- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Adaptation

Introduction.

- Filmographies

- Bibliographies

- Literature versus Cinema

- Interart Analogies

- Medium-Specific Studies

- Case Studies of Classic Fiction

- Case Studies of Modern Fiction

- Theoretically Oriented Collections

- Thematically Oriented Collections

- Cultural Studies

- Around the World

- Painting, Performance, Television

- Convergence Culture

- Adaptation, Remediation, and Intermediality

- Translation

- Textual and Biological Adaptation

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- André Bazin

- Australian Cinema

- Dashiell Hammett

- David Cronenberg

- Documentary Film

- Douglas Sirk

- Erich Von Stroheim

- Film and Literature

- Francis Ford Coppola

- Game of Thrones

- Hou Hsiao-Hsien

- Icelandic Cinema

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- It Happened One Night

- Jean Renoir

- Lee Chang-dong

- Luchino Visconti

- Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Ridley Scott

- Robert Altman

- Robert Bresson

- Roger Corman

- Russian Cinema

- Sally Potter

- Shakespeare on Film

- Sidney Lumet

- Terry Gilliam

- The Coen Brothers

- The Godfather Trilogy

- The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

- The Wizard of Oz

- Wong Kar-wai

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Jacques Tati

- Media Materiality

- The Golden Girls

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Adaptation by Thomas Leitch , Kyle Meikle LAST REVIEWED: 29 September 2014 LAST MODIFIED: 29 September 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0116

Studies of cinematic adaptations—films based, as the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences puts it, on material originally presented in another medium—are scarcely a century old. Even so, particular studies of adaptation, the process by which texts in a wide range of media are transformed into films (and more recently into other texts that are not necessarily films), cannot be properly understood without reference to the specific period they were produced in. Each generation of adaptation studies has produced its own principles and orthodoxies, typically by attacking the orthodoxies and principles of the preceding generation. Adaptation studies have regularly alternated between polemics that attacked earlier assumptions in the field and readings of individual adaptations that have explored the implications of these attacks and so implicitly established new orthodoxies. The earliest work on adaptation, from Vachel Lindsay’s The Art of the Moving Picture , first published in 1915, to André Bazin’s “Adaptation, or the Cinema as Digest,” first published in 1948, grapples with the general relationship between literature and cinema as presentational modes. The second phase, focusing mostly on adaptations of individual novels to films, follows George Bluestone’s highly influential 2003 study Novels into Film , originally published in 1957, in assuming a series of categorical distinctions between verbal and visual representational modes. Most studies of individual adaptations and their sources, and most textbooks on adaptation, have been produced under the influence of these assumptions. In this third phase, Robert Stam’s 2000 article “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation” rejects the binary distinctions between source texts and adaptations; Kamilla Elliott’s 2003 book Rethinking the Novel/Film Debate deconstructs the binary distinctions between verbal and visual texts; and Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn’s 2012 book A Theory of Adaptation emphasizes the continuities between texts that have been explicitly identified as adaptations and all other texts as intertextual palimpsests marked by traces of innumerable earlier texts. This third phase has generated most of the leading work on adaptation theory. An emerging fourth phase is heralded by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s 1999 study Remediation: Understanding New Media and Lev Manovich’s 2001 book The Language of New Media . Both are inspired by the rise of the digital media that establishes every reader as a potential writer. These analysts use a Wiki-based model of writing as community participation rather than individual creation to break down the distinction between reading and writing and recast adaptation as a quintessential instance of the incessant process of textual production. A leading tendency of this fourth phase has been to use methodologies developed for literature-to-film adaptation to analyze adaptations that range far outside literature and cinema.

General Resources

Earlier than any other area of cinema studies, adaptation began to generate a substantial body of resources specifically designed for teachers, students, and academic researchers. The dominance of the case study in the second phase of adaptation studies produced an especially comprehensive and wide-ranging series of literature-to-cinema filmographies, some aiming for exhaustiveness, others for greater selectivity and more extended analysis of particular novel-to-film or theater-to-film pairs. The prominence of college courses in film adaptation generated a number of textbooks focusing on cinematic adaptation, and later a series of essays considering the larger theoretical and pedagogical issues that were raised, or that could be raised, by focusing on adaptations.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latin American Cinema

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Film

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

Adaptation Before Cinema pp 1–17 Cite as

Introduction: Adaptation’s Past, Adaptation’s Future

- Glenn Jellenik 5 &

- Lissette Lopez Szwydky 6

- First Online: 20 January 2023

239 Accesses

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture ((PSADVC))

This chapter situates Adaptation Before Cinema as a historical intervention into adaptation studies, making the case that an over-reliance on film adaptation has left the field historically myopic. Decentering film opens multiple directions for adaptation studies past, present, and future and brings new voices and approaches into the critical conversation. The editors of the collection trace the ways in which adaptation studies can be enriched by rethinking the function of adaptation, by not only acknowledging but also exploring adaptation as a transhistorical, global phenomenon that also crosses forms, media, and genres. Jellenik and Szwydky argue that scholars of literature and culture working in historical fields that predate the twentieth century are uniquely positioned to identify common points of interest with adaptation studies and its standard theoretical and critical approaches, demonstrating to contemporary media theorists how much twentieth- and twenty-first-century media forms and industry practices continue to be influenced not only by historical literary sources but also by early adaptation practices that predate film and other contemporary media. Attention to those older adaptations and adaptation practices can yield creative and productive critical approaches that can be applied across contemporary media adaptation studies. As Jellenik and Szwydky argue, adaptations and other forms of extension and transmediation have always driven literature, theater, art, and popular culture, as well as shaped the construction and reception histories of specific texts. These connections and broader stakes for the study of literature and culture crystallize when we excavate and analyze forms of adaptation and transmedia that drove storytelling before the twentieth century.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Works Cited

Andrew, Dudley. “Adaptation,” in Concepts in Film Theory . New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. 96–106.

Google Scholar

Bortolotti, Gary, and Linda Hutcheon, “On the Origins of Adaptation: Rethinking ‘Success’—Biologically.” New Literary History (2007): 443–58.

