Monday, 6 May

Search for news, browse news stories.

- All opinion

- All featured

New The Journal of Beatles Studies launches to establish The Beatles as object of academic research

Dr Holly Tessler , programme lead for the University of Liverpool’s new The Beatles: Music Industry and Heritage MA , is launching The Journal of Beatles Studies – a brand new open access journal published by Liverpool University Press .

The Journal of Beatles Studies is the first journal to establish The Beatles as an object of academic research, and will publish original, rigorously researched essays and notes, as well as book and media reviews.

It establishes a scholarly focal point for critique, dialogue and exchange on the nature, scope and value of The Beatles as an object of academic enquiry and seeks to examine and assess the continued economic value and cultural values generated by and around The Beatles, for policy makers, creative industries and consumers. The journal also seeks to approach The Beatles as a prism for accessing insight into wider historical, social and cultural issues.

Co-edited by Dr Holly Tessler and Paul Long at Monash University, the journal will be published twice a year, with the inaugural issue being in September 2022. The journal is sponsored by the University of Liverpool library.

Dr Holly Tessler and Paul Long said: “We are really excited to launch The Journal of Beatles Studies.

“We intend the journal to be a hub for research, discourse and debate about the Beatles, with an emphasis on new ideas and emerging perspectives.

“Sitting alongside the University of Liverpool’s new MA degree, The Beatles, Music Industry and Heritage, as well as its new Yoko Ono Lennon Centre , The Journal of Beatles Studies is another exciting new space for the academic and cultural study of the Beatles that they and their legacy so richly deserve.

It is sometimes daunting to consider how interest in the Beatles continues unabated, nurtured by new books, films and of course the endurance of the band’s music itself and its presence across radio, film, television and the digital sphere.

“Equally prodigious is the range of scholarly attention to the meaning of the Beatles and responses to their cultural legacy and continued creative inspiration which is truly global in its reach.

“A desire to map and make sense of this field of production prompts the founding of The Journal of Beatles Studies which provides an international, inclusive, interdisciplinary focal point for ideas, exchange and quality research.”

Clare Hooper, Head of Journals at Liverpool University Press said: “We are really excited to be launching The Journal of Beatles Studies.

“The journal will be an extremely valuable resource for all scholars with an interest in the subject and it’s fitting that the first interdisciplinary journal dedicated to the study of the Beatles will begin life in Liverpool.”

For more information please visit: www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/r/beatles

More World’s only Masters in The Beatles, Music Industry and Heritage launched

- DU news story 2

- Featured Story 2

- Press Release

- Department of Music

- Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

- School of the Arts

- The Beatles

Diggit Magazine

Enter your email address to subscribe to our newsletter (mailchimp).

- Stumbleupon

The Beatles and Globalization in the Sixties

This paper discusses the way The Beatles contributed to changes in youth culture worldwide in the 1960s. It deals with the role of hippy counterculture (Mariska van Schijndel) and the Vietnam War (Rosalie Vaarten), the influence of technological developments and media after World War II (Karlijn Raaijmakers), the role of language (Aniek van den Brandt) and the use of music and sounds from different cultures (Naomi Dominicus). The paper shows that globalization is not just a phenomenon of the Internet Age, but also took place long before the Internet even existed.

Introduction

Globalization is a ‘catchword’ to refer to a certain historical phase in which interconnectedness and mobility acquired unexperienced global scale levels (Wang et al., 2013: 1). These historical phases, such as the colonial era and the post-Cold War era, are times of ‘deepened globalization’ which lead to the creation of a new world order (Wang et al., 2013: 2). As a result, we are now living in a world greatly defined by “ intensified global flows, both in volume and in speed, of people, goods, capital and symbolic social, political and cultural objects including language and other semiotic sources ” (Wang et al., 2013: 2). Social scientists often refer to globalization as something that has – next to terrorism – dominated the world since the last decades of the twentieth century (Wallerstein, 2004: 1). By stating this, social scientists imply that globalization is a new phenomenon. Many scientists study globalization in the context of the Internet Age, but in reality globalization is something which also took place long before the Internet emerged (Wang, 2013: 1). Many popular singers of the 21st century enjoy their worldwide popularity for a great part thanks to the internet. Through Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and other social media, they can easily have an influence on people around the world.

In the 1960s, The Beatles became extremely popular around the globe, and they had a great influence on youth culture, way before the internet was invented. How did The Beatles contribute so greatly to changes in youth culture worldwide in the 1960s?

This paper discusses social, cultural, political, linguistic and technological factors that created ‘global patterns’ of cultural and social behaviour and that made it possible for The Beatles to contribute to changes in youth cultures around the globe in the 1960s. We will look at the social and cultural upheaval of the hippie counterculture, the political upheaval during the Vietnam War, the technological and media developments after World War II, language, and the use of music and sounds from various cultures around the world.

Trendsetters in the Hippie Counterculture

‘Counter’ by definition is an opposition or defence against something. A counterculture is the result of a reaction to a certain culture with a contradictory opinion or action. Counterculture is “ the tradition of breaking with tradition ’’ or “ crashing through the conventions of the present ’’ in order to ‘ ’open a window onto that deeper dimension (…) of the truly new in human expression and endeavour ’’ (Goffman and Joy, 2004: 17). In a counterculture, the participants exchange controversial ideas and innovations, pushing themselves into a new territory in which they hope others will follow (Goffman and Joy, 2004: 10). The focus of a counterculture is not the political, but the ‘ ’power of ideas, images, and artistic expression ’’ (Goffman and Joy, 2004: 10). In examinations of radical youth culture of the 1960's and 1970's reference is often to a ‘hippie counterculture’, which insists that ‘hippies’ and ‘counterculture’ have the same definition (Starr, 1985: 239). Though this is not the case, as hippies were a subgroup within counterculture.

Under the influence of protest movements of students and young people, the hippie movement developed in San Francisco in the mid-1960s. During this period, international connections broadened and intensified, which resulted in the fact that this movement and its ideas could quickly spread throughout the United States as well as the rest of the world, mainly to Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Besides, the background of Western European countries was similar to the United States, which also resulted in young people participating in protest movements and feeling attracted to the ideas and innovations of the hippie culture (Oved, 2012: 4).

In this counterculture, hippies rejected materialism, competitiveness, militarism, rationality, and Western religions and creeds (Becker, 2007: 24). Furthermore, they opposed to all authority, from school rules and parental authority to the formalities of the courts (Falk and Falk, 2005: 188). Instead of following the mainstream materialist society, which they called the ‘plastic society’, hippies tried to create their own alternative society with alternative values and way of life (63). Their ideal community was based on peace, equality, harmony, sexual liberation, drug use, and most importantly: love (Becker, 2007: 24-25).

These cultural shifts created a generation gap between the youth of the 1960s and their parents. The teenagers regarded the materialist society as ‘the hallmarks of their parents’ generation’ (Misiroglu, 2015: 113). Therefore, Jerry Rubin’s quote ‘ ’Don’t trust anyone over thirty ’’ became famous among the youth. The Beatles managed to participate in the social and cultural upheaval of the 1960s by capturing the spirit of the hippie counterculture.

