Landmark Cyber Law cases in India

- Post author By ashwin

- Post date March 1, 2021

By:-Muskan Sharma

Introduction

Cyber Law, as the name suggests, deals with statutory provisions that regulate Cyberspace. With the advent of digitalization and AI (Artificial Intelligence), there is a significant rise in Cyber Crimes being registered. Around 44, 546 cases were registered under the Cyber Crime head in 2019 as compared to 27, 248 cases in 2018. Therefore, a spike of 63.5% was observed in Cyber Crimes [1] .

The legislative framework concerning Cyber Law in India comprises the Information Technology Act, 2000 (hereinafter referred to as the “ IT Act ”) and the Rules made thereunder. The IT Act is the parent legislation that provides for various forms of Cyber Crimes, punishments to be inflicted thereby, compliances for intermediaries, and so on.

Learn more about Cyber Laws Courses with Enhelion’s Online Law Course !

However, the IT Act is not exhaustive of the Cyber Law regime that exists in India. There are some judgments that have evolved the Cyber Law regime in India to a great extent. To fully understand the scope of the Cyber Law regime, it is pertinent to refer to the following landmark Cyber Law cases in India:

- Shreya Singhal v. UOI [2]

In the instant case, the validity of Section 66A of the IT Act was challenged before the Supreme Court.

Facts: Two women were arrested under Section 66A of the IT Act after they posted allegedly offensive and objectionable comments on Facebook concerning the complete shutdown of Mumbai after the demise of a political leader. Section 66A of the IT Act provides punishment if any person using a computer resource or communication, such information which is offensive, false, or causes annoyance, inconvenience, danger, insult, hatred, injury, or ill will.

The women, in response to the arrest, filed a petition challenging the constitutionality of Section 66A of the IT Act on the ground that it is violative of the freedom of speech and expression.

Decision: The Supreme Court based its decision on three concepts namely: discussion, advocacy, and incitement. It observed that mere discussion or even advocacy of a cause, no matter how unpopular, is at the heart of the freedom of speech and expression. It was found that Section 66A was capable of restricting all forms of communication and it contained no distinction between mere advocacy or discussion on a particular cause which is offensive to some and incitement by such words leading to a causal connection to public disorder, security, health, and so on.

Learn more about Cyber Laws with Enhelion’s Online Law firm certified Course!

In response to the question of whether Section 66A attempts to protect individuals from defamation, the Court said that Section 66A condemns offensive statements that may be annoying to an individual but not affecting his reputation.

However, the Court also noted that Section 66A of the IT Act is not violative of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution because there existed an intelligible difference between information communicated through the internet and through other forms of speech. Also, the Apex Court did not even address the challenge of procedural unreasonableness because it is unconstitutional on substantive grounds.

- Shamsher Singh Verma v. State of Haryana [3]

In this case, the accused preferred an appeal before the Supreme Court after the High Court rejected the application of the accused to exhibit the Compact Disc filed in defence and to get it proved from the Forensic Science Laboratory.

The Supreme Court held that a Compact Disc is also a document. It further observed that it is not necessary to obtain admission or denial concerning a document under Section 294 (1) of CrPC personally from the accused, the complainant, or the witness.

- Syed Asifuddin and Ors. v. State of Andhra Pradesh and Anr. [4]

Facts: The subscriber purchased a Reliance handset and Reliance mobile services together under the Dhirubhai Ambani Pioneer Scheme. The subscriber was attracted by better tariff plans of other service providers and hence, wanted to shift to other service providers. The petitioners (staff members of TATA Indicom) hacked the Electronic Serial Number (hereinafter referred to as “ESN”). The Mobile Identification Number (MIN) of Reliance handsets were irreversibly integrated with ESN, the reprogramming of ESN made the device would be validated by Petitioner’s service provider and not by Reliance Infocomm.

Questions before the Court: i) Whether a telephone handset is a “Computer” under Section 2(1)(i) of the IT Act?

- ii) Whether manipulation of ESN programmed into a mobile handset amounts to an alteration of source code under Section 65 of the IT Act?

Decision: (i) Section 2(1)(i) of the IT Act provides that a “computer” means any electronic, magnetic, optical, or other high-speed data processing device or system which performs logical, arithmetic, and memory functions by manipulations of electronic, magnetic, or optical impulses, and includes all input, output, processing, storage, computer software or communication facilities which are connected or related to the computer in a computer system or computer network. Hence, a telephone handset is covered under the ambit of “computer” as defined under Section 2(1)(i) of the IT Act.

(ii) Alteration of ESN makes exclusively used handsets usable by other service providers like TATA Indicomm. Therefore, alteration of ESN is an offence under Section 65 of the IT Act because every service provider has to maintain its own SID code and give its customers a specific number to each instrument used to avail the services provided. Therefore, the offence registered against the petitioners cannot be quashed with regard to Section 65 of the IT Act.

- Shankar v. State Rep [5]

Facts: The petitioner approached the Court under Section 482, CrPC to quash the charge sheet filed against him. The petitioner secured unauthorized access to the protected system of the Legal Advisor of Directorate of Vigilance and Anti-Corruption (DVAC) and was charged under Sections 66, 70, and 72 of the IT Act.

Decision: The Court observed that the charge sheet filed against the petitioner cannot be quashed with respect to the law concerning non-granting of sanction of prosecution under Section 72 of the IT Act.

- Christian Louboutin SAS v. Nakul Bajaj & Ors . [6]

Facts: The Complainant, a Luxury shoes manufacturer filed a suit seeking an injunction against an e-commerce portal www.darveys.com for indulging in a Trademark violation with the seller of spurious goods.

The question before the Court was whether the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s mark, logos, and image are protected under Section 79 of the IT Act.

Decision: The Court observed that the defendant is more than an intermediary on the ground that the website has full control over the products being sold via its platform. It first identifies and then promotes third parties to sell their products. The Court further said that active participation by an e-commerce platform would exempt it from the rights provided to intermediaries under Section 79 of the IT Act.

- Avnish Bajaj v. State (NCT) of Delhi [7]

Facts: Avnish Bajaj, the CEO of Bazee.com was arrested under Section 67 of the IT Act for the broadcasting of cyber pornography. Someone else had sold copies of a CD containing pornographic material through the bazee.com website.

Decision: The Court noted that Mr. Bajaj was nowhere involved in the broadcasting of pornographic material. Also, the pornographic material could not be viewed on the Bazee.com website. But Bazee.com receives a commission from the sales and earns revenue for advertisements carried on via its web pages.

The Court further observed that the evidence collected indicates that the offence of cyber pornography cannot be attributed to Bazee.com but to some other person. The Court granted bail to Mr. Bajaj subject to the furnishing of 2 sureties Rs. 1 lakh each. However, the burden lies on the accused that he was merely the service provider and does not provide content.

- State of Tamil Nadu v. Suhas Katti [8]

The instant case is a landmark case in the Cyber Law regime for its efficient handling made the conviction possible within 7 months from the date of filing the FIR.

Facts: The accused was a family friend of the victim and wanted to marry her but she married another man which resulted in a Divorce. After her divorce, the accused persuaded her again and on her reluctance to marrying him, he took the course of harassment through the Internet. The accused opened a false e-mail account in the name of the victim and posted defamatory, obscene, and annoying information about the victim.

A charge-sheet was filed against the accused person under Section 67 of the IT Act and Section 469 and 509 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Decision: The Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, Egmore convicted the accused person under Section 469 and 509 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and Section 67 of the IT Act. The accused was subjected to the Rigorous Imprisonment of 2 years along with a fine of Rs. 500 under Section 469 of the IPC, Simple Imprisonment of 1 year along with a fine of Rs. 500 under Section 509 of the IPC, and Rigorous Imprisonment of 2 years along with a fine of Rs. 4,000 under Section 67 of the IT Act.

- CBI v. Arif Azim (Sony Sambandh case)

A website called www.sony-sambandh.com enabled NRIs to send Sony products to their Indian friends and relatives after online payment for the same.

In May 2002, someone logged into the website under the name of Barbara Campa and ordered a Sony Colour TV set along with a cordless telephone for one Arif Azim in Noida. She paid through her credit card and the said order was delivered to Arif Azim. However, the credit card agency informed the company that it was an unauthorized payment as the real owner denied any such purchase.

A complaint was therefore lodged with CBI and further, a case under Sections 418, 419, and 420 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 was registered. The investigations concluded that Arif Azim while working at a call center in Noida, got access to the credit card details of Barbara Campa which he misused.