Elliott, Kamilla. Theorizing Adaptation . Oxford University Press, 2020.

— Portraiture and British Gothic Fiction: The Rise of Picture Identification, 1764–1835 .

— Rethinking the Film/Novel Debate

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree . Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. Originally published in French by Editions du Seuil, 1982.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation . Routledge: New York, 2006.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide . New York University Press, 2006.

Laird, Karen E. The Art of Adapting Victorian Literature, 1848–1920: Jane Eyre , David Copperfield , and The Woman in White. Ashgate, 2015.

Lanier, Douglas M. “Shakespearean Rhizomatics: Adaptation, Ethics, Value.” Shakespeare and the Ethics of Appropriation , edited by Alexa Huang and Elizabeth Rivlin, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 21–40.

Lev, Peter, “How to Write Adaptation History,” book chapter in The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies , ed. Leitch, Oxford University Press, 2017: (661–678).

MacCabe, Colin, “Bazinian Adaptation: The Butcher Boy as Example,” Introduction to True to the Spirit, Oxford University Press, 2011: (3–25).

Meikle, Kyle. Adaptations in the Franchise Era, 2001–2016 . Bloomsbury, 2019.

Semenza, Gregory. “Towards a Historical Turn? Adaptation Studies and the Challenges of History.” The Routledge Companion to Adaptation , edited by Dennis Cutchins, Katja Krebs, and Eckart Voigts, Routledge, 2018, 58–66.

Semenza, Gregory, and Bob Hasenfratz. The History of British Literature on Film: 1895–2015. Co-authored with New York and London: Bloomsbury Press, 2015.

Szwydky, Lissette Lopez. Transmedia Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century , Ohio State University Press, 2020.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, University of Central Arkansas, Conway, AR, USA

Glenn Jellenik

Department of English, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA

Lissette Lopez Szwydky

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Glenn Jellenik or Lissette Lopez Szwydky .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Jellenik, G., Szwydky, L.L. (2023). Introduction: Adaptation’s Past, Adaptation’s Future. In: Szwydky, L.L., Jellenik, G. (eds) Adaptation Before Cinema. Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09596-2_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09596-2_1

Published : 20 January 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-09595-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-09596-2

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

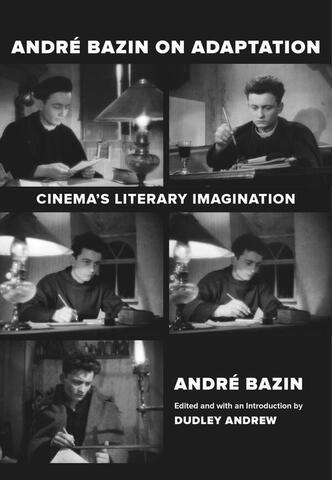

From Celebrated Film Scholar Dudley Andrew: Andre Bazin on Adaptation

Available for the first time in English, these previously unavailable essays introduce readers to the foundational concepts of the relationship between film and literary adaptation as put forth by one of the greatest film and cultural critics of the 20th century.

Adaptation was central to André Bazin’s lifelong query: What is cinema? Placing films alongside literature allowed him to identify the aesthetic and sociological distinctiveness of each medium. More importantly, it helped him wage his campaign for a modern conception of cinema, one that owed a great deal to developments in the novel. The critical genius of one of the greatest film and cultural critics of the twentieth century is on full display in this collection, in which readers are introduced to Bazin’s foundational concepts of the relationship between film and literary adaptation.

Expertly curated and with an introduction by celebrated film scholar Dudley Andrew, the book begins with a selection of essays that show Bazin’s film theory in action, followed by reviews of films adapted from renowned novels of the day (Conrad, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Colette, Sagan, Duras, and others) as well as classic novels of the nineteenth century (Bronte, Melville, Tolstoy, Balzac, Hugo, Zola, Stendhal, and more). As a bonus, two hundred and fifty years of French fiction are put into play as Bazin assesses adaptation after adaptation to determine what is at stake for culture, for literature, and especially for cinema. This volume will be an indispensable resource for anyone interested in literary adaptation, authorship, classical film theory, French film history, and André Bazin’s criticism.

Dudley Andrew , Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature and of Film Studies at Yale University, is biographer of André Bazin, whose ideas he extends in What Cinema Is! and Opening Bazin . With two books on 1930s French Cinema, Andrew was named Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The following passage is excerpted from the book’s Introduction, written by translator Dudley Andrew, and titled: André Bazin’s Position in Cinema’s Literary Imagination

More than forty years ago, I inadvertently put my foot into what Mary Ann Doane, soon to be a distinguished film scholar, warned me was the swamp of adaptation, when I composed an under-researched article that has kept me trudging intermittently onward ever since.1 That article has many problems, but it did properly stake out the two principal directions one could take in this unmapped zone: semiotics and sociology. The former avoids history and encompasses media specificity (including media overlap), narratology, comparative stylistics, registers of equivalence, and degrees of fidelity. The latter deals with periods and movements in multiple arts; the varied incarnations and remediations of overriding themes, situations, and characters; the national promotion or censorship of topics; comparative reception and the fluctuating force of fandom, etc. Both directions demand general reflection and specific case studies. In 1980, emerging from a decade of semiotics and narratology, I held the banner of the sociological alternative high so it could at least be recognized. Actually I was unknowingly contributing to a wave that turned the leading edge of adaptation studies away from analyzing pairs of texts (novels into films) and toward cultural studies. I urged broad but controlled research into how literary texts and movements have been appropriated and exploited by producers and consumers in various times and places, and how, sometimes, there has been a reverse flow from film back to literature. The impact of the text, not its inviolability, counts for social history. Then cultural studies came to completely dominate the humanities, and I flinched to see original works of literature left unprotected from roving bands of critics who applauded while books and plays I considered masterworks were manhandled in ways alleged to be relevant, challenging, or simply postmodern. Eventually I published an about-face called “The Economies of Fidelity” in a collection neatly titled True to the Spirit . Fidelity, I argued, cannot be pushed brusquely aside. It may be overvalued, but it remains a value for all that, and one not to be dismissed even in cases when it is flagrantly traduced.

