistics, a hypothesis (sometimes called a statistical hypothesis) refers to a statement on which hypothesis testing will be based. Particularly important statistical hypotheses include the null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis. In symbolic logic, a hypothesis is the ...

Definition: statistical procedure. Hypothesis testing is a statistical procedure in which a choice is made between a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis based on information in a sample. The end result of a hypotheses testing procedure is a choice of one of the following two possible conclusions: Reject H0.

Types of Hypothesis. The hypothesis can be broadly classified into different types. They are: Simple Hypothesis. A simple hypothesis is a hypothesis that there exists a relationship between two variables. One is called a dependent variable, and the other is called an independent variable. Complex Hypothesis.

In hypothesis testing, the goal is to see if there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject a presumed null hypothesis in favor of a conjectured alternative hypothesis. The null hypothesis is usually denoted H0 while the alternative hypothesis is usually denoted H1. An hypothesis test is a statistical decision; the conclusion will either be ...

Thus the hypothesis is what we must assume in order to be positive that the conclusion will hold. Whenever you are asked to state a theorem, be sure to include the hypothesis. In order to know when you may apply the theorem, you need to know what constraints you have. So in the example above, if we know that a function is differentiable, we may ...

A hypothesis is a statement or idea which gives an explanation to a series of observations. Sometimes, following observation, a hypothesis will clearly need to be refined or rejected. This happens if a single contradictory observation occurs. For example, suppose that a child is trying to understand the concept of a dog.

The null hypothesis ( H0. H 0. ) is a statement about the population that either is believed to be true or is used to put forth an argument unless it can be shown to be incorrect beyond a reasonable doubt. The alternative hypothesis ( Ha. H a. ) is a claim about the population that is contradictory to H0.

Definition. A hypothesis is a claim or statement that makes sense in the context of some information or data at hand but hasn’t been established as true or false through experimentation or proof. In mathematics, any statement or equation that describes some relationship between certain variables can be termed as hypothesis if it is consistent ...

A hypothesis test is a statistical inference method used to test the significance of a proposed (hypothesized) relation between population statistics (parameters) and their corresponding sample estimators. In other words, hypothesis tests are used to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample to prove a hypothesis true for the entire population. The test considers two hypotheses: the ...