The Court convicted Arif Azim but being a young boy and a first-time convict, the Court’s approach was lenient towards him. The Court released the convicted person on probation for 1 year. This was one among the landmark cases of Cyber Law because it displayed that the Indian Penal Code, 1860 can be an effective legislation to rely on when the IT Act is not exhaustive.

- Pune Citibank Mphasis Call Center Fraud

Facts: In 2005, US $ 3,50,000 were dishonestly transferred from the Citibank accounts of four US customers through the internet to few bogus accounts. The employees gained the confidence of the customer and obtained their PINs under the impression that they would be a helping hand to those customers to deal with difficult situations. They were not decoding encrypted software or breathing through firewalls, instead, they identified loopholes in the MphasiS system.

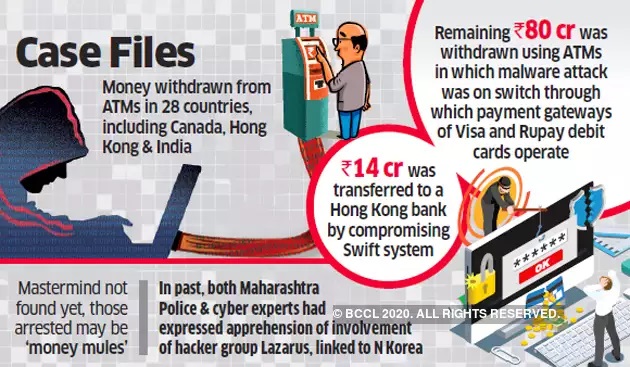

Decision: The Court observed that the accused in this case are the ex-employees of the MphasiS call center. The employees there are checked whenever they enter or exit. Therefore, it is clear that the employees must have memorized the numbers. The service that was used to transfer the funds was SWIFT i.e. society for worldwide interbank financial telecommunication. The crime was committed using unauthorized access to the electronic accounts of the customers. Therefore this case falls within the domain of ‘cyber crimes”. The IT Act is broad enough to accommodate these aspects of crimes and any offense under the IPC with the use of electronic documents can be put at the same level as the crimes with written documents.

The court held that section 43(a) of the IT Act, 2000 is applicable because of the presence of the nature of unauthorized access that is involved to commit transactions. The accused were also charged under section 66 of the IT Act, 2000 and section 420 i.e. cheating, 465,467 and 471 of The Indian Penal Code, 1860.

- SMC Pneumatics (India) Pvt. Ltd. vs. Jogesh Kwatra [9]

Facts: In this case, Defendant Jogesh Kwatra was an employee of the plaintiff’s company. He started sending derogatory, defamatory, vulgar, abusive, and filthy emails to his employers and to different subsidiaries of the said company all over the world to defame the company and its Managing Director Mr. R K Malhotra. In the investigations, it was found that the email originated from a Cyber Cafe in New Delhi. The Cybercafé attendant identified the defendant during the enquiry. On 11 May 2011, Defendant was terminated of the services by the plaintiff.

Decision: The plaintiffs are not entitled to relief of perpetual injunction as prayed because the court did not qualify as certified evidence under section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act. Due to the absence of direct evidence that it was the defendant who was sending these emails, the court was not in a position to accept even the strongest evidence. The court also restrained the defendant from publishing, transmitting any information in the Cyberspace which is derogatory or abusive of the plaintiffs.

The Cyber Law regime is governed by the IT Act and the Rules made thereunder. Also, one may take recourse to the provisions of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 when the IT Act is unable to provide for any specific type of offence or if it does not contain exhaustive provisions with respect to an offence.

However, the Cyber Law regime is still not competent enough to deal with all sorts of Cyber Crimes that exist at this moment. With the country moving towards the ‘Digital India’ movement, the Cyber Crimes are evolving constantly and new kinds of Cyber Crimes enter the Cyber Law regime each day. The Cyber Law regime in India is weaker than what exists in other nations.

Hence, the Cyber Law regime in India needs extensive reforms to deal with the huge spike of Cyber Crimes each year.

[1] “Crime in India – 2019” Snapshots (States/UTs), NCRB, available at: https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/CII%202019%20SNAPSHOTS%20STATES.pdf (Last visited on 25 th Feb; 2021)

[2] (2013) 12 SCC 73

[3] 2015 SCC OnLine SC 1242

[4] 2005 CriLJ 4314

[5] Crl. O.P. No. 6628 of 2010

[6] (2018) 253 DLT 728

[7] (2008) 150 DLT 769

[8] CC No. 4680 of 2004

[9] CM APPL. No. 33474 of 2016

- Tags artificial intelligence courses online , aviation law courses india , best online law courses , business law course , civil courts , civil law law courses online , civil system in india , competition law , corporate law courses online , covaxin , covid vaccine , diploma courses , diploma in criminal law , drafting , fashion law online course , how to study law at home , indian law institute online courses , innovation , Intellectual Property , international law courses , international law degree online , international law schools , introduction to law course , invention , knowledge , labour law course distance learning , law , law certificate courses , law certificate programs online , law classes , law classes online , law college courses , law courses in india , law firms , law schools , lawyers , learn at home , legal aid , legal courses , online law courses , online law courses in india , pfizer , pleading , space law courses , sports law , sports law courses , study criminal law online , study later , study law at home , study law by correspondence , study law degree online , study law degree online australia , study law distance education , study law distance learning , study law online , study law online free , study law online uk , study legal studies online , teach law online , technology law courses , trademark

- Artificial Intelligence

- Generative AI

- Business Operations

- IT Leadership

- Application Security

- Business Continuity

- Cloud Security

- Critical Infrastructure

- Identity and Access Management

- Network Security

- Physical Security

- Risk Management

- Security Infrastructure

- Vulnerabilities

- Software Development

- Enterprise Buyer’s Guides

- United States

- United Kingdom

- Newsletters

- Foundry Careers

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Member Preferences

- About AdChoices

- E-commerce Links

- Your California Privacy Rights

Our Network

- Computerworld

- Network World

The biggest data breaches in India

Cso online tracks recent major data breaches in india..

Over 313,000 cybersecurity incidents were reported in 2019 alone, according to the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In), the government agency responsible for tracking and responding to cybersecurity threats.

Here, we take a look at some of the biggest recent cybersecurity attacks and data breaches in India.

Air India data breach highlights third-party risk

Date: May 2021

Impact: personal data of 4.5 million passengers worldwide

Details: A cyberattack on systems at airline data service provider SITA resulted in the leaking of personal data of of passengers of Air India. The leaked data was collected between August 2011 and February 2021, when SITA informed the airline. Passengers didn’t hear about it until March, and had to wait until May to learn full details of what had happened. The cyber-attack on SITA’s passenger service system also affected Singapore Airlines, Lufthansa, Malaysia Airlines and Cathay Pacific.

CAT burglar strikes again: 190,000 applicants’ details leaked to dark web

Date: May 2021

Impact: 190,000 CAT applicants’ personal details

Details: The personally identifiable information (PII) and test results of 190,000 candidates for the 2020 Common Admission Test, used to select applicants to the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), were leaked and put up for sale on a cybercrime forum. Names, dates of birth, email IDs, mobile numbers, address information, candidates’ 10th and 12th grade results, details of their bachelor’s degrees, and their CAT percentile scores were all revealed in the leaked database.

The data came from the CAT examination conducted on 29 November 2020 but according to security intelligence firm CloudSEK, the same thread actor also leaked the 2019 CAT examination database.

Hacker delivers 180 million Domino’s India pizza orders to dark web

Date: April 2021

Impact: 1 million credit card records and 180 million pizza preferences

Details: 180 million Domino’s India pizza orders are up for sale on the dark web, according to Alon Gal, CTO of cyber intelligence firm Hudson Rock.

Gal found someone asking for 10 bitcoin (roughly $535,000 or ₹4 crore) for 13TB of data that they said included 1 million credit card records and details of 180 million Dominos India pizza orders, topped with customers’ names, phone numbers, and email addresses. Gal shared a screenshot showing that the hacker also claimed to have details of the Domino’s India’s 250 employees, including their Outlook mail archives dating back to 2015.

Jubilant FoodWorks, the parent company of Domino’s India, told IANS that it had experienced an information security incident, but denied that its customers’ financial information was compromised, as it does not store credit card details. The company website shows that it uses a third-party payment gateway, PayTM.

Trading platform Upstox resets passwords after breach report

Impact: All Upstox customers had their passwords reset

Details: Indian trading platform Upstox has openly acknowledged a breach of know-your-customer (KYC) data. Gathered by financial services companies to confirm the identity of their customers and prevent fraud or money laundering, KYC data can also be used by hackers to commit identity theft.