Evidently, I don’t know where I stand, apparently trudging in both directions. But I take heart, since André Bazin had done the same, though in his case with a plan and in full awareness. He knew that a social history of the arts alongside technological and stylistic knowledge of both literature and cinema must accompany, perhaps tacitly, any worthwhile examination and assessment of those many moments when these media collide in adaptation. Adaptations are not curiosities, constituting a niche genre. They are crucial for the health and growth of both fiction and film. They also open up for the critic and the public a glimpse into the (semiotic) workings of both forms and into the sociology of cultural production.

Bazin treated cinema’s rapport with literature, what I call its “literary imagination,” as the necessary complement to its rapport with reality. His most famous essay, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” anchoring his realism, appeared in print in 1945, a few months before his equally intricate piece on André Malraux’s Espoir came out in Poésie . There Bazin dared to suggest that Malraux’s film could be taken on a par with his novel, because, as he would state three years later in “Cinema as Digest,” it is effectively its twin and it doesn’t matter which was the first to come out of Malraux’s head. Even if they drift down different streams of cultural history—one literary, the other cinematic—they share the DNA of this auteur’s style. “Cinema as Digest” put the new medium in its place, that is, situated it among the arts as these have evolved in Western culture since the Middle Ages. This kind of historical-cultural investigation was essential to Bazin’s quest to discover “What is Cinema?,” just as were his ideas about the medium’s specificity in the essay on photography’s ontology. Certain that, pace Jean-Paul Sartre, “Cinema’s existence precedes its essence,” Bazin recognized the need for an ontogeny of the medium that would complement its ontology. Both types of investigation demand a scrutiny of cinema’s stylistic resources, such as he provided in the Malraux example and many of his film reviews. As those reviews intermittently demonstrate, cinema’s ontogeny involves an evolution in which it grew out of, and in symbiosis with, literature.

This post is part of our #SCMS22 series. Conference attendees can get 40% off the book with code 21E5879.

TAGS: #SCMS22 , 9780520375819 , André Bazin , Cinema , Dudley Andrew , Film Studies , literary adaptation

CATEGORIES: Film & Media Studies , Literary Studies & Poetry

Film and Media Studies Program

André bazin on adaptation: cinema’s literary imagination.

By Andre Bazin , Dudley Andrew (Editor) , Deborah Glassman (Translator) , Natasa Durovicova (Translator)

Adaptation was central to André Bazin’s lifelong query: What is cinema? Placing films alongside literature allowed him to identify the aesthetic and sociological distinctiveness of each medium. More importantly, it helped him wage his campaign for a modern conception of cinema, one that owed a great deal to developments in the novel. The critical genius of one of the greatest film and cultural critics of the twentieth century is on full display in this collection, in which readers are introduced to Bazin’s foundational concepts of the relationship between film and literary adaptation. Expertly curated and with an introduction by celebrated film scholar Dudley Andrew, the book begins with a selection of essays that show Bazin’s film theory in action, followed by reviews of films adapted from renowned novels of the day (Conrad, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Colette, Sagan, Duras, and others) as well as classic novels of the nineteenth century (Bronte, Melville, Tolstoy, Balzac, Hugo, Zola, Stendhal, and more). As a bonus, two hundred and fifty years of French fiction are put into play as Bazin assesses adaptation after adaptation to determine what is at stake for culture, for literature, and especially for cinema. This volume will be an indispensable resource for anyone interested in literary adaptation, authorship, classical film theory, French film history, and André Bazin’s criticism.

The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies

Thomas Leitch is Professor of English at the University of Delaware. His most recent books are A Companion to Alfred Hitchcock, co-edited with Leland Poague (2011), and Wikipedia U: Knowledge, Authority, and Liberal Education in the Digital Age (2014). He is currently working on The History of American Literature on Film.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This collection of forty original essays reflects on the history of adaptation studies, surveys the current state of the field, and maps out possible futures that mobilize its unparalleled ability to bring together theorists and practitioners in different modes of discourse. Grounding contemporary adaptation studies in a series of formative debates about what adaptation is, whether its orientation should be scientific or aesthetic, and whether it is most usefully approached inductively, through close analyses of specific adaptations, or deductively, through general theories of adaptation, the volume, not so much a museum as a laboratory or a provocation, aims to foster, rather than resolve, these debates. Its seven parts focus on the historical and theoretical foundations of adaptation study, the problems raised by adapting canonical classics and the aesthetic commons, the ways different genres and presentational modes illuminate and transform the nature of adaptation, the relations between adaptation and intertextuality, the interdisciplinary status of adaptation, and the issues involved in professing adaptation, now and in the future. Embracing an expansive view of adaptation and adaptation studies, it emphasizes the area’s status as a crossroads or network that fosters interactive exchange across many disciplines and advocates continued debate on its leading questions as the best defense against the possibilities of dilution, miscommunication, and chaos that this expansive view threatens to introduce to a burgeoning field uniquely responsive to the contemporary textual landscape.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

THEORIES OF ADAPTATION: NOVEL TO FILM

Related Papers

International Journal of Innovative Knowledge Concepts- ISSN 2454-2415- Vol 1- 2017

Many film critics like have provided a base for the nature and method of the adaptation as an inter-relative idea between literature and film. The film script is not always an entirely new literary form. It simply translates. According to Balazs, the novel or drama should be regarded, as a potential raw material to be transformed at will by the writer of the screenplay. After that, the screenplay has an ability to approach reality, to approach the thematic and the formal design of the literary model and represent it with various viewpoints. The adaptation is also considered as an entirely new entity which provides several variations also. This paper attempts to explore the visual medium translation of the printed words by analyzing Shakespeare"s Macbeth in its various cinematic interpretations. Macbeth was adopted by many filmmakers across the world and this paper deliberates on three major adaptations: Indian version of Macbeth by Vishal Bhardwaj called Maqbool, Orson Welles"s version of Macbeth (1948) and Akira Kurosawa"s Japanese version of Macbeth called The Throne of Blood Introduction:

Azeez Jasim

To what extent our innermost feelings can be revealed through our works? The unbearable face of human being cannot be hidden and what a director shot in a film may reveal the real sense of what is hidden from our eyes. Thus directors sometimes try to hide their dark side behind such interesting movies after having modified the events of the original text to achieve their end. This paper, however, is an overview about the technique of adaptation which varies from one adaptationist to another depending on the historical background of the screenplay writer. Although the director succeeds to project what is on one side of his curtain, he fails to hide what is on the other side that discloses his innermost feelings.