Just ‘ordinary’ boys

The Beatles were the proof for hippies that society does not require any authority in order to be successful. All four were just young ‘ordinary’ boys from England’s hinterlands, of whom none had an easy youth. Lennon’s and Starr’s parents divorced when they were young, McCartney’s mother died when he was only 14 years old, and Harrison grew up in a house which had an outdoor toilet and heat from a single coal fire (Harrison, 1980: 21). Lennon’s relationship with his parents after the divorce was bad: his father was out of sight for the next twenty years and Lennon ended up living with his aunt and uncle instead of his mother (Lennon, 2005: 11). Since the age of twelve, Starr was not able to go back to school as he had to spend too much time in hospitals because of health issues. Their background proves that they were just like anyone else, but still were able to achieve huge successes. Besides, as mentioned above, hippies rejected all forms of authority. Their background showed them that society does not need school rules or parental authority in order to achieve something big in life. Also, the fact that ‘ordinary’ boys had so much success by creating their own songs without any help of the music industry, gave young people around the world hope and optimism for their future (Misiroglu, 2015: 67).

Lyrics capturing the ‘hippie spirit’

The Beatles wrote songs which captured the ideals of the hippie movement. In their song All You Need Is Love , they criticize the material culture by implying that you do not need any money, authority, or traditional rules; the only thing that is important, is love. From then on, ‘love’ became “ the catchword of the hippie culture in the 1960s ” (Falk and Falk, 2005: 188) and “ the central motif of Hippie immanent philosophy ” including an “ all-embracing love for mankind ” (Hall, 1986: 181).

The hippies wanted to reach sexual liberation by spreading the message of love. Therefore, they often referred to the sentence “ make love, not war ” (Falk and Falk, 2005: 188). Again, The Beatles captured this dream in their lyrics. The phrases ‘ ’Why don’t we do it on the road? / No one will be watching us / Why don’t why do it on the road? ’’ ( Why Don't We Do it in the Road? ) and ‘ ’She’s a big teaser / She only played one night stands ’’ ( Day Tripper ) directly refer to the ideal of sexual liberation of the 1960s.

In additionto sexual liberation, the hippie community was also based on drug use, as ‘ ’love were drugs of all kinds ’’ and ‘’ getting high was the symbol for final liberation’’ (Falk and Falk, 2005: 188). The Beatles often referred to this feature of the hippie community in their lyrics, for example in their songs With A Little Help From My Friends and Mystery Tour : ''I get by with a little help from my friends / I get high with a little help of my friends'', '''Roll up / And that's an invitation Roll up for the mystery tour'' . Not only in their lyrics they encouraged drug use, but also in their own behaviour. In an interview for the Independent Television News in 1967, the newscaster asked Paul McCartney if he had ever taken LSD, to which his answer wass he did about four times. Still McCartney did not think he encouraged his fans to take drugs by telling the truth, because he believed ‘ ’that is up to the newspapers, to you, the television ’’. He even stated that he did not want to spread the word about drugs. Even though McCartney was right about the impact of media on society, The Beatles were aware of their huge impact on youth. John Lennon even stated in an interview with the London Evening Standard in 1966 that The Beatles are ‘ ’more popular than Jesus ’’ and therefore have a greater influence on the youth than Christianity.

The young people with the same 'hippie spirit' came together at concerts and music festivals. These concerts and festivals created the sense of ‘togetherness’ among hippies in their own alternative community. They functioned as gathering points and created ‘ ’a feeling of belonging to a widespread movement ’’ (Oved, 2012: 61). The Beatles were trendsetters in this, as they provided the first United States tour (Oved, 2012: 60).

The Beatles’ lyrical content, behaviour, drug use, and world tours made them the ‘ ’trendsetters in everything, from clothing to hairstyles to recreational drug use ’’ (Misiroglu, 2015: 68). Parents feared that The Beatles had a bad influence on their children ‘ ’with their long hair and loud music’’ , and some parents even considered the four members dangerous (Davies, 2014).

Youth Rebellion during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a war during which the communist North Vietnam and the Viet Cong fought against the South of the country, which was supported by the United States. In 1973, the USA stopped supporting South Vietnam and as a result the South collapsed in 1975. The communist army took control of Saigon and ended up winning the war. Vietnam became a united, communist nation state. The Vietnam War led to global protests and rebellion, especially among the youth. This political upheaval caused by the war is something that The Beatles stimulated and played a part in as well.

Influence of the television on the Anti-War Movement

In the 1960’s, around the time of the outbreak of the war, television was introduced in many American and European households. The introduction of this new medium caused drastic changes and revolutions (Emerald Group Publishing, 2004). Through this new medium, people could suddenly follow everything that was happening all over the world. Many see the television as “ one of the most important phenomena ” in current cultural globalization (Kuruoğlu, 2004: 2). Also, it was an important cause for American citizens – but also for people in other places in the world – to get involved in the Vietnam War, even though it was taking place in a country almost 9,000 miles away from the United States.

The Vietnam War was connected to globalization because television allowed people from all over the world to see the horrific things that were happening in Vietnam from their homes. Due to the progress that globalization made with the invention of the television, not only the population of Vietnam and the American veterans, but also the rest of the world became concerned about the war and formed opinions about it.

This global involvement led to rebellions and protests all over the world, especially by the ‘protest generation’ (Giugni, 2004: 180), which was the youth of the 1960’s. The United States were obviously violating the human rights of the Vietnamese people, but also their own soldiers were suffering in Vietnam. Many soldiers died and the ones who did come home often had to deal with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or disabilities. Many people objected to these violations and the horrific images they saw on their television, and started protesting against the Vietnam War: 1968 became a very turbulent year (Lamb, 2016: 333).

The Beatles’ popularity and their political opinions

Liverpool was a centre of popular culture in the 1960’s. Not only The Beatles, but also many other pop groups had their home in Liverpool, as well as the Liverpool Poets, a group of Poets influenced by the hippie culture. The hippie culture ‘ ’featured communal living, drug use and so on; The Vietnam War, racial unrest and the pressure to adapt to pre-established norms frustrated them…The Liverpool Poets wrote extensively on the subject of love, war and peace ” (Li, 2014: 69). While the antiwar demonstrations were going on globally, The Beatles wrote songs in which they expressed their opinion on the war and talked about it in interviews: “ The Beatles had done a fairly good job following Epstein’s advice to not answer questions about American politics, but they could resist no longer. They came out against the Vietnam War at a press conference hours before their final New York concert ” (Leonard, 2014).

‘Make Love, not War’

The Beatles leaned, as discussed in chapter 1, strongly towards the hippie ideology of ‘make love, not war’. The myth of worldwide love, that was alive in the 1960’s, “ centered in some way around the Beatles and connected with what we would now call youth culture or the counterculture ” (Burns, 2000). Back then there was a real need for such a ‘love myth’ in America to work against the ugly realities of the Vietnam War, and people began to see The Beatles as the face of this idea. Many of their songs aligned with this ideal of love and peace from the hippies, like All You Need Is Love , or Revolution in 1968 (Burns, 2000). This song was written by John Lennon and came out in the United States on August 26, 1968, on the first day of “ the frightening climax to a year of violence ” (Platoff, 2005: 244). This climax had been triggered by horrific images of Chicago police beating up anti-war protesters, delegates and news reporters that, one night, were shown on television. It led to mass protests and violence for days on end. Lennon later stated that he set the song out at this time on purpose, to give his opinion about revolution. Also, he consciously made the choice to release the song “ as a single: as a statement of The Beatles’ position on Vietnam and The Beatles’ position on revolution ” (Platoff, 2005: 246). However, Lennon stated this twelve years later in an interview and nothing in the lyrics verifies that the song is really about the Vietnam War, so this was probably not the case. Still it is pretty obvious that people who heard the song automatically made this connection, especially keeping in mind the timing of the release. Also, it is understandable when you look at the lyrics:

You say you want a revolution,

Well, you know

We all want to change the world.

