What is Self-Regulation? (+95 Skills and Strategies)

This is a question that you might hear from kids, and it perfectly encapsulates what baffles them about adults.

As adults, we pretty much have free rein to do whatever we want, whenever we want. The vast majority of us won’t get arrested for not showing up to work, and no one will haul us off to prison for eating cake for breakfast.

So, why do we show up for work? Why don’t we eat cake for breakfast?

Perhaps the better question is, how do we keep ourselves from shirking work when we don’t want to go? How do we refrain from eating cake for breakfast and eating healthy, less-delicious food instead?

The answer is self-regulation. It’s a vital skill, but it’s also something we generally do without much thought.

If you want to learn more about what self-regulation is, how we make the decisions we make, and why we are more susceptible to temptation at certain moments, read on. We also provide plenty of resources for teaching self-regulation skills to both children and adults.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you increase the compassion and kindness you show yourself but will also give you the tools to help your clients, students, or employees show more compassion to themselves.

This Article Contains:

What is self-regulation.

- What Is Self-Regulation Theory?

The Psychology of Self-Regulation

The self-regulatory model, why self-regulation is important for wellbeing, self-regulation test and assessment, early childhood and child development, self-regulation in adults, activities and worksheets for training self-regulation (pdfs), further resources, interventions, and tools, a take-home message.

Andrea Bell from GoodTherapy.org has a straightforward definition of self-regulation: It’s “control [of oneself] by oneself” (2016).

Self-control can be used by a wide range of organisms and organizations, but for our purposes, we’ll focus on the psychological concept of self-regulation.

As Bell also notes:

“Someone who has good emotional self-regulation has the ability to keep their emotions in check. They can resist impulsive behaviors that might worsen their situation, and they can cheer themselves up when they’re feeling down. They have a flexible range of emotional and behavioral responses that are well matched to the demands of their environment”

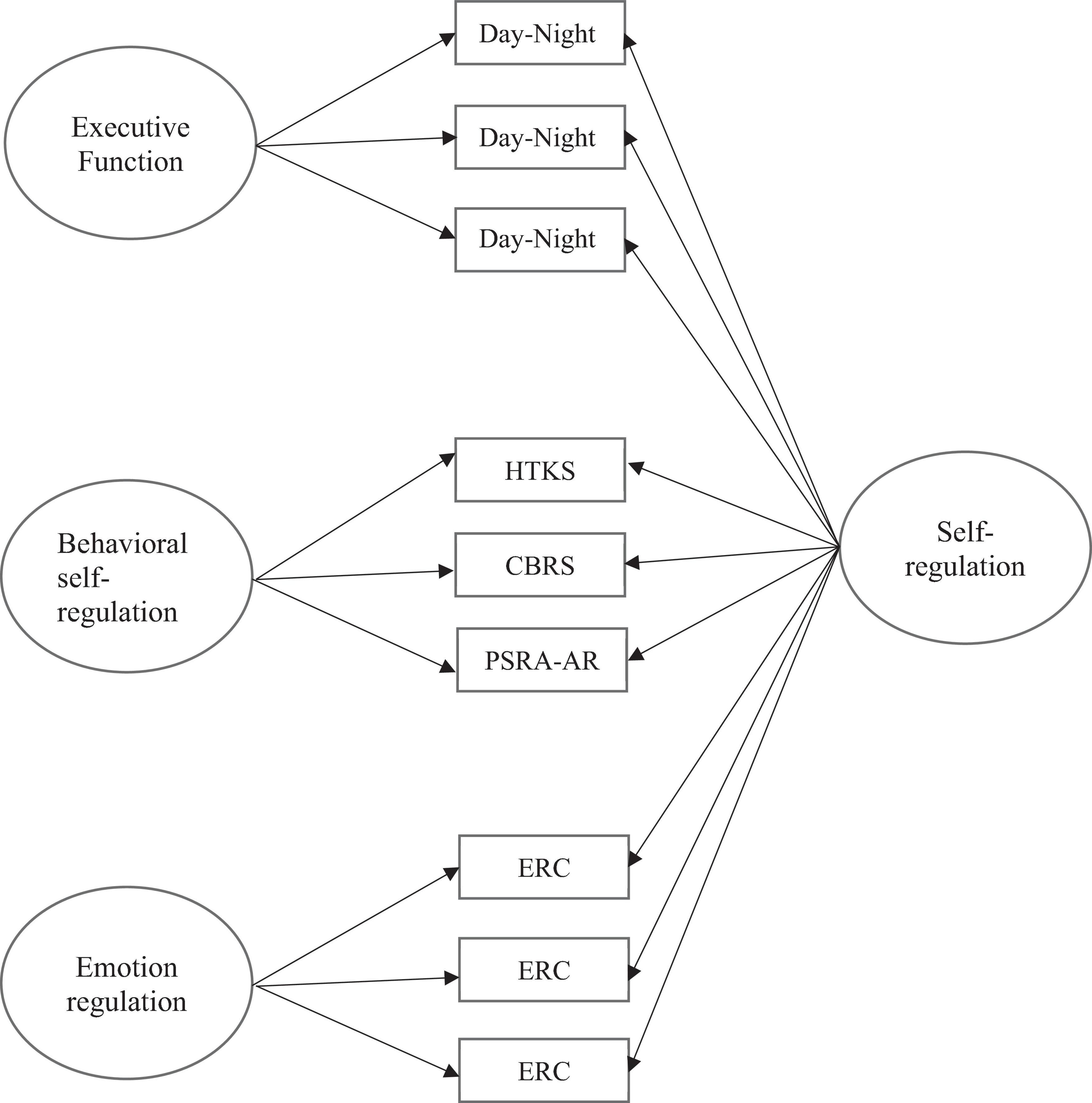

The goal of most types of therapy is to improve an individual’s ability to self-regulate and to gain (or regain) a sense of control over one’s behavior and life. Psychologists might be referring to one of two things when they use the term “self-regulation”: behavioral self-regulation or emotional self-regulation . We’ll explore the difference between the two below.

What Is Behavioral Self-Regulation?

Behavioral self-regulation is “the ability to act in your long-term best interest, consistent with your deepest values” (Stosny, 2011). It is what allows us to feel one way but act another.

If you’ve ever dreaded getting up and going to work in the morning but convinced yourself to do it anyway after remembering your goals (e.g., a raise, a promotion) or your basic needs (e.g., food, shelter), you displayed effective behavioral self-regulation.

What Is Emotional Self-Regulation?

On the other hand, emotional self-regulation involves control of—or, at least, influence over—your emotions.

If you had ever talked yourself out of a bad mood or calmed yourself down when you were angry, you were displaying effective emotional self-regulation.

What is Self-Regulation Theory?

Self-regulation theory (SRT) simply outlines the process and components involved when we decide what to think, feel, say, and do. It is particularly salient in the context of making a healthy choice when we have a strong desire to do the opposite (e.g., refraining from eating an entire pizza just because it tastes good).

According to modern SRT expert Roy Baumeister, there are four components involved (2007):

- Standards of desirable behavior;

- Motivation to meet standards;

- Monitoring of situations and thoughts that precede breaking standards;

- Willpower allowing one’s internal strength to control urges.

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you to help others create a kinder and more nurturing relationship with themselves.

Download 3 Free Self-Compassion Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

According to Albert Bandura , an expert on self-efficacy and a leading researcher of SRT, self-regulation is a continuously active process in which we:

- Monitor our own behavior, the influences on our behavior, and the consequences of our behavior;

- Judge our behavior in relation to our own personal standards and broader, more contextual standards;

- React to our own behavior (i.e., what we think and how we feel about our behavior) (1991).

Bandura also notes that self-efficacy plays a significant role in this process, exerting its influence on our thoughts, feelings, motivations, and actions.

A quick thought experiment can show the significance of self-efficacy:

Imagine two people who are highly motivated to lose weight. They are both actively monitoring their food intake and their exercise, and they have specific, measurable goals that they have set for themselves.

One of them has high self-efficacy and believes he can lose weight if he puts in the effort to do so. The other has low self-efficacy and feels that there’s no way he can hold to his prescribed weight loss plan.

Who do you think will be better able to say no to second helpings and decadent desserts? Which of them do you think will be more successful in getting up early to exercise each morning?

We can say with reasonable certainty that the man with higher self-efficacy is likely to be more effective, even if both men start with the exact same standards, motivation, monitoring, and willpower.