Journal of Screenwriting

Shannon Wells-Lassagne

shyamali banerjee

John Mitras

The purpose of this paper is to show how recent research on the nature of dramatic language can further our understanding of the problematic nature of exporting Shakespearean texts on to the medium of film. This paper is written in three parts. The first part discusses the performance-orientation of dramatic language; the second part considers the possible choreography for spatial organization and kinesics suggested by dramatic language; the third part looks at some of the ways cinema neutralizes the performative potential of dramatic language. The central argument is that a successful modern-day adaptation of Shakespeare's plays will in some ways be hindered by the retention of the original script.

Studies in Literature and Language

aiman al-garrallah

Cătălin Constantinescu

This research is based on my multiple readings and re-readings of the novels of George Orwell for almost two decades. Orwell’s 1984, at least, is not just a very influent writing on our perceptions regarding surveillance: “Big Brother” is everywhere as discursive instance in our days; this may be a political and sociological starting point of discussion. Besides, it is a good example for discussing various aspects of how literature is used by readers – implying a whole debate upon the functions of literature. My reading of the filmic rewriting of Orwell’s 1984 (discussed in another study) revealed profound mutations in analysing the film as medium. It provided grounds for comparison, but not just for the sake of comparison (“comparaison n’est pas raison”, as Rene Etiemble emphasized in ‘60s). It is a fruitful starting point, as I try to focus on the relationships not only between film and literature, but also on dialectics of various approaches on the relationship between these media. The main goals are to observe and to evaluate what “degree of theoreticity” is admitted in our critical reading of adaptation. Comparatists should also investigate – as Claudio Guillén stated in Entre lo uno y lo diverso: introducción a la literatura comparada (1985) – how far can we go with categories or classes when they are subject of a comparative reading. In analysing the relationships between film and literature, one must not forget Susan Sontag’s claim in affirming that film, the narrative film namely (use of plot, characters, setting, dialogue, imagery, manipulating time and space) shares with literature the most.

Siddhant Kalra

As old as the machinery of film itself, literary texts have continually informed cinematic adaptations. The interaction of two discrete media evokes questions pertaining to the nature of adaptations. Are they a new text or is a text purely 'textual'? In light of adaptation theory and the history of cinema, this paper offers a brief assessment of this phenomenological inquiry. 'Fidelity' to the source literary text has conventionally been the primary criterion for assessing a film adaptation. This paper also explores this assumption and its transformation in the postmodern world.

Literature Film Quarterly

greg semenza

Johannes von Moltke

RELATED PAPERS

Iconos Revista De Ciencias Sociales

Gustavo Abad

Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy

Marcela Henao Tamayo

Interdental Jurnal Kedokteran Gigi (IJKG)

yudha rahina

Gustavo André Borges

Pusat Grosir Legging Panjang

Bruno Valle

Anne-marie Caminade

Quaderni d'italianistica

Dino Cervigni

Laura Marcela Becerra Muñoz

Volker Roth

Journal of Armed Forces Medical College, Bangladesh

Susane Giti

Organic Reactions

Rebecca DeVasher

Journal of Tropical Pediatrics

Sukran Darcan

Surface and Coatings Technology

KEVIN ALEXANDER ZELIDÓN RIVERA

Journal of the Neurological Sciences

Peter Dowling

2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)

Injury Prevention

Dale Hanson

American Journal of Analytical Chemistry

Yadollah Yamini

SN applied sciences

mujahid khan

Menachem Hanani

Applied optics

Bruno Marangoni

Informe Gepec

Gilnei Saurin

hyutrTT hytutr

The Lancet Neurology

SANDRA ROSSI

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Film Writing: Sample Analysis

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Introductory Note

The analysis below discusses the opening moments of the science fiction movie Ex Machina in order to make an argument about the film's underlying purpose. The text of the analysis is formatted normally. Editor's commentary, which will occasionally interrupt the piece to discuss the author's rhetorical strategies, is written in brackets in an italic font with a bold "Ed.:" identifier. See the examples below:

The text of the analysis looks like this.

[ Ed.: The editor's commentary looks like this. ]

Frustrated Communication in Ex Machina ’s Opening Sequence

Alex Garland’s 2015 science fiction film Ex Machina follows a young programmer’s attempts to determine whether or not an android possesses a consciousness complicated enough to pass as human. The film is celebrated for its thought-provoking depiction of the anxiety over whether a nonhuman entity could mimic or exceed human abilities, but analyzing the early sections of the film, before artificial intelligence is even introduced, reveals a compelling examination of humans’ inability to articulate their thoughts and feelings. In its opening sequence, Ex Machina establishes that it’s not only about the difficulty of creating a machine that can effectively talk to humans, but about human beings who struggle to find ways to communicate with each other in an increasingly digital world.

[ Ed.: The piece's opening introduces the film with a plot summary that doesn't give away too much and a brief summary of the critical conversation that has centered around the film. Then, however, it deviates from this conversation by suggesting that Ex Machina has things to say about humanity before non-human characters even appear. Off to a great start. ]

The film’s first establishing shots set the action in a busy modern office. A woman sits at a computer, absorbed in her screen. The camera looks at her through a glass wall, one of many in the shot. The reflections of passersby reflected in the glass and the workspace’s dim blue light make it difficult to determine how many rooms are depicted. The camera cuts to a few different young men typing on their phones, their bodies partially concealed both by people walking between them and the camera and by the stylized modern furniture that surrounds them. The fourth shot peeks over a computer monitor at a blonde man working with headphones in. A slight zoom toward his face suggests that this is an important character, and the cut to a point-of-view shot looking at his computer screen confirms this. We later learn that this is Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson), a young programmer whose perspective the film follows.