You tell me that it’s evolution,

But when you talk about destruction,

Don’t you know that you can count me out.

But if you want money for people with minds that hate,

All I can tell you is brother you have to wait.

The Beatles have never released a song that was clearly about the Vietnam War, although some of their songs from the time seemed to fit perfectly with the topic. Another example of such a song is Strawberry Fields Forever , which came out in 1967, again written by John Lennon. The song is meant to be an “ expression of life’s absurdity ”, which is very fitting for the troubled times that the world was going through. “ John Lennon shows no bitterness or anger at the fact that “nothing is real” … though he does seem to be critical of people who don’t acknowledge the absurdity of reality, evident in the lines, “Living is easy with eyes closed/Misunderstanding all you see” ‘ ’ (McClary, 2000: 10). This could be interpreted as him believing people shouldn’t close their eyes when it comes to war; as if he thought it had to be acknowledged how wrong and absurd everything about it was. Because they were so popular all over the world, their message reached lots of people. It is therefore likely that songs like these have been a stimulating factor in the anti-war movements, or at least helped shape many people’s opinions about the war.

Technological developments after World War II

When World War II ended in 1945, society got back into a stage of recovery, slowly getting back into an upwards spiral again. The destruction that the war left was being fixed, which made production and employment rates rise (Eichengreen, 2007: 59). People were able to celebrate their freedom again. During the war, technology had developed a lot, because it was necessary to make better weapons, tanks, etcetera (56). After the war, these technological inventions continued, but for different purposes (56). Instead of weapons and tanks, people invented LP’s and Compact Cassettes, which will be discussed below. These new forms of ‘cultural technology’ opened up a lot of doors for other cultural developments, such as theatre and music.

Globalization got a huge boost, because these developments made it possible to, as everyone does on social media nowadays, ‘share’ a lot more. Culture was able to spread faster over the entire world, which made it easier for artists, such as musicians, to get the recognition they wanted.

This brings us back to our main topic: The Beatles and their influence on youth culture. How did post-war technologies make it possible for The Beatles to grow their fan base so much that nowadays people still recognize their influence?

Commercial television

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, near the end of World War II, most television programming was stopped for some time (Abramson, 1987: 3). It was only in 1946 that these television stations went back on the air (18). But now, something had changed; television was used more and more for cultural purposes instead of war purposes, such as propaganda. The popularity of the TV increased really fast in many countries and in the sixties, most families owned a television (24).

The Beatles benefited from the rise in popularity of television by getting promoted on television and doing live performances. They appeared on the American television show The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time in 1963 (Frontani, 2007: 31). This was a very big event which drew a lot of attention from fans, which were mainly young women and teenage girls. 1963 was the year of their breakthrough and television obviously played a big part in this breakthrough, as they could now reach more people in different countries all over the world. This is also an obvious example of the world becoming more global and having better communication channels, because of these technological inventions.

After The Beatles’ performance on The Ed Sullivan Show , everyone was very impressed, so much that they were asked to appear on various other television and performing shows (Frontani, 2007: 32). This increased their popularity all around the world. They also made several movies, one of them being A Hard Day’s Night , after their album with the same title (Frontani, 2007: 77). These were all very big steps on their way to fame.

From phonograph to LP record

When the phonograph was invented somewhere around the 1870’s, no one, including its inventor Thomas Edison, really saw its (commercial) potential (Tschmuck, 2006: 2). The phonograph ended without the actual practical applications being realized (Houston, 1888: 44). However, in 1887 an inventor called Berliner invented an improved version of the phonograph called the gramophone, which was the start of some great developments (Houston, 1888:4444-45).

The music industry evolved slowly but surely and 60 years later, the LP record, also known as the long playing vinyl or gramophone record, was introduced, in 1947 (Eargle, 2003: 371). It would become the most popular form of consumer audio until the CD was introduced.

The LP record is obviously an example of how new technologies increased globalization and made it easier for bands like The Beatles to become more famous around the world. Their first three LP’s made them very successful and known by many people. Time progressed and so did the quality of their LP’s, both in sound and in the music itself. They started doing fewer covers and more originals. Since most families had a record player in the house and the LP record had not been around for that long, many people bought The Beatles’ LP’s, which made them gain a large audience. After their 1965 LP record Rubber Soul topped the charts, they started ‘’taking over the world’’, from the United Kingdom all the way to Australia and America (Kurt, 1998: 9-10). Youth would almost beg their parents for ‘the next LP from The Beatles’. Their success was made possible through all these technologies.

The start of the digital revolution

Two other steps in technology that had a big impact on the world were the Compact Cassette (also known as Music Cassette (MC)) and the Compact Disc (CD). The Compact Cassette arrived in the early 1960s, but it took some time for it to gain popularity (Tschmuck, 2006: 150). There was more interest in the CD when it got invented in 1979. It was described as the ‘child of the digital revolution’, which began in the early 1980s and it was a new step to the technologically developed society we live in now (Tschmuck, 2006: 151). After four years, the CD gained popularity and it became more clear that this digital revolution was actually starting.

The Beatles already split up before the CD arrived, but yet they hugely benefited from it. Almost everyone owned a CD player and bought CDs from The Beatles as they had better sound quality than the LPs and cassettes. The Compact Cassette has a comparable story with the LP record we discussed above. It created a more global world and made The Beatles able to share their work more with the public, since most people had a cassette player and used it for many years. This new technology made artists like The Beatles able to spread their music around the world really quick.

Singing Songs in Other Languages than English

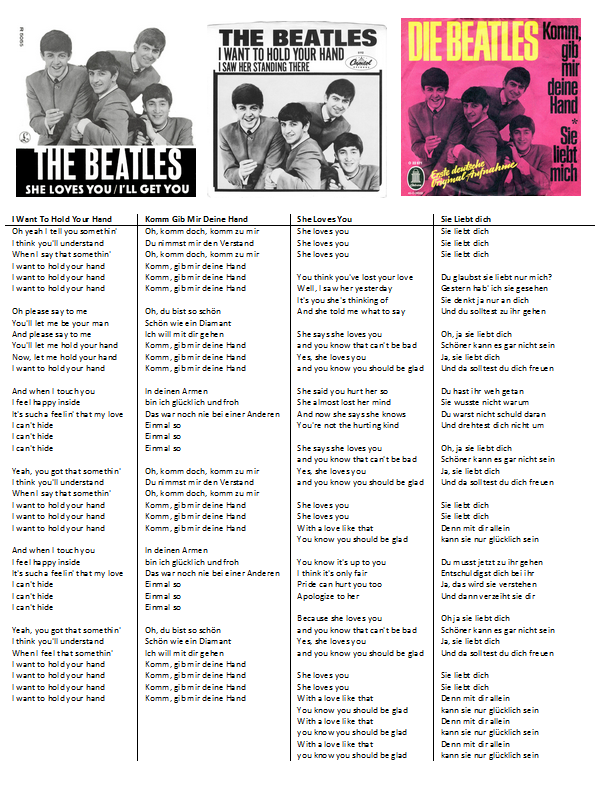

The Beatles sung most of their songs in English, but sometimes they added some elements of other languages in their songs as well. The song Michelle is known for the French sentence: ‘ ’Michelle, la belle, sont des mots qui vont très bien ensemble ’’ and in Sun King The Beatles added some Spanish, Portuguese and Italian words next to the English lyrics. The most famous non-English songs are the songs The Beatles translated into German in 1964. ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ became ‘Komm Gib Mir Deine Hand’ and ‘She Loves You’ became ‘Sie Liebt Dich’. But why did The Beatles decide to sing songs in non-English? And did it actually take their career to a higher level?

The spread of the English language

If you think about it, it is not strange that The Beatles translated their songs in other languages. In the last century, the English language has become a worldwide language, but that certainly did not happen suddenly. Political, economic, social and cultural changes have affected the linguistic landscape in Europe in the 20th century. Through for example internationalisation and large scale-migration the use of English by non-native speakers of English has increased a lot. English music also stimulated the globalisation of the English language. The spread of English has been (and still is) a long-term development, so back in the 1960’s this had not gone as far is it has nowadays (Cenoz & Jessner, 2000: 1). Therefore, in the 1960’s, many people on the continent did not understand the English language very well. For many listeners, however, it is important to understand the lyrics of a song, because lyrics are an important form of communication with the audience. There is even a theory that claims that song writers tend to regress to a more basic form consciously to please the listeners, because a song that is easy to understand reaches a bigger audience than a song that is difficult to understand (Pettijohn II & Sacco Jr., 2009: 298). In other words: a song needs to be understandable, otherwise the listeners won’t be reached. So, to reach a bigger audience for their music, the producers of The Beatles thought it was important to put some international elements in their songs and to even translate some of them.

Language and identity

Most researchers agree that language and identity are inseparable: ‘ ’Identity constructs and is constructed by language ’’ (Norton, 1997: 419). But the fact that many people speak the English language, does not mean they identify with it. Researcher J. House stated that ELF (English as a Lingua Franca) is a “ language for communication ” rather than a “ language for identification’’ (as cited in Canagarajah, 2006: 199). In other words, multilingual speakers will not feel a cultural affinity with the English language if it’s not their native language. But that does not mean cultural affinity is not important, on the contrary. House shows this with the example of how the revival of German folk music ( Schlager ) could be a reaction against the spread of English pop music; people do not just leave their native language behind and that can be seen in the music industry. Knowing that, we can say that translating Beatles songs has definitely had some influence in the spread of the fame of The Beatles around the world, because people identify earlier with songs that are sung in their native language.

As said, the two most famous non-English songs of The Beatles are original English songs, fully translated in German. The Beatles had an orientation on Germany from the beginning. They had some very early gigs in Hamburg, so Germany had met the phenomenon of ‘The Beatles’ already at an early stage of their career. But even though the German people already knew them and their songs, Odeon, the German branch of EMI (the parent company of the Beatles' record label, Parlophone) thought that The Beatles' records would sell better in Germany if they were sung in German.

Translating songs in that way is not a strange phenomenon. Back in the 1960’s many big artists and producers made German versions of their songs for the European market (Flippo, 2016). Even though The Beatles detested the idea of translating their songs in German, the project still went ahead. Two songs were translated: I Want To Hold Your Hand and She Loves You . The translations, Komm Gib Mir Deine Hand and Sie Liebt Dich , were released in Germany in 1964. It is obvious that the songs hardly changed in content; it is just the language that has changed.

A wider public

The German songs did pretty well in Germany, so they surely helped to reach a big audience in Germany. ‘Komm Gib Mir Deine Hand’ and ‘Sie Liebt Dich’ a fifth and seventh place in the West German Media Control Singles Place (the German hit-parade). But, the original English version of 'She Loves You' reached first place in the German hit-parade. It even became The Beatles’ best-selling single worldwide. ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ ended on the seventh place, just like the German version. So even though the German producers of The Beatles were sure that the songs would only sell if they were translated in the German language, in the end the English versions of the songs turned out to be just as or even more successful.

But, other than the translated German versions, which did well, ‘Michelle’, the song with the French elements, actually was extraordinarily successful in France and Belgium. In both countries, it reached first place in the national charts. It must be said though that ‘Michelle’ was an overall hit, so the success was not specific to countries with French as the main language. Michelle was also very successful in Britain itself and in other European countries. The song even won the Grammy Award for the Song of the year in 1967, so whether the French elements really had an impact on the song’s success in French-speaking countries, is very hard to say.

Did it work?

We can suppose The Beatles released records in different languages in order to achieve a wider public. The translating of songs had ‘globalization’ of The Beatles as a purpose. It is hard to say how much those non-English songs helped spreading the fame of The Beatles. Looking at the identification with songs, you could say that translating the songs definitely must have had some influence on the globalization of The Beatles. But the English songs were in general just as successful (or sometimes even more so) than the songs with elements of other languages. That does not mean the non-English songs did not have any influence at all. The effect of singing in German, was that for some people the message of the song became more clear, because English back than wasn’t as widespread as it is today. Next to that, the translated songs surely were valuable for a part of the non-English public, because they did – just as a lot of English songs – very well in the European hit charts. As the record producer of The Beatles, George Martin, later said about the German translations of The Beatles-songs: ‘‘ They (The Beatles) were right, actually, it wasn’t necessary for them to record in German, but they weren’t graceless, they did a good job’’ (Lewishon, 1988: 38).

More than just Popular Music

The youth culture of the sixties created a bridge between the growing group of students and the new possibilities in their spare time by using music. The joy the youth experienced in listening to music became the highly needed counterpart to their stressful school life. Hand in hand with this development went the rise of popular music and nightlife (Tillekens, 1998:293-294). Roy Shuker describes popular music as follows: “… it consists of a hybrid of musical traditions, styles, and influences, with the only common element being that the music is characterized by a strong rhythmical component, and generally, but not exclusively, relies on electronic amplification ” (Shuker, 2016:6). Popular music created an environment in which young people could meet each other and express their feelings in a whole new way. The freedom and responsibility the youth took by choosing music, clothing and where to meet prepared them in one way or another for their independent adulthood (Tillekens, 1998:294).

As part of the developments of youth culture in the sixties came The Beatles. The group started off playing popular music, which at the time was rock ‘n roll. With over 200 songs produced between the release of Love Me Do in 1962 and their disbanding in 1970, The Beatles played a significant role in the development of youth culture (Inglis, 2000:35). In order for their music to stay interesting they had to try something new once in a while and keep up with the time. As the rock ‘n roll period fades, so do the hard edges of their music. And together with the change of popular music goes a change within people; their rough edges also fade. How was it possible for their music to be so popular among youth around the whole world, and not only in Western countries in which people lived in similar cultures?

Borrowing from different genres

The Beatles innovated new styles for their songs and developed together with their time and public (Inglish, 2000:40). They innovated these new styles by borrowing from different genres, but they never really moved from one genre to another; the group would always stick to their popular music. By using all these different genres in their songs they created a wider public around the world (Pedler, 2003:256). For instance, Yesterday ( 1965) was their first song to make use of classical music elements, even though it was not their first song to use orchestral strings. Gould says: “ The more traditional sound of strings allowed for a fresh appreciation of their talent as composers by listeners who were otherwise allergic to the din of drums and electric guitars. ” (Gould 2007: 278)

Indian sounds

In August 1967 Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, an Indian guru, gave a series of lectures at the London Hilton about Transcendental Meditation. On the 24th of August, The Beatles, except Ringo Starr, attended the lecture and had a moment for themselves with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi afterwards. Inspired by his Eastern Philosophy they decided to participate in a meditation course by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh, India, in February 1968. Starr and McCartney were the first to leave, with Lennon and Harrison following a few weeks later when Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was accused of sexual misconduct. The Beatles’ had lost faith in him; this can be heard in the song Sexy Sadie (1968) in which ‘Sexy Sadie’ equals Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and they sing: “She made of fool of everyone. Sexy Sadie. However big you think you are. Sexy Sadie. ” Despite this incident, The Beatles’ stay in India gave them a lot of inspiration and resulted in one of their most productive periods as songwriters. They have said they wrote more songs than could fit one single album (Joe, 2009:1-4). Therefore, many of the songs on the album ‘The Beatles’, also known as The White Album’ , (1968) and some further songs were written during and/or about their course in Rishikesh. The album got mixed reviews when it was released. Some critics found its songs unimportant or discriminative, but others praised Lennon and McCartney for their song writing. Despite that the album got mixed reviews, it was the best sold double album at the time (Joe, 2008:5).

George Harrison in particular was very fond of the Indian styles of music, even before their trip to India. When Rubber Soul was released in 1965, the world was surprised by the second track Norwegian Wood, as it was the first popular song in which a sitar was used. A sitar is an Indian stringed instrument with a very unique and slightly psychedelic sound. As innovative as the sitar sounded, it was only used to back up the acoustic guitar. Although the song still had a traditional Western melody, it was inevitable that such experiments would be done more in popular music from now on. The Beatles’ next album Revolver (1966) contained the song Love You To , which was George Harrison’s first song to be composed entirely on the sitar. One of the most complex songs in Harrison’s Indian-field is Within You Without You (1967) in which Indian instruments – played by Indian musicians – as well as a Western string ensemble are playing. This song uses traditional Indian rhythmic patterns together with Western popular music. Besides the influences on their music, the Indian influences are also found in their lyrics. In My Sweet Lord (1970) for example, Harrison mentions a few Indian Gods and movements (Guerrero, 2015:34-36).

Conclusion

Globalization created new forms of social structures around the world. The transition from industrial society to a transnational networked society, meant that people became more and more interconnected with each other. This network society emerged from cultural, social, political and technological processes. In the same period, The Beatles became immensely popular around the world.

In culture, a new global community – the hippie counterculture – emerged because of the intensified international connections and similar social backgrounds. The Beatles played a big role as trendsetters in the hippie counterculture movement of the 1960’s by including the ideals of the alternative culture in their songs and expressing these ideals through their behaviour and looks. In this way, they were able to contribute to changes in youth cultures.

The global political upheaval about the Vietnam War by the young protest generation – which the hippie counterculture movement was part of – greatly benefited from the introduction of the television and the fact that more and more households got this new medium in their homes. This made it possible for them to follow what was happening in Vietnam. Even though none of The Beatles’ music overtly refers to the Vietnam War, their messages in the songs fit perfectly with the ideology of the protest generation (‘Make love, not war’). Also, the singers were not afraid of expressing their political opinion every now and then. Because of their immense popularity worldwide, their lyrics and political opinions reached the youth around the world and could change the way they looked at the world around them.

After World War II, as a consequence of technological developments and television becoming more and more popular people could watch The Beatles from their homes. The Beatles also made use of other new technologies like LP’s and CD’s which were sold worldwide. By using these technologies, The Beatles were able to expand their (young) fan base around the world, and therefore were able to change the way they act and look at the world through their cultural and political messages.

In order to achieve an even wider public, The Beatles chose to release records in different languages. Even though the English songs were just as successful as the non-English songs in the European hit charts, it became easier for the public to understand The Beatles’ messages on the Vietnam War, drug use and other ideological messages.

By looking at the sounds and types of music The Beatles chose, it explains why their music was interesting and different for countries all around the world and not just in Western countries. Popular music, which became and still is especially popular in Western countries, created an environment in which young people could meet each other and express themselves. By borrowing elements from different genres, especially Indian sounds, The Beatles’ were able to keep their music interesting for the public and created a wider public of interest beyond the West.

The discussed social, cultural, political and technological factors created ‘’global patterns’’ of cultural and social behaviour. In their own way, The Beatles contributed and made use of these factors, which made it possible for them to contribute to changes in youth cultures around the world in the 1960’s.

Abramson, A. (1987). The History of Television, 1942 to 2000 . Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minnesota: University of Minnesota

Becker, M. P. (2007). The Edge Of Darkness: Youth Culture Since the 1960s. Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

Burns, G. (2000). The Beatles, Popular Music and Society .

Blommaert, J. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Canagarajah, S. (2006). Negotiating the Local in English as a Lingua Franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics , 26, 197-218. doi: 10.1017/S0267190506000109

Cenoz, J & Jessner, U. (2000). English in Europe: The Acquisition of a Third Language. Great Britain: WBC Book Manufacturers Ltd.

Davies, H. (2014). The Beatles Lyrics: The Unseen Story Behind Their Music. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Eargle, J. (2003). Handbook of Recording Engineering . Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Eichengreen, B.J. (2007). The European Economy Since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Emerald Group Publishing. (2004). Marketing in the 21st Century: an Emerald Guide .

Falk, G. & Falk, U. (2005). Youth Culture and the Generation Gap. New York: Algora Publishing.

Flippo, H. (2016). The Beatles’ Only German Recordings. Retrieved from http://german.about.com/od/musicartists/fl/The-Beatles-Only-German-Recor...

Frontani, M.R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media . Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Giugni, M. (2004). Social Protest and Policy Change: Ecology, Antinuclear, and Peace Movements in Comparative Perspective . Goffman, K & Joy, D. (2004). Counterculture Through the Ages: From Abraham to Acid House. New York: Villard Books.

Gould, J. (2007). Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Guerrero, R. (2015). The Role of The Beatles in Popularizing Indian Music and Culture in the West. Tallahassee: Florida Sate University

Hall, S. (1968). The Hippies: An American ‘Moment’. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

Houston, E.J. (1888). The Gramophone . Philadephia: The Franklin institute.

Inglis, I. (2000) The Beatles, Popular Music and Society: A Thousand Voices. London: Macmillan Press.

Joe. (2008, March). The Beatles Bible: The Beatles (White Album). Retrieved from www.beatlesbible.com

Joe. (2009, August). The Beatles Bible: The Beatles and India. Retrieved from www.beatlesbible.com

Kurt, L. (1998). The Beatles. Time , 151(22), 9-10.

Kuruoğlu, H. (2004). Reflections of Cultural Globalization in TV: Programmes in Kyrgyzstan .

Lamb, C. (2016). From Jack Johnson to LeBron James: Sports, Media, and the Color Line .

Lennon, J. (1967). All You Need Is Love [Recorded by The Beatles]. On Magical Mystery Tour [LP]. London: Parlophone (14-25 June 1967).

Lennon, J. and McCartney, P. (1967). With a Little Help of My Friends [Recorded by The Beatles]. On Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band [LP]. London: Parlophone. (February-March 1967).

Leonard, C. (2014). Beatleness: How the Beatles and Their Fans Remade the World.

Lewishon, M. (1988). The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962-1970. New York: Harmony Books.

Li, G. (2014). England’s North in Literature and Culture .

McClary, M. (2000). Life is a Carnival: Existential Themes in Music .

Miller, V. (2011). Understanding Digital Culture. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Misiroglu, G. (2015). American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History. New York: Routledge.

Norton, B. (1997) Language, Identity and the Ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly , 31:3, 409-429. doi: 10.2307/3587831

Oved, Y. (2013). Globalization of Communes: 1950-2010. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Pedler, D. (2003). The Songwriting of The Beatles. London: Omnibus.

Pettijohn II, T.F. & Sacco Jr. D.F. Terry F. (2009). The Language of Lyrics: An Analysis of Popular Billboard Songs Across Conditions of Social and Economic Threat. Journal of Language and Social Psychology , 28:3, 297-311. doi:10.1177/0261927X09335259

Platoff, J. (2005). John Lennon, “Revolution”, and the Politics of Musical Reception .

Shuker, R. (2016). Understanding Popular Music Culture. London: Routledge.

Starr, J. M. (1985). Cultural Politics: Radical Movements in Modern History. New York: Praeger.

The Beatles. (1967). Roll Up! Roll Up! On Magical Mystery Tour [LP]. London: Parlophone. (25 April – 7 November 1967).

Tillekens, G. (1998). Het geluid van De Beatles. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

Tschmuck, P. (2006). Creativity and innovation in the music industry. Vienna: University of Music and Performing Arts.

Wang, X. (2013). Globalization in the margins. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Who remembers the Beatles? The collective memory for popular music

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America, Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America

Roles Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing

Roles Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Stephen Spivack,

- Sara Jordan Philibotte,

- Nathaniel Hugo Spilka,

- Ian Joseph Passman,

- Pascal Wallisch

- Published: February 6, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066

- Reader Comments

How well do we remember popular music? To investigate how hit songs are recognized over time, we randomly selected number-one Billboard singles from the last 76 years and presented them to a large sample of mostly millennial participants. In response to hearing each song, participants were prompted to indicate whether they recognized it. Plotting the recognition proportion for each song as a function of the year during which it reached peak popularity resulted in three distinct phases in collective memory. The first phase is characterized by a steep linear drop-off in recognition for the music from this millennium; the second phase consists of a stable plateau during the 1960s to the 1990s; and the third phase, a further but more gradual drop-off during the 1940s and 1950s. More than half of recognition variability can be accounted for by self-selected exposure to each song as measured by its play count on Spotify. We conclude that collective memory for popular music is different from that of other historical phenomena.

Citation: Spivack S, Philibotte SJ, Spilka NH, Passman IJ, Wallisch P (2019) Who remembers the Beatles? The collective memory for popular music. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0210066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066

Editor: Antonella Gasbarri, University of L'Aquila, ITALY

Received: March 2, 2018; Accepted: November 28, 2018; Published: February 6, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Spivack et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data will be publicly available, but the details of this (URL, etc.) will only be clear upon acceptance.

Funding: This study was funded by the Deans Undergraduate Research Fund (DURF) at New York University. This funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. There was no additional external funding received for this study

Competing interests: No competing interests.

Introduction

Since the pioneering work of Ebbinghaus in 1885 [ 1 ], the study of individual memory has been a mainstay of cognitive psychology [ 2 , 3 ]—even during the darkest days of behaviorism [ 4 ]. In contrast, collective memory—what groups of people or entire cultures know—has received comparatively little scientific attention [ 5 , 6 ]. Yet, as exemplified by speculations about archetypes [ 7 ] and the collective consciousness [ 8 ], this question is of longstanding popular interest. An understanding of how cultures remember their past is of critical importance if we are to learn from history [ 9 ]. However, it is largely unknown how much history people remember.

Cognitive psychologists have begun to investigate this question in studies that probe collective memory for political leaders both in the United States [ 10 ] and in China [ 11 ]. Using a free recall paradigm, the results of these studies suggest the existence of a serial position effect [ 12 ] in collective memory, in which the recency portion shows a linear decline. We are not aware of existing literature that has investigated collective memory for other kinds of historical phenomena, such as popular music. Importantly, exposure to music is typically driven by personal interest; in other words, it is self-selective. Conversely, exposure to historical leaders is usually involuntary and often within academic settings, which could affect remembering over time [ 13 , 14 ]. Another key distinction is that of set size, or how many items participants are expected to remember. For historical leaders, this number is finite and relatively small; in the United States there have only been 45 presidents to date. In contrast, for popular music this space is vast and essentially infinite; even the number of top singles on the Billboard popular music charts alone is well in excess of one-thousand since 1940 [ 15 ], which we think could rule out the possibility of a primacy effect in collective memory.

Given these considerations, we hypothesized that there might be a “cultural horizon” beyond which once popular music is effectively forgotten. Should this horizon exist, we aimed to characterize the drop-off as either linear [ 16 ] or exponential [ 1 ]. Finally, we were curious to know whether there are certain “evergreen” songs that are remembered regardless of how long ago they were first popular, akin to flashbulb memories [ 17 ]. In this paper, we aimed to empirically address each of these questions.

We operationalized “popular music” as that which reached the number-one spot on the Billboard Top 100 between the years 1940 and 1957 and on the Billboard Hot 100 from 1958 to 2015 (we refer to both together as the Billboard henceforth). The Billboard is a record chart for the top singles in the United States and is the industry standard by which the popularity of contemporary music is measured. Rankings are published each week and are currently based on three components: record sales, radio airtime and online streaming [ 18 ]. We randomly selected two of the top songs from each year—for a total of 152 songs (see S1 Appendix for a list of the songs we used)—and presented them to participants via Audio-Technica ATH-M20x Professional Monitor Headphones using custom-built MATLAB (2016b) software (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Note that this sampling method is not weighed by time on chart and could be considered biased if this mattered, that is, if the time on chart was non-stationary over time. For instance, songs from the 1960s through 1980s stayed in the top spot, on average, for a much shorter time than in the 2000s. However, there is no empirical correlation between recognition proportion and length of time at the top of the charts in our sample, r (138) = -0.01, p = 0.94, so this is a fair sampling method. As a proxy for self-selected exposure to music, we recorded the play count for each song as it appeared on Spotify—a streaming service with the world’s largest collection of digital music, with over 140 million users [ 19 ]—as of October 8 th , 2017. We also recorded the number of covers and samples for each song as they appeared on whosampled.com—a comprehensive and publicly accessible database—as of June 18 th , 2018.