On April 11, Upstox told customers it would reset their passwords and take other precautions after it received emails warning that contact data and KYC details held in a third-party data warehouse may have been compromised.

Upstox apologised to customers for the inconvenience, and sought to reassure them it had reported the incident to the relevant authorities, enhanced security and boosted its bug bounty program to encourage ethical hackers to stress-test its systems.

Police exam database with information on 500,000 candidates goes up for sale

Date: February 2021

Impact: 500,000 Indian police personnel

Details: Personally identifiable information of 500,000 Indian police personnel was put up for sale on a database sharing forum. Threat intelligence firm CloudSEK traced the data back to a police exam conducted on 22 December, 2019.

The seller shared a sample of the data dump with the information of 10,000 exam candidates with CloudSEK. The information shared by the company shows that the leaked information contained full names, mobile numbers, email IDs, dates of birth, FIR records and criminal history of the exam candidates.

Further analysis revealed that a majority of the leaked data belonged to candidates from Bihar. The threat-intel firm was also able to confirm the authenticity of the breach by matching mobile numbers with candidates’ names.

This is the second instance of army or police workforce data being leaked online this year. In February, hackers isolated the information of army personnel in Jammu and Kashmir and posted that database on a public website.

COVID-19 test results of Indian patients leaked online

Date: January 2021

Impact: At least 1500 Indian citizens (real-time number estimated to be higher)

Details: COVID-19 lab test results of thousands of Indian patients have been leaked online by government websites.

What’s particularly worrisome is that the leaked data hasn’t been put up for sale in dark web forums, but is publicly accessible owing to Google indexing COVID-19 lab test reports.

First reported by BleepingComputer, the leaked PDF reports that showed up on Google were hosted on government agencies’ websites that typically use *.gov.in and *.nic.in domains. The agencies in question were found to be located in New Delhi.

The leaked information included patients’ full names, dates of birth, testing dates and centers in which the tests were held. Furthermore, the URL structures indicated that the reports were hosted on the same CMS system that government entities typically use for posting publicly accessible documents.

Niamh Muldoon, senior director of trust and security at OneLogin said: “What we are seeing here is a failure to educate and enable employees to make informed decisions on how to design, build, test and access software and platforms that process and store sensitive information such as patient records.”

He added that the government ought to take quick measures to reduce the risk of a similar breach from reoccurring and invest in a comprehensive information security program in partnership with trusted security platform providers.

User data from Juspay for sale on dark web

Impact: 35 million user accounts

Details: Details of close to 35 million customer accounts, including masked card data and card fingerprints, were taken from a server using an unrecycled access key, Juspay revealed in early January. The theft took place last August, it said.

The user data is up for sale on the dark web for around $5000, according to independent cybersecurity researcher Rajshekhar Rajaharia.

BigBasket user data for sale online

Date: October 2020

Impact: 20 million user accounts

Details: User data from online grocery platform BigBasket is for sale in an online cybercrime market, according to Atlanta-based cyber intelligence firm Cyble.

Part of a database containing the personal information of close to 20 million users was available with a price tag of 3 million rupees ($40,000), Cyble said on November 7.

The data comprised names, email IDs, password hashes, PINs, mobile numbers, addresses, dates of birth, locations, and IP addresses. Cyble said it found the data on October 30, and after comparing it with BigBasket users’ information to validate it, reported the apparent breach to BigBasket on November 1.

Unacademy learns lesson about security

Date: May 2020

Impact: 22 million user accounts

Details: Edutech startup Unacademy disclosed a data breach that compromised the accounts of 22 million users. Cybersecurity firm Cyble revealed that usernames, emails addresses and passwords were put up for sale on the dark web.

Founded in 2015, Unacademy is backed by investors including Facebook, Sequoia India and Blume Ventures.

Hackers steal healthcare records of 6.8 million Indian citizens

Date: August 2019

Impact: 68 lakh patient and doctor records

Details: Enterprise security firm FireEye revealed that hackers have stolen information about 68 lakh patients and doctors from a health care website based in India. FireEye said the hack was perpetrated by a Chinese hacker group called Fallensky519.

Furthermore, it was revealed that healthcare records were being sold on the dark web – several being available for under USD 2000.

Local search provider JustDial exposes data of 10 crore users

Date: April 2019

Impact: personal data of 10 crore users released

Details: Local search service JustDial faced a data breach on Wednesday, with data of more than 100 million users made publicly available, including their names, email ids, mobile numbers, gender, date of birth and addresses, an independent security researcher said in a Facebook post.

SBI data breach leaks account details of millions of customers

Date: January 2019

Impact: three million text messages sent to customers divulged

Details: An anonymous security researcher revealed that the country’s largest bank, State Bank of India, left a server unprotected by failing to secure it with a password.

The vulnerability was revealed to originate from ‘SBI Quick’ – a free service that provided customers with their account balance and recent transactions over SMS. Close to three million text messages were sent out to customers.

Related content

Microsoft’s mea culpa moment: how it should face up to the csrb’s critical report, more attacks target recently patched critical flaw in palo alto networks firewalls, how application security can create velocity at enterprise scale, devsecops: still a challenge but more achievable than ever, from our editors straight to your inbox.

An avid observer and chronicler of emerging technologies with a keen eye on AI and cybersecurity. With wide-ranging experience in writing long-tail features, Soumik has written extensively on the automotive, manufacturing and BFSI sectors. In the past, he has anchored CSO Alert - CSO India's cybersecurity bulletin and been a part of several video features and interviews.

More from this author

Air india data breach highlights concerns around third-party risk and supply-chain security, gomeet pant joins abb as vice president and global head of infosec services, personal information and exam results of 1.9 lakh cat aspirants leaked on dark web, most popular authors.

Show me more

Don’t be afraid of genai code, but don’t trust it until you test it.

MITRE Corporation targeted by nation-state threat actors

6 security items that should be in every AI acceptable use policy

CSO Executive Sessions: Geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea - why the private sector should care

CSO Executive Sessions: 2024 International Women's Day special

CSO Executive Sessions: Former convicted hacker Hieu Minh Ngo on blindspots in data protection

LockBit feud with law enforcement feels like a TV drama

Sponsored Links

- Tomorrow’s cybersecurity success starts with next-level innovation today. Join the discussion now to sharpen your focus on risk and resilience.

- THE WEEK TV

- ENTERTAINMENT

- WEB STORIES

- JOBS & CAREER

- Home Home -->

- The Week The Week -->

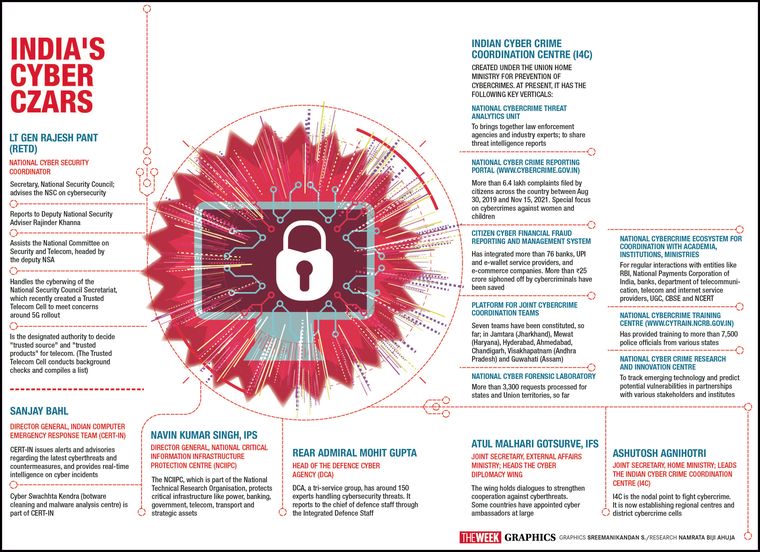

Inside story of cyber attacks on India’s banks, airlines, railways… and the fightback

On March 2, 2014, Ukraine woke up to a major communication blackout. Mobile phones in the former Soviet republic stopped working, the internet and power grid were down. There was panic all around. As authorities tried to figure out what was happening, Russian forces invaded the country and took over the Crimean Peninsula and the key naval base of Sevastopol. The Russian cyberattack before the actual invasion was quite debilitating, and it offered a glimpse of future military tactics. Armies are now more likely to march in only after crippling the enemy’s communication, banking, power supply and transport systems through cyberattacks.