The rest of the sequence cuts between shots from Caleb’s P.O.V. and reaction shots of his face, as he receives and processes the news that he has won first prize in a staff competition. Shocked, Caleb dives for his cellphone and texts several people the news. Several people immediately respond with congratulatory messages, and after a moment the woman from the opening shot runs in to give him a hug. At this point, the other people in the room look up, smile, and start clapping, while Caleb smiles disbelievingly—perhaps even anxiously—and the camera subtly zooms in a bit closer. Throughout the entire sequence, there is no sound other than ambient electronic music that gets slightly louder and more textured as the sequence progresses. A jump cut to an aerial view of a glacial landscape ends the sequence and indicates that Caleb is very quickly transported into a very unfamiliar setting, implying that he will have difficulty adjusting to this sudden change in circumstances.

[ Ed.: These paragraphs are mostly descriptive. They give readers the information they will need to understand the argument the piece is about to offer. While passages like this can risk becoming boring if they dwell on unimportant details, the author wisely limits herself to two paragraphs and maintains a driving pace through her prose style choices (like an almost exclusive reliance on active verbs). ]

Without any audible dialogue or traditional expository setup of the main characters, this opening sequence sets viewers up to make sense of Ex Machina ’s visual style and its exploration of the ways that technology can both enhance and limit human communication. The choice to make the dialogue inaudible suggests that in-person conversations have no significance. Human-to-human conversations are most productive in this sequence when they are mediated by technology. Caleb’s first response when he hears his good news is to text his friends rather than tell the people sitting around him, and he makes no move to take his headphones out when the in-person celebration finally breaks out. Everyone in the building is on their phones, looking at screens, or has headphones in, and the camera is looking at screens through Caleb’s viewpoint for at least half of the sequence.

Rather than simply muting the specific conversations that Caleb has with his coworkers, the ambient soundtrack replaces all the noise that a crowded building in the middle of a workday would ordinarily have. This silence sets the uneasy tone that characterizes the rest of the film, which is as much a horror-thriller as a piece of science fiction. Viewers get the sense that all the sounds that humans make as they walk around and talk to each other are being intentionally filtered out by some presence, replaced with a quiet electronic beat that marks the pacing of the sequence, slowly building to a faster tempo. Perhaps the sound of people is irrelevant: only the visual data matters here. Silence is frequently used in the rest of the film as a source of tension, with viewers acutely aware that it could be broken at any moment. Part of the horror of the research bunker, which will soon become the film’s primary setting, is its silence, particularly during sequences of Caleb sneaking into restricted areas and being startled by a sudden noise.

The visual style of this opening sequence reinforces the eeriness of the muted humans and electronic soundtrack. Prominent use of shallow focus to depict a workspace that is constructed out of glass doors and walls makes it difficult to discern how large the space really is. The viewer is thus spatially disoriented in each new setting. This layering of glass and mirrors, doubling some images and obscuring others, is used later in the film when Caleb meets the artificial being Ava (Alicia Vikander), who is not allowed to leave her glass-walled living quarters in the research bunker. The similarity of these spaces visually reinforces the film’s late revelation that Caleb has been manipulated by Nathan Bates (Oscar Isaac), the troubled genius who creates Ava.

[ Ed.: In these paragraphs, the author cites the information about the scene she's provided to make her argument. Because she's already teased the argument in the introduction and provided an account of her evidence, it doesn't strike us as unreasonable or far-fetched here. Instead, it appears that we've naturally arrived at the same incisive, fascinating points that she has. ]

A few other shots in the opening sequence more explicitly hint that Caleb is already under Nathan’s control before he ever arrives at the bunker. Shortly after the P.O.V shot of Caleb reading the email notification that he won the prize, we cut to a few other P.O.V. shots, this time from the perspective of cameras in Caleb’s phone and desktop computer. These cameras are not just looking at Caleb, but appear to be scanning him, as the screen flashes in different color lenses and small points appear around Caleb’s mouth, eyes, and nostrils, tracking the smallest expressions that cross his face. These small details indicate that Caleb is more a part of this digital space than he realizes, and also foreshadow the later revelation that Nathan is actively using data collected by computers and webcams to manipulate Caleb and others. The shots from the cameras’ perspectives also make use of a subtle fisheye lens, suggesting both the wide scope of Nathan’s surveillance capacities and the slightly distorted worldview that motivates this unethical activity.

[ Ed.: This paragraph uses additional details to reinforce the piece's main argument. While this move may not be as essential as the one in the preceding paragraphs, it does help create the impression that the author is noticing deliberate patterns in the film's cinematography, rather than picking out isolated coincidences to make her points. ]

Taken together, the details of Ex Machina ’s stylized opening sequence lay the groundwork for the film’s long exploration of the relationship between human communication and technology. The sequence, and the film, ultimately suggests that we need to develop and use new technologies thoughtfully, or else the thing that makes us most human—our ability to connect through language—might be destroyed by our innovations. All of the aural and visual cues in the opening sequence establish a world in which humans are utterly reliant on technology and yet totally unaware of the nefarious uses to which a brilliant but unethical person could put it.

Author's Note: Thanks to my literature students whose in-class contributions sharpened my thinking on this scene .

[ Ed.: The piece concludes by tying the main themes of the opening sequence to those of the entire film. In doing this, the conclusion makes an argument for the essay's own relevance: we need to pay attention to the essay's points so that we can achieve a rich understanding of the movie. The piece's final sentence makes a chilling final impression by alluding to the danger that might loom if we do not understand the movie. This is the only the place in the piece where the author explicitly references how badly we might be hurt by ignorance, and it's all the more powerful for this solitary quality. A pithy, charming note follows, acknowledging that the author's work was informed by others' input (as most good writing is). Beautifully done. ]

There is NO AI content on this website. All content on TeachWithMovies.org has been written by human beings.

- FOR TEACHERS

- FOR PARENTS

- FOR HOME SCHOOL

- TESTIMONIALS

- SOCIAL MEDIA

- DMCA COMPLIANCE

- GRATUITOUS VIOLENCE

- MOVIES IN THE CLASSROOM

- PRIVACY POLICY

- U.S. HISTORY

- WORLD HISTORY

- SUBJECT MATTER

- APPROPRIATE AGE LEVEL

- MORAL/ETHICAL EMPHASIS

- SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL LEARNING

- SNIPPETS & SHORT SUBJECTS

- MOVIES BY THE CALENDAR

- DOCUMENTARIES & NON-FICTION

- TALKING AND PLAYING WITH MOVIES: AGES 3-8

- TWM’S BEST TEACHING FILMS

- TALKING AND PLAYING WITH MOVIES

- SET-UP-THE-SUB

- ARTICLES & STUDENT HANDOUTS

- MOVIE PERMISSION SLIP

- MOVIE & TELEVISION WORKSHEETS

- MATHEMATICS

- EARTH SCIENCE

- ANY FILM THAT IS A WORK OF FICTION

- FILM ADAPTATIONS OF NOVELS, SHORT STORIES, OR PLAYS

- ANY FILM THAT IS A DOCUMENTARY

- ANY FILM THAT EXPLORES ETHICAL ISSUES

- ADAPTATION OF A NOVEL

- DOCUMENTARIES

- HERO’S JOURNEY

- SCIENCE FICTION

- WORK OF FICTION

- WORK OF HISTORICAL FICTION

- PERSUASIVE DOCUMENTARY

- FICTION (SOAPS, DRAMAS, AND REALITY/SURVIVAL SHOW)

- HISTORICAL FICTION

- INFORMATIONAL DOCUMENTARY

- NEWS AND CURRENT EVENTS

- SEARCH [Custom]

Lesson Plans Using Film Adaptations of Novels, Short Stories or Plays

— with discussion questions and assignments.

For a list of movies frequently shown as adaptations of literary works, see TWM’s Adaptations Index .

Used appropriately, movies based on novels or short stories can supplement units based on the written original, enhance students’ interest in analyzing the written work, and motivate classes to excel in completing assignments that teach the skills required by the ELA curriculum. Filmed versions of plays supply the same benefits and often provide an experience that is close to viewing a live performance. Studying a cinematic adaptation of a literary work will show students how words are converted to visual media and allow a comparison of the written original to the cinematic version, permitting teachers to highlight the techniques of both film and the written word in telling a story. Presenting a filmed adaptation with high production values will demonstrate that movies can be an art form which communicates differently, but no less importantly, than the written word. Moreover, when used as a reward for having read a novel, a filmed adaptation can demonstrate that novel-length works of fiction usually contain a wealth of detail, information, and subplot that cannot be included in a movie. For all of these reasons, filmed adaptations of novels, short stories, or plays, are excellent resources for lessons requiring students to learn and exercise the analytical and writing skills required by ELA curriculum standards.

Note that novels and short stories can be analyzed for their use of the devices of fiction. Plays employ most of the devices of fiction but add the theatrical devices of music, sound effects, lighting, acting, set design, etc. Movies employ most of the fictional and theatrical devices as well as a separate set of cinematic techniques such as shot angle, focus, editing, etc. This essay focuses of the literary devices shared by written works, theatrical works, and film. For an analysis of theatrical and cinematic devices, see TWM’s Introducing Cinematic and Theatrical Elements in Film .

I. SHOWING THE FILM BEFORE READING A NOVEL, SHORT STORY, OR THE SCRIPT OF A PLAY

Usually, a filmed adaptation of a written work is best shown after a novel or short story has been read by students. This avoids the problem of students watching the movie in place of reading the book or story. However, in certain instances, where the written work is hard to follow or when students have limited reading skills, it is better to show the film before reading the written work or to show segments of the film while the writing is being read. Students who have difficulty reading a novel or a short story can often follow the conflicts, complications, and resolutions in a screened version that they would otherwise miss. For example, obscure vocabulary and difficult sentence structure in The Scarlet Letter and Billy Budd make these classics difficult reading for today’s students. The PBS version of The Scarlet Letter and the Ustinov version of Billy Budd are excellent adaptations which can serve as an introduction and make the reading more understandable. Viewing a filmed adaptation of a book by Jane Austen enables students to understand the story and avoid getting lost in the language as they read. (See “Emma Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility as Gateway to Austen’s Novel” by Cheryl L. Nixon, contained in Jane Austen in Hollywood, Edited by Linda Troost and Sayre Greenfield, 1998, University of Kentucky Press, pages 140 – 147.)

Plays, which were meant to be watched rather than read, are usually a different matter. Viewing a staged presentation with actors, a set, sound, and lighting is an experience more like watching a movie than reading a script. One of the few exceptions are the plays of Shakespeare which are usually better when read and studied before they are seen. Students need to be introduced to the Bard’s language in order appreciate a performance.

II. SCREENING ALL OR PART OF THE MOVIE IN SEGMENTS

A film can be segmented, or chunked, and shown before or after the corresponding segment is read by students studying the novel, story or play on which the movie is based. Have students keep up with the reading so that the timing is accurate and the events in the film do not get ahead of their presentation in the written work.

Several of the assignments suggested in Section IV can be modified for segmented viewing. The following assignment will allow students to exercise their analytical and writing skills after a segment of the film has been shown. The assignments can be modified to focus on specific elements of fiction or literary devices.

Discussion Question: What is the difference in the presentation of the story between this segment of the film and the corresponding sections of the [novel/story/play]? [Lead students into a discussion of any important elements of fiction or literary devices which are present in both or which are present in one but not the other.]

Assignment: [Describe a scene in the film.] Compare this segment of the movie with the corresponding sections of the [novel/story/play]. Cite specific examples to illustrate how the presentation in the two media either differ or are the same. Your comparison should include: (1) any elements of fiction and literary devices which are present in both or which are present in one but not in the other; (2) a discussion of the tone of the two presentations; and (3) an evaluation of the two presentations stating which you think is more effective in communicating the ideas contained in the story, including your reasons for that opinion. When you refer to the [novel/story/play], list specific pages on which the language you are referring to appears.

III. WATCHING THE MOVIE AFTER THE BOOK HAS BEEN READ

Comparing film adaptations with their literary sources can enhance students’ ability to analyze, think, and critique the writing, imagery, and tone of a literary work. Differences between the movie and the written work can be used to explicate various literary devices. The discussion questions and assignments set out below, as they are written or modified to take into account the needs of the class, will assist teachers in making good use of a filmed adaptation of a novel, short story, or play.

Before showing the film, think about whether you want to point the students’ attention toward any issues that you want them to think about as they watch the movie. This could be the use of a motif or other literary device or changes in theme. Many of the discussion question and assignments set out below can be easily adapted to be given to students before they watch the film, the discussion to be held, and the assignment completed after the movie is over.

IV. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ASSIGNMENTS FOR USE WITH FILMED ADAPTATIONS

Fill in the blanks with a number appropriate to the abilities of the class and the relationship of the written work to the filmed adaptation. To make sure that students complete the assigned reading, the exercises set out below require a thorough knowledge of the written work with references to page numbers of the text.

- Discussion Question: How is the presentation of [name a major character who appears in both versions] different in the [book/story/play] and the movie? [Follow up with:] Why did the filmmakers change the way in which this character was presented?

Assignment: Describe _____ characters which appear in both the film and the [book/story/play]. At least one of them should be a minor character. Specify how dialogue, action, and physical appearance in the movie define the individual. Using direct quotes from the written work, citing page numbers, describe the characters using the same criteria. Evaluate which presentation is best in allowing either the viewer or the reader to fully grasp the nature of the characters.

- Discussion Question: Were any scenes described in the [book/story/play] substantially altered in the filmed adaptation? [Follow up with:] Why did the filmmakers change the scene?

Assignment: Select at least _____ scenes from the film that were altered considerably from similar scenes described in the [novel/story/play]. Use direct reference to details in order to illustrate the differences. Cite specific page numbers when you are referring to anything appearing in the [book/story/script]. Evaluate the changes in terms of how well the intention of the scene is made manifest in either media.

- Discussion Question: What elements of fiction appear in the [book/story/play] but not in the film? Did this detract from the quality of the story told by the movie?

Assignment: Note _____ examples of elements of fiction that have been left out of the film but seem important in the [book/story/play]. Suggest reasons that may justify the elimination of the scenes, characters, subplots, or settings. Be sure to use direct reference, with page numbers, to the written work in order to support the opinion offered.

- Discussion Question: Did the filmmakers add any characters or events that do not appear in the [book/story/play]? Did this help to tell the story first suggested in the literary work?

Assignment: Often in movies, the screenwriters will add characters or events that do not appear in the original [book/story/play]. Note _____ examples of these additions and suggest reasons that they may have been written into the film.

- Discussion Question: How does the tone of the story told in the film differ from the tone of the story told in the [book/story/play]?

Assignment: Evaluate the tone created in the movie. Cite clear examples of color, visuals, editing, and music that may have contributed to the tone of any particular scene. Compare the tone created in the film to the tone created in the [book/story/play] using the same scene. Cite specific examples, giving page numbers, of the description that created the tone in the written work.

- Discussion Question: Did this film change the theme or any of the ideas presented in the [novel/story/play]? What were they? Did these changes improve on the story underlying both the written work and the movie?

Assignment: Ideas are the reasons stories are told. Themes are the major ideas in a story; however, most stories contain other ideas as well. Some films change the ideas presented in the work of literature from which they were adapted. Pay close attention to theme and other ideas in both the written version and in the movie and write about how they were changed. Evaluate the changes.

- Discussion Question: Which told the story better, the [novel/story/play] or the movie?

Assignment: Often a story will seem to be deprived of beauty or meaning by the changes made in a filmed adaptation. On other occasions, the experience of the written story will be enriched by watching a filmed version. Write an informal essay stating your opinion of the quality of the story told by the movie as compared to the [novel/story/play]. Justify your opinion with direct reference to both the film and the written work; for the latter, cite the specific page numbers for the passages on which you rely.

- Discussion Question: Compare the settings of the story in the written work and in the movie. Is the movie faithful to the [novel/short story/play] in terms of the settings used?

Assignment: How do the settings in the movie reflect the images of place found in the [novel/story/play]? Describe specific details in both the film and the work of literature that support your conclusion. When referring to the written work, cite page numbers.

- Discussion Question: Compare the use of visual images in the movie and in the [novel/story/play] in the description of the various characters.

Assignment: Using specific examples of written descriptions in the literary work and visuals in the movie, discuss the presentation of character contained in both.

- Discussion Question: Describe any important differences in theme between the story appearing in the written work and the story told on screen.

Assignment: Attitude toward subject, meaning the basic topic (such as war, love, politics) can shift dramatically between a [novel/story/play] and its movie adaptation. Explain through example any changes that can be seen between the attitude toward the subject expressed by the filmmakers and presented by the author of the [book/story/play].

- Discussion Question: Were any important motifs, symbols, or allusions included in the work of literature missing or changed in the movie adaptation? Why do you think the filmmakers made these changes?

Assignment: Important motifs, symbols, or allusions contained in a written work of fiction are sometimes missing or changed in the movie. Specify examples of these literary tools that are not a part of the filmed adaptation. Note any replacement motifs, symbols or allusions contained in the movie.

- Discussion Question: What, if any, were the changes in the plot between the [book/story/play] and the film?

Assignment: Rising action, an important part in the plots of both written fiction and movies, may be different in filmed adaptations. Note any changes. Describe details which are important in the written work that have been removed from the movie and details which are not in the [book/story/play] which have been added by the filmmakers. When referring to the written work, give the page numbers of any passages or details to which you refer. Justify the changes.

- Discussion Question: Which ending did you like better, the conclusion of the [book/story/play] or the way in which the movie ended? Explain why.

Assignment: Compare the ending of the [book/story/play] to the ending of the film. Illustrate how any differences either reiterate or obscure the intention of the original work. Cite specifics and support all assertions.

Movies with screenplays that are carefully adapted from novels, short stories, and plays can be an important part of lesson planning. Using the techniques described above, teachers can make film adaptations an integral part of the learning process.

Written by Mary RedClay and James Frieden .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

55 Writing about the Novel: Film Comparison

You began the process of writing your literary comparison paper in the Introduction to the Novel chapter by choosing an essay, reading it carefully, and writing a personal response. In this chapter, we will move through the remaining steps of writing your paper.

Step 3: Choose a Film for Comparison

The key to a good comparison essay is to choose two subjects that connect in a meaningful way. The purpose of conducting the comparison is not to state the obvious, but rather to illuminate subtle differences or unexpected similarities.

When writing a film comparison paper, the point is to make an argument that will make your audience think about your topic in a new and interesting way. You might explore how the novel and the film present the theme…or how the novel and the film explore the identity of a main character…or…the options are limitless. Here’s a quick video giving you a little overview of what a film vs novel comparison might look like:

To this end, your next goal is to choose a film adaptation of your novel. Some novels may only have one, but some have many that have been created over the last 100 years! Your adaptation could be a feature film, a YouTube short, or an indie film. Choose one that allows you to make an interesting point about the portrayal of the theme of the novel and the film.

Step 4: Research

Once you’ve chosen a second piece, it’s time to enter into the academic conversation to see what others are saying about the authors and the pieces you’ve chosen.

Regardless of the focus of your essay, discovering more about the author of the text you’ve chosen can add to your understanding of the text and add depth to your argument. Author pages are located in the Literature Online ProQuest database. Here, you can find information about an author and his/her work, along with a list of recent articles written about the author. This is a wonderful starting point for your research.

The next step is to attempt to locate articles about the text and the film themselves. For novels, it’s important to narrow down your database choices to the Literature category. For essays, you might have better luck searching the whole ProQuest library with the ProQuest Research Library Article Databases or databases like Flipster that include publications like newspapers and magazines.

Finally, you might look for articles pertinent to an issue discussed in the novel. For example, The Grapes of Wrath is about the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, but it also contains an environmental theme. Depending on what aspect you want to highlight in your comparison, you might look for articles about the Great Depression or about farming and the environment.

Remember, it is helpful to keep a Research Journal to track your research. Your journal should include, at a minimum, the correct MLA citation of the source, a brief summary of the article, and any quotes that stick out to you. A note about how you think the article adds to your understanding of the topic or might contribute to your project is a good addition, as well.

Step 5: Thesis & Outline

Similar to other academic essays, the film comparison essay starts with a thesis that clearly introduces the two subjects that are to be compared and the reason for doing so.

This video highlights some of the key differences between novels and films:

Begin by deciding on your basis for comparison. The basis of comparison could include items like a similar theme, differences in the focus of the piece, or the way both pieces represent an important issue.

This article gives some helpful advice on choosing a topic.

Once you’ve decided on the basis of comparison, you should focus on the points of comparison between the two pieces. For example, if you are focusing on how the literary elements and the cinematic elements used impact the message, you might make a table of each of these elements. Then, you’d find examples of each element from each piece. Remember, a comparison includes both similarities and differences.

By putting together your basis of comparison and your points of comparison, you’ll have a thesis that both makes an argument and gives readers a map of your essay.

A good thesis should be:

- Statement of Fact: “The novel and the film of Pride and Prejudice are similar in many ways.”

- Arguable: “The film version of Pride and Prejudice changes key moments in the text that alter the portrayal of the theme.”

- Personal Opinion: “‘The novel is definitely better than the movie.”

- Provable by the Texts: “Both the novel and the film focus on the importance of identity.”

- Obvious: “The movie provides a modern take on the novel.”

- Surprising: “Though the movie stays true to the original themes of the novel, the modern version may lead viewers to believe that the characters in the book held different values than are portrayed in the novel.”

- General: “Both the novel and the film highlight the plight of women.”

- Specific: “The novel and the film highlight the plight of women by focusing on specific experiences of the protagonist. “

The organizational structure you choose depends on the nature of the topic, your purpose, and your audience. You may organize compare-and-contrast essays in one of the following two ways:

- Block: Organize topics according to the subjects themselves, discussing the novel and then the film.

- Woven: Organize according to individual points, discussing both the novel and the film point by point.

Exercises: Create a Thesis and Outline

You’ll want to start by identifying the theme of both pieces and deciding how you want to tie them together. Then, you’ll want to think through the points of similarity and difference in the two pieces.

In two columns, write down the points that are similar and those that are different. Make sure to jot down quotes from the two pieces that illustrate these ideas.

Following the tips in this section, create a thesis and outline for your novel/film comparison paper.

Here’s a sample thesis and outline:

Step 6: Drafting Tips

Once you have a solid thesis and outline, it’s time to start drafting your essay. As in any academic essay, you’ll begin with an introduction. The introduction should include a hook that connects your readers to your topic. Then, you should introduce the topic. In this case, you will want to include the authors and title of the novel and the director and title of the film. Finally, your introduction should include your thesis. Remember, your thesis should be the last sentence of your introduction.

In a film comparison essay, you may want to follow your introduction with background on both pieces. Assume that your readers have at least heard of either the novel or the film, but that they might not have read the novel or watched the film–or both–…or maybe it’s been awhile. For example, if you were writing about Pride and Prejudice , you might include a brief introduction to Austen and her novel and an introduction to the version of the film you’ve chosen. The background section should be no more than two short paragraphs.

In the body of the paper, you’ll want to focus on supporting your argument. Regardless of the organizational scheme you choose, you’ll want to begin each paragraph with a topic sentence. This should be followed by the use of quotes from your two texts in support of your point. Remember to use the quote formula–always introduce and explain each quote and the relationship to your point! It’s very important that you address both literary pieces equally, balancing your argument. Finally, each paragraph should end with a wrap up sentence that tells readers the significance of the paragraph.

Here are some transition words that are helpful in tying points together: