Essay: 1848-1865: Gold Rush, Statehood, and the Western Movement

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 vastly accelerated changes that had been occurring since 1769. Already a meeting place for Mexicans, Russians, Americans, Europeans, and natives, the gold rush turned California into a truly global frontier where immigrants from every continent on earth now jostled. More than 300,000 gold seekers flooded California by 1850, bringing to the new American state an astonishing variety of languages, religions, and social customs. Many of these visitors had no interest in settling down in California, intending only to make their "pile" and return home with pockets full of gold. The arrival and departure of thousands of immigrants, the intensely multicultural nature of society, and the newness of American institutions made Gold Rush California a chaotic, confusing landscape for natives and newcomers alike.

Native Population Plummets

The disruptions of the Gold Rush proved devastating for California's native groups, already in demographic decline due to Spanish and Mexican intrusion. The state's native population plummeted from about 150,000 in 1848 to 30,000 just 12 years later. As foreigners methodically mined, hunted, and logged native groups' most remote hiding places, natives began raiding mining camps for subsistence. This led to cycles of violence as American miners — supported by the state government — organized war parties and sometimes slaughtered entire native groups.

The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, passed by the state legislature in 1850, denied native Californians the right to testify in court and allowed white Americans and Californios to keep natives as indentured servants. "I do not like the white man because he is a liar and a thief," Isidora Filomena de Solano, a Patwin-speaking woman from the Bay Area, told an interviewer in 1874. She echoed the sentiments of many native Californians struggling to preserve traditional ways in the midst of holocaust.

Californios Lose Power, Land, and Privilege

The imposition of American government in California reversed the fortunes of elite Californios, who slowly lost their power, authority, and land. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the US-Mexican War, had granted Californios full US citizenship and promised that their property would be "inviolably respected." But the informality of Mexican land grants made legal claims difficult when miners, squatters, and homesteaders overran Californios' lands.

Even when Californio families won legal title to their lands, many found themselves bankrupt from attorney's fees or taxes. The Peralta family lost all but 700 of their 49,000 acres in the East Bay to lawyers, taxes, squatters, and speculators. Eight Californios participated in the California constitutional convention of 1849, but over time their political power declined along with their land base.

White Americans vs. "Foreign Miners"

Californios feared losing their privileged status and being lumped in with the thousands of Spanish-speaking immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Latin America who arrived in California during the Gold Rush. Mexicans and Chilenos were among the first foreigners to make it to California in 1848, and their proximity and mining expertise gave them an edge in the cutthroat competition of the mines.

Their early success led the California legislature to adopt a foreign miners’ license tax in 1850 aimed at "greasers," as all Latin Americans were called. When Latin American miners refused to pay the impossibly high tax ($20 per month), white Americans had an excuse to drive them out of rich mining areas. In the mining town of Sonora, Mexicans, Chileans, and Peruvians joined with French and German miners to protest the tax, only to be subdued by a hastily formed militia of white Americans.

Rumors began to spread throughout gold country about a swashbuckling Mexican bandit named Joaquín Murieta who was striking back against American injustices. The California legislature offered a huge reward and in 1853 a Texan named Harry Love produced the head of someone he insisted was Murieta. Whether Joaquín Murieta ever actually existed is unknown, but he was celebrated as a hero by many Latin Americans enraged by oppressive American policies.

Chinese Gold Seekers

Chinese gold seekers arrived in great numbers after 1851, and soon comprised about a fifth of the entire population in mining areas. Coming to the mines later than other groups, many Chinese immigrants earned a living by working claims abandoned by other miners. They also took jobs as cooks, launderers, merchants, and herbalists, hoping to return to China with a small fortune. However, low pay, discriminatory hiring practices, and the monthly foreign miners' license tax made this goal all but impossible.

In the face of intense prejudice, some Chinese Californians challenged American racism through the legal system and in the court of public opinion. Chinese community leaders petitioned Sacramento to overturn unfair laws and worked to gain the right to testify in court (finally granted in 1872). Norman Asing, a restaurant owner in San Francisco's booming Chinatown, wrote to California governor John Bigler in 1852, insisting, "We are not the degraded race you would make us."

African Americans Look for Equality and Gold

More than 2,000 African Americans traveled to California by 1852, lured by reports that the California frontier offered a rough-and-tumble egalitarianism along with its gold deposits. Like most gold seekers, they were bitterly disappointed by what they found.

California entered the United States as a free state in 1850, but the lack of government oversight allowed slavery to flourish in certain regions. The state legislature passed a fugitive slave law in 1852, making it illegal for enslaved African Americans to flee their masters within the state's supposedly free borders. All African Americans in California, born free or formerly enslaved, thereafter lived under a constant threat of arrest. They were also barred from testifying in court or sending their children to public schools.

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, an African American abolitionist who had spent years lecturing with Frederick Douglass, helped organize the First State Convention of Colored Citizens of California in 1855 to fight for suffrage and equal rights. African Americans won the right to testify in California in 1863 but the right to vote came only with the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

Cross-Cultural Cooperation

Although discrimination and violence were rampant, Gold Rush California was also a place of cross-cultural communication and cooperation. Canadian merchant William Perkins described the mining town of Sonora in 1849: "Here were to be seen people of every nation in all varieties of costume, and speaking 50 different languages, and yet all mixing together amicably and socially." In mining camps and in the crowded streets of San Francisco, previously isolated groups came into contact for the first time. Race, language, religion, and class separated Californians but proximity forced groups to accommodate as well as compete. Multiracial even before it was a state, California would be continuously shaped by its diversity.

Bancroft Library. The California Gold Rush

Oakland Museum of California. Gold Rush!: California’s Untold Stories

PBS. The Gold Rush

The Sacramento Bee . Gold Rush Sesquicentennial

In the Library

Johnson, Susan Lee. Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Kowalewski, Michael, ed. Gold Rush: A Literary Exploration. Berkeley: Heyday Books, 1997.

Starr, Kevin, and Richard J. Orsi, eds. Rooted in Barbarous Soil: People, Culture, and Community in Gold Rush California. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Related exhibitions

Related themes, about this essay:.

"1848-1865: Gold Rush, Statehood, and the Western Movement" was written by Joshua Paddison and the University of California in 2005 as part of the California Cultures project.

Using this essay:

The text of this essay is available under a Creative Commons CC-BY license . You are free to share and adapt it however you like, provided you provide attribution as follows:

1848-1865: Gold Rush, Statehood, and the Western Movement curated by University of California, available under a ">CC BY 4.0 license . © 2011, Regents of the University of California.

Please note that this license applies only to the descriptive copy and does not apply to any and all digital items that may appear.

The Long Life of the Nacirema

An article that turned an exoticizing anthropological lens on US citizens in 1956 began as an academic in-joke but turned into an indictment of the discipline.

In 1956, the journal American Anthropologist published a short paper by University of Michigan anthropologist Horace Miner titled “ Body Ritual Among the Nacirema ,” detailing the habits of this “North American group.” Among the “exotic customs” it explores are the use of household shrines containing charm-boxes filled with magical potions and visits to a “holy-mouth-man.”

It doesn’t take long for a reader of the paper to recognize the people in question—“Nacirema” is “American” spelled backward. The joke article spread quickly, with other journals publishing excerpts. Writing more than 50 years after its original publication , literature scholar Mark Burde notes that it remained among the most-downloaded anthropology papers.