In fact, this was nearly tried out back in 2003 by the US before it invaded Iraq. It had plans to cripple the Iraqi banking system so that Saddam Hussein would have no money to fight back. But the Pentagon decided against it at the last moment, after the CIA warned that such an attack would also cripple the European banking system which was linked to Iraq’s.

Such attacks are not, however, limited to wars and conflicts. They have become quite common, and India is one of the major victims. More than 11.5 lakh incidents of cyberattacks were tracked and reported to India’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) in 2021. According to official estimates, ransomware attacks have increased by 120 per cent in India. Power companies, oil and gas majors, telecom vendors, restaurant chains and even diagnostic labs have been victims of cyberattacks.

On October 12, 2020, Mumbai, the country’s financial capital, was hit by a massive power outage. Train services were cancelled, water supply was affected and hospitals had to rely on generators. Commercial establishments in Mumbai, Thane and Navi Mumbai struggled to keep their operations running until the crisis was resolved two hours later.

Maharashtra Power Minister Nitin Raut alleged sabotage, while cybersecurity experts suspected the hand of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which was engaged in a major standoff with the Indian Army in Ladakh. The needle of suspicion pointed towards 14 Trojan horses, a kind of malware which might have been introduced into the Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Company servers.

The suspicion was not out of place. Maharashtra Cyber, the nodal agency for cybersecurity in the state, has already been warned of attacks on power conglomerates and dispatch centres. It is an open secret that the PLA’s cyber warfare branch and a million malware families hosted by Chinese cyber espionage groups specialise in such attacks. India’s cybersecurity czar Lieutenant General (retd) Rajesh Pant would not take any chances. He called for reports from the state and Central power ministries. “Was there actuation in the grid? What were the indicators of compromise?” Several suspects—most of them Chinese—showed up.

Cyber forensic teams fanned out to investigate and two reports landed on Pant’s table, of which one said the outage was due to an external attack. Experts, however, concluded that although malware was detected, it did not cause the outage. “There are two types of operating systems connecting the power grid,” said an expert. “The malware was detected in the system that was not capable of putting lights out.”

Finally, the national power grid controlled by the Power System Operation Corporation Limited said the failure happened because of human error. Union Power Minister R.K. Singh, too, clarified that there was no link between the outage and the cyberattack.

“If you take a drop of water and analyse it, you will find a million impurities in it. Similarly, a million malwares are detected every day. What is important is to protect our systems against it,” said Brijesh Singh, additional director general of police, who was instrumental in setting up Maharashtra Cyber. All the same, India’s cyber-warriors are constantly on alert, guarding against malware infecting the country’s various infrastructure operating systems such as the railways, power supplies, banking, communication, information dissemination, hospital networks and airlines.

India, on its part, is worried most about its strategic adversary China, given the bad blood between the two countries. The mandate for coordinating India’s activities across multiple sectors to ensure a secure cyberspace has been given to Pant, who is the national cybersecurity coordinator (NCSC) under the National Security Council Secretariat.

Pant advises Prime Minister Narendra Modi on cybersecurity (he is the first Indian general to serve in this position) and assists National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and his team in drawing up strategies to secure cyberspace. Pant and his team gather information on the intent and capabilities of not just principal players like China, but also their foot soldiers like Pakistan.

Insikt Group—the threat research division of the global cyberintelligence firm Recorded Future, which assists the US Cyber Command and 25 CERTs around the world—said intrusions targeting three Indian aerospace and defence contractors, major telecommunication providers in Afghanistan, India, Kazakhstan and Pakistan and multiple government agencies across the region had been detected. At least six state and regional power dispatch centres and two ports were targets, Indian agencies were warned.

Pant and his team, while collating the information from such friendly agencies and from Indian cyberintelligence units, are trying to arm the country and its myriad entities to defend themselves against cyberattacks. Pant, who spent 41 years in the Army Corps of Signals, is a veteran in cyber warfare. Prior to moving to his new position, he was in Mhow, heading the Army’s cyber training establishment. Under his tutelage, India has made rapid strides in hacking, cryptography, reverse engineering and forensics. In 2020, India jumped 37 positions to reach the tenth position on the United Nations Global Cyber Security Index.

While the Mumbai outage was a wakeup call for the Indian cybersecurity establishment, it also showed that some critical sectors were not affected by the power grid failure or the cyber breach. For India’s cyber preparedness, these turned out to be good examples.

One such entity is the Bombay Stock Exchange, the world’s fastest stock exchange that operates at a median trade speed of six microseconds, processing more than three crore transactions a day. Notified as national critical infrastructure by the Central government, the BSE is now coming up with a power exchange, the third in the country after the Indian Energy Exchange and Power Exchange of India Ltd. Shivkumar Pandey, BSE’s group chief information security officer, said the stock exchange had a fully operational 24x7 next generation cybersecurity operation centre (SOC) that protects it from both internal and external threats.

Pandey said the BSE was a perennial target of sophisticated attacks, which it fights with the SOC operating from multiple sites in hybrid mode, utilising more than 40 niche security technologies. “The SOC is also enabled with AI (artificial intelligence) and ML (machine learning) technology to proactively detect and respond to highly sophisticated cyberthreats which traditional technologies may fail to detect and alert on time,” he said. The BSE is working in close coordination with CERT-In to exchange intelligence information and contribute to the overall national information security infrastructure.

CERT-In has stepped up efforts to tackle the growing menace of cyberattacks. Dr Sanjay Bahl, director-general of CERT-In, sensitised board members of multiple organisations in the power and banking sectors on cybersecurity and the latest threat perceptions. The first lesson he imparted was to report the incident itself. The biggest drawback in India’s cyber preparedness is that most organisations—both private and public—are reluctant to report incidents of cyberattack for fear of bad publicity and losing customers.

A few months ago, an airport in a metro city faced a cyberattack where nearly a third of its infrastructure was targeted. Luckily, it got fixed quickly, but Central agencies were kept out of the loop initially. “Had it lasted for more than half an hour, it could have created a bigger problem,” said a government official. The incident made both Central and state agencies sit up and agree that they needed to work in tandem, remove overlaps, fix responsibility and integrate various arms for a coordinated response.

In February 2021, when SITA, the Geneva-based air transport data giant which serves more than 90 per cent of the world’s airlines, informed Air India that hackers stole the personal data of 4.5 million passengers, it presented yet another challenge for India’s cybersecurity establishment. The attack happened outside Indian jurisdiction, yet millions of Indians were affected. “The breach involved personal data spanning almost a decade from August 26, 2011 to February 3, 2021,” Air India said in a statement. While the Indian cyber-warriors tried their best to limit the damage caused by the breach, they soon realised that investigation into attacks which happened outside the Indian cyberspace was not easy because of jurisdictional issues.

Apart from airlines, railways and power, another major area of concern is the telecom sector. “It is the easiest target, as also the one that yields the most value to the attacker,” said a cyber expert. “Telecom carriers give attackers several gateways into multiple businesses.”

Telecom service providers are now required to connect only those new devices which are designated as “trusted products from trusted sources”. An intelligence report warned that a single telecom operator intrusion could give attackers access to a lot more information than they would get by going after individuals.

The government is, therefore, wary about rolling out 5G services. “An entirely new ecosystem has to be created and the country needs to be prepared for it,” said an expert. “5G has 200 times more access points for hackers than the existing networks. In fact, some IoT (Internet of Things) devices can be hacked in 15 minutes.”

India’s cyber-warriors are aware of this threat. The national committee on security and telecom, headed by deputy national security adviser Rajinder Khanna, has issued a directive aimed at creating a secure telecom network system. It has made Pant the designated authority to vet telecommunication sources and products that can enter the country’s telecom network.

Assisting Pant in this task is an army of cyber sleuths from different agencies, handpicked to be part of the ‘trusted telecom cell’. They run background checks of telecom vendors who take part in tenders and screen the ultimate beneficiaries. They examine virtually every chip and semiconductor to see their place of origin and what had gone into their making and design. Their findings are transmitted to nodal officers in Central ministries.

Pant, however, has not taken an alarmist position and blacklisted suspicious foreign entities like the US has been doing. While the US comes out with negative lists of Chinese tech companies like Huawei and ZTE which are barred from working with US firms, Pant is quietly drawing up a “positive” list, from which Indian entities can choose their partners. This also has enabled India to sail through the world of global commerce without ruffling diplomatic feathers.

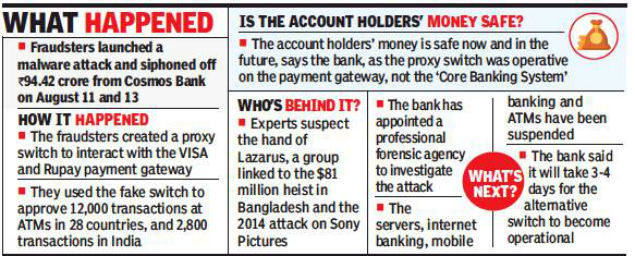

Yet, India has a long way to go to catch up with leading global players in cybersecurity. The malware attack on Cosmos Bank in 2014, in which customers lost 094 crore, was a glaring example of how Indian markets could be easy targets for financial crime syndicates. Brijesh Singh, who handled the case, said he found fraudulent transactions made in 29 countries in two and a half hours. The manner in which the crime was committed showed sophistication and large-scale coordination by international hackers. “What was equally shocking was how online actors used unsuspecting people as money mules to launder money for various criminal operations,” he said.

The Cosmos Bank case has shown that Indian agencies need to step up further in monitoring and preventing money crimes. Sameer Ratolikar, chief information security officer of HDFC Bank, said Indian banks were facing more social engineering attacks like phishing, especially during the pandemic because of the growing number of online transactions.

- Cyber crime: There is not a single institution where the buck stops

- Chinese hackers threaten India's critical infrastructure: CEO, Recorded Future

- We regularly warn of impending threats, says Sanjay Bahl, DG, CERT-In

- India should be seen as safe destination for global IT capability centres: CEO, DSCI

- Cybercriminals will exploit reliance on mobile devices

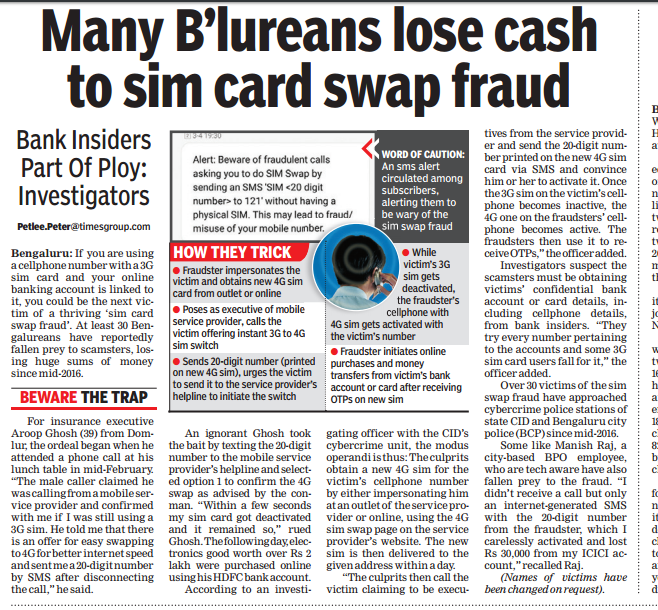

“Fraudsters target gullible customers and lure them with various financial offers, making them disclose their personal information like one-time passwords. This requires a layered defence, including customer awareness,” said Ratolikar. “Other important measures include sending OTPs on a different channel, device binding (the process of linking a token to a trusted device), adaptive authentication (a method for selecting the right authentication factors depending on a user’s risk profile and tendencies) and transaction monitoring solutions.”

The financial sector is also grappling with the problem of ransomware. ‘’Third party vendors are important vectors through which ransomware can be infiltrated,” said Ratolikar. “Therefore, having adequate security framework around them is important.” The best way of defence from ransomware is to create employee awareness, develop a proper incident-response plan and undertake regular tabletop exercises. Ratolikar is working closely with CERT-In, which offers real-time intelligence that helps shut down phishing sites located abroad.

While many of these attempts at hacking banks and airlines might appear the handiwork of non-state enemies and mafias, cybersecurity experts are not willing to dismiss them as private crimes.

Even the US, which boasts top-notch cyber defence capabilities, is not immune to attacks. American intelligence agencies believe that Russian saboteurs had hacked into their voting systems multiple times. The Texas-based cybersecurity firm SolarWinds, which has several high-profile clients like the department of homeland security, the treasury department and at least 100 private companies, too, was a victim. The US imposed sanctions on Russia in April, blaming it for the SolarWinds hack and for the interference in the 2020 elections.

Recorded Future has indicated that geopolitical rivalries and border skirmishes are responsible for most of India’s recent woes in cyberspace. It pointed towards China-sponsored groups APT41 and Barium as having targeted Indian companies multiple times. The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, an independent agency of the US government, endorsed this view in its annual report released in November, taking note of the PLA’s cyberattacks on Indian targets.

The US has documented the attacks and China has issued a denial, but India has got no proof. The good news is that the FBI is chasing some of these groups and probing their links with China’s ministry of state security.

“We are pursuing these criminals no matter where they are and to whom they may be connected,’’ James A. Dawson, FBI’s acting assistant director, told a federal grand jury during a hearing in one of those rare moments when global cyberthreats had real names and faces to them. The jury indicted five Chinese hackers—Zhang Haoran, Tan Dailin, Jiang Lizhi, Qian Chuan and Fu Qiang—for intrusions affecting 100 companies in the US, Australia, Brazil, India, Japan and Hong Kong.

The Chinese foreign ministry called the charges “speculation and fabrication”. The denials have become shriller, especially after the 2015 US-China Cyber Agreement to curb cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property. “Regrettably, the Chinese Communist Party has chosen a different path of making China safe for cybercriminals so long as they attack computers outside China and steal intellectual property outside China,” said Jeffrey A. Rosen, former acting attorney general of the US.

Emerging trends in cybersecurity indicate that nearly all future global conflicts will have a cyber component. Whether it is for spying on governments, targeting defence forces, hitting power and communication grids, crippling transport networks, subverting financial systems or sabotaging flights, the next war will begin in cyberspace. It may even be waged largely there, yet it will wreak havoc in everyday lives of common people, unless a robust defence is put up.

- Cyber warriors

Advertisement

Cybercrime and cybersecurity in India: causes, consequences and implications for the future

- Published: 10 September 2016

- Volume 66 , pages 313–338, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Nir Kshetri 1

2921 Accesses

14 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cybercrime is rising rapidly in India. Developing economies such as India face unique cybercrime risks. This paper examines cybercrime and cybersecurity in India. The literature on which this paper draws is diverse, encompassing the work of economists, criminologists, institutionalists and international relations theorists. We develop a framework that delineates the relationships of formal and informal institutions, various causes of prosperity and poverty and international relations related aspects with cybercrime and cybersecurity and apply it to analyze the cybercrime and cybersecurity situations in India. The findings suggest that developmental, institutional and international relations issues are significant to cybercrime and cybersecurity in developing countries.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the global geography of cybercrime and its driving forces

Shuai Chen, Mengmeng Hao, … Chundong Gao

Cybercrime and Punishment: Security, Information War, and the Future of Runet

The How and Why of Cybercrime: The EU as a Case Study of the Role of Ideas, Interests, and Institutions as Drivers of a Security-Governance Approach

It is important to recognize that, as is the case of any underground economy [ 17 ], estimating the size of a country’s cybercrime industry and its ingredients such as reporting rate is a challenging task. Cybercrime-related studies and surveys are replete with methodological shortcomings, conceptual confusions, logical challenges and statistical problems [ 18 ].

KPMG (2014). Cybercrime survey report 2014 . Retrieve from www.kpmg.com/in .

indolink.com (2012). India battles against cyber crime. Retrieved from http://www.indolink.com/displayArticleS.php?id=102112083833 .

Rid, T. (2012). Think again: cyberwar. Foreign Policy, 192 , 1–11.

Google Scholar

bbc.co.uk (2012). ‘Spam capital’ India arrests six in phishing probe. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-16392960 .

King, R. (2011). Cloud, mobile hacking more popular: Cisco. Retrieved from http://www.zdnet.com/cloud-mobile-hacking-more-popular-cisco-1339328060/ .

Aaron, G., & Rasmussen, R. (2012). Global phishing survey: Trends and domain name use in 2H2011, APWG, Retrieved from http://www.antiphishing.org/reports/APWG_GlobalPhishingSurvey_2H2011.pdf .

Kshetri, N. (2010). The economics of click fraud. IEEE Security and Privacy, 8 (3), 45–53.

Article Google Scholar

Internet Crime Complaint Center (2011). 2010 internet crime report. Retrieved from http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport/2010_ic3report.pdf .

Kshetri, N. (2009). Positive externality, increasing returns and the rise in cybercrimes. Communications of the ACM, 52 (12), 141–144.

cio.de (2014). India’s biometric ID project is back on track. Retrieve from http://www.cio.de/index.cfm?pid=156&pk=2970283&p=1 .

Thomas, T.K. (2012). Govt will help fund buys of foreign firms with high-end cyber security tech . Retrieved from http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/industry-and-economy/info-tech/article3273658.ece?homepage=true&ref=wl_home .

Chockalingam, K. (2003). Criminal victimization in four major cities in southern India. Forum on Crime and Society, 3 (1/2), 117–126.

Holtfreter, K., VanSlyke, S., & Blomberg, T. G. (2005). Sociolegal change in consumer fraud: from victim-offender interactions to global networks. Crime Law and Social Change, 44 , 251–275.

Kumar, J. (2006). Determining jurisdiction in cyberspace. The Social Science Research Network ( SSRN ). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=919261 .

Sharma, V. D. (2002). International crimes and universal jurisdiction. Indian Journal of International Law, 42 (2), l39–l55.

Benson, M. L., Tamara D. M & John E. E. (2009). White-collar crime from an opportunity perspective. In S. S. Simpson & D. Weisburd (Eds.) The criminology of white-collar crime (pp 175–193). Heidelburg: Springer International Publishing.

Naylor, R. T. (2005). The rise and fall of the underground economy. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 11 (2), 131–143.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Kshetri, N. (2013). Reliability, validity, comparability and practical utility of cybercrime-related data, metrics, and information. Information, 4 (1), 117–123.

Hindustan Times (2006). Securing the web .

Aggarwal, V. (2009). Cyber crime’s rampant. Express Computer . Retrieved 27 October, 2009,from http://www.expresscomputeronline.com/20090803/market01.shtml .

Narayan, V. (2010). Cyber criminals hit Esc key for 10 yrs .. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/Cyber-criminals-hit-Esc-key-for-10-yrs/articleshow/6587847.cms .

Hagan, J., & Parker, P. (1985). White-collar crime and punishment: class structure and legal sanctioning of securities violations. American Sociological Review, 50 , 302–316.

Pontell, H. N., Calavita, K., & Tillman, R. (1994). Corporate crime and criminal justice system capacity. Justice Quarterly, 11 , 383–410.

Shapiro, S. (1990). Collaring the crime, not the criminal: reconsidering the concept of white-collar crime. American Sociological Review, 55 , 346–365.

Tillman, R., Calavita, K., & Pontell, H. (1996). Criminalizing white-collar misconduct: determinants of prosecution in savings and loan fraud cases. Crime Law and Social Change, 26 (1), 53–76.

Kshetri, N. (2010). The global cybercrime industry: Economic, institutional and strategic perspectives . New York, Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Kshetri, N. (2010). Diffusion and effects of cybercrime in developing economies. Third World Quarterly, 31 (7), 1057–1079.

UNDP (2006). Country evaluation: Assessment of development results Honduras, New York: United Nations Development Programme Evaluation Office. Retrieved from http://web.undp.org/evaluation/documents/ADR/ADR_Reports/ADR_Honduras.pdf .

Tanaka, V. (2010). The ‘informal sector’ and the political economy of development. Public Choice, 145 (1/20), 295–317. 23 .

Kshetri, N. (2015). India’s cybersecurity landscape: the roles of the private sector and public-private partnership. IEEE Security and Privacy, 13 (3), 16–23.

Bures, O. (2013). Public-private partnerships in the fight against terrorism? Crime Law and Social Change, 60 (4), 429–455.

Salifu, A. (2008). Can corruption and economic crime be controlled in developing economies - and if so, is the cost worth it? Journal of Money Laundering Control, 11 (3), 273–283.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91 (3), 481–510.

Parto, S. (2005). Economic activity and institutions: Taking Stock, Journal of Economic Issues, 39 (1), 21–52.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Political Economy 98 (5), 893–921.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, A. (1954). Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies , XXII (May 1954 ), 139–91.

Chenery, H. B. (1975). The structuralist approach to development policy. The American Economic Review , 65 (2), Papers and Proceedings of the Eighty-seventh Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, 310–316.

Acemoglu, D. (2005). Political economy of development and underdevelopment , Gaston Eyskens Lectures , Leuven, Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Retrieved from http://economics.mit.edu/files/1064 .

Acemoglu, D., Johnson,S., & Robinson.A.J. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run Growth, Handbook of Economic Growth, IA. Edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven N. Durlauf Elsevier B.V., Retrieved from http://baselinescenario.files.wordpress.com/2010/01/institutions-as-a-fundamental-cause.pdf .

de Laiglesia, J. R. (2006). Institutional bottlenecks for agricultural development a stock-taking exercise based on evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa . OECD Development Centre Working Paper No. 248 , Research programme on: Policy Analyses on the Institutional Requirements for Advancing Peace and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa, Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dev/36309029.pdf .

Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: a historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. Journal of Political Economy, 102 , 912–950.

Jones, E. L. (1981). The European miracle: Environments, economies, and geopolitics in the history of Europe and Asia . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Andreas, P. (2011). Illicit globalization: myths, misconceptions, and historical lessons. Political Science Quarterly, 126 (3), 403–425.

Kshetri, N. (2005). Pattern of global cyber war and crime: a conceptual framework. Journal of International Management, 11 (4), 541–562.

Roland, G. (2004). Understanding institutional change: fast-moving and slow-moving institutions. Studies in Comparative International Development, 28 (4), 109–131.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35 , 128–152.

Dahlman, L., & Nelson, R. (1995). Social absorption capability, national innovation systems and economic development. In B. H. Koo & D. H. Perkins (Eds.), Social capability and long-term growth (pp. 82–122). Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Niosi, J. (2008). Technology, development and innovation systems: an introduction. Journal of Development Studies, 44 (5), 613–621.

Kim, S. H., Wang, Q., & Ullrich, J. B. (2012). A comparative study of cyberattacks. Communications of the ACM, 55 (3), 66–73.

Hawser, A. (2011). Hidden threat. Global Finance, 25 (2), 44.

Kirk, J. (2012). Microsoft finds new PCs in China preinstalled with malware . Retrieve from http://www.pcworld.com/article/262308/microsoft_finds_new_computers_in_china_preinstalled_with_malware.html .

Benson, M., Cullen, F., & Maakestad, W. (1990). Local prosecutors and corporate crime. Crime and Delinquency, 36 , 356–372.

Andreas, P., & Price, R. (2001). From war fighting to crime fighting: transforming the American National Security State. International Studies Review, 3 (3), 31–52.

Collins, A. (2003). Security and Southeast Asia: domestic, regional, and global issues. Lynne Rienner Pub

Wenping, H. (2007). The balancing act of China’s Africa policy. China Security , 3 (3), summer, 32–40.

Kshetri, N. (2013). Cybercrime and cybersecurity in the global south . Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kshetri, N. (2013). Cybercrimes in the former Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe: current status and key drivers. Crime Law and Social Change, 60 (1), 39–65.

Kshetri, N., & Dholakia, N. (2009). Professional and trade associations in a nascent and formative sector of a developing economy: a case study of the NASSCOM effect on the Indian offshoring industry. Journal of International Management, 15 (2), 225–239.

Oxley, J. E., & Yeung, B. (2001). E-commerce readiness: institutional environment and international competitiveness. Journal of International Business Studies, 32 (4), 705–723.

Sobel, A. C. (1999). State institutions, private incentives, global capital . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lancaster, J. (2003). In India’s creaky court system, some wait decades for justice; 82- year-old man still fighting charges dating to 1963. The Washington Post 27.

Edelman, L. B., & Suchman, M. C. (1997). The legal environments of organizations. Annual Review of Sociology, 23 , 479–515.

Greenwood, R., & Hinings, C. R. (1996). Understanding radical organizational change: bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Academy of Management Review, 21 (4), 1022–1054.

catindia.gov.in (2014). History, Retrieve September 22, 2014, Retrieve from http://catindia.gov.in/History.aspx . Cyber Appellate Tribunal, Government of India.

Singh, S.R. (2014). India’s only cyber appellate tribunal defunct since 2011 . Retrieve from http://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-s-only-cyber-appellate-tribunal-defunct-since-2011/article1-1235073.aspx .

Duggal, P. (2004). What’s wrong with our cyber laws? Retrieved from http://www.expresscomputeronline.com/20040705/newsanalysis01.shtml .

Anand, J. (2011). Cybercrime up by 700% in Capital. Retrieved from http://www.hindustantimes.com/India-news/NewDelhi/Cyber-crime-up-by-700-in-Capital/Article1-766172.aspx .

Nolen, S. (2012). India’s IT revolution doesn’t touch a government that runs on paper. The Globe and Mail (Canada) , A1.

indiatimes.com (2011b). Most Gurgaon IT, BPO companies victims of cybercrime: survey. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/gurgaon/Most-Gurgaon-IT-BPO-companies-victims-of-cybercrime-Survey/articleshow/10626059.cms .

Rahman, F. (2012). Views: Tinker, tailor, soldier, cyber crook . Retrieved from http://www.livemint.com/2012/04/06111007/Views--Tinker-tailor-soldie.html?h=A1 .

timesofindia.com (2009). Nigerians held for internet fraud, May 28 . Retrieved March 1, 2011 from http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2009-05-28/kolkata/28212706_1_kolkata-police-prize-moneyracket/2 .

indiatimes.com (2011a). Two including Nigerian held for job fraud. Retrieved from http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-02-16/gurgaon/28551786_1_nigerian-gang-job-racket-bank-account .

Saha, T., & Srivastava, A. (2014). Indian women at risk in the cyber space: a conceptual model of reasons of victimization. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 8 (1), 57–67.

timesofindia.indiatimes.com (2013). Government releases national cyber security policy 2013 . Retrieve from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/tech/it-services/Government-releases-National-Cyber-Security-Policy-2013/articleshow/20874965.cms .

Doval, P. (2013). Govt orders security audit of IT infrastructure. Retrieve from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/tech/tech-news/Govt-orders-security-audit-of-IT-infrastructure/articleshow/38398644.cms .

De Mooij, M. K. (1998). Global marketing and advertising: Understanding cultural paradoxes . CA: Sage.

The Economist. (2005). Business: busy signals; Indian call centres. The Economist, 376 (8443), 66.

Mishra, B.R. (2010). Wipro unlikely to take fraud accused to court, business-standard.com. Retrieved March 1, 2011, from http://www.business-standard.com/india/news/wipro-unlikely-to-take-fraud-accused-to-court/386181/ .

Phukan, S. (2002). IT ethics in the Internet age: New dimensions. InSITE . Retrieved October 27,2005, from http://proceedings.informingscience.org/IS2002Proceedings/papers/phuka037iteth.pdf .

Sawant, N. (2009).Virtually speaking, crime in the city on an upward spiral, Times of India. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/news/city/mumbai/Virtually-speaking-crime-in-the-city-on-an-upward-spiral/articleshow/5087668.cms , accessed 27 October 2009.

PRLog (2011). India Plans to set-up state-of-the-art information technology institute to combat cybercrime: India requires 2.5 lakh cyber specialists to deal with the menace of cybercrime . Retrieved from http://www.prlog.org/11302019-india-plans-to-set-up-state-of-the-art-information-technology-institute-to-combat-cybercrime.html .

Saraswathy, M. (2012). Wanted: ethical hackers. Retrieved from http://www.wsiltv.com/news/three-states/Protect-Yourself-from-Cyber-Crime-139126239.html .

ciol.com (2012). Most Indians unaware of security solns: study . Retrieved from http://www.ciol.com/Infrastructure-Security/News-Reports/Most-Indians-unaware-of-security-solns-study/161905/0/ .

foxnews.com (2012). Indian lawmakers filmed ‘watching porn on phone during assembly’ resign . Retrieved from http://www.foxnews.com/world/2012/02/08/indian-lawmakers-filmed-watching-porn-on-phone-during-assembly-resign/ .

The World Bank Group (2014). Researchers in R&D (per million people). Retrieve from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.SCIE.RD.P6?page=2 .

rediff.com (2008). Researchers? Only 156 per million in India. Retrieved from http://www.rediff.com/money/2008/mar/12rnd.htm .

Economictimes (2005). R&D in India: The curtain rises, the play has begun, August 24 . Retrived August 11, 2011 from: http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/rd-in-india-the-curtain-rises-the-play-hasbegun/articleshow/1207024.cms .

Shaftel, D., & Narayan, K. (2012). Call centre fraud opens new frontier in cybercrime. Retrieved September 1, 2016, from http://www.livemint.com/2012/02/26225530/Call-centre-fraud-opens-new-fr.html .

Gardner, T. (2012). Indian call centres selling your credit card details and medical records for just 2p . Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2116649/Indian-centres-selling-YOUR-credit-card-details-medical-records-just-2p.html .

Economist.com (2007). Imitate or die. http://www.economist.com/node/10053234/ .

Robinson, G. E. (1998). Elite cohesion, regime succession and political instability. Syria Middle East Policy, 5 (4), 159–179.

Kshetri, N. (2011). Cloud computing in the global south: drivers, effects and policy measures. Third World Quarterly, 32 (6), 995–1012.

Borland, J . (2010). A Four-Day Dive Into Stuxnet’s Heart, December 27 . Retrieved 1 September 2016 from https://www.wired.com/2010/12/a-four-day-dive-into-stuxnets-heart/ .

Halsey, M. (2011). How is IE6 contributing to China’s growing Cyber-Crimewave? Retrieved from http://www.windows7news.com/2011/12/30/ie6-contributing-chinas-growing-cybercrimewave/ .

Greenberg, A. (2007). The top countries for cybercrime. Forbes.com . Retrieved April 9, 2008, from http://www.forbes.com/2007/07/13/cybercrime-world-regions-tech-cx_ag_0716cybercrime.html .

Arnott, S. (2008). Cyber crime stays one step ahead . Retrieved October 27,2009, from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/cyber-crime-stays-one-step-ahead-799395.html .

Paget, F. (2010). McAfee helps FTC, FBI in case against ‘scareware’ outfit. Retrieved January 26, 2011, from http://blogs.mcafee.com/mcafee-labs/mcafee-helps-ftc-fbi-in-case-against-scareware-outfit .

Fest, G. (2005). Offshoring: feds take fresh look at India BPOs; major theft has raised more than a few eyebrows. Bank Technology News, 18 (9), 1.

Engardio, P., Puliyenthuruthel, J., & Kripalani, M. (2004). Fortress India? Business Week, 3896 , 42–43.

King, A. A., & Lenox, M. J. (2000). Industry self-regulation without sanctions: the chemical industry’s responsible care program. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (4), 698–716.

Vinogradova, E. (2006). Working around the state: contract enforcement in the Russian context. Socio-Economic Review, 4 (3), 447–482.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Walzer, M. (1993). Between nation and world: welcome to some new ideologies. The Economist, 328 (7828), 49–52. September 11 .

Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: the role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Academy of Management Journal, 45 (1), 58–80.

Marshall, R. S., Cordano, M., & Silverman, M. (2005). Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US wine industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 14 (2), 92–109.

Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2001). Learning from successful local private firms in China: establishing legitimacy. Academy of Management Executive, 15 (4), 72–83.

Scott, W.R. (1992). Organizations: Rational, natural and open systems . Prentice Hall.

Trombly, M. (2006). India tightens security. Insurance Networking & Data Management, 10 (1), 9.

Dickson, M., BeShers, R., & Gupta, V. (2004). The impact of societal culture and industry on organizational culture: Theoretical explanations. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: the GLOBE study of 62 societies . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Lawrence, T. B., Winn, M. I., & Jennings, P. D. (2001). The temporal dynamics of institutionalization. Academy of Management Review, 26 (4), 624–644.

Audretsch, D., & Stephan, P. (1996). Company scientist locational links: the case of biotechnology. American Economic Review, 30 , 641–652.

Feldman, M. (1999). The new economics of innovation, spillovers and agglomeration: a review of empirical studies. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 8 , 5–25.

Niosi, J., & Banic, M. (2005). The evolution and performance of biotechnology regional systems of innovation. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29 , 343–357.

Rao, H.S. (2006). Outsourcing thriving in Britain despite India bashing. Retrieve from http://www.rediff.com/money/2006/oct/07bpo.htm .

AFX News (2006). India could process 30 pct of US bank transactions by 2010 - report . Retrieve from http://www.finanznachrichten.de/nachrichten-2006-09/7050839-india-could-process-30-pct-of-us-bank-transactions-by-2010-report-020.htm .

Hazelwood, S. E., Hazelwood, A. C., & Cook, E. D. (2005). Possibilities and pitfalls of outsourcing. Healthcare Financial Management, 59 (10), 44–48.

PubMed Google Scholar

Das, G. (2011). Panel to advise govt, IT cos on cloud security on the cards. Retrieved from http://www.financialexpress.com/news/Panel-to-advise-govt--IT-cos-on-cloud-security-on-the-cards/809960/ .

Schwartz, K. D. (2005). The background-check challenge. InformationWeek , 59–61.

Indo-Asian News Service (2006). Nasscom to set up self-regulatory organization. September 26.

Cone, E. (2005). Is offshore BPO running aground? CIO Insight, 53 , 22.

COMMWEB (2007). India will train police to catch cybercriminals.

DSCI (2014). Cyber Labs. Retrieve from http://www.dsci.in/cyber-labs .

Tribuneindia.com (2005). Outsourcing crime call centre expose can wreak havoc, June 25. Retrieved from http://www.tribuneindia.com/2005/20050625/edit.htm .

Jaishankar, K. (2008). Identity related crime in the cyberspace: examining phishing and its impact. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 2 (1), 10–15.

Segal, A. (2012). Chinese computer games. Foreign Affairs, 91 (2), 14–20. 7 .

dhs.gov (2011). United States and India Sign Cybersecurity Agreement . Retrieved from http://www.dhs.gov/ynews/releases/20110719-us-india-cybersecurity-agreement.shtm .

Bhaumik, A. (2012). India, allies to combat cybercrime . Retrieved from http://www.deccanherald.com/content/249937/india-allies-combat-cybercrime.html .

Riley, M. (2011). Stolen Credit Cards Go for $3.50 at Amazon-Like Online Bazaar . Retrieved on 1 September 2016 from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-12-20/stolen-creditcards-go-for-3-50-each-at-online-bazaar-that-mimics-amazon .

Trend Micro Incorporated (2011). Trend micro third quarter threat report: Google and oracle surpass microsoft in most vulnerabilities. Retrieved from http://www.sacbee.com/2011/11/14/4053420/trend-micro-third-quarter-threat.html .

Vidyasagar, N. (2004). India’s secret army of online ad ‘clickers’ . Retrieved October 27,2008, from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/msid-654822,curpg-1.cms .

Kehaulani, S. (2006). ‘Click Fraud’ threatens foundation of web ads; Google faces another lawsuit by businesses claiming overcharges. The Washington Post , A.1.

Frankel, R. (2006). Associations in China and India: An overview, European Society of Association Executives . Retrieved from http://www.esae.org/articles/2006_07_004.pdf .

Tandon, N. (2007). Secondary victimization of children by the media: an analysis of perceptions of victims and journalists. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 2 (2), 119–135.

Halder, D., & Jaishankar, K. (2011). Cyber gender harassment and secondary victimization: a comparative analysis of US, UK and India. Victims and Offenders, 6 (4), 386–398.

Halder, D., & Jaishankar, K. (2015). Irrational coping theory and positive criminology: A frame work to protect victims of cyber crime. In N. Ronel & D. Segev (Eds.), Positive criminology (pp. 276–291).

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Wurthmann, K. A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2008). The stigmatization and devaluation of elites associated with corporate failures: a process model. Academy of Management Review, 33 (1), 231–251.

Hettigei, N.T. (2005). The Auditor’s role in IT development projects. Retrieve from http://www.isaca.org/Journal/Past-Issues/2005/Volume-4/Pages/The-Auditors-Role-in-IT-Development-Projects1.aspx .

Bradbury, D. (2013). India’s Cybersecurity challenge. Retrieve from http://www.infosecurity-magazine.com/view/34549/indias-cybersecurity-challenge/ .

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author thanks four anonymous CRIS reviewers for their insightful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bryan School of Business and Economics, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, P. O. Box 26165, Greensboro, NC, 27402-6165, USA

Nir Kshetri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nir Kshetri .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kshetri, N. Cybercrime and cybersecurity in India: causes, consequences and implications for the future. Crime Law Soc Change 66 , 313–338 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9629-3

Download citation

Published : 10 September 2016

Issue Date : October 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9629-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Secondary Victimization

- Trade Association

- Informal Institution

- International Political Economy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Internet ›

Cyber Crime & Security

Cyber crime in India - statistics & facts

Who is affected by cyber crime, challenges in dealing with cyber crime, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Number of cyber crimes reported in India 2012-2022

Number of cyber crimes reported in India 2022, by leading state

Average total cost per data breach worldwide 2023, by country or region

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Cyber crime arrested and charged count across India 2022, by crime type

Related topics

Recommended.

- Internet usage in India

- IT industry in India

- Social media usage in India

- Fintech in India

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Share of cyberattacks in worldwide regions 2022, by category

- Premium Statistic Number of cyber crimes reported in India 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of cyber crimes reported in India 2022, by leading state

- Basic Statistic Value of expenditure towards cyber security India 2019-2022, by sector

Share of cyberattacks in worldwide regions 2022, by category

Distribution of cyberattacks in selected global regions in 2022, by category

Number of cyber crimes reported across India from 2012 to 2022

Number of cyber crimes reported across India in 2022, by leading state (in 1,000s)

Value of expenditure towards cyber security India 2019-2022, by sector

Value of expenditure towards cyber security in India in 2019 with a forecast for 2022, by sector (in million U.S. dollars)

Type of crimes

- Premium Statistic Cyber stalking and bullying cases reported in India 2022, by leading state

- Premium Statistic Number of cyber crimes related to sexual harassment India 2016-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of cyber crimes related to online banking across India 2016-2022

- Premium Statistic Cyber fraud incidents reported in India 2022, by leading state

- Premium Statistic Number of online identity theft offences reported in India 2022, by leading state

Cyber stalking and bullying cases reported in India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber stalking and bullying incidents against women across India in 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber crimes related to sexual harassment India 2016-2022

Number of cyber crimes related to sexual harassment and exploitation across India from 2016 to 2022

Number of cyber crimes related to online banking across India 2016-2022

Number of cyber crimes related to online banking across India from 2016 to 2022

Cyber fraud incidents reported in India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber fraud cases reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Number of online identity theft offences reported in India 2022, by leading state

Number of online identity theft offences reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Motive of crimes

- Premium Statistic Fraud as motive for cyber crime in India 2022, by leading state

- Premium Statistic Sexual exploitation as motive for cyber crimes India 2022, by leading state

- Premium Statistic Extortion as motive for cyber crime in India 2022, by leading state

- Premium Statistic Piracy as motive for cyber crimes India 2022, by leading state

Fraud as motive for cyber crime in India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber crimes with motivation to defraud reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Sexual exploitation as motive for cyber crimes India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber crimes with sexual exploitation as motive reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Extortion as motive for cyber crime in India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber crimes with extortion as motive reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Piracy as motive for cyber crimes India 2022, by leading state

Number of cyber crimes with piracy as the motive reported across India in 2022, by leading state

Arrests and convictions

- Premium Statistic Cyber crime arrested and charged count across India 2022, by crime type

- Premium Statistic Number of arrests and charges for cyber crimes across India 2022, by gender

- Premium Statistic People arrested for cyber crimes across India 2022, by leading state

Number of persons arrested and charged for cyber crimes across India in 2022, by crime type

Number of arrests and charges for cyber crimes across India 2022, by gender

Number of people arrested and charged for cyber crimes across India in 2022, by gender

People arrested for cyber crimes across India 2022, by leading state

Number of people arrested for cyber crimes across India in 2022, by leading state

Attitudes and opinions

- Premium Statistic Employees worldwide who know their role in combating cyber crime 2022, by country

- Premium Statistic Global biggest cybersecurity threats in the following year per CISOs 2023

- Premium Statistic Main consequences of cyber attacks worldwide 2023

- Premium Statistic Organizations hit by ransomware attacks 2022-2023, by country

Employees worldwide who know their role in combating cyber crime 2022, by country

Share of organizations worldwide where employees understand their role in protecting the company from cyber crime in 2021 and 2022, by country

Global biggest cybersecurity threats in the following year per CISOs 2023

Most significant cybersecurity threats in organizations worldwide according to Chief Information Security Officers (CISO) as of February 2023

Main consequences of cyber attacks worldwide 2023

Most important consequences of cyber attacks worldwide as of February 2023

Organizations hit by ransomware attacks 2022-2023, by country

Share of organizations worldwide hit by ransomware attacks in 2022 and 2023, by country

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

Subscribe Now! Get features like

- Latest News

- Entertainment

- Real Estate

- MP Board Result 2024 live

- Crick-it: Catch the game

- Election Schedule 2024

- Win iPhone 15

- IPL 2024 Schedule

- IPL Points Table

- IPL Purple Cap

- IPL Orange Cap

- AP Board Results 2024

- The Interview

- Web Stories

- Virat Kohli

- Mumbai News

- Bengaluru News

- Daily Digest

Financial fraud top cyber crime in India; UPI, e-banking most targeted: Study