Barry Zimmerman, another big name in SRT research, put forth his own theory founded on self-regulation: self-regulated learning theory.

We explore this further in The Science of Self-Acceptance Masterclass© .

What is Self-Regulated Learning?

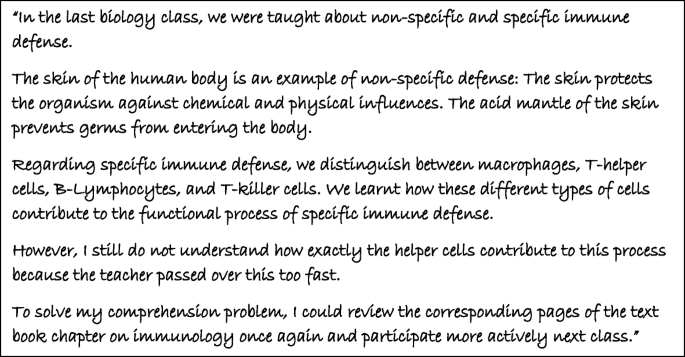

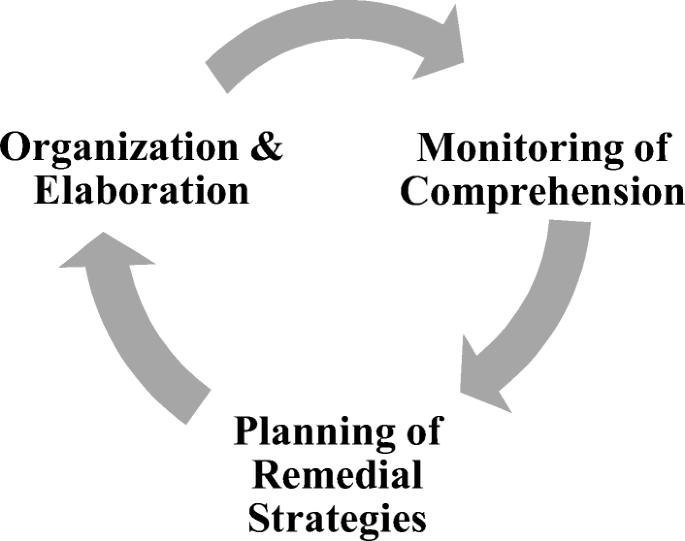

Self-regulated learning (SRL) refers to the process a student engages in when she takes responsibility for her own learning and applies herself to academic success (Zimmerman, 2002).

This process happens in three steps:

- Planning: The student plans her task, sets goals, outlines strategies to tackle the task, and/or creates a schedule for the task;

- Monitoring: In this stage, the student puts her plans into action and closely monitors her performance and her experience with the methods she chose;

- Reflection: Finally, after the task is complete and the results are in, the student reflects on how well she did and why she performed the way she did (Zimmerman, 2002).

When students take initiative and regulate their own learning, they gain deeper insights into how they learn, what works best for them, and, ultimately, they perform at a higher level. This improvement springs from the many opportunities to learn during each phase:

- In the planning phase, students have an opportunity to work on their self-assessment and learn how to pick the best strategies for success;

- In the monitoring phase, students get experience implementing the strategies they chose and making real-time adjustments to their plans as needed;

- In the reflection phase, students synthesize everything they learned and reflect on their experience, learning what works for them and what should be altered or replaced with a new strategy.

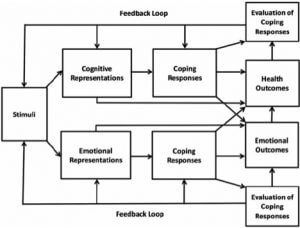

While the model is specific to health- and illness-related (rather than emotional) self-regulation, it is still a good representation of the complex processes at work during self-regulation of any kind.

The figure to the right shows how the model works:

- Stimuli are presented (i.e., something happens that provokes a reaction, whether it’s a thought, something another person said, receiving significant news, etc.);

- The individual makes sense of the stimuli, both cognitively (understanding it) and emotionally (feeling it);

- The sense-making leads the individual to choose coping responses (i.e., what the person does to influence her feelings about the stimuli or the actions she takes to address the stimuli);

- The sense-making and coping responses determine the outcomes (i.e., the individual’s overall response and how she chooses to behave);

- The individual evaluates her coping responses in light of these outcomes and determines whether to continue using the same coping responses or to alter her formula.

An Example of the Model in Action

If words like “stimuli” and “emotional representations” throw you off, perhaps an example of the model in action will help.

Let’s use Bob as our example.

Bob was just diagnosed with diabetes and is facing his new reality: having to check his blood sugar regularly, changing his diet, and getting comfortable with needles. The diagnosis is Bob’s stimulus .

Bob attempts to make sense of his diagnosis. He talks to his doctor, recalls a friend’s experience with diabetes, thinks about a character’s struggle with diabetes on his favorite TV show, and tries to remember what he learned about diabetes in his college health classes. All of this information feeds into his cognitive representation of his diagnosis.

It’s not all objective thoughts, though. Bob also feels a little shocked about getting this diagnosis since he hadn’t even considered that he might have diabetes. He is worried about how long he’ll be around for his kids and is anxious about how much his life will change. He’s also scared about what will happen if he doesn’t change his life. These feelings make up his emotional representation of his diagnosis.

Once Bob has a semi-firm grasp of his thoughts and feelings about the diagnosis, he makes some decisions about what comes next. Through discussions with his doctor, he decides to start a new, healthier diet and commits to taking frequent walks. However, he also finds that it’s easy to put his diagnosis out of his mind when he’s not having an episode or being directly affected by it.

These decisions and actions are his coping responses .

Bob implements these responses for a few days, then reflects on how he’s been doing. He realizes that, although he is eating marginally healthier and he’s taken a short walk each day, he has mostly refrained from thinking about his diagnosis at all.

Bob reminds himself that if he keeps ignoring his diabetes, he will eventually get sick and may even suffer significant, long-term consequences. This is his evaluation of his representations and coping methods .

Bob commits to facing his diabetes head-on instead of denying it and resolves to work on remembering the potential consequences of not staying healthy. He also resolves to embrace fully the diet he and his doctor planned out and to start going to the gym three times a week.

Bob is using his evaluation of his representations, coping responses, and outcomes to assess how well his actions align with his desired future: a happy and healthy Bob who is around to see his kids grow up. This is the feedback loop .

This example is a good representation of what self-regulation looks like. Essentially, it’s the process of monitoring your own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; comparing the outcomes against your goals; then deciding whether to maintain your current attitudes and behaviors or to adjust them in order to meet your goals more effectively.

What is Self-Regulation Therapy?

As noted earlier, you could argue that all forms of therapy are centered on self-regulation—they all aim to help clients reach levels of equilibrium in which they are able to effectively regulate their own emotions and behaviors (and, sometimes, thought patterns, in the case of therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy ).

However, there is also a form of therapy that is specifically designed with self-regulation theory and its principles in mind. Self-regulation therapy draws from research findings in neuroscience and biology to help clients reduce “excess activation in the nervous system” (Canadian Foundation for Trauma Research & Education, n.d.).

This excess activation (i.e., an off-balance or inappropriate fight-or-flight response) can be triggered by a traumatic incident or any life event that is significant or overwhelming.

Self-regulation therapy aims to help the client correct this problem, building new pathways in the brain that allow for more flexibility and more appropriate emotional and behavioral responses. The ultimate goal is to turn emotional and/or behavioral dysregulation into effective self-regulation.

Self-Regulation Versus Self-Control

If you’re thinking that self-regulation and self-control have an awful lot in common, you’re correct. They are similar concepts and they deal with some of the same processes. However, they are two distinct constructs.

As psychologist Stuart Shanker (2016) put it:

“Self-control is about inhibiting strong impulses; self-regulation [is about] reducing the frequency and intensity of strong impulses by managing stress-load and recovery. In fact, self-regulation is what makes self-control possible, or, in many cases, unnecessary.”

Viewed in this light, we can think about self-regulation as a more automatic and subconscious process (unless the individual determines to purposefully monitor or alter his or her self-regulation), while self-control is a set of active and purposeful decisions and behaviors.

Understanding Ego Depletion

An important SRT concept is that of self-regulatory depletion, also called ego depletion.

This is a state in which an individual’s willpower and control over self-regulation processes have been used up, and the energy earmarked for inhibiting impulses has been expended. It often results in poor decision-making and performance (Baumeister, 2014).

When a person has been faced with many temptations (especially strong temptations), he or she must exert an equally powerful amount of energy when it comes to controlling impulses. SRT argues that people have a limited amount of energy for this purpose, and once it’s gone, two things happen:

- Inhibitions and behavioral restraints are weaker, meaning that the individual has less motivation and willpower to refrain from the temptations;

- The temptations, desires, or urges are felt much more strongly than when willpower is at a normal, non-depleted level (Baumeister, 2014).

This is a key idea in SRT. It explains why we struggle to avoid engaging in “bad behavior” when we are tempted by it over a long period of time. For example, it explains why many dieters can keep to their strict diet all day but once dinner’s over they will give in when tempted by dessert.

It also explains why a married or otherwise committed person can rebuff an advance from someone who is not their partner for days or weeks but might eventually give in and have an affair.

Recent neuroscience research supports this idea of self-regulatory depletion. A study from 2013 by Wagner and colleagues used functional neuroimaging to show that people who had depleted their self-regulatory energy experienced less connectivity between the regions of the brain involved in self-control and rewards.

In other words, their brains were less accommodating in helping them resist temptation after sustained self-regulatory activity.

5 Examples of Self-Regulatory Behavior

Although self-regulatory depletion is a difficult hurdle, SRT does not imply that it is impossible to remain in control of your urges and behavior when your energy is depleted. It merely states that it becomes harder and harder as your energy level decreases.

However, there are many examples of successful self-regulatory behavior, even when the individual is fatigued from constant self-regulation.

Examples include:

- A cashier who stays polite and calm when an angry customer is berating him for something he has no control over;

- A child who refrains from throwing a tantrum when she is told she cannot have the toy she desperately wants;

- A couple who’s in a heated argument about something that is important to both of them deciding to take some time to cool off before continuing their discussion, instead of devolving into yelling and name-calling;

- A student who is tempted to join her friends for a fun night out but instead decides to stay in to study for tomorrow’s exam;

- A man trying to lose weight meets a friend at a restaurant and sticks with the “healthy options” menu instead of ordering one of his favorite high-calorie dishes.

As you can see, self-regulation covers a wide range of behaviors from the minute-to-minute choices to the larger, more significant decisions that can have a significant impact on whether we meet our goals.

Let’s take a closer look at how self-regulation helps us in enhancing and maintaining a healthy sense of wellbeing.

Overall, there’s tons of evidence suggesting that those who successfully display self-regulation in their everyday behavior enjoy greater wellbeing. Researchers Skowron, Holmes, and Sabatelli (2003) found that greater self-regulation was positively correlated with wellbeing for both men and women.

The findings are similar in studies of young people. A study from 2016 showed that adolescents who regularly engage in self-regulatory behavior report greater wellbeing than their peers, including enhanced life satisfaction, perceived social support, and positive affect (i.e., good feelings) (Verzeletti, Zammuner, Galli, Agnoli, & Duregger).

On the other hand, those who suppressed their feelings instead of addressing them head-on experienced lower wellbeing, including greater loneliness, more negative affect (i.e., bad feelings), and worse psychological health overall (Verzeletti, Zammuner, Galli, Agnoli, & Duregger, 2016).

Emotional Intelligence and Wellbeing

To get more specific, one of the ways in which self-regulation contributes to wellbeing is through emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence can be described as:

“The ability to perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth”

(Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

According to emotional intelligence expert Daniel Goleman, there are five components of emotional intelligence:

- Self-awareness ;

- Self-regulation;

- Internal motivation;

- Social skills.

Self-regulation, or the extent of an individual’s ability to influence or control his or her own emotions and impulses, is a vital piece of emotional intelligence, and it’s easy to see why: Can you imagine someone with high levels of self-awareness, intrinsic motivation, empathy, and social skills who inexplicably has little to no control over his or her own impulses and is driven by uninhibited emotion?

There’s something off about that picture because of self-regulation’s important role in emotional intelligence . And, as researchers Di Fabio and Kenny found, emotional intelligence is strongly related to wellbeing (2016).

The better we are at understanding and addressing our emotions and the emotions of others, the better we are at making sense of our environments, adjusting to them, and pursuing our goals.

Self-Regulation and the Motivation to Succeed

Speaking of pursuing our goals, self-regulation is also entwined with motivation. As stated earlier in this article, motivation is one of the core components of self-regulation; it is one factor that determines how well we are able to regulate our emotions and behaviors.

An individual’s level of motivation to succeed in his endeavors is directly related to his performance. Even if he has the best of intentions, well-laid plans, and extraordinary willpower, he will likely fail if he is not motivated to regulate his behavior and avoid the temptation to slack off or set his goals aside for another day.

The more motivated we are to achieve our goals, the more capable we are to strive toward them. This impacts our wellbeing by filling us with a sense of purpose, competence, and self-esteem , especially when we are able to meet our goals.

Self-Regulation in ADHD and Autism

As you might have guessed, self-regulation is also an important topic for those struggling with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

One of the hallmarks of ADHD is a limited ability to focus and regulate one’s attention. For example, ADDitude’s Penny Williams (n.d.) describes her 11-year-old son Ricochet’s struggles with ADHD in terms of the struggle to self-regulate:

“At times, he has struggled with identifying his feelings. He is overwhelmed with emotion sometimes, and he has trouble labeling his feelings. You can’t deal with what you can’t define, so this often creates a troublesome situation for him and me. Now that Ricochet is old enough to start regulating his reactions, one of our current behavior goals is identifying, communicating, and regulating feelings and actions.”

Similarly, difficulty with emotional self-regulation is part and parcel of ASD. Those on the autism spectrum often have trouble identifying their emotions. Even if they are able to identify their emotions, they generally have trouble modulating or regulating their emotions.

Difficulty with self-regulation is well-understood as a common symptom of ASD, but effective methods for improving self-regulation in ASD is unfortunately not as well-known or regularly implemented as one might wish.

The nonprofit advocacy group Autism Speaks suggests several strategies for helping children with autism to learn how to self-regulate. Many of these strategies can also be applied to children with ADHD, including:

- Celebrate and build your child’s strengths and successes;

- Respect and listen to your child;

- Validate your child’s concerns and emotions;

- Provide clear expectations of behavior (using visual aids if necessary);

- Set your child up for success (e.g., accepting a one-word answer, providing accommodations, using Velcro instead of shoelaces);

- Ignore the challenging behavior, like screaming or biting;

- Alternate tasks; do something fun, then something challenging;

- Teach and interact at your child’s current level rather than at what level you want him or her to be;

- Give your child choices within strict parameters (e.g., allowing the child to choose what activity to do first);

- Provide access to breaks when needed—this will give him or her an opportunity to avoid bad behavior;

- Promote the use of a safe calm-down place as a positive place, not a place of punishment;

- Set up reinforcement systems to reward your child for desired behavior;

- Allow times and places for your child to do what he or she wants (when not an inconvenience or intrusion for anyone else);

- Reward flexibility and self-control, verbally and with tangible rewards;

- Use positive/proactive language to encourage good behavior rather than pointing out bad behavior (2012).

Helping your child learn to self-regulate more effectively will ultimately benefit you, your child, and everyone he or she interacts with and will improve his or her overall wellbeing.

The Art of Mindfulness

Mindfulness can be defined as the conscious effort to maintain a moment-to-moment awareness of what’s going on, both inside your head and around you. Mindfulness and self-regulation are a powerful combination for contributing to wellbeing.

As we learned earlier, self-regulation requires self-awareness and monitoring of one’s own emotional state and responses to stimuli. Being conscious of your own thoughts, feelings, and behavior is the foundation of self-regulation: Without it, there is no ability to reflect or choose a different path.

Teaching mindfulness is a great way to improve one’s ability to self-regulate and to enhance overall well-being. Mindfulness encourages active awareness of one’s own thoughts and feelings and promotes conscious decisions about how to behave over simply going along with whatever your feelings tell you.

There is good evidence that mindfulness is an effective tool for teaching self-regulation. Researchers Razza, Bergen-Cico, and Raymond recently published a study on the effects of mindfulness-based yoga intervention in preschool children (2015).

The researchers found that those in the mindfulness group exhibited greater attention, better ability to delay gratification and more effective inhibitory control than those in the control group.

Findings also suggested that those with the most trouble self-regulating benefited the most from the mindfulness intervention, indicating that those at the lower end of the self-regulation continuum are not a “lost cause.”

Self-Regulation and Executive Function

These skills are known as executive function skills, and they involve three key types of brain functions:

- Working memory: our cache of short-term memories, or information we recently took in;

- Mental flexibility: our ability to shift our focus from one stimulus to another and apply context-appropriate rules for attention and behavior;[be]

- Self-control: our ability to set priorities, regulate our emotions, and to resist our impulses (Center on the Developing Child, n.d.).

These skills are not inherent but are learned and built over time. They are vital skills for navigating the world and they contribute to good decisionmaking.

When we are able to successfully navigate the world and make good choices, we set ourselves up to meet our goals and enjoy greater wellbeing.

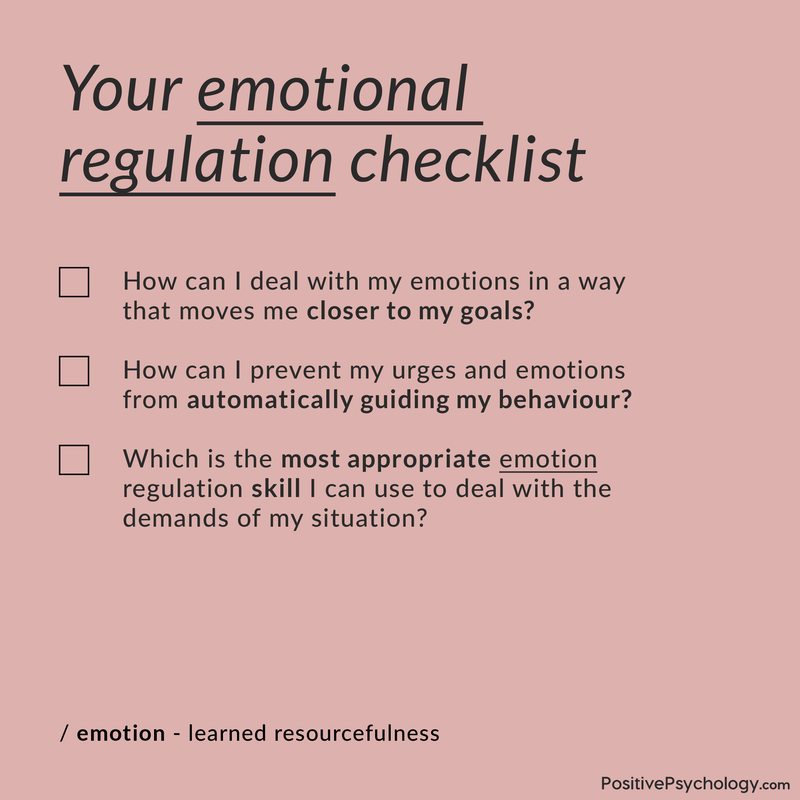

Do you ever find your emotions frustrating, overwhelming, or even rather unbearable? Are you able to cultivate an awareness of these emotions but aren’t really sure what to do next?

After noticing and understanding your emotions, it is important to think about how to deal with or regulate these emotions. There are many ways to do this, but a good place to start is to consider asking yourself the questions in the images below.

The more you challenge yourself to answer these important questions and try out other emotional regulation strategies, the more resources you’ll have to process your emotions effectively. This idea has been termed “learned resourcefulness”.

Research shows people who have learned to be resourceful in this way, have a more diverse range of emotional-regulation strategies in their toolkit to deal with difficult emotions and have learned to consider the demands of a difficult situation before selecting an appropriate strategy.

Importantly, these strategies are equally relevant when attempting to regulate positive emotions like happiness, excitement, and optimism. One may engage in techniques to prolong positive emotions in an attempt to feel better for longer or even inspire motivation and other adaptive behaviors.

If you’re interested in measuring your level of self-regulation (or using it in research), there are two solid options in terms of a self-monitoring scale and self-regulation questionnaire:

- The Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ) for adults (Brown, Miller, & Lawendowski, 1999);

- The Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment (PSRA) for children (Smith-Donald, Raver, Hayes, & Richardson, 2007).

The SRQ is a 63-item assessment measured on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items correspond to one of seven components:

- Receiving relevant information;

- Evaluating the information and comparing it to norms;

- Triggering change;

- Searching for options;

- Formulating a plan;

- Implementing the plan;

- Assessing the plan’s effectiveness.

If you’re interested in learning more about this scale or using it in your own work, visit this website .

If you’re more interested in working with young children on self-regulatory strategies, the PRSA will probably work best for you. It’s described as a portable direct assessment of self-regulation in young children based on a set of structured tasks, including activities like:

- Balance Beam;

- Pencil Tap;

- Tower Task;

- Tower Cleanup.

To learn more about this assessment or to inquire about using it for your research, click here .

What is self-regulation? – Empowered to Connect

As noted earlier, the development of self-regulation begins very early on. As soon as children are able to access working memory, exhibit mental flexibility, and control their behavior, you can get started with helping them develop self-regulation.

How to Teach and Develop Self-Regulation in Toddlers

So, you’re probably convinced that self-regulation in children is a good thing, but you might be wondering, Where do I begin?

If that captures your thought process, don’t worry. We have some tips and suggestions to get you started.

Here’s a good list of suggestions from Day2Day Parenting for supporting the self-regulation of very young children (e.g., toddlers and preschoolers):

- Provide a structured and predictable daily routine and schedule;

- Change the environment by eliminating distractions: turn off the tv, dim lights, or provide a soothing object (like a teddy bear or a photo of the child’s parent[s]) when you sense a child is becoming upset;

- Roleplay with the child to practice how to act or what to say in certain situations;

- Teach and talk about feelings and review home/classroom rules regularly;

- Allow children to let off steam by creating a quiet corner with a small tent or pile of pillows;

- Encourage pretend play scenarios among preschoolers;

- Stay calm and firm in your voice and actions even when a child is “out of control”;

- Anticipate transitions and provide ample warning to the child or use picture schedules or a timer to warn of transitions;

- Redirect inappropriate words or actions when needed;

- In the classroom or at playgroups, pair children with limited self-regulatory skills with those who have good self-regulatory skills as a peer model;

- Take a break yourself when needed, as children with limited self-regulatory skills can test an adult’s patience (Thrive Place, 2013).

15 Activities and Games for Kindergarten and Preschool Children

Check out the resources listed below for some fun and creative ideas for kindergarten and preschool children.

Classic Games

We titled these the “classic games” because they are popular, well-known games that you are probably already familiar with. Luckily, they can also be used to help your child develop self-regulation.

If you haven’t already, give these a try:

- Duck, Duck, Goose

- Hide and Seek

- Musical Chairs

- Mirror, Mirror

Some further suggestions come from the Your Therapy Source website (2017):

- Red Light, Green Light : Kids move after “green light” is called and freeze when “red light” is called. If a kid is caught moving during a red light, they’re out;

- Mother May I : One child is the leader. The rest of the children ask: “Mother may I take [a certain number of steps, hops, jumps, or leaps to get to the leader] ? The leader approves or disapproves of the action. The first child to touch the leader wins;

- Freeze Dance : Turn on music. When the music stops, the children have to freeze;

- Follow My Clap : The leader creates a clapping pattern. Children have to listen and repeat the pattern;

- Loud or Quiet : Children have to perform an action that is either loud or quiet. First, pick an action, i.e., stomping feet. The leader says “loud,” and the children stomp their feet loudly.

- Simon Says : Children perform an action as instructed by the leader, but only if the leader starts with, “Simon says . . .” For example, if the leader says, “Simon says touch your toes,” then all the children should touch their toes. If the leader only says, “Touch your toes,” no one should touch their toes because Simon didn’t say so;

- Body Part Mix-Up : The leader will call out body parts for the children to touch. For example, the leader might call out “knees,” and the children touch their knees. Create one rule to start; for example, each time the leader says “head” the kids will touch their toes instead of their heads. This requires the children to stop and think about their actions and not just to react. The leader calls out “knees, head, elbow.” The children should touch their knees, toes , and elbow. Continue practicing and adding other rules that change body parts;

- Follow the Leader : The leader performs different actions and the children have to follow those actions exactly;

- Ready, Set, Wiggle : If the leader calls out, “Ready . . . Set . . . Wiggle,” everyone should wiggle their bodies. If the leader calls out, “Ready . . . Set . . . Watermelon,” no one should move. If the leader calls out, “Ready . . . Set . . . Wigs,” no one should move. The game continues like this. You can change the commands to whatever wording you want. The purpose is to have the children waiting to move until a certain word is said out loud;

- Color Moves : Explain to the children that they will walk around the room. They’ll move based on the color of the paper you are holding up. Green paper means walk fast, yellow paper means regular pace, and blue paper means slow-motion walking. Whenever you hold up a red paper, they stop. Try different locomotor skills like running in place, marching, or jumping.

Another list from The Inspired Treehouse includes good suggestions for other games you can play to calm an emotional or overwhelmed child when you’re on an outing. You can find that list here .

Self-Regulation in Adolescence

As your child grows, you will probably find it harder to encourage continuing self-regulation skills. However, adolescence is a vital time for further development of these skills, particularly for:

- Persisting on complex, long-term projects (e.g., applying to college);

- Problem-solving to achieve goals (e.g., managing work and staying in school);

- Delaying gratification to achieve goals (e.g., saving money to buy a car);

- Self-monitoring and self- rewarding progress on goals;

- Guiding behavior based on future goals and concern for others;

- Making decisions with a broad perspective and compassion for oneself and others;

- Managing frustration and distress effectively;

- Seeking help when stress is unmanageable or the situation is dangerous (Murray & Rosenbalm, 2017).

To ensure that you are supporting adolescents in developing these vital skills, there are three important steps you can take:

- Teaching self-regulation skills through modeling them yourself, providing opportunities to practice these skills, monitoring and reinforcing their progress, and coaching them on how, why, and when to use their skills;

- Providing a warm, safe, and responsive relationship in which adolescents are comfortable with making mistakes;

- Structuring the environment to make adolescents’ self-regulation easier and more manageable. Limit opportunities for risk-taking behavior, provide positive discipline, highlight natural consequences of poor decision-making, and reduce the emotional intensity of conflict situations (Murray & Rosenbalm, 2017).

The Role of Self-Regulation in Education

This leads to an important point: Children reach another significant stage of self-regulation development when they begin attending school—and self-regulation is tested as school gets more challenging.

This is where Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning theory comes into play again. Recall that there are three times when self-regulation can aid the learning process:

- Before the learning task is begun, when the student can consider the task, set goals, and develop a plan to tackle the task;

- During the task, when the student must monitor his own performance and see how well his strategies work;

- After the task, when the student can reflect back on their performance and determine what worked well, what didn’t, and what needs to change.

Zimmerman encourages teachers to do the following three things to help students continue to develop self-regulation:

- Give students a choice in tasks, methods, or study partners as often as you can;

- Give students the opportunity to assess their own work and learn from their mistakes;

- Pay attention to the student’s beliefs about his or her own learning abilities and respond with encouragement and support when necessary (2002).

Strategies, Exercises, and Lesson Plans for Students in the Classroom

If you’re a teacher who is interested in implementing more techniques and strategies for encouraging self-regulation in your classroom, consider the resources and methods outlined below.

McGill Self-Regulation Lesson Plans

This resource from McGill University in Canada includes several helpful lesson plans for building self-regulatory skills in students, including lessons on:

- Cognitive emotion regulation;

- Acceptance ;

- Self-blame;

- Positive refocusing;

- Rumination;

- Refocus of planning;

- Catastrophizing;

- Positive reappraisal;

- Blaming others;

- Putting things into perspective.

College & Career Competency Framework and Lessons

The self-regulation lesson plans from the College & Career Competency Framework detail nine separate lessons you can use to help your students continue to develop their skills. The lessons range in length from about 20 to 40 minutes and can be modified or adapted as needed.

The lessons include:

- Define Self-Regulation;

- Understand Your Ability to Self-Regulate by Taking the Questionnaire;

- Make a Plan;

- Practice Making a Plan;

- Monitor Your Plan;

- Make Changes;

- Find Missing Components;

- Practice Self-Regulation.

Click here to access and purchase the workbook containing the lessons. It includes the information you need to build effective strategies into your curriculum.

Finally, for a treasure trove of lesson plans, activities, and readings you can implement in your classroom, click here .

This resource comes from Scott Carchedi at the School Social Work Network, and includes a student manual and four lesson plans:

- Lesson on emotional regulation: “How Hot or Cold Does Your Emotional ‘Engine’ Run?”;

- Lesson on self-calming methods: “Downshift to a Lower Gear, with Help From Your Body”;

- Lesson on reframing feelings before acting on them: “Slow Down and Look Around You”;

- Lesson on conflict resolution: “Find the Best Route to Your Destination” (2013).

For each lesson, you can access a lesson plan and student activity (or activities) via a Word document and a student reading via a PDF. Use these lessons to help your students boost their self-regulation skill development and adapt or modify them as needed.

Although much attention is paid to self-regulation in children and adolescents because that’s when those skills are developing, it’s also important to keep self-regulation in mind for adults.

Self-Regulation and Navigating the Workplace

For example, self-regulation is extremely important in the workplace. It’s what keeps you from yelling at your boss when he’s getting on your nerves, slapping a coworker who threw you under the bus, or from engaging in more benign but still socially unacceptable behaviors like falling asleep at your desk or stealing someone’s lunch from the office fridge.

Those with high self-regulation skills are better able to navigate the workplace, which means they are better equipped to obtain and keep jobs and generally outperform their less-regulated peers.

To help you effectively manage your emotions at work (and build them up outside of work as well), try these tips:

- Do breathing exercises (like mindful breathing);

- Eat healthy, drink lots of water, and limit alcohol consumption;

- Use self-hypnosis to reduce your stress level and remain calm;

- Exercise regularly;

- Sleep seven to eight hours a night;

- Make time for fun outside of work;

- Laugh more often;

- Spend time alone;

- Manage your work-life balance (Connelly, 2012).

These tips likely come off as very general, but it’s true that living a generally healthy life is key to reducing your stress and reserving your energy for self-regulation.

For more specific tips on building your self-regulation skills, read on.

33 Skills and Techniques to Improve Self-Regulation

There are many tips you can use to enhance your self-regulation skills. If you want to give it a shot, read through these techniques and pick one that resonates with you—then try it out.

Mindfulness

Cultivating the skill of mindfulness will improve your ability to maintain your moment-to-moment awareness, which in turn helps you delay gratification and manage your emotions.

Research has shown that mindfulness is very effective at boosting one’s conscious control over attention, helping people regulate negative emotions, and improving executive functioning (Cundic, 2018).

Cognitive Reappraisal

This strategy can be described as a conscious effort to change your thought patterns. This is one of the main goals of cognitive-based therapies (e.g., co gnitive- behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy).

To build your cognitive reappraisal skills, you will need to work on changing and reframing your thoughts when you encounter a difficult situation. Adopting a more adaptive perspective to your situation will help you find a silver lining and help you manage emotion regulation and keep negative emotions at bay (Cundic, 2018).

Cognitive self-regulation has also been found to be positively correlated with social functioning. It involves the cognitive abilities we use to integrate different learning processes, which also help us support our personal goals.

8 Ways to Improve Self-Regulation

This list comes from the Mind Tools website but can also be found in this PDF from Course Hero. It outlines eight methods and strategies for building self-regulation:

- Leading and living with integrity: being a good role model, practicing what you preach, creating trusting environments, and living in alignment with your values ;

- Being open to change: challenging yourself to deal with change in a straightforward and positive manner and working to improve your ability to adapt to different situations while staying positive;

- Identifying your triggers: cultivating a sense of self-awareness that will help you learn what your strengths and weaknesses are and what can trigger you into a difficult state of mind;

- Practicing self-discipline: committing to taking initiative and staying persistent in working toward your goals, even when it’s the last thing you feel like doing;

- Reframing negative thoughts: working on your ability to take a step back from your own thoughts and feelings, analyze them, and come up with positive alternative thoughts;

- Keeping calm under pressure: keeping your cool by removing yourself from the situation for the short-term—whether mentally or physically—and using relaxation techniques like deep breathing;

- Considering the consequences: stopping and thinking about the consequences of giving in to “bad” behavior (e.g., what happened in the past, what is likely to happen now, what this behavior could trigger in terms of longer-term consequences);

- Believing in yourself: boosting your self-efficacy by working on your self-confidence , focusing on the experiences in your life when you succeeded and keeping your mistakes in perspective. Choose to believe in your own abilities and surround yourself with positive, supportive people.

Self-Regulation Strategies: Methods for Managing Myself

This table from Jan Johnson at Learning in Action Technologies lists 23 strategies we can use to self-regulate, both as an individual and as someone in a relationship.

The strategies are categorized into two groups: “Positive or Neutral” and “Negative or Neutral.” Check out some examples in each column and think about where your most frequently used self-regulating learning strategies fall on the chart.

For example, in the upper-left quadrant (“Alone Focus, Positive or Neutral”), strategies include:

- Consciously attend to breathing, relaxing;

- Awareness of body sensations;

- Attending to care for my body, nutrition;

- Meditation and prayer;

- Self-expression: art , music , dance, writing , etc.;

- Caring, nurturing self-talk;

- Laughing, telling jokes;

- Positive self-talk (“I can,” “I’m sufficient” messages);

- Go inside with intentional nurturing of self.

Under the “Relationship—Focus on Other, Positive or Neutral” category, strategies include:

- Seeking dialogue and learning;

- Playing with others;

- Sharing humor;

- Moving toward the relationship to learn (mutual inquiry);

- Desire and/or movement toward collaboration;

- Intentionally honoring or celebrating the other/calling attention to the other.

Finally, the strategies under the “Relationship – Focus on Self, Positive or Neutral” category include:

- Acknowledging what I said or did and any truth in it;

- Moving toward the relationship to learn;

- Desiring collaboration;

- Inquiring about impact;

- Intentionally honoring or celebrating me (throw myself a party).

To see the rest of these strategies, click here (Clicking the link will trigger a download of the PDF).

Self-Regulation in the Classroom

This worksheet is a handy tool that teachers can implement in the classroom. It can be used to help students assess their levels of self-regulation and find areas for improvement.

It lists 23 traits and tendencies that the students can say they do “Always,” “Sometimes,” or “Not So Much.” For the full list, you can see the worksheet here , but below are some examples:

- Participate in small and large group activities;

- Complete work on time;

- Remain on task;

- Follow the classroom rules and routines;

- Ask for help at appropriate times;

- Wait for your turn;

- Refrain from speaking out of turn.

Emotion Regulation Skills

This handout can be useful for both adults and older children and teens. It describes some of the main strategies and skills you can implement to keep emotions under control.

The handout covers four main strategies:

- Opposite action: doing the opposite of what you feel like doing;

- Check the facts: looking back over your experiences to learn the facts of what happened, like the event that triggered a reaction, any interpretations or assumptions made, and whether the response matched the intensity of the situation;

- P.L.E.A.S.E.: This acronym stands for “treat physical illness (PL), eat healthy (E), avoid mood-altering drugs (A), sleep well (S), and exercise (E).” All of these behaviors will help you maintain control of your emotions;

- Paying attention to positive events: keeping your focus on the positive aspects of an experience instead of the negative, trying to engage in a positive activity, and keeping yourself open to the good things.

You can download this handout here .

Handouts: Emotional Regulation, Social Sills, and Problem-Solving

This resource includes several worksheets and handouts you can use as a teacher, parent, or therapist with the children in your care.

It includes worksheets and handouts like Wally’s Problem-Solving Steps, which helps children learn how to problem-solve, and Tiny’s Anger Management Steps, which helps kids figure out how to deal with their anger.

It also includes helpful worksheets that teachers can use to enhance their ability to help students develop better self-regulation skills.

Click here to find out more.

17 Exercises To Foster Self-Acceptance and Compassion

Help your clients develop a kinder, more accepting relationship with themselves using these 17 Self-Compassion Exercises [PDF] that promote self-care and self-compassion.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

If you’re still hungry for more information on self-regulation, there are tons of resources available on the subject. Check out the sources listed below.

Self-Regulation Chart

Aside from the worksheets and handouts noted earlier, there are another handy tool to use with kids: the self-regulation chart.

This self-regulation chart is for parents and/or teachers to complete, but it is focused on the child. It lists 30 skills related to emotional regulation and instructs the adult to rate the child’s performance in each area on a four-point scale that ranges from “Almost Always” to “Almost Never.”

All of these skills are important to keep in mind, but the skills specific to self-regulation include:

- Allows others to comfort him/her if upset or agitated;

- Self-regulates when tense or upset;

- Self-regulates when the energy level is high;

- Deals with being teased in acceptable ways;

- Deals with being left out of a group;

- Accepts not being first at a game or activity;

- Accepts losing at a game without becoming upset/angry;

- Says “no” in an acceptable way to things he/she does not want to do;

- Accepts being told “no” without becoming upset/angry;

- Able to say “I don’t know”;

- Able to end conversations appropriately.

You can find the self-regulation chart and checklist at this link .

The Zones of Self-Regulation

If you spend some time poking exploring self-regulation literature or talking to others about the topic, you’re bound to run into mentions of The Zones of Regulation .

According to developer Leah Kuypers, The Zones of Regulation is a “systematic, cognitive-behavioral approach used to teach self-regulation by categorizing all the different ways we feel and states of alertness we experience into four concrete colored zones” (Kuypers, n.d.).

This book describes the Zones of Regulation curriculum, including lessons and activities you can use in the classroom, in your therapy office, or at home.

In this book, you will learn about the four zones:

- Red Zone: extremely heightened states of alertness and intense emotions (e.g., rage, anger, devastation, terror);

- Yellow Zone: heightened states of alertness and elevated emotions (e.g., silliness, stress, frustration, “the wiggles”), but with more control than the Red Zone;

- Green Zone: calm states of alertness and regulated emotions (e.g., happy, focused, content, ready to learn);

- Blue Zone: states of low alertness and down feelings (e.g., sad, sick, tired, bored).

In addition, reading the book will teach you how to apply the Zones model to help your children, students, or clients build their emotional regulation skills.

You can learn more about this book here .

Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications

For a more academic look at self-regulation, you might want to give this handbook a try.

This volume from researchers Kathleen D. Vohs and Roy F. Baumeister offers a comprehensive look at the theory of self-regulation, the research behind it, and the ways it can be applied to improve quality of life. It also explains how self-regulation is developed and shaped by experiences, and how it both influences and is influenced by social relationships.

Chapters on self-dysregulation (e.g., addiction, overeating, compulsive spending, ADHD) explore what happens when self-regulation skills are not developed to an adequate level.

If you’re a student, researcher, academic, a helping professional, or an aspiring helping professional, you won’t regret investing your time and energy into reading this book and familiarizing yourself with this important topic.

Click here to see the book on Amazon.

The skills involved in self-regulation are necessary for achieving success in life and reaching our most important goals. These skills can also have a major impact on overall wellbeing.

Self-regulation is truly an important topic for everyone to consider. However, it might be even more important for parents and educators to learn about it, since it is an important skill for children to develop.

What do you think of self-regulation theory? What are your strategies for boosting your own self-regulation? What about your strategies for building it in children?

Let us know in the comments section below. If you want to learn more about a similar topic, try reading this piece on posi tive mindsets .

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free .

- Autism Speaks. (2012). What are the positive strategies for supporting behavior improvement? Autism Speaks, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.autismspeaks.org/sites/default/files/section_5.pdf

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 248-287.

- Baumeister, R. F. (2014). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and inhibition. Neuropsychologia, 65, 313-319. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.012

- Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1, 115-128.

- Bell, A. L. (2016). What is self-regulation and why is it so important? Good Therapy Blog. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/what-is-self-regulation-why-is-it-so-important-0928165

- Brown, J. M., Miller, W. R., & Lawendowski, L. A. (1999). The Self-Regulation Questionnaire. In L. VandeCreek & T. L. Jackson (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book, 17, 281-289. Sarasota, FL, US: Professional Resource Press.

- Canadian Foundation for Trauma Research & Education. (n.d.). What is self regulation therapy? CFTRE Courses and Seminars. Retrieved from https://www.cftre.com/courses-seminars/what-is-self-regulation-therapy/

- Carchedi, S. (2013). Curriculum for teaching emotional self-regulation. School Social Work Net. Retrieved from https://www.schoolsocialwork.net/curriculum-for-teaching-emotional-self-regulation/

- Center on the Developing Child. (n.d.). Executive function & self-regulation. Harvard University. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/executive-function/

- Connelly, M. (2012). Self regulation. Change Management Coach. Retrieved from https://www.change-management-coach.com/self-regulation.html

- Cuncic, A. (2018). How to practice self-regulation. Very Well Mind . Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/how-you-can-practice-self-regulation-4163536

- Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2016). Promoting well-being: The contribution of emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 7 .

- Hagger, M. S., & Orbell, S. (2003). A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychology & Health, 18 , 141-184.

- Kuypers, L. (n.d.). Learn more about the zones. Zones of Regulation . Retrieved from https://www.zonesofregulation.com/learn-more-about-the-zones.html

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is motional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3-31). New York, NY, US: Basic Books.

- Murray, D. W., & Rosenbalm, K. (2017). Promoting self-regulation in adolescents and young adults: A practice brief. OPRE Report #2015-82. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation.

- Razza, R. A., Bergen-Cico, D., & Raymond, K. (2013). Enhancing preschoolers’ self-regulation via mindful yoga. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 372-385.

- Shanker, S. (2016). Self-reg: Self-regulation vs. self-control. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/self-reg/201607/self-reg-self-regulation-vs-self-control

- Skowron, E. A., Holmes, S. E., & Sabatelli, R. M. (2003). Deconstructing differentiation: Self regulation, interdependent relating, and well-being in adulthood. Contemporary Family Therapy, 25, 111-129.

- Smith-Donald, R., Raver, C. C., Hayes, T., & Richardson, B. (2007). Preliminary construct and concurrent validity of the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment (PSRA) for field-based research. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22, 173-187.

- Stosny, S. (2011). Self-regulation. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/anger-in-the-age-entitlement/201110/self-regulation

- Straker, D. (n.d.). Self-regulation theory. Changing Minds Theories. Retrieved from http://changingminds.org/explanations/theories/self_regulation.htm

- https://theinspiredtreehouse.com

- Thrive Place. (2013). What is self regulation and how to help a child to learn self regulation. Day2Day Parenting. Retrieved from http://day2dayparenting.com/help-child-learn-self-regulation/

- Verzeletti, C., Zammuner, V. L., Galli, C., Agnoli, S., & Duregger, C. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychology, 3.

- Wagner, D. D., Altman, M., Boswell, R. G., Kelley, W. K., & Heatherton, T. F. (2013). Self-regulatory depletion enhances neural responses to rewards and impairs top-down control. Psychological Science, 24, 2262-2271.

- Williams, P. (n.d.). Chill skills: Calming my emotional child with ADHD. ADDitude. Retrieved from https://www.additudemag.com/chill-skills-calming-my-emotional-adhd-child/

- Your Therapy Source. (2017). 10 fun games to practice self regulation skills (no equipment needed). Your Therapy Source Blog. Retrieved from https://www.yourtherapysource.com/blog1/2017/05/16/games-practice-self-regulation-skills/

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41 , 64-70.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

excellent articles covers all categories of persons including Adults, children, adolescents and toddlers. even in class students too. best wishes

Wow! Thank you for putting this all together.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Reparenting: Seeking Healing for Your Inner Child

In our work as therapists, we often encounter the undeniable truth: we never truly outgrow our inner child. A youthful part within us persists, sometimes [...]

30 Best Self-Exploration Questions, Journal Prompts, & Tools

Life is constantly in flux – our environment and ‘self’ change continually. Self-exploration helps us make sense of who we are, where we are, and [...]

Inner Child Healing: 35 Practical Tools for Growing Beyond Your Past

Many clients enter therapy because they have relationship patterns that they are tired of repeating (Jackman, 2020). They may arrive at the first session asking, [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Develop and Practice Self-Regulation

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Tony Anderson / Getty Images

How Self-Regulation Develops

Common self-regulation problems.

- Effective Strategies

- How to Practice

Frequently Asked Questions

Self-regulation is the ability to control one's behavior, emotions, and thoughts in the pursuit of long-term goals. More specifically, emotional self-regulation refers to the ability to manage disruptive emotions and impulses—in other words, to think before acting.

Self-regulation also involves the ability to rebound from disappointment and to act in a way consistent with your values. It is one of the five key components of emotional intelligence .

This article discusses how self-regulation develops and the important impact it can have. It also covers some common problems you may face and what you can do to self-regulate more effectively.

Your ability to self-regulate as an adult has roots in your childhood. Learning how to self-regulate is an important skill that children learn both for emotional maturity and, later, for social connections.

In an ideal situation, a toddler who throws tantrums grows into a child who learns how to tolerate uncomfortable feelings without throwing a fit, and later into an adult who is able to control impulses to act based on uncomfortable feelings.

In essence, maturity reflects the ability to face emotional, social, and cognitive threats in the environment with patience and thoughtfulness. If this description reminds you of mindfulness, that's no accident— mindfulness does indeed relate to the ability to self-regulate.

Why Self-Regulation Is Important

Self-regulation involves taking a pause between a feeling and an action—taking the time to think things through, make a plan, wait patiently. Children often struggle with these behaviors, and adults may as well.

It's easy to see how a lack of self-regulation will cause problems in life. A child who yells or hits other children out of frustration will not be popular among peers and may face discipline at school.

An adult with poor self-regulation skills may lack self-confidence and self-esteem and have trouble handling stress and frustration. Often, this might result in anger or anxiety. In more severe cases, it can even lead to being diagnosed with a mental health condition.

Qualities of Self-Regulators

In general, people who are adept at self-regulating tend to be able to:

- Act in accordance with their values

- Calm themselves when upset

- Cheer themselves when feeling down

- Maintain open communication

- Persist through difficult times

- Put forth their best effort

- Remain flexible and adapting to situations

- See the good in others

- Stay clear about their intentions

- Take control of situations when necessary

- View challenges as opportunities

Self-regulation allows you to act in accordance with your deeply held values or social conscience and to express yourself appropriately. If you value academic achievement, it will allow you to study instead of slack off before a test. If you value helping others, it will allow you to help a coworker with a project, even if you are on a tight deadline yourself.

In its most basic form, self-regulation allows us to be more resilient and bounce back from failure while also staying calm under pressure. Researchers have found that self-regulation skills are tied to a range of positive health outcomes. This includes better resilience to stress, increased happiness, and better overall well-being.

Self-regulation can play an important role in relationships, well-being, and overall success in life. People who can manage their emotions and control their behavior are better able to manage stress, deal with conflict, and achieve their goals.

How do problems with self-regulation develop? It could start early, such as an infant being neglected. A child who does not feel safe and secure, or who is unsure whether their needs will be met, may have trouble self-soothing and self-regulating.

Later, a child, teen, or adult may struggle with self-regulation, either because this ability was not developed during childhood, or because of a lack of strategies for managing difficult feelings. When left unchecked, over time this could lead to more serious issues such as mental health disorders and risky behaviors such as substance use .

Effective Skills for Self-Regulation

If self-regulation is so important, why were most of us never taught strategies for using this skill? Most often, parents, teachers, and other adults expect that children will "grow out of" the tantrum phase. While this is true for the most part, all children and adults can benefit from learning concrete strategies for self-regulation.

Mindfulness

According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, founder of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), mindfulness is "the awareness that arises from paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally."

By engaging in skills such as focused breathing and gratitude, mindfulness enables us to put some space between ourselves and our reactions, leading to better focus and feelings of calmness and relaxation.

In a 2019 review of 27 research studies, mindfulness was shown to improve attention, which in turn helped with regulating negative emotions and improving executive function .

Cognitive Reappraisal

Cognitive reappraisal, or cognitive reframing , is another strategy that can be used to improve self-regulation abilities. This strategy involves changing thought patterns. Specifically, cognitive reappraisal involves reinterpreting a situation in order to change the emotional response to it.

For example, imagine a friend did not return your calls or texts for several days. Rather than thinking that this reflected something about yourself, such as "my friend hates me," you might instead think, "my friend must be really busy." Research has shown that using cognitive reappraisal in everyday life is related to experiencing more positive and fewer negative emotions.

In a 2016 study examining the link between self-regulation strategies (i.e., mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal, and emotion suppression) and emotional well-being, researchers found cognitive reappraisal to be associated with daily positive emotions, including feelings of enthusiasm, happiness, satisfaction, and excitement.

Some other useful strategies for self-regulation include acceptance and problem-solving. In contrast, unhelpful strategies that people sometimes use include avoidance, distraction, suppression, and worrying.

You can improve your self-regulation skills by practicing mindfulness and changing how you think about the situation.

How Do You Practice Self-Regulation?

If you or your child needs help with self-regulation, there are strategies you can use to improve skills in this area.

Helping Kids With Self-Regulation

In children, parents can help develop self-regulation through routines (e.g., regular mealtimes and consistent bedtime routines). Routines help children learn what to expect, which makes it easier for them to feel comfortable.

When children act in ways that don't demonstrate self-regulation, ignore their requests. For example, if they interrupt a conversation, don't stop your discussion to attend to their needs. Tell that that they will need to wait.

Self-Regulation Tips for Adults

The first step to practicing self-regulation is to recognize that everyone has a choice in how to react to situations. While you may feel like life has dealt you a bad hand, it's not the hand you are dealt, but how you react to it that matters most.

- Recognize that in every situation you have three options : approach, avoidance , and attack. While it may feel as though your choice of behavior is out of your control, it's not. Your feelings may sway you more toward one path, but you are more than those feelings.

- Become aware of your emotions . Do you feel like running away from a difficult situation? Do you feel like lashing out in anger at someone who has hurt you?

- Monitor your body to get clues about how you are feeling if it is not immediately obvious to you. For example, a rapidly increasing heart rate may be a sign that you are entering a state of rage or even experiencing a panic attack.

Start to restore balance by focusing on your deeply held values, rather than those transient emotions. Look beyond momentary discomfort to the larger picture.

Recognizing your options can help you put your self-regulation skills into practice. Focus on identifying what you are feeling, but remember that feelings are not facts. Giving yourself time to stay calm and deliberate your options can help you make better choices.

A Word From Verywell

Once you've learned this delicate balancing act, you will begin to self-regulate more often, and it will become a way of life for you. Developing self-regulation skills will improve your resilience and ability to face difficult circumstances in life.

However, if you find you are unable to teach yourself to self-regulate, consider consulting a mental health professional . A trained therapist can help you learn and implement strategies and skills specific to your situation. Therapy can also be a great place to practice those skills for use in your everyday life.

You can practice self-regulation staying calm and thinking carefully before you react. Engaging in relaxation tactics like deep breathing or mindfulness can help you keep your cool while deliberately considering the consequences of your actions can help you focus on the potential outcomes.

Emotional intelligence refers to a person's ability to recognize, interpret, and regulate emotions. This ability plays an important part in self-regulation and also contributes to the development and maintenance of healthy relationships.

You can help teach your child self-control by managing your own stress, remaining calm, and modeling effective self-regulation skills. You can also strengthen this ability by helping children recognize their emotions, teaching problem-solving skills, setting limits, and enforcing rules with natural consequences.

Gillebaart M. The 'operational' definition of self-control . Front Psychol . 2018;9:1231. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01231

Tao T, Wang L, Fan C, Gao W. Development of self-control in children aged 3 to 9 years: Perspective from a dual-systems model . Sci Rep . 2015;4(1):7272. doi:10.1038/srep07272

Friese M, Messner C, Schaffner Y. Mindfulness meditation counteracts self-control depletion . Conscious Cogn. 2012;21(2):1016-22. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2012.01.008

Hampson SE, Edmonds GW, Barckley M, Goldberg LR, Dubanoski JP, Hillier TA. A Big Five approach to self-regulation: personality traits and health trajectories in the Hawaii longitudinal study of personality and health . Psychol Health Med . 2016;21(2):152-162. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1061676

Hofmann W, Luhmann M, Fisher RR, Vohs KD, Vaumeister RF. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction . J Person . 2014;82(4):265-277. doi:10.1111/jopy.12050

Spratt EG, Friedenberg SL, Swenson CC, et al. The effects of early neglect on cognitive, language, and behavioral functioning in childhood . Psychology . 2012;3(2):175-182. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.32026

Leyland A, Rowse G, Emerson L-M. Experimental effects of mindfulness inductions on self-regulation: Systematic review and meta-analysis . Emotion . 2019;19(1):108-122. doi:10.1037/emo0000425

Brockman R, Ciarrochi J, Parker P, Kashdan T. Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression . Cogn Behav Ther . 2017;46(2):91-113. doi:10.1080/16506073.2016.1218926

Giles GE, Horner CA, Anderson E, Elliott GM, Brunyé TT. When anger motivates: approach states selectively influence running performance . Front Psychol . 2020;11:1663. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01663

Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (15th Anniversary Ed.) . Delta Trade Paperback/Bantam Dell.

Naragon-Gainey K, McMahon TP, Chacko TP. The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic examination . Psychol Bull . 2017;143(4):384-427. doi:10.1037/bul0000093

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

About The Education Hub

- Course info

- Your courses

- ____________________________

- Using our resources

- Login / Account

The importance of self-regulation for learning

- Curriculum integration

- Health, PE & relationships

- Literacy (primary level)

- Practice: early literacy

- Literacy (secondary level)

- Mathematics

Diverse learners

- Gifted and talented

- Neurodiversity

- Speech and language differences

- Trauma-informed practice

- Executive function

- Movement and learning

- Science of learning

- Self-efficacy

- Self-regulation

- Social connection

- Social-emotional learning

- Principles of assessment

- Assessment for learning

- Measuring progress

- Self-assessment

Instruction and pedagogy

- Classroom management

- Culturally responsive pedagogy

- Co-operative learning

- High-expectation teaching

- Philosophical approaches

- Planning and instructional design

- Questioning

Relationships

- Home-school partnerships

- Student wellbeing NEW

- Transitions

Teacher development

- Instructional coaching

- Professional learning communities

- Teacher inquiry

- Teacher wellbeing

- Instructional leadership

- Strategic leadership

Learning environments

- Flexible spaces

- Neurodiversity in Primary Schools

- Neurodiversity in Secondary Schools

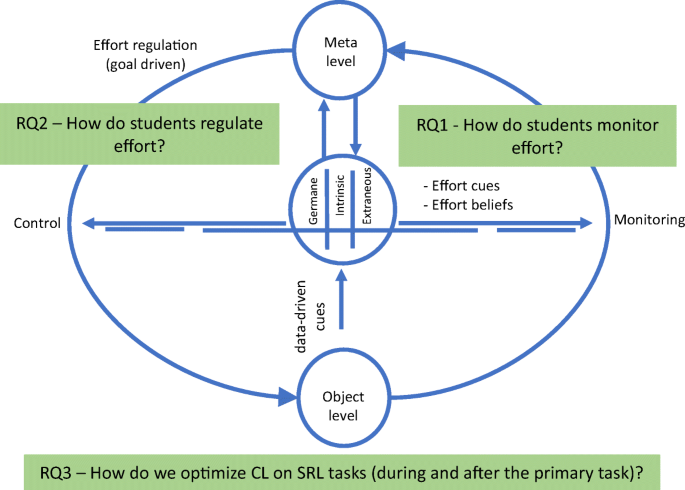

Self-regulation is the process by which students monitor and control their cognition, motivation, and behaviour in order to achieve certain goals. There are several interweaving theories of self-regulation, but most common models conceptualise self-regulation in terms of a series of steps involving forethought or planning, performance, and reflection [i] [ii] . These steps can be explicitly taught and, while self-regulation increases to some extent with age, the research is clear that self-regulation can be improved and that the role of the teacher is crucial in supporting and promoting self-regulated learning. What is more, students’ emotions and their beliefs about their own ability play a key role in the development and exercise of self-regulation, and teachers can further support self-regulation by teaching students about growth mindset and the role of the emotions in learning .

The first step in self-regulated learning is to plan and set goals . Goals are guideposts that students use to check their own progress. Setting goals involves activating prior knowledge about the difficulty of the task and about one’s own ability in that content area. Students may weigh in their mind how long an activity may take and set a time management plan in place. They may also think about particular learning strategies (such as asking themselves questions as they read) that they will use in reaching their goal/s.

Students self-regulate by focusing their energy and attention on the task at hand. This next step involves exercising control. Control can be exercised by implementing any of the learning strategies (such as rehearsal, elaboration, summarising or asking themselves questions) chosen in the first step. Help-seeking can also be a form of control, but only when the learner uses it to develop their own skill or understanding: help-seeking is not considered self-regulatory behaviour when it is used as a crutch to arrive at the answer without the hard work. Control can also take the form of using attention-focusing strategies such as turning off all music, sitting alone, or going to the library, and it involves postponing enjoyable activities in order to make progress towards one’s goals. Simply put, control is general persistence to stick with the strategies that work.