Yet it was only through chance that the article was published to begin with. Miner initially submitted a version of it to a general-interest publication. In that context, Burde suggests, its satire would have appeared to be directed at the cultural conventions that fill such magazines with ads for breath mints and deodorant soap. He notes lines such as “were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that…their friends [would] desert them.”

When that publication rejected the article, Miner instead submitted it to American Anthropologist. There, the outgoing editor-in-chief initially rejected it, but his successor, Walter Goldschmidt, eventually decided to publish it.

Burde writes that many readers have viewed the paper as a challenge to the basic functioning of anthropology, showing how academic outsiders misunderstand the cultures they claim to chronicle. Some have pointed in particular to the paper’s final paragraph. Here Miner questions how the Nacirema “have managed to exist so long under the burdens which they have imposed upon themselves” and then quotes a 1925 essay by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski: “Looking from far and above, from our high places of safety in the developed civilization, it is easy to see all the crudity and irrelevance of magic. But without its power and guidance early man could not have mastered his practical difficulties as he has done, nor could man have advanced to the higher stages of civilization.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Many readers have suggested that this ending exposed Malinowski’s prejudices and, more generally, the judgment implicit in ethnographers’ identification of cultures as “primitive” or “civilized.” But Burde writes that this was likely not Miner’s intent since he had approvingly cited the same quotation in the past. Instead, he seems to have been more focused on encouraging readers to recognize the way seemingly exotic “far-away” cultures are thoroughly normal to their members.

In general, Burde argues, readers came to see the article as more subversive than Miner had originally intended. That was partly thanks to shifts in scholarship in the 1960s that drew attention to anthropologists as interested parties with their own subject positions and experiences rather than purely objective observers. Burde suggests that part of what has made the Nacirema a durable concept is the way it straddles the line between academic in-joke and radical critique, delivering “a Montaigneseque message in a Woody Allen-esque package.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

Charles Darwin and His Correspondents: A Lifetime of Letters

Who Can Just Stop Oil?

A Brief Guide to Birdwatching in the Age of Dinosaurs

The Alpaca Racket

Recent posts.

- Smells, Sounds, and the WNBA

- A Bodhisattva for Japanese Women

- Asking Scholarly Questions with JSTOR Daily

- Remembering Sun Yat Sen Abroad

- Performing Memory in Refugee Rap

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Mining extracts useful materials from the earth. Although mining provides many valuable minerals, it can also harm people and the environment.

Anthropology, Archaeology, Earth Science, Geology

Open-Pit Copper Mine

Throughout history, minerals, like copper, have been extracted from the earth for human use. It is still mined in places like this open-pit mine outside of Silver City, New Mexico, in the United States.

Photograph by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Mining is the process of extracting useful materials from the earth. Some examples of substances that are mined include coal, gold, or iron ore . Iron ore is the material from which the metal iron is produced.

The process of mining dates back to prehistoric times. Prehistoric people first mined flint, which was ideal for tools and weapons since it breaks into shards with sharp edges. The mining of gold and copper also dates back to prehistoric times.

These profitable substances that are mined from the earth are called minerals . A mineral is typically an inorganic substance that has a specific chemical composition and crystal structure. The minerals are valuable in their pure form, but in the earth they are mixed with other, unwanted rocks and minerals . This mix of rock and minerals is usually carried away from the mine together, then later processed and refined to isolate the desired mineral .

The two major categories of modern mining include surface mining and underground mining. In surface mining, the ground is blasted so that ores near Earth’s surface can be removed and carried to refineries to extract the minerals. Surface mining can be destructive to the surrounding landscape, leaving huge open pits behind. In underground mining, ores are removed from deep within the earth. Miners blast tunnels into the rock to reach the ore deposits. This process can lead to accidents that trap miners underground.

Along with accidents, a career in mining can also be dangerous since it can lead to health problems. Breathing in dust particles produced by mining can lead to lung disease. One of the most common forms is black lung disease, which is caused when coal miners breathe in coal dust. Many other types of mining produce silica dust, which causes a disease similar to black lung disease. These are incurable diseases that cause breathing impairment and can be fatal.

The mining process can also harm the environment in other ways. Mining creates a type of water pollution known as acid mine drainage . First, mining exposes sulfides in the soil. When the rainwater or streams dissolves the sulfides, they form acids . This acidic water damages aquatic plants and animals. Along with acid mine drainage , the disposal of mine waste can also cause severe water pollution from toxic metals. The toxic metals commonly found in mine waste, such as arsenic and mercury, are harmful to the health of people and wildlife if they are released into nearby streams.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Manager

Program specialists, specialist, content production, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Mining and Its Impact on the Environment Essay

Introduction, effects of mining on the environment, copper mining, reference list.

Mining is an economic activity capable of supporting the developmental goals of countries and societies. It also ensures that different metals, petroleum, and coal are available to different consumers or companies. Unfortunately, this practice entails excavation or substantial interference of the natural environment. The negative impacts of mining can be recorded at the global, regional, and local levels. A proper understanding of such implications can make it possible for policymakers and corporations to implement appropriate measures. The purpose of this paper is to describe and discuss the effects of mining on the environment.

Ways Mining Impact on the Environment

Miners use different methods to extract various compounds depending on where they are found. The first common procedure is open cast, whereby people scrap away rocks and other materials on the earth’s surface to expose the targeted products. The second method is underground mining, and it allows workers to get deeper materials and deposits. Both procedures are subdivided further depending on the nature of the targeted minerals and the available resources (Minerals Council of Australia 2019). Despite their striking differences in procedures, the common denominator is that they both tend to have negative impacts on the natural environment.

Firstly, surface mining usually requires that machines and individuals clear forests and vegetation cover. This means that the integrity of the natural land will be obliterated within a short period. Permanent scars will always be left due to this kind of mining. Secondly, the affected land will be exposed to the problem of soil erosion because the topmost soil is loosened. This problem results in flooding, contamination of the following water in rivers, and sedimentation of dams. Thirdly, any form of mining is capable of causing both noise and air pollution (Minerals Council of Australia 2019). The use of heavy machines and blasts explains why this is the case.

Fourthly, other forms of mining result in increased volumes of rocks and soil that are brought to the earth’s surface. Some of them tend to be toxic and capable of polluting water and air. Fifthly, underground mines tend to result in subsidence after collapsing. This means that forests and other materials covering the earth’s surface will be affected. Sixthly, different firms of mining are known to reduce the natural water table. For example, around 500,000,000 cubic meters of water tend to be pumped out of underground mines in Germany annually (Mensah et al., 2015). This is also the same case in other countries across the globe. Seventhly, different mining activities have been observed to produce dangerous greenhouse gases that continue to trigger new problems, including climate change and global warming.

Remediating Mine Sites

The problem of mining by the fact that many people or companies will tend to abandon their sites after the existing minerals are depleted. This malpractice is usually common since it is costly to clean up such areas and minimize their negative impacts on the natural environment. The first strategy for remediating mine sites is that of reclamation. This method entails the removal of both environmental and physical hazards in the region (Motoori, McLellan & Tezuka 2018). This will then be followed by planting diverse plant species. The second approach is the installation of soil cover. When pursuing this method, participants and companies should mimic the original natural setting and consider the drainage patterns. They can also consider the possible or expected land reuse choices.

The third remediation strategy for mine sites entails the use of treatment systems. This method is essential when the identified area is contaminated with metals and acidic materials that pose significant health risks to human beings and aquatic life (Mensah et al., 2015). Those involved can consider the need to construct dams and contain such water. Finally, mining companies can implement powerful cleanup processes and reuse or restore the affected sites. The ultimate objective is to ensure that every ugly site is improved and designed in such a way that it reduces its potential implications on the natural environment. From this analysis, it is evident that the nature of the mining method, the topography of the site, and the anticipated future uses of the region can inform the most appropriate remediation approach. Additionally, the selected method should address the negative impacts on the environment and promote sustainability.

Lessening Impact

Mining is a common practice that continues to meet the demands of the current global economy. With its negative implications, companies and other key stakeholders can identify various initiatives that will minimize every anticipated negative impact. Motoori, McLellan, and Tezuka (2018) encourage mining corporations to diversify their models and consider the importance of recycling existing materials or metals. This approach is sustainable and capable of reducing the dangers of mining. Governments can also formulate and implement powerful policies that compel different companies to engage in desirable practices, minimize pollution, and reduce noise pollution. Such guidelines will make sure that every company remains responsible for remediating their sites. Mensah et al. 2015) also support the introduction of laws that compel organizations to conduct environmental impact assessment analyses before starting their activities. This model will encourage them to identify regions or sites that will have minimal effects on the surrounding population or aquatic life. The concept of green mining has emerged as a powerful technology that is capable of lessening the negative implications of mining. This means that all activities will be sustainable and eventually meet the diverse needs of all stakeholders, including community members. Finally, new laws are essential to compelling companies to shut down and reclaim sites that are no longer in use.

Extraction from the Ore Body

Copper mining is a complex process since it is found in more stable forms, such as oxide and sulfide ores. These elements are obtained after the overburden has been removed. Corporations complete a 3-step process or procedure before obtaining pure copper. This is usually called ore concentration, and it follows these stages: froth flotation, roasting, and leaching (Sikamo, Mwanza & Mweemba 201). During froth flotation, sulfide ores are crushed to form small particles and then mixed with large quantities of water. Ionic collectors are introduced to ensure that CuS becomes hydrophobic in nature. The introduction of frothing agent results in the agitation and aeration of the slurry (Sikamo, Mwanza & Mweemba 2016). This means that the ore containing copper will float to the surface. All tailings will sink to the bottom of the solution. The refined material can then be skimmed and removed.

The next stage is that of roasting, whereby the collected copper is baked. The purpose of this activity is to minimize the quantities of sulfur. Such a procedure results in sulfur dioxide, As, and Sb (Yaras & Arslanoglu 2017). This leaves a fine mixture of copper and other impurities. The next phase of the ore concentration method is that of leaching. Different Compounds are used to solubilize the compound, such as H2SO4 and HCI. The leachate will then be deposited at the bottom and purified.

Smelting is the second stage that experts use to remove copper from its original ore. This approach produces iron and copper sulfides. Exothermic processes are completed to remove SiO2 and FeSiO3 slag (Yaras & Arslanoglu 2017). According to this equation, oxygen is introduced to produce pure copper and sulfur dioxide:

CuO + CuS = Cu(s) + SO2

The final phase is called refinement. The collected Cu is used as anodes and cathodes, whereby they are immersed in H2SO4 and CuSO4. During this process, copper will be deposited on the cathode while the anode will dissolve in the compound. All impurities will settle at the bottom (Sikamo, Mwanza & Mweemba 2016). From this analysis, it is notable that a simple process is considered to collect pure copper from its ore body.

How Copper Mining Impacts the Environment

Copper mining is a complex procedure that requires the completion of several steps if a pure metallic compound is to be obtained. This means that it is capable of presenting complicated impacts on the natural environment. Copper mining can take different forms depending on the location of the identified ores and the policies put in place in the selected country (Yaras & Arslanoglu 2017). Nonetheless, the entire process will have detrimental effects on the surrounding environment. Due to the intensity of operations and involvement of heavy machinery, this process results in land degradation. The affected regions will have huge mine sites that disorient the original integrity of the environment.

Since copper is one of the most valuable metals in the world today due to its key uses, many companies continue to mine it in different countries. This practice has triggered the predicament of deforestation (Sikamo, Mwanza & Mweemba 2016). Additionally, rainwater collects in abandoned mine sites or existing ones, thereby leaking into nearby rivers, boreholes, or aquifers. This means that more people are at risk of being poisoned by this compound.

Air pollution is another common problem that individuals living near copper mines report frequently. This challenge is attributable to the use of heavy blasting materials and machinery. The dust usually contains hazardous chemicals that have negative health impacts on communities and animals. Some of the common ailments observed in most of the affected regions include asthma, silicosis, and tuberculosis (Mensah et al., 2015). This challenge arises from the toxic nature of high levels of copper. These problems explain why companies and stakeholders in the mining industry should implement superior appropriate measures and strategies to overcome them. Such a practice will ensure that they meet the needs of the affected individuals and make it easier for them to pursue their aims.

Copper processing can have significant negative implications on the integrity of the environment. For instance, the procedure is capable of producing tailings and overburden that have the potential to contaminate different surroundings. According to Mensah et al. (2015), some residual copper is left in the environment since around 85 percent of the compound is obtained through the refining process. This means that it will pose health problems to people and aquatic life. Other metals are present in the produced tailings, such as iron and molybdenum. During the separation process, hazardous chemicals and gases will be released, such as sulfur dioxide. This is a hazardous compound that is capable of resulting in acidic rain, thereby increasing the chances of environmental degradation.

There are several examples that explain why copper is capable of causing negative impacts on the natural environment. For example, Queenstown in Tasmania has been recording large volumes of acidic rain (Mensah et al., 2015). This is also the same case for El Teniente Mine in Chile. Recycling and reusing copper can be an evidence-based approach for minimizing these consequences and maintaining the integrity of the environment.

Farmlands that are polluted with this metal compound will have far-reaching impacts on both animals and human beings. This is the case since the absorption of copper in the body can have detrimental health outcomes. This form of poisoning can disorient the normal functions of body organs and put the individual at risk of various conditions. People living in areas that are known to produce copper continue to face these negative impacts (Yaras & Arslanoglu 2017). Such challenges explain why a superior model is needed to overcome this problem and ensure that more people lead high-quality lives and eventually achieve their potential.

The above discussion has identified mining as a major economic activity that supports the performance and integrity of many factories, countries, and companies. However, this practice continues to affect the natural environment and making it incapable of supporting future populations. Mining activities result in deforestation, land obliteration, air pollution, acidic rain, and health hazards. The separation of copper from its parent ore is a procedure that has been observed to result in numerous negative impacts on the environment and human beings. These insights should, therefore, become powerful ideas for encouraging governments and policymakers to implement superior guidelines that will ensure that miners minimize these negativities by remediating sites.

Mensah, AK, Mahiri, IO, Owusu, O, Mireku, OD, Wireko, I & Kissi, EA 2015, ‘Environmental impacts of mining: a study of mining communities in Ghana’, Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 81-94.

Minerals Council of Australia 2019, Australian minerals , Web.

Motoori, R, McLellan, BC & Tezuka, T 2018, ‘Environmental implications of resource security strategies for critical minerals: a case study of copper in Japan’, Minerals, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 558-586.

Sikamo, J, Mwanza, A & Mweemba, C 2016, ‘Copper mining in Zambia – history and future’, The Journal of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, vol. 116, no. 1, pp. 491-496.

Yaras, A & Arslanoglu, H 2017, ‘Leaching behaviour of low-grade copper ore in the presence of organic acid’, Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 319-327.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 22). Mining and Its Impact on the Environment. https://ivypanda.com/essays/mining-and-its-impact-on-the-environment/

"Mining and Its Impact on the Environment." IvyPanda , 22 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/mining-and-its-impact-on-the-environment/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Mining and Its Impact on the Environment'. 22 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Mining and Its Impact on the Environment." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/mining-and-its-impact-on-the-environment/.

1. IvyPanda . "Mining and Its Impact on the Environment." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/mining-and-its-impact-on-the-environment/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Mining and Its Impact on the Environment." February 22, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/mining-and-its-impact-on-the-environment/.

- The Importance of Copper in the 21st Century

- How is Aluminium Ore Converted to Aluminium Metal?

- Copper Mining in Economy, Environment, Society

- Physical and Chemical Properties of Copper

- Water and Energy Problems in Mining Industry

- Gold and Copper Market and Industry Overview

- Iron: Properties, Occurrence, and Uses

- Fortescue Metals Group (FMG) and the Yindjibarndi Aboriginal Land

- Hydrated Copper (II) Sulphate Experiment

- The Ballpoint Pen: Materials, Process and Issues

- Wind Power in West Texas and Its Effects

- National Park Utah: Situation at Arches

- Green Revolution in the Modern World

- Project Oxygen: Making Management Matter

- The Ongoing Problem of Lead in Drinking Water in Newark, New Jersey

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Zócalo Podcasts

Going Back to Blair Mountain

The largest armed labor uprising in american history is finally getting the remembrance it deserves.

In September 1921, as part of the largest armed labor uprising in American history, members of the Red Neck Army surrendered their arms to the U.S. Army. While the battle stayed alive in miners’ families, the stories being “passed down around kitchen tables and on front porches,” it has largely been forgotten in collective memory, writes Kenzie New Walker. Courtesy of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, collection of Kenneth King.

by Kenzie New Walker | September 1, 2022

For most people, the memory of the largest armed labor uprising in American history is unknown, buried beneath the dirt of West Virginia’s Blair Mountain alongside bullet casings and relics of coal camp life. In miners’ families, the stories stayed alive, passed down around kitchen tables and on front porches. But until the 21st century, there were no monuments, museums, or markers of the West Virginia mine wars, a seminal American story of how labor unions came to be.

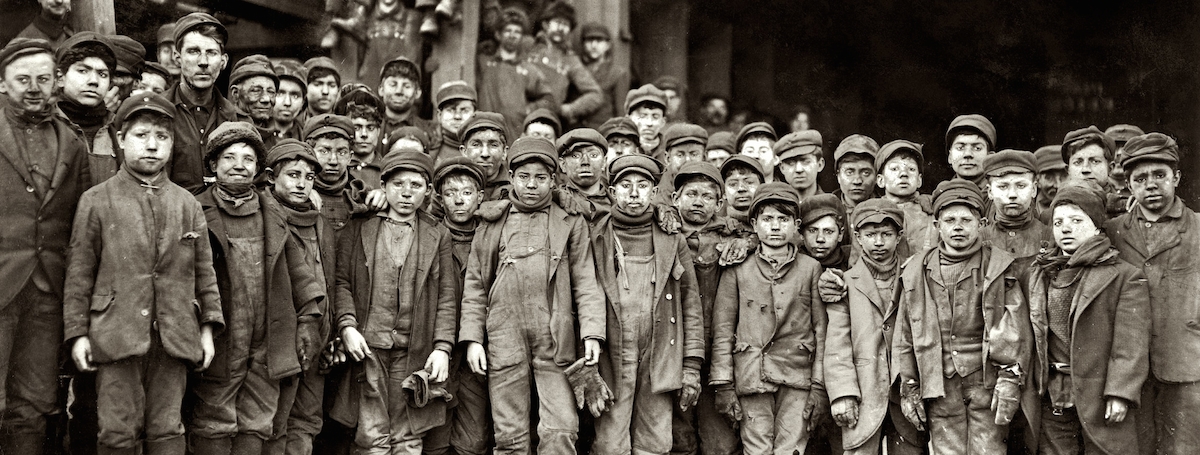

In late August 1921, some 15,000 mineworkers and allies banded together across racial, gender, religious, and ethnic lines and marched south from the town of Marmet, West Virginia. They were determined to free jailed miners who, for decades, had been trying to unionize the southern West Virginia coalfields. Some of the marchers dressed in military uniforms—many were World War I veterans—while others wore blue-jean overalls. All tied red bandanas around their necks to distinguish friend from foe. Known as the “Red Neck Army,” they were highly organized and armed to the teeth.

The miners never reached their intended destination. Instead, beginning on August 31, they clashed with coal company deputies, mine guards, and the state militia over five and half days of combat at Blair Mountain. It was the largest armed uprising since the Civil War—and it ended only when the U.S. Army intervened. While the number of fatalities remains largely unknown (estimates range from 16 to over 100), we do know that it was the second time in American history the government planned to bomb its own citizens—only three months after the first, Oklahoma’s Tulsa Race Massacre.

Those five and a half days were a generation in coming. The majority of West Virginians had gone from living and working on their own land to being totally dependent on out-of-state coal mining companies, who controlled and owned entire towns. The work was unrelenting and exploitative: Coal companies often paid miners in “scrip”—a currency only redeemable at the company store—by the tonnage of coal they hand loaded from the mountains. The conditions underground subjected workers to roof falls and gas explosions, both of which were often catastrophic. For workers and their families, these companies became landlords, employers, and overseers.

In addition to hiring West Virginians displaced from farms, the coal companies recruited immigrants from Europe and African Americans from the South. Companies housed them in tight but segregated communities, aiming to use prejudice and racial barriers to prevent unionization. But their strategies backfired. Unionization efforts, including the Red Neck Army, broke those barriers partly out of necessity and partly as a source of strength. Striking workers moved into desegregated canvas tent colonies after being evicted from their company-owned homes.

By 1921, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), which formed in 1890, had organized much of the coalfields in West Virginia and elsewhere with the promise of better working conditions and a better life. However, in the southern counties of the Mountain State, such as the areas around Blair Mountain, the coal operators and hired mine guards employed harsh countertactics to keep the miners from unionizing, including the murders of union-supporting police chief Sid Hatfield and his deputy Ed Chambers. Hatfield and Chambers’ murders in early August sparked pro-union rallies throughout southern West Virginia, which ultimately led to the Red Neck Army’s armed march.

After the end of the physical battle, a legal battle began that put over 500 miners on trial for a variety of charges, including murder and treason, and crippled the UMWA. Mineworkers in southern West Virginia would have to wait to join until the right to organize was written into federal law as part of the New Deal. In the mid-1930s, they finally gained the better wages, safer working conditions, and other benefits and protections they had been fighting for over decades.

Blair Mountain faded in West Virginians’ and Americans’ collective memory. Politicians strategized to stamp it out of textbooks and public discourse, while miners—many of whom had been on trial—swore themselves to secrecy for fear of retribution.

In 2013, a ragtag group of Appalachians—mineworkers, educators, townspeople, activists, and descendants of Red Neck Army members—came together and shared a table at the UMWA Local 1440 hall in Matewan, West Virginia, 47 miles from Blair Mountain. The folks who gathered were determined to ensure that this history would be celebrated, remembered, and shared for generations to come.

This was the first board meeting of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, which opened two years later in downtown Matewan. I started work at the Mine Wars Museum as its first part-time executive director in 2018. As the daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter of union mineworkers, it is an honor to preserve and share the history and legacy of my ancestors and those who stood with them for labor justice.

One of the exhibits at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum. Courtesy of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, photo by Roger May.

One of the museum’s key initiatives is to bring visibility to the sites of the West Virginia Mine Wars. Today, Blair Mountain’s twin-peaked ridge stands tall and quiet. Despite the mountain’s inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, you can drive through the miners’ marching route and over Blair Mountain without realizing you’re there. But that won’t be the case for much longer.

On the heels of the Battle of Blair Mountain Centennial and with funding from Philadelphia’s Monument Lab, in 2022 we launched Courage in the Hollers: Mapping the Miners’ Struggle for a Union . We’re taking the museum beyond its four walls and holding community meetings along the miners’ 50-mile route to resurface the stories of the Mine Wars and working people—past and present—in public.

This Labor Day, steel silhouettes of 10 men and women, shoulder to shoulder in solidarity, marching toward Blair Mountain, are being erected in Marmet, where the Red Neck Army’s route began, and Clothier, just 12 miles from where the battle raged. The silhouettes are not of the original miners but of local community members—honoring the history that fuels our shared hope for the region and working people across America. As much as it pays homage to the past, it’s a vision for the future.

We held our Courage in the Hollers kickoff meeting in Clothier in a small building that started as a school, then became a church, and is now a union hall. One attendee wondered out loud about Monument Lab’s backing: “Why does someone in Philadelphia care so much about coal miners?”

The simple question struck me. Local residents know this history has been ignored—it is absent from the landscape, their textbooks, public records, and gathering places. But they haven’t forgotten.

Neither have the local archeologists who have spent decades unearthing and preserving artifacts, and the miners’ descendants, more and more of whom are sharing their stories publicly. New accounts of the battle are surfacing for the first time as the monuments and markers to labor make their homes in Clothier and Marmet. Meanwhile, many people are still fighting for the rights and standards the Red Neck Army marched in support of—from miners in Alabama entering their 17th month on strike to unionizing workers at Starbucks and Amazon.

Though the history of those who fought at Blair Mountain is now 101 years old, it is also as alive as ever.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

Get More Zócalo

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

They Just Dig: On Writing, Coal Mining, and Fear

The hard work of excavating trauma.

“Writing is hard for every last one of us—straight white men included. Coal mining is harder. Do you think miners stand around all day talking about how hard it is to mine for coal? They do not. They simply dig.”

–Cheryl Strayed, Dear Sugar #48: “Write Like a Motherfucker”

I come from coal miners: men who lost fingers and arms, the man whose bones were crushed under a rolling coal cart, the one who lived through a leg-cracking explosion, the many whose lungs turned black from decades of dusty inhalations or whose livers buckled under the weight of the after-work rotgut that momentarily knocked out the dread.

I have always known that coal mining is harder than writing.

Most of the men in my family who died in Pennsylvania’s Schuylkill anthracite region have arteriosclerosis on their death certificates—unless they died by suicide or mine accident or, just once, miner’s asthma, 30 yrs.— because until the 1930s the medical establishment denied that the inhalation of coal dust was unhealthy. Doctors insisted it could ward off tuberculosis.

My grandpa worked as a laborer for a bootleg mine when he was young, helping to provide for his family after his miner dad died, but he didn’t make mining a career. He was part of Eisenhower’s flight crew during World War II, then worked for Pan Am as a flight engineer until his retirement. My dad got to choose his career as a fish biologist. I choose to write about my life and teach other writers how to do the same.

I’ve started writing about coal mining. I’ve read thousands of pages about it. I’ve thought about the Dear Sugar quote I’ve seen posted on Facebook so many times that I forgot that it wasn’t an anonymous aphorism. When I found the source and reread the column, Sugar’s powerful advice to a fellow Elissa-writer resonated. I, too, find myself blocked by an ego that demands unattainable greatness. But that’s not the only bulwark I erect between myself and a finished draft.

When I read and write about my family and their work, I think of what Sugar said about coal mining, extract her lines like a chunk of anthracite from a coal face, and project my own meaning onto the words.

I think about how writing is not as hard as coal mining when interviewers and other askers want to know how hard it was for me to write my first book. I’m afraid to say that it was hard, so I usually don’t. If I do say it was hard, I pile on the evidence: in the beginning, I went from smoking casually to smoking more than a pack a day, waking up nicotine-starved and walking-pneumonia-sick. I could only write drunk, stuffed with potato skins. I had panic attacks and hid in the bowels of my closet. I wanted the physical pain of crumpled lungs and weeping liver to outstrip the emotional pain of remembering being raped and defiled.

It was hard work: not just the transmutation of memory into prose, but also the work of reacting to loosened memories I’d hidden from myself. I almost never remembered these things during my writing hours, when I was prepared to be an open seam. I remembered when I was trying to hold it together, in the classroom, riding the bus, watering a cactus and accidentally drowning it when my skull became an echo chamber for that long-forgotten thing the rapist used to say to me when he was trying to convince me that I wanted it.

It was work I keep wanting to call excavation. I keep wanting to say that the memories were buried. I know this is not how remembering works, but I need to label that feeling that I’m digging my hand into my brain and pushing until my fingertips are sliced by tiny jagged rocks.

Anthracite mining was “the most dangerous job of the day,” according to Donald L. Miller and Richard E. Sharpless, authors of The Kingdom of Coal: Work, Enterprise, and Ethnic Communities in the Mine Fields. Mine workers risked being buried under falling coal, sliced by the loosened anthracite’s razor edges, blasted by faulty fuses, poisoned by underground gases, and crushed under heavy coal cars. With every day they escaped sudden death, they neared the inevitable death by smothering that would come from years of inhaled coal dust particles that the body can’t expel. Anthracosis. Miner’s asthma. Black lung.

“They simply dig,” Strayed wrote. But they didn’t. Anthracite miners would routinely strike, defy authority, repeat that “A miner is his own boss,” and walk out when they decided the day’s work was done. And the digging was never simple: every move was a decision that could result in death. The miners took pride in propping the roof with wooden beams, in the drilling of holes, in the preparation of explosives, in the blasting, and in the picking of loosened coal. This was a set of decisions and actions they thought of as craft.

I feel badly about this metaphor I’m trying to build, because I know I shouldn’t liken mining to writing. But I come from resistance to authority, a tradition the men picked up when they began work as boys who picked slate from coal until their fingers bled. I come from people who are proud to do work well and who built an oral tradition around their loathing of this calling.

Proud as they were, mine workers did talk a lot about how hard their work was. They stood around in the shit-and-exhalation-stinking mines and talked about it. They drank rotgut at the saloon and talked about it. They told stories about it. They sang about it. They passed ballads across generations. George Korson writes in Black Rock: Mining Folklore of the Pennsylvania Dutch that on the side of a coal car, one miner chalked the message,

I’ll have you know, Mr. Dunne, That with this car my day is done. If you don’t like my work or poem, You can go to hell, I’m going home!

“Only a Miner,” the folk song that Archie Green calls “the American Miner’s national anthem” in his book Only a Miner: Studies in Recorded Coal-Mining Songs, was passed around from singer to singer from 1888 until its recording in 1928. The song isn’t about coal mining, specifically, but it fits:

He’s only a miner been killed in the ground, Only a miner and one more is found, Killed by an accident, no one can tell, His mining’s all over, poor miner farewell.

Underground anthracite mining was a craft requiring concentration, fearlessness, and the belief that the work was in one’s blood. The miners could only return to work every day because they negotiated their relationships with death by telling stories, which have been passed around with such vigor that we retain them and can see, in their totality, a preoccupation with the dead and injured. The single detail I’ve heard most in stories about my dad’s grandpa Edmund is that he was missing his thumb.

Novelist John Greene drew the mining-writing connection, too, on his website: “I [. . .] like to remind myself of something my dad said to me once in re. writers’ block: ‘Coal miners don’t get coal miners’ block.’”

When I’m blocked, it’s not because I’ve run out of ideas. It’s because I’m afraid of the ones I have on hand.

The mine workers were afraid, too, but not like writers. They dealt with their fears of being trapped underground by propping the roof with beams. From what I can tell, this was a mostly meaningless gesture that was most successful in convincing miners that they had the power to protect themselves from death. They also believed that the rats had extrasensory perceptive abilities that allowed them to predict cave-ins, and so they fed the rats from their lunch pails.

Miners could convince themselves that they were not going to die; I cannot always convince myself that I can make the page stop being blank.

Mostly, for mine workers, the fear of death and accidents was really the fear that loss of income would make their families destitute. Miners could stand around half the day telling stories about men buried alive because the coal face seemed endless, ready to continue giving. They could easily cut enough coal to provide for their families, and the work allowed for the mix of urgency and complacency: they were working for bread, the food that became metaphor in their homes, and they were working to make other men rich.

I should mention these families—more specifically, the wives—and acknowledge that, for the most part, I identify more with the miners than with the women whose occupations were listed on the census as “keeping house,” “none,” or a blank space. All of these entailed harder work than I have ever done: preparing meals, washing clothes (including those caked with coal dust), picking bits of discarded coal from the culm banks to heat the home, washing the man, making and rearing the children (often more than a dozen, including a few who disappear from the census before the end of childhood), gathering vegetables from the gardens and huckleberries from the hills, mending, and waiting for the sound of the whistle announcing that an accident has taken off a man’s arm.

It’s possible that I don’t identify with these women because, in every book I’ve read about mining, they serve to support the tragic-heroic miners. In the 1904 book Anthracite Coal Communities: A Study of the Demography, the Social, Educational and Moral Life of the Anthracite Region, Peter Roberts writes, “As a rule the words of Napoleon are believed and practiced in the houses of the mine workers : ‘A husband ought to have absolute rule over the actions of his wife.’ The lot of the miner’s wife is a hard one.”

A writer, unlike those miners’ wives, is her own boss.

In a 1976 article about a West Virginia mine disaster, Robert Jay Lifton and Eric Olson describe five categories of “manifestations of the general constellation of the survivor”: first, the death imprint , consisting of remembered imagery of the disaster, associated with death; second, death guilt, survivors’ inability to forgive themselves for their survival, coupled with gratitude for having done so, which deepens their guilt; third, psychic numbing, a muting in the ability to feel; fourth, impaired human relationships in which survivors need love but can’t truly accept any proffered love as genuine; and fifth, inner form, the survivor’s work of finding explanations for the devastating experience in order to find meaning in the rest of life.

In the Schuylkill fields, mine accidents were so prevalent that every miner likely had a story. Every miner was imprinted with death. Every retelling helped the miner to make sense of death as an inextricable part of the life he had built.

My fear of the forever-blank page has nothing to do with death or putting bread on the table. I just spent more on eyeglasses than I earned directly from writing in the last six months. I fear incompetence. I fear the ideas running out, the right words never arriving, and the structure never cohering. This is luxury fear. The only thing at stake is the potential for self-satisfaction.

I’ve come to learn something that probably would have become obvious earlier if I weren’t embedded with a generations-old self-immolation streak: writing is only dangerous if I make it so. I no longer douse my writer’s block with whiskey and smoke. I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. When I get stuck, I take a break to put my vitamins in their compartmentalized container or lift weights at the gym.

I suspect the writing-mining connection hits me hard because of the fatalism and predilection for deeply-felt decay passed down from my coalcrackers, but why do other writers respond to it?

Maybe it’s because we think of mining as all brawn and no brain, all danger and no art, all stakes and no reward: just a brute action of the body meant to affect a result with no attachment to quality. But I see more: a sturdy belief that mining is in the blood, a striving so ingrained that a family will send its boys to the breaker even as the father’s black-ink cough sets in. I see work that is the foundation of identity.

Several years ago, in a professional development program for writers, our teacher asked the group how many hours per week we were writing and how many hours per week we wanted to be writing. Everyone reported that they were writing considerably fewer hours than they wanted to be—except for me. I said I didn’t know how much I was writing and I didn’t care. That was a lie. I cared a lot, but I wanted to fake away my frustration. I flagellated myself every day for what I saw as my inability to write. Years later, I’d see the publication of my second book less than a year after my debut, and I’ve spent the ensuing seven months panicked about my inability to follow up with a quick third.

They simply dig. I draft and discard book outlines. I spend an hour on ten words. I ride the intoxication of an early draft and the hangover of the devastating first look back at what I produced. I’ve always feared that I’m not up to the task of executing my grand literary plans, and I’ve repeatedly proven myself wrong. What does not come to mind when I sit down at my desk, but still surely blocks me, is the newer knowledge of what my writing does to my life among the other humans. I resist the label of “brave” because I can’t help but see my act of self-exposure, now, as naïve. I blame myself for failing to expect that a man would use my first book as a perfectly-tailored how-to manual for my emotional abuse. I told myself I was at fault when I briefly dated a man who read the book, unprompted, and interrogated me twice a week about what he saw as my irreparable damage.

My brain has begun to impose boundaries, in spite of my plans for production.

Sometimes, when I’m working out, I simply can’t lift the bar over my head for one more rep. My muscles quit. I break. I try again, but my arms refuse. Until the next time I can get to the weight room, I feel unsettled with my failure to complete a task whose end point doesn’t exist. I used to pay for CrossFit trainers that pushed me so hard I coughed up blood, which was the only time I’ve ever felt that I was working hard enough.

If I were to stop saying that my writing is going fine or really great thanks or you know I’m finally back in the swing of things and it feels good and tell the truth, I would say that I continue to be emotionally dependent on an activity that has become embedded in my sense of self while flaying me all the time, even when the writing is going well, because at any moment, that could turn. I keep doing it because pulling the exact words out of my head and embroidering them onto the page in the scheme I’ve envisioned remains the hardest work I’ve ever done, and the products of that work are beautiful to me. And I do it because this compulsive act of creation is the only way I am able to make sense of life after rape, assault, mania, depression, loss of self through overmedication, and self-destruction.

I’m tired of pretending writing isn’t hard because I feel guilty that I’m not doing something that rots me from the inside out like those men who capped every ascent from dark tunnels with a shot and a lager, or several. I can admit, as I sit in a cupcake shop on a sunny Tuesday afternoon, that I have it easier than my great-grandfather Michael, who, after his last afternoon drunk, stumbled home, his hand in nine-year-old Grandpa’s, got into bed, and died there at age fifty-one, either from black lung or a kicked liver. I have my thumbs and my lungs. I am heading for death, but when I get there, my lungs won’t be fighting to empty themselves of soot. Writing is hard work, but not hard like coal mining: it’s hard like milking the venom from a black widow and letting it go on living.

Even as the rapist was still sleeping in my bed, I sat at my laptop in the dark and began to turn my pain into a story that would help me keep living after disaster. The work has always been hard. I always hit blocks I’ll never use black powder to blast through. I stop digging. I start again, swinging my pick into my head and resuming the work of mining every last rock.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Elissa Washuta

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Adam Phillips on Walt Whitman, Self-Discovery, and American Rock n' Roll

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

A Summary and Analysis of George Orwell’s ‘Down the Mine’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Down the Mine’ is an essay by George Orwell (1903-50), originally published as the second chapter of his 1937 book The Road to Wigan Pier but later reprinted as a separate essay. In ‘Down the Mine’, Orwell describes his experience of going down an English coal mine to see the conditions of coal miners in the 1930s.

You can read ‘Down the Mine’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of Orwell’s argument below.

Orwell describes the experience of miners working in a typical coal mine in 1930s England. He describes mine-workers as ‘splendid’ men (they are always men) who are usually small, because the tunnels down the mine are so small that taller men would find it difficult (if not impossible) to work there.

These men are physically fit from their labour, having worked down the mine since they were children in most cases. They have bodies of ‘iron’, like statues (at the end of the essay he refers to their ‘muscles of steel’).

They tend to work in shifts of seven-and-a-half hours, stopping perhaps for a short break to eat something (bread and cold tea, in many cases). Orwell focuses on small details of the miners’ everyday working lives, such as their habit of chewing tobacco, because it staves off thirst.

Orwell pays particular attention to the long journeys along the underground tunnels which miners often have to make: once they have been lowered down into the mine, they often have to walk (bending as they do so, but with their heads kept facing forwards to watch out for beams overhead) for a mile, sometimes three miles, and (in the case of one mine) up to five miles below-ground before they can begin work.

This is their ‘commute’, a journey which Orwell likens to Londoners having to walk from London Bridge to Oxford Circus. (Earlier, Orwell had described the journey down into the mine, in the densely packed cage that transports miners from the surface down to the coal-face, as like going down the lift on the Piccadilly line on the London Underground; though he makes this comparison in order to contrast that relatively short journey with the extreme depths underground that many miners travel, as much as four hundred yards below the Earth’s surface.)

Once Orwell has described the miners’ journey travelling to and from their place of work, he then reports on the ways in which coal is extracted from the earth. ‘Coal lies in thin seams between enormous layers of rock,’ he tells us, ‘so that essentially the process of getting it out is like scooping the central layer from a Neapolitan ice.’ The ‘fillers’ load up the coal, while the shale is used in road-building; everything else is dumped above-ground in ‘dirt-heaps’.

Orwell is frank about just how back-breaking and intensive coal-mining is. Although he figures that he could perform many kinds of manual labour, being a coal-miner would prove completely beyond his strength or stamina:

When I am digging trenches in my garden, if I shift two tons of earth during the afternoon, I feel that I have earned my tea. But earth is tractable stuff compared with coal, and I don’t have to work kneeling down, a thousand feet underground, in suffocating heat and swallowing coal dust with every breath I take; nor do I have to walk a mile bent double before I begin. The miner’s job would be as much beyond my power as it would be to perform on a flying trapeze or to win the Grand National.

Orwell points out that the world inhabited by coal-miners is a different world from the one he and many other people inhabit: it’s one that people who don’t work in mining very rarely heard about (and, in many cases, probably wouldn’t want to hear about).

Yet, as Orwell states, ‘it is the absolutely necessary counterpart of our world above’, because so much of what people do involves the use of coal. But ‘we are not aware of it’. He likens coal, in a biblical reference, to ‘manna’ – the mysterious food that fell from heaven to feed the Israelites during their travels in the wilderness – except it has to be paid for. But its origins are, in some ways, just as mysterious to those who benefit from it.

He concludes ‘Down the Mine’ by observing that, as hard as these conditions are, they used to be even harder. Pregnant women, until relatively recently, were put to work in the mines. Even today, Orwell writes, everyone in society owes their relative comfort to those workers who toil away in those dark, cramped, dirty conditions underground.

‘Down the Mine’ is a classic example of Orwell’s willingness to put himself at some discomfort in order to experience the conditions of other people first-hand. In order to understand working conditions of people in the north-west of England (Wigan is located around 15 miles northwest of Manchester), Orwell went and lived among them, and his journey down the mine showed his commitment to documenting as faithfully as he could the plight of mine-workers in a fairly typical coal-mine.

For much of ‘Down the Mine’, and especially in his closing paragraphs, Orwell is keen to remind his readers – the vast majority of whom would never so much as seen the inside of a mine, let alone worked in one – that the world is governed by coal, and even some mass shake-up of the current world order, such as a war or a revolution, would still necessitate the mining of coal to heat fires, fuel machinery, and do the countless other things it either directly or indirectly contributes to in the course of daily life.

His mention of Adolf Hitler reminds us that, even in 1937, the threat of imminent European conflict was growing, and sure enough, the war effort (once the Second World War broke out a couple of years after Orwell was writing) would be just as reliant on the production of coal as it would be on farming and manufacturing – indeed, it was even more important than these, because much manufacturing would have been impossible without coal.

Orwell wishes to remind his relatively privileged readers of the exhausting and demanding work that miners undertake. He doesn’t pay attention to mining accidents, which is a curious omission, but he does focus on the day-to-day conditions – the dust, the physical strain, and the darkness – with clarity and attention to detail.

It is noteworthy how often, throughout ‘Down the Mine’, Orwell employs the second-person pronoun, writing not ‘I’ but ‘you’ to describe his own experiences as a sojourner among this world rather than a seasoned miner. This colloquial touch succeeds in placing us down there in the mine with Orwell, involving us in his own journeying through this subterranean other-world.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.59(6); 2021 Nov

Mental health in mine workers: a literature review

José matamala pizarro.

1 School of Psychology. Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaiso, Chile

Francisco AGUAYO FUENZALIDA

The mining environment is hazardous for worker’s health. It can affect the mental health, triggering symptoms and diseases, such as anxiety, job stress, depression, sleep disorders, mental fatigue and other. The aim of this study was to describe and analyze the scientific literature about the mental health in mine workers and to summarize the findings. The method used was scoping review. The principal outcomes were the following: evidence in the last 12 years in the topic was focused in four themes 1) Psychological problems & personal factors (38.2%); 2) Psychosocial problems & health related factor (23.6%); 3) Well-being (21.1%) and 4) Physical problems & organization factors (17.1%). Several affections, symptoms, characteristics or disorders were inquired about mine worker’s mental health, such as job strain, unsafety experiences, poor quality of sleep, non-subjective well-being, job unsatisfaction, social-relations conflict, risk of accidents and injuries, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), substance abuse, dangerous working conditions and demanding job organization, and so on. For those factors, Mining could expose to serious mental health problems to a part of their workers. It’s necessary to deepen the elaboration of international policies and carry out more scientific research and suggestions to make programs on the topic.

Introduction

The mining work has been identified as one of the most hazardous environment for the work activity that exist around the world 1 ) . It’s defined as a high load work, featured with risky conditions and organization systems that involve long distances from workers residences, high demand due shift work schedules and job strain related to compliance the business aims. The available literature has detailed that these characteristics can severely affect the worker’s safety and health, causing diseases, disabilities and even death.

Regarding these negative consequences, the literature has highlighted that the mine workers could develop different ailments and health complications, both physical and mental, which are linked with physical risks, such as dust exposure 2 ) , high temperatures 3 ) , high altitude 4 ) , noise and vibrations environment 5 ) , chemical substances and heavy metals 6 ) , injuries and accidents 7 ) ; likewise with the psychosocial risks, such as high job demand 8 ) , psychological distress 9 ) , shift work schedules 10 ) , distance and isolation with respect to the family 11 ) , hostile legal environments, aggressive employers, outsourcing 12 ) .

Owing to the existence of both kind of risks at mining work (physical and psychosocial), the world research in the theme has characterized some typical occupational diseases, for instance respiratory illnesses, such as silicosis, tuberculosis, asthma 13 ) , pulmonary edema and Acute Mountain Sickness 14 ) ; cardiovascular illnesses, such as heart disease 15 ) , high blood pressure 16 ) ; musculoeskeletal disorders 17 ) ; some types of cancer, such as lung cancer 18 ) and prostate cancer 19 ) ; mental disorders, for instance, job stress, anxiety and depression 20 ) , sleep disorders and fatigue. These are serious indicators of the perilous environment where they work, which can develop suffering experiences and downgrade the mine worker’s health.

The above mentioned, not only reduces the health status of workers, also affects the mining organization. In the study conducted by Nakua et al. 21 ) , they found that 265 miners (25.8% of all miners surveyed) reporting injuries during the past year. This resulted in equal to overall incidence rate of 19.67 injuries per 200,000 hours worked and almost 26.9% to 35.8% of the cases presented moderate or severe absence at work, respectively. Additionally, Widanarko et al. 22 ) affirmed that the presence of Low Back Symptoms (LBS) increased the odds of reporting reduced activities (odds ratio, OR: 4.42, 95% CI: 3.18–6.15) and absenteeism (OR: 4.74, 95% CI: 3.32–6.77); estimated around 805 days lost due to LBS in a year reduced the company’s productivity by USD 209,300 and USD 200 million in national annual productivity.

According to Street et al. 23 ) , job stress was associated with an average of 33.6% work impairment and $45,240.70 (SD = 30,655.26) in productivity costs per employee and workers feeling stressed ‘all of the time’ four week before reporting the highest productivity costs (M = $75,337.16; SD = $47,379.12). Other mental health problems, like the fatigue and sleep deprivation can decrease the focus and attention to tasks 24 ) and augment the risks of accidents 25 ) which rise in long working hours, i.e., irregular shift work 26 ) . The accidents in mining can be fatal. As an example, in 2018 the Chilean mining registered one of the highest amount of days lost in average for work accidents (36.9 days lost average) and in 2017 showed a growth in fatalities (9.0 workers dead from 100,000 protected), both quantities in respect to the national statistics 27 ) .

Consequently, it’s important to know how the worker’s health is affected by mining and, hence, correctly manage the associated factors. A good tool on the matter is the summarized literature. In the last decade, some published literature reviewed in the topic centered at lost-time injury 28 ) ; exposure to silica dust and risk of lung cancer 29 ) ; stomach cancer mortality of workers exposed to asbestos 30 ) ; heat and it’s impacts to safety and health 31 ) , the adverse effects of work at altitude and acclimatization process 14 ) ; sexual and reproductive health 32 ) ; other types of cancer, allergies and respiratory diseases 33 ) .

However, the literature related to miner’s mental health has been more constrained and shallower. It highlights two articles as examples. The first one is the report of Basu et al. 34 ) , it emphasizes on the study’s findings that half of the participants reported feeling nervous or stressed “sometimes” and cortisol signs of chronic stress and pointed out the association between stress and adverse outcomes like cardiovascular disease, acute myocardial infarction, inflammation, hypertension, inadequate nutrition and alcohol/drugs consumption. The second one is the study of Bauerle et al. 35 ) focused on fatigue at mining and they described the factors associated, such as FIFO system (fly-in-fly-out) impoverish the quality of rest, lack of sleep affects the cognitive outcomes (i.e. reaction time), longer shift work shortens the leisure time, childcare and household activities.

Despite the results, both literature reviews show limitations. The first one briefly addressed on the matter, and the second one only paid attention to fatigue factors. For that reason, the need for a more general literature review arose. In order to summarize the evidence, to help knowing about the mental health related problems at mining work and to bridge the existing gap in literature review on the theme, this study presents the results of scoping review on mental health in mine workers across the world.

The research question was What evidences have been produced regarding mental health of mine worker across the world? The aim of this study was to describe and analyze the published scientific literature about the mental health in mine workers and to summarize the findings. The method used was scoping review as suggested by Arksey & O’Malley 36 ) . The reason for using that is associated to the three purposes argued by Pham et al. 37 ) because the focus of the present study was 1) to map the body of literature on a topic area (mine worker’s mental health); 2) To include a major range of design and methodologies on studies with no interest in the effectiveness of the interventions (see inclusion criteria); and 3) seek to provide a descriptive overview of the material and findings without critically appraising individual studies or show synthesis at the risk of bias (see Results).

Strategies for identifying relevant studies

It was search only studies published in scientific journal indexed in the following electronic databases: WOS (Web of Science), SCOPUS, SCIELO and BVS ( Biblioteca Virtual de Salud ). These databases contain many articles relative to the aim of this study. Regarding to realism and enough limit of time, the period of years revised were from 2008 to 2019. The quest was undertaken during august 2019.

The keywords used to find the registers were: “Mental health AND miners* mining”; “Mental diseases AND miners* mining”; “Mental disorders AND miners* mining”; “Stress AND miners* mining”; “Depression AND miners* mining”; “Anxiety AND miners* mining”; “Satisfaction AND miners* mining”; “Occupational risk AND miners* mining”; “Occupational diseases AND miners* mining”; “Well-being AND miners* mining”; “Workload AND miners* mining”; “Shift work AND miners* mining”; “Sleep disorders AND miners* mining”; “Suffering AND miners* mining” and “Workplace violence AND miners* miners”. The same keywords were used too, but in Spanish. In total, 2,604 articles were found in English, whereas just 35 in Spanish.

Study selection process

The material located was downloaded and saved in RIS format. Then, it was included in Collaboratron platform (see https://collaboratron.epistelab.com/ ), removed the duplicates and so as to 1,266 abstracts of documents were maintained. Two researchers read the abstracts and decided (yes or no) if the article entered to whole review or was excluded. After that, the selected records were shared in a common folder in Mendeley Desktop v. 1.19.4 to ease the reading and notes. A total of 113 articles were finally completely checked.

Inclusion criteria

The articles incorporated fulfilled this inclusion criteria: primary studies or secondary data analysis; available as full read and written in English or Spanish; documents that utilized quantitative or qualitative methods and other design (i.e. case report) and showed these characteristics of quality: research problem correctly described, aims, description of method, well set forth the procedure with clear/concise results and an adequate discussion of them. At last, the documents that presented these features were excluded: narrative or systematic reviews; essays, short communications; books or chapter of books; proposals or assessments of interventions; wrote in other languages and inaccessible for reading and notes.

Forty articles were included by inclusion criteria and relevance with the aim of this review. Fig. 1 summarized the search and selection procedure. Charting the data (see Table 1 ) was recorded as follows: Authors, year of publication, aim, study location, mining activity, aims, variables assessment, methods/design, instruments, sample. The data about results and conclusions were charting in Table 2 .

Summary of search and selection procedure.

Source: Own elaboration (2020)

Source: own elaboration (2020)