Participants and task

To satisfy statistical power needs in both psychology and neuroscience [ 20 ], we used a sufficiently large sample to address our research questions. Each participant ( n = 643) was presented with a random selection of seven out of the 152 songs and asked to listen to the selection and report whether they recognized it. Participants were also presented with 5-, 10- and 15-second excerpts deemed to be representative by a consensus panel of seven practicing musicians and professors of music theory and composition and often containing a highly recognizable “lick”—a unique and often repeated pattern of notes played by a single instrument—of each song. To control for the possibility of exposure effects on recognition, all songs and clips were presented in random order. Participants were recruited from the New York University student population for course credit as well as the greater New York metropolitan area, who were compensated for their time at $10 an hour. There were no meaningful differences in any of the measures reported in this manuscript between these two populations. Our sample consisted mostly of young participants, with a mean age of 21.3 years, a median age of 20 years and a standard deviation of 5.09 years. The majority (88%) of this sample was between the ages of 18 and 25, which we considered to be “millennials”. All experimental procedures were approved by the New York University Institutional Review Board, the University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects (UCAIHS). All participants provided their written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Data analysis

630 participants (98% of the total sample) completed the entire study and were used in this analysis. As much of our data is nonlinear, we used Spearman’s rho [ 21 ] to quantify the strength of the relationship between any two variables, such as song recognition and play count. To confirm the validity of our song recognition assay, we used a pairwise t-test to determine whether there are statistically significant differences between recognition for songs compared to clips of 5-, 10- and 15-second durations. In some cases, a pairwise t-test was not appropriate. When comparing phases, the unit of analysis is a song. However, the samples are not independent and the n is not matched between phases, as they contain an unequal number of songs. Instead, to determine whether there are statistically significant differences between the parameters—such as recognition proportion—for each phase, we remained conservative and used a Mann-Whitney U test [ 22 ]. Finally, we performed a normalized multiple linear regression to account for recognition as a function of Spotify play counts, number of covers and number of samples per song. To guard against false positives and to compensate for multiple comparisons, we adopt a significance level of 0.01. This is adequate, as our study is sufficiently powered. We would like to emphasize that we used participants of all ages in the analysis that is presented here. When restricting the same analysis to millennials (aged 18–25, n = 564), we found that there is no meaningful difference in our results when compared to our entire participant pool—only minor numerical differences. This is probably due to the fact that our full sample overwhelmingly consisted of participants in that age range. Spotify’s application programming interface did not contain play count data for two of the 152 songs, so we did not include them in the analysis of Spotify playcounts. Similarly, whosampled.com did not contain data for 14 of these songs, so we did not include those in the analysis of covers and samples.

The main question of this paper is whether there is a cultural horizon for the collective memory for popular music. If such a horizon were to exist, we also wanted to know at what point in time it occurs and whether it is approached linearly or exponentially. To answer these questions, we calculated the proportion of participants who reported to recognize each song and plotted this proportion as a function of the year it reached the number-one spot on the Billboard ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Dots represent the proportion of participants who reported to recognize a given song from a given year. The red curve represents the convolved average proportion for a given year, integrating over 5 years. Magenta dots represent songs from Phase 1 (2001 to 2015), blue dots represent songs from Phase 2 (1960 to 2000) and black dots represent songs from Phase 3 (1940 to 1959). Dashed vertical lines are decade markers.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066.g001

As assessed by Spearman’s rho, the proportion of participants who reported to recognize a given song increases with how recently that song occupied the number-one spot on the Billboard popular music charts, r s (150) = 0.62, p = 1.70e-17. This is not surprising and could be considered a manipulation check. As can be seen in Fig 1 , this trend is far from linear. Whereas the average recognition proportion across all songs and all years is 0.39, we observed three distinct phases in collective memory. Phase 1: recognition was high but decreased steeply and linearly from 2015 until the turn of the millennium. Phase 2: there was a stable plateau at an average recognition proportion of 0.37 from the late 1990s to the early 1960s. Phase 3: starting in the late 1950s, recognition was quite low and slowly decreased toward oblivion.

As we asked our participants to indicate whether they recognized each song in response to hearing it, we probed the feeling of recognition at the time they heard it—not whether they could accurately select the title from a list of related titles. This raises the question of whether our assay is a valid means of capturing recognition memory. To confirm the validity of this method, we replicated the above finding using short excerpts (5-, 10- or 15-second clips) that we deemed to be representative of each song ( Fig 2 ).

Orange curve: 5 second clips, purple curve: 10 second clips, green curve: 15 second clips. All three curves represent the convolved average proportion for a given year, integrating over 5 years. Dashed vertical lines are decade markers.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066.g002

As assessed by Spearman’s rho, recognition for clips is remarkably similar to that of songs, regardless of clip duration, r s (150) = 0.97, p = 1.12e-89. Indeed, when we used a pairwise t-test we found that none of the clip durations yielded recognition rates that are statistically distinguishable from that of the songs, t (151) = 1.29, p = 0.20, d = 0.05; t (151) = 1.49, p = 0.14, d = 0.05; and t (151) = 2.36, p = 0.02, d = 0.10, for 5-, 10- and 15-seconds, respectively. In absolute terms, the mean recognition for 5-second clips is 0.38, for 10-second clips is 0.40 and for 15-second clips is 0.42. Using a pairwise t-test to compare different clip durations against one another we found that the difference between the recognition proportions for 5-second clips and 10-second clips is statistically significant, t (151) = 3.18, p = 0.0018, d = 0.14; the difference between 5-second and 15-second clips is also statistically significant, t (151) = 4.42, p = 1.88e-05, d = 0.10; but the difference between 10-second and 15-second clips is not, t (151) = 1.26, p = 0.21, d = 0.04. This is visually evident in Fig 2 , as the orange trace tends to be below the purple trace, which in turn tends to be below the green trace—but the effect sizes are small. Therefore, it seems that five seconds is enough time for participants to accurately report whether they recognized a given song from a clip. This is consistent with the finding that, in response to hearing 400-millisecond “thin slices” of music, people are able to identify both the song title and artist [ 23 ]. Moreover, it has also been shown that people are able to reliably categorize music genres in as little as 250 milliseconds of hearing a song [ 24 ]. Thus, as there is no difference in recognition between clips and songs, we conclude that we used a valid metric of recognition memory—participants responded far from randomly.

For the next part of our analysis ( Fig 3 ), we quantified the mean song recognition proportion and mean variability—defined here as the average residual from the convolved mean—for each of the three phases we previously identified in Fig 1 .

Left panel: Black dots represent the mean recognition rate for a given phase. Red bars represent the standard error of the mean. Right panel: Black dots represent the average residual—the distance between individual songs to the corresponding point on the convolved average (red curve) from Fig 1 , for a given phase. Red bars represent the standard error of the mean.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066.g003

The mean recognition proportions for each of the three phases are 0.72, 0.37 and 0.19, respectively. To confirm that the difference between each phase is statistically significant, we performed a Mann-Whitney U test to compare Phases 1 and 2, U = 2140, p = 2.28e-09; Phases 2 and 3, U = 14.5, p = 3.83e-12; and phases 1 and 3, U = 840.5, p = 1.31e-05. Indeed, the proportions for each of these three phases have a statistically significant difference from one another, with a general downward trend in recognition across time.

For the mean residual of each phase, we observed a different pattern: during Phase 1—and to a lesser extent Phase 3—the recognition proportion of individual songs closely follows the mean for a given year. In contrast, inter-song variability is high during Phase 2, where the mean does not closely represent recognition rates of individual songs. Some songs in this phase are recognized extremely well, such as “When A Man Loves A Woman” by Percy Sledge (1966) whereas others like “Knock Three Times” by Dawn (1971) are all but forgotten. The mean residual for each phase is 0.08, 0.18 and 0.11, respectively. When we performed a Mann-Whitney U test to determine whether this observation is supported by the data, we found that Phases 1 and 2 have a statistically significant difference, U = 696, p = 0.008; that Phases 2 and 3 have a statistically significant difference, U = 707, p = 1.49e-05; but that Phrases 1 and 3 do not, U = 527, p = 0.30. Thus, recognition variability is highest during Phase 2. This raises the question of what drives the variability in recognition, both between phases and between songs within a given phase. One possible explanation for the former is simply exposure: people are more likely to recognize songs to which they have been exposed more often [ 25 ].

To address the question of whether exposure can account for a sufficiently large proportion of recognition variability, we used play counts on a digital streaming service—in this case, Spotify—as a proxy for self-selected exposure to music and plotted them against recognition proportion ( Fig 4 ).

Magenta dots represent songs from Phase 1 (2001 to 2015), blue dots represent songs from Phase 2 (1960 to 2000) and black dots represent songs from Phase 3 (1940 to 1959).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066.g004

As assessed by Spearman’s rho, there is a considerable correlation between the likelihood of recognizing a given song and its corresponding play count on Spotify, r s (148) = 0.73, p = 6.09e-27. Thus, a substantial amount of the variability in recognition proportion can be accounted for by this metric of self-selected exposure to each song. This is remarkable given that Spotify was launched in 2008, well after the majority (89%) of this music was released, suggesting that the relatively young cohort of participants in our study consumes music primarily through digital streaming. Of course, Spotify is only one proxy of exposure; there are others, such as the number of covers or samples, which presumably are also considerable sources of exposure to the original song. When assessing this possibility with a regression model we note that most of the variability in recognition proportion in our sample is captured by Spotify play counts, but the number of samples and number of covers also explains smaller but significant proportions of variance in recognition, R 2 = 0.41, F(2,134) = 30.93, p <0.01. The respective normalized beta-coefficients are 0.48, 0.24 and 0.14, for Spotify play counts, number of samples and numbers of covers. However, note that one ought to be cautious when interpreting these numbers at face value, as it presumes that songs were covered and sampled at random, which is presumably not the case. There is a high likelihood why some songs are covered more often than others, including the sheer possibility that they are covered more in the future because they have been covered more in the past. In other words, being covered is highly self-selective and until further research uncovers the reasons for why some songs are covered and others are not, it is hard to interpret what this means.

Given the results of research on collective memory for other historical phenomena, we would not have expected the stable plateau—characterized by high within-phase recognition variability—that we found. One possibility is that this phase results from our participants listening to the music of their parents, when growing up in their household, as suggested by studies on the autobiographical memory of music [ 26 – 28 ]. Another possibility is that the music from the 1960s onwards truly was different from earlier music, with music from the 1960s to the 1990s representing a particularly special time in music. We know from the history of music that it did change dramatically from the 1960s onward—the common practice period transitioned into rock music and then electronically-generated music (Ted Coons, personal communication, 01/23/2018). Moreover, the lyrics of popular music also changed. Starting in the 1960s, we saw political music, whereas prior to that time, love songs dominated, as shown by a content analysis [ 29 ]. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, but we were curious to know if we could find further support for the notion that the 1960s to 1990s were a unique time in terms of popular music.

To address this issue, we looked at the diversity of song titles over time. To quantify this trend, we plotted the number of unique titles that occupied the number-one spot as a function of the year during which they were most popular. In years during which this number was low, few titles managed to hog the top spot; in years during which there was fierce competition between equally popular but different songs, this number was high, as it was more difficult for any given song to stay on top for long ( Fig 5 ).

Note that the data was smoothed by a 3-year moving average. A value of just above 10 in the early 1940s means that an average song was at the top of the charts for over 4 weeks in a row. The peak levels in the mid-1970s mean that the average song was only on top of the charts for little more than a week during that period.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210066.g005

We observed three distinct phases similar to those seen in Fig 1 . Phase 1: low diversity from 2015 to the 1990s. Phase 2: high diversity from the 1960s to the 1990s. Phase 3: low diversity—again—from the 1940s to the end of the 1950s. Diversity here means the number of unique singles that occupied the number-one spot during a given year. To quantify the diversity in titles over time, we first binned the data according to the phases we identified in Fig 1 and then computed the mean and standard error of the mean for each. The mean for each of the three phases is 6.73, 11.32 and 6.14, respectively. Next, we performed a Mann-Whitney U test to confirm that there is, once again, a statistically significant difference between Phases 1 and 2, U = 83, p = 3.32e-05; and Phases 2 and 3, U = 71, p = 1.88e-07; but not Phases 1 and 3, U = 192, p = 0.16. This pattern is undeniable, but we cannot speculate the underlying reasons. Anything we could propose, such as changes in listening habits and technology or the rise of DJ culture and dance music, would be purely speculative. However, there seem to be distinct diversity peaks in almost every decade, which could lead to the suggestion of “boom and bust” cycles in music, giving each decade a unique sound when the old sound has “played out”.

We identified three distinct phases in the collective memory for popular music. The first phase is characterized by generally high recognition with a steep linear drop-off and low inter-song variability. For the second phase, we observed moderately high recognition with high inter-song variability—some songs are well-remembered whereas others are not. In the third and final phase, recognition drops again to rather low levels as time passes, and inter-song variability is relatively low again. We also found that a sizeable proportion—more than half—of this recognition variability can be accounted for by self-selected exposure to each song as measured by its overall play count on Spotify.

We interpret these findings to mean that collective memory for popular music—and perhaps for cultural artifacts in general—is different than that for political leaders, be they in the United States [ 10 ] or China [ 11 ]. There are two important differences. First, the drop-off we observed is only linear for a short period, until it hits the recognition plateau from the 1960s to the 1990s. Second, there seems to be no primacy effect for popular music. There are several possible explanations for this. For instance, the primacy effect for political leaders presumably stems from the fact that the founders of a political dynasty are frequently repeated in public discourse. Conversely, people demonstrably do not choose to listen to songs from the early years of the Billboard , if Spotify play counts are a valid metric of exposure. In fact, play counts for this period are remarkably low (see Fig 4 ). The issue of play counts highlights another difference between existing work on collective memory for political leaders and our work here. Presumably, people are exposed to political leaders in history classes and coursework, much of which is part of mandatory schooling. In contrast, much—if not most—of music listening is both voluntary and self-selective. There are other differences as well. The number of historical leaders is countably finite—in terms of United States presidents, there have been only 45 to date. However, the universe of existing music is vast and—from the perspective of an individual—basically boundless. Given this consideration, it is surprising that our recognition rates are as high as they are. As there are strong recency effects for both Chinese and American leaders—but not for popular music—the actionable advice would be that if one wants to remain famous in politics, they must found a political movement. Conversely, if one wants to remain famous for their art, they have to keep producing new releases, or release them during a special period that increases the chances of being remembered. Few things will stand the test of time, in particular if they are not repeated. Finally, our work involved reports of recognition in response to a specific stimulus whereas most existing work on collective memory used free recall. One paper that did use recognition methods—again on United States political leaders—suggests a proneness to false-positives due to contextual familiarity [ 30 ], as has been shown previously for other material [ 31 ].

In addition, these results put the notion of a hard cultural horizon in question. We do not find a period during which recognition drops to zero. Even our millennial participants—which formed the bulk of our participant pool—were not completely unaware of the music that was popular in the 1940s. We posit several plausible explanations for this. For instance, it is possible that not enough time has passed since the first titles of our stimuli set. Perhaps a future study might be able to identify when recognition hits zero (the cultural horizon), if there is a long enough history of Billboard music. However, it is also possible that involuntary exposure through film, television and radio or accidental exposure through music discovery services such as Pandora allows people to discover music that might be very old indeed. Finally, people might also intentionally seek out the music of previous generations. In principle—as much, if not all music is recorded and digitally available forever—this could prevent a cultural horizon indefinitely. We are unable to distinguish these possibilities in